Abstract

Heterobifunctional protein degraders constitute a novel therapeutic modality that harnesses the cell’s natural protein degradation machinery, that is, the ubiquitin–proteasome system, to selectively target proteins involved in disease pathogenesis for elimination. Protein degraders have several potential advantages over small-molecule inhibitors (which have traditionally been used for cancer treatment), including their event-driven (rather than occupancy-driven) pharmacology permitting sub-stoichiometric drug concentrations for activity, their capacity to act iteratively and target multiple copies of a protein of interest, and their potential to target nonenzymatic proteins that were previously considered ‘undruggable’. Following numerous innovations in protein degrader design and rigorous evaluation in preclinical models, protein degraders entered clinical testing in 2019. Currently, 18 protein degraders are in phase I or phase I/II clinical trials involving patients with various tumour types, with a phase III trial of one initiated in 2022. The first safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetic data from these studies are now materializing and, although considerably more evidence is needed, protein degraders are showing promising activity as cancer therapies. Herein, we review advances in protein degrader development, the preclinical research that supported their entry into clinical studies, the available data for protein degraders in patients, and future directions for this new class of drugs.

ToC Blurb

Protein degraders constitute a new class of agents that eliminate, rather than just inhibit, their target proteins. These novel agents have recently entered testing in oncology trials, with initial data providing clinical proof-of-concept for the mechanism of action as well as the antitumour activity of protein degraders. In this Review, the authors outline the progress of protein degrader development for the treatment of cancer and consider prospects and potential challenges for these agents.

Introduction

Prior to the turn of the 21st century, the mainstays of treatment for patients with cancer were chemotherapy, radiation and surgery. While all three modalities remain pillars of cancer therapeutics, cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy have well recognized limitations due to toxicities, morbidities and significant long-term side effects due to the non-specific targeting of both healthy and cancerous cells. The discovery of small-molecule inhibitors that target the active sites of specific proteins involved in the pathogenesis of cancer and leave noncancerous cells largely untouched ushered in a new era of precision medicine. Imatinib, a small-molecule inhibitor of the constitutively active BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase fusion protein, which is the hallmark of chronic myeloid leukaemia, was the first of these agents to be approved by the FDA in 20011. Since then, scores of small-molecule inhibitors have been approved by the FDA and globally as treatments for solid tumours and haematological cancers2–3.

Despite the promise of small-molecule inhibitors, their current widespread use and continued development, these treatments have limitations as cancer therapies. A primary shortcoming is that inhibition by these drugs requires that the target protein has a suitable binding pocket, rendering 85% of the proteome (including transcription factors and scaffolding proteins) ‘undruggable’ by small-molecule inhibitors4. In addition, high local concentrations of small-molecule inhibitors must be continuously present for these drugs to exert their therapeutic effects (occupancy-driven pharmacology)5. Chronic, elevated drug exposure might increase the risk of certain adverse effects as well as cause cumulative toxicities6. Continual treatment with small-molecule inhibitors might also select for mutations in their target proteins or induce activation of compensatory mechanisms that lead to drug resistance, which has been reviewed in detail elsewhere3,7–13.

Heterobifunctional protein degraders are a new class of agents that eliminate, rather than just inhibit, their target proteins. The protein degrader mechanism of action, first proposed more than two decades ago14, is anticipated to ameliorate some of the drawbacks associated with small-molecule inhibitors. Following substantial efforts to optimize these drugs in the laboratory, protein degraders first entered clinical testing in 2019, and initial safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetic results in patients with cancer are now emerging. Herein, we provide an overview of the progress of heterobifunctional protein degrader development, review the preclinical and clinical data for protein degraders currently in clinical trials for patients with cancer, and consider prospects and potential challenges for these agents.

Protein degrader mechanism of action

The ubiquitin–proteasome system is a principal cellular pathway for protein homeostasis. In brief, unneeded or misfolded proteins are tagged with multiple units of ubiquitin and thus marked for degradation by the 26S proteasome. This tagging function is carried out through the concerted actions of several enzymes: an E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme and an E3 ubiquitin ligase. The E3 subset is involved in the recognition of protein substrates to be degraded. The detailed structure and function of ubiquitin ligases and the proteasome have been reviewed elsewhere15–19.

More than 20 years have elapsed since the first report describing the use of fully synthetic chemical biology tools to leverage an E3 ubiquitin ligase to trigger the degradation of a target protein that is not its natural substrate14. Protein degrader molecules are tripartite, heterobifunctional molecules consisting of a target-protein binder, an E3 ligase binder and a linker joining the two binders. By bringing the target protein and E3 ligase into close physical proximity, the ubiquitin ligase machinery can be co-opted to transfer ubiquitin to the target protein, leading to its degradation by the proteasome (FIG. 1).

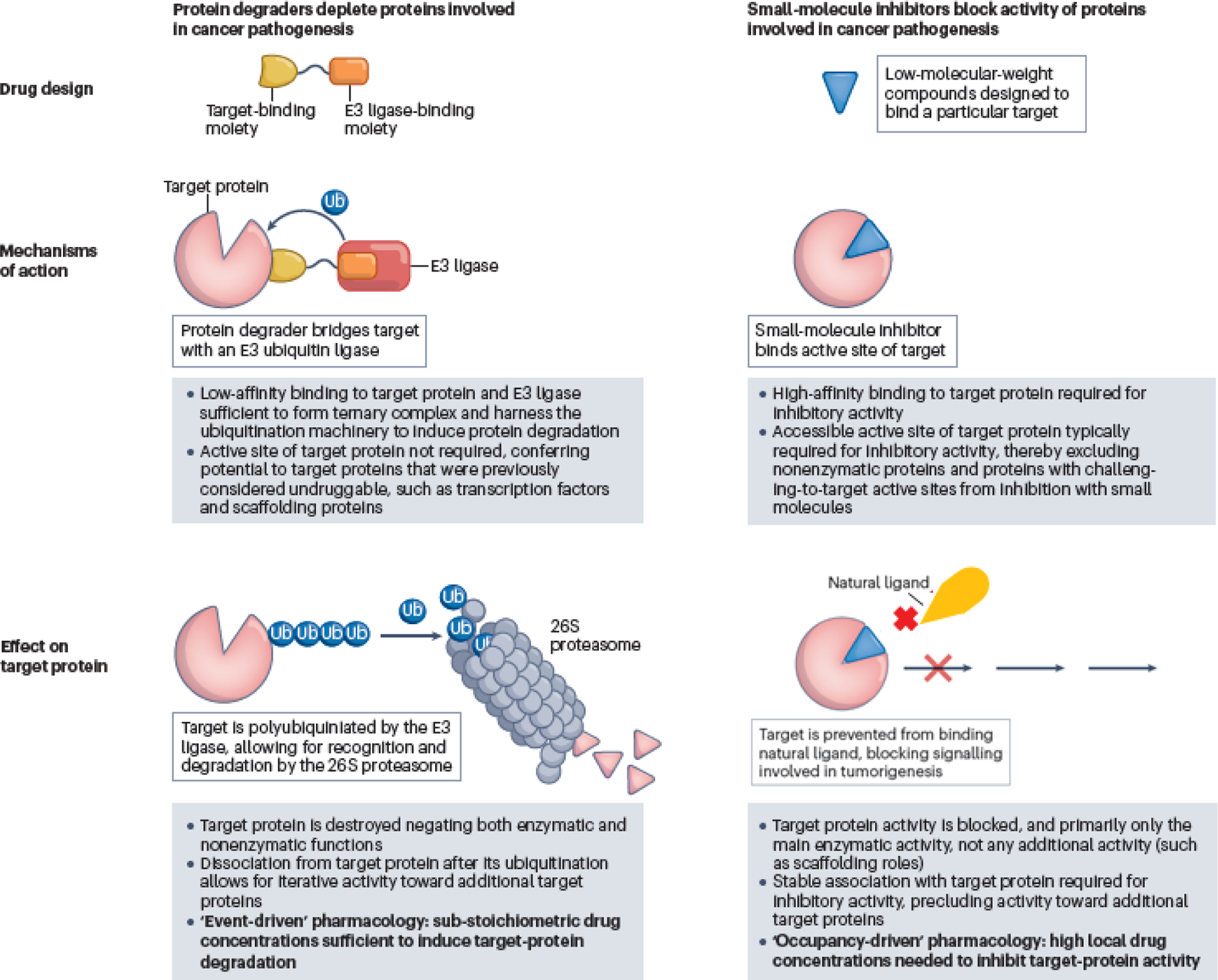

Fig. 1 │. Targeting proteins involved in cancer pathogenesis with protein degraders versus small-molecule inhibitors.

Protein degraders mediate a transient interaction between an E3 ligase and a target protein, leading to ubiquitin (Ub) tagging of the target protein and its subsequent degradation by the proteasome. Small-molecule inhibitors bind to an active site on a target protein to block its activity.

Protein degraders, which contain separate moieties to engage both the target protein and E3 ligase, share many similarities, and some important differences, with the related molecular glue degraders (BOX 1)20–21. The heterobifunctional proximity-inducing concept pioneered with protein degraders has also been shown to extend to other modes of degradation, as well as to post-translational modifications beyond ubiquitination (BOX 2)22; however, this article focuses on heterobifunctional protein degraders.

Box 1 │ Molecular glues versus heterobifunctional protein degraders.

