Abstract

Membraneless organelles (MLOs), also known as biomolecular condensates, can form through weak multivalent intermolecular interactions of proteins and nucleic acids, a process often associated with liquid–liquid phase separation. Biomolecular condensates are emerging as sites and regulatory platforms of vital cellular functions, including transcription and RNA processing. In the first part of this Review, we comprehensively discuss how alternative splicing regulates the formation and properties of condensates, and conversely the roles of biomolecular condensates in splicing regulation. In the second part, we focus on the spatial connection between splicing regulation and membraneless nuclear bodies such as transcriptional condensates, splicing condensates and nuclear speckles. We then discuss key research showing how splicing regulation through biomolecular condensates is implicated in human pathologies such as neurodegenerative diseases, different types of cancer, developmental disorders and cardiomyopathies, and conclude with a discussion of outstanding questions pertaining the roles of condensates and MLOs in splicing regulation and how to experimentally study them.

INTRODUCTION

Pre-mRNA splicing allows the formation of mRNA by removing the introns and joining the exons, a process known as constitutive splicing. Alternative splicing was first demonstrated in 1977, in a study that showed differential splicing of a pre-mRNA into multiple mature mRNAs, each with different exon combinations1,2. We now know that >95% of human genes are alternatively spliced3,4, thereby greatly expanding proteome diversity.

Splicing is carried out mainly by the spliceosome, which recognizes and binds to consensus sequences at the 5’ and 3’ ends of the introns — the 5’ splice site and 3’ splice site, respectively — removes the intron and covalently joins the adjacent exons. Generally, when the sequence of the splice site is very similar to the consensus sequence, the splice site is typically considered “strong” and constitutive splicing occurs. By contrast, when the splice site sequence diverges from the consensus sequence, the splice site is usually considered “weak”, is less efficiently recognized and sub-optimally used by the spliceosome, generating different transcripts through alternative splicing (Fig. 1a). However, in some conditions, “strong” splice sites undergo alternative splicing and, similarly, in some contexts “weak” splice sites are constitutively used. This variability is possible because, in addition to the strength of the splice sites, the binding of trans-acting factors — mostly RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) — to cis-regulatory sequences within the pre-mRNAs also influences splicing outcomes: RBP binding to exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) or intronic splicing enhancer (ISE) sequences favors the exon inclusion, whereas binding to exonic splicing silencer (ESS) or intronic splicing silencer (ISS) sequences favors exon skipping (Fig. 1b). RBP expression levels, activity and intracellular localization also influence splicing outcomes in different contexts (specific tissues or cell types, developmental stages, in health versus disease, etc.). Moreover, splicing often occurs co-transcriptionally5,6, and thus transcription kinetics by RNA polymerase II (Pol II), chromatin structure, nucleosome occupancy and epigenetic marks all regulate splicing outcomes7–12.

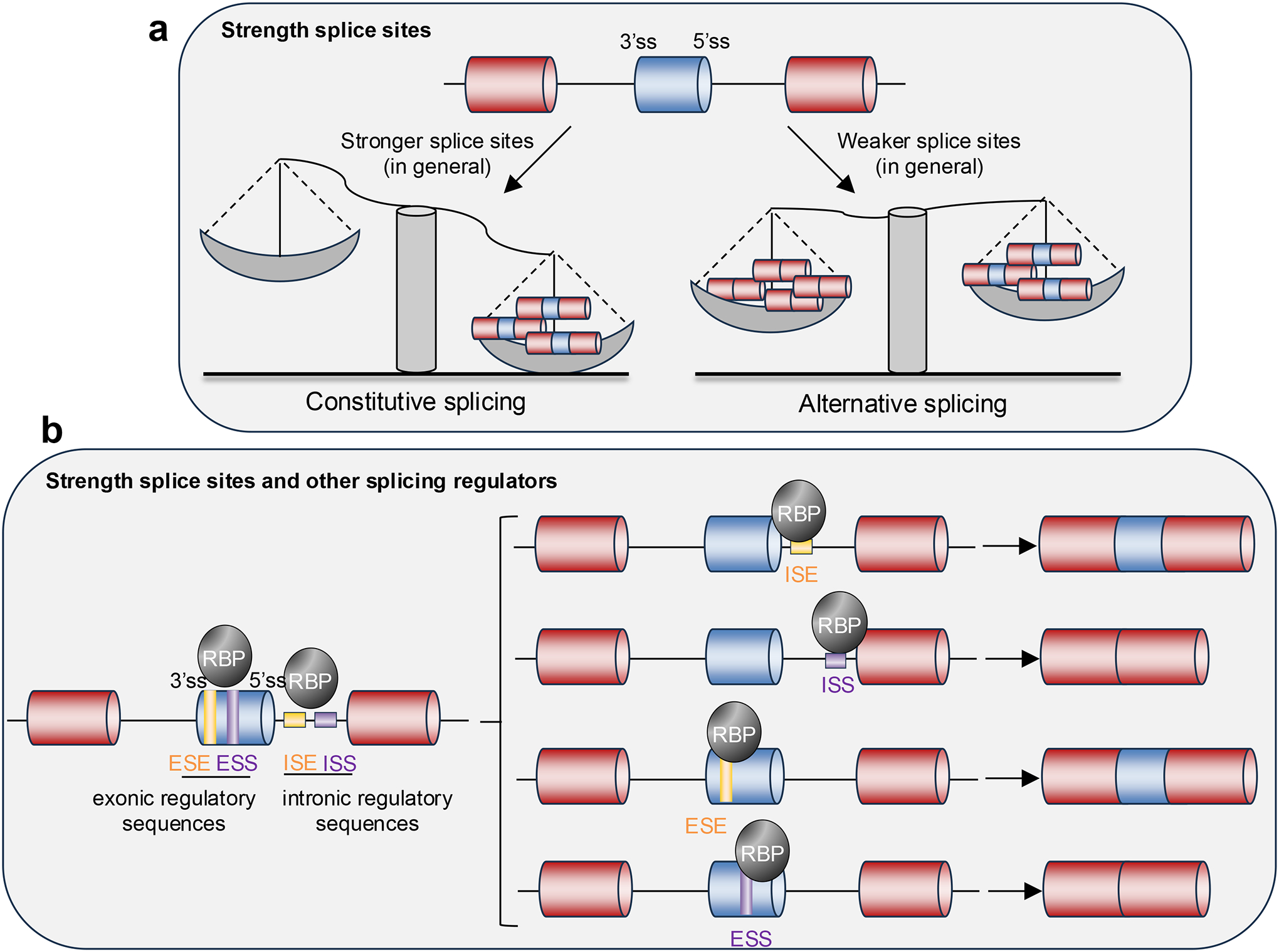

Figure 1. Fundamentals of splicing regulation.

a. The spliceosome (not shown) recognizes and binds to splicing consensus sequences at the 5’ and 3’ ends of the introns, known respectively as 5’ splice site (5’ss) and 3’ss, thereby allowing the removal of the intron and the joining of the adjacent exons. When the sequences of the splice sites are very similar to a consensus sequences, the splice sites are usually considered “strong” and constitutive splicing occurs (left). When the sequences of the splice sites differ from the consensus, the splice sites are often considered “weak” and can be sub-optimally used, resulting in alternative splicing and the formation of different mRNA transcripts (right).

b. In some conditions, “strong” splice sites undergo alternative splicing and “weak” splice sites are constitutively used. This is possible because, in addition to the strength of the splice sites, trans-acting factors (RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and splicing factors) that bind to cis-regulatory sequences within the pre-mRNA influence splicing outcomes: binding to exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) or intronic splicing enhancer (ISE) sequences favors exon inclusion, whereas binding to exonic splicing silencer (ESS) and intronic splicing silencer (ISS) sequences favors exon skipping.

Biomolecular condensates have various functions, and their most prominent role is modulating the rate of biochemical reactions13. Whereas the biochemistry of splicing regulation has been extensively studied, how splicing is spatiotemporally regulated within the cell is less understood. Although splicing has been long associated with certain nuclear bodies, the functional and mechanistic significance of these associations remains unclear. In the past few years, our understanding of the spatiotemporal regulation of splicing within the cell has been reshaped by the emergent concept of biomolecular condensates, which are membraneless organelles (MLOs) that organize cellular components and biochemical reactions14,15 (Box 1). Biomolecular condensates form through weak multivalent intermolecular interactions of proteins and nucleic acids, a process often associated with liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS)14–16. Numerous excellent reviews have covered LLPS14,17,18, biomolecular condensates15,16 and their regulation and function13,19–24. Biomolecular condensates can adopt a broad and continuous spectrum of material properties, from highly dynamic, liquid-like droplets through less fluid gels with reduced dynamicity to solid amyloid aggregates [G]16,25–28 (Box 1). The liquid-like state allows random collision and sampling of reactants in chemical reactions, and is compatible with cellular regulatory functions14. Importantly, disease-causing mutations can facilitate a high-degree of aggregation that underlies several degenerative diseases26,29–31.

Box 1. The formation and characteristics of biomolecular condensates.

Biomolecular condensates formed by specific proteins are assembled through weak, multivalent and dynamic intermolecular interactions. Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) are a prominent feature of proteins that form condensates, especially of human nuclear proteins 16, 34. The lack of strong engagement of intramolecular interactions between amino-acid side chains in IDRs allows them to be readily available to engage in interactions with different molecules18. The driving forces underlying IDR-mediated condensation often include electrostatic interactions, π–π interactions, cation–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions16,34,206. These relatively weak and short-lived interactions promote break–reform cycles between the same and different molecules. Furthermore, the flexibility and the large amplitude of conformational fluctuations of IDRs enhance spatial freedom at the structural level and permit rapid sample interactions with other molecules, thereby forming the basis of the dynamicity and liquidity of the condensates207. In addition to IDRs, structured protein domains that can form multivalent interactions, and other biopolymers (e.g., RNA) in cells are also important mediators of biomolecular condensation16,208.

Material properties of condensates.

Different proteins may form condensates with distinct material and biophysical properties and biological functions. The material properties include liquidity, viscosity, elasticity and porosity, among others. The biophysical properties include molecular dynamics inside the condensates, exchange rate in and out of the condensates, compactness (intermolecular distance) and mobility of the condensates within cells. These condensate properties are determined by the valency, strength and/or stability of the molecular interactions among the condensate components and with the molecules in the dilute phase, which are controlled by the primary sequences and post-translational modifications of the scaffold and client [G] proteins and by other cellular factors, most prominently by chaperones209,210.

Composition of condensates.

Although condensates are non-stoichiometric assemblies and their structure is usually not strongly dependent on precise stoichiometric ratios of its components, the composition of condensates can strongly affect their functions. Based on current models, condensate composition is controlled by both specific interactions and non-specific interactions and is influenced by the stoichiometries and valency of both scaffold and client molecules in the condensates211–213. Specific interactions between IDRs of the nuclear proteins are modulated by charge blocks, and regulate the partition, composition and functionality of co-factors214.

