Abstract

Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome was among the first of the X-linked mental retardation syndromes to be described (in 1944) and among the first to be regionally mapped on the X chromosome (in 1990). Six large families with the syndrome have been identified, and linkage studies have placed the gene locus in Xq13.2. Mutations in the monocarboxylate transporter 8 gene (MCT8) have been found in each of the six families. One essential function of the protein encoded by this gene appears to be the transport of triiodothyronine into neurons. Abnormal transporter function is reflected in elevated free triiodothyronine and lowered free thyroxine levels in the blood. Infancy and childhood in the Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome are marked by hypotonia, weakness, reduced muscle mass, and delay of developmental milestones. Facial manifestations are not distinctive, but the face tends to be elongated with bifrontal narrowing, and the ears are often simply formed or cupped. Some patients have myopathic facies. Generalized weakness is manifested by excessive drooling, forward positioning of the head and neck, failure to ambulate independently, or ataxia in those who do ambulate. Speech is dysarthric or absent altogether. Hypotonia gives way in adult life to spasticity. The hands exhibit dystonic and athetoid posturing and fisting. Cognitive development is severely impaired. No major malformations occur, intrauterine growth is not impaired, and head circumference and genital development are usually normal. Behavior tends to be passive, with little evidence of aggressive or disruptive behavior. Although clinical signs of thyroid dysfunction are usually absent in affected males, the disturbances in blood levels of thyroid hormones suggest the possibility of systematic detection through screening of high-risk populations.

Introduction

Progress in the identification of genes and gene loci on the X chromosome that are responsible for mental retardation has greatly outpaced the search for autosomal genes that cause mental retardation. This is a result, in great part, of the power of hemizygosity of the X chromosome in males to clinically expose gene defects and the identification of large numbers of families that could be subjected to linkage studies, positional cloning, and other molecular technologies (Stevenson and Schwartz 2002). The experience with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (MIM 309600) is typical. Multigenerational families, beginning with the one reported in 1944 by Allan, Herndon, and Dudley, have been identified on the basis of childhood hypotonia, dysarthria, athetoid or other distal limb movements, muscle hypoplasia, and severe mental retardation (Allan et al. 1944; Bialer et al. 1992; Zorick et al. 2004). Linkage studies in several of these families placed the gene in the interval Xq13-q21 (Schwartz et al. 1990; Bialer et al. 1992; Zorick et al. 2004). Identification of mutations in the monocarboxylate transporter 8 gene (MCT8) in males with hypotonia, involuntary movements, and mental retardation made this gene an attractive candidate for Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (Dumitrescu et al. 2004; Friesema et al. 2004; Lenzner et al. 2004). Mutational analysis, reported here for six families with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome, identified one truncating mutation, one in-frame deletion, and four missense mutations in the gene.

Case Reports

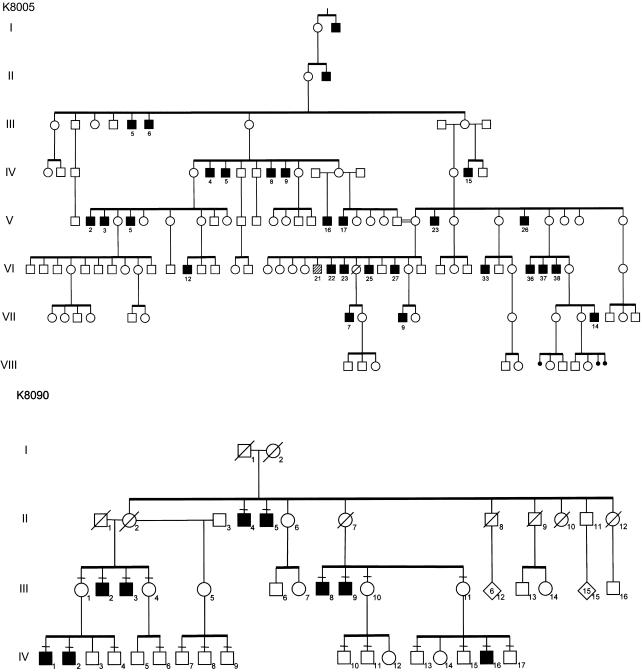

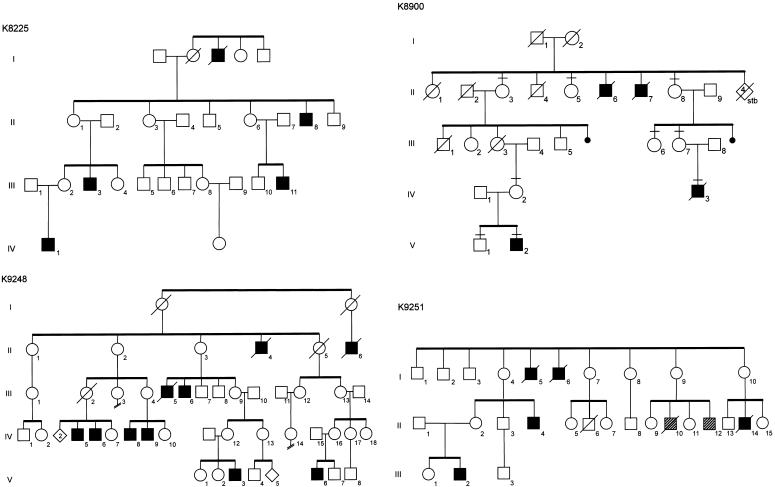

Clinical findings for two families with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome have been reported elsewhere (kindred 8005 [K8005] by Allan et al. [1944] and Stevenson et al. [1990] and K8090 by Davis et al. [1981] and Bialer et al. [1992]). Clinical findings for K8225, K8900, K9248, and K9251 are summarized below and in table 1. Pedigrees of the six kindreds are shown in figure 1. K8005 had lived for many generations in North Carolina and considered itself to be of Western European white ancestry, K8090 was of Irish ancestry, K8225 was white of uncertain ancestry, K8900 had lived for many generations in Mississippi and was presumed to be of Western European white ancestry, K9248 had mixed American Indian (Cherokee) and Irish ancestry, and K9251 was of Hispanic ancestry. High-resolution chromosome analysis results, molecular FMR1 analysis results, and plasma amino acid levels were normal for at least one affected male in each kindred. Results of clinical testing of thyroid function are given in figure 2. Although affected males were not frankly hypothyroid, many did exhibit weakness, pale and cool skin, dry hair, and constipation. None had prolonged neonatal jaundice, macroglossia, umbilical hernia, or myxedema. Two individuals (one in K8005 and one in K8900) had prominent eyes. Among 16 carrier mothers, 4 had thyroid disturbances: 3 had thyroid nodules in adult life, and 1 required treatment in adult life for hypothyroidism. With the exception of one carrier female (III-2 in K8225) with borderline low free thyroxine (T4) levels, the thyroid hormone levels in carrier females (n=8), noncarrier females (n=3), and nonaffected males (n=3) were normal (table 2). Neuropsychological evaluation showed all affected males to have severe cognitive impairment. Adaptive skills were also severely impaired (table 3). Carrier females have normal growth, appearance, and intellectual function.

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical Findings for Six Families with Allan-Herndon-Dudley Syndrome

|

Clinical Finding for Familya |

|||||||

| Trait | K8005b | K8090b | K8225 | K8900 | K9248 | K9251 | Totals |

| Age range of individuals evaluated | 25–71 y | 30–76 y | 1–39 y | 2–16 y | 22 mo–40 y | 13–25 y | … |

| No. of affecteds (no. of affecteds evaluated) | 28 (12) | 9 (8) | 5 (4) | 4 (2) | 10 (4) | 6 (2) | 62 (32) |

| Head circumference <3rd percentile | 0/12 | 0/8 | 0/4 | 1/2 | 2/4 | NA | 3/30 (10%) |

| Height <3rd percentile | 0/6 | 0/8 | 2/4 | 2/2 | 0/4 | NA | 4/24 (17%) |

| Weight <3rd percentile | 6/11 | 3/8 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 4/4 | NA | 19/29 (66%) |

| Hypotonia | 12/12 | 8/8 | 2/2 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 29/29 (100%) |

| Asthenic build/muscle hypoplasia | 9/12 | 7/8 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 28/32 (88%) |

| Narrow, long face | 6/12 | 8/8 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 2/4 | 2/2 | 24/32 (75%) |

| Myopathic appearance | 1/12 | 0/8 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 3/32 (9%) |

| Cupped/simple ears | 5/12 | 4/8 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 1/4 | 0/2 | 12/32 (38%) |

| Scoliosis | 2/12 | 7/8 | 3/4 | 1/2 | 2/4 | 2/2 | 17/32 (53%) |

| Pectus excavatum | NA | 6/8 | 1/4 | 0/1 | 2/4 | 2/2 | 11/19 (58%) |

| Contractures | 7/12 | 4/8 | 3/4 | 1/2 | 2/4 | 2/2 | 19/32 (59%) |

| Hyperreflexia/clonus | 12/12 | 7/8 | 3/4 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 30/32 (94%) |

| Dysarthria/limited speech | 12/12 | 6/8 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 4/4 | 0/2 | 22/32 (69%) |

| Absent speech | 0/12 | 2/8 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 0/4 | 2/2 | 10/32 (31%) |

| Nystagmus | 0/10 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/26 (0%) |

| Ataxia and awkward gait | 11/12 | 7/8 | … | … | 0/4 | … | 18/30 (60%) |

| Never walked | 1/12 | 1/8 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 0/2 | 12/32 (38%) |

| Valgus/everted feet | NA | 6/7 | 3/4 | NA | NA | 1/2 | 10/13 (77%) |

| Abnormal hand positioning | 10/12 | 6/8 | 4/4 | 1/2 | 4/4 | 1/2 | 26/32 (81%) |

| Undescended testes | 0/9 | 0/7 | 1/3 | 0/2 | 1/4 | NA | 2/25 (8%) |

| Testis volume <10 ml | 0/8 | 2/7 | 0/1 | …c | 1/1 | NA | 3/17 (18%) |

| Seizures | 1/11 | 2/7 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 5/27 (19%) |

Figure 1.

Partial pedigrees of six kindreds with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome. Blackened squares indicate affected males, and hatched squares indicate males with unrelated neurodevelopmental disorders.

Figure 2.

Serum levels of free T3 (top panel), free T4 (middle panel), and TSH (bottom panel) in affected males aged 0–5 years, 5–30 years, or >30 years from five of the six kindreds with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome

Table 2.

Thyroid Hormone Levels in Carrier Females, Noncarrier Females, and Nonaffected Males[Note]

| Subjects, Kindred,and Individual | Total T4(mcg/dl) | Free T4(ng/dl) | Total T3(ng/dl) | Free T3(pg/dl) | TSH(μIU/ml) |

| Carrier females: | |||||

| K8090: | |||||

| III-4 | … | 1.08 | … | 320 | 1.5 |

| K8225: | |||||

| III-2 | … | .8 | … | 286 | 1.5 |

| K8900: | |||||

| II-3 | … | 1.1 | 114 | … | … |

| II-8 | … | .9 | 110 | … | … |

| III-7 | … | 1.0 | 134 | … | … |

| IV-2 | … | 1.2 | 126 | … | … |

| K9248: | |||||

| IV-12 | 5.88 | 1.01 | … | 310 | 1.6 |

| IV-16 | 8.07 | 1.02 | … | 290 | 1.8 |

| Noncarrier females: | |||||

| K8900: | |||||

| NSa | … | 1.0 | 114 | … | … |

| II-5 | … | 1.1 | 94 | … | … |

| III-6 | … | 1.0 | 106 | … | … |

| Nonaffected males: | |||||

| K8005: | |||||

| VI-26 | 5.9 | .86 | … | … | 2.6 |

| K8900: | |||||

| V-1 | … | 1.2 | 154 | … | … |

| K9248: | |||||

| V-7 | 10.3 | 1.23 | … | 410 | 1.2 |

Note.— Normal ranges are as follows: total T4, 4.5–12.5 mcg/dl; free T4, 0.8–1.8 ng/dl; total T3, 60–181 ng/dl; free T3, 230–420 pg/dl; and TSH, 0.4–5.5 μIU/ml.

Noncarrier female not shown in abbreviated pedigree of K8900 in figure 1.

Table 3.

Cognitive Function and Adaptive Behaviors

|

Adaptive Skill Levelb(years/mo) |

|||||

| Kindred andIndividual | Age | IQa,b | Communication | Daily Living | Socialization |

| K8225: | |||||

| II-8 | 51 years | <20 | 0/11 | 1/1 | 0/11 |

| III-3 | 28 years | <20 | … | NA | … |

| III-11 | 14 years | <20 | … | NA | … |

| IV-1 | 13 years | NA | 1/5 | 1/6 | 2/3 |

| K8900: | |||||

| V-2 | 13 years | <20 | 0/11 | 0/10 | 0/11 |

| K9248: | |||||

| IV-5 | 40 years | <20 | 1/3 | 1/56 | 1/2 |

| IV-6 | 38 years | <20 | 0/11 | 1/4 | 0/8 |

| V-6 | 5 years | 24 | 1/0 | 0/11 | 0/9 |

| V-3 | 22 mo | NA | 0/6 | 0/9 | 0/9 |

| K9251: | |||||

| II-4 | 25 years | <30 | … | NA | … |

| III-2 | 13 years | <30 | … | NA | … |

K8225

Five males from four generations of this family were affected (fig. 1). The four living males, three obligate female carriers, and six nonaffected males were evaluated. Affected males are briefly described below, and findings are summarized in table 1. Nonaffected males and obligate female carriers had normal appearance, normal muscle mass, and normal intellectual function. Linkage analysis localized the syndrome between DXS983 (Xp11.3) and DXS101 (Xq22), with a maximum LOD score of 2.6 at DXS566 and DXS995 in Xq13-q21 (data not shown).

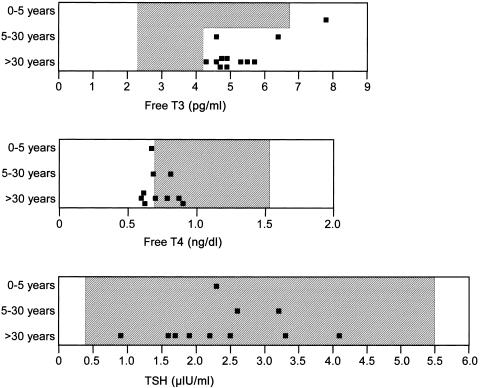

IV-1 was evaluated at age 1 year. The pregnancy had been complicated by maternal insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Delivery occurred at 39 wk, with a birth weight of 3.8 kg (80th percentile) and length of 53.3 cm (90th percentile). Respiratory and urinary tract infections occurred during the early months of life. Concern arose regarding his development at age 6 mo, by which time he showed poor feeding, general irritability, and poor muscle tone and strength. At 1 year of age, his measurements included a head circumference of 45.5 cm (10th percentile), length of 75 cm (30th percentile), and weight of 8.0 kg (<3rd percentile). The facies appeared normal (fig. 3A). Neuromuscular findings included inadequate head control, decreased muscle tone and strength, fisting, asymmetry of the thighs, eversion of the feet, increased deep tendon reflexes at the knees, Babinski signs, and exaggerated startle reflex.

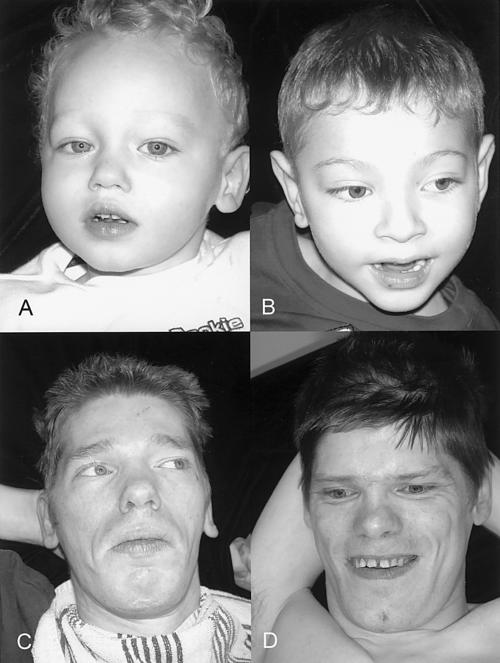

Figure 3.

Appearance of four affected males in K8225. A, IV-1 at age 1 year, showing a normal face. B, III-11 at age 14 years, showing an elongated and myopathic face. C, III-3 at age 28 years, showing synophrys and prominence of the lower lip. D, II-8 at age 39 years, showing an elongated face with prominence of malar areas and an open mouth.

III-3 was evaluated at age 28 years. His birth weight was 3.2 kg (40th percentile), and his birth length was 53.3 cm (80th percentile). Development was always delayed; he never walked and had no speech. Examination showed a head circumference of 54.7 cm (10th percentile), height with scoliosis of 155 cm (<3rd percentile), and weight of 30.8 kg (<3rd percentile). He was generally asthenic, and the head was held in a forward posture. The malar areas appeared prominent. Synophrys and vertical furrowing of the brow were present (fig. 3C). The upper helices were excessively folded. Testes were descended and of normal size. The hands were held in a clubbed position with clasped thumb. Elbow movement was restricted, scoliosis was present, and the halluces appeared long. Deep tendon reflexes in all four limbs were increased, and ankle clonus was present.

II-8 was evaluated at age 39 years. Birth weight was 3.6 kg (60th percentile). Development had always been severely impaired. Examination showed a head circumference of 57 cm (55th percentile), height of 165 cm (5th percentile), and weight of 49.5 kg (<3rd percentile). The facies appeared elongated, with prominent malar areas (fig. 3D). Pectus excavatum was present. Testes were not palpable. The hands were held in a clubbed position but were not contracted. There was a general reduction of muscle mass, and contractures were present at the knees.

III-11 was evaluated at age 14 years. His birth weight was 4.1 kg (85 percentile), and his length was 53.3 cm (80th percentile). Development was always severely delayed; he never walked or spoke. Seizures began at age 3 mo. His muscle mass was always poor. Examination showed a head circumference of 53.5 cm (20th percentile), length with contractures of 142 cm (<3rd percentile), and weight of 21.4 kg (<3rd percentile). The face appeared elongated and relatively expressionless (fig. 3B), and the palate was high. The right elbow was severely contracted, and the left elbow was minimally contracted. The right thumb was flexed, and the lower limbs were held in valgus positioning, with contractures at the knees and eversion of the feet. There was generalized decreased muscle mass, increased bicep reflexes, and ankle clonus.

K8900

Two of the four affected males, four obligate carrier females, and one nonaffected male from this family were available for evaluation. Linkage analysis placed the gene locus between DXS993 (Xp11.4) and DXS1002 (Xq21.31), with maximum LOD scores of 2.1 at DXS1003 in Xp11.3, 2.0 at AR in Xq12, and 2.0 at DXS986 in Xq21 (data not shown). Although initially suspected of having thyroid-binding globulin (TBG) deficiency, the TBG locus was excluded by these linkage findings. By report from an older sister, II-6 and II-7 were severely disabled and never walked or spoke. They had poor musculature and, in their later years, had “twisting” of the hands and feet. They experienced difficulty swallowing, had little fine or gross motor control, and had seizures. They appeared to see and hear; the eyes were described as having a “wild and scared” appearance. II-6 died in his twenties, and II-7 died in his thirties.

IV-3 weighed 3.6 kg (60th percentile) and was 52 cm long (60th percentile) at birth. The pregnancy was notable for decreased fetal movement for a brief period at 7 mo. Cesarean delivery was performed because of breech presentation. He appeared hypotonic and, by age 2 years, could not sit unassisted, crawl, or pull up. Examination showed generalized hypotonia, myopathic face, asthenic build, broad and proximally placed thumbs, transverse crease on the left hand, hyperreflexia, and clonus. The serum T4 level was reported to be low, but the specific value was not available. He died in his sleep at age 7 years.

V-2 weighed 3.6 kg (60th percentile) at full-term birth. Pregnancy was complicated by pneumonia and bronchiectasis. At age 1 h, he became cyanotic below the neck for unknown reasons. Cranial CT at age 3 mo showed ventricular enlargement with subdural fluid in the frontal regions, findings considered to represent brain atrophy. Seizures began at age 5 mo, and hypothyroidism was diagnosed at age 9 mo. He sustained several fractures attributed to osteoporosis. Examination at age 16.5 years showed a head circumference of 53.8 cm (10th percentile), weight of 28 kg (<3rd percentile), length with contractures of 127 cm (<3rd percentile), inner canthal measurement of 2.8 cm (25th percentile), and interpupillary measurement of 5.8 cm (50th percentile). He was alert and appeared to have some nonverbal interaction with the examiner. He followed lights and objects, but his capacity for hearing could not be determined. His eyes were prominent but not proptotic. Pinnae were simply formed, without folding of the superior helices. A gastrostomy feeding tube was in place. The limbs were poorly muscled, with contractures of the lower limbs and increased deep tendon reflexes at the left knee. The toes were held in clawed position, and the hands in clubbed position, with intermittent limb hyperextension and limb athetoid movements. Genitalia were prepubertal, and the testes were undescended. V-2 died at age 22 years of aspiration pneumonia.

K9248

Ten males with severe mental retardation, childhood hypotonia, and spastic paraplegia were from four generations of this white American Indian family. Four affected males, five obligate female carriers, and one nonaffected male were examined. Affected males appeared normal in growth and appearance at birth. Concerns arose during the latter part of the first 6 mo, because of failure to reach for objects and poor head control. Thereafter, the developmental lag became more obvious, as all motor and language milestones failed to occur on schedule. Except for one carrier female who suffered perinatal injury, all carrier females had normal intelligence and normal growth, including head circumference, and none had involuntary movements, hyperreflexia, or other neurological signs. One affected individual died of leukemia at 9 mo, one of pneumonia at age 32 years, and one of unknown cause in early adult life. Linkage analysis placed the gene locus distal to DXS453 in Xq13, with no further recombination observed down to marker DXS990 in Xq21.3, the most distal marker tested (data not shown).

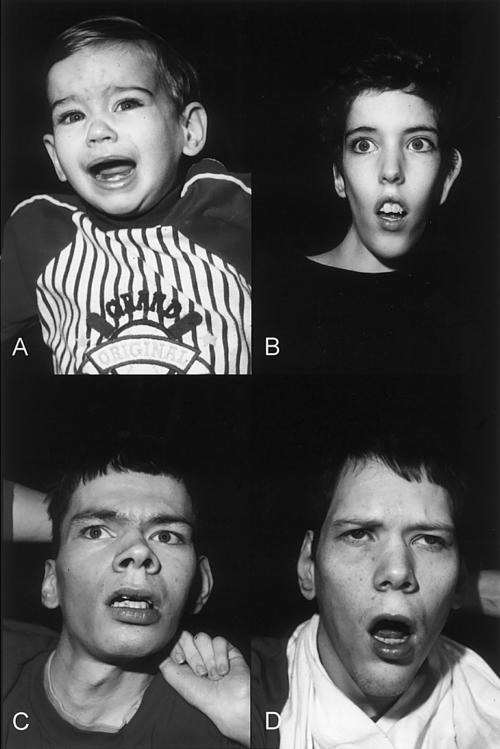

IV-5 was developmentally delayed from birth. He developed speech that was limited to a few words or phrases, beginning at age 2–3 years, and he never walked. Examination at age 40 years showed a head circumference of 54.3 cm (5th percentile), length with contractures of 185 cm (90th percentile), and weight of 58 kg (<3rd percentile). The face was elongated, with midface hypoplasia, narrow high palate, anteverted nares, spaced teeth, and square face (fig. 4D). The chest wall was asymmetric. Testes were undescended. Muscle tone and deep tendon reflexes were increased, more so in the lower limbs than in the upper limbs. Dysarthria, scoliosis, lower-limb scissoring, knee contractures, wrist flexion, and athetoid posturing of the hands were present.

Figure 4.

Appearance of four affected males in K9248. A, V-3 at age 22 mo, showing a cupped left ear, depressed nasal bridge, widely anteverted nares, and tenting of the upper lip with short philtrum. B, V-6 at age 5 years, showing incomplete folding of superior helices and short philtrum. C, IV-6 at age 38 years, showing elongated face with widow’s peak, flattening of midface, and square jaw. D, IV-5 at age 40 years, showing a long face with short philtrum.

IV-6 never walked and developed only limited speech. At age 38 years, his head circumference was 55.4 cm (20th percentile), height with contractures was 177 cm (60th percentile), and weight was 45 kg (<3rd percentile). A widow’s peak was present, and the midface was hypoplastic, with high and narrow palate, widely spaced teeth, and square jaw (fig. 4C). Truncal hypotonia, pectus excavatum, scoliosis, decreased lower-limb musculature, increased limb muscle tone and deep tendon reflexes, knee contractures, wrist flexion, and hand athetoid posturing were present.

V-6 weighed 3.4 kg (45th percentile), measured 51 cm in length (50th percentile), and had a head circumference of 34.6 cm (40th percentile) at term birth. Hypotonia and poor head control were obvious by age 6 mo. He rolled over at age 3 years and, by age 5 years, could not sit, pull up, or walk and had speech limited to 3–6 words. Examination at age 5 years showed a head circumference of 48.2 cm (<3rd percentile), length of 108 cm (50th percentile), and weight of 14.8 kg (<3rd percentile). He has amblyopia and myopia, cupped ears, anteverted nares, tenting of the upper lip, narrow tall palate, normal prepubertal genitalia, and a straight spine (fig. 4B). He also has truncal hypotonia, poor head control, increased limb tone and deep tendon reflexes, intermittent internal rotation of the arms, elbow hyperextension, and ankle clonus.

V-3 had a weight of 3.5 kg (50th percentile), length of 48 cm (10th percentile), and head circumference of 35.5 cm (55th percentile) at birth. At ∼6 mo of age, he was noted to have poor muscle tone, poor head control, and limited use of hands. He began rolling over at age 3–4 months but, at age 22 mo, could not sit, pull up, or crawl. Athetoid hand posturing was noted at age 5 mo. Although he said his first words at age 1 year, further speech development has been very limited. At age 22 mo, he had a head circumference of 46.5 cm (<3rd percentile), length of 84 cm (25th percentile), and weight of 9.7 kg (<3rd percentile). Facial features included depressed nasal bridge, anteverted nares, short philtrum, tented upper lip, and low-set and posteriorly rotated ears (fig. 4A). He had truncal hypotonia, limb hypertonia and hyperreflexia, upper-limb athetoid posturing, and lower-limb scissoring. Genitalia appeared normal.

K9251

Five males were affected in three generations of this family from Argentina. Three of those presumed to be affected were deceased. I-5 and I-6 were diagnosed with hypotonic cerebral palsy. II-14 died at age 7 mo, with global developmental delay. Because the phenotype was consistent with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome, linkage analysis was omitted, and mutational analysis of MCT8 was pursued.

II-4 had lifelong global delay, truncal hypotonia, poor head control, and limited motor skills. He had facial elongation, pectus excavatum, scoliosis, hyperreflexia, cavus feet, and contractures of the fingers, knees, and ankles. He has severe mental retardation and cannot walk or speak.

III-2 was born at term by Cesarean delivery and weighed 4.3 kg (90th percentile). Fetal movements were diminished during the last months of pregnancy. From birth, he exhibited truncal hypotonia and delayed development. At age 13 years, he showed poor control of the head and trunk, elongation of the face, mental retardation, and absence of speech and independent ambulation. He had scoliosis and dorsal kyphosis, pectus excavatum, contractures at the knees and ankles, and hyperreflexia. Nerve conduction; findings of electromyography, electroencephalography, muscle biopsy, and brain MRI; and levels of creatine kinase, plasma amino acids, and urine oligosaccharides and mucopolysaccharides were normal. Cranial CT showed cortical and subcortical atrophy.

II-12 is considered to have an unrelated neuromotor disorder, having no symptoms until age 15 years, when he developed difficulty in running and walking up stairs. He lost fine and gross motor skills and, at age 27 years, had distal muscle atrophy, cavus feet, and hyperreflexia. His mother had normal results for MCT8 mutational analysis.

Methods

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the parent(s) or guardian(s) of the affected individuals by use of the consent form approved by the Self Regional Healthcare Institutional Review Committee.

Preparation of DNA

Genomic DNA was prepared using a high-salt precipitation method with peripheral blood (Schwartz et al. 1990). The purified genomic DNA was diluted to 105 μg/ml and was stored at 4°C.

PCR

All exons were amplified individually. The primers, sizes, and annealing temperatures are available in table 4. All primers were tailed with M13 primers to facilitate sequencing. All exons were amplified using a PTC-200 thermocycler (MJ Research), with a total volume of 60 μl containing 1× PCR buffer with 1 μM of each primer, 0.08 mM dNTPs, and 0.02 U of GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega).

Table 4.

Sequences, Sizes, and Annealing Temperatures of Primers Used to Analyze the Exons and Adjacent Intron Sequences of MCT8

| Primer Pair Name | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Size(bp) | Annealing Temperature(°C) |

| MCT8 ex 1F/1R | 5′-CGGCTGCCTGTTGAGGGAGGAAGA-3′ | 5′-GCAGCGGGAGCGGCCAACCTT-3′ | 773 | 64 |

| MCT8 ex 2F/2R | 5′-CCAGCAGTACCACCAGGCACTACA-3′ | 5′-CATGGCCACAGGGGATTCTGC-3′ | 310 | 64 |

| MCT8 ex 3F/3R | 5′-AAGGGCGGAGGAATGGAAGTCTCA-3′ | 5′-CCCACCCCCACCCTCTGGAATCTA-3′ | 632 | 64 |

| MCT8 ex 4F/4R | 5′-GCCAAGGGATAAGCAGCCAGAG-3′ | 5′-CATGCGACACAACAAGCTACCATT-3′ | 417 | 57 |

| MCT8 ex 5F/5R | 5′-CCCCTCCCACCACCCCATTT-3′ | 5′-GGAGTGCCAGTACCCAGGGAAAAA-3′ | 411 | 64 |

| MCT8 ex 6F/6R | 5′-ACGGGCTGAGAGTACCTTTGGACA-3′ | 5′-GTGCGCAGGTCTGGGAACAAGTG-3′ | 395 | 57 |

Sequencing Analysis

PCR fragments for each exon were sequenced in both directions on the MegaBACE (Amersham Biosciences) by use of the M13 forward and reverse primers, in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The alignment and analysis of the sequences were done using the DNASTAR program (Lasergene).

Denaturing High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Analysis

Mutations in exons 1, 2, and 4 were subjected to heteroduplex analysis for segregation studies in the families and for screening in a cohort of normal males. To ensure proper formation of duplex DNA, the PCR product obtained from the proband or family member was mixed with an equal volume of PCR product from a control individual. The samples were denatured at 95°C for 12 min and were allowed to renature for 45 min by decreasing the temperature from 95°C to 25°C. For the normal male cohort, pools of four individuals were created for analysis after PCR amplification of each individual. Amplicons were analyzed on the WAVE DNA fragment analysis system equipped with DNA Sep column (Transgenomic), at the following temperatures: exon 1, 61°C; exon 2, 60°C and 63°C; and exon 4, 59.7°C and 60.5°C.

Ear1 Digestion of Exon 6 Amplicon

The mutation that was found in exon 6 destroyed an Ear1 restriction site. Digestion was performed using 10 μl of a PCR product generated using primers for exon 6 in a total reaction volume of 20 μl. The reaction mix contained 1× NEBuffer 1, 1× spermidine, and 0.25 μl Ear1 enzyme (NEB). The digestion occurred overnight at 37°C, and the products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel. Ear1 digested the 395-bp product from the proband of K8005 into 2 fragments of 328 bp and 67 bp. A normal individual has three fragments after Ear1 digestion: 155 bp, 173 bp, and 67 bp.

Computational Analysis of Altered MCT8 Proteins

Estimation of the effect of a mutation in MCT8 at the protein level was done using the Protean software available in DNASTAR (Lasergene).

Results

Direct genomic sequencing of the six exons of MCT8, plus 80 bp of flanking sequence on either side of the exons, detected alterations in all six kindreds with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (table 5). One mutation was truncating, one was an in-frame deletion, and four were missense. In K8900, a truncating mutation (p.S448X) was identified. The creation of the novel stop codon results in the protein missing the last four transmembrane domains (TMDs) as well as the carboxyl cytoplasmic end of the protein. K9251 was found to have an in-frame 3-bp deletion, c.683delTCT, which removes a phenylalanine at position 230 (delF230). This residue is the first of two phenylalanines in the middle of the second TMD and is highly conserved. In K8225, base substitution c.703G→A causes missense mutation p.V235M in the second TMD. This valine is highly conserved when compared to mouse and rat. Additionally, the presence of this methionine may create a novel initiation site. However, this possibility could not be examined further, because MCT8 is not transcribed in lymphocytes, the only tissue available for analysis. The second missense mutation, p.L434W in K8090, occurs in the eighth TMD. This leucine is highly conserved when compared to mouse and rat. In K8005, a c.1703T→C substitution produces missense mutation p.L568P. As with the p.L434W missense mutation, a highly conserved leucine residue is altered, this time in the twelfth TMD. The fourth missense mutation was found in K9248, resulting in a S194F change in the first extracellular domain between the first and second TMDs. None of these six mutations in MCT8 was found in 470 normal male controls.

Table 5.

MCT8 Mutations in Allan-Herndon-Dudley Syndrome

| Kindred | Mutation | Amino AcidChange |

| K8005 | c.1703T→C (exon 6) | L568P |

| K8090 | c.1301T→G (exon 4) | L434W |

| K8225 | c.703G→A (exon 2) | V235M |

| K8900 | c.1343C→A (exon 4) | S448X |

| K9248 | c.581C→T (exon 1) | S194F |

| K9251 | c.683delTCT (exon 2) | delF230 |

Discussion

Spastic paraplegia is among the more common of the clinical findings that co-occur with X-linked mental retardation. Spastic paraplegia 1 is part of the X-linked hydrocephaly spectrum caused by mutations in L1CAM (Vits et al. 1994). Spastic paraplegia 2 is the dominant clinical presentation of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher syndrome, caused by mutations in PLP (Saugier-Veber et al. 1994). In addition, spastic paraplegia is a prominent finding in 23 other X-linked mental retardation (XLMR) syndromes (Stevenson et al. 2000) (table 6). The progression to spastic paraplegia in the Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome is notable. From infancy into early childhood, hypotonia and decreased muscle mass dominate the neuromuscular findings. Hypotonia and weakness is particularly notable in the neck muscles. Truncal hypotonia persists into adult life. There is a transition in childhood to spasticity manifested by hyperreflexia at the large joints, clonus, and Babinski signs. Contractures commonly occur. Involuntary movements of the distal limbs, dystonic and/or athetoid in nature, occur in most affected individuals. Virtually all affected males become wheelchair bound in adult life, although many had achieved independent but delayed and unsteady ambulation.

Table 6.

X-Linked Syndromes with Spastic Paraplegia as a Major Phenotypic Manifestation

| Syndrome | Gene Locusa | Gene (If Known) |

| Adrenoleukodystrophy | Xq28 | ABCD1 |

| Allan-Herndon-Dudley | Xq21 | MCT8 |

| Apak ataxia–spastic paraplegia (cerebellar ataxia 2) | Xp11.21-q21.3 | |

| Arena | Xq22–25 | |

| Ataxia-deafness (Schmidley) | NL | |

| Brooks-Wisniewski-Brown | NL | |

| Christianson | Xq24-q27.3 | |

| Fitzsimmons | NL | |

| Gustavsson | Xq26 | |

| Kang | NL | |

| Lesch-Nyhan | Xq26-q27.2 | HPRT1 |

| Miles-Carpenter | Xq13-q22 | |

| Mohr-Tranebjaerg (Jensen) | Xq22 | TIMM8A |

| Paine-Seemanova | NL | |

| Pallister W | NL | |

| Pelizaeus-Merzbacher (spastic paraplegia, type 2) | Xq22 | PLP1 |

| Pettigrew | Xq25-Xq27 | |

| Psychosis–pyramidal signs–macroorchidism, X-linked | Xq28 | MECP2 |

| Proud | Xp22 | ARX |

| Rett | Xq28 | MECP2 |

| Schimke | NL | |

| X-linked hydrocephalus spectrum (spastic paraplegia, type 1) | Xq28 | L1CAM |

| X-linked lissencephaly | Xq22.3-q23 | DCX |

| XLMR-blindness-seizures-spasticity (Hamel) | Xp11.3-q12 | |

| XLMR-hydrocephaly–basal ganglia calcifications (Fried) | Xp22 | |

| XLMR-hypotonia–recurrent infections (Lubs) | Xq28 |

NL = not localized.

In all affected males with available records, intrauterine growth was normal. In early childhood, weight typically fell below the 3rd percentile and remained there. Length during childhood was usually normal; measurement of adult length was compromised by scoliosis and contractures, commonly measuring <3rd percentile. Occipitofrontal head circumference usually fell below average, but in only two instances were measurements <3rd percentile recorded (table 1).

The development of all 32 affected males who were evaluated was severely impaired from birth. None developed normal speech: 10 had no speech, and 22 had limited and/or severely dysarthric speech. Twelve males never ambulated independently. Ambulation was markedly delayed among those who learned to walk and was lost by adult life.

Compatibility with longevity was evident by the 8 affected males, of the 32 evaluated, who lived beyond 70 years. This notwithstanding, the family histories indicated that three affected males died before age 10 years, one died during the teen years, two died during their twenties, and four died during their thirties.

Cognitive impairment in affected males was severe. Since most affected males were unable to meet the baseline of standardized cognitive tests, the precise level of mental retardation could not be determined (table 3). There was no evidence of an unusual cognitive strength—the neuropsychological profile was generally flat, except for the fact that the subjects were remarkably affable and tuned into social interactions, which was even more remarkable because of the significant motor and cognitive handicaps. Because of the severity of cognitive impairment, some patients were evaluated with only the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale–Interview Edition (table 3).

The pattern of findings in these families with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome is the same as that in 10 other individuals/families with the MCT8 mutation reported by Dumitrescu et al. (2004), Friesema et al. (2004), and Lenzner et al. (2004). Hypotonia in infancy and early childhood was accompanied by motor, speech, and mental delays and was followed by development of spasticity, dystonia, and other involuntary distal hand movements. Dumitrescu et al. (2004) reported rotary nystagmus, disconjugate eye movements, and feeding difficulties in two affected boys from different kindreds, findings that were not noted in the other reports or in the families with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome.

Assessments of thyroid function in males with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome showed, in most cases, high free triiodothyronine (T3) and low free T4 levels in serum (fig. 2). Serum TSH levels were normal. The alterations in free T3 and free T4 levels provide a convenient method of selecting males for MCT8 mutational studies. Since an elevated free T3 level in serum is found more consistently than is a low free T4 level (fig. 2), measurement of serum free T3 levels would be the preferred method for screening high-risk populations, such as children with developmental delay and hypotonia.

The paucity of findings that suggest a disturbance in thyroid metabolism is perplexing. Specifically, affected males fail to show the somatic findings typical of hypothyroidism, such as prolonged neonatal jaundice, myxedematous skin changes, macroglossia, hoarseness, and umbilical hernias. Statural growth may be stunted but not as notably as in hypothyroidism. The overall weakness, pale cool skin, dry hair, and constipation in a number of affected males may be related to decreased thyroid-hormone availability to some tissues. Two affected males had prominent eyes, a finding suggestive of endocrine ophthalmopathy or thyrotoxicosis. Although the repertoire of molecules transported by the monocarboxylate transporter 8 is not known, the abnormal transport of another molecule essential to neurons cannot be ruled out as the disease-causing event (Friesema et al. 2005). Nonetheless, the perturbations in T3 and T4 levels may serve as useful biomarkers to screen for Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome.

It is tempting to speculate that dietary supplementation with T4 or T3 might be beneficial. To date, attempts at therapy with thyroxine administrated during infancy in two cases were unsuccessful in ameliorating the neurological signs (Dumitrescu et al. 2004).

Among the six novel mutations in MCT8 reported here, one (p.S448X) truncates the protein near the end of the eighth TMD, removing the last four TMDs and the cytoplasmic region at the carboxy end of the protein. Another mutation was an in-frame deletion of 3 bp resulting in the removal of one of two adjacent phenylalanines (del F230) in the second TMD. This is predicted to remove a turn region and extend a β-sheet region.

Three missense mutations (V235M, L434W, and L568P) occur in other TMDs of the MCT8 protein. Each alters a highly conserved residue in their respective TMD. The V235M missense alteration is predicted to substitute a coil region and an alpha helix where a turn region would normally exist in the second TMD. The L434W missense mutation in the eighth TMD shortens a prominent β-sheet region and lengthens a coil region. The L568P missense mutation in the last TMD results in the formation of a small beta amphipathic region followed by a small alpha amphipatic region near the cytoplasmic region of the TMD and the removal of a short coil section at the end of the TMD. A fourth missense mutation, S194F, occurs within the first extracellular region of the protein, between the first and second TMDs. This alteration would appear to eliminate a β-sheet region, forming a coiled region instead.

The prevalence of MCT8 mutations as a cause of XLMR is not known. With the rapid identification of mutations in 16 families (Dumitrescu et al. 2004; Friesema et al. 2004: Lenzner et al. 2004; the present study), it is possible that MCT8 mutations may number among the more prevalent mutations on the X chromosome (e.g., mutations in FMR1, MECP2, RSK2, ARX, and L1CAM) that cause mental retardation. Studies of other families with XLMR linked to Xq13.2 and sporadic males with mental retardation will be necessary to determine the prevalence.

Expression in females is doubtful but has not been studied systematically or longitudinally. Dumitrescu et al. (2004) noted that some carrier females have abnormal thyroid hormone tests. Four of 16 carrier females in the six families with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome reported a history of thyroid disease. Three had thyroid nodules in adult life, and one had hypothyroidism. Both thyroid nodules and hypothyroidism are common thyroid-related findings in adults. One carrier female (III-2 in K8225) had borderline low free T4 levels, and seven other carrier females had normal thyroid hormone levels (table 2). X-inactivation studies in 20 female gene carriers, aged 18–78 years, from the six kindreds with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome showed no consistent pattern. Only one carrier had markedly skewed X-inactivation (>90% of cells having the same X chromosome active).

With the identification of mutations in MCT8 as responsible for Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome, the gene defects have been found for all XLMR syndromes described before fragile X syndrome (Lubs 1969). Three of the early reports were descriptions of fragile X syndrome mutation in FMR1, as later confirmed by cytogenetic and molecular testing in each of these families (Martin and Bell 1943; Losowsky 1961; Dunn et al. 1962–1963). Other XLMR syndromes described between 1868 and 1969 for which the gene defect is known include Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), Pelizaeus-Merzbacher syndrome (PLD), dyskeratosis congenita (DKC), Hunter syndrome (IDS), incontinentia pigmenti (NEMO), Norrie panophthalmia syndrome (NDP), X-linked hydrocephaly spectrum (L1CAM), Renpenning syndrome (PQBP1), and Snyder-Robinson syndrome (SMS). This is indicative of the progress in the molecular delineation of XLMR syndromes. Among 165 XLMR syndromes, the responsible gene has been identified in 78 syndromes, regional mapping has been achieved for an additional 53 syndromes, and 34 syndromes have not been mapped.

Acknowledgments

Foremost, we thank the members of all the families for their cooperation, with special appreciation for K8005, the family originally described in 1944 by William Allan, Nash Herndon, and Florence Dudley. Their continued interest in the efforts of doctors and researchers to identify the gene for Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome has spanned 60 years. We thank Cindy Skinner for coordinating the sample collection, Tonya Moss for the tissue-culture work, Dana Shultz for assisting with sequence analysis, and all the fellows and technologists who contributed to the project since 1990. This work was supported by grant HD 26202 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (to C.E.S.) and in part by a grant from the South Carolina Department of Disabilities and Special Needs. Dedicated to the memory of Ethan Frances Schwartz, 1996–1998.

Web Resources

The URL for data presented herein is as follows:

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome)

References

- Allan W, Herndon CN, Dudley FC (1944) Some examples of the inheritance of mental deficiency: apparently sex-linked idiocy and microcephaly. Am J Ment Defic 48:325–334 [Google Scholar]

- Bialer MG, Lawrence L, Stevenson RE, Silverberg G, Williams MK, Arena JF, Lubs HA, Schwartz CE (1992) Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome: clinical and linkage studies on a second family. Am J Med Genet 43:491–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JG, Silverberg G, Williams MK, Spiro A, Shapiro LR (1981) A new X-linked recessive mental retardation syndrome with progressive spastic quadriparesis. Am J Hum Genet Suppl 33:A75 [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu AM, Liao X-H, Best TB, Brockmann K, Refetoff S (2004) A novel syndrome combining thyroid and neurological abnormalities is associated with mutations in a monocarboxylate transporter gene. Am J Hum Genet 74:168–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn HG, Renpenning H, Gerrard JW, Miller JR, Tabata T, Federoff S (1962–1963) Mental retardation as a sex-linked defect. Am J Ment Defic 67:827–848 [Google Scholar]

- Friesema ECH, Grueters A, Biebermann H, Krude H, von Moers A, Reeser M, Barrett TG, Mancilla EE, Svensson J, Kester MH, Kuiper GG, Balkassmi S, Uitterlinden AG, Koehrle J, Rodien P, Halestrap AP, Visser TJ (2004) Association between mutations in a thyroid hormone transporter and severe X-linked psychomotor retardation. Lancet 364:1435–1437 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesema ECH, Jansen J, Visser TJ (2005) Thyroid hormone transporters. Biochem Soc Trans 33:228–232 10.1042/BST0330228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzner S, Rosenkranz MD, Grueters A, Biebermann H, Chelly J, Moraine C, Frijns J, van Bokhoven H, Visser T, Ropers H (2004) Severe X-linked mental retardation caused by mutations in the gene for the thyroid hormone transporter MCT8. Paper presented at the European Society of Human Genetics Concurrent Symposia, Munich, June 12–15 [Google Scholar]

- Losowsky MS (1961) Hereditary mental defect showing the pattern of sex influence. J Ment Defic Res 5:60–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubs HA (1969) A marker X chromosome. Am J Hum Genet 21:231–244 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JP, Bell J (1943) A pedigree of mental defect showing sex-linkage. J Neurol Psychiatr 6:154–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugier-Veber P, Munnich A, Bonneau D, Rozet JM, Le Merrer M, Gil R, Boespflug-Tanguy O (1994) X-linked spastic paraplegia and Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease are allelic disorders at the proteolipid protein locus. Nat Genet 6:257–262 10.1038/ng0394-257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Ulmer J, Brown A, Pancoast I, Goodman HO, Stevenson RE (1990) Allan-Herndon syndrome. II. Linkage to DNA markers in Xq21. Am J Hum Genet 47:454–458 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RE, Goodman HO, Schwartz CE, Simensen RJ, McLean WT Jr, Herndon CN (1990) Allan-Herndon syndrome. I. Clinical studies. Am J Hum Genet 47:446–453 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RE, Schwartz CE (2002) Clinical and molecular contributions to the understanding of X-linked mental retardation. Cytogenet Genome Res 99:265–275 10.1159/000071603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RE, Schwartz CE, Schroer RJ (2000) X-linked mental retardation. Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Vits L, Van Camp G, Coucke P, Fransen E, De Boulle K, Reyniers E, Korn B, Poustka A, Wilson G, Schrander-Stumpel C, Winter RM, Schwartz C, Willems PJ (1994) MASA syndrome is due to mutations in the neural cell adhesion gene L1CAM. Nat Genet 7:408–413 10.1038/ng0794-408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorick TS, Kleimann S, Sertié A, Zatz M, Rosenberg S, Passos-Bueno MR (2004) Fine mapping and clinical reevaluation of a Brazilian pedigree with a severe form of X-linked mental retardation associated with other neurological dysfunction. Am J Med Genet 127A:321–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]