Abstract

Background

Chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy holds promise for cancer treatment, but its efficacy is often hindered by metabolic constraints in the tumor microenvironment. This study investigates the role of glutamine in enhancing CAR-T cell function against ovarian cancer.

Methods

Metabolomic profiling of blood samples from ovarian cancer patients treated with MSLN-CAR-T cells was conducted to identify metabolic changes. In vitro, glutamine pretreatment was applied to CAR-T cells, and their proliferation, CAR expression, tumor lysis, and cytokine production (TNF-α, IFN-γ) were assessed. Mechanistic studies focused on the mTOR-SREBP2 pathway and its effect on HMGCS1 expression, membrane stability and immune synapse formation. In vivo, the antitumor effects and memory phenotype of glutamine-pretreated CAR-T cells were evaluated.

Results

Elevated glutamine levels were observed in the blood of ovarian cancer patients who responded to MSLN-CAR-T cell treatment. Glutamine pretreatment enhanced CAR-T cell proliferation, CAR expression, tumor lysis, and cytokine production. Mechanistically, glutamine activated the mTOR-SREBP2 pathway, upregulating HMGCS1 and promoting membrane stability and immune synapse formation. In vivo, glutamine-pretreated CAR-T cells exhibited superior tumor infiltration, sustained antitumor activity, and preserved memory subsets.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight glutamine-driven metabolic rewiring via the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis as a strategy to augment CAR-T cell efficacy in ovarian cancer.

Trial registration

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-025-06853-0.

Keywords: CAR-T cell therapy, T cell exhaustion, Glutamine, MTOR-SREBP2 Axis, HMGCS1, Ovarian cancer

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy has demonstrated remarkable success in hematological malignancies [1,2]; however, its efficacy against solid tumors [3], particularly ovarian cancer [4], remains limited. Ovarian cancer—the most lethal gynecologic malignancysis, frequent peritoneal dissemination, intrinsic chemoresistance and a distinct metabolic profile featuring enhanced glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation, and glutamine dependency [5], posing significant therapeutic challenges [6]. Ovarian tumors have been shown to exhibit increased fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and altered amino acid metabolism, including elevated glutamine consumption, which further enhances the aggressive nature of the disease [7,8]. These metabolic characteristics not only define the tumor biology of ovarian cancer but also present potential targets for metabolic interventions aimed at improving therapeutic outcomes. A key molecular feature of this disease is the overexpression of mesothelin (MSLN) [9,10], a cell surface glycoprotein involved in tumor progression and metastasis, which is present in > 80% of epithelial ovarian cancers but exhibits restricted expression in normal mesothelial tissues [11]. This tumor-selective expression pattern renders MSLN an attractive target for CAR-T cell therapy [12]. Although preclinical and early clinical studies have shown promising antitumor activity of MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells, their clinical application is hindered by multiple barriers, including the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME)13, on-target/off-tumor toxicity risks [14], and tumor antigen heterogeneity leading to immune escape [15]. Glutamine has been shown to support T cell function and metabolism, and it may play a role in enhancing CAR-T cell persistence, infiltration, and effector function in the ovarian tumor microenvironment (TME)16–18. However, the specific effects and underlying mechanisms within the complex ovarian TME require further investigation and validation.

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of T cell activation, including CAR-T cells [19]. Upon activation, T cells shift their metabolism from a quiescent to an effector state, characterized by increased glucose uptake, enhanced mitochondrial activity, and elevated amino acid metabolism [20]. These changes are crucial for supporting cell proliferation, effector functions, and memory formation. Among key metabolic regulators, glutamine has emerged as an essential amino acid in T cell metabolism [21,22], providing critical substrates for energy production, protein synthesis, and nucleotide biosynthesis. Specifically, glutamine supports T cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine secretion, which are essential for CAR-T cell function [23].

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of metabolic modulation in CAR-T therapy [24]. While the roles of glucose and fatty acid metabolism in CAR-T cells have been investigated, the role of glutamine remains underexplored [25]. Notably, metabolomic studies in ovarian cancer patients treated with MSLN-CAR-T cells showed significantly higher glutamine levels in treatment-responsive patients, suggesting its potential role in enhancing CAR-T cell function in ovarian cancer. For example, strategies such as targeting cholesterol metabolism, enhancing mitochondrial function, or modulating glutamine pathways have demonstrated the potential to boost CAR-T efficacy [17,22,26]. Our study builds upon and extends these findings by specifically elucidating the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis as a key mechanistic link between glutamine metabolism and CAR-T cell functionality in ovarian cancer.

This study aims to explore the effect of glutamine pretreatment on CAR-T cell functionality and its potential to improve therapeutic outcomes in ovarian cancer. The enhancement of CAR-T cell function with glutamine appears to be mediated through key metabolic pathways. Glutamine has been shown to activate the mTOR-SREBP2 axis, a crucial pathway in cell metabolism and immune function [27,28]. Upon activation, mTOR stimulates the SREBP2 transcription factor, a master regulator of lipid metabolism whose activation drives both physiological homeostasis and pathological processes in cancer [29]. SREBP2 regulates cholesterol biosynthesis and lipid metabolism. Specifically, SREBP2 upregulates HMGCS1, a key enzyme in cholesterol synthesis [30], which modulates T cell immune responses by fueling the mevalonate pathway and thereby shaping T cell activation, proliferation, and effector functions [31–33]. Cholesterol is critical for cell membrane stability and plays a role in immune synapse formation between CAR-T cells and tumor cells [26,34]. Enhanced membrane stability likely contributes to increased CAR-T cell tumor lysis and cytokine production, thereby improving therapeutic efficacy.

We demonstrate that 5 mM glutamine pretreatment (vs. 0 or 10 mM) optimally improved CAR-T cell proliferation, memory phenotype, and overall function. This highlights the importance of optimizing glutamine concentration for effective metabolic reprogramming.

Furthermore, glutamine pretreatment led to increased ATP production, mitochondrial activity, and oxidative phosphorylation in CAR-T cells, suggesting enhanced metabolic activity and energy production, essential for sustained antitumor activity. The enhanced metabolic profile of glutamine-treated CAR-T cells indicates their better ability to persist and function in the tumor microenvironment.

In vivo, glutamine-pretreated CAR-T cells exhibited stronger tumor infiltration, improved tumor regression, and prolonged survival compared to control CAR-T cells. Flow cytometry and PCR data showed increased CAR-T cell numbers, elevated memory phenotype, and enhanced cytokine production in the peripheral blood of mice treated with glutamine-enhanced CAR-T cells. Histopathological analysis revealed no significant toxicity to normal tissues, indicating that glutamine treatment does not induce harmful side effects.

In conclusion, this study underscores the critical role of glutamine in optimizing CAR-T cell function and improving therapeutic efficacy, especially in ovarian cancer. Glutamine pretreatment enhances CAR-T cell metabolic activity, memory formation, and immune synapse stability, contributing to improved antitumor responses. By leveraging glutamine’s metabolic benefits, we can enhance the effectiveness and longevity of CAR-T therapies, offering new possibilities for improving cancer treatment outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patient characteristics and study design

Informed by preclinical data, an investigator-initiated clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT05372692) was designed to assess the safety and therapeutic potential of MSLN CAR-T cells in patients with ovarian cancer. Four individuals with chemotherapy-resistant metastatic ovarian cancer, who had not previously undergone CAR-T therapy, received lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, followed by a single infusion of MSLN CAR-T cells. After treatment with MSLN CAR-T cells, blood samples were collected for non-targeted metabolomics analysis to investigate metabolic changes in response to therapy.

Cell lines

The ovarian cancer cell lines OVCAR3 (ATCC HTB-161), CAOV3 (HTB-75), SKOV3 (ATCC HTB-77), and 293 T (Human Embryonic Kidney 293 Cells, expressing the SV40 large T antigen, ATCC CRL-3216) were originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and individually grown in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO, USA), McCoy's 5 A (GIBCO, USA) and Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM;GIBCO, USA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; GIBCO, USA). Stable cell lines expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) and firefly luciferase (ffLuc) were generated through lentiviral transduction. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

CAR T cell preparation

The single chain antibody fragment (scFv) was fused to the CD8a hinge and transmembrane domains followed by human intracellular CD28 and CD3z signaling endodomain. Briefly, Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors (MiaoShun Biotech, China) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (Stemcell Technologies, Canada), followed by negative selection of T cells with the EasySep™ Human T Cell Isolation Kit (Stemcell Technologies, Canada). The purified T cells were activated with anti-human CD3/CD28 magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at a 3:1 bead-to-cell ratio and cultured in X-VIVO 15 serum-free hematopoietic cell medium (Lonza, Switzerland) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and 300 IU/mL recombinant human IL-2 (PeproTech, USA).