It is important to note that biophysical and composition properties may be heterogeneous inside the condensates, supporting high-order organization and the formation of compartments within condensates, and that such heterogeneity has important implications on the function of the condensates 108, as is very likely to be the case for condensates involved in splicing regulation 112,139

Phase-separation research is very new and evolving; consequently, some concepts are still being defined. There is prominent criticism of overuse of the term ‘phase separation’ for every MLO and of the lack of in vivo evidence that MLOs are crucial for cell biology and development32 (Box 2). Although in this Review we acknowledge some of these controversies, we do not aim to discuss them in detail. Thus, we use the term “biomolecular condensates” to adopt the most neutral, appropriate language. Biomolecular condensates in eukaryotic cells are defined as micron-scale membraneless compartments that function to concentrate proteins and nucleic acids16.

Box 2. On the lack of in vivo evidence that membraneless organelles are crucial for cell biology and development.

One of the main barriers in studying molecular condensation is that there is still no clear in vivo evidence of their functions in cell biology and tissue development. Almost everything we know so far about biomolecular condensates comes mostly from cell culture studies or in vitro biochemical assays. This limitation has been the focus of important discussions in the field32,50,215, which we cannot present in detail here, but we shall mention the key points still open for debate and future investigations.

First, rigorous definitions of phase separation come from physics and chemistry, but they are not in full agreement with how phase separation is understood in life sciences and in physiological contexts32,215. Furthermore, it is not possible to manipulate key parameters that are necessary to validate phase transitions (concentration, temperature, etc.) in vivo leading research to heavily rely on less-rigorous, qualitative descriptions of phase separation215. Those descriptions cannot be considered evidence of phase separation if they lack information about concentration or temperature dependence. Studies in vitro are hugely informative in determining whether a molecule undergoes phase separation, but stating that the same phenomenon occurs in vivo requires quantitative measurements in the endogenous context and at physiological concentrations32,215. In general, the evidence supporting phase separation in vivo is insufficient to discriminate between phase separation and other mechanisms32.

Second, the uncertainty about the veracity of biomolecular condensates and membraneless organelles in vivo stems from overuse of these terms. This strong focus on phase separation, biomolecular condensates and membraneless organelles might be masking a considerable gap in our understanding of alternative mechanisms by which molecules can be accumulated at high local concentration in the absence of a membrane32.

Third, determining condensate function is difficult because condensates are transient, and their complex composition makes them difficult to reconstitute45. Phase separation is proposed to facilitate or sequester molecules and reactions, but the in vivo evidence of these functions is weak and subtle owing to lack of adequate tests32.

It is necessary to work on better ways to manipulate protein concentration in vivo other than by overexpression, perhaps by tagging the molecule of interest in its native genomic locus and at endogenous expression levels. Moreover, criteria such as condensate roundness and ability to fuse and high component mobility are not strong-enough evidence of phase separation in vivo. Until better experimental tools are developed, we need to be cautious in data interpretation. Investigating the physiological functions of phase separation within the limitations of tissue and organ environments is an essential future goal.

Many biomolecular condensates in the nucleus are involved in spatiotemporal regulation of gene expression at multiple steps including chromatin structure changes, transcription, splicing and other RNA maturation processes33,34. Most nuclear condensates interact with natural long polymers in the form of RNA, including numerous long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which can function as scaffolds and regulatory platforms of nuclear condensates34. In the context of co-transcriptional splicing, enhancers and promoters provide many binding sites for transcription factors and co-activators to reach a high concentration for forming co-condensates35. As shown in a recent preprint, nascent RNAs from densely transcribed genomic regions attract binding by numerous RBPs in local proximity and thus facilitate the formation of RNA-processing condensates, prominently including nuclear speckles [G]36. Moreover, diverse and dynamic modifications of DNA37, histones38,39 and RNAs40,41 enable complex regulation of nuclear condensation and associated nuclear processes. It should be noted that the mobility and coalescence of nuclear condensates are often restricted by their specific interaction with chromatin, which is largely immobile42, and with RNAs, many of which are tethered to or associated with chromatin. Such restriction helps maintain the distinct identity and function of these condensates 34,151.

In this Review, we discuss the different manners in which biomolecular condensates function in splicing: condensates can organize pre-mRNAs and splicing factors — specific RBPs can condensate at introns or exons — and in this manner actively regulate splicing-site choice and outcomes. Condensates can also serve as dynamic storage and concentration modules for multiple mRNAs and RBPs. Finally, biomolecular condensates can function similar to aggregates that sequester or inactivate splicing factors.

In the following sections, we first discuss the functional roles of biomolecular condensates in splicing regulation. Second, we discuss the spatial connection between splicing regulation, nuclear speckles and genome organization. Third, we comprehensively describe studies that revealed how splicing regulation through biomolecular condensates is implicated in human diseases. Finally, we present open questions on the roles of condensates and MLOs in splicing regulation and suggest how to experimentally study them.

FUNCTIONS OF BIOMOLECULAR CONDENSATES IN SPLICING REGULATION

In this section, we discuss the consequences for splicing of dysregulation of biomolecular condensates. We begin with the molecular basis of RBP-rich condensate formation and then discuss how these condensates are shaped by alternative splicing, and how their formation and biophysical properties regulate splicing.

Roles of RNA-binding proteins and their low complexity domains in phase separation.

RBPs are main regulators of splicing and are enriched in intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) and low complexity domains in comparison to the whole proteome43–46. The capacity of RBPs to undergo phase separation is mainly driven by their IDRs and low complexity domains, by their (often multivalent) RNA-binding domains, and by post-translational modifications that can alter their hydrophobicity, charge and size (Fig. 2a). RNA–RNA interactions also contribute to the formation of RNA–protein condensates47–51. The IDRs and low complexity domains facilitate the reversible concentration of RBPs within biomolecular condensates, where they can either exert their functions or be sequestered from their roles in other parts of the cell. Ultimately, these dynamics affect cytoplasmic mRNA metabolism25,52–54. In the nucleus, RBPs are heavily involved in splicing regulation and their capacity to form biomolecular condensates is emerging as a key modulator of these functions45,55–57 (Table 1).

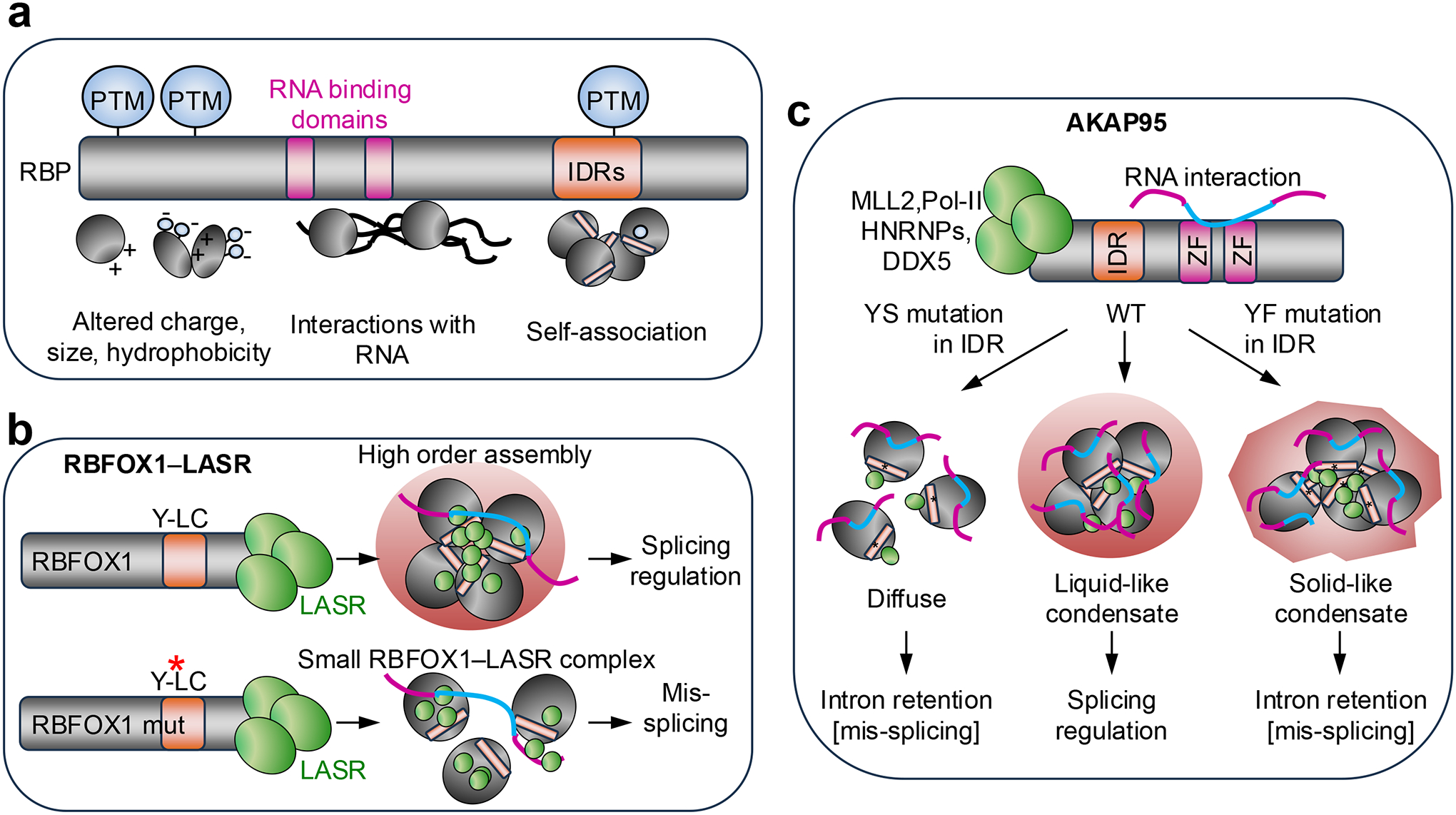

Figure 2. Splicing regulation through phase separation and its physiological relevance.

a. Molecular properties of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that influence their condensation propensity include post-translational modifications (PTMs), which can alter their charge, size and hydrophobicity; RNA-binding domains, which mediate their interaction with RNA; and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which mediate protein–protein associations. Note that IDRs are enriched in PTMs owing to their high accessibility and that these PTMs can in turn regulate condensation.

b. RNA-binding fox-1 homolog 1 (RBFOX1) interacts with the large assembly of splicing regulators (LASR) complex through its C-terminus and together they assemble into organelle-like, high-order protein complexes. A low complexity (LC) sequence contains a Tyr (Y)-rich domain that mediates RBFOX–LASR high-order assembly and is required for splicing activation by RBFOX1 (Ref.56). Mutations (red asterisk) in these Tyr residues block the capacity of RBFOX1 for high-order assembly, but not its interaction with LASR; however, these mutations do prevent proper RBFOX1 functions in splicing regulation56.

c. A-kinase anchoring protein 95 kDa (AKAP95) interacts with the MLL2 complex, RNA polymerase II (Pol II) and different splicing factors; its two zinc-finger domains (ZF) are involved in binding to pre-mRNA introns and splicing regulation67. An IDR allows AKAP95 to form dynamic and liquid-like droplets that function in splicing regulation. Both a Tyr-to-Ser (Y-to-S) mutation that disrupts AKAP95 condensation and a Tyr-to- Phe (Y-to-F) mutation that enhances AKAP95 phase separation but reduces the dynamicity of the condensates significantly impairs AKAP95 activity in regulating splicing and promoting cancer69.

