Abstract

AlphaFold2 revolutionized structural biology with the ability to predict protein structures with exceptionally high accuracy. Its implementation, however, lacks the code and data required to train new models. These are necessary to (1) tackle new tasks, like protein–ligand complex structure prediction, (2) investigate the process by which the model learns and (3) assess the model’s capacity to generalize to unseen regions of fold space. Here we report OpenFold, a fast, memory efficient and trainable implementation of AlphaFold2. We train OpenFold from scratch, matching the accuracy of AlphaFold2. Having established parity, we find that OpenFold is remarkably robust at generalizing even when the size and diversity of its training set is deliberately limited, including near-complete elisions of classes of secondary structure elements. By analyzing intermediate structures produced during training, we also gain insights into the hierarchical manner in which OpenFold learns to fold. In sum, our studies demonstrate the power and utility of OpenFold, which we believe will prove to be a crucial resource for the protein modeling community.

Predicting protein structure from sequence has been a defining challenge of biology for decades1,2. Building on a line of work applying deep learning to coevolutionary information encoded in multiple-sequence alignments (MSAs)3-8 and homologous structures9,10, AlphaFold2 (ref. 11) has arguably solved the problem for natural proteins with sufficiently deep MSAs. The model has been made available to the public with DeepMind’s official open-source implementation, which has enabled researchers to optimize AlphaFold2’s prediction procedure and user experience12 and to employ it as a module within novel algorithms, including ones for protein complex prediction13, peptide–protein interactions14, structure ranking15 and more (for example, refs. 16-18). It has also been used to predict the structures of hundreds of millions of proteins19-21.

In spite of its utility, the official AlphaFold2 implementation omits code for the model’s complex training procedure as well as the computationally expensive data required to run it. This makes it difficult to (1) investigate AlphaFold2’s learning behavior and sensitivity to changes in data composition and model architecture and (2) create variants of the model to tackle new tasks. Given the success of AlphaFold2, its many novel components are likely to prove useful for tasks beyond protein structure prediction. For instance, retraining AlphaFold2 using a dataset of protein–protein complexes resulted in AlphaFold2-Multimer22, the state-of-the-art model for predicting structures of protein complexes. Until recently, however, this capability has been exclusive to DeepMind.

To address this shortcoming, we developed OpenFold, a trainable open-source implementation of AlphaFold2. We trained OpenFold from scratch using OpenProteinSet23, our open-source reproduction of the AlphaFold2 training set, matching AlphaFold2 in prediction quality. Apart from new training code and data, OpenFold has several advantages over AlphaFold2: (1) it runs between three and five times faster for most proteins, (2) it uses less memory, allowing prediction of extremely long proteins and multi-protein complexes on a single graphics processing unit (GPU), and (3) it is implemented in PyTorch24, the most widely used machine learning framework (AlphaFold2 uses Google’s JAX25). As such, OpenFold can be readily used by the widest community of developers and interfaces with a rich ecosystem of existing machine learning software26-29.

Taking advantage of our discovery that ~90% of model accuracy can be achieved in ~3% of training time, we retrained OpenFold multiple times on specially elided versions of the training set to quantify its ability to generalize to unseen protein folds. Surprisingly, we found the model fairly robust even to large elisions of fold space, but its capacity to generalize varied based on the spatial extent of protein fragments and folds. We observed even stronger performance when training the model on more diverse but smaller datasets, some as small as 1,000 experimental structures. Next, we used OpenFold to understand how the model learns to fold proteins, focusing on the geometric characteristics of predicted structures during intermediate stages of training. In sum, these results yield fundamental new insights into the learning behavior of AlphaFold2-type models and provide new conceptual and practical tools for the development of biomolecular modeling algorithms.

Results

OpenFold matches AlphaFold2 in accuracy

OpenFold reproduces the AlphaFold2 model architecture in full, without any modifications that could alter its internal mathematical computations. This results in perfect interoperability between OpenFold and AlphaFold2, enabling use of the original AlphaFold2 model parameters within OpenFold and vice versa. To verify that our OpenFold implementation recapitulates all aspects of AlphaFold2 training, we used it to train a new model from scratch. OpenFold and AlphaFold2 training requires a collection of protein sequences, MSAs and structures. As the AlphaFold2 MSA database has not been publicly released, we used OpenProteinSet23, a replication of the AlphaFold2 training dataset that substitutes newer versions of sequence databases when available. Starting from approximately 15 million Uniclust30 (ref. 30) MSAs, we selected approximately 270,000 diverse and deep MSAs to form a ‘self-distillation’ set; such sets are used to augment experimental training data with high-quality predictions. We predicted protein structures for all MSAs in this set using AlphaFold2 and combined them with approximately 132,000 unique (640,000 non-unique) experimental structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB)31 to form the OpenFold training dataset. During training on self-distillation proteins, residues with a low AlphaFold2 confidence score (<0.5 pLDDT (predicted Local Distance Difference Test)) were masked. Our validation set consisted of nearly 200 structures from CAMEO32, an online repository for continuous quality assessment of protein structure prediction models, drawn over a 3-month period ending on 16 January 2022.

From our main training run, we selected seven snapshots to form a collection of distinct (but related) models. During prediction time, these models can generate alternate structural hypotheses for the same protein. To further increase the diversity of this collection, we fine-tuned a second set of models that we branched off from the main model. In this second branch, we disabled the model’s template pipeline, similar to the procedure used for AlphaFold2. Selected snapshots from this branch were added to the pool of final models, resulting in a total of ten distinct models. Full training details are provided in Training details.

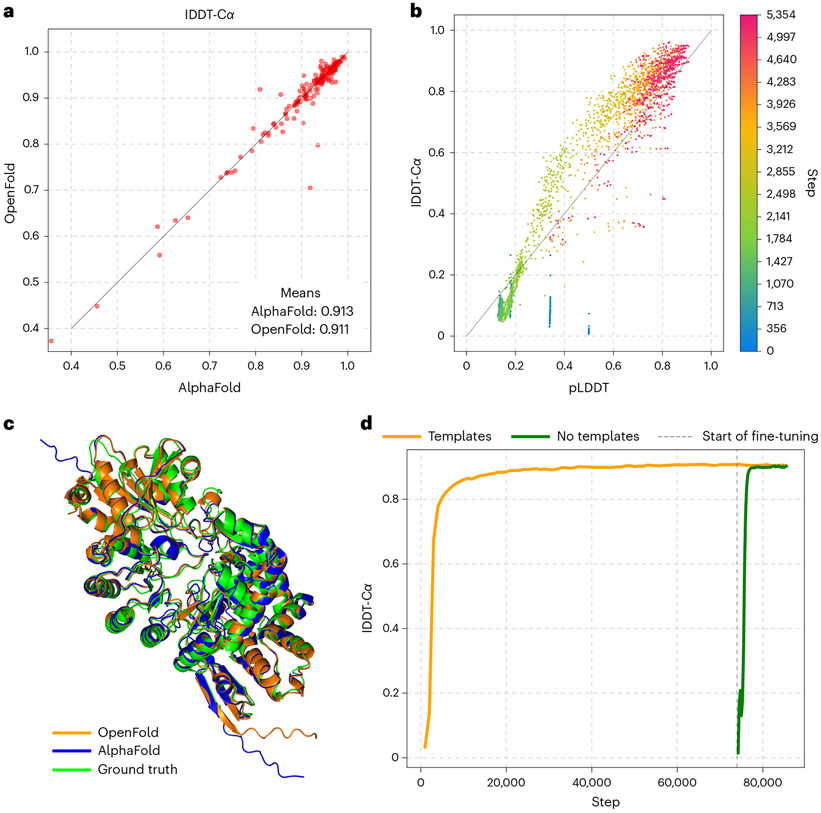

We summarize the main results of our training experiment in Fig. 1. Predictions made by OpenFold and AlphaFold2 on the CAMEO validation set are assessed using the lDDT-Cα33 (Local Distance Difference Test with respect to the alpha carbon) metric (Fig. 1a) and show very high concordance between OpenFold and AlphaFold2, demonstrating that OpenFold successfully reproduces AlphaFold2. While OpenFold was still training for much of the CASP15 (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction) competition, our retrospective evaluation shows that the final model achieves parity on CASP15 domains as well (Extended Data Fig. 1). Fig. 1c provides a visual illustration of this concordance. Tracking prediction accuracy as a function of training stage (Fig. 1d) reveals the remarkable fact that OpenFold achieves ~90% of its final accuracy in just 1,500 GPU hours (~3% of training time) and ~95% in 2,500 GPU hours; total training time is approximately 50,000 GPU hours. Although we will show that the extended second phase of training does play an important role in learning more detailed physical interactions, this rapid rise in accuracy suggests that training of performant OpenFold variants can be accomplished with far less compute than is necessary for full model training, facilitating rapid exploration of model architectures. We take advantage of this fact in our data elision experiments.

