Abstract

Non-viral DNA donor templates are commonly used for targeted genomic integration via homologous recombination (HR), with efficiency improved by CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Circular single-stranded DNA (cssDNA) has been used as a genome engineering catalyst (GATALYST) for efficient and safe gene knock-in. Here, we introduce enGager, an enhanced GATALYST associated genome editor system that increases transgene integration efficiency by tethering cssDNA donors to nuclear-localized Cas9 fused with single-stranded DNA binding peptide motifs. This approach further improves targeted integration and expression of reporter genes at multiple genomic loci in various cell types, showing up to 6-fold higher efficiency compared to unfused Cas9, especially for large transgenes in primary cells. Notably, enGager enables efficient integration of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) transgene in 33% of primary human T cells, enhancing anti-tumor functionality. This ‘tripartite editor with ssDNA optimized genome engineering (TESOGENASE) offers a safer, more efficient alternative to viral vectors for therapeutic gene modification.

Subject terms: Gene delivery, Gene therapy

Non-viral DNA donor templates are commonly used for targeted genomic integration via homologous recombination. Here the authors present the TESOGENASE system which enhances CRISPR-based gene integration by tethering circular single-stranded DNA to Cas9.

Introduction

The CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) is an effective and precise gene-editing enzyme that has revolutionized diverse fields of biotechnology, medical and agricultural research1–3. Cas9 proteins coupled to a guide RNA find and induce site-specific double-stranded breaks (DSB) into the genome for targeted gene deletion, repair or insertion in prokaryotes and eukaryotes1,4–6. Variants of CRISPR/Cas9 tailored and optimized for a variety of site-specific genome editing/modification uses have been developed1,7–9. However, targeted insertion of a new DNA sequence into the genome remains challenging10. Conventional targeted gene knock-in (KI) is achieved by homologous recombination (HR) which is extremely inefficient, especially for longer sequences11. Homology directed repair (HDR), is currently one of the most efficient ways to insert a DNA fragment ranging from a few bases to 2Kb, particularly when RNA-guided Cas9 introduced double-stranded breaks into the genome target12–14. But the efficiency of targeted insertion remains extremely low for >4 Kb large donor payloads14–16. Non-targeted gene insertion remains an option mostly achieved with viral vectors and transposon/transposase system.

Therapeutic uses of gene insertion will benefit from methods that integrate donor DNAs of any size in predictable genomic locations. Successful treatment requires a high percentage of cells accurately engineered to provide a positive effect on the patient while avoiding the safety issues and random integration that have occurred for many viral vectors12,17. Our prior studies showed that rearrangements and concatemerizations of the transgene prior to genomic insertion can be avoided by using circular single-stranded DNA (cssDNA) donors18. Non-viral cssDNAs also reduce the cGAS-mediated cell toxicities imparted by dsDNAs and avoid the sometimes-life-threatening reactions to viral vectors that have plagued therapeutic adoption of virus-based vectors. The cssDNAs have been proven to be competent for Cas9-mediated, gRNA site-directed integration into the genome18,19. An added advantage is that cssDNAs of up to 20 kb can be readily built in and purified using the recently described GATALYST vector that requires ~500 nt of vector sequence for replication in bacteria, compared to the >2 kb of vector sequence required for traditional phagemid vectors18.

As HDR mediated genome integration is a highly spatially and temporally regulated process in nucleoplasm, the strategy to enhance the KI efficiency using DNA donor is 1) to efficiently deliver donor DNA into the nucleus and 2) to tether donor DNA onto the targeted genomic locus, both of which are critical steps to increase the active local concentration of the donor template to ensure effective homologous searching and pairing to complete the HDR process. This idea has been verified by multiple studies using different strategies. For instance, dsDNA donors have been coupled to Cas9 endonuclease by fusing Cas9 together with DNA binding proteins including transcription factors, recombinase subunits (such as Rad51, Rad52, POLD3) and the dominant negative form of 53BP1 to improve the efficiency of dsDNA mediated knock-in20–28. Other studies coupled the single or double stranded donor DNA to Cas9 in vitro using chemical modifications, such as DNA biotinylation for tethering to an avidin-conjugated Cas9 or 5’-triethylene glycol (TEG) modification or covalent conjugation of donor DNA with Cas9 endonuclease29–33. Other tethering strategies involve the creation of a sgRNA/donor DNA hybrid34–37. Overall, most of the strategies focus on dsDNA as donor templates whereas the cssDNA has proven to be a more efficient and safer donor DNA for targeted gene KI across multiple cell types to many targeted loci in the mammalian genome18.

Here, we developed a set of enhanced GATALYST associated genome editors (enGager) by fusion of a nuclear localization single (NLS) peptide-tagged wild type Cas9 together with various single stranded DNA binding protein domains and peptides. These enGagers form a tripartite complex with sgRNA and cssDNA donors as an integrative site-specific, nucleus-targeted genome integration machinery. When applied for targeted genome integration with cssDNA donor templates to diverse genomic loci in various cell types, these enGagers outperform unfused canonical endonuclease editors by 1.5- to more than 6-fold. Cas9-cssDNA peptides and delivery methods optimized to achieve successful and functional, site-specific targeted integration in up to 33% of primary cells, dubbed the TesogenaseTM (tripartite editing with ssDNA optimized genome engineering nuclease) system, adding a set of endonucleases into the gene-editing toolbox for potential cell and gene therapy development based on ssDNA mediated non-viral genome engineering.

Results

Fusion of Cas9 with homologous recombination proteins enhance the efficiency of cssDNA mediated knock-in

We first evaluated the insertion of EGFP-coding sequence into the RAB11A genomic locus as our model for defining how much Cas9 modifications improve the efficiency of homology-directed, Cas9-dependent integration of a transgene (Fig. 1). A 2 kb cssDNA (css76) consists of a positive strand of 734 nucleotide long EGFP flanked by human genomic RAB11A sequences of 306 nt at the 5’ and 315 nt at the 3’, which can be targeted by a gRNA12. The donor cssDNA was co-electroporated into human K562 lymphoblast cells with an all-in-one (AIO) plasmid expressing both the Cas9 enzyme and the gRNA that directs Cas9 to the RAB11A genomic site. Flow cytometry defines the percentage of cells in which the otherwise unexpressed EGFP codons are accurately inserted into a gene and expressed under the control of the endogenous RAB11A promoter12. The Cas9 used was previously described to be targeted to the cell nucleus via fusion with two nuclear localization sequences (NLS)1.

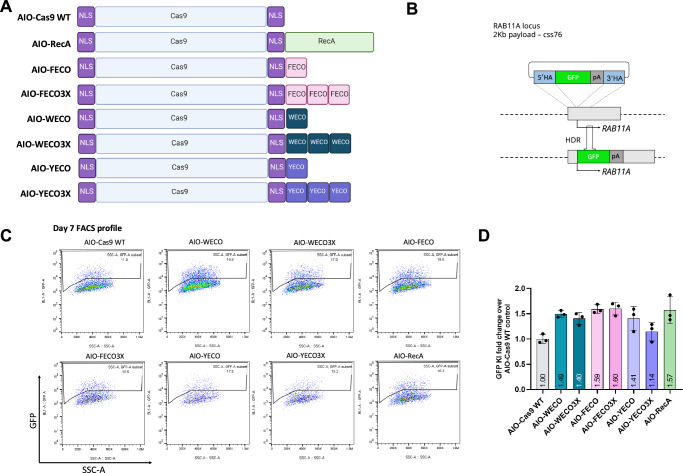

Fig. 1. Fusion of Cas9 and homologous recombination proteins enhance the ssDNA mediated knock-in.

A Schematic diagram of various Cas9-homologous recombination protein fusion constructs (enGagers) in all-in-one (AIO) plasmid format modified from Addgene plasmid #42230. Two nuclear localization signals were added to the N’ and C’-termini of the Cas9 protein. RecA is the bacteria homologous DNA repair protein and Rad51(AE)/Rad51(SEAD) are two mutant variants from eukaryotes. Brex is a 36 amino acid peptide reported to recruit Rad51 in mammalian cells. B Schematic diagram of Knock in strategy of a 2Kb (left) and 4Kb (right) cssDNA donor template for RAB11A locus. C Representative FACS profiles with gating strategy showing % of GFP transgene cassette Knock in on RAB11 locus at day 3 post electroporation for various enGagers listed in (A). D Quantification of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in fold change of various enGagers as compared to Cas9 WT at day 3 (left), 8 (middle) and 14 (right) post electroporation. E representative FACS profiles with gating strategy showing % of 4Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in on RAB11 locus at day 3 post electroporation for various enGagers listed in (A). F Quantification of 4Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in fold change of various enGagers as compared to Cas9 WT at day 3 (left), 7 (right) post electroporation. Note that Brex enGager does not enhance knock in efficiency. Rad51 mutants and RecA enGagers increase both small and large transgene cassette knock in by 1.57–3.04-fold. RecA enGager outperforms among the enGagers tested. Bars represent mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates.

