Abstract

Objective

To compare the performance of [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 in PET/CT evaluation for liver cancer lesions, with a further exploration of the associations between PET semiquantitative data and immunohistochemical markers to liver cancer.

Methods

Patients with suspected malignant liver lesions (MLL) underwent [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 PET/CT scanning. Liver lesions were visually classified as positive or negative based on their uptake level exceeding that of adjacent normal liver tissue. SUVmax and tumor-to-background ratio (TBR) were recorded for semi-quantitative analysis. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of each tracer were determined using pathological findings as the gold standard. Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis provided the molecular characteristics of all MLLs. Comprehensive analysis explored correlations between these molecular markers and PET semiquantitative parameters (SUVmax andTBR) to identify potential associations.

Results

The study enrolled 44 patients, with 39 confirmed cases of MLL, comprising 28 hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) and 11 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (ICC). For MLL detection, [18F]FAPI-04 and [18F]FDG exhibited sensitivities of 84.6% (33/39) and 76.9% (30/39), specificitiesy of 60% (3/5) and 100%(5/5), and accuracy of 81.8% (36/44) and 79.5%(35/44). Across all liver lesions, [18F]FAPI-04 significantly surpassed [18F]FDG in SUVmax(10.54 ± 6.72 VS. 7.68 ± 6.79) and TBR(4.35 ± 3.78 Vs. 3.17 ± 3.05). Notably, [18F]FAPI-04 displayed markebly elevated SUVmax in benign liver lesions (BLLs) (P = 0.032), HCCs (P = 0.005), and ICCs (P = 0.011). Lesions with hepatocyte negativity (P = 0.023), CD34 negativity(P = 0.044), and high Ki67 expression (> 30%) (P = 0.001) had higher SUVmax on [18F]FAPI-04. Additionally, ARG-1-negative lesions demonstrated higher TBR on [18F]FAPI-04 than ARG-1-positive lesions(P = 0.018). No significant SUVmax/TBR differences were observed with [18F]FDG based on these markers. A linear relationship was identified between Ki67 scores and SUVmax of [18F]FAPI-04 (R = 0.603, P < 0.001).

Conclusion

[18F]FAPI-04 exhibits superior performance over [18F]FDG in PET/CT evaluation of liver cancer, characterized by increased sensitivity and SUVmax/TBR. Significant correlations with molecular markers, including Ki67, suggest [18F]FAPI-04’s potential for characterizing liver cancer subtypes and assessing tumor proliferation. However, further research is required to validate these findings and their clinical significance.

Trial registration

NCT05485792, Registered 01 August 2022.

Keywords: [18F]FDG, FAPI, PET/CT, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, SUV

Introduction

Liver cancer, characterized by its high aggressiveness, rapid progression, and intricate treatment requirements, poses a substantial public health threat [1]. Early diagnosis and precise assessment of biological behavior are very important for the formulation of personalized treatment strategies and improvement of prognosis in liver tumors. The conventional assessment of tumor biological behavior relies on invasive methods, such as biopsy combined with immunohistochemistry, to understand the molecular expression information of tumors [2]. However, these methods may not only bring additional risks to patients but also affect the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the assessment due to sample limitations.

With the rapid development of molecular imaging technology, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) /Computed Tomography (CT) combined with specific tracers has opened up a new way for non-invasive assessment of tumor biological behavior. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), as a classical PET tracer, has been widely used in tumor evaluation, and has been documented in many literatures to correlate with tumor molecular expression, enabling non-invasive assessment of tumor differentiation [3, 4], proliferation activity [5], and prediction of therapeutic response [6]. However, in the evaluation of liver tumors, the application of [18F]FDG is limited by multiple factors, including the interference from non-neoplastic uptake resulting from inflammation and benign lesions, as well as the high background metabolism of the liver itself. Additionally, the low uptake of [18F]FDG by well-differentiated tumors further impacts the accuracy of its evaluation. In response, previous studies have attempted to enhance the detection of hepatic lesions by combining with other tracers, such as choline [7]. Consequently, there is a pressing need to develop superior tracers to facilitate the monitoring of liver tumors.

In recent years, the series of fibroblast activation protein inhibitors (FAPI) tracers have attracted considerable attention due to their high affinity for fibroblast activation protein in the tumor microenvironment [8]. Existing researches have demonstrated that FAPI tracers exhibit higher uptake and better image contrast than [18F]FDG in various malignant tumors [9, 10]. In particular, the low hepatic background of FAPI makes it particularly promising for liver tumor assessment [11]. These findings suggest that FAPI tracers may have higher diagnostic value and clinical application prospects in liver tumor evaluation. However, current researches on FAPI tracers have largely focused on their tumor detection capabilities in PET images, while the underlying relationship between their metabolic parameters and molecular characteristics of liver tumors remains under-explored.

To address this gap, the present study aims to comprehensively compare the performance of [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 in PET/CT evaluation of liver tumor lesions, thereby revealing the strengths and weaknesses of these two tracers in liver tumor diagnosis. Furthermore, this study will incorporate immunohistochemical analysis to delve into the potential associations between PET semi-quantitative data and molecular features of liver tumors, aiming to provide a more precise method for non-invasive molecular expression assessment of liver tumors and thereby facilitate the development of precision medicine for liver tumors.

