Summary

This study develops an observational model to assess kidney function recovery and xenogeneic immune responses in kidney xenotransplants, focusing on gene editing and immunosuppression. Two brain-dead patients undergo single kidney xenotransplantation, with kidneys donated by minipigs genetically modified to include triple-gene knockouts (GGTA1, β4GalNT2, CMAH) and human gene transfers (hCD55 or hCD55/hTBM). Renal xenograft functions are fully restored; however, immunosuppression without CD40-CD154 pathway blockade is ineffective in preventing acute rejection by day 12. This rejection manifests as both T cell-mediated rejection and antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), confirmed by natural killer (NK) cell and macrophage infiltration in sequential xenograft biopsies. Despite donor pigs being pathogen free before transplantation, xenografts and recipient organs test positive for porcine cytomegalovirus/porcine roseolovirus (PCMV/PRV) by the end of the observation period, indicating reactivation and contributing to significant immunopathological changes. This study underscores the critical need for extended clinical observation and comprehensive evaluation using deceased human models to advance xenograft success.

Keywords: xenotransplantation, kidney transplantation, genetically engineered pig, brain-dead human decedent, acute xenograft rejection, PCMV/PRV

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Successfully completed two pig-to-human kidney transplants in brain-dead human recipients

-

•

Renal function restoration in kidney xenografts from genetically modified minipigs

-

•

Acute rejection occurred by day 12 without CD40-CD154 blockade

-

•

Reactivation of PCMV led to significant immunopathological changes in recipients

Yi Wang et al. successfully performed two pig-to-human kidney xenotransplants using genetically modified minipigs, which led to restored renal functions. The study described immunological and pathological changes and the impact of porcine cytomegalovirus reactivation on graft survival, highlighting the potential of this model to advance xenotransplantation toward clinical applications.

Introduction

The persistent global organ shortage has spurred intense interest and innovation in transplantation medicine, leading to the exploration of xenotransplantation as a potential solution. Recent breakthroughs in biotechnology have paved the way for genetically engineered porcine kidney xenotransplantation, marked by initial progress in eight transplantations into brain-dead humans (six cases of kidney and two cases of heart xenotransplantation).1,2,3,4,5,6,7 These studies demonstrated that targeted gene modifications can effectively overcome the natural hyperacute rejection response encountered in pig-to-human xenotransplantation. However, the brain-dead decedent model, while offering clinical relevance beyond non-human primate (NHP) models, has inherent limitations in terms of observation duration, with the reported times ranging from 54 to 74 h to a maximum of 7 days.5 This limited time frame or premature termination may not allow sufficient progression of the pathological changes of acute xenograft rejection. In the current study, with full informed consent and graciously written authorization from the next of kin of the brain-dead donors, the observation period was extended as long as feasible by maintaining hemodynamic stability until xenograft dysfunction or specific conditions necessitated termination. This extended time frame enabled us to comprehensively investigate the process of xenograft rejection and dysfunction, especially the post-hyperacute rejection phase, shedding light on critical aspects of this groundbreaking procedure, especially transplantation immunology, with an ultimate goal of achieving successful long-term kidney function restoration.

Results

Clinical course and xenograft function

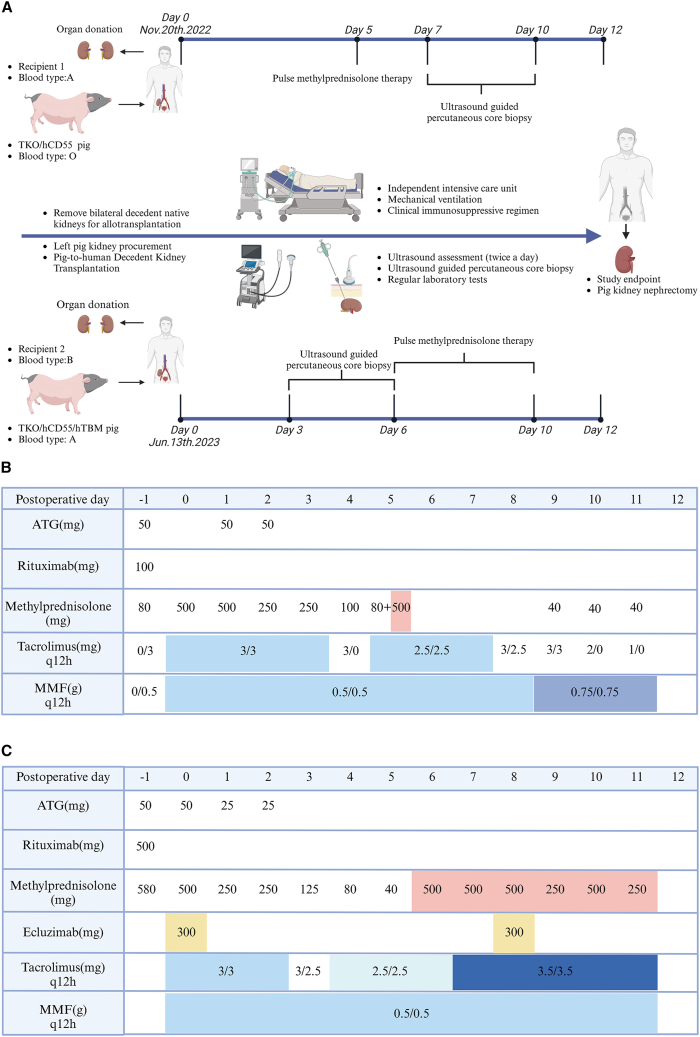

The research process and the immunosuppression regimen for two cases of pig-to-brain-dead human kidney xenotransplantation are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research process and immunosuppression regimen

(A) Two cases of porcine-to-human decedent kidney transplantation: research timeline and event summary.

(B) Pharmacologic immunosuppression regimen of case 1.

(C) Pharmacologic immunosuppression regimen of case 2.

Normal renal function was restored rapidly after transplantation in case 1 (Figure 2). The mean daily urine output was 4,000 mL, with serum creatinine (SCr) fluctuating around 100 μmol/L during the first 4-day period. On postoperative day (POD) 5, urine output decreased significantly to around 1,000 mL and then returned to normal until POD 11 after dosing with 500 mg of methylprednisolone. However, SCr levels rose to 238 μmol/L on POD 6 and then fluctuated between 175 and 300 μmol/L, ending at 221 μmol/L on POD 12 (Figure 2B). During the observation period, the trough level of tacrolimus fluctuated between 5 and 20 ng/mL. Peripheral blood B lymphocyte counts remained low after rituximab administration. However, satisfactory T lymphocyte counts were not achieved following the administration of rabbit antithymocyte globulin (rATG), with a noticeable temporary rebound on POD 5 (Figure 2B). At the time of termination on POD12, the xenograft appeared firm, dark red, and significantly enlarged, with scattered hemorrhagic spots; focal hemorrhages at the corticomedullary junction were seen on the kidney surface (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Clinical outcomes and immunological monitoring of case 1 throughout the postoperative course

(A) Gross findings from the xenograft: xenograft perfusion (A1), xenograft reperfusion (A2), xenograft at termination (A3), and cross-section of the xenograft (A4).

(B) Changes in urine output, serum creatinine, platelets, hemoglobin, tacrolimus concentration, and lymphocyte subsets.

(C) Changes in antibody binding (IgM and IgG) to donor pig PBMCs and CDC against the same PBMCs (Mix: the pooled sera of 20 healthy human volunteers were used as control sera).

Case 2 (Figure 3) had a urinary output of >2,000 mL/day for the first 9 days after transplantation, and the SCr decreased from 216 μmol/L (POD 0) to 100 μmol/L (POD 5). However, because of a rise in SCr to 135 μmol/L and an elevated renal arterial resistive index (RI) of 0.9 on POD 6, a high dose of methylprednisolone (500 mg/d) was administered. Despite methylprednisolone therapy, the SCr did not decrease significantly and began to increase progressively on POD 9; urinary output decreased significantly, and the SCr was 585 μmol/L at the end of the study on POD 12 (Figure 3B). The trough level of tacrolimus fluctuated between 5 and 15 ng/mL during the observation period. Peripheral blood T and B cell counts remained at very low levels after administering rituximab and rATG (Figure 3B). A significant increase in SCr level and a marked reduction in urinary output led us to terminate the trial on day 12. At the time of termination, the transplanted kidney was grayish-brown in color, markedly enlarged in size, and hard in texture, and focally hemorrhagic foci were visible on the kidney surface (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Clinical outcomes and immunological monitoring of case 2 throughout the postoperative course

(A) Gross findings from the xenograft: xenograft perfusion (A1), xenograft reperfusion (A2), xenograft at termination (A3), and cross-section of the xenograft (A4).