DDX5, probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase; HNRNPs, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins.

Table 1.

Protein condensates that regulate splicing and are associated with disease

| Protein(s) | Features associated with phase-separation capacity | Physiological implications | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKAP95 | The balance between Phe and Tyr residues in the IDR appears to be essential for proper LLPS. | The capacity of AKAP95 to form liquid-like dynamic condensates is required for splicing regulation and tumorigenesis. | 69 |

| HNRNPA and HNRNPD proteins | Gly-Tyr-rich IDR-encoding exons are alternatively spliced in mammals but constitutively included in non-mammals. | Evolution of exon skipping in HNRNPs has expanded their regulatory capacity in mammals compared to non-mammals. | 55 |

| HNRNPA1 HNRNPA2B1 | The IDRs include prion-like domains. | Normally these RBPs self-assemble into fibrils, but this process is exacerbated by mutations within the prion-like domains in ALS and in multisystem proteinopathies. | 31 |

| HNRNPDL | An Arg-rich IDR (N-terminus) and a Tyr-rich IDR (C-terminus). | Both IDRs mediate phase separation, but the Tyr-rich IDR has a stronger effect. Mutations in this domain cause LGMD. | 79 |

| HNRNPH1 | LC1 domain. | LC1 influences interaction with RBPs and roles in splicing regulation. | 57 |

| RBFOX1 | Low complexity Tyr-rich domain within the CTD. | The low complexity domain mediates high-order assembly of RBFOX1 and LASR and is required for the capacity of RBFOX1 to activate exon inclusion. | 56 |

| MeCP2 | Methyl-CpG-binding domain and an intervening domain mediate binding and co-condensation with RBFOX proteins. | Rett-syndrome-causing mutations in MeCP2 disrupt its condensation with RBFOX proteins and result in mis-splicing of synaptic plasticity transcripts. | 171 |

| TDP43 | A Gly-rich low complexity domain encoded by exon 6 (C-terminus) | This low complexity domain facilitates TDP43 nuclear aggregation and functions in splicing regulation, and is absent in ALS, causing TDP43 to pathologically accumulate in the cytoplasm. | 87 |

| USP42 | Positively-charged C-terminal IDR | USP42 forms condensates to regulate splicing that support cancer growth. | 174 |

| RBM10 | Unclear, but the V354M mutation in the RNA-recognition motif enhances RBM10 condensation | RBM10 regulates alternative splicing required for cell proliferation and apoptosis, and is frequently mutated in cancers with splicing dysregulation. The V354M mutation is found in colon cancer, and germline mutations cause TARP syndrome. | 178,179,183,193 |

| WASP | Unclear, likely multiple IDRs | WASP forms co-transcriptional splicing condensates with SRSF2 and Pol II. WASP deficiency alters the properties of these condensates and their function in gene expression, thereby contributing to Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. | 158 |

| RBM20 | Likely RNA-binding domains and IDRs | RBM20 normally forms nuclear splicing foci that mediate alternative splicing regulation. Serine-arginine-domain mutants mis-localize to the sarcoplasm and form aberrant condensates that sequester biomolecules, causing cardiomyopathy. | 185,187,188 |

AKAP95, A-kinase anchoring protein 95 kDa; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CTD, C-terminal domain; HNRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; IDR, intrinsically disordered region; LASR, large assembly of splicing regulators; LC1, low complexity 1; LGMD, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy; LLPS, liquid–liquid phase separation; Pol II, RNA polymerase II; RBFOX1, RNA binding fox-1 homolog 1; SRSF2, serine-arginine rich splicing factor 2; TDP43, TAR DNA-binding protein 43; USP42, ubiquitin specific peptidase 42; MeCP2, methyl-CpG-binding protein 2; RBM10, RNA-binding motif protein 10; WASP, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (HNRNPs) constitute a large family of RBPs involved in multiple aspects of nucleic acid metabolism, including alternative splicing, mRNA stability, transcription, and translation regulation in health and disease58. The low complexity domains of HNRNPs and other RBPs can favor the formation of liquid-like droplets or amyloid-like polymers through phase separation25,59–62 (Table 1). Cryo-electron microscopy revealed the structures of the amyloid fibrils formed by low complexity domains of HNRNPA1 and HNRNPA2 (Ref.63,64). HNRNPH1 contains DNA-recognition motifs at its N-terminal half and two C-terminal low complexity domains (LC1, LC2)57. HNRNPH1 phase separation through its LC1 domain influences its interaction with other RBPs and its functions in alternative splicing57. By contrast, the LC2 domain is not necessary for phase separation, but is required for aberrant transcription activation of fusion oncoproteins during cancer transformation57. Thus, distinct low complexity domains might confer different functions to HNRNPH1 (Ref.57).

Another important family of RBPs involved in splicing regulation is the RNA-binding fox-1 homolog (RBFOX) proteins (RBFOX1, RBFOX2 and RBFOX3). RBFOX proteins regulate splicing during embryonic development and postnatally in the brain, heart and muscle65. Through its C-terminal domain (CTD), RBFOX1 interacts with a protein complex known as large assembly of splicing regulators (LASR)66, which is essential for its functions in splicing regulation56. A Tyr-rich low complexity domain within the CTD mediates RBFOX1–LASR high-order assemblies and is required for splicing activation by RBFOX1 (Ref.56) (Fig. 2b; Table 1). Mutations in these Tyr residues block the high-order assembly of RBFOX1, but not its interaction with LASR; however, these mutations abolish proper RBFOX1 functions in splicing regulation, suggesting a link between RBFOX1 capacity to form high-order assemblies and its function in splicing56 (Fig. 2b).

A-kinase anchoring protein 95 kDa (AKAP95; also known as AKAP8) is involved in different nuclear processes including transcription and splicing regulation67,68. Through its first 100 residues, AKAP95 interacts with the MLL2 (also known as KMT2D) complex, Pol II and different splicing factors, while its two zinc-finger domains bind to pre-mRNA introns and thus are involved in splicing regulation67,68 (Fig. 2c; Table 1). An IDR comprising residues 101–210 allows AKAP95 to form dynamic, liquid-like droplets that have an essential role in regulating splicing and supporting tumorigenesis69 (Fig. 2c; Table 1).

In summary, it is becoming clear that the organization and activation of RBPs within condensates is a crucial layer of splicing regulation. Interestingly, alternative splicing on its own can influence phase separation, thereby forming a feedback regulatory mechanism.

Condensate regulation by alternative splicing.

Alternative splicing of RBPs can influence their ability to undergo phase separation and, thus, their control of splicing decisions. IDRs are not constrained by a specific fold and are, therefore, very tolerant to mutations70,71, which has facilitated both their expansion and evolution72–74. Alternatively spliced exons are significantly enriched in encoding IDRs75–78, prompting the hypothesis that splicing regulation of exons encoding IDRs has contributed to the complexity of higher organisms by remodeling protein–protein interaction networks and signaling pathways55. Almost all HNRNPA and HNRNPD proteins contain Gly-Tyr-rich IDRs that are encoded by exons that are constitutively included in transcripts in non-mammals but alternatively spliced in mammals55 (Fig. 3a). In mammals, those exons can be included or skipped and thus fine tune the capacity of these RBPs to form biomolecular condensates55. Base-pairing between sequences that include the branch point, the polypyrimidine tract and parts of the acceptor sequence adjacent to the alternative exons results in masking these crucial regulatory elements and thus induces exon skipping55. Therefore, these intra-molecular RNA interactions control mammalian-specific alternative splicing in these HNRNPs55. Differential inclusion of the alternative exons modulates the formation of biomolecular condensates of HNRNPs through Tyr multivalency which, in turn, globally regulates splicing outcomes and thus expands gene regulation capacity55.

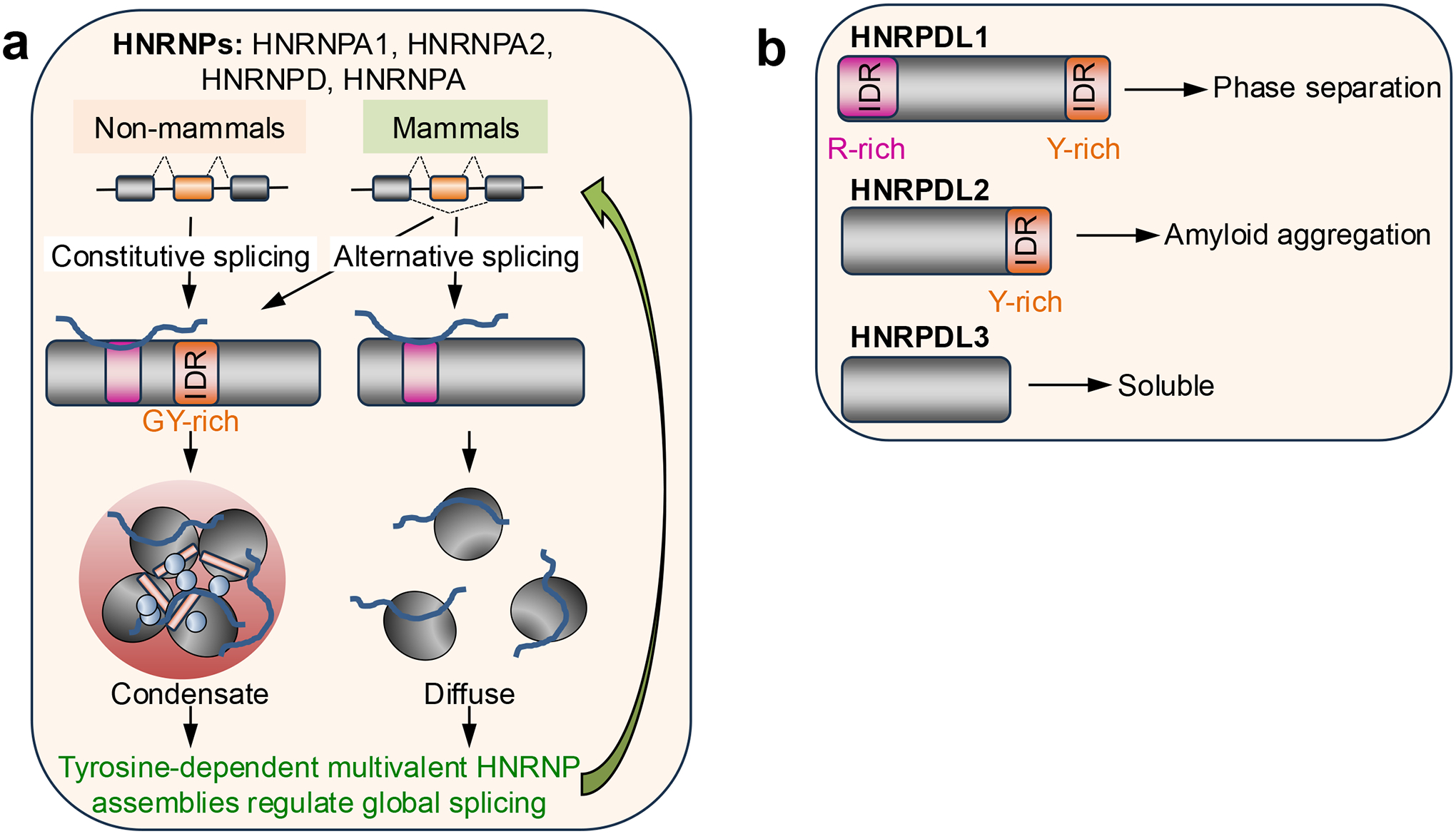

Figure 3. Regulation of condensate formation and properties through alternative splicing.

