Abstract

The relation between use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and severity of COVID-19 has been the subject to debate since the outbreak of the pandemic. Despite speculations about the possible harmful or protective effects, the position currently most supported by the scientific community is that there is no association between use of NSAIDs and COVID-19 outcomes. With the aim of contributing to increase the body of evidence on this issue, we conducted a case–control study using real-world data to investigate the association between prior use of NSAIDs, by active ingredient and type (traditional NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors), and important COVID-19-related outcomes, including susceptibility, PCR + patient progression, and hospitalisation. Our findings suggest that, in general, the use of traditional NSAIDs is not associated with any adverse COVID-19 outcome. However, we observed a possible association between diclofenac and a higher risk of PCR + patient progression. Our results also suggest that selective COX-2 inhibitors might be related with a reduction in the risk of PCR + patient progression. These results suggest that, with the possible exception of diclofenac, the use of NSAIDs should not be advised against for relief of symptoms in patients with COVID-19. In addition, they support the importance of continue to investigate the treatment potential of selective COX-2 inhibitors in the management of COVID-19, something that could have significant implications for the treatment of this disease and other viral infections.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10787-024-01568-y.

Keywords: COVID-19, Hospitalisation, Susceptibility, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, Real world-data

Introduction

The influence of the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on COVID-19 has been the subject of debate and review since the outbreak of the pandemic (Yousefifard et al. 2020; Kow and Hasan 2021; Moore et al. 2021; Vaja et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2022; Zhao et al. 2022). Previous studies have yielded contradictory results, ranging from possible protective effects (Bruce et al. 2020; Chow et al. 2021; Perico et al. 2023) to harmful effects (Micallef et al. 2020; Fang et al. 2020; Jeong et al. 2021). Although there currently appears to be a consensus about the absence of relationship between use of NSAIDs and COVID-19 outcomes (Laughey et al. 2023), available evidence continues to show important limitations.

First, the most recent meta-analyses report the low quality of the studies included and the lack of precision of the results (attributable to the wide confidence intervals obtained) (Zhou et al. 2022), thus highlighting the need to conduct observational studies with large sample sizes.

Second, stress is laid on the need to address existing gaps, especially as regards possible differential effects of the different NSAIDs on COVID-19. Despite the fact that the previous studies suggest variations in the effects of NSAIDs by active ingredient (Gordon et al. 2020; Li et al. 2023), and this has also been observed in other drug groups (García-Álvarez et al. 2024; Visos-Varela et al. 2023a, b), studies which perform analysis by type of NSAIDs are limited, both in the number and diversity of the molecules studied.

Third, while most of the studies to date have focused their approach on severe COVID-19 outcomes such as mortality (Zhou et al. 2022; Zhao et al. 2022), at present, it would be important to explore the effect of NSAIDs on less severe outcomes (Kun et al. 2023), such as susceptibility, disease progression in infected patients, and hospitalisation. These aspects would not only serve to generate evidence on the relationship between NSAIDs and COVID-19, but could also offer valuable perspectives for clinical management and public health.

In this context, we conducted a population study with real-world case–control data to study the association, by active ingredient, between previous use of NSAIDs (including traditional NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors) and susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, PCR + patient progression, and hospitalisation due to COVID-19.

Methods

Population and settings

A case-population study was undertaken in Galicia, north-west Spain, in which data on drug exposure as well as clinical and demographic variables were extracted from primary health care, hospital, and administrative registries. The case-population study design is an epidemiological approach commonly used for pharmacovigilance purposes, in which the study population encompasses the whole population of a given territory (Théophile et al. 2011).

Galicia has a population of 2,694,245 and a public health system (Servizo Galego de Saúde/SERGAS) which provides universal healthcare access at low or no cost.

The study population comprised the entire adult population (age > 18 years) who were residents of Galicia and registered in SERGAS. For study purposes, we considered data recorded from 1 March to 31 December 2020.

Data sources

Demographic and clinical data required for the study were extracted from the Complex Data-Analysis Systems (Sistemas de Información y Análisis Complejos/SIAC) of SERGAS by an independent information technology services company that is independent of the research team and unaware of the study objectives (Visos-Varela et al. 2023a). SIAC is a data warehouse that stores information for the management of different health services, including health card information, administration and dispensing of electronic prescriptions, as well as data relating to hospital pharmacies, hospitalisation information systems, death registries, and clinical laboratory analysis. Study covariates included demographic and socioeconomic variables, hospitalisation data and COVID-19 clinical variables (where applicable), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/COPD, obesity, ischaemic heart disease, stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic renal failure, cancer, asthma, and smoking status), and exposure to different classes of medications. As a proxy for the degree of chronicity of patients, we considered the number of different medications prescribed and dispensed for chronic conditions in the 6 months prior to the index date (Huber et al. 2013).

