Abstract

Objective:

To determine the impact of esophagectomy with 3-field lymphadenectomy on staging, disease-free survival, and 5-year survival in patients with carcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ).

Background:

Esophagectomy with 3-field lymphadenectomy is mainly performed in Japan. Data from Western experience with 3-field lymphadenectomy are scarce and dealing with relatively small numbers. As a result, its role in the surgical practice of cancer of the esophagus and GEJ remains controversial.

Methods:

Between 1991 and 1999, primary surgery with 3-field lymphadenectomy was performed in 192 patients, of whom a cohort of 174 R0 resections was used for further analysis.

Results:

Hospital mortality of the whole series was 1.2%. Overall morbidity was 58%. Pulmonary complications occurred in 32.8%, cardiac dysrhythmias in 10.9%, and persistent recurrent nerve problems in 2.6%. pTNM staging was as follows: stage 0, 0.6%; stage I, 9.2%; stage II, 27.6%; stage III, 28.7%; and stage IV, 33.9%. Overall 3- and 5-year survival was 51% and 41.9%, respectively. The 3- and 5-year disease-free survival was 51.4% and 46.3%, respectively. Locoregional lymph node recurrence was 5.2%; no patient developed an isolated cervical lymph node recurrence. Five-year survival for node-negative patients was 80.2% versus 24.5% for node-positive patients. Five-year survival by stage was 100% in stages 0 and I, 59.1% in stage II, 36.8% in stage III, and 13.3% in stage IV. Twenty-three percent of the patients with adenocarcinoma (25.8% distal third and 17.6% GEJ) and 25% of the patients with squamous cell carcinoma (26.2% middle third) had positive cervical nodes resulting in a change of pTNM staging specifically related to the unforeseen cervical lymph node involvement in 12%. Cervical lymph node involvement was unforeseen in 75.6% of patients with cervical nodes at pathologic examinations. Five-year survival for patients with positive cervical nodes was 27.7% for middle third squamous cell carcinoma. For distal third adenocarcinomas, 4-year survival was 35.7% and 5-year survival 11.9%. No GEJ adenocarcinoma with positive cervical nodes survived for 5 years.

Conclusions:

Esophagectomy with 3-field lymph node dissection can be performed with low mortality and acceptable morbidity. The prevalence of involved cervical nodes is high, regardless of the type and location of tumor resulting in a change of final staging specifically related to the cervical field in 12% of this series. Overall 5-year and disease-free survival after R0 resection of 41.9% and 46.3%, respectively, may indicate a real survival benefit. A 5-year survival of 27.2% in patients with positive cervical nodes in middle third carcinomas indicates that these nodes should be considered as regional (N1) rather than distant metastasis (M1b) in middle third carcinomas. These patients seem to benefit from a 3-field lymphadenectomy. The role of 3-field lymphadenectomy in distal third adenocarcinoma remains investigational.

Three-field lymphadenectomy was performed in 192 patients. R0 resection was obtained in 174 patients. Twenty-five percent (41 of 174) had cervical lymph node involvement resulting in a TNM change (stage IV) in 12%. Overall 5-year survival was 41.9%, being 80% for lymph node-negative patients (n = 52). Locoregional lymph node recurrence occurred in 5.2% of the patients (n = 9), distant metastasis in 28.5% (n = 49), and both locoregional lymph node recurrence and distant metastasis in 10% (n = 17). Patients with middle third squamous cell carcinoma had a 5-year survival of 27%. Cervical lymph node involvement in these patients should be classified as regional lymph node involvement (N1) and not as distant lymph node disease (M1b).

Cancer of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) is notorious for its advanced stage at the time of diagnosis with transmural invasion and early lymphatic spread in the majority of the patients. R0 resection is the aim of surgery with curative intent. However, much controversy persists over which type of surgery offers the optimal chances for cure.

Regarding the role of lymphadenectomy, as in any other solid organ cancer, there are opposing views. Some surgeons1 argue that the presence of lymph node involvement equals systemic disease and that survival remains unchanged despite removal of these lymph nodes. For others,2 the presence of lymph node involvement, even at a distance from the primary tumor, justifies an aggressive approach with radical esophagectomy combined with 3-field lymphadenectomy.