Fig. 1 ∣. OpenFold matches the accuracy of AlphaFold2.

a, Scatterplot of lDDT-Cα values of AlphaFold and OpenFold predictions on the CAMEO validation set. b, Average pLDDT versus lDDT-Cα values of OpenFold predictions on the CAMEO set during the early stage of training. OpenFold is initially overconfident but quickly becomes underconfident, gradually converging to accurate confidence estimation. c, Predictions by OpenFold and AlphaFold2 overlaid with an experimental structure of Streptomyces tokunonesis TokK protein (ref. 59; PDB accession code 7KDX_A). d, Average lDDT-Cα for OpenFold computed over the training set during the course of training. The template-free branch is shown in green, the template-using one is in orange, and the initial training and/or fine-tuning boundary is in gray. Template-free accuracy is initially poor because the exponential moving average of the weights used for validation was being reinitialized.

AlphaFold2 training is broadly split into two phases: an initial training phase and a more computationally intensive fine-tuning phase. In the latter, the size of protein fragments used for training is increased to 384 residues and an additional loss function that penalizes structural violations (for example, steric clashes) is enabled. By comparing predicted structures between the initial and fine-tuning phases, we find that the second phase has only a modest effect on overall structural quality metrics, even when considering only long proteins more than 500 residues in length (Extended Data Fig. 3). Instead, the primary utility of fine-tuning appears to be to resolve violations of known chemical constraints. In our training experiments, this occurs quickly after the beginning of fine-tuning, suggesting that elided fine-tuning runs can be used with minimal impact on prediction quality.

In addition to prediction accuracy, we also tracked pLDDT as a function of training stage. pLDDT is the model’s estimate of the lDDT-Cα of predicted structures and serves as its primary confidence metric. We find that pLDDT is well correlated with true lDDT early in training, albeit initially overconfident in its self-assessment and later entering a phase of underconfidence (Fig. 1b). It is notable that the model is capable of assessing the quality of its own predictions early on in training, when its overall predictive capacity remains very limited.

OpenFold can achieve high accuracy using tiny training sets

Having established the equivalency of AlphaFold2 and OpenFold, we set out to understand properties of the architecture, starting with its data efficiency. AlphaFold2 was trained using ~132,000 protein structures from the PDB, the result of decades of painstaking and expensive experimental structure determination efforts. For other molecular systems for which AlphaFold2-style models may be developed, data are far more sparse; for example, the PDB contains only 1,664 RNA structures. We wondered whether the high accuracy achieved by AlphaFold2 in fact depended on its comparatively large training set or whether it is possible to achieve comparable performance using less data. Were the latter to be true, it would suggest broad applicability of the AlphaFold2 paradigm to molecular problems. To investigate this possibility, we performed a series of OpenFold training runs in which we used progressively less training data, assessing model accuracy as a function of training set size.

Our first set of tests randomly subsample the original training data to 17,000, 10,000, 5,000, 2,500, 2,000 and 1,000 protein chains. We used each subsampled set to train OpenFold for at least 7,000 steps, through the initial rapid rise phase to early convergence. To avoid information leakage from the full training set, we did not use self-distillation, putting the newly trained models at a disadvantage relative to the original OpenFold. We trained models with and without structural templates. In all other regards, training was identical to that of the standard OpenFold model. Model accuracy (assessed using lDDT-Cα) is plotted as a function of training step in Fig. 2a, with colors indicating the size of the training set used.

Fig. 2 ∣. OpenFold generalization capacity on elided training sets.

a, Validation set lDDT-Cα values as a function of training step for models trained on elided training sets (10,000 random split repeated 3× demonstrates inter-run variance). b, Same as a but for CATH-stratified dataset elisions. Validation sets vary across stratifications and are not directly comparable. c, Experimental structures (orange) and mainly α-trained (yellow) and mainly β-trained (red) predictions of largely helical Lsi1 (top) and β-sheet-heavy TMED1 (bottom).

We find that merely 10,000 protein chains (about 7.6% of all training data (yellow curves)) suffice to reach essentially the same initial lDDT-Cα value as a model trained on the full training set (pink curve). After 20,000 steps (not pictured), the full data model reaches a peak lDDT-Cα of 0.83, while, after 7,000 steps, the 10,000-sample model has already exceeded 0.81 lDDT-Cα. Although performance gradually degrades as training set size decreases further and even though the rate of convergence does seem to be quite variable across random seeds (as demonstrated by the repeated 10,000 ablation in Fig. 2a, right), we find that all models are surprisingly performant, even ones trained on our smallest subsample of 1,000 protein chains, corresponding to just 0.76% of the full training set. We stress the important caveat that lDDT is not the only measure of a model’s success; models trained for such a short time do not learn, for example, uncommon secondary structure elements (SSEs) (Fig. 4) or the implicit biophysical energy function acquired by the fully trained model15 (see Extended Data Fig. 2 and the Supplementary Discussion (section B.1) for details). Nevertheless, these results clearly set AlphaFold2 apart from prior protein structure prediction models. The 1,000-chain ablation reaches an lDDT-Cα of 0.64, exceeding the median lDDT-Cα of 0.62 achieved at CASP13 by the first AlphaFold, the best performing model at the time.

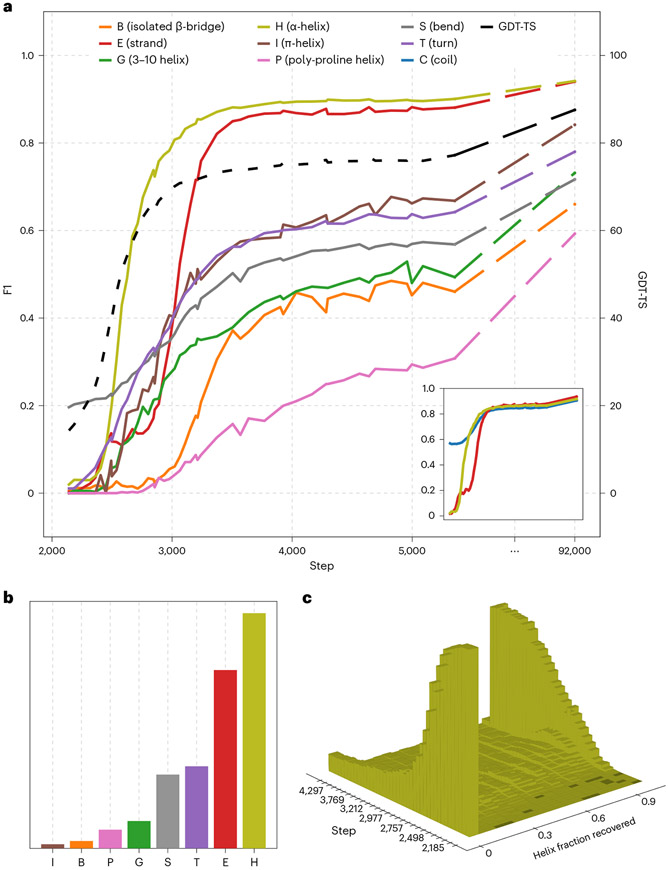

Fig. 4 ∣. Secondary structure categories are learned in succession.

a, F1 scores for secondary structure categories over time. The corner pane depicts the same data using a simplified three-state assignment (details are in the Supplementary Discussion (section B.5)). GDT-TS and final values are also provided. b, Corresponding counts of individual secondary structure assignments. c, Contiguous fractions of individual helices recovered early in training.

Comparing the accuracies of models trained with and without templates, we find that templates on average contribute little to early prediction quality even in the low-data setting. This is consistent with the original AlphaFold2 ablation studies, which showed that templates have a minimal effect except when MSAs are shallow or entirely absent.

OpenFold generalizes to unseen regions of fold space

Randomly subsampling the OpenFold training set, as in the previous analysis, reduces the quantity of the training data used but not necessarily the overall diversity. In molecular modeling tasks, the data available for training often do not reflect the underlying diversity of the molecular system being modeled, due to biases in the scientific questions pursued, experimental assays available, etc. To assess OpenFold’s capacity to generalize to out-of-distribution data, we subsample the training set in a structurally stratified manner such that entire regions of fold space are excluded from training but retained for model assessment. Multiple structural taxonomies for proteins exist, including the hierarchical classification of protein domain structures (CATH)34,35 and structural classification of proteins (SCOP)36 classification systems. For this task, we use CATH, which assigns protein domains, in increasing order of specificity, to a class (C), architecture (A), topology (T) and homologous superfamily (H). Domains with the same homologous superfamily classification may differ superficially but have highly similar structural cores. Our preceding analysis can be considered to structurally stratify data at the homologous superfamily level. For the present analysis, we stratify data further, holding out entire topologies, architectures and classes.