Molecular glues are monovalent small molecules that induce the degradation of a target protein20,21. They contrast chemically with heterofunctional protein degraders, which are bivalent, but share similarities in their overall mechanism of action. Classic molecular glues bind to and alter the substrate preference of an E3 ligase toward the target protein of interest. Other glues have been identified that mediate degradation by simultaneously binding to both an E3 ligase and protein of interest in an induced pocket, or that induce degradation by destabilizing the protein of interest through aggregation. Given the spectrum of possible binding events leading to degradation, molecular glues and protein degraders are best described as being on a mechanism of action continuum. Molecular glues that are being tested in clinical trials in patients with cancer include CC-220 (NCT02773030), CC-92480 (NCT03989414), CC-90009 (NCT02848001 and NCT04336982), CC-99282 (NCT04434196 and NCT03930953), CFT7455 (NCT04756726) and DKY709 (NCT03891953).

Box 2 │. Alternative chimeric molecule approaches as cancer treatment.

The concept of proximity-induced pharmacology with heterobifunctional small molecules, pioneered with protein degraders for targeted protein degradation, has been shown to be extensible to both other modes of degradation and other post-translational modifications22. Other examples of small-molecule proximity-induced pharmacology include:

Lysosomal and autophagosomal degradation: lysosome-targeting chimeras (LYTACs); macroautophagy degradation-targeting chimeras (MADTACs); autophagy-targeting chimeras (AUTACs); and autophagosome-tethering compounds (ATTECs)

RNA degradation: ribosomal targeting chimeras (RIBOTACs)

Protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation: phosphorylation-inducing chimeric small molecules (PHICS); phosphorylation targeting chimeras (PhosTACs); and phosphatase recruiting chimeras (PHORCs)

Protein acetylation: acetylation tagging system (AceTAG)

Protein deubiquitination: deubiquitinase targeting chimeras (DUBTACs)

Heterobifunctional protein degraders have features that differentiate their pharmacology from that of traditional small-molecule inhibitors (TABLE 1). First, because protein degraders orchestrate the formation of a transient and reversible ternary complex (consisting of the target protein, E3 ligase and the protein degrader) and because the subsequent proteasomal degradation is kinetically irreversible, protein degraders can promote the degradation of multiple target molecules in a sub-stoichiometric manner. Protein degraders are thus freed from the occupancy-driven paradigm of traditional pharmacology and are instead best described as having event-driven pharmacology. Second, protein degrader ternary complexes can be positively or negatively cooperative owing to induced protein–protein interactions between the target protein and E3 ligase23. Therefore, limited direct relationship might exist between the binary binding affinity of the protein degrader for the target or E3 ligase and the overall binding affinity of the ternary complex and/or the subsequent degradation efficiency24. The lack of these direct relationships, discussed in further detail below, may lead to unexpected and counterintuitive phenomena, including generation of potent degraders from weak binders to the protein of interest and dramatic improvements in degradation selectivity compared to inhibition selectivity. The requisite ternary complex might also lead to a bell-shaped dose–response curve (termed the ‘hook effect’) with protein degraders, resulting from binary complex formation outcompeting ternary complex formation at high degrader concentrations25. New terminology has arisen to describe protein degraders, notably the concentration to achieve half-maximal degradation (DC50) of target proteins and the maximal degradation achieved (Dmax)26. Attention has also been dedicated to understanding the kinetics underlying the mechanism of protein degrader action, the time-dependence of DC50 and Dmax, and additional descriptors beyond DC50 and Dmax27.

The earliest examples of protein degraders were peptidic in nature14. Protein degraders composed entirely of small molecules were first described in 2008 (FIG. 2)28. The discovery of ‘all-small-molecule’ protein degraders, together with the identification of high-quality, small-molecule E3 ligase ligands, has triggered a landslide of academic and industrial research activity (FIG. 2), culminating in the founding of multiple protein degrader-focused companies to explore the human therapeutic potential of the modality.

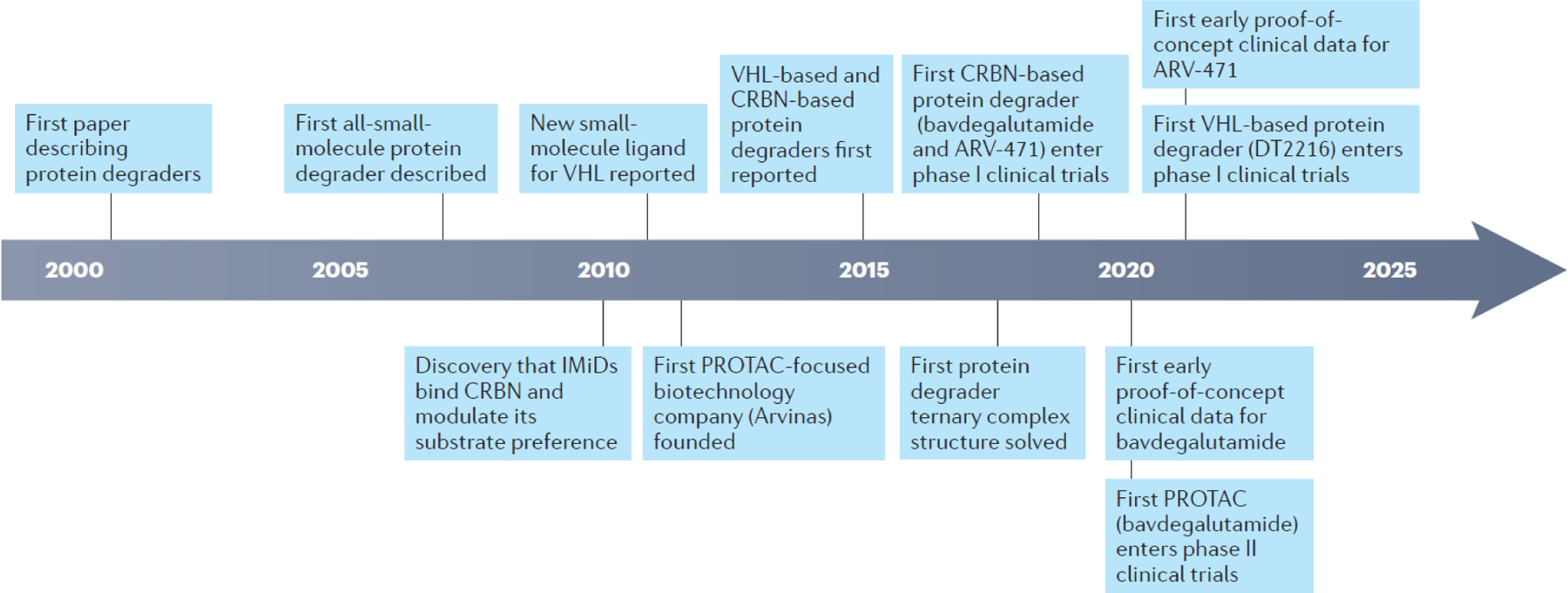

Fig. 2 │. Timeline of key advances in protein degrader development.

CRBN, cereblon; IMiD, immunomodulatory drug; PROTAC, PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera; VHL, Von Hippel-Lindau.

] Extraordinary progress has been made since the first publication on protein degrader technology in 2001, including design and refinement of the molecules through medicinal chemistry that ultimately led to initiation of clinical trials of protein degraders in patients with cancer.

Protein degrader design and advances

Target selection

When considering the therapeutic potential of protein degraders, a crucial early decision related to which targets to pursue. Given the pharmacokinetic burden of relatively large, ‘beyond rule of 5’ molecules such as heterobifunctional protein degraders (see Pharmacokinetic considerations section), the logical targets to pursue were ones for which other therapeutic modalities had been tried and failed or could not be tried at all. A framework, the tenets of protein degrader targets, was proposed to inform target selection29. This framework consists of six general areas poised to take advantage of the unique, event-driven pharmacology of protein degraders compared with other therapeutic modalities: 1) classically undruggable targets; 2) resistance mutations; 3) gene amplification and/or protein overexpression; 4) differential isoform expression or localization; 5) proteins with scaffolding function; and 6) protein aggregates29. Classically undruggable oncology targets (tenet 1), such as KRAS30 and the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)31, have now been successfully degraded using protein degraders. The potential to degrade proteins without directly targeting an active site has been further demonstrated with protein degraders targeting the myristate binding site of the oncogenic fusion protein BCR-ABL132. Resistance to targeted oncology therapies is often driven by the emergence of mutations that impair inhibitor binding (tenet 2) and/or overexpression of the target (tenet 3) to the point that the drug can no longer be dosed to achieve sufficient occupancy for efficacy. Protein degraders have been described that can target the clinically relevant C481S mutant of BTK33. This mutation precludes the covalent binding that underlies the activity of clinical BTK inhibitors, but the residual weak non-covalent binding affinity of those inhibitors is sufficient to be derivatized into active degraders. The continued dependence of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) on the androgen receptor (AR), driven by mutations and overexpression in response to anti-androgen therapies34–37, coupled with the known clinical validity of this target, was a primary driver in the selection of AR as the target for multiple protein degraders38–41. Single protein isoforms are often disease drivers but achieving isoform selectivity with small-molecule inhibitors is challenging owing to a high degree of binding-site homology (tenet 4). Protein degraders can demonstrate emergent isoform degradation specificity, even when designed using non-selective target-protein binders, as in the case of the development of selective CDK4 or CDK6 degraders from CDK4/6 inhibitors42. Emergent selectivity of degraders, even in families of highly homologous proteins, is commonly observed and has been described as a consequence of differential cooperativity in ternary complex formation23,43. Scaffolding proteins, which exert their function in complex with other proteins rather than through catalytic activity of their own, are difficult to directly target with traditional small molecules (tenet 5). Such proteins can, however, be targeted using protein degraders, as in the case of degraders of the IRAK3 pseudokinase44. Protein aggregates (tenet 6) are implicated in neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, and protein degrader approaches are also being explored in this area45.