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Galician clinical research ethics committee (Reference 2020–349) and authorised by the Spanish Agency for Medication and Healthcare Products (Reference AFG-IBU-2020–11). It was also registered in the European Electronic Register of Post-Authorisation Studies (EUPAS44587).

Definitions

Exposure

In our settings, exposure was defined as use of any NSAID in the previous month. Exposure was ascertained when an individual had a prescription lasting until the last month before the index date. Drug exposure in the 10 days preceding outcome occurrence was excluded from the analysis, to prevent any possible bias of inverse causality.

Outcomes

The study outcomes were: (1) susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2; (2) PCR + patient progression; and (3) hospitalisation due to COVID-19.

Cases and controls

Specific definitions of cases and controls were applied for each of the study outcomes (Table S1, see Supplementary data).

Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 a case was defined as any patient having a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2, regardless of whether or not he/she had been hospitalised between March 2020 and 31 December 2020. Controls consisted of individuals without any history of positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test results or any other COVID-19-positive diagnosis.

PCR + patient progression a case was defined as any individual with a positive PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 who had been admitted to any SERGAS hospital between March 2020 and 31 December 2020, and with: (1) the reason for admission being COVID-19; or (2) symptomatology compatible with COVID-19 (respiratory tract infection, viral pneumonia, shortness of breath, cough, fever, etc.). To avoid inclusion of hospitalisations that were not due to COVID-19, a 10-day time window was established between the SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR test and the hospitalisation date. The control group comprised COVID-19 patients who did not require hospitalisation. This outcome variable measures the likelihood of progressing to severe stages of COVID-19 that require hospitalisation among infected patients (Falcone et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2022; Campbell et al. 2022b).

Hospitalisation due to COVID-19 a case was defined as any hospitalised individual diagnosed with COVID-19 (i.e., the same cases as in the sub-study of PCR patients' progression). Controls consisted of individuals without any history of positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test results or any other COVID-19 positive diagnosis, i.e., the same control group as that used for the susceptibility sub-study. In this analysis for each case, 20 controls were matched by age, sex, and the geographic region to which the primary healthcare centre belonged. This approach allows us to jointly measure the effect of NSAIDs exposure on both susceptibility to the virus and PCR + patients' progression (measured through an objective variable such as hospitalisation) (de Abajo et al. 2020; Perry et al. 2021; Fenton et al. 2021; Spila Alegiani et al. 2021). Therefore, the results of this case–control sub-study are independent of the availability of PCR tests, which is particularly important, since our study was conducted in 2020, a period when the Spanish healthcare system lacked the capacity to perform diagnostic tests on all individuals presenting COVID-19 signs and symptoms or who had been close contacts of COVID + cases.

Statistical analysis

Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated by generalised linear mixed models (GLMM) for dependent qualitative dichotomous variables (Brown and Prescott 2015). The use of GLMM was chosen due to the data structure and their advantages over conditional regression (Pinheiro and Bates 2000; Stroup 2012; Brown and Prescott 2015),

To construct the models, the following four levels were considered: (i) patient; (ii) case–control stratum (case and matched control); (iii) health centre; and (iv) pandemic wave. We used random effects to assess the effect of the pandemic wave, and nested random effects for patients, case–control strata, and health centre. Adjustments were made for potential confounding variables, including age, sex, occupation (healthcare professional), health area, COVID-19 wave, and comorbidities. The models were estimated using the glmer function of the lme4 R package (R Software version 4.1.0).