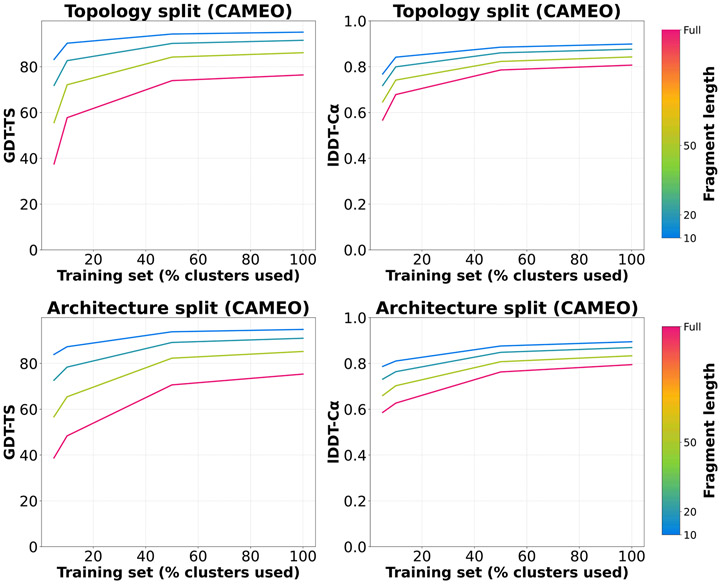

We start by filtering out protein domains that have not been classified by CATH, leaving ~440,000 domains spanning 1,385 topologies, 42 architectures and four classes. For the topology stratification, we randomly sample 100 topologies and remove all associated chains from the training set. We construct a validation set from the held-out topologies by sampling one representative chain from each. We also construct successively smaller training sets from shrinking fractions of the remaining topologies, including a training set that encompasses all of them. We follow an analogous procedure for architectures except that, in this case, the validation set consists of 100 chains randomly selected from five architectures (20 per architecture). For class-based stratification, the validation set comprises domains that are neither in the mainly α nor mainly β classes, hence enriching for domains with high proportions of both SSEs. For training, we construct two sets, one corresponding exclusively to the mainly α class and another to the mainly β class; this enables us to ascertain the capability of models trained largely on either α-helices or β-sheets to generalize to proteins containing both. For all stratifications, we train OpenFold to early convergence (~7,000 steps) from scratch. To prevent leakage of structural information from held-out categories, all runs are performed without templates. We plot model accuracies as a function of training step in Fig. 2b, with colors indicating the fraction of categories retained during training for each respective level of the CATH hierarchy.

As expected, removing entire regions of fold space has a more dramatic effect on model performance than merely reducing the size of the training set. For example, retaining 10% of topologies for training (green curve in Fig. 2b, topology split), which corresponds to ~6,400 unique chains, results in a model less performant than one containing 5,000 randomly selected chains (green curve in Fig. 2a, no templates). However, even in the most severe elisions of training set diversity, absolute accuracies remain unexpectedly high. For instance, the training set containing 5% of topologies (2,000 chains) still achieves an lDDT-Cα near 0.6, comparable again to results of the first AlphaFold, which was trained on over 100,000 protein chains. Similarly, the training set for the smallest architecture-based stratification only contains domains from one architecture (of 42 that cover essentially the entirety of the PDB), yet it peaks near 0.6 lDDT-Cα. Most surprisingly, the class-stratified models, in which α-helices or β-sheets are almost entirely absent from training, achieve very high lDDT-Cα scores of >0.7 on domains containing both α-helices and β-sheets. These models likely benefit from the comparatively large number of unique chains in their training sets: 15,400 and 21,100 for α-helix- and β-sheet-exclusive sets, respectively. It should also be noted that the mainly α and mainly β categories do contain small fractions of β-sheets and α-helices, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 4). Despite these caveats, the model is being tasked with a very difficult out-of-distribution generalization problem in which unfamiliar types of SSEs (from the perspective of the training set) have to essentially be inferred with minimal quantities of corresponding training data. In sum, these results show that the AlphaFold2 architecture is capable of remarkable feats of generalization.

To better understand the behavior of class-stratified models, we analyzed the structures of two protein domains, one composed almost exclusively of α-helices (rice silicon channel Lsi1 aquaporin domain37) and another of β-sheets (human transmembrane p24 trafficking protein 1 (TMED1) domain38), as they are predicted by models trained on the mainly α or mainly β datasets. In the top row of Fig. 2c, we show an experimental structure (orange) for Lsi1 (PDB accession code 7CJS_B (ref. 37)) along with predictions made by the mainly α-trained model (yellow) and the mainly β-trained model (red). In the bottom row, we show similar images for TMED1 (PDB accession code 7RRM_C (ref. 38)). Predictably, the mainly α-trained model accurately predicts the α-helices of Lsi1 but fails to properly form β-sheets for TMED1 and incorrectly adopts a small α-helix in part of the structure. The mainly β-trained model has the opposite problem: its Lsi1 prediction contains poorly aligned helices and an erroneous β-sheet, but TMED1 is reasonably well predicted. Notably, however, neither fails catastrophically. Regions corresponding to the β-sheets of Lsi1 are predicted by the mainly α model with approximately the right shape, except that their atomic coordinates are not sufficiently precise to enable DSSP to classify them as β-sheets.

Because the topology ablations were evaluated on held-out topologies, the architecture ablations were evaluated on held-out architectures and so on, validation scores from different data elision experiments cannot be compared directly. For a more consistent picture of the relative final accuracies of each set of data elision experiments, we re-evaluate the final checkpoints of each model on our standard CAMEO validation set in Table 1. For information on how well the class-ablated models can predict secondary structure, see Extended Data Table 1 and, for a comparison of the effects of data elision on global structure as opposed to local structure, see Extended Data Fig. 5.

Table 1 ∣.

Data elision models evaluated on the CAMEO validation set

| Ablated CATH category | Training set | Mean CAMEO lDDT-Cα |

|---|---|---|

| Topology | 100% avail. T | 0.806 |

| 50% avail. T | 0.786 | |

| 10% avail. T | 0.678 | |

| 5% avail. T | 0.567 | |

| Architecture | 100% avail. A | 0.795 |

| 50% avail. A | 0.763 | |

| 10% avail. A | 0.627 | |

| 5% avail. A | 0.586 | |

| Class | Class 1 (‘mostly α’) | 0.689 |

| Class 2 (‘mostly β’) | 0.713 |

Rows correspond to CATH elisions reported in Fig. 2, except that evaluations reported here are based on the CAMEO validation set. Avail., available.

OpenFold’s surprising capacity for generalization across held-out regions of fold space suggests that it is somewhat indifferent to the diversity of the training set at the global fold level. Instead, the model appears to learn how to predict protein structures from local patterns of MSA and/or sequence–structure correlations (fragments, SSEs, individual residues and so on) rather than from global fold patterns captured by CATH. For extended analysis, see the Supplementary Discussion (section B.2).

OpenFold is more efficient than AlphaFold2 and trains stably

While the OpenFold model we used in the above experiments perfectly matches the computational logic of AlphaFold2, we have implemented a number of changes that minimally alter model characteristics but improve ease of use and performance when training new models and performing large-scale predictions.

First, we made several improvements to the data preprocessing and training procedure, including a low-precision (‘FP16’) training mode that facilitates model training on past generations of commercially available GPUs, like the widespread NVIDIA V100. Second, we introduced a change to the primary structural loss, FAPE (frame aligned point error), that enhances training stability. In the original model, FAPE is clamped, that is, limited to a fixed maximum value, in a large fraction of training batches. We find that, in the dynamic early phase of training, this strategy is too aggressive, limiting the number of batches with useful training signal and often preventing timely convergence. Rather than clamping entire batches in this fashion, we instead clamp the equivalent fraction of samples within each batch, ensuring that each batch contains at least some unclamped chains. In doing so, we are able to substantially improve training stability and speed up model convergence (Fig. 3a and the Supplementary Discussion (section 4.1.2)). Importantly, this change does not appear to affect the final accuracy of fully trained models; an OpenFold model trained to completion after the change reached 0.902 lDDT-Cα on our CAMEO validation set, which is almost identical to the score of our prior fully trained model checkpoint.