Choice of E3 ligase

More than 600 E3 ligases are known in the human genome and are potentially available for recruitment by heterobifunctional protein degraders, although only ~10 of these have been successfully utilized to date for targeted protein degradation. The first all-small-molecule protein degrader leveraged nutlin-based binders of the MDM2 ligase28. Degraders based on binders of the cellular Inhibitor of Apoptosis (cIAP) ligase, termed SNIPERs (Specific and Non-genetic Inhibitor of apoptosis-dependent Protein Erasers), have also been developed46. However, the two E3 ligases that have become the workhorses of targeted protein degradation are von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) and cereblon. The development of VHL-based protein degraders was first driven by the discovery of a potent and specific small-molecule VHL binder47–48 that exploits the unique hydroxyproline recognition element in the HIF1α-binding site of VHL49–50. Cereblon-based protein degraders, in turn, were enabled by the discovery that the so-called immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs), a class of molecular glue degraders bind to and modulate the substrate recognition function of cereblon51–53. These two ligases have achieved a privileged status because of the following characteristics: 1) they are readily-available, small-molecule binders with structural enablement for identification of linker attachment points; 2) they have flexibility to robustly degrade a wide variety of targets; and 3) their relatively ubiquitous expression enables high levels of systemic degradation to be achieved. However, exploitable exceptions to this ubiquitous expression exist; for example, low expression of VHL in platelets has been leveraged to deliver the clinical stage BCL-XL degrader DT2216 with a reduced potential for thrombocytopenia54.

Beyond cereblon and VHL is a vast open frontier of new ligand discovery for E3 ligases55. Increasing interest is being focused on the development of ligands for tissue-specific or tumour-specific E3 ligases, which might be of benefit when indiscriminate systemic target degradation could lead to unacceptable toxicities and a narrow therapeutic index. Common pan-essential genes targeted in cancer with inhibitors include those involved in cell cycle or epigenetic regulation, DNA damage response, and protein homeostasis and are frequently associated with narrow therapeutic indices56. The systemic degradation of such a pan-essential gene product would likely also show high systemic toxicity, but restricted degradation in a tumour could in principle provide a well-tolerated therapeutic. New discovery platforms based on covalent ligand screening have shown promise for the rapid identification of new E3 ligase binders, and several covalent tool ligands have now been identified for RNF4, RNF114, DCAF16, KEAP1, DCAF11 and FEM1B57.

Target ligand design

Historically, heterobifunctional protein degraders have leveraged ‘off-the-shelf’ target-protein binders, originally designed as inhibitors without foresight toward evolution into degraders. As novel targets are explored for degradation, particularly classically undruggable targets, the need to identify new target-protein binders has intensified. DNA-encoded library (DEL) technology58, a complementary approach for ligand identification for use in protein degraders, is agnostic to the binding site and functional activity of the ligand, and provides a potential linker attachment vector (at the point of DNA barcode attachment) in the absence of any further structural enablement. A proof-of-principle study using DEL for the discovery of new oestrogen receptor α (ERα) ligands, which were subsequently turned into active protein degraders, was reported in 202159. DEL technology is also potentially useful for the discovery of new molecular glue degraders, E3 ligase ligands, and whole protein degraders55, 60–61.

Linker design

The chemical linker between the target protein and E3 ligase binders is an area of increasing medicinal chemistry focus in protein degrader design, a field of study colloquially termed linkerology. Linker length is routinely surveyed using simple alkyl or polyethylene glycol (PEG) linkers to find the optimal spacing between the target protein and E3 ligase. Too short a linker prevents the formation of a productive ternary complex owing to steric clash between the proteins; too long a linker might miss the opportunity to capitalize on positive cooperativity in the ternary complex62. In some cases, linkers are not bystanders in the ternary complex and can form their own contacts with protein surfaces23. Several studies have now demonstrated that conformational constraint of the linker can further enhance potency via reduction in degrees of freedom or a locking in of a bioactive conformation41,63–65. Conformationally restricted linkers have been used as a potency driver in a series of SMARCA2/4 degraders63, AR degraders41,64 and the ER degrader ARV-47165. Linker attachment points and the distance between the target-protein and E3 ligase binders can profoundly influence degradation selectivity, as demonstrated in the case of tuning p38 isoform degradation selectivity, and more broadly overall kinase degradation selectivity, starting from a relatively promiscuous target-protein binder66. With regard specifically to use of cereblon as the E3 ligase, a study showed that variation of the linker attachment point to the E3 ligase binder influenced both overall protein degrader aqueous stability and cereblon neosubstrate degradation67. Furthermore, linkers present an opportunity to tune the pharmacokinetic properties of a protein degrader (see Pharmacokinetic considerations section).

Structure-aided design

The rational design of protein degraders informed by structural biology remains in its infancy. This challenge is compounded by difficulty in obtaining 3D structural images of the ternary complexes that are crucial to the protein degrader mechanism of action, whether via X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy or modelling. In a landmark study, an X-ray crystal structure obtained between a protein target of interest (BRD4) and an E3 ligase (VHL) mediated by a protein degrader (MZ1) demonstrated the extensive protein-protein contacts in the ternary interface that drive ternary binding cooperativity, the involvement of the linker in protein-ligand interactions and a potential explanation for degradation selectivity in the BRD family23. This structure also revealed a path to linker optimization from a different attachment vector and represents the first reported example of structure-based linker design reported for a protein degrader. Structural biology has subsequently been successfully used in the case of SMARCA2/4-VHL ternary complexes to optimize a protein degrader linker for improved degradation potency63. In another study, a set of X-ray crystal structures of protein degrader-mediated ternary complexes between BTK and cIAP indicated a high degree of conformational plasticity, dependent on the degrader linker length68, implying difficulty in subsequent compound optimization based on such structures. On the computational side, a suite of in silico tools from different groups has emerged to predict protein degrader docking poses69–72.

Pharmacokinetic considerations

As a class, heterobifunctional protein degraders lie predominantly in the beyond the rule of 5 space73, meaning they possess physicochemical properties (molecular weight, hydrogen bond donor and/or acceptor counts, and octanol–water partition coefficient, among others) outside the ranges commonly associated with probable oral absorption74. Nonetheless, the presence of multiple orally bioavailable protein degraders in clinical development speaks to the need for a reconsideration of the chemical space associated with oral absorption. Whereas the rule of 5 describes a probable oral absorption space, several reports have attempted to describe the boundaries of a possible oral absorption space beyond the rule of 5 space with physicochemical descriptors both generally75 and for protein degraders specifically76–77. Although a clear set of physicochemical property descriptors specifically for orally bioavailable protein degraders has not been reported, Pike et al. note that IMiD-based/CRBN-recruiting degraders are overall more drug-like than those recruiting other E3 ligases based on their reduced molecular weight, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor counts and lipophilicity77. Only a few systematic studies have reported on the pharmacokinetics of heterobifunctional protein degraders within a given chemical series64,78, but the studies reported to date demonstrated that optimization of degraders to provide adequate levels of oral absorption is possible. However, data from a small number of more-comprehensive studies have increased awareness that simple alkyl and PEG linkers might have metabolic liabilities and are associated with a tendency for high protein degrader clearance rates79. More conformationally constrained, bespoke linker designs afford the potential to reduce metabolism and/or enhance oral absorption, for example, via the introduction of solubilizing groups such as basic amines41,64–65.

Protein degraders are anticipated to show nonlinear pharmacodynamics based on the irreversible and time-dependent step (proteasomal degradation) integral to their mechanism of action. Once a protein has been degraded, the recovery of the protein is dictated by its intrinsic resynthesis rate. For proteins with long resynthesis rates, this may lead to large disconnects between protein degrader concentrations at a point in time and the degradation observed at the same point in time. An extreme case of this phenomenon has been demonstrated whereby a single subcutaneous administration in rat of a RIPK2-targeting protein degrader is sufficient to suppress RIPK2 protein levels for >168 h, well beyond the ~72-hour duration of the degrader concentration being maintained above the whole blood IC9080. With sustained release, RIPK2 suppression can be extended to >1 month from a single protein degrader dose81. Beyond experimental studies, additional efforts have been directed toward prospective modelling of protein degrader pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic relationships82–83.

Preclinical evidence

The breakthroughs in protein degrader design described above have paved the way for early phase clinical trials of these agents. To our knowledge, 18 protein degraders are now undergoing evaluation in phase I–III clinical trials in patients with cancer as of 8 January 2023 (TABLE 2). Here, we review the preclinical data that supported moving these drugs from laboratory to clinical studies. The following summary relies on data that have been published or presented at scientific meetings; data that have been disclosed only on corporate websites or industry events are not included.

AR-targeting protein degraders

The key role of androgen signalling in driving prostate cancer progression34–37 made the AR an appealing protein degrader target. Moreover, several drugs that impede the AR pathway are standard treatments for patients with mCRPC84 and provide benchmarks for new AR-targeting agents. Accordingly, five protein degraders that target the AR (bavdegalutamide (previously known as ARV-110), CC-94676, AC176, HP518 and ARV-766) are in clinical trials in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Preclinical data for bavdegalutamide have been reported at several scientific meetings, whereas data for the remaining AR degraders have not been presented or published to date and, therefore, will not be discussed here.