Materials and methods

Patients

This prospective study received ethical approval from the institutional review boards of our hospital and has been officially registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT05485792. Throughout the implementation of all methodologies, strict adherence to the approved protocols was ensured. All participating patients willingly provided their written informed consent, authorizing the review of their clinical data for the purpose of this study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they met the following criteria: (a) they had suspected malignant liver lesions, as indicated by conventional diagnostic imaging modalities (including CT, MRI, or ultrasound) in conjunction with clinical manifestations; (b) they underwent PET/CT for tumor assessment between September 2022 and February 2024; (c) they subsequently received [18F]FAPI-04 and [18F]FDG PET/CT scans one week apart; and (d) they had available pathology results pertaining to their liver lesions.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from participation in this study if they (a) were pregnant, (b) were under the age of 18, (c) had undergone anti-tumor therapy prior to the scheduled scans, (d) had failed to provide a signed informed consent form.

PET/CT acquisition

[18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 were synthesized and provided by Guangzhou Atom High Tech Radiopharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China), ensuring a radiochemical purity exceeding 95% for both final products. Imaging utilizing these two tracers was performed using a q PET/CT scanner (Discovery 710, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) within a week.

Prior to [18F]FDG PET/CT scanning, patients were instructed to fast for a minimum of six hours, ensuring venous blood glucose levels remained below 11.1 mmol/L to optimize tracer uptake. In contrast, no such preparatory measures were deemed necessary for[18F]FAPI-04 PET/CT scans. The intravenous injection dose of both [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 was meticulously calculated based on individual patient weights (3.7 MBq [0.1 mCi]/kg).

The CT acquisition parameters were optimized as follows: tube voltage was set at 120 kV, with the current adjusted to 100 mA. Slice thickness was maintained at 3.75 mm, and the matrix resolution was 512 × 512. The scanning span encompassed 7–8 bed positions. Immediately subsequent to the CT scan, a PET scan was initiated in a three-dimensional acquisition mode, spanning 6–8 bed positions, with a duration of 2.0–2.5 min per position and a matrix resolution of 192 × 192.

The accumulated data were seamlessly transferred to an Advantage workstation (AW 4.7, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) for advanced processing. The Bayesian Penalized Likelihood (BPL) algorithm, with a penalization factor (beta) of 750, was employed to reconstruct the data, ensuring optimal image quality for subsequent analysis and interpretation.

PET/CT image analysis

The assessment of both [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 PET/CT images was conducted in a randomized sequence by two experienced nuclear medicine specialists and one radiologist with over a decade of expertise. Any discrepancies in their evaluations were subsequently resolved by consensus. The diagnostic software (Taxus Medivoly Viewer) was utilized for the analysis of PET, CT, and fused PET/CT images.

Initially, the reviewers performed a visual analysis to assess the degree of tracer uptake in liver lesions. The lesions were visually classified as positive or negative, based on whether tracer accumulation within the lesion exceeded that observed in the adjacent normal liver tissue on either [18F]FAPI or [18F]FDG imaging. Furthermore, semi-quantitative data pertaining to liver lesions were acquired. An area of interest (ROI) was designated on the axial PET image, encompassing the entire lesion, following which the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was computed.

Concurrently, a circular ROI with a 10 mm diameter was positioned within the normal hepatic parenchyma, distant from the lesion, meticulously avoiding the course of hepatic vessels and bile ducts. The mean SUV derived from this ROI was documented as the hepatic background uptake. Ultimately, the target-to-background ratio (TBR) was determined using the formula: TBR = SUVmax of liver lesion / SUVmean of hepatic background. Furthermore, the presence or absence of radiological signs indicating fibrosis or fat accumulation in the liver parenchyma of HCC were further assessed .

Pathology and immunohistochemistry

Pathological examination of hepatic lesions was performed on all patients, with 26 cases sourced from surgical resections and 18 cases obtained via biopsy. The pathological findings served as the definitive standard for determining the presence of malignant liver lesions (MLL). All HCC lesions were documented with their Edmondson-Steiner grade (I-II and III-IV). Lesions that exhibited no sign of malignancy upon pathological assessment were conclusively diagnosed as benign liver lesions(BLL), after integrating the available follow-up data. All malignant lesions underwent further immunohistochemical analysis to elucidate their molecular characteristics. The most frequently examined markers, including Glypican-3, Arginase-1(ARG-1), Hepatocyte, Cytokeratin 7 (CK7), Cytokeratin 19 (CK17), and Ki-67, were selected, and their immunohistochemical outcomes were meticulously recorded.

Statistics

The results of visual analysis were summarized using categorical data, which were expressed as counts or percentages (%). Based on these visual analyses, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of both [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI were calculated.

For semiquantitative data, including SUV (Standardized Uptake Value) and TBR (Tumor-to-Background Ratio), continuous statistics were employed. These data were presented as means with standard deviations. To compare the differences in SUV and TBR between [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04, the paired sample t-test was utilized.

The expression status of immunohistochemical markers was also analyzed using categorical data. An independent samples t-test was performed to discern significant differences in the semi-quantitative parameters, SUV and TBR, between distinct expression groups. Given the continuous nature of both Ki67 and SUV, a subsequent linear regression analysis was conducted, complemented by a scatter plot visualization.

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 22.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with statistical significance set at a p-value threshold of < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 44 patients (40 males and 4 females; mean age: 59.32 ± 12.00 years, range: 26–83 years) were consecutively enrolled in this study, undergoing both [18F]FDG PET/CT and [18F]FAPI-04 PET/CT scans within a week of each other. The patient flowchart is depicted in Fig. 1. Among these patients, 39 were histopathologically diagnosed with MLL through surgical resection (n = 26) and liver biopsy (n = 13), comprising 28 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and 11 cases of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). Notably, metastatic lesions were identified in 9 patients (5 ICC and 4 HCC). The remaining 5 patients were ultimately diagnosed with BLL, including 2 inflammatory pseudotumors, 2 inflammatory lesions, and 1 dysplastic nodule.