The NLS-Cas9 and derivatives are shown schematically in Fig. 1A. The RAB11A genomic locus is shown in Fig. 1B. Figure 1C, D shows the percentage of green fluorescent cells detected by flow cytometry 3, 8 and 14 days after electroporating the cssDNA and Cas9/gRNA plasmid into human K562 cells. Integration of the cssDNA catalyzed by NLS-Cas9 was compared with that supported by NLS-Cas9 fused to the E. coli RecA or the homologous human Rad51 DNA repair proteins previously shown to enhance Cas9-mediated integration38–41 (Fig. 1); two mutant forms of Rad51 with enhanced recombigenic activity (AE and SEAD)25 were used following N-terminal fusion design by Rees et al. NLS-Cas9 was also fused to a 36 amino acid (AA) peptide “Brex”42 to recruit endogenous Rad51 recombinase to the NLS-Cas9 complex.

Since both RecA and Rad51 also are ssDNA binding proteins, whereas the Brex peptide is not, the higher percentage of green fluorescence observed upon transfection with NLS-Cas9-Rad51 and -RecA fusions (11.5–15.4%) compared to the NLS-Cas9-Brex fusion (4.9%) or to NLS-Cas9 (6.8%) provided a preliminary indication that Rad51/RecA fusion might improve the efficiency of recombination via their DNA binding properties; the hypothesis is that those DNA-binding proteins tether the cssDNA to the nuclear-localized NLS-Cas9 complex. Similar results were also obtained with a 4 kb cssDNA (css116) in which the GFP sequences and additional sequences were flanked by the same 5’ and 3’ RAB11A homology sequences surrounding the integration site (Fig. 1B, E, F). The larger DNA insertions were also enhanced by the possible tethering of the cssDNA donor to NLS-Cas9 via ssDNA binding modules.

Knock-in enhancement by RecA and Rad51 persisted over time at 7/8 days and 14 days post-electroporation (Fig. 1D, F) which is consistent with enduring expression following RecA/Rad51-enhanced integration. In general, enhancement by any of RecA or Rad51 averaged around 2-fold above that attained with unfused NLS-Cas9 across all studies/days.

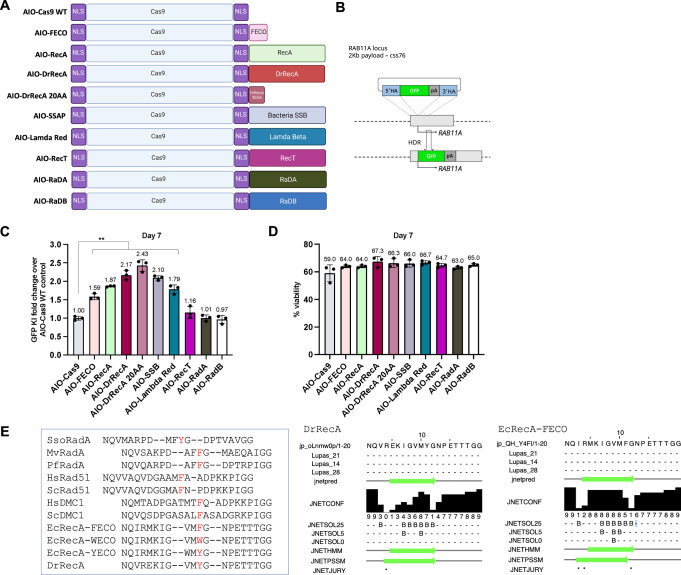

Engineering compact ‘enGagers’ in which NLS-Cas9 is fused with 20 aa ssDNA binding motifs

We directly tested the hypothesis that enhancement of targeted cssDNA integration was permitted by the DNA-binding properties of RecA/Rad51. Several seminal biochemical studies on RecA family DNA recombinases identified an evolutionarily conserved ssDNA-binding L2 loop peptide that encompasses 20–24 amino acids with an extremely conserved central aromatic residue40,43–46. To test our hypothesis, the 20 amino acid RecA peptide sequences FECO, WECO and YECO46 were first appended, as one or three tandem copies, to NLS-Cas9 linked by a Gly-Ser repeat polypeptide (Fig. 2A). When co-electroporated together with the 2 Kb cssDNA RAB11A GFP donor template into K562 cells (Fig. 2B), these designed NLS-Cas9-peptide fusions provided enhanced knock-in efficiencies similar to that of full length NLS-Cas9-RecA (p > 0.05). Except for the YECO3X construct, the fold enhancement ranged from 1.40 to 1.60 above that of NLS-Cas9, whereas the NLS-Cas9-RecA enhancement was 1.57-fold (Fig. 2C, D). Adding multiple copies of the peptide motif did not further enhance the knock-in efficiency for this 2 Kb cssDNA RAB11A GFP donor payload. These data validated the hypothesis that just installing the sequence independent cssDNA binding capability to nuclease editors could effectively enhance homologous recombination-mediated gene insertion. These rationally designed NLS-Cas9-ssDNA binding peptides are referred to as ‘enGagers’(enhanced GATALYST associated genome editors). enGagers could be powerful editing tools for targeted genome integration where a donor DNA is needed.

Fig. 2. Identification of mini enGagers with Cas9 fused ssDNA binding motifs in K562 cells.

A Schematic diagram of various Cas9-ssDNA binding motifs fusion constructs (enGagers) in all-in-one (AIO) plasmid format modified from Addgene plasmid #42230. Two nuclear localization signals were added to the N’ and C’-termini of the Cas9 protein. Cas9-RecA fusion construct was used as a positive control. FECO, WECO and YECO are 20 amino acid sequences previously identified as ssDNA binding motifs in various bacteria species of RecA(Voloshin et al., 1996), FECO3X, WECO3X and YECO3X are 3 tandem copies of the 20 aa peptides separated by multi-GS peptide linkers. B Schematic diagram of Knock in strategy of a 2Kb cssDNA donor template for RAB11A locus. C Representative FACS profiles with gating strategy showing % of GFP transgene cassette Knock in on RAB11 locus at day 7 post electroporation for various small enGagers listed in (A). D Quantification of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in fold change of various enGagers as compared to Cas9 WT at day 7 post electroporation. Note that Cas9-FECO fusion performs similarly with Cas9-RecA fusion in cssDNA mediated transgene integration (1.59- vs 1.58-fold). EnGagers with 3X tandem ssDNA binding peptides do not further enhance knock in efficiency does not enhance knock in efficiency. Bars represent mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates. Illustrations for panel C is generated with BioRender.

Optimization of SSB domains driven by SSB homologies

To engineer a larger collection of enGager constructs, we similarly tested a broader number of protein domains or peptides with ssDNA binding capability (Fig. 3A). We included the Deinococcus Radiodurans full length RecA homolog (DrRecA) and its 20 amino acid L2 peptide47,48, E.coli ssDNA binding protein49, Lambda Red subunit of bacteriophage recombineering protein50, E.coli ssDNA annealing protein RecT51, and the Archaea recombinase homologs RadA and RadB52,53. (Fig. 3A, B). Fusions to NLS-Cas9 were screened using the 2 Kb cssDNA RAB11A GFP payload in K562 cells. Whereas fusions with RecT, RadA and RadB performed no better than Cas9 alone, all the other fusion constructs outperform Cas9 WT by 1.79- to 2.43-fold (Fig. 3C) without compromising the cell viability (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, the enGager with a full-length DrRecA fusion stimulated RAB11A GFP KI by 2.17-fold and the homologous 20 amino acid L2 peptide from DrRecA further improved the KI efficiency level by 2.43-fold over that of WT Cas9. In comparison, FECO and RecA enGagers increase KI efficiency by 1.59- and 1.87-fold respectively. It is worth noting that Deinococcus Radiodurans is one of the most radiation-resistant bacteria known to date due to its exceptional DNA repair capability by its DNA recombinase DrRecA47,48. We reasoned that the L2 loop peptide from the whole RecA phylogeny can be a good candidate fusion peptide as a compact version of enGagers to enhance HDR mediated genome integration. We also highlighted a few RecA homologous L2 peptide sequences from archaea bacteria, E.coli and mammalian organism with a central aromatic amino acid (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3. Identification of additional enGagers from Cas9-ssDNA binding module chimeras in K562 cells.

A Schematic diagram of various Cas9-ssDNA binding protein and peptide fusion constructs (enGagers) in all-in-one (AIO) plasmid format modified from Addgene plasmid #42230. Two nuclear localization signals were added to the N’ and C’-termini of the Cas9 protein. Cas9-RecA and Cas9-FECO fusion constructs were used as positive controls. The fusion protein or peptides include DrRecA, 20 aa motif identified from DrRecA, SSAP, Lambda Red, RecT, RadA and RadB from Archaea. B Schematic diagram of Knock in strategy of a 2Kb cssDNA donor template for RAB11A locus. C Quantification of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in fold change of various enGagers as compared to Cas9 WT at day 7 post electroporation. Note that Cas9-DrRecA and Cas9-DrRecA20AA fusion has the highest performance in knock in with 2.17- and 2.43-fold as compared to Cas9 WT, respectively. **p < 0.01, paired t-test compared to AIO Cas9 group. D Quantification of cell viability day 7 post electroporation. Bars represents mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates for (C, D). E Amino acid sequence alignment of 20AA of multiple E.coli RecA mutant variants and RecA from archaea and mammalian organism. Dr Deinococcus radiodurans, Ec Escherichia coli, Sc Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Hs Homo sapiens, Pf P. furiosus, Sso S. solfatarcus.