Results

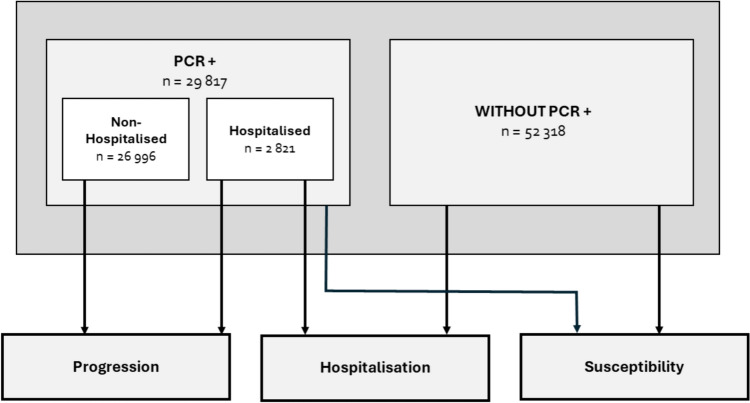

A total of 82,135 Galician adults were included in the analysis. Three outcomes (susceptibility, progression, and hospitalisation) were defined in the study. The flow of cases and controls in the analysis of each outcome is shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 summarises the general demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

Fig. 1.

Population-based multiple case–control design

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population for the following outcomes: susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2; PCR + patient progression; and hospitalisation due to COVID-19

| Characteristic | Susceptibility to SARS CoV-2 | PCR + patient progression | Hospitalisation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (N = 29,817) | Controls (N = 52,318) | Cases (N = 2821) | Controls (N = 26,996) | Cases (N = 2821) | Controls (N = 52,318) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 12,674 (42.5) | 26,998 (51.6) | 1457 (51.6) | 11,217 (41.6) | 1457 (51.6) | 26,998 (51.6) |

| Female | 17,143 (57.5) | 25,320 (48.4) | 1364 (48.4) | 15,779 (58.4) | 1364 (48.4) | 25,320 (48.4) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 49 (34—67) | 73 (60—84) | 74 (60—85) | 47 (33—63) | 74 (60—85) | 73 (60—84) |

| Health-related profession | 1316 (4.4) | 1203 (2.3) | 78 (2.8) | 1238 (4.6) | 78 (2.8) | 1203 (2.3) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 7847 (26.3) | 26,292 (50.3) | 1639 (58.2) | 6208 (23.0) | 1639 (58.2) | 26,292 (50.3) |

| Diabetes | 3301 (11.1) | 10,233 (19.6) | 782 (27.8) | 2519 (9.3) | 782 (27.8) | 10,233 (19.6) |

| COPD | 1128 (3.8) | 4305 (8.2) | 369 (13.1) | 759 (2.8) | 369 (13.1) | 4305 (8.2) |

| Obesity | 4790 (16.1) | 10,104 (19.3) | 830 (29.5) | 3960 (14.7) | 830 (29.5) | 10,104 (19.3) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 1191 (4.0) | 4479 (8.6) | 326 (11.6) | 865 (3.2) | 326 (11.6) | 4479 (8.6) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1144 (3.8) | 3631 (6.9) | 277 (9.8) | 867 (3.2) | 277 (9.8) | 3631 (6.9) |

| Heart failure | 1108 (3.7) | 3780 (7.2) | 430 (15.3) | 678 (2.5) | 430 (15.3) | 3780 (7.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1501 (5.0) | 5405 (10.3) | 425 (15.1) | 1076 (4.0) | 425 (15.1) | 5405 (10.3) |

| Chronic renal failure | 1115 (3.7) | 4059 (7.8) | 403 (14.3) | 712 (2.6) | 403 (14.3) | 4059 (7.8) |

| Cancer | 2230 (7.5) | 7277 (13.9) | 475 (16.9) | 1755 (6.5) | 475 (16.9) | 7277 (13.9) |

| Asthma | 2437 (8.2) | 3070 (5.9) | 267 (9.5) | 2170 (8.0) | 267 (9.5) | 3070 (5.9) |

| Current smoking | 4845 (16.2) | 7842 (15.0) | 737 (26.1) | 4108 (15.2) | 737 (26.1) | 7842 (15.0) |

Unless otherwise stated, data are n (%)

Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2: Cases encompassed patients with a positive PCR test for SARS-CoV-2, regardless of hospitalisation status. Controls did not have any history of positive SARS-CoV-2 test results

PCR + patient progression: Cases included all individuals hospitalised due to COVID-19. Controls were COVID-19 patients who did not require hospitalisation

Hospitalisation: Cases encompassed all individuals hospitalised due to COVID-19. Controls were subjects who did not present with a PCR + test, matched with cases

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range

Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2

29,817 individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 (susceptible cases) and 52,318 controls were included in the analysis.