Fig. 1.

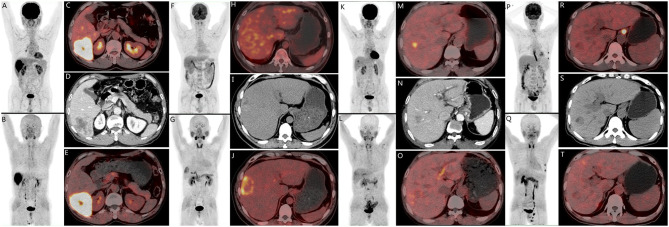

There are four cases of pathologically confirmed hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) with varying PET tracer findings. A-E depicts a 65-year-old male patient with HCC in the S6 segment of the liver(D, Enhanced CT), exhibiting positive tracer uptake on both [18F]FDG (A, MIP; C, PET/CT) and [18F]FAPI-04 (B, MIP; E, PET/CT). E-J represents a 45-year-old male patient with HCC in the S8 segment of the liver (I, CT), showing negative uptake on [18F]FDG(F, MIP; H, PET/CT) but positive uptake on [18F]FAPI-04(G, MIP; J, PET/CT). K-Q illustrates a 74-year-old male patient with HCC in the S7 segment of the liver(N, Enhanced CT), displaying positive uptake on [18F]FDG(K, MIP; M, PET/CT) but negative uptake on [18F]FAPI-0(L, MIP; O, PET/CT)4. Lastly, P-T refers to a 54-year-old male patient with HCC in the S7 segment of the liver(S,CT), demonstrating negative tracer uptake on both [18F]FDG(P, MIP; R, PET/CT) and [18F]FAPI-04 (Q, MIP; T, PET/CT)

Furthermore, 32 patients presented with obvious symptoms of discomfort, with 7 exhibiting jaundice manifestations. Elevated levels of HBV-DNA were observed in 21 patients, while 40 patients had increased tumor markers, and 38 patients had elevated blood transaminases. The clinical characteristics of these patients were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | Value | Percentage(range) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 59.32 ± 12.00 | 26 ~ 82 | |

| ≤ 55 | 16 | 36.4% | |

| >55 | 28 | 63.6% | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 40 | 90.9% | |

| Female | 4 | 9.1% | |

| Presenting symptom | |||

| Yes | 32 | 72.7% | |

| No | 12 | 27.3% | |

| Serum tumor markers | |||

| AFP>7ng/ml | Positive | 26 | 59.1% |

| CEA>6.5 U/ml | Positive | 9 | 20.5% |

| CA199>30 U/ml | Positive | 23 | 52.3% |

| CA724>6.9 U/ml | Positive | 8 | 18.2% |

| Blood transaminases | |||

| ALT > 50 | Positive | 22 | 50.0% |

| AST > 40 | Positive | 29 | 65.9% |

| GGT > 60 | Positive | 36 | 81.8% |

| HBV-DNA > 100 copies/ml | 21 | 47.7% | |

| Final diagnosis | |||

| BLL | 5 | 11.4% | |

| MLL | HCC | 28 | 63.6% |

| ICC | 11 | 25.0% | |

Visual analysis for liver lesions

Among the 39 lesions of MLL, 30 demonstrated positive findings on [18F]FDG PET, achieving a sensitivity of 76.9% (30/39). In contrast, 33 lesions exhibited positivity on [18F]FAPI-04 PET, yielding a higher sensitivity of 84.6% (33/39). Specifically, 27 lesions were positive on both, 3 lesions were positive only on [18F]FDG, 6 lesions were positive only on [18F]FAPI-04, and 3 lesions were negative on both (Fig. 1).

Regarding five lesions of BLL, all failed to demonstrated increased uptake on [18F]FDG PET, resulting in a specificity of 100.0% (5/5). However, one inflammatory pseudotumor (Fig. 2) and one dysplastic nodule showed elevated uptake of [18F] FAPI-04, thereby reducing the specificity of 60.0% (3/5).

Fig. 2.

A case of flammatory pseudotumor. A 50-year-old male patient presented with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and fever for one week. [18F] FDG PET/CT revealed a low-density mass in the left lobe of the liver (segment 4) without abnormal tracer uptake. However, [18F]FAPI-04 PET/CT detected abnormal high tracer uptake in the mass, extending to the liver capsule. The final pathological diagnosis was flammatory pseudotumor

Overall, the accuracy of [18F] FAPI-04 and [18F] FDG in differentiating between BLL and MLL was 81.8% (36/44) and 79.5% (35/44), respectively. The result of visual analysis was shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Visual analysis of liver lesions

| n | [18F]FDG | [18F] FAPI-04 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| positive | negative | positive | negative | ||||

| BLL | 5 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | ||

| MLL | 39 | 30 | 9 | 33 | 6 | ||

| ICC | 11 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 0 | ||

| HCC | 28 | 21 | 7 | 22 | 6 | ||

| Fibrosis or FA | |||||||

| Presence | 15 | 11 | 4 | 10 | 5 | ||

| Absence | 13 | 10 | 3 | 12 | 1 | ||

| Edmonson-Steiner grade | |||||||

| I-II | 16 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 4 | ||

| III-IV | 12 | 11 | 1 | 10 | 2 | ||

FA fat accumulation

Finally, with the integration of [18F] FAPI-04 PET/CT imaging, TN staging adjustments were observed in 9 patients. Specifically, 8 patients had T stage upgrades: 4 due to CT-suspicious lesions confirmed by only [18F]FAPI-04, and 4 due to extensive lesion involvement (capsular or vascular invasion) shown by [18F]FAPI-04. Additionally, one patient had N staging upgrade due to multiple metastatic lymph nodes detected by [18F] FAPI-04.Consequently, their treatment decisions were modified accordingly. Notably, M staging remained unchanged, but radiotherapy protocols were modified for 4 patients due to additional distant metastases identified by [18F]FAPI-04.