a. Most heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A (HNRNPA) and HNRNPD proteins contain Gly-Tyr (GY)-rich intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) that are encoded by exons that are constitutively spliced in non-mammals, but alternatively spliced in mammals55. In mammals, those exons can be included or skipped and, in this way, fine-tune the propensity of these RNA-binding proteins to form biomolecular condensates and expand their capacity to regulate gene expression.

b. HNRNPD-like (HNRNPDL) has three splice isoforms, which differ in the presence or absence of an Arg (R)-rich IDR at the N-terminus and a Tyr (Y)-rich IDR at the C-terminus. HNRNPDL1 includes both IDRs and can undergo phase separation; HNRNPDL2 only includes the Y-rich IDR and forms amyloid aggregates; and HNRNPDL3 lacks both IDRs and is soluble79–82.

c. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43) is encoded by the TARDBP gene. The full-length TDP43 mRNA isoform includes the entire exon 6 which contains a stop codon. The full length protein (TDP43-fl) contains a Gly (G)-rich low complexity (LC) domain at the C-terminus, which facilitates nuclear aggregation and mediates its functions in splicing regulation87. Usage of the same 3’ splice site (3’ss) than the TDP43-fl but two alternative 5’ splice sites (5’ss) within exon 6 before the stop codon gives rise to two short TDP43 isoforms (TDP43-s1 and TDP34-s2) that include only a small portion of exon 6 and the entire exon 7 within their coding sequence. Therefore, the C-termini of TDP43-s1 and TDP34-s2 lack the Gly-rich low complexity domain present in TDP43-fl, but includes a putative nuclear export signal (NES) not found in TDP43-fl87. Thus, the short TDP43 variants aggregate in the cytoplasm, where they sequester TDP43-fl, and lack splicing regulation capacity.

NLS, nuclear localization signal.

In addition to the capacity to undergo phase separation, alternative splicing can fine-tune the propensity of RBPs to aggregate. HNRNPD-like protein (HNRNPDL) has three splice isoforms, which differ in the presence or absence of an Arg-rich IDR (at the N-terminus) and a Tyr-rich IDR (at the C-terminus). Following alternative splicing, when both IDRs are present, the resulting protein — HNRNPDL1 — can undergo phase separation; when only the Tyr-rich IDR is present, the resulting HNRNPDL2 is likely to form amyloid aggregates; and when both IDRs are absent, the resulting HNRNPDL3 is soluble79–82 (Fig. 3b). Mutations of the highly conserved HRNPDL1 D378 residue (D378H and D378N; or D259H and D259N in HNRNPDL2(Ref.83).), in the Tyr-rich IDR, cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy [G] (LGMD)84–86 by reducing the solubility and accelerating the aggregation of the protein79. Although this evidence suggests a genetic loss-of-function, the exact mechanisms by which these mutations contribute to LGMD phenotypes and their impact on splicing regulation are unclear.

HNRNPDL2 is the predominant isoform expressed in human tissues80. Cryo-electron microscopy has recently revealed that full-length HNRNPDL2 amyloid fibrils are stable, non-toxic, and can bind nucleic acids83. The amyloid core consists of a single glycine-tyrosine-rich and highly hydrophilic filament, and the RNA-binding domains form a solenoidal coat around the amyloid core83. Interestingly, the amyloid fibril core is encoded by HNRNPDL2 alternative exon 6, which is absent in the soluble HNRNPDL3 isoform, indicating that alternative splicing controlling HNRNPDL assembly (through inclusion or skipping of exon 6) expands the functional diversity of HNRNPDL83.

TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43), which is encoded by the gene TARDBP, is another RBP whose aggregation is influenced by alternative splicing. The full-length TDP43 mRNA isoform includes the entire exon 6 which contains a stop codon. The full length protein (TDP43-fl) contains a Gly-rich low complexity domain at the C-terminus, which facilitates its nuclear aggregation and splicing functions87 (Fig. 3c; Table 1). Usage of the same 3’ splice site than the TDP43-fl but two alternative 5’ splice sites within exon 6 before the stop codon gives rise to two short TDP43 isoforms (TDP43-s1 and TDP34-s2) that include only a small portion of exon 6 and the entire exon 7 within their coding sequence. Therefore, the C-terminus regions of TDP43-s1 and TDP34-s2 lack the Gly-rich low complexity domain present in TDP43-fl, but include a putative nuclear export signal not found in TDP43-fl87. Owing to these characteristics, TDP43-s1 and TDP34-s2 accumulate in the cytoplasm where they form aggregates that sequester TDP43-fl through N-terminal interactions, and lack splicing regulation capacity (Fig. 3c). The short TDP43 forms accumulate in neurons and glia cells of individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and their pathological upregulation is mediated by neuronal hyperexcitability87.

The cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 4 (CPEB4) regulates translation of specific mRNAs by modulating their poly(A) tails. The neuron-specific CPEB4 isoform includes the alternatively spliced microexon 4 (24 nucleotides), but low levels of inclusion of this microexon causes idiopathic autism spectrum disorder (ASD)88 or schizophrenia89. CPEB4 forms condensates driven by homotypic interactions among clusters of aromatic amino acids (especially His), and the microexon 4-encoded 8 residues engage in heterotypic intermolecular interactions that compete with the homotypic interactions to regulate the reversibility of the condensates. As shown in a recent preprint, skipping of microexon 4 leads to irreversible CPEB4 aggregation that cannot be dissolved upon neuron depolarization, and alters CPEB4 activity in translation regulation of key targets including ASD-risk transcripts90. This is a striking example of how tissue-specific alternative splicing ensures crucial protein activity through regulating condensate properties.

Alternative splicing of kinases can also influence condensation and contribute to feedback loops or splicing changes. For example, CDC like kinase 1 (CLK1) is one of the two main kinases that phosphorylates serine-arginine-rich splicing factors (SR proteins), leading to their localization in the nucleus. CLK1 is itself regulated by alternative splicing through the action of SR proteins and this regulation affects the production of functional CLK1 (versus truncated non-functional proteins or transcripts that undergo nonsense mediated decay). Hyper-phosphorylation of SR proteins leads to the dispersion of nuclear speckles and the release of stored splicing factors that ultimately control global splicing of genes, including those involved in the hypoxia response91–95.

In conclusion, alternative splicing of RBPs influences their capacity to undergo phase separation, and in this manner influences their functions as splicing factors, and may greatly enhance the regulatory capacity of RBPs in mammals. However, dysregulation of these regulatory networks has the potential to promote neurodegenerative diseases, muscular disorders and psychiatric conditions.

Formation of nuclear condensates regulates splicing.

In this subsection we discuss the mechanisms by which RBPs regulate splicing by organizing dedicated condensates.

Phase separation of the essential splicing factor U2AF65 along with repetitive, pyrimidine-rich RNA may contribute to the selection of specific splice sites96. U2AF65 and its related protein CAPERα (also known as RBM39) show cooperative binding to splicing factor 3b subunit 1 (SF3B1). U2AF65 forms liquid-like condensates through its SR-rich domain, and condensation is greatly enhanced by the assembly of U2AF65, CAPERα and SF3B1 together with repetitive pyrimidine-rich RNAs. Depletion of U2AF65 or CAPERα resulted in enhanced inclusion of alternative exons preceded by repetitive pyrimidine-rich sequences in the target RNAs96. The authors reason that when the levels of U2AF65 or CAPERα are reduced, the long pyrimidine-rich regions remain preferentially bound and spliced by U2AF65 owing to their ability to enhance U2AF65 condensation relative to pyrimidine-poor regions. Future in vivo characterizations of U2AF65 or CAPERα condensates and their binding at transcripts with different pyrimidine features could provide more-direct evidence to this interesting model of how condensation of a splicing factor may influence splice site choice.

Serine/arginine repetitive matrix 2 (SRRM2) and SON DNA- and RNA-binding protein (SON) are scaffold proteins essential for the formation of nuclear speckles97. SRRM2 regulates alternative splicing, especially by facilitating the inclusion of cassette exons flanked by short introns and weak splice sites98. SRRM2 IDRs mediate the formation of condensates, which is important for regulating most but not all SRRM2-mediated alternative splicing98. It is unclear what features of the transcripts — the exon–intron junction sequence or RNA structure — determine whether their alternative splicing depends on SRRM2 condensation. More mechanistic insight will be gained by determining how SRRM2 condensation controls the formation of nuclear speckles and their properties and structural organization.

An important question is how RBP condensation regulates splicing at the molecular level. Condensates provide dynamic micro-compartments that selectively recruit specific molecules, thereby generating local enrichment of splicing regulators and substrates. This selective compartmentalization effectively reduces the search space required for molecules to find their interacting partners, and decreases their interactions with molecules that are irrelevant or harmful for splicing. Nuclear condensates including those related to splicing may have internal structures that coordinate the spatial distribution of splicing factors and their RNA substrates to regulate splicing (see below).

Recent work has shed light on the mechanism through which RBP condensation may control RNA binding, a prerequisite for splicing regulation99. Quantitative analysis of the condensation capacity of TDP43 CTD mutants in vitro and in cells was correlated with their RNA-binding capacity, and revealed that changes in condensation capacity have differential effects on TDP43 binding to RNA depending on sequence features99. Reduced propensity for condensation selectively affects TDP43 binding to RNA regions that tend to be >100 nucleotides-long and contain dispersed UG-rich motifs, and impairs 3’ end processing of the transcripts 99. It is possible that the splicing of diverse RNAs is also differentially regulated by condensation of TDP43 (and other RBPs). The sequence and likely secondary structure100 of the target RNAs can determine whether and to what extent condensation propensity has a role in their binding and processing by RBPs. This model helps explain other findings, for example that TDP43 phase separation is dispensable for its splicing activity on a few tested targets101 and for repressing certain cryptic exons102. An important difference exists between the TDP43 mutants study99 and the U2AF65 study discussed above96. In the TDP43 mutants’ study99, the activities on the RNA sites normally bound by the TDP43 condensates are selectively affected when the capacity for condensation is perturbed. In the U2AF65 study96, the condensate-bound sites remain preferentially protected from splicing impairment when the overall protein level is reduced, indirectly suggesting an advantage to being able to form condensates at those sites.