The most commonly used NSAIDs in the month immediately preceding SARS-CoV-2 infection were ibuprofen and dexketoprofen. No association was observed between susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 and exposure in the previous month to any of the traditional NSAIDs or selective COX-2 inhibitors studied (neither by group nor by active ingredient) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, PCR + patient progression and hospitalisation due to COVID-19 from past month’s exposure to NSAIDs (traditional NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors)

| Drug exposure | Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 | PCR + patient progression | Hospitalisation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, N (%) | Controls, N (%) | aOR (95% CI)* | Cases, N (%) | Controls, N (%) | aOR (95% CI)* | Cases, N (%) | Controls, N (%) | aOR (95% CI)* | |||

| Traditional NSAIDs | 2142 (7.2) | 3662 (7.0) | 1.05 (0.99–1.13) | 256 (9.1) | 1886 (7.0) | 1.10 (0.94–1.29) | 256 (9.1) | 3662 (7.0) | 1.13 (0.98–1.30) | ||

| Dexketoprofen | 592 (2.0) | 828 (1.6) | 1.00 (0.88–1.13) | 54 (1.9) | 538 (2.0) | 1.19 (0.87–1.63) | 54 (1.9) | 828 (1.6) | 1.10 (0.83–1.46) | ||

| Ibuprofen | 683 (2.3) | 940 (1.8) | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 56 (2.0) | 627 (2.3) | 0.95 (0.70–1.28) | 56 (2.0) | 940 (1.8) | 1.06 (0.80–1.40) | ||

| Naproxen | 284 (1.0) | 409 (0.8) | 1.13 (0.95–1.35) | 29 (1.0) | 255 (0.9) | 1.02 (0.66–1.57) | 29 (1.0) | 409 (0.8) | 1.18 (0.80–1.74) | ||

| Diclofenac | 164 (0.6) | 331 (0.6) | 0.96 (0.78–1.19) | 26 (0.9) | 138 (0.5) | 1.80 (1.12–2.88) | 26 (0.9) | 331 (0.6) | 1.36 (0.91–2.05) | ||

| Meloxicam | 40 (0.1) | 90 (0.2) | 1.20 (0.80–1.82) | 7 (0.2) | 33 (0.1) | 1.23 (0.48–3.13) | 7 (0.2) | 90 (0.2) | 1.41 (0.65–3.08) | ||

| Aceclofenac | 41 (0.1) | 78 (0.1) | 1.16 (0.75–1.80) | 6 (0.2) | 35 (0.1) | 1.31 (0.49–3.50) | 6 (0.2) | 78 (0.1) | 1.45 (0.62–3.35) | ||

| Lornoxicam | 32 (0.1) | 53 (0.1) | 1.44 (0.89–2.33) | 4 (0.1) | 28 (0.1) | 0.86 (0.27–2.69) | 4 (0.1) | 53 (0.1) | 1.40 (0.50–3.91) | ||

| Metamizole | 454 (1.5) | 1158 (2.2) | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) | 84 (3.0) | 370 (1.4) | 0.88 (0.66–1.18) | 84 (3.0) | 1158 (2.2) | 0.92 (0.73–1.16) | ||

| Selective COX-2 inhibitors | 276 (0.9) | 710 (1.4) | 1.05 (0.90–1.23) | 34 (1.2) | 242 (0.9) | 0.70 (0.47–1.04) | 34 (1.2) | 710 (1.4) | 0.87 (0.61–1.24) | ||

| Etoricoxib | 164 (0.6) | 434 (0.8) | 0.95 (0.78–1.16) | 20 (0.7) | 144 (0.5) | 0.71 (0.42–1.19) | 20 (0.7) | 434 (0.8) | 0.82 (0.52–1.29) | ||

| Celecoxib | 112 (0.4) | 277 (0.5) | 1.24 (0.97–1.58) | 14 (0.5) | 98 (0.4) | 0.70 (0.38–1.29) | 14 (0.5) | 277 (0.5) | 0.97 (0.56–1.67) | ||

CI confidence interval, aOR adjusted odds ratio

*OR was adjusted for sex, age, health professional status, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, COPD, obesity, ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular accident, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic renal failure, cancer, asthma, and current smoker), current use of other pharmacological treatment, and number of treatments for chronic diseases. Additionally, the primary-care service of reference and the pandemic wave were included as random effects

The overall number of subjects exposed to traditional NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors may be lower than the sum of those exposed to the active ingredients separately, due to the fact that some subjects were exposed to more than one active ingredient across the study period

PCR + patient progression

While the odds of progression of PCR + patients were not associated with use of traditional NSAIDs in general, the use of diclofenac in the last month was associated with increased odds of PCR + patient progression (aOR = 1.80; 95% CI 1.12–2.88). Furthermore, use of selective COX-2 inhibitors in the month prior to infection suggested a possible decrease in the odds of PCR + patient progression close to statistical significance (aOR = 0.70; 95% CI 0.47–1.04, p < 0.08) (Table 2).

