Summary

Background

Haematologic malignancies accounted for 6.6% of total cancer cases and 7.2% of total cancer-related deaths worldwide in 2022. We implemented a novel approach to estimate the lifetime risk of developing and dying from various types of haematologic malignancies at the global, regional and country-specific perspectives in 2022.

Methods

We retrieved incidence and mortality rates for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), multiple myeloma (MM) and leukaemia from GLOBOCAN 2022 of 185 countries, along with the national population statistics and all-cause mortality data sourced from the United Nations. For trend analysis, we obtained consecutive cancer registry data spanning from 2003 to 2017 from the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) Plus database. After quality control, datasets from 30 countries were included. We used the “adjusted for multiple primaries (AMP)” method to calculate the lifetime risk of incidence (LRI) and mortality (LRM) by cancer type, selected age interval, sex, country and geographic region.

Findings

In 2022, the global lifetime risk of incidence (LRI) and mortality (LRM) for all haematologic malignancies was 1.67% and 0.98%, respectively. LRI was highest for NHL, whereas the LRM was highest for leukaemia. On a general level, males exhibited higher LRI and LRM compared to females. Both LRI and LRM increased with higher Human Development Index (HDI) levels. The LRI and LRM for haematologic malignancies were notably high in regions such as Australia/New Zealand, Northen America, as well as Northen, Western and Southern Europe, whereas they were comparatively low in Middle, Western and Eastern Africa. We observed about 5-fold regional disparity in the LRI/LRM ratio for HL, ranging from 1.50 in Middle Africa to 7.67 in Western Europe. Individuals aged 60 and above still faced 71.26% and 78.57% remaining risks for developing and dying from all haematologic malignancies. Among the 185 countries studied, NHL was the haematologic malignancy with the highest LRI in 68.65% of the countries. However, leukaemia had the highest LRM in 58.92% of these countries. MM exhibited the highest LRI and LRM particularly in islands surrounding the Caribbean Sea. Out of 30 countries with eligible consecutive cancer surveillance data, 24 exhibited significant upward trends in LRI of all haematologic malignancies, with AAPCs ranging from 0.5% in USA to 4.3% in Latvia. 25 countries showed significant upward trends in LRM, with AAPCs ranging from 1.0% in USA to 5.5% in Republic of Korea.

Interpretation

The global lifetime risks of haematologic malignancies exhibit considerable variations across different world regions, necessitating country-specific and targeted decision-making strategies. In contrast to traditional indicators, the compositive lifetime risks provide intuitive measures with profound public health implications, offering fresh insights into the development of regional disease prevention and control strategies.

Funding

CAMS Innovation Funds for Medical Sciences (No. 2021-I2M-1-061, No. 2021-I2M-1-011).

Keywords: Lifetime risk, Haematologic malignancies, Hodgkin lymphoma, Non-hodgkin lymphoma, Multiple myeloma, Leukaemia, Incidence, Mortality

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, and Embase for articles published between Jan 1, 1950, and Nov 30th, 2024 using terms (“haematological malignancies” OR “Hodgkin lymphoma” OR “Non-Hodgkin lymphoma” OR “multiple myeloma” OR “immunoproliferative diseases” OR “leukaemia”) AND (“lifetime risk” OR “lifetime probability”). We found that although haematologic malignancies rank as one of the common cancers worldwide, the global epidemiology of haematologic malignancies incidence and mortality were not fully discussed before. Lifetime risk was a measure of the cumulative risk of a certain disease over a specific age range, but it was rarely used in the global epidemiological description of haematologic malignancies.

Added value of this study

We carried out a study to quantify the lifetime risk of developing (LRI) or dying from (LRM) haematologic malignancies across 185 countries at the global, regional and national levels using the recently published GLOBOCAN 2022 data and Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) Plus database, and reported the temporal analysis of LRI and LRM by cancer type. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma was the haematologic malignancy with the highest LRI, whereas leukaemia demonstrated the highest LRM in the majority of countries. We observed a 5-fold disparity of LRI/LRM ratio of Hodgkin lymphoma across countries, and multiple myeloma was the haematologic malignancy that most likely to develop or to die from in islands surrounding Caribbean Sea.

Implications of all the available evidence

By incorporating competing risks of death, multiple primaries, and life expectancy into the calculation of LRI and LRM, reasonable results can be obtained in temporal and trend analyses. Additionally, this indicator is intuitive and easily understandable, and can be utilized for comparing disease burden across different populations. More valuably, the observed variations in the lifetime risks of haematologic malignancies facilitate the identification of regions in greatest need for improved access to haematologic care.