Cell viability assay by CCK-8

To assess the cytotoxicity of varying glutamine concentrations, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well and cultured in glutamine-free medium supplemented with different concentrations of cystine (0–20 mM) and glutamine (0–30 mM). After 48 h of incubation, cell viability was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Vazyme, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The selected working concentrations for subsequent CAR-T cell functional assays (1 mM for cystine and 5 mM for glutamine) were chosen based on dose–response curves (Figure S1D–E), ensuring minimal cytotoxicity to target cells. These concentrations allowed us to isolate the effects of metabolite pretreatment on CAR-T cell function without confounding toxicity.

Flow cytometry

In vitro cultured cells, or cells took from mice were washed in FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS and 2 mM EDTA), and resuspended in FACS buffer with antibodies at 4 °C for 20 min. All flow cytometry was analyzed using FlowJo v10 software with standard filter sets including removal of doublets and dead cells. T cell phenotype antibodies: anti-MSLN-PE, CD45RA-APC, CCR7-PE, CD25-PE, CD69-PerCP, PD1-APC and TIM3-PE were purchased from BD (San Diego, CA).

Cell proliferation assay

Different CAR-T cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 1 × 106 cells per well on day 4, and were fluorescently labeled by carboxy-fluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cells are cultured in an atmosphere of 1% oxygen, then detect the fluorescence values by flow cytometry on day 7.

Apoptosis assay

To measure the apoptotic rate, CAR-T cells were seeded into six-well plates. Annexin V-PE/7-AAD Apoptosis Detection Kit (Vazyme, China) was used based on the manufacturer’s instruction. In brief, cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS, and incubated with 100 μL 1 × Binding Bufer supplemented with 5 μL Annexin V-PE and 5 μL 7-AAD Staining Solution. 10 min later, another 400 μL 1 × Binding Bufer were added. Apoptotic rate was measured by flow cytometry.

ROS Generation and Extracellular ATP Detection

For ROS detection, cells were subsequently incubated with 10 μM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; Yeasen Biotechnology, China) at 37 °C for 15 min in the dark, followed flow cytometric analysis after PBS washing. Parallel samples were processed for extracellular ATP quantification using a commercial ATP Chemiluminescence Assay Kit (Elabscience, China), with luminescence measurements performed according to the manufacturer's protocol on a microplate reader. Results expressed as the percentage of DCF-positive cells relative to the total viable cell population, while ATP concentrations were calculated against a standard curve.

Cytotoxicity and cytokine assay

For in vitro cytotoxicity and cytokine test, CAR T cells were co-cultured with OVCAR3 cells in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS at indicated effector: target ratio. After 6 h, the cells were evaluated by a luciferase-based assay. Briefly, cells were collected by centrifugation at 400 × g for 10 min at room temperature, and the supernatant was transferred to new tubes for cytokine release assays using the BD Human Th1/Th2 Cytokine Cytometric bead array (CBA) kit (Becton–Dickinson). The pellet was rinsed with 100 μL Phenol Red Free Medium, then add 100ul One-Lite assay reagent. After incubation for 5 min at room temperature and protected from light, the supernatant was mixed and transferred to the plate. and transferred into a 96 well opaque tissue culture plate. The plates were read in a luminometer (SpectraMax iD3). Cytotoxicity was calculated according to the average loss of luminescence of the experimental condition relative to the control wells containing target cells.

For serial killing cytotoxicity, the CAR T cells were treated with different concentrations of glutamine (0, 2, 5, and 10 mM), then CAR T cells were serially stimulated with OVCAR3 at 2:1 ratio of effector to tumor cells at 24 h intervals Simultaneously, luminous intensity of tumor cells were assessed at 24 h intervals.

Impedance-based kinetics cell lysis assay

Real-time impedance analysis of cell lysis kinetics was evaluated over 50 h. OVCAR3, CAOV3, SKOV3 and 293 T cells were plated in a 96-well resistor bottom plate at 4.0 × 104 cells per well. After cultured for 24 h, effector T cells were added into the unit at different effector/target cell (E: T) ratios (1:1 and 1:4). Impedance was measured at 28 s intervals. The impedance-based cell index for each well and time point was normalized with the cell index before adding CAR-T cells. The kinetics of cell lysis was evaluated as the change in normalized cell index over time.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total mRNA from CAR T cells was isolated using Freezol (Vazyme, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was then synthesized via the Super Script First-Strand Synthesis System (Vazyme, China) using PCR Thermal Cycler (Thermo, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Vazyme, China). The comparative Ct values of genes were normalized to the Ct value of β-actin. Then, the 2^−ΔΔCt method was used to calculate the fold changes of gene expression over control.

Extracellular flux analysis

Cellular metabolic function was evaluated using the Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA) following standardized protocols. Cells were plated at an optimized density of 2 × 104 cells/well in XF96 microplates and cultured overnight under normal growth conditions. Prior to analysis, cells were washed and maintained in pre-warmed, substrate-supplemented XF assay medium (10 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine, pH 7.4) for 60 min at 37 °C in a non-CO₂ environment to allow metabolic equilibration. The mitochondrial stress test protocol involved sequential administration of metabolic modulators: oligomycin (1.5 μM) to assess ATP-linked respiration, FCCP (1.0 μM) to measure maximal respiratory capacity, and rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 μM each) to determine non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Parallel measurements of extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) provided glycolytic activity data. Three independent experimental replicates were performed for each condition.

NAD + /NADH assay

NAD + and NADH levels were determined using a WST-8-based enzymatic assay (Beyotime, China). Briefly, cells were lysed and split for separate quantification of total NAD +/NADH (untreated lysate) and NADH (heat-treated lysate, 60 °C for 30 min). NAD + levels were derived by subtraction. Absorbance (450 nm) was measured after WST-8 reduction and normalized to cell counts.

α-KG measurement

Intracellular α-KG was detected via an Amplex Red-coupled enzymatic reaction (Beyotime, China). Cell lysates were incubated with ALT/pyruvate oxidase/HRP reagent (37 °C, 30 min), and absorbance (570 nm) was quantified against an α-KG standard curve. Values were normalized to cellularity.

Western blot analysis

Proteins of cells were extracted with RIPA buffer and the concentration was measured using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Termo Scientifc, MA, USA). Protein samples were separated in 8–12% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred onto PVDF membranes. Afterward, membranes were blocked for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies overnight. After the incubation with the corresponding species-specifc secondary antibodies for 1 h, bands were detected by chemiluminescence using an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) system. Primary antibodies used in this study are as follows: anti-Tubulin (1:1000, Beyotime, China) and anti-HMGCS1 (1:1000, Proteintech Group, China).

qRT-PCR analysis of MSLN CAR-T DNA copy numbers

Real-time fluorescent qPCR was applied to determine the copy numbers of MSLN CAR-T DNA in DNA extracted from mouse plasma. Genomic DNA was extracted from mouse PBMCs using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, German) after CAR-T cell infusion. The forward primer 5′-ACCTGGTCGACAATCAACC-3′, reverse primer 5′-AAGCAGCGTATCCACATAGC-3′, and TaqMan probe 5′-FAM-CAAAATTTGTGAAAGATTGACTGGT-TAMRA-3′ were used in the qPCR assay.

Generation of CRISPR–Cas9 knockout CAR-T cells

T cells were transduced with lentivirus of pLenti-MSLN. MSLN + cells were sorted, and expression of MSLN was confirmed by flow cytometry. CAR-T cells were then transduced with control sgRNA (sgNTC: ATGACACTTACGGTACTCGT) or sgRNA targeting HMGCS1(sgHMGCS1: AGCAGCGGTCTAATGCACTG). After sorting of MSLN + cells, cells were expanded, and deletion of HMGCS1 was verified by immunoblot analysis.

Mice and tumor murine xenograft models

For the human ovarian cancer model, female C-NKG (NOD-scid IL2Rγnull) mice (Cyagen (Suzhou) Biosciences Inc) were used under a protocol approved by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University (IACUC-2024234). Mice were maintained under specifc pathogen-free conditions for 3 days, then an equal number of OVCAR3 cells (5 × 106/per mouse) were subcutaneously implanted on the right of the same C-NKG mice. Sixteen days later, mice were randomly assigned (6 mice per group), then, 1 × 106 CAR-T or CAR-T + Gln cells were administered intravenously. On day 4,8,12,16,20 post CAR T cell infusion, peripheral blood were collected from each of the mice. Blood was immediately into heparin sodium tubes. The cells were measured by flow cytometry analysis. The body weight and tumor volum was measured and health of mice was monitored. Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated as: Volume = (L × W2)/2, where L represents the longest diameter and W the perpendicular shorter diameter of the tumor. When the physical and behavior health of mice declined below the levels established or Tumor volume greater than 2000 mm3, mice were euthanized.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining

Mouse tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 h at 4 °C, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in paraffin. Tissue Sects. (5 µm) were cut and mounted on glass slides. For IHC, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H₂O₂, and nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% BSA. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were developed using DAB substrate, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. For H&E staining, sections were stained with hematoxylin, differentiated in acid alcohol, and counterstained with eosin. All sections were dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and mounted with neutral balsam. Images were acquired using a 3DHISTECH Panoramic slide scanner and CaseViewer software.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Quantification of western blots data was conducted with ImageJ software. Flow cytometry was quantified using FlowJo v10 software. Statistical analyses for significant differences were performed with Prism 8 (GraphPad Software). For comparisons between two groups (in both in vitro and in vivo experiments), an unpaired Student’s t test was used, and a paired Student’s t-test is used in biological replicates or independent experiments; for more than two groups, a one-way ANOVA multiple comparison test was applied. two-way ANOVA was applied to analyze grouped data that have two independent categorical variables, such as time and treatment. Survival curves were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method. The log rank test was used for survival statistical analysis. Results were represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD, technical replicates) and mean ± standard error of mean (SEM, biological replicates or independent experiments). A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

Results

Glutamine enhances CAR-T cell function in ovarian cancer models

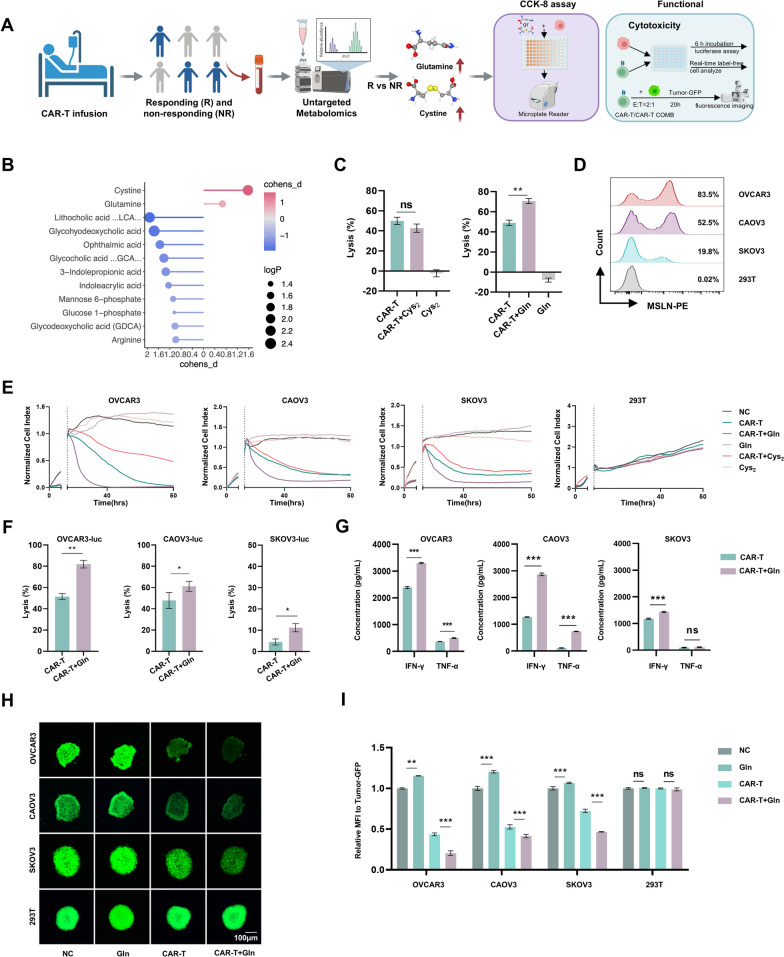

Our investigation into metabolic determinants of CAR-T cell efficacy began with non-targeted metabolomic profiling of peripheral blood samples from epithelial ovarian cancer patients undergoing MSLN-directed CAR-T therapy (Fig. 1A). Comparative analysis between objective responders and non-responders identified two amino acids (glutamine and cysteine) with significant differential abundance in the responder cohort (Fig. 1B), suggesting their dual potential as predictive biomarkers and functional mediators of therapeutic response.

Fig. 1.

Non-targeted metabolomics screening of clinical samples identifies glutamine as a key enhancer of CAR-T cell anti-tumor activity. A Schematic of the metabolites screening process from clinical samples to in vitro experiments. The process includes the use of CCK8 to measure the inhibition rate of OVCAR3 cells treated with cysteine and glutamine, followed by the analysis of the anti-tumor activity of CAR-T cells after metabolites treatment. B Non-targeted metabolomics analysis of patient blood samples after CAR-T infusion (n = 4 patients). The analysis reveals higher levels of glutamine and cysteine abundance in the blood of CAR-T responders compared to non-responders. Responders were defined as patients who experienced a ≥ 30% reduction in tumor size following MSLN-CAR-T cell therapy, as per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1). Non-responders were defined as patients with less than a 30% reduction in tumor size or disease progression. C Short-term cytotoxicity against ovarian cancer lines (OVCAR3-luc). CAR-T cells were pretreated with glutamine (5 mM) or cystine (1 mM) for 2 days, followed by a 6 h co-culture with tumor cells at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:2. D Flow cytometry analysis of MSLN antigen expression in target cells (OVCAR3, CAOV3, SKOV3) and non-target cells (293 T). E CAR-T cells were pretreated with glutamine (5 mM) or cystine (1 mM) for 2 days. Real-time monitoring of CAR-T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Tumor-killing kinetics of CAR-T cells were measured over 50 h with impedance recorded at 28 s intervals during co-culture with ovarian cancer cell lines (OVCAR3, CAOV3, SKOV3, 293 T) at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:8. The normalized cell index was used to assess the kinetics of cell lysis. F Short-term cytotoxicity against ovarian tumor lines (OVCAR3, CAOV3, SKOV3-luc). CAR-T cells were pretreated with glutamine (2 mM or 5 mM) for 2 days, followed by a 6 h co-culture with tumor cells at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:2. G Flow cytometry analysis of TNF-α and IFN-γ secretion by CAR-T cells following 6 h co-culture with tumor cells (OVCAR3, CAOV3 and SKOV3). H, I Tumor microsphere cleavage assay: GFP-labeled tumor spheroids co-cultured with CAR-T cells for 20 h; representative fluorescence images (J, scale bar: 100 µm) and quantitative cleavage efficiency (K) are shown. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (t test and two-way ANOVA)

Based on these clinical findings, we systematically evaluated the functional impact of glutamine and cystine pretreatment on CAR-T cell antitumor activity. First, we constructed and validated MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells (Figure S1A-S1C), and determined the effective, non-toxic concentrations of cystine and glutamine using CCK-8 assays (Figure S1D-S1E). In vitro coculture assays revealed that glutamine-pretreated (5 mM) CAR-T cells exhibited significantly enhanced cytotoxicity against MSLN + ovarian cancer cells compared to untreated controls (Fig. 1C). Target specificity was confirmed by flow cytometric analysis of MSLN expression across cell lines (Fig. 1D). Real-time cytotoxicity monitoring further demonstrated superior tumor-killing kinetics in glutamine-primed CAR-T cells (Fig. 1E). In contrast, pretreatment with cystine (1 mM) did not enhance the antitumor activity of CAR-T cells (Fig. 1C and E).

Having established that glutamine pretreatment significantly improved the tumor lytic capacity of CAR-T cells against three ovarian cancer lines (OVCAR3, CAOV3, and SKOV3) (Fig. 1F), we next investigated the underlying immune mechanisms. Multiparametric flow cytometry analysis of co-culture supernatants revealed that glutamine-primed CAR-T cells consistently exhibited elevated cytokine production upon engagement with all three tumor lines (Fig. 1G). This cytokine boost correlated strongly with the enhanced tumor clearance observed in Fig. 1F. To better recapitulate the spatial complexity of solid tumors, we employed a GFP-labeled 3D tumor spheroid cleavage assay. CAR-T cells exhibited markedly improved tumor penetration and destruction (Fig. 1H and I). Collectively, these data demonstrate that glutamine enhances CAR-T cell function across multiple dimensions, including cytotoxicity, cytokine secretion, and spatial tumor control.

Glutamine pretreatment enhances CAR-T cells metabolic activity and reduces exhaustion

To explore the impact of glutamine pretreatment on CAR-T cell metabolism and functionality, we assessed a range of phenotypic and functional markers across different glutamine concentrations (Fig. 2A). Figure 2B show the expression levels of CAR in CAR-T cells under various glutamine concentrations. The results demonstrated that glutamine pretreatment significantly increased CAR expression, suggesting enhanced CAR-T cell activation.

Fig. 2.

Glutamine enhances metabolic activity and functional phenotypes of CAR-T cells. A Schematic of experimental: Analysis of metabolic and functional phenotypes in CAR-T cells. CAR-T cells were pretreated with glutamine (2 or 5 mM) for 2 days. B CAR expression levels in CAR-T cells were detected by flow cytometry after co-incubation with 2 or 5 mM glutamine for 2 days. C Intracellular ATP levels in CAR-T cells after co-incubation with 2 or 5 mM glutamine for 2 days. D Flow cytometry analysis of CAR-T cell subsets after glutamine pre-treatment. The gating strategy for memory phenotype identification was as follows: (1) live cell populations were gated, with a negative gate established using CAR-T cells without antibody staining; (2) single staining for CD45RA and CCR7 was used to define positive gates; (3) a double staining for CD45RA and CCR7 was applied to identify the subsets: TSCM (CD45RA + CCR7 +), TCM (CD45RA – CCR7 +), TEM (CD45RA – CCR7 –), and TEFF (CD45RA + CCR7 –). E Co-expression level of exhaustion-related inhibitory receptors (PD – 1and TIM – 3) in CAR-T cells after co-incubation with 2 or 5 mM glutamine for 2 days. The co-expression of PD-1 and TIM-3 was quantified as the percentage of double-positive cells (PD – 1 + TIM – 3 +) within the live CAR-T cell population. The gating strategy involved defining the live cell population and identifying PD-1 and TIM-3 positive cells. F ROS levels in CAR-T cells by flow cytometry. G Apoptosis analysis of CAR T cells by flow cytometry. H On Day 4, CAR-T cells were labeled with CFSE, and after two days of treatment with 2 mM or 5 mM glutamine, cell proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry. I Flow-cytometric analysis of activation (CD25 and CD69) in CAR-T cells after treatment with glutamine (2/5 mM). J, K Mitochondrial function and glycolysis: (J) Measurement of oxygen consumption rates (OCRs); (K) Seahorse glycolytic stress test showing glycolytic capacity of CAR-T and CAR-T + Gln cells. L α-KG levels in CAR-T cells. Glutamine pretreatment (5 mM, 48 h) significantly increased intracellular α-KG concentration compared to untreated controls. Measured by Amplex Red-based enzymatic assay. M NAD +/NADH ratio in CAR-T cells. Glutamine-treated cells showed elevated NAD +/NADH ratio, indicating improved redox state. Quantified by WST-8 enzymatic cycling assay. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (t test)

Next, we examined the metabolic activity of CAR-T cells by measuring intracellular ATP levels (Fig. 2C). CAR-T cells supplemented with glutamine exhibited significantly higher ATP levels compared to those cultured under standard conditions, indicating an improvement in cellular metabolism. We further analyzed the memory phenotype of CAR-T cells by flow cytometry, focusing on central memory (CM) and effector memory (EM) subsets (Fig. 2D). Glutamine pretreatment promoted a higher proportion of both CM and EM subsets, suggesting that glutamine enhances the formation of long-lived, functional CAR-T cells.

Additionally, we evaluated the expression of exhaustion-related inhibitory receptors such as PD-1 and TIM-3 in CAR-T cells (Fig. 2E). Our results showed that glutamine pretreatment reduced the co-expression of these exhaustion markers, indicating that glutamine may help mitigate CAR-T cell exhaustion and improve persistence.

To assess oxidative stress, we measured reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in CAR-T cells under different glutamine concentrations (Fig. 2F). The data revealed that glutamine treatment significantly reduced ROS levels in CAR-T cells, suggesting a reduction in oxidative stress and improved cellular health. Further, we evaluated apoptosis in CAR-T cells by using 7-AAD and Annexin V staining (Fig. 2G). Glutamine-treated CAR-T cells exhibited significantly lower apoptosis levels, demonstrating enhanced cell survival.

We also examined CAR-T cell proliferation using CFSE staining, with flow cytometry analysis showing that CAR-T cells cultured with glutamine proliferated more efficiently compared to the control group (Fig. 2H). Moreover, activation markers such as CD25 and CD69 were significantly upregulated in glutamine-treated CAR-T cells, confirming enhanced CAR-T cell activation (Fig. 2I).

In contrast, CAR-T cells cultured with no glutamine (0 mM) or high concentrations of glutamine (10 mM) showed a certain degree of impairment. Specifically, these conditions led to a decrease in memory phenotype (Figure S1A), an increase in exhaustion markers (Figure S1B), elevated ROS levels (Figure S1C), and higher apoptosis levels (Figure S1D). These findings suggest that both the absence of glutamine and excessive glutamine concentrations may negatively impact CAR-T cell functionality, highlighting the importance of optimizing glutamine concentration for enhancing CAR-T cell efficacy.

Finally, we assessed mitochondrial function and glycolysis in CAR-T cells using Seahorse assays. Figure 2J shows a significant increase in oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in glutamine-treated CAR-T cells, indicating enhanced mitochondrial respiration. Figure 2K displays the results from the glycolytic stress test, which showed that glutamine pretreatment increased the glycolytic capacity of CAR-T cells, supporting enhanced metabolic flexibility and energy production.

Finally, we performed comprehensive metabolic characterization of CAR-T cells. Glutamine-treated CAR-T cells showed a significant increase in OCR (indicating enhanced mitochondrial respiration, Fig. 2J), as well as improvements in key glycolytic parameters such as glycolytic reserve and compensatory glycolysis (Fig. 2K and Figure S1E-S1H). This indicates that glutamine pretreatment promotes a shift in CAR-T cell metabolism, enhancing mitochondrial respiration and oxidative phosphorylation, while still maintaining a strong reliance on glycolysis for ATP production (Figure S1I-S1O). Metabolite analysis revealed glutamine-induced increases in α-KG (Fig. 2L) and NAD +/NADH ratio (Fig. 2M), enhancing TCA cycle activity and redox homeostasis to improve CAR-T cell memory formation (CD45RA + CCR7 +) while reducing exhaustion markers (PD-1/TIM3) [35,36].

Together, these findings demonstrate that moderate glutamine pretreatment significantly enhances the metabolic activity and functional phenotypes of CAR-T cells, including increased CAR expression, enhanced proliferation, reduced exhaustion and apoptosis, improved memory formation, and enhanced mitochondrial and glycolytic function.