(B) Changes in urine output, serum creatinine, platelets, hemoglobin, tacrolimus concentration, and lymphocyte subsets.

(C) Changes in antibody binding (IgM and IgG) to donor pig PBMCs and CDC against the same PBMCs (Mix: the pooled sera of 20 healthy human volunteers were used as control sera).

(D) Expression of blood group A antigen on xenografts and the changes in serum anti-A antibodies against human type A RBCs.

Color Doppler ultrasound was used to monitor the changes in blood flow and size of the kidney xenografts. Initially, both xenografts exhibited abundant blood flow signals with no significant volume increase in the first 5–6 days post-xenotransplantation. Subsequently, the blood flow signal of both renal xenografts gradually decreased, and xenograft volume progressively increased, basically consistent with the deterioration of renal function (Figure S1).

Throughout the postoperative period, serum levels of K+, Cl−, and Ca2+ remained within the normal range. However, as renal function declined, both recipients experienced a significant increase in serum Na+ levels. Notably, elevated serum HCO3− levels were observed even during periods of normal renal function. Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) generally increased with worsening renal function. Concurrently, fibrinogen and antithrombin III levels exhibited an overall downward trend post-transplantation. D-dimer remained at a high level throughout the postoperative process. Urinary microalbumin levels were almost negative when renal function was normal but then were significantly elevated with increased SCr. Erythropoietin (EPO) levels remained consistently low after transplantation in case 1. In contrast, case 2 did not experience a decrease in EPO levels as a result of exogenous EPO supplementation (Figures S2 and S3).

The presence of anti-donor xenoantibodies

To determine the levels of anti-donor pig antibodies and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), serum samples from the two cases before and after transplantation were tested by flow cytometry; peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the donor blood samples and used for analysis. The pooled sera of 20 healthy human volunteers were used as control sera.

Before transplantation, the levels of anti-pig immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the serum of case 1 were approximately 2-fold higher than those in the control pooled human sera, implying significantly higher levels of natural xenoantibodies against triple-knockout (TKO) pig PBMCs in this case than in the general population. Consistent with the antibody binding results, the cytotoxicity of pre-transplant serum against pig PBMCs was relatively higher than that of the control sera (9.6% vs. 4.4%) (Figure 2C). At various time points after transplantation, the serum levels of anti-pig IgM and IgG were not significantly increased; this result indicates that the recipient did not produce a significant level of induced xenoantibodies (Figure 2C), although the possibility of anti-pig antibodies being removed from the serum through absorption by antibody bound to the xenograft could not be completely ruled out.

Unlike case 1, the levels of anti-donor pig IgM and IgG antibodies in the pre-transplant serum of case 2 were initially comparable to those in the pooled human sera. However, a significant increase was observed at 6 to 9 days after transplantation, leading to a significant elevation in CDC (Figure 3C). In addition, since case 2 was an ABO blood test-incompatible (ABO-incompatible) (A-to-B) xenotransplantation, flow cytometry was used to detect changes in the anti-A antibody levels. Serum levels of both anti-A-IgM and IgG were low before transplantation; although the levels of anti-A-IgG did not change significantly afterward, the levels of anti-A-IgM markedly increased (Figure 3D).

Histopathological findings

In case 1, the multifocal infiltration of mononuclear cells and mild intimal arteritis of the biopsy specimen were observed on POD 7. Furthermore, microvascular inflammation (MVI) characterized by glomerulitis (g) and peritubular capillaritis (PTC) also appeared (Figure 4A). These changes suggested the presence of acute T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) and antibody-mediated rejection (AMR). C4d staining was focally positive in the PTC on POD 7 and diffusely positive on POD 10 and POD 12 (Figure 4B). Immunofluorescent staining on POD 7 and 10 showed only weakly positive, scattered deposition of IgM, IgG, and C3. In contrast, strongly positive IgM, IgG, C3c, and C5b-9 deposits were found in dysfunctional anatomical specimens on POD 12 (Figure 4B). The infiltrated mononuclear cells included CD3−, CD4−, and CD8-positive lymphocytes, along with an increased number of CD16+ natural killer (NK) cells and CD68+ macrophages. In the autopsy specimens on POD 12, the degree of glomerulitis was aggravated, and infiltrated CD68+ macrophages were significantly increased. CD68+ macrophages and CD16+ NK cells were mainly infiltrated into the MVI; according to the Banff score, the total score for the MVI was equal to 5 (g3 + PTC2) (Figure 4C). Electron microscopy (EM) revealed infiltration of monocytes and neutrophils into capillary loops of the glomerulus and peritubular capillaries, significant endothelial cell swelling, and widening of the subendothelial space with near occlusion of the capillary loops, and a small amount of fibrin tactoid deposition in the subendothelium; however, no fibrin thrombi were observed on POD 12 (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Histopathology of xenograft of case 1

(A) H&E staining of the case 1 xenograft on postoperative day 7, day 10, and day 12, and EM on postoperative day 12. Thick arrows show mild intimal arteritis (A1) and acute tubular injury (A3). Arrowheads show mild glomerulitis (A5, 7). Arrows show mild peritubular capillaritis (A5, 6, 7). EM of graft on day 12 shows endothelial cell swelling and a widened subendothelial space with loss of endothelial fenestrations (black asterisk) and a small amount of fibrin tactoid in subendothelial area (white arrow), but no fibrin thrombi (A4). (A8) tubule epithelial cell swelling and disintegration (white asterisk); PTCs are dilated (black asterisk) and monocyte infiltrated (black arrow). Bars represent 100 microns (A1–3), 50 microns (A5–7), 2 microns (A4), and 10 microns (A8), respectively.

(B) The immunohistochemical staining of C4d and immunofluorescent staining of immunoglobulin and complement of the case 1 xenograft on postoperative day 7 (B1–4), day 10 (B5–8), and day 12 (B9–13). C4d staining is focally positive in PTC on day 7 and diffusely positive on day 10 (B1, B5), C4d-positive tubular epithelium on day 10 (B5), and diffusely C4d-positive PTC on day 12 (B9). Immunofluorescent staining for IgM, IgG, and C3c was weakly and sporadically positive on day 7 and day 10 (B2–4, 6–8), but prominently positive on day 12 (B10–12). A prominently positive deposition of C5b-9 was found on day 12 (B13). Arrowheads show positive staining of glomeruli. White arrows show positive peritubular capillary (B10) or positive staining of tubular epithelial cells (B11, 12). Bars represent 100 microns (B2–4, 6–8, 10–13) and 50 microns (B1, 5, 9), respectively.

(C) Immunohistochemical staining of infiltrated inflammatory cell phenotypes of the case 1 xenograft on postoperative day 7 (C1–5), day 10 (C6–10), and day 12 (C11–15). Staining is shown for CD3 (C1, 6, 11), CD4 (C2, 7, 12), CD8 (C3, 8, 13), CD16 (C4, 9, 14), and CD68 (C5, 10, 15). Thick arrows show multifocal lymphocyte infiltrated into the renal interstitium (C1–3, 6–8, 11–13), and arrowheads show infiltrated CD8+ lymphocytes (C8), CD16+NK cells (C4, 14), and CD68+ macrophages (C5, 15) in the glomerulus. Arrows show peritubular capillaritis and infiltrated CD16+NK cells (C4, 9, 14) and CD68+ macrophages (C5, 10, 15). Bars represent 50 microns.

