Abstract

Introduction

Postnatal management of ovarian cysts in neonates is debated.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of neonates diagnosed with ovarian mass at a tertiary referral center (Jan 2014–May 2024).

Results

64 neonates (1 day–8 months; mean: 8.2 weeks) were diagnosed with 65 ovarian masses ≥ 20 mm (mean: 44.2 mm; range: 20–81 mm). Prematurity was present in 31% (n = 20). Primary surgery was performed in 11 cases due to severe symptoms/uncertain mass origin; 3 underwent percutaneous puncture; 50 were observed. Of these, 37/50 (74%) had cyst regression within 18 months, including 7 complex cysts (19%). Delayed involution occurred in 6/50 (12%) observed. Both complex morphology and larger cyst size were significantly associated with delayed regression (p = 0.0005, p = 0.0045, respectively). 8/50 (16%) underwent intervention for cyst enlargement (2 laparoscopies, 5 punctures) or concern for interval torsion (1 laparotomy). No confirmed postnatal torsion or hemorrhagic complications occurred in the observation group. One patient required a repeat procedure after percutaneous reduction. No significant association was found between lesion size and the symptoms of recent adnexal torsion (p = 0.99).

Conclusions

Observation is safe for asymptomatic ovarian cysts. Postnatal torsion is rare but can occur regardless of lesion size, including patients with no prior history of ovarian cysts.

Keywords: Fetal ovarian cyst, Neonatal ovarian cyst, Ovarian cyst puncture

Introduction

Ovarian cysts, both in the fetal period and in infancy, are usually of follicular origin.

It is suggested that the cyst formation is caused by increased concentrations of fetal and placental hormones—pituitary gonadotropins (FSH and LH), placental HCG, and estrogen [1–3]. Another theory assumes the immaturity of the pulse generator located in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. As neonates develop, the hypothalamus and pituitary glands become increasingly sensitive to negative feedback from low sex steroid levels, explaining both the delayed involution of cysts and the occurrence of ovarian cysts in premature neonates [2–4]. Spontaneous resolution of the cysts usually occurs within 10–14 months [3, 5].

Despite the benign nature of the lesion, the presence of a large cyst can lead to complications, with adnexal torsion and subsequent ovarian loss being among the most severe. Rarely reported complications arise from mass effects or hemorrhage. Following Nussbaum et al. [6], neonatal cysts are commonly classified based on sonographic parameters into two categories: “simple” cysts, which are unilocular, well-demarcated lesions with anechoic contents and thin walls, and “complex” cysts, characterized by hyperechoic or inhomogeneous contents, often accompanied by fluid levels, septa, or calcifications. Reports indicate a significantly higher risk of complications for large, complex cysts with a 40 or 50 mm cut-off point [1, 7]. However, most analyses focus on prenatal ultrasound imaging and postnatal outcome, thus providing no insight into the effectiveness of postnatal intervention. Surgical intervention is clearly indicated for symptomatic patients, but its necessity for asymptomatic newborns is debated. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided cyst puncture offers a minimally invasive alternative [5]; however, due to the limited number of studies on this technique, the complication rate remains unknown.

We present an analysis of treatment outcomes for ovarian masses in the first year of life. The center uses a strategy of observation in asymptomatic patients with ovarian cysts, regardless of lesion size or its sonographic features. Patients are monitored through regular outpatient ultrasounds. Given the limited utility of ovarian tumor markers in this age group, the center's protocol includes measuring only alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) to confirm its expected decline in two consecutive assays, thereby helping to rule out immature teratoma. Parents are counseled on the need for urgent hospitalization if alarming symptoms arise. In symptomatic patients, prompt surgical intervention is undertaken, with laparoscopy and ovarian-sparing techniques as the preferred approach. Oophorectomy is avoided, even in the presence of necrosis, and is considered only when there is complete disintegration or autoamputation of the gonad.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patient records for those consulted at the surgical outpatient clinic or hospitalized in the pediatric surgery unit between January 2014 and May 2024 due to lesions originating from the ovary. Medical records were reviewed to collect data on patients'age, prenatal history, detected perinatal anomalies, results of ante- and postnatal imaging, symptoms, surgical procedures, and intraoperative findings, including adnexal torsion, intra- and postoperative complications, recurrences, and synchronous diseases. Outpatient clinic records were analyzed for additional tests and follow-up ultrasonography results. Only patients who attended at least one follow-up visit confirming regression or completion of treatment were included in the study. Patients were divided into groups based on the size of the ovarian lesion into three categories—lesions smaller than 20 mm, with lesions 20–40 mm in size, and lesions larger than 40 mm. Since the presence of small follicular cysts is not considered pathology, patients with lesions smaller than 20 mm were excluded from the study. The remaining two groups were compared regarding the frequency of symptoms, comorbid conditions, applied therapeutic approaches, and treatment outcomes. Ovarian cysts were categorized as simple or complex based on sonographic features. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact or chi-square test, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test due to non-normal distribution. A Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the relationship between cyst size and time to regression. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was conducted with approval from the Jagiellonian University Institutional Review Board (#118.6120.52.2023).

