Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe the appearance and occurrence of abnormalities in the levator ani muscle seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in nulliparous women and in women after their first vaginal birth.

METHODS

Multiplanar proton density magnetic resonance images were obtained at 0.5-cm intervals from 80 nulliparous and 160 vaginally primiparous women. These had been previously obtained in a study of stress incontinence, and half the primiparas had stress incontinence. All scans were reviewed independently by at least two examiners blinded to parity and continence status.

RESULTS

No levator ani defects were identified in nulliparous women. Thirty-two primiparous women (20%) had a visible defect in the levator ani muscle. Defects were identified in the pubovisceral portion of the levator ani in 29 women and in the iliococcygeal portion in three women. Within the pubovisceral muscle, both unilateral and bilateral defects were found. The extent of abnormality varied from one individual to the next. Of the 32 women with defects, 23 (71%) were in the stress incontinent group.

CONCLUSION

Abnormalities in the levator ani muscle are present on MRI after a vaginal delivery but are not found in nulliparas.

During a study of the role of vaginal birth in causing urinary incontinence we obtained magnetic resonance images of women with stress incontinence after their first vaginal birth and of normal continent nulliparous and primiparous controls. On evaluating these scans we found abnormalities in the levator ani muscles in both the continent and incontinent women. The abnormalities seemed to occur only in women who delivered vaginally, and not in nulliparas. These abnormalities involved both the pubovisceral and iliococcygeal portions of the muscle and were sometimes unilateral and sometimes bilateral. Here we describe these defects and evaluate whether or not they are associated with vaginal delivery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Magnetic resonance images of the pelvis were obtained from 240 women as part of an institutional review board–approved study concerning vaginal delivery and stress urinary incontinence. Multiplanar two-dimensional fast spin (echo time 15 ms, repetition time 4000 ms) proton density magnetic resonance images of all pelves were obtained by use of a 1.5-tesla superconducting magnet (Signa; General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) with version 5.4 software as previously described.1 Images 5 mm apart were obtained in axial, coronal, and sagittal views.

At least two examiners blinded to the subject’s parity and continence reviewed all magnetic resonance scans independently of one another. On initial review, scans that appeared to have abnormalities were presumptively identified based on comparison with normal anatomy of the levator ani muscle previously described by our group.1–3 Final classification of a muscle as abnormal was made only when abnormal morphology was found in both the axial and the coronal planes and agreed upon by two examiners. In two instances two examiners disagreed as to the presence of an abnormality in the levator ani. Re-examination of the scans disclosed that the one abnormal classification in each pair arose because of an asymmetry in the muscle’s appearance. Further examination revealed that the difference between the two sides was related to the woman’s asymmetric placement in the scanner, rather than a muscle abnormality on one side. Both of these subjects were classified as normal. For review and description we divided the muscle into its two major components, the pubovisceral and the iliococcygeal.4 The pubovisceral portion includes those muscles arising from the pubic bones—namely, the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and puboperineus.

After this process, a new examiner (RK) viewed all scans while blinded to parity, continence, and previous evaluations and independently confirmed all defects. The abnormal scans were then once more reviewed independently by two individuals to finalize classification as abnormal.

These scans came from a study of 240 women that included 80 nulliparas and 160 primiparas. Of the primiparous women 80 were continent and 80 had stress incontinence that persisted at least 9 months after delivery. All groups were recruited to be similar in age (Table 1). There were no group differences in racial composition among the whites (89.4%), blacks (3.8%), and women of other racial groups (6.8%). None of the continent women exhibited stress incontinence during urodynamic examination.

Table 1.

Study Population Demographics

| Nullipara | Primiparous continent | Primiparous incontinent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 29.2 (5.5) | 29.8 (4.4) | 30.0 (5.7) |

| Height (m) | 1.66 (0.06) | 1.66 (0.07) | 1.66 (0.07) |

| Weight (kg) | 66.4 (13.1) | 63.4 (12.9) | 71.2 (16.6) |

| BMI | 24.3 (4.4) | 23.4 (4.2) | 26.2 (5.6) |

Mean (standard deviation).

All 240 women were subjected to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvic floor. The parous women were examined 9–12 months after delivery. As part of the overall study all women had a pelvic examination to detect prolapse5 and urodynamic evaluation including cystometrography, urethral function assessment, ultrasound examination of urethral support,6 and full bladder stress testing.

RESULTS

There were 32 women (20%) with a visible defect in one or both levator ani muscles among the 160 parous women in the study. Of these, 29 (18%) involved the pubovisceral portion of the muscle and three (2%) involved the iliococcygeal portion. Of the 80 women who were incontinent, 23 (28%) had a defect in the levator ani muscle, and of the 80 primiparous continent women, nine (11%) had a defect, making stress incontinent primiparas twice as likely to have a muscle abnormality. No defects were identified in nulliparous women.

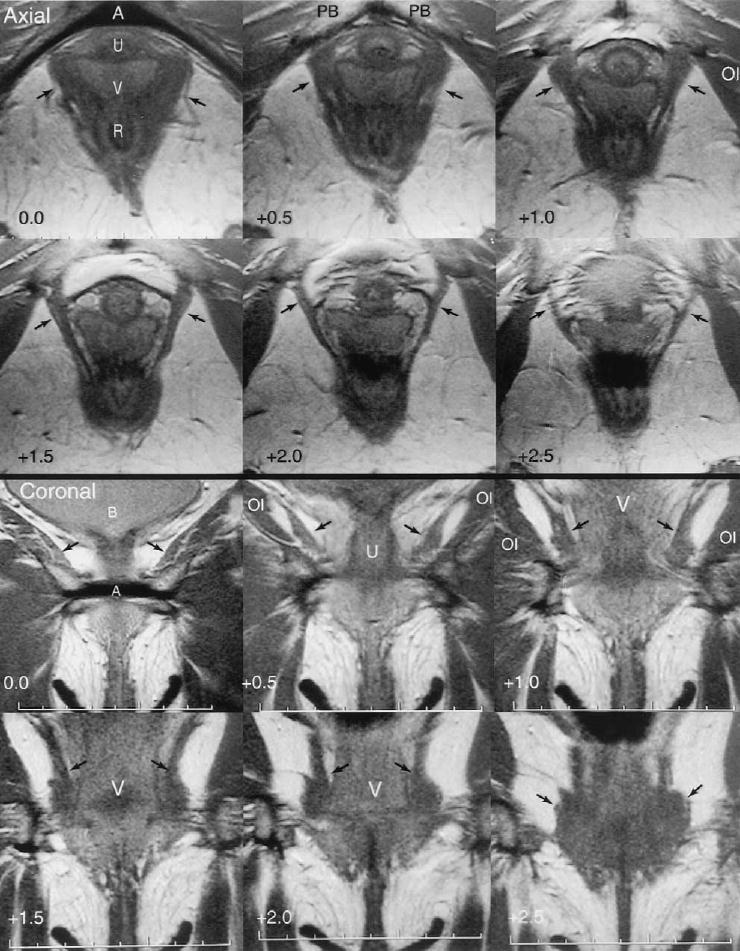

An example of normal magnetic resonance anatomy seen in a 45-year-old nulliparous continent volunteer is shown in Figure 1. In the axial scans the levator ani muscle can be seen arising from the pubic bone lateral to the urethra, vagina, and rectum. The coronal view demonstrates the same anatomy in a perpendicular plane. Note in the axial scans the location of the pubovisceral portion of the levator ani muscle between the urethra and vagina and the obturator internus muscle where it attaches to the pubic bone.

Figure 1.

Axial and coronal images from a 45-year-old nulliparous woman. The urethra (U), vagina (V), rectum (R), arcuate pubic ligament (A), pubic bones (PB), and bladder (B) are shown. The arcuate pubic ligament is designated as zero for reference, and the distance from this reference plane is indicated in the lower left corner. Note the attachment of the levator muscle (arrows) to the pubic bone in axial +1.0, +1.5, and +2.0. Coronal images show the urethra, vagina, and muscles of levator ani and obturator internus (OI). (Reprinted with permission. © DeLancey 2002.)

DeLancey. Levator Defects After Birth. Obstet Gynecol 2003.

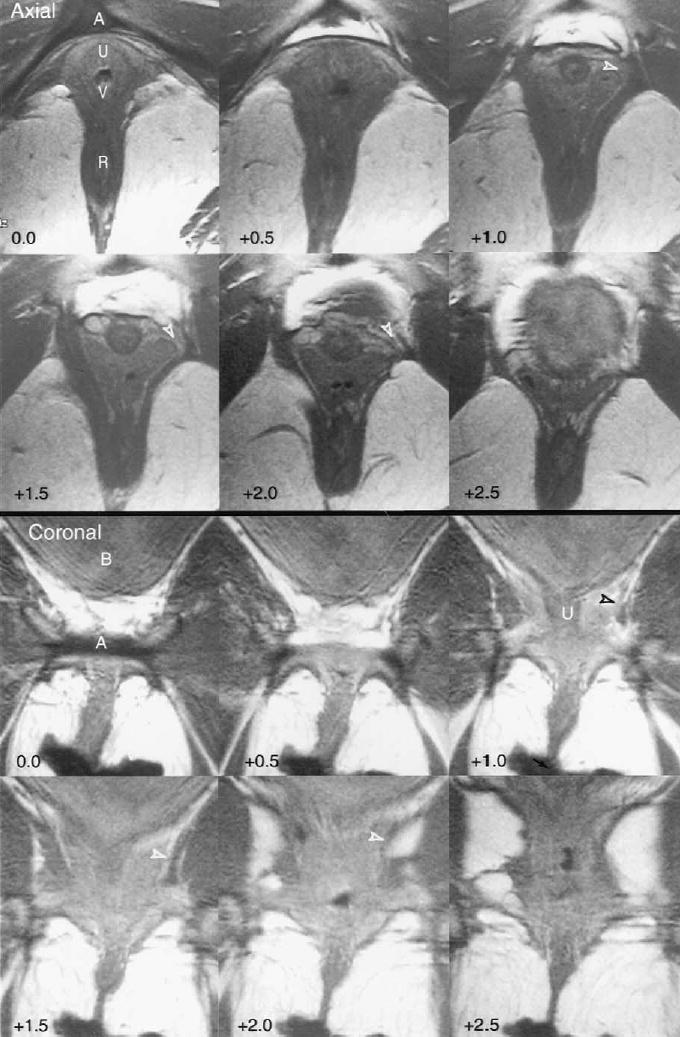

Figure 2 shows the appearance of a unilateral defect in the left levator ani muscle of a 34-year-old primiparous woman. The asymmetry between the two sides can be seen where the part of the muscle that normally attaches to the pubic bone is lost. A small portion of the muscle remains between the urethra, vagina, and obturator internus muscle. The iliococcygeal portion of the levator ani muscle remains normal. The vagina protrudes laterally into the defect, so that the vagina lies closer than normal to the obturator internus muscle.

Figure 2.

Axial and coronal images from a 34-year-old incontinent primiparous woman showing a unilateral defect in the left pubovisceral portion of the levator ani muscle. The arcuate pubic ligament (A), urethra (U), vagina (V), rectum (R), and bladder (B) are shown. The location normally occupied by the pubovisceral muscle is indicated by the open arrowhead in axial and coronal images +1.0, +1.5, and +2.0. (Reprinted with permission. © DeLancey 2002.)

DeLancey. Levator Defects After Birth. Obstet Gynecol 2003.

Figure 3 shows the appearance of complete loss of the pubovisceral muscle bilaterally. Note the absence of attachment to the pubic bones as well as the protrusion of the vagina all the way to the obturator internus muscle.

Figure 3.

Axial and coronal images of a 38-year-old incontinent primiparous woman are shown. The area where the pubovisceral portion of the levator ani muscle is missing (open arrowhead) between the urethra (U), vagina (V), rectum (R), and obturator internus muscle (OI) is shown. The vagina protrudes laterally into the defects to lie close to the obturator internus muscle. A = arcuate pubic ligament. (Reprinted with permission. © DeLancey 2002.)

DeLancey. Levator Defects After Birth. Obstet Gynecol 2003.

In some women, the bulk of the levator ani muscle was lost but the overall structural relationships were retained, as shown in Figure 4. Note the normal location of the vagina in contrast to the appearance in Figures 2 and 3, where the vagina is no longer held in place by the fascial envelope of the levator ani muscle.

Figure 4.

Levator ani defect in a 30-year-old incontinent primiparous woman with loss of muscle bulk but preservation of pelvic architecture. The area where the levator is absent in this woman is shown (open arrowhead) in the axial images and the coronal images +1.5 and +2.0. Note that in contrast to Figure 3, where the vagina lies close to the obturator internus (OI), it has a normal shape. The normal appearance of the levator ani muscle is seen in coronal images +2.0 and +2.5 (arrows). A = arcuate pubic ligament; U = urethra; V = vagina; R = rectum. (Reprinted with permission. © DeLancey 2002.)

DeLancey. Levator Defects After Birth. Obstet Gynecol 2003.