Fig. 3 ∣. Model improvements.

a, OpenFold trains more stably than AlphaFold2. lDDT-Cα and dRMSD-Cα (distance root mean squared deviation with respect to the alpha carbon) on the CAMEO validation set as a function of training step for five independent training runs with (orange) and without (blue) the new FAPE clamping protocol. Runs using the old protocol exhibit substantial instability with two rapidly converging runs, two late converging runs and one non-converging run. By contrast, all 15 independent runs using the new protocol converge rapidly. Runs using the new protocol also reach high accuracy faster. b, OpenFold is consistently three to four times faster than AlphaFold2 and can be run on longer sequences. Prediction runtimes in seconds on a single A100 NVIDIA GPU for OpenFold and AlphaFold2 with proteins of varying length.

Third, we made optimizations that improve memory efficiency during training, when model weights are continually updated to optimize model behavior for prediction, and during inference, when the model is used to make new predictions. In AlphaFold2, the computational characteristics of these two modes vary greatly. To save memory at training time, which requires storing intermediate computations during the optimization procedure, AlphaFold2 and OpenFold are evaluated on short protein fragments ranging in size from 256 to 384 residues. At inference time, intermediate computations need not be stored, but input sequences can be more than ten times longer than the longest fragments encountered during training. Because the model’s memory usage naively grows cubically with input length, inference time prediction stresses modules that are not necessarily bottlenecks at training time. To satisfy both sets of desiderata and enhance model efficiency, we implemented a number of training- and inference-specific optimizations. These optimizations create tradeoffs between memory consumption and speed that can be tuned differently for training and inference. They include advanced implementations of neural network attention mechanisms39 with favorable properties for unusually short and long sequences29,40, module refactoring for lower memory usage, optional approximations of certain computations that reduce the memory burden and specialized low-level code customized for GPU hardware. For technical details, see Training time optimizations and features and Inference.

In sum, these optimizations result in a substantially more efficient implementation than AlphaFold2. We report OpenFold runtimes in Fig. 3b. During inference, OpenFold is up to four times faster than AlphaFold2. OpenFold is more memory efficient than AlphaFold2 at inference time. Beyond 2,500 residues, AlphaFold2 crashes on single GPUs due to memory constraints. OpenFold runs successfully on longer proteins and complexes exceeding 4,000 residues in length. OpenFold training speed matches or improves upon that of AlphaFold2, as has been reported by other researchers using OpenFold41,42, and it can be trained on long crop sizes (up to 1,200 in the ‘initial training’ setting).

Learning of secondary structure is staggered and multi-scale

The preceding analysis suggests that SSEs are learned subsequent to tertiary structure. We next set out to formally confirm this observation and chronicle the order in which distinct SSEs are learned. For every protein in our validation set and every step of training, we used DSSP43 to identify residues matching the eight recognized SSE states. We treat as ground truth DSSP assignments of residues in the experimental structures and compute F1 scores as a combined metric of the recall and precision achieved by the model for every type of SSE at various training steps (Fig. 4a).

We observe a clear sequence in which SSEs are discovered: α-helices are learned first, followed by β-sheets, followed by less common SSEs. Unsurprisingly, this sequence roughly corresponds to the relative frequencies of SSEs in proteins (Fig. 4b), with the exception of uncommon helix variants. As was previously evident, the model’s discovery of SSEs lags that of accurate global structure. For instance, the F1 score for β-sheets (‘E’) only plateaus hundreds of steps after global structural accuracy, as measured by GDT-TS44, a similarity metric for tertiary protein structures. This is also clearly visible in our animations of progressive training predictions; for each protein, secondary structure is recognized and rendered properly only after global geometry is essentially finalized.

To investigate the possibility that OpenFold is achieving high α-helical F1 scores by gradually learning small fragmentary helices, we binned predicted helices by the longest contiguous fraction of the ground truth helix they recover and plotted the resulting histogram as a function of training step in Fig. 4c. Evidently, little probability mass ever accumulates between 0.0 (helices that are not recovered at all) and 1.0 (helices that are completely recovered). This suggests that, at least from the perspective of DSSP, most helices become correctly predicted essentially all at once. This sudden transition coincides with most of the improvement in helix DSSP F1 scores in the early phase of training.

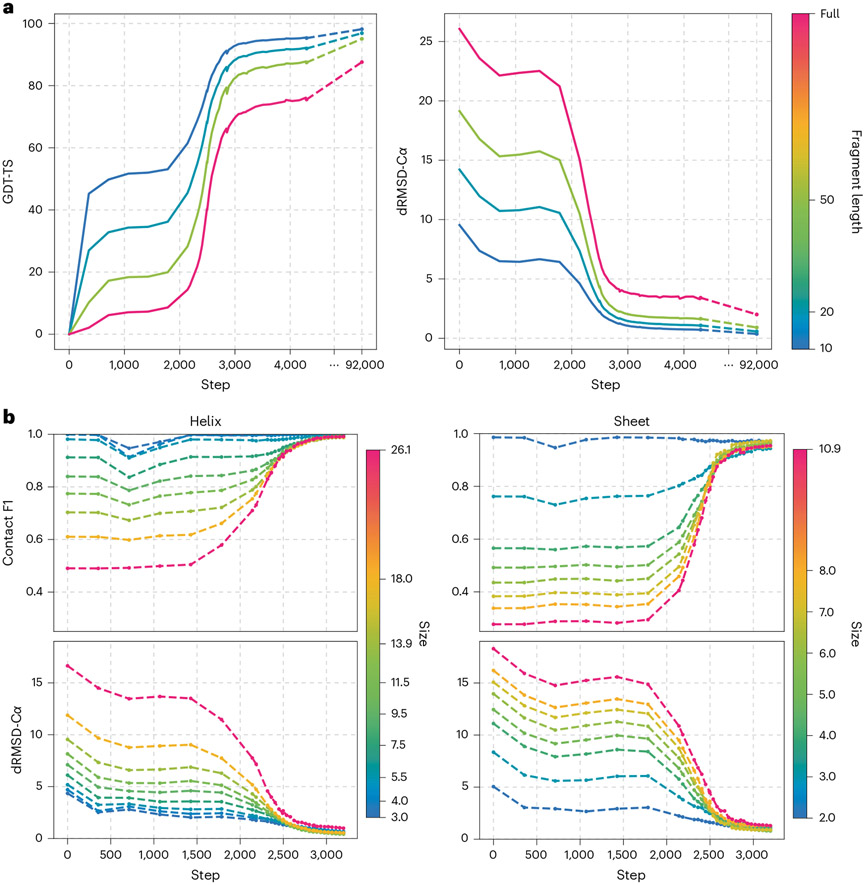

Based on the above observation, we reasoned that, as training progresses, OpenFold may first learn to predict smaller structural fragments before larger ones and that this may be evident on both the tertiary and secondary structure levels. Focusing first on tertiary structure, we assessed the prediction quality, at each training step, of all non-overlapping fragments 10, 20 and 50 residues long in our validation set. Average GDT-TS values are shown in Fig. 5a. Unlike global GDT-TS (pink), which improves minimally in the first 300–400 steps of training, fragment GDT-TS improves markedly during this phase, with shorter fragments showing larger gains. By step 1,000, when the model reaches a temporary plateau, it has learned to predict local structure far better than global structure (GDT-TS > 50 for ten-residue fragments versus GDT-TS < 10 for whole proteins). Soon after, at step 1,800, the accuracy of all fragment lengths including global structure begins to increase rapidly. However, the gains achieved by shorter fragments are smaller than those of longer fragments, such that the gap between ten-residue fragments and whole proteins is much smaller at step 3,000 than at step 1,800 (GDT-TS ≈ 90 for ten-residue fragments versus GDT-TS ≈ 70 for whole proteins). This trend continues until the model is fully trained, when the gap between ten-residue fragments and whole proteins shrinks to a mere ten GDT-TS points. Thus, while the model ultimately learns to predict global structure almost as well as local structure, it first learns to predict the latter.

Fig. 5 ∣. Learning proceeds at multiple scales.

a, Mean GDT-TS and dRMSD-Cα validation scores as a function of training step for non-overlapping protein fragments of varying lengths (color bars indicate fragment length). b, Average contact F1 score (threshold of 8 Å) and dRMSD for predicted α-helices and β-sheets of varying lengths and number of strands, respectively, as a function of training step. Color bars indicate the weighted average of the lengths and widths of helices and sheets in each bin, respectively.