Extended 3-field lymphadenectomy became widely practiced in Japan as evidenced by a nationwide study reporting the results of 3-field lymphadenectomy performed at 35 institutions.3 From that report, it appeared that almost 1 in 3 patients had unforeseen lymph node metastases in the cervical lymph nodes. The authors also claimed an improved overall 5-year survival as compared with esophagectomy with 2-field dissection.

Surgeons in the West, in part influenced by a more minimalistic attitude, have been sceptical and reluctant to adopt the procedure because in North America and Europe most cancers occur in the distal esophagus and GEJ and because of fear for increased mortality and morbidity when adding a bilateral cervical lymphadenectomy. Data from Western experience with 3-field lymphadenectomy are therefore scarce and dealing with relatively small numbers.4 As a result, its role in the surgical practice of cancer of the esophagus and GEJ remains controversial.

The aim of this study is to determine the impact of primary esophagectomy with 3-field lymphadenectomy on staging, disease-free survival, and 5-year survival in patients with carcinoma of the esophagus and GEJ.

METHODS

Between 1991 and 1999, 812 patients were surgically treated for cancer of the hypopharynx, esophagus, and gastroesophageal junction in our department. A total of 703 patients underwent resection. Initial oncologic evaluation included upper GI endoscopy, upper GI barium swallow, computerized tomography of the chest and upper abdomen, upper GI endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and ultrasound of the cervical region. Since 1998, PET scan was systematically included in the clinical staging workup. When indicated, staging laparoscopy (eg, for adenocarcinoma of the GEJ) and/or VATS (eg, for suspicious lung nodule) was added to the workup. Bronchoscopy was systematically performed for tumors of the upper and middle third esophageal carcinoma.

All patients underwent further workup to assess the medical operability. This included evaluation of pulmonary and cardiac function. Vascular screening with special attention to carotid arteries or abdominal aortic aneurysm was performed on specific indication.

The exclusion of patients for 3-field lymphadenectomy was based on tumor of hypopharynx/cervical esophagus (n = 43); serious comorbidity, ASA score 3 (n = 105); high-grade dysplasia / Tis (n = 19); resection with peroperative finding of unforeseen M1ORG or R2 (n = 40); peroperative instability (n = 22); and age over 80 years (n = 18). Although age over 70 years was not a strict criterion in itself, patients older than 70 years were excluded when presenting with moderate risk factors, eg, previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery, moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Karnofsky index less then 60, etc (n = 98). In the initial 3 years, the study was considered as a pilot study, using very strict criteria, also excluding all patients over 65 years (n = 72). Finally, in a number of patients the exclusion was based on a combination of unspecified risk problems (n = 36) or capacity problems (n = 23).

All together, 227 patients (28%) underwent a 3-field lymphadenectomy, and 33 patients of this series underwent induction chemotherapy and were excluded as well.

The surgical technique of esophagectomy and abdominal and thoracic lymphadenectomy has been described elsewhere.5 Briefly, a left-sided thoracoabdominal approach was used for distal and GEJ tumors and a right-sided approach for upper and middle third tumors. A wide peritumoral resection was performed with extensive lymphadenectomy of the upper abdominal compartment (so-called DII resection) combined with a lymphadenectomy in the posterior mediastinum. Meticulous dissection of the lymph nodes was performed in the pulmonary window, along the left recurrent nerve and the right recurrent nerve at the brachiocephalic trunk. From the left-sided approach, this dissection starts from underneath the aortic arch upward and is completed from the neck downward. The thoracic duct was also part of the lymphadenectomy in the posterior mediastinum. Bilateral cervical lymphadenectomy was performed through a U-shaped neck incision and when judged appropriate by the responsible surgeon combined with a limited proximal sternal split to facilitate dissection along the recurrent nerves. Cervical lymphadenectomy included the paratracheal lymph nodes (deep internal nodes). The nodes lateral from the sternocleidomastoid muscle, ie, lateral to the internal jugular vein and supraclavicular nodes (deep external nodes) as described by Akiyama et al.2 Great care was taken not to damage the recurrent nerves.