We further examined how different fusion proteins affect Cas9 cutting efficiency. It is known that larger, full-size fusion proteins may sterically hinder Cas9 function, while the impact of a 20 amino acid motif is likely minimal. To investigate this, we evaluated the cutting efficiency of various Cas9 fusion constructs using AIO plasmids. These plasmids, featuring different Cas9 fusions of varying sizes, were electroporated into K562 cells without any donor templates. We quantified the cutting efficiencies by measuring the percentage of indels using Illumina NGS54. The amplicon for each condition were targeting RAB11A sites. Interestingly, while WT Cas9 and short motif fusions like FECO achieved a similar indel rate of about 80%, larger fusions such as full-length RecA and RAD51 resulted in only a 60–70% indel rate (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B), indicating slightly reduced nuclease activity. The indel patterns were identical across the board with the indel centered 4nt away from the PAM sequence (Supplementary Fig. S1C), indicating unaltered nuclease-dependent cleavage pattern.

Genome integration enhancement by enGager is ssDNA-dependent

In the initial studies (Figs. 1–3), the gRNAs were directly expressed from the same plasmid that delivered the NLS-Cas9-ssDNA binding motifs. Hereafter, except otherwise mentioned, we supplied the enGagers as in vitro transcribed mRNAs (Fig. 4A). Using mRNAs has proved advantageous for reducing the cytotoxicity of transfected DNA and enhancing delivery by using lipid nanoparticle technologies developed for vaccine development and gene therapy55.

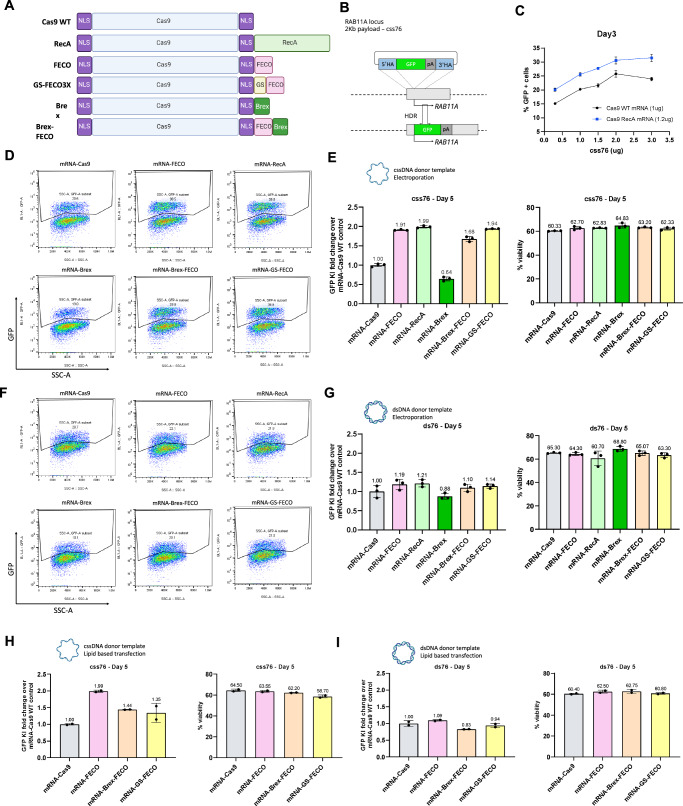

Fig. 4. enGager mediated genome integration enhancement is ssDNA dependent.

A Schematic diagram of various Cas9-ssDNA binding protein and peptide fusion constructs (enGagers) in mRNA form. Two nuclear localization signals were added to the N’ and C’-termini of the Cas9 protein. GS is a shortened poly-GS peptide linker. B Schematic diagram of Knock in strategy of a 2Kb cssDNA donor template for RAB11A locus. C Dose titration of cssDNA from 0.3, 1, 1.5, 2 and 3ug for 2Kb GFP transgene knock-in at day 3 post electroporation. Cas9-RecA mRNA enhance around 25–30% knock in efficiency than Cas9 WT mRNA at all the cssDNA dose tested in k562 cells. D Representative FACS profiles with gating strategy showing % of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock-in on RAB11 locus by cssDNA donor at day 5 post electroporation for various enGagers listed in (A) in K562 cells. E Quantification of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in fold change (left) and cell viability (right) of various enGagers as compared to Cas9 WT at day 5 post electroporation from (D). F Representative FACS profiles with gating strategy showing % of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock-in on RAB11 locus by dsDNA donor at day 5 post electroporation for various enGagers listed in A in K562 cells. G Quantification of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in fold change (left) and cell viability (right) of various enGagers as compared to Cas9 WT at day 5 post electroporation from (F). H Quantification of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in fold change (left) and cell viability (right) of various enGagers mRNA as compared to Cas9 WT mRNA with cssDNA donor at 5 days post-delivery in HEK293 cells by lipofectamine 3000 transfection. I Quantification of 2Kb GFP transgene cassette Knock in fold change (left) and cell viability (right) of various enGagers mRNA as compared to Cas9 WT mRNA with dsDNA donor at 5 days post-delivery in HEK293 cells by lipofectamine 3000 transfection. Bars represents mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates. Illustrations for panels (E, G–I) are generated with BioRender.

We initially validated the RecA enGager mediated enhancement of the 2Kb RAB11A GFP reporter integration in K562 cells by electroporation. When co-electroporated with various doses of cssDNA donor templates at 0.3, 1, 1.5, 2 to 3 ug per reaction, the full-length RecA enGager (at 1.2 ug mRNA per reaction) significantly increased the GFP KI efficiency compared to WT Cas9 mRNA provided at equimolar levels (Fig. 4B, C). Similar studies were conducted for the enGager mRNAs expressing the ssDNA binding and/or Brex recruitment peptides shown in Fig. 4A. The results were similar to that observed with the enGagers delivered by AIO plasmids: the addition of an ssDNA binding peptide was as effective as full-length RecA at enhancing the percentage of cells expressing genomically integrated eGFP, with Brex peptides having no benefit (Fig. 4D, E).

As the RecA L2 peptides also bind dsDNA, albeit with much lower binding affinity compared to ssDNA46, we sought to investigate if these enGagers can also facilitate integration of dsDNA donor templates. Using co-electroporation of mRNA enGagers/sgRNA and 1 ug of 2Kb RAB11A GFP donor template either in ssDNA (css76) or dsDNA (ds76) form, we found that adding ssDNA binding motifs to Cas9 stimulated genomic integration only when the donor DNA was single-stranded (Fig. 4D, E) but not double-stranded (Fig. 4F, G). Similar dependence of ssDNA binding fusions on cssDNA donor templates were observed when the constructions were introduced into HEK293 cells by Lipofectamine 3000 (Fig. 4H, I).

We observed similar cellular viability of the K562 cells post-electroporation when the editing enzymes were provided as either RNA (Fig. 4E) or DNA (Fig. 3D) or when the donor DNA was provided as ssDNA or as dsDNA in either K562 (Fig. 4E, G) or HEK293 (Fig. 4H, I) cells.

FECO nuclease significantly enhances nuclear localization and expression of single-stranded DNA templates

The key element of the enGager mechanism is the formation of a tripartite complex, which enhances the local concentration of the cssDNA template within the cell nucleus. To validate this mechanism, we designed an experiment to demonstrate the active nucleus transfer of the cssDNA template.

cssDNA has been demonstrated as episomal transgene expression vectors56,57. First, we engineered a circular single-stranded DNA template, css39, containing the mCherry gene expression cassette under the control of the EF-1α promoter, allowing for episomal mCherry expression without genomic integration (Supplementary Fig. S2A). css39 must enter the nucleus and leverage the cell’s transcriptional machinery for mCherry expression. We hypothesized that a higher concentration of css39 in the nucleus would lead to an increase in mCherry expression. To confirm that any changes in expression were specific to single-strand DNA, we also produced a double-stranded version of css39, named ds39, for comparison (Supplementary Fig. S2B).

Indeed, when we co-electroporated css39 with FECO mRNA without a gRNA, we observed a ~73% increase for mCherry expression as compared to css39 only, significantly higher than css39 co-electroporated with Cas9 mRNA. (Fig. S2B & C). As a comparison, mCherry expression from dsDNA templates were not significantly changed with or without co-delivery of FECO, or WT Cas9 mRNA (Fig. S2B & C).

These data suggest that more cssDNA was delivered successfully to the nucleus when using the enGager FECO. Importantly, the increase in mCherry expression and effective nucleus translocation is cssDNA dependent.

enGagers enhance ultra-large transgene integration on various genomic loci

We next assessed the efficacy of enGagers more broadly on various genomic loci and for donor payload with various sizes, especially for 4 and 8Kb payloads that are at the packaging capacity limit for AAV6 and lentivirus, respectively. Utilizing highly purified mRNAs for expressing the FECO and RecA enGagers, we tested the efficiency of GFP transgene KI on two genomic loci with various lengths of payloads. For RAB11A target locus, we designed 2Kb (css76), 4Kb (css116) and 8Kb (css167) cssDNA payloads (Fig. 5A). For another clinically relevant immune cell therapy locus, B2M (Ren et al., 2017), we designed 2Kb (css27) and 4Kb (css88) cssDNA payloads (Fig. 5D). When mRNA enGager/sgRNA with cssDNA donor templates were co-electroporated to K562 cells, FECO and RecA enGagers increased the KI efficiency of 2Kb RAB11A GFP to 44.6-48.5%, while only 30.10% was achieved by WT NLS-Cas9. For the 4Kb payload, FECO and RecA enGagers increased the GFP transgene KI to 11.07–13.77% compared to 6.17% and for 8Kb payload, to 3.73–5.17% from 2.97% (Fig. 5B). Similarly, at the B2M locus, FECO and RecA enGagers increased the KI efficiency to 39.60–43.97% from 30.13% for the 2Kb GFP transgene, and to 10.67–14.07% from 6.27% for the 4Kb GFP transgene (Fig. 5E). As a negative control, mRNA for Cas9-Brex fusion did not enhance genomic integration efficiency of the cssDNA. Cell viability was not affected by 1 ug Cas9 or enGager mRNA (Fig. 5C, F) as compared to Mock electroporation.

Fig. 5. enGagers in mRNA form enhance genome integration on various locus and large payload.

A Schematic diagram of Knock in strategy of 2Kb (css76), 4Kb (css116) and 8Kb (css167) cssDNA donor templates for RAB11A locus. B Quantification of % of 2Kb (left), 4Kb (middle) and 8Kb (right) GFP transgene cassette Knock-in for various mRNA enGagers RAB11A day 13 post electroporation in K562 cells. C Quantification of cell viability for 2Kb (left), 4Kb (middle) and 8Kb (right) GFP transgene cassette Knock-in for various mRNA enGagers on RAB11A locus day 13 post electroporation in K562 cells. D Schematic diagram of Knock in strategy of 2Kb (css27), 4Kb (css88) cssDNA donor templates for B2M locus. E Quantification of % of 2Kb (left) and 4Kb (right) GFP transgene cassette Knock-in for various mRNA enGagers on B2M locus day 13 post electroporation in K562 cells. F Quantification of cell viability for 2Kb (left) and 4Kb (right) GFP transgene cassette Knock-in for various mRNA enGagers on B2M locus day 13 post electroporation in K562 cells. Bars represents mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates for (B, C, E, F). ***p < 0.001; ns non-significant, paired t-test compared to mRNA-Cas9 groups for C&E. G Schematic diagram showing enGager mRNA/sgRNA/cssDNA delivery into cells using LNP formulation. Once the editor components were delivered into the cytoplasm, the enGager mRNA is translated into endonuclease protein which forms a complex with sgRNA and cssDNA donor template. The assembled tripartite editing machinery complex then can be effectively shuttled into the nucleoplasm and tether onto the target genomic locus for transgene integration. Quantification of GFP transgene knock-in on RAB11A locus in HEK293 cells (H) and HepG2 cells (I) by LNP delivery at day 2, day 6 and day 9 post-delivery. Data were compared to mRNA-WT Cas9. Bars represents mean ± SD from 2 biological replicates. Illustrations for panel (G) is generated with BioRender.

Compatibility with lipid nanoparticle delivery

For whole animal gene modifications, lipid nanoparticles (LNP) have been successfully used to deliver Cas9 family editors for gene deletion, base editing and HDR based short gene insertion in rodent and non-human primates55,58–61. In humans, Gillmore et al. successfully used a specialized LNP formulation in a clinical trial with an in vivo gene-editing approach to reduce the serum level of transthyretin (TTR) by targeting the TTR gene as a therapeutic approach to treat Transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR)62. We evaluated if the FECO enGager and cssDNA donor template could be co-delivered with LNP to potentiate EGFP transgene integration efficiency in various cell types (Fig. 5G). When a commercially available LNP preparation was used to deliver the 2Kb GFP transgene cssDNA into HEK293T (Fig. 5H) or HepG2 (Fig. 5I) cells, FECO enGager demonstrated a persistent enhancement of a 2Kb GFP integration and expression at the RAB11A locus over multiple days following LNP delivery. These data demonstrated that the enGagers can be delivered in mRNA form by LNP to substantially improve genome integration efficiency and can potentially be applied for future in vivo genome modifications.

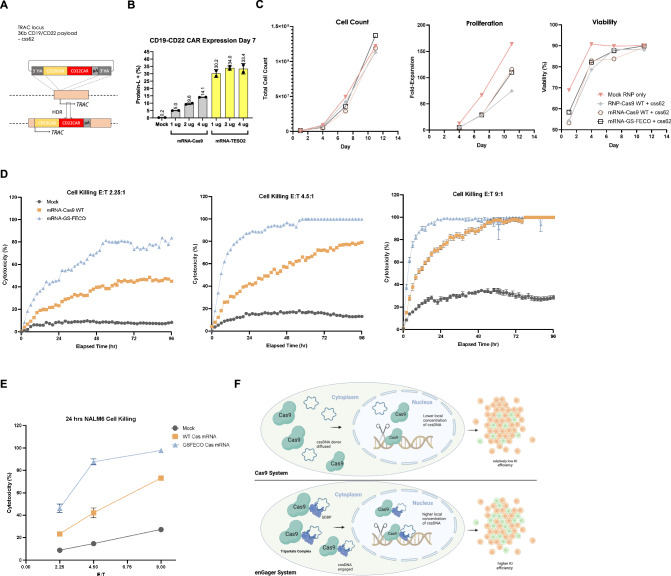

Efficient CAR-T engineering with enGagers

Modifying a patient’s own T-cells in vitro followed by adoptive transfer back to the patient represents one of the most immediate applications for genome engineering for cellular therapy. We therefore examined the ability of the FECO enGager to engineer primary T cells by inserting a functional chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) transgene cassette within the T cell receptor alpha constant chain (TRAC) locus (Eyquem et al., 2017). We chose a ~3Kb CD19-CD22 dual CAR construct (css62) that has demonstrated anti-tumor function for potential treatment of patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) and Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) (Fig. 6A and Fry et al., 2018). PE-conjugated Protein-L binder was used to analyze transgene expression as a marker for knock-in efficiency. When the CD19-CD22 dual CAR cssDNA donor template was delivered into human CD4+/CD8+ primary pan-T cells, the mRNA encoding one of the lead enGagers as evidenced in the K562 cell studies (GS-FECO) achieved 30.2% to 33.4% targeted CAR integration and expression at day 7 post-delivery, whereas WT NLS-Cas9 mRNA only achieved 5% to 14.1% of CAR KI over a range of enGager mRNA dosages (Fig. 6B). Especially with the lower dose of mRNA editors preferred for studies involving patients, the GS-FECO enGager enhanced cssDNA-mediated CAR-T integration by >6 fold (Fig. 6B). Importantly, GS-FECO enGager mediated enhancement of dual CAR-T engineering did not compromise T cell counts, proliferation and cell viability compared to WT Cas9 (Fig. 6C). To further validate the robustness of the enGager platform, we engineered the CD19-CD22 bispecific CAR-T from a second donor with FECO enGager. These CAR-T cells also demonstrated a similar improvement, with up to a 2-fold improvement in FECO enGager over the WT Cas9 mRNA. However, the overall knock-in efficiency was lower than that observed in the first T-cell donor, highlighting significant donor-to-donor variability in CAR-T engineering (Supplementary Fig. S3A–C). Additionally, we evaluated the NHEJ indel ratio by measuring the knock-out ratio of CD3, expressed from the targeted locus, using a fluorescent anti-CD3 antibody (Eyquem et al., 2017). While the negative control mock exhibited a CD3+ percentage of 99%, both WT and FECO enGager showed less than 4% CD3+, indicating close-to-saturated nuclease activity in both WT and FECO enGager (Supplementary Fig. S3D).

Fig. 6. CAR-T engineering by enGager with superior efficiency than WT Cas9.

A Schematic diagram of Knock in strategy of 3Kb CD19/CD22 dual CAR (css62) cssDNA donor templates for TRAC locus in primary T cells. B Quantification of % of CD19/CD22 CAR Knock-in using cssDNA donor analyzed by CD19 binder for various doses of Cas9 WT and Cas9-GS-FECO enGager mRNA at 1 ug, 2 ug and 4 ug. Data were collected at day 7 and day 11 post electroporation of primary T cells. Cas9-GS-FECO enGager achieves ~ 4- to 6-fold higher CAR-T engineering efficiency than Cas9 WT. Bars represents mean ± SD from 2 biological replicates. C Characterization of the engineered CAR-T cells or mock treated T cells for total cell count, cell proliferation fold change and cell viability over time. D NALM6 leukemia lymphocyte killing curve of unengineered T cells, CD19-CD22 dual CAR-T cells engineered with 2 ug of WT Cas9 mRNA and 2 ug of GS-FECO enGager mRNA over the course of 96 h. Effect (T cells): Target (NALM6 cells) are at 2.25:1 for left panel, 4.5:1 for middle panel and 9:1 for right panel. E NALM6 cell killing function of CAR-T cells at 24 h for E:T ratio at 2.25:1, 4.5:1 and 9:1. Bars represents mean ± SD from 2 biological replicates. F Schematic diagram of engineered enGagers with single stranded DNA binding protein (SSBP) can recruit cssDNA donor template and form a tripartite editing machinery for efficient translocation of the entire editing complex from cytoplasm to nucleus. As a result, the donor DNA has higher effective local concentration in the nucleus for more efficient homologous directed genome integration. This process works more prominently with cssDNA. Illustrations for panel (F) is generated with BioRender.