Semiquantitative analysis of SUVmax for liver lesion

The comparison of SUV between [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 in all 44 liver lesions was shown in Table 3. A paired sample t-test revealed that the SUV of all lesions was significantly higher with [18F]FAPI-04 than with [18F]FDG (P = 0.012). Specifically, [18F]FAPI-04 demonstrated significantly elevated SUV in BLL (P = 0.032), HCC (P = 0.005), ICC (P = 0.011) (Fig. 3), and Grades III-IV (P = 0.046), and moderately elevated SUV in MLL (P = 0.314) and Grades I-II (P = 0.059), compared to [18F]FDG.

Table 3.

Semiquantitative analysis of SUVmax for liver lesion

| Lesions | N | [18F]FDG | [18F]FAPI-04 | Paired sample t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | 44 | 7.68 ± 6.79 | 10.54 ± 6.72 | t = 2.621,P = 0.012 |

| BLL | 5 | 3.48 ± 1.15 | 7.66 ± 3.40 | t = 3.226, P = 0.032 |

| MLL | 39 | 8.22 ± 7.03 | 10.91 ± 6.97 | t = 1.019, P = 0.314 |

| ICC | 11 | 12.67 ± 10.72 | 15.77 ± 7.35 | t = 2.723, P = 0.011 |

| HCC | 28 | 6.47 ± 3.98 | 9.00 ± 5.91 | t = 3.057, P = 0.005 |

| Edmonson-Steiner | ||||

| Grades I-II | 16 | 5.56 ± 3.65 | 7.47 ± 5.43 | t = 2.046, P = 0.059 |

| Grades III-IV | 12 | 7.69 ± 4.23 | 11.04 ± 6.14 | t = 2.247, P = 0.046 |

Fig. 3.

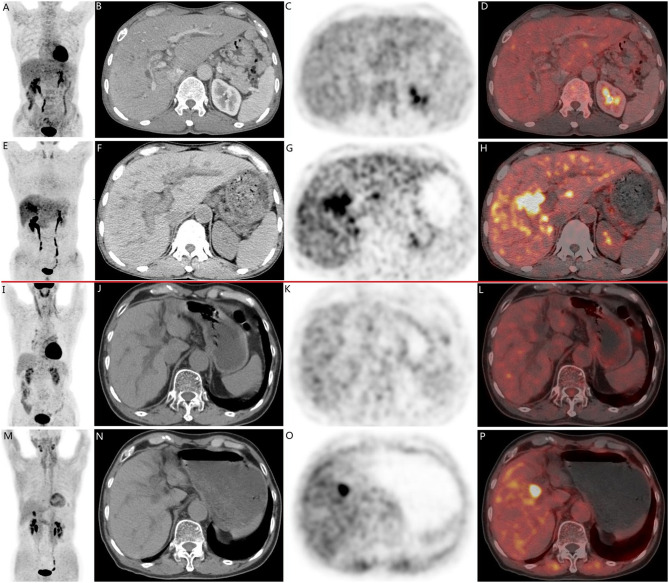

There are two cases of pathologically confirmed intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (ICC) in 68-year-old male patients. In both cases (A-H, case 1; I-P, case 2), CT scans(B, F, case 1; J, N, case 2) revealed intrahepatic bile duct dilation and suspected nodular lesions. While [18F]FDG PET/CT(A, C, D, case 1; I, K, L, case 2) failed to demonstrate abnormal tracer uptake (SUVmax 3.5, TBR 1.3 in Case 1; SUVmax 2.6, TBR 1.2 in Case 2), [18F]FAPI-04 PET/CT (E, G, H, case 1; M, O, P, case 2 ) showed positive uptake in the nodular lesions (SUVmax 9.7, TBR 3.5 in Case 1; SUVmax 9.6, TBR 3.3 in Case 2)

Furthermore, an independent sample t-test confirmed that the SUV of BLL was slightly lower than those of MLL for both [18F]FDG (P = 0.032) and [18F]FAPI-04 (P = 0.314). However, the SUV of HCC was slightly lower than that of ICC for [18F]FDG (P = 0.088), but significantly lower than that of ICC for [18F]FAPI-04 (P = 0.005). Based on the Edmonson–Steiner grades of HCC, Grades I-II exhibited slightly lower SUV compared to Grades III-IV for both [18F]FDG (P = 0.164) and [18F]FAPI-04 (P = 0.115).

Semiquantitative analysis of TBR for liver lesion

The comparison of TBR between [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 across all 44 liver lesions was presenter in Table 4. A paired sample t-test demonstrated a statistically significant elevation in the TBR of all lesions when utilizing [18F]FAPI-04 compared to [18F]FDG (P = 0.033). Specifically, [18F]FAPI-04 demonstrated slightly higher TBR in BLL (P = 0.156), MLL (P = 0.527), HCC (P = 0.447) and ICC (P = 0.617), compared to [18F]FDG.

Table 4.