Introduction

Haematologic malignancies accounted for 6.6% of total cancer cases and 7.2% of total cancer-related deaths in 2022.1 Global estimates indicated that during the past 30 years, the incident cases and deaths with haematologic malignancies increased significantly, but the trends varied by cancer type, sex, age, region and social economic development level.2, 3, 4 Haematologic malignancies pose significant threats to people’s lives. However, on a global scale, there is relatively scant epidemiological analysis concerning haematologic malignancies. Crucial epidemiological evidences are still needed to systematically evaluate the health impact of haematologic malignancies on population level, which can further be translated into public health policies and disease prevention and control programmes.

The lifetime risk denotes the probability of an individual developing or dying from a specific disease throughout his entire lifespan. This indicator can comprehensively reflect the population’s risk so as to help identify public health issues with high priority and to provide critical clues for disease control strategy making. Since it can also be employed to evaluate individual risk, lifetime risk serves as an intuitive and readily understood indicator which could be used for effective public communication and education.5 Consequently, compared with other frequently-used descriptive epidemiologic indices such as incidence and mortality rates, this indicator boasts a broader range of application scenarios.

Traditionally, the cumulative risk has been the most frequently used algebraic approximation for assessing lifetime risk in the context of global cancer-related disease burden analysis.6 However, a significant limitation of this approach lies in its reliance solely on age-specific incidence or mortality rates, which introduces biases, particularly in countries with longer life expectancies. The “adjusted for multiple primaries (AMP)” method offers an intuitive assessment of an individual’s lifetime risk of a certain disease. Compared with cumulative risks, this estimation took competing risks of death, multiple primaries and life expectancy into consideration, and can be directly used for comparison across populations.7,8

Through literature search, we found that the global landscape of lifetime risk of haematologic malignancies was not fully depicted in the past. Thus, in this paper, we present the lifetime risk of developing and dying from different types of haematologic malignancies at the global, regional and national level using the most updated GLOBOCAN 2022 cancer incidence and mortality data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

Methods

Data sources

The original data of new cancer cases, deaths and population by sex and age group (0–4, 5–9, …, 65–69, 70–84, and 85+) in 185 countries were obtained from GLOBOCAN 2022, which represents the most recent global cancer burden estimates produced by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). The data sources and methods employed in compiling the GLOBOCAN estimates are comprehensively described online at the Global Cancer Observatory (GCO) (https://gco.iarc.who.int). In brief, the national estimates for 36 cancer types and all cancers combined are derived from the most available sources of cancer incidence and mortality data within each country. The 2022 estimates primarily rely on short-term predictions and modeled mortality-to-incidence ratios, with the results being presented according to country or territory, geographical region, sex and age group.1

Cancer types were classified according to the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Cases and deaths for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL, ICD-10: C81), Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL, ICD-10: C82–86, C88), multiple myeloma (MM, ICD-10: C90) and leukaemia (ICD-10: C91–95) were extracted. The national population statistics and all-cause mortality data were obtained from the United Nations (World Population Prospects 2019, https://population.un.org/wpp/).9

For trend analysis, we obtained consecutive cancer registry data spanning from 2003 to 2017 from the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) Plus database (https://ci5.iarc.fr/ci5plus/), which is part of the CI5 series. The data sources and quality control methods employed in CI5plus were identical to CI5 database, which serves as the foundation for GLOBOCAN estimations. All included registries comply with IARC’s data quality control standards, which are assessed in terms of data comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. After excluding countries with incomplete population data for certain age groups and those reporting fewer than 10 cases annually for each type of haematologic cancer, we were left with 30 countries that had concurrent incidence data for all four haematologic cancers. These countries were subsequently included in the trend analysis. To calculate the number of haematologic cancer deaths for these countries, we multiplied the mortality - to - incidence ratio provided in GLOBOCAN 2022 by the number of cases listed in CI5 Plus, stratified by cancer type, age group, sex, and year. Similarly, the number of all-cause deaths were calculated by multiplying the all-cause mortality rates from the United Nations by the population data from CI Plus, again stratified by age group, sex, and year.

We obtained the country-level Human Development Index (HDI) data from the United Nations Development Programme (https://hdr.undp.org/),10 which is a composite indicator of life expectancy, literacy and per capita gross domestic product and is widely used to measure the socioeconomic development and well-being of a country/region.

The Ethical Committee of the National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College waived the need for ethical approval or informed consent for this study.

Statistical methods

We used the “adjusted for multiple primaries (AMP)” method to calculate the lifetime risk. Details of this method was described previously5 and can also be found in the Supplementary Appendix file. In brief, the AMP method used data on all-cause mortality, disease-specific incidence and mortality, categorized by 5-year age groups, to cumulatively calculate the lifetime risk of incidence (LRI) and mortality (LRM) for this disease. The LRI and LRM represent the probabilities of individuals developing or dying from this specific disease throughout their entire or a particular lifetime, based on the population estimates from which they originate. To improve clarity, we substituted the phrase “the lifetime risk of developing a disease” for LRI and “the lifetime risk of dying from a disease” for LRM.

