Abstract

Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5)-positive dermatomyositis (DM) is often complicated by rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease (RP-ILD), leading to early mortality. Previous studies on the pathogenesis of anti-MDA5-positive DM highlighted type I interferons (IFNs), while recent investigations reported the significance of a type III IFN, IFN-λ3. We investigated a range of cytokines, including type I/II/III IFNs, in serum samples from anti-MDA5-positive DM patients collected at diagnosis before treatment introduction. Elevations of IFN-β and λ3 were identified as the hallmark of anti-MDA5-positive DM, in comparison with other myositis subtypes, systemic lupus erythematosus, and COVID-19 pneumonia. The elevation of IFN-λ3 was associated with decreased CD56dimCD16pos NK cells in circulation. The unique cytokine profile with type I/III IFN upregulation in anti-MDA5-positive DM was replicated in independent validation cohorts. A cluster analysis using serum type I/III IFN levels identified three subgroups in anti-MDA5-positive DM: mild elevations of IFN-α/β and λ3; a marked increase in IFN-λ3 alone; and pronounced elevations of IFN-α/β with mild to moderate increase in IFN-λ3. Patients in the cluster with a marked elevation of IFN-λ3 alone tended to present with RP-ILD and decreased survival. The combination of serum type I/III IFN levels could serve as a prognostic biomarker in anti-MDA5-positive DM.

Keywords: Dermatomyositis, Interstitial lung disease, Autoantibodies, MDA5, Interferon lambda, NK cells

Subject terms: Immunology, Biomarkers, Pathogenesis, Rheumatology

Introduction

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a major subtype of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) characterized by skin rash and skeletal muscle inflammation, which also affects extra-muscular organs including the heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tracts, and joints1. Myositis-specific autoantibodies (MSAs) identified in the circulation of patients with IIM are mutually exclusive and associated with distinct clinical features, therefore extremely useful for disease subclassification and prognostication2–4. Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) antibodies are associated with DM and interstitial lung disease (ILD) in adults and children5,6. Patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM often develop rapidly progressive ILD (RP-ILD), particularly in Asian populations, leading to early mortality7,8.

The pathogenesis of anti-MDA5-positive DM remains largely unknown, while numerous studies found a correlation between this unique IIM subset and elevated circulating levels of a variety of inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, IL-10, monocyte chemoattract protein 1 (MCP-1), and interferon-γ inducible protein 10 kDa (IP-10)9. Recent studies have shown a crucial role of type I interferons (IFNs) in the pathogenesis of anti-MDA5-positive DM. Specifically, Ye et al. performed a single-cell RNA sequence technique in circulating B and T cells of patients with anti-MDA5 antibodies and identified overactivation of type I IFN signaling as the hallmark of the disease10. He et al. also applied single-cell RNA sequence to peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from anti-MDA5-positive DM patients and found an overstimulated type I IFN response and antiviral immunity in both innate and adaptive immune cells11. We previously performed integrated miRNA-mRNA association analysis using circulating CD14+ monocytes from patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM and identified toll-like receptors (TLRs) and IFN-β as the upstream regulators, while the downstream effect converged at the inhibition of viral infection12.

Although the investigations on the pathogenesis of anti-MDA5-positive DM are centered on type I IFNs, several studies have also reported a dysregulated production of IFN-γ, a type II IFN, in the disease13. Recently, striking similarities in clinical presentation, disease course, adverse outcomes, and underlying conditions of ‘cytokine storm’ between RP-ILD associated with anti-MDA5-positive DM and severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia have gained attention14. In severe COVID-19, serum IFN-λ3, a type III IFN, is elevated in the early disease course and is useful as a prognostic biomarker for worse survival15,16. Interestingly, an increased level of IFN-λ3 in circulation was detected exclusively in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM among those with IIM-associated ILD and was associated with poor prognosis17.

In this context, we assessed type I/II/III IFNs comprehensively and explored a characteristic serum cytokine profile in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM, in comparison with other systematic autoimmune rheumatic diseases (SARDs) and COVID-19 pneumonia. In addition, we investigated whether peripheral blood immune cells are the major producers of IFNs and inflammatory cytokines by immunophenotyping of PBMCs using flow cytometry (FCM) and by visualizing the nuclear translocation of transcription factors responsible for IFN/cytokine production. Finally, we aimed to stratify clinical phenotypes and outcomes of patients with anti-MDA5 antibodies using serum IFN levels.

Results

Distinct cytokine profile with elevated type I/III IFNs in circulation of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM

Our discovery cohort in Nippon Medical School Hospital (NMSH) included consecutive patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM (n = 10) and disease controls consisting of anti-synthetase syndrome (ASSD) (n = 6), anti-transcription intermediary factor 1-γ (TIF1-γ)-positive DM (n = 6), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (n = 6), and COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 3) (Fig. 1). All peripheral blood samples were obtained at diagnosis before treatment introduction. Samples obtained from five individuals without a diagnosis of SARDs were used as healthy controls (HCs). In patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM, the median age was 57 years [interquartile range (IQR) 48–68] and 80% were female (Supplementary Table S1). Of these, nine were classified as amyopathic DM (ADM) according to the 2017 European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for IIMs18. All the 10 patients had ILD and two were complicated with RP-ILD.

Fig. 1.

Overview of study cohorts and workflow. ASSD anti-synthetase syndrome, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, DCs dendritic cells, FACS fluorescence activated cell sorting, FCM flowcytometry, HC healthy control, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, IP-10 interferon-γ inducible protein 10 kDa, IRF interferon regulatory factor, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattract protein 1, MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, NF-κB nuclear factor-κB, NK cells natural killer cells, NMSH Nippon Medical School Hospital, PBMC peripheral blood mononuclear cells, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, TIF1-γ transcriptional intermediary factor 1-γ, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α.

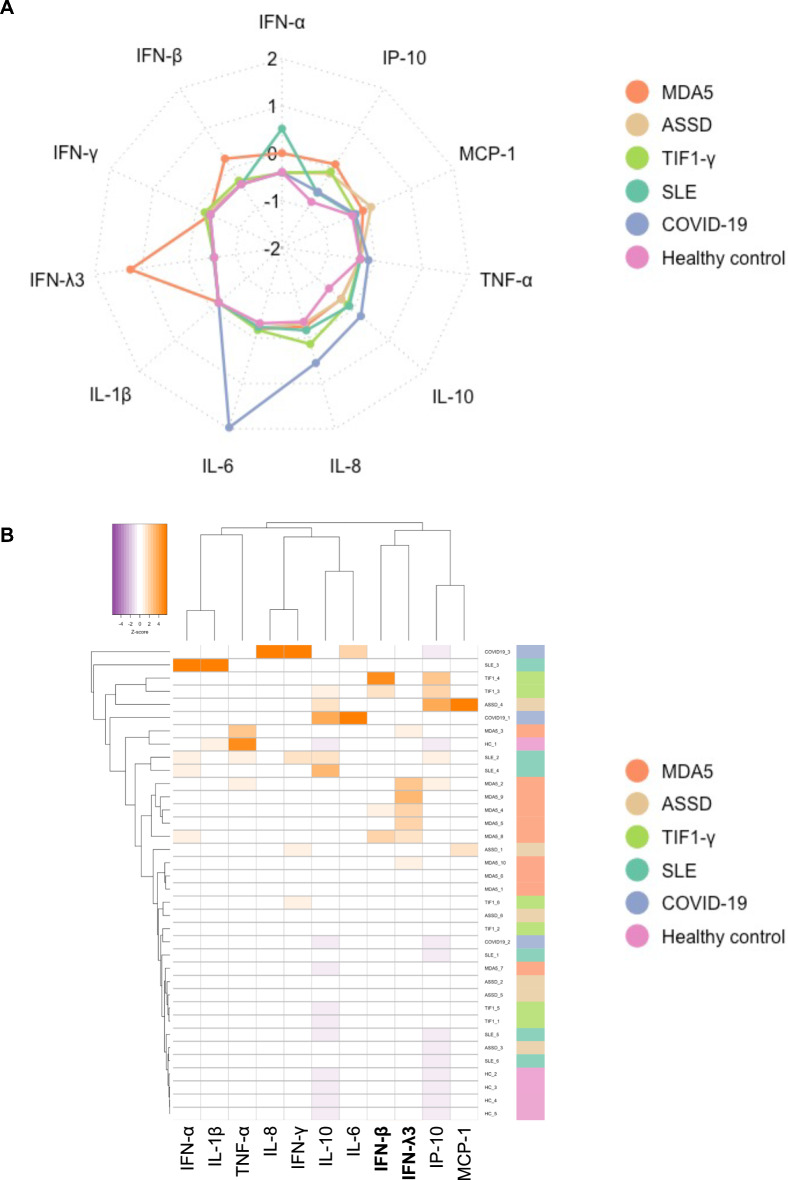

We measured serum cytokine levels using cytometric bead array (CBA) and enzyme immunoassays (EIA) (Fig. 2). The median levels of IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-10, and TNF-α were below the detection limit of the assay range (10 pg/mL) in all groups. The median levels of serum IFN-β, IFN-λ3, IL-6, and IP-10 were higher in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM than in HCs (adjusted P = 0.025, 0.008, 0.010, and 0.010, respectively). We also noted an elevation of IFN-α in anti-MDA5-positive DM as compared to ASSD and anti-TIF1-γ-positive DM (both adjusted P = 0.027), while the median level was the highest in SLE. Contrarily, IFN-β levels were higher in anti-MDA5-positive or anti-TIF1-γ-positive DM patients than in other subsets. It was noteworthy that IFN-λ3 was strikingly elevated in all the patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM, with the median level being even higher than the levels observed in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. A radar chart (Fig. 3A) and a heatmap (Fig. 3B) highlighted the elevations of IFN-β and λ3 as the hallmark of anti-MDA5-positive DM, whereas COVID-19 pneumonia was characterized by the elevations of IL-6 and IL-8.

Fig. 2.

Elevations of IFN-β and λ3 levels in the circulation of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM. *Adjusted P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared to HCs. ASSD anti-synthetase syndrome, COVID coronavirus disease 2019, HC healthy control, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, IP-10 interferon-γ inducible protein 10 kDa, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattract protein 1, MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, TIF1-γ transcriptional intermediary factor 1-γ, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α.

Fig. 3.

Distinct cytokine profile with elevated type I/III IFNs in the circulation of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM. (A) A radar chart and (B) a heatmap depicting characteristic serum cytokine profiles of each disease group. The serum levels of each cytokine were standardized using Z-scores before they were subjected to the analyses. ASSD anti-synthetase syndrome,; COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, HC healthy control, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, IP-10 interferon-γ inducible protein 10 kDa, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattract protein 1, MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, TIF1-γ transcriptional intermediary factor 1-γ, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α.

Altered monocyte and NK cell phenotypes in circulation specific to anti-MDA5-positive DM

Next, we performed multicolor FCM on PBMCs collected from patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM as well as disease and healthy controls in the derivation cohort. Supplementary Fig. 1 presents our gating strategy, where we focused on B cells, monocytes, dendritic cells (DCs), and natural killer (NK) cells that were collected by a sorting technique for subsequent immunocytochemistry (ICC) analysis. A significant increase in the median proportion of CD14++CD16+ (intermediate) monocytes was found in anti-MDA5-positive DM patients as compared to HCs (adjusted P = 0.023) (Fig. 4A,B). The median proportion of CD14++CD16- (classical) monocytes was also numerically higher in anti-MDA5-positive DM patients than in HCs (adjusted P = 0.298). A similar trend was observed in anti-TIF1-γ-positive DM patients. Notably, anti-MDA5-positive DM patients demonstrated a decrease in the median proportions of CD56brightCD16neg NK cells and CD56dimCD16pos NK cells as compared to HCs (CD56brightCD16neg NK: adjusted P = 0.035; CD56dimCD16pos NK: adjusted P = 0.095). In line with this, the median proportion of CD56dimCD16pos NK cells appeared the lowest in anti-MDA5-positive DM patients among all groups. When the proportions of monocyte and NK cell subsets were analyzed within the monocyte or NK cell subpopulations instead of PBMCs, we observed a significant increase in the median proportions of intermediate monocytes (adjusted P = 0.040) and CD56dimCD16neg NK cells (adjusted P = 0.036) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Taken together, the FCM results highlighted altered proportions of monocyte and NK cell subpopulations, where the alteration of NK cell phenotype appeared more specific to anti-MDA5-positive DM.

Fig. 4.

Altered phenotypes of monocyte and NK cells in the circulation of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM. (A) Proportions of immune cell subsets in PBMCs of patients and controls in the discovery cohort. (B) Representative flow cytometry results highlighting an increased proportion of CD14++CD16+ monocytes (upper panels) and decreased proportions of CD56brightCD16neg NK cells and CD56dimCD16pos NK cells (lower panels). *Adjusted P < 0.05 compared to HCs. ASSD anti-synthetase syndrome, COVID coronavirus disease 2019, DC dendritic cells, HC healthy control, MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, NK natural killer cells, PBMC peripheral blood mononuclear cells, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, TIF1-γ transcriptional intermediary factor 1-γ.

Nuclear translocation of IRFs and NF-κB p65 in immune cell subpopulations

To investigate whether peripheral blood immune cells are the major producers of IFNs and inflammatory cytokines, we employed ICC to visualize the nuclear translocation of transcription factors responsible for IFN/cytokine production, including interferon regulatory factors (IRF) 3, IRF7, and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) p65, using sorted specific immune cell subsets (Supplementary Fig. S3). Specifically, we evaluated the nucleus/cytoplasm mean fluorescence intensity as a measure for nuclear translocation of the transcription factors. We successfully distinguished cells where transcription factors were undergoing nuclear translocation (Supplementary Fig. S3A); however, the analyses were hindered by missing data due to the insufficient numbers of sorted cells available for the ICC, especially for non-classical monocytes and DCs. Besides this shortcoming, there was no statistically significant difference in the level of nuclear translocation between anti-MDA5-positive DM, disease controls, and HCs (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

Elevations of serum IFN-λ3 levels correlated with decreased proportions of circulating CD56dimCD16pos NK cells in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM

In patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM included in the discovery cohort, the levels of IFN-α and β showed a strong correlation (Spearman’s r = 0.927, adjusted P = 0.003), while the levels of IFN-λ3 were independent of type I IFN levels (Fig. 5A). Rather, the levels of IFN-λ3 correlated with the levels of IL-8 (Spearman’s r = 0.867, adjusted P = 0.011), which were correlated with serum anti-MDA5 antibody levels (Spearman’s r = 0.867, adjusted P = 0.011). There was a trend toward a correlation between the levels of IFN-λ3 and anti-MDA5 antibody levels without statistical significance (Spearman’s r = 0.576, adjusted P = 0.082). The levels of IP-10 correlated with those of type I IFNs (IFN-α: Spearman’s r = 0.855, adjusted P = 0.011; IFN-β: Spearman’s r = 0.806, adjusted P = 0.027). Of note, correlation analyses of serum cytokine levels and immune cell subset proportions in PBMCs revealed a significant negative correlation between serum levels of IFN-λ3 and the proportion of CD56dimCD16pos NK cells (Spearman’s r = − 0.879, adjusted P = 0.040) (Fig. 5B). Notably, two anti-MDA5-positive DM patients with substantial elevations of serum IFN-λ3 experienced poor outcomes, including relapse and early death (MDA5_2 and 9, in Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Elevations of serum IFN-λ3 levels correlated with decreased proportions of CD56dimCD16pos NK cells in circulation and poor outcome in anti-MDA5-positive DM. (A) Correlation of serum IFN, inflammatory cytokine, and anti-MDA5 antibody levels. (B) Longitudinal analysis of type I/III IFN levels. (C) Correlation of immune cell subset proportions (%PBMC) and serum IFN levels. (D) Association of immune cell subset populations (%PBMC), serum IFN levels, and clinical features. The serum levels of each cytokine and the proportions of each immune subset (%PBMC) were standardized using Z-scores before they were subjected to the analyses. *Adjusted P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ADM amyopathic DM, C-Mono classical monocytes, DC dendritic cells, DM dermatomyositis, FCM flow cytometry, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, I-Mono intermediate monocytes, IP-10 interferon-γ inducible protein 10 kDa, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattract protein 1, MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, NC-Mono non-classical monocytes, NK natural killer cells, PBMC peripheral blood mononuclear cells, RP-ILD rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease.

Serial measurement of serum type I/III IFNs in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM

In the discovery cohort of 10 patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM, we assessed the longitudinal changes in type I/III IFN levels using prospectively collected serum samples obtained at one and 12 months after treatment introduction (Fig. 5D). Serum levels of IFN-α and β declined in all the patients; however, we noted a sustained elevation of serum IFN-λ3 in a treatment-refractory case who deceased two months after diagnosis despite an up-front triple combination therapy with glucocorticoids, tacrolimus, and intravenous cyclophosphamide (MDA5_9, gray line in Fig. 5D).

Validation of unique cytokine profiles with elevations of type I/III IFNs in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM

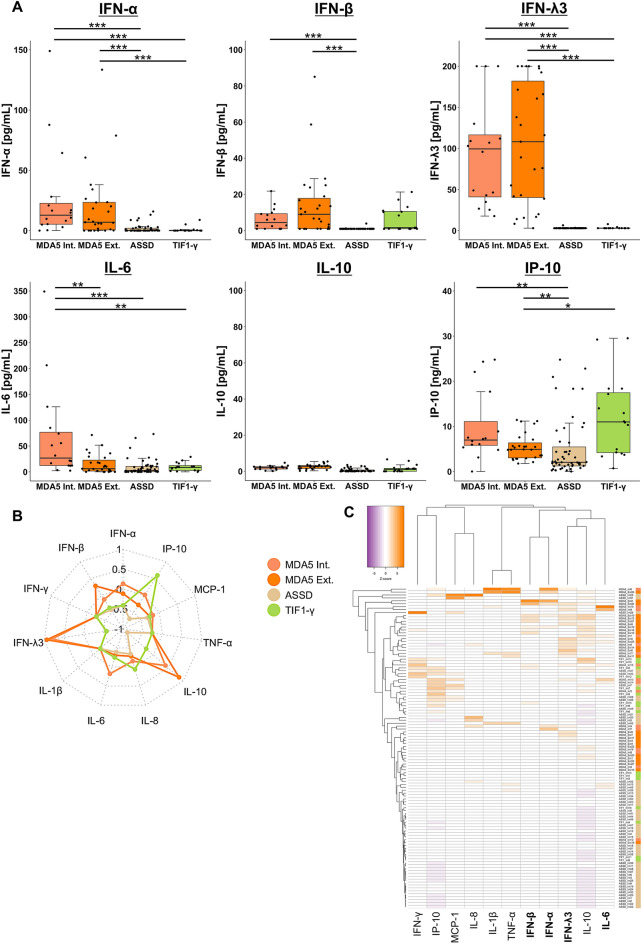

We then validated the cytokine profile related to anti-MDA5-positive DM using an independent validation cohort of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM, anti-TIF1-γ-positive DM, and ASSD from NMSH (internal validation cohort) and anti-MDA5-positive DM patients from Hamamatsu University Hospital (external validation cohort) (Fig. 6). The median levels of serum IFN-α and λ3 in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM in both cohorts were higher than in those with ASSD or anti-TIF1-γ-positive DM in the internal validation cohort (all adjusted P < 0.001) (Fig. 6A). The median levels of IFN-β and IP-10 were also higher in anti-MDA5-positive DM in both cohorts than in those with ASSD (IFN-β: both adjusted P < 0.001; IP-10: both adjusted P = 0.007). The elevations of type I/III IFN levels in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM were consistent between internal and external validation cohorts, whereas the increased levels of IL-6 were observed only in the internal validation cohort. The median levels of other cytokines were comparable between the groups or below the lower limit of the assay range (10 pg/mL) in most cases (Supplementary Fig. S4). A radar chart (Fig. 6B) and a heatmap visualization (Fig. 6C) demonstrated the unique cytokine profile with elevated type I/III IFNs in anti-MDA5-positive DM, replicating the observation in the derivation cohort.

Fig. 6.

Validation of the specific cytokine profile with elevations of type I/III IFNs in anti-MDA5-positive DM. (A) Serum levels of type I/III IFNs, IL-6, IL-10, and IP-10 in patients included in the internal (MDA5, ASSD, TIF1-γ) and external (MDA5) validation cohorts. (B) A radar chart and (C) a heatmap depicting distinct serum cytokine profiles of each group. The serum levels of each cytokine were standardized using Z-scores before they were subjected to the analyses. *Adjusted P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. ASSD anti-synthetase syndrome, DM dermatomyositis, Ext. external validation, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, Int. internal validation, IP-10 interferon-γ inducible protein 10 kDa, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattract protein 1, MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, TIF1-γ transcriptional intermediary factor 1-γ, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-α.

Performance of biomarkers on mortality prediction in anti-MDA5-positive DM

Additionally, we applied Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis to evaluate the performance of serum type I/III IFN levels in comparison with other serum biomarkers, including IL-6, ferritin, anti-MDA5 antibody levels, and respiratory status as assessed by PaO2/FiO2 ratio, in the combined cohort of anti-MDA5-positive DM (n = 53) (Supplementary Fig. S5). IFN-λ3 demonstrated a fair performance on mortality prediction with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.709 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.532–0.887]. The performance of IFN-λ3 was comparable to IL-6, ferritin, and anti-MDA5 antibody levels. Meanwhile, IFN-α and IFN-β failed to show utility in predicting mortality, with an AUC of 0.532 [95% CI 0.340–0.725] and 0.446 [95%CI 0.268–0.624], respectively. PaO2/FiO2 ratio demonstrated excellent performance with the highest AUC among the variables assessed (0.932 [95% CI 0.864–0.999]).

Clustering of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM using serum levels of type I /III IFNs

Finally, we combined all 53 patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM, including internal discovery/validation cohorts and external validation cohorts, and conducted an unsupervised cluster analysis using the serum levels of IFN-α, β, and λ3 as variables. As a result, we identified three distinct clusters: Cluster 1 (n = 24) characterized by mild elevations of both types I and III IFNs; Cluster 2 (n = 13) with a significant increase in IFN-λ3 alone; and Cluster 3 (n = 16) exhibiting an elevation of type I IFNs with mild to moderate elevations of IFN-λ3 (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Mortality risk stratification of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM using serum type I/III IFN levels. (A) Cluster analysis using serum type I/III IFN levels identified three clusters in anti-MDA5-positive DM. (B) Overall survival of patients included in each cluster. DM dermatomyositis, IFN interferon, MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5.

When clinical characteristics were compared among clusters (Table 1), patients in Cluster 2 were older at diagnosis (P = 0.020), while arthralgia/arthritis was more common in Cluster 3 (P = 0.023). The prevalence of muscle weakness was numerically higher in Cluster 3 (P = 0.078), which was associated with higher serum levels of CPK (P = 0.048) and aldolase (P = 0.025). The prevalence of RP-ILD was numerically higher (P = 0.131) and the ratio of SpO2/FiO2 at diagnosis was the lowest (P = 0.004) in patients included in Cluster 2, leading to a trend toward poorer survival compared with those in other clusters (vs. Cluster 1: hazard ratio (HR) 1.95 [95% CI 0.56–6.74], adjusted log-rank P = 0.426; vs. Cluster 3: HR 3.75 [95%CI 0.73–19.36], adjusted log-rank P = 0.271) (Fig. 7B).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM in each cluster.

| Cluster 1 (n = 24) | Cluster 2 (n = 13) | Cluster 3 (n = 16) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years | 52 [45–66] | 66 [59–69] | 48 [43–56] | 0.020 |

| Female | 17 (70.8) | 11 (84.6) | 11 (68.8) | 0.669 |

| Clinical diagnosis | 0.106 | |||

| DM | 8 (33.3) | 2 (15.4) | 9 (56.2) | |

| ADM | 15 (62.5) | 11 (84.6) | 7 (43.8) | |

| IPAF | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 0 | |

| Heliotrope rash | 8 (33.3) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (31.2) | 0.366 |

| Gottron’s sign/papules | 23 (95.8) | 13 (100) | 16 (100) | 1.000 |

| Palmar papules | 14/19 (73.7) | 6/7 (85.7) | 12/12 (100) | NA |

| Skin ulcer | 7 (29.2) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (31.2) | 0.928 |

| Muscle weakness | 8 (33.3) | 2 (15.4) | 9 (56.2) | 0.078 |

| Arthralgia/arthritis | 11 (45.8) | 3 (23.1) | 12 (75.0) | 0.023 |

| Fever | 10 (41.7) | 6 (46.2) | 7 (43.8) | 1.000 |

| Malignancy | 3 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.322 |

| ILD | 23 (95.8) | 13 (100) | 16 (100) | 1.000 |

| ILD onset | 0.472 | |||

| Acute | 9 (37.5) | 9 (69.2) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Subacute | 5 (20.8) | 2 (15.4) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Chronic | 4 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Unclassifiable | 5 (20.8) | 0 | 2 (12.5) | |

| RP-ILD | 7 (29.2) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (31.2) | 0.131 |

| SpO2/FiO2 | 461.9 [455.9–463.1] (n = 20) | 447.6 [433.3–452.4] (n = 12) | 454.8 [447.6–461.9] (n = 14) | 0.004 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 385.7 [282.7–433.6] | 346.2 [330.5–404.8] | 402.4 [337.3–453.1] | 0.226 |

| A-aDO2 | 19.4 [12.6–46.1] (n = 19) | 28.9 [25.1–35.4] (n = 7) | 20.7 [5.6–33.7] (n = 12) | NA |

| CK, U/L | 87 [48–121] | 111 [64–152] | 158 [116–294] | 0.048 |

| Ald, U/L | 8.0 [5.7–10.6] (n = 22) | 5.6 [4.6–6.5] | 8.4 [6.6–9.0] | 0.025 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.30 [0.09–0.95] | 1.02 [0.40–2.10] | 0.32 [0.23–1.40] | 0.126 |

| KL-6, U/mL | 643.0 [405.8–849.2] (n = 23) | 624.7 [400.4–729.6] | 716.0 [433.6–798.0] | 0.947 |

| SP-D, ng/mL | 77.7 [43.4–102.5] (n = 23) | 74.1 [41.4–99.1] | 72.2 [41.9–91.0] | 0.807 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 353.5 [156.7–729.8] | 315.0 [207.0–889.0] | 377.3 [222.6–964.4] | 0.825 |

| Anti-MDA5 level, index | 1332 [790–3570] (n = 14) | 2835 [1765–4023] (n = 5) | 2030 [1450–3445] (n = 9) | NA |

| Pulse methylprednisolone | 19 (79.2) | 10 (76.9) | 14 (87.5) | 0.740 |

| Initial treatment regimen | 0.634 | |||

| Dual combination* | 12 (50.0) | 4 (30.8) | 7 (43.8) | |

| Triple combination** | 10 (41.7) | 9 (69.2) | 9 (56.2) | |

Continuous variables and categorical variables are presented as median [IQR] and n (%), respectively.

We did not perform statistical analysis for variables with more than 10% missing data.

*Glucocorticoids plus single immunosuppressive agent (TAC, CYA, IVCY, or MMF).

**Glucocorticoids plus calcineurin inhibitors (TAC or CYA) plus IVCY.

A-aDO2 alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient, ADM amyopathic dermatomyositis, Ald aldolase, CK creatinine phosphokinase, CRP C-reactive protein, CYA cyclosporin A, DM dermatomyositis, FiO2 fraction of inspired oxygen, ILD interstitial lung disease, IPAF idiopathic pneumonia with autoimmune features, IQR interquartile range, IVCY intravenous cyclophosphamide, JAK Janus kinase, KL-6 Krebs von den Lungen-6, MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, mPSL methylprednisolone, NA not applicable, PaO2 partial pressure of oxygen, RP-ILD rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease, RTX rituximab, SP-D surfactant protein-D, SpO2 saturation of percutaneous oxygen, TAC tacrolimus.

Discussion

This study assessed type I/II/III IFNs comprehensively in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM using prospectively collected pre-treatment serum samples, in comparison with other IIM subtypes, SLE, and COVID-19 pneumonia. We identified the elevations of IFN-β and λ3 as a hallmark of anti-MDA5-positive DM. The elevation of serum IFN-λ3 levels was associated with a specific immunophenotype, a decrease in the proportion of CD56dimCD16pos NK cells. The characteristic serum cytokine profile with elevations of type I/III IFNs was validated in both internal and external validation cohorts, where we also identified IFN-α as a discriminating cytokine that differentiates between anti-MDA5-positive DM and other IIM subtypes, consistent with previous studies19,20. However, in the ROC analysis, serum levels of IFN-λ3, but not IFN-α or IFN-β, demonstrated a fair performance on predicting mortality in anti-MDA5-positive DM, which was comparable to other established serum biomarkers such as IL-6, ferritin, and anti-MDA5 antibody levels. Furthermore, a cluster analysis using serum IFN-α, β, and λ3 levels as variables identified three clusters with potentially different clinical phenotypes of anti-MDA5-positive DM. Of note, patients in the cluster with a marked elevation of IFN-λ3 alone (Cluster 2) tended to present with RP-ILD and decreased survival. Cluster 2 was associated with older age at diagnosis and lower prevalence of arthritis and muscle involvement, which mirrors the characteristic of the “RP-ILD cluster” identified in the French multicenter cohort of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM reported by Allenbach et al.21. The elevations of IFN-λ3, but not type I IFNs, might be useful to predict the devastating subset with RP-ILD and poor survival, although this needs to be validated in a larger multicenter cohort.

IFN-λs, type III IFNs, are produced in response to viral infection along with type I IFNs to induce an antiviral state in infected and yet uninfected cells to inhibit viral replication and prevent the spread of infection22. IFN-λs were initially described as a specialized system to maintain the immune defense at epithelial barrier surfaces; however, recent evidence also suggests that IFN-λs have complex effects on both innate and adaptive immunity and might be involved in pathogenesis in SARDs23,24. In humans, type III IFNs comprise four subtypes: IFN-λ1 (IL-29), IFN-λ2 (IL-28A), IFN-λ3 (IL-28B), and IFN-λ4. Of these, it has been reported that only IFN-λ3 was elevated exclusively in patients with anti-MDA5 antibodies among patients with IIM-ILDs17. Our results highlighted that serum levels of IFN-λ3 were elevated in all patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM and were even higher than the levels in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. The cluster analysis revealed an increased mortality in patients with isolated elevation of IFN-λ3 as compared to those with elevations of both type I and III IFNs, suggesting that IFN-λ3, not type I IFNs, could be the key driver of pathogenesis in anti-MDA5-positive DM. In addition, the persistent elevation of IFN-λ3 despite combined immunosuppressive treatments in a treatment-refractory case further supported the pathogenic roles of IFN-λ3 rather than IFN-α or β. Furthermore, IFN-λ3 levels strongly correlated with IL-8, not with type I IFNs, and IL-8 levels were strongly correlated with anti-MDA5 antibody levels. These results are consistent with previous reports highlighting IL-8 and anti-MDA5 antibody levels as a prognostic factor or disease activity marker in this disease entity9,25. From a clinical point of view, circulating IFN-λ3 may serve as a predictive biomarker as well as an activity biomarker in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM. In Japan, the measurement of serum IFN-λ3 levels by chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA)26 has already been commercialized and covered by health insurance for patients with COVID-19. The results are reported in 2–4 days, which highlights the potential utility of serum IFN-λ3 levels as a biomarker to promptly predict mortality risk and decide the treatment intensity in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM.

Recent studies reported the overexpression of type I IFN stimulated genes (ISGs) in both peripheral blood immune cells and the affected lungs10,11 and the association of type I IFN scores and disease activity in patients with anti-MDA5 antibodies27. Given that type I and III IFNs both signal through the Janus Kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway and share downstream signaling machinery to induce the transcription of ISGs24, what we have observed as “type I IFN stimulated gene signature” in anti-MDA5-positive DM could be induced by IFN-λ3 at least to a certain extent. The transcriptional profiles induced by type I and III IFNs exhibit substantial overlap, and a unique signature for type III IFNs has not been identified28. Meanwhile, distinct biological responses from type I and III IFNs can result from differences in the magnitude and kinetics of signaling and the types of cells responsive to type I versus III IFNs; IFN-α receptor is widely expressed on almost all cell types, whereas the expression of IFN-λ receptor (IFNLR) is limited to epithelial cells and some immune cells such as B cells29. Our findings warrant further studies investigating the downstream effect of IFN-λ3 on each immune cell subset as well as on non-immune cells to reveal the pathophysiology of anti-MDA5-positive DM-ILD.

The expansion of CD14++ monocytes in the circulation of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM is consistent with a recent report by He et al.11. They identified a subset of CD14++ monocytes specific to the disease, which highly expressed IFN alpha-inducible protein 27 (IFI27) and IFN-induced with helicase C domain 1 (IFIH1) genes, suggesting the phenotypic change in CD14++ monocytes could be induced by type I or III IFNs. We also identified a potential association between the elevation of serum IFN-λ3 levels, the decrease in the proportion of CD56dimCD16pos NK cells, and poor outcomes. A recent study on anti-MDA5-positive DM also reported decreased NK cell counts as compared to other IIM subtypes and HCs30. Furthermore, a cluster analysis using 42 immune cell populations identified two distinct clusters with different prognoses in anti-MDA5-positive ADM-ILD, where the decrease in the proportion of CD56dim NK cells was the hallmark of the cluster with high mortality31. Intriguingly, FCM analyses in COVID-19 also identified the expansion of CD56dimCD16neg cells and the concomitant decrease in CD56dimCD16pos cells as a characteristic phenotype of NK cells, and this phenotypic change persisted in severe COVID-1932. Given the similarities of radiological findings on HRCT between anti-MDA5-positive DM-ILD and COVID-19 pneumonia, the phenotypic alterations in NK cells could be explained by the same pathophysiologic mechanism underlying these two disease entities; however, the direct effect of IFN-λ3 on NK cells in circulation is unlikely as IFNLR is not expressed on human NK cells29. Whether NK cells with altered phenotype are involved in the pathogenic process of anti-MDA5-positive DM-ILD needs further investigations; however, recent evidence from COVID-19 studies suggested that the expansion of CD56dimCD16neg NK cells was associated with decreased NK cell cytotoxicity32.

Type I/III IFNs and inflammatory cytokines are induced following the detection of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by endosomal or cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs)28. PRR activation leads to nuclear translocation of transcription factors, including IRFs and NF-κΒ, followed by the increased expression of IFN/cytokines. In the classic model of type I IFN induction, the activation of PRR results in IRF3 nuclear translocation and IFN-β induction33. IFN-β stimulates the first wave of ISG transcription including IRF7, which leads to the expression of multiple IFN-α subtypes and the second wave of ISG transcription. The activation of TLRs and IRF7 is also responsible for IFN-λ3 induction34. Our study aimed to elucidate whether peripheral blood immune cells are the major producers of IFNs and inflammatory cytokines by visualizing the nuclear translocation of IRF3, IRF7, and NF-κΒ p65; however, our analyses were hindered by the insufficient numbers of sorted cells, especially for non-classical monocytes and DCs. Further studies are warranted to identify exogenous or endogenous triggers for IFN-λ3 overproduction and immune cells or possibly non-immune cells that are responsible for the expression of type I/III IFNs and inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of anti-MDA5-positive DM-ILD.

Our study has several limitations. First, CBA might not have enough sensitivity to detect very low levels of IFN-α or IFN-γ in circulation. Future studies should consider utilizing ultrasensitive platforms such as SIMOA19. Furthermore, although IFN-α comprises 13 subtypes, commercial multiplex assays only measure IFN-α2 levels; therefore, the total level of circulating IFN-α could be higher. Second, although this study included internal and external validation cohorts, we were underpowered to detect the statistically significant difference in mortality between the three clusters of anti-MDA5-positive DM. The event rate was also not enough to perform multivariable Cox regression analysis adjusting for potential confounders. Third, given the reported phenotypic heterogeneity of anti-MDA5-positive DM between different races, ethnicities, and geographical regions35, the generalizability of our findings beyond the Japanese cohort remains uncertain. Our results warrant further validation in a larger, international, multicenter cohort of patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM.

In conclusion, the present study highlighted a distinct cytokine profile of anti-MDA5-positive DM, with elevations of IFN-β and λ3. The combination of serum IFN-α, β, and λ3 levels could be used as a prognostic biomarker in patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM. Future studies focusing on the mechanism underlying IFN-λ3 overproduction could unveil the pathogenesis of anti-MDA5-positive DM.

Methods

Cohorts

This study used three cohorts: the derivation and internal validation cohorts from NMSH, and the external validation cohort from the Hamamatsu University Hospital (Fig. 1). For the discovery cohort, we prospectively enrolled consecutive patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM, ASSD, anti-TIF1-γ-positive DM, and SLE from September 2020 to August 2023. As for the internal validation cohort, we enrolled patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM, ASSD, and anti-TIF1-γ-positive DM diagnosed between August 2014 and August 2020 and between September 2023 and September 2024. The external validation cohort included patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM who were diagnosed at the Division of Respiratory Medicine, Hamamatsu University Hospital from July 2014 to February 2021.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients with anti-MDA5-positive DM or anti-TIF1-γ-positive DM met the 2017 EULAR/ACR classification criteria for definite/probable IIMs18, while those with ASSD fulfilled the criteria proposed by Connors et al.: anti-synthetase antibody-positivity plus any one of myositis, ILD, arthritis, unexplained fever, Raynaud’s phenomenon, or mechanic’s hands36. One patient in the internal validation cohort with anti-MDA5-positive ILD lacked apparent myositis or DM-specific skin rashes and was therefore classified as idiopathic pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF)37. Patients with SLE met both the 1997 ACR classification criteria38 and the 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criteria39 and had a moderate or severe disease with an SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI)-2 K score greater than six40. The discovery cohort also included patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, who were admitted to the Emergency Department of NMSH from February to March 2022 and had a moderate or severe disease41. For HCs, we recruited individuals without a diagnosis of SARDs, matched for age and sex with anti-MDA5-positive DM patients.

Anti-MDA5 antibodies were detected using a commercially available enzyme-link immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (MESACUP™, Medical and Biological Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan)42. Anti-synthetase and anti-TIF1-γ antibodies were identified by RNA immunoprecipitation (IP) and IP-immunoblot assay, respectively, as described previously43. Clinical data collected from the medical records of each center are summarized in Supplementary Table S3.

This study obtained approval from the institutional review board of NMSH (B-2020–162) and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Measurement of serum cytokine levels

Serum samples were obtained from each patient at diagnosis before treatment introduction and stored at − 20 °C until use. We measured serum levels of IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, MCP-1, IP-10, using BD™ Cytometric Bead Array (Human CBA FLEX Sets; BD Biosciences, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, serum samples were incubated with a mixture of cytokine capture beads and PE-conjugated antibodies to form sandwich complexes. Data was acquired using the BD FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer and analyzed using the quantification software (FCAP Array™ v3.0; BD Biosciences, NJ, USA) (assay range: 10–2500 pg/mL).

We used an ELISA kit for the measurement of serum IFN-β levels (VeriKine-HS™ Human Interferon-Beta Serum ELISA Kit; PBL Assay Science, NJ, USA). 96-well pre-coated microtiter plate was incubated with patients’ sera and diluted detection antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG and tetramethylbenzidine were used as the secondary antibody and the substrate for visualization, respectively. Serum IFN-β levels (assay range: 1.2–150 pg/mL) were calculated from the optical density at 450 nm with reference to an 8-point standard curve constructed using the serially diluted Human IFN-β Standard provided by the manufacturer. IFN-λ3 was measured using a CLEIA kit (HISCL™ IFN-λ3; Sysmex Corp, Kobe, Japan) as previously described (assay range: 3.0–200 pg/mL)26. The CLEIA kit was demonstrated to have little or no cross-reactivity to IFN-λ1 or IFN-λ2.

Multicolor flow cytometry and cell sorting

In the discovery cohort, we isolated each patient’s PBMCs from heparinized blood collected at diagnosis before treatment initiation by density-gradient centrifugation with Lymphoprep™ (Axis-Shield PoC AS, Oslo, Norway) immediately after the blood draw. PBMCs were stored at − 80 °C until use. For multicolor FCM and cell sorting, 5.0 × 106 cells were incubated with nine fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (Supplementary Table S4). We then performed immunophenotyping of PBMCs and sorted seven immune cell subsets, including B cells, CD14++CD16- (classical) monocytes, CD14++CD16+ (intermediate) monocytes, CD14+CD16+ (non-classical) monocytes, mDC, pDC, and NK cells, using FACSAria™ Fusion (BD Biosciences, NJ, USA), with the aim of 6.0 × 104 cells for each subset. Our gating strategy (Supplementary Fig. S1) aligned with the standardized protocol proposed by the Human Immunophenotyping Consortium44. FCM data was analyzed using FlowJo™ v10 software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, USA; https://www.bdbiosciences.com/en-us/products/software/flowjo-software).

Isolation of neutrophils and T cells

We isolated neutrophils from EDTA whole blood samples of each patient or control in the discovery cohort collected at diagnosis before treatment introduction, using EasySep™ Direct Human Neutrophil Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). The proportion of CD11b+ CD16+ cells in isolated neutrophils was consistently > 99%. CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were separated from PBMCs using Mojosort™ CD4 T Cell Isolation Kit and CD8 T Cell Isolation Kit (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), respectively, according to the instructions by the manufacturer. The proportions of CD3+CD4+ cells and CD3+CD8+ cells in isolated CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were consistently > 90%.

Immunocytochemistry

Sorted or isolated cells were seeded on glass slides by cytospin and were fixed and permeabilized with 100% methanol at − 20 °C for 10 min. The cells were blocked with Normal Serum Block (927503; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) at room temperature (RT) for one hour and were stained with anti-IRF3 rabbit monoclonal antibody (703682; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-IRF7 rabbit polyclonal antibody (GTX55682; GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA), or anti-NF-κB p65 rabbit monoclonal antibody (4764; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, CA, USA) at 4 °C overnight. Alexa Fluor™ Plus 488 (AF488)-conjugated goat polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG (A32731; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used as a secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (H3570; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The slides were mounted with DAKO Fluorescence Mounting Medium (S3023; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and fluorescent images were acquired using a confocal microscope (LSM 900; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). We obtained a minimum of five images for each slide. Images were analyzed using ZEISS ZEN 3.3 Microscopy Software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany; https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/en/products/software/zeiss-zen.html). AF488 signal images were merged with the corresponding Hoechst 33,342 images to obtain the nuclear/cytoplasmic mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ratio, which served as a measure for the level of transcription factor nuclear translocation. We acquired the nuclear/cytoplasmic MFI ratio of at least 10 cells per image.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the medians with IQRs, and comparisons were made using the Mann–Whitney U test. Fisher’s exact test was employed for comparisons of categorical variables. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated to quantify relationships between serum cytokine levels, immune cell subset frequencies, and clinical phenotype in anti-MDA5-positive DM. The performance of serum biomarkers on mortality prediction was assessed by ROC analysis. Cluster analyses of serum IFN and inflammatory cytokine levels were performed by hierarchical clustering using the squared Euclidean distance and the Ward agglomerative method. Serum cytokine levels were standardized using Z-scores before they were subjected to the analyses. Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan–Meier curves and the difference between clusters was tested by the log-rank test. HR was estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value < 0.05. We adjusted P-values by the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure where multiple testing was applied. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.r-project.org/).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ms. Miyuki Takatori and Ms. Kiyomi Kikukawa (Laboratory for Clinical Research, Collaborative Research Center, Nippon Medical School) for their technical support in immunocytochemistry analysis. This work was supported in part by a research grant on intractable diseases from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [22K08553].

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.Y., T.G., R.M., M.K.; Dara curation: A.Y., Y.O., M.S., Y.I., Y.K., T.F.; Formal analysis: A.Y.; Funding acquisition: T.G., M.K.; Investigation: A.Y., Y.O., M.S., Y.I., Y.K., T.F.; Methodology: A.Y., T.G., Y.O., M.S., R.M., M.K.; Project administration: M.K.; Resources: Y.O., M.S., R.M.; Software: A.Y.; Supervision, T.G., T.F., T.S., S.Y., R.M., M.K.; Validation: T.G., R.M., M.K.; Visualization, A.Y.; Writing-original draft, A.Y.; Writing-review and editing; all the authors.

Data availability

The data from this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

T.G. has received speaking fees from Asahi Kasei Pharma, Astellas, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, Eli Lily, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Tanabe-Mitsubishi; M.K. has received royalties from MBL; speaking honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim; consulting honoraria from Argenx, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GSK, and Novartis; and research grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim and MBL. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-10895-1.

References

- 1.Lundberg, I. E. et al. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers.7, 86. 10.1038/s41572-021-00321-x (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHugh, N. J. & Tansley, S. L. Autoantibodies in myositis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol.14, 290–302. 10.1038/nrrheum.2018.56 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allameen, N. A., Ramos-Lisbona, A. I., Wedderburn, L. R., Lundberg, I. E. & Isenberg, D. A. An update on autoantibodies in the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol.21, 46–62. 10.1038/s41584-024-01188-4 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey, G. R., MacFadyen, C. & Tansley, S. L. Newer autoantibodies and laboratory assessments in myositis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep.27, 5. 10.1007/s11926-024-01171-8 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nombel, A., Fabien, N. & Coutant, F. Dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibodies: Bioclinical features, pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Front. Immunol.12, 773352. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.773352 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu, X., Peng, Q. & Wang, G. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis: pathogenesis and clinical progress. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol.20, 48–62. 10.1038/s41584-023-01054-9 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato, S. et al. Initial predictors of poor survival in myositis-associated interstitial lung disease: A multicentre cohort of 497 patients. Rheumatology57, 1212–1221. 10.1093/rheumatology/key060 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gono, T. & Kuwana, M. Interstitial lung disease and myositis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol.36, 466–472. 10.1097/bor.0000000000001037 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gono, T. et al. Cytokine profiles in polymyositis and dermatomyositis complicated by rapidly progressive or chronic interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology53, 2196–2203. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu258 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye, Y. et al. Single-cell profiling reveals distinct adaptive immune hallmarks in MDA5+ dermatomyositis with therapeutic implications. Nat. Commun.13, 6458. 10.1038/s41467-022-34145-4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He, J. et al. Single-cell landscape of peripheral immune response in patients with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 dermatomyositis. Rheumatology63, 2284–2294. 10.1093/rheumatology/kead597 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gono, T., Okazaki, Y. & Kuwana, M. Antiviral proinflammatory phenotype of monocytes in anti-MDA5 antibody-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology61, 806–814. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab371 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thuner, J. & Coutant, F. IFN-γ: An overlooked cytokine in dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibodies. Autoimmun. Rev.22, 103420. 10.1016/j.autrev.2023.103420 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannini, M. et al. Similarities between COVID-19 and anti-MDA5 syndrome: What can we learn for better care?. Eur. Respir. J.56, 2001618. 10.1183/13993003.01618-2020 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki, T. et al. Interferon lambda 3 in the early phase of coronavirus disease-19 can predict oxygen requirement. Eur. J. Clin. Invest.52, e13808. 10.1111/eci.13808 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiyama, M. et al. Serum CCL17 level becomes a predictive marker to distinguish between mild/moderate and severe/critical disease in patients with COVID-19. Gene766, 145145. 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145145 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukada, A. et al. Prognostic role of interferon-λ3 in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheumatol.76, 796–805. 10.1002/art.42785 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundberg, I. E. et al. 2017 European league against rheumatism/american college of rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Ann. Rheum. Dis.76, 1955–1964. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211468 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolko, L. et al. Ultrasensitive interferons quantification reveals different cytokine profile secretion in inflammatory myopathies and can serve as biomarkers of activity in dermatomyositis. Front. Immunol.16, 1529582. 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1529582 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melki, I. et al. Anti-MDA5 juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: A specific subgroup defined by differentially enhanced interferon-α signaling. Rheumatology59, 1927–1937. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez525 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allenbach, Y. et al. Different phenotypes in dermatomyositis associated with anti-MDA5 antibody: Study of 121 cases. Neurology95, e70–e78. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000009727 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wack, A., Terczyńska-Dyla, E. & Hartmann, R. Guarding the frontiers: The biology of type III interferons. Nat. Immunol.16, 802–809. 10.1038/ni.3212 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manivasagam, S. & Klein, R. S. Type III interferons: Emerging roles in autoimmunity. Front. Immunol.12, 764062. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.764062 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goel, R. R., Kotenko, S. V. & Kaplan, M. J. Interferon lambda in inflammation and autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol.17, 349–362. 10.1038/s41584-021-00606-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gono, T. et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody, ferritin and IL-18 are useful for the evaluation of response to treatment in interstitial lung disease with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Rheumatology51, 1563–1570. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes102 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugiyama, M. et al. Development of specific and quantitative real-time detection PCR and immunoassays for λ3-interferon. Hepatol. Res.42, 1089–1099. 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01032.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian, J. et al. Type I interferon score is associated with the severity and poor prognosis in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis patients. Front. Immunol.14, 1151695. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1151695 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazear, H. M., Schoggins, J. W. & Diamond, M. S. Shared and distinct functions of type I and type III interferons. Immunity50, 907–923. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.025 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye, L., Schnepf, D. & Staeheli, P. Interferon-λ orchestrates innate and adaptive mucosal immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol.19, 614–625. 10.1038/s41577-019-0182-z (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin, S. et al. Decrease in cell counts and alteration of phenotype characterize peripheral NK cells of patients with anti-MDA5-positive dermatomyositis. Clin. Chim. Acta.543, 117321. 10.1016/j.cca.2023.117321 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye, Y. et al. Two distinct immune cell signatures predict the clinical outcomes in patients with amyopathic dermatomyositis with interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheumatol.74, 1822–1832. 10.1002/art.42264 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leem, G. et al. Abnormality in the NK-cell population is prolonged in severe COVID-19 patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.148, 996–1006. 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.07.022 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honda, K., Takaoka, A. & Taniguchi, T. Type I interferon [corrected] gene induction by the interferon regulatory factor family of transcription factors. Immunity25, 349–360. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.009 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osterlund, P. I., Pietilä, T. E., Veckman, V., Kotenko, S. V. & Julkunen, I. IFN regulatory factor family members differentially regulate the expression of type III IFN (IFN-lambda) genes. J. Immunol.179, 3434–3442. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3434 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faria, M. et al. Different phenotypic manifestations between Brazilian and Japanese anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis: an international tricentric longitudinal study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol.43, 193–201. 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/9s7djz (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connors, G. R., Christopher-Stine, L., Oddis, C. V. & Danoff, S. K. Interstitial lung disease associated with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: what progress has been made in the past 35 years?. Chest138, 1464–1474. 10.1378/chest.10-0180 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer, A. et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement: Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur. Respir. J.46, 976–987. 10.1183/13993003.00150-2015 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hochberg, M. C. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum.40, 1725. 10.1002/art.1780400928 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aringer, M. et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis.78, 1151–1159. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214819 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gladman, D. D., Ibañez, D. & Urowitz, M. B. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J. Rheumatol.29, 288–291 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gandhi, R. T., Lynch, J. B. & Del Rio, C. Mild or moderate covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med.383, 1757–1766. 10.1056/NEJMcp2009249 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gono, T., Okazaki, Y., Murakami, A. & Kuwana, M. Improved quantification of a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit for measuring anti-MDA5 antibody. Mod. Rheumatol.29, 140–145. 10.1080/14397595.2018.1452179 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuwana, M. & Okazaki, Y. A multianalyte assay for the detection of dermatomyositis-related autoantibodies based on immunoprecipitation combined with immunoblotting. Mod. Rheumatol.33, 543–548. 10.1093/mr/roac056 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maecker, H. T., McCoy, J. P. & Nussenblatt, R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the human immunology project. Nat. Rev. Immunol.12, 191–200. 10.1038/nri3158 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data from this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.