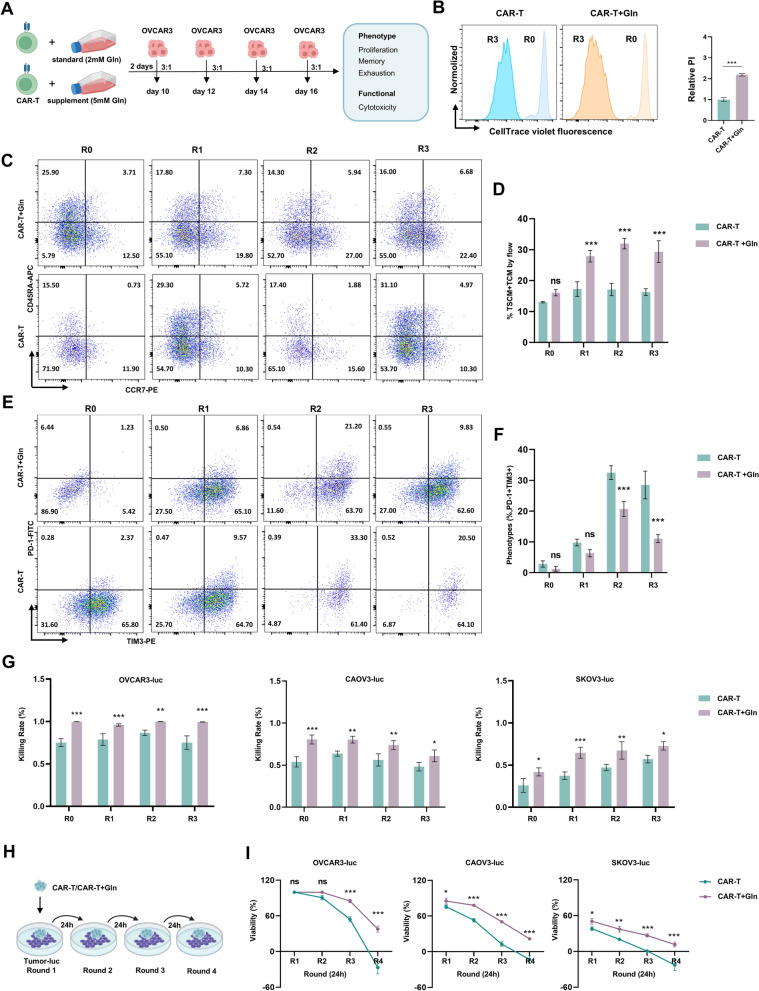

Glutamine pretreatment enhances CAR-T cell anti-tumor activity in vitro

To evaluate the effect of glutamine pretreatment on the anti-tumor activity of CAR-T cells, we performed a series of tumor stimulation experiments using OVCAR3 ovarian cancer cells. CAR-T cells with and without glutamine pretreatment (CAR-T and CAR-T + Gln cells) were co-cultured with OVCAR3 cells at an effector-to-target (E/T) ratio of 3:1 every 24 h (Fig. 3A). After three rounds of stimulation, proliferation capacity of CAR-T and CAR-T + Gln cells was assessed (Fig. 3B). The results demonstrated that glutamine pretreatment significantly enhanced the proliferation of CAR-T cells, indicating that glutamine supports their survival and expansion during repeated tumor challenges.

Fig. 3.

Glutamine enhances anti-tumor activity of CAR-T cells by reducing exhaustion. A Schematic of serial tumor stimulation. CAR-T or CAR-T + Gln cells were co-cultured with OVCAR3 cells (E/T ratio 3:1) for 24 h, followed by three cycles of re-culture. CAR-T cells were analyzed for phenotype and cytotoxicity after each cycle. B Proliferation capacity of CAR-T and CAR-T + Gln cells after three rounds of OVCAR3 stimulation. C, D Continuous evaluation of central memory subset in CAR-T and CAR – T + Gln cells was performed after 24 h OVCAR3 stimulation for each round. CAR-T cell purity was confirmed using CAR-specific antibody staining. E, F Continuous evaluation of PD-1 and TIM3 expression in CAR-T and CAR – T + Gln cells was performed after 24 h OVCAR3 stimulation for each round. CAR-T cell purity was confirmed using CAR-specific antibody staining. G Cytotoxicity of CAR-T and CAR – T + Gln cells after serial stimulation by OVCAR3-luc, CAOV3-luc and SKOV3-luc. H, I Sustained cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells. Schematic of CAR-T cells undergoing repetitive antigen stimulation (H) and their serial killing capacity against tumor cell lines (OVCAR3, CAOV3 and SKOV3-luc) in 24 h interval assays at E:T = 2:1. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant by t test or two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test

Next, we assessed the effects of glutamine on the central memory subset of CAR-T cells, which is essential for long-term anti-tumor immunity. Results show that glutamine pretreatment significantly increased the proportion of central memory CAR-T cells after each round of 24 h OVCAR3 stimulation (Fig. 3C, D), suggesting that glutamine enhances the formation and maintenance of a long-lasting memory phenotype.

We also examined the expression of exhaustion markers PD-1 and TIM-3, which are associated with reduced CAR-T cell function during chronic tumor exposure. Glutamine pretreatment significantly reduced the expression of PD-1 and TIM-3 on CAR-T cells after each round of OVCAR3 stimulation (Fig. 3E, F), indicating that glutamine helps mitigate CAR-T cell exhaustion, thus improving their functional persistence. To confirm that the memory subset changes (Fig. 3C–F) were intrinsic to CAR-T cells, we assessed purity using CAR-specific flow cytometry (Figure S3A-S3B). These results validate that the observed phenotypic shifts reflect true CAR-T cell adaptations rather than non-specific cellular interference.

To assess the cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells under repeated stimulation, we performed cytotoxicity assays with three ovarian cancer cell lines: OVCAR3-luc, CAOV3-luc, and SKOV3-luc. Results shows that CAR-T + Gln cells exhibited significantly higher cytotoxicity against all three tumor cell lines compared to control CAR-T cells after serial stimulation (Fig. 3G), demonstrating that glutamine pretreatment enhances CAR-T cell anti-tumor activity.

Finally, we evaluated the sustained cytotoxicity of CAR-T cells after repeated antigen stimulation. As illustrated in Fig. 3H, CAR-T cells were subjected to repetitive stimulation with tumor cells at 24-h intervals. The results indicate that CAR-T + Gln cells maintained higher serial killing capacity against OVCAR3, CAOV3, and SKOV3-luc cells compared to control CAR-T cells (Fig. 3I). Importantly, this enhanced cytotoxic activity correlated with significantly increased production of effector cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α) in CAR-T + Gln cells (Figure S3C-S3E), demonstrating their improved functional capacity at both the killing and secretory levels. These findings collectively support that glutamine pretreatment improves CAR-T cells’ ability to continuously target and kill tumor cells.

In summary, these results demonstrate that glutamine pretreatment significantly enhances the anti-tumor activity of CAR-T cells by improving their proliferation, memory phenotype, and cytotoxicity, while reducing exhaustion markers. This suggests that glutamine pretreatment may be a valuable strategy to optimize CAR-T cell therapy, particularly for solid tumors like ovarian cancer.

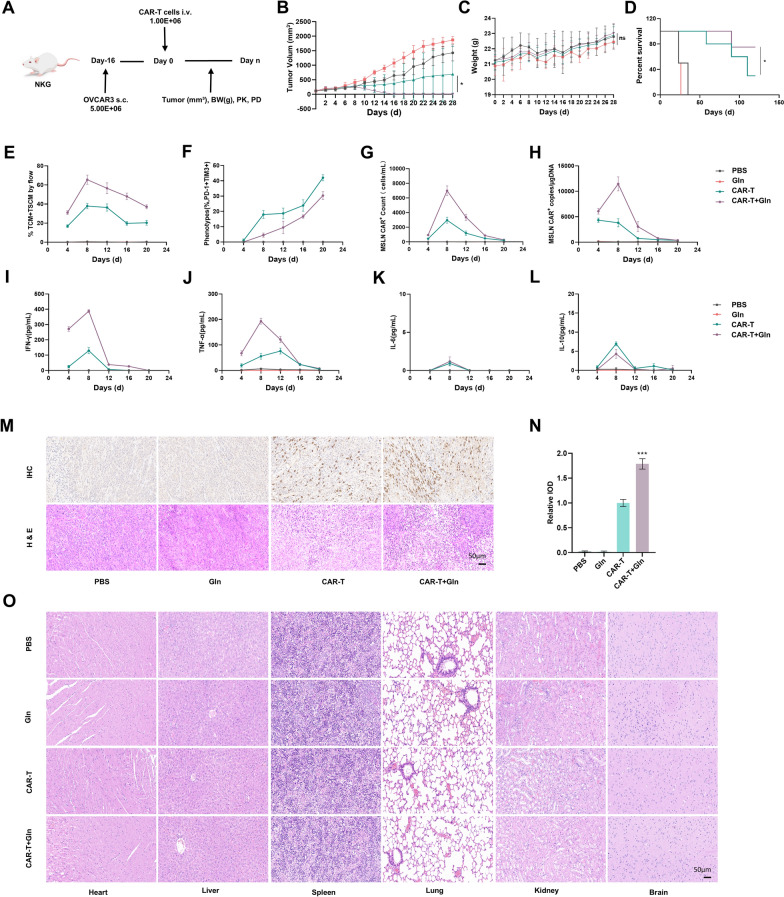

Glutamine pretreatment improves CAR-T Cell efficacy in vivo

In vivo experiments were conducted using an ovarian cancer xenograft model established by subcutaneously inoculating NKG mice with OVCAR3 cells (Fig. 4A). Mice were treated with either conventionally cultured CAR-T cells (2 mM glutamine) or CAR-T cells cultured in medium supplemented with 5 mM glutamine. Tumor volume and body weight were measured every two days, and survival was monitored. Our results showed that CAR-T + Gln cells exhibited superior antitumor activity compared with CAR-T cells (Fig. 4B–D).

Fig. 4.

Glutamine enhanced antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cells in vivo. A Schematic illustration of experimental protocol in vivo. NKG mice were intravenously (i.v.) injected with OVCAR3 cells and infused with CAR-T or CAR-T + Gln cells 16 days later. Tumor burden was assessed every 2 days. The peripheral blood were collected for analysis on day 4, 8, 12, 16, 20. B Tumor growth curves measured every two days (n = 6). The length (L) and width (W) of the tumors were measured every two days by caliper, and tumor volume was calculated using the standard formula: Tumor Volume (mm3) = L × W2/2. C Weight of mice measured every two days (n = 6). D Survival of NKG mice i.v. infused with CAR-T or CAR-T + Gln cells (n = 6 mice/group). E Frequency of central memory CAR-T cells remained in the peripheral blood from different groups (n = 3). F Co-expression level of inhibitory receptors (PD-1 and TIM3) in CAR-T cells in the peripheral blood from different groups (n = 3). G Numbers of CAR-T cells remained in the peripheral blood from different groups (n = 3). H MSLN + CAR copies in peripheral blood from different groups (n = 3). I–L Cytokine levels (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10) in tumor tissues measured using Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) (n = 3). M Representative immunohistochemical staining for CD45 (brown) and corresponding hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining on day 8 (n = 3). Scale bars: 50 µm. N Quantitative analysis of CD45 + cell relative Integrated Optical Density (IOD) (n = 3). O Representative H&E staining of tissues at Day 28 endpoint in mouse model. At the Day 28 endpoint, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and brain tissues were collected from the mouse model and subjected to H&E staining. The results show no significant tissue damage, indicating the safety of the treatment. The log-rank test was used for the survival analysis (D). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Blood samples collected on days 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 post-infusion were analyzed by flow cytometry, revealing a higher proportion of memory T cell subsets (CD45RA-CCR7 + and CD45RA-CCR7-) (Fig. 4E and Figure S4A) and a lower exhaustion markers (PD-1 and TIM-3) (Fig. 4F and Figure S4B) in the CAR-T + Gln group. Flow cytometry results showed a higher number of CAR-T cells in the circulating blood of the CAR-T + Gln group (Fig. 4G). This finding was further supported by qPCR analysis, which also demonstrated an increase in CAR gene copies in this group (Fig. 4H). Serum cytokine analysis showed elevated levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 4I–J), with no significant increase in IL-6 or IL-10 (Fig. 4K, L). This was associated with faster tumor regression and no significant weight loss in the CAR-T + Gln group, suggesting that the enhanced cytokine response contributes to improved therapeutic efficacy without compromising overall health. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated enhanced tumor infiltration by CAR-T + Gln cells (Fig. 4M,N). Furthermore, histopathological examination (H&E staining) of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and brain) on day 28 post-treatment revealed no significant tissue damage (Fig. 4O). Complete blood counts and serum biochemistry analyses (including ALT, CREA, and BUN) showed no abnormalities in all treatment groups (Table S1 and Table S2), collectively demonstrating the absence of hematologic, hepatic or renal toxicity associated with glutamine-pretreated CAR-T cell therapy and indicating a favorable safety profile. These results collectively demonstrate that 5 mM glutamine pretreatment enhances the in vivo anti-tumor efficacy and persistence of CAR-T cells without significant side effects.

Glutamine enhances CAR-T cell function via the mTOR-SREBP2 axis and HMGCS1 upregulation

To understand how glutamine modulates CAR-T cell metabolism and function, we focused on key metabolic pathways involved in glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and amino acid metabolism, which are essential for supporting the energy demands of activated immune cells. We first conducted qPCR analyses on CAR-T and CAR-T + Gln cells to evaluate the expression of genes associated with these metabolic pathways. Our results revealed that glutamine pretreatment led to a significant upregulation of several key genes, particularly HMGCS1, mTOR, and SREBP2, which play crucial roles in energy production, cholesterol biosynthesis, and immune function. Notably, the expression of HMGCS1, a key enzyme involved in cholesterol synthesis, was particularly enhanced (Fig. 5A and Figure S5A-S5Y).

Fig. 5.

Glutamine enhances CAR-T cell function through the mTOR-SREBP2 axis by upregulating HMGCS1. A qPCR analysis of key metabolic genes: Glutamine pretreatment significantly upregulated the expression of key enzymes involved in gGlutamine metabolism, glucose metabolism and lipid metabolism in CAR-T cells, especially HMGCS1, MTOR, and SREBP2. B Immunoblot analysis of HMGCS1 and TBB5 in CAR-T and CAR-T + Gln cells. kDa, kilodaltons. C Effect of mTOR inhibition on gene expression: Treatment with the mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin) resulted in a significant downregulation of MTOR, SREBP2 and HMGCS1. D Immunoblot analysis of HMGCS1 and TBB5 in control and HMGCS1-deficient CAR-T cells. E Real-time cytotoxicity assay: HMGCS1 knockout abrogates glutamine-enhanced CAR-T cell antitumor activity. F–K HMGCS1 knockout reverses glutamine-induced phenotypic alterations in CAR-T cells: (F) Detection of CAR-T memory phenotype by flow cytometry. G Detection of CAR-T exhaustion phenotype by flow cytometry. H Detection of CAR-T activation phenotype by flow cytometry. I ATP production in CAR-T cells. J CFSE-based proliferation analysis of CAR-T cells. (K) Apoptosis levels in CAR-T cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by t test or one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

To further investigate the molecular basis of this upregulation, we used Western blotting to confirm the increased protein levels of HMGCS1 in CAR-T + Gln cells (Fig. 5B). These findings prompted us to hypothesize that HMGCS1 expression might be regulated through the mTOR-SREBP2 axis, a known pathway involved in lipid and cholesterol metabolism. To test this hypothesis, we treated CAR-T + Gln cells with an mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin), which led to a significant downregulation of MTOR, SREBP2 and HMGCS1 gene levels (Fig. 5C). This result supports our hypothesis that glutamine enhances CAR-T cell function through the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 pathway.

Additionally, we performed HMGCS1 knockout experiments in CAR-T cells to directly assess the functional consequences of HMGCS1 inhibition (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, despite the addition of glutamine, HMGCS1 knockout CAR-T cells showed no enhanced anti-tumor activity (Fig. 5E). Moreover, their cell phenotypes, including memory markers, exhaustion markers, activation levels, and apoptosis, as well as their proliferation and ATP production (Fig. 5F–K), reverted to baseline levels, indicating that HMGCS1 is essential for the metabolic reprogramming induced by glutamine and for the subsequent enhancement of CAR-T cell function. In addition to the key metabolic regulators in the glutamine-mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis, we observed significant upregulation of GOT1, a critical enzyme in the malate-aspartate shuttle [37]. Given its role in mitigating oxidative stress by maintaining NAD +/NADH balance [35,38,39], elevated GOT1 expression may contribute to enhanced antioxidant capacity in CAR-T cells, which is consistent with our observation of decreased reactive oxygen species levels in CAR-T cells.

These results collectively demonstrate that glutamine pretreatment enhances CAR-T cell anti-tumor activity through the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis, which modulates lipid biosynthesis, stabilizes cell membranes, and promotes the formation of immune synapses, crucial for the improved CAR-T cell functionality observed in our study.

Discussion

This study elucidates the mechanistic basis by which glutamine pretreatment potentiates CAR-T cell functionality through metabolic reprogramming. Our findings demonstrate that glutamine enhances multiple critical aspects of CAR-T cell biology, including metabolic activity, memory phenotype maintenance, and cytotoxic potential, while simultaneously reducing exhaustion markers. Crucially, we identify the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis as the central pathway mediating these effect, linking glutamine metabolism to cholesterol biosynthesis and membrane stability in CAR-T cells.

The observed upregulation of HMGCS1, a rate-limiting enzyme in the mevalonate pathway [40], emerges as a pivotal molecular event underlying glutamine's beneficial effects. Pharmacological inhibition experiments using rapamycin established the essential role of mTOR signaling in regulating HMGCS1 expression [41–43], with mTOR blockade abrogating the functional improvements conferred by glutamine pretreatment. Complementary genetic evidence from HMGCS1 knockout studies further corroborated its indispensable role in maintaining CAR-T cell functionality, particularly in preserving membrane integrity and immune synapse formation.

These findings significantly advance our understanding of metabolic regulation in adoptive cell therapy. The demonstrated dependence of CAR-T cells on glutamine-driven cholesterol biosynthesis highlights a previously underappreciated metabolic vulnerability that could be therapeutically exploited. Notably, the selective efficacy of glutamine, as opposed to cysteine, underscores the unique position of glutamine metabolism in supporting T cell effector functions during sustained anti-tumor responses. Importantly, when compared to other metabolic interventions, glutamine preconditioning demonstrates distinct advantages: while glycolysis enhancement boosts effector function but may impair memory formation [44], and fatty acid oxidation supports persistence but risks lipid overload [45], glutamine uniquely balances energy production, redox homeostasis, and membrane biosynthesis—properties critical for sustained solid tumor responses.