We calculated the LRI and LRM for haematologic malignancies by cancer type (all haematologic malignancies, HL, NHL, MM, leukaemia), selected age interval (birth to death, 40 years to death, 50 years to death, 60 years to death, 70 years to death), sex (both, male, female) and country. We divided 185 countries into quartiles according to their HDI and calculated the lifetime risk by HDI (very high, high, medium, low). We classified the world into 20 predefined geographic regions11 and calculated the lifetime risk for each region by pooling the data of countries within the region together.

We calculated the quotient of lifetime risk of developing a disease and the lifetime risk of dying from that disease (LRI/LRM ratio) to depict the variance of the risk of incidence and mortality of a disease in certain population. We calculated the quotient of lifetime risks within 60 years to death and the lifetime risks from birth to death (60-to-whole risk proportion) to depict the remaining risks for the elderly (population over 60 years old). In sensitivity analyses, we compared the lifetime risks of haematologic malignancies with the cumulative risks of haematologic malignancies for the age group of 0–74 years. Trend analysis was conducted by Joinpoint software, version 4.6.0.0 (Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, USA), and the average annual percent change (AAPC) were report. Other analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). World maps were created using QGIS software, version 3.61.

Role of the funding source

The funder of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report.

Results

In 2022, the global lifetime risk of developing (LRI) and dying from (LRM) all haematologic malignancies was 1.67% (95% CI: 1.67–1.68) and 0.98% (95% CI: 0.97–0.98) respectively. Cancer-specific analysis indicated that the LRI was highest for NHL (0.73%), followed by leukaemia (0.60%), MM (0.27%) and HL (0.08%), whereas the LRM was highest for leukaemia (0.41%), followed by NHL (0.36%), MM (0.18%) and HL (0.03%). The LRIs and LRMs were higher in males compared to females within most groups of HL, NHL and leukaemia. However, the LRIs and LRMs of MM were higher in females in Eastern and Southern Africa, Eastern Europe, Caribbean and Micronesia/Polynesia (Table 1, Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Table 1.

Lifetime risks (%) of developing and dying from haematologic malignancies in 2022, by sex.

| Type | Population | Haematologic malignancies | Hodgkin lymphoma | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Multiple myeloma | Leukaemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRI | Total | 1.67 (1.67–1.68) | 0.08 (0.08–0.09) | 0.73 (0.72–0.73) | 0.27 (0.26–0.27) | 0.60 (0.60–0.60) |

| Male | 1.79 (1.78–1.79) | 0.10 (0.09–0.10) | 0.77 (0.76–0.77) | 0.28 (0.28–0.28) | 0.65 (0.65–0.66) | |

| Female | 1.54 (1.53–1.54) | 0.07 (0.07–0.07) | 0.68 (0.67–0.68) | 0.25 (0.25–0.25) | 0.54 (0.54–0.55) | |

| LRM | Total | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | 0.03 (0.03–0.03) | 0.36 (0.36–0.36) | 0.18 (0.18–0.18) | 0.41 (0.41–0.41) |

| Male | 1.04 (1.04–1.05) | 0.03 (0.03–0.03) | 0.39 (0.38–0.39) | 0.19 (0.19–0.19) | 0.44 (0.43–0.44) | |

| Female | 0.89 (0.89–0.90) | 0.02 (0.02–0.02) | 0.33 (0.32–0.33) | 0.17 (0.17–0.17) | 0.37 (0.37–0.37) |

HDI: Human Development Index. LRI: Lifetime risk of incidence, referring to the lifetime risk of developing a certain disease. LRM: Lifetime risk of mortality, referring to the lifetime risk of dying from a certain disease.

The lifetime risks increased with HDI levels within most groups, with the exception that the LRI of HL and the LRMs of HL and NHL were higher in low HDI regions compared to Medium HDI regions. Similar results were found both in males and females (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Regionally, the LRI of all haematologic malignancies ranged from the highest in Australia/New Zealand (5.68%) to the lowest in Middle Africa (0.50%). The LRI of all haematologic malignancies was higher in higher-developed regions, including Australia/New Zealand (5.68%), Northen America (4.79%), Northen Europe (4.57%), Western Europe (4.39%), and Southern Europe (3.77%). It was lower than 3.00% in other regions, including all regions in Asia and Africa, Eastern Europe, South and Central America, Micronesia/Polynesia, Caribbean and Melanesia (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Lifetime risks (%) of developing or dying from all haematologic malignancies in 2022 by region and country, both sexes. Notes: A. Developing (LRI) all haematologic malignancies; B. Dying from (LRM) all haematologic malignancies. Green diamonds indicate the average lifetime risk of all haematologic malignancies in each selected geographic region; vertical lines represent the estimated lifetime risk of all haematologic malignancies in each selected country, with the name of the country representing the one with the lowest or highest risk within that geographic region.

The LRM of all haematologic malignancies ranged from the highest in Australia/New Zealand (2.72%) to the lowest in Middle Africa (0.39%). On a general level, the regional rankings for the LRM were similar with that for the LRI, with a few exceptions. To clearly illustrate the slightly different regional distribution of these two indicators, we calculated the LRI/LRM ratio for each region. Northern America ranked the first with an LRI/LRM ratio of 2.52. The LRI/LRM ratios were high in Northern Europe (2.11), Australia/New Zealand (2.09) and Western Europe (1.93). The LRI/LRM ratio for most regions in Africa was low, ranging from 1.28 to 1.40. Similar results were found both in males and females (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

The regional distribution was similar for HL (LRI range: <0.01% in Micronesia/Polynesia to 0.25% in Northern Europe; LRM range: <0.01% in Micronesia/Polynesia to 0.07% in Western Asia), NHL (LRI range: 0.25% in Western Africa to 2.36% in Australia/New Zealand; LRM range: 0.17% in South-Central Asia to 0.98% in Australia/New Zealand), MM (LRI range: 0.06% in Western Africa to 0.98% in Australia/New Zealand; LRM range: 0.05% in Western Africa to 0.59% in Australia/New Zealand), and Leukaemia (LRI range: 0.14% in Middle and Western Africa to 2.20% in Australia/New Zealand; LRM range: 0.12% in Middle and Western Africa to 1.11% in Australia/New Zealand) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The regional lifetime risks of developing and dying from haematologic malignancies by cancer type were displayed in Supplementary Figs. S1–S5.

The LRI/LRM ratio of HL, NHL, MM and leukaemia was high in Northern America, Australia/New Zealand and Europe, medium in Asia, Central and South America, Caribbean and Micronesia/Polynesia, and low in Africa and Melanesia. The greatest disparity of LRI/LRM ratio was observed in HL, which ranged from 1.50 in Middle Africa to 7.67 in Western Europe (Supplementary Table S4).

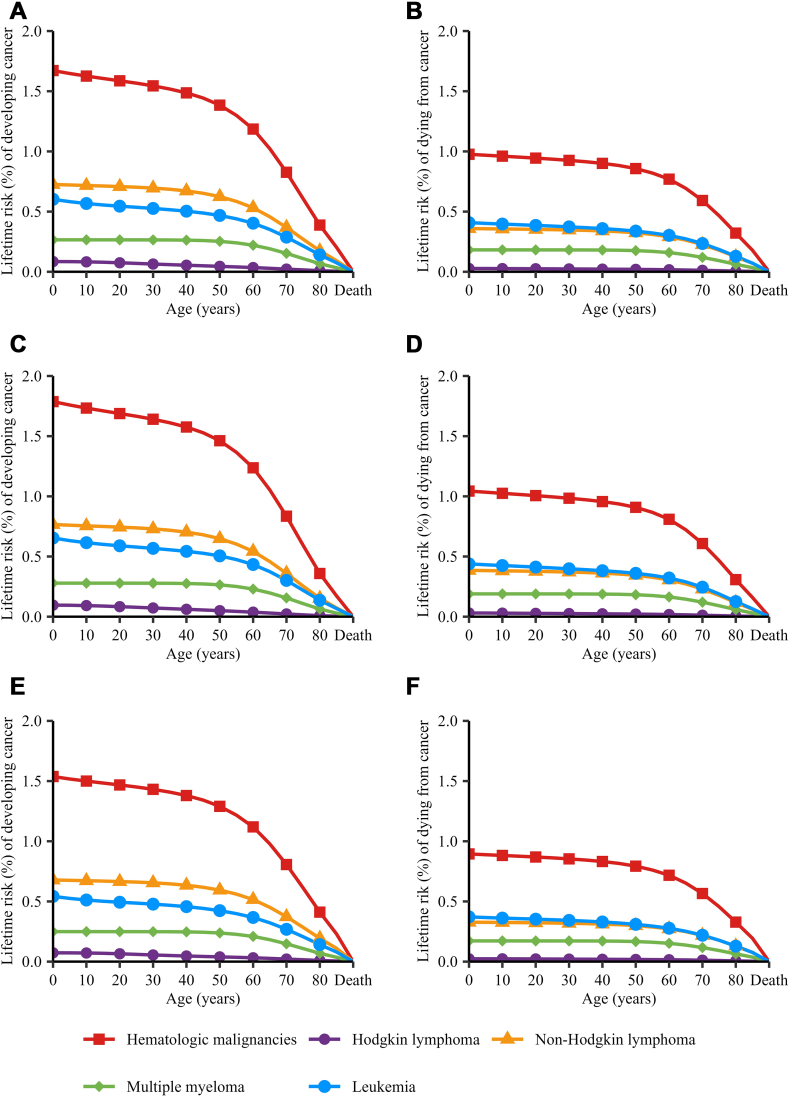

On a global scale, the risks of developing and dying from all haematologic malignancies decreased as age progressed. However, this declining trend was not pronounced in individuals below 40 years of age, suggesting that the LRI and LRM from birth to 40 years were relatively low. The rate of decrease became more pronounced afterwards, with a significant decline observed particularly in those aged 60 and above (Fig. 2). To better depict the remaining risk for the elder, we calculated the 60-years to death/birth to death risk proportion (60-to-whole risk proportion). We found that the population over 60 years old still had 71.26% and 78.57% remaining risks of developing or dying from haematologic malignancies. When analysed by cancer type, the population over 60 years old had 37.50%, 72.60%, 81.48% and 66.67% remaining risks of developing HL, NHL, MM and leukaemia, and had 66.67%, 80.56%, 88.89% and 73.17% remaining risks of dying from HL, NHL, MM and leukaemia (Supplementary Table S5). When analysed by HDI level, we found that the remaining risks for population over 60 years old increased with HDI level upon most occasions. However, the remaining risks of developing HL and dying from HL and NHL for population over 60 years old were higher in low HDI region than in medium HDI region (Supplementary Figs. S6–S35 and Tables S6–S15).

Fig. 2.

Lifetime risks (%) of developing or dying from haematologic malignancies in 2022, by age interval, sex and cancer type. Notes: A. Developing (LRI) haematologic malignancies in both sexes; B. Dying from (LRM) haematologic malignancies in both sexes; C. Developing (LRI) haematologic malignancies in males; D. Dying from (LRM) haematologic malignancies in males; E. Developing (LRI) haematologic malignancies in females; F. Dying from (LRM) haematologic malignancies in females.

Nationally, the LRI of all haematologic malignancies, HL, NHL, MM and leukaemia was highest in Canada, Ireland, Denmark, France, Martinique and Australia. The LRM of all haematologic malignancies was highest in Cyprus. The LRM of HL, NHL, MM and leukaemia was highest in United Arab Emirates, Canada, France, Martinique and Cyprus (Fig. 3). The national lifetime risk of developing and dying from haematologic malignancies were also displayed in Supplementary Figs. S36–S41 and Tables S16 and S17.

Fig. 3.

The global landscape of lifetime risks (%) of developing or dying from all haematologic malignancies in 2022, both sexes. Notes: A. Developing (LRI) all haematologic malignancies; B. Dying from (LRM) all haematologic malignancies.

When analysed by cancer type, NHL was the haematologic malignancy with the highest LRI in 68.65% of the 185 countries studied, followed by leukaemia (29.73%) and MM (1.62%). However, leukaemia was the haematologic malignancy with the highest LRM in 58.92% of the 185 countries studied, followed by NHL (39.46%) and MM (1.62%). Similar results were found in both sexes. We found that MM was the haematologic malignancy with the highest LRI in Bahamas, France Guadeloupe and France Martinique, and was the one with the highest LRM in Bahamas, France Guadeloupe and Jamaica, all of which were islands around Caribbean Sea (Supplementary Tables S18 and S19).

In trend analysis, we observed that out of 30 countries with eligible consecutive cancer surveillance data, 24 (80.00%) exhibited significant upward trends in LRI of all haematologic malignancies, with AAPCs ranging from 0.5% in USA to 4.3% in Latvia. The most rapid increase was observed in the LRI of HL among females in Japan, with an AAPC of 8.0%. Conversely, the LRI of most haematologic malignancies in Costa Rica exhibited a significant decline. Similarly, 25 (83.33%) countries showed significant upward trends in LRM of all haematologic malignancies, with AAPCs ranging from 1.0% in USA to 5.5% in Republic of Korea. The most rapid increase was observed in the LRM of MM among females in Republic of Korea, with an AAPC of 7.7%. The LRM of most haematologic malignancies in Costa Rica exhibited a significant decline (Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables S20 and S21). The trends in the LRI and LRM for each country were illustrated in Supplementary Figs S42 and S43.

Fig. 4.

The average annual percent change (AAPC) for lifetime risks of developing or dying from all haematologic malignancies from 2003 to 2017 by country, both sexes. Notes: A. Developing (LRI) all haematologic malignancies; B. Developing (LRI) Hodgkin lymphoma; C. Developing (LRI) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; D. Developing (LRI) multiple myeloma; E. Developing (LRI) leukaemia; F. Dying from (LRM) all haematologic malignancies; G. Dying from (LRM) Hodgkin lymphoma; H. Dying from (LRM) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; I. Dying from (LRM) multiple myeloma; J. Dying from (LRM) leukaemia. Dark red bars represent countries with a statistically significant increasing trend (AAPC > 0, p < 0.05). Light red bars represent countries with an increasing trend that is not statistically significant (AAPC > 0, p ≥ 0.05). Dark blue bars represent countries with a statistically significant decreasing trend (AAPC < 0, p < 0.05). Light blue bars represent the countries with a decreasing trend that is not statistically significant (AAPC < 0, p ≥ 0.05). AAPC: average annual percent change (%).

In sensitive analysis, we observed linear correlations between the lifetime risks and the 0–74 years cumulative risks of developing and dying from haematologic malignancies. The values of two indicators were close in countries with low life expectancy. However, the lifetime risks were significantly higher than 0–74 years cumulative risks in countries with high life expectancy (Supplementary Fig. S44).

Discussion

In this study, we performed global, regional, and national estimation of lifetime risks of haematologic malignancies using GLOBOCAN 2022 data. We found that the global lifetime risk of developing and dying from all haematologic malignancies was 1.67% and 0.98%. The lifetime risks were higher in males than in females in most regions. The lifetime risks increased with HDI levels. In most of the countries, NHL was the haematologic malignancy that most likely to occur, but leukaemia was the haematologic malignancy that most likely to cause death. In most countries that can provide consecutive cancer surveillance data, both the LRI and LRM exhibited increasing trends.

Haematologic malignancies are common cancers worldwide. However, compared with other cancer types, the reports on the global epidemiological characteristics of haematologic malignancies were limited in number and scope. In terms of specific cancer types, the incidence and mortality rates of NHL were stable in most populations in recent years.2 The incidence rates of NHL increased with HDI level, which was similar with the distribution of lifetime risks of developing NHL. However, the mortality rates were highest in regions with low HDI, such as Northern Africa, Melanesia and Eastern Africa, but were relatively lower in regions with high HDI, such as Australia and New Zealand, Western Europe and Northern America.12,13 This finding was inconsistent with the regional distribution of lifetime risks of dying from NHL, which was found positively associated with HDI. The disparity arose because the calculation of LRM factored in both the cancer-specific mortality rate and life expectancy, thereby neutralizing the relatively minor variations in mortality rates across countries through the consideration of differences in life expectancy. It indicated that although the mortality rates of NHL in Australia/New Zealand, Europe and Northern America were slightly lower, since the life expectancy of these regions were high, the lifetime risks of dying from NHL on population level in these regions were still higher compared to regions in Africa. This interpretation was probably closer to the reality and can shed new light on disease prevention and control strategy development, especially in countries with competing public health priorities. From this perspective, we believed that in contrast to traditional incidence and mortality indicators, the composite lifetime risk indicators (LRI and LRM) offer a more rational explanation for epidemiological disparities between regions and possess a clearer significance in public health. The correlations between the lifetime risks of developing and dying from haematologic malignancies and HDI were displayed in Supplementary Fig. S45.

The incidence and mortality rates of HL were relatively low when compared to other haematologic malignancies, however, there were significant variations among different populations. Globally, there was a nearly tenfold variation in the geographical distribution of HL incidence, with the highest rates observed in countries of high HDI and the lowest in countries of low HDI. The geographical distribution of HL mortality followed an inverse pattern with less variation.3,12,14 We used the indicator LRI/LRM ratio to describe the variations in the geographical distribution of HL risks and also found a five-fold difference between regions of high and low HDI. LRI/LRM ratio can serve as an indicator to reflect the level of treatment and survival rates of a disease within a specific population. The longer the survival is, the higher the LRI/LRM ratio can be. Therefore, we suggest that the LRI/LRM ratio could serve as a proxy for comparing disease survival rates in the absence of population-based survival data. HL is among the first systemic neoplasms proved to be curable with combination of chemotherapy, radiotherapy and multimodality treatment, even in advanced stages of the disease.15 The 5-year survival rate rises to 90% or higher in patients who have access to most advanced treatment regimens.16,17 Precisely due to this, the significant and widening survival disparity of HL between higher-developed and lower-developed countries highlights the alarming inequality in the distribution of medical resources, both in quantity and quality, across the globe.18

Leukaemia ranked as the 13th most common cancer and the 10th leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally.1 Our analysis revealed that leukaemia was the haematologic malignancy with the highest likelihood of causing death worldwide. The incidence, mortality, survival rates and age-at-onset patterns of leukaemia vary significantly across its subtypes, specifically acute lymphoid leukaemia (ALL), chronic lymphoid leukaemia (CLL), acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML).19 The diverse nature of leukaemia subtypes leads to significant disparities in clinical diagnosis and treatment approaches.20,21 ALL and AML account for the majority of leukaemia-related deaths. However, CLL and CML have become less fatal due to the advancement of effective treatments in recent decades.22,23 Consequently, the international variations in lifetime risks of leukaemia could potentially be influenced by the distribution of these subtypes. However, due to the inherent limitations of the currently available global mortality data categorized by leukaemia subtype, we are unable to estimate the lifetime risk of developing or dying from various subtypes of leukaemia in this study. This highlights the need for further research and international cooperation to uncover the nuanced epidemiological differences among leukaemia subtypes.

The global epidemiological profile of multiple myeloma (MM) and its temporal trends were examined, revealing an upward incidence trend among males and a downward mortality trend among females.24 We found that MM was the haematologic malignancy that most likely to develop or to die from in islands around Caribbean Sea, which was seldomly seen in other regions. What’s more, we found that MM was with higher risks in females than males in some regions, which was in line with the previous epidemiologic evidences. SEER data showed that the incidence of MM was twice as high in blacks as in general population.25 East and West Africa and the Caribbean immigrants had higher mortality rates of MM compared to native England and Wales.26 These evidences indicated that the ethnicity and genetic background may account for the unique geographic distribution of lifetime risks of MM. However, because of the relatively low incidence, MM was not considered important enough to be prioritized in Central America and the Caribbean. To guarantee the timely delivery of effective treatment for patients with MM, professionals called on more evidences that gave the problem greater visibility to influence local decision-making in Central America and the Caribbean.27 This pressing concern was prominently highlighted in the present study.

Previous study has reported a rising incidence trend alongside a decreasing mortality trend in haematologic malignancies over the past three decades, with Hodgkin lymphoma exhibiting the most significant reduction in mortality rates.4 In contrast to previous findings, our study revealed an increasing lifetime risk of developing and dying from haematologic malignancies in the majority of the studied countries. Several potential explanations for these conflicting observations can be considered: (1) The calculation of lifetime risks incorporates life expectancy, which has seen a significant increase in recent years. Consequently, even if the mortality rates remain stable or declined slightly, the lifetime risks tend to rise. (2) The 30 countries included in our analysis, which possess consecutive cancer surveillance data, are predominantly high HDI countries with advanced diagnostic and treatment technologies. Therefore, our findings reflect the trends observed in these selected countries but may not be representative of global trends. Upon analyzing the data by cancer type, we discovered that the lifetime risk of dying from Hodgkin lymphoma in a significantly larger number of countries was statistically insignificant when compared to other cancer types. This finding aligned with previous studies and was reasonable, considering the current advancements in clinical care.

The unique feature of current study is that we have offered a comprehensive analysis of the lifetime risk of haematologic malignancies according to the most recent global population-based cancer registration statistics. There are also several limitations. First, the accuracy and comparability of lifetime risk estimation of haematologic malignancies depend largely on the quality and quantity of available cancer registry data and vital statistics around the world. However, the coverage and quality of cancer registry system varied across countries and some areas still lacked data of high quality, such as South America and Africa.28 What’s more, since the diagnosis and treatment of haematologic malignancies were complicated, the geographic distribution of lifetime risks and their positive associations with HDI we observed in this study might be partly due to the inter-country differences in diagnostic capacity and accessibility to haematologic medical specialties, medicines, new technologies and equipment. Thus, underdiagnosis and underreporting can be sources of bias in the estimation of lifetime risk of haematologic malignancies, and the interregional comparison results should be interpreted with caution. Okello et al.29 argued that in sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 26 million people living with HIV were at high risk of haematologic malignancies. However, the underestimation of the incidence and mortality of haematologic malignancies might result in the neglect of the public health hazard caused by these diseases, especially among vulnerable population. This in turn emphasized the crucial role of high-quality cancer registry data in promoting regional cancer prevention and control efforts. Thirdly, it is unfortunate that our current study does not provide a lifetime analysis by leukaemia subtype, which could have offered significant insights. To uncover more nuanced scientific evidence that can contribute to the global prevention and control of leukaemia, further research endeavours and collaborative efforts are imperative.

In conclusion, we discussed the global, regional, and national landscape, along with the changing trends in lifetime risks of developing and dying from different haematologic malignancies on a global scale. We interpreted the lifetime risks and the indicators derived from them and proposed that these indicators were of great significance and can be used to reveal the public health issues that require priority attention.

Contributors

RZ and WW conceived the study. KS, RZ and HW designed the protocol. KS, QZ and RZ analysed the data. KS, QZ, KG, HW and SW contributed to the statistical analysis and interpretation of data. KS drafted the manuscript, and other authors critically revised the manuscript. RZ and WW accessed and verified the underlying data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Aggregated cancer incidence and mortality data used for the analyses are publicly available online at https://gco.iarc.fr/today/. The population, all-cause mortality and life expectancy data are publicly available at https://population.un.org/wpp/. Other request for full dataset is available from the corresponding author at Rong-shou Zheng, zhengrongshou@cicams.ac.cn and Wen-Qiang Wei, weiwq@cicams.ac.cn.

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by CAMS Innovation Funds for Medical Sciences (No. 2021-I2M-1-061, No. 2021-I2M-1-011). The funders of this study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103193.

Contributor Information

Rongshou Zheng, Email: zhengrongshou@cicams.ac.cn.

Wenqiang Wei, Email: weiwq@cicams.ac.cn.

Appendix ASupplementary data

References

- 1.Bray F., Laversanne M., Sung H., et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miranda-Filho A., Piñeros M., Znaor A., Marcos-Gragera R., Steliarova-Foucher E., Bray F. Global patterns and trends in the incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(5):489–499. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh D., Vaccarella S., Gini A., De Paula Silva N., Steliarova-Foucher E., Bray F. Global patterns of Hodgkin lymphoma incidence and mortality in 2020 and a prediction of the future burden in 2040. Int J Cancer. 2022;150(12):1941–1947. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang N., Wu J., Wang Q., et al. Global burden of hematologic malignancies and evolution patterns over the past 30 years. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):82. doi: 10.1038/s41408-023-00853-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng R., Wang S., Zhang S., et al. Global, regional, and national lifetime probabilities of developing cancer in 2020. Sci Bull (Beijing) 2023;68(21):2620–2628. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2023.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day N.E. Cancer incidence in five Continents. Cumulative rate and cumulative risk. IARC Sci Publ. 1992;120:862–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasieni P.D., Shelton J., Ormiston-Smith N., Thomson C.S., Silcocks P.B. What is the lifetime risk of developing cancer?: the effect of adjusting for multiple primaries. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(3):460–465. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad A.S., Ormiston-Smith N., Sasieni P.D. Trends in the lifetime risk of developing cancer in Great Britain: comparison of risk for those born from 1930 to 1960. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(5):943–947. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations . 2019. World population prospects.https://population.un.org/wpp/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations . 2020. Human development index (HDI)http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Agency for Research on Cancer Cancer today. https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/en

- 13.Mafra A., Laversanne M., Gospodarowicz M., et al. Global patterns of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2020. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(9):1474–1481. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J., Pang W.S., Lok V., et al. Incidence, mortality, risk factors, and trends for Hodgkin lymphoma: a global data analysis. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01281-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansell S.M. Hodgkin lymphoma: a 2020 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(8):978–989. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanbhag S., Ambinder R.F. Hodgkin lymphoma: a review and update on recent progress. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(2):116–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connors J.M., Cozen W., Steidl C., et al. Hodgkin lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):61. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leak S.A., Mmbaga L.G., Mkwizu E.W., Mapendo P.J., Henke O. Hematological malignancies in East Africa-Which cancers to expect and how to provide services. PLoS One. 2020;15(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daltveit D.S., Morgan E., Colombet M., et al. Global patterns of leukemia by subtype, age, and sex in 185 countries in 2022. Leukemia. 2025;39(2):412–419. doi: 10.1038/s41375-024-02452-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamb M., Painter D., Howell D., et al. Lymphoid blood cancers, incidence and survival 2005-2023: a report from the UK’s Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Cancer Epidemiol. 2024;88 doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2023.102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiNardo C.D., Erba H.P., Freeman S.D., Wei A.H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2023;401(10393):2073–2086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantarjian H., Paul S., Thakkar J., Jabbour E. The influence of drug prices, new availability of inexpensive generic imatinib, new approvals, and post-marketing research on the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia in the USA. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(11):e854–e861. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kantarjian H.M., Welch M.A., Jabbour E. Revisiting six established practices in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(10):e860–e864. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang J., Chan S.C., Lok V., et al. The epidemiological landscape of multiple myeloma: a global cancer registry estimate of disease burden, risk factors, and temporal trends. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(9):e670–e677. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00165-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banavali A., Neculiseanu E., Draksharam P.L., et al. Findings of multiple myeloma in afro-caribbean patients in the United States. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–6. doi: 10.1200/JGO.17.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grulich A.E., Swerdlow A.J., Head J., Marmot M.G. Cancer mortality in african and caribbean migrants to England and wales. Br J Cancer. 1992;66(5):905–911. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pimentel M., Espinal O., Godinez F., et al. Consensus statement: importance of timely access to multiple myeloma diagnosis and treatment in Central America and the caribbean. J Hematol. 2022;11(1):1–7. doi: 10.14740/jh971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang S., Zheng R., Li J., et al. Global, regional, and national lifetime risks of developing and dying from gastrointestinal cancers in 185 countries: a population-based systematic analysis of GLOBOCAN. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9(3):229–237. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00366-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okello C.D., Niyonzima N., Ferraresso M., et al. Haematological malignancies in sub-Saharan Africa: east Africa as an example for improving care. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(10):e756–e769. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.