All removed nodes were classified according to the anatomic subsites as described in the UICC TNM staging system.6 Routine pathologic examination was performed on paraffin-embedded, formaldehyde-fixed material. Tumor extension was staged on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections.

Data were collected prospectively and retrieved from our database. Complete follow-up was available until death or December 2002.

Follow-up

Patients were seen at regular interval of 3 months the first year and every 6 months until the 6th year, after which patients were followed on a yearly basis. Patients were seen either at our outpatient's clinic or by the referring physician. All data were collected prospectively in our database. Complete information was obtained until death or until December 2002.

Oncologic follow-up consisted in biochemistry, esophagoscopy, chest radiograph, and ultrasound of the abdomen and/or CT scan at 6-month intervals the first year and yearly thereafter, unless otherwise required on the basis of clinical history and clinical examination. More specific examinations (eg, bronchoscopy, bone scan) were performed according to the clinical indications.

Recurrence

Locoregional recurrence was defined as recurrence within the surgical field. In case of any doubt concerning this definition, the recurrence was classified as locoregional.

Statistical Analysis

Survival time was measured from time of the procedure until death or December 2002 (including hospital mortality). Survival statistics were obtained by the Kaplan–Meier method.7 All analyses were performed with the statistical package SPSS (version 10.0). A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 194 patients underwent primary resection. There were 166 men and 28 women with a median age of 59.3 years (range, 32–79 years).

Of this group 16 patients had an R1 resection (8%) and 2 patients had an R2 resection (1%) resulting in 176 R0 resections (91%). To obtain a homogeneous cohort, 2 more patients with a melanoma (and still surviving at 5 years) are also excluded, resulting in 174 R0 primary resections.

Mortality and Morbidity

Hospital mortality was 1% (2 of 194) of the entire surgical group and related to bleeding from a minitracheostomy with asystoly in 1 patient and septic shock in another patient.

Mean ICU stay was 1.8 days (range, 1–44 days); 81 patients (42%) had an uneventful course. Complications are listed in Table 1. As expected, pulmonary complications were by far the most frequent complications, totalling up to 32.8%, followed by cardiac dysrhythmia (10.9%). Anastomotic leakage occurred in 8 patients (4.2%). Persistent recurrent nerve injury was observed in 5 patients (2.6%).

TABLE 1. Complications

Mean postoperative hospital stay was 19.9 days (median, 15 days; range, 5–97 days)

Pathologic Findings

A total of 174 patients had an R0 resection (90.7%), 16 patients had an R1 resection (8.3%), and another 2 patients an R2 resection (1%).

The median number of resected lymph nodes was 57 for a total of 10,316 (mean, 59.2) examined lymph nodes; 61 patients had nodal disease confined to only one field, 37 had 2 field involvement, and 24 had lymph node metastasis in all 3 fields. A total of 122 patients (70%) had pathologically confirmed nodal metastasis with an average of 5.8 positive nodes per patient (range, 1–41).

Table 2 shows the repartition between histologic tumor type and the correlation with their localization, indicating, as expected, a predominance of adenocarcinomas located in the distal esophagus and GEJ.

TABLE 2. Prevalence of Cervical Node Involvement by Tumor Site and Histologic Type

TNM staging and final stage grouping6 are depicted in Table 3. Two thirds of the patients had positive nodes resulting in an almost identical stage grouping, 62.6% being in stage III and IV.

TABLE 3. TNM Staging

As shown in Table 4, prevalence of nodal disease increased according to T stage. Interestingly, in T1b tumors, as much as 34.8% of the patients had lymph node involvement.

TABLE 4. Prevalence of Nodal Disease in Relation to T-Stage

Impact of the Third Field

There was a prevalence of cervical lymph nodes involvement in 23.6% and, according to T stage, a gradual increase in cervical lymph node involvement (Table 4) was noticed.

