Abstract

Menopause not only affects fertility but also has widespread impact on systemic health. Yet, the molecular mechanisms underlying this process are not fully understood, partly due to the absence of robust, age-relevant preclinical models with comprehensive molecular and phenotypic characterization. To address this, we systematically compared three candidate mouse models of menopause: (1) intact aging, (2) chemical ovarian follicle depletion using 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD) administered at multiple ages, and (3) Foxl2 haploinsufficiency, a genetic model based on a transcription factor linked to human premature ovarian failure. Through histology, serum hormone profiling, single-cell transcriptomics and machine-learning approaches, we uncovered both shared and model-specific features of follicle loss, endocrine disruption, and transcriptional remodeling. The VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models revealed distinct patterns of hormonal and immune alterations not captured by intact aging alone. This comparative framework enables informed selection of context-appropriate preclinical rodent models to study menopause and the broader physiological consequences of ovarian aging.

Keywords: Menopause, ovarian aging, preclinical models, single-cell RNAseq, ovarian age clock

Introduction

Women are born with a finite ovarian reserve, and its progressive depletion with age leads to the irreversible cessation of reproductive function, known as menopause1–3. Epidemiological studies have shown that later age-at-menopause is associated with increased lifespan and reduced risk of age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and neurodegeneration4–6. Conversely, the onset of menopause is accompanied by a sharp rise in the incidence of age-associated pathologies, underscoring the widespread physiological consequences of ovarian aging7. Despite its clinical relevance, the molecular mechanisms linking ovarian failure to systemic aging remain poorly understood.

Menopause marks the end of female fertility and is characterized by significant shifts in the hormonal milieu, which exert systemic effects8. As the ovarian follicular pool becomes depleted, declining steroidogenic activity disrupts feedback regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis, leading to pronounced changes in reproductive hormones8. For example, circulating levels of estrogen and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) decline to near-undetectable levels, while follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and Inhibin A (INHBA) exhibit marked elevations9–11. This hormonal reprogramming impacts not only reproductive tissues but also multiple extragonadal systems, including the metabolic, skeletal, and central nervous systems12,13. Accurately modeling this complex endocrine transition in preclinical systems is essential for delineating the mechanisms through which ovarian dysfunction impacts systemic aging.

Currently available rodent models for menopause research each possess distinct limitations. Intact aging female mice remain the most widely used model due to their physiological relevance and ease of implementation. Moreover, decades of research across diverse systems have established a robust foundational understanding of age-related biological changes, providing a valuable reference point for comparative analyses. Yet, intact aging mice do not undergo true menopause; instead, they enter estropause, retaining low but detectable estrogen levels and lacking the postmenopausal hormonal milieu observed in humans14,15. Another popular preclinical model is the use of surgical removal of ovaries, known as ovariectomy (OVX). While OVX achieves complete estrogen depletion, the surgery bypasses the gradual endocrine transition associated with menopause, and eliminates post-reproductive ovarian tissue, which retains androgenic activity and contributes to aging phenotypes16. Thus, despite its popularity, OVX is a poor preclinical model of menopause.

An alternative approach involves chemical ovarian follicle depletion using 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD), which selectively targets small pre-antral follicles (primordial and primary follicles), and induces follicle atresia, and leads to progressive ovarian failure14. This strategy allows for temporal control of ovarian depletion and results in estrus acyclicity, estrogen deficiency, and compensatory FSH elevation, features that closely mirror human menopause17,18. However, prior applications of the VCD model have been limited to young mice (~2–3 months old), restricting its relevance for studying menopause in the context of organismal aging19,20. Given that age alters the metabolic, immune, and endocrine landscapes21–23, it is critical to evaluate how the timing of ovarian failure intersects with aging processes. For example, heterochronic parabiosis experiments have demonstrated that the aging systemic milieu can impair tissue function in young animals, with circulating factors from aged animals negatively affecting neurogenesis and cognitive function24. Thus, evaluating VCD exposure in older animals may yield important insights into how age-related changes in the systemic environment shape the physiological consequences of menopause.

The genetics of premature menopause in humans may also help expand the toolkit to study menopause in preclinical models25,26. Specifically, haploinsufficiency of Foxl2, a transcription factor essential for granulosa cell identity and ovarian function25–28, is a great candidate model for menopause in mice. Indeed, heterozygous FOXL2 mutations are causally linked to premature ovarian insufficiency in humans29–31. Although most research efforts have focused on full Foxl2 knockout mice25,26, which show high perinatal lethality and primary ovarian defects, previous studies did report anecdotal subfertility phenotypes of heterozygous carriers. Despite these promising reports, the physiological consequences of Foxl2 haploinsufficiency on ovarian health and function have not been characterized in mice in vivo. Unlike surgical or chemically induced models, Foxl2 haploinsufficiency enables the study of endogenous, genetically encoded ovarian dysfunction and its downstream systemic effects. This model offers a unique opportunity to interrogate gradual follicular depletion and endocrine dysregulation in the absence of exogenous perturbation (surgical or chemical insult).

In this study, we characterized and systematically compared three complementary mouse models that reflect distinct mechanisms of ovarian decline as candidate models of menopause: (1) the intact aging model, (2) a VCD-induced follicle depletion initiated at different ages spanning young adulthood to early middle-age, and (3) a genetic model of Foxl2 haploinsufficiency. Using these models, we sought to identify shared and model-specific features of ovarian functional decline across multiple biological scales and phenotypic layers. We integrated histological analyses, serum hormone profiling, and single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) to assess changes in ovarian structure, endocrine function, and transcriptional landscape across menopause models. Additionally, we developed hormone-based and transcriptome-based ovarian aging clocks to evaluate functional trajectories of reproductive aging. Together, our data provides a comprehensive framework for systematically evaluating and comparing physiologically relevant models of ovarian aging, thereby defining their distinct advantages and applications for studying systemic and molecular effects of menopause.

Results

Selection of mouse models of menopause for the study

To systematically assess and compare physiologically relevant menopause models, we characterized three rodent models that represent distinct mechanisms of ovarian dysfunction: (1) the intact aging model (“Aging model”), (2) a chemically-induced model using repeated intraperitoneal injections of 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD, “VCD model”)14,32, and (3) a genetic model of Foxl2 haploinsufficiency (“Foxl2 +/− model”)27. Our aim was to establish a comparative framework to evaluate these models in terms of histological, hormonal, and integrated ovarian health outcomes to evaluate their suitability for modeling key aspects of ovarian aging (Fig. 1a). The Aging model involved comparison of young adult (4-month-old) and old (20-month-old) female C57BL/6JNia mice. We selected these timepoints to capture the transition from adult reproductive with stable estrus cycling (4 months) to post-estropausal age (20 months), as C57BL/6 females typically remain cyclic until ~12 months and show pronounced ovarian aging phenotypes by 20 months33. The VCD model included C57BL/6J female mice injected with vehicle control (safflower oil, hereafter referred to as “CTL”) or VCD starting at 3, 6, 8, or 10 months of age. This scheme allowed us to examine how the timing of ovarian insult (potentially modeling varying “age-at-menopause”) can impact ovarian health outcomes, particularly when VCD exposure occurs closer to natural estropause transition in mice (~12 months)33. The Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model compared Foxl2+/+ and Foxl2+/− female littermate mice from our transgenic colony at young (3–4 months) and early middle-age (8–10 months), prior to the onset of natural estropause, to test whether partial loss of Foxl2 can recapitulate age-associated ovarian changes at earlier ages than control mice.

Fig 1. Characterization of ovarian health markers of animals from Aging, VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models.

a, Schematic of the experimental design. b-d, Representative hematoxylineosin staining images of ovarian tissues from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. For the VCD model, ovarian tissues were analyzed 5 months post-injection. e-g, Combined follicle counts (primordial, primary, secondary and antral follicles, and corpus luteum) from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. h-j, Serum AMH level quantification from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. k-m, Serum FSH level quantification from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. n-p, Serum INHBA level quantification from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. q-s, Ovarian health index from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. For panels e-s, statistical significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon test, and p-values are reported. Open data points indicate data used for ovarian health index calculation. Scale bar: 250 μm.

For the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, we generated Foxl2 haploinsufficient mice using a regenerated floxed targeting allele, as previously described27, which introduces a null mutation in the Foxl2 gene via deletion of the gene single exon, using services from Cyagen Biomodels LLC (Extended Data Fig. 1a; see Methods). Unlike prior studies that employed this allele for temporally controlled, conditional deletion in adulthood, our study used this strategy to achieve constitutive Foxl2 haploinsufficiency throughout life (see Methods). To confirm that reduced Foxl2 expression was indeed observed in ovarian tissue from Foxl2+/− animals, as required to observe phenotypic consequences of haploinsufficiency, we performed RT-qPCR using ovaries from young and early middle-age matched Foxl2+/+ and Foxl2+/− female mice from our colony (Extended Data Fig. 1b). While the young group showed only a non-significant trend towards decreased expression, the early middle-age Foxl2+/− ovaries showed a significant reduction in expression (p-value ~0.032; Extended Data Fig. 1b). To confirm whether Foxl2 haploinsufficiency had an impact on ovarian function in these mice, we examined fertility outcomes for Foxl2+/+ and Foxl2+/− females from our breeding colony (see Methods; Extended Data Fig. 1c,d; Extended Data Table 1). Interestingly, Foxl2+/− females showed a trend towards a smaller first litter size (p-value ~0.075; Extended Data Fig. 1c), as well as a significantly increased latency to first pregnancy compared to matched Foxl2+/+ females (p-value ~0.035; Extended Data Fig. 1d), suggesting impaired reproductive potential consistent with ovarian dysfunction or premature ovarian aging.

Histological and hormonal characterization of mouse menopause models

A decline in ovarian follicle numbers is a well-established hallmark of ovarian aging and menopause34. Thus, we performed histological analysis of ovarian follicle populations using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 1b–g; Extended Data Fig. 2). As expected, the Aging model showed a significant reduction in follicles at all developmental stages in old females, including primordial, primary, secondary, and antral follicles, as well as corpora lutea (Fig. 1b,e; Extended Data Fig. 2a), consistent with the established progressive follicular depletion that accompanies natural ovarian aging35,36. At five months post-injections, VCD-treated animals also showed significant depletion of follicle numbers, regardless of age-at-injection (Fig. 1c,f; Extended Data Fig. 2b). Due to the terminal nature of histological analysis, ovaries were collected for H&E staining at the single 5 months post-injection time point. This endpoint was selected to align with the conclusion of our longitudinal serum profiling, wherein monthly hormone measurements enabled tracking of endocrine changes over time (see below). In contrast, Foxl2+/− mice did not show any reduction in combined follicle counts; instead, we observed a trend toward increased follicle counts in the middle-aged Foxl2+/− animals (p-value ~0.08; Fig. 1d,g; Extended Data Fig. 2c).

To further assess ovarian function, we measured serum levels of AMH, FSH and INHBA, key markers of ovarian reserve and hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis regulation37,38 (Fig. 1h–p; Extended Data Table 2). In the Aging model, old females had decreased AMH and INHBA and increased FSH compared to young females, consistent with diminished ovarian reserve38,39 (Fig. 1h,k,n). A similar pattern was observed in the VCD model, whereby AMH and INHBA were decreased and FSH was increased compared to the vehicle control groups at 5 months post-injection timepoint (Fig. 1i,l,o). To enable a comprehensive analysis of endocrine responses across reproductive life stages, we also performed longitudinal hormone profiling over a five-month period following VCD exposure at various ages (3, 6, 8 and 10 months; Extended Data Fig. 3a–c). Interestingly, VCD injections at older ages resulted in attenuated hormonal shifts compared to younger counterparts, suggesting that ovarian or systemic factors at midlife may modulate sensitivity to VCD-induced insult to ovarian reserve. In the Foxl2+/− mice, we observed distinct hormonal trends: AMH levels were increased, FSH levels were mildly elevated, and INHBA levels were reduced compared to wild-type controls, although none of these changes reached statistical significance (Fig. 1j,m,p). The increased AMH levels are consistent with our histological findings of increased follicle counts in the Foxl2+/− animals (Fig. 1d,g). Importantly, FOXL2 has been shown to interact with AMH to modulate follicle recruitment in humans40. Thus, the increased follicle counts and AMH levels in the Foxl2+/− animals likely reflect altered gene regulatory network driven by Foxl2 deficiency, rather than true ovarian rejuvenation (see Discussion).

Next, we applied our previously described composite ovarian health index, which integrates information from follicle counts and serum hormone levels to yield a holistic measure of ovarian health41 (Fig. 1q–s). As expected, this index was significantly lower in old vs. young animals and VCD-treated animals vs. CTL (regardless of age-at-injection), reflecting impaired ovarian health (Fig. 1q,r). In contrast, Foxl2+/− mice did not differ significantly from wild-type animals at either age group, consistent with their preserved histological and hormonal profiles (Fig. 1s).

Together, these results provide a comprehensive characterization of three distinct candidate mouse models of menopause. Both the Aging and VCD models exhibit robust phenotypic hallmarks of ovarian decline, including depletion of follicular reserves and disrupted endocrine profiles, with the VCD model offering unique advantages for temporally controlled induction of ovarian dysfunction. In contrast, the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model presents an unexpected phenotype characterized by preserved or even elevated follicle counts and increased AMH levels, opposite to typical features of ovarian aging9–11, despite clear evidence of reproductive dysfunction (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d). These findings raise the possibility that Foxl2 haploinsufficiency alters ovarian physiology through mechanisms distinct from conventional aging, warranting deeper molecular investigation.

A hormone-based clock, “OvAge”, for non-terminal prediction of ovarian aging

Although the ovarian health index is a useful metric of ovarian health, its partial reliance on post-mortem histological measurements limits its applicability in longitudinal studies. Thus, we aimed at developing a complementary non-terminal metric of ovarian aging, using a hormone-based predictive machine-learning model, which we termed “OvAge”, capable of estimating ovarian age from circulating serum hormone levels (Fig. 2a). By incorporating AMH, FSH, and INHBA levels, we sought to develop a model that provides a more comprehensive and integrative assessment of endocrine function than evaluating each hormone individually. To increase the generalizability of the clock, we trained a random forest regression model using serum hormone data (AMH, FSH, and INHBA) from animals with intact ovarian function and no experimental perturbation, including animals from the Aging model, vehicle control (CTL) groups from the VCD model, Foxl2+/+ animals from the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, and data from Fshr+/+ animals from our previously published Fshr haploinsufficiency study42 (Fig. 2a). This hormone level data was then randomly partitioned into training (n = 190) and testing (n = 62) sets to enable robust evaluation of model performance (Fig. 2a).

Fig 2. Development and application of OvAge, a hormone-based ovarian aging clock.

a, Schematic representation of the OvAge clock development pipeline. Data from all animals from the Aging model, vehicle control (CTL) from the VCD model, Foxl2+/+ from the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, and Fshr+/+ from the Fshr haploinsufficiency model mice were used to train and test OvAge. b, Scatter plot comparing predicted and chronological age, reported in weeks, in the test dataset. c-d, Scatter plots comparing predicted and chronological age for VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. e-g, Age acceleration analysis for VCD model animals at 30-, 90- and 150-days post-injection. h, Age acceleration analysis for Foxl2 haploinsufficiency animals. Age acceleration was measured as the difference between predicted OvAge and chronological age. Open data points indicate data from out-of-bag predictions. For panels e-h, statistical significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon test, and p-values are reported.

Model performance evaluation showed strong agreement between predicted and chronological age in the withheld test dataset (Spearman Rho ~0.621; p-value ~7.4 × 10−8), confirming the robustness of our hormone-based OvAge clock (Fig. 2b). We then applied OvAge to assess ovarian age of VCD-injected and Foxl2+/− animals (Fig. 2c,d). In the VCD model, predicted ovarian age was consistently higher than chronological age across all age-at-injection groups, suggesting that VCD exposure accelerates ovarian aging (Fig. 2c). Notably, the gap between predicted and chronological age narrowed as the age-at-injection increased, a pattern consistent with both the hormone profiles and ovarian health index (Fig. 1l,o,r). In contrast, no consistent pattern was observed in the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model; predicted ages of Foxl2+/− animals varied and did not seem to differ substantially from their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 2d). To quantify the degree of divergence between predicted and chronological age, we computed hormonal age acceleration, defined as the difference between OvAge-predicted and true chronological age (Fig. 2e–h). For the VCD model, we analyzed animals at 30-, 90-, and 150-days post-injection (Fig. 2e–g). We observed significant increases in age acceleration in VCD-treated animals compared to controls at both 30 and 90-days post-injection across all age-at-injection groups (Fig. 2e,f). Interestingly, by 150 days post-injection, animals injected at 10 months of age (now aged ~15 months) no longer showed significant age acceleration (Fig. 2g). This may reflect convergence in ovarian aging trajectories in both vehicle control and VCD-treated animals as they approach or enter the estropausal interval (12–15 months in the C57BL/6 strain33). In contrast, animals from the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model did not show a consistent increase in OvAge or age acceleration (Fig. 2h). Instead, middle-age Foxl2+/− animals exhibited a statistically significant reduction in age acceleration (p-value ~0.011), consistent with other observed phenotypes in this model, including preserved follicle counts and higher AMH levels (Fig. 1d,g,j). These findings may reflect a unique regulatory trajectory in this model, which could offer a complementary perspective on ovarian aging as well as premature ovarian failure.

Together, our results demonstrate that OvAge effectively captures both accelerated and attenuated ovarian aging trajectories in response to different biological perturbations. The clock recapitulates expected aging patterns in intact naturally aged animals, reveals premature ovarian aging following VCD exposure, and highlights a distinct endocrine aging profile in the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model. These findings underscore the utility of OvAge as a non-terminal framework for assessing ovarian aging and provide insight into model-specific differences that may be leveraged to explore various facets of reproductive senescence.

Although the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model did not exhibit overt signs of ovarian dysfunction based on the ovarian health index or OvAge (Fig. 1s and 2d,h), we reasoned that its preserved endocrine profile does not preclude underlying molecular perturbations consistent with accelerated ovarian aging. Given the established role of FOXL2 in granulosa cell identity and ovarian maintenance, its association with premature menopause in humans29,30,43, and the fertility phenotypes that we observed (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d), Foxl2 haploinsufficiency may still disrupt transcriptional programs in the ovary before functional decline becomes apparent.

Thus, we next examined the transcriptional landscape of ovaries from each model using single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq), enabling deeper investigation of molecular aging dynamics across natural, chemical, and genetic models of menopause.

Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of ovarian cell types across menopause models

To characterize the ovarian transcriptional landscapes across candidate mouse menopause models, we performed scRNA-seq on ovaries collected from the Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models (Fig. 3a). For the Aging model, samples were collected from young (4-month-old) and old (20-month-old) animals to capture transcriptional changes associated with intact aging (Fig. 3b). For the VCD model, we focused on two age-at-injection groups, 3 and 10 months, to capture the extremes of VCD responsiveness observed in prior analyses, as well as two post-injection time points, 30 and 90 days, based on differential effects on age acceleration at these stages (Fig. 3b). For the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, ovaries were collected from Foxl2+/+ and Foxl2+/− animals at young adult (~4 months) and early middle-age (~9 months), enabling the assessment of gene expression changes driven by partial loss of Foxl2 function across adulthood (Fig. 3b). The resulting datasets yielded 9,559, 47,386, and 21,301 high-quality single cells from the Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models, respectively (Fig. 3a–e; Extended Data Table 3). Ovarian cell populations were defined through dimensionality reduction, unsupervised clustering, and annotation using both established marker genes and automated reference mapping to publicly available single-cell datasets (Fig. 3c–h; Extended Data Table 4; see Methods).

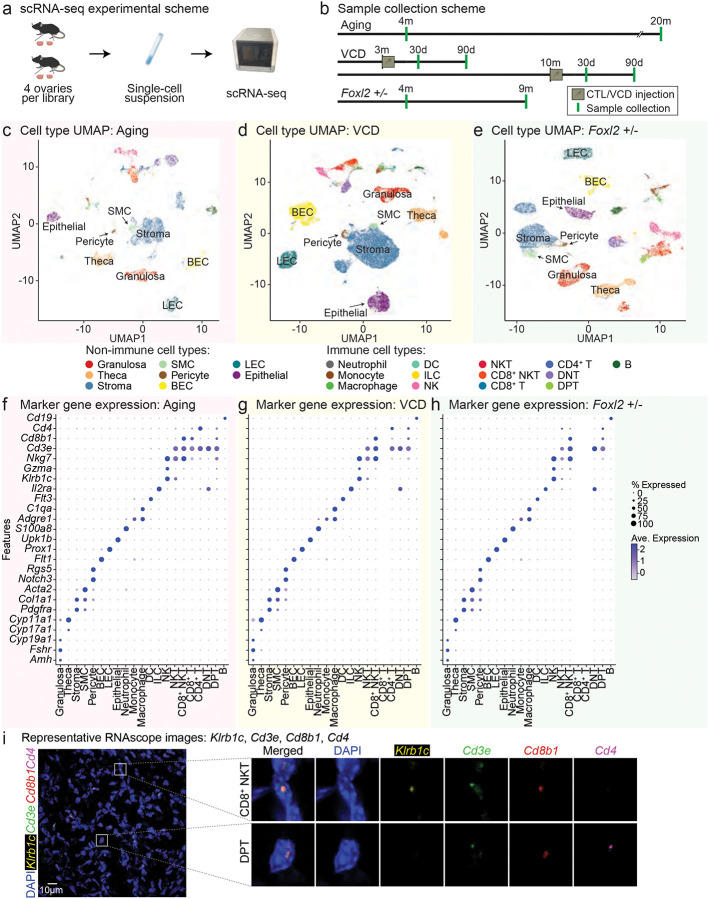

Fig 3. scRNA-seq profiling of ovaries from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice.

a, Schematic of the experimental design. b, Schematic of sample collection timepoints. c-e, UMAP plots of scRNA-seq datasets from Aging, VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models. f-h, Dotplot representation of expression of marker genes of cell types detected in scRNA-seq datasets from Aging, VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models. i, Representative RNAscope images of DAPI, Klrb1c, Cd3e, Cd8b1 and Cd4 probes. Images were enhanced for visualization. The shown image is from a middle-aged Foxl2+/+ animal.

After annotation of our scRNA-seq datasets, we were able to identify all major ovarian cell types (Fig. 3c–h). Among the abundant non-immune populations, granulosa cells (Amh, Fshr, Cyp19a1), theca cells (Cyp17a1, Cyp11a1), stromal cells (Pdgfra, Col1a1), smooth muscle cells (SMCs; Acta2), pericytes (Notch3, Rgs5), blood endothelial cells (BECs; Flt1), lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs; Prox1), and epithelial cells (Upk1b) were identified. The immune compartment included neutrophils (S100a8), monocytes (Adgre1), macrophages (C1qa), dendritic cells (Flt3), innate lymphoid cells (ILCs; Il2ra), natural killer (NK) cells (Klrb1c, Gzma, Nkg7), NKT cells (Cd3e, Klrb1c, Gzma, Nkg7), CD8+ NKT cells (Cd3e, Klrb1c, Gzma, Nkg7, Cd8b1), CD8+ T cells (Cd3e, Cd8b1), CD4+ T cells (Cd3e, Cd4), double-negative T (DNT) cells (Cd3e), double-positive T (DPT) cells (Cd3e, Cd8b1, Cd4), and B cells (Cd19) (Fig. 3f–h).

Given the known ovotoxic effects of VCD, we performed additional histological analyses on condition-matched ovaries (matched for age-at-injection and time post-injection) to confirm the presence of follicular structures in animals processed for scRNA-seq (Extended Data Fig. 4a). H&E staining of condition-matched samples revealed that despite extensive follicle depletion, residual follicles were present in most VCD-treated animals (Extended Data Fig. 4a). These findings were consistent with the detection of follicle-associated cell types in our scRNA-seq data (Fig. 3d,g). Quantification of total follicles by blinded observers further supported the persistence of follicular structures in the VCD model animals (Extended Data Fig. 4b). We also performed serum hormone quantification (AMH, FSH and INHBA) on age- and condition-matched samples corresponding to those used for scRNA-seq (Extended Data Fig. 5a–c). Consistent with previous findings, AMH and INHBA levels were reduced in the VCD groups (Extended Data Fig. 5a,c). To note, FSH levels were measured using an updated assay kit implemented by the University of Virginia Ligand core facility, distinct from the kit used in prior analyses (see Methods). Despite this change, we observed a trend toward increased FSH levels in the VCD-treated group relative to matched controls, although statistical significance was not reached, likely due to limited sample size (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Then, we evaluated the ovarian health index in these animals (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Because FSH was measured using a different assay than the one used to establish the ovarian health index, we implemented a previously reported correction procedure41 to ensure consistency and comparability of FSH values across cohorts (Extended Data Fig. 5d; see Methods). We observed a trend for lower ovarian health index scores in the VCD group compared to matched controls, although it did not reach statistical significance, again likely due to small sample size (Extended Data Fig. 4e).

To validate cell type assignments, we performed RNAscope, a high sensitivity in situ hybridization assay for both well-characterized and less frequently profiled ovarian cell populations (Fig. 3i; Extended Data Fig. 6). Granulosa cells (Fshr), theca cells (Cyp11a1), stromal cells (Pdgfra) and SMCs (Acta2) were validated using established marker probes, confirming their presence in the dataset (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Epithelial cells (Upk1b), BECs (Flt1) and LECs (Prox1) were similarly detected, supporting the robustness of annotations (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Importantly, we also validated the presence of various immune cell subsets, including NK (Klrb1c), NKT (Klrb1c, Cd3e), CD8+ T (Cd3e, Cd8b1), CD4+ T cells (Cd3e, Cd4), DNT (Cd3e, with no Cd8b1/ Cd4 signal) and B (Cd19) cells (Extended Data Fig. 6c). We also confirmed presence of less commonly reported ovarian cell types, including CD8+ NKT (Klrb1c, Cd3e, Cd8b1) and DPT (Cd3e, Cd8b1, Cd4) cells (Fig. 3i). These results further support the accuracy of the single-cell transcriptomic annotations and highlight the diverse somatic and immune microenvironments present across the aging models.

To assess cell type consistency across models, we compared annotated cell populations across datasets. A total of 19 cell types, 8 non-immune and 11 immune types, were shared across all three models (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Some cell types were not shared across models, potentially due to technical factors (e.g., capture efficiency and sequencing depth), or underlying biological variation inherent to each mouse model. To assist researchers in navigating the data efficiently, we developed an interactive R shiny app that makes the annotated datasets directly accessible and explorable through a graphical interface: https://minhooki.shinyapps.io/shinyappmulti/.

scRNA-seq analysis reveals shifts in ovarian cell composition in menopause models

Next, we examined changes in cell type proportions across our datasets (Fig. 4a; Extended Data Table 5). We first assessed whether the proportion of immune cells shifted with ovarian aging by analyzing the expression of Ptprc, which encodes Cd45, a pan-immune marker (Fig. 4b–d). In the Aging model, we observed a significant increase in Ptprc+ cells, indicating an expansion of the immune cell population with age (Fig. 4b). This is consistent with previous scRNA-seq studies in intactly aged mouse ovaries, which reported an increase in immune cell abundance at even younger ages (3 vs. 9 months; 4.5 vs. 10.5 vs. 15.5 months)44,45. In contrast, single-nucleus RNA-sequencing data from human ovaries did not identify a similar shift in immune cell proportions with age, consistent with potential species-specific differences in immune remodeling for the aging ovary46. However, this discrepancy could also reflect differences in age ranges examined or technical factors such as dissociation and capture methods inherent to single-nucleus versus single-cell approaches.

Fig 4. Characterization of cell type proportions in Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model scRNA-seq datasets.

a, Schematic of the experimental design. b-d, Proportion differences of Ptprc− and Ptprc+ cells between young vs. old in Aging model, CTL (vehicle control) vs. VCD in VCD model, and Foxl2+/+ vs. Foxl2+/− in the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model datasets. e-g, Flow cytometry analysis of CD45+ cell proportions in ovaries of Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. h-j, Proportion differences of non-immune cell types detected in Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model scRNA-seq datasets. k-m, Representative RNAscope images of Fshr (granulosa) and Cyp11a1 (theca) probes from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. Scale bar: 100μm. n-o, Cell abundance quantification data from RNAscope image analysis of Fshr+ and Cyp11a1+ cells from Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mice. For panels e-g and n-p, statistical significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon test, and p-values are reported.

VCD-treated mice exhibited a consistent reduction in Ptprc+ cells across all conditions, suggesting a depletion of immune cells following exposure to VCD (Fig. 4c). This reduction may result from the loss of follicular structures, alterations in immune recruitment, or uncharacterized systemic effects of VCD on immune homeostasis. Additionally, broader tissue remodeling processes, including fibrosis, may contribute to the altered immune cell landscape observed in VCD-treated ovaries. Thus, the VCD model does not seem to recapitulate immune features of intact aging ovaries in mice, regardless of age-at-injection. In the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, we detected a significant increase in Ptprc+ cells in the Foxl2+/− animals, regardless of age (Fig. 4d). These findings were further validated by flow cytometric analysis of CD45+ cells, using ovarian single-cell preparations generated with the same dissociation protocol as the scRNA-seq experiments (Fig. 4e–g; Extended Data Fig. 7a). Intriguingly, this suggests that the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model may better recapitulate immune shifts in the ovary seen with intact aging compared to the VCD model.

Then, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of all ovarian cell populations detected in the datasets to identify shifts in cellular composition in response to intact aging, VCD exposure, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency (Fig. 4h–j; Extended Data Fig. 7b–d). In the Aging model, nearly all non-immune cell populations showed a decline in proportion with age, except for stromal cells and LECs, which remained unchanged (Fig. 4h). In contrast, several immune cell populations increased with age, including neutrophils, DCs, ILCs, CD8+ NKT, CD4+ T, DNT, and DPT cells (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Notably, DNT cells have been reported to increase in aging mouse ovaries, and a potential role for these cells in regulating ovarian aging has been proposed44,47. Conversely, monocytes, NK, CD8+ T, and B cells exhibited a significant decrease with age (Extended Data Fig. 7b).

In the VCD model, cell proportion shifts were largely consistent within the treatment group, regardless of age-at-injection or time post-injection (Fig. 4i; Extended Data Fig. 7c). The VCD-treated group showed an increasing trend in stromal cells, BECs, LECs, epithelial cells, and CD4+ T cells. In contrast, granulosa cells, theca cells, SMC, and pericytes were significantly reduced in proportion (Fig. 4i). Among immune cells, neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, DCs, NKT, DPT, and B cells were all decreased following VCD treatment (Extended Data Fig. 7c).

In the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, granulosa and epithelial cell proportions were consistently reduced in Foxl2+/− animals, regardless of age (Fig. 4j). Conversely, monocytes, NK, CD8+ NKT, and B cells were increased in Foxl2+/− animals (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Interestingly, we observed opposing trends in stromal cells, macrophages, and DNT cells. Stromal cell proportions increased in Foxl2+/+ young mice but decreased in Foxl2+/+ animals at early middle-age, whereas macrophages and DNT cells showed the opposite trend. These findings highlight model-specific patterns of non-immune and immune cell remodeling, underscoring distinct trajectories shaped by chronological, chemical, and genetic perturbations of ovarian function.

To validate the cell abundance findings from our scRNA-seq data, we leveraged our RNAscope in situ hybridization data for representative non-immune and immune populations (see above; Fig. 4k–p; Extended Data Fig. 8,9). We examined granulosa cells, theca cells, stromal cells, SMCs, BECs, LECs, and epithelial cells, along with NK, NKT, CD8+ NKT, CD8+ T, CD4+ T, DNT, DPT, and B cells. In the Aging model, RNAscope confirmed a decrease in granulosa and theca cell abundances with intact aging, consistent with our scRNA-seq results (Fig. 4k,n). To note, there was non-specific staining for granulosa and theca markers (which are histologically absent in the old), which did not colocalize with DAPI, consistent with known technical limitations of the assay (Fig. 4k, right panel). Stromal cell proportions remained unchanged, again in agreement with the scRNA-seq data (Extended Data Fig. 8a). While the scRNA-seq data suggested a decrease in SMCs with age, we did not detect a significant difference by RNAscope, likely due to low detection sensitivity of the Acta2 probe. While epithelial cells showed a decreasing trend with age in the RNAscope dataset without reaching statistical significance, BECs exhibited a significant decline, consistent with scRNA-seq observations. We also examined LECs and did not observe any significant age-associated changes, which aligns with findings from the scRNA-seq data. For immune cells, RNAscope detected decreased abundances of NK, NKT, and B cells, and increased abundances of CD8+ NKT, CD4+ T, DNT, and DPT cells, closely recapitulating the scRNA-seq trends (Extended Data Fig. 9a). However, we did not observe a significant change in CD8+ T cells by RNAscope, despite a decrease in the scRNA-seq dataset (Extended Data Fig. 7b,9a). This discrepancy may stem from differences in detection sensitivity or spatial distribution of CD8+ T cells that may have limited probe accessibility in situ.

In the VCD model, we focused our RNAscope analysis on samples from 3-month age-at-injection and 30 days post-injection, given the consistent trends observed across conditions (Fig. 4l,o; Extended Data Fig. 8b,9b). Among non-immune cells, we observed a significant decrease in granulosa and increase in stromal with VCD exposure, consistent with scRNA-seq data (Fig. 4l,o; Extended Data Fig. 8b). We also observed some non-specific staining that did not colocalize with DAPI in the VCD-treated ovaries, where granulosa is histologically absent (Fig. 4l, right panel). Theca cells showed a decreasing trend in proportion with VCD exposure, but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4l,o). For SMCs, BEC, LECs and epithelial cells, RNAscope revealed no significant change in proportions with age, which contrasts with the scRNA-seq findings (Extended Data Fig. 8b). These inconsistencies may be attributable to a numbers of technical factors: (i) reduced probe efficacy, (ii) limited marker expression or (iii) under sampling of rare cell types in unique tissue slices compared to whole dissociated ovaries, all potentially leading to under-detection of rare cell types by RNAscope. For immune populations, RNAscope detected consistent decreases in NK, NKT, CD8+ NKT, CD8+ T and DNT cells, generally aligning with findings from our scRNA-seq results (Extended Data Fig. 7c,9b). CD8+ T and B cells did not show any differences in proportion with VCD exposure (Extended Data Fig. 9b).

In the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, RNAscope analysis revealed a reduction in granulosa cells in Foxl2+/− animals across both age groups, recapitulating the scRNA-seq findings (Fig. 4j,m,p). We also detected a non-significant decrease in epithelial cell proportions in Foxl2+/− animals in both age groups, consistent with the trends observed in scRNA-seq data (Fig. 4j; Extended Data Fig. 8c). A significant increase in SMCs and decrease in LECs in young and middle-age Foxl2+/− animals were observed, respectively, which aligns with the trends observed in our scRNA-seq datasets (Extended Data Fig. 8c). Theca cells, stromal cells and BECs did not show significant changes in abundance, consistent with scRNA-seq observations (Extended Data Fig. 8c). In the immune compartment, RNAscope identified patterns that were generally consistent with our scRNA-seq results (Extended Data Fig. 9c). For example, we observed increased proportions of NK and NKT cells in Foxl2+/− animals. Additionally, we observed increased DNT abundance in middle-age Foxl2+/− animals, which agrees with our scRNA-seq data (Extended Data Fig. 9c). As with other models, some cell types did not reach statistical significance in RNAscope, often due to lower detection rates, but the overall trends were consistent. Together, these findings further support model-specific shifts in immune and non-immune ovarian cell populations, as captured by both scRNA-seq and RNAscope-based validation.

Global transcriptional perturbations of ovarian cell types across menopause models

To systematically evaluate how different models of menopause influence global transcriptional responses in the ovary, we applied Augur48, a computational framework that quantifies cell type–specific separability across experimental conditions based on single-cell level gene expression profiles (Fig. 5a). Augur scores (derived from underlying machine-learning algorithm performance, reported as Area Under the Curve [AUC] values) represent the ability within each cell type to distinguish between biological groups within a given model based on overall transcriptional landscapes48. In the Aging model, granulosa cells exhibited the highest AUC score (AUC ~0.79), reinforcing their role as key transcriptional responders to chronological aging (Fig. 5b,c). Among other non-immune cell types, BECs and LECs also showed relatively high transcriptional divergence, suggesting that vascular and lymphatic compartments may undergo age-associated remodeling. Indeed, vascular decline has been closely linked to ovarian aging in multiple species, including humans, non-human primates, and mice46,49,50. In the immune compartment, CD4+ T, NK, and B cells ranked highest (Fig. 5b,c). Interestingly, DNT cells, despite their expansion in the aging ovary, showed the lowest AUC score (AUC ~0.53), indicating limited transcriptional remodeling with age (Fig. 5b,c, Extended Data Fig. 7b).

Fig 5. Comparative analysis of global gene expression in Aging, VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models via Augur.

a, Schematic of global gene expression analysis comparisons using Augur. b-c, UMAP visualization of AUC scores and lollipop plot of AUC quantification from the Aging model. d-e, UMAP visualization of AUC scores and scatter plot of AUC quantification from the VCD model, comparing CTL vs. VCD at 3m and 10m age-at-injection. For the scatter plot, Ptprc− and Ptprc+ cells were separately plotted to improve visualization. All data are from the 90d post-injection timepoint. f-g, UMAP visualization of AUC scores and scatter plot of AUC quantification from the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model comparing Foxl2+/+ vs. Foxl2+/− at young and mid-age. For the scatter plot, Ptprc− and Ptprc+ cells were separately plotted to improve visualization. For e and g, data points with NA AUC scores (due to low cell count or QC filtering) were assigned an AUC of 0.5 and colored gray to improve visualization.

In the VCD model, we observed marked transcriptional perturbations in theca, stromal, BEC, and LEC cells, especially at 90 days post-injection, with these effects largely consistent across both 3-month and 10-month age-at-injection groups (Fig. 5d,e). However, epithelial and granulosa cells displayed more pronounced age-at-injection-dependent differences: epithelial cells were more responsive in younger animals, while granulosa cells were notably absent in the 10-month cohort, likely reflecting more severe follicular depletion (Fig. 5e, left panel). Among immune cell types, NK, DNT, and CD8+ NKT cells showed higher transcriptional sensitivity in younger animals (Fig. 5e, right panel). At 30 days post-injection, transcriptional divergence was generally more divergent in the VCD model compared to its 90-day counterpart (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). For example, LECs in the 10-month group displayed strong divergence (AUC ~0.81), suggesting age-related vascular remodeling may emerge early after VCD exposure.

In the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, transcriptional divergence was more pronounced at middle-age, suggesting that the effects of Foxl2 loss may not fully manifest in the young ovary (Fig. 5f,g). Among non-immune populations, granulosa and theca cells showed the highest AUC scores at mid-age, while epithelial cells were more divergent in the young group (Fig. 5g, left panel). In immune populations, neutrophils, NKT, CD8+ NKT, and B cells exhibited the strongest divergence, with all showing elevated AUC scores at middle-age, indicating potential immune activation or heightened sensitivity of specific immune compartments to Foxl2 insufficiency (Fig. 5g, right panel).

Together, these results reveal both common and model-specific overall transcriptional trajectories across ovarian aging paradigms. Granulosa cells consistently emerge as sensitive indicators of ovarian dysfunction across all three models. Immune cells show particularly pronounced divergence in Foxl2+/− animals (Fig. 5g, right panel), suggesting that immune alterations may precede, accompany, or even drive ovarian changes in this genetic model. These comparisons underscore the importance of contextualizing cell type–specific transcriptional changes within each model's mechanistic framework and highlight how distinct perturbations – such as chronological aging, chemical ablation, or genetic loss – can produce divergent molecular responses across ovarian cell types.

Transcriptional and pathway-level signatures across menopause models

To investigate transcriptional remodeling across menopause models, we performed differential expression and pathway enrichment analyses using data pseudobulked by cell type in each individual scRNA-seq library (Fig. 6a; Extended Data Table 6). Six cell types, granulosa, theca, stromal, BEC, epithelial, and DNT cells, were consistently detected across all three models and thus included in downstream analyses (Extended Data Fig. 11a). DESeq251 was used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each model: young vs. old in the Aging model; CTL vs. VCD in the VCD model (using age-at-injection and time post-injection as modeling covariates); and Foxl2+/+ vs. Foxl2+/− in the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model (using age as a modeling covariate). As expected, we confirmed reduced Foxl2 expression in Foxl2+/− animals at both ages based on our pseudobulked dataset (Extended Data Fig. 11b).

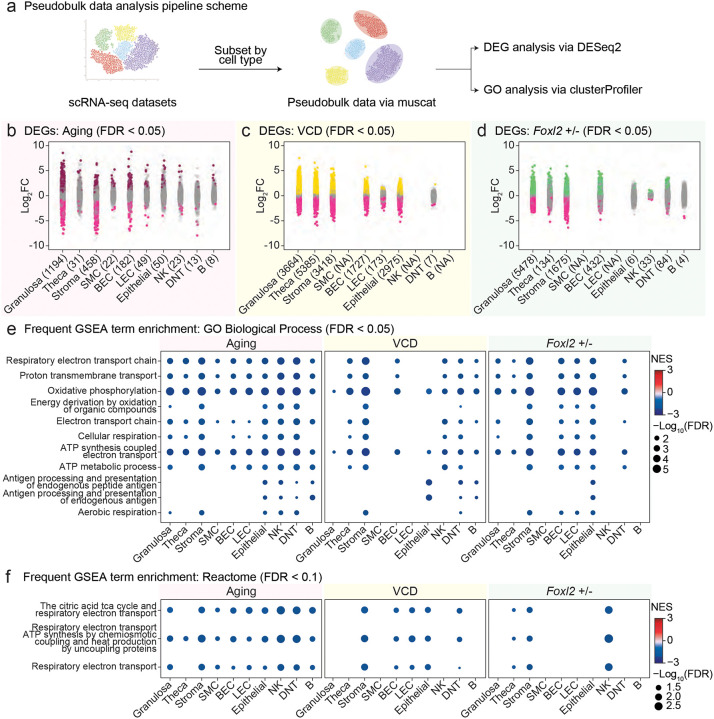

Fig 6. Pseudobulk analysis of differential gene expression and gene ontology analysis across Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models.

a, Schematic of pseudobulk analysis pipeline. b-d, Strip plots of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from Aging, VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models. DEGs were identified using DESeq2, comparing young vs. old (Aging model), CTL vs. VCD (VCD model), and Foxl2+/+ vs. Foxl2+/− (Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model). Genes that passed the FDR < 0.05 threshold are colored and the numbers in parentheses following each cell type indicate the total number of DEGs that met the significance threshold. e-f, Frequent Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) term enrichment for GO Biological Process (GO BP, FDR < 0.05) and Reactome (FDR < 0.1) pathways across Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models. Terms enriched in at least four and three cell types within each dataset were extracted for GO BP and Reactome, respectively.

Using an FDR cutoff of 0.05, we observed substantial transcriptional changes that were both model- and cell type-specific (Fig. 6b–d). Granulosa cells exhibited the highest number of DEGs in both the Aging (n=1,194) and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency (n=5,478) models, highlighting their sensitivity to physiological and genetic perturbations. In the VCD model, theca cells showed the strongest transcriptional response (n=5,385), followed by granulosa cells (n=3,664), suggesting robust transcriptional remodeling in both steroidogenic cell types following VCD exposure (Fig. 6b–d).

We next performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to identify gene ontology (GO) biological process terms recurrently enriched across models (Fig. 6e; Extended Data Table 7). Mitochondrial-related gene sets were consistently downregulated across models and cell types, including “Respiratory electron transport chain,” “Oxidative phosphorylation” and “ATP synthesis coupled electron transport” (Fig. 6e; FDR < 0.05). Immune-related processes, such as “Antigen processing and presentation of endogenous peptide antigen,” were also frequently identified as downregulated (Fig. 6e). Using independent gene sets from Reactome52 revealed consistent trends of mitochondria-related gene sets being downregulated (Fig. 6f; FDR < 0.1), suggesting convergent dysregulation of metabolic function during ovarian aging and in menopause models.

Together, these comparative analyses revealed both shared and model-specific transcriptional features of ovarian aging. Granulosa cells consistently exhibited robust transcriptional changes across all three models, underscoring their role as key responders to ovarian aging-related perturbations. Notably, mitochondrial dysfunction and immune dysregulation emerged as common themes across models and cell types, pointing to conserved biological pathways that may underlie the progression of ovarian aging.

Conserved and divergent aging-associated features are observed across menopause models

To identify features that may be broadly shared or uniquely diverge across menopause models, we derived age-associated gene signatures from the Aging model, which reflects natural ovarian physiological decline in mice (Extended Data Fig. 11c). These signatures were then used as a biological reference to explore potential patterns of convergence and divergence across the VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models (Extended Data Fig. 11c). VCD dataset showed consistent upregulation of aging-associated genes across cell types, whereas the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model exhibited partially divergent expression patterns (Extended Data Fig. 11c). Notably, granulosa and stromal cells showed decreased expression of genes typically upregulated with age, while BEC cells exhibited opposite trends for both age-associated up- and down-regulated genes. These patterns in a subset of cell types may reflect a distinct aging trajectory, or alternative molecular programs engaged in the setting of partial Foxl2 loss.

We also examined expression of the SenMayo53 gene set, a curated gene set of senescence-associated genes, which can be used as a proxy for senescence burden in transcriptional data (Extended Data Fig. 11d). In the Aging model, all six cell types tested showed significant upregulation of the SenMayo signature. In the VCD model, granulosa, stromal, BEC, and DNT cells mimicked this enrichment, while theca and epithelial cells showed a negative correlation. In the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, theca and DNT cells showed consistent upregulation, whereas granulosa, stromal, BEC, and epithelial cells showed an inverse pattern of downregulation (Extended Data Fig. 11d). These contrasting results suggest that the VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models may each capture distinct cell-specific aspects of an accelerated ovarian aging process.

We next evaluated transcriptional noise by calculating the coefficient of variation (CV) for each cell type (Extended Data Fig. 11e). Increased transcriptional variability is a characteristic of aging and has been observed across multiple tissues, including the ovary45 and hypothalamus54 in mice, reflecting a loss of transcriptional regulation with age. In the Aging model, CV increased across all detected cell types, except in DNT cells. In the VCD model, theca cells consistently exhibited increased CV, while granulosa and LECs showed more variable results. In the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, theca cells again showed increased CV regardless of age, although other cell types displayed inconsistent trends in young and middle-aged animals. While increased CV is often linked to age-related loss of regulatory precision54,55, these mixed results in VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models suggest a more nuanced transcriptional landscape that may reflect compensatory or cell type-specific adaptations.

Lastly, we assessed transposable element (TE) expression using scTE56 and DESeq2 (Extended Data Fig. 11f). TE activity is known to increase with aging across tissues, driven in part by age-associated chromatin remodeling, reduced heterochromatin integrity and impaired epigenetic repression57,58. In the Aging model, granulosa, stromal, SMC, BEC, and LEC cells showed increased TE expression with age, while theca, epithelial, NK, and B cells showed decreased TE expression. In the VCD model, TE expression increased in stromal, BEC, LEC, and epithelial cells, and decreased in theca cells. In the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, TE expression increased in most cell types, except stromal cells. Increase in TE expression is recognized as a hallmark of aging, contributing to genomic instability, inflammation, and cellular stress57,59. Rather than reflecting uniform activation of TEs, these cell type–specific shifts suggest that TE regulation may respond differently depending on the mechanism of ovarian perturbation (Extended Data Fig. 11f).

Gene co-expression network and transcription factor activity across menopause models

To identify gene regulatory programs associated with ovarian aging and dysfunction, we performed weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)60 and transcription factor (TF) activity inference using decoupleR61 (Fig. 7a). To obtain a comparative reference state, we first applied WGCNA to pseudobulked gene expression data from the Aging model, reflecting naturally occurring physiological changes. Modules with significant trait correlation to age (FDR < 0.1) were retained for downstream analysis (Extended Data Fig. 12,13). GSEA of these gene modules revealed strong enrichment in the Aging dataset (as expected by construction), providing a useful benchmark for evaluating transcriptional convergence and divergence across intact aging and intervention models (Fig. 7b).

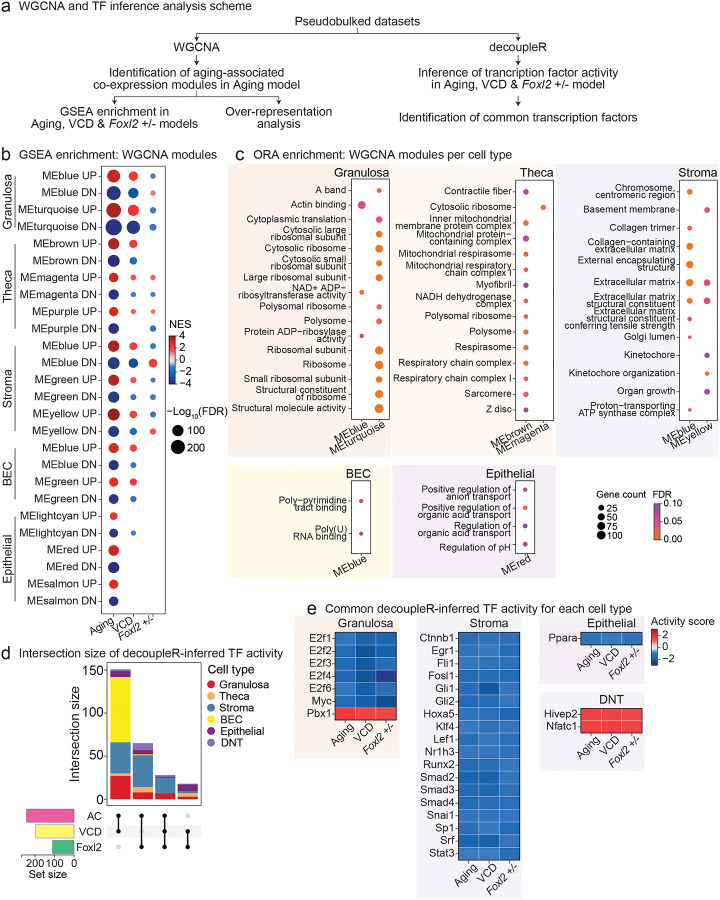

Fig 7. Preservation of co-expression modules and transcription factor activity in Aging, VCD, and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models.

a, Schematic of WGCNA and transcription factor (TF) activity inference analysis. b, GSEA enrichment of WGCNA module genes associated with aging traits across Aging, VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models. WGCNA modules significantly associated with aging traits (FDR < 0.1) were identified for each cell type from the Aging model. c, Over-representation analysis of GO ALL terms for WGCNA module genes (FDR < 0.1). d, UpSet plot of decoupleR-inferred TF activity, showing the number of TF overlap across datasets and the corresponding cell types. e, Heatmap of TF activity scores of common decoupleR-inferred TFs for each cell type.

In the VCD model, most modules exhibited enrichment patterns consistent with the Aging model, suggesting that VCD-induced ovarian failure recapitulates key transcriptional features observed during normal chronological aging. In contrast, the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model revealed notable differences in module behavior. For instance, in granulosa cells, genes from both reference modules were downregulated in the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency dataset, despite being upregulated in the Aging model (Fig. 7b). Conversely, the MEblue module, downregulated with age in the Aging model, was upregulated in Foxl2+/− granulosa cells. Theca cells showed broadly consistent enrichment across models, whereas stromal cells exhibited mixed and model-specific patterns (Fig. 7b). These findings illustrate both shared and model-specific regulatory programs and highlight the utility of comparative approaches to dissect diverse aspects of ovarian aging.

To further explore the biological relevance of these co-expression modules, we performed over-representation analysis (ORA) on each module’s genes using Gene Ontology. In granulosa cells, enriched terms included components of the ribosome and translational machinery (e.g., “cytosolic ribosome,” “polysome,” “cytoplasmic translation”), as well as actin binding and structural molecule activity (e.g., “A band,” “actin binding,” and “structural molecule activity”), highlighting coordinated regulation of protein synthesis and cytoskeletal organization. Notably, enrichment for NAD+ ADP-ribosyltransferase activity was also observed. This finding aligns with recent evidence linking the NAD+ pathway to the regulation of ovarian aging62. In theca cells, modules were enriched for mitochondrial and contractile fiber-related terms, including “mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I,” “respirasome,” and “sarcomere,” suggesting that transcriptional remodeling in aging theca cells may involve coordinated changes in energy metabolism and cytoskeletal dynamics. The appearance of the “NADH dehydrogenase complex” term further supports a role for the NAD+ pathway in theca cell aging62. Stromal cell modules were primarily enriched for extracellular matrix (ECM)-related pathways, such as “collagen-containing extracellular matrix,” “external encapsulating structure,” and “basement membrane,” consistent with known stromal remodeling during ovarian aging63,64. In BECs, we observed enrichment of RNA-binding activities, including “poly(U) RNA binding,” while epithelial cell modules were enriched for pathways related to pH regulation and organic acid metabolism, suggesting cell type–specific metabolic adaptations during aging.

To complement co-expression network-based analyses, we also inferred TF activity across cell types using decoupleR (Fig. 7d,e; Extended Data Table 8). Across datasets, we detected shared changed TF activity signatures in multiple cell types (Fig. 7d). In granulosa cells, we consistently observed decreased predicted activity of cell cycle–associated factors (E2f1, E2f2, E2f3, E2f4, E2f6, Myc) and increased predicted activity of Pbx1 (Fig. 7e). Pbx1 has been implicated in anti-aging pathways, as well as tissue and organ homeostasis and regeneration, in hair follicle-derived mesenchymal stem cells and adrenocortical cells, respectively65,66; thus, increased activity in the context of ovarian aging may reflect a compensatory response to maintain cellular function or structural integrity (Fig. 7e). Stromal cells showed consistent decreased predicted activity of several signaling and remodeling-associated TFs, including Runx2, Fosl1, Fli1, Klf4, Smad2/3/4, and Stat3. These factors are broadly involved in ECM remodeling, vascular integrity, immune signaling, and cellular stress responses46,67–69; thus, their coordinated decline may contribute to age-associated stromal dysfunction, fibrosis, and impaired tissue homeostasis. In epithelial cells, Ppara activity was consistently predicted to decrease across menopause models. Ppara has been shown to regulate lipid metabolism and oxidative stress responses70; its reduced activity in aged/treated epithelial cells may contribute to metabolic dysregulation associated with menopause. In DNT cells, Hivep2 and Nfatc1 showed increased activity (Fig. 7e). HIVEP2 has been implicated in regulatory T cell-mediated immunosuppression in humans71, while Nfatc1 is known to control cytotoxic function in CD8+ T cells in mice72,73. Intriguingly, Nfatc1 has been shown to be important for regulation of CD8+ T cell metabolism72. However, the specific roles of these factors in the context of DNT cells warrant further investigation.

These analyses reveal both conserved and model-specific gene regulatory programs underlying ovarian aging. Network-based approaches identified modules and transcription factors linked to protein synthesis, mitochondrial function, and ECM remodeling, with distinct patterns emerging across cell types and models.

Transcriptome-based aging clocks capture evidence of accelerated ovarian aging across models

To gain a complementary and integrative view of ovarian aging, we developed transcriptome-based clocks that predict ovarian age using gene expression data (Fig. 8a; Extended Data Fig. 15a), similar to efforts in other tissues, including blood and brain74,75. Given the central role of granulosa cells in ovarian function and their consistently high responsiveness in our models (see above), we first trained a lasso regression model using single-cell transcriptomes from granulosa cells (Fig. 8a). In parallel, we also constructed a comparable model using theca cell transcriptomes to evaluate performance in another key steroidogenic ovarian cell type (Extended Data Fig. 15a).

Fig 8. Development of a transcriptome-based aging clock for granulosa cells.

a, Schematic of analysis and training workflow for the lasso regression-based clock. b, Scatter plot of predicted age vs. chronological age for the test set, with Spearman’s correlation and p-value displayed. c-d, Age prediction for VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency datasets, comparing predicted age to chronological age in weeks. Offsets were added to improve visualization. e-f, Age acceleration analysis for VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency datasets, calculated as the difference between predicted and chronological age. Statistical significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon test. g, Heatmap of expression lasso features from pseudobulked expression data. h, Over-representation analysis of GO ALL terms of the top 500 lasso features.

Performance evaluation on the test dataset revealed strong predictive accuracy for the granulosa cell-based model, with a Spearman correlation of ~0.76 and p-value of ~3.9 × 10−293 between predicted and true chronological age (Fig. 8b). The theca cell-based model also performed well (Rho ~0.70, p-value ~1.9 × 10−237; Extended Data Fig. 15b), although it showed a dip in prediction accuracy at older ages. Notably, predictive performance in the theca model starts to decline at ~12 months of age, coinciding with the reported onset of estropause in mice of the C57BL/6 strain33 (Extended Data Fig. 15b; age of expected estropause onset highlighted in gray).

Having validated the predictive capacity of the model, we next applied the model to granulosa cell data from the VCD-treated and Foxl2+/− animals (Fig. 8c,d). In the VCD model, transcriptome-predicted ages were consistently higher than chronological age, supporting the notion that VCD exposure accelerates ovarian aging at the molecular level (Fig. 8c). In the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, Foxl2+/− animals also showed older predicted transcriptomic ages compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 8d). For granulosa cells, the median predicted age was 27.3 weeks in young Foxl2+/+, 43.0 weeks in young Foxl2+/−, 36.3 weeks in middle-age Foxl2+/+, and 38.5 weeks in middle-age Foxl2+/− (Fig. 8d).

To further quantify these differences, we calculated transcriptome-based age acceleration by subtracting true chronological age from predicted age (Fig. 8e,f). In the VCD dataset, age acceleration decreased as age at VCD exposure increased, a trend also observed in the hormone-based OvAge model, suggesting a reduced magnitude of response to insult in older ovaries (Fig. 2e–g, 8e). Granulosa cells from Foxl2+/− animals were predicted to be older than their chronological age, diverging from the results of OvAge, where condition-matched Foxl2+/− animals were predicted to be younger (Fig. 2h, 8f). This discrepancy suggests that the transcriptome-based clock likely detects early molecular alterations in the ovary that have not yet manifested as systemic hormonal shifts.

We also applied the theca cell-based aging clock to the VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models to determine its predictions on ovarian transcriptional age (Extended Data Fig. 15c,d). Despite slightly lower testing accuracy, the theca cell clock produced trends highly consistent with the granulosa-based model. Specifically, VCD-treated animals showed elevated transcriptomic age estimates compared to controls, and Foxl2+/− animals similarly exhibited increased predicted ages relative to wild-type counterparts (Extended Data Fig. 15c,d). The median predicted age was 26.7 weeks in young Foxl2+/+, 34.4 weeks in young Foxl2+/−, 34.9 weeks in mid-age Foxl2+/+, and 36.3 weeks in mid-age Foxl2+/−. We also calculated age acceleration for the theca cells and observed similar patterns to those seen in granulosa cells (Extended Data Fig. 15e,f). Notably, the difference between age acceleration estimates was statistically significant for all comparisons, including the middle-age group from the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model, further supporting its sensitivity in detecting molecular ovarian aging phenotypes across both VCD and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models. These findings reinforce the capacity of the theca cell-based clock to detect molecular signatures of accelerated aging and suggest that both granulosa and theca cells encode convergent transcriptional readouts of ovarian aging across models.

To explore the transcriptional features contributing to age prediction, features with non-zero β coefficients from the trained lasso model were extracted and their expression trajectories assessed across age in pseudobulked granulosa cell dataset (Fig. 8g). These features exhibited diverse patterns of expression over time, suggesting involvement in distinct age-related regulatory programs (Fig. 8g). To further investigate their biological relevance, the top 500 features, ranked by the absolute value of β coefficients in the final lasso model, were subjected to ORA enrichment (Fig. 8h). Enriched terms were primarily related to immune processes and vascular function, including “leukocyte migration,” “interferon-gamma production,” “positive regulation of antigen processing and presentation,” and “blood circulation” and “vascular remodeling” (Fig. 8h). These findings suggest that early shifts in immune signaling and vascular architecture may play a central role in shaping the transcriptomic landscape of ovarian aging and highlight the sensitivity of the transcriptome-based clock in detecting early molecular changes.

A similar approach was applied to the theca cell-based model, where features with non-zero β coefficients were extracted and their expression trajectories examined across age in the pseudobulked theca cell dataset (Extended Data Fig. 15g). These features also showed heterogeneous age-dependent expression patterns, indicating involvement of diverse regulatory programs during theca cell aging. To evaluate their biological relevance, the top 500 features, ranked by the absolute value of their β coefficients as above, were also subjected to ORA enrichment (Extended Data Fig. 15h). Enriched terms included immune-related processes such as “regulation of myeloid cell apoptotic process,” “regulation of cytokine production involved in immune response,” and “positive regulation of response to external stimulus,” as well as metabolic and structural pathways including “cellular response to lipid,” “collagen-containing extracellular matrix,” and components of the “mitochondrial outer membrane” and “membrane microdomains.” These results suggest that transcriptional aging in theca cells may be shaped by coordinated shifts in immune regulation, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial and membrane-associated processes.

Together, these data demonstrate the utility of transcriptome-based models for detecting molecular aging trajectories in the mouse ovary. These predictive tools offer a valuable framework for assessing molecular age across experimental models and for uncovering early transcriptomic alterations that precede overt phenotypic decline.

Discussion

Understanding how ovarian decline contributes to systemic aging requires robust experimental models that accurately recapitulate the physiological features of menopause. In this study, we systematically evaluated three mechanistically distinct mouse models of menopause: an intact aging model, a chemical follicle depletion model using VCD exposure, and a genetic model of Foxl2 haploinsufficiency. By integrating histological, hormonal, and transcriptomic profiling across these models, we provide a comparative framework for understanding shared and model-specific trajectories of ovarian aging. Findings from our study provide a critical comparative resource for identifying conserved and divergent features of ovarian aging and evaluating the suitability of each model, with the goal of advancing both mechanistic insights and translational strategies in menopause research.

In the Aging model, we observed hallmark features of physiological ovarian decline, including depletion of all follicle stages and disrupted endocrine profiles. These changes were accompanied by immune cell expansion, increased gene expression variability, elevated TE expression, and significant transcriptional remodeling in somatic and immune cell types. Granulosa cells consistently exhibited the highest transcriptional responsiveness, reinforcing their central role in orchestrating ovarian function and aging. Among immune populations, DNT cells displayed a marked increase in abundance with age. This expansion was also reported in two independent studies using mouse scRNA-seq datasets44,47, reinforcing the emerging role of DNT cells as conserved modulators of ovarian immune remodeling and aging. Mitochondrial dysfunction, immune activation, and vascular remodeling emerged as common transcriptional themes in the aging ovary. Gene regulatory network analyses further implicated downregulation of key transcription factors involved in cell cycle regulation, stress responses, and tissue homeostasis.

In the VCD model, animals displayed features reminiscent of premature ovarian failure, including acute follicular depletion, endocrine disruption, and elevated predicted ovarian age based on both OvAge and transcriptomic clocks. The extent of age acceleration was most pronounced in animals exposed to VCD at younger ages. This is particularly relevant given that early menopause is a strong predictor of systemic aging and reduced lifespan in humans4. By varying the timing of VCD exposure, this model could be leveraged to probe the systemic impact of menopausal timing and explore interactions between reproductive and systemic aging trajectories.

The Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model revealed a more nuanced aging trajectory. Despite normal or elevated follicle counts and serum AMH levels in young and mid-age Foxl2+/− animals, transcriptome-based clocks detected increased molecular age in granulosa and theca cells. Additionally, immune populations, including neutrophil, NKT and B cells showed enhanced transcriptional responsiveness, consistent with an immune-primed ovarian environment35,47. These results suggest that partial loss of Foxl2 function may induce early molecular reprogramming prior to overt histological or endocrine decline. Interestingly, granulosa and stromal cells showed inverse expression of classical aging signatures, and the model exhibited downregulation of typical senescence pathways and aging modules identified in the Aging model. FOXL2 has been shown to interact with AMH to modulate follicle recruitment in humans40. Thus, the observed histological, endocrine, and transcriptional features may reflect enhanced Amh-mediated reserve preservation in the Foxl2+/− animals. Nonetheless, the preserved endocrine output, coupled with increased transcriptional sensitivity in steroidogenic and immune compartments, positions the Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model as a unique tool for interrogating early or subclinical features of ovarian aging. Based on the increased transcriptional responsiveness of immune cells and the nuanced acceleration in transcriptomic aging of granulosa and theca cells, it may be valuable to assess these animals at older age ranges. The extended timeline could reveal whether early transcriptomic shifts translate into functional decline and help uncover regulatory mechanisms that are obscured in more overt aging models.

Cross-species single-cell analyses of ovarian aging further support the translational relevance of our findings. Studies in mice, non-human primates, and humans have consistently identified conserved molecular signatures associated with ovarian aging, including reduced oxidative phosphorylation, diminished antioxidant gene expression, and elevated immune activation across multiple ovarian cell types44–46,76. These transcriptional features were similarly prominent across all three models examined in our study. Additionally, regulatory network analyses from human ovarian datasets have implicated transcription factors such as FOXL1 and RUNX2 as age-associated regulators46. Although these factors were detected in different cell types in our dataset, their recurrent identification across species suggests that they may represent broader regulators of ovarian homeostasis. These cross-species parallels underscore the robustness of the aging signatures captured by our models and highlight the value of this comparative framework for investigating conserved mechanisms of ovarian aging.

Several mouse genetic models have provided additional insights into molecular features underlying ovarian decline. In a model with impaired interferon-gamma regulation (ARE+/− and ARE−/−), elevated systemic interferon-gamma led to CD8+ T cell infiltration in reproductive tissues and resulted in infertility77. In contrast, we observed a decrease in CD8+ T cell abundance in aged ovaries from our Aging model, raising the possibility that infiltration may occur earlier in the aging process, followed by depletion or exhaustion at advanced stages. CD8+ T cells were also sparse in the VCD and Foxl2 models, suggesting that interferon-mediated immune activation may represent a distinct and context-dependent mechanism.

A separate study investigating Cd38 deletion identified early ovarian inflammation and NAD+ depletion as key features of ovarian aging, with loss of Cd38 rescuing both transcriptional profiles and follicular health62. In the study, immune cell abundance decreased following Cd38 deletion62. In contrast, we observed increased immune cell abundance in the Aging and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency models, and decreased abundance in the VCD model. Despite these differences, our results converge with the Cd38 study on a set of transcription factors potentially involved in regulating ovarian aging. Notably, transcription factors such as Myc, Egr1, Fli1, and Klf4, reported to be restored upon Cd38 deletion, were also identified across all three models in our analysis62. These shared regulatory nodes point to conserved, age-sensitive networks that may facilitate physiological decline.

In summary, our comparative analysis reveals that ovarian aging is shaped by a combination of cell type–specific, model-specific, and shared molecular processes. Intact aging reflects gradual, widespread physiological decline; VCD exposure triggers acute and accelerated failure; and Foxl2 haploinsufficiency initiates early molecular perturbations that may precede functional impairment. By integrating histological, hormonal, and transcriptomic datasets, we provide a multidimensional framework for dissecting the mechanistic landscape of ovarian aging. This platform will be valuable for both basic and translational studies, offering new opportunities to define early biomarkers, and design interventions to delay or reverse reproductive senescence.

Methods and materials

Mouse husbandry

All animals were treated and housed in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experimental procedures were approved by the USC’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and are in accordance with institutional and national guidelines. Samples were derived from animals on approved IACUC protocol numbers 21155 and 21454. All animals were acclimated in the specific-pathogen-free animal facility at USC for two weeks prior to any experimental procedures. Mice were provided PicoLab Rodent Diet 20 (LabDiet, 5053) ad libitum. The facility was maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with housing rooms set to 72°F and 30% humidity.

For the Aging model, female C57BL/6JNia mice (4- and 20-month-old) were obtained from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) colony at Charles River Laboratories.

For the VCD model, female C57BL/6J mice (2.5-, 5.5-, 7.5-, and 9.5-month-old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Animals received daily intraperitoneal injections of either vehicle (safflower oil; Sigma S8281) or VCD (160 mg/kg/day; Sigma 94956) for 15 consecutive days. All injections were administered between 8:00 and 10:00 AM to minimize variability due to circadian influences.

Foxl2 floxed (Foxl2lox/lox) mice were generated by Cyagen Biosciences Inc. using a previously described targeting strategy25. Briefly, a targeting construct was designed to replace a 2.177 kb fragment containing the entire Foxl2 coding region with a 1.157 kb Neo gene cassette (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The construct was linearized and introduced into C57BL/6NTac embryonic stem (ES) cells via electroporation. Candidate clones were assessed via PCR and Southern blot analysis. A targeted ES cell clone was selected and injected into C57BL/6 NTac albino embryos, which were then implanted into pseudo-pregnant CD-1 females. Founder animals were identified based on coat color, and germline transmission was confirmed through breeding with C57BL/6 females followed by genotyping of the offspring. Mice carrying the desired floxed Foxl2 allele were sent to USC for experiments and downstream phenotyping.

Foxl2 haploinsufficiency mice (Foxl2+/−) were generated by crossing homozygous Foxl2lox/lox C57BL/6NTac mice with heterozygous B6.C-Tg(CMV-cre)1Cgn/J (JAX, stock #006054) mice. Offspring were genotyped for both the Foxl2 alleles and the CMV-Cre transgene. To eliminate the CMV-Cre transgene, Foxl2+/− mice were crossed with wild-type C57BL/6J mice. Progeny were selected to carry the deleted Foxl2 allele (Foxl2+/−), but not the CMV-Cre transgene. Afterwards, Foxl2+/− mice were maintained as a stable heterozygous knockout colony using allele transmission through both parent sexes. Routine genotyping was performed using genomic DNA extracted from tail biopsies using specific PCR primers, as listed in Extended Data Table 9a.

RT-qPCR analysis of Foxl2 expression in Foxl2 haploinsufficiency model mouse ovaries

Flash-frozen ovaries collected from mice were used for RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and quantitative RT-PCR. Ovaries were resuspended in 600 μL of TRIzol reagent (Thermo-Fisher, 15596018) and lysed using the BeadBug Homogenizer (Benchmark Scientific, D1036). Homogenization was performed at 3,500 rpm in 30-second intervals, repeated for a total of nine cycles. Total RNA was then purified using the Direct-Zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, R2052), following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was eluted in nuclease-free water sand immediately quantified using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The purity of the RNA was assessed by measuring the 260/280nm and 260/230nm absorbance ratios. Samples with ratios close to ~2.0 were considered suitable for downstream applications.