Semiquantitative analysis of TBR for liver lesion

| Lesions | N | [18F]FDG | [18F]FAPI-04 | Paired sample t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | 44 | 3.17 ± 3.05 | 4.35 ± 3.78 | t = 2.197, P = 0.033 |

| BLL | 5 | 1.33 ± 0.52 | 3.40 ± 3.16 | t = 1.446, p = 0.156 |

| MLL | 39 | 3.33 ± 4.00 | 4.48 ± 3.78 | t = 0.638, p = 0.527 |

| ICC | 11 | 5.38 ± 4.95 | 6.31 ± 4.61 | t = 0.516, P = 0.617 |

| HCC | 28 | 2.63 ± 1.67 | 3.75 ± 3.21 | t = 0.791, P = 0.447 |

| Fibrosis or FA | ||||

| Presence | 15 | 2.48 ± 1.28 | 3.06 ± 2.10 | t = 1.212, P = 0.246 |

| Absence | 13 | 2.79 ± 2.07 | 4.55 ± 4.09 | t = 2.591, P = 0.024 |

FA fat accumulation

Additionally, an independent sample t-test confirmed a slightly lower TBR in BLL compared to MLL for both tracers, [18F]FDG (P = 0.156) and [18F]FAPI-04 (P = 0.527). When contrasting HCC with ICC, the TBR was marginally lower in HCC for both [18F]FDG (P = 0.099) and [18F]FAPI-04 (P = 0.113).

In HCC, when compared to [18F]FDG, [18F]FAPI-04 demonstrated a modestly increased TBR (P = 0.246) in patients with liver fibrosis or fat accumulation. However, in those without liver fibrosis or fat accumulation, [18F]FAPI-04 exhibited a significantly elevated TBR (P = 0.024). Additionally, HCC cases accompanied by liver fibrosis or fat accumulation showed a marginally lower TBR compared to those without these conditions, for both [18F]FDG (P = 0.638) and [18F]FAPI-04 (P = 0.226).

Semiquantitative PET data and immunohistochemical markers in MLL

All pathological specimens of liver malignant lesions (MLL) underwent immunohistochemical analysis. From the plethora of markers assessed, the most frequently evaluated ones were selected for analysis, encompassing Glypican-3, ARG-1, Hepatocyte, CD34, CK7, CK17, and Ki67. The analytical outcomes of these markers were recorded and their associations with semiquantitative PET data (SUV and TBR) were presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Semiquantitative PET data and immunohistochemical markers in MLL

| Markers | N | [18F]FAPI-04 | [18F]FDG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUVmax | TBR | SUVmax | TBR | |||

| Glypican-3 | Positive | 15 | 10.33 ± 8.39 | 4.74 ± 4.47 | 6.91 ± 5.67 | 2.80 ± 2.27 |

| Negative | 18 | 10.49 ± 5.71 | 4.48 ± 3.71 | 9.92 ± 8.73 | 4.13 ± 4.06 | |

| Statistics |

t = 0.063 P = 0.950 |

t = 0.184 P = 0.855 |

t = 1.147 P = 0.260 |

t = 1.129 P = 0.267 |

||

| ARG-1 | Positive | 15 | 8.66 ± 6.29 | 3.04 ± 2.14 | 5.81 ± 3.86 | 2.32 ± 1.60 |

| Negative | 13 | 13.61 ± 7.15 | 6.53 ± 4.39 | 11.85 ± 9.96 | 5.06 ± 4.60 | |

| Statistics |

t = 1.948 P = 0.062 |

t = 2.613* P = 0.018* |

t = 2.057* P = 0.057* |

t = 2.045* P = 0.059* |

||

| Hepatocyte | Positive | 17 | 9.94 ± 6.01 | 3.97 ± 3.27 | 6.81 ± 4.57 | 2.76 ± 1.89 |

| Negative | 13 | 15.54 ± 6.74 | 6.60 ± 4.39 | 12.28 ± 9.86 | 5.24 ± 4.53 | |

| Statistics |

t = 2.398 P = 0.023 |

t = 1.883 P = 0.070 |

t = 2.026 P = 0.052 |

t = 2.038 P = 0.051 |

||

| CK7 | Positive | 14 | 12.41 ± 8.01 | 5.25 ± 4.37 | 10.21 ± 9.15 | 4.16 ± 4.22 |

| Negative | 9 | 7.57 ± 5.49 | 3.96 ± 3.01 | 4.86 ± 2.27 | 2.07 ± 1.32 | |

| Statistics |

t = 1.585 P = 0.128 |

t = 0.772 P = 0.449 |

t = 1.710 P = 0.102 |

t = 1.430 P = 0.167 |

||

| CK19 | Positive | 12 | 13.63 ± 8.23 | 6.79 ± 4.63 | 13.62 ± 9.63 | 5.94 ± 4.33 |

| Negative | 10 | 10.32 ± 6.25 | 4.83 ± 3.78 | 7.52 ± 5.05 | 3.01 ± 2.04 | |

| Statistics |

t = 1.045 P = 0.308 |

t = 1.067 P = 0.299 |

t = 1.801 P = 0.087 |

t = 1.960 P = 0.064 |

||

| Ki67 | >30% | 13 | 15.82 ± 4.03 | 6.14 ± 3.56 | 8.92 ± 4.05 | 3.73 ± 1.65 |

| ≤ 30% | 26 | 8.46 ± 6.88 | 3.65 ± 3.67 | 7.87 ± 8.18 | 3.24 ± 3.72 | |

| Statistics |

t = 3.551 P = 0.001 |

t = 2.016 P = 0.051 |

t = 0.432 P = 0.669 |

t = 0.457 P = 0.651 |

||

Independent sample t-tests indicated that lesions with Hepatocyte negativity (P = 0.023), CD34 negativity(P = 0.044), and high KI67 expression (> 30%) (P = 0.001) exhibited significantly higher SUVmax on [18F]FAPI-04 compared to their respective positive counterparts. Additionally, ARG-1-negative lesions demonstrated a obviously higher TBR on [18F]FAPI-04 than ARG-1-positive lesions(P = 0.018). Conversely, no significant differences were observed in the SUVmax or TBR of [18F]FDG between the positive and negative results of these markers.

