Abstract

Background

Brassica juncea (L.) Czern is an important oilseed crop affected by various abiotic stresses like drought, heat, and salt. These stresses have detrimental effects on the crop’s overall growth, development and yield. Various Transcription factors (TFs) are involved in regulation of plant stress response by modulating expression of stress-responsive genes. The myeloblastosis (MYB) TFs is one of the largest families of TFs associated with various developmental and biological processes such as plant growth, secondary metabolism, stress response etc. However, MYB TFs and their regulation by non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in response to stress have not been studied in B. juncea. Thus, we performed a detailed study on the MYB TF family and their interactions with miRNAs and Long non coding RNAs.

Results

Computational investigation of genome and proteome data presented a comprehensive picture of the MYB genes and their protein architecture, including intron-exon organisation, conserved motif analysis, R2R3 MYB DNA-binding domains analysis, sub-cellular localization, protein-protein interaction and chromosomal locations. Phylogenetically, BjuMYBs were further classified into different subclades on the basis of topology and classification in Arabidopsis. A total of 751 MYBs were identified in B. juncea corresponding to 297 1R-BjuMYBs, 440 R2R3-BjuMYBs, 12 3R-BjuMYBs, and 2 4R-BjuMYBs types. We validated the transcriptional profiles of nine selected BjuMYBs under drought stress through RT-qPCR. Promoter analysis indicated the presence of drought-responsive cis-regulatory components. Additionally, the miRNA-MYB TF interactions was also studied, and most of the microRNAs (miRNAs) that target BjuMYBs were involved in abiotic stress response and developmental processes. Regulatory network analysis and expression patterns of lncRNA-miRNA-MYB indicated that selected long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) acted as strong endogenous target mimics (eTMs) of the miRNAs regulated expression of BjuMYBs under drought stress.

Conclusions

The present study has established preliminary groundwork of MYB TFs and their interaction with ncRNAs in B. juncea and it will help in developing drought- tolerant Brassica crops.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-024-05736-8.

Keywords: MYB domain, lncRNAs, Abiotic stress, miRNA targets, Cis-regulatory elements, Expression profile, Brassica juncea

Introduction

Transcription factors (TFs) are essential in determining the expression of genes, and it is reported that the quantity of TFs is precisely correlated to the genome size of the organism [1]. TF normally has two functional domains, one that binds to DNA and the other activation domain, which is involved in transcriptional stimulation and repression [2]. Both of these domains, are complemented by other hallmark proteins which either stimulate or inhibit transcription depending on the internal and external factors [3, 4]. The MYB superfamily is one of the most abundant and diverse TF families reported in plants till date [5]. The first MYB identified in the avian myeloblastosis virus was the v-MYB, an ‘oncogene’ [5]. The preliminary MYB described successfully in plants was Zea mays C1, a homolog of the c-MYB in mammalian species and regulates anthocyanin production [6]. The proteins of the MYB TF family have a DNA-binding domain (DBD) that is about 50–53 amino acid residues long [7] and during transcription, the binding region of the DNA alpha-helix binds directly to a primary region of the molecular DNA [8], . The MYBs family is categorized into 4 groups based on the proportion of contiguous MYB repetitions, notably 1R-MYB, 2R-MYB, 3R-MYB, and 4R-MYB, which include 1, 2, 3, and 4 MYB repeats, respectively [9]. Proteins of the R1R2R3 domain are predominantly found in animals, whereas plants have more prominent R2R3 domain proteins [6, 9, 10].

Several MYBs have been reported to control plant’s response to climatic challenges such as salinity, cold, and drought. Among the abiotic stresses, droughts have severely harmed crops in a huge proportion of agriculturally productive regions across the world [11]. By 2050, the world’s population is predicted to exceed nine billion; therefore, agricultural yield in drought-prone areas must be increased by 40% [12]. Manipulation of expression of MYB TFs can be one of the promising strategies to develop drought-tolerant crops. For instance, MbMYB4 and MbMYB108 from Malus baccata were overexpressed in Arabidopsis leading to an enhanced tolerance against drought and cold stress [13, 14]. Overexpression of FvMYB44 and FvMYB82 from Fragaria vesca considerably increased the tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis in response to low temperature and salinity stress [15, 16]. Transgenic cotton and tobacco plants overexpressing GbMYB5 showed increased resistance to drought conditions [17]. AtMYB96 alleviated drought-induced sensitivity by modulating the auxin and abscisic acid (ABA) hormones signals and enhanced cuticular wax deposition [18]. Overexpressing OsMYB91 plants accumulated intrinsic ABA under controlled circumstances thereby providing resistance to salinity [19]. Overexpressing OsMYB3R-2 in rice improved cold tolerance and enhanced the cell mitotic index by activating several G2/M phase specific genes [20]. Besides their role in abiotic stress tolerance, MYBs are reported to be involved in other diverse physiological processes such as OsCSA a R2R3-MYB identified in Oryza sativa, is reported to have a role in the development of pollen and seeds [21]. ZmMYB46 and OsMYB46 activated the secondary cell wall biosynthesis in Arabidopsis [22]. A further investigation revealed that GmMYB100 and VvMYB4-like inhibited plant flavonoid production by negatively regulating the flavonoid biosynthetic genes [23, 24]. MYB gene family has previously been discovered in various plant species, notably in Arabidopsis thaliana [25], Solanum lycopersicum [26], Oryza sativa [27], Solanum tuberosum [28] etc. Furthermore, R2R3-MYB family TFs have previously been identified in Brassica species for example in B. oleracea, B. napus, B. rapa B. juncea, B. carinata, and B. nigra [29].

The Brassicaceae family has roughly 372 genera and 4060 species. Genus Brassica is economically important as the majority of its species are used as crops, condiments, oils etc [30, 31]. Indian mustard or brown mustard (B. juncea, 2n = 36, AABB) is an allotetraploid developed through hybridization of two plant species B. nigra (2n = 16, BB) and B. rapa (2n = 20, AA) [32]. India, Canada, and China are the major countries that grow B. juncea widely, and is a commercially and nutritionally significant annual/biennial oilseed crop. Being the most important oilseed crop of arid and semiarid regions, B. juncea is often exposed to water scarcity imposed by prevailing drought conditions. Generating drought-tolerant/resistant plants by exploiting TF regulons involved in regulating drought response can be a promising strategy to mitigate the problem of cultivation and production of Brassica crops in water-scarce regions. MYB TF family has not been fully exploited for its potential involvement in enhancing abiotic-stress tolerance in Brassica. In B. campestris, BcMYB44 has been reported to regulate drought tolerance and anthocyanin synthesis [33, 34]. Another study in Brassica napus has previously reported the drought responsive role of MYB-related gene BnMRD107 [35]. Furthermore, BnaMYB78 a R2R3-MYB type gene regulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and hypersensitivity in Brassica napus [36]. Recent studies have demonstrated that ncRNAs are essential for controlling the expression of certain genes in response to stressful conditions. ncRNAs are a family of RNA molecules found in many different organisms that cannot encode proteins [37]. miRNAs regulate the mRNA targets via cleaving and/or translational inhibition [38]. Further, lncRNAs are approximately 200 nucleotide long RNA molecules said to play an important role in the regulatory pathways including stress response in plants [39]. LncRNAs may regulate the function of miRNAs via target mimicry by inhibiting the interaction/targeting phenomenon of miRNA and target mRNA, and also act as precursor to miRNAs [40, 41]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the regulatory networks formed by interacting lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs molecules in response to abiotic stresses, especially heat and drought in Triticum aestivum L. [42, 43].

The current study focusses on highlighting the role of MYB TFs and their interaction with ncRNAs during the drought stress response in B. juncea. In current research, 751 MYBs were identified in B. juncea, and their chromosomal locations were pinpointed in sub-genomes A and B. Further, phylogenetic relatedness suggested MYB clustering into separate clades, which received additional validation by the classification of genes in gene ontology, motif analysis, and gene architecture. The investigation of cis-regulatory elements in BjuMYB promoters, protein-protein interaction and miRNA-MYB TF interaction suggested their potential regulatory roles in abiotic and biotic stimuli, and developmental processes. Regulatory interaction examination of lncRNAs-miRNAs-MYBs suggested potential eTMs candidates of the miRNAs regulating the expression of BjuMYBs under drought stress and validated through RT-qPCR. Altogether, our investigation revealed the importance of MYB TFs and their regulatory interaction with ncRNAs under drought stress, which can help further in the improvement of Brassica crops using molecular approaches.

Materials and methods

Plant growth, treatment and RNA isolation

Seeds of B. juncea cv. varuna were originally procured from Punjab Agriculture University, Ludhiana, India and used for experimentation. Seeds were grown in pots containing soil: soil rite in the mixture 1:2 in the ideal conditions of a photoperiod of [16 h light and 8 h and] and a temperature of [18–24 °C] in a plant growth chamber (Percival, USA). The plants were subjected to short- and long-term drought stress treatments in triplicates at the four-leaf stage. For shorter duration, plants were treated with 20.0% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6000 solution for 2-time points: 4 h and 8 h; longer duration drought condition was provided by with-holding water for seven days. The control plants were regularly watered and kept in the growth chamber under the same condition. Leaves from the drought-exposed and control plants were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until needed. Total RNA from leaf tissue from both drought-stressed and control plants was extracted following the method described by Ghawana et al. [44]. During cDNA synthesis, a Superscript III first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen USA) was used.