Bavdegalutamide, a PROteolysis Targeting Chimera (PROTAC) protein degrader, contains a cyclohexyl moiety that binds to the AR ligand-binding domain, and engages the cereblon-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase to enable AR polyubiquitination41. Bavdegalutamide induced potent degradation of the AR in both vertebral cancer of the prostate (VCaP) and lymph-node carcinoma of the prostate (LNCaP) cell lines, with a DC50 of ~1 nM39,41. In a proteomic screen of nearly 4,000 detectable proteins in VCaP cells, treatment with 10 nM bavdegalutamide for 8 hours led to selective AR degradation with a Dmax of 85%39,41. In addition to wild-type AR, bavdegalutamide degraded clinically relevant AR mutants (T878A, H875Y, F877L and M896V) in preclinical experiments39.

In comparison with enzalutamide (which is an AR antagonist approved for the treatment of men with prostate cancer), bavdegalutamide resulted in greater inhibition of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) synthesis and cellular proliferation as well as greater induction of apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines39. The activity of bavdegalutamide has been tested in various animal models of prostate cancer. In both castrated and non-castrated mice harbouring VCaP tumours, bavdegalutamide demonstrated substantially greater tumour growth inhibition than enzalutamide, and in an AR-expressing patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model (TM00298), 100% inhibition of tumour growth by bavdegalutamide was accompanied by a >90% reduction in PSA levels39,41.

Bavdegalutamide has also been tested in mouse models of tumours with resistance to approved AR-targeting agents, including enzalutamide and the androgen biosynthesis inhibitor abiraterone. Treatment with bavdegalutamide at doses of 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg once daily inhibited tumour growth by 60% and 70%, respectively, in an enzalutamide-resistant VCaP model39. A three-phase preclinical study in castrated mice bearing VCaP tumour xenografts evaluated treatment with abiraterone alone, bavdegalutamide alone, or combination of abiraterone and bavdegalutamide (phase 1), followed by treatment with abiraterone alone until the development of resistance (phase 2), and then randomization to abiraterone or bavdegalutamide treatment (phase 3)85. In phase 1, the abiraterone–bavdegalutamide combination showed greater tumour growth inhibition than either agent alone, and in phase 3, bavdegalutamide reduced the volume of abiraterone-resistant tumours. These data suggest the potential for enhanced clinical activity with an abiraterone–bavdegalutamide combination as well as for bavdegalutamide as an add-on therapy to abiraterone at the time of biochemical progression (rising PSA levels), to overcome abiraterone resistance; the latter hypothesis is being tested in a phase Ib clinical trial (NCT05177042; TABLE 2)85.

ER-targeting protein degraders

ER+ breast cancer accounts for the majority of breast cancer cases in women, and several endocrine therapies that block ER activity are approved to treat different stages of this disease86–87. The ER antagonist fulvestrant acts, in part, by inhibiting nuclear translocation of the ER, leading to proteasomal degradation of this protein87. Therefore, fulvestrant has confirmed the value of ER degradation as a treatment approach88; however, up to 50% of baseline ER levels remain after fulvestrant treatment89–90. In addition, patients can develop mutations in the gene encoding the ER (ESR1) during treatment with endocrine therapy86–87, and some of these alterations might reduce the sensitivity of cells to fulvestrant and other investigational selective ER degraders (SERDs)91. To address the deficiencies of fulvestrant as an ER degrader, two cereblon-based protein degraders that target the ER (the PROTAC ARV-471 and AC682) are in clinical development for the treatment of ER+ breast cancer (TABLE 2), and preclinical data have been reported at scientific meetings.

In preclinical analyses in numerous breast cancer cell lines, ARV-471 resulted in degradation of wild-type ER, with a DC50 of 1–2 nM; ER mutants, such as Y537S and D538G, were also degraded by ARV-47165,92. Moreover, ARV-471 monotherapy has encouraging antitumour activity in several models of ER-dependent breast cancer65,92. In an orthotopic, oestradiol-dependent MCF7 xenograft model, treatment with ARV-471 at doses of 10 mg/kg or 30 mg/kg once daily resulted in tumour growth inhibition of >90% (including evidence of tumour regression [that is, >100% tumour growth inhibition] at the 30 mg/kg dose), compared with only 46% by fulvestrant, with concurrent reduction of tumoural ER levels by >90%,92. Once-daily doses of 30 mg/kg ARV-471 also resulted in 65% tumour growth inhibition and a 73% decrease in tumoural ER levels in a tamoxifen-resistant MCF7 xenograft model92. Additionally, in an ESR1-mutant (ERY537S) PDX model, ARV-471 inhibited tumour growth by 99% and 106%, respectively, at once-daily doses of 10 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg, compared with 62% with twice-weekly doses of 200 mg/kg fulvestrant; the associated levels of ERY537S degradation were 79% and 88%, respectively, with ARV-471 versus 63% with fulvestrant65,92.

Combination of ARV-471 with the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib has been tested in preclinical models. In the oestradiol-dependent MCF7 xenograft model, treatment with 30 mg/kg ARV-471 once daily plus 60 mg/kg palbociblib once daily resulted in a greater tumour growth inhibition than either agent alone92. This combination yielded 131% tumour growth inhibition compared with 108% tumour growth inhibition with the combination of 200 mg/kg fulvestrant twice weekly plus 60 mg/kg palbociblib once daily65,92. These findings support the ARV-471-palbociclib combination cohort that is part of the first-in-human phase I/II trial of ARV-471 in patients with advanced-stage ER+HER2− breast cancer (NCT04072952; TABLE 2)93.

The second ER-targeting protein degrader, AC682, induces degradation of ER at a sub-nanomolar DC50 in several breast cancer cell lines, including those expressing the ER mutants Y537S and D538G, as well as in tamoxifen-resistant, oestrogen-deprived cells, with peak activity after a few hours of treatment94. Degradation of the ER by AC682 translates into reduced expression of ER-regulated genes and inhibition of cell proliferation94. AC682 results in tumour growth inhibition or regression with >90% decreases in tumoural ER levels in the oestradiol-dependent MCF7 xenograft model, with tumour stasis observed at a dose of 3 mg/kg daily94. In an ESR1-mutant (Y537S) PDX model, AC682 resulted in substantially greater tumour growth inhibition than fulvestrant94. Administration of AC682 in combination with palbociclib in both oestradiol-dependent and a tamoxifen-resistant MCF7 models suggested synergistic activity of these agents94.

BTK-targeting protein degraders

BTK is a key component of signalling pathways that lead to the activation, proliferation and survival of B cells. Accordingly, several small-molecule inhibitors of BTK are approved (such as ibrutinib) or are in clinical development for the treatment of B-cell malignancies; however, the efficacy of these agents is limited by the development of resistance mutations in BTK95. Four cereblon-based protein degraders that target BTK (NX-2127, NX-5948, BGB-16673 and HSK29116) are in clinical development for patients with B-cell malignancies (TABLE 2). Preclinical data for NX-212796–98 and NX-594899 have been disclosed at scientific meetings, but findings for BGB-16673 and HSK29116 are not yet available.

NX-2127 induces degradation of wild-type BTK in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) cell lines, with DC50 values of 4 nM and 4–6 nM, respectively; additionally, NX-2127 results in degradation of the ibrutinib-resistant BTK C481S mutant (DC50 13 nM) and thus blocks proliferation of ibruitinib-resistant DLBCL cells96. NX-2127 has activity similar to IMiDs via cereblon-induced degradation of the neosubstrates Ikaros and Aiolos, resulting in T-cell activation and IL-2 production96. NX-2127 at doses of 30 mg/kg and 90 mg/kg has been shown to inhibit tumour growth in xenograft mouse models of lymphoma expressing wild-type or C481S-mutant BTK96. Substantial degradation of BTK in B cells has been observed with oral administration of 1 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg NX-2127 to cynomolgus monkeys96. In a subsequent presentation97, NX-2127 was shown to more potently reduce the viability of DLBCL and MCL cells than the BTK inhibitors ibrutinib, acalabrutinib and pirtobrutinib or the IMiDs pomalidomide and lenalidomide. RNA sequencing revealed that exposure to NX-2127 resulted in different gene-expression profiles in MCL cells compared with those associated with BTK inhibitor or IMiD exposure; in contrast to ibrutinib or pomalidomide, NX-2127 downregulated genes involved in DNA replication and repair, the cell cycle and survival signalling pathways97. In addition, NX-2127 was associated with increased expression of CD1c, which is involved in T-cell recognition of cancer cells97. Recently, NX-2127 was shown to bind to and degrade multiple BTK inhibitor resistance mutants (including the kinase-dead L528W and V416L mutants with a scaffold function), in several cases with comparable kinetics to wild-type BTK98. NX-2127 reduced CD86 expression, a marker for B-cell activation, in cells expressing wild-type or mutant BTK and more potently induced killing of cells expressing wild-type or mutant BTK than small-molecule BTK inhibitors or IMiDs98.

The protein degrader NX-5948 was designed to target BTK for degradation but, unlike NX-2127, lacks the ability to degrade Ikaros or Aiolos, thus precluding immunomodulatory effects associated with the degradation of these substrates99. NX-5948 results in degradation of both wild-type and C481S-mutant BTK in DLBCL cell lines with a DC50 of 0.32 nM and 1.0 nM, respectively, with reduced cell viability also observed99. Selective degradation of BTK by NX-5948 was confirmed in a proteomic analysis in DLBCL cells99. In xenograft mouse models of ibrutinib-resistant DLBCL, NX-5948 at doses of 3 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg inhibited tumour growth by 36.3%, 99.0% and 99.7%, respectively99. Notably, NX-5948 was shown to permeate the blood–brain barrier, inducing BTK degradation by >80% in implanted DLBCL cells and microglia in the brain99. Accordingly, NX-5948 reduced the tumour burden of intracranial DLBCL cells and prolonged survival compared with vehicle in a mouse model99.