Turning to secondary structure, we investigated whether the same multi-scale learning behavior is detectable when examining SSEs. As before, we treat as ground truth the DSSP classifications of experimental structures in our validation set, focusing exclusively on α-helices and β-sheets. We bin both SSEs according to size, defined as the number of residues for α-helices and the number of strands for β-sheets. As uniform binnings would result in highly imbalanced bins, we instead opt for a dynamic binning procedure. First, each SSE is assigned to a (potentially imbalanced) bin that corresponds to its size. Bins are then iteratively merged with adjacent bins, subject to the condition that no bin exceed a maximum size (in this case, 200 for helices and 30 for sheets), until no further merges can occur. Finally, bins below a minimum bin size (20 for both) are unconditionally merged with adjacent bins. We compute metrics averaged over each bin independently (Fig. 5b). In Extended Data Fig. 8, we provide another view of the sheet data in Fig. 5b by distinguishing between small- (6 Å), medium- (12 Å) and long- (24 Å) range contacts, as in, for example, ref. 8

Analogous to what we observe for tertiary structure (see Extended Data Figs. 6 and 7 for details), short helices and narrow sheets are better predicted during earlier phases of training than their longer and wider counterparts, respectively. Improvement in SSE accuracy coincides with the rapid increase in tertiary structure accuracy, albeit shifted, as we observed in Fig. 4a. Notably, the final quality of predicted SSEs is essentially independent of length and width despite the initially large spread in prediction accuracies, suggesting that OpenFold ultimately becomes independent of scale in its predictive capacity, at least for secondary structure. We note that the identification of SSEs is performed by DSSP, which is sensitive to the details of their hydrogen bonding networks. It is possible that, in earlier phases of training, OpenFold has already recovered aspects of secondary structure not recognized by DSSP on account of imprecise atom positioning.

Discussion

We have developed OpenFold, a complete open-source reimplementation of AlphaFold2 that includes training code and data. By training OpenFold from scratch and matching the accuracy of AlphaFold2, we have demonstrated the reproducibility of the AlphaFold2 model for protein structure prediction. Furthermore, the OpenFold implementation introduces technical advances over AlphaFold2, including markedly faster prediction speed. It is built using PyTorch, the most widely used deep learning framework, facilitating incorporation of OpenFold components in future machine learning models.

OpenFold immediately makes possible two broad areas of advances: (1) deeper analyses of the strengths, weaknesses and learning behavior of AlphaFold2-like models and (2) development of new (bio)molecular models that take advantage of AlphaFold2 modules. In this work, we have focused on the former. First, we assessed OpenFold’s capacity to learn from training sets substantially reduced in size. Remarkably, we found that even a 100-fold reduction in dataset size (0.76% models in Fig. 2a) results in models more performant than the first version of AlphaFold. Stated differently, the architectural advances introduced in AlphaFold2 enable it to be 100× more data efficient than its predecessor, which at the time of its introduction set a new state of the art. These results demonstrate that architectural innovations can have a more profound impact on model accuracy than larger datasets, particularly in domains where data acquisition is costly or time consuming, as is often the case in (bio)molecular systems. However, it merits noting that AlphaFold2 in general learns MSA–structure, not sequence–structure, relationships. MSAs implicitly encode a substantial amount of structural knowledge, as evidenced by early coevolution-based structure prediction methods that were entirely unsupervised, making no use of experimental structural data45,46. Hence, the applicability of the AlphaFold2 architecture to problems that do not exhibit a coevolutionary signal remains undemonstrated.

Our data elision results can be interpreted in light of recent work on large transformer-based language models that has revealed broadly applicable ‘scaling laws’ that predict model accuracy as a simple function of model size, compute used and training set size47,48. When not constrained by any one of these three pillars, models benefit from investments into the other two. These observations have largely focused on transformer-based architectures, of which AlphaFold2 is an example, but more recent work has revealed similar behavior for other architectures49. Although determining the precise scaling properties of AlphaFold2 is beyond the scope of the present study, our results suggest that it is hardly constrained by the size or diversity of the PDB, motivating potential development of larger instantiations of its architecture.

OpenFold lays the groundwork for future efforts aimed at improving the AlphaFold2 architecture and repurposing it for new molecular modeling problems. Since the release of our codebase, there have been multiple efforts that either depend on OpenFold or directly build upon and extend it. These include the ESMFold method for protein structure prediction50, which replaces MSAs with protein language models51-53, and FastFold, a community effort that has implemented substantial improvements including fast model-parallel training and inference41. We expect future work to go further by disassembling OpenFold to attack problems beyond protein structure prediction. For instance, the evoformer module is a general-purpose primitive for reasoning over evolutionarily related sequences. DNA and RNA sequences also exhibit a coevolutionary signal, with efforts aimed at predicting RNA structure from MSAs fast materializing (for example, refs. 54-56). It is plausible that even more basic questions in evolutionary biology, such as phylogenetic inference, may prove amenable to evoformer-like architectures. Similarly, AlphaFold2’s structure module and in particular the invariant point attention mechanism provide a general-purpose approach for spatial reasoning over polymers, one that may be further extendable to arbitrary molecules. We anticipate that, as protein structures and other biomolecules shift from being an output to be predicted to an input to be used, downstream tasks that rely on spatial reasoning capabilities will become increasingly important (for example, refs. 57,58). We hope that OpenFold will play a key role in facilitating these developments.

Methods

Our code and data are fully available at https://github.com/aqlaboratory/openfold and https://registry.opendata.aws/openfold/, respectively. In this section, we provide some additional details that may be of interest to those attempting to reproduce our results.

Differences between OpenFold and AlphaFold2

In this section, we describe additions and improvements we made to OpenFold subject to the constraint that the weights of the two models should be interchangeable. We also describe our design decisions in the handful of instances for which the AlphaFold2 paper was ambiguous.

Changes to the data pipeline.

Template trick.

During AlphaFold2 training, structural template hits undergo two successive rounds of filtering. Between these two rounds, the dataloader parses the template structure data. The top 20 template hits to pass both filters are shuffled uniformly at random. Finally, the dataloader samples a number of templates uniformly at random in the range [0, 4] and draws that many samples from the shuffled pool of valid hits. These are then passed as inputs to the model. This subsampling process is intended to lower the average quality of templates seen by the model during training. We note that pre-emptively parsing structure files for each template hit during the filtering process is an expensive operation and, for proteins with many hits, considerably slows training. For this reason, we replace the original algorithm with an approximation. Instead of sampling hits from the top 20 template candidates from the pool of templates that pass both sets of filters, we use the top 20 hits to pass the first filter. These are then shuffled and subsampled as before. Only when a hit is drawn is it passed through the second filter; hits that fail to pass the second filter at this point are discarded and replaced. If not enough hits in the initial 20-sample pool pass the second filter, we continue drawing candidates from the top hits outside that pool, without further shuffling. This procedure has the disadvantage that, if too many hits pass the first filter but not the second filter, the hits used for the model are not shuffled. Even in instances where only x of the initial hits fail to pass the second filter, OpenFold effectively only shuffles the top (20 – x) proteins to pass both filters, strictly increasing the expected quality of template hits relative to those used by AlphaFold2. However, in most cases, this approximation allows the dataloader to parse only as many structure files as are needed, speeding up the process by a factor of at least five. In practice, the vast majority of invalid template hits are successfully detected by the first filter, suggesting that the difference in final template quality between the two procedures is marginal.

Self-distillation training setfiltering.

The set of 270,262 MSAs yielded by our self-distillation procedure is smaller than the 355,993 MSAs reported by DeepMind, despite having started with the same database. We suspect that the discrepancy arises due to the first step of the filtering process, of which the description in the AlphaFold2 paper is somewhat ambiguous.

Zero-centering target structures.

We find that centering target structures at the origin slightly improves the numerical stability of the model, especially during low-precision training.

Plateaus and phase transitions.

During training of the original version of OpenFold, we and third-party developers observed two distinct training behaviors. The large majority of training runs are almost identical to the training curves shown in Fig. 1; after a few thousand training steps, validation lDDT-Cα rapidly increases to ~0.83 and improves only incrementally thereafter. Occasionally, such runs exhibit a ‘double descent’, briefly improving and then degrading in accuracy before finally converging in the same way. In a fraction of training runs, however, lDDT-Cα plateaus between 0.30 and 0.35 on the same set (Fig. 3a). Anecdotally, these values appear to be consistent across environments, OpenFold versions, architectural modifications and users. If the runs are allowed to continue long past the point where lDDT-Cα would otherwise have stopped improving (>10,000 training steps), they eventually undergo a phase transition, suddenly exceeding 0.8 lDDT-Cα and then continuing to improve much as normal runs do. We have not been able to determine whether this phenomenon is the result of an error in the OpenFold codebase or whether it is a property of the AlphaFold2 algorithm.