Results

Between January 2014 and May 2024, 104 infants under one year of age were treated at a tertiary referral center for lesions of ovarian origin. Of these, 64 patients presented with 65 lesions measuring ≥ 20 mm and had available follow-up data. The remaining 40 patients were excluded from the study. Thirty-five girls were observed in the hospital outpatient clinic, and 29 were hospitalized.

Age at admission ranged from 1 day to 8 months (mean 8.2 weeks). Most of them were diagnosed at prenatal age (n = 43; 67%), 17 (26.5%) in the first month of life, and 4 (6%) later in infancy. A significant part of the group consisted of premature babies (n = 20; 31%), with an average age of birth of 30 weeks of gestation (range 25–36). Cyst sizes ranged from 20 to 76 mm, with a mean diameter of 42.3 mm.

In all children, the diagnosis was made based on an ultrasound examination. In 6 girls, diagnostics were extended to include cross-sectional imaging (pelvic MRI in 3, CT in 3) due to the unknown origin of the mass (suspected gastrointestinal duplication, mesenteric lymphatic malformation, hydrocolpos). Nine patients presented cystic changes in both ovaries; however, cysts exceeding 20 mm in diameter bilaterally were observed in only one patient. The average initial size of the lesion was 44.2 mm (range 20 to 81 mm). Thirty-two patients had a lesion smaller or equal to 40 mm (Group I), and in 33 cases, the lesion exceeded this size (Group II). Complex cyst morphology was significantly more frequent in Group II (62%) compared to Group I (29%) (p = 0.0166) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of patients based on cyst size (Group I: cysts 20–40 mm; Group II: cyst > 40 mm)

| Group I | Group II | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sonographic image | |||

| Simple | 22 | 13 | |

| Complex | 9 | 21 | 0.0166 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Sugestive for ovarian torsion | 4 | 3 | |

| Mass effect | 0 | 1 | |

| Papable mass | 0 | 9 | |

| Hyperestrogenism | 1 | 1 | 0.0555 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Prematurity | 11 | 9 | |

| NEC* | 1 | 1 | 0.9999 |

| Final approach | |||

| Observative | 25 | 19 | |

| Percutaneous aspiration | 0 | 7 | |

| Laparoscopy | 5 | 4 | |

| Laparotomy | 1 | 4 | 0.0222 |

| Outcome | |||

| Spontaneous involution | 25 | 11 | |

| Delayed involution | 0 | 8 | 0.0014 |

| Ovarian loss/preservation | |||

| Loss | 2 | 14 | |

| Preservation | 29 | 20 | 0.0031 |

Parameters with p values less than 0.05, indicating statistical significance, are highlighted in bold

NEC, nectrotizing enterocolitis

Initially, most patients were asymptomatic (n = 42; 65.6%). Feeding intolerance and restlessness were observed in six (9.4%). Symptoms suggestive of a mass effect were suspected in four cases; however, in two premature infants (one with neonatal respiratory distress and one with constipation), the symptoms persisted despite intervention. Ultimately, the mass effect was confirmed as the cause of symptoms in one child, presenting as urinary retention in the pelvicalyceal system. In two cases, gastrointestinal obstruction resulted from necrotizing enterocolitis, which developed in infants born at 27 and 36 weeks of gestation. Two premature infants exhibited signs of hyperestrogenism, including vulvar edema and breast enlargement, which resolved spontaneously. In 9 children (14.1%), a compressible mass in the abdomen was palpable during physical examination. Notably, no child presented with clinical signs of intra-abdominal bleeding.