While our study focused on glutamine monotherapy, emerging evidence suggests potential synergies with existing ovarian cancer treatments. Preclinical studies demonstrate that metabolic modulation can enhance CAR-T cell responsiveness to PD-1 blockade [46], while glutaminase inhibitors show additive effects with platinum chemotherapy [47]. Notably, our observed metabolic reprogramming—particularly enhanced oxidative phosphorylation—may help CAR-T cells withstand replicative stress induced by PARP inhibitors [48], while glutamine-derived α-KG could maintain NAD + homeostasis in the immunosuppressive microenvironment created by DNA damage response [36]. However, optimal sequencing and dosing regimens require systematic evaluation to avoid metabolic competition or overlapping toxicities. Future studies should explore these combinations while considering patient-specific metabolic profiles.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies highlighting the critical role of metabolic rewiring in optimizing CAR-T function. For instance, previous reports have demonstrated that mitochondrial programming [49], cholesterol synthesis [50], and glutamine transport [51,52] contribute to T cell persistence and antitumor activity. However, our study uniquely delineates the glutamine-mediated activation of the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis and its direct contribution to membrane stability and immune synapse formation, specifically in the context of ovarian cancer. In addition, our metabolomic findings complement prior observations [53], underscoring the translational relevance of glutamine metabolism in shaping CAR-T cell responses. From a translational perspective, our results suggest that in vitro glutamine preconditioning (5 mM, 48 h) enhances CAR-T cell functionality through metabolic optimization, suggesting a viable strategy to overcome current limitations in solid tumor therapy. However, clinical translation requires addressing three critical challenges: (1) Patient metabolic heterogeneity that may necessitate personalized preconditioning protocols; (2) Dynamic tumor microenvironment interactions that could modulate therapeutic outcomes; and (3) Standardization of GMP-compliant manufacturing processes for consistent product quality. Future phase I trials should prioritize safety evaluation while incorporating metabolomic profiling to optimize treatment regimens. These preclinical results provide mechanistic justification for developing"metabolically enhanced"CAR-T clinical trials targeting solid tumors.

Future investigations should focus on (1) clinical translation of glutamine preconditioning protocols, (2) identification of TME-derived triggers (e.g., cytokines, hypoxia) activating the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis, and (3) validation of HMGCS1 as a potential predictive biomarker. These mechanistic and translational insights may inform the development of synergistic therapeutic strategies to potentiate CAR-T cell efficacy against solid tumors.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study reveals that glutamine pretreatment significantly enhances CAR-T cell functionality through metabolic reprogramming, specifically by activating the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis. This pathway links glutamine metabolism to cholesterol biosynthesis, membrane stability, and immune synapse formation, all of which are crucial for CAR-T cell efficacy. We demonstrate that glutamine promotes CAR-T cell activation, persistence, and anti-tumor activity while reducing exhaustion markers, offering a novel metabolic strategy to improve CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors. Our findings also highlight the selective role of glutamine, as opposed to cysteine, in supporting T cell effector functions during sustained anti-tumor responses. These results provide a promising foundation for future clinical studies aiming to optimize CAR-T cell therapies through metabolic interventions, potentially overcoming current challenges in treating solid tumors such as ovarian cancer.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Construction of MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells and determination of cystine and glutamine sensitivity in OVCAR3 cells.Schematic diagram of the MSLN-targeted CAR structure.Workflow for the generation of CAR-T cells: PBMCs were isolated from healthy donors, followed by T cell enrichment, activation, lentiviral transduction with MSLN-CAR, and sorting of CAR-expressing cells by flow cytometry.Flow cytometric analysis of MSLN expression in T cells 3 days post-transduction confirms successful generation of MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells.CCK-8 assay assessing the dose-response of OVCAR3 cells to cystine after 48 h of treatment with increasing concentrations; IC50 = 2.277 mM.CCK-8 assay assessing the dose-response of OVCAR3 cells to glutamine after 48 h of treatment with increasing concentrations; IC50 = 36.5 mM. Figure S2. Dose-dependent effects of glutamine on CAR-T cell metabolism and phenotypes.Flow cytometry analysis of memoryand exhaustionmarkers in CAR-T cells cultured with 0 mM, or 10 mM glutamine for 2 days.Intracellular ROS levelsand apoptosisin CAR-T cells under 0/10 mM glutamine conditions.Glycolytic profile analysis showing: %PER from Glycolysis, Basal glycolysis, Glycolytic reserve, Compensatory glycolysis. in CAR-T cells cultured with 2 mMor 5 mM glutamine.Mitochondrial respiration parameters: Basal respiration, Maximal respiration, Spare respiratory capacity, ATP production, Proton leak.Metabolic balance indicators: ECAR/OCR ratio, %ATP from glycolysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Figure S3. Glutamine pretreatment maintains CAR-T cell purity and enhances cytokine secretion during repeated tumor stimulation.Purity of CAR-T and CAR-T+Gln cells population after multiple rounds of OVCAR3 stimulation. Representative flow cytometry plots showing CAR expressionin CAR-T cells after each round of OVCAR3 stimulation.Cytokine levels in co-culture supernatants measured by ELISA after four rounds of stimulation. IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α secretion by CAR-T cells co-cultured with ovarian cancer cell lines, CAOV3, SKOV3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by 2way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Figure S4. Glutamine pretreatment sustains memory-like phenotype and reduces exhaustion in circulating CAR-T cells.Representative flow cytometry plots showing: Memory phenotype: CD45RA+CCR7+ cells, Exhaustion markers: PD-1+TIM-3+ cells. In CAR-T+Gln-treated vs. control CAR-T cells at indicated timepoints. Figure S5. Quantitative analysis of metabolic gene expression in CAR-T cells following glutamine pretreatment.Bar graph showing the relative mRNA expression levels of 25 key metabolic genes related to glutamine, glucose, and lipid metabolism in control and glutamine-pretreated CAR-T cells, as determined by qPCR. Glutamine pretreatment significantly enhanced the expression of multiple metabolic genes, particularly those in the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis, including MTOR, SREBP2, and HMGCS1, suggesting activation of a metabolic reprogramming pathway. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Chen Jiannan: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Zhao Lianfeng: Methodology, Validation; Li Wenying: Validation, Writing – original draft; Wang Shuai: Data curation, Investigation; Li Jiayi: Data curation, Investigation; Lv Zhongyuan: Validation; Zhao Yaoyao: Methodology; Liang Junqing: Conceptualization, Resources; Hu Zhigang: Supervision; Pan Feiyan: Supervision; He Lingfeng: Supervision; Gu Lili: Supervision; Guo Zhigang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82373183) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Availability of data and material

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University and the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University (IACUC-2024234) for animal studies. All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in the clinical trial.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented to the publication of the research findings.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jiannan Chen, Lianfeng Zhao and Wenying Li have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jiannan Chen, Email: cjn.njnu@foxmail.com.