Linear regression analysis between Ki67 and SUVmax of [18F]FAPI-04 in MLL

Given the continuous nature of both Ki67 and SUVmax, a deeper exploration into their linear relationship was warranted. As depicted in Fig. 4, a scatter plot illustrates the distribution of Ki67 scores against the corresponding SUVmax of [18F]FAPI-04. A linear regression analysis conducted on these data points confirms a significantly linear relationship between Ki67 scores and SUVmax of [18F]FAPI-04 (R = 0.603, P = 0.000 ) .

Fig. 4.

The scatter plot of Ki67 scores and SUVmax of [18F]FAPI-04

Discussion

As a novel PET tracer, FAPI labeled with either [18F] or [68Ga] has been widely reported for its application across various malignant tumors, most of them mainly focus on the head-to-head comparison between FDG and FAPI, evaluating their diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, and overall value in malignancy detection [12, 13]. However, the relationship between FAPI and tumor molecular markers remains understudied and unreported. This study not only conventionally compares the diagnostic results of [18F]FDG and [18F]FAPI-04 for suspected malignant liver lesions, but also systematically analyzes the relationship between PET semi-quantitative parameters and immunohistochemical markers. It aims to comprehensively assess liver tumor characteristics through non-invasive approach, thereby advancing personalized medicine.

The advantages demonstrated by FAPI PET in the assessment of liver tumors have garnered increasing attention. In PET/CT evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), 68Ga-FAPI-04 exhibits a markedly enhanced diagnostic sensitivity, achieving a sensitivity of 85.7%, significantly surpassing the 57.1% of 18F-FDG [14]. For liver lesion detection, [68Ga]-FAPI-04 PET/CT yielded a higher detection rate (87.4%) than [18F]-FDG PET/CT (65.0%) [15]. In non-[18F]FDG-avid focal liver lesions, [18F]FAPI PET demonstrated 96.0% sensitivity, 58.3% specificity, and 83.8% accuracy, emphasizing its effectiveness in malignancy detection [16]. Consistent with these findings, the present study reveals that [18F]FAPI-04 exhibits a higher sensitivity (84.6% vs. 76.9%) than [18F]FDG in identifying malignant liver lesions (MLL), further confirming the superiority of [18F]FAPI-04 over [18F]FDG in hepatic malignancy evaluation. This advantage arises from FAPI’s independence from glucose metabolism, effectively decreasing physiological uptake interference, enhancing tumor-to-background ratios and image contrast, facilitating precise detection. Furthermore, FAPI imaging also streamlines workflow by eliminating the need for patient fasting, improving patient comfort.

However, the clinical application of FAPI inevitably encounters certain limitations, particularly the occurrence of false positives. Some previous reports have indicated a higher incidence of false positives in liver lesions with FAPI compared to FDG, leading to reduced specificity. Singh P [17] observed a significantly lower specificity for FAPI PET/CT (56.1%) than 18F-FDG PET/CT (96.4%) in detecting primary liver tumors. Zhang J [16] also reported a sensitivity of only 58.3% for [18F]FAPI in non-[18F]FDG-avid liver malignancies. In this study, among 5 benign liver lesions, 2 exhibited false-positive FAPI findings, whereas FDG showed no false-positive uptake. These false positives were predominantly noted in non-neoplastic inflammatory lesions, albeit in a small number, posing a potential risk of misdiagnosis. In addition, despite enhanced sensitivity for hepatic malignancies, FAPI fails to achieve 100%, yielding inevitable false negatives and the risk of missed diagnoses. The precise mechanisms underlying FAPI false-negativity remain unclear, potentially linked to intratumoral heterogeneity in FAPI expression levels and the intricate nature of the tumor microenvironment. In this study, among 39 hepatic malignant lesions, 6 were false negatives on FAPI, all of which were HCC foci. Thus, meticulous interpretation of FAPI PET, integrated with multimodal imaging, pathology, and clinical data, is vital for enhancing diagnostic accuracy in clinical practice.

In the evaluation of PET/CT imaging, beyond conventional visual analysis, semiquantitative analysis utilizing metabolic parameters such as SUV and TBR is crucial for tracer comparison studies. Siripongsatian D [18] and Pabst KM [19] both emphasized the benefits of 68Ga-FAPI-46 in detecting intrahepatic lesions and identifying primary cholangiocarcinoma, highlighting its superior SUVmax and TBR compared to [18F]FDG. The results of this study reinforce these reports, showing [18F]FAPI-04’s superior SUV and TBR over [18F]FDG in whole liver lesions. Furthermore, the relationships between PET metabolic parameters and pathological differentiation, prognosis, and molecular characteristics are continually being explored and uncovered. The SUVmax of [18F]FDG were utilized to differentitate intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHCC) from HCC [20], pelvis renalis cancer (PRC) from renal cell cancer (RCC) [21], and lung adenocarcinomas (AC) from lung squamous carcinomas (SCC) [22]. Metabolic parameters, including SUV, metabolic tumor volume (MTV), and total lesion glycolysis (TLG), were observed to have significant potential in assessing treatment efficacy for primary bone lymphoma [23] and metastatic breast cancer (MBC) [24]. Additionally, some reports reveal a close relationship between the SUV of 18F-FDG and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) [25], estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) [26], and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) [27], highlighting the multifaceted significance of these metabolic markers in clinical oncology.