In case 2, no significant acute TCMR changes were observed during the postoperative observation period, but MVI changes were seen in biopsy samples on POD 6 and in autopsy specimens on POD 12 (Figures 5A and 5C). Furthermore, C4d was diffusely positive on both POD 6 and 12. The immunofluorescent staining of case 2 was similar to that of case 1 in that there were weakly positive, scattered deposits of IgM, IgG, and C3; prominently positive IgM, IgG, C3c, and C5b-9 were also evident in dysfunctional specimens on POD 12 (Figure 5B). The infiltrating inflammatory cells were mainly CD16+ NK cells and CD68+ macrophages on POD 6 and POD 12 (Figure 5C). EM revealed frequent monocytic infiltration into glomerular capillary loops and adhesion to the endothelial cells, as well as infiltration of neutrophils into the peritubular capillaries (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Histopathology on xenograft of case 2

(A) H&E staining of the case 2 xenograft on postoperative day 3 (A1, 5), day 6 (A2, 6), day 12 (A3, 7) and EM on postoperative day 12 (A4, 8). There was no significant mononuclear cell infiltration in the interstitium during the postoperative observation period. Arrows show mild peritubular capillaritis (A7). Day 12 EM observation of the xenograft revealed monocyte infiltration into glomerular capillary loops and adhesion to endothelial cells, and neutrophil infiltration into peritubular capillaries (arrows). Bars represent 100 microns (A1–3), 50 microns (A5–7), 2 microns (A4), and 10 microns (A8), respectively.

(B) Immunohistochemical staining for C4d and immunofluorescent staining for immunoglobulin and complement in the case 2 xenograft on postoperative day 3 (B1–4), day 6 (B5–8), and day 12 (B9–13). C4d staining was negative on day 3 (B1) and diffusely positive on day 6 and day 12 (B5, 9). The immunofluorescent staining for IgM, IgG, and C3c was weakly sporadically positive on day 3 and day 6 (B2–4, 6–8), while a prominent positive deposition was found on day 12 (B10–12). A weakly positive deposition of C5b-9 was observed on day 12 (B13). Arrowheads show positive staining of glomeruli. Bars represent 100 microns (B2–4, 6–8, 10–13) and 50 microns (B1, 5, 9), respectively.

(C) Immunohistochemical staining of infiltrated inflammatory cell phenotypes of the case 2 xenograft on postoperative day 3 (C1–5), day 6 (C6–10), and day 12 (C11–15). Staining is shown for CD3 (C1, 6, 11), CD4 (C2, 7, 12), CD8 (C3, 8, 13), CD16 (C4, 9, 14), and CD68 (C5, 10, 15). Arrowheads show glomerulitis and infiltrated CD68+ macrophages (C10, 15) and CD16+NK cells (C14). Arrows show peritubular capillaritis and infiltrated CD68+ macrophages (C5, 10, 15) and CD16+NK cells (C14). Bars represent 50 microns.

Although microvascular endothelial injury was evident in the two xenografts, no microthrombosis, renal parenchymal hemorrhage, or necrosis was observed. Acute tubular injury and partial tubular epithelial necrosis, however, were seen in both cases in biopsy and anatomical specimens (Figures 4A and 5A). In both kidney grafts, no reduction in human transgene expression was observed on day 12 when compared to that on day 0 (Figure S5D).

Donor screening and viral findings

Donor pigs underwent comprehensive pathogen screening before transplantation, yielding negative results for all pathogens except porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV)-A and PERV-B (Table S1). Although the donor pig nasal swab was porcine cytomegalovirus/porcine roseolovirus (PCMV/PRV) negative before transplantation, subsequent post-transplant autopsy outcomes revealed the presence of PCMV/PRV DNA in both xenografted kidneys and selected recipient (heart, liver, spleen, and lung) in both cases (Figure 6 and Table S2). It is essential to emphasize that typical PCMV/PRV inclusion bodies or viral particles were conspicuously absent from the histopathological sections and EM specimens, even after meticulous EM scrutiny. Furthermore, PCMV/PRV particles were conspicuously absent from renal tubule epithelial cells, glomerular capillary loop endothelial cells, and peritubular capillary endothelial cells (Figures 4A and 5A).

Figure 6.

Analysis of PERVs and PCMV/PRV in xenografts and decedent tissues

(A) “W” represents water, as a negative control. Lane 1–3: recipient PBMCs of Pre-Tx, Post-Tx, and termination; lane 4–7: recipient heart, liver, spleen, lung after termination; lane 8: kidney from a PERVA/B/C-positive pig, Lane 9: pig-1 kidney after termination; (B) lane 1–7: recipient PBMCs of Pre-Tx, Post-Tx1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and termination; lane 8–12: recipient heart, liver, spleen, lung, and lymph nodes after termination; lane 13: the kidney from a PERVA/B/C-positive pig; lane 14: pig-2 kidney after termination; (C) PCMV/PRV detected by nested PCR using xenografts and case 1 samples; (D) PCMV/PRV detected by nested PCR using xenografts and case 2 samples; The transplanted transgenic kidney from the donor pig and the heart, liver, spleen, and lung of the recipient were analyzed. Pig (+) is a PCMV/PRV-positive pig; water is shown as a negative control.

Discussion

Previous studies have had limited kidney xenotransplantation observation periods ranging from 2 to 7 days,1,2,3,4,5 suitable for demonstrating hyperacute rejection scenarios in pig-to-human decedent models. In the present study, with a time frame extended to 12 days, additional immunological events and definitively pathological manifestations became evident.

In the previously reported preclinical trials of pig-to-human kidney xenotransplantation, donor pigs were either single-gene (GGTA1) knockout or 10-gene-edited (4 gene knockouts and 6 human transgene insertions) animals. Montgomery et al.1 transplanted “thymokidneys” from GGTA1-knockout pigs into two brain-dead human decedents, employing daily high-dose methylprednisolone and twice-daily intravenous mycophenolate mofetil. Both xenografts maintained good function for 54 h, showing no signs of hyperacute or AMR. Porrett et al.2 transplanted two kidneys from a 10-gene-edited pig into a human deceased recipient and used an immunosuppressive regimen quite similar to our study. Although no hyperacute rejection was observed, the xenograft function appeared unsatisfactory during the 74-h observation period.2 They later reported another case by Locke et al.5 using the same gene-edited pig, with the addition of anti-C5 monoclonal antibody (mAb) in the immunosuppressive regimen and found that xenograft function remained normal for 7 days. However, due to the limited observation time, the final outcome remained unknown. There is also a recent case report with an extended observation period of 61 days, which is another step forward in xenotransplantation; however, the detailed results of this case have not yet been published.6

In the present study, the donor pigs employed were triple-gene knockouts, which are widely recognized as potentially ideal for future clinical applications. In addition, in corresponding to the protective effect of hCD55 on renal xenografts in pig-to-NHP models, our donor pigs were either transferred with the hCD55 gene alone or in combination with the human anticoagulation gene thrombomodulin (TBM) (Figure S4). The detection results for the donor pigs confirmed the gene knockout effect, and the expression level of the transgenes met the requirements (Figure S5). Our previously reported results of in vitro experiments also showed that human serum IgG and IgM binding to the PBMCs of our gene-edited pigs was almost negligible.8

Since clinical practice only allows the use of existing Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved immunosuppressants, our study followed almost the strongest regimen consisting of clinically available immunosuppressants. However, the current unavailability of CD40-CD40L pathway-blocking mAb and belatacept in the Chinese pharmaceutical market limited our options to routine clinical immunosuppressive regimen. The two renal xenografts in our study underwent acute xenograft rejections within 12 days, suggesting that acute rejection may pose a significant immunological barrier to the long-term survival of future clinical kidney xenotransplantations under current clinically feasible immunosuppressive protocols. Nevertheless, our current study did not employ a CD154-CD40 pathway-blocking antibody or thymic tissue to reduce the xenogeneic immune response.9 Whether these additional treatments can effectively control acute xenograft rejection and consequently significantly prolong graft survival is a topic worthy of further study.