Zhigang Guo, Email: 08278@njnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Mailankody S, et al. Allogeneic BCMA-targeting CAR T cells in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: phase 1 UNIVERSAL trial interim results. Nat Med. 2023;29:422–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan Z, et al. A combination of humanised anti-CD19 and anti-BCMA CAR T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daei S, et al. The current landscape of CAR T-cell therapy for solid tumors: mechanisms, research progress, challenges, and counterstrategies. Front Immunol. 2023. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1113882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoutrop E, et al. Mesothelin-specific CAR T cells target ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2021;81:3022–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh BLZ, et al. Fratricide-resistant CD7-CAR T cells in T-ALL. Nat Med. 2024;30:3687–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konstantinopoulos PA, Matulonis UA. Clinical and translational advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:1239–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song M, et al. IRE1α-XBP1 controls T cell function in ovarian cancer by regulating mitochondrial activity. Nature. 2018;562:423–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Targeting glutamine dependence through GLS1 inhibition suppresses ARID1A-inactivated clear cell ovarian carcinoma—PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34085048/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Zhai X, Mao L, Wu M, Liu J, Yu S. Challenges of anti-mesothelin CAR-T-cell therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faust, J. R., Hamill, D., Kolb, E. A., Gopalakrishnapillai, A. & Barwe, S. P. Mesothelin: An Immunotherapeutic Target beyond Solid Tumors. Cancers (Basel)14, 1550 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Schoutrop E, et al. Tuned activation of MSLN-CAR T cells induces superior antitumor responses in ovarian cancer models. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11: e005691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klampatsa A, Dimou V, Albelda SM. Mesothelin-targeted CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2021;21:473–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maalej KM, et al. CAR-cell therapy in the era of solid tumor treatment: current challenges and emerging therapeutic advances. Mol Cancer. 2023. 10.1186/s12943-023-01723-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flugel CL, et al. Overcoming on-target, off-tumour toxicity of CAR T cell therapy for solid tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:49–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Q, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors: master regulators of hypoxic tumor immune escape. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akbari B, et al. Metabolic and epigenetic orchestration of (CAR) T cell fate and function. Cancer Lett. 2022;550: 215948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan JD, et al. FOXO1 enhances CAR T cell stemness, metabolic fitness and efficacy. Nature. 2024;629:201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li S, et al. Glutamine metabolism in breast cancer and possible therapeutic targets. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;210: 115464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen L, et al. Metabolic reprogramming by ex vivo glutamine inhibition endows CAR-T cells with less-differentiated phenotype and persistent antitumor activity. Cancer Lett. 2022;538: 215710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen C, et al. Mitochondrial metabolic flexibility is critical for CD8+ T cell antitumor immunity. Sci Adv. 2023;9: eadf9522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin J, Byun JK, Choi YK, Park KG. Targeting glutamine metabolism as a therapeutic strategy for cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:706–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han X, et al. Activation of polyamine catabolism promotes glutamine metabolism and creates a targetable vulnerability in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121: e2319429121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang B, Pei J, Xu S, Liu J, Yu J. A glutamine tug-of-war between cancer and immune cells: recent advances in unraveling the ongoing battle. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McPhedran SJ, Carleton GA, Lum JJ. Metabolic engineering for optimized CAR-T cell therapy. Nat Metab. 2024;6:396–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, Zhang H. Reprogramming of glucose, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism for cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:377–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan C, et al. Exhaustion-associated cholesterol deficiency dampens the cytotoxic arm of antitumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1276-1293.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodineau C, Tomé M, Murdoch PDS, Durán RV. Glutamine, MTOR and autophagy: a multiconnection relationship. Autophagy. 2022;18:2749–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hua H, et al. Targeting mTOR for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Düvel K, et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell. 2010;39:171–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao S, et al. MIEF2 reprograms lipid metabolism to drive progression of ovarian cancer through ROS/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao M-Y, et al. Gypenoside L inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting the SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis and enhancing immune response. Bioorg Chem. 2024;150: 107539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, et al. Decreased HMGCS1 inhibits proliferation and inflammatory response of keratinocytes and ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis via the STAT3/IL-23 axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;133: 112033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, et al. MiR-612 regulates invadopodia of hepatocellular carcinoma by HADHA-mediated lipid reprogramming. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaves-Filho AB, Schulze A. Cholesterol atlas of tumor microenvironment provides route to improved CAR-T therapy. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1204–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu W, et al. GOT1 regulates CD8+ effector and memory T cell generation. Cell Rep. 2023;42: 111987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lv H, et al. NAD+ metabolism maintains inducible PD-L1 expression to drive tumor immune evasion. Cell Metab. 2021;33:110-127.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H, Qiao J, Shangguan J, Zhu J. Effects of glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase on reactive oxygen species in Ganoderma lucidum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023;107:1845–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weisshaar N, et al. The malate shuttle detoxifies ammonia in exhausted T cells by producing 2-ketoglutarate. Nat Immunol. 2023;24:1921–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar A, Delgoffe GM. Redox and detox: malate shuttle metabolism keeps exhausted T cells fit. Cell Metab. 2023;35:2101–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li K, et al. CSN6-SPOP-HMGCS1 axis promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via YAP1 activation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2306827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yi SA, Sepic S, Schulman BA, Ordureau A, An H. mTORC1-CTLH E3 ligase regulates the degradation of HMG-CoA synthase 1 through the Pro/N-degron pathway. Mol Cell. 2024;84:2166-2184.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee DJW, Hodzic Kuerec A, Maier AB. Targeting ageing with rapamycin and its derivatives in humans: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024;5:e152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Artoni F, Grützmacher N, Demetriades C. Unbiased evaluation of rapamycin’s specificity as an mTOR inhibitor. Aging Cell. 2023;22: e13888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu H, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes the transition of precursor to terminally exhausted T cells through HIF-1α-mediated glycolytic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunt EG, et al. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase obstructs CD8+ T cell lipid utilization in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2024;36:969-983.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jia D, et al. Microbial metabolite enhances immunotherapy efficacy by modulating T cell stemness in pan-cancer. Cell. 2024;187:1651-1665.e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J, et al. Hypoxia-triggered tumor specific glutamine inhibition for reversing cisplatin resistance of chemotherapy. Chem Eng J. 2024;479: 147692. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Slade D. PARP and PARG inhibitors in cancer treatment. Genes Dev. 2020;34:360–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greasing the wheels of the cancer machine: the role of lipid metabolism in cancer—PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31813823/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Shimano H, Sato R. SREBP-regulated lipid metabolism: convergent physiology—divergent pathophysiology. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:710–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, Zhang X, Wu R, Dong C-S. Unveiling purine metabolism dysregulation orchestrated immunosuppression in advanced pancreatic cancer and concentrating on the central role of NT5E. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1569088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng C, et al. A noncanonical role of SAT1 enables anchorage independence and peritoneal metastasis in ovarian cancer. Nat Commun. 2025;16:3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu R, et al. Melittin suppresses ovarian cancer growth by regulating SREBP1-mediated lipid metabolism. Phytomedicine. 2025;137: 156367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Construction of MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells and determination of cystine and glutamine sensitivity in OVCAR3 cells.Schematic diagram of the MSLN-targeted CAR structure.Workflow for the generation of CAR-T cells: PBMCs were isolated from healthy donors, followed by T cell enrichment, activation, lentiviral transduction with MSLN-CAR, and sorting of CAR-expressing cells by flow cytometry.Flow cytometric analysis of MSLN expression in T cells 3 days post-transduction confirms successful generation of MSLN-targeted CAR-T cells.CCK-8 assay assessing the dose-response of OVCAR3 cells to cystine after 48 h of treatment with increasing concentrations; IC50 = 2.277 mM.CCK-8 assay assessing the dose-response of OVCAR3 cells to glutamine after 48 h of treatment with increasing concentrations; IC50 = 36.5 mM. Figure S2. Dose-dependent effects of glutamine on CAR-T cell metabolism and phenotypes.Flow cytometry analysis of memoryand exhaustionmarkers in CAR-T cells cultured with 0 mM, or 10 mM glutamine for 2 days.Intracellular ROS levelsand apoptosisin CAR-T cells under 0/10 mM glutamine conditions.Glycolytic profile analysis showing: %PER from Glycolysis, Basal glycolysis, Glycolytic reserve, Compensatory glycolysis. in CAR-T cells cultured with 2 mMor 5 mM glutamine.Mitochondrial respiration parameters: Basal respiration, Maximal respiration, Spare respiratory capacity, ATP production, Proton leak.Metabolic balance indicators: ECAR/OCR ratio, %ATP from glycolysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Figure S3. Glutamine pretreatment maintains CAR-T cell purity and enhances cytokine secretion during repeated tumor stimulation.Purity of CAR-T and CAR-T+Gln cells population after multiple rounds of OVCAR3 stimulation. Representative flow cytometry plots showing CAR expressionin CAR-T cells after each round of OVCAR3 stimulation.Cytokine levels in co-culture supernatants measured by ELISA after four rounds of stimulation. IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α secretion by CAR-T cells co-cultured with ovarian cancer cell lines, CAOV3, SKOV3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by 2way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Figure S4. Glutamine pretreatment sustains memory-like phenotype and reduces exhaustion in circulating CAR-T cells.Representative flow cytometry plots showing: Memory phenotype: CD45RA+CCR7+ cells, Exhaustion markers: PD-1+TIM-3+ cells. In CAR-T+Gln-treated vs. control CAR-T cells at indicated timepoints. Figure S5. Quantitative analysis of metabolic gene expression in CAR-T cells following glutamine pretreatment.Bar graph showing the relative mRNA expression levels of 25 key metabolic genes related to glutamine, glucose, and lipid metabolism in control and glutamine-pretreated CAR-T cells, as determined by qPCR. Glutamine pretreatment significantly enhanced the expression of multiple metabolic genes, particularly those in the mTOR-SREBP2-HMGCS1 axis, including MTOR, SREBP2, and HMGCS1, suggesting activation of a metabolic reprogramming pathway. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.