Hospitalisation for COVID-19

This analysis included 52,318 controls and 2821 cases hospitalised due to COVID-19 across the study period. Around half the cases (51.6%) and controls (51.6%) were males (Table 1).

No association was observed between exposure in the past month to traditional NSAIDs or selective COX-2 inhibitors (either by group or by active ingredient) and COVID-19 hospitalisation (Table 2).

Discussion

The results of this large-scale population-based case–control study with real-world data suggest that in general, there is no association between previous use of traditional NSAIDs and the appearance of COVID-19 outcomes. Most of the NSAIDs evaluated are safe vis-à-vis the disease. It was, however, observed that diclofenac could be associated with a higher risk of progression to severe disease stages. Furthermore, according to our results, selective COX-2 inhibitors could reduce the risk of progression to severe diseases stages, though this association does not reach statistical significance.

The design and size of our study sample enabled us to analyse the effect of NSAIDs by active ingredient and type (traditional NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors) on a number of COVID-19 outcomes, such as susceptibility, PCR + patient progression, and hospitalisation.

With respect to traditional NSAIDs (dexketoprofen, ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, aceclofenac, lornoxicam, and metamizole), no association was found between their use in the last month and the outcomes analysed, despite the high statistical power of our study (n = 82 135). In contrast, diclofenac showed a significant increase in risk of progression to severe stages of the disease (aOR = 1.80; 95% CI 1.12–2.88). Although we cannot rule out that this may be a chance finding, our result is nonetheless in line with a previous study which identified a higher risk of cardiovascular and coronary events in COVID-19 patients who used diclofenac (Campbell et al. 2022a).

The outcomes of selective COX-2 inhibitors are more noteworthy, since they suggest a possible decrease in risk of disease progression, close to statistical significance (aOR = 0.70; 95% CI = 0.47–1.04, p < 0.08). These observations are in line with the previous studies, which suggest that selective COX-2 inhibitors could be useful in SARS-CoV-2 infection for relieving COVID-19-related symptomatology (Ong et al. 2020; Hong et al. 2020; Ghaznavi et al. 2022; Consolaro et al. 2022).

The biological plausibility of this possible association is based on a number of previously proposed mechanisms. First, COX-2 inhibition could modulate the excessive inflammatory response observed in severe cases of COVID-19, decreasing the levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, G-CSF and IL-6, and preventing progression to more severe disease stages (Baghaki et al. 2020). Furthermore, it has been shown that COX-2 inhibitors possess antifibrotic effects (Fabbrini et al. 2009; Tseng et al. 2019), which could be beneficial for preventing or reducing pulmonary fibrosis associated with COVID-19. Similarly, it has been suggested that these drugs could modulate antiviral immunity without compromising the general immune response, unlike non-selective NSAIDs, which on inhibiting both COX-1 and COX-2 could weaken the antiviral response (Baghaki et al. 2020). This capacity of selective COX-2 inhibitors to maintain an appropriate balance between immune response and excessive inflammation could be fundamental in the management of COVID-19 patients.

The biological mechanisms suggested, along with the similarity in the odds ratios observed in our study between the selective COX-2 inhibitors most prescribed in Spain (celecoxib and etoricoxib), support the idea that the reduction in the risk of disease progression could be a class effect. That said, however, more studies are needed, preferably randomised clinical trials (RCT) such as those that are under way (NCT05077332, NCT04488081), to confirm these findings and ascertain the efficacy and safety of selective COX-2 inhibitors in patients with COVID-19.

It would be relevant to continue studying the antiviral potential of selective COX-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib and etoricoxib. Previous studies on preclinical models have stressed the antiviral activity of these compounds against different viruses, such as herpes simplex, hepatitis C, dengue, or zika. Furthermore, they have been identified as one of the few treatments available, with RCT-based evidence which shows that they reduce mortality in severe influenza. The development of this line of research could make for a better understanding of the antiviral activity of selective COX-2 inhibitors and their usefulness in different viral infections.