Since running the experiments described in the main text of this paper, we have discovered a workaround that deviates slightly from the original AlphaFold2 training procedure but that appears to completely resolve early training instabilities. In the original training configuration, for each AlphaFold2 batch, backbone FAPE loss, the model’s primary structural loss, is clamped for all samples in the batch with probability 0.9. This practice is potentially problematic during the volatile early phase of training, when FAPE values can be extremely large and frequent clamping zeroes gradients for most of the residues in each crop. We find that clamping each sample independently, that is, clamping approximately 90% of the samples in each batch rather than clamping 90% of all batches, eliminates training instability and speeds up convergence to high accuracy by about 30%. We show before-and-after data in Fig. 3a.

Training details

Our main OpenFold model was trained using the abridged training schedule outlined in the AlphaFold2 Supplementary Materials of ref. 11 rather than the original training schedule in ref. 11. Specifically, it was trained for three rounds: the initial training phase, the fine-tuning phase and the predicted TM60 fine-tuning stage. During the initial training phase, sequences were cropped to 256 residues, MSA depth was capped at 128 and extra MSA depth was capped at 1,024. During fine-tuning, these values were increased to 384, 512 and 5,120, respectively. The second phase also introduced the ‘violation’ and ‘experimentally resolved’ losses, which respectively penalize nonphysical steric clashes and incorrect predictions of whether atomic coordinates are resolved in experimental structures. Next, we ran a short third phase with the predicted TM score loss enabled. The three phases were run for 10 million, 1.5 million and 0.5 million protein samples, respectively. We trained the model with PyTorch version 1.10, DeepSpeed26 version 0.5.10 and stage 2 of the ZeRO redundancy optimizer61. We used Adam62 with β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.99 and ϵ = 10−6. We warmed up the learning rate linearly over the first 1,000 iterations from 0 to 10−3. After approximately 7 million samples, we marginally decreased the learning rate to 9.5 × 10−4. This decrease had no noticeable effect on model training. For the latter two phases, the learning rate was halved to 5 × 10−4. All model, data and loss-related hyperparameters were identical to those used during AlphaFold2 training. We also replicated all of the stochastic training time dataset augmentation, filtering and resampling procedures described in the original paper.

During the initial fine-tuning and subsequent predicted TM fine-tuning phases, we manually sampled checkpoints at peaks in the validation lDDT-Cα33. These checkpoints were added to the pool of model checkpoints used in the final model ensemble.

Training was run on a cluster of 44 NVIDIA A100 GPUs, each with 40 GB of DRAM. The model was trained in a data-parallel fashion, with one protein per GPU. To simulate as closely as possible the batch size of 128 used in training AlphaFold2, we performed three-way gradient accumulation to raise our effective batch size from 44 to 132.

As in the original paper, CAMEO chains longer than 700 residues were removed from the validation set.

Inference details

Runtime benchmarks were performed on a single 40-GB A100 GPU. Times correspond to the intensive ‘model_1_ptm’ config preset, which uses deep MSAs and the maximum number of templates. AlphaFold was run with JAX version 0.3.13.

Additional model optimizations and features

Training time optimizations and features.

Despite its relatively small parameter count (~93 million), AlphaFold2 manifests very large intermediate activations during training, resulting in peak memory usage, along with floating point operation counts, much greater than that of state-of-the-art transformer-based models from other domains63. In AlphaFold2, peak memory usage during training grows cubically as a function of input sequence length. As a result, during the second phase of training when the inputs are longest, the model manifests individual tensors as large as 12 GB. Intermediate activation tensors stored for the backward pass are even larger. This bottleneck is exacerbated by several limitations of the PyTorch framework. First, PyTorch is run eagerly and does not benefit from the efficient compiler used by JAX models that improves runtime and reduces memory usage. Second, even on GPUs that in principle have sufficient memory to store all intermediate tensors used during the forward pass, suboptimal allocation patterns frequently result in memory fragmentation, preventing the model from using all available memory. For this reason, among others, a preliminary version of OpenFold naively modeled after the official JAX-based implementation frequently ran out of memory despite having allocated as little as 40% of total available memory. To amelioriate these problems, we introduced several features that reduce peak memory consumption during training.

In-place operations.

We refactored the model by replacing element-wise tensor operations with in-place equivalents wherever possible to prevent unnecessary allocation of large intermediate tensors.

Custom CUDA kernels.

We implemented custom CUDA kernels for all the attention modules in the network based on FlashAttention29 but with support for the bias terms required by the attention variants in the AlphaFold2 architecture. Prior versions of OpenFold relied on a custom implementation of the model’s ‘MSA row attention’ module, the multi-head attention operation where the aforementioned 12-GB tensor is allocated. Modified from optimized softmax kernels from FastFold41, which are in turn derived from OneFlow kernels64, our kernels operate entirely in place. This is made possible partly by a fusion of the backward passes of the softmax operation and the succeeding matrix multiplication. Overall, only a single copy of the quadratic attention logit tensor is allocated, resulting in peak memory usage five and four times lower than that of equivalent native PyTorch code and the original FastFold kernels, respectively.

DeepSpeed.

OpenFold is trained using DeepSpeed. Using its ZeRO redundancy optimizer61 in the ‘stage 2’ configuration, the model partitions gradients and optimizer states between GPUs during data-parallel training, further reducing peak memory usage.

Half-precision training.

By default, as a memory-saving measure, AlphaFold2 is trained using bfloat16 floating point precision. This 16-bit format trades the large precision of the classic half-precision format (FP16) for the complete numerical range of full-precision floats (FP32), making it well suited for training deep neural networks of the type used by AlphaFold2, which is not compatible with FP16 training by default. However, unlike FP16, bfloat16 hardware support is still limited to relatively recent NVIDIA GPUs (Ampere and Hopper architectures), and so the format remains out of reach for academic laboratories with access to older GPUs that are otherwise capable of training AlphaFold2 models (for example, V100 GPUs). We address this problem by implementing a stable FP16 training mode with more careful typecasting throughout the model pipeline, making OpenFold training broadly accessible.

Inference.

We also introduce several inference time optimizations to OpenFold. As previously mentioned, these features trade off memory usage for runtime, contributing to more versatile inference on chains of diverse lengths.

FlashAttention.

We incorporate FlashAttention29, an efficient fused attention implementation that tiles computation to reduce data movement between different levels of GPU memory, greatly improving peak memory usage and runtime in the process. We find it to be particularly effective for short sequences with 1,000 residues or less, on which it contributes to an OpenFold speedup of up to 15% despite only being compatible with a small number of the attention modules in the network.

Low-memory attention.

Separately, OpenFold makes use of a recent attention algorithm that uses a novel chunking technique to perform the entire operation in constant space40. Although enabling this feature marginally slows down the model, it nullifies attention as a memory bottleneck during inference.

Refactored triangle multiplicative attention.

A naive implementation of the triangle multiplicative update manifests five concurrent tensors the size of the input pair representation. These pair representations grow quadratically with input length, such that, during inference on long sequences or complexes, they become the key bottleneck. We refactored the operation to reduce its peak memory usage by 50%, requiring only 2.5 copies of the pair representation.

Template averaging.

AlphaFold2 and OpenFold create separate pair embeddings for each structural template passed to each model and then reduce them to a single embedding at the end of the template pipeline with an attention module. For very long sequences or very many templates, this operation can become a memory bottleneck. AlphaFold-Multimer22 avoids this problem by computing a running average of template pair embeddings. Although we trained OpenFold using the original AlphaFold2 (nonmultimer) procedure, we find that the newer approach can be adopted during inference without a noticeable decrease in accuracy. We thus make it available as an optional inference time memory-saving optimization.

In-place operations.

Without the requirement to store intermediate activations for the backward pass, OpenFold is able to make more extensive use of in-place operations during inference. We also actively remove unused tensors to mitigate crashes caused by memory fragmentation.

Chunk size tuning.

AlphaFold2 offsets extreme inference time memory costs with a technique called ‘chunking’, which splits input tensors into ‘chunks’ along designated, module-specific sub-batch dimensions and then runs those modules sequentially on each chunk. For AlphaFold2, the chunk size used in this procedure is a model-wide hyperparameter that is manually tuned. OpenFold, on the other hand, dynamically adjusts chunk size values for each module independently, taking into account the model’s configuration and the current memory limitations of the system. Although the profiling runs introduced by this process incur a small computational overhead, the modules do not need to be recompiled for each run, unlike their AlphaFold2 equivalents, and said profiling runs are only necessary the first time the model is run; once computed, the optimal chunk sizes are cached and reused until conditions change. We find this to be a robust way to seamlessly improve runtimes in a variety of settings.