Surprisingly, 5 (21.7%) of the 23 patients with T1b tumors showed positive cervical nodes. This represents 62.5% of all positive nodes in T1b patients. Table 2 depicts the prevalence of cervical lymph node involvement according to tumor site and histologic type. Middle third squamous cell carcinomas had 26.2% positive cervical nodes, distal third adenocarcinoma 25.8%, and even in GEJ tumors 17.6% of the patients had cervical node involvement.

As shown in Table 5 the dissection of the “third” field resulted in a true change of TNM staging in 26 patients (15%). The cervical lymph node involvement in this group was suspected, ie, foreseen in 4 patients but unforeseen in 22 patients. In other words, for the entire series of 174 patients with R0 resection, bilateral cervical lymph node dissection resulted in a restaging into stage IV disease in 12%.

TABLE 5. Change in TNM Stage

The mean number of nodes involved in this group was 5.38. Five patients had positive nodes only confined to the cervical region and another 5 patients had a combination of positive cervical and abdominal lymph node involvement without any positive lymph nodes in the chest. So 10 patients (10 of 122, 8.2%) had skip metastasis in the cervical region.

Survival

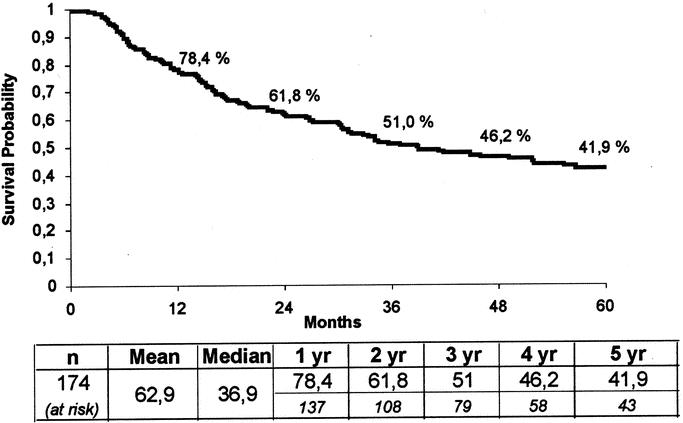

The median follow-up was 59 months. The overall disease specific 5-year survival of the entire group of 192 patients, independent of R-status, was 39.5%. For the 174 R0 patients, 5-year survival was 41.9%; the 1- and 3-year survival was 78.4% and 51%, respectively (Fig. 1). These figures include 6 patients who developed a metachronous carcinoma (3 ENT, 1 lung, 1 pancreatic, 1 bladder cancer) with 2 early deaths resulting from the second primary tumor. There was no significant difference between adeno- and squamous cell carcinoma, ie, 35.0% and 44.7%, respectively (P = 0.53).

FIGURE 1. Overall survival in 174 R0 resections for carcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ).

As expected, there was a highly significant difference in 5-year survival between node-negative (80.2%) and lymph node-positive patients (24.5%) (Fig. 2). Patients with more than 5 positive nodes (n = 42) had a 5-year survival of 19.3%.

FIGURE 2. Survival according to lymph node involvement in 174 R0 resections.

Survival by stage is shown in Figure 3. Stage III patients had a 36.8% 5-year survival and stage IV still reached a 13.3% 5-year survival.

FIGURE 3. Survival according to TNM staging in 174 R0 resections.

When comparing survival of lymph node-positive patients according to their cervical lymph node status, 5-year survival was 12.8% in the cervical node-positive group versus 31.1% (P = 0.03) in the cervical node-negative group (Fig. 4). When comparing the survival in cervical lymph node positive patients according to histologic type, squamous cell carcinomas showed a better 5-year survival (15.8%) compared with 7.3% for adenocarcinomas. This difference was not significant (P = 0.81) (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 4. Survival according to cervical lymph node status in 122 patients with any lymph node involvement.

FIGURE 5. Survival in 41 patients with cervical lymph node involvement according to histologic type.

Further subgroup analysis showed that middle third squamous cell carcinomas had a 5-year survival of 27.2% (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6. Survival in patients with adenocarcinoma of the distal third and squamous cell carcinoma of the middle third of the esophagus presenting with cervical lymph node involvement.