To test the anti-tumor function of the engineered CAR-T cells, we use the Incucyte live imaging approach to monitor the cell killing functions over the course of 96 h. Cytotoxicity at NALM6 leukemia lymphocyte cells mediated by primary T-cells, modified by CD19-CD22 dual CAR integration under each enGager transfection condition, were determined at Effector (T cell): Target (NALM6 cells) ratios of 2.25:1, 4.5:1 and 9:1. In each instance, tumor cell killing by the GS-FECO enGager mRNA was more rapid than that of the NLS-Cas9 mRNA, presumably because of the much higher percentage of engineered CD19-CD22 dual CAR-T cells in the population. Importantly, at 9:1 E:T ratios, GS-FECO-modified T-cells enabled killing of 100% of NALM6 cells within 24 hrs and suppressed tumor cell regrowth. Overall, these studies demonstrated a more effective and durable cancer cell killing function compared to WT Cas9 mRNA engineered dual CAR-T cells at every E:T ratio tested (Fig. 6D, E).

enGager-mediated HDR exhibits minimal off-target effects and high integration specificity in T cells

One concern with Cas9-mediated genome integration is the potential for off-target effects54. Since Cas9 uses a 20-nt gRNA to search and locate HDR sites, there is a risk that Cas9 could target genomic loci with only a few mismatches, leading to off-target DSBs. These off-target DSBs can result in two possible outcomes. The first, more likely outcome is off-target indel formation through NHEJ, which requires only the presence of a DSB. The second, less likely outcome is off-target integration. However, because the homology arms typically do not match off-target sites, off-target integration is less common than indel formation.

To evaluate the off-target effects of enGager in T cells, we performed HDR-mediated integration at the RAB11A site using WT Cas9 mRNA and FECO mRNA, along with the css76 harboring a 2 kb GFP integration template (Supplementary Fig. S4A). This resulted in approximately 15% integration with WT Cas9 mRNA and 28% integration with FECO mRNA. After 7 days, we collected cell samples and analyzed the amplicons from four potential off-target sites by NGS (Supplementary Fig. S4B, C)54. Nonetheless, across the four off-target sites, we detected less than 0.5% indels in both WT Cas9 and FECO enGager (Supplementary Fig. S4D), indicating that the off-target indel rate is extremely low and not elevated by FECO enGager.

We further assessed potential on and off-target integration mutagenesis using PCR and then followed by NGS. PCR primers designed for NGS amplicons generated a ~300 bp PCR fragment if no integration occurred. However, if integration had taken place, a ~2 kb PCR fragment would also be produced, corresponding to the integrated GFP payload. We observed the ~2 kb PCR fragments in the on-target lanes with correct sequence verified, but no such bands appeared in the off-target lanes for either WT Cas9 or FECO enGager (Supplementary Fig. S4C). This result suggests that off-target integration and on-target mutagenesis by FECO enGager and cssDNA donor is minimal, as expected.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and characterized a set of enGager endonucleases by fusing Cas9 with various full-length single-stranded DNA binding protein modules or their corresponding miniaturized ssDNA-binding motifs of 20 amino acids. When applied for targeted genome integration with cssDNA donor templates to diverse genomic loci across multiple cell types, these enGagers outperformed conventional editors by up to several times for small and large transgene knock-in. Using one of the compact enGagers, we demonstrated sizeable chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) transgene integration in viral free manner in primary T cells with exceptional efficiency and anti-tumor cell function. As shown in Fig. 6F schematic diagram, the engineered enGagers with single-stranded DNA binding protein (SSBP) can recruit cssDNA donor template and, together with a gRNA, for efficient editing of the target genome. The role that ssDNA binding plays in the hypothesized tethering of the donor DNA with the Cas9 endonuclease over the target site for enhancing gene modification is further suggested by the dependency of the integration on ssDNA (Fig. 4), which the appended motifs have a much stronger affinity for ssDNA than dsDNA46. This mechanism was further validated by an mCherry expression experiment, where only FECO was able to increase episomal mCherry expression, indicating a higher local concentration of the DNA template in the nucleus achieved by FECO enGager (Supplementary Fig. S2). These enGager editors expanded the gene-editing toolbox for potential cell and gene therapeutic development based on ssDNA-mediated non-viral genome engineering.

Previously, it was challenging to achieve gene knock-in for >4 kb payload especially for non-viral knock-in approaches. Although we observed integration efficiency to decrease with increasing length of donor DNA, we observed that improved efficiencies were realized by cssDNA tethering to the enGagers at all DNA cargo sizes. Because the GATALYST cssDNAs can be produced with sizes of up to 20 kb whereas viral DNAs are more constrained in size, there is also the opportunity to considerably increase the size of the homologous sequences flanking the donor DNA to increase efficiencies with larger inserts. This flexibility makes gene knock-in improvement by enGager more attractive for many therapeutic applications that require large inserts to be functional. Additionally, the efficacy of enGagers was tested against different variables including multiple cell types, loci and payload sizes, and enGagers exhibited consistent improvement in knock-in efficiency. This improvement also includes an increase in efficiency for ultra-large 8 kb payload from ~3% to ~5%. Since many previous studies struggled to achieve meaningful knock-in for >4 kb payload, our finding may open new opportunities for precise gene therapy field. These new opportunities include knock-in of multiple large transgenes and along with long regulatory elements. enGager also improves knock-in of smaller payload cargos, therefore the benefit of the enGager is not just limited to large payload. Also, unlike AAV viral mediated delivery, enGager delivers the donor cssDNA to the nucleus without the concerns of viral toxicity and unwanted integration while being relatively easy to manufacture. It is important to note that these improvements did not increase common gene engineering risks such as off-target indels and off-target integration (Supplementary Fig. S4). One quest in the genome integration field is to enhance multiplexed knock-in efficiency for more flexible genomic engineering. While biallelic modification is desired for high and stable expression, it is notoriously difficult to achieve. To distinguish monoallelic from biallelic targeted integration edits, we introduced two different cssDNA donor payloads harboring GFP (css76) or mCherry (css32) targeting the two alleles of the same locus RAB11A. In a FACS profile, cells stably expresses both GFP and mCherry proteins suggest biallelic editing. We electroporated 1 µg of each GFP and mCherry donor into primary T-cells along with mRNA of either WT Cas9 or FECO enGager (Supplementary Fig. S5A). The total expression of either reporter was 17.6% in WT Cas9 and 21.9% in FECO enGager, representing approximately a 25% increase from WT Cas9. The percentage of cells expressing both GFP and mCherry was 1.8% for WT Cas9 and 3.0% for FECO enGager, a 1.67-fold increase highlighting a significant improvement in achieving biallelic modifications (Supplementary Fig. S5B, C). Natural Killer (NK) cells represent another pivotal immune cell for potential genome editing based allogenic cell therapy. Previously non-viral targeted engineering of NK cells was scarce due to technical challenges. To further scrutinize the efficacy of FECO enGagers across various primary cell lines, we extended our investigation to NK cells. We again used various amounts of 2 kb cssDNA (css76) payload harboring a GFP, targeting the RAB11A locus. After electroporation, the FECO engager was assessed against WT Cas9 at day 7. Similar to the findings in K562 and primary T cells, the FECO enGager demonstrated a significant enhancement in GFP Knock-in efficiency compared to its WT Cas9 counterparts, reaching up to a ~1.8-fold increase (Supplementary Fig. S6A–C). However, the overall GFP expression level is much lower compared to K562 or T cells, indicating that further optimization is needed for NK cells in future studies. Nonetheless, these results demonstrate the promising potential of utilizing NK cells in non-viral genome engineered cell therapy and highlight the robustness and versatility of the enGager platform, which is capable of enhancing various types of primary cells. These further studies show that enGager improves biallelic editing efficiency in primary T-cells by 1.67-fold which is desirable for more stable expression of inserted protein via multiplex multiallelic knock-in strategy. In addition, enGager also improved knock-in efficiency in NK cells which further demonstrates robustness of the enGager editing system in primary immune cells.

One of the most critical findings of this study was that the 20aa single-stranded DNA binding motif of RecA showed comparable improvement relative to that of the full-length RecA protein. This observation underscores our hypothesis that the formation of tripartite complex rather than the recombination activity of RecA contributes to knock-in efficiency enhancement. We reason that the enGager platform can benefit from the 20aa motif over full-length proteins in several ways. First, the 20aa motif fusion enGagers are smaller than full protein fusion enGagers. Since increasing the size of Cas9 may sterically impede Cas9 function, minimizing the modification to 20aa motif is less likely to affect Cas9 editing function. This was confirmed by demonstrating that full-size protein fusions indeed lower cutting efficiency, whereas shorter 20 amino acid motifs do not (Supplementary Fig. S1). Second, since the 20aa motif has selective single-stranded DNA binding capacity, it is less likely to have the unwanted dsDNA-binding side effect that the full-length Rec-family protein have. Third, the extremely compact size of the 20aa motif fusion affords the opportunity for adding additional domains with other functions that may benefit Cas9 activity. Fourth, the peptide motifs identified from the enGagers could serve as a programmable module to install the ssDNA binding function to any protein enzymes or chaperons for more efficient cytoplasm to nucleus shuttling of ssDNA, potentially solving one of the fundamental challenges in DNA nanomedicine. While enGagers demonstrated significant improvement in gene knock-in efficiency, there are still some limitations of enGagers that calls for further studies. Further improvements in the ssDNA binding motifs added to the enGagers and/or altering the sizes of the homologous sequences surrounding the donor DNA remain to be followed-up to further enhance locus specific integration of the extra-large transgenes. We also acknowledge the variability observed between primary donor T cells and recognize the need for broader validation across more donors to establish robustness for clinical application. Additionally, further comprehensive analyses with orthogonal sequencing approaches for off-targeting analysis will be required to meet regulatory standards for clinical applications of TESOGENASE. Future studies on expanded donor sample sizes and more sensitive, unbiased off-target detection methods are expected to strengthen the translational readiness of TESOGENASE.

Methods

Ethics

We confirm that this study complies with all relevant ethical regulations. The study protocol was approved by the appropriate institutional review board/ethics committee at Full Circles Therapeutics Inc., Quintara Bioscience Inc. and Northeastern University.

Plasmid constructs

For all-in-one (AIO) plasmid construct design for various enGagers (Supplementary Table 1), ssDNA binding protein and peptide sequences were synthesized and assembled into an AIO plasmid modified from Addgene plasmid #42230 by golden gate cloning. Complex fusion constructs were cloned using multi-piece DNA Gibson assembly approach. For mRNA constructs, various enGager coding sequences were cloned into a modified vector plasmid from pGEM®-4Z vector containing T7 promoter, 5’ UTR, Cas9 fusion sequence ORF 3’ UTR, bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal (bGH polyA), and 64 poly adenine sequence (Promega). Supplementary Table 1 listed the amino acid sequences of the enGager fusion protein and WT Cas9 endonuclease.

cssDNA production and purification

The cssDNA production and purification is previously describe18. Briefly, the cssDNA donor sequences (transgene sequence flanked by 5’ and 3’ homology arms of 300–500 nt in length) were designed as dsDNA and cloned into a phagemid vector. The phagemid vector utilizes the M13 origin of replication to amplify cssDNA via rolling circle amplification. An XL1-Blue E. coli strain was co-transformed with the M13 helper plasmid and the phagemid containing the dsDNA donor template and selected on agar plates with kanamycin (50 µg/mL) and carbenicillin (100 µg/mL) to ensure the transformed bacteria contained both plasmids. A single colony was picked and grown for ~24 h (37 °C, 225 rpm) in 250 mL of 2xYT media (1.6% tryptone, 1% yeast extract, 0.25% NaCl) to a final O.D.600 of 2.5-3.0.

After growth, the bacteria were pelleted and discarded. The remaining supernatant containing phage particles was precipitated with PEG-8000. The precipitated phage particles were then pelleted by centrifugation, washed, and lysed in 20 mM MOPS, 1 M Guanidine-HCl, and 2% Triton X-100. The cssDNA released from the phage was then extracted using the NucleoBond Xtra Midi EF kit (Macherey-Nagel). Recombinant cssDNA was verified by Nanopore DNA sequencing. The purity of resulting cssDNA was also confirmed by gel electrophoresis. Sequences and a gel image of the cssDNA template are presented in Supplementary Figure S7 and Supplementary Data 1.

mRNA production and purification

mRNA in this study was produced through in vitro transcription from constructed pGEM®−4Z plasmids containing T7 promoter, 5’ UTR, Cas9 fusion sequence ORF 3’ UTR, bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal (bGH polyA), and 64 poly adenine sequence were cloned. To linearize the DNA, Spe1 restriction site was inserted at the end of the 64 poly adenines. After plasmids were produced, ~50 µg of plasmids were digested using Spe1 to cut the plasmids for linearization. After 24 hours, the resulting linear DNA was cleaned through a DNA clean-up kit (Zymo). The linear DNA fragments were then introduced to HiScribe™ T7 mRNA Kit with CleanCap® Reagent AG (New England biolab). For each reaction, 1 µg of templates were mixed with 2 µl 10x reaction buffer, 2 µl of ATP (60 mM), 2 µl of GTP (50 mM), 2 µl of UTP (50 mM), 2 µl of CTP (50 mM), 2 µl of Cap Analog (40 mM) and 2 µl of RNA polymerase Mix. Then Nuclease-free water was added to the final volume of 20 µl to the mixtures. The mixture was then incubated at 37 C° for 2 h. After 2 h of in vitro transcription, the resulting mRNA was purified using RNA Clean & concentrator (Zymo). DNase was also used during the purification to remove residual DNA templates from the solutions. After in vitro transcriptions, each mRNA was analyzed using agarose gel analysis. 500 ng of mRNA were diluted to 20 ul of nuclease-free water then 20 ul of 2 x RNA loading dye (ThermoFisher) was added. The mixture was then incubated at 80 °C for 15 min. After incubation, the mRNA mixtures were immediately transferred to Ice and ran on the clean 1% agarose gel made from TAE buffer.

LNP formulation and delivery

HEK293T and HepG2 cells were plated on 24 well format day, a day prior to transfection in 500 uls of antibiotics free and reduced serum (5%) DMEM media. 150k cells were plated per well of a 24 well plates. On the day of transfection, cells were pretreated with 5 ul of APoE (100X). For the LNP particles, the Hepta 9™ mRNA Transfection Kit (Precision NanoSystems) was used. Three different aqueous phases were prepared, each containing a combination of RAB11A sgRNA and three different mRNAs: Cas9 mRNA, FECO mRNA, and Brex mRNA. The formulation for these phases consisted of 13 µL of mRNA (25 µg), 8 µL of RAB11A guide (80 µM; 20 µg), 3.2 µL of formulation buffer 1, and 7.8 µL of RNase-free buffer, totaling 32 µL. gRNAs synthesized by IDT contain chemical modification in 5’ and 3’ end to increase stability. (Alt-R™ CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNA, containing 2′-O-methyl and 3′-phosphorothioate (MS) modifications on 3 bases at both the 5′ and 3′ ends) cssDNA donor formulation containing 30 µg DNA in aqueous phase was made separately. After preparing the aqueous phase formulation, LNP formulation was performed using the NanoAssemblr® Spark™ system (Precision NanoSystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions with setting number “3.” The formulation process included 48 µL of dilution buffer, 32 µL of aqueous phase, and 16 µL of organic phase containing LNP particles. After the preparation, LNP formulations were diluted at 1:1 ratio by dilution buffer. mRNA LNP formulation was administered in 1:1 ratio in combination with donor LNP formulation. LNP formulations were characterized for hydrodynamic size, polydispersity index, and zeta potentials, using dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments). LNP encapsulation efficiency (EE%) of cssDNA and mRNA was quantified using Quant-iT™ OliGreen ssDNA assay kit and Quant-it™ RiboGreen RNA assay kit (Thermo Fisher). The efficiency of nucleic acid encapsulation is over 90% as part of the quality control. Cells were incubated in 37 °C for 72 h for LNP administration. After that GFP expression was measured using Flow cytometry assay at day 2, 6 and 9 post transfection.

Lipofectamine transfection

For lipofectamine transfection of mRNA editors/sgRNA (mRNA cocktail) and DNA donors, 24 well plates are coated with PLO for 2hrs. Plates are washed twice and dried before they were plated with cells. For each well 2 × 105 HEK293T cells were plated on Day 0 using 500 ul of complete DMEM media. On Day 1, 250 ul of media was slowly replaced with equal volume of serum free and antibiotic free DMEM media. Both mRNA cocktail and donor DNA were prepared separately as per the conditions. To prepare the mRNA cocktail, individual mRNA construct (1 µg/well) and RAB11A sgRNA (2.54 ul/well from a stock of 80 uM) were diluted in 1:1 ratio with lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) and incubated on ice for 10–15 min; for donor DNA prep, both single stranded and double stranded DNAs were packaged separately at 1 µg of donor DNA per well. Respective DNA was mixed with P3000 reagent (1ug/well) and the whole mix was diluted with lipofectamine 3000 at 1:1 dilution. The DNA cocktail was also incubated at RT for 10–15 min. After 15 min of incubation, mRNA cocktail and DNA cocktail were added at 1:1 ratio each well. Cells were then allowed to sit for 48 h after which they were transferred from 24 well plate format to 6 well plate with 1 ml of DMEM media. FACS analysis was performed on D5 post transfection.

Cell culture

K562 cells (ATCC, CCL-243) were maintained in RPMI-1640 media with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. HEK293T (ATCC) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco). HepG2 cells (HB-8065™) were cultured in ATCC-formulated Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (Catalog No. 302003) supplemented with 10% FBS. T cells were isolated using a StraightFrom Leukopak CD4/CD8 MB Kit in MultiMCAS Cell24 Separator Plus (Miltenyi). T cells were cultured and expanded in TexMACS Medium (Miltenyi) supplemented with 200 IU/mL Human IL-2 IS (Miltenyi). T cells were activated for 2 days with T Cell TransAct (Miltenyi) before electroporation. All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2, unless otherwise specified. Cell count viability was determined using Via2-Cassette in NucleoCounter® NC-202 (ChemoMetec) on specified days after engineering. The experiments related to primary human cell engineering are covered by the IRB ethical approval by Full Circles therapeutics Inc. and Northeastern university.

NK cells isolation and activation

Primary human NK cells were harvested from fresh human peripheral blood Leukopak (Miltenyi). NK cells were isolated using a density gradient centrifugation method, followed by negative selection with EasySep buffer (Stem Cell Technologies). After diluting the blood with an equal volume of EasySe buffer (Stem Cell Technologies), cells were centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in EasySep buffer (Stem Cell Technologies), combined, and counted. The cell suspension was then diluted to the desired concentration, and an antibody cocktail was added, followed by a brief room temperature incubation. RapidSphere (Stem Cell Technologies) were immediately added for magnetic separation, with the process repeated to ensure purity. Finally, cells were prepared for cryopreservation in CryoStor (Stem Cell Technologies).

For activation, anti-Biotin MACSiBead Particles (Miltenyi) were resuspended and added at a ratio of 5 µL per 106 NK cells. The bead mixture was centrifuged and resuspended in a fresh culture medium. NK cells were resuspended at a density of 106 cells/mL in NK MACS Medium with 5% AB serum, 1000 IU/mL IL-2, and 10 U/mL DNase1. The cell suspension was combined with the MACSiBead Particles (Miltenyi) and plated in 24-well plates. Post-thaw NK cells were thawed, washed, and resuspended in complete media, followed by the addition of MACSiBead Particles. (Miltenyi) The cell suspension was plated and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Media was topped up on Day 2 post-thaw with NK base media supplemented with 5% HSA and 1000 IU/mL IL-2.

Electroporation of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein, AIO plasmid and mRNA/sgRNA complex with DNA donor

All K562, HEK293T, NK, and T cell electroporation were performed using the Amaxa™ 96-well Shuttle™ with the 4D Nucleofector (Lonza). Cas9 nucleases (Aldevron) and sgRNAs (IDT) were precomplexed in supplemented Nucleofector® Solution for 20 min at room temperature, and the RNP solution was made up to a final volume of 2.5 µL (10X). For electroporating K562 cells, the SF Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector™ Kit was used with 250,000–500,000 cells per reaction and program FF-120. For electroporating HEK293T cells, the SF Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector™ Kit was used with 200,000–300,000 cells per reaction and program FS-100. For electroporating primary T cells, 2 × 106 cells per reaction were used with the P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector™ Kit and program EO-115. The indicated amount of HDR donor template (cssDNA or dsDNA) was co-electroporated with the RNP. For electroporating primary NK cells, 2 × 106 cells per reaction were used with the P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector™ Kit and program DN-100. For RNP electroporation, the default used 1 µM of nuclease and 2 µM of gRNA final concentration in the electroporation mixture. gRNA contains chemical modifications at the 5’ and 3’ ends to increase stability. For mRNA or AIO plasmid enGager electroporation, 1–1.5 µg of mRNA or DNA was electroporated together with the indicated amount of HDR donor templates, using the same electroporation parameters as for RNP electroporation. The amount of Cas9 mRNA and protein used can vary from the default depending on the experimental setting and cell types; it is indicated if a different amount was used. After electroporation, cells were incubated in a humidified 32 °C incubator with 5% CO2 for 12–24 h, followed by transferring to a 37 °C incubator for additional days. The mRNA sequences used for the studies are organized in the supplemental table.

For the mCherry episomal expression analysis, 4 µg of css39 and 5.65 µg of ds39 were electroporated into 0.5 million K562 cells. Additional ds39 was included to compensate for the extra sequences in ds39, ensuring the same molar ratio as css39. Flow cytometry analysis was conducted two days after electroporation, following standard electroporation and flow cytometry protocols. gRNA target sequences in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Flow cytometry analysis

All flow cytometry was performed on an Attune NxT flow cytometer with a 96-well autosampler (ThermoFisher Scientific). Unless otherwise indicated, cells were collected 3–14 days post electroporation, resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (2% BSA in PBS) and stained with 7-AAD (BioLegend) as a dye for cell viability assay, and the indicated cell-surface marker, such as PE labelled Protein L (ACROBiosystems), or FITC-Labeled Human CD19 (20–291) Protein, Fc Tag (ACROBiosystems). To obtain comparable live cell counts between conditions, events were recorded from an equivalent fixed volume for all samples. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo_v10.8.0_CL software with exclusion of subcellular debris, singlet gating and live/dead staining. Data analysis is performed using FlowJo_v10.8.0_CL software. Data were plotted using Prism GraphPad 10.0. Control FACS profiles for each experiment are shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

Cutting efficiency indel percentage

For cutting efficiency indel analysis utilized K562 cells. After electroporation, K562 cells were incubated for three days before collected for genomic DNA extraction. The collected cells were lysed with Cell Extraction Buffer (Invitrogen) to obtain genomic DNA samples. Primers (Supplementary Table 3) were designed to flank either the RAB11A locus or four RAB11A off-target sites to generate amplicon DNA, which was sequenced using Illumina NGS. The sequencing results were then analyzed using CRISPRESSO254,63.

CAR-T cell engineering

Primary T cells were isolated and enriched from Leukopak using Pan T Cell MicroBead Cocktail with MultiMCAS Cell24 Separator Plus (Miltenyi), CD4+ and CD8+ pan T cells were cryopreserved for later use. T cells were cultured and expanded in TexMACS Medium (Miltenyi) supplemented with 200 IU/mL Human IL-2 IS (Miltenyi). T cells were activated for 2 days with T Cell TransAct (Miltenyi) before electroporation. 48 h after initiating T-cell initiation and activation, T cells were electroporated using Amaxa™ 96-well Shuttle™ in 4D Nucleofector. 2 × 106 cells were mixed with 25 pmol of Cas9 WT protein or 1 ug of enGager mRNA and 50 pmol of gRNA into each well. For cssDNA engineered cells, 2 µg of cssDNA encoding bi-specific CD19 × CD22 CAR (Fry et al., 2018) was electroporated with RNP or mRNA/sgRNA cocktail targeting TRAC locus. Following electroporation, cells were diluted into culture medium in the presence of T Cell TransAct with 1 µM DNA-PK inhibitor M-3814, and incubated at 32 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells were then washed and subsequently transferred into G-Rex 24 Multi-Well Cell Culture Plate (Wilson Wolf) in standard culture conditions at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in IL-2 supplemented TexMACS medium and replenished every 3−4 days. CAR expressions were determined using PE labelled Protein L (ACROBiosystems), or FITC-Labeled Human CD19 (20–291) Protein, Fc Tag (ACROBiosystems). For off-target effect analysis, we incubated css76 containing the GFP payload and replaced the TRAC gRNA with RAB11A gRNA. The resulting cells were collected 7 days after electroporation and lysed with Cell Extraction Buffer (Invitrogen) to obtain genomic DNA samples. The cell lysates were then used to generate Illumina NGS amplicons for off-target site indel analysis using CRISPRESSO254,63. The resulting amplicons were also analyzed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis to detect a 2 Kb integration band.

Statistics & reproducibility

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism GraphPad 10.0. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of indicated number of biological replicates, unless otherwise specified. Sample sizes were determined based on experimental design. Statistical significance was assessed using t-tests, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. All experiments were performed in at least 2 independent replicates to ensure reproducibility. The full dataset and analysis scripts are available upon reasonable request to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Quintara Bioscience Inc. for plasmid construction, and DNA/RNA sequencing service for the study. J.L. acknowledges funding from NIH Office of the Director (1DP2GM154019-01) and National Science Foundation CAREER (2238972).

Author contributions

H.W. and R.S. conceived the idea for this project. H.N., K.X. and H.W. designed the experiments and interpreted the data. H.N., K.X., I.M., J.W., S. Y, J.S. and D.L. performed the experiments. J.L. and H.W oversaw the study. H.N. and H.W. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all the other authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The NGS data generated in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession code PRJNA1240319 for Supplementary Fig. S1, and PRJNA1240329 for Supplementary Fig. S4. The processed NGS data are available at Genebank. The NGS data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information file, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S4, respectively. Any other relevant data are available from the authors upon request.

Competing interests

I.M., J.W., J.S., D.L., K.X., R.S. and H.W. are paid employees from Full Circles Therapeutics, R.S. is founder and shareholder of Quintara Bioscience, Inc. Provisional patent “DNA EDITING CONSTRUCTS AND METHODS USING THE SAME” related to this study have been filed by Hao Wu and Richard Shan with Patent Application No. 63/427,370, on November 22, 2022. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jiahe Li, Hao Wu.

Contributor Information

Jiahe Li, Email: jiaheli@umich.edu.

Hao Wu, Email: Howard.wu@fullcirclestx.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-59790-3.

References

- 1.Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science339, 819–823 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doudna, J. A. & Charpentier, E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science346, 1258096 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu, P. D., Lander, E. S. & Zhang, F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell157, 1262–1278 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert, L. A. et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell154, 442–451 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mali, P. et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science339, 823–826 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qi, L. S. et al. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell152, 1173–1183 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilton, I. B. et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat. Biotechnol.33, 510–517 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komor, A. C., Kim, Y. B., Packer, M. S., Zuris, J. A. & Liu, D. R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature533, 420–424 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, X. S. et al. Editing DNA methylation in the Mammalian genome. Cell167, 233–247.e17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strecker, J. et al. RNA-guided DNA insertion with CRISPR-associated transposases. Science365, 48–53 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding, Y. et al. Increasing the homologous recombination efficiency of eukaryotic microorganisms for enhanced genome engineering. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.103, 4313–4324 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth, T. L. et al. Reprogramming human T cell function and specificity with non-viral genome targeting. Nature559, 405–409 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth, T. L. et al. Pooled knockin targeting for genome engineering of cellular immunotherapies. Cell181, 728–744.e21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang, J.-P. et al. Efficient precise knockin with a double cut HDR donor after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated double-stranded DNA cleavage. Genome Biol.18, 35 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mata López, S. et al. Challenges associated with homologous directed repair using CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN to edit the DMD genetic mutation in canine Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One15, e0228072 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishizono, H., Yasuda, R. & Laviv, T. Methodologies and challenges for CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing of the Mammalian brain. Front. Genome Ed.2, 602970 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dever, D. P. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 β-globin gene targeting in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature539, 384–389 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie, K. et al. Efficient non-viral immune cell engineering using circular single-stranded DNA-mediated genomic integration. Nat. Biotechnol. 10.1038/s41587-024-02504-9 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Iyer, S. et al. Efficient homology-directed repair with circular single-stranded DNA donors. CRISPR J.5, 685–701 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao, K. et al. Transcription-coupled donor DNA expression increases homologous recombination for efficient genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res.50, e109 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayavaradhan, R. et al. CRISPR-Cas9 fusion to dominant-negative 53BP1 enhances HDR and inhibits NHEJ specifically at Cas9 target sites. Nat. Commun.10, 2866 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, G., Wang, H., Zhang, X., Wu, Z. & Yang, H. A Cas9–transcription factor fusion protein enhances homology-directed repair efficiency. J. Biological Chem.296, 100525 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Lin-Shiao, E. et al. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated nuclear transport and genomic integration of nanostructured genes in human primary cells. Nucleic Acids Res.50, 1256–1268 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park, J. et al. Enhanced genome editing efficiency of CRISPR PLUS: Cas9 chimeric fusion proteins. Sci. Rep.11, 16199 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rees, H. A., Yeh, W.-H. & Liu, D. R. Development of hRad51–Cas9 nickase fusions that mediate HDR without double-stranded breaks. Nat. Commun.10, 2212 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reint, G. et al. Rapid genome editing by CRISPR-Cas9-POLD3 fusion. eLife10, e75415 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shao, S. et al. Enhancing CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair in mammalian cells by expressing Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad52. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol.92, 43–52 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran, N.-T. et al. Enhancement of precise gene editing by the association of Cas9 with homologous recombination factors. Front. Genet.10, 365 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Aird, E. J., Lovendahl, K. N., St. Martin, A., Harris, R. S. & Gordon, W. R. Increasing Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair efficiency through covalent tethering of DNA repair template. Commun. Biol.1, 1–6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson-Stevermer, J. et al. Assembly of CRISPR ribonucleoproteins with biotinylated oligonucleotides via an RNA aptamer for precise gene editing. Nat. Commun.8, 1711 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghanta, K. S. et al. 5′-Modifications improve potency and efficacy of DNA donors for precision genome editing. eLife10, e72216 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma, M. et al. Efficient generation of mice carrying homozygous double-floxp alleles using the Cas9-Avidin/Biotin-donor DNA system. Cell Res.27, 578–581 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savic, N. et al. Covalent linkage of the DNA repair template to the CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease enhances homology-directed repair. eLife7, e33761 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aiba, W., Amai, T., Ueda, M. & Kuroda, K. Improving precise genome editing using donor DNA/gRNA hybrid duplex generated by complementary bases. Biomolecules12, 1621 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen, D. N. et al. Polymer-stabilized Cas9 nanoparticles and modified repair templates increase genome editing efficiency. Nat. Biotechnol.38, 44–49 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shy, B. R. et al. High-yield genome engineering in primary cells using a hybrid ssDNA repair template and small-molecule cocktails. Nat. Biotechnol.10.1038/s41587-022-01418-8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simone, B. W. et al. Chimeric RNA: DNA donorguide improves HDR in vitro and in vivo. Preprint at 10.1101/2021.05.28.446234 (2021).

- 38.Chen, Z., Yang, H. & Pavletich, N. P. Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA–ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature453, 489–494 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin, Z., Kong, H., Nei, M. & Ma, H. Origins and evolution of the recA/RAD51 gene family: Evidence for ancient gene duplication and endosymbiotic gene transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.103, 10328–10333 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shinohara, A., Ogawa, H. & Ogawa, T. Rad51 protein involved in repair and recombination in S. cerevisiae is a RecA-like protein. Cell69, 457–470 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su, G.-C. et al. Role of the RAD51-SWI5-SFR1 ensemble in homologous recombination. Nucleic Acids Res.44, 6242–6251 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma, L. et al. MiCas9 increases large size gene knock-in rates and reduces undesirable on-target and off-target indel edits. Nat. Commun.11, 6082 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maraboeuf, F., Voloshin, O., Camerini-Otero, R. D. & Takahashi, M. The central aromatic residue in loop L2 of RecA interacts with DNA. Quenching of the fluorescence of a tryptophan reporter inserted in L2 upon binding to DNA. J. Biol. Chem.270, 30927–30932 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugimoto, N. DNA recognition of a 24-mer peptide derived from RecA protein. Pept. Sci.55, 416–424 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sugimoto, N. & Nakano, S. A 24 mer peptide derived from RecA protein can discriminate a single-stranded DNA from a double-stranded DNA. Chem. Commun. 2125–2126, 10.1039/A705575G (1997).

- 46.Voloshin, O. N., Wang, L. & Camerini-Otero, R. D. Homologous DNA pairing promoted by a 20-amino acid peptide derived from RecA. Science272, 868–872 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slade, D., Lindner, A. B., Paul, G. & Radman, M. Recombination and replication in DNA repair of heavily irradiated deinococcus radiodurans. Cell136, 1044–1055 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zahradka, K. et al. Reassembly of shattered chromosomes in Deinococcus radiodurans. Nature443, 569–573 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer, R. R. & Laine, P. S. The single-stranded DNA-binding protein of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev.54, 342–380 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mosberg, J. A., Lajoie, M. J. & Church, G. M. Lambda red recombineering in Escherichia coli occurs through a fully single-stranded intermediate. Genetics186, 791–799 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noirot, P. & Kolodner, R. D. DNA strand invasion promoted by Escherichia coli RecT protein. J. Biol. Chem.273, 12274–12280 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seitz, E. M., Brockman, J. P., Sandler, S. J., Clark, A. J. & Kowalczykowski, S. C. RadA protein is an archaeal RecA protein homolog that catalyzes DNA strand exchange. Genes Dev.12, 1248–1253 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wardell, K. et al. RadB acts in homologous recombination in the archaeon Haloferax volcanii, consistent with a role as recombination mediator. DNA Repair55, 7–16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xh, Z., Ly, T., Xg, W., Qs, H. & Sh, Y. Off-target Effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering. Mol. Therapy. Nucleic Acids4, e264 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Hou, X., Zaks, T., Langer, R. & Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater.6, 1078–1094 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang, L. et al. Circular single-stranded DNA as switchable vector for gene expression in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun.14, 6665 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian, Z. et al. Circular single-stranded DNA as a programmable vector for gene regulation in cell-free protein expression systems. Nat. Commun.15, 4635 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farbiak, L. et al. All-in-one dendrimer-based lipid nanoparticles enable precise HDR-mediated gene editing in vivo. Adv. Mater.33, e2006619 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Musunuru, K. et al. In vivo CRISPR base editing of PCSK9 durably lowers cholesterol in primates. Nature593, 429–434 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qiu, M. et al. Lipid nanoparticle-mediated codelivery of Cas9 mRNA and single-guide RNA achieves liver-specific in vivo genome editing of Angptl3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.118, e2020401118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang, X. et al. Functionalized lipid-like nanoparticles for in vivo mRNA delivery and base editing. Sci. Adv.6, eabc2315 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gillmore, J. D. et al. CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo gene editing for transthyretin amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med.385, 493–502 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clement, K. et al. CRISPResso2 provides accurate and rapid genome editing sequence analysis. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 224–226 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The NGS data generated in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession code PRJNA1240319 for Supplementary Fig. S1, and PRJNA1240329 for Supplementary Fig. S4. The processed NGS data are available at Genebank. The NGS data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information file, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S4, respectively. Any other relevant data are available from the authors upon request.