Biophysical properties of nuclear condensates that regulate splicing.

Condensates are not simple binary on-off switches of protein states or functions. Splicing activity is likely influenced by numerous physicochemical properties of the condensates beyond their formation and disruption. Recent studies have investigated how the biophysical properties of condensates regulate splicing, with important biological consequences.

The dynamic biophysical properties of AKAP95 condensates control its activity in regulating of both constitutive and alternative splicing69 (Table 1). The Tyr-to-Phe mutation in the IDR enhances AKAP95 aggregation and hardens its condensates both in vitro and in cells69 (Fig. 2c). This altered material state is reflected experimentally by reduced fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, reduced diffusion69 and reduced intermolecular distances103 in the condensates. This mutation significantly impairs AKAP95 activity in regulating splicing, including intron removal, and alternative splicing, and in supporting tumor growth69. This study highlights the requirement for RBP condensates with proper biophysical features for controlling their biochemical functions in splicing regulation.

In response to metabolic changes, arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS) can modulate splicing by interacting with SRRM2 in the nucleus and impeding its mobility104. Depletion of ArgRS or arginine enhanced the rates of recovery after photobleaching of endogenous SRRM2 and depletion of SRRM2 and ArgRS led to mis-splicing of a subset of genes in opposite directions104. These results are consistent with the notion that high SRRM2 mobility (following ArgRS depletion) favors SRRM2 activity in alternative splicing. These splicing alterations lead to the expression of different protein isoforms, which might influence cellular metabolism and peptide presentation to immune cells, ultimately contributing to the cellular response to the inflammation-induced Arg depletion104. Although how ArgRS regulates SRRM2 mobility is unclear, this study has revealed how regulating the properties of the splicing condensates can serve as a response to metabolic changes.

Nuclear speckle proteins are highly enriched in mixed-charge domains, especially those containing Arg residues105. Arg has a crucial role (that cannot be performed by Lys) in condensation of proteins (including many RBPs) containing mixed-charge domains and in their incorporation into nuclear speckles. The RNA-recognition motif (RRM) of these RBPs synergizes with the mixed-charge domains to promote their specific incorporation into nuclear speckles instead of into the nucleolus. Increasing the negative charge of these mixed-charge domains (by increasing the number of negatively charged amino acids) abolishes their condensation and incorporation into speckles; by contrast, increasing the positive charge enhances protein condensation, slows condensate dynamics and impairs mRNA export from the nucleus105. Although the authors did not test splicing, we speculate that tuning the material properties of speckles through the mixed-charge domains might influence splicing activity, which would be consistent with other studies showing a requirement for proper condensate dynamics for their activity in gene regulation33,69,106.

It is difficult to definitively attribute splicing alterations to changes in a specific property of the condensates, as multiple condensate features are likely connected through their shared physicochemical basis and are often co-affected when one property is perturbed. For example, mutations in a scaffold protein A that enhance homotypic intermolecular interactions (A–A) among the scaffold protein molecules can lead to enhanced condensation and increased local concentration (which may promote reaction rates). However, the same mutations can also lead to a transition of the material property from liquid-like to solid-like (which may reduce reaction rates). Moreover, enhanced homotypic interactions may compete with heterotypic interactions (A–B) of this scaffold protein with different molecules (client proteins), and thus disfavor the incorporation of other components (clients) of the condensates. This possibility has been nicely demonstrated by the “unblending of transcriptional condensates” as a consequence of repeat expansion in the transcription factors107. Therefore, alterations in composition can co-occur with changes in material properties and condensation capacity. It is hard to attribute the effects on a biological activity such as splicing to changes in either of these properties of the condensates.

SPATIAL ORGANIZATION OF SPLICING AND ITS REGULATION THROUGH MEMBRANELESS ORGANELLES

In this section, ‘MLOs’ refers to nuclear bodies that have been linked to splicing, including splicing condensates, nuclear speckles and transcriptional condensates. MLOs often have an internal organization108, which is important for their function109. The structural organization of MLOs is governed by a network of homotypic and heterotypic molecular interactions and influenced by different physicochemical properties of the condensate proteins (e.g., hydrophobicity, micropolarity)109,110. We discuss, from a spatial perspective, how splicing is regulated by the structure of nuclear speckles (and a few other nuclear bodies) and by genome organization.

Regulation of splicing by the internal organization of nuclear speckles.

Nuclear speckles are one of the most prominent nuclear bodies associated with splicing regulation. Multiple biological processes have been linked to nuclear speckles; however, the exact physiological function of nuclear speckles and whether they are sites of active splicing reactions are still under debate111,112. Some studies proposed that nuclear speckles are storage or assembly sites of pre-mRNA processing factors, based on the observation that they do not contain DNA and exhibit only a low level of transcriptional activity inside them111,113. By contrast, others have shown that a group of genes can cluster around nuclear speckles upon activation of their transcription, explaining why these mRNAs colocalize with speckles. In this manner, nuclear speckles might act as hubs that coordinate gene transcription and pre-mRNA processing114–119. A wide variety of studies have suggested that proximity to nuclear speckles is associated with higher gene transcription, co-transcriptional splicing and post-transcriptional splicing (reviewed in120,121).

Nuclear speckles exhibit the key properties of phase-separated MLOs, including liquid-like behaviors122–125 and dynamic exchange of RBPs and RNAs with the surrounding nucleoplasm122–128. Nuclear speckles are highly enriched in polyadenylated RNA, factors required for splicing such as small nuclear ribonucleoproteins and splicing factors (SR proteins such as SRRM1 and SRRM2, SON and others), and cleavage and polyadenylation proteins; therefore, they are good candidates for spatially regulating the splicing reaction120. Some splicing regulators exhibit different localization relative to nuclear speckles: certain SR proteins are enriched within nuclear speckles129,130, whereas certain HNRNPs are not enriched in or are depleted from speckles131,132. SR proteins and HNRNPs often have antagonistic effects on splicing133: whereas SR-binding motifs tend to be more enriched in exons, HNRNP-binding motifs are more enriched in introns134. However, some SR proteins bind also introns and some HNRNPs bind also exons 135,136.

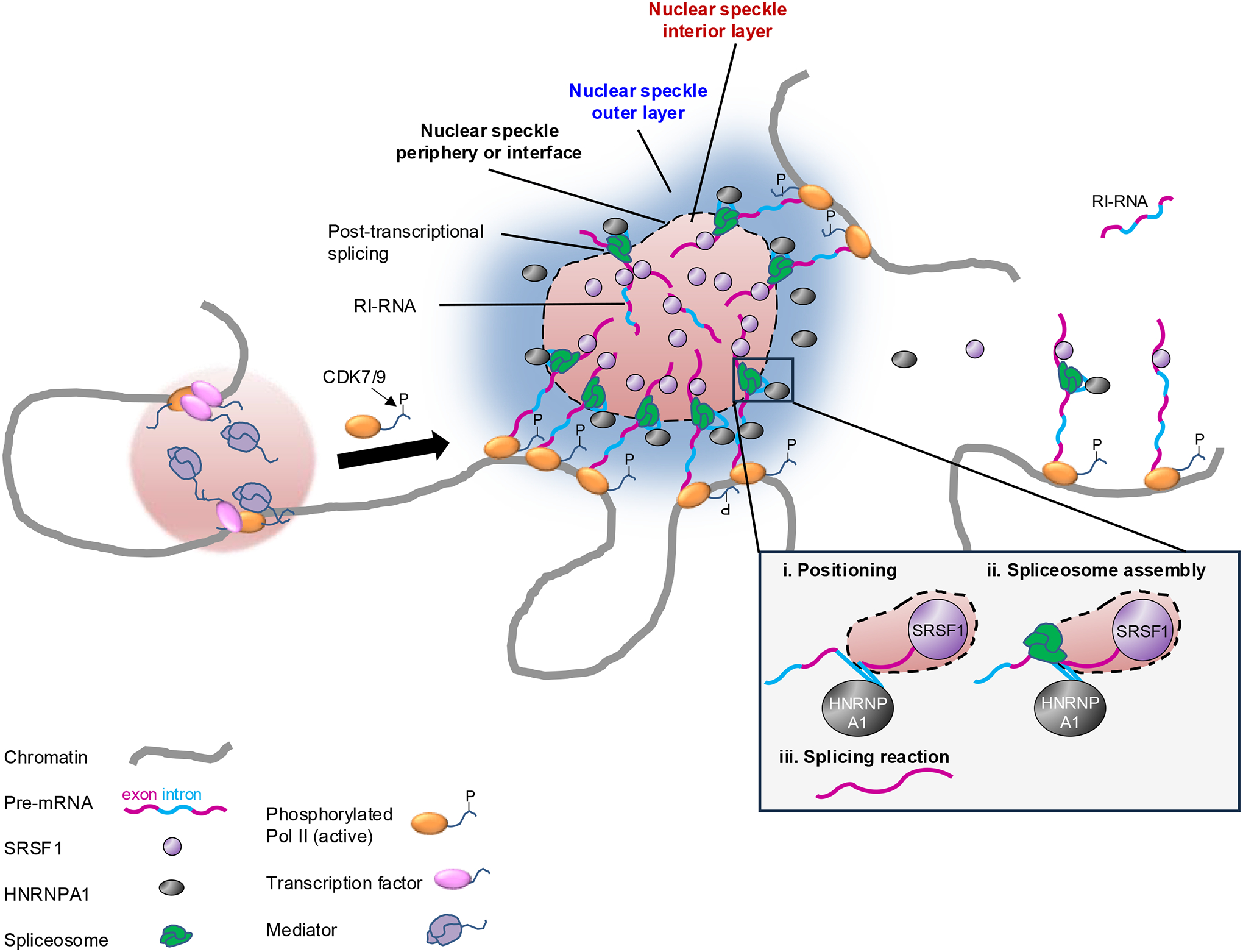

An “interface splicing” model was recently proposed for SRSF1 and HNRNPA1 (Ref. 137). In a simplified view, nuclear speckles contain an inner layer surrounded by an outer layer, and the contact area between them is the speckle–nucleoplasm interface region137 (Fig. 4). According to the model, positioning of RNA within the speckle–nucleoplasm interface coordinates splicing regulation: while exons are sequestered inside the nuclear speckles by SRSF1, introns are bound by HNRNPA1, which is excluded from the inner layer of the nuclear speckles137. In this manner, the exon–intron junctions are positioned at the speckle–nucleoplasm interface, where the spliceosomes are known to be localized112 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Spatial regulation of splicing through nuclear membraneless organelles.

Genomic regions with transcribed genes concentrated in 3D space are in close proximity to nuclear speckles, which support concentration of splicing factors, and the pre-mRNAs of these genes are spliced efficiently; genes that are farther away from speckles (right-hand side of the figure) are spliced less efficiently owing to the reduced local concentration of splicing factors36,120,121,141,153. The “interface splicing” model was recently proposed for serine-arginine (SR) rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (HNRNPA1)137. The outer layer of the speckle is enriched in HNRNPA1, which binds to introns of pre-mRNAs, whereas the interior layer of the speckle is enriched in SRSF1, which binds to exons of the pre-mRNAs137,139. This distribution facilitates the localization of the exon-intron boundary at the interface of the two layers, where active spliceosomes are located and execute the splicing reaction137,139. The model proposes a certain order for the regulation of splicing: first, the RNA is positioned at the nuclear speckle interface based on the recognition of binding motifs by SRSF1 and HNRNPA1; then, the spliceosome assembles; and finally, the splicing reaction takes137 (inset). Some retained-intron RNAs (RI-RNAs) in nuclear speckles can be efficiently spliced post-transcriptionally, whereas RI-RNAs far from speckles (top right corner of the figure) are spliced less efficiently and may undergo decay120. The transition from transcription initiation condensates, which include transcription factors and the Mediator complex, to elongation and co-transcriptional splicing condensates is regulated by phosphorylation (P) of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II (Pol II)156 (left).

CDK7, cyclin-dependent kinase 7.

The model further proposes a certain order for the regulation of splicing: first, the RNA is positioned at the speckle–nucleoplasm interface based on the recognition and binding of splicing regulatory elements by SRSF1 and HNRNPA1; then the spliceosome assembles; and finally the splicing reaction takes place at the interface137 (Fig. 4). Therefore, based on this model, the regulatory elements in the pre-mRNAs first determine the positioning of the pre-mRNAs across the speckle–nucleoplasm interface (exon is recognized by SRSF1 and thus is positioned inside the speckle; intron is recognized by HNRNPA1 and thus is positioned at the speckle–nucleoplasm interface). Only after this positioning, assembly of the spliceosome occurs and the splicing reaction takes place. This temporal order is consistent with what others have observed138.

A recent study (reported in a preprint) supports the interface splicing model using super-resolution imaging139. As predicted by the model, transcripts containing regions enriched in SRSF1-binding motifs and another region enriched in HNRNPA1-binding motifs localized at the speckle–nucleoplasm interface with the SRSF1-binding motif closer to the center of the speckle than the HNRNPA1-binding motif139 (Fig. 4). This specific RNA position and orientation is referred as ‘intra-organelle RNA organization’139. SRSF1 depletion induced the migration of the transcripts towards the speckle periphery, whereas HNRNPA1 depletion caused them to move towards the speckle interior139. Importantly, the strength of the RNA–protein interactions is what drives this intra-speckle RNA orientation, thereby organizing the RNA substrate for the splicing reaction. These results show how the structure of the nuclear speckle may facilitate splicing through organizing pre-mRNA substrates, though more studies are needed to show the functional importance of the organization in regulating splicing activity. Moreover, intra-organelle RNA organization likely exists in other MLOs enriched in certain RBPs but depleted for others139.

The interface of nuclear speckles is not the only location where splicing takes place137: co-transcriptional splicing can occur outside nuclear speckles at nascent transcripts140 and some eukaryotes lack nuclear speckles altogether141. Therefore, the interface splicing model leaves some important questions open. We still do not know how unspliced transcripts localize to the nuclear speckles or how spliced transcripts are released from the nuclear speckles137. Moreover, given that numerous HNRNP proteins undergo phase separation on their own, how are HNRNP phase-separation properties linked to their location outside nuclear speckles and their activities in splicing regulation?

Regulation of splicing by other nuclear bodies.

Several other nuclear bodies, including nuclear stress bodies (nSBs), the perinucleolar compartment and paraspeckles have been implicated in splicing regulation, often for sequestering splicing-regulating factors rather than for being sites of active splicing. The perinucleolar compartment, which is localized at the periphery of the nucleolus, contains several non-coding RNAs and RBPs. The lncRNA pyrimidine-rich non-coding transcript (PNCTR)142 binds to multiple copies of polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1 (PTBP1), an RBP that regulates different aspects of RNA metabolism, including splicing. PNCTR is highly expressed in cancer and is important for tumour growth, likely through sequestering PTBP1 in the perinucleolar compartment and thus bocking its function in regulating splicing of apoptosis genes143.

In response to heat shock, nSBs form around highly repetitive satellite III (HSATIII) lncRNAs, which are transcribed from pericentromeric HSATIII repeats of several human chromosomes144. During stress recovery, CLK1 is recruited to nSBs to re-phosphorylate RSF9, thereby causing accumulation of the intron-retaining RNAs in the nucleus145. During heat stress recovery, nSBs recruit the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA methyltransferase complex to modify HSATIII, which in turn recruits m6A reader proteins, resulting in reduced m6A modification of pre-mRNAs in the nucleoplasm and repression of m6A-dependent splicing146. Therefore, nSBs serve as platforms for splicing regulation in preparing cells for recovery from heat stress.

Paraspeckles form around the lncRNA nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 and are generally thought to regulate cellular processes, including splicing, by acting as a molecular sponge147. However, paraspeckles were recently shown to interact with the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodelling complex and regulate the transcription and alternative splicing of a specific set of genes148.

Chromatin organization and activity is crucial for the spatial organization of discrete nuclear bodies that do not normally fuse together. The localization of different types of nuclear bodies is consistent with their association with different chromatin regions and activity: nuclear speckles and paraspeckles are both associated with actively transcribed chromatin; perinucleolar compartments are associated with Pol I-transcribed lncRNAs at the periphery of the nucleolus; and nSBs are found at specific pericentromeric regions, as described above. Therefore, transcription activity from specific chromatin regions likely governs the formation of distinct nuclear bodies. This notion is supported by the disorganization and fusion of the different nuclear bodies upon transcription inhibition by actinomycin149.

Transcription and splicing converge at membraneless organelles.

Most splicing occurs co-transcriptionally150; thus, discussing splicing regulation in the context of transcription is important.

If we ignore spatial organization and consider the direct recruitment of the splicing machinery by Pol II and/or nascent pre-mRNAs, we might reason that splicing efficiency (ratio of spliced RNA to total transcribed RNA) would be similar for transcripts with different expression levels. However, splicing efficiency increases with gene transcription rate, exhibiting an “economy of scale” behavior153, which reflects the importance of spatial organization in regulating gene expression and suggests that highly expressed genes gain disproportionate allocation of the splicing machinery in the 3D nuclear space. Key components of the spliceosome are more enriched on pre-mRNAs of genes close to nuclear speckles than those far from nuclear speckles, even if transcribed at similar levels36,120,121,141,153 (Fig. 4). Moreover, splicing efficiency is higher for transcripts that are closer to nuclear speckles, which is not merely a correlation because directing a reporter pre-mRNA to nuclear speckles is sufficient to increase the efficiency of its splicing. However, considering how splicing is regulated by the organization of the nuclear speckle, the reporter used in that study may not have had the most optimal configuration to set the exon–intron junction at the speckle interface enriched with spliceosomes137. It would be interesting to investigate how splicing is altered when the intron is directed to the outer layer of the nuclear speckle or when the exon is directed to the interior of the nuclear speckle.

Proximity to nuclear speckles enhances the efficiency of not only co-transcriptional splicing, but probably also of post-transcriptional splicing, as polyadenylated transcripts in the proximity of their genomic loci have better chances to diffuse into the nearby nuclear speckles and get spliced post-transcriptionally than transcripts that are far from the speckles120 (Fig. 4). Proximity to nuclear speckles might be important in determining the fate of the many RNAs that retain or detain introns, known as retained intron RNAs (RI-RNAs) or RNAs with detained introns154. RI-RNAs are either further spliced post-transcriptionally to produce mRNAs for export, or degraded by the RNA exosome 120,155. Proximity to nuclear speckles may allow RI-RNAs to be spliced post-transcriptionally and often alternatively as a rapid regulatory response to developmental cues 120. RI-RNAs that are far from speckles are inefficiently processed and fated for decay120.

What genes are close to nuclear speckles and thus have their pre-mRNAs highly-efficiently spliced? A recent preprint has shown that genes close to nuclear speckles correspond with genomic regions with high Pol II occupancy and high overall transcription activity36 (Fig. 4). Moreover, proximity of a gene to nuclear speckles does not necessarily correlates with the transcription activity at the gene itself, but rather with the overall Pol II occupancy at the genomic region around this gene. This “regional” effect suggests that pre-mRNAs of a gene that is highly transcribed but located in an overall lowly transcribed region may not be spliced very efficiently as this genomic region is likely to be far from nuclear speckles, whereas pre-mRNAs of a lowly transcribed gene located in an overall highly transcribed region may be spliced quite efficiently. Whether gene location near nuclear speckles actually causes splicing efficiency to be high still needs to be tested.

Co-transcriptional splicing condensates.

Transcription initiation is also now thought to involve condensates, specifically ‘transcriptional condensates’, which are composed of transcription factors, co-activators, Pol II and RNA and involve specific and maybe unspecific multivalent interactions. The transition from transcriptional condensates to co-transcriptional splicing condensates is regulated by phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD — during transcription initiation, hypophosphorylated Pol II CTD II interacts with the Mediator complex156 (Fig. 4). The transcription elongation complex can form phase-separated condensates that incorporate and concentrate positive transcription elongation factor b (PTEFB), which otherwise is sequestered in a soluble complex157. Phosphorylated Pol II in the elongation stage loses binding to the Mediator, but gains binding to several splicing factors, effectively switching the Pol II partition from the transcription initiation condensate to the co-transcriptional splicing condensate156 (Fig. 4).

It is unclear whether the elongation condensates157 are identical to the co-transcriptional splicing condensates, but it is reasonable to assume that a strong overlap between them exists. Moreover, there is likely a major overlap between co-transcriptional splicing condensates and nuclear speckles. Co-transcriptional splicing condensates likely form at any actively transcribed gene body regardless of the distance of the gene to other actively transcribed regions 156, whereas nuclear speckles may be considered a special type of co-transcriptional splicing condensates that are prominent hubs where the pre-mRNAs of numerous active genes clustered in 3D space are undergoing splicing. Nuclear speckles also contain post-transcriptional splicing reactions, as discussed above; moreover, they may also store splicing factors not actively engaged in splicing111.

AKAP95 associates with the MLL2 complexes and regulates both transcription68 and splicing67. AKAP95 condensates are likely involved in co-transcriptional splicing regulation. AKAP95 puncta substantially overlaps with SRSF2 signals in nuclear speckles and with the actively transcribing, CTD-phosphorylated Pol II, but not with CTD-unphosphorylated Pol II69. However, higher resolution is needed to better understand the spatial relationship between AKAP95 and the speckle sub-structures. It is worth noting that the immunofluorescence antibody used to detect a nuclear speckles protein SRSF2/SC35, actually detects SRRM2 a key protein in nuclear speckles97. An open question is, if AKAP95 is indeed located exclusively in the outer layer (the periphery) of nuclear speckles, how does AKAP95 condensation influence the condensation and properties of this layer of the speckles to regulate splicing?

The Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) was proposed to directly regulate splicing by forming co-transcriptional splicing condensates at gene bodies158. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome is a primary immunodeficiency disorder. WASP can directly regulate the expression of genes encoding splicing factors, and it forms phase-separated nuclear condensates that include SRSF2, active Pol II and nascent RNAs158. WASP deficiency enhanced SRSF2 mobility at certain nuclear regions, but not in others158, which suggests that WASP aggregates may act as co-transcriptional splicing condensates that regulate transcription and splicing of nascent pre-mRNAs. WASP deficiency alters the properties of these condensates and their function in controlling gene expression, thereby contributing to the development of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome158.

DISEASES ASSOCIATED WITH SPLICING DYSREGULATION THROUGH CONDENSATES

In this section, we discuss how splicing dysregulation through perturbed phase separation promotes neurodegenerative diseases, different types of cancer, developmental disorders and cardiomyopathies.

Neurodegenerative diseases.

Numerous neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases are caused by mutations in specific RBPs and exhibit splicing-relevant aggregation of these RBPs26,29,31,45,159–162.

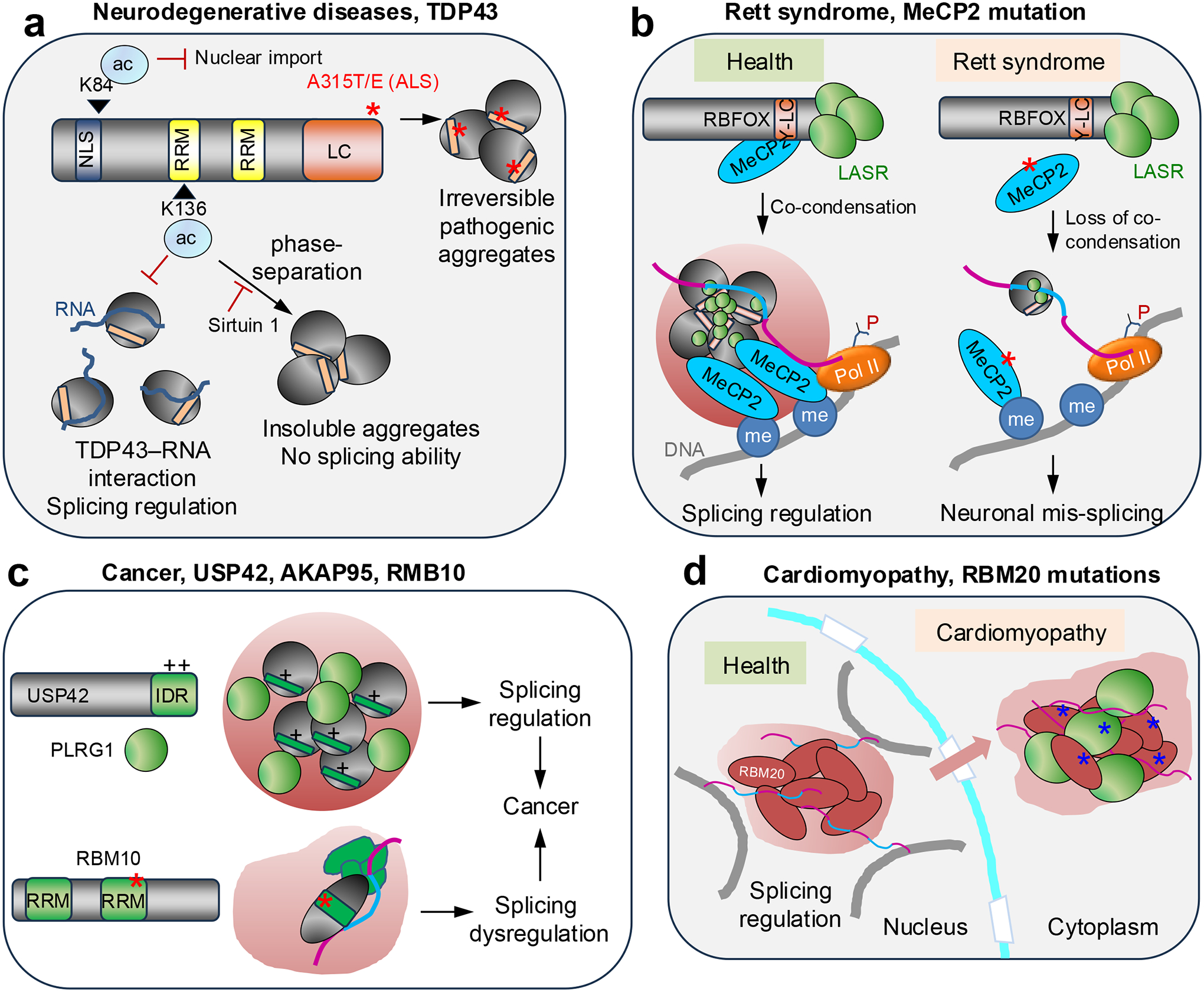

The splicing regulating activity of TDP43 is compromised in ALS and in frontotemporal dementia102,163. TDP43 can aggregate into both reversible stress granules [G] and irreversible neuropathogenic amyloid aggregates (Fig. 5a). The irreversible aggregates were found in humans with ALS, frontotemporal lobal degeneration, Alzheimer disease, Huntington disease and Parkinson disease164–170. The low complexity domain of TDP43 is involved in both types of aggregation. Atomic structures revealed that the TDP43 low complexity domain can form typical steric zipper β-sheets. Six segments within the low complexity domain can form typical steric zipper β-sheets that are characteristic of pathogenic amyloid fibrils and four other segments can form labile amyloid-like interactions found in non-pathological stress granules170. TDP43 mutants (A315T, A315E) present in familial ALS perturb the group of segments, suggesting that these mutations might favor the transition from reversible to irreversible pathogenic TDP43 aggregation170. TDP43 post-translational modifications can also influence its ability to undergo phase separation. Lys84 acetylation reduces nuclear import of TDP43, and Lys136 acetylation impairs its RNA-binding and splicing capabilities165 (Fig. 5a). When TDP43 fails to interact with RNA, its capacity to undergo phase separation through its low complexity domain is enhanced, thereby favoring the formation of pathological, insoluble aggregates that contain phosphorylated and ubiquitylated TDP43165. Interestingly, sirtuin-1 potently deacetylates Lys136 and reduces the aggregation propensity of TDP135.

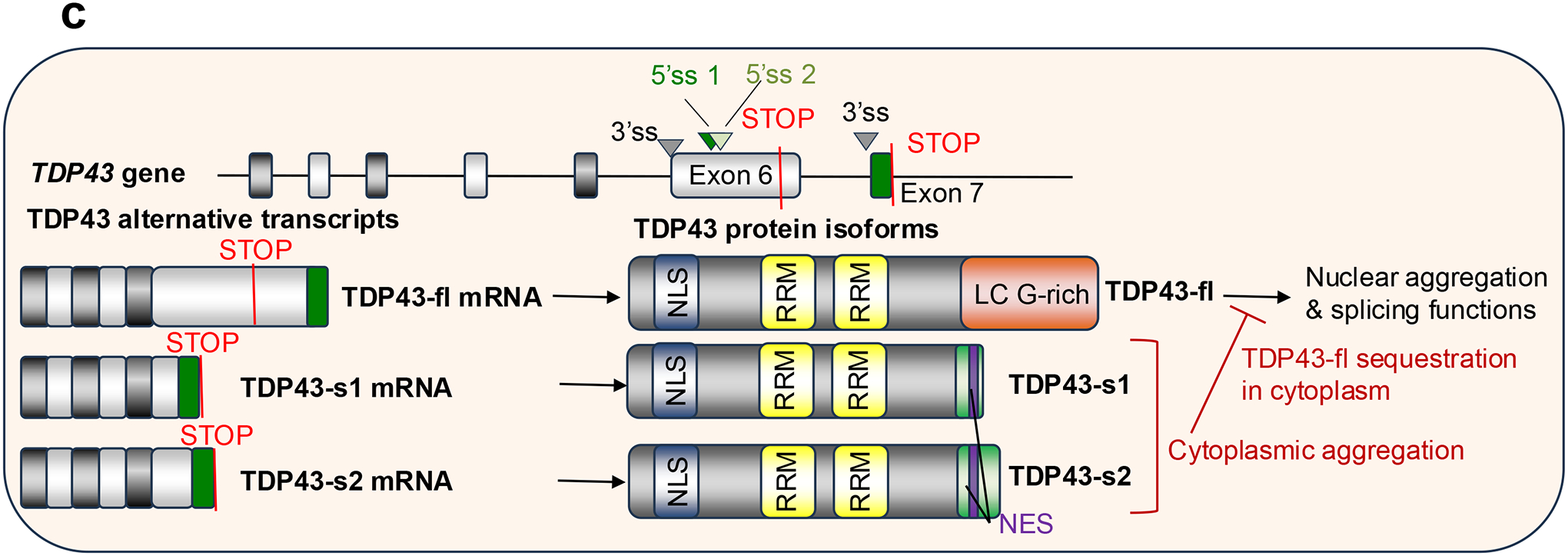

Figure 5. Condensate-mediated splicing regulation in health and disease.

a. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43) mutants (A315T and A315E) present in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) might favor the transition from reversible to irreversible, pathogenic TDP43 aggregation170. Lys84 (K84) acetylation reduces the nuclear import of TDP43. Lys136 acetylation impairs the RNA-binding and splicing capabilities of TDP43, and failure to interact with RNA enhances its capacity to undergo phase separation through its low complexity (LC) domain, thereby favoring the formation of pathological, insoluble TDP43 aggregates 165. Sirtuin-1 deacetylates Lys136, thereby reducing the aggregation propensity of TDP43.

b. Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) normally forms co-condensates and assemblies of the MeCP2–RNA-binding fox-1 homolog (RBFOX1)–large assembly of splicing regulators (LASR) complex that regulate co-transcriptional splicing. MeCP2 mutations (red asterisk) in Rett syndrome reduce co-condensation and impair the binding of RBFOX1–LASR to key neuronal pre-mRNAs, thereby affecting their alternative splicing172,173.

c. A-kinase anchoring protein 95 kDa (AKAP95) and the deubiquitinase ubiquitin specific peptidase 42 (USP42) form liquid-like condensates that regulate splicing programs that support cancer growth69,174. Through its positively charged C-terminal intrinsically disordered region (IDR), USP42 condensation is important for its colocalization with the pleiotropic regulator 1 (PLRG1), a spliceosome component, and nuclear speckles. Depletion of AKAP95, USP42, or PLRG1 markedly reduced cancer cell growth and caused alternative splicing changes in numerous genes including some involved in cell growth69,174. V354M, a colon cancer mutation in an RNA-recognition motif (RRM) of RBM10, enhances RBM10 condensation183, which may explain how this it and related RBM10 mutations affect cancer-associated splicing178,179,183,193.

d. RBM20 forms nuclear foci that regulate alternative splicing of transcripts from multiple chromosomes. Mutations in the serine-arginine-rich domain of RMB20 are associated with cardiomyopathies; they alter its location to the cytoplasm, where it forms condensates that sequester mRNAs and proteins185,187,188.

NLS, nuclear localization signal; Pol II, RNA polymerase II; Y-LC, Tyr-rich low complexity domain.

HNRPNA1, HNRPA2, FUS and TDP43 can be mutated in ALS and the mutations enhance the capacity of these RBPs to undergo phase separation and form pathological aggregates26,29,31,45. Mutations in prion-like domains of HNRNPA2B1 and HNRNPA1 exist in families with multisystem proteinopathies and in one family with ALS31. Multisystem proteinopathies are characterized by inherited degeneration affecting multiple tissues (brain, muscle, motor neuron, bone), but muscle degeneration is a main feature. Normally, these RBPs self-assemble into fibrils, but this process is exacerbated by the mutations in the prion-like domains31. Consequently, excessive aggregation of these RBPs in stress granules occurs, leading to the formation of cytoplasmic inclusions and dysregulation of the functions of the aggregated RBPs31. Although not probed yet, it is widely hypothesized that pathological aggregation of these RBPs that alters their splicing functions is the underlying mechanism of these diseases.

Rett syndrome.

Pathological mutations in methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) disrupt condensation of the RBFOX proteins and result in mis-splicing of synaptic plasticity transcripts171 (Fig. 5b; Table 1). MeCP2 is associated with the RBFOX–LASR complex, which regulates splicing and has an important role in mammalian neuronal development. Although other studies have shown that MeCP2 alone and the RBFOX–LASR complex each forms condensates or higher-order assemblies, MeCP2 and RBFOX proteins exhibit synergistic effects in forming co-condensates 171 Importantly, Rett-syndrome-causing mutations in MECP2 abolish this co-condensation capacity. In mouse models, MeCP2 loss or its Rett-syndrome-causing mutations disrupt the assembly of the MeCP2–RBFOX–LASR complex and impair RBFOX binding to pre-mRNAs, leading to aberrant splicing of neurexin and neuregulin-1 pre-mRNAs, which are crucial for synaptic plasticity 171 MeCP2 has been shown to regulate co-transcriptional splicing by binding to methylated DNA and modulating Pol II elongation172,173. The more recent study 171further shows that the assembly of the MeCP2–RBFOX–LASR complex is disrupted by inhibition of DNA methylation or transcription. Together, these results suggest that MeCP2–RBFOX co-condensates function by locally concentrating splicing factors on chromatin loci to regulate co-transcriptional splicing of nascent pre-mRNAs. Thus, MeCP2 mutations in Rett syndrome disrupt this co-condensation with splicing regulators and cause mis-splicing of neuronal transcripts.

Cancer.

AKAP95 is associated with human cancers and tumorigenesis in part through its activity in regulating splicing. To regulate splicing and cancer, AKAP95 forms condensates with specific liquidity and dynamicity, which suggests that cancer inhibition might be possible by either disrupting or solidifying the liquid-like condensates that promote tumorigenesis69. Similarly, the deubiquitinase ubiquitin specific peptidase 42 (USP42) forms liquid-like condensates that regulate splicing programs and support cancer growth174 (Fig. 5c; Table 1). Through its positively charged C-terminal IDR, USP42 condensation is important for its colocalization with the pleiotropic regulator 1 (PLRG1), a spliceosome component, and with nuclear speckles, and USP42 regulates the morphological properties of these SRSF2 condensates 174 Depletion of USP42 or PLRG1 markedly reduced cancer cell growth and caused alternative splicing changes in numerous genes including some that regulate cell growth. Moreover, both USP42 and PLRG1 are upregulated in lung cancer and high expression levels are associated with low survival174.

Other examples include the Epstein–Barr virus protein EBNA2, which activates transcription through phase separation175. EBNA2 associates with several splicing factors and regulates alternative splicing of transcripts enriched in tumorigenic pathways175. RNA-binding motif protein 5 (RBM5) and RBM10 associate with spliceosomes and control alternative splicing of genes involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis176,177. Somatic mutations of RBM5 and RMB10 occur in several cancers and causes splicing dysregulation178–181. Whereas most of the truncating mutations may be loss-of-function mutations owing to transcript decay or loss of functional domains, certain missense mutations may provide mechanistic insights. For example, the V354E mutation in the RRM of RBM10 is found in lung cancer and actively disrupts RBM10-mediated alternative splicing of NUMB, which is involved in cell proliferation180. As V354E does not affect binding to NUMB mRNA, it remains unclear how it disrupts RBM10 activity other than it might be related to the negative charge of Glu, as similar effects were observed for V354D182. Another missense mutation of RBM10 Val354, V354M, found in colon cancer, has recently been shown to enhance RBM10 condensation in the nucleus183 (Fig. 5c; Table 1). This finding suggests that mutations in RBM10 (and potentially in RBM5) alter its functions in cancer-relevant splicing regulation by changing condensate formation and properties. Clearly, more in-depth studies are needed to link the functions of the mutants and isoforms181,184 of these proteins with their effects on condensation.

Not all these studies have rigorously demonstrated a functional role of condensate properties in mediating the cancer-related phenotypes. The effects on cancer growth and cancer-associated splicing were examined following USP42 depletion, but not by introducing the condensation mutations174. The evidence that EBNA2 regulates splicing of tumor-associated transcripts is weak, as it relies only on treatment with 1,6-hexanediol175, an aliphatic alcohol that can disrupt phase separation, but also numerous other processes. It remains unclear whether the RBM10 V354M mutation contributes to tumorigenesis through splicing dysregulation associated with the altered condensation183.

Cardiomyopathy.

RBM20 regulates tissue-specific alternative splicing by forming nuclear splicing foci that contain multiple loci from different chromosomes185. Common point mutations in RBM20 are associated with congenital dilated cardiomyopathy186. These mutations are often located in the SR-rich domain, and cause defective splicing and re-localization of RBM20 from its normal location at nuclear speckles associated with chromatin, to sarcoplasmic viscous liquid-like condensates analogous to stress granules, which contain cardiac mRNAs and proteins187,188 (Fig. 5d Table 1). It is possible that the disease phenotypes result from both splicing dysregulation (caused by the absence of normal RBM20 nuclear speckles) and sequestration of other proteins into the aberrant cytoplasmic RBM20 condensates.

Nuclear speckleopathies.

Nuclear speckleopathies are a growing class of developmental disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding nuclear speckle proteins, many of which regulate RNA processing189. Some notable examples include ZTTK syndrome, NKAP-related syndrome, TARP syndrome and others189. The common clinical feature of these disorders is a global developmental delay, especially in the brain189. ZTTK syndrome is caused by mutations in SON, a crucial scaffold protein of nuclear speckles97. De novo mutations in SON disrupt splicing of genes required for brain development and metabolism190. NKAP-related syndrome is caused by mutations in NFKB-activating protein (NKAP)191, which associates with multiple splicing-regulating proteins and small nuclear RNAs and controls RNA processing192. TARP syndrome is caused by germline mutations in RBM10 (Ref.193). However, functional connections with splicing (dys)regulation have not been yet well demonstrated for disease mutations of several of these proteins191,194.

CONCLUSION AND OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS

Studies conducted in recent years suggest that splicing reactions are spatiotemporally regulated by condensation of splicing factors and RBPs into nuclear MLOs. The dynamic formation, composition and biophysical properties, and the internal organization of these condensates profoundly affect the efficiency of co-transcriptional and post-transcriptional splicing, and the fate of transcripts that retain introns. Chromatin and genome organization also influence splicing by dictating the position of nuclear speckles as hubs of splicing factors and likely of splicing. Importantly, numerous human diseases are caused by splicing dysregulation associated with altered formation and properties of nuclear condensates.

Despite this advancement in our understanding of the functional relationship between splicing and phase separation, several outstanding questions and challenges remain:

How do we rigorously link condensates to function in splicing regulation? Studies often do not provide very strong, mechanistic evidence to link RBP-condensate formation or properties to splicing function, and it remains challenging to do so, as we still lack a loss-of-function methodology that can dissolve or disrupt specific protein condensates in cells. There is no single, robust method to fully address this question. Instead, a multi-prong approach is required to perturb (induce, reduce, restore, or enhance) specific condensates (and not other molecular properties) and determine the effects on splicing195,196. The most common strategy is to identify and mutate residues that are key for condensation, but it is sometimes difficult to avoid effects on other (including undiscovered) activities of the protein. Mutations in IDRs or post-translational modifications of client proteins may alter splicing outcomes by affecting protein localization and dwell time in the condensate without affecting the properties of the condensate105,197. For IDR-mediated condensation, it is necessary to demonstrate restoration of condensation and splicing functions by replacing the IDR with condensates-forming IDRs of unrelated proteins. Splicing modulation by chemical or optical manipulation198,199 of RBP condensation also strengthen the causal link between condensation and splicing.

How are intricate MLO structures formed and how do they regulate splicing? So far, most studies have focused on homotypic condensates of single purified proteins in vitro, but heterotypic interactions are likely a major driving force in forming and shaping multicomponent condensates in cells200. Moreover, in vitro reconstitution studies of RBP condensation should be performed in the presence and absence of RNA, because the formation, properties and structures of the condensates are likely affected by RNA. Advanced imaging techniques that can capture single-molecule activity in live cells would be instrumental in visualizing these features.

How is splicing regulated through condensates in the context of dynamic changes of genome organization and activity in health and disease? A great example is the formation of RBM20 splicing foci in response to the dynamic genome reorganization occurring during human cardiogenesis185. As many cardiac genes on different chromosomes are activated, some of them gain spatial proximity with each other and form inter-chromosomal contacts that allow coordinated transcription, as well as splicing in the RBM20-containing splicing foci at these contact sites185. Both RBM20 and the RNAs are important for the formation of the splicing foci, exhibiting a complex and dynamic interplay of genome architecture, transcription and splicing185. This evidence also suggests that splicing of these RNAs could be altered by conditions affecting any component involved in the formation of the splicing foci. As discussed185, congenital heart disease-associated mutations in the transcription factor GATA4 lead to reduced transcription of a key cardiac gene201 that normally facilitates the formation of RMB20 splicing foci, and thus may affect splicing of other RMB20 targets. Clearly, multiple sequencing-based and imaging technologies are required to probe and integrate these dynamic spatial changes to generate mechanistic insights.

Finally, although we do not aim to review the progress in targeting biomolecular condensates for therapy (reviewed in202–204), we will mention a recent report about small molecules designed to perturb condensates for splicing regulation205. Small molecule inhibitors targeting the dimethylarginine binding pocket in the Tudor domain of survival motor neuron domain-containing 1 (SMNDC1) can alter the phase separation behavior and splicing functions of SMNDC1, and the architecture of nuclear speckles205. As a splicing factor essential for spliceosome assembly, SMNDC1 interacts with multiple nuclear speckle proteins and forms nuclear condensates through its IDR. Inhibitors targeting its Tudor domain reduced the mobility of SMNDC1 and SRRM2 in nuclear speckles without affecting the structure of the MLO, but they resulted in global splicing changes. However, because the inhibitors cause a downregulation of SMNDC1 protein, it is hard to attribute the splicing and other biological effects to inhibition of SMNDC1 condensation205. Clearly, a long way remains ahead of successfully modulating splicing through pharmacological regulation of biomolecular condensates.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS