Abstract

Extracellular DNA (eDNA) is crucial for the structural integrity of bacterial biofilms as they undergo transformation from B-DNA to Z-DNA as the biofilm matures. This transition to Z-DNA increases biofilm rigidity and prevents binding by canonical B-DNA-binding proteins, including nucleases. One of the primary defenses against bacterial infections are Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs), wherein neutrophils release their own eDNA to trap and kill bacteria. Here we show that H-NS, a bacterial nucleoid associated protein (NAP) that is also released during biofilm development, is able to incapacitate NETs. Indeed, when exposed to human derived neutrophils, H-NS prevented the formation of NETs and lead to NET eDNA retraction in previously formed NETs. NETs that were exposed to H-NS also lost their ability to kill free-living bacteria which made H-NS an attractive therapeutic candidate for the control of NET-related human diseases. A model of H-NS release from biofilms and NET incapacitation is discussed.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Biofilms

Introduction

Bacterial biofilms are communities of bacteria, often consisting of multiple species or multiple kingdoms of microorganisms living within an extracellular matrix (ECM)1. The investigation of the biofilm ECM is ongoing, but it is known to consist of polysaccharides, lipids, proteins, and extracellular DNA (eDNA)2, depending on the microorganisms in the community. The importance of biofilm eDNA as a universally common component of the ECM became evident when it was shown that depleting biofilm eDNA using DNase I, led to biofilm prevention but not the disruption of mature biofilms3. While this result was originally interpreted as eDNA only being important in early biofilm development, studies from our lab provided an explanation as to why DNase no longer disrupted mature biofilms; during biofilm development there is a transition of eDNA from the canonical form of B-DNA to Z-DNA, where the Z-form is not a substrate for B-DNA binding proteins, including DNase I4.

Further, we showed that a two-member family of bacterial DNA-binding proteins, HU and IHF, known as DNABII proteins, facilitated the transition of eDNA from B- to Z-DNA. DNABII proteins both bend DNA and bind to bent DNA. All known eubacteria express at least one DNABII allele, while DNABII genes are absent from mammalian genomes5. Intracellularly, DNABII proteins act as accessory factors by functioning as nucleoid architectural elements in all manner of DNA transactions including DNA replication, repair, transcription and recombination, as well as facilitating compaction of genomic DNA6. Extracellularly, in biofilms, DNABII proteins have a structural role wherein they act as DNA linchpins, the importance of which can be observed when antibody directed against DNABII proteins (e.g., α-DNABII) sequesters DNABII proteins from biofilms leading to their total collapse regardless of biofilm composition or biofilm age7–9. In vitro explorations of DNABII proteins and their role as Z-DNA forming facilitators showed that Z-DNA is not only induced in biofilm infections within a host, but that DNABII proteins also altered host-derived neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) eDNA from B to Z-DNA4 that is proximal to biofilms, a phenomenon observed in pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis patient samples10 and chinchilla model of otis media4.

NETs are one of the key defense mechanisms of the host immune system against cellular pathogens. Induction of NETs can be triggered by diverse stimuli, which can be receptor mediated e.g., Complement Receptors (CRs), Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs), Fc receptors (FcRs)11 or by chemicals like phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), which induces NET formation via activation of Protein Kinase C (PKC)12. The induction of NETosis leads to the release of neutrophil DNA which is laden with antimicrobials like neutrophil elastase (NE), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and citrullinated histones (H3Cit)13. In this way, these bound molecules are restricted in 3-dimensional space and thereby are positioned to focus their antimicrobial activity on NETs DNA-captured pathogens. NETs utilize these DNA structures and associated antimicrobials to trap and kill free-living bacteria, but also attempt to restrict biofilm growth14,15.

While NETs are critical to the human innate immune system, excessive NETosis can be harmful, even in the absence of a pathogenic trigger, e.g., the extensive microthrombosis observed in COVID-19 infections16,17. Indeed, SARS-CoV 2 infection leads to an overabundance of NETs due to the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within neutrophils stimulated with serum from COVID-19 patiants18. The inflammation caused by NET release in infected neutrophils results in the recruitment of more neutrophils, which in turn releases additional NETs, exacerbating inflammation to the point of thrombosis19. One study investigating excessive NETosis using a murine deep vein thrombosis model showed a specific linkage of PAD4 and NET formation to clotting. Indeed, PAD4 knockout mice did not exhibit deep vein thrombosis, which suggested that inhibiting the NETosis process could help prevent NET-related diseases20. Additionally, several pre-existing conditions, such as autoimmunity, autoinflammation, and metabolic diseases, increase susceptibility to NET-related complications13. While excessive NETosis and the ensuing thrombosis is one example of a disease state that can be caused by NETs, unbound histones which are a component of NET-mediated defense against microbes can also be cytotoxic and thereby cause collateral tissue damage upon their release21. Pathologies also arise, when NET turnover becomes ineffective e.g., in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) anti-NET antibodies prevent serum endonuclease DNAs1 access to NET DNA leading to impaired disassembly of NETs22. To date, no NET-specific therapies have been FDA approved13.

We have already shown that when the eubacterial DNABII protein, HU, is added to neutrophils that have been induced to produce NETs, the B-DNA released is converted to Z-DNA. This conversion renders the NETs ineffective at killing pathogens, likely because the newly formed Z-DNA is unable to bind antimicrobial molecules, which prevents them from targeting the trapped pathogens4. DNABII proteins belong to a class of bacterial proteins known as nucleoid associated proteins (NAPs). NAPs are typically small proteins (less than 20 kD) that serve as architectural elements that organize bacterial chromatin. In addition to shaping DNA architecture, they also act as transcriptional activators or repressors, thus playing a role in DNA compaction23,24. Many of the NAPs, including curved DNA binding protein A (CbpA) and H-NS have no structural role in biofilms but are nonetheless found extracellularly7,25. HU and H-NS often intersect by regulating the same genes26,27. Interestingly, H-NS is referred to as a universal repressor and can compact DNA while HU may have the opposite effect and activates gene expression28–30.

H-NS is a highly abundant, constitutively expressed protein that is predominately found in gram negative bacteria23,31,32. The genes impacted by H-NS are varied and it is estimated that 5% of Escherichia coli genes are affected directly or indirectly by H-NS33. H-NS bridges DNA sequences which create loops that aid in DNA compaction29,34,35. Herein, an exploration of H-NS released from three known biofilm forming pathogens, NTHI, S. pneumoniae, and Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), demonstrated the ability of H-NS to prevent NET-mediated killing by compacting the eDNA of NETs and consequentially, release of the eDNA-bound antimicrobials. The capability of H-NS to disable NET eDNA differs from that of HU wherein the eDNA tentacles of NETs are inactivated due to their structural conversion from B-DNA to Z-DNA. Our findings suggest that as the biofilm eDNA enters the Z-conformation, H-NS is released into the bulk solution. We provide evidence that the ensuing release of H-NS from the bacterial biofilm allowed H-NS to bind the remaining B-form eDNA of NETs. This shift implies that biofilm-resident pathogens may employ a two-pronged defense strategy against NETs: HU and H-NS target the B-form of NET eDNA using distinct mechanisms to neutralize this critical host immune response, thereby preventing pathogen killing and allowing the spread of infection.

Results

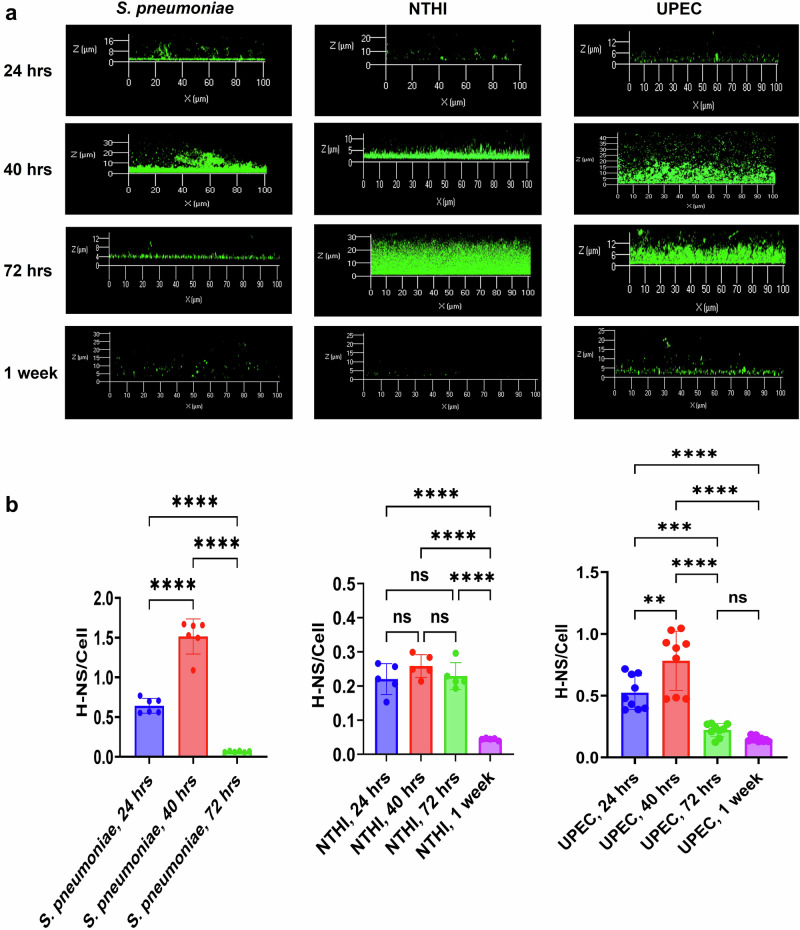

Steady state levels of H-NS partition from mature biofilms to the bulk media over time

H-NS is a B-DNA binding protein that has been found extracellularly in an NTHI biofilm8. When depleted from the biofilm via H-NS specific antiserum there was no observable impact on biofilm structure e.g., no change in the biomass or thickness of the biofilm which suggested that H-NS was not necessary for biofilm structure7. However, to determine if H-NS played a role in biofilm development we used immunofluorescence and found that while there was an initial increase in the steady state levels of H-NS, as the biofilm matured there was a precipitous drop for S. pneumoniae biofilms; steady state levels increased through 40 h of growth but dropped after 72 h and at 1 week was below the limits of quantification (Fig. 1). For NTHI and UPEC biofilms, H-NS levels rose from 24 h to 72 h, then dropped when the biofilms became a week old (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Steady state H-NS protein levels peak but eventually decrease within NTHI, S. pneumoniae, and UPEC biofilms as the biofilm matures.

a Representative confocal image of H-NS (green) in S. pneumoniae, NTHI, and UPEC biofilms of ages varying from 24 h to 1 week. H-NS is represented in green. b The ratio of fluorescence intensity of H-NS to bacterial cells in NTHI, UPEC, and S. pneumoniae within 24, 40, 72 h, and 1 week old biofilms. Mean values of n = 6 for S. pneumoniae, n = 5 for NTHI, and n = 9 for UPEC biological replicates ± SEM are shown in (b). P values (NS > 0.05, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.0001) using ordinary one-way ANOVA.

To confirm that this shift in the presence of H-NS was not the result of reduced expression and or protein turnover, the steady state levels of intracellular H-NS was measured via Western blot. Comparing cell lysate samples from biofilms of 24 h, 40 h, 72 h, or 1 week of age, we found that the intracellular levels of H-NS did not change which indicated no change in the balance between expression and turnover of H-NS protein (Supplementary Fig. 1). We have previously shown that during biofilm development, the eDNA structure is shifted from the canonical B-form into the Z-form as the biofilm matures. This B–Z transition occurs within the same time frame as did the reduction of steady state levels of extracellular H-NS. Since, H-NS is a B-DNA binding protein, we thereby hypothesized that as the biofilm develops and Z-DNA predominates, H-NS is released from the biofilm.

H-NS is released during biofilm development as eDNA transitions from B to Z-form

To determine whether H-NS departure from biofilms was the result of conversion of eDNA from the B form to the Z form, we performed two experiments. First, we treated extant biofilms with DNase (Pulmozyme). DNase has no effect on biofilm structure; we have shown this to be the result of Z-DNA (DNase-resistant) maintaining the structural integrity of biofilms, and not the B form (DNase-sensitive)4. Indeed, DNase only reduces the steady state levels of B-DNA in a mature biofilm. Thus, if DNase treatment of biofilms increased the release of H-NS from the biofilm, this would indicate that H-NS integration into the biofilm matrix is the result of B-DNA binding only. As shown in Fig. 2a, using fluorescence intensity measurements from confocal microscopy, the ratio of H-NS to cell fluorescence intensity decreases, when B-DNA within a 24 h biofilm was cleaved by Pulmozyme. Indeed, H-NS steady state levels concomitantly increased in the conditioned media, while H-NS decreased within the corresponding biofilm matrix upon treatment with Pulmozyme. In contrast, intracellular H-NS levels remained unchanged (Fig. 2b). As expected, steady state levels of extracellular DNABII proteins, remained unchanged upon treatment with DNase since DNABII protein maintenance in the biofilm relies solely on Holliday Junction like structures that are occluded from nonspecific DNases by the DNABII proteins (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2. DNase treatment of biofilms leads to a depletion of H-NS in the biofilm and its release into the surrounding media.

a Addition of DNase (Pulmozyme) to 24 h NTHI biofilm led to a lower ratio of H-NS to cell fluorescence intensity as the Pulmozyme treatment reduced the presence of B-DNA within the biofilm matrix. Mean values of n = 4 biological replicates ± SEM are shown. b Western blots showing H-NS in the conditioned media, biofilm matrix and cells of untreated versus Pulmozyme treated NTHI biofilm. The graphs show the densitometric analysis of the Westerns from 3 independent experiments. Mean values of n = 3 biological replicates ± SEM are shown. c Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of H-NS or HU normalized with intensity of the cells calculated from confocal images of NTHI biofilm treated with or without pulmozyme. Mean values of n = 3 biological replicates ± SEM are shown. P values (NS > 0.05, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005) using an unpaired T test (a, b) RM two-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple t-test (c).

Second, we enhanced the kinetics of Z-DNA formation. Previously, we showed that adding CeCl3 to developing biofilms promoted transition of B form eDNA to Z DNA. We reasoned that this enhanced shift to Z-DNA would increase the release of H-NS from biofilms. As shown in Fig. 3, when Z-DNA became the predominate eDNA form within the NTHI biofilms, H-NS was no longer able to bind to the biofilm eDNA which caused it to dissociate from biofilm (Fig. 2). Taken together, these data showed that it was the shift from B form eDNA to Z-form that resulted in the release of H-NS from the biofilm.

Fig. 3. CeCl3-mediated Z-DNA formation led to the loss of H-NS from the biofilm.

a Fluorescence intensity of H-NS calculated and normalized with the intensity of cells within NTHI biofilms with or without CeCl3 treatment. b Fluorescence intensity (FI) of Z-DNA in NTHI biofilms with or without CeCl3 treatment. Mean values of n = 5 biological replicates ± SEM are shown. p values (***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.0001) are from an unpaired T test.

H-NS prevented neutrophil DNA release and retracted previously released B-DNA from the NETs

We have shown that the DNABII proteins are released from the biofilm matrix in small quantities due to the natural equilibrium between their association with Holliday junction (HJ)-like structures in the biofilm matrix and their presence in the surrounding bulk medium. Despite their limited release, they have a profound ability to convert B-DNA released by NETs to Z-form thereby rendering NETs inactive. This eDNA conversion predominantly begins with eDNA most proximal to the bacterial biofilm, where DNABII proteins are in equilibrium with the eDNA in the biofilm matrix. Since H-NS release is based on the diminution of it’s substrate (B-DNA), we expect that a greater quantity of H-NS is released than DNABII proteins. In this regard, we wondered whether H-NS might also influence any NET B-eDNA that had, as of yet, not been converted to Z-DNA and if so, how this might affect NET-mediated functions.

In vivo, NET eDNA is released by neutrophils when stimulated by pathogens, but NETosis can also be stimulated in vitro using PMA. During NETosis, chromatin decondenses due to histone citrullination, which reduces the net positive charge of the histones, and thus their ability to maintain their nucleosome structure, allowing neutrophil DNA release. Citrullinated histones remained attached to the released DNA, albeit loosely. This release of neutrophil DNA in the form of NETs, along with bound antimicrobials, can be visualized using immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy.

We therefore examined the effect of added H-NS on NETosis. CbpA, a DnaJ homolog36, that preferentially binds to curved DNA was utilized as a negative control. Though, both H-NS and CbpA bind to curved DNA and are known to condense DNA37,38; only H-NS was able to prevent the deployment of neutrophil eDNA while CbpA showed no such effect (Fig. 4a). When neutrophils were stimulated to form NETs using PMA, H-NS was able to collapse the preformed NET DNA structures (Fig. 4b). Although CbpA shows some restructuring of the DNA deployed by NETs, it was not able to collapse the DNA structures formed in NETosis. Importantly, fluorescence staining revealed that the antimicrobials such as neutrophil elastase (NE), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and citrullinated histone H3 (H3Cit) remained bound to retracted NET eDNA and were not displaced by H-NS (Supplementary Fig. 2). We also observed that the newly introduced CbpA and H-NS remained bound to the NET released eDNA showing that both proteins are active for DNA binding (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, only H-NS treatment significantly reduced PMA induced NET formation while CbpA had a negligible effect (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. H-NS both prevents PMA-induced NET formation and induces retraction of NET-deployed eDNA.

a Representative CLSM images of the NETs induced using PMA with or without H-NS/CbpA are shown where DNA is in blue, plasma membrane in green, and neutrophil elastase in red. b NETs induced with PMA were treated with H-NS/CbpA, representative CLSM images are shown where DNA is in blue, plasma membrane is in green, and neutrophil elastase is in red for each condition based on 3 independent experiments.

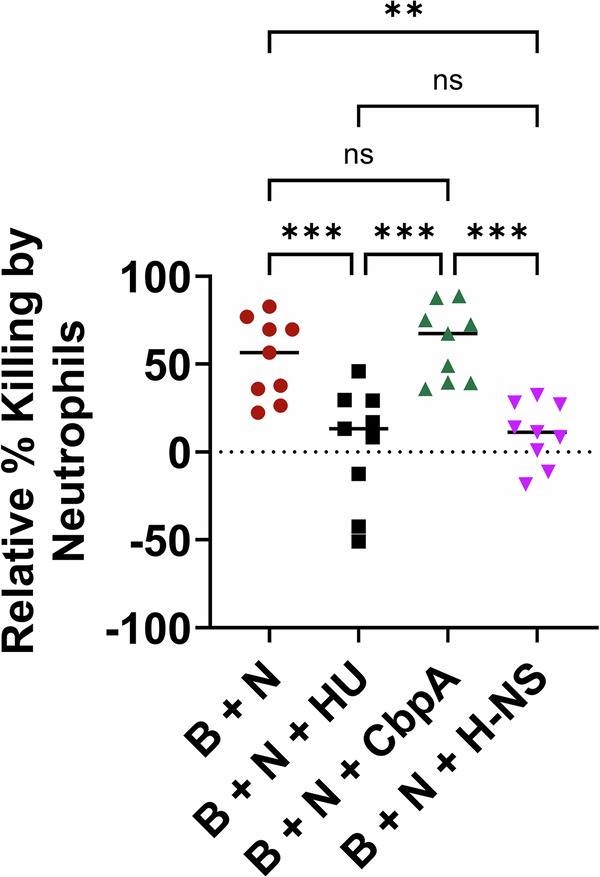

H-NS prevented NET-mediated killing of bacteria

Whereas PMNs have limited ability to infiltrate and kill bacteria within biofilms, NETs formed by PMNs exterior to the biofilm are capable of both killing free-living bacteria and can cordon off the biofilm, thereby restricting its growth. With NETs relying on their released B-form eDNA tentacles to kill bacteria, and H-NS inducing condensation of these tentacles, it was likely that H-NS would prevent NET-mediated killing of bacteria in addition to induction of a change in NET morphology. HU is known to convert NET B-form eDNA to Z-DNA and prevent NET-mediated killing and as such4, we used HU as a positive control for comparison with H-NS to determine the degree to which each could prevent NET-mediated killing of bacteria. H-NS significantly reduced the amount of bacterial killing by NETs as did HU (Fig. 5). CbpA was unable to prevent bacteria killing by NETs which correlated with the inability of CbpA to disrupt NET morphology and or prevent NETosis. The ability of H-NS to prevent NET-mediated killing of bacteria confirmed our hypothesis that by condensing the eDNA of NETs, H-NS release acted as a defense on behalf of the biofilm-resident bacteria against an important effector of the host’s innate immune system.

Fig. 5. H-NS prevented NETs mediated killing of NTHI.

NTHI biofilms were incubated with isolated human neutrophils (B + N), or neutrophils plus exogenous HU (B + N + HU)/CbpA (B + N + CbpA)/H-NS (B + N + H-NS) and the percentage of bacteria killed relative to the CFUs present in NTHI biofilm without neutrophils added was calculated. Mean values of n = 9 biological replicates ± SEM are shown. P values (***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001) were calculated using ordinary two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple t-test.

Discussion

Neutrophils are the most common immune cell, circulating throughout the body to carry out one of three functions: phagocytosis, degranulation, or release of DNA to form NETs39. In NETosis, neutrophils expel fibers of decondensed DNA to combat bacterial, fungal, and some viral infections39. NETs are also formed during inflammatory events such as spontaneous human appendicitis15. However, excessive NETosis, or even the inability to clear NETs after a NETosis event, can cause collateral damage in the host including tissue damage and thrombosis. While any excessive inflammation or other negative side effects of disproportionate NETosis can be treated with anti-inflammatory drugs or reactive oxygen species inhibitors, no drug that specifically targets NETs without impacting other host cells has been approved by the FDA. For this reason, it was of interest to us to attempt to identify biologicals that could specifically inactivate NETs, such as H-NS, for potential use as a novel therapeutic capable of either preventing the release of NET eDNA and/or inactivating NETosis by causing retraction of NET eDNA4 when needed in specific disease states.

While we favor NET eDNA aggregation as the means by which H-NS so strongly inhibits and condenses NETs, there are multiple attributes through which H-NS could mediate its functions. Indeed intracellular H-NS has a critical role in gene repression via its ability to self-associate and hetero-oligomerize, bind DNA40, stabilize supercoiled DNA, and constrain negative supercoils32,41. Outside a bacterial cell, and within the bacterial biofilm, deprivation of H-NS has no impact on biofilm size or structure (i.e., thickness, biomass as determined by COMSTAT)7. Instead, H-NS appears to be released as the eDNA within the biofilm transitions from the canonical B-form to the distinctive Z-form, rendering the DNA inaccessible for H-NS binding4,7,42. Indeed, adding CeCl3 to NTHI biofilms facilitates both Z-DNA formation and H-NS release. While we cannot rule out specific effects of Ce3+ on H-NS-eDNA interactions, our data is consistent with H-NS release from the Z-eDNA dependent biofilm matrix into the surrounding milieu as the biofilm matures and is thereby able to hone in on the only other local source of B-form eDNA, NETs. Moreover, H-NS when bound to DNA is known to be protected from proteolysis43 which may influence its equilibrium towards the DNA bound state and enhance its stability in situ to protect H-NS from PMN released proteases. We have previously shown that release of the eubacterial DNABII protein, HU, converts NET-deployed B-DNA to Z-DNA with the exception of B-DNA in closest proximity to the neutrophil itself4. While the exact sequence of events that occurs in NET inactivation (e.g., HU conversion of NET eDNA from B-form to Z-form and H-NS retraction of NET eDNA) has yet to be determined, it is clear that both B- and Z-form NET eDNA is detected distal to the biofilm, and that both of the stated mechanisms will inactivate NET-mediated killing. While we have proposed that DNABII proteins, such as HU, play a defensive role to stabilize the eDNA-dependent extracellular matrix of biofilms, these proteins also act offensively against NET functionality by altering NET eDNA structure. In contrast, H-NS does not appear to affect the eDNA-dependent ECM of biofilms, however similar to the DNABII proteins, this NAP acts offensively to both prevent the deployment of NET eDNA at the time of activation, as well as condenses NET eDNA that has been deployed after activation. The combined effect of both DNABII proteins and H-NS prevent NET-mediated killing of bacteria.

H-NS’s ability to both prevent the full release of eDNA tentacles that form a NET at the time of PMA-induced NETosis and condense previously released NET eDNA hours after induction along with its presence on the NET DNA indicate that H-NS is interacting with the eDNA of the NET itself, and not the pathway of NET release. This conclusion is supported by the presence of NE and CitH3 observed bound to released NETs post H-NS treatment as observed via immunofluorescence microscopy. Herein, we also showed that NE co-localized with released NET eDNA, which indicated that NE remained bound to the now condensed NET eDNA. Thus, we hypothesize that it is H-NS’s ability to oligomerize and condense DNA32 that is solely required for NET retraction. Additional work will be required to show whether other DNA-aggregating agents are capable of similar NET retracting functions.

Common pathogenic bacteria including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, and several of the ESKAPEE pathogens (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumanii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.) have genes that encode H-NS (or its paralogues) within their genomes, which suggests that numerous pathogens beyond those studied in this work can utilize H-NS as a defense against host neutrophils. Interestingly, within the Gram-positive genera Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, only S. aureus and S. pneumoniae express H-NS homologs. The rarity of H-NS within these genera raises questions about shared characteristics among H-NS-expressing organisms. One possible explanation for the expression of H-NS in a limited number of organisms is horizontal gene transfer amongst organisms capable of induction of infection within a specific anatomic niche, such as the nasopharynx, skin, or lungs. The possibility of horizontal gene transfer is supported by the high (greater than 90% determined via BLAST) sequence similarity between the genes that encode H-NS in NTHI and S. pneumoniae, two pathogens often found in co-infections.

The prevention of NET release and NET-mediated bacterial killing by H-NS makes it a plausible offensive protein on behalf of biofilm-resident bacteria that could work in conjunction with HU. By utilizing both HU and H-NS to deactivate NETs, biofilm-resident bacteria would be able to disperse and proliferate within the host if and when this was needed. HU and H-NS could potentially work in tandem to achieve the loss of NET-killing activity i.e., HU would convert B-DNA to Z-DNA within NETs that have already been activated, whereas H-NS would function to both prevent NETs from being deployed by PMNs in the early phases of NETosis as well as condense already deployed NETs more distal to the biofilm. Our model relies on H-NS release failing to be in equilibrium with the bulk biofilm eDNA since the conversion of B to Z DNA is stable. In contrast, DNABII proteins are in equilibrium with the Holliday Junction-like structures within the biofilm. This suggests that the relative levels of biofilm released H-NS is in higher proportions than DNABII proteins7,9. The dual ability to prevent NET formation and retract already deployed NET eDNA makes H-NS a protein worthy of further investigation as a therapeutic candidate against excessive NETosis. The mechanisms through which H-NS binds DNA are well known and should provide a strong starting place for isolating promising H-NS-derived peptides that could be used as a human therapeutic. Such peptides could hold the potential to combat NET dependent thrombosis and tissue damage that results from diseases such as Covid-19 or pre-existing conditions e.g., patients with SLE where NET clearance is inhibited22,32,44,45. By targeting NET-related pathology, H-NS or H-NS-derived peptides may offer a novel approach for treating conditions characterized by pathological excessive NETosis.

Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

NTHI strain 86-028NP is a clinical isolate recovered from the nasopharynx of a child undergoing tympanostomy tube insertion that was streaked out on chocolate agar and grown overnight in a 37 °C incubator at 5% CO246. Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) UTI189 was streaked out and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO242. Streptococcus pneumoniae 1121 (SG1241) (gift from Dr. Samantha King) was streaked onto blood agar and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Expression and purification of NAPs

The expression and purifications of NTHI H-NS, NTHI CbpA, and NTHI HU have been described previously7. Briefly, hns, cbpA, and hupA from NTHI were all cloned into pTXB1 vector in-frame to maintain the protein sequences and then transformed into the ER2566 E. coli expression strain. Each strain was grown in LB medium with 100 μg/mL ampicillin and then protein overexpression was induced using 100 mM IPTG. Purification of each protein was carried out on a chitin resin column, followed by cleavage to remove the tag, with a binding buffer containing 100 mM DTT for 72 h. The proteins were then further purified using FPLC (GE ӒKTA Pure™) on a HiTrap Heparin HP column (GE Healthcare).

Quantification of H-NS using immunofluorescence

Polyclonal anti-H-NS IgG purified from rabbit serum had been produced previously7 against recombinant NTHI H-NS was used for labeling H-NS in NTHI, S. pneumoniae, and UPEC biofilms of varying ages. All biofilms were initiated in 8-well glass bottom chamber slides and the fresh media was changed 8 and 16 h later to feed the biofilms, except for week-old biofilms where after 5 days the media was replaced every 12 h. NTHI colonies were resuspended in brain-heart infusion broth supplemented with 2 μg/mL β-NAD (NAD+) and 2 μg/mL heme (sBHI) (BD Diagnostic Systems), UPEC was resuspended in LB, and S. pneumoniae in Todd-Hewitt Broth (THB) (BD Diagnostic Systems) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract, all resuspensions were added to the chamber slides at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/mL. Biofilms were grown for 24 h, 40 h, 72 h, and one week. When the biofilms reached the desired age, they were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and rabbit anti-H-NS [diluted 1:200 in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA)] was added for 2 h. After incubating at room temperature for 2 h, the wells were washed with PBS one time and then goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 and the bacterial membrane stain FM 4–64 were added (both diluted 1:200 in 5% BSA in PBS). The biofilms were then incubated at room temperature in the dark for 1 h, washed with PBS an additional time and visualized on a Zeiss 800 Light Scanning Microscope (LSM). The mean fluorescence intensity for both H-NS and the bacterial cells was determined using ImageJ software.

In the case of CeCl3 and Pulmozyme® additions, 500 μM CeCl3 dissolved in distilled water and Pulmozyme® (Genentech, dornase alfa, NDC Code 50242-100-40) [150 µg/mL] in sBHI media were added to biofilms at 24 h of age, then allowed to incubate with the biofilm overnight (16 h) for CeCl3 or for 90 min with Pulmozyme®. Biofilms were then prepared for confocal LSM following the protocol described above.

Western blotting

Western blots were carried out to determine the levels of H-NS in the conditioned media, biofilm, and lysate (intracellular contents) of 24 h, 40 h, and 72 h NTHI biofilms. Biofilms were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/mL in 25 cm3 cell culture-treated flasks and allowed to grow in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Media was changed every 24 h where all but 1 to 2 mL of conditioned media was removed from the cell culture flask, the conditioned media was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, then the same volume of conditioned media that was removed was replaced by fresh, pre-warmed media. To collect the fraction of H-NS found bound extracellularly to the eDNA within the biofilm, the biofilms were incubated with 0.9% NaCl for 10 min, biofilms were removed by scraping with sterile cell scraper followed by vigorous pipetting then sonicated (Fischer scientific, FS20) for 5 min. The resuspension was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then filtered, first through a 0.45-µm pore size filter (Millex-HA Non-Sterile Syringe Filter), then through a 0.22-µm pore size filter (KX Sterile Syringe Filter, Kinesis) to eliminate residual bacterial cells from the supernatant and labeled as biofilm fraction of H-NS. The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4), along with 0.5 mg lysozyme, and DNase I. Once resuspended, the cell suspension was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, then sonicated in a water bath for 10 s increments every minute for 5 min.

Lysate and media samples were separated using SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed for H-NS using polyclonal rabbit anti H-NS IgG. The membrane was then probed with anti-rabbit IgG-HRP and detected with Western Blot Super Signal Reagent and visualized on a BIoRad MP Imager. In the case of biofilms at 24 h of age that were treated with Pulmozyme®, the same protocol that was used for confocal microscopy was used for Western Blot sample preparation.

Visualization of NETs

PMNs were isolated from freshly collected blood from healthy donors using EasySep™ Human Neutrophil Isolation Kit from StemCell Technologies (Cambridge, MA). The isolated neutrophils were quantified using hemocytometer, and 200,000 cells were added to each well of an 8 well chamber slide. The neutrophils were then allowed to adhere to the bottom of the well for 30 min while incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After incubation, 100 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was added to neutrophils to induce NETosis. To determine whether H-NS was able to prevent NETosis, 200 nM NTHI H-NS was added at the same time as PMA. Similarly, to determine whether H-NS could condense previously released NET eDNA, H-NS was added 16 h after NETois was induced. After PMA addition, neutrophils were incubated for 3.5 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Neutrophils were then fixed with 0.4% formalin and 0.1% Triton X-100 was added for cell permeabilization. PMNs were then blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 30 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2 after which primary antibody was added and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies utilized α-dsDNA mouse monoclonal antibody (1 μg; Abcam, ab27156), α-neutrophil elastase rabbit monoclonal antibody (1 μg; Abcam ab131260), anti-Histone H3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (citrulline R2 + R8 + R17) antibody (1 μg; Abcam, ab5103), anti-Myeloperoxidase recombinant rabbit monoclonal antibody (1 μg; Abcam, ab5103), naive rabbit and mouse isotype controls (1 μg; Abcam, ab37415 and ab18415), rabbit polyclonal α-H-NS, rabbit polyclonal α-CbpA and rabbit polyclonal ISO control, were diluted 1:200 in PBS and incubated for 16 h at 4 °C. NETs were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h with 1:200 dilution goat α-rabbit IgG conjugated to AlexaFluor® 405 (Invitrogen, A11032), goat α-mouse IgG conjugated to AlexaFluor® 594 (Invitrogen, A11001), and 1:500 dilution wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to AlexaFluor® 488 (PMN membrane stain, Fisher scientific, W6748). NETs were imaged with a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc.) and rendered with Zeiss Zen software. Using ImageJ, Z-stack projection of the images was generated by summing all the stacks, followed by brightness and contrast adjustments using the auto setting for all fluorophores to improve the image quality of the representative images presented in the manuscript. MFI values for NE/MPO/H3Cit, dsDNA, and Plasma Membrane (PM) using ImageJ. Cells were counted manually using ImageJ and NET forming cells % of the total cells present per well was plotted using GraphPad Prism.

Quantification of NET killing

Inactivation of bacterial killing by NETs is measured as described previously4. Briefly a 16 h NTHI biofilm was established 8-well chambered cover-glass slide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) as described above. Human neutrophils isolated from freshly collected blood from healthy donors as described above. After the 16 h NTHI biofilm were washed carefully with PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria, followed by the addition of 300 ml of RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. 2 × 105 neutrophils were added with or without following proteins: 1 μM H-NS, 1 μM HU, or 1 μM CbpA, no proteins or neutrophils added biofilm was used as a control and incubated for 3–4 h at 37 °C. Post incubation, 0.1% Triton X-100 was added for 5 min to the cultures to release any intracellular bacteria from the PMNs. All bacteria recovered by homogenization via pipetting, were plated on chocolate agar post serial dilutions in PBS. Colony forming units (CFUs) were counted after 16 h incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The percentage of reduction of the number of NTHI (total CFU) and % relative killing was calculated as indicated in the following formulas: [(CFU of each sample) ÷ (average CFU of NTHI only controls) 100 = % viable]: [% Killing = 100% − (% viable)]. The relative % killing was normalized so that the NTHI only control represented 0% killing as follows: [100% (e.g., an average of NTHI control) − (% killing of each sample) = relative % killing].

Statistical analysis

Graphical results were analyzed, and statistical tests were performed with GraphPad Prism 10 for all in vitro assays. Data from two groups were analyzed by unpaired t-tests, whereas data from multiple groups were analyzed by one-way/ two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and significance is shown as *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001, and ****P < 0·0001. n represents the number of biological replicates and is defined within respective figure legends.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NIDCD R01DC011818 to L.O.B. and S.D.G. and NIH/NIAID R01AI155501 to SDG and LOB.

Author contributions

A.L.H. and S.D.G. designed the experiments. A.L.H. and K.R.M. performed experiments and wrote and modified the initial manuscript draft. A.D., J.R.B. and F.R.A. performed preliminary experiments. L.O.B., S.D.G., and S.P.S. supervised the project. L.O.B. and S.D.G. conceptualized the study, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All relevant data is contained within the manuscript and supplementary files, additional data if any are available from the authors on appropriate request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

7/2/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41522-025-00761-3

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41522-025-00691-0.

References

- 1.Penesyan, A., Paulsen, I. T., Kjelleberg, S. & Gillings, M. R. Three faces of biofilms: a microbial lifestyle, a nascent multicellular organism, and an incubator for diversity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes7, 80 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flemming, H. C., Neu, T. R. & Wozniak, D. J. The EPS matrix: the “house of biofilm cells. J. Bacteriol.189, 7945–7947 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitchurch, C. B., Tolker-Nielsen, T., Ragas, P. C. & Mattick, J. S. Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science295, 1487 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buzzo, J. R., et al. Z-form extracellular DNA is a structural component of the bacterial biofilm matrix. Cell184, 5740–5758. e5717 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swinger, K. K. & Rice, P. A. IHF and HU: flexible architects of bent DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.14, 28–35 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boubrik, F., Bonnefoy, E. & Rouviere-Yaniv, J. HU and IHF: similarities and differences. In Escherichia coli, the lack of HU is not compensated for by IHF. Res. Microbiol142, 239–247 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devaraj, A., Buzzo, J., Rocco, C. J., Bakaletz, L. O. & Goodman, S. D. The DNABII family of proteins is comprised of the only nucleoid associated proteins required for nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae biofilm structure. Microbiologyopen7, e00563 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devaraj, A. et al. The extracellular DNA lattice of bacterial biofilms is structurally related to Holliday junction recombination intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA116, 25068–25077 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman, S. D. et al. Biofilms can be dispersed by focusing the immune system on a common family of bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins. Mucosal Immunol.4, 625–637 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofer, L. K., Jurcisek, J. A., Elmaraghy, C., Goodman, S. D. & Bakaletz, L. O. Z-form extracellular DNA in pediatric CRS may provide a mechanism for recalcitrance to treatment. Laryngoscope134, 1564–1571 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, T. et al. Receptor-mediated NETosis on neutrophils. Front. Immunol.12, 775267 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray, R. D. et al. Activation of conventional protein kinase C (PKC) is critical in the generation of human neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Inflamm.10, 12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutua, V. & Gershwin, L. J. A Review of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Disease: Potential Anti-NETs Therapeutics. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol.61, 194–211 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thanabalasuriar, A., et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Confine Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ocular Biofilms and Restrict Brain Invasion. Cell Host Microbe25, 526–536. e524 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinkmann, V. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science303, 1532–1535 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Middleton, E. A. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to immunothrombosis in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Blood136, 1169–1179 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinod, K. & Wagner, D. D. Thrombosis: tangled up in NETs. Blood123, 2768–2776 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arcanjo, A. et al. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (COVID-19). Sci. Rep.10, 19630 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu, Y., Chen, X. & Liu, X. NETosis and neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19: immunothrombosis and beyond. Front Immunol.13, 838011 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinod, K. et al. Neutrophil histone modification by peptidylarginine deiminase 4 is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA110, 8674–8679 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu, J. et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat. Med15, 1318–1321 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakkim, A. et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA107, 9813–9818 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holowka, J. & Zakrzewska-Czerwinska, J. Nucleoid Associated Proteins: the small organizers that help to cope with stress. Front. Microbiol.11, 590 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dillon, S. C. & Dorman, C. J. Bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins, nucleoid structure and gene expression. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.8, 185–195 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chintakayala, K. et al. DNA recognition by Escherichia coli CbpA protein requires a conserved arginine-minor-groove interaction. Nucleic Acids Res.43, 2282–2292 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schechter, L. M., Jain, S., Akbar, S. & Lee, C. A. The small nucleoid-binding proteins H-NS, HU, and Fis affect hilA expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun.71, 5432–5435 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martínez-Santos Verónica, I., Medrano-López, A., Saldaña, Z., Girón Jorge, A. & Puente José, L. Transcriptional regulation of the ecp operon by EcpR, IHF, and H-NS in attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol.194, 5020–5033 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dame, R. T. & Goosen, N. HU: promoting or counteracting DNA compaction?. FEBS Lett.529, 151–156 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dame, R. T. et al. DNA bridging: a property shared among H-NS-like proteins. J. Bacteriol.187, 1845–1848 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernández-Martínez, G. et al. The nucleoid protein HU positively regulates the expression of type VI secretion systems in Enterobacter cloacae. mSphere9, e0006024 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucchini, S. et al. H-NS mediates the silencing of laterally acquired genes in bacteria. PLoS Pathog.2, e81 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tupper, A. E. et al. The chromatin-associated protein H-NS alters DNA topology in vitro. EMBO J.13, 258–268 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hommais, F. et al. Large-scale monitoring of pleiotropic regulation of gene expression by the prokaryotic nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS. Mol. Microbiol.40, 20–36 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noom, M. C., Navarre, W. W., Oshima, T., Wuite, G. J. & Dame, R. T. H-NS promotes looped domain formation in the bacterial chromosome. Curr. Biol.17, R913–R914 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dame, R. T., Noom, M. C. & Wuite, G. J. L. Bacterial chromatin organization by H-NS protein unravelled using dual DNA manipulation. Nature444, 387–390 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bird, J. G., Sharma, S., Roshwalb, S. C., Hoskins, J. R. & Wickner, S. Functional analysis of CbpA, a DnaJ homolog and nucleoid-associated DNA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem.281, 34349–34356 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada, H., Muramatsu, S. & Mizuno, T. An Escherichia coli protein that preferentially binds to sharply curved DNA. J. Biochem.108, 420–425 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinton, J. C. et al. Expression and mutational analysis of the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol.6, 2327–2337 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papayannopoulos, V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol.18, 134–147 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kotlajich, M. V. et al. Bridged filaments of histone-like nucleoid structuring protein pause RNA polymerase and aid termination in bacteria. Elife4, 10.7554/eLife.04970 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Spassky, A., Rimsky, S., Garreau, H. & Buc, H. H1a, an E. coli DNA-binding protein which accumulates in stationary phase, strongly compacts DNA in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res.12, 5321–5340 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devaraj, A., Justice, S. S., Bakaletz, L. O. & Goodman, S. D. DNABII proteins play a central role in UPEC biofilm structure. Mol. Microbiol96, 1119–1135 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi, J. & Groisman, E. A. Salmonella expresses foreign genes during infection by degrading their silencer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA117, 8074–8082 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ackermann, M. et al. Patients with COVID-19: in the dark-NETs of neutrophils. Cell Death Differ.28, 3125–3139 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grainger, D. C. Structure and function of bacterial H-NS protein. Biochem Soc. Trans.44, 1561–1569 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrison, A. et al. Genomic sequence of an otitis media isolate of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: comparative study with H. influenzae serotype d, strain KW20. J. Bacteriol.187, 4627–4636 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data is contained within the manuscript and supplementary files, additional data if any are available from the authors on appropriate request.