Although mass effect and palpable abdominal masses were observed exclusively in Group II, no statistically significant difference was found between Group I and Group II regarding the presence of symptoms suggestive of ovarian torsion (p = 0.9999). In 50 patients (mean size 52 mm), due to the lack of severe symptoms, initially conservative treatment was used—the infants were discharged from the hospital, with a plan of abdominal ultrasound examination every 6–9 weeks in the outpatient clinic. In this group, none of the cysts showed ultrasound features suggestive of an ovarian tumor, such as calcifications, solid components, or abnormal vascularization. The remaining 14 patients underwent surgical intervention. Three underwent ultrasound-guided puncture through the abdominal wall. Laparoscopy was performed in seven cases, while laparotomy was the preferred approach in four. Ovarian-sparing surgery was possible in seven patients (including five with ovarian torsion), while autoamputation or chronic torsion with ovarian disintegration was found in four girls [Fig. 1]. No perioperative or postoperative complications were observed in the patients who underwent surgery. In one patient, during percutaneous puncture, the leakage of contents into the abdominal cavity was observed. However, this did not entail any clinical consequences. Additionally, one child required reintervention following percutaneous decompression due to the regrowth of a mass, necessitating a repeat procedure.

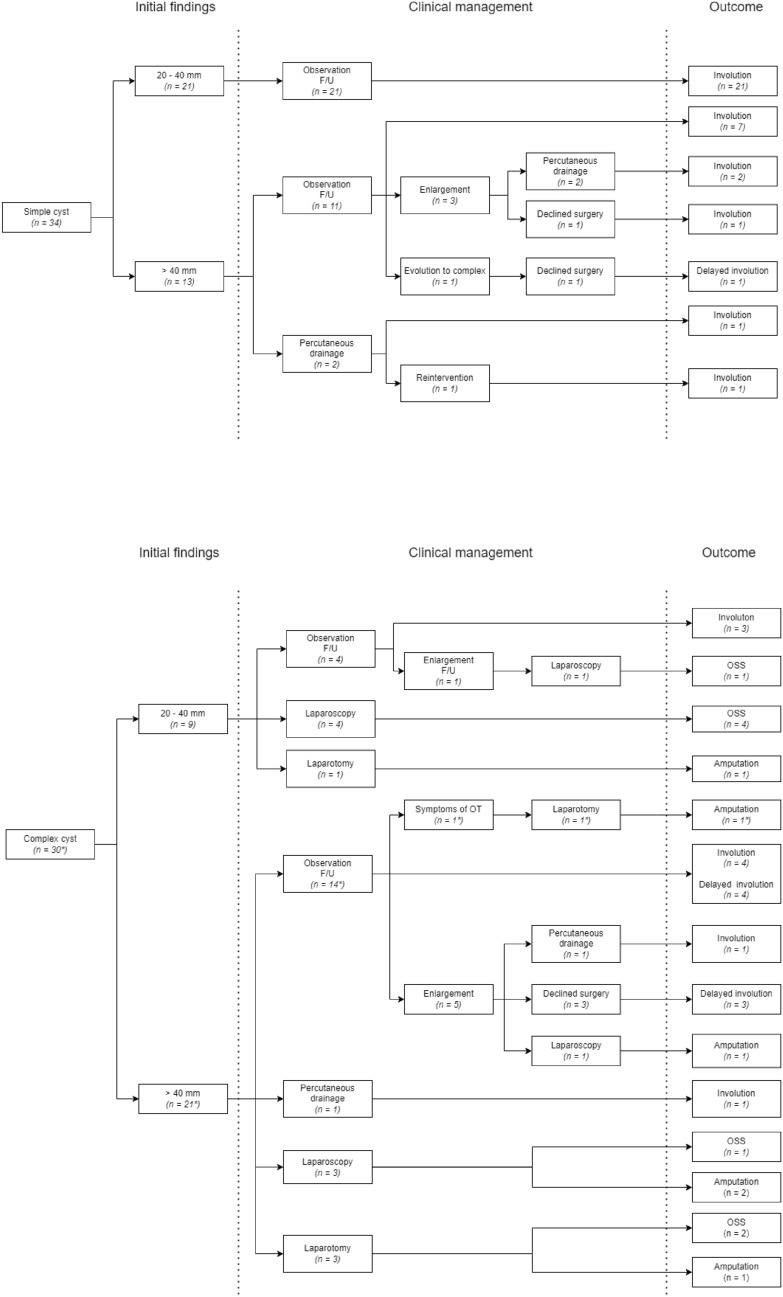

Fig. 1.

Management and outcome of infants with ovarian cyst (n = 64) in our retrospective study. The cohort was classified into two groups based on sonographic findings: simple cysts (n = 34) and complex cysts (n = 30). The patient with a bilateral cyst was categorized according to the larger lesion and is marked with an asterisk.

Histological examination of all surgical specimens confirmed functional lesions, whereas cytology of each sample obtained during percutaneous puncture revealed protein content and single plasma cells.

Follow-up

Among the 50 patients managed conservatively, cyst resolution occurred within 18 months in 37 (74%) cases, including 7 complex cysts (19%). In six girls, all of whom had large, complex cysts, resorption was delayed, occurring only after the second year of life (range: 24–51 months, mean: 35.5 months).

Cyst enlargement was observed in nine patients (all with cysts exceeding 40 mm). Six of them were admitted to the ward and underwent surgical intervention (four percutaneous punctures and two laparoscopies). In the remaining cases, no intervention was performed due to a lack of parental consent.

In one patient with bilateral cysts (a complex cyst measuring 49 mm and a simple cyst measuring 22 mm), ovarian torsion was suspected due to symptoms of irritability and feeding intolerance. Emergency laparotomy confirmed chronic torsion with ovarian autoamputation, while the simple cyst was separated from a healthy ovary.

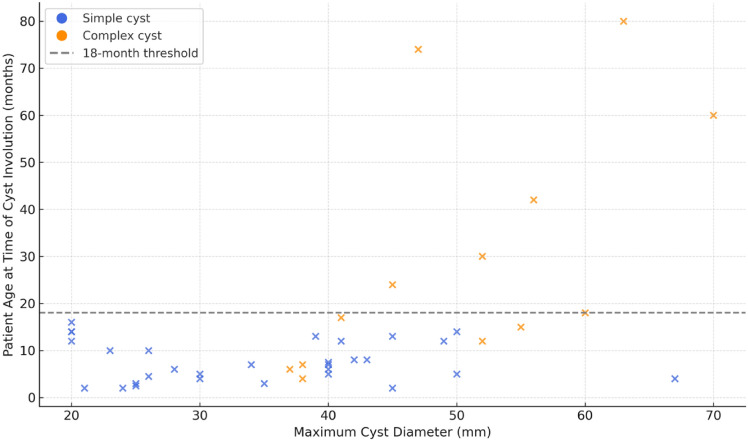

Time to spontaneous involution was significantly longer in infants with complex cysts (mean: 29.9 months; range: 4–80 months) compared to those with simple cysts (mean: 7.6 months; range: 2–16 months). The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0005, Mann–Whitney U test), with complex cysts showing greater variability in regression time. A moderate positive correlation was observed between the maximum cyst diameter and age at regression (Spearman's R = 0.43, p = 0.0045) [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2.

Correlation between the largest cyst diameter at diagnosis and the age at cyst involution in patients managed conservatively

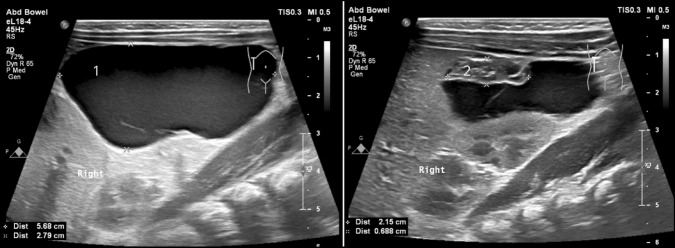

Sonographic evaluation confirmed the absence of pathology and the presence of two healthy ovaries in 34 patients. In nine cases (all but one with an initial cyst size exceeding 40 mm), only a single ovary was visualized following cyst involution [Fig. 3]. Among preterm infants diagnosed postnatally (mean gestational age at birth 27.2 weeks), all simple cysts resolved spontaneously, regardless of size (mean diameter: 37 mm; range: 26–50 mm). All patients showed the expected decrease in AFP levels on follow-up testing.

Fig. 3.

A large ovarian cyst with gonadal autoamputation visualized on initial ultrasound examination. The cyst content was drained percutaneously, and the cyst with the gonad underwent involution within 18 months. 1—Large abdominal cyst. 2—Amputated ovary at the upper pole of the lesion

Discussion

Ovarian cysts in infants are usually of follicular origin. In a group of our patients, all cysts were functional, and none of the lesions turned out to be neoplastic tumors. The possibility of ovarian malignancy is extremely remote in children under the age of 2 years [8, 9]. Despite the benign nature of the lesion, its management remains unclear for both gynecologists overseeing fetal care and pediatric surgeons performing postnatal interventions.

It is suggested that the majority of neonatal torsion occurs antenatally [10, 11]. In a review by Brandt et al., 92% of neonatal ovaries with torsion showed signs of torsion on the first postnatal ultrasound, indicating that most of these events likely occur in utero [2]. Evidence suggesting an increased risk of ovarian torsion primarily originates from studies describing ovarian size and morphology on prenatal ultrasonography and postnatal surgery findings. Critical analysis of these studies highlights difficulties in determining whether the reported cases represent antenatal or postnatal torsion.

The latest European Paediatric Surgeons'Association Consensus Statement on the Management of Neonatal Ovarian Simple Cysts suggests that neonates with simple ovarian cysts larger than 4 cm should be offered surgical intervention within the first two weeks of life, with complete laparoscopic cyst aspiration and fenestration using bipolar instruments as the preferred approach [12]. Our analysis, along with findings from other reported cohorts of neonates under clinical observation, suggest that postnatal ovarian torsion is a rare occurrence and that expectant management of simple cysts is safe regardless of their size. It is important to recognize that ovarian torsion can present as acute abdominal symptoms in infants and should be considered in the differential diagnosis, even in the absence of a prior history of ovarian cysts.

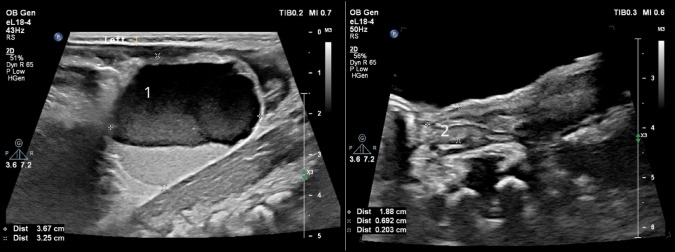

Complex cysts are often treated surgically soon after birth, and ovary removal rates often exceed 80% [1, 2, 7, 13, 14]. However, studies focusing on the observation of complex cysts, including our report, indicate that complex neonatal ovarian cysts tend to involute spontaneously [11, 14, 15]. Romiti et al. point out that the division of cysts into complex and simple ones is outdated. They suggest that implementing the expanded ultrasound terminology introduced by International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) may enhance the accuracy of predicting spontaneous cyst involution. According to their findings, cysts with low-level internal content (previously classified as complex) frequently resolved spontaneously [Fig. 4]. Conversely, cysts exhibiting ground-glass, hemorrhagic, mixed, or undefined content were commonly associated with necrosis on histopathological examination following surgical intervention [15].

Fig. 4.

Complex cyst of the left ovary that completely involuted within 4 months. 1—cyst with visible fluid level; 2—left ovary visualized during follow up

Due to advances in sonographic imaging technology, it is now possible to obtain greater detail and assess ovarian blood flow with high precision. In our group, three patients with cysts classified under the recognized nomenclature as complex underwent percutaneous drainage. In one case, single inclusions and septations within the lumen were attributed to a prior in-utero puncture. In the remaining two cases, daughter cysts—considered pathognomonic for congenital ovarian cysts [16, 17]- were observed within the lumen. Complete resolution was achieved in all patients following the drainage procedure. This procedure is not recommended for cysts with suspected intraluminal hemorrhage, solid components, or when there is any uncertainty regarding the origin of the cyst. However, this underscores the necessity of an individualized, patient-specific approach.

The population of neonates with ovarian cysts differs in terms of perinatal history, including interventional procedures and suspected intrauterine torsion, intrapartum events and complications, gestational age at birth, or birth weight.

In our cohort, premature infants accounted for 31% of the cases. The immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal axis is associated with prolonged mini puberty and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in preterm babies [18, 19]. In an extremely premature newborn, it is important to recognize the 40 mm size threshold as artificial since even smaller lesions may constitute a significant part of the pelvic and abdominal volume. In this specific group, due to the high risk of life-threatening complications of prematurity, we are also inclined to minimize interventions. The limited data suggest spontaneous disappearance and absence of observed severe complications in this group [20].

In symptomatic children suspected of having ovarian torsion, surgical treatment should be initiated immediately. Detorsion and ovarian-sparing surgery are strongly recommended, as partial regeneration of the ovarian cortex remains possible even in the presence of necrosis. The intraoperative assessment of vascularization using indocyanine green is gaining popularity [21]. However, since the only chance to save ovarian parenchyma lies in its simple detorsion and ovarian-sparing surgery, it is worth questioning whether the use of indocyanine green in this context is meaningful. Avoiding oophorectomy, even in the presence of visible necrosis, does not lead to complications but instead provides an opportunity to preserve the ovarian cortex. Despite the surgeon's impression that the necrotic changes were complete, histological examination often reveals the presence of viable ovarian tissue [2, 5, 11, 14].

This underscores the conclusion that the ovary should be retained in all cases where complete disintegration or autoamputation has not occurred. Removal of a viable ovary should not be considered a therapeutic option in the case of difficulties in separating the ovary from the cyst.

Study limitations

We are aware of the multiple limitations of our study. First, its retrospective design makes it prone to selection bias, as we could only include cases documented in medical records. Some data were inconsistently recorded, which could affect the accuracy of our analysis. Imaging and surgical documentation varied, making it challenging to apply a uniform classification of cysts. The small sample size and heterogeneity within the group, particularly in the subgroup of premature infants, limits the usability of the data.

Conclusions

Given the high spontaneous resorption rate, and lack of symptoms, early neonatal surgery should be considered carefully with the guardians. Proper qualification relies on prenatal imaging and collaboration between pediatric surgeons and obstetrician-gynecologists. Observation of asymptomatic cysts is generally safe, regardless of size. Suspected antenatal ovarian torsion doesn't require immediate intervention, as ovarian salvage in asymptomatic patients is unlikely. Postnatal torsion is rare but can occur regardless of lesion size, including patients with no prior history of ovarian cysts. Oophorectomy should be avoided to preserve any viable ovarian tissue.

Author contribution

OS and MF were responsible for data collection, preparation of tables and Fig. 1, and drafting the manuscript. AK assessed the radiological findings and prepared Figs. 2–4 AT-N and WG critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bucuri C, Mihu D, Malutan A, Oprea V, Berceanu C, Nati I, Rada M, Ormindean C, Blaga L, Ciortea R (2023) Fetal ovarian cyst-a scoping review of the data from the last 10 years. Medicina (Kaunas) 59(2):186. 10.3390/medicina59020186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt ML, Luks FI, Filiatrault D, Garel L, Desjardins JG, Youssef S (1991) Surgical indications in antenatally diagnosed ovarian cysts. J Pediatr Surg 26(3):276–282. 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90502-k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolgin SE (2000) Ovarian masses in the newborn. Semin Pediatr Surg 9(3):121–127. 10.1053/spsu.2000.7567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Słodki M, Respondek-Liberska M (2007) Torbiel jajnika u płodu–przeglad 420 przypadków z piśmiennictwa z lat 1984–2005 [Fetal ovarian cysts–420 cases from literature–metaanalysis 1984–2005]. Ginekol Pol 78(4):324–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler A, Nagar H, Graif M, Ben-Sira L, Miller E, Fisher D, Hadas-Halperin I (2006) Percutaneous drainage as the treatment of choice for neonatal ovarian cysts. Pediatr Radiol 36(9):954–958. 10.1007/s00247-006-0240-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nussbaum AR, Sanders RC, Hartman DS, Dudgeon DL, Parmley TH (1988) Neonatal ovarian cysts: sonographic-pathologic correlation. Radiology 168(3):817–821. 10.1148/radiology.168.3.3043551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bascietto F, Liberati M, Marrone L, Khalil A, Pagani G, Gustapane S, Leombroni M, Buca D, Flacco ME, Rizzo G, Acharya G, Manzoli L, D’Antonio F (2017) Outcome of fetal ovarian cysts diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound examination: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 50(1):20–31. 10.1002/uog.16002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strickland JL (2002) Ovarian cysts in neonates, children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 14(5):459–465. 10.1097/00001703-200210000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Łuczak J, Bagłaj M, Dryjański P, Kalcowska A, Banaszyk-Pucała N, Boczar M, Dymek K, Fryczek M, Giżewska-Kacprzak K, Górecki W, Grabowski A, Gregor A, Jabłońska M, Kowalewski G, Lewandowska M, Małowiecka M, Ogorzałek A, Pękalska M, Piotrowska-Gall A, Porębski M, Siewiński M, Patkowski D (2022) What should be the topics of a prospective study on ovarian masses in children?-results of a multicenter retrospective study and a scoping literature review. Curr Oncol 29(3):1488–1500. 10.3390/curroncol29030125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagolan P, Giorlandino C, Nahom A, Bilancioni E, Trucchi A, Gatti C, Aleandri V, Spina V (2002) The management of fetal ovarian cysts. J Pediatr Surg 37(1):25–30. 10.1053/jpsu.2002.29421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papic JC, Billmire DF, Rescorla FJ, Finnell SM, Leys CM (2014) Management of neonatal ovarian cysts and its effect on ovarian preservation. J Pediatr Surg 49(6):990–994. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxena AK, Mutanen A, Gorter R, Conforti A, Bagolan P, De Coppi P, Soyer T, Association EPS (2024) European paediatric surgeons’ association consensus statement on the management of neonatal ovarian simple cysts. Eur J Pediatr 34(3):215–221. 10.1055/s-0043-1771211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozcan HN, Balci S, Ekinci S, Gunes A, Oguz B, Ciftci AO, Haliloglu M (2015) Imaging findings of fetal-neonatal ovarian cysts complicated with ovarian torsion and autoamputation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 205(1):185–189. 10.2214/AJR.14.13426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enríquez G, Durán C, Torán N, Piqueras J, Gratacós E, Aso C, Lloret J, Castellote A, Lucaya J (2005) Conservative versus surgical treatment for complex neonatal ovarian cysts: outcomes study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185(2):501–508. 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romiti A, Moro F, Ricci L, Codeca C, Pozzati F, Viggiano M, Vicario R, Fabietti I, Scambia G, Bagolan P, Testa AC, Caforio L (2023) Using IOTA terminology to evaluate fetal ovarian cysts: analysis of 51 cysts over 10-year period. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 61(3):408–414. 10.1002/uog.26061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randazzo WT, Franco A, Hoossainy S, Lewis KN (2012) Daughter cyst sign. J Radiol Case Rep 6(11):43–47. 10.3941/jrcr.v6i11.1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quarello E, Gorincour G, Merrot T, Boubli L, D’Ercole C (2003) The “daughter cyst sign”: a sonographic clue to the diagnosis of fetal ovarian cyst. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 22(4):433–434. 10.1002/uog.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanciotti L, Cofini M, Leonardi A, Penta L, Esposito S (2018) Up-to-date review about minipuberty and overview on hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis activation in fetal and neonatal life. Front Endocrinol 9:410. 10.3389/fendo.2018.00410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuiri-Hänninen T, Kallio S, Seuri R, Tyrväinen E, Liakka A, Tapanainen J, Sankilampi U, Dunkel L (2011) Postnatal developmental changes in the pituitary-ovarian axis in preterm and term infant girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(11):3432–3439. 10.1210/jc.2011-1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starzyk J, Wójcik M, Wojtyś J, Tomasik P, Mitkowska Z, Pietrzyk JJ (2009) Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in newborns—a case presentation and literature review. Horm Res 71(1):60–64. 10.1159/000173743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciro E, Vincenzo C, Mariapina C, Fulvia DC, Vincenzo B, Giorgia E, Roberto C, Lepore B, Castagnetti M, Califano G, Escolino M (2022) Review of a 25-year experience in the management of ovarian masses in neonates, children and adolescents: from laparoscopy to robotics and indocyanine green fluorescence technology. Children (Basel, Switzerland) 9(8):1219. 10.3390/children9081219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.