Distal third adenocarcinomas had a 5-year survival of 11.9% but a 4-year survival of 35.7% (Fig. 6). No patients with GEJ adenocarcinoma and positive cervical nodes survived for 5 years.

Recurrence

A total of 174 patients had a complete resection, of whom 2 had hospital mortality. One patient who developed a second primary metachronous lung cancer died 30 months after esophagectomy of disseminated metastasis related to his lung cancer. Therefore, 171 patients were evaluable for recurrence.

Ninety patients (52.6%) remain disease free. Forty-nine patients developed distant metastasis (28.6%), 9 (5.2%) had locoregional lymph node metastasis, and 17 (9.9%) had both locoregional lymph node and distant metastasis. Of the latter group, 3 patients had recurrence in cervical lymph nodes combined with mediastinal locoregional recurrence, 2 of them having simultaneous multiple organ metastasis. No patients had a locoregional recurrence only confirmed to the neck. Finally, 6 patients (3.5%) had an anastomotic recurrence without evidence of any other recurrence, in particular, in the cervical nodes in 3 and combined with distant metastasis in the 3 remaining patients.

Three- and 5-year recurrence free survival was 55.4%and 46%, respectively (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7. Overall disease-free survival in 172 R0 resections.

DISCUSSION

Extensive lymphadenectomy in particular 3-field lymphadenectomy has become widely practiced since the 1980s, especially in Japan. Numerous reports have indicated improved 5-year survival and a reduction of the locoregional recurrence rate as compared with the more classic 2-field lymphadenectomies. Overall 5-year survival rates of up to 68% have been reported by Nishimaki et al.8 Akiyama et al2 reported a 5-year survival of 54% after 3-field lymphadenectomy in node-negative patients as compared with 34% after 2-field lymphadenectomy (P = 0.004). In this study patients with positive node disease also had an overall superior 5-year survival of 43% as compared with 28% after 2-field dissection (P = 0.0008).

However, a number of studies indicated that extended 3-field dissection was associated with a marked increase of recurrent nerve injuries varying between 15% and even as much as 70%.9,10 As a result, surgeons in the Western world remained reluctant to apply such extensive lymph node dissection, especially in a population in whom adenocarcinoma rather than squamous cell carcinoma has become the predominant tumor type. Moreover, in the Western world, patients with tumors located above the level of the tracheal bifurcation are usually submitted to multimodality therapy, ie, induction chemo and/or radiotherapy followed by surgery. Therefore, data on 3-field lymphadenectomy coming from Western centers are scarce, and indeed only one series has been recently published by Altorki et al.4 In this study, a series of 80 patients have been analyzed.

The present study deals with 192 patients, of whom 174 had a R0 resection, and represents actually the largest series from a Western center. This study differs from the Altorki et al4 series in 2 aspects. Firstly, since adenocarcinoma is the predominant type of tumor, it was thought that the impact of 3-field lymphadenectomy on adenocarcinoma of the GEJ also had to be evaluated. Second, in the Altorki et al study,4 the definition of the third field included not only the cervical lymph nodes but also the upper thoracic paratracheal lymphatic chain under the denomination of cervicothoracic nodes. Although these lymphatic chains are indeed in continuity, we preferred to strictly follow the anatomic subsites as described in the UICC TNM classification6 and thus also strictly follow the definitions of regional (N1) and metastatic (M1a or M1b) lymph node metastasis. These differences in definition may explain why the study of Altorki et al4 showed a much higher prevalence of involved nodes on the third field 36% versus 23.5% in the present series. Also, as a result of the strict application of the UICC TNM definition, the prevalence of M1b (20.7%) disease in the actual series was much higher as compared with the Altorki et al4 series (1.2%).

These differences in inclusion of histologic type of tumors and in the use of definition may therefore explain some of the seemingly better outcomes, especially for patients with upper half squamous cell carcinoma in the Altorki study4.

Our study, as other studies, confirmed the feasibility of 3-field lymphadenectomy without increase of mortality or morbidity as compared with more conventional resection. Also, persistent recurrent nerve injuries stayed at a very low incidence of 2.6%. This low incidence can be biased, as laryngoscopy in the postoperative period was not performed on a systematic basis on all patients, but only if patients complained of hoarseness.