However, the majority of above researches has focused on 18F-FDG-based parameters, while the clinical significance of FAPI-based parameters has only been explored by a few reports, primarily concentrating on fibroblast activation protein (FAP) molecular expression. Shi X [28] demonstrated that the 68Ga-FAPI-04 uptake was associated with FAP expression in hepatic malignancie. This study specifically delves into the relationship between FAPI metabolic parameters and various immunohistochemical indicators of hepatic malignancies, with the aim of further exploring the clinical significance of FAPI. Based on its results, it is revealed, for the first time, that significant associations between elevated SUVmax and TBR of 18F-FAPI-04 with hepatocyte-negative expression and ARG-1-negative lesions, respectively. Notably, Hepatocyte and ARG-1, the key immunohistochemical markers distinguishing HCC from ICC, is predominantly expressed in HCC. Thus, the high SUV in hepatocyte-negative lesions and high TBR in ARG-1-negative lesions imply ICC’s high affinity for [18F]FAPI-04. Furthermore, this study observed a close positive correlation between [18F]FAPI-04 SUV and Ki67 expression, which is a noteworthy finding. Previous studies have confirmed a significant positive correlation between [18F]FDG SUV and Ki-67 expression in primary esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [29] and adrenocortical carcinomas [30]. Although this study did not establish a direct role for [18F]FDG SUV in differentiating high Ki67 expression in hepatic malignant lesions, it confirmed a strong positive correlation between [18F]FAPI-04 SUV and Ki67. This finding suggests that 18F-FAPI-04 has greater potential than 18F-FDG for non-invasive proliferation assessment of hepatic lesions, offering a new perspective for evaluating tumor biological behavior. However, it is crucial to validate these findings through large-scale studies.

The present study is primarily limited by the relatively small sample size derived from a single institution, particularly within the non-malignant lesion cohort, which may compromise the precision of specificity estimates. Moreover, the correlations established between PET parameters and molecular markers necessitate validation in larger, multi-center cohorts to ensure their robustness, reproducibility, and generalizability. Additionally, future research should encompass a wider array of molecular biomarkers to investigate their associations with FAPI metabolic parameters,, thereby facilitating a deeper understanding of the role of FAPI in characterizing subtypes of hepatic malignancies, predicting therapeutic efficacy, and monitoring disease progression.

In liver cancer detection, novel molecular targets such as PSMA [31] (prostate specific membrane antigen) and glypican-3 [32] are continually identified. Compared to FAPI, these targets can offer higher specificity in liver cancer detection, but often limited to specific tumor types or subtypes. In contrast, FAPI, as a broad-spectrum tumor tracer, demonstrates robust clinical feasibility and applicability. FAPI PET boasts high sensitivity, simplified imaging, and a close correlation with tumor biological behavior, aiding in the assessment of tumor status and prognosis. Despite the emergence of novel platforms for precise detection, FAPI PET remains a crucial imaging modality in liver cancer management, providing valuable insights for clinical decision-making.

Conclusions

In conclusion, [18F]FAPI-04 exhibits superior performance over [18F]FDG in PET/CT evaluation of liver cancer lesions, characterized by increased sensitivity and SUVmax/TBR. Significant correlations with molecular markers, such as Ki67, suggest [18F]FAPI-04’s potential for characterizing liver cancer subtypes and assessing tumor proliferation. However, further research is required to validate these findings and their clinical significance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank “Guangzhou key medicine discipline construction project fund”.