BRD9-targeting protein degraders

Bromodomain-containing protein 9 (BRD9) is a component of the aberrant BAF chromatin remodelling complex also containing the oncogenic SS18-SSX fusion protein that is implicated in the development of synovial sarcoma100. Two protein degraders that target BRD9, CFT8634 and FHD-609, are being evaluated in patients with advanced-stage synovial sarcoma (TABLE 2).

CFT8634 is a cereblon-based protein degrader that selectively degrades BRD9 with a DC50 of 2.7 nM after 2 hours of treatment101. In a proteomic screen in the HSSYII synovial sarcoma cell line, treatment with 100 nM CFT8634 for 4 hours yielded substantial degradation of only BRD9 among >9,000 quantified proteins101. CFT8634 induced degradation of BRD9 in both a synovial sarcoma (SS18−SSX1 fusion-positive) cell line and a soft-tissue sarcoma (BAF wild-type) cell line101. Dose-proportional exposure of CFT8634 was demonstrated in a synovial sarcoma cell line-derived xenograft model, and CFT8634 at doses ranging from 1 mg/kg to 50 mg/kg once daily induced robust tumour growth inhibition in two different PDX models of synovial sarcoma101. In one of these PDX models, tumour regression persisted after withdrawal of CFT8634 treatment101.

FHD-609, the second protein degrader that targets BRD9, induced BRD9 degradation in tumour tissue of a xenograft model of synovial sarcoma after 3 hours of treatment at doses of 0.1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg, although multiple doses of the 3 mg/kg dose were needed for complete degradation102. RNA sequencing of xenografts 24 hours after treatment with FHD-609 showed decreased expression of MYC compared with vehicle, as well as decreased expression of genes activated by MYC and increased expression of genes repressed by MYC; this effect was greater at the higher dose of FHD-609 and after multiple doses102.

Protein degraders targeting other proteins involved in cancer pathogenesis

DT2216 is a VHL-based protein degrader that targets the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-XL. DT2216 was selected among other candidates for clinical development in patients with various solid tumours on the basis of its potent degradation of BCL-XL (DC50: 63 nM after 16 hours of treatment) and cytotoxic effects in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL) cells but not in platelets54. DT2216 has reported binding affinity for other BCL-2 family members, but selectively degrades BCL-XL without affecting protein levels of BCL-2, BCL-W or MCL-154. Once weekly dosing of DT2216 led to substantial tumour growth inhibition in a xenograft mouse model of T-ALL54. A subsequent publication reported cytotoxic activity of DT2216 toward various BCL-XL-dependent T cell lymphoma cell lines and inhibition of tumour growth in a mouse xenograft model of BCL-XL-dependent T-cell lymphoma103. Treatment of various solid tumour specimens with DT2216 depleted BCL-XL from the tumour microenvironment, which led to elimination of regulatory T (Treg) cells104.These findings suggest the therapeutic potential of DT2216 in cancers that are dependent on BCL-XL for survival and those in which Treg cells have a key role in maintaining an immunosuppressive microenvironment enabling tumour progression, which is the case in numerous solid tumours105. A recent study analysed BCL-XL levels and survival in 13 T-ALL cell lines following treatment with DT2216106. DT2216 potently inhibited cell growth in 12 of these cell lines regardless of pretreatment BCL-XL expression; only one cell line required DT2216 concentrations that exceeded those reported in the xenograft mouse model of T-ALL and was associated with reduced efficiency of BCL-XL degradation54,106.

KT-413 (previously known as KTX-120) is a cereblon-based protein degrader that targets IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4), a protein involved in transmitting signals downstream of Toll-like receptors as part of the innate immune response to pathogens. Similar to NX-2127, KT-413 has degradation activity toward Ikaros and Aiolos in addition to its target protein107. KT-413 induces selective and potent degradation of IRAK4 (DC50 8 nM after 16–24 hours of treatment) and inhibition of cell growth in MYD88-mutant DLBCL cell lines (half maximal inhibitory concentration 7–29 nM)107. Intermittent oral or intravenous dosing of KT-413 results in tumour growth inhibition, including regression in several mouse MYD88-mutant xenograft models and PDX models of DLBCL107. KT-413 was subsequently shown to inhibit MYD88-dependent NF-κB transcription and induce type 1 interferon signalling, based on downregulation of IFN-regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) and upregulation of IRF7108. In addition, downregulation of DNA replication and cell cycle genes and activation of pro-apoptotic and antiproliferative genes was observed with KT-413108.

KT-333 is a protein degrader that targets STAT3, a transcriptional activator involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis. KT-333 induces potent degradation of STAT3 in solid tumour cell lines, lymphoma cell lines and primary immune cells (DC50 <10 nM in most cell types); degradation of STAT3 was highly selective in a lymphoma cell line109. Accordingly, KT-333 reduces the proliferation and induces apoptosis of lymphoma cells in vitro, and weekly intravenous KT-333 doses ranging from 5 mg/kg to 45 mg/kg or biweekly intravenous doses ranging from 10 mg/kg to 40 mg/kg inhibit tumour growth in xenograft mouse models of lymphoma109. On the basis of pharmacodynamic efficacy simulations, a dose of >1 mg/kg weekly KT-333 was predicted to inhibit tumour growth in humans109.

ASP3082 is a protein degrader that targets KRAS G12D, a mutant form of a GTPase that regulates cell proliferation and survival via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, that has been associated with multiple solid tumours, including pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer110. ASP3082 demonstrated potent degradation of KRAS G12D in pancreatic cancer cells harbouring this mutation and inhibition of ERK phosphorylation, a downstream signal of KRAS 111. A quantitative proteomics assay showed selective degradation of KRAS G12D among >9000 proteins111. In a KRAS G12D pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma xenograft model, ASP3082 administered intravenously once weekly resulted in dose-dependent tumour growth inhibition, including tumour regression111. A single intravenous dose of ASP3082 led to sustained drug concentrations111.

CFT1946 is a cereblon-based protein degrader that targets BRAF V600X, a mutant form of a serine/threonine protein kinase that is a downstream effector of RAS, that has been seen in various cancers including melanoma, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer; several small-molecule BRAF V600X inhibitors have been approved for the treatment of patients with BRAF-mutated cancer112,making BRAF V600X a rational target for protein degrader technology. CFT1946 selectively targeted BRAF-V600E among nearly 9000 proteins in a melanoma cell line, degraded BRAF V600E (but not wild-type BRAF) in a dose-dependent manner with a DC50 of 14 nM at 24 hours, and inhibited ERK phosphorylation113. In a BRAF V600E xenograft mouse model of melanoma, a twice daily dose of 10 mg/kg CFT1946 led to tumour regression and was considered to be the minimum efficacious dose113. In a BRAF V600E/NRAS Q61K xenograft model of resistance to BRAF inhibitors, CFT1946 showed stronger inhibition of ERK phosphorylation than the BRAF inhibitor encorafenib; in addition, the combination of CFT1946 with the MEK inhibitor trametinib reduced ERK phosphorylation to a greater extent than encorafenib plus trametinib and showed greater tumour growth inhibition than CFT1946, trametinib, or encorafenib alone113. CFT1946 also demonstrated degradation of non-V600E BRAF mutants that were ectopically expressed in a human cell line113.

Available clinical evidence

In 2019, the PROTAC AR degrader bavdegalutamide became the first drug of this class to enter clinical trials in a phase I study in patients with mCRPC (FIG. 3). The designs for several clinical trials of protein degraders as cancer treatment (TABLE 2) have been presented at scientific meetings in 202285,93,114–118. To date, however, clinical data from ongoing oncology studies have been disclosed only for the PROTAC AR degrader bavdegalutamide, the PROTAC ER degrader ARV-471, and the BTK degrader NX-2127.