Impact on Staging

The most important finding was the high incidence of cervical lymph node involvement in 23.5% of the patients mostly unforeseen (75.6%), resulting in a real change in TNM staging in 12% of the patients that indeed were upstaged into stage IV disease.

Most importantly also was the cervical lymph node involvement in superficial T1b tumors, as much as 21.7%. Cervical lymph node involvement seemed to be independent from tumor type as well with 25.8% of distal third adenocarcinoma and 26.2% of middle third squamous cell carcinomas presenting with positive nodes in the neck.

This impact on staging has a number of important implications. It confirms that the actual clinical staging is still inadequate.

Our results also indicate that stage migration is still a reality that cannot be overcome with the actual clinical staging methodology since we found overall 8.2% skip metastasis in the present series.

The high prevalence of unforeseen cervical lymph node involvement and the resulting potential stage migration clearly has therapeutic consequences. First, the inability to assess adequately lymph node involvement in T1b tumors still makes patient selection for nonsurgical treatment modalities such as endoscopic mucosal resection or photodynamic therapy very unreliable. In this group of patients, surgery therefore remains the treatment of choice.

Second, when using radiotherapy in an induction therapy mode, extension of the irradiated fields to the cervical region should be seriously considered in tumors of the tubular esophagus, irrespective of histologic tumor type and localization.

Third and most importantly, as long as accurate clinical staging can only be obtained through extended lymphadenectomy patient selection for multimodality treatment, ie, induction therapy and the assessment of outcome remain very unreliable.

Finally and equally important, 3-field lymphadenectomy, by detecting otherwise unknown positive nodes in the third (cervical) field, refines the true N0 population, allowing to assess the real prognosis of this group with a 5-year survival of as much as 80% in our series and an even more impressive 88% in the series of Altorki et al.4

These data indicate that ultimately there is a need for replacement of the actual relative crude TNM clinical assessment by more refined and especially more sensitive and or accurate techniques such as molecular staging markers or tumor-specific panels. But in the meantime, physicians involved in the treatment of patients with cancer of the esophagus and GEJ should pay attention to the extent of lymph node involvement as a prognostic marker and its evident therapeutic implications.

Another important consequence of the high prevalence of unforeseen cervical lymph nodes is that a significant number of patients may be incompletely resected following a more standard approach. This impact of such incomplete resection is not clearly established, but there is general agreement that R1 or R2 resections are associated with a poor outcome with little chances of survival beyond 2 or 3 years.11,12

These data raise the question whether extended lymphadenectomy has an impact on locoregional recurrence.

Autopsy findings in patients after curative esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma indicate a high incidence of recurrent disease in lymph nodes. According to Katayama et al,13 there is an incidence of 11.6% in the lymph nodes of the neck, with a significantly lower overall incidence of locoregional recurrent disease after 2- or 3-field dissection as compared with less extended surgery.

From a clinical point of view, most of the recurrences are known to occur within 1 year after operation. In the present series, median recurrence-free survival was not reached even 3 years postoperatively (55.4%); the 1- and 2-year survival was 75.4% and 62.4%, respectively. Similar results were obtained in the series of Altorki et al.4

Such higher incidence of local tumor control and disease-free survival seems to be correlated with a higher percentage of R0 resection, perhaps through a better control of micrometastasis. Immunohistochemical staining with monoclonal antibodies may detect micrometastasis in up to 40% of patients staged as N0 disease with standard histologic techniques.14 The prognostic implications will have to be demonstrated. In this respect, the concept of 3-field lymphadenectomy seems reasonable as it further increases the safety margin in the area of lymphatic drainage.