Tensor offloading.

Optionally, OpenFold can aggressively offload intermediate tensors to CPU memory, temporarily freeing additional GPU memory for memory-intensive computations at the cost of a considerable slowdown. This feature is useful during inference on extremely long sequences that would otherwise not be computable.

TorchScript tracing.

Specially written PyTorch programs can be converted to TorchScript, a JIT-compiled variant of PyTorch. We use this feature during inference to speed up parts of the evoformer module. Although TorchScript tracing and compilation do introduce some overhead at the beginning of model inference and lock the model to a particular sequence length, similar to JAX compilation, we find that using TorchScript achieves overall speedups of up to 15%, especially on sequences shorter than 1,000 residues. This feature is particularly useful during batch inference, where sequences are grouped by length to avoid repeated recompilations and to take maximal advantage of faster inference times.

AlphaFold-Gap implementation.

OpenFold currently supports multimeric inference using AlphaFold-Gap13, a zero-shot hack that allows inference on protein complexes using monomeric weights. Although it falls short of the accuracy of AlphaFold-Multimer (for a comparison of the two techniques, see ref. 22), it is a capable tool, especially for homomultimers. Because complexes manifest in the model as long sequences, OpenFold-Gap in particular benefits from the memory optimizations discussed earlier.

Known issues during training

During and after the primary OpenFold retraining experiment, we discovered a handful of minor implementation errors that, given the prohibitive cost of retraining a full model from scratch, could not be corrected. In this section, we describe these errata and the measures that we have taken to mitigate them.

Distillation template error.

As described in the main text, OpenFold and AlphaFold2 training consists of three phases, of which the first is the longest and most determinative of final model accuracy. During this first phase of the main OpenFold training run, a bug in the dataloader caused distillation templates to be filtered entirely; OpenFold was only presented with templates for PDB chains, which constitute ~25% of training samples, and not self-distillation set chains. The issue was corrected for later phases, which were run slightly longer than usual to compensate.

Although the accuracy of the resulting OpenFold model matches that of the original AlphaFold2 in holistic evaluations, certain downstream tasks that specifically exploit the template stack65 do not perform as well as the original AlphaFold2. There is evidence, for instance, that OpenFold disregards the amino acid sequence of input templates. After the bug was corrected, follow-up experiments involving shorter training runs showed template usage behavior at parity with that of AlphaFold2. Furthermore, OpenFold can be run with the original AlphaFold2 weights in cases where templates are expected to be important to take advantage of the new inference characteristics without diminution of template-related performance.

Gradient clipping.

OpenFold, unlike AlphaFold2, was trained using per-batch as opposed to per-sample gradient clipping (first noted by the Uni-Fold team42). Uni-Fold experiments show that models trained using the latter clipping technique achieve slightly better accuracy.

Training instability.

Our primary training run was performed before we introduced the changes described in Plateaus and phase transitions. While we have no reason to believe that the instabilities we observed there are a result of a bug in the OpenFold codebase, as opposed to an inherent limitation of the AlphaFold2 architecture, the former remains a possibility. It is unclear how potential issues of this kind may have affected runs that, like our primary training run, appeared to converge at the expected rate.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 ∣. OpenFold matches the accuracy of AlphaFold2 on CASP15 targets.

Scatter plot of GDT-TS values of AlphaFold and OpenFold ‘Model 1’ predictions against all currently available ‘all groups’ CASP15 domains (n = 90). OpenFold’s mean accuracy (95% confidence interval = 68.6-78.8) is on par with AlphaFold’s (95% confidence interval = 69.7-79.2) and OpenFold does at least as well as the latter on exactly 50% of targets. Confidence intervals of each mean are estimated from 10,000 bootstrap samples.

Extended Data Fig. 2 ∣. OpenFold learns decoy ranking slowly.

Decoy ranking results (mean Spearman correlation between pLDDT and decoy TM Score) using intermediate checkpoints of OpenFold on 28 randomly chosen proteins from the Rosetta decoy ranking dataset from15. See Supplementary Information section B.1 for more details.

Extended Data Fig. 3 ∣. Fine-tuning does not materially improve prediction accuracy on long proteins.

Mean lDDT-Cα over validation proteins with at least 500 residues as a function of fine-tuning step.

Extended Data Fig. 4 ∣. The ‘Mostly alpha’ CATH class contains some beta sheets, and vice versa.

Counts for alpha helices and beta sheets in the mostly alpha and mostly beta CATH class-stratified training sets from Fig. 2, based on 1,000 random samples. Counts are binned by size, defined as the number of residues for alpha helices and number of strands for beta sheets.

Extended Data Fig. 5 ∣. Reduced dataset diversity disproportionately affects global structure.

Mean GDT-TS and lDDT-Cα of non-overlapping protein fragments from CAMEO validation set as a function of the percentage of CATH clusters in elided training sets. Data for both topology and architecture elisions are included. The fragmenting procedure is the same as that described in Fig. 5a.

Extended Data Fig. 6 ∣. Early predictions crudely approximate lower-dimensional PCA projections.

(A) Mean dRMSD, as a function of training step, between low- dimensional PCA projections of predicted structures and the final 3D prediction at step 5,000 (denoted by *). Averages are computed over the CAMEO validation set. Insets show idealized behavior corresponding to unstaggered, simultaneous growth in all dimensions and perfectly staggered growth. Empirical training behavior more closely resembles the staggered scenario. (B) Low-dimensional projections as in (A) compared to projections of the final predicted structures at step 5,000. (C) Mean displacement, as a function of training step, of C? atoms along the directions of their final structure’s PCA eigenvectors. Results are shown for two individual proteins (PDB accession codes 7DQ9_A ref. 66 and 7RDT_A ref. 67). Shaded regions correspond loosely to ‘1D,’ ‘2D,’ and ‘3D’ phases of dimensionality.

Extended Data Fig. 7 ∣. Radius of gyration as an order parameter for learning protein phase structure.

Radii of gyration for proteins in the CAMEO validation set (or- ange) as a function of sequence length over training time, plotted on a log-log scale against experimental structures (blue). Legends show equations of best fit curves, computed using non-linear least squares. The training steps chosen correspond loosely to four phases of dimensional growth. See Supplementary Information section B.3 for extended discussion.

Extended Data Fig. 8 ∣. Contact prediction for beta sheets at different ranges.

Binned contact F1 scores (8 Å threshold) for beta sheets of various widths as a function of training step at different residue-residue separation ranges (SMLR ≥ 6 residues apart; LR ≥ 24 residues apart, as in8). Sheet widths are weighted averages of sheet thread counts within each bin, as in Fig. 5b.

Extended Data Table 1 ∣.

Secondary structure recovery by class-stratified models

| Model | Reduced S.S. | Recall | F1 score |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Mostly alpha” | Helix | 0.894 | 0.800 |

| Strand | 0.737 | 0.766 | |

| Coil | 0.507 | 0.801 | |

| “Mostly beta” | Helix | 0.843 | 0.824 |

| Strand | 0.887 | 0.856 | |

| Coil | 0.515 | 0.823 |

Recall and F1 scores for reduced secondary structure categories derived using DSSP. Results are shown for the two class-stratified models from the final panel of Fig. 2b, here evaluated on the CAMEO validation set. We use the reduced secondary state scheme described in Supplementary Information section B.5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Flatiron Institute, OpenBioML, Stability AI, the Texas Advanced Computing Center and NVIDIA for providing compute for experiments in this paper. Individually, we thank M. Mirdita, M. Steinegger and S. Ovchinnikov for valuable support and expertise. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. We acknowledge the Texas Advanced Computing Center at the University of Texas at Austin for providing HPC resources that have contributed to the research results reported within this paper. G.A. is supported by a Simons Investigator Fellowship, NSF grant DMS-2134157, DARPA grant W911NF2010021, DOE grant DE-SC0022199 and a graduate fellowship from the Kempner Institute at Harvard University. N.B. is supported by DARPA Panacea program grant HR0011-19-2-0022 and NCI grant U54-CA225088. C.F. and S.K. are supported by NIH grant R35GM150546. B.Z. and Z.Z. are supported by grants NSF OAC-2112606 and OAC-2106661. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Competing interests

M.A. is a member of the scientific advisory boards of Cyrus Biotechnology, Deep Forest Sciences, Nabla Bio, Oracle Therapeutics and FL2021-002, a Foresite Labs company. P.K.S. is a cofounder and member of the BOD of Glencoe Software, member of the BOD for Applied BioMath and a member of the SAB for RareCyte, NanoString, Reverb Therapeutics and Montai Health; he holds equity in Glencoe, Applied BioMath and RareCyte. L.N. is an employee of Cyrus Biotechnology. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02272-z.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02272-z.