Cytokine or inflammatory factor storms typically occur in the early stage of fatal brain trauma. However, our cases received prolonged treatment in the emergency department and intensive care unit (ICU) before brain death. By the time of organ donation and xenotransplantation, the storm phase had likely passed, as indicated by the absence of central diabetes insipidus and near-normal cytokine levels in our supplemental data. Throughout the observation period, we monitored cytokines and inflammatory factors levels, including interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interferon-γ levels. In case 1, the levels of all cytokines and inflammatory factors were normal or near normal during the first 7 days after transplantation, and only IL-10 continued to increase from day 7 onwards. In case 2, IL-6 levels were high in the early stage and gradually decreased, while other cytokines and inflammatory factors were almost at normal levels (Figures S6 and S7). These findings suggest that initiating xenograft studies after brain death or cytokine storm should not significantly impact outcomes.

Our results indicated that graft loss was primarily due to specific immune responses (such as AMR and TCMR or their combination), rather than nonspecific inflammatory factors. Histopathological observations definitively revealed the presence of TCMR and AMR in case 1, and AMR in case 2. Cellular rejection was evident through multifocal inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal interstitium, significant MVI, diffuse C4d deposition, and positive immunofluorescent staining for immunoglobulin and complement. These findings highlight the crucial role of complement inhibitors (e.g., anti-C5 therapy) even when the xenograft expresses hCD55. At present, there are only two kinds of complement inhibitors in clinical practice: anti-C5 mAb and C1 inhibitor, among which anti-C5 mAb has a stronger inhibitory effect on the complement activation. AMR occurred despite the use of anti-C5 mAb in case 2, probably due to the use of a lower dose of anti-C5 mAb (300 mg/dose) than the standard dose (900 mg/dose). Increasing the dose of anti-C5 mAb may be beneficial to improve the outcome. In addition, we used a low-dose rATG therapy (approximately 2.5 mg/kg) in both cases, which is consistent with common practice of clinical renal allotransplantation in China, but below the US FDA-recommended standard dose (4.5 mg/kg). According to the recommended dose of 0.04–1.5 mg/kilogram/day (kg·d) in the Chinese guidelines, the total dose of rATG given to both cases was 150 mg. With this dose of rATG, desired T cell depletion was achieved in case 2. However, case 1 exhibited relatively weak T cell depletion, which may have contributed to the TCMR in this case. Therefore, in order to avoid TCMR, future pig-to-human xenotransplantation may require the use of higher doses of rATG. It is noteworthy that initiating ATG treatment earlier than anti-C5 therapy is optimal, since C5 inhibition may reduce the effectiveness of ATG

Monocytic infiltration and endothelial cell damage at the site of MVI were both detected. The involvement of AMR was also clearly suggested by EM, especially in the form of monocytic infiltration and endothelial damage in the capillaries of the microcirculation. These findings indicate that both CDC and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity may play an important role in the initialization and development of AMR.

Furthermore, it is important to mention a comprehensive study led by Loupy and coworkers,4 utilizing specimens provided by Montgomery et al.,1 which further demonstrated that potential rejection was evident within 2–3 days after xenotransplantation. Using the latest multidimensional spatial molecular assessment analysis, they found early signs of AMR in renal xenografts from single-gene knockout (GGTA1) pigs transplanted into brain-dead human decedents. Their findings were characterized by MVI, primarily representing activation of monocytes and macrophages in the glomeruli, as well as increased NK cells and endothelial cell activation. These findings align closely with our histopathological observations. Although these phenomena were discovered earlier than ours, the limited observation time in the study prevented these investigators from observing the consequential immunopathological damage and outcomes.

It is necessary to select recipients with low titers of anti-pig antibodies to ensure successful long-term xenograft survival. In case 1, the recipient exhibited higher anti-pig antibody levels than did the control pooled human sera. However, the lack of a definitive threshold for antibody levels complicates the categorization of low, moderate, and high titers that affect xenograft survival. The results of our previous study,8,10,11 which involved pig-to-monkey kidney xenotransplantation, revealed no consistent correlation between anti-pig antibody titers and xenograft survival (data not shown). Various factors, including the immunosuppressive regimens followed and the genetic characteristics of the engineered pigs, also contributed to the outcome.

No definitive reports exist regarding the development of anti-blood-type antibodies (e.g., anti-A) in NHPs and humans following xenotransplantation of genetically modified pig organs, primarily because blood-type-O pigs are commonly employed. Due to the limited availability of gene-edited pigs, we randomly paired gene-edited pigs and human brain-dead organ donors. In addition, it is often difficult to accurately determine blood type in pigs using commonly used clinical methods, which resulted in the ABO-incompatible (A-to-B) xenotransplantation in case 2. Although pre-transplant serum anti-A IgM and IgG levels were low before transplantation, serum anti-A IgM levels were markedly increased after transplantation, suggesting that blood group antibodies may be involved in AMR in this case. Several significant observations were made concerning case 2, as listed in the following. (1) Our study identified AMR in ABO-incompatible xenotransplants within 2 weeks, an uncommon phenomenon when compared to the same regimen in clinical ABO-incompatible allotransplantation. (2) The immunosuppressive regimen employed in our study seemed to suppress the development of anti-A IgG antibodies, but not anti-A IgM production. This study highlights the importance of matching blood group types for xenotransplantation. We have now developed an effective pig blood type testing and screening protocol to ensure the use of O-type pigs as donors for future subclinical and clinical studies.

Before transplantation, the health of the donor pigs was confirmed, and serum samples obtained on the day of transplantation detected no signs of PCMV/PRV (Figure S8A). A critical observation was that PCMV/PRV remained absent from the sera of the transplant recipients until 12 (case 1) or 6 days (case 2) post-transplantation (Figures S8B and S8C). These findings suggest that latent PCMV/PRV present in the donor pig kidneys was reactivated as a result of the transplantation and subsequent immunosuppression. It is essential to note that there was no evidence of active PCMV/PRV infection in the donor pigs before transplantation.

The pigs used in this study were initially screened for pathogens and were negative for PCMV/PRV through throat swabs. They were kept as “clean grade animals” under non-designated pathogen-free conditions. Although PCMV/PRV testing was negative for pre-transplant serum, we detected positive PCMV/PRV in both xenografts after transplantation. We believe this is due to a latent PCMV/PRV infection, which may have evaded our previous detection methods (nasal swab samples and nested PCR assay). Prior to transplantation, donor pigs older than 6 months may be in the incubation period of carrying the virus, and detection may be ineffective due to low viral load. Newborn piglets may acquire PCMV/PRV-reactive antibodies via colostrum from infected mothers, further complicating detection tests. Thus, a sensitive detection method, along with the collection of diverse samples from animals of varying ages, is essential.12 We are actively revising our detection method based on a recent comprehensive review12 and experimental finding.13 The main strategy for obtaining PCMV/PRV-free donor pigs is to prevent a PCMV/PRV infection in the piglets by Cesarean section and early weaning,12 and then raising them in PCMV/PRV-free facilities. In addition, ensuring a pathogen-free environment for the pig post-acquisition is paramount. This highlights the need for future studies to utilize designated pathogen-free pigs directly, rather than clean-grade animals that rely on throat swab screening. Although this is more expensive, it ensures clearer results.

As early as 2014, Yamada et al. clearly warned that PCMV/PRV infection was associated with early rejection of kidney grafts in a pig-to-baboon xenotransplantation model.14 Recently published reports on the dysfunction of the first human heart xenotransplant13,15 also indicated that PCMV/PRV infection and reactivation in vivo are potential causes of endothelial cell damage in xenografts.

In addition, our study has demonstrated the presence of PCMV/PRV in all recipient organs tested (heart, liver, spleen, lung) in both cases. This finding is consistent with the observations reported by Muhiuddin et al.13 However, it is crucial to note that their comprehensive study did not detect transcription of the virus in any recipient tissues. Furthermore, the identification of PCMV/PRV DNA was only made in conjunction with porcine cell DNA. This result suggests that PCMV/PRV DNAemia may have originated from lysed or circulating porcine cells or PCMV/PRV virions generated within the xenograft, rather than from active replication of PCMV/PRV within the recipient organs.

While our study identified PCMV/PRV DNA through a nested PCR assay, we found no pathological features indicative of PCMV/PRV infection in the recipients’ tissues (data not shown). This suggests that the detected viral DNA may not necessarily correspond to the presence of a replicating virus capable of causing infection. A further comprehensive follow-up study is warranted in future research.

While hyperacute rejection due to ABO incompatibility was not observed in the second case, the presence of ABO incompatibility (with latent PCMV/PRV reactivation in both cases) adds complexity to the interpretation of our results. These factors require careful consideration when attempting to understand xenograft rejection dynamics in brain-dead individuals. It is essential to use PCMV/PRV-negative (i.e., no latent PCMV/PRV infection) and O-blood-type donor pigs for both preclinical and clinical xenotransplantation. Upgraded DPF facilities, especially with regard to PCMV/PRV, have been established to benefit our future studies.

The findings from our two cases are closely aligned with expectations derived from prior NHP studies, in particular, with the following two points: (1) PCMV/PRV reactivation may accelerate xenograft rejection14 and (2) long-term xenograft survival cannot be achieved by conventional immunosuppressive therapy (i.e., without CD40-CD154 pathway blockade).16 These findings highlight the fact that comprehensive and long-term observations in pig-to-NHP preclinical xenotransplantation models are still essential. Eisenson et al. recently demonstrated that belatacept, as an alternative to CD40-CD154 antibodies, can also achieve long-term survival in pig-to-NHP xenotransplantation.17 Unfortunately, the drug has not yet entered the Chinese pharmaceutical market.

It is important to note that the immune response to pig cells between humans and Old World NHPs differs, stemming from the inherent differences between the immune systems of humans and Old World NHPs.18 Moreover, using NHP models poses challenges, as recipient animals are typically housed in standard cages under suboptimal conditions without constant supervision. The brain death decedent serves as a new research model and a bridge between NHP studies and initial clinical trials. In fact, the brain-dead decedent model used in our study can more closely resemble the human clinic and allow continuous care 24 h a day by the entire clinical staff, including surgeons, ICU nurses, doctors, and anesthesiologists. Although the number of cases in our study was limited and the duration was relatively short, it demonstrated that the 12-day observation period was sufficient to effectively test anti-hyperacute rejection regimens and observe delayed or accelerated xenograft rejection. We demonstrated that the gene-editing protocol effectively controlled hyperacute rejection but that the routine clinical immunosuppressive regimens, without CD40-CD40L blockade, were insufficient to control subsequent acute rejection.

Hemodynamic stability of the brain-dead decedents was effectively maintained for at least 12 days with the support of ventilation and standard ICU medications, including norepinephrine and dopamine for maintaining blood pressure to prolong this preclinical xenotransplantation study. This study established that decedents in a state of brain death, despite their many pathophysiological features that differ from those of healthy humans, remained intact in terms of instinctive immune response capacity throughout the study period and were suitable for xenotransplant investigation.

There are additional limitations of our study. At the time of the initiation of our study, we used the best knowledge at the time to design our study. However, as xenotransplantation is a fast-moving field, some collective lessons learned can be beneficial for future transplantation design broadly, including donor genetic modifications, the immunosuppressive regimen, elimination of PCMV reactivation, and suppression of cytokine storms in a brain-dead recipient patient.19

Despite the limitation of its observation period because of irreversible xenograft rejection, the present study offers some valuable insights, as listed in the following. (1) The extended observation period revealed significant changes such as the reactivation of latent PCMV/PRV in immunosuppressed recipients. The extended 12-day observation unveiled important implications for zoonotic considerations, highlighting the necessity of a prolonged observation period. (2) AMR was observed in ABO-incompatible xenotransplants within 12 days using the same regimen, a phenomenon seldom observed in clinical ABO-incompatible allotransplants. Revealing the need for concern about potential underestimation of the immune response during pig antigen sensitization when the observation period is 7 days or less, this finding underscores the importance of an extended observation for a comprehensive assessment, particularly in xenotransplantation scenarios. (3) Immune responses were observed against pig blood-type-A antigens, in addition to non-Gal antigens, following ABO-incompatible kidney xenotransplantation. (4) Sequential xenograft biopsies provided evidence of innate cell dynamics, including NK cells and macrophage infiltration into the kidney xenografts, as confirmed by immunohistochemistry, the first demonstration of such dynamics in xenotransplantation.

In summary, our observations underscore the importance of an extended observation period and a comprehensive evaluation of preclinical deceased human models for advancing our understanding of xenograft dynamics and survival toward an ultimate goal of achieving successful long-term kidney function restoration.

Limitations of the study

This study, while pioneering in its exploration of pig-to-human kidney xenotransplantation using brain-dead decedents, is not without limitations. The reliance on brain-dead individuals, despite their hemodynamic stability and maintained immune responses, introduces a significant limitation due to the inherent physiological differences between brain-dead decedents and living human recipients. These differences may impact the generalizability of the findings, particularly in terms of long-term graft survival and immune responses in living patients. Additionally, the study design, based on the best available knowledge at the time of initiation, may not fully incorporate the latest advancements in xenotransplantation, including more refined genetic modifications of donor pigs, optimized immunosuppressive regimens, and effective strategies to prevent PCMV reactivation. Furthermore, the management of cytokine storms, a critical challenge in xenotransplantation, remains an area requiring further research, especially in the context of brain-dead recipients who may present heightened inflammatory responses. These limitations underscore the need for continued refinement and validation in future studies to enhance the translational potential of xenotransplantation.

Resource availability

Lead contact

For further information and requests for resources and reagents, please contact the lead contact, Kang Zhang (kang.zhang@gmail.com).

Materials availability

All unique materials generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report any original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the organ donors and their families for their invaluable contributions to medical research. We also thank Fanjun Zeng PhD, Zhuocheng Li BD, Liang Gao BD, Rentian Chen BD, Xiangqin Song BD, Zehua Yuan BD, Ruhong Xia BD, Xiaojie Ma MM, Yunhao Bai BD, Jiahong Chen MM, and Changfu Feng BD for monitoring and postoperative management; Ying Xu MM and Jiahua Song BD for isolation of tissue and serum samples; Song Lyu MM, Yuxiu Zheng BD, and Tao Wang MM for xenotransplantation anesthetic management; Sheng Zhou BD, Pengxiang Li MM, and Xiaowen Wu MM for determination of brain death; Lingxu Li MM, Chang Wang MM, Manzhu Zhang MM, and Chun Luo BD, who helped with histopathological examination; Meihua Chen MM, who performed point-of-care ultrasound; Keyan Zhong MM, responsible for the management of donor pigs; Weijia Wang PhD, Jin Chen PhD, and Zhuandan Zhang MS for help in supervising the operating room construction. We also thank Deborah McClellan PhD for manuscript preparation assistance.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82260154 and 32090054), Hainan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (ZDKJ2019009), Hainan Province Clinical Medical Center, National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3404304), and Macau University of Science and Technology.

Author contributions

Y.W. led the team, established a special research facility, conducted the surgery, and administered the entire study. Z.K.C. initialized the program and advanced the research process, coordinated with other investigators in collecting and analyzing data, and assembled the required parts of the manuscript. Y.W., Z.K.C., G.C., and D.P. designed the study. G.C. and K.Z. made significant contributions in analyzing results, writing, and revising the manuscript. D.P. genetically engineered and provided research pigs and was responsible for target gene identification and pathogen scanning and monitoring of the animals. H. Guo completed the analysis of the pathology portion of the manuscript. H.J. and J.W. participated in the operation. S.H., M.Z., and Y.W. collected data, edited the manuscript, and provided input on the paper. H.F., T.L., and J.D. performed most of in vitro experiments, wrote specific sections of the manuscript, provided figures, and contributed to the discussion. H.Y., H. Gan, Q.W., Z.S., D.L., Y. Yu, H.W., B.L., Y. You, S.Z., M.W., L.L., L.X., M.Y., K.Z., and H.P. helped with data generation and analyses.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| donkey anti-human IgM | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | RRID: 109-605-043 |

| goat anti-human IgG | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | RRID: 109-545-003 |