Clinical and public health implications

If the results of ongoing RCT of selective COX-2 inhibitors confirm the trend observed in our study toward a reduction in risk of disease progression, the use of these drugs in the management of COVID-19 could have a dual purpose. Apart from relief of symptoms, such as fever, pain, and inflammation, they could influence disease progression, reducing the risk of severe complications and the need for hospitalisation in infected patients.

It is important to stress that the results relating to disease progression are currently of great relevance. If previous use of selective COX-2 inhibitors is associated with a decrease in disease progression, it is plausible that their use during the symptomatic stage could likewise influence this. In turn, this potential effect could also decrease the risk of hospitalisation, an outcome of great public health interest.

With respect to the impact of the use of NSAIDs (including traditional NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors) during the symptomatic stage, we decided not to perform these analyses due to a possible bias of inverse causality. This phenomenon refers to the possibility of disease severity influencing the use of NSAIDs, rather than the use of NSAIDs influencing disease severity. This bias cannot be adequately controlled for by the design of our study. It is, however, important to consider that patients could continue taking these drugs during the symptomatic stage due to previous or recent prescriptions in the days preceding detection of the virus. Our results suggest that use of NSAIDs neither negatively affects nor protects patients during this stage, and that the use of selective COX-2 inhibitors could be associated with a reduction in risk.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of our study are its use of population data and large sample size, which made it possible to adjust the results for a wide range of clinical and socio-demographic variables. This enabled us to accurately estimate the possible association between use in the last month of different NSAIDs and susceptibility to and prognosis of COVID-19 (progression to severe stages and hospitalisation). Furthermore, the measure of exposure to drugs was based on dispensing data, something that reduces the risk of misclassification of the variable of exposure, as compared to many other studies which use prescription-based data-sources. It should be stressed that here in Spain, most NSAIDs cannot be dispensed without a medical prescription, so that dispensing provides a good estimate of their use.

Our study also has some limitations. First, the fact of its being an observational study with secondary databases means that there is the possibility of residual confounding due to unmeasured or misclassified factors, such as the degree of severity of the main comorbidities associated with greater COVID-19 severity. Moreover, the lack of matching in the susceptibility and progression substudies could be considered a further limitation, though the validity of the study is not really affected, since the absence of matching only decreases efficacy and does not increase the risk of biases (Rothman et al. 2008; Rose and Laan 2009). It should also be borne in mind that the data available for this study pertain to 2020, when the predominant SARS-CoV-2 variants in this country were derived from clade 19B (Díez-Fuertes et al. 2021), though we have no reason to believe that the effect of the drugs studied against COVID-19 could be influenced by the presence of the dominant variant. Finally, it should be noted that our study lacks a dose–response analysis of exposure to the drug and the trend in the outcomes, which limits a complete understanding of the relationship between the dose of the drugs and their effects on development of the disease.

Conclusion

The results of this real-world data study with a large-scale sample suggest that traditional NSAIDs, with the possible exception of diclofenac, should not be advised against for relief of symptoms in COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, though statistical significance was not reached, selective COX-2 inhibitors would appear to be associated with slower progression to severe stages of the disease. The similarity in the odds ratios between celecoxib and etoricoxib suggests the possible existence of a class effect of selective COX-2 inhibitors.

In view of these findings, it would be important to continue investigating the antiviral capacity of selective COX-2 inhibitors. This line of research could afford an opportunity to better understand their potential in the treatment of viral infections, with significant implications in the management of COVID-19 and other viral diseases.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the SERGAS General Directorate of Health Care of the Galician Health Service for furnishing the data necessary to conduct this study, DXC Technology for its work in extracting the study data and Michael Benedict for reviewing and revising the English

Author contributions

Narmeen Mallah: writing original draft preparation. Irene Visos-Varela: writing original draft preparation. Bahi Takkouche: methodology; writing—review and editing. Rosendo Bugarín-González: methodology; writing—review and editing. María Piñeiro-Lamas: formal analysis. Teresa Herdeiro: methodology; writing—review and editing. Maruxa Zapata-Cachafeiro: conceptualization; methodology; writing—review and editing. Almudena Rodríguez-Fernández: conceptualization; methodology; writing—review and editing. Angel Salgado-Barreira: conceptualization; methodology; writing—review and editing. Adolfo Figueiras: conceptualization; methodology; funding acquisition; writing—review and editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Carlos III Institute of Health via the “COV20/00470” project (co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund, “A way to make Europe”).