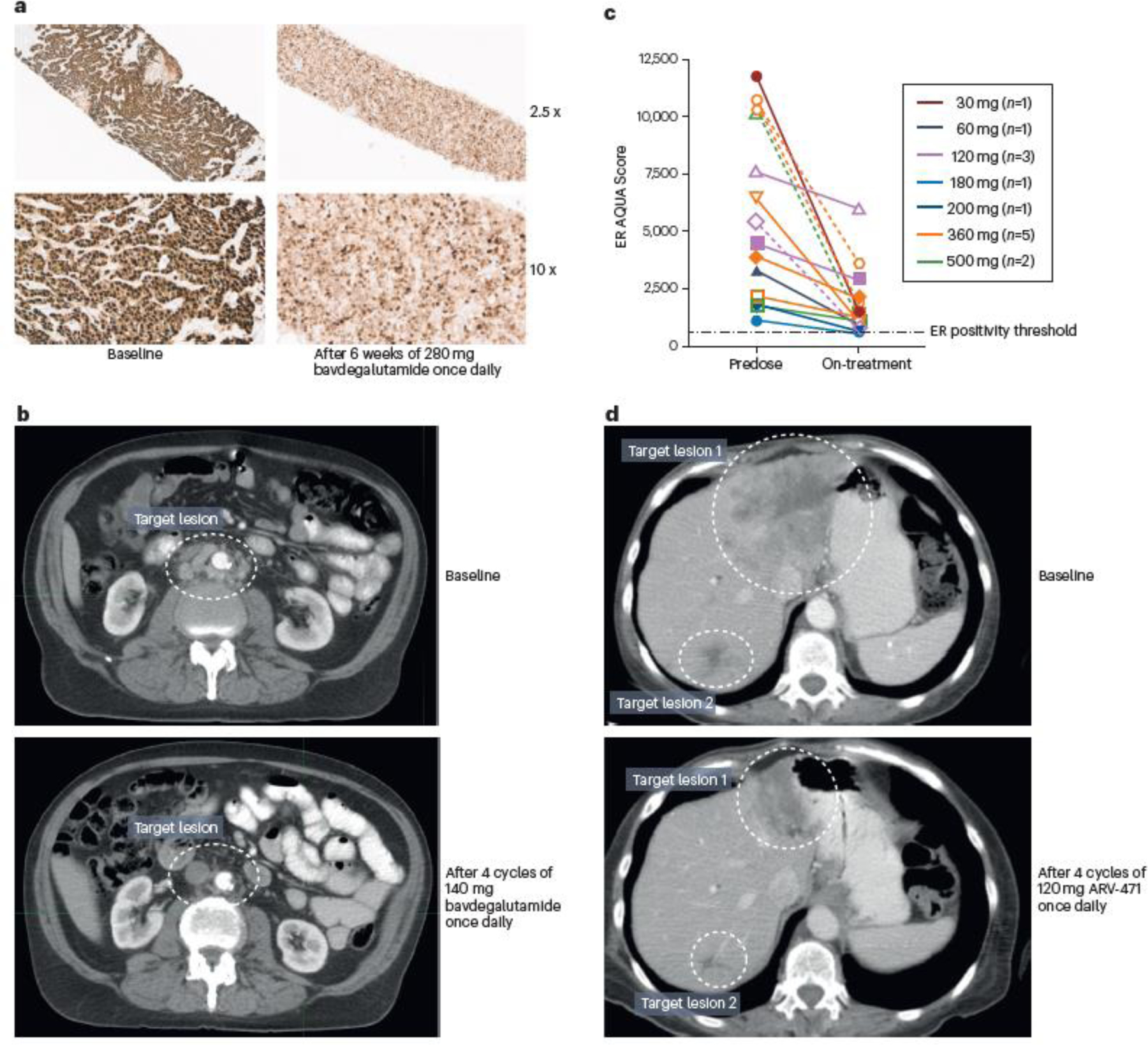

Fig. 3 │. Clinical proof-of-concept for PROTAC protein degraders.

a │ Immunohistochemistry images demonstrating decreased androgen receptor (AR) protein levels in a wild-type/amplified tumour from a patient with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) following 6 weeks of 280 mg bavdegalutamide once daily40. b │ CT images showing near complete reduction of retroperitoneal adenopathy in an AR T878A/H875Y-positive patient with mCRPC following four 28-day cycles of 140 mg bavdegalutamide once daily40–41. c │ Quantitative immunofluorescence data demonstrating decreased oestrogen receptor (ER) protein levels in tumour biopsy samples from patients with breast cancer after a median of 31 days (range 16–77) of once-daily treatment with doses of ARV-471 used in phase 1 dose escalation123. d │ CT images showing reduction in target lesions in a patient with breast cancer harbouring an ESR1 D538G mutation after four 28-day cycles of 120 mg ARV-471 once daily123. AQUA, automated quantitative analysis; PROTAC, PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera

Bavdegalutamide clinical data

The initial phase I/II trial of bavdegalutamide (NCT03888612) enrolled heavily pretreated patients with mCRPC who had exhausted approved treatment options, and thus present an unmet need for novel therapies. As a first-in-human trial of a first-in-class therapy, the aims of the phase I portion of this trial were to evaluate safety and tolerability of bavdegalutamide in order to determine the maximum tolerated dose and identify a recommended phase II dose (RP2D). In this dose-escalation phase, bavdegalutamide at doses ranging from 35 mg to 700 mg once daily or 140 mg to 420 mg twice daily were orally administered to men with mCRPC who had received at least two prior therapies (including abiraterone and/or enzalutamide) and experienced disease progression on their most recent therapy38,40–41.

The first presentation of data from this study reported results from the initial 22 patients treated with bavdegalutamide, of whom 77% had previously received both abiraterone and enzalutamide, and 77% had received prior chemotherapy40. Key findings included histological evidence of AR degradation with a decrease in AR staining after treatment with bavdegalutamide and further proof of concept with clinical responses40. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) reported in ≥20% of these patients were nausea (27%), diarrhoea (27%) and fatigue (23%)40. At doses from 35 mg to 280 mg once daily, bavdegalutamide exposure was dose-proportional40, and doses ≥140 mg once daily yielded exposure above the efficacious threshold based on tumour growth inhibition in castrated and non-castrated VCaP mouse models39. Together, the safety and pharmacokinetic data supported further dose escalation. Decreased levels of AR protein were observed in tumour tissue of a patient after 6 weeks of bavdegalutamide treatment (FIG. 3a), providing clinical proof-of-concept for the protein degrader mechanism of action. In this highly refractory mCRPC population, two patients had clinically relevant responses with bavdegalutamide, with serum PSA reductions of 74% and 97%, the latter associated with a confirmed RECIST partial response (FIG. 3b). A subsequent analysis of the phase I dose-escalation cohort (n = 37) provided further support for an exposure–activity relationship for bavdegalutamide, and showed that with a total daily dose of 420 mg, exposure exceeded the predicted efficacious threshold based on tumour growth inhibition in a preclinical enzalutamide-resistant mode40; on the basis of safety, pharmacokinetic and efficacy findings, 420 mg once daily was selected as the RP2D41.

A notable finding from this phase I study was enhanced activity of bavdegalutamide in a biomarker-defined patient subset; in five patients with prior exposure to novel hormonal agents and tumours harbouring AR T878 and/or H875 mutations (AR 878/875 positive), which have previously been shown to confer resistance to novel hormonal agents34,119–122, the rate of best serum PSA declines ≥50% (PSA50) was 40%38. Bavdegalutamide has similar degradation kinetics toward AR T878A and H875Y as wild-type AR in vitro — notably, evidence that other drugs can target altered versions of AR is lacking39. Thus, preclinical and early clinical data obtained with bavdegalutamide spurred the design of the phase II expansion (ARDENT) cohort in patients with confirmed mCRPC. Patients who had received one or two prior novel hormonal agents (for example, abiraterone and/or enzalutamide) and no more than one chemotherapy regimen each for CRPC and castration-sensitive prostate cancer were enrolled in biomarker-defined subgroups based on tumour DNA sequencing: an AR 878/875 subgroup, a subgroup with tumours harbouring wild-type AR or other AR alterations (AR WT/Other), and a subgroup with tumours harbouring AR L702H mutations or the AR-V7 splice variant (AR 702/V7); in preclinical studies, bavdegalutamide was a less potent degrader of AR L702H and did not degrade AR-V7. Patients who had received only one prior novel hormonal agent and no prior chemotherapy were enrolled in a clinically defined, biomarker-agnostic subgroup (‘Less Pretreated’). Patients in the AR 702/V7 and Less Pretreated subgroups could also have AR 878/875 mutations.

On the basis of the most recent presentation of data from this phase I/II trial of bavdegalutamide (as of the 20 December 2021 data cutoff), 195 patients had been enrolled (71 in phase I and 124 in phase II)38. The median number of prior lines of therapy was six in the phase I portion (69% with both prior abiraterone and enzalutamide and 75% with prior chemotherapy) and four in the phase II portion (39% with both prior abiraterone and enzalutamide and 31% with prior chemotherapy), noting that the phase II study included the ‘Less Pretreated’ subgroup38. Across 152 patients in the phase I/II population who were biomarker-evaluable and PSA-evaluable, the PSA50 rate was 17% and the rate of best PSA declines ≥30% (PSA30) was 31%38. In 28 patients with AR 878/875-positive tumours, regardless of study phase or subgroup, the PSA50 rate was 46% and the PSA30 rate was 57%38. The PSA50 rates in biomarker-evaluable and PSA-evaluable patients in the phase II ARDENT cohort were 75% in the AR 878/875 subgroup (n = 8), 11% in the AR WT/Other subgroup (n = 44), 4% in the AR 702/V7 subgroup (n = 25), and 22% in the Less Pretreated subgroup (n = 27)38. Together, these data demonstrate clinical activity of bavdegalutamide in patients with mCRPC, many of whom were heavily pretreated and all of whom progressed through prior AR-directed therapy. Moreover, the study helped to delineate the biology of prostate cancer in patients who were previously exposed to novel hormonal agents, indicating that mCRPC might remain heavily AR-dependent in the setting of AR mutations associated with drug resistance; patients with AR 878/875-positive tumours might constitute a population particularly sensitive to bavdegalutamide.

TRAEs reported in >20% of 138 patients treated at the RP2D across phase I and II portions were nausea (48%), fatigue (36%), vomiting (26%), decreased appetite (25%) and diarrhoea (20%)38. TRAEs were generally grade 1 or 2, with no grade 4 or higher events, and infrequently led to bavdegalutamide dose reduction (8%) or treatment discontinuation (9%)38. These results substantiate the tolerability profile seen in the earlier analysis of the phase I data40, with no evidence of off-target effects of bavdegalutamide. Further investigation of bavdegalutamide in patients with mCRPC is planned38.