| anti-human C4d rabbit monoclonal antibody | Abcam | RRID: ab136921 |

| anti-CD4 | ZSGB-BIO | RRID: ZA-0519 |

| anti-CD68 | GeneTech | RRID: GM081429 |

| anti- CD8 | ZSGB-BIO | RRID: ZA-0508 |

| anti-CD3 | GeneTech | RRID: GA045229 |

| anti-CD16 | GeneTech | RRID: GT220329 |

| anti-CD55 | Santa Cruz | RRID: sc-59092 |

| anti-C3c | ZSGB-BIO | RRID: ZF-0301 |

| anti- TM | Santa Cruz | RRID: SC-13164 |

| anti-C5b-9 | Dako-Agilent | RRID: M0777 |

| Rabbit anti-human IgM | Dako-Agilent | RRID: A0426 |

| anti-Neu5Gc | Biolegend | RRID: 146903 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Needle core biopsies and autopsy of xenografts | The Transplantation Institute, Hainan Medical University, Hainan, China | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Isolectin BSI-B4 | Sigma-Aldrich | L2895-1 |

| Dolichos biflorus agglutinin | Vector | FL-1031-5 |

| goat serum | Solarbio | S9070 |

| human type A1 reagent RBCs | Shanghai Blood/Biomedical Co., Ltd | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| genetically modified Bama miniature pigs, see Figure S4 | Clonorgan Biotechnology Co., Ltd | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for PCR in 3KO and transgene genotyping, see Table S4 | This paper | N/A |

| Primer and probe sequences used in PCR and qRT-PCR, see Table S3 | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| flow cytometer | Cytoflex S, Beckman Coulter | N/A |

| FlowJo software | Treestar | N/A |

Experimental model and study participant details

Ethics standards and regulatory concerns

The brain-dead human decedent model was proposed by Montgomery as a bridge from NHP experiments and was first described at the 2019 American Transplantation Congress. Inspired by this concept, the current study was initialized in 2020 and reported to the Director of the China Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee. The National Health and Wellness Commission entrusted the China Organ Transplantation Development Foundation to formulate the “Xenotransplantation Expert Consensus” in 2022.20 Subsequently, the General Office of the State Council issued the “Opinions on Strengthening the Ethical Governance of Science and Technology” report.21 An ethical consultation conference involving national experts and a special review meeting of the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital (Hainan Medical College) were sequentially convened, resulting in an approval document registered as AF/SC-08/01.0/2022-11-01. The final application was submitted to the relevant authorities, including the Hainan Provincial Department of Science and Technology, the Hainan Provincial Health Commission, and Hainan Medical College.

Bio-safety standards and management

An isolated research infrastructure was established and managed in accordance with standards for Category B infectious diseases classified by the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases.22 The entire study was performed within a base separated from the host hospital. Routine human organ donation, porcine kidney procurement, xenotransplantation, postoperative care, and scientific observation, were all performed in separate units. The porcine and human remains as well as related medical wastes were cremated, and the entire procedure was conducted in a closed system.

Selection of gene-engineered pigs

Two genetically modified Bama miniature pigs were created by Clonorgan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., located in Chengdu, China (Figures S4 and S5), and housed in the DPF facility. The donor pigs were transported separately from Chengdu to an SPF standard facility at Hainan Medical University under strictly controlled conditions. During land-air-land travel, precautions were taken to ensure that the donor pigs were isolated from other animals.

Pig 1 was male, 662 days old, weighing 55kg with blood type O; this pig was selected from animals with TKO of three genes (GGTA1, β4GalNT2 and CMAH); one gene (hCD55) was transferred (Figures S4 and S5).

Pig 2 was female, 447 days old, weighing 60kg with blood type A. This was the only suitable candidate available at that time and had been modified by three genes TKO (GGTA1, β4GalNT2 and CMAH) and two genes (hCD55/hTBM) transferred (Figures S4 and S5).

Recruitment of human brain-dead organ donors

From January 1, 2021, the Organ Procurement Organization of Hainan Province launched a 3-year suitable-donor recruiting policy. From January 1, 2021, to June 13, 2023, 224 donations were enlisted. Of these, 39 donors were enrolled, and 2 were supported by the generous permission of their next of kin as participants in this study. Successful bilateral kidney donation was performed in November 2022 and June 2023, respectively, and the decedents were subsequently reallocated to the pre-clinical xenotransplantation trials.

Case 1 was male, 68 years old, blood type A, and had suffered from fatal brain trauma. Case 2 was also male, 55 years old, blood type B, and had suffered massive cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, and cerebral herniation. Both brain-death determinations were performed and double-checked in accordance with the Criteria and Practical Guidance for the Determination of Brain Death in Adults (2nd Edition).23

It is important to note that two human brain-dead decedents employed in the current study were initially donors of human kidneys. Following the donation for human kidney transplantation, they were subsequently reassigned to participate in pre-clinical xenotransplantation trials. Two consents were obtained, respectively, for the separate procedures. This particular situation distinguishes our study from previous reports by the NYU1 and UAB2,5 groups, as they considered brain-dead human subjects ineligible for human donation.

Method details

Porcine pathogenic microbial surveillance

The ear tissues, nasal swabs, and sera from donor pigs were used to detect porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) type A/B/C, PCMV/PRV, influenza A, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, porcine circovirus type 1/2/3, and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus pre-transplantation (Table S1). Samples taken from xenografts and recipient heart, liver, spleen, lung and serum were tested for pathogenic microorganisms when the study was terminated (Table S2). The nest PCR method was used to detect PCMV/PRV.24 Specifically, a genomic DNA extraction kit was used to extract the total genomic DNA of the sample, and nested PCR to screen for PCMV/PRV DNA in the total DNA. For the first run of PCR, the total genomic DNA of the sample was used for the template, and PCMV-P1-1 (5′- CGTGGGTTACTATGCTTCTC-3') and PCMV-P1-2 (5 ′- CTTTCTAACGAGTTCTACGC-3') were used for primers (Table S3). PCR was performed at 94°C for 3 min; followed by 35 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, 68°C for 30 s; and a final extension of 68°C for 5 min; For the second PCR run, the template was the PCR product of the first run, with PCMV-P2-1 (5′- TGGCTCAGGAAGAGAAAGGAAGTG-3') and PCMV-P2-2 (5′- GACGAGAGGACATTGTTGATAAAG-3') as primers. PCR was performed at 94°C for 3 min; followed by 35 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 58°C for 30 s, 68°C for 30 s; and a final extension of 68°C for 5 min. PCR products were electrophoresed in a 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light on a Bio-Rad gel imaging system, then finally confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Detection of the expression of Gal, Sda, Neu5Gc, hCD55, and hTBM on donor pig VECs

The vascular endothelial cells (VECs) of Donor 1 and Donor 2 pigs were isolated, and PBMCs were isolated from the whole blood of each pig. Pig VECs were stained for the expression of Gal (by isolectin BSI-B4, 1:500, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), Sda (with Dolichos biflorus agglutinin, DBA, 1:1000, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA), and Neu5Gc (with chicken anti-Neu5Gc mAb, 1:800, Biolegend, San Diego, CA). The expression of human CD55 was detected by using an allophycocyanin (APC)- conjugated anti-human CD55 (1:100, Biolegend, San Diego, CA) and APC-conjugated anti-human CD141 (TBM) antibody (1:100, BD Bioscience, San Francisco CA, USA). Samples were analyzed on a flow cytometer (Cytoflex S, Beckman Coulter, USA), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar, San Carlos, CA); results are expressed as the geometric mean.

Surgery

In a deceased human, a mid-abdominal skin incision was made following standard organ donation procedures. Bilateral kidney retrieval was then performed in accordance with established protocols. Subsequently, the kidneys were allocated through the China Organ Transplant Response System to our transplantation center and transplanted into four patients with end-stage renal disease. At the time of this paper submission, all recipients exhibited normal kidney function. Two recipients who received kidneys from Case 1 were followed up for one year, and the other two recipients who received kidneys from Case 2 were followed up for 6 months. All four recipients remain stable, with serum creatinine levels ranging from 100 to 110 μmol/L. There were no significant infections or rejections during the follow-up period.

The porcine kidney procurement procedure mimics a clinical living kidney retrieval protocol conducted under general anesthesia and open surgery. Porcine kidneys were perfused with 4°C histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) solution, placed in cold HTK solution, and transported to the recipient’s operating room for implantation.

Porcine kidney transplantations follow a routine clinical protocol, with the graft located in the right retroperitoneal space. The right peritoneum was separated to fully expose the right external iliac arterial and vein. The porcine renal artery was anastomosed to the recipient’s iliac artery in an end-to-side fashion. Similarly, venous anastomosis was performed end-to-side, attaching the porcine renal vein to the side of the recipient’s iliac vein. The right porcine ureter was anastomosed to the recipient’s bladder, followed by the placement of a pair of J tubes in the renal pelvis.

Kidney 1, for Case 1, measured 13 × 6 × 4.5 cm and weighed 210g. Kidney 2, for Case 2, measured 12.5 × 7 × 4 cm and weighed 225g. The warm and cold ischemia times for Kidney 1 were 2 and 136 min, and for Kidney 2 were 1 and 222 min.

Immunosuppression regimens

For Case 1, a conventional immunosuppressive protocol used in clinical pre-sensitized renal allotransplantation was applied, including rabbit antithymocyte globulin (rATG, thymoglobulin), rituximab, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids (Figure 1). Medications that have not been approved for clinical use, such as CD40 and CD154 antibodies, were excluded. Although Case 2 was an ABO-incompatible xenotransplantation, the level of preformed anti-donor blood type antibodies was quite low. To avoid the effect of blood group antibodies on the xenograft outcome, an anti-C5 monoclonal antibody (Eculizumab, 300 mg, iv, per week) was added to the standard protocol for Case 2.

In both cases, the doses of tacrolimus were adjusted according to the blood concentration (targeted to 7–12 ng/mL) and administered via nasogastric feeding. Pulse doses of methylprednisolone (250-500 mg/d) were given when acute rejection was of concern.

Xenograft function and immunological investigation

The post-operative investigation included: 1. urine output, SCr level, platelet count, hemoglobin, and microscale albuminuria; 2. serum levels of K+, Na+, Cl-, Ca2+, and HCO3-; 3. erythropoietin (EPO); 4. prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), D-dimer, fibrinogen, and antithrombin III.

Immunological monitoring included assessment of anti-donor pig IgG and IgM antibodies, CDC, lymphocyte subset, and tacrolimus blood concentration.

Various parameters such as lymphocyte sub-population, tacrolimus concentration, creatinine levels, electrolyte balance, blood routine examination, coagulation function, arterial blood gas analysis, and EPO levels were measured at regular intervals in both xenograft transplant recipients. Baseline data were also collected before xenotransplantation. All samples were processed at the Clinical Laboratory of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University and disposed of safely after testing. The testing standards and methods aligned completely with those used in clinical kidney transplantation. The findings were reviewed by kidney transplant surgeons and critical care physicians.

Also, color Doppler ultrasonography was conducted twice daily to assess perfusion and blood flow distribution in the xenograft.

Detection of the binding of serum IgM and IgG to pig cells by flow cytometry

The binding of serum IgM and IgG to pig PBMCs was measured by flow cytometry, as previously described.8,25,26 To ensure the specificity and reliability of our assays, we utilized pooled human sera from healthy individuals as a control in our experiments. This approach allowed us to assess whether the levels of anti-donor porcine antibodies in the pre-transplant sera of brain-dead recipients were within typical population ranges, providing insight into potential immune responses during xenotransplantation in humans. In brief, 100 μL of isolated donor pig PBMCs (5 x105 cells/tube) or RBCs (5 x106 cells/tube) were incubated with 100 μL of diluted pooled human sera or decedent sera (10% for PBMCs and 25% for RBCs, final concentration, heat-inactivated for 30 min at 56°C in advance) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells incubated with 100 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) served as negative controls. After incubation, the cells were washed twice in PBS and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min. The supernatant was then discarded. To prevent non-specific binding, 200 μL of 10% heat-inactivated goat serum (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was added, and incubation was performed for 15 min in the dark at 4°C. After washing with FACS buffer, the cells were incubated for 30 min with donkey anti-human IgM (1:1000) conjugated to Alexa 647 or goat anti-human IgG (1:1600) conjugated to Alexa 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA). After incubation, the samples were washed twice and then resuspended with 200 μL of PBS. The stained cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry (Cytoflex S, Beckman Coulter, USA); data were analyzed by FlowJo software (Treestar, SanCarlos, CA), and results are expressed as the relative geometric mean (rGM), which was calculated by dividing the geometric mean value for each sample by the negative control (no serum with secondary antibody only), as previously described25.

Pooled human sera were obtained from 20 healthy human volunteers (22–44 years of age; both genders) who had no history of previous exposure to pig antigens or to alloantigens (such as blood transfusions, a previous failed renal allograft, or pregnancy). When required, decomplementation was carried out by heat-inactivation for 30 min at 56°C. All procedures involving humans were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and had no adverse effects on the subjects.

Detection of human serum CDC in pig PBMCs by flow cytometry

PBMCs (5 × 105 cells in 250μL of FACS buffer) were incubated with 50 μL of heat-inactivated human serum or decedent sera at 4°C for 1 h. After washing with PBS, FACS buffer (200 μL) and rabbit complement (50 μL, Cedarlane, Hornby, CA, USA) were added (final concentration, 20%), and incubation was carried out at 37°C for 30 min. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated in the dark at 4°C for 15 min with propidium iodide; finally, 200 μL of FACS buffer was added. Flow cytometry was then carried out using a BD FACSCelesta (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

Detection of anti-A antibody levels by flow cytometry using human type A RBCs

The concentration of anti-A antibodies in sera taken from the potential recipients was evaluated by measuring the binding of antibodies to human type A1 reagent RBCs (Shanghai Blood/Biomedical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, CHN). In brief, serially diluted serum (50 μL) from Case 2 was incubated with 50 μL of human type A1 RBCs (1 × 107/mL) for 30 min at 4°C and subsequently washed twice in FACS buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin). The binding of anti-A antibodies was measured by indirect flow cytometry using donkey anti-human IgM (1:1000) or goat anti-human IgG (1:1000) antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA). A minimum of 10,000 events were acquired by the flow cytometer (BD FACSAria Flow Cytometer, BD Biosciences, CA, USA); results are expressed as the geometric mean.

Histopathology

Needle core biopsies and autopsy examinations were performed for both xenografts. All specimens were examined by routine staining, immunofluorescent staining, immunohistochemical staining, and EM. Histopathological sections were examined by a renal pathologist, and lesions were classified and scored according to the Banff 2019 Schema.27

For light microscopy, 10% buffered formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections were processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Immunofluorescent staining for Gal, Sda, Neu5Gc, hCD55, hTBM, IgG, IgM, C3c, and C5b-9 proteins was performed on frozen or paraffin-embedded sections (−80°C) as previously reported. Immunohistochemical staining for C4d, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD16, and CD68 proteins was performed on paraffin-embedded sections using immunoperoxidase methods, as described previously.28

The primary antibodies included: anti-IgM (polyclonal rabbit anti-human IgM, Dako-Agilent), anti-IgG (goat anti-human IgG, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA), anti-human C4d rabbit monoclonal antibody (clone A24-T, Abcam), anti-CD68 (clone KP1, GeneTech), anti-CD4 (clone EP204, ZSGB-BIO), anti- CD8 (clone SP16, ZSGB-BIO), anti-CD3 (clone GR107, GeneTech), anti-CD16 (clone EP364, GeneTech), anti-CD55 (clone BRIC 216, Santa Cruz), anti- TM (clone SC-13164, Santa Cruz), anti-Neu5Gc (clone Poly21469, Biolegend), Isolectin BSI-B4 (L2895-1, Sigma-Aldrich), and Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (FL-1031-5, Vector).

Experimental endpoints

The preset endpoint was irreversible graft dysfunction unless one of the following scenarios occurred: heart-lung dysfunction, uncontrollable infections, or termination requested by the next of kin or the ethics committee.

Quantification and statistical analysis

If not explicitly stated, figures are presented as mean ± SEM. p-Values are determined using unpaired two-tailed t-tests assuming normal distributions, or two-way ANOVA mixed-model. Statistical calculations are performed in Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla CA). Significance was set at p < 0.05. Time-course data, such as electrolyte levels, coagulation parameters, and inflammatory cytokines, were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA to account for within-subject correlations over time. Where appropriate, post hoc corrections were applied to control for multiple comparisons. Data were visualized using scatterplots, line graphs, and bar charts, with error bars representing either SD or IQR, as specified in the figure legends. Where relevant, individual data points are shown to provide insight into the variability within groups.