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02272-z.

Data availability

OpenProteinSet and OpenFold model parameters are hosted on the Registry of Open Data on AWS and can be accessed at https://registry.opendata.aws/openfold/. Both are available under the permissive CC BY 4.0 license. Throughout the study, we use validation sets derived from the PDB via CAMEO. We also use CASP evaluation sets. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

OpenFold can be accessed at https://github.com/aqlaboratory/openfold. It is available under the permissive Apache 2 Licence.

References

- 1.Anfinsen CB Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 181, 223–230 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dill KA, Ozkan SB, Shell MS & Weikl TR The protein folding problem. Annu. Rev. Biophys 37, 289–316 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones DT, Singh T, Kosciolek T & Tetchner S MetaPSICOV: combining coevolution methods for accurate prediction of contacts and long range hydrogen bonding in proteins. Bioinformatics 31, 999–1006 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golkov V et al. Protein contact prediction from amino acid co-evolution using convolutional networks for graph-valued images. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Lee D et al. ) (Curran Associates, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Sun S, Li Z, Zhang R & Xu J Accurate de novo prediction of protein contact map by ultra-deep learning model. PLoS Comput. Biol 13, e1005324 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Palmedo P, Ye Q, Berger B & Peng J Enhancing evolutionary couplings with deep convolutional neural networks. Cell Syst. 6, 65–74 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senior AW et al. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 577, 706–710 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J, McPartlon M & Li J Improved protein structure prediction by deep learning irrespective of co-evolution information. Nat. Mach. Intell 3, 601–609 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Šali A & Blundell TL Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol 234, 779–815 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy A, Kucukural A & Zhang Y I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Protoc 5, 725–738 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jumper J et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 577, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirdita M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baek M. Adding a big enough number for ‘residue_index’ feature is enough to model hetero-complex using AlphaFold (green&cyan: crystal structure / magenta: predicted model w/ residue_index modification). Twitter twitter.com/minkbaek/status/1417538291709071362?lang=en (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsaban T. et al. Harnessing protein folding neural networks for peptide–protein docking. Nat. Commun 13, 176 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roney JP & Ovchinnikov S State-of-the-art estimation of protein model accuracy using AlphaFold. Phys. Rev. Lett 129, 238101 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baltzis A. et al. Highly significant improvement of protein sequence alignments with AlphaFold2. Bioinformatics 38, 5007–5011 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant P, Pozzati G & Elofsson A Improved prediction of protein–protein interactions using AlphaFold2. Nat. Commun 13, 1265 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wayment-Steele HK, Ovchinnikov S, Colwell L & Kern D Prediction of multiple conformational states by combining sequence clustering with AlphaFold2. Nature 625, 832–839 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tunyasuvunakool K. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature 596, 590–596 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varadi M. et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D439–D444 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callaway E. ‘The entire protein universe’: AI predicts shape of nearly every known protein. Nature 608, 15–16 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans R. et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.10.04.463034 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahdritz G. et al. OpenProteinSet: training data for structural biology at scale. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Oh A et al. ) 4597–4609 (Curran Associates, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paszke A. et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Wallach H et al. ) 8026–8037 (Curran Associates, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradbury J. et al. JAX: composable transformations of Python+NumPy programs. GitHub github.com/google/jax (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasley J, Rajbhandari S, Ruwase O & He Y DeepSpeed: system optimizations enable training deep learning models with over 100 billion parameters. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, KDD ’20 3505–3506 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charlier B, Feydy J, Glaunès J, Collin F-D & Durif G Kernel operations on the GPU, with autodiff, without memory overflows. J. Mach. Learn. Res 22, 1–6 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falcon W. & the PyTorch Lightning team. PyTorch Lightning (PyTorch Lightning, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dao T, Fu DY, Ermon S, Rudra A & Ré C FlashAttention: fast and memory-efficient exact attention with IO-awareness. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Koyejo S et al. ) 16344–16359 (Curran Associates, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirdita M. et al. Uniclust databases of clustered and deeply annotated protein sequences and alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D170–D176 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.wwPDB Consortium. Protein Data Bank: the single global archive for 3D macromolecular structure data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D520–D528 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haas J. ürgen et al. Continuous automated model evaluation (CAMEO) complementing the critical assessment of structure prediction in CASP12. Proteins 86, 387–398 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mariani V, Biasini M, Barbato A & Schwede T lDDT: a local superposition-free score for comparing protein structures and models using distance difference tests. Bioinformatics 29, 2722–2728 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orengo CA et al. CATH—a hierarchic classification of protein domain structures. Structure 5, 1093–1108 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sillitoe I. et al. CATH: increased structural coverage of functional space. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D266–D273 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andreeva A, Kulesha E, Gough J & Murzin AG The SCOP database in 2020: expanded classification of representative family and superfamily domains of known protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D376–D382 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saitoh Y. et al. Structural basis for high selectivity of a rice silicon channel Lsi1. Nat. Commun 12, 6236 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mota DaniellyC. A. M. et al. Structural and thermodynamic analyses of human TMED1 (p241) Golgi dynamics. Biochimie 192, 72–82 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaswani A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Guyon I et al. ) (Curran Associates, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabe MN & Staats C Self-attention does not need O(n2) memory. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2112.05682 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng S. et al. FastFold: Optimizing AlphaFold Training and Inference on GPU Clusters. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGPLAN Annual Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming 417–430 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2024). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Z. et al. Uni-Fold: an open-source platform for developing protein folding models beyond AlphaFold. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.08.04.502811 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kabsch W & Sander C Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Science 22, 2577–2637 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zemla A. LGA: a method for finding 3D similarities in protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3370–3374 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marks DS et al. Protein 3D structure computed from evolutionary sequence variation. PLoS ONE 6, e28766 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sułkowska JI, Morcos F, Weigt M, Hwa T & Onuchic, José Genomics-aided structure prediction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10340–10345 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan J. et al. Scaling laws for neural language models. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2001.08361 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffmann J. et al. An empirical analysis of compute-optimal large language model training. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Oh AH et al. ) 30016–30030 (NeurIPS, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tay Y. et al. Scaling laws vs model architectures: how does inductive bias influence scaling? In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023 (eds Bouamor H et al. ) 12342–12364 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin Z. et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 379, 1123–1130 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alley EC, Khimulya G, Biswas S, AlQuraishi M & Church GM Unified rational protein engineering with sequence-based deep representation learning. Nat. Methods 16, 1315–1322 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chowdhury R. et al. Single-sequence protein structure prediction using a language model and deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1617–1623 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu R. et al. High-resolution de novo structure prediction from primary sequence. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.07.21.500999 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh J, Paliwal K, Litfin T, Singh J & Zhou Y Predicting RNA distance-based contact maps by integrated deep learning on physics-inferred secondary structure and evolutionary-derived mutational coupling. Bioinformatics 38, 3900–3910 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baek M, McHugh R, Anishchenko I, Baker D & DiMaio F Accurate prediction of protein–nucleic acid complexes using RoseTTAFoldNA. Nat. Methods 21, 117–121 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pearce R, Omenn GS & Zhang Y De novo RNA tertiary structure prediction at atomic resolution using geometric potentials from deep learning. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.05.15.491755 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McPartlon M, Lai B & Xu J A deep SE(3)-equivariant model for learning inverse protein folding. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.04.15.488492 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McPartlon M & Xu J An end-to-end deep learning method for protein side-chain packing and inverse folding. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences e2216438120 (PNAS, 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knox HL, Sinner EK, Townsend CA, Boal AK & Booker SJ Structure of a B12-dependent radical SAM enzyme in carbapenem biosynthesis. Nature 602, 343–348 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y & Skolnick J Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality. Proteins 57, 702–710 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajbhandari S, Rasley J, Ruwase O & He Y Zero: memory optimizations toward training trillion parameter models. In Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis (IEEE Press, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kingma DP & Ba J Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (eds Bengio Y & LeCun Y) (ICLR, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang G. et al. HelixFold: an efficient implementation of AlphaFold2 using PaddlePaddle. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2207.05477 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan J. et al. OneFlow: redesign the distributed deep learning framework from scratch. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2110.15032 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]