ARV-471 clinical data

Protein degrader clinical activity was corroborated with early data from the first-in-human phase I/II trial (NCT04072952) of the PROTAC ER degrader ARV-471 in patients with ER+/HER2− locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. In the phase I dose-escalation portion of this study, patients had received at least one prior CDK4/6 inhibitor, at least two prior endocrine therapies, and no more than three prior lines of chemotherapy; as of the 30 September 2021 data cutoff, 60 patients were treated with total daily ARV-471 oral doses ranging from 30 mg to 700 mg in this portion of the study123. Patients had received a median of four prior lines of therapy (100% with prior CDK4/6 inhibitors, 80% with prior fulvestrant and 78% with prior chemotherapy)123. ARV-471 was well tolerated across dose levels, with nausea (27%) and fatigue (20%) being the only TRAEs reported in ≥20% of patients, and no dose-limiting toxicities or grade ≥4 TRAEs123. Preliminary data showed dose-related increases in pharmacokinetic parameters for total daily doses from 30 to 500 mg123. Clinical proof-of-concept for the mechanism of action of ARV-471 was confirmed by robust ER degradation (up to 89%) shown by quantitative ER immunofluorescence in post-treatment tumour biopsy samples; ER degradation occurred regardless of ESR1 mutation status with a median value of 67% across dose levels (FIG. 3c). This initial data set also revealed encouraging clinical activity in patients with ER+ breast cancer. The clinical benefit rate (rate of confirmed complete or partial response or stable disease lasting at least 24 weeks; the primary study end point) in 47 evaluable patients was 40% (95% CI 26%–56%)123. In all, three evaluable patients had confirmed partial responses (FIG. 3d), and tumour shrinkage was seen across dose cohorts.

The phase II cohort expansion portion (VERITAC) of this phase I/II trial is evaluating two doses of ARV-471 (200 mg and 500 mg once daily) based on the safety, pharmacokinetic and efficacy data from the phase I portion, and the first data set was presented in December 2022124. As of the 06 June 2022 data cutoff, 71 patients with ER+/HER2− advanced-stage breast cancer and a median of 4 prior lines of therapy (100% with a prior CDK4/6 inhibitor, 79% with prior fulvestrant, and 73% with prior chemotherapy [45% in the metastatic setting]) received oral ARV-471 (35 at the 200 mg dose and 36 at the 500 mg dose) 124. The clinical benefit rate was 37.1% (95% CI 21%–55%) in 35 evaluable patients at the 200 mg once daily dose and 38.9% (95% CI 23%–57%) in 36 evaluable patients at the 500 mg once daily dose124. The clinical benefit rate in patients with mutant ESR1 was 47.4% (95% CI 24%–71%) in 19 evaluable patients in the 200 mg dose cohort and 54.5% (95% CI 32%–76%) in 22 evaluable patients in the 500 mg dose cohort124. Two patients (one in each dose cohort) had a confirmed partial response124. Median progression-free survival was 3.5 months (95% CI 1.8–7.8) in the 200 mg dose cohort and 5.5 months (95% CI 1.8–8.5) in the subgroup with mutant ESR1 treated at that dose level; progression-free survival data were not mature in the 500 mg dose cohort124. In VERITAC, ARV-471 had a manageable safety profile, and most TRAEs were grade 1/2124. The most common TRAEs were similar between dose cohorts; the only TRAE that occurred in ≥20% of patients was fatigue (34% overall)124. In the 500 mg cohort, treatment-emergent AEs led to dose reductions in three patients and to discontinuation in two patients; in the 200 mg cohort, treatment-emergent AEs led to discontinuation in one patient, with no dose reductions required due to AEs124. On the basis of comparable efficacy, favourable tolerability, and robust ER degradation (median 69% [range 28%–95%] in evaluable patients across the phase I/II study), ARV-471 200 mg once daily was selected as the phase III monotherapy dose and is being evaluated in a randomized trial versus fulvestrant in patients with ER+/HER2− advanced-stage breast cancer who had received one line of prior CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy in combination with endocrine therapy (NCT05654623)124.

NX-2127 clinical data

The first presentation of results from the phase 1 study of the BTK degrader NX-2127 reported data from 36 patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies (of whom 23 had chronic lymphocytic leukaemia [CLL]) who were treated with oral doses of 100 mg, 200 mg, or 300 NX-2127 mg once daily with a data cutoff date of 21 September 2022125. The median number of lines of prior therapy was four in the overall population (5 in the subgroup with CLL), 86% had received a prior BTK inhibitor (100% in the subgroup with CLL), and 35% had a BTK inhibitor resistance mutation (48% in the subgroup with CLL). Treatment-emergent AEs reported in ≥20% of patients were fatigue (53%), neutropenia (39%), contusion (28%), thrombocytopenia (25%), hypertension (25%), and anaemia (22%)125. There was one dose-limiting toxicity of cognitive disturbance in a patient with CLL treated at the 300 mg once daily dose but a maximum tolerated dose of NX-2127 was not reached125. After a median follow-up of 5.6 months (range 0.3–15.7), 14 of 23 patients with CLL remained on NX-2127 treatment; in 15 evaluable patients with CLL, the overall response rate was 33% (95% CI 12%–62%)125. Treatment with 100 mg once daily NX-2127 in patients with CLL resulted in sustained reduction in BTK levels and decreased levels of CCL4, a marker of B-cell activation125. NX-2127 induced BTK degradation and led to clinical responses regardless of mutation status98,125.

Future directions for protein degraders

Protein degrader development has rapidly advanced since its inception14— from design and refinement of the molecules through medicinal chemistry to evaluation of activity in preclinical experiments to validation in clinical studies (FIG. 2). The reported preclinical data strongly support the specificity of protein degraders for their targets as well as their potency in inhibiting tumour growth compared with small-molecule inhibitors. Moreover, preclinical evidence indicates that protein degraders have activity against resistance mutants that develop following treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Clinical data, albeit sparse, support the efficacy of protein degraders in patients with advanced-stage prostate cancer, breast cancer, and CLL, including those with AR, ER, and BTK resistance mutations, respectively. Particularly noteworthy is the tolerability of protein degraders in patients and the absence of any signal suggesting adverse effects inherently associated with this technology, for example, owing to hijacking of the ubiquitin–proteasome system in general. It will be instructive to see how efficacy and safety results bear out in larger patient populations.

Protein degraders that target the AR, ER, or BTK were logical forerunners for development, given that these proteins have established roles in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer, breast cancer, and CLL, respectively, and approved agents targeting them could serve as benchmarks for preclinical and clinical testing34–37,84,86,87,95. Now that protein degradation and therapeutic activity by the protein degrader modality has been clinically demonstrated with bavdegalutamide, ARV-471, and NX-2127, with others agents following soon behind, a key next step is to determine if this approach will meet the expectations of tenet 1 for protein degraders in the clinic, that is, degradation of classically undruggable targets. This will likely be addressed with data from the first-in-human phase I studies of KT-333, a STAT3 degrader, in patients with relapsed or refractory lymphomas and advanced solid tumours114 and of ASP3082, a KRAS G12D degrader, in patients with advanced-stage KRAS G12D mutant solid tumours111.

The prospect of targeted protein degrader delivery to minimize potential toxicity from systemic delivery is on the horizon. Various targeted delivery systems have now been described, including antibody–protein degrader conjugates126 and protein degraders that can be selectively activated in tumours by either light, folate or reactive oxygen species127–131. In addition, although this Review focuses on protein degraders in development for cancer, the technology might also be used to target proteins involved in the development of other diseases (for example, IRAK4 for autoimmune diseases29 thus delivering the promise of broad therapeutic potential.

Potential challenges for protein degraders

Although protein degraders have shown favourable attributes in both the preclinical and clinical settings, they might be met with certain hurdles as they are more widely used in patients with cancer. One question that has not yet been addressed with clinical data is whether patients might develop resistance to protein degraders. Preclinical reports on this phenomenon are limited, but to date, most instances of protein degrader resistance have occurred via alterations affecting the ubiquitin–proteasome system, for example, loss of function of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, components of E3 ubiquitin ligases, or regulators of the E3 ligase activity (such as the COP9 signalosome), rather than alterations in the target protein132–135. A preclinical study revealed upregulation of the drug efflux pump MDR1 as a mechanism of resistance to protein degraders and suggested that co-administration with MDR1 inhibitors might help overcome this resistance136. Evaluation of patients treated with protein degraders for extended periods will be needed to confirm whether the mechanisms of resistance observed preclinically also occur in the clinical setting.

The ability to design novel protein degraders for other targets and cancer types has limitations inherent to the technology, including the requirement for them to bind to their target protein in a manner that permits them to simultaneously access the intracellular ubiquitin–proteasome machinery. For example, transmembrane protein targets with ligands that generally bind on the extracellular-facing surface, such as GPCRs, cannot physically access the cytosolic ubiquitin-proteasome machinery to drive the protein degrader mechanism of action. Additionally, although protein degraders that target classically undruggable proteins are an area of great interest and potential, the difficulty in identifying a binding site for the degrader should not be underestimated. Technologies such as DEL for protein degraders58, as well as technologies that are complementary to protein degraders (BOX 2), might overcome these obstacles.

Conclusions

Protein degraders have taken a bona fide bench-to-bedside odyssey over the past two decades. The majority of this journey to date has been spent in the laboratory as protein degraders were devised, improved and rigorously tested using in vitro and in vivo systems. Protein degraders entered clinical development just 4 years ago, and the fruition of preliminary clinical data suggesting the potential for protein degraders as treatments for patients with cancer is encouraging and gratifying; additional data from clinical studies of protein degraders are eagerly awaited. Their bespoke design suggests protein degraders might offer substantial promise as therapies for a spectrum of diseases.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

The concept of harnessing the natural, intracellular protein disposal machinery (the ubiquitin-proteasome system) to eliminate disease-causing proteins was proposed more than two decades ago.

