Abstract

Background

CNS stromal cells, especially fibroblasts and endothelial cells, support leukocyte accumulation through upregulation of adhesion molecules and lymphoid chemokines. While chronically activated fibroblast networks can drive pathogenic immune cell aggregates known as tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS), early stromal cell activation during CNS infection can support anti-viral T cells. However, the cell types and factors driving early stromal cell activation is poorly explored.

Aims

A neurotropic murine coronavirus (mCoV) infection model was used to better characterize signals that promote fibroblast networks supporting accumulation of antiviral lymphocytes. Based on the early appearance of IgD+ B cells with unknown functions during several CNS infections, we probed their potential to activate stromal cells through lymphotoxin β (LTβ), a molecule critical in maintaining fibroblast-networks in lymphoid tissues as well as promoting TLS in autoimmunity and cancers.

Results

Kinetic analysis of stromal cell activation in olfactory bulbs and brains revealed that upregulation of adhesion molecules and lymphoid chemokines Ccl19, Ccl21 and Cxcl13 closely tracked viral replication. Immunohistochemistry revealed that upregulation of the fibroblast marker podoplanin (PDPN) at meningeal and perivascular sites mirrored kinetics of RNA expression. Moreover, both B cells and T cells colocalized to areas of PDPN reactivity, supporting a potential role in regulating stromal cell activation. However, specific depletion of LTβ from B cells using Mb1-creERT2 x Ltβfl/fl mice had no effect on T or B cell recruitment or viral replication. B cell depletion by anti-CD20 antibody also had no adverse effects. Surprisingly, LTβR agonism reduced viral control and parenchymal T cell localization despite increasing stromal cell lymphoid chemokines and PDPN. Additional assessment of direct stromal cell activation by the viral RNA mimic poly I:C showed induction of Pdpn and Ccl19 preceding Ltb.

Conclusions

Neither B cell-derived LTβ or B cells are primary drivers of stromal cell activation networks in the CNS following mCoV infection. Although supplementary agonist mediated LTβR engagement confirmed a role for LTβ in enhancing PDPN and lymphoid chemokine expression, it impeded T cell migration to the CNS parenchyma and viral control. Our data overall indicate that stromal cells can integrate LTβR signals to tune their activation, but that LTβ is not necessarily essential and can even dysregulate protective antiviral T cell functions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12974-025-03491-7.

Introduction

The active participation of stromal cells in immune homeostasis and responses to insults, such as infections, is extensively characterized in lymphoid tissue, but underappreciated in regulating leukocytes at other sites of inflammation. In lymph nodes (LN) a network of heterogeneous stromal cells including fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) orchestrate localization of lymphocytes into distinct compartments. By expressing cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, extracellular matrix components, adhesion molecules, and presenting antigens, FRCs regulate not only homeostatic immune cell trafficking and retention, but also play a key role in restructuring LNs during inflammation [1–3]. Inflammation can stimulate FRC expansion and further upregulate homeostatic lymphoid chemokines CCL19 and CCL21, which recruit CCR7 expressing T cells and dendritic cells, as well as CXCL13, a B cell chemoattractant. Recruited cells in turn can modulate FRC function with respect to adhesion, contractility, and conduit properties. FRCs in LNs are characterized by expression of ER-TR7, the membrane protein podoplanin (PDPN), and an absence of the endothelial cell marker CD31. Interactions between PDPN and CLEC2 expressed on dendritic cells and platelets relax the FRC network to accommodate lymphocyte influx and proliferation. FRC-lymphocyte interactions thereby allow extensive crossregulation within secondary lymphoid tissue. Overall, numerous studies indicate that FRCs have the capacity to respond to various stimuli in a context and anatomical niche specific manner involving sensing by mechano-receptors, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), and cytokine receptors. Inflammatory reactions can be initiated by direct sensing of pathogenic modules or by integrating immune cell-derived signals [4]. Specifically lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) signaling, known to activate and maintain stromal cells in LN, and IFNα/β receptor signaling by FRCs promotes their ability to produce chemokines and present antigen [5, 6].

FRC-like cells also populate non-lymphoid organs including the CNS. In the CNS pial fibroblasts are immunologically quiescent during homeostasis and require activation signals to upregulate chemokines, attachment factors, and cytoskeletal molecules that attract and retain immune cells. Similar to peripheral inflammation, a fibroblastic reticular network is activated to support and guide leukocyte migration and localization in the meninges following inflammatory events [7, 8]. Studies in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of multiple sclerosis (MS) and neurotropic murine (m)CoV infection have revealed the plasticity and key roles of meningeal and perivascular fibroblasts in regulating immune cell recruitment. During EAE associated with chronic inflammation, IL-17 and IL-22 produced by Th17 cells were shown to be directly capable of inducing an FRC like phenotype associated with pathogenic TLS formation [9]. While IL-17 sufficed to remodel stromal cells independent of LTβR, LTβR signaling promoted TLS with more organized B cell accumulation. Meningeal networks supporting lymphocyte niches are also associated with lesion formation in MS [10]. While the EAE studies focused on FRC involvement in pathogenic TLS formation during chronic inflammation, infection with both neurotropic mCoV and Toxoplasma gondii showed rapid formation of a fibroblastic reticular network at the acute phase of infection phase [8, 11, 12]. Following intranasal (IN) mCoV infection increased expression of CCL19 and CCL21 by stromal cells in the olfactory bulb (OB) and other brain regions coincided with robust upregulation of both LTβ and the FRC activation marker PDPN. Importantly, stromal cell-derived CCL19 was required for restimulation of infiltrating CCR7+ CD8 T cells and their control of infectious virus in the parenchyma. Activated CCL21 producing fibroblasts in the pial meninges also provide a scaffold for CCR7+ CD8 T cells to control T. gondii infection [13]. These data thus revealed a vital beneficial role of early fibroblast activation in controlling infections. However, the factors and cells inducing pial meningeal stromal cell activation to support acute anti-microbial immunity in the CNS remain unknown.

The studies herein aimed to identify signals driving early meningeal stromal cell activation during neurotropic mCoV induced encephalomyelitis. Immune cell recruitment and their contribution to viral control and pathology is well characterized in this model [14, 15]; however, the components contributing to the activation of the stromal cell network that supports CD8 T cells, remain undefined. We focused on LTβ as a signaling candidate based on its known function in supporting FRC networks and LN organization throughout development [16–18], homeostasis [19, 20], and inflammation [21–23]. Membrane bound LTβ is a member of the TNF superfamily, which is composed of one LTα and two LTβ subunits [24] to form a heterotrimer and only signals through the LTβR [25]. ILCs [26, 27], B cells [28–30], and T cells [31] express LTβ and signal to fibroblasts in various developmental and inflammatory contexts. However, the initiators of fibroblast activation resulting in lymphoid chemokine and PDPN upregulation in the CNS are poorly explored.

Our results reveal that depletion of LTβ in B cells to eliminate a primary source of LTβ, as well as total B cell depletion, surprisingly played no or minor roles in regulating lymphoid chemokines, fibroblast cell activation genes, T cell recruitment, or viral control. Administration of an LTβR agonist during infection indeed increased acute lymphoid chemokine expression but did not promote T cell accumulation and unexpectedly reduced viral control. Further analysis of innate signaling through PRRs via polyI:C administration revealed that upregulation of Pdpn and Ccl19 may be uncoupled from LTβ. Overall, our results illustrate that chemokine production and fibroblast activation can be highly dynamic and coordinated by multiple signals, but that increasing these signals does not necessarily predict accumulation and anti-viral protective function of T cells.

Results

Kinetics of gene expression associated with stromal cell activation relative to virus replication

Neurotropic mCoV infection activates a fibroblastic reticular network in the pial meninges, which is critical to recruit and imprint CD8+ T cells to control virus in the brain parenchyma [11, 12]. The early recruitment of virus-specific CD8+ T cells was shown to be dependent on CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21, which were predominantly upregulated in blood endothelial cells and perivascular fibroblasts [12]. The lymphoid chemokines CCL19, CCL21, CXCL12, and CXCL13 are all known to be induced by LTβ signaling through the LTβR receptor [32]. Moreover, CXCL13 induction in the CNS is associated with B cell accumulation and formation of TLS during chronic inflammation in non-lymphoid sites, including in the meninges [33]. However, the signals responsible for stromal cell activation including chemokine induction during acute CNS infection remain undefined. We therefore initially assessed the kinetics of viral load relative to expression of genes associated with pial stromal cell activation at the global transcriptional level in brains and OBs from mice infected with the hepato- and neuro-tropic mCoV strain, designated mouse hepatitis virus (MHV)-A59. OB were separated from brains and analyzed as separate tissue as virus preferentially replicates in OB early after intracranial (IC) infection [34] and OB are likely to harbor distinct stromal cell reactivity compared to other brain areas due to their primary entry site of pathogens through the nasal cavity [35, 36]. As makers of fibroblast activation, we chose Pdpn, which is upregulated on perivascular CNS fibroblasts known to exert fibroblastic reticular cell-like functions [12, 37], and Fap, encoding fibroblast activation protein α, a protein expressed by FRCs in LNs [38] and a subset of stromal cells in tumors [39]. Fibroblast stromal cells are a major cell type expressing Ltbr [40, 41]. Lta and Ltb were thus assessed as LTβR activating ligands and Ccl19, Ccl21 and Cxcl13 as LTβR signaling induced chemokines (Fig. 1A). Viral RNA encoding the nucleocapsid (N) protein was detected one day post infection (dpi), peaked between 3–5 dpi and declined thereafter, but was still detectable at 21 dpi. Pdpn expression in the brain was already increased significantly by 3 dpi, remained high at 5 dpi, but dropped to baseline levels by 14 dpi. However, the fibroblast activation protein Fap was not transcriptionally altered throughout CNS infection, suggesting that Fap upregulation may require additional activation or involve distinct fibroblast precursors, as observed in cancer associated fibroblasts [39]. Ltb was upregulated in conjunction with Pdpn by 3 dpi, peaked at 7 dpi, and remained elevated out to 21 dpi. By contrast, whereas Ltb transcripts were increased by almost 100-fold, Lta transcripts were only increased 3–fourfold and declined to baseline by 21dpi, suggesting LTα may be the limiting component in LTα1β2 heterotrimer surface expression. Importantly, although LTβR expression is constitutive on most cells, transcription of LTβR (Tnfrsf3) was also moderately elevated at 3 dpi reaching statistically significant differences at 5 dpi relative to basal levels. Another tumor necrosis family member, Tnf, known to induce CCL19 and CCL21 in fibroblasts in vitro [42] was already significantly upregulated by 1 dpi and remained elevated through 21dpi. The stromal cell produced Ccl19 was not significantly upregulated until 5 dpi, while Ccl21 remained stable at baseline levels throughout infection. By contrast, the CXCR5 ligand Cxcl13 was already significantly upregulated at 3 dpi, declined by 14 dpi, but remained elevated until 21 dpi. While CXCL13 has been shown to be expressed by microglia [43, 44], expression in stromal cells in the pial meninges remains to be documented. Similar overall trends were observed in the OB (Supplemental Fig. 1 A).

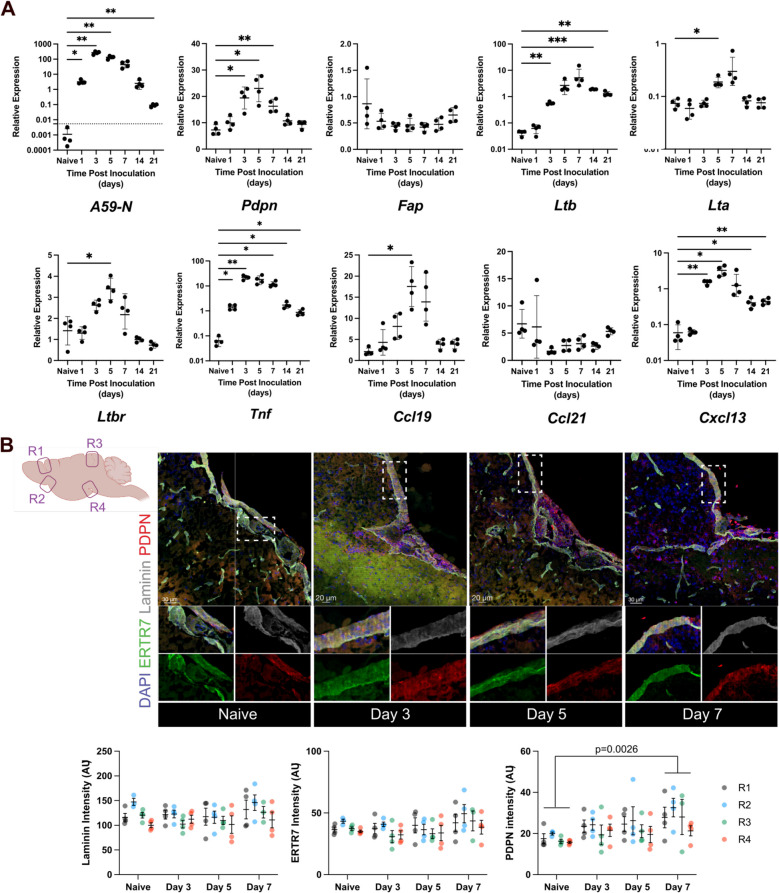

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of increases in stromal cell activation genes, chemokines, and adhesion molecules after MHV infection. A RT-qPCR analysis of inflammatory and chemokine/stromal gene expression relative to Gapdh in brains excluding OB following infection of wt C57BL/6 mice infected IC with MHV-A59. Filled circles represent individual mice and crossbars represent mean ± SD with 4 mice per group. Statistical differences between naïve and infected timepoints were measured by one-way ANOVA. B Brain sections from naïve or IC MHV-A59 infected mice were stained for ER-TR7 (green), laminin (grey), and PDPN (red) expression and DAPI at the indicated timepoints with analysis focused on the selected regions (R1, R2, R3, R4) in the schematic. Representative IHC images showing merged staining are shown for the indicated timepoints (scale bar = 20 or 30 μm as indicated). Inserts show individual stains of ER-TR7 + pial meninges. Bar graphs show quantification of ER-TR7, laminin and PDPN intensities depicted as arbitrary units (AU). Individual circles represent one image in the indicated anatomical regions per mouse with 4 mice per group. AU averages are plotted ± SD. Statistical differences were tesed by Two-way ANOVA

To confirm infection induced PDPN protein expression at anatomical sites consistent with perivascular and pial meningeal localization, brain sections were stained for PDPN, laminin to visualize basement membranes and ER-TR7 to visualize fibroblasts (Fig. 1B). While Laminin and ER-TR7 signal intensity was not significantly altered by infection, PDPN staining was scant in uninfected brains but increased during days 3 and 5 pi with a significant increase in staining intensity at 7 dpi, consistent with transcriptional results. Overall, these data showed that early fibroblast activation and chemokine expression coincides with increased Ltb and infiltrating leukocytes.

Early infiltrating B and T cells are candidates for fibroblast activation

LTβ mediated regulation of stromal cell activity in the periphery [23, 30, 45, 46] combined with the coincident increase in Ltb expression and upregulation of stromal cell activation markers in the CNS, supported LTβ as a prime candidate driving fibroblast network activation. LTβ is predominantly expressed by B cells, activated T cells, and NK cells in the periphery [26, 30, 47, 48]. We therefore queried a published single cell (sc) RNA seq data base of CD45+ cells purified from the CNS of mice infected with an attenuated glia tropic variant of the MHV-JHM strain for cells expressing LTβ [49]. The data includes cells from brains across 3 and 7 dpi, and from spinal cords at 21 dpi. CD4 and CD8 T cells as well as B cells were the predominant cell types expressing LTβ (Fig. 2A). NK cells emerging early and plasma cells, only accumulating in the CNS after 14 dpi, were minor LTβ transcribing populations.

Fig. 2.

Lymphocytes as candidates expressing Ltb and their localization proximal to meningeal sites of podoplanin reactivity. A Analysis of Ltb expression in various cell types using a published transcriptomics data set of CD45+ cells in the CNS of MHV-JHMV infected mice; the data set is from the entire landscape of cells across 3, 7(brains), and 21 dpi (spinal cords). Data show Ltb transcripts as violin plots for depicted cell populations. B Expression of Ifng and Ms4a1 as markers of T and NK cells, and B cells, respectively in the brain throughout the course of infection with MHV-A59 after IC infection. Average and SD deviation of data from 4 mice per timepoint are shown. Statistical differences between naïve and infected timepoints were measured by one-way ANOVA. C Immunofluorescence staining of brains from MHV-A59 infected mice at 3 dpi stained for PDPN (red), laminin (yellow), IgD or CD3 (white), and DAPI (blue). Single stains are shown to the left and merged stains shown enlarged (scale bar = 50 um). Images taken from the olfactory bulb pia at 3 dpi

To assess how the kinetics of Ltb transcripts align with lymphocyte recruitment, we monitored Ifng expression as a correlate of activated NK and T cells and Ms4a1 expression as a correlate of B cells. Ifng and Ms4a1 were both upregulated at 3 dpi (Fig. 2B), temporally similar to the increase in Ltb expression (Fig. 1A). We further evaluated whether sites of PDPN upregulation are spatially associated with infiltrating lymphocytes using immunohistochemistry (IHC). Brains from acutely infected mice were analyzed for expression of PDPN in combination with IgD to mark early infiltrating B cells or with CD3 to mark T cells (Fig. 2C). Regions of PDPN reactivity revealed both proximal IgD+ and CD3+ cells at 3 dpi. Histological analysis thus indicated potential interactions between IgD+ and/or CD3+ cells and stromal cells to initiate their activation and chemokine expression.

LTβ abrogation in B cells selectively impairs CCL21 expression in the brain

LTβ expression profiles as well as localization of T and B cells at sites of meningeal and perivascular PDPN+ reactivity supported either lymphocyte population as a candidate to activate stromal cells via LTβR signaling following MHV infection. Specifically B cells have been associated with expansion/activation of fibroblastic reticular cells in the draining LN following peripheral HSV-1 infection [50], as well as homeostatic maintenance of stromal cell networks [30]. Early CNS infiltrating B cells evident in multiple models of neuroinflammation [51–54] may thus function to promote fibroblast activation. We therefore tested if B cell-derived LTβ induces lymphoid chemokines in CNS stromal cells. Inducible ablation of LTβ specifically in B cells was achieved by crossing Ltβfl/fl mice [30] with Mb1-creERT2 mice [55], which express tamoxifen inducible cre under the B cell-specific Mb1 promoter. This mouse line circumvents developmental or homeostatic abnormalities in secondary lymphoid organs observed in mice with constitutive LTβ deletion [26, 30, 56]. Use of these mice also minimizes potential abnormalities affecting the development of stromal cell populations in nonimmune organs such as the CNS. Optimal recombination efficiency was initially tested in Mb1-creERT2 mice crossed to ROSA26lstopl-tdtomato mice. The specificity and dynamics of cre recombination under homeostatic conditions were monitored by emergence of tdtomato+ B cells in circulation as well as LN, dura and skull bone marrow following tamoxifen administration every other day for 7 days (Supplemental Fig. 2). Analysis of blood derived B cells revealed a recombination efficiency of ~ 70% at day 5 increasing to over 90% by day 7 after the first dose (Supplemental Fig. 2 A). Importantly, over 90% of recombination occurred in CD19+ B cells confirming high specificity (Supplemental Fig. 2B). Recombination at day 7 was equally high in LNs and skull bone marrow, but slightly less efficient in the dura reaching 70% in CD19+ B cells (Supplemental Fig. 2 C).

We next administered Tamoxifen to Mb1-creERT2±Ltβfl/fl and Mb1-creERT2±Ltβwt/wt control mice starting 3 days prior to infection. This approach allowed recombination to precede B cell infiltration into the CNS, while minimizing homeostatic effects of B cell-derived LTβ abrogation (Fig. 3A). Infected mice were analyzed at 5 dpi when Ccl19 and Pdpn transcription peaked in brains of wildtype (wt) mice (see Fig. 1). Purified B cells from the spleen confirmed reduced Ltb expression in Mb1-creERT2±Ltβfl/fl compared to Mb1-creERT2±Ltβwt/wt controls (Fig. 3B). However, overall expression of Ltb and Lta was not affected in the brain (Fig. 3C) or OB (Supplemental Fig. 3 A) suggesting that B cells are either not the primary source of LTβ or that other infiltrating cells compensate during acute infection. Expression of Pdpn and Ccl19 was also not altered between groups in either the brain (Fig. 3C) or OB (Supplemental Fig. 3 A). Surprisingly, Ccl21 expression in B cell LTβ deleted mice was significantly lower in both brains (Fig. 3C) and OBs (Supplemental Fig. 3 A), although infection did not alter Ccl21 expression in the CNS of wt mice (see Fig. 1). CCL21 protein in brain supernatants of infected B cell LTβ deleted mice was also decreased (Fig. 3D) supporting gene expression results. We therefore controlled for the possibility that reduced CCL21 levels may be attributed to a homeostatic effect of B cell LTβ deletion. However, LTβ deletion induced in naïve Mb1creERT2±Ltβfl/fl or cre control mice did not alter Ccl21 transcripts or CCL21 protein in brain supernatants at 8 days post the first tamoxifen administration (Supplemental Fig. 3B). LTβ mRNA levels in the naïve brains also remained similar between groups. These results indicated that reduced Ccl21 expression observed during infection could not be attributed to cre mediated LTβ deletion during homeostasis but was linked to an infection induced loss of signal sustaining CCL21. A possible explanation may reside in an altered cervical LN environment imposed by infection in the absence of B cell LTβ, which feeds back to the CNS based on communication between these compartments.

Fig. 3.

LTβ abrogation in B cells does not reduce Pdpn but selectively impairs CCL21 expression in the brain. A Mb1cre±LTβfl/fl or control mice were injected with tamoxifen (days −3, −1, and 1 post infection) to induce LTβ deletion and infected IC with MHV-A59 (day 0). Brains excluding OB and spleen were collected at 5 dpi. B B cells from spleens were purified by negative selection to assess loss of Ltb expression by RT-qPCR shown as relative to Mb1 expression. C Brain derived RNA was analyzed for expression of indicated genes by qPCR and data normalized to Gapdh expression. D CCL21 protein in brain supernatants at 5 dpi measured by ELISA. E Brains were processed for flow cytometry to measure T and B cell recruitment shown as percent of infiltrating CD45 + cells or total cell number (F). All plots represent average ± SD and statistical differences were tested by unpaired two tailed T-test (*—p < 0.05, **—p < 0.005, ***—p < 0.0005, ****—p < 0.0001)

To assess whether the depletion of LTβ in B cells affected B cell or T cell recruitment to the CNS, we monitored changes in CD45hi infiltrating leukocytes by flow cytometric analysis. Neither the percentage of CD19+ B cells within the CNS infiltrating leukocyte population nor total B cell numbers were affected in the brain (Fig. 3E and F), confirming that intrinsic lack of LTβ does not affect trafficking. Surprisingly, accumulation of TCRb+ and CD8+ T cells was also not affected, distinct from impaired recruitment of CD8+ T cells in CCR7 knockout studies [12]. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells were even slightly elevated in brains of B cell-LTβ deficient compared to control mice, suggesting increased egress from the LNs. Similar results were noted in OB (Supplemental Fig. 3C, D). However, consistent with only minor changes in T cell recruitment, viral RNA load was similar in brains of both mouse groups (Fig. 3C), and only slightly higher in OBs of B cell-LTβ deficient mice at 5 dpi (Supplemental Fig. 3 A). Overall, selective LTβ abrogation in B cells resulted in diminished CCL21, but without impairing T cell recruitment, and only slightly diminished viral control in OB.

B cells are redundant for initial CNS fibroblast activation or lymphoid chemokine responses

To further test an LTβ independent role of early infiltrating B cells in the production of lymphoid chemokines and upregulation of fibroblast activation genes we performed antibody-mediated B cell depletion. Anti-CD20 antibody [57] or isotype control was administered via intraperitoneal (IP) injection 3 days prior to and again the day following infection. B cell depletion was confirmed in the blood on the day of infection by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A) and again at 5 dpi in cervical LN, OB, skull bone marrow, dura (Fig. 4B) and brain (Fig. 4C). However, despite efficient B cell depletion, the percentages of CD11b+ myeloid cells and T cells within brain infiltrating leukocytes were not altered in B cell depleted compared to isotype treated mice (Fig. 4C). Baseline Ms4a1 transcripts in the brain of B cell depleted infected mice further confirmed the absence of virus induced B cell recruitment. Expression of Pdpn, Ccl19, Ccl21, and Ltb in brains was also not significantly different between mouse groups (Fig. 4D). B cells can also participate in modulating the immune response by producing molecules such as GM-CSF, TNF, or IL-6 [58]. However, GM-CSF, TNF, or IL-6 gene expression in brains of B cell depleted was similar to control mice, suggesting that B cells do not contribute significantly to early inflammatory cytokine expression upon MHV infection (Fig. 4D). Additionally, viral control at 5 dpi was unaffected in B cell depleted mice supporting that early activated B cells are dispensable for effective control of acute CNS infection.

Fig. 4.

B cell depletion does not alter virus induced upregulation of stromal cell activation markers, inflammatory genes, or lymphocyte recruitment. Mice were B cell depleted using anti-CD20 on days −3 and 1. MHV-A59 IC infection was performed on day 0 with 2,000 PFU. A B cell depletion was measured in the blood by flow cytometry on the day of infection. B Tissues as indicated were collected at 5 dpi and analyzed for B cell depletion using flow cytometry and the B cell marker CD19. C Brains from B cell depleted and control mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for alterations in CD19+ B cells, CD11b+ myeloid cells, TCRb+ T cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Statistical differences were measured using the Mann–Whitney test (*-p < 0.05, **-p < 0.005, ***-p < 0.0005). D RT-qPCR analysis of brain derived mRNA for expression of indicated genes. Plots indicate value for each individual animal with lines and error bars indicating average and SD, respectively. E B cells, T cells, NK cells and macrophages isolated by FACS from control and anti-CD20 mAb treated infected mice and analyzed for Ltb transcripts and Ifnγ transcripts by RT-qPCR. Circles represent expression in cells pooled from 2 brains each for FACS purification. Statistical differences were tested with two-way ANOVA for Ltb and one-way ANOVA for Ifng (*** p < 0.001, ** < 0.005, and < 0.05)

To assess which cell types express Ltb in brains of B cell depleted mice, we used FACS to isolate B cells, T cells, NK cells and macrophages from brains of anti-CD20 and control mice at 5 dpi. B cells expressed the highest levels of Ltb in controls, while T cells and NK cells showed lower expression relative to B cells (Fig. 4E). Negligeable Ltb detection in macrophages supported lymphocytes as primary LTβ producers. Importantly, B cell depletion did not alter Ltb levels in brain derived T cells and NK cells at the population level, making them likely candidates engaging LTβR in B cell depleted mice. Additional analysis of sorted cells from B cell sufficient mice for Ifng expression confirmed T cells and NK cells as sources for anti-viral IFNγ (Fig. 4E).

Taken together the results above indicate that neither LTβ on B cells nor B cells themselves significantly affect stromal cell activation, accumulation of T cells, or antiviral activity. The discrepancy between infection mediated loss of Ccl21 transcripts in brains of B cell-LTβ deficient and B cell depleted mice remains unclear but may be due to more severe anatomical lymphoid tissue disruption by B cell depletion resulting in influx of other cell types filling the void and maintaining CCL21 homeostasis.

An impediment of IC MHV infection is the overlap between the rapid innate response and infiltration of lymphocytes making it difficult to tease out temporal correlations. We therefore administered virus IN to elicit a more restrained viral spread and temporally drawn-out immune response. The same immune gene expression patterns relative to viral replication were monitored during the acute response as in Fig. 1. We focused on the OB as the initial site of viral replication following IN virus administration [12]. Distinct from IC virus administration, induction of genes associated with stromal cell activation was overall delayed and revealed better temporal segregation (Fig. 5). Virus replication as indicated by detection of increased viral RNA was evident by 3 dpi and was overall higher by two orders of magnitude compared to IC infection (see Supplemental Fig. 1). Pdpn, Ltb, Ltbr and Ccl19 upregulation was not observed until 5 dpi. Fap was also increased at 5 dpi, distinct from no evident changes following IC infection. Further distinct from IC infection, Ccl21 upregulation was evident at 1and 3 dpi and a significant increase at 7 dpi suggested a biphasic response. Tnf was not elevated until 3 dpi but preceded the increase in stromal cell markers. Most importantly however, Ms4a1and Ighd, transcripts marking B cells, were not significantly elevated until 7 dpi. These results showed a clear delay in B cell infiltration relative to LTβ and lymphoid chemokine expression and thus provided an additional line of evidence that B cells do not contribute to early stromal cell activation. The differing pattern and kinetics of stromal cell marker expression following IN versus IC administration likely reflects higher viral load in the OB following IN infection.

Fig. 5.

Upregulation of stromal cell activation genes precedes B cell infiltration after intranasal infection. Mice were infected with MHV-A59 IN with 50,000 PFU and olfactory bulbs were harvested 1, 3, 5, and 7 dpi. Gene expression of indicated genes, including viral N gene, stromal cell genes Pdpn, Fap, Ccl19, Ccl21, Ltbr, stromal cell activating Ltb, as well as B cell markers Ms4a1 and Ighd, relative to Gapdh expression is shown as mean of each group ± SD. Statistical significance between naïve and various timepoints determined by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

LTβR agonism promotes stromal cell activation but diminishes viral control

As LTβ and lymphoid chemokines were jointly upregulated independent of B cells, we further probed if promoting LTβR signaling is beneficial for stromal cell activation, lymphocyte recruitment and anti-viral activity. LTβ is known to promote fibroblast functions in peripheral tissues and chronic CNS inflammation [9]. Mice received a LTβR agonist or isotype control antibody IP concomitant with MHV IC infection and again at 2 and 4 dpi. CNS tissue was harvested at 4 and 6 dpi (Fig. 6A). Agonist treatment indeed significantly increased Pdpn and Ccl19 in brains by 6 dpi. Ccl21 upregulation was already evident at 4 dpi (Fig. 6B). Although a similar trend was observed in OB, only Ccl19 upregulation reached significance at both 4 and 6 dpi. LTβR agonism did not affect Cxcl13 expression in the brain, it was significantly upregulated in OB. To assess whether elevated stromal cell activation and chemokine expression actually increased T cell accumulation we monitored changes in Ccr7 expression, which is expressed by CNS T cells as well as DCs [49, 59, 60]. Surprisingly, agonist treated mice showed a reduction in Ccr7 expression in the brain and a similar trend in the OB (Fig. 6B), suggesting downregulation at the transcriptional level and/or dysregulation of CCR7+ DC or T cell migration. Furthermore, viral RNA levels were elevated as early as day 4 and even further increased by day 6 pi, showing impaired viral control in agonist treated mice. By contrast, viral RNA levels in cervical LN (Supplemental Fig. 4 A) and OB (Fig. 6B) were similar and declined from 4 to 6 dpi. These results suggested impaired rather than enhanced T cell recruitment and/or anti-viral effector function specifically in the brain. To test whether LTβR agonist affected T cells in the cervical LNs, we controlled for potential upregulation of Ccl19 and Ccl21 in draining cervical LNs, which may affect trafficking of CCR7+ cells [61]. However, neither Ccl19, Ccl21, Pdpn, Cxcl13, nor Ccr7 RNA was altered (Supplemental Fig. 4 A). We also tested for altered retention and activation of lymphocytes in cervical LNs at 6 dpi in agonist treated and control groups (Supplemental Fig. 4B). Overall LN cellularity and the proportion of CD4 T cells were not altered. However, the relative proportion of CD19+ B cells was increased, while the relative proportion of CD8+ T cells was decreased in agonist treated LNs. Furthermore, while the numbers of total CD44+ as well as CD44+CD62L− CD4 and CD8 T cells remained similar, the relative percentage of CD44+ and CD44+CD62L− cells were elevated in both the CD4 and CD8 T cell populations, indicating an overall increased activation phenotype.

Fig. 6.

LTβR agonism promotes lymphoid chemokine responses during MHV infection but impairs virus control. A Mice were infected IC with MHV-A59 2,000 PFU on day 0. 100ug LtBR agonist antibody or isotype control antibody was injected IP on 0, 2, and 4 dpi. B OBs and the rest of the brain was harvested on 4 and 6 dpi and RNA analyzed by RT qPCR for altered expression of the indicated genes. Mean gene expression is plotted with error bars indicating standard deviation. Statistical differences were assessed by two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák test for multiple comparisons (*-p < 0.05, **-p < 0.005, ***-p < 0.0005, ****-p < 0.0001). C OBs and brains (without OB) were analyzed by flow cytometry for alterations in infiltrating CD45hi cells and relative percentages of CD19+ B cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells, as well as the relative percentage of CD44+ CD62L− effector cells within the CD4 and CD8 T cell subset. Statistical differences were measured by unpaired t-test (*-p < 0.05)

A potential defect in T cell recruitment to the CNS was also analyzed by flow cytometry in the same group of mice in which the LN were analyzed (Fig. 6C). Total CD45hi infiltrating cells were similar in both the OB and brains of agonist treated and control groups. While the proportion of CD19+ B cells was slightly elevated in the agonist treated CNS, the percentage of CD4 and CD8 T cells were not significantly different. Furthermore, the vast majority of T cells had an activated CD44+CD62L− effector phenotype in both groups. These data indicated that there was no significant defect in T cell recruitment to the CNS due to activation or retention of lymphocytes in the draining LN.

To assess potentially altered localization of T cells at meningeal and parenchymal sites due to enhanced PDPN expression we stained for laminin to visualize basement membrane, CD3e for T cells, and CD45 for infiltrating leukocytes at 6 dpi. Analysis was focused on 3 distinct anatomical regions with readily discernible pial meninges evident by the continuous pattern of laminin reactivity (Fig. 7A, B). The overall density of perivascular cuffs was similar between the treatment groups (Fig. 7C). Assessment of CD3+ T cell numbers in the pia revealed no significant differences. By contrast, T cell numbers were significantly reduced in the parenchyma, especially in the R2 region in agonist-treated compared to control mice (Fig. 7D). Total CD45+ cells also accumulated to similar numbers in the pia in both groups, but their infiltration into adjacent parenchymal areas was reduced in LTβR agonist treated mice (Fig. 7E). These results supported that LTβ can directly promote stromal cell activation in the brain following MHV infection. However, while increased CCR7-ligand expression did not alter overall T cell recruitment, it was associated with reduced T cell localization to the parenchyma and thereby impaired viral control in the CNS. This unanticipated result of LTβR agonism may be attributed to impaired local T cell function as a result of altered CCR7+ DC migration and imprinting of effector function.

Fig. 7.

LtBR agonist treated mice exhibit reduced T cell infiltration into the brain parenchyma. Mice were infected IC with MHV-A59 2,000 PFU on day 0 and injected with 100ug LtBR agonist antibody or isotype control antibody on 0, 2, and 4 dpi as depicted in Fig. 6A. A Brain sections at the indicated regions (R1, R2, R3) were stained for laminin (green), CD45 (red), and CD3 (white) at 6 dpi. B Representative images showing staining for CD3+ cells residing in areas aligning with meningeal and perivascular laminin and parenchymal areas. (scale bar = 50 um). C Quantification of density of perivascular cuffs at the representative regions. D Quantification of CD3+ area of pia marked by contiguous laminin staining and of parenchymal CD3+ cell numbers in adjacent areas in the indicated regions. E Quantification of CD45+ area of pia marked by contiguous laminin staining and of parenchymal CD45+ cell numbers in adjacent areas in the indicated regions. Individual circles represent one image in the indicated anatomical regions per mouse with 4 mice per group. Mean cell area and counts from individual mice are plotted ± SD. Statistical differences were tested with two-way ANOVA and exact p values are shown for measurements between treatment groups

Markers of stromal cell activation can be directly induced by innate signaling through pattern recognition receptors

Based on our finding of B cell independent stromal cell responses, we probed the possibility of a direct mechanism of activation through innate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Although chemokine producing fibroblasts are not targets of MHV infection [12], we tested the potential for activation of stromal cell by IC administration of Poly I:C (Fig. 8), a double stranded RNA mimic that engages innate sensors. Poly I:C initiated a dramatic immune response resulting in upregulation of Pdpn and Ltbr by 6 h post injection followed by Ccl19 upregulation after 12 h. However, upregulation of Ltb was delayed until 48 h post inoculation. Robust upregulation of Ccl19 and Pdpn as markers of perivascular fibroblast activation thus clearly preceded Ltb increases and supported Ltb independent activation. Intriguingly, Ccl21 was slightly but significantly downregulated at 12 and 48 h. Expression of B cell markers was not significantly increased until 96 h post inoculation, yet a slight decrease at 12 h correlated with the decline in Ccl21. PBS inoculation did not result in increased gene expression in the brains of treated mice during the first 12 h suggesting the inoculation itself was not a contributing factor (Supplemental Fig. 5). Overall, these data reveal a potential contribution of innate double stranded RNA signaling pathways in initially activating stromal cell networks independent of LTβ, with an additional LTβ component regulating immunological niches to support antiviral immune responses in the parenchyma.

Fig. 8.

PRR stimulation can uncouple Pdpn and Ccl19 upregulation from Ltb upregulation. Mice were injected with poly IC (200ug) via IC administration and brains harvested at the indicated times post injection. RNA was isolated from brains a processed for RT-qPCR. Values are relative to Gapdh. Means are plotted with error bars representing ± SD. Statistical differences were assessed by two-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák test for multiple comparisons (*-p < 0.05, **-p < 0.005, ***-p < 0.0005, ****-p < 0.0001)

Discussion

Formation of reticular networks in the meninges and perivascular spaces has received considerable attention in setting up a niche for leukocyte accumulation in the CNS during inflammatory events [7, 9, 11]. While the fibroblast cells supporting these networks are present during homeostatic conditions, they require activation to produce lymphoid chemokines, cytokines, adhesion molecules, and extracellular matrix (ECM) to recruit and cluster immune cells responding to insults. Importantly, these networks can be pathogenic in sustaining autoimmunity [10] or beneficial to control infection [62]. However, how individual cells or molecular signals contribute to initial formation, resolution, or maintenance of the activated network remains understudied. We therefore built on information available from the MHV model to characterize early signals promoting upregulation of lymphoid chemokines and PDPN. Our focus was on LTβ and B cells, both known contributors to the function of fibroblastic reticular networks in LNs. Following infection, RNA expression analysis revealed virus replication precedes transcriptional upregulation of fibroblast activation genes, but the overall kinetics of LTα/β and lymphoid chemokines followed those of viral replication. Notably, return of Pdpn and Ccl19 to baseline levels by 14 dpi indicated a transient nature of an activated stromal cell network, despite ongoing recruitment of lymphocytes and persistence of viral RNA [63, 64]. These findings are also consistent with the inability to detect TLS in the CNS of mCoV persistently infected mice [51]. As chronic fibroblast responses supporting TLS in the CNS are linked to IL-17, IL-22 and LTβ in EAE [9, 65], the disparate findings may reside in the paucity of Th17 cells induced by mCoV infection [66].

We initially assessed whether B cell-specific LTβ deletion affects stromal cell activation based on the established interaction of LTβ expressing B cells with LTβR expressing fibroblasts. Moreover, the early accumulation of IgD+ B cells in the CNS during infection and autoimmune models [52, 67–69], supported a potentially common role in stromal cell activation. However, the only notable effect of B cell-specific LTβ deletion was a decrease in CCL21 associated with an increase in CD4+ but no changes in CD8+ T cells. These results were unexpected based on a previous report demonstrating reduced CD8+ T cell recruitment to the CNS upon abrogation of CCR7 ligands or CCR7 on T cells; CD4+ T cell recruitment was not affected by ablation of CCL19-expressing stromal cells [12]. However, our results agree with an ischemic stroke study indicating early B cells are dispensable to the pathophysiology [70]. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with the notion that CCL19 is sufficient to recruit CD8 T cells that exert effective antiviral function in the parenchyma. B cell depletion just prior to infection further supported a minor if any contribution of LTβ-dependent or independent innate functions of B cells in promoting meningeal or perivascular fibroblast activation. Importantly, T cell recruitment was not impaired. These results are consistent with effective T cell mediated control of mCoV replication throughout acute infection in B cell deficient mice, although control of virus is lost after 2 weeks-despite retention of T cells in the CNS [71]. Although follow up studies in μMT mice revealed virus-specific T cells in the CNS and periphery were reduced, this was attributed to disorganized LN structure and CD4+ T cell defects [72], which may not be immediately affected by anti-CD20 treatment.

While our results support that B cells play a limited role in regulating acute CNS lymphoid chemokine responses, it is interesting to note that the loss of CCL21 and diminished viral control in the OB evident in the CNS of mice with LTβ-deficient B cells was not apparent in B cell depleted mice, which revealed no change in chemokine expression, lymphocyte recruitment, or viral control. Rapid B cell depletion may create a vacant immunological niche which could be filled by other lymphocytes. Such compensation can be performed by NK cells as observed in tumor models using B cell deficient mice [73]. Additionally, differing results between techniques may be indicative of a B cell subset that expresses Mb1 but not CD20, or off target effects of Mb1 driven cre. Nevertheless, both approaches in addition to drawn out responses following IN virus infection, revealed that the source of brain LTβ during viral infection does not primarily comprise B cells, and that ILCs, NK cells, or activated T cells may individually or in concert regulate stromal cell activity. This issue and the effects mediated by peripheral or local dural immune modulation clearly warrants future investigation.

An intriguing result of our studies was that upregulation of PDPN and lymphoid chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 in the CNS by LTβR agonism during infection resulted in impaired viral control within the CNS, but not cervical LNs, counterintuitive to results demonstrating that loss of either CCL19 in CNS stromal cells or of CCR7 on T cells abrogates essential CD8 T cell recruitment and anti-viral function in the CNS [12]. Replication of neurotropic mCoV is controlled by both IFNγ and CD8 T cell mediated cytolytic activity [14]. Coincidentally decreased Ccr7 expression indicated impaired early recruitment of CCR7+ lymphocytes and/or DC or downregulation of CCR7 transcription. While flow cytometric analysis did not support a decrease in T cell recruitment, IHC analysis focusing on vessel, pial and parenchymal distribution of T cells revealed overall similar numbers in the pia, but significantly lower numbers in the parenchyma of agonist treated mice. LTβR agonist treatment further increased the fraction of activated T cells, but not overall LN cellularity, consistent with effective viral control in LN and potentially dysregulated egress of T cells into circulation. B cells migrating to the CNS early in response to mCoV infection also express CCR7 [52] and their recruitment was increased, supporting responsiveness to elevated CCL19 and CCL21 in the CNS of agonist treated mice distinct from T cells. However, IgD+ B cells are retained in the pial and perivascular space [51] and do not exert direct antiviral activities. These results are consistent with the notion that increased PDPN promotes a reticular network retaining lymphocytes in a pial niche, thereby dysregulating egress to the parenchyma. In addition to CNS infiltrating B cells, other models revealed NK cells and CNS resident astrocytes express CCR7 [74–77], potentially contributing indirectly to impaired viral control. We further cannot exclude dysregulation of DC migration from the dural meninges to draining cervical LN or from LN to perivascular locations in the CNS, which may affect local T cell reactivation to optimize antiviral effector activity. It has also been shown that IC administered DC expressing CCR7 egress from the brain while CCR7 deficient DC are retained during EAE, suggesting there may also be a premature egress of CCR7+ cells [60].

Lastly, we did not address a contribution of LTβR agonist on events in the dural meninges, which is a hub for numerous leukocytes potentially affected by LTβR activation. A more thorough investigation of events in the dura and known interplay of lymphatic drainage from the dura to cervical LN and consequential events on lymphocyte activation and migration to the CNS is thus warranted to better interpret the mechanisms underlying impaired viral control in the face of a more activated stromal niche.

Our results from poly I:C administration further indicate potential participation of LTβ independent signaling in stromal cell activation. Other immune cells such as macrophages and microglia, e.g. via TNF may further drive chemokine responses in CNS stromal cells. Specifically, TNF from microglia or border associated macrophages might contribute to initial activation even prior to monocyte-derived macrophage infiltration.

Overall, our results suggest that different contexts or inflammatory stimuli drive distinct pathways of stromal cell activation as evidenced by the segregation of Pdpn upregulation from that of lymphoid chemokines CCL19 and CCL21. Importantly, B cells or B cell-derived LTβ are redundant in activation fibroblastic networks, unlike their essential functions in LNs. Lastly, supplemental agonist mediated activation of pial stromal cells through LTβR impairs, rather than promotes, viral control highlighting the need to further explore the connection between the dural meninges, cervical LN, and the brain in improving anti-microbial immunity. Continued pursuit of the mechanisms driving or suppressing stromal cell activation may further prove beneficial for abrogation or establishing ectopic follicles therapeutically. In summary, our work supports tight orchestration of signals to appropriately tune stromal cell responses and immune cell functions to effectively control CNS viral infection.

Methods

Mice

The following strains were used in this study: C57Bl/6J (The Jackson Laboratory, stock 000664), B6.C-Cd79atm3(cre/ERT2)Reth/EhobJ [55] (The Jackson Laboratory, stock 033026), Myd88−/− mice [B6.129P2(SJL)-Myd88tm1Defr/J (The Jackson Laboratory, stock 008888), Ltβfl/fl 30, and B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG−tdTomato)Hze/J (The Jackson Laboratory, stock 007914) a gift from Dr. Jessica Williams (Cleveland Clinic, Lerner Research Institute). Animals were purchased (C57Bl/6J) or bred in house (all others) and maintained in specific pathogen free conditions in the Cleveland Clinic Biological Resources Unit.

Infections and poly I:C administration

Infections were done in both sexes of mice between 6–8 weeks old using A59-gp33-GFP or A59 infectious clone both kindly provided by Dr. Volker Thiel (University of Bern) [78]. For IC infections 2,000 PFU were injected in the right hemisphere as previously described [63]. Intranasal infection was performed on ketamine/xylazine anesthetized mice by applying 10μL to each naris spaced 5 min apart to avoid aspiration for a total inoculum of 50,000 PFU per mouse. In some experiments, the double stranded RNA mimic poly I:C (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; high molecular weight) was injected intracerebrally into 6‐ to 7‐week‐old C57BL/6 mice at a concentration of 200 μg in 30 μL endotoxin‐free PBS.

Antibody administration

Mice were B cell depleted by IP injection of 25 μg anti-CD20 antibody clone MB20-11 [57] (Bio X Cell) or IgG2c isotype control antibody clone DV5-1 (Bio X Cell) 3 days before and 1 day after infection. LTβR agonism was performed by IP injecting 100 μg anti-LTβR antibody clone 4H8 with agonist activity [32, 79], a gift from Dr. Carl Ware. Control mice were injected with rat IgG2a isotype control (Bio X Cell) every other day starting on the day of infection.

Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen (MilliporeSigma) was resuspended in corn oil at a concentration of 20 mg/mL by mixing in a hybridization chamber overnight at 37 °C and stored at 4 °C until use (< 1 week). Mice were administered 2 mg by intraperitoneal injection every second day.

Tissue collection and flow cytometry

Mice were perfused with PBS prior to removal of brains, spleens, and superficial cervical LNs. Olfactory bulbs were removed from brains and processed separately from the rest of the brain. All tissues were either placed in OCT and flash frozen for immunofluorescence, flash frozen for RNA isolation, or placed in RPMI + 10% FBS + HEPES 10 mM on ice for flow cytometry. For flow cytometry, CNS tissues were homogenized with dounce homogenizers in RPMI + 10% FBS + HEPES 10 mM and centrifuged briefly to collect supernatants which were frozen at −80˚ for subsequent protein quantification by ELISA. The cell pellet was resuspended in 30% Percoll (Cytiva), underlayed with 70% Percoll and myelin separated by centrifugation at 800xg for 30 min as described [80]. Cells were collected from the 30/70% percoll interface. Peripheral tissues were ground between glass slides, RBC lysed with ACK buffer (Quality Biological), and resuspended in FACS buffer (0.5% BSA, 0.05% sodium azide, 5% FBS, 1 mM EDTA in PBS). Cell suspensions were counted using Countess® II FL Automated Cell Counter (ThermoFisher), blocked with anti-CD16/32 clone 2.4G2 (Bio X Cell), and stained for viability using LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain (ThermoFisher). Surface markers were stained using combinations of the following conjugated antibodies (from BD Biosciences): TCRb-AF700 (clone H57-597), CD4-APC (clone RM4-5), CD8-BB700 (clone 53–6.7), CD19-BV605 (clone 1D3), CD11b-BUV661 (clone M1-70), and CD45-BV786 (clone 30-F11). Blood was collected from live mice by tail vein bleeds into PBS supplemented with heparin and processed for flow cytometry as above. B cells were bead purified by negative selection from spleens using EasySep™ Mouse B Cell Isolation Kit (Stemcell Technologies). Cells were stained for flow cytometry or frozen for RNA isolation.

FACS sorting

Mice were euthanized, perfused with PBS + heparin (5U/mL) and brains were homogenized by grinding with a dounce homogenizer in RPMI + 10% FBS + 10 mM HEPES. Myelin was removed with 70%/30% myelin gradient spun at 800xg for 30 min. Cells were collected from the interface and strained with 70 μm cell strainer and washed with complete RPMI and centrifuged. Cell pellets pooled from two mice were resuspended in FACS buffer and cells were blocked with anti-CD16/32 blocking antibody and stained with CD45-PerCP (clone 30-F11), CD19-PEcy7 (clone 1D3), TCRβ-PE (clone H57-597), CD11b-FITC (clone M1-70), NK1.1-APC (clone PK136) all 1:200 dilution for 20 min on ice. Cells were then spun down and washed in FACS buffer with DAPI (1ug/mL) followed by a wash in FACS buffer only. A FACS Aria was used to isolate live single cells of the following populations: CD11b+ cells (CD45+, CD11bhi), NK cells (CD45+, CD11b−, NK1.1+), T cells (CD45+, CD11b−, NK1.1−, TCRβ+), and B cells (CD45+, CD11b−, NK1.1−, CD19+).

RNA isolation and quantitative real time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Tissues for RNA extraction were flash frozen and stored at −80˚ C until RNA isolation by phenol chloroform extraction. Contaminating DNA was removed by DNase I digestion for 30 min Thermofisher) and RNA was reverse transcribed using the M-MLV Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermofisher). The following taqman primer probe sets were used:

| Ccl19 | Mm00839967_g1 |

| Ccl21 | Mm03646971_gh |

| Ccr7 | Mm01301785_m1 |

| Csf2 | Mm01290062_m1 |

| Cxcl13 | Mm00444534_m1 |

| Fap | Mm00484254_m1 |

| Gapdh | Mm99999915_g1 |

| Ifng | Mm01168134_m1 |

| Ighd | Mm03979980_s1 |

| Il6 | Mm00446190_m1 |

| Lta | Mm00440228_gH |

| Ltb | Mm00434774_g1 |

| Ltbr | Mm00440235_m1 |

| Mb1 | Mm00432423_m1 |

| Ms4a1 | Mm00545909_m1 |

| Pdpn | Mm00494716_m1 |

| Tnf | Mm00443258_m1 |

Custom virus-specific primer probe set A59-N F – CCAGTTATGGAGACAGCATTGA, Probe – CAAACAGCCAAGCGGACACCAAT, R – GGCGCAAACCTAGTAGGAATAG. The following Sybr green primers were used: Clec1a F – ATGCAGGCCAAATACAGCAG R – CCAGAATACAGGCTTATGGTGGT, Cd4 F – TCCTTCCCACTCAACTTTGC R – AAGCGAGACCTGGGGTATCT, Cd8a F – TCAAGACGGCCCTTTCTCAGT R – ACCGTCGCGCAGAAGTAGA, Gapdh F – CATGGCCTTCCGTGTTCCTA R – ATGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCT.

ELISA

Supernatants were collected from brains and olfactory bulbs following homogenization with dounce homogenizers and pelleting cells and debris by spinning at 800xg for 7 min. Aliquots were stored at −80˚ C until analysis. CCL21 ELISA (Cat#DY457, RnD Systems) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

Brains frozen in OCT were cut in 15um sections on a cryostat (Leica Microsystems), mounted on glass slides, and frozen at −80˚ C until staining. For staining, tissues were briefly dried to adhere tissue to the slide. OCT was then washed off with PBS and tissue was fixed briefly in PFA. Tissues were permeabilized and blocked, treated with primary antibody, washed, and stained with conjugated secondary antibody. The following antibodies were used: PDPN (clone 8.1.1), IgD (clone 11-26c, eBiosciences), CD3 (Polyclonal, Abcam), CD3e (17A2, Thermo Scientific). CD45 (30-F11, Biolegend), Laminin (cl54851ap-1, Cedarlane), ERTR7 (MA1-40,076, Thermo Scientific), goat anti-rabbit-488 (Abcam), goat anti-rat-594 (ThermoFisher), BV480-conjugated Streptavidin (BD) and goat anti-hamster-647 (Abcam). Slides were briefly stained with DAPI, washed again, and mounted with aquamount (Epredia). Cells were imaged on LSM 800 (Zeiss) or DM6 B (Leica) confocal microscopes at 20X or 40X. Stromal marker intensity were measured by selecting the stromal cells using laminin and record intensity of markers on the stromal cells. Immune area was measured by dividing the size of the meningeal immune clusters by the lengths of pial surface. Density of parenchymal cells was measured by divided the number of cells per area of quantified parenchyma.

Software

Microscopy images were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH) or Imaris (Oxford Instruments). Plots were generated, and statistics performed using Prism (GraphPad Software Inc.). Flow cytometry data was analyzed with FlowJo (Becton, Dickinson & Company).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants R01 NS086299 (B.T.B, M.H., E.B., H.O. A.L. and C.B.), T32 GM152319 (B.T.B.), R21 AI161400 (A.V.T.), R21 AI173816 (A.V.T.). The authors would like to thank Dr. Carl Ware for providing the LTβR agonist.

Authors’ contributions

BTB, AL, CCB conceptualized the project and designed the experiments. BTB, MH, EB, and HO performed the experiments and data acquisition. AT provided resources. BTB and CCB wrote original draft. All authors revised the manuscript. AL and CCB acquired funding.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by NIH grant R01 NS086299 (to C.C.B.) and in part by the NIH under the award T32 GM152319 (B.T.B.), R21 AI161400 (A.V.T.), and R21 AI173816 (A.V.T.).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal studies were carried out in accordance with Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Davidson S, et al. Fibroblasts as immune regulators in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021:1–14. 10.1038/s41577-021-00540-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Li L, Wu J, Abdi R, Jewell CM, Bromberg JS. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells steer immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:723–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lütge M, Pikor NB, Ludewig B. Differentiation and activation of fibroblastic reticular cells. Immunol Rev. 2021;302:32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Martin A, Stanossek Y, Pikor NB, Ludewig B. Protective fibroblastic niches in secondary lymphoid organs. J Exp Med. 2024;221:e20221220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moseman EA, et al. B cell maintenance of subcapsular sinus macrophages protects against a fatal viral infection independent of adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2012;36:415–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Shibayama C, et al. Type I interferon signaling in fibroblastic reticular cells prevents exhaustive activation of antiviral CD8 + T cells. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabb7066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorrier CE, Jones HE, Pintarić L, Siegenthaler JA, Daneman R. Emerging roles for CNS fibroblasts in health, injury and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2022;23:23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson EH, et al. Behavior of parasite-specific effector CD8+ T cells in the brain and visualization of a kinesis-associated system of reticular fibers. Immunity. 2009;30:300–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pikor NB, et al. Integration of Th17- and lymphotoxin-derived signals initiates meningeal-resident stromal cell remodeling to propagate neuroinflammation. Immunity. 2015;43:1160–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magliozzi R, et al. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain. 2007;130:1089–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe R, Kakizaki M, Ikehara Y, Togayachi A. Formation of fibroblastic reticular network in the brain after infection with neurovirulent murine coronavirus. Neuropathology. 2016;36:513–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cupovic J, et al. Central Nervous system stromal cells control local CD8 + T cell responses during virus-induced neuroinflammation. Immunity. 2016;44:622–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noor S, et al. CCR7-dependent immunity during acute Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergmann CC, Lane TE, Stohlman SA. Coronavirus infection of the central nervous system: host–virus stand-off. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:121–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss SR, Leibowitz JL. Coronavirus pathogenesis. Adv Virus Res. 2011;81:85–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rennert PD, Browning JL, Mebius R, Mackay F, Hochman PS. Surface lymphotoxin alpha/beta complex is required for the development of peripheral lymphoid organs. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1999–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rennert PD, James D, Mackay F, Browning JL, Hochman PS. Lymph node genesis is induced by signaling through the lymphotoxin beta receptor. Immunity. 1998;9:71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zindl CL, et al. The lymphotoxin LTalpha(1)beta(2) controls postnatal and adult spleen marginal sinus vascular structure and function. Immunity. 2009;30:408–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shou Y, et al. Redefining the role of lymphotoxin beta receptor in the maintenance of lymphoid organs and immune cell homeostasis in adulthood. Front Immunol. 2021;12:712632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackay F, Majeau GR, Lawton P, Hochman PS, Browning JL. Lymphotoxin but not tumor necrosis factor functions to maintain splenic architecture and humoral responsiveness in adult mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2033–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang K, et al. T cell-derived lymphotoxin is essential for the anti-herpes simplex virus 1 humoral immune response. J Virol. 2018;92:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang K, et al. T cell-derived lymphotoxin limits Th1 response during HSV-1 infection. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilhelm P, et al. Membrane lymphotoxin contributes to anti-leishmanial immunity by controlling structural integrity of lymphoid organs. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1993–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Browning JL, et al. Lymphotoxin beta, a novel member of the TNF family that forms a heteromeric complex with lymphotoxin on the cell surface. Cell. 1993;72:847–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowe PD, et al. A lymphotoxin-beta-specific receptor. Science. 1994;264:707–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanderkerken M, et al. ILC3s control splenic cDC homeostasis via lymphotoxin signaling. J Exp Med. 2021;218:e20190835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, et al. Type 3 innate lymphoid cell-derived lymphotoxin prevents microbiota-dependent inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15:697–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar V, et al. Global lymphoid tissue remodeling during a viral infection is orchestrated by a B cell–lymphotoxin-dependent pathway. Blood. 2010;115:4725–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers RC, King RG, Carter RH, Justement LB. Lymphotoxin α 1 β 2 expression on B cells is required for follicular dendritic cell activation during the germinal center response: cellular immune response. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:348–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tumanov AV, et al. Distinct role of surface lymphotoxin expressed by B cells in the organization of secondary lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 2002;17:239–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gramaglia I, Mauri DN, Miner KT, Ware CF, Croft M. Lymphotoxin alphabeta is expressed on recently activated naive and Th1-like CD4 cells but is down-regulated by IL-4 during Th2 differentiation. J Immunol. 1999;162:1333–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dejardin E, et al. The lymphotoxin-β receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-κB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magliozzi R, Columba-Cabezas S, Serafini B, Aloisi F. Intracerebral expression of CXCL13 and BAFF is accompanied by formation of lymphoid follicle-like structures in the meninges of mice with relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;148:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang M, Bergmann CC. Neuronal ablation of alpha/beta interferon (IFN-α/β) signaling exacerbates central nervous system viral dissemination and impairs IFN-γ responsiveness in microglia/macrophages. J Virol. 2020;94:e00422-e520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chhatbar C, et al. Type I interferon receptor signaling of neurons and astrocytes regulates microglia activation during viral encephalitis. Cell Rep. 2018;25:118-129.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moseman EA, Blanchard AC, Nayak D, McGavern DB. T cell engagement of cross-presenting microglia protects the brain from a nasal virus infection. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabb1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quintanilla M, Montero-Montero L, Renart J, Martín-Villar E. Podoplanin in inflammation and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denton AE, Roberts EW, Linterman MA, Fearon DT. Fibroblastic reticular cells of the lymph node are required for retention of resting but not activated CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:12139–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez AB, et al. Immune mechanisms orchestrate tertiary lymphoid structures in tumors via cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Rep. 2021;36:109422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy M, et al. Expression of the lymphotoxin beta receptor on follicular stromal cells in human lymphoid tissues. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ransmayr B, et al. LTβR deficiency causes lymph node aplasia and impaired B cell differentiation. Sci Immunol. 2024;9:eadq8796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pickens SR, et al. Characterization of CCL19 and CCL21 in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:914–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phares TW, DiSano KD, Stohlman SA, Segal BM, Bergmann CC. CXCL13 promotes isotype-switched B cell accumulation to the central nervous system during viral encephalomyelitis. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;54:128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lokensgard JR, Mutnal MB, Prasad S, Sheng W, Hu S. Glial cell activation, recruitment, and survival of B-lineage cells following MCMV brain infection. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alimzhanov MB, et al. Abnormal development of secondary lymphoid tissues in lymphotoxin beta-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9302–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tumanov AV, et al. Lymphotoxin controls the IL-22 protection pathway in gut innate lymphoid cells during mucosal pathogen challenge. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yasukawa M, et al. Expression of perforin and membrane-bound lymphotoxin (tumor necrosis factor-beta) in virus-specific CD4+ human cytotoxic T-cell clones. Blood. 1993;81:1527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ware CF, Crowe PD, Grayson MH, Androlewicz MJ, Browning JL. Expression of surface lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor on activated T, B, and natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:3881–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Syage AR, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the diversity of the immunological landscape following central nervous system infection by a murine coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gregory JL, et al. Infection programs sustained lymphoid stromal cell responses and shapes lymph node remodeling upon secondary challenge. Cell Rep. 2017;18:406–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DiSano KD, Stohlman SA, Bergmann CC. Activated GL7+ B cells are maintained within the inflamed CNS in the absence of follicle formation during viral encephalomyelitis. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;60:71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phares TW, DiSano KD, Stohlman SA, Bergmann CC. Progression from IgD+ IgM+ to isotype-switched B cells is site specific during coronavirus-induced encephalomyelitis. J Virol. 2014;88:8853–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Metcalf TU, Baxter VK, Nilaratanakul V, Griffin DE. Recruitment and retention of B cells in the central nervous system in response to alphavirus encephalomyelitis. J Virol. 2013;87:2420–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Metcalf TU, Griffin DE. Alphavirus-induced encephalomyelitis: antibody-secreting cells and viral clearance from the nervous system ▿. J Virol. 2011;85:11490–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hobeika E, et al. CD19 and BAFF-R can signal to promote B-cell survival in the absence of Syk. EMBO J. 2015;34:925–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tumanov AV, Kuprash DV, Nedospasov SA. The role of lymphotoxin in development and maintenance of secondary lymphoid tissues. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:275–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uchida J, et al. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor–dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1659–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jain RW, Yong VW. B cells in central nervous system disease: diversity, locations and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:513–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alt C, Laschinger M, Engelhardt B. Functional expression of the lymphoid chemokines CCL19 (ELC) and CCL 21 (SLC) at the blood-brain barrier suggests their involvement in G-protein-dependent lymphocyte recruitment into the central nervous system during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clarkson BD, et al. CCR7 deficient inflammatory dendritic cells are retained in the central nervous system. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gunn MD, et al. Mice lacking expression of secondary lymphoid organ chemokine have defects in lymphocyte homing and dendritic cell localization. J Exp Med. 1999;189:451–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moyron-Quiroz JE, et al. Role of inducible bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in respiratory immunity. Nat Med. 2004;10:927–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Atkinson JR, Hwang M, Reyes-Rodriguez A, Bergmann CC. Dynamics of virus-specific memory b cells and plasmablasts following viral infection of the central nervous system. J Virol. 2019;93:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu MT, Keirstead HS, Lane TE. Neutralization of the chemokine CXCL10 Reduces inflammatory cell invasion and demyelination and improves neurological function in a viral model of multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2001;167:4091–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peters A, et al. Th17 cells induce ectopic lymphoid follicles in central nervous system tissue inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:986–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kapil P, et al. Interleukin-12 (IL-12), but not IL-23, deficiency ameliorates viral encephalitis without affecting viral control. J Virol. 2009;83:5978–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.DiSano KD, Linzey MR, Royce DB, Pachner AR, Gilli F. Differential neuro-immune patterns in two clinically relevant murine models of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DiSano KD, Royce DB, Gilli F, Pachner AR. Central nervous system inflammatory aggregates in the Theiler’s virus model of progressive multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nilaratanakul V, et al. Germ line IgM is sufficient, but not required, for antibody-mediated alphavirus clearance from the central nervous system. J Virol. 2018;92:e02081-e2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schuhmann MK, Langhauser F, Kraft P, Kleinschnitz C. B cells do not have a major pathophysiologic role in acute ischemic stroke in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin MT, Hinton DR, Marten NW, Bergmann CC, Stohlman SA. Antibody prevents virus reactivation within the central nervous system. J Immunol. 1999;162:7358–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bergmann CC, Ramakrishna C, Kornacki M, Stohlman SA. Impaired T cell immunity in B cell-deficient mice following viral central nervous system infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:1575–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rawat K, Tewari A, Morrisson MJ, Wager TD, Jakubzick CV. Redefining innate natural antibodies as important contributors to anti-tumor immunity. Elife. 2021;10:e69713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Berahovich RD, Lai NL, Wei Z, Lanier LL, Schall TJ. Evidence for NK cell subsets based on chemokine receptor expression. J Immunol. 2006;177:7833–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okada T, et al. Antigen-engaged B cells undergo chemotaxis toward the T zone and form motile conjugates with helper T cells. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reif K, et al. Balanced responsiveness to chemoattractants from adjacent zones determines B-cell position. Nature. 2002;416:94–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gomez-Nicola D, Pallas-Bazarra N, Valle-Argos B, Nieto-Sampedro M. CCR7 is expressed in astrocytes and upregulated after an inflammatory injury. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;227:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eriksson KK, Cervantes-Barragán L, Ludewig B, Thiel V. Mouse hepatitis virus liver pathology is dependent on ADP-ribose-1’’-phosphatase, a viral function conserved in the alpha-like supergroup. J Virol. 2008;82:12325–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Banks TA, et al. A lymphotoxin-IFN-β axis essential for lymphocyte survival revealed during cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:7217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Atkinson JR, Bergmann CC. Protective humoral immunity in the central nervous system requires peripheral CD19-dependent germinal center formation following coronavirus encephalomyelitis. J Virol. 2017;91:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.