Author contributions

Zhiying Liang : collected the data, analyzed the data and wrote the paper .Hao Peng : analyzed the data, conceived and designed the study.Wei Li: conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data, wrote the paper and reviewed the final manuscript.Zhidong Liu: reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Guangzhou Institute of Cancer Research, the Affiliated Cancer Hospital, Guangzhou Medical University, and written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yan T, Yu L, Zhang N, Peng C, Su G, Jing Y, et al. The advanced development of molecular targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Med. 2022;19:802–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan ES, Yeh MM. The use of immunohistochemistry in liver tumors. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:687–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maman A, Sahin A, Ayan AK. The relationship of SUV Value in PET-CT with Tumor differentiation and tumor markers in gastric Cancer. Eurasian J Med. 2020;52:67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozturk K, Gencturk M, Caicedo-Granados E, Li F, Cayci Z. Utility of FDG PET/CT in the characterization of Sinonasal neoplasms: analysis of standardized uptake value parameters. Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211:1354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoeben BA, Starmans MH, Leijenaar RT, Dubois LJ, van der Kogel AJ, Kaanders JH, et al. Systematic analysis of 18F-FDG PET and metabolism, proliferation and hypoxia markers for classification of head and neck tumors. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao PF, Lu N, Liu W. MRI VS. FDG-PET for diagnosis of response to neoadjuvant therapy in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1031581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyakale NE, Aldous C, Gutta AA, Khuzwayo X, Harry L, Sathekge MM. Emerging theragnostic radionuclide applications for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Nucl Med. 2023;3:1210982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altmann A, Haberkorn U, Siveke J. The latest developments in imaging of fibroblast activation protein. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watabe T, Naka S, Tatsumi M, Kamiya T, Kimura T, Shintani Y, et al. Initial evaluation of [18F]FAPI-74 PET for various histopathologically confirmed cancers and Benign lesions. J Nucl Med. 2023;64:1225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dendl K, Finck R, Giesel FL, Kratochwil C, Lindner T, Mier W, et al. FAP imaging in rare cancer entities-first clinical experience in a broad spectrum of malignancies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I. 2022;49:721–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manuppella F, Pisano G, Taralli S, Caldarella C, Calcagni ML. Diagnostic performances of PET/CT using fibroblast activation protein inhibitors in patients with primary and metastatic liver tumors: a Comprehensive Literature Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gege Z, Xueju W, Bin J. Head-To-Head comparison of 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT and FDG PET/CT for the detection of peritoneal metastases: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Am J Roentgenol. 2023;220:490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wegen S, van Heek L, Linde P, Claus K, Akuamoa-Boateng D, Baues C, et al. Head-to-Head comparison of [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-46-PET/CT and [18F]F-FDG-PET/CT for Radiotherapy Planning in Head and Neck Cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2022;24:986–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Zhu W, Ren S, Kong Y, Huang Q, Zhao J, et al. 68Ga-FAPI-04 Versus 18F-FDG PET/CT idetectionection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:693640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo W, Pang Y, Yao L, Zhao L, Fan C, Ke J, et al. Imaging fibroblast activation protein in liver cancer: a single-center post hoc retrospective analysis to compare [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 PET/CT versus MRI and [18F]-FDG PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I. 2021;48:1604–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, He Q, Jiang S, Li M, Xue H, Zhang D, et al. [18F]FAPI PET/CT in the evaluation of focal liver lesions with [18F]FDG non-avidity. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I. 2023;50:937–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh P, Singhal T, Parida GK, Rahman A, Agrawal K. Diagnostic performance of FAPI PET/CT vs. 18F-FDG PET/CT in evaluation of liver tumors: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Mol Imaging Radionuc. 2024;33:77–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siripongsatian D, Promteangtrong C, Kunawudhi A, Kiatkittikul P, Boonkawin N, Chinnanthachai C, et al. Comparisons of quantitative parameters of Ga-68-Labelled fibroblast activating protein inhibitor (FAPI) PET/CT and [18F]F-FDG PET/CT in patients with liver malignancies. Mol Imaging Biol. 2022;24:818–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pabst KM, Trajkovic-Arsic M, Cheung PFY, Ballke S, Steiger K, Bartel T, et al. Superior Tumor Detection for 68Ga-FAPI-46 Versus 18F-FDG PET/CT and conventional CT in patients with Cholangiocarcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2023;64:1049–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokmen BK, Inan N. 18F-FDG PET/Mprimaryrhepaticemalignanciesancies: Differediagnosisgnosihistologicogradingrading. Curr Med Imaging. 2024;20:e080523216636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dursun M, Ozbek E, Otunctemur A, Besiroglu H. Differentiating renal pelvic cancer from renal cell carcinoma with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography. J Cancer Res Ther. 2021;17:901–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu WD, Wang HC, Wang YB, Cui LL, Chen XH. Correlation study on 18F-FDG PET/CT metabolic characteristics of primary lesion with clinical stage in lung cancer. Q J Nucl Med Mol Im. 2021;65:172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pu Y, Wang C, Xie R, Zhao S, Li K, Yang C, et al. Role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/computed tomography in the diagnosis and treatment response assessment of primary bone lymphoma. Nucl Med Commun. 2023;44:318–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Liu C, Wang B, Hu X, Gong C, Zhao Y, et al. Prediction of pretreatment 18F-FDG-PET/CT parameters on the outcome of first-line therapy in patients with metastatic breast Cancer. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:1797–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshikawa T, Endo K, Moriyama-Kita M, Ueno T, Nakanishi Y, Dochi H, et al. Association of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake with the expression of metabolism- related molecules in papillary thyroid cancer. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2024;51:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arslan E, Aksoy T, Can Trabulus FD, Kelten Talu C, Yeni B, Çermik TF. The association of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/computed tomography parameters with tissue gastrin-releasing peptide receptor and integrin αvβ3 receptor levels in patients with breast cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2020;41:260–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang D, Li Y, Chen X, Li P. Prognostic significance of volume-based 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters and correlation with PD-L1 expression in patients with surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma. Medicine. 2021;100:e27100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi X, Xing H, Yang X, Li F, Yao S, Zhang H, et al. Fibroblast imaging of hepatic carcinoma with 68Ga-FAPI-04 PET/CT: a pilot study in patients with suspected hepatic nodules. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I. 2021;48:196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu L, Huang Y, Guo J, Wang Z, Song D. Correlation between FDG PET/CT and the expression of Ki-67, MMP-2, micro-vessel density (MVD), and pathological grading in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:e15556. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Libé R, Pais A, Violon F, Guignat L, Bonnet F, Huillard O, et al. Positive correlation between 18F-FDG uptake and tumor-proliferating Antigen Ki-67 expression in Adrenocortical Carcinomas. Clin Nucl Med. 2023;48:381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirmas N, Leyh C, Sraieb M, Barbato F, Schaarschmidt BM, Umutlu L, et al. 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT Improves Tumor Detection and Impacts Managemepatientstients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:1235–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An S, Zhang D, Zhang Y, Wang C, Shi L, Wei W et al. GPC3-targeted immunoPET imaging of hepatocellular carcinomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022, 49:2682–2692. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript.