Abstract

Ferroptosis plays a significant role in the pathological mechanism of acute kidney injury (AKI) for many etiologies. The characteristics of ferroptosis involve many aspects, including iron metabolism, lipid metabolism, and glutathione metabolism. In terms of iron metabolism, ferroptosis involves the accumulation of labile iron; in terms of lipid metabolism, ferroptosis involves the peroxidation of lipids, especially certain phospholipids; in terms of glutathione metabolism, ferroptosis involves the reduction of reduced glutathione (GSH) levels, leading to a decrease in the activity of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). A lot of traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) have been reported to have a protective effect against AKI, and many of these TCMs have shown a close association with regulating ferroptosis in ameliorating AKI. While the mechanisms through which these TCMs regulate ferroptosis associated with AKI are intricate, many of their targets are linked to the inhibition of lipid peroxidation or the regulation of iron metabolism. This article discusses some aspects of AKI and ferroptosis, and reviews some research progress on the regulation of AKI-related ferroptosis by TCMs.

Keywords: Ferroptosis, Acute kidney injury, Traditional Chinese medicine, Iron metabolism, Lipid peroxidation

Introduction

AKI is a common acute and severe disease in clinical practice, which can be caused by various etiologies. It often manifests as a rapid decline in renal function, an abrupt decrease in urine output, a swift increase in blood creatinine, accompanied by internal environment disorders, and the possibility of multiple systemic complications. If AKI fails to be diagnosed and treated in a timely manner, the lives of patients will be severely threatened, and the recovery of renal function in the surviving patients will also be impacted. However, due to the complex pathogenesis of AKI, developing specific drugs to treat AKI remains a challenge currently. The death of renal cells is very important for the mechanism of AKI. There are many ways for cells to die, including but not limited to necrosis, apoptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, etc. In the past, there were many researches on apoptosis and necrosis in the study of AKI. However, in recent years, it has been found that ferroptosis is becoming increasingly important in the pathological process of AKI [1, 2]. The detailed description of ferroptosis was initially provided by Scott J· Dixon et al. [3]. And later, ferroptosis was extensively studied in tumor-related diseases. While the mechanism of ferroptosis has not been completely elucidated, it primarily involves an intracellular accumulation of labile iron leading to elevated levels of lipid peroxides, resulting in cellular oxidative injury and death. There are currently no specific therapeutic drugs for AKI. However, there is a wealth of clinical experience accumulated in China in using TCMs to treat AKI [4–6]. For example, the Shenshuaikang enema, composed of Astragalus, Rheum, Carthamus tinctorius and Salvia miltiorrhiza, has been utilized in clinical AKI treatment for several decades with favorable efficacy and few adverse reactions [7], and its partial mechanism involves the inhibition of human renal tubular epithelial cell (HK-2) apoptosis by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress [8]. The modulation of ferroptosis by TCMs has emerged as a burgeoning field of research in recent years. For tumor-related diseases, inducing ferroptosis in tumor cells holds potential for anti-tumor therapy, but for AKI, inhibiting ferroptosis in renal cells shows promise in ameliorating AKI and rescuing impaired renal function. In recent years, many studies have been published on the regulation of AKI-related ferroptosis by active ingredients found in TCMs.

The main characteristics of ferroptosis

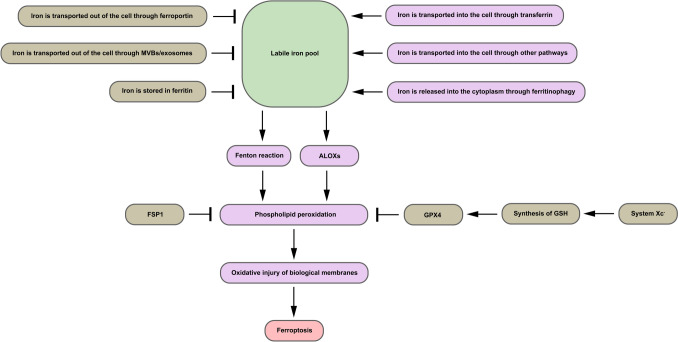

Ferroptosis occurs in AKI caused by various factors, including ischemia-reperfusion-induced AKI [9], AKI caused by some nephrotoxic drugs [10, 11], AKI caused by sepsis [12], etc. The characteristics of ferroptosis are mainly manifested in iron metabolism, lipid metabolism, and glutathione metabolism [13]. The brief process of ferroptosis and the main mechanisms by which cells resist ferroptosis are illustrated in Fig. 1 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The brief process of ferroptosis and the main mechanisms by which cells resist ferroptosis

Iron metabolism

In terms of iron metabolism within cells, HK-2 cells under conditions of ferroptosis typically exhibit higher iron levels within the cells compared to normal HK-2 cells [14, 15]. Generally, iron serves as an important cofactor for diverse enzymes within the cells to uphold normal cellular function, thus emphasizing the essentiality of a moderate iron level for cellular physiological requirements. However, an excessive intracellular labile iron pool resulting from certain pathological conditions can lead to ferroptosis via lipid peroxidation mediated by the Fenton reaction [16].Additionally, some scholars believe that iron can also promote lipid peroxidation by increasing the activity of arachidonate lipoxygenases (ALOXs, a group of iron-containing enzymes) [17]. The changes in cellular iron content involve the participation of various proteins related to iron metabolism, such as transferrin (Tf) and its receptor (TfR), as well as metal cation symporters (such as ZIP8) capable of transporting non-transferrin-bound iron, ferritin, ferroportin (FPN), and the iron-regulatory protein–iron-responsive element network [18]. In addition to iron metabolism-related proteins, multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and exosomes may also exert an influence on iron metabolism. Some researchers have observed that prominin2 can facilitate the formation of MVBs/exosomes to promote the transport of ferritin and iron to the extracellular space and thus resist ferroptosis [19]. Therefore, targeting various aspects in iron metabolism to reduce iron content within cells for the inhibition of AKI-related ferroptosis may be a promising research direction.

Transferrin and transferrin transport in iron metabolism

Tf is ubiquitously present in extracellular fluids, such as interstitial fluid and plasma, and plays a crucial role in the transportation of iron from the extracellular space into the intracellular space. One molecule of Tf can bind two ferric iron (Fe(III)), and Tf in serum can exist in three different forms: the non-iron bound form (apo-Tf), the monoferric form, or the diferric form (holo-Tf) [20]. In a neutral environment on the cell surface, holo-Tf containing two Fe(III) can bind to the TfR on the cell surface, forming the holo-Tf-TfR complex; this complex is then internalized into the endosome of the cytoplasm through endocytosis; within the acidic environment of the endosome, Fe(III) dissociates from the holo-Tf-TfR complex, leading to the formation of an apo-Tf-TfR complex which is subsequently circulated back to the cell surface and disassociated into apo-Tf and TfR (due to reduced affinity between apo Tf and TfR in a neutral environment on the cell surface), followed by apo-Tf continuing to transport other Fe(III) to initiate a new cycle [21, 22]. The dissociated Fe(III) is subsequently reduced to ferrous iron (Fe(II)) by endosomal ferrireductases, such as six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3 [23]. Then, these Fe(II) are transferred from the endosome to the cytoplasm by endosomal iron transporters, such as natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 2 / divalent metal transporter 1 [24]. A study has demonstrated that Tf acts as an extracellular inducer of ferroptosis, and the transport of transferrin is crucial for ferroptosis induced by amino acid deprivation [25]. Therefore, Tf may play a pivotal role as a therapeutic target in the regulation of AKI-associated ferroptosis by TCMs.

Ferritin and ferritinophagy in iron metabolism

Ferritin is widely present in various tissues and organs throughout the human body, serving as an important protein for intracellular storage of non-heme iron, with its composition including ferritin heavy chain (FTH) and ferritin light chain (FTL) subunits. There is a ferro-oxidase site within FTH [26]. The ferro-oxidase site facilitates the oxidation of Fe(II) to Fe(III) by molecular oxygen, after which the Fe(III) mineral core is formed for iron storage [27]. This helps to suppress the Fenton reaction within cells to avoid cellular oxidative injury caused by iron, as the iron that promotes the Fenton reaction is primarily in the form of free Fe(II). Ferritinophagy plays a crucial role in regulating intracellular iron levels and maintaining iron homeostasis within cells. Normally, when cells are in a state of iron deficiency, ferritin is transported to the lysosome via a pathway involving autophagy and undergoes degradation in the lysosome’s acidic environment, leading to the release of bound iron into the cytoplasm for the cell to use [28]. The process of ferritinophagy is dependent on the mediation of nuclear receptor activator 4 (NCOA4) [29]. A research has demonstrated that NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy plays a pivotal role in ferroptosis by influencing cellular iron homeostasis, and inhibiting ferritinophagy can reduce the accumulation of cellular labile iron associated with ferroptosis and prevent ferroptosis [30]. Hence, targeting ferritinophagy also holds significant research potential in the regulation of AKI-associated ferroptosis by TCMs.

Ferroportin in iron metabolism

FPN is a crucial protein responsible for transporting iron from inside the cell to the extracellular space. A research has suggested an association between a nonconservative missense mutation in the FPN gene and the iron accumulation phenotype of autosomal-dominant hemochromatosis [31]. FPN exerts an anti-ferroptosis effect in the hippocampus of APPswe/PS1dE9 mice (used to simulate Alzheimer’s disease) [32] and in the nucleus pulposus cells of intervertebral discs treated with tert-butyl hydroperoxide (used to simulate oxidative stress) [33]. FPN is modulated by hepcidin; upon binding to FPN, hepcidin induces internalization and degradation of FPN, consequently leading to diminished intracellular iron efflux [34]. In the kidney, FPN is highly expressed in the cortical region of the proximal convoluted tubules, and the renal hepcidin/FPN axis is instrumental in kidney iron homeostasis under conditions of iron overload [35]. Some researchers hold the opinion that FPN may have a detrimental impact on the pathophysiology of ischemic AKI; they conducted a research showing that knocking out FPN in the proximal tubules of mice could alleviate ischemic AKI, possibly through the upregulation of FTH1 to restrict catalytic iron and the activation of antioxidant mechanisms [36]. However, another research showed that under folic acid induced AKI conditions, the kidneys of mice with proximal tubular FPN mutations displayed more injury and ferroptosis evidence, as the FPN mutations led to iron overload in proximal tubules by disturbing iron export [37]. In terms of the impact of FPN on AKI, the conclusions drawn from the previous two researches seem to be exactly opposite. Thus, it prompts an intriguing question: Would the role of FPN in AKI induced by different methods be different? If not, there might still be some controversy regarding the role of FPN in AKI-associated ferroptosis, which requires further experiments to answer.

Lipid metabolism

Lipid peroxidation represents a key characteristic of ferroptosis and the polyunsaturated fatty acids on certain phospholipids play a crucial role in lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis [38]. GPX4/phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase [39], formerly referred to as the “peroxidation-inhibiting protein”, plays a pivotal role in the reduction of phospholipid hydroperoxides [40, 41]. In the context of AKI-associated ferroptosis, the expression of GPX4 is typically impaired in HK-2 cells and renal tissues [14, 15], thereby impeding the timely and effective reduction of phospholipid hydroperoxides. Given that phospholipids are integral constituents of biological membranes such as cell membranes and mitochondrial membranes, the accumulation of phospholipid hydroperoxides can lead to oxidative injury to these biological membranes, ultimately resulting in ferroptosis. Hence, from the perspective of the lipid metabolism in ferroptosis, the inhibition of lipid peroxidation, especially phospholipid peroxidation, is conducive to mitigating ferroptosis. In addition to GPX4, a research has shown that ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) also exhibits a good capability in inhibiting phospholipid peroxidation; the primary mechanism through which FSP1 inhibits phospholipid peroxidation is based on the FSP1-CoQ10-NAD(P)H pathway [42].

Glutathione metabolism

In cells, glutathione primarily exists in two forms: the reduced form (GSH) and the oxidized form (GSSG) [43]. In terms of intracellular glutathione metabolism, HK-2 cells typically exhibit a decrease in intracellular GSH under conditions of ferroptosis [44, 45]. GSH is not only an antioxidant, but also a cofactor of GPX4 [46]. Therefore, the reduction in GSH levels can lead to a decrease in GPX4 activity, consequently resulting in an increased accumulation of the aforementioned phospholipid hydroperoxides. The synthesis of intracellular GSH is linked to the glutamate/cystine antiporter system (system Xc-). The system Xc-, consisting of the light-chain xCT (SLC7A11) and the heavy-chain 4F2 (SLC3A2) [47], transports cystine into the cells by mediating the 1:1 exchange of glutamate inside the cells with cystine outside the cells, and then cystine is reduced to cysteine inside the cells [48]. The cysteine is subsequently combined with glutamate to form γ-glutamylcysteine which is then combined with glycine to form GSH [49]. A study has indicated that the reduced glutathione can alleviate AKI by inhibiting ferroptosis [50].

Morphological features

Ferroptosis exhibits some morphological characteristics that differ from other forms of cell death such as apoptosis and necrosis [3]. In some experimental models of AKI-related ferroptosis, smaller mitochondria [12, 51], increased membrane density of mitochondria [12, 52], and reduced mitochondrial cristae [51, 52] can be observed.

TCMs that regulate AKI-related ferroptosis

Recent researches have found that some ingredients of TCMs can regulate AKI-related ferroptosis by targeting ferroptosis-related targets. Pachymic acid can alleviate ischemia-reperfusion-induced AKI (IRI-AKI) in mice, which may be related to the inhibition of renal ferroptosis; the mechanism by which it inhibits renal ferroptosis in IRI-AKI mice may involve activating the nuclear factor erythroid derived 2 like 2 (NRF2), increasing the expression of SLC7A11, GPX4, and heme oxygenase 1 [53]. Polydatin exerts renal protective effects on cisplatin-induced AKI (CI-AKI) mouse models, which are related to the suppression of ferroptosis by diminishing free iron overload and regulating the system Xc − -GSH-GPx4 axis [54]. Some researchers have found that baicalein can upregulate SIRT1 to lower the acetylation level of p53, thereby suppressing ferroptosis induced by polymyxin B and alleviating AKI [55]. A study has shown that ferroptosis plays a crucial role in AKI associated with rhabdomyolysis, and curcumin can ameliorate rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI by inhibiting ferroptosis [56]. In an experiment using cisplatin to induce AKI in mice, celastrol treatment mitigated CI-AKI, alleviated iron overload, lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial abnormality and ferroptosis in the kidneys; the researchers believed that the mechanism by which celastrol inhibited the ferroptosis in CI-AKI mice kidney was inseparable from NRF2-mediated upregulation of GPX4; additionally, celastrol showed anti-apoptotic effects in CI-AKI mice kidney [51]. In an experiment using sepsis-induced AKI (SI-AKI) rat models, Ginsenoside Rg1 showed the ability to mitigate SI-AKI, reduce iron content, suppress lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, and its inhibitory effect on SI-AKI-associated ferroptosis depends on FSP1; similar results were obtained in the vitro experiment using LPS-induced HK-2 cell injury models [57]. Paeoniflorin can alleviate ferroptosis in IRI-AKI mouse models and hypoxia-reoxygenation-induced HK-2 cell injury models through the Slc7a11-dependent pathway, elucidating a portion of the mechanism of its renal protective effect in IRI-AKI mice [58]. In an experiment using CI-AKI mouse models, leonurine hydrochloride was demonstrated to have the effects of reducing iron overload, suppressing lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis through the Nrf2-dependent pathway, which explained a portion of the mechanism of its renal protective effect against CI-AKI in mice [59]. Tetramethylpyrazine has been reported to alleviate Fe2 + overload and ferroptosis, as well as to play a renal protective role in contrast medium-induced rat AKI models and HK-2 cell injury models, and TfR may serve as a pivotal target for regulating ferroptosis in contrast medium-induced AKI by Tetramethylpyrazine [60]; moreover, tetramethylpyrazine showed the ability to inhibit apoptosis of renal tubular cell in contrast medium-induced rat AKI models [61].

Relatively few studies have been conducted on the regulation of AKI-related ferroptosis by TCM formulations. In an experiment using CI-AKI mouse models, it was observed that Shenhuaifu Granule could mitigate CI-AKI by inhibiting ferroptosis, and the researchers held the viewpoint that the mechanism through which Shenshuaifu Granule exerted this effect might be associated with modulating the p53/SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway [62]. In another experiment using CI-AKI mouse models, it was observed that Jiedu Huoxue Decoction could inhibit ferroptosis and alleviate CI-AKI, and its underlying mechanism might involve regulation of the Yes-associated protein/acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 signaling pathway [63].

Conclusion

TCMs once played a crucial role in the therapeutic history of AKI in China, particularly in the times when renal replacement therapy was scarce in China. Even at present, TCMs remains a significant means for treating AKI by Chinese physicians.

Ferroptosis plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AKI resulting from various etiologies, involving various metabolic processes such as iron metabolism and lipid metabolism. Many TCM ingredients have shown reliable effects in mitigating ferroptosis in various AKI models. The process of ferroptosis can be considered as a disturbance of the balance between lipid peroxidation and anti-lipid peroxidation, and many targets involved in the regulation of AKI-related ferroptosis by various TCM ingredients are associated with anti-lipid peroxidation, such as NRF2, SLC7A11, GPX4, and FSP1. Certainly, reducing iron accumulation is also crucial for the mechanism through which many TCM ingredients regulate AKI-related ferroptosis, as it diminishes the generation of lipid peroxides. In addition to regulating ferroptosis, certain TCM ingredients also have the ability to modulate other types of cell death, such as apoptosis; these TCM ingredients alleviate AKI through a comprehensive pharmacological mechanism. Therefore, some cross-targets shared by ferroptosis and other types of cell death may play a key role in the mechanisms of TCMs treating AKI.

At present, in terms of TCM regulation of AKI-related ferroptosis, the following issues still require further research in the future. Firstly, the detailed mechanisms by which various etiologies lead to an increase in intracellular iron levels in HK-2 cells during ferroptosis have not been fully elucidated; although iron metabolism-related proteins are involved, some upstream mechanisms still need to be explored in the future, and there may exist some targets for TCMs to regulate the intracellular iron levels of HK-2 cells within these upstream mechanisms. Secondly, as of now, researches on AKI-related ferroptosis regulated by TCMs primarily focus on the study of TCM monomers, with relatively fewer studies investigating TCM formulas. However, TCMs are primarily utilized in the form of formulas rather than individual monomers for treating AKI in the clinical practice in China. In order to align with clinical practical applications, further research is necessary to investigate the regulation of AKI-related ferroptosis by TCM formulas. We can investigate the key mechanisms by which these TCM formulas regulate ferroptosis, providing theoretical references for developing more effective TCM formulas for treating AKI in the future.

In conclusion, TCMs holds significant research potential and promising prospects for regulating AKI-related ferroptosis, and it is worth our efforts to explore further.

Author contributions

TP conducted an extensive search for relevant literatures and made major contributions to the manuscript writing; MQL directed the topic selection, provided writing guidance, critically revised the manuscript, and ensured the academic quality of the manuscript. The final manuscript submitted for publication was reviewed and approved by both TP and MQL.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, 82274482.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Martin-Sanchez D, Ruiz-Andres O, Poveda J, Carrasco S, Cannata-Ortiz P, Sanchez-Nino MD et al (2017) Ferroptosis, but not necroptosis, is important in nephrotoxic folic acid-induced AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 28(1):218–229. 10.1681/ASN.2015121376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linkermann A, Skouta R, Himmerkus N, Mulay SR, Dewitz C, De Zen F et al (2014) Synchronized renal tubular cell death involves ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(47):16836–16841. 10.1073/pnas.1415518111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE et al (2012) Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149(5):1060–1072. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JJ, Zhang TY, Qi YH, Zhu MY, Fang Y, Qi CJ et al (2024) Efficacy and safety of Yiqi Peiyuan granules for improving the short-term prognosis of patients with acute kidney injury: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. J Integr Med 22(3):279–285. 10.1016/j.joim.2024.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao S, Chen Y, Wang S, Wang C, Ye C (2024) Shenkang injection for the treatment of acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail 46(1):2338566. 10.1080/0886022X.2024.2338566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuxi Q, Zhang H, Baili Y, Shi S (2017) Effects of Xuebijing injection for patients with sepsis-induced acute kidney injury after Wenchuan earthquake. Altern Ther Health Med 23(2):36–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H, Luo X, He Y, Qu B, Zhao L, Li M (2020) Shenshuaikang enema, a Chinese herbal remedy, inhibited hypoxia and reoxygenation-induced apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells by inhibiting oxidative damage-dependent JNK/caspase-3 signaling pathways using network pharmacology. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020:9457101. 10.1155/2020/9457101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye N, Xie D, Yang B, Li M (2020) The mechanisms of the herbal components of CRSAS on HK-2 cells in a hypoxia/reoxygenation model based on network pharmacology. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020:5352490. 10.1155/2020/5352490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang YB, Jiang L, Liu XQ, Wang X, Gao L, Zeng HX et al (2022) Melatonin alleviates acute kidney injury by inhibiting NRF2/Slc7a11 axis-mediated ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022:4776243. 10.1155/2022/4776243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda Y, Hamano H, Horinouchi Y, Miyamoto L, Hirayama T, Nagasawa H et al (2021) Role of ferroptosis in cisplatin-induced acute nephrotoxicity in mice. J Trace Elem Med Biol 67:126798. 10.1016/j.jtemb.2021.126798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Wang B, Wu S, Dong S, Jiang G, Huang Y et al (2023) Ferroptosis is involved in polymyxin B-induced acute kidney injury via activation of p53. Chem Biol Interact 378:110479. 10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao J, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Xu H, Ye Y, Li L et al (2021) Maresin conjugates in tissue regeneration-1 suppresses ferroptosis in septic acute kidney injury. Cell Biosci 11(1):221. 10.1186/s13578-021-00734-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stockwell BR, Friedmann AJ, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ et al (2017) Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell 171(2):273–285. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song Z, Li Z, Pan T, Liu T, Gong B, Wang Z et al (2024) Protopanaxadiol prevents cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by regulating ferroptosis. J Pharm Pharmacol 76(7):884–896. 10.1093/jpp/rgae050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du YW, Li XK, Wang TT, Zhou L, Li HR, Feng L et al (2023) Cyanidin-3-glucoside inhibits ferroptosis in renal tubular cells after ischemia/reperfusion injury via the AMPK pathway. Mol Med 29(1):42. 10.1186/s10020-023-00642-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee D, Son E, Kim YH (2022) Transferrin-mediated increase of labile iron pool following simulated ischemia causes lipid peroxidation during the early phase of reperfusion. Free Radic Res 56(11–12):713–729. 10.1080/10715762.2023.2169683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang D, Kroemer G (2020) Ferroptosis. Curr Biol 30(21):R1292–R1297. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galy B, Conrad M, Muckenthaler M (2024) Mechanisms controlling cellular and systemic iron homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 25(2):133–155. 10.1038/s41580-023-00648-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown CW, Amante JJ, Chhoy P, Elaimy AL, Liu H, Zhu LJ et al (2019) Prominin2 drives ferroptosis resistance by stimulating iron export. Dev Cell 51(5):575–586. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawabata H (2019) Transferrin and transferrin receptors update. Free Radic Biol Med 133:46–54. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemadi M, Kahn PH, Miquel G, El HCJ (2004) Transferrin’s mechanism of interaction with receptor 1. Biochemistry-Us 43(6):1736–1745. 