Mining, chromosomal position, mapping and nomenclature of MYB TF family in B. Juncea

We retrieved the proteome data of B. juncea from Brassica Database (BRAD), (http://brassicadb.cn/) and using StandAlone Blast, a local database for the same was created [45]. Consequently, we retrieved the protein sequences of MYB and MYB-related genes of B. rapa, B. napus, B. oleracea, A. lyrata, and (A) thaliana species from the Plant Transcription Factor Database (PlantTFDB) (http://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/) to serve as reference sequences. To identify the putative BjuMYBs, we performed a Blastp search of reference protein sequences compared to the (B) juncea proteome using a cut-off e-value of 1e-05 [46].

The putative BjuMYBs were investigated for the presence of specific domains of the MYB protein using NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml), pfam (https://pfam-legacy.xfam.org/), InterProScan (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/search/sequence/), SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and ScanProsite (https://prosite.expasy.org/scanprosite/) databases [47–51]. The chromosomal location of MYBs on the B. juncea sub-genomes A and B was retrieved by searching the gene ID in BRAD. Mapping was done by using the TBtools Software [52]. The nomenclature of the identified BjuMYB genes followed the Brassica species nomenclature guidelines [53].

Phylogenetic analysis and profiling of BjuMYB conserved amino acids

The sequences of MYB proteins from (A) thaliana and (B) juncea were arranged by MUSCLE programme, and a phylogenetic tree with the neighbour joining approach was constructed and evaluated by thousand bootstrap replicates via Mega7software (https://www.megasoftware.net/) [54]. The R2 and R3 repeats in R2R3-MYB domain proteins were used to display the amino acid residue distribution with the aid of the WebLogo website (https://weblogo.berkeley.edu/) [55].

MYB protein characterization, motif analysis and protein-protein interactions

The physical and chemical attributes of BjuMYBs were inspected by utilising ProtParam ExPasy server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) which predicted properties like molecular weight, grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), amino acid composition, isoelectric point (pI), instability index [56], . The localization of MYB protein in various cellular compartments was anticipated by using the ProtComp version 9.0 server (http://www.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=protcomppl&group=programs&subgroup=proloc) and WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) [57]. The pattern of conserved motifs in sequences of MYB proteins was investigated with MEME-Suite version 5.4.1 (http://meme-suite.org/) using the following parameters: 5 motifs and breadth ranging from 20 to 200 [58]. The conserved pattern of motifs was examined with the help of the Pfam webserver, ScanProsite, and InterProScan. The conserved motifs in BjuMYBs were analysed by TBtools software [51]. The STRING Version 12.0 (https://string-db.org/) was used for carrying out the protein-protein interaction network [59].

Gene structure organization, promoter analysis and gene ontology

The gene architecture of BjuMYBs was elucidated by aligning genome-cDNA using Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 (GSDS2.0) (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/) [60]. The cis-elements were analysed by retrieving the 1.5 kb genomic sequence ahead of the initiation codon. Regulatory elements were then predicted using databases, PLACE (https://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/?action=newplace) and PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) [61, 62]. The function annotation of BjuMYBs was predicted using OmicsBox (https://www.biobam.com/omicsbox/). Gene annotation was organised into three distinct categories: molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components.

Differential expression analysis and RT-qPCR in drought conditions

To determine the transcript abundance of BjuMYBs under drought stress, we used RNA sequencing data from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra)database associated with project number SRP051212 [63]. For expression analysis, Trinity-V 2.03 software was used. To evaluate the level of expression of genes, FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million) was first determined using RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization) [64]. Then, EdgeR was used to investigate the varying expression of MYB genes by calculating four folds change with p < 0.05. We used TBtools software to develop the heat maps [52]. For RT-qPCR analysis, the reference gene TIPS-41, a Tonoplastic intrinsic protein, was used to normalize the transcript level [65]. Primer 3 software was used to design the primers (https://primer3.ut.ee/) (Supplementary Table S1). Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR detection system was used to perform RT-qPCR. The PCR procedure was carried out according to the following conditions: 95 °C for 7 min, followed by 39 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, Tm for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The expression fold change of the differentially expressed transcripts was estimated with the help of the 2-∆∆CT method [66].

miRNA target prediction

miRNA targets were predicted using default parameters at the plant small RNA Target analysis server (psRNATarget server) (https://www.zhaolab.org/psRNATarget/) [67]. For this, the reported Bju- miRNAs (39 novel and 51 conserved miRNAs) [68] were used for the target prediction in nineteen differentially expressed BjuMYBs. Cytoscape software (https://cytoscape.org/) was used to illustrate the miRNA-mRNA interactions [69].

Regulatory network of lncRNAs-miRNAs-MYB TFs and RT-qPCR validation

We investigated the co-expression analysis of drought-responsive MYB TFs with already identified drought stress-responsive lncRNAs in B. juncea [70] using the CoExpress v1.5 tool on the basis of FPKM data and a Pearson-correlation coefficient of ≥ 0.7 [71]. Furthermore, we predicted target sites for drought-responsive Bju-miRNAs in the Bju-lncRNAs using the default parameter on the psRNATarget server (https://www.zhaolab.org/psRNATarget/) [67]. Additionally, the eTMs (endogenous target mimics) were studied employing the TAPIR server (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/tapir/) [72] with default parameter for Bju-miRNAs. The miRNAs-lncRNAs-MYB TFs interaction network was visualised using the Cytoscape software (https://cytoscape.org/) [69]. Based on our insilico prediction, we selected two regulatory interactions (named Regulatory Network I and II this point onwards) to validate their competing relationship through RT-qPCR. The expression analyses of miRNAs, lncRNAs, and MYB TFs were studied and U6 gene as an internal control. The primers used in this study are provided in the Supplementary Tables 1.

Statistical analysis

The statistical study was conducted using GraphPad Prism software, which calculated the mean and standard deviations (SD) of biological and technical triplicates. Furthermore, a two-way ANOVA test was used to measure statistics variance relative to controls, which was noted at ***p-value ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01 and *p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Identification and chromosomal mapping of BjuMYBs

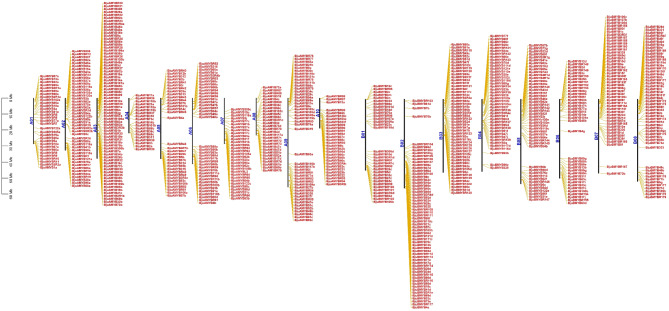

The BLASTp search led to the identification of 751 MYBs in B. juncea. Validation of particular MYB or MYB-like DNA-binding domains via Pfam, NCBI CDD, ScanProsite, SMART and InterProScan softwares confirmed the existence of MYB domains (PF00249 and PF13921). The 751 BjuMYBs were further categorised into 1R-BjuMYBs (297,39.5%), R2R3-BjuMYBs (440, 58.5%), 3R-BjuMYBs (12, 1.59%), and 4R-BjuMYBs (2, 0.26%) (Supplementary Table S2). The sub-genomes of B. juncea, A and B, showed the presence of 369 and 366 BjuMYBs, respectively, and 16 BjuMYBs in the contig region (Fig. 1). In the context of sub-genomes, the highest (69) and lowest (17) gene counts were found on chromosomes 3 A and 4 A, respectively, while the highest (60) and lowest (33) gene counts were found on chromosomes 2B and 1B, respectively.

Fig. 1.

The chromosomal positions of BjuMYBs in B. juncea sub-genomes A and B were mapped by TBtools software. The chromosome numbers are shown on the left side of each chromosome (a vertical bar in black) in blue, and the gene name is shown on the right side of each chromosome in red. The scale bar is in megabytes (Mb) on the left side

Physico-chemical characterization and motif analysis of MYB proteins

In our study, the predicted protein length, MW, GRAVY, instability index, and pI of MYB proteins varied from 50 to 1817 aa, 6.08 to 200.39 kDa, -1.39 to -0.10, 28.79 to 123.8, and 4.32 to 10.06, respectively (Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, the sub-cellular localization prediction showed that the majority of BjuMYB TFs, nearly 723 (96.27%) were localized in the nucleus, and the remaining 28 were localized in cytoplasm (10), chloroplast (1), Extracellular (5), mitochondria (10), and plasma-membrane (2) (Supplementary Table S3).

Five conserved motifs were identified in the MYB proteins using MEME-Suite tool (Supplementary Fig. 1). Motifs 1, 2, and 3 were predicted to be associated with the Myb-type HTH domain in the majority of R2R3-BjuMYB proteins. However, in a small subset of proteins, such as BjuAMYB93a, BjuAMYB314 and BjuAMYB32, motifs 4 (19/440) and 5 (21/440) were found to be associated with the Myb-type HTH and SANT domains, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the pattern of conserved motifs of other BjuMYB proteins (1R-BjuMYB and 3R-BjuMYB, 4R-BjuMYB) were also predicted (Supplementary Fig. 1b and c(i), (ii)). Motifs 4, 1, and 2 were detected to be associated with the Myb-type HTH domain in the majority of 1R-BjuMYB proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1b). In addition, it was predicted that motifs 1, 2 and 4 in 3R-BjuMYB and 1 and 2 in 4R-BjuMYB proteins were found to be associated with the Myb-type HTH and Myb-like domain (Supplementary Table S4).

Phylogenetic analysis of MYB proteins

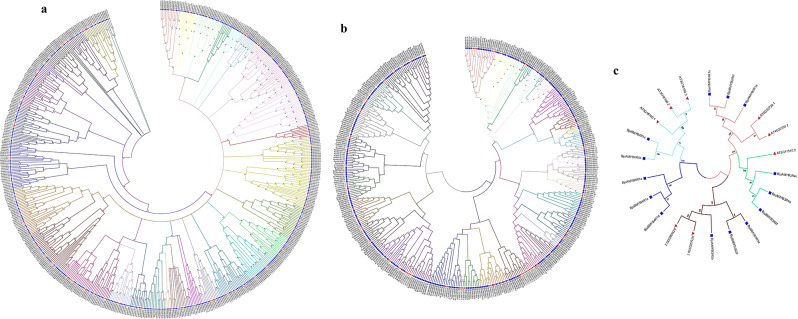

Three phylogenetic networks/trees were generated based on alignment between MYB proteins of Arabidopsis and B. juncea (Fig. 2). The first phylogenetic tree included 440 R2R3-BjuMYB from B. juncea and 141 R2R3-MYB from A. thaliana, which were further classified into 36 sub-groups (B1-B36) according to the classification of MYBs in (A) thaliana and the topology of the tree (Supplementary Table S5a). The smallest groups B31, B32, and B35, contained just one member each from (B) juncea and Arabidopsis respectively, while B10 included 47 proteins from both species. i.e., 8 of Arabidopsis and 39 of B. juncea, the largest group as illustrated in Fig. 2a.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of MYB proteins from B. juncea (Blue square) and A. thaliana (Red triangle). A neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed via MEGA7 utilising 1000 bootstrap replication. (a) R2R3-MYB proteins divided into 36 (B1-B36) subgroups, which are represented by different colours of clades; (b) 1R-MYB proteins divided into 36 (J1-J36) subgroups, which are represented by different colours of clades; (c) 3R-MYB and 4R-MYB proteins divided into 5 (A1-A5) subgroups, which are represented by different colours of clades

A total of 406 protein sequences of MYBs were included in the phylogenetic network of 1R-BjuMYB, including 297 1R-MYB from B. juncea and 109 MYB-related sequences from A. thaliana. These 406 protein sequences were divided into 36 sub-groups (J1–J36) according to the topology of the tree and classifications in (A) thaliana (Supplementary Table S5b). The smallest groups J11 contained only 2 members from (B) juncea and the largest group J33 included 21 members from both species. i.e., 5 of Arabidopsis and 16 of B. juncea, as depicted in (Fig. 2b). A total of 22 protein sequences of MYBs including (17 3R-MYB and 5 4R-MYB) from (A) thaliana and (B) juncea were used to generate the third phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2c). According to the classifications in (A) thaliana and topology of the tree, these 22 MYB protein sequences were classified into 5 Sub-groups (A1-A5) (Supplementary Table S5c). Two largest sub-groups A1 and A3 contained 5 members from both species. i.e., 2 of Arabidopsis and 3 of (B) juncea and the smallest groups A4 contained three members only from B. juncea.

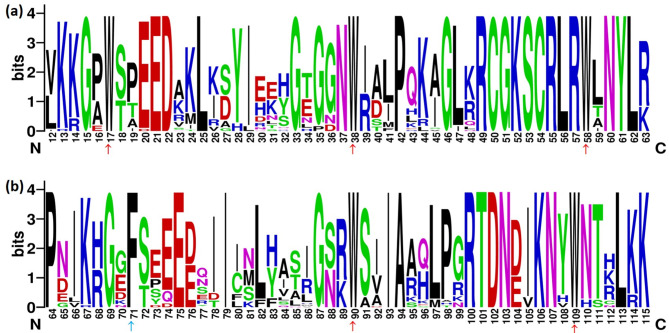

Sequence analysis of the conserved domains of R2R3-BjuMYB

Furthermore, we examined the sequences of amino acid residues contained within the R2R3-BjuMYB repeat domain. The distinguishing sequences identified in the R2 and R3 regions of Bju R2R3-MYB were [-W-(X20)-W-(X19)-W-] and [F-(X18)-W-(X18)-W-] respectively (Fig. 3a and b), respectively, wherein W denotes tryptophan (trp), F denotes phenylalanine (phe) and X symbolizes any amino acid. A similar pattern of distinguishing sequence in the R2R3 domain region has previously been reported in Vaccinium corymbosum [73]. Conserved amino acid residues present in R2R3-MYB TFs were predicted including, K-13, E-21, D-22, G-33, L-47, R-49, G-51, K-52, S-53, C-54, R-55, L-56, R-57, N-60 and L-62 in the R2 region, and G-69, E-75, G-87, N-76, I-93, A-94, P-98, G-99, R-100, T-101, D-102, N-103, K-106 and N-107 in the R3 region.

Fig. 3.

Sequence logos in MYB repeat R2 (a) and R3 (b) were generated from multiple alignments of all R2R3-BjuMYB domains. The overall height of each stack represents the sequence conservation at that position, and the bit score represents the relative frequency of the relevant amino acid residues. The conserved tryptophan residues (denoted as Trp, W) in the MYB domain are marked by red arrows, whereas the substituted amino acid residues in the R3 repeat are marked by blue arrows

Gene structure analysis

To gain a better understanding of the structural characteristics of MYB TFs, the exon and intron organisation of BjuMYBs was visualised. The 440 R2R3-BjuMYB s, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2a, had intron count ranging from 1 to 11, exceptionally, 25 introns were found in BjuAMYB3R3b. Majority of R2R3-BjuMYB had two introns (314/440) while few also showed the presence of one intron (76/440). Interestingly, 5 and 11 introns were identified in BjuAMYB16a and BjuAMYB3R2a respectively. Additionally, 14 intronless genes were also predicted in the R2R3-BjuMYBs. The characteristics of the exon and intron structural investigations of the other BjuMYBs (1R-BjuMYB, 3R-BjuMYB, and 4R-BjuMYB) were also predicted. (Supplementary Fig. 2b and c). The count of introns in 297 1R-MYBs spanned from 1 to 18, with an exception of 24 introns found in BjuAMYBR60, while 15 1R-BjuMYBs were found to be intronless. The 12 3R-BjuMYBs exhibited intron count varying from 4 to 20, while 46 introns were predicted in BjuBMYB3R3e. Furthermore, the two 4R-BjuMYBs, i.e. BjuAMYB4R1b and BjuBMYB4R1c had 5 and 6 introns, respectively (Supplementary Table S6).

Functional annotation of MYBs

In B. juncea, the protein sequences of MYBs were studied for their function elucidation. The functional annotation was arranged into 3 major categories: “Cellular component”, “Molecular function” and “Biological process” (Supplementary Figure S3a). The “Cellular component” (GO:0005575) category showed that most MYB proteins were found in subcellular regions like “nucleus” (GO:0043231), “membrane-bounded organelle” (GO:0043226), “intracellular anatomical structure” (GO:0110165), etc (Supplementary Figure S3b). The “Molecular functions” category (GO:0003674) projected MYB involvement in “transcription regulator activity” (GO:0140110), “protein binding” (GO:0005488), “DNA binding” (GO:0003677), “transcription cis-regulatory region binding” (GO:0000976), “DNA-binding transcription factor activity” (GO:0003700), etc. (Supplementary Figure S3c). The “Biological Processes” (GO:0008150) category showed the association of BjuMYBs with processes like “regulation of gene expression” (GO:0010467), “regulation of cellular metabolic process” (GO:0044237), (GO:0050794) and (GO:0019222), “regulation of biosynthetic process” (GO:0009058) and (GO:0019222), “response to hormone” (GO:00100330) and (GO:0009719), “tissue development” (GO:0048856), “response to alcohol” (GO:0010033) and (GO:1901700), “reproductive system development” (GO;0048731) and “phyllome development” (GO:0099402) and (GO:0048367), etc. (Supplementary Figure S3d).

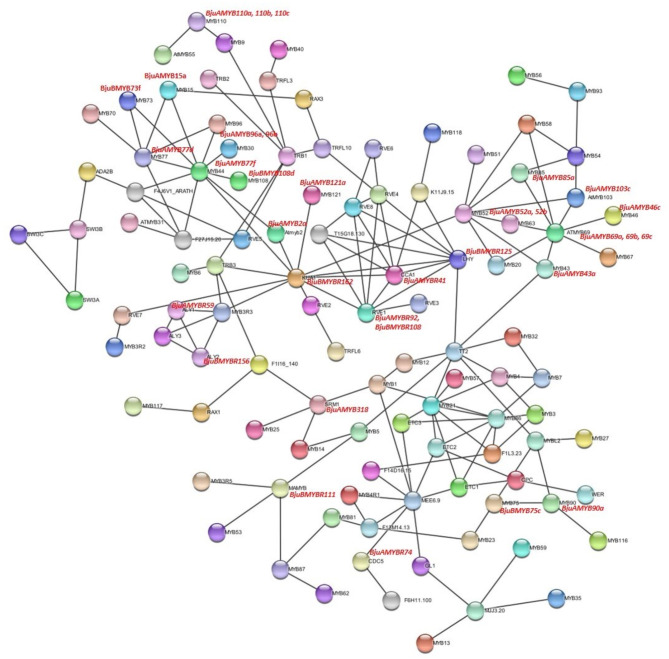

PROTEIN-protein interaction analysis

We predicted protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of 751 MYB proteins in B. juncea on the basis of interaction with MYB proteins in (A) thaliana to suggest their biological function in (B) juncea (Fig. 4). The results showed that BjuBMYB73f, BjuAMYB15a, BjuAMYB77d, BjuAMYB96a, and BjuBMYB108d interacted with MYB44 (BjuAMYB77 f), which is involved in ABA-dependent abiotic stress resistance. BjuAMYB2a, BjuAMYB121a, BjuAMYBR92, BjuBMYBR108, BjuAMYB52a, and BjuAMYB52b showed interactions with kUA1 (BjuBMYBR162), which acts as a transcriptional repressor. BjuAMYB85a, BjuAMYB52a, BjuAMYB52b, BjuBMYBR125, BjuAMYB43a, BjuAMYB46c, and BjuAMYB103c interacted with AtMYB69 (BjuAMYB69a, 69b, 69c), which is a putative R2R3 MYB transcription factor.

Fig. 4.

Protein-protein network analysis of BjuMYB proteins in B. juncea with reference species Arabidopsis

Expression analysis of BjuMYBs in drought stress

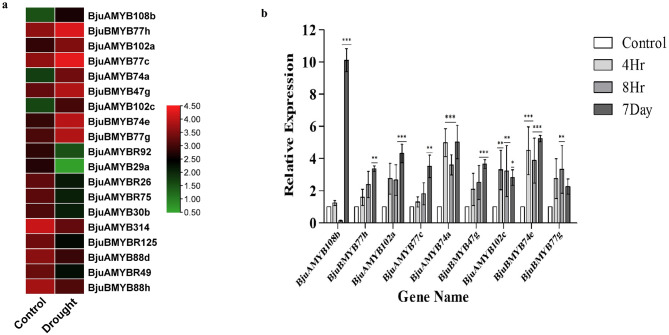

The in-silico analysis of BjuMYBs in response to drought-induced stress showed that the transcript expression of 9 and 10 BjuMYBs was upregulated and down-regulated, respectively (Fig. 5a). The nine up-regulated genes were further validated via RT-qPCR, which showed up-regulated transcript expression at 4 h, 8 h, and 7 days of drought treatment in comparison to control conditions, except BjuAMYB108b which showed decrease in expression at 8 h. The fold change in the expression of BjuAMYB74a (4.98-fold, 3.61-fold, and 5.02-fold) and BjuBMYB74e (4.34-fold, 3.73-fold, and 5.13-fold) was observed at different time points of drought stress (4 h, 8 h, and 7th day, respectively) (Fig. 5b). The relative expression of BjuAMYB108b, BjuAMYB74a, and BjuBMYB74e was first increased significantly at 4 h, then decreased at 8 h, and found to be increased on the 7th day of drought stress. Furthermore, the expression patterns of BjuBMYB77h (fold change − 1.54, 2.30, and 3.37), BjuAMYB77c (fold change − 1.28, 1.73, and 3.47) and BjuBMYB47g (fold change − 1.94, 2.37, and 3.69) showed continuous increments in response to drought stress at (4 h, 8 h, and 7th day), respectively.

Fig. 5.

Differential expression analysis of BjuMYBs in response to drought stress. (a) In-silico analysis revealed 19 differentially expressed genes in drought stress and represented as heat map using TBtools software. The scale bar on the right displays the transcript abundance from low level (Green) to high level (Red), (b) The relative expression level of BjuMYBs in B. juncea leaf tissues at different time points during drought stress was evaluated using RT-qPCR. The relative expression was determined by referencing transcription levels in control leaf tissues. The error bars represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate samples, and their statistical significance relative to the control plant are noted at (*** means p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01 and * means p ≤ 0.05)

Analysis of the BjuMYB promoter sequences

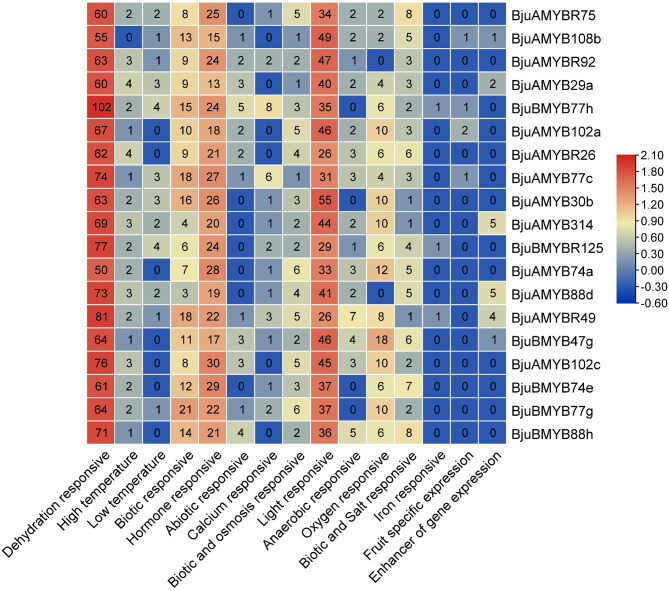

The cis-regulatory components were identified in the promoter sequences of 19 differentially expressed BjuMYBs (Fig. 6). The cis-elements were classified as responsive to hormones, biotic and abiotic stress, growth and development-responsive. The stress-responsive cis-elements were associated majorly with drought-induced stress, light, salt, wounding, temperature-related stress, osmolarity, responsiveness to anaerobic conditions, relevance to defence, and responsiveness to pathogens. A small set of the identified MYB-responsive cis-elements involved in stress response were MYBCORE, MYB2CONSENSUSAT, MYCATERD1, and MYB1AT, etc. (Supplementary Table S7). Furthermore, the BjuMYB promoters also possessed hormone-responsive cis- elements, such as auxin, gibberellin, abscisic acid, etc.

Fig. 6.

Evaluation of cis-regulatory element in the promoters of 19 differentially expressed BjuMYB in response to abiotic, biotic and hormone responses. The number of cis-acting elements in the promoter region is indicated by a number inside a square box. The scale bar on the right displays the abundance of cis-regulatory element from low level (blue) to high level (Red)

miRNA target prediction

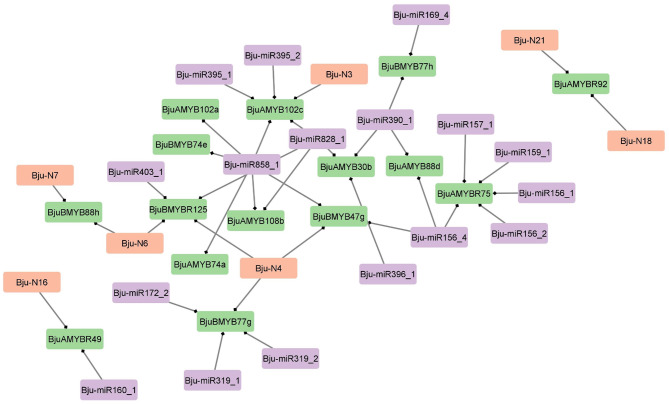

It was predicted that out of the total 24 already known miRNAs in B. juncea, i.e., 7 novel and 17 conserved, targeted 7 and 13 BjuMYB transcripts, respectively (Fig. 7). We found that 19 miRNAs were involved in cleavage inhibition while 5 inhibited target mRNAs through translational inhibition. In our study, we also found that certain miRNAs targeted multiple BjuMYBs, for example Bju- miR858_1 targeted BjuBMYB74e, BjuAMYB108b and BjuBMYB47g. (Fig. 7). Also, we found the majority of conserved and novel miRNAs targeting single BjuMYBs; for instance, Bju- miR395_1, Bju- miR159_1, and Bju- N16 targeted BjuAMYB102c, BjuAMYBR75, and BjuAMYBR49, respectively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

miRNA regulatory network of BjuMYBs represented using Cytoscape software. Conserved Bju- miRNAs (purple box), novel Bju- miRNAs (orange box) and BjuMYB targets (green box) are represented in the network

LncRNAs-miRNAs-MYB TFs interaction analysis and validation via RT-qPCR

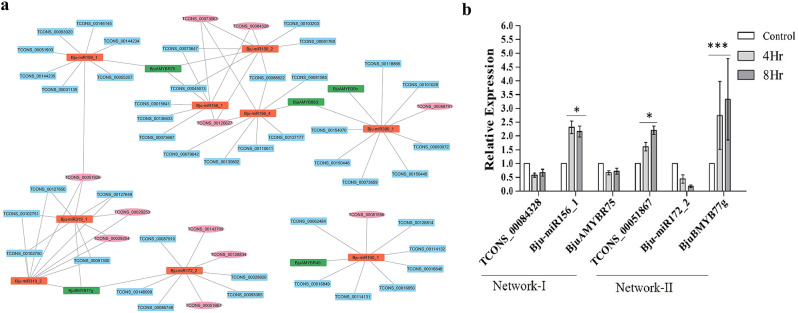

We identified drought-responsive lncRNAs co-expressing with differentially expressed MYB TFs in B. juncea, which shows the involvement of lncRNA-MYB TF pairs in plant stress responses. It was found that 11 lncRNAs (pink) co-expressed with 5 BjuMYB TFs (green) in response to drought stress (Fig. 8a). Next, we identified interactions between Bju-miRNAs and lncRNAs using the psRNATarget server (Fig. 8a). Based on our investigation, we found that 55 lncRNAs were targeted by 9 Bju-miRNAs in drought stress. Out of which, 11 drought-responsive lncRNAs were predicted to be acting as candidate eTMs for 9 Bju-miRNAs (Fig. 8a). Remarkably, we observed drought-responsive B. juncea lncRNAs that potentially interact with Bju-miRNAs, which were previously also explored in response to abiotic stresses for example Bju- miR156_2 and Bju- miR390_1 in drought and Bju- miR172_2, and Bju- miR319_2 in heat stress. Further, the expression analysis of randomly selected networks I (TCONS_00084328-Bju-miR156_1-BjuAMYBR75) and II (TCONS_00051867-Bju-miR172_2-BjuBMYB77g) was verified with RT-qPCR at 4 h and 8 h of drought treatment (Fig. 8b). We observed that the expression levels of lncRNA and MYB TF were downregulated as compared to Bju-miRNA (upregulated) in regulatory network I. Further, in Regulatory Network II, the expression levels of lncRNA and MYB TF were upregulated as compared to Bju-miRNA (downregulated).

Fig. 8.

Regulatory network analysis of (a) lncRNA (Blue), miRNAs (Red), and MYB TFs (Green) in B. juncea in response to drought stress was constructed by Cytoscape Software. lncRNAs in pink act as eTMs of Bju-miRNAs and co-expressing partners with MYB TFs, while rest of the lncRNAs (in blue) represent the targets of miRNAs, (b) The relative expression level of lncRNAs-miRNAs-BjuMYBs in B. juncea leaf tissues at different time points during drought stress was evaluated using RT-qPCR. The relative expression was determined by referencing transcription levels in control leaf tissues. The error bars represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate samples, and their statistical significance relative to the control plant are noted at (*** means p ≤ 0.001, and * means p ≤ 0.05)

Discussion

The MYB TF superfamily contributes to several biological and cellular processes like environmental response, cell differentiation, biotic and abiotic stress stimuli, defense mechanisms, etc. in plants [9, 74, 75]. Recent studies conducted in Brassica to investigate MYB TF family mainly focused on the characterization of the R2R3-MYBs and the potential role of MYBs in anthocyanin biosynthesis [29]. Another study conducted in B. juncea var tumida identified 502 MYB TFs including 23 1R-MYBs, 388 R2R3-MYBs, 16 3R-MYBs, and 4 4R-MYBs using the previously available genome assembly (Accession id: GCA_001687265.1, BioProject: PRJNA285130). The study characterized BjPHL2a and its role as a transcription inducer upon Botrytis cinerea infection [76].

In the current work, we used the latest published genome assembly of B. juncea (Accesion id: GCA_020002515.1, Bioproject: PRJNA697823), intending to understand the role of MYB TF family genes in drought stress and its regulation through interactions between small non-coding RNAs. In our study, we identified 751 MYB TFs which include 297 1R-BjuMYBs, 440 R2R3-BjuMYBs, 12 3R-BjuMYBs, and 2 4R-BjuMYBs. More than half (440/751) of the 751 identified MYB TFs were classified as R2R3-MYBs, with 1R-MYBs making up the second-largest sub-group (297/751). The R2R3-MYB subgroup was previously described as the largest sub-group of the MYB TF family in various plant species, which is consistent with our research [25, 75, 77]. The identification of only 12 3R-BjuMYB and 2 4R-BjuMYB in this research suggested that their effect may be less pronounced in plants than the R2R3-BjuMYB. Similarly, a lesser number of 3R-MYBs and 4R-MYBs have been previously reported in potato [78]. As compared to MYB TF reported in plants like Arabidopsis, O. sativa, and Brassica rapa ssp. Pekinensis, the MYB TFs showed a greater frequency in the B. juncea genome, which might be accounted for the polyploidization in B. juncea’s genome [79–82]. However, our finding shows consistency with the hexaploidy wheat genome (719 MYB TFs) [83]. BjuMYBs were found on all 18 chromosomes of A and B sub-genomes depicting uniform distribution of genes on the chromosomes. Previous research in Solanaceae members, such as tomato [84] and potato [28], found a similar distribution of the MYBs. The isoelectric points and molecular weight perform an integral part in the regulation of the biochemical and molecular function [85]. So, we examined BjuMYB protein composition and their specific pIs, which showed a distinct variation in their range. It is most likely due to their different activities during various environmental conditions, leading to a significant variety of functions in MYB proteins [86]. A classic TF has a binding site in DNA, a regulatory domain for transcription, a site of oligomerization, and a region for nuclear localization [87]. Our subcellular localization prediction, showed nuclear localization in about 96.30% BjuMYBs. This pattern of nuclear localization of MYB TFs was found similarly in Capsicum species [86]. This prediction may indicate that most of the BjuMYB candidates may have an NLS (nuclear localization signal) to perform their function as TFs in the regulation of gene expression in the nucleus [87].

The evolutionary relationship of the BjuMYB proteins was investigated with AtMYB proteins. Phylogenetic trees revealed that BjuMYBs and AtMYBs formed distinctive groups, indicating that the two plant species had a preserved history of evolution. Furthermore, AtMYB does not exist in all BjuMYB sub-groups. For instance, the absence of AtMYB in the B31, B35, J11, J12, and J14 groups reflects that each species has developed adaptations to its specific habitat [88]. MYB proteins that are most closely linked may have a similar function. For instance, AtMYB12 and AtMYB111 are involved in the control of flavonoid biosynthesis [89, 90]. The above mentioned AtMYBs clustered with BjuAMYB12a, BjuBMYB12c, BjuAMYB111a, and BjuAMYB111b in the B15 Subgroup. Previous research has identified AtMYB93 as a unique inhibitor of the regulation of lateral root growth in Arabidopsis [91]. In the B1 subgroup, AtMYB93 clustered with BjuAMYB93a, BjuBMYB93b, BjuAMYB92b, and BjuAMYB53a, which shows these BjuMYBs might have similar functions in root growth. In Arabidopsis, AtMYB49 and AtMYB102 influence salt tolerance and defence against insects, respectively [92, 93]. As BjuAMYB49a and BjuAMYB102a clustered closely with AtMYB49 and AtMYB102 in the B3 subgroup, they might perform the same function under salt stress. Interestingly, AtMYBs and BjuMYBs grouped together may suggest that they respond to a common function similarly.

Furthermore, the gene structure and protein motif organisation evaluation provided strong evidence for a subgroup classification. According to earlier studies, the majority of the MYBs in the identical subgroup shared a comparable intron and exon structure, demonstrating the high level of interspecies conservation of MYB [94, 95]. The count and location of conserved motifs, as well as exon/intron architectures, differed between BjuMYBs. Usually, the N-terminus of MYB proteins frequently includes a DNA-binding region that is highly conserved [9, 94]. Most motif elements (for example, motifs 2, 1, and 3 in R2R3-BjuMYBs) were present at the N-terminus, while a small fraction (for example, motif 5 in R2R3-BjuMYBs) were located at the C-terminus. Similar motif distribution has been shown previously in Casuarina equisetifolia and Cucumis sativus [96, 97]. Also, this data of similar motif composition was observed in members closely clustered in phylogenetic, which might show existence of similar functions across the members of the same clade [96, 97]. Additionally, among R2R3-BjuMYB proteins, R2 and R3 repetitions were present in the R2R3 repeat domain. The R2 region typically showed that the three Trp amino acid residues are highly conserved, whereas the preliminary Trp amino acid residue in the R3 region varies. The substitution of first Trp residue with Phe in R3 region may alter the target gene or show reduced DNA binding capacity [8]. In fact, identical events have been reported for Medicago sativa [98].

The protein-protein interaction analysis suggested involvement of BjuMYBs in various plant growth and stress-induced responses. In this study, interaction between various BjuMYB proteins with MYB44 (BjuAMYB77f) suggested their role in resistance to abiotic stresses. MYB44 by suppressing the expression of protein phosphatases 2 C (pp 2 C), enhances resistance to abiotic stresses depending on ABA signalling [99]. MYB 73 and MYB 77 have previously been reported to directly bind with PYL8 and enhance the activity of the IAA19 auxin-responsive gene, which consequently promotes lateral root growth and response to salinity [100]. Interaction between MYB73 (BjuBMYB73f) and MYB 77 (BjuAMYB77d) suggests the potential role of BjuMYB proteins in salt stress and auxin signalling responses [100]. The interaction of BjuMYBs with various components of the multiprotein complex, such as SWI3A, SWI3B, SWI3C, and SWI3D, indicated their involvement in either promotion or inhibition of the binding of gene-specific transcription factors [101–103]. Further, interaction with various proteins such as CPC, TRY, ETC1, ETC2, and ETC3 suggested involvement of BjuMYBs in stomata formation, inhibition of trichome development and promotion of root hair formation [104–106].

Environmental conditions such as drought, salinity, cold, and heat represent a severe danger to Brassica crop yield. In the present study, level of transcript expression of BjuMYB TFs during drought-induced stress was investigated. AtMYB2 TF was identified based on its transcriptional function in response to dehydration, ABA treatments, and excessive salt conditions [107]. In previous studies, QsMYB1, discovered in oak plant species (Quercus suber L.), has been linked to drought conditions and transcriptional process of alternative splicing [108, 109]. Furthermore, OsMYB2 has also been predicted to be engaged in response to salt, drought, and cold stressors [110]. A previous study on M. esculenta reported upregulation in the transcript levels of MeMYB111 and MeMYB217 expression during drought-induced stress relative to the untreated plants [111]. Furthermore, the transcript levels of VcMYB102 and VcMYB8 were upregulated considerably under drought-induced stress in the leaves of Vaccinium corymbosum [73]. Based on available literature, MYB TFs perform an important role in overcoming drought-induced stress. When drought stress was applied to the plants, the expression levels of all nine BjuMYBs increased compared to control conditions (excluding BjuAMYB108b at 8 h). The transcript level of BjuAMYB108b at 8 h declined considerably, showing that BjuAMYB108b might be a late acting gene as compared with the early responsive gene members like BjuAMYB102a. Similar trends of expression of late acting previously have been followed by BnaMYB7, BnaMYB11, and BnaMYB26 in B. napus [112]. Further, certain genes such as BjuBMYB77h, BjuAMYB77c, and BjuBMYB47g were considerably elevated throughout the duration of drought stress, showing that they might be good drought-tolerant candidates. Previous studies in P. glaucum have shown that PgMYB2, PgMYB176, and PgMYB187 exhibits similar pattern of continuously increasing expression [113]. The expression pattern of BjuAMYB108b, BjuAMYB74a, and BjuBMYB74e demonstrated that they act under early and prolonged drought conditions. A similar pattern of expression of MYBs has previously been observed in Brassica napus and Pennisetum glaucum under drought stress [112, 113]. Recent studies have reported that overexpression of MYB TFs enhances drought stress tolerance in transgenic lines. The overexpression of IbMYB48, a sweet potato R2R3-MYB TF, shows drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis [114]. The overexpression of BnMYBL2-1, a R3 MYB TF in Brassica napus, shows drought tolerance in wheat [115]. Based on previous studies, functional validation through overexpression or knockout models of identified BjuMYB TFs in this study may provide ideal candidates for drought stress tolerance.

Differential gene expression has previously been associated with the presence of distinct cis-regulatory components in the sequences of gene promoters [116]. The promoter analysis of BjuBMYB77h and BjuAMYB102c revealed the existence of two cis-regulatory components, ACGTATERD1 and MYCATERD1 that are related to the preliminary dehydration response which might describe the enhanced upregulation of these MYB genes during the initial exposure to drought stress [117, 118]. Furthermore, the existence of desiccation-responsive cis-regulatory components, i.e., NTBBF1ARROLB and DOFCOREZM [119], in the promoter of BjuBMYB77h supports its elevated transcript level during drought-induced stress. Promoters of inducible proteins such as Wsi18 (water stress), Dip1 (dehydration), R1G1B (preliminary drought conditions), rd29A and rd29B (desiccation), etc. have been characterized and utilised to increase the tolerance of plants in numerous stressful circumstances [120, 121]. Further, promoter cloning and characterization to validate the involvement of cis- regulatory components and the regulatory effect in abiotic stresses can be carried out.

Another key process of RNA post-transcriptional regulation includes microRNAs (miRNAs), an entity of small, non-coding intrinsic RNAs that have antagonistic functions in the regulation of gene expression [122, 123]. Several investigations have revealed that miRNAs play a significant role in overcoming drought-induced stress by controlling the regulation of drought-related genes, the majority of which encode TFs [124, 125]. A study explored three unique members of the family miR159 (stu-miR159a, stu-miR159b,and stu-miR159c) in Solanum tuberosum, as well as the associated target genes GAMyb-like (StuGAMyb-like1, StuGAMyb-like2.1, and StuGAMyb-like2.2), which have been suggested to play a role in drought stress response [126]. The transcript expression level of MYB33 and MYB101 was raised in mutant plants of cbp80/abh1 through miR159 downregulation and this effect has been described as critical for enhancing drought tolerance in potato plants [127]. It was demonstrated that Bra-miR824 controls the germination of seed by negatively affecting its target AGL16 [128]. Furthermore, miR164 binds the MYB TF and controls its gene expression in response to water stress [129]. In our study, we predicted regulatory interaction of candidates BjuAMYBR75, BjuAMYB30b, BjuAMYB88d, and BjuBMYB77g with miRNAs, i.e., Bju-miR156_1, Bju-miR156_2, Bju-miR159-1, Bju-miR390_1, and Bju-miR172_2, respectively. The above-mentioned miRNAs have already been identified under heat, salinity, and drought-induced stress in B. juncea [68]. These miRNAs could have a big impact on modulating the expression of BjuMYBs under drought stress. These miRNA-TF interactions in B. juncea can be further investigated to better comprehend their potential role under abiotic stresses.

In order to explore the lncRNAs-miRNAs-MYB TFs regulatory network corresponding to drought stress in B. juncea, computational interaction and expression patterns were studied. The latest studies have demonstrated that regulatory associations among molecules of RNA, including those between miRNA and lncRNA, lncRNA and mRNA, and miRNA and mRNA, constitute a regulatory relationship called lncRNAs-miRNAs-mRNAs [130, 131]. Previous studies have exploited co-expressing lncRNA-TFs pairs, highlighting the role of MIKC-MADS and NAC families in regulating abiotic stress-related responses [70, 132, 133]. The classical example of target mimicry in Arabidopsis has been examined, in which lncRNAs act as eTMs and sequester miRNAs in order to prevent target mRNAs [40]. Previous studies in Vitis vinifera have shown that lncRNA (TR12392) was predicted to be an eTMs sequestering vvi-miR156h, which mainly cleaved TF ‘Squamosa Promoter Binding Protein’ (SBP) mRNA crucial for the development of inflorescence [134]. It has been observed that miRNA172 normally targets AP2-like (APETELA2-LIKE) TFs, consequently facilitating adult epidermal integrity or shoot development [135]. In our study, on the basis of computational analysis, we predicted that drought-responsive lncRNAs (TCONS_00084328 and TCONS_00051867) act as an eTMs of Bju-miRNAs (Bju-miR156_1 and Bju-miR172_2), respectively, which in turn target BjuMYB TFs. Based on RT-qPCR results, the expression pattern of regulatory networks I and II also confirmed the competing relationships between candidates RNAs. This trend of expression was also examined in Arabidopsis and Triticum aestivum L. with respect to heat and drought stress conditions, respectively [42, 136, 137]. The downregulated expression pattern of lncRNA and target in regulatory network I shows consistency with previous studies in wild plants, where in it was reported that overexpression of TCONS_00021861 acts as an eTM of miR528-3p and enhances drought tolerance in rice by preventing target mRNA [138]. We found that Bju-miR172_2 shows downregulation in regulatory network II as compared to their target genes. Our result in regulatory network II shows consistency with previous studies related to drought resistance of potato and Shanlan upland rice [139, 140]. These findings suggest that differences in types, candidates, and degrees of expression of genes may be species-dependent during drought stress. We hypothesise that overexpressing lncRNA acting as an eTM subsequently sponge miRNA might enhance the abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Altogether, it would be fascinating to further characterise and functionally validate these regulatory networks to uncover potential candidates for improving stress tolerance in plants.