Published: September 23, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101744.

Contributor Information

Yi Wang, Email: wayne0108@126.com.

Kang Zhang, Email: kang.zhang@gmail.com.

Zhonghua K. Chen, Email: zc104126@126.com.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Montgomery R.A., Stern J.M., Lonze B.E., Tatapudi V.S., Mangiola M., Wu M., Weldon E., Lawson N., Deterville C., Dieter R.A., et al. Results of two cases of pig-to-human kidney xenotransplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:1889–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2120238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porrett P.M., Orandi B.J., Kumar V., Houp J., Anderson D., Cozette Killian A., Hauptfeld-Dolejsek V., Martin D.E., Macedon S., Budd N., et al. First clinical-grade porcine kidney xenotransplant using a human decedent model. Am. J. Transplant. 2022;22:1037–1053. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moazami N., Stern J.M., Khalil K., Kim J.I., Narula N., Mangiola M., Weldon E.P., Kagermazova L., James L., Lawson N., et al. Pig-to-human heart xenotransplantation in two recently deceased human recipients. Nat. Med. 2023;29:1989–1997. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loupy A., Goutaudier V., Giarraputo A., Mezine F., Morgand E., Robin B., Khalil K., Mehta S., Keating B., Dandro A., et al. Immune response after pig-to-human kidney xenotransplantation: a multimodal phenotyping study. Lancet. 2023;402:1158–1169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locke J.E., Kumar V., Anderson D., Porrett P.M. Normal Graft Function After Pig-to-Human Kidney Xenotransplant. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:1106–1108. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NYU Langone Health. Two-Month Study of Pig Kidney Xenotransplantation Gives New Hope to the Future of the Organ Supply. https://nyulangone.org/news/two-month-study-pig-kidney-xenotransplantation-gives-new-hope-future-organ-supply.

- 7.Jones-Carr M.E., Fatima H., Kumar V., Anderson D.J., Houp J., Perry J.C., Baker G.A., McManus L., Shunk A.J., Porrett P.M., et al. C5 inhibition with eculizumab prevents thrombotic microangiopathy in a case series of pig-to-human kidney xenotransplantation. J. Clin. Invest. 2024;134 doi: 10.1172/JCI175996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng H., Li T., Du J., Xia Q., Wang L., Chen S., Zhu L., Pan D., Wang Y., Chen G. Both Natural and Induced Anti-Sda Antibodies Play Important Roles in GTKO Pig-to-Rhesus Monkey Xenotransplantation. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:849711. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.849711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada K., Yazawa K., Shimizu A., Iwanaga T., Hisashi Y., Nuhn M., O'Malley P., Nobori S., Vagefi P.A., Patience C., et al. Marked prolongation of porcine renal xenograft survival in baboons through the use of alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout donors and the co-transplantation of vascularized thymic tissue. Nat. Med. 2005;11:32–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng H., Zhang M., Du J., Li T., Chen S., Zhu L., Hu Z., Yang Y., Pan D.P., Wang Y., Chen G. Swine leukocyte antigen (SLA) induces significant antibody production after pig-to-rhesus monkey kidney xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2023;107:100. (Abstract #312.9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li T., Feng H., Du J., Jiang H., He S., Pan D., Chen G., Wang Y. Antibodies to unknown antigens on GTKO/β4GalNT2KO pig cells are associated with AHXR after pig-to rhesus monkey kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2023;107:55. (Abstract #217.4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halecker S., Hansen S., Krabben L., Ebner F., Kaufer B., Denner J. How, where and when to screen for porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) in donor pigs for xenotransplantation. Sci. Rep. 2022;12 doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-25624-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohiuddin M.M., Singh A.K., Scobie L., Goerlich C.E., Grazioli A., Saharia K., Crossan C., Burke A., Drachenberg C., Oguz C., et al. Graft dysfunction in compassionate use of genetically engineered pig-to-human cardiac xenotransplantation: a case report. Lancet. 2023;402:397–410. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00775-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamada K., Tasaki M., Sekijima M., Wilkinson R.A., Villani V., Moran S.G., Cormack T.A., Hanekamp I.M., Hawley R.J., Arn J.S., et al. Porcine cytomegalovirus infection is associated with early rejection of kidney grafts in a pig to baboon xenotransplantation model. Transplantation. 2014;98:411–418. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffith B.P., Goerlich C.E., Singh A.K., Rothblatt M., Lau C.L., Shah A., Lorber M., Grazioli A., Saharia K.K., Hong S.N., et al. Genetically Modified Porcine-to-Human Cardiac Xenotransplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;387:35–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto T., Hara H., Foote J., Wang L., Li Q., Klein E.C., Schuurman H.J., Zhou H., Li J., Tector A.J., et al. Life-supporting kidney xenotransplantation from genetically engineered pigs in baboons: A comparison of two immunosuppressive regimens. Transplantation. 2019;103:2090–2104. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenson D., Hisadome Y., Santillan M., Iwase H., Chen W., Shimizu A., Schulick A., Gu D., Akbar A., Zhou A., et al. Consistent survival in consecutive cases of life-supporting porcine kidney xenotransplantation using 10GE source pigs. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:3361. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47679-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto T., Iwase H., Patel D., Jagdale A., Ayares D., Anderson D., Eckhoff D.E., Cooper D.K.C., Hara H. Old World Monkeys are less than ideal transplantation models for testing pig organs lacking three carbohydrate antigens (triple-knockout) Sci. Rep. 2020;10:9771. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper D.K.C., Kobayashi T. Xenotransplantation experiments in brain-dead human subjects-A critical appraisal. Am. J. Transplant. 2024;24:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Expert Consensus on Xenotransplantation China Organ Transplantation Development Foundation. 2022-04-06. https://www.cotdf.org.cn/article/1214 (in Chinese)

- 21.Opinions on strengthening ethical governance of science and technology . General Office of the State Council; 2022-No10. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2022/content_5683838.htm General No:1765) 2022-4-19, (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Law of the People's Republic of China on the Prevention and Control of Infectious. 2013. http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c2/c238/202001/t20200122304251.html (in Chinese)

- 23.Brain Injury Evaluation Quality Control Center of National Health Commission; Neurocritical Care Committee of the Chinese Society of Neurology (NCC/CSN); Neurocritical Care Committee of China Neurologist Association (NCC/CNA) Criteria and practical guidance for determination of brain death in adults (2nd edition) Chinese Medical Journal. 2019;132:329–335. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X., Liao S., Zhu L., Xu Z., Zhou Y. Molecular epidemiology of porcine Cytomegalovirus (PCMV) in Sichuan Province, China: 2010-2012. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen G., Qian H., Starzl T., Sun H., Garcia B., Wang X., Wise Y., Liu Y., Xiang Y., Copeman L., et al. Acute rejection is associated with antibodies to non-Gal antigens in baboons using Gal-knockout pig kidneys. Nat. Med. 2005;11:1295–1298. doi: 10.1038/nm1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li T., Feng H., Du J., Xia Q., Cooper D.K.C., Jiang H., He S., Pan D., Chen G., Wang Y. Serum Antibody Binding and Cytotoxicity to Pig Cells in Chinese Subjects: Relevance to Clinical Renal Xenotransplantation. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:844632. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.844632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loupy A., Haas M., Roufosse C., Naesens M., Adam B., Afrouzian M., Akalin E., Alachkar N., Bagnasco S., Becker J.U., et al. The Banff 2019 Kidney Meeting Report (I): Updates on and classification of criteria for T cell– and antibody-mediated rejection. Am. J. Transplant. 2020;20:2018–2331. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Song S., Zhong S., Xiang Y., Li J.H., Guo H., Wang W.Y., Xiong Y.L., Li X.C., Chen Shi S., Chen X.P., Chen G. Complement inhibition enables renal allograft accommodation and long-term engraftment in presensitized nonhuman primates. Am. J. Transplant. 2011;11:2057–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report any original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.