Data availability

The data sets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to Galician Public Health System restrictions.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Galician Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Comité de Ética de Investigación de Galicia, reference 2020/349), certified by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (Agencia Española del Medicamento y Productos Sanitarios), and was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the prevailing legislation governing biomedical research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Irene Visos-Varela, Email: irene.visos.varela@usc.es.

COVIDrug Group:

Narmeen Mallah, Irene Visos-Varela, Rosendo Bugarín-González, Maruxa Zapata-Cachafeiro, Angel Salgado-Barreira, Adolfo Figueiras, Eduardo Carracedo-Martínez, Rosa M. García-Álvarez, Francisco J. González-Barcala, Teresa M Herdeiro, Martina Lema-Oreiro, Samuel Pintos-Rodríguez, Maria Piñeiro-Lamas, Manuel Portela-Romero, Angela Prieto-Campo, Almudena Rodriguez-Fernández, Marc Saez, and Margarita Taracido-Trunk

References

- Baghaki S, Yalcin CE, Baghaki HS et al (2020) COX2 inhibition in the treatment of COVID-19: Review of literature to propose repositioning of celecoxib for randomized controlled studies. Int J Infect Dis 101:29–32. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H, Prescott R (2015) Applied mixed models in medicine. Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Bruce E, Barlow-Pay F, Short R et al (2020) Prior routine use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and important outcomes in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. J Clin Med 9:2586. 10.3390/jcm9082586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell HM, Murata AE, Conner TA, Fotieo G (2022a) Chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen and relationship with mortality among United States Veterans after testing positive for COVID-19. PLoS ONE 17:e0267462. 10.1371/journal.pone.0267462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JI, Dubois MM, Savage TJ et al (2022b) Comorbidities Associated with Hospitalization and Progression Among Adolescents with Symptomatic Coronavirus Disease 2019. J Pediatr 245:102-110.e2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow JH, Khanna AK, Kethireddy S et al (2021) Aspirin use is associated with decreased mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission, and in-hospital mortality in hospitalized patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Anesth Analg 132:930–941. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolaro E, Suter F, Rubis N et al (2022) A home-treatment algorithm based on anti-inflammatory drugs to prevent hospitalization of patients with early COVID-19: a matched-cohort study (COVER 2). Front Med 9:785785. 10.3389/fmed.2022.785785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Abajo FJ, Rodríguez-Martín S, Lerma V et al (2020) Use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital: a case-population study. The Lancet 395:1705–1714. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31030-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Fuertes F, Iglesias-Caballero M, García-Pérez J et al (2021) A founder effect led early SARS-CoV-2 transmission in Spain. J Virol 95:e01583-e1620. 10.1128/JVI.01583-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrini P, Schilte MN, Zareie M et al (2009) Celecoxib treatment reduces peritoneal fibrosis and angiogenesis and prevents ultrafiltration failure in experimental peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24:3669–3676. 10.1093/ndt/gfp384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone M, Tiseo G, Valoriani B et al (2021) Efficacy of bamlanivimab/etesevimab and casirivimab/imdevimab in preventing progression to severe COVID-19 and role of variants of concern. Infect Dis Ther 10:2479–2488. 10.1007/s40121-021-00525-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M (2020) Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 8:e21. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton L, Gribben C, Caldwell D et al (2021) Risk of hospital admission with covid-19 among teachers compared with healthcare workers and other adults of working age in Scotland, March 2020 to July 2021: population based case–control study. BMJ 374:n2060. 10.1136/bmj.n2060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Álvarez RM, Zapata-Cachafeiro M, Visos-Varela I et al (2024) Impact of prior antihypertensive treatment on COVID-19 outcomes, by active ingredient. Inflammopharmacology 32:1805–1815. 10.1007/s10787-024-01475-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaznavi H, Mohammadghasemipour Z, Shirvaliloo M et al (2022) Short-term celecoxib (celebrex) adjuvant therapy: a clinical trial study on COVID-19 patients. Inflammopharmacology 30:1645–1657. 10.1007/s10787-022-01029-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DE, Hiatt J, Bouhaddou M et al (2020) Comparative host-coronavirus protein interaction networks reveal pan-viral disease mechanisms. Science 370:eabe9403. 10.1126/science.abe9403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E et al (2022) Effect of sotrovimab on hospitalization or death among high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 327:1236–1246. 10.1001/jama.2022.2832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W, Chen Y, You K et al (2020) Celebrex adjuvant therapy on coronavirus disease 2019: an experimental study. Front Pharmacol. 10.3389/fphar.2020.561674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber CA, Szucs TD, Rapold R, Reich O (2013) Identifying patients with chronic conditions using pharmacy data in Switzerland: an updated mapping approach to the classification of medications. BMC Public Health 13:1030. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong HE, Lee H, Shin HJ et al (2021) Association between nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use and adverse clinical outcomes among adults hospitalized with coronavirus 2019 in South Korea: a nationwide study. Clin Infect Dis off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 73:e4179–e4188. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kow CS, Hasan SS (2021) The risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19 with pre-diagnosis use of NSAIDs: a meta-analysis. Inflammopharmacology 29:641–644. 10.1007/s10787-021-00810-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kun Á, Hubai AG, Král A et al (2023) Do pathogens always evolve to be less virulent? The virulence–transmission trade-off in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Biol Futura. 10.1007/s42977-023-00159-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughey W, Lodhi I, Pennick G et al (2023) Ibuprofen, other NSAIDs and COVID-19: a narrative review. Inflammopharmacology 31:2147–2159. 10.1007/s10787-023-01309-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Hilgenfeld R, Whitley R, De Clercq E (2023) Therapeutic strategies for COVID-19: progress and lessons learned. Nat Rev Drug Discov 22:449–475. 10.1038/s41573-023-00672-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micallef J, Soeiro T, Jonville-Béra A-P (2020) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pharmacology, and COVID-19 infection. Therapie 75:355–362. 10.1016/j.therap.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore N, Bosco-Levy P, Thurin N et al (2021) NSAIDs and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf 44:929–938. 10.1007/s40264-021-01089-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SWX, Tan WYT, Chan Y et al (2020) Safety and potential efficacy of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Transl Immunol 9:e1159. 10.1002/cti2.1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perico N, Cortinovis M, Suter F, Remuzzi G (2023) Home as the new frontier for the treatment of COVID-19: the case for anti-inflammatory agents. Lancet Infect Dis 23:e22–e33. 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00433-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RJ, Smith CJ, Roffe C et al (2021) Characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 associated stroke: a UK multicentre case–control study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 92:242–248. 10.1136/jnnp-2020-324927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D (2000) Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- Rose S, van der Laan MJ (2009) Why match? Investigating matched case-control study designs with causal effect estimation. Int J Biostat. 10.2202/1557-4679.1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL (2008) Case–control studies. In: Melnick EL, Everitt BS (eds) Encyclopedia of quantitative risk analysis and assessment. Wiley, Hoboken