In three women a portion of the iliococcygeus muscle was smaller in both axial and coronal images. This defect is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Iliococcygeus muscle defect. Thinning of the iliococcygeus muscle is demonstrated (open arrowheads) on the patient’s left in axial images +3.0, +3.5, and +4.0 and coronal images +1.0 and +1.5. The urethra (U), vagina (V), bladder (B), rectum (R), and arcuate pubic ligament (A) are shown. (Reprinted with permission. © De-Lancey 2002.)

DeLancey. Levator Defects After Birth. Obstet Gynecol 2003.

DISCUSSION

Abnormalities have previously been demonstrated in the levator ani muscles of women with stress urinary incontinence7 and pelvic organ prolapse,8 using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These abnormalities could be a variant of normal anatomy, they could be a distortion caused by abnormal pelvic organ positions, or they could be damage that occurred during vaginal delivery. Our study depicts levator ani muscle damage after vaginal birth and provides the first scientific evidence that supports vaginal birth as a source of levator ani muscle injuries. By comparing nulliparous women and women after one vaginal delivery, we have documented the presence of birth injury to the levator ani among vaginally parous individuals but not nulliparas.

Vaginal birth is the single most important risk factor for the development of pelvic floor dysfunction.9–11 Although vaginal delivery has been well established as a significant risk for the subsequent development of pelvic floor dysfunction, the type of pelvic floor injury that occurs during vaginal birth that results in pelvic floor dysfunction has not been previously established.

Our findings also show the extent of levator ani abnormalities seen in these birth-related injuries and provide a rough idea of how frequently they occur. Further delineation of women’s risk for levator injury will require a population-based study of women recruited before delivery. To gain a better understanding of soft tissue injury during delivery, additional research will be needed to identify induced connective tissue rupture in the vaginal supports that also play a role in pelvic floor dysfunction.12 Once this is done, the interrelationship and interaction between these muscular and fascial injuries can be more fully appreciated.

We have found that levator ani muscle injury most frequently involves the pubovisceral portion of the levator ani muscle that arises from the inner surface of the pubic bone just lateral to the vagina but also involves the iliococcygeal muscle. In some of these women the vagina protrudes laterally beyond the confines of its normal location to reach the obturator internus muscle, whereas in others it stays in its normal position (Figures 3 and 4). The difference between these two types of injury needs further clarification. These differences may arise because some muscles are avulsed from their origin, whereas in others they may be denervated, but the overall connections of the muscle to the bone might remain intact. These speculations need further investigation. Documentation of the symptoms and physical findings associated with each of these injuries will also permit further analysis.

The importance of the levator ani muscles providing pelvic organ support has long been recognized.13 They close the pelvic floor and support the pelvic organs14 in a valve-like apparatus. Damage to these pelvic muscles results in sagging and tipping of the “levator plate.”15 This decreased muscular support presumably increases loads on the fascia and connective tissues of the pelvis. Because the load carried by the pelvic floor is shared between the muscles and connective tissues, a decrease in muscle function would shift additional load to the fibrous elements.

Previous studies have demonstrated that women with pelvic organ prolapse have gross abnormalities in the levator ani muscle.13 Histologic abnormalities in the levator ani muscles of cadavers of women with vaginal parity show significant muscle replacement by fibrosis.16 Studies have also demonstrated fibrosis in the muscles of women with stress urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse and further indicated that those with the least muscle are more likely to have recurrence after surgery.17,18

The ability of MRI to allow study of the entire muscle in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional displays in living women has obvious advantages for scientific study.2,19,20 It also allows the ethical study of normal volunteers with proven continence and pelvic organ support. With the significant asymmetries of muscle damage seen, MRI avoids the problems stemming from taking a single biopsy from one side of an individual, which might indicate a healthy muscle there but would fail to pick up that the muscle on the other side is abnormal.

It has been well established that pelvic nerve injury is associated with pelvic floor dysfunction.21–24 Nerve injury after vaginal delivery has also been shown.25 Further research should help define the relationship between nerve injury and magnetic resonance–visible abnormalities. We believe MRI and electromyography will prove to be complementary techniques. Because electromyography testing requires an innervated muscle, it is not able to detect the complete absence of muscle documented in our magnetic resonance images because the myographer must seek innervated muscle to study. On the other hand, electromyography studies will probably play a crucial role in determining the cause of muscle abnormalities.

Now that we have defined the visibility of levator ani muscle damage, it will be possible to study the obstetric factors that lead to this injury. Once the factors associated with increased risk for this injury can be defined, it will be possible to assess risk factors for developing damage. Also needed is a more complete understanding of the relationship between levator injury and pelvic organ prolapse. Now that it can be documented, we can observe these women to see what symptoms develop, when they arise, and what other factors, such as connective tissue injury, influence the development of dysfunction and prolapse. A complete picture will depend on adding other observations. The clear visibility of these injuries and the fact that they can be permanently recorded with magnetic resonance scans add an important investigative tool.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK51405 and R01 HD38665.

References

- 1.Chou Q, DeLancey JOL. A structured system to evaluate urethral support anatomy in magnetic resonance images. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:44–50. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tunn R, DeLancey JOL, Howard D, Thorp JM, Ashton-Miller JA, Quint LE. MR imaging of levator ani muscle recovery following vaginal delivery. Int Urogynecol J. 1999;10:300–7. doi: 10.1007/s001929970006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strohbehn K, Ellis JH, Strohbehn JA, DeLancey JO. Magnetic resonance imaging of the levator ani with anatomic correlation. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:277–85. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00410-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawson JO. Pelvic anatomy I. Pelvic floor muscles. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1974;54:244–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JOL, Klarskov P, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy AP, DeLancey JOL, Zwica LM, Ashton-Miller JA. On-screen vector based ultrasound assessment of vesical neck movement. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:65–70. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirschner-Hermanns R, Wein B, Niehaus S, Schaefer W, Jakse G. The contribution of magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic floor to the understanding of urinary incontinence. Br J Urol. 1993;72:715–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tunn R, Paris S, Fischer W, Hamm B, Kuchinke J. Static magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic floor muscle morphology in women with stress urinary incontinence and pelvic prolapse. Neurourol Urodyn. 1998;17:579–89. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(1998)17:6<579::aid-nau2>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mant J, Painter R, Vessey M. Epidemiology of genital prolapse: Observations from the Oxford Family Planning Association study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:579–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skoner MM, Thompson WD, Caron VA. Factors associated with risk of stress urinary incontinence in women. Nurs Res. 1994;43:301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viktrup L, Lose G, Rolff M, Barfoed K. The symptom of stress incontinence caused by pregnancy or delivery in primiparas. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:945–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson AC, Edmonds PB, Williams NL. Treatment of stress urinary incontinence due to paravaginal fascial defect. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;57:357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halban J, Tandler J. Anatomie und Aetiologie der Genital-prolapse beim Weibe. Vienna, Austria: Wilhelm Braumuller, 1907.

- 14.Porges RF, Porges JC, Blinick G. Mechanisms of uterine support and the pathogenesis of uterine prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 1960;15:711–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berglas B, Rubin IC. Study of the supportive structures of the uterus by levator myography. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1953;97:677–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimpfl T, Jaegar C, Mueller-Felber W, Anthuber C, Hirsch A, Brandmaier R, et al. Myogenic changes of the levator ani muscle in premenopausal women: The impact of vaginal delivery and age. Neurourol Urodyn. 1998;17:197–206. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(1998)17:3<197::aid-nau4>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koelbl H, Strassegger H, Riss PA, Gruber H. Morphologic and functional aspects of pelvic floor muscles in patients with pelvic relaxation and genuine stress incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:789–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanzal E, Berger E, Koelbl H. Levator ani muscle morphology and recurrent genuine stress incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:426–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fielding J, Dumanli H, Schreyer A, Okuda S, Gering D, Zou K, et al. MR-based three dimensional modeling of the normal pelvic floor in women: Quantification of muscle mass. Am J Radiol. 2000;174:657–60. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoyte L, Schierlitz L, Zou K, Flesh G, Fielding JR. Two-and 3-dimensional MRI comparison of levator ani structure, volume, and integrity in women with stress incontinence and prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:11–9. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith ARB, Hosker GL, Warrell DW. The role of partial denervation of the pelvic floor in the aetiology of genito-urinary prolapse and stress incontinence of urine: A neurophysiological study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:24–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith ARB, Hosker GL, Warrell DW. The role of pudendal nerve damage in the aetiology of genuine stress incontinence in women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:29–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snooks SJ, Badenoch DF, Tiptaft RC, Swash M. Perineal nerve damage in genuine stress urinary incontinence: An electrophysiological study. Br J Urol. 1985;57:422–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1985.tb06302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snooks SJ, Swash M, Mathers SE, Henry MM. Effect of vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor: A 5-year follow-up. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1358–60. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen RE, Hosker GL, Smith ARB, Warrell DW. Pelvic floor damage and childbirth: A neurophysiological study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:770–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]