Conclusion

The MYB TF family is an enormous family of genes in higher species of plants and essential for plant development processes. We performed an elaborate genome-wide identification and transcriptional evaluation of the MYB TF family in B. juncea under the influence of drought conditions. A total of 751 MYBs were discovered and categorised into four subgroups. According to phylogenetic analysis, most of the BjuMYB proteins clustered tightly with members of AtMYBs, suggesting their similarity in functional roles. The expression profiling of BjuMYBs revealed their role in drought-induced stress. Promoter analysis of BjuMYBs showed the existence of cis-regulatory elements responsive to different stress conditions, growth and development, depicting its involvement in various biological functions. An investigation of PPI revealed that BjuMYBs are involved in abiotic stress response. The predicted interactions of miRNAs and BjuMYBs in our study suggested their roles in plant growth and development, and stress response. Moreover, the regulatory interaction of lncRNA-miRNA-MYB TF corroborated its involvement in the regulation of drought tolerance through eTM based inhibition of miRNA targeting. Functional characterization and validation of these regulatory networks can help us in improving drought-response in Brassica plants.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Table S1. List of gene specific primers for RT-qPCR validation of drought responsive lncRNAs-Bju-miRNA-BjuMYBs

Supplementary Material 2: Supplementary Table S2. Detailed information about Classification, Nomenclature, and Chromosomal distribution of MYB TF family in B. juncea

Supplementary Material 3: Supplementary Table S3. Physico-chemical characterization and Subcellular localization of MYB TF family proteins

Supplementary Material 4: Supplementary Table S4. Detailed information for conserved motif sequences of different BjuMYB proteins groups. (a) 1R-BjuMYB; (b) R2R3-BjuMYB; (c) 3R-BjuMYB; (c) 4R-BjuMYB

Supplementary Material 5: Supplementary Table S5. Phylogenetic analysis and classification of different MYB groups into different subclades. (a) 1R-MYB; (b) R2R3-MYB; (c) 3R-MYB and 4R-MYB

Supplementary Material 6: Supplementary Table S6. Detailed information of the intron number in different groups of BjuMYBs

Supplementary Material 7: Supplementary Table S7. Detailed information of promoter analysis of differentially expressed BjuMYBs

Supplementary Material 8: Supplementary Figure S1. Schematic representation of the five conserved motifs of BjuMYB proteins. Differently coloured boxes represent different motifs, and the numbers inside the coloured boxes represent their motif number. The scale bar at the bottom represents the amino acid (aa) length of the protein. (a) R2R3-BjuMYB; (b) 1R-BjuMYB; (c) 3R-BjuMYB (i); and 4R-BjuMYB (ii)

Supplementary Material 9: Supplementary Figure S2. Gene structure analysis of the BjuMYBs. The exons, introns and upstream/ downstream regions are shown by blue hexagons, black lines, and red lines respectively, (a) R2R3-BjuMYB; (b) 1R-BjuMYB; (c) 3R-BjuMYB (i); 4R-BjuMYB (ii)

Supplementary Material 10: Supplementary Figure S3. Gene ontology analysis of BjuMYB. (A) Gene ontology classification into three major aspects. Distribution of prominent GO terms into their major categories i.e; (B) cellular component, (C) molecular function and (D) biological process

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Department of Biotechnology, Panjab University, Chandigarh, for research resources and BRAD for the accessibility of data. RB is thankful to the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) for awarding junior research fellowship. DV is thankful to the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) for providing fellowship as Research Associate.

Abbreviations

- °C

Degree Celsius

- aa

Amino acid

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- B. juncea

Brassica juncea

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- BLASTp

Protein Blast

- BRAD

Brassica database

- ncRNA

Non-coding RNA

- CDD

Conserved Domain Database

- cDNA

Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid

- eTMs

Endogenous Target Mimics

- FPKM

Fragments per Kilobase per million reads

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GSDS

Gene Structure Display Server

- hr

Hour

- kDa

Kilo Dalton

- lncRNA

Long noncoding RNA

- MEGA

Moleculer Evolutionary Genetics Analysis

- MEME

Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- MUSCLE

Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation

- mw

Moleculer weight

- MYB

Myeloblastosis

- NCBI

National Centre for Biotechnology Information

- pfam

Protein families database

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- pI

Isoelectric point

- PlantCARE

Plant cis-acting regulatory elements

- PLACE

Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements

- PlantTFDB

Plant Transcription Factor Database

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- RSEM

RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SMART

Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool

- SRA

Sequence Read Archive

- TF

Transcription factor

- TIPS-41

Tonoplastic Intrinsic Protein-41

- TRY

Triptychon

Author contributions

KS; formulated the hypothesis, planned the experiments, evaluated the results and finalized the manuscript. RB and DV; gathered and evaluated the data, carried out wetlab experiments and compiled the results.; RK; evaluated the results and finalized the manuscript; RB and RK; wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The authors express their gratitude to SERB India for funding under the EMEQ scheme.

Data availability

Data used in the study is already available in BRAD database and accession numbers have been mentioned in methodology.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All the authors have read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Latchman DS. Transcription factors: an overview. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:1305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boija A, Klein IA, Sabari BR, Dall’Agnese A, Coffey EL, Zamudio AV, et al. Transcription factors activate genes through the phase-separation capacity of their activation domains. Cell. 2018;175:1842–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amoutzias GD, Veron AS, Weiner IIIJ, Robinson-Rechavi M, Bornberg-Bauer E, Oliver SG, et al. One billion years of bZIP transcription factor evolution: conservation and change in dimerization and DNA-binding site specificity. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:827–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, Reuber L, Jiang C-Z, Keddie J, et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290:2105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klempnauer KH, Gonda TJ, Bishop JM. Nucleotide sequence of the retroviral leukemia gene v-myb and its cellular progenitor c-myb: the architecture of a transduced oncogene. Cell. 1982;31:453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paz-Ares J, Ghosal D, Wienand U, Peterson PA, Saedler H. The regulatory c1 locus of Zea mays encodes a protein with homology to myb proto‐oncogene products and with structural similarities to transcriptional activators. EMBO J. 1987;6:3553–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanei-Ishii C, Sarai A, Sawazaki T, Nakagoshi H, He DN, Ogata K, et al. The tryptophan cluster: a hypothetical structure of the DNA-binding domain of the myb protooncogene product. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19990–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogata K, Morikawa S, Nakamura H, Sekikawa A, Inoue T, Kanai H, et al. Solution structure of a specific DNA complex of the myb DNA-binding domain with cooperative recognition helices. Cell. 1994;79:639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubos C, Stracke R, Grotewold E, Weisshaar B, Martin C, Lepiniec L, et al. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:573–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipsick JS. One billion years of Myb. Oncogene. 1996;13:223–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudo M, Kidokoro S, Yoshida T, Mizoi J, Todaka D, Fernie AR, et al. Double overexpression of DREB and PIF transcription factors improves drought stress tolerance and cell elongation in transgenic plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15:458–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pennisi E. Getting to the root of drought responses. Science. 2008;320:173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao C, Li X, Li Y, Yang G, Liu W, Shao B, et al. Overexpression of a Malus baccata MYB transcription factor gene MbMYB4 increases cold and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao C, Li W, Liang X, Ren C, Liu W, Yang G, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of MbMYB108, a Malus baccata MYB transcription factor gene, with functions in tolerance to cold and drought stress in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Wei Y, Zhang L, Wang Y, Song P, Li X, et al. FvMYB44, a Strawberry R2RtranscriptionifactorFaimprovedproved salt and cold stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Agronomy. 2023;13:1051. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li W, Zhong J, Zhang L, Wang Y, Song P, Liu W, et al. Overexpression of a Fragaria vesca MYB transcription factor gene (FvMYB82) increases salt and cold tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:10538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen T, Li W, Hu X, Guo J, Liu A, Zhang B, et al. A cotton MYB transcription factor, GbMYB5, is positively involved in plant adaptive response to drought stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:917–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seo PJ, Xiang F, Qiao M, Park JY, Lee YN, Kim SG, et al. The MYB96 transcription factor mediates abscisic acid signaling during drought stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:275–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu N, Cheng S, Liu X, Du H, Dai M, Zhou DX, et al. The R2R3-type MYB gene OsMYB91 has a function in coordinating plant growth and salt stress tolerance in rice. Plant Sci. 2015;236:146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Q, Dai X, Xu Y, Guo J, Liu Y, Chen N, et al. Enhanced tolerance to chilling stress in OsMYB3R-2 transgenic rice is mediated by alteration in cell cycle and ectopic expression of stress genes. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:244–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu X, Liang W, Cui X, Chen M, Yin C, Luo Z, et al. Brassinosteroids promote development of rice pollen grains and seeds by triggering expression of Carbon Starved Anther, a MYB domain protein. Plant J. 2015;82:570–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong R, Lee C, McCarthy RL, Reeves CK, Jones EG, Ye ZH, et al. Transcriptional activation of secondary wall biosynthesis by rice and maize NAC and MYB transcription factors. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52:1856–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan J, Wang B, Zhong Y, Yao L, Cheng L, Wu T, et al. The soybean R2R3 MYB transcription factor GmMYB100 negatively regulates plant flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant Mol Biol. 2015;89:35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez-Diaz JR, Perez-Diaz J, Madrid-Espinoza J, Gonzalez-Villanueva E, Moreno Y, Ruiz-Lara S, et al. New member of the R2R3-MYB transcription factors family in grapevine suppresses the anthocyanin accumulation in the flowers of transgenic tobacco. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;90:63–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanhui C, Xiaoyuan Y, Kun H, Meihua L, Jigang L, Zhaofeng G, et al. The MYB transcription factor superfamily of Arabidopsis: expression analysis and phylogenetic comparison with the rice MYB family. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60:107–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Peng R, Tian Y, Han H, Xu J, Yao Q, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MYB transcription factor superfamily in S olanum lycopersicum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57:1657–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smita S, Katiyar A, Chinnusamy V, Pandey DM, Bansal KC. Transcriptional regulatory network analysis of MYB transcription factor family genes in rice. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Lin-Wang K, Liu Z, Allan AC, Qin S, Zhang J, et al. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiles of the StR2R3-MYB transcription factor superfamily in potato (Solanum tuberosum L). Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;148:817–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen D, Chen H, Dai G, Zhang H, Liu Y, Shen W et al. Genome-wide identification of R2R3-MYB gene family and association with anthocyanin biosynthesis in Brassica species. 2022;14;23(1):441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Gomez-Campo C. Morphology and morpho-taxonomy of the tribe Brassiceae. Brassica Crop wild Allies. 1980;:3–31.

- 31.Xu Z, Deng M. Cruciferae. Identification and control of common weeds: volume 2. Springer; 2017. pp. 437–74.

- 32.Nagaharu U, Nagaharu N. Genome analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Jpn J Bot. 1935;7:389–452. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krasensky J, Jonak C. Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:1593–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hao Y, Wang J, Hu C, Zhou Q, Mubeen HM, Hou X, et al. Regulation of BcMYB44 on anthocyanin synthesis and drought tolerance in non-heading Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris Ssp. Chinensis Makino) Horticulturae. 2022;8:351. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Lin K, Zhang S, Wu J, Fang Y, Wang Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of myeloblastosis-related genes in Brassica napus L. and positive modulation of osmotic tolerance by BnMRD107. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:678202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen B, Niu F, Liu WZ, Yang B, Zhang J, Ma J, et al. Identification, cloning and characterization of R2R3-MYB gene family in canola (Brassica napus L.) identify a novel member modulating ROS accumulation and hypersensitive-like cell death. DNA Res. 2016;23:101–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattick JS. The genetic signatures of noncoding RNAs. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajagopalan R, Vaucheret H, Trejo J, Bartel DP. A diverse and evolutionarily fluid set of microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3407–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madhawan A, Sharma A, Bhandawat A, Rahim MS, Kumar P, Mishra A, et al. Identification and characterization of long non-coding RNAs regulating resistant starch biosynthesis in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Genomics. 2020;112:3065–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franco-Zorrilla JM, Valli A, Todesco M, Mateos I, Puga MI, Rubio-Somoza I, et al. Target mimicry provides a new mechanism for regulation of microRNA activity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1033–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu HJ, Wang ZM, Wang M, Wang XJ. Widespread long noncoding RNAs as endogenous target mimics for microRNAs in plants. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:1875–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li N, Liu T, Guo F, Yang J, Shi Y, Wang S, et al. Identification of long non-coding RNA-microRNA-mRNA regulatory modules and their potential roles in drought stress response in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1011064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mishra DC, Majumdar SG, Kumar A, Bhati J, Chaturvedi KK, Kumar RR, et al. Regulatory Networks of lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs in response to heat stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): an Integrated Analysis. Int J Genomics. 2023;2023(1):1774764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghawana S, Paul A, Kumar H, Kumar A, Singh H, Bhardwaj PK, Rani A, Singh RS, Raizada J, Singh K, Kumar S, et al. An RNA isolation system for plant tissues rich in secondary metabolites. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng F, Liu S, Wu J, Fang L, Sun S, Liu B, et al. BRAD, the genetics and genomics database for Brassica plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verma D, Lakhanpal N, Singh K. Genome-wide identification and characterization of abiotic-stress responsive SOD (superoxide dismutase) gene family in Brassica juncea and B. rapa. BMC Genomics. 2019;20:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz HR, et al. The pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;36 suppl1:D281–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D257–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, et al. CDD: a conserved domain database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;39 suppl1:D225–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sigrist CJA, De Castro E, Cerutti L, Cuche BA, Hulo N, Bridge A, et al. New and continuing developments at PROSITE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41:D344–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13:1194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ostergaard L, King GJ. Standardized gene nomenclature for the Brassica Genus. Plant Methods. 2008;4:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar S, Nei M, Dudley J, Tamura K. MEGA: a biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9:299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. Proteom Protoc Handb. 2005;:571–607.

- 57.Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, et al. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35 suppl2:W585–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37 suppl2:W202–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu B, Jin J, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G, et al. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1296–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. Plant cis- acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:297–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lescot M, Dehais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:325–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhardwaj AR, Joshi G, Kukreja B, Malik V, Arora P, Pandey R, et al. Global insights into high temperature and drought stress regulated genes by RNA-Seq in economically important oilseed crop Brassica juncea. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chandna R, Augustine R, Bisht NC. Evaluation of candidate reference genes for gene expression normalization in Brassica juncea using real time quantitative RT-PCR. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dai X, Zhuang Z, Zhao PX. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release). Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bhardwaj AR, Joshi G, Pandey R, Kukreja B, Goel S, Jagannath A, et al. A genome-wide perspective of miRNAome in response to high temperature, salinity and drought stresses in Brassica juncea (Czern) L. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhatia G, Singh A, Verma D, Sharma S, Singh K. Genome-wide investigation of regulatory roles of lncRNAs in response to heat and drought stress in Brassica juncea (Indian mustard). Environ Exp Bot. 2020;171:103922. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nazarov PV, Reinsbach SE, Muller A, Nicot N, Philippidou D, Vallar L, et al. Interplay of microRNAs, transcription factors and target genes: linking dynamic expression changes to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:2817–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bonnet E, He Y, Billiau K, Van de Peer Y. TAPIR, a web server for the prediction of plant microRNA targets, including target mimics. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1566–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang A, Liang K, Yang S, Cao Y, Wang L, Zhang M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of MYB transcription factors of Vaccinium corymbosum and their positive responses to drought stress. BMC Genomics. 2021;22:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kranz H, Scholz K, Weisshaar B. c-MYB oncogene‐like genes encoding three MYB repeats occur in all major plant lineages. Plant J. 2000;21:231–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cao Y, Han Y, Li D, Lin Y, Cai Y. MYB transcription factors in Chinese pear (Pyrus Bretschneider i Rehd.): genome-wide identification, classification, and expression profiling during fruit development. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xie CG, Jin P, Xu J, Li S, Shi T, Wang R, et al. Genome-wide analysis of MYB transcription factor gene Superfamily reveals BjPHL2a involved in modulating the expression of BjCHI1 in Brassica juncea. Plants. 2023;12:1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qing J, Dawei W, Jun Z, Yulan X, Bingqi S, Fan Z, et al. Genome-wide characterization and expression analyses of the MYB superfamily genes during developmental stages in Chinese jujube. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li Y, Liang J, Zeng X, Guo H, Luo Y, Kear P, et al. Genome-wide analysis of MYB gene family in potato provides insights into tissue-specific regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Hortic Plant J. 2021;7:129–41. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katiyar A, Smita S, Lenka SK, Rajwanshi R, Chinnusamy V, Bansal KC. Genome-wide classification and expression analysis of MYB transcription factor families in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saha G, Park JI, Ahmed NU, Kayum MA, Kang KK, Nou IS, et al. Characterization and expression profiling of MYB transcription factors against stresses and during male organ development in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;104:200–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhu Y, Bao Y. Genome-wide mining of MYB transcription factors in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway of Gossypium hirsutum. Biochem Genet. 2021;59:678–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wei Z, Wang M, Chang S, Wu C, Liu P, Meng J, et al. Introgressing subgenome components from Brassica rapa and B. carinata to B. Juncea for broadening its genetic base and exploring intersubgenomic heterosis. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sukumaran S, Lethin J, Liu X, Pelc J, Zeng P, Hassan S, Aronsson H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of MYB transcription factors in the wheat genome and their roles in salt stress response. Cells. 2023;20(10):1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li Z, Peng R, Tian Y, Han H, Xu J, Yao Q, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MYB transcription factor superfamily in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57:1657–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mohanta TK, Khan A, Hashem A, Abd-Allah EF, Al-Harrasi A. The molecular mass and isoelectric point of plant proteomes. BMC Genomics. 2019;20:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arce-Rodriguez ML, Martinez O, Ochoa-Alejo N. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MYB transcription factor gene family in Chili pepper (Capsicum spp). Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu L, White MJ, MacRae TH. Transcription factors and their genes in higher plants: functional domains, evolution and regulation. Eur J Biochem. 1999;262:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nozawa M, Kawahara Y, Nei M. Genomic drift and copy number variation of sensory receptor genes in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:20421–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stracke R, Ishihara H, Huep G, Barsch A, Mehrtens F, Niehaus K, et al. Differential regulation of closely related R2R3-MYB transcription factors controls flavonol accumulation in different parts of the Arabidopsis thaliana seedling. Plant J. 2007;50:660–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stracke R, Jahns O, Keck M, Tohge T, Niehaus K, Fernie AR, et al. Analysis of PRODUCTION OF FLAVONOL GLYCOSIDES-dependent flavonol glycoside accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana plants reveals MYB11‐, MYB12‐and MYB111‐independent flavonol glycoside accumulation. New Phytol. 2010;188:985–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gibbs DJ, VoB U, Harding SA, Fannon J, Moody LA, Yamada E, et al. AtMYB93 is a novel negative regulator of lateral root development in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2014;203:1194–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang P, Wang R, Yang X, Ju Q, Li W, Lü S, et al. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor AtMYB49 modulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis by modulating the cuticle formation and antioxidant defence. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43:1925–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]