10.1021/bi030142g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dautry-Varsat A, Ciechanover A, Lodish HF (1983) pH and the recycling of transferrin during receptor-mediated endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 80(8):2258–2262. 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohgami RS, Campagna DR, Greer EL, Antiochos B, Mcdonald A, Chen J et al (2005) Identification of a ferrireductase required for efficient transferrin-dependent iron uptake in erythroid cells. Nat Genet 37(11):1264–1269. 10.1038/ng1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabuchi M, Yoshimori T, Yamaguchi K, Yoshida T, Kishi F (2000) Human NRAMP2/DMT1, which mediates iron transport across endosomal membranes, is localized to late endosomes and lysosomes in HEp-2 cells. J Biol Chem 275(29):22220–22228. 10.1074/jbc.M001478200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang X (2015) Glutaminolysis and transferrin regulate ferroptosis. Mol Cell 59(2):298–308. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levi S, Luzzago A, Cesareni G, Cozzi A, Franceschinelli F, Albertini A et al (1988) Mechanism of ferritin iron uptake: activity of the H-chain and deletion mapping of the ferro-oxidase site. A study of iron uptake and ferro-oxidase activity of human liver, recombinant H-chain ferritins, and of two H-chain deletion mutants. J Biol Chem 263(34):18086–18092 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bou-Abdallah F, Zhao G, Mayne HR, Arosio P, Chasteen ND (2005) Origin of the unusual kinetics of iron deposition in human H-chain ferritin. J Am Chem Soc 127(11):3885–3893. 10.1021/ja044355k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asano T, Komatsu M, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Ishikawa F, Mizushima N, Iwai K (2011) Distinct mechanisms of ferritin delivery to lysosomes in iron-depleted and iron-replete cells. Mol Cell Biol 31(10):2040–2052. 10.1128/MCB.01437-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW, Kimmelman AC (2014) Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature 509(7498):105–109. 10.1038/nature13148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J, Jiang X (2016) Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res 26(9):1021–1032. 10.1038/cr.2016.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montosi G, Donovan A, Totaro A, Garuti C, Pignatti E, Cassanelli S et al (2001) Autosomal-dominant hemochromatosis is associated with a mutation in the ferroportin (SLC11A3) gene. J Clin Invest 108(4):619–623. 10.1172/JCI13468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bao WD, Pang P, Zhou XT, Hu F, Xiong W, Chen K et al (2021) Loss of ferroportin induces memory impairment by promoting ferroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Differ 28(5):1548–1562. 10.1038/s41418-020-00685-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu S, Song Y, Luo R, Li S, Li G, Wang K et al (2021) Ferroportin-dependent iron homeostasis protects against oxidative stress-induced nucleus pulposus cell ferroptosis and ameliorates intervertebral disc degeneration in vivo. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021:6670497. 10.1155/2021/6670497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, Vaughn MB, Donovan A, Ward DM et al (2004) Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 306(5704):2090–2093. 10.1126/science.1104742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammad G, Matakidou A, Robbins PA, Lakhal-Littleton S (2021) The kidney hepcidin/ferroportin axis controls iron reabsorption and determines the magnitude of kidney and systemic iron overload. Kidney Int 100(3):559–569. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Zheng X, Zhang J, Zhao S, Wang Z, Wang F et al (2018) Physiological functions of ferroportin in the regulation of renal iron recycling and ischemic acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315(4):F1042–F1057. 10.1152/ajprenal.00072.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soofi A, Li V, Beamish JA, Abdrabh S, Hamad M, Das NK et al (2024) Renal-specific loss of ferroportin disrupts iron homeostasis and attenuates recovery from acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 326(2):F178–F188. 10.1152/ajprenal.00184.2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JY, Kim WK, Bae KH, Lee SC, Lee EW (2021) Lipid metabolism and ferroptosis. Biology (Basel) 10(3):184. 10.3390/biology10030184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imai H, Nakagawa Y (2003) Biological significance of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx, GPx4) in mammalian cells. Free Radic Biol Med 34(2):145–169. 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01197-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ursini F, Maiorino M, Valente M, Ferri L, Gregolin C (1982) Purification from pig liver of a protein which protects liposomes and biomembranes from peroxidative degradation and exhibits glutathione peroxidase activity on phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides. Biochim Biophys Acta 710(2):197–211. 10.1016/0005-2760(82)90150-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ursini F, Maiorino M, Gregolin C (1985) The selenoenzyme phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta 839(1):62–70. 10.1016/0304-4165(85)90182-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, Da SM, Ingold I et al (2019) FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature 575(7784):693–698. 10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lv H, Zhen C, Liu J, Yang P, Hu L, Shang P (2019) Unraveling the potential role of glutathione in multiple forms of cell death in cancer therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019:3150145. 10.1155/2019/3150145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong XQ, Chu LK, Cao X, Xiong QW, Mao YM, Chen CH et al (2023) Glutathione metabolism rewiring protects renal tubule cells against cisplatin-induced apoptosis and ferroptosis. Redox Rep 28(1):2152607. 10.1080/13510002.2022.2152607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang F, Wang Y, Lv X, Huang C (2024) WTAP-mediated N6-methyladenosine modification promotes the inflammation, mitochondrial damage and ferroptosis of kidney tubular epithelial cells in acute kidney injury by regulating LMNB1 expression and activating NF-kappaB and JAK2/STAT3 pathways. J Bioenerg Biomembr 56(3):285–296. 10.1007/s10863-024-10015-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Averill-Bates DA (2023) The antioxidant glutathione. Vitam Horm 121:109–141. 10.1016/bs.vh.2022.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tu H, Tang LJ, Luo XJ, Ai KL, Peng J (2021) Insights into the novel function of system Xc- in regulated cell death. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 25(3):1650–1662. 10.26355/eurrev_202102_24876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conrad M, Sato H (2012) The oxidative stress-inducible cystine/glutamate antiporter, system x (c) (-): cystine supplier and beyond. Amino Acids 42(1):231–246. 10.1007/s00726-011-0867-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu SC (2013) Glutathione synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1830(5):3143–3153. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He L, Shi Y (2023) Reduced glutathione ameliorates acute kidney injury by inhibiting ferroptosis. Mol Med Rep 27(6):123. 10.3892/mmr.2023.13011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan M, Wang Z, Wang Y, Jiang X, Fan Y, Gong F et al (2023) Celastrol alleviated acute kidney injury by inhibition of ferroptosis through Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 166:115333. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ye Y, Chen Y, Wu H, Fu Y, Sun Y, Wang X et al (2023) Investigations into ferroptosis in methylmercury-induced acute kidney injury in mice. Environ Toxicol 38(6):1372–1383. 10.1002/tox.23770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang GP, Liao YJ, Huang LL, Zeng XJ, Liao XH (2021) Effects and molecular mechanism of pachymic acid on ferroptosis in renal ischemia reperfusion injury. Mol Med Rep 23(1):63. 10.3892/mmr.2020.11704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou L, Yu P, Wang TT, Du YW, Chen Y, Li Z et al (2022) Polydatin attenuates cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022:9947191. 10.1155/2022/9947191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu M, Li H, Wang B, Wu Z, Wu S, Jiang G et al (2023) Baicalein ameliorates polymyxin B-induced acute renal injury by inhibiting ferroptosis via regulation of SIRT1/p53 acetylation. Chem Biol Interact 382:110607. 10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guerrero-Hue M, Garcia-Caballero C, Palomino-Antolin A, Rubio-Navarro A, Vazquez-Carballo C, Herencia C et al (2019) Curcumin reduces renal damage associated with rhabdomyolysis by decreasing ferroptosis-mediated cell death. Faseb J 33(8):8961–8975. 10.1096/fj.201900077R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo J, Wang R, Min F (2022) Ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting ferroptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells. J Leukoc Biol 112(5):1065–1077. 10.1002/JLB.1A0422-211R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma L, Liu X, Zhang M, Zhou L, Jiang L, Gao L et al (2023) Paeoniflorin alleviates ischemia/reperfusion induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting Slc7a11-mediated ferroptosis. Int Immunopharmacol 116:109754. 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.109754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu J, Gu W, Ma N, Fan X, Ci X (2022) Leonurine alleviates ferroptosis in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by activating the Nrf2 signalling pathway. Br J Pharmacol 179(15):3991–4009. 10.1111/bph.15834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Z, Li J, Song Z, Li T, Li Z, Gong X (2024) Tetramethylpyrazine attenuates renal tubular epithelial cell ferroptosis in contrast-induced nephropathy by inhibiting transferrin receptor and intracellular reactive oxygen species. Clin Sci (Lond) 138(5):235–249. 10.1042/CS20231184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gong X, Wang Q, Tang X, Wang Y, Fu D, Lu H et al (2013) Tetramethylpyrazine prevents contrast-induced nephropathy by inhibiting p38 MAPK and FoxO1 signaling pathways. Am J Nephrol 37(3):199–207. 10.1159/000347033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin X, He R, Lin Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Li Z et al (2023) Shenshuaifu granule attenuates acute kidney injury by inhibiting ferroptosis mediated by p53/SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther 17:3363–3383. 10.2147/DDDT.S433994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng R, Tian RM, Huang LH, Wang XW, Guo S, Wu AJ et al (2024) Effect and mechanism of Jiedu Huoxue decoction in regulating YAP/ACSL4 pathway to inhibit ferroptosis in treatment of acute kidney injury. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 49(1):151–161. 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20230829.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.