- Spila Alegiani S, Crisafulli S, Giorgi Rossi P et al (2021) Risk of coronavirus disease 2019 hospitalization and mortality in rheumatic patients treated with hydroxychloroquine or other conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in Italy. Rheumatol Oxf Engl 60:SI5–SI36. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup WW (2012) Generalized linear mixed models: modern concepts, methods and applications. CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- Théophile H, Laporte J-R, Moore N et al (2011) The case-population study design: an analysis of its application in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf 34:861–868. 10.2165/11592140-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng H-C, Lin C-C, Hsiao L-D, Yang C-M (2019) Lysophosphatidylcholine-induced mitochondrial fission contributes to collagen production in human cardiac fibroblasts[S]. J Lipid Res 60:1573–1589. 10.1194/jlr.RA119000141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaja R, Chan JSK, Ferreira P et al (2021) The COVID-19 ibuprofen controversy: a systematic review of NSAIDs in adult acute lower respiratory tract infections. Br J Clin Pharmacol 87:776–784. 10.1111/bcp.14514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visos-Varela I, Zapata-Cachafeiro M, Piñeiro-Lamas M et al (2023a) Repurposing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for severity of COVID-19: a population-based study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 71:96–108. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2023.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visos-Varela I, Zapata-Cachafeiro M, Pintos-Rodríguez S et al (2023b) Outpatient atorvastatin use and severe COVID-19 outcomes: A population-based study. J Med Virol 95:e28971. 10.1002/jmv.28971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefifard M, Zali A, Zarghi A et al (2020) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in management of COVID-19; A systematic review on current evidence. Int J Clin Pract 74:e13557. 10.1111/ijcp.13557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Huang S, Huang S et al (2022) Prevalence of NSAID use among people with COVID-19 and the association with COVID-19-related outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 10.1111/bcp.15512.10.1111/bcp.15512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Zhao S, Gan L et al (2022) Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and adverse outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 46:101373. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to Galician Public Health System restrictions.