Since then, numerous primary papers and review articles have described the mechanistic development of protein degraders and their potential as a new therapeutic approach, including for patients with cancer.

As of January 8, 2023, 18 protein degraders are under evaluation in clinical trials in patients with various solid tumours and haematological cancers, and the first clinical data for these molecules are just now emerging.

Preclinical data that have been disclosed for the protein degraders in clinical development support their target specificity and their potency in inhibiting tumour growth compared with small-molecule inhibitors.

Preliminary data for protein degraders targeting the androgen receptor, the oestrogen receptor, and BTK have shown encouraging clinical activity in patients with prostate cancer, breast cancer, and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, respectively, and results from additional ongoing clinical studies are anticipated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Bloom, of Arvinas, for research and editorial support.

Footnotes

Competing interests

D.C. and K.R.H. are employees and shareholders of Arvinas. C.M.C. is a founder and shareholder of Arvinas, as well as a founder, shareholder and consultant of Halda Therapeutics and Siduma Therapeutics, which support research in his lab.

Peer-review information

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology thanks A. Ciulli; M. Naito; G. Zheng, who co-reviewed with A. Smith; and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Related links

ClinicalTrials.gov: https://clinicaltrials.gov/

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s415XX-XXX-XXXX-X

References

- 1.Savage DG & Antman KH Imatinib mesylate--a new oral targeted therapy. N Engl J Med 346, 683–693, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra013339 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedard PL, Hyman DM, Davids MS & Siu LL Small molecules, big impact: 20 years of targeted therapy in oncology. Lancet 395, 1078–1088, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30164-1 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhong L et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6, 201, doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00572-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neklesa TK, Winkler JD & Crews CM Targeted protein degradation by PROTACs. Pharmacol Ther 174, 138–144, doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.027 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cromm PM & Crews CM Targeted Protein Degradation: from Chemical Biology to Drug Discovery. Cell Chem Biol 24, 1181–1190, doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.05.024 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathijssen RH, Sparreboom A & Verweij J Determining the optimal dose in the development of anticancer agents. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 11, 272–281, doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.40 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovly CM & Shaw AT Molecular pathways: resistance to kinase inhibitors and implications for therapeutic strategies. Clin Cancer Res 20, 2249–2256, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1610 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotow J & Bivona TG Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in NSCLC. Nat Rev Cancer 17, 637–658, doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.84 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cocco E, Scaltriti M & Drilon A NTRK fusion-positive cancers and TRK inhibitor therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15, 731–747, doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0113-0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gebru MT & Wang HG Therapeutic targeting of FLT3 and associated drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol 13, 155, doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00992-1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun TP, Eide CA & Druker BJ Response and Resistance to BCR-ABL1-Targeted Therapies. Cancer Cell 37, 530–542, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.006 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephens DM & Byrd JC Resistance to Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors: the Achilles heel of their success story in lymphoid malignancies. Blood 138, 1099–1109, doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006783 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomatou G et al. Mechanisms of resistance to cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors. Mol Biol Rep 48, 915–925, doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-06100-3 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakamoto KM et al. Protacs: chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1-Cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 8554–8559, doi: 10.1073/pnas.141230798 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hershko A & Ciechanover A The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem 67, 425–479, doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciechanover A, Orian A & Schwartz AL Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis: biological regulation via destruction. Bioessays 22, 442–451, doi: (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nandi D, Tahiliani P, Kumar A & Chandu D The ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Biosci 31, 137–155, doi: 10.1007/BF02705243 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komander D & Rape M The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem 81, 203–229, doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleiger G & Mayor T Perilous journey: a tour of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Trends Cell Biol 24, 352–359, doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.12.003 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alabi S Novel Mechanisms of Molecular Glue-Induced Protein Degradation. Biochemistry 60, 2371–2373, doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00353 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frere GA, de Araujo ED & Gunning PT Emerging mechanisms of targeted protein degradation by molecular glues. Methods Cell Biol 169, 1–26, doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2022.01.001 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua L et al. Beyond Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeric Molecules: Designing Heterobifunctional Molecules Based on Functional Effectors. J Med Chem 65, 8091–8112, doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00316 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gadd MS et al. Structural basis of PROTAC cooperative recognition for selective protein degradation. Nat Chem Biol 13, 514–521, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2329 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bondeson DP et al. Lessons in PROTAC Design from Selective Degradation with a Promiscuous Warhead. Cell Chem Biol 25, 78–87 e75, doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.010 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Douglass EF Jr., Miller CJ, Sparer G, Shapiro H & Spiegel DA A comprehensive mathematical model for three-body binding equilibria. J Am Chem Soc 135, 6092–6099, doi: 10.1021/ja311795d (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buckley DL et al. HaloPROTACS: Use of Small Molecule PROTACs to Induce Degradation of HaloTag Fusion Proteins. ACS Chem Biol 10, 1831–1837, doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00442 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riching KM, Caine EA, Urh M & Daniels DL The importance of cellular degradation kinetics for understanding mechanisms in targeted protein degradation. Chem Soc Rev 51, 6210–6221, doi: 10.1039/d2cs00339b (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneekloth AR, Pucheault M, Tae HS & Crews CM Targeted intracellular protein degradation induced by a small molecule: En route to chemical proteomics. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 18, 5904–5908, doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.114 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bekes M, Langley DR & Crews CM PROTAC targeted protein degraders: the past is prologue. Nat Rev Drug Discov 21, 181–200, doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00371-6 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bond MJ, Chu L, Nalawansha DA, Li K & Crews CM Targeted Degradation of Oncogenic KRAS(G12C) by VHL-Recruiting PROTACs. ACS Cent Sci 6, 1367–1375, doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00411 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou H et al. SD-91 as A Potent and Selective STAT3 Degrader Capable of Achieving Complete and Long-Lasting Tumor Regression. ACS Med Chem Lett 12, 996–1004, doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00155 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burslem GM et al. Targeting BCR-ABL1 in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia by PROTAC-Mediated Targeted Protein Degradation. Cancer Res 79, 4744–4753, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1236 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buhimschi AD et al. Targeting the C481S Ibrutinib-Resistance Mutation in Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Using PROTAC-Mediated Degradation. Biochemistry 57, 3564–3575, doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00391 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azad AA et al. Androgen Receptor Gene Aberrations in Circulating Cell-Free DNA: Biomarkers of Therapeutic Resistance in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 21, 2315–2324, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2666 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson D et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell 161, 1215–1228, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quigley DA et al. Genomic Hallmarks and Structural Variation in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cell 174, 758–769 e759, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.039 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeda DY et al. A Somatically Acquired Enhancer of the Androgen Receptor Is a Noncoding Driver in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cell 174, 422–432 e413, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.037 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao X et al. Phase 1/2 study of ARV-110, an androgen receptor (AR) PROTAC degrader, in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Presented at American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (2022).17 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neklesa T et al. ARV-110: An oral androgen receptor PROTAC degrader for prostate cancer. Presented at American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (2019).259 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrylak DP et al. First-in-human Phase 1 Study of ARV-110, an Androgen Receptor PROTAC Degrader in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Following Enzalutamide and/or Abiraterone Acetate Treatment. Presented at American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting (2020).3500 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snyder LB et al. Discovery of ARV-110, a first in class androgen receptor degrading PROTAC for the treatment of men with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Presented at American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting (2021).43 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang B et al. Development of Dual and Selective Degraders of Cyclin-Dependent Kinases 4 and 6. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 58, 6321–6326, doi: 10.1002/anie.201901336 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nowak RP et al. Plasticity in binding confers selectivity in ligand-induced protein degradation. Nat Chem Biol 14, 706–714, doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0055-y (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Degorce SL et al. Discovery of Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera Molecules that Selectively Degrade the IRAK3 Pseudokinase. J Med Chem 63, 10460–10473, doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01125 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fang Y et al. Progress and Challenges in Targeted Protein Degradation for Neurodegenerative Disease Therapy. J Med Chem 65, 11454–11477, doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00844 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Itoh Y, Ishikawa M, Naito M & Hashimoto Y Protein knockdown using methyl bestatin-ligand hybrid molecules: design and synthesis of inducers of ubiquitination-mediated degradation of cellular retinoic acid-binding proteins. J Am Chem Soc 132, 5820–5826, doi: 10.1021/ja100691p (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bondeson DP et al. Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat Chem Biol 11, 611–617, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1858 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zengerle M, Chan KH & Ciulli A Selective Small Molecule Induced Degradation of the BET Bromodomain Protein BRD4. ACS Chem Biol 10, 1770–1777, doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00216 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buckley DL et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of the interaction between the E3 ligase VHL and HIF1alpha. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 51, 11463–11467, doi: 10.1002/anie.201206231 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galdeano C et al. Structure-guided design and optimization of small molecules targeting the protein-protein interaction between the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase and the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) alpha subunit with in vitro nanomolar affinities. J Med Chem 57, 8657–8663, doi: 10.1021/jm5011258 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winter GE et al. DRUG DEVELOPMENT. Phthalimide conjugation as a strategy for in vivo target protein degradation. Science 348, 1376–1381, doi: 10.1126/science.aab1433 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu J et al. Hijacking the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Cereblon to Efficiently Target BRD4. Chem Biol 22, 755–763, doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.05.009 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]