There are no randomized trials as to the effect of 3-field lymphadenectomy in local tumor control and disease-free survival, but there is evidence from mainly Japanese literature suggesting a better tumor control and disease-free survival in favor of 3-field lymphadenectomy versus 2-field lymphadenectomy. In the study of Akiyama et al,2 lymph node-negative patients had a 3-year survival of 88% after 3-field lymphadenectomy versus 71% after 2-field lymphadenectomy. For upper third carcinoma an overall 3-year survival was 63% after 3-field versus 33.8% after 2-field lymphadenectomy. Our data, with a 3-year survival of 80.2% for lymph node-negative and a 37.7% 3-year survival for lymph node-positive patients, are in the same range as the data from the Japanese literature. The locoregional recurrence rate of 5.2% (9 of 174 patients) in our series also seems to compare favorably to incidence of locoregional recurrence after less extensive surgery.

Critics of extensive surgery argue that the incidence of isolated recurrence in the cervical region in absence of neck dissection is low and indeed irrelevant. Dresner et al15 reported a cervical nodal recurrence of only 6%. Hulscher et al16 found a cervical recurrence of 8.5%. Both authors questioned the addition of the third field cervical dissection. Also, in the study by Clark et al,17 the cervical recurrence rate was in the same range (9%).

These figures seem to be low indeed. However, the true relevance of cervical lymph node recurrence is reflected by the portion of cervical recurrence versus the totality of nodal recurrences. In both studies of Dresner et al15 and Hulscher et al,16 cervical recurrence was 21% of all nodal recurrence. In the study of Clark et al,17 the figure was 20%. In the present study, no patient had isolated cervical lymph node recurrence and only 1 patient had cervical lymph node recurrence combined with mediastinal locoregional metastasis.

This may in itself justify an effort of 3-field lymphadenectomy even in distal third tumors wherein patients with cervical node metastasis (M1b disease) had a 4-year survival of as much as 33%.

The final question of course relates to the impact of 3-field lymphadenectomy on 5-year survival.

As already mentioned, Japanese authors have reported overall 5-year survival figures that range between 40% and 66%. These figures are consistently higher than the figures obtained with 2-field lymphadenectomy ranging between 26% and 48%.3,9,10,18

In the Western world, the overall survival figures in surgically resected patients are generally in the range of 20% to 30%.

The figures of 42% as described in this report and the 51% in the series of Altorki represent essentially a doubling of results obtained after less extensive surgery.1 The somewhat lower overall 5-year survival in the present series as compared with the figure obtained by Altorki et al3 is most likely explained by the fact that in our series adenocarcinomas of the GEJ were included, for which adding the third field is probably of little or no value since no 5-year survival was obtained in patients with carcinoma of the GEJ and presenting with positive cervical nodes.

The answer of the real impact of 3-field lymphadenectomy on cure rate should come from randomized trials. However, given the complexity of the issue, the difficulty in recruiting sufficient patients and the technical difficulty of the surgery, there are few data available.

A randomized trial was performed by Nishihira et al19 comparing 2- and 3-field lymphadenectomy showing an advantage in favor of 3-field lymphadenectomy with overall 5-year survival of 66.2% and 48%, respectively. This difference was however not significant. On the other hand, the study by Kato et al18 evaluated 2 matched groups and did find a statistically significant difference with an overall 5-year survival of 33.7% versus 48.7% for 2- and 3-field lymphadenectomy, respectively.

The message from these conflicting results is that most likely only a subset of patients will really benefit from it. This could well be related to the number of lymph nodes involved as shown by Nishimaki et al.20 In their analysis, no patients with ≥ 5 involved lymph nodes survived for more than 5 years. This was not, however, substantiated by our findings. Of the 41 patients with positive lymph node in the cervical field, 23 had more than 5 positive nodes with a 5-year survival of 18.3%.

Moreover, the criterion of number of involved nodes is impractical as the final data on the number of involved nodes are only obtained at pathologic examination, ie, after surgery.

Another possibility in relation to the subset of patients benefiting from 3-field lymphadenectomy could be the localization of the tumor. In the present study, patients with middle third carcinoma presenting with positive nodes in the neck had a 5-year survival of 27.2%. Such patients are classified in the UICC-TNM staging system6 as M1b disease. Obviously, our survival figures as well as those obtained by the Altorki series and many other Japanese studies indicate that involvement of cervical nodes in middle third carcinoma should be classified as regional (N1) disease and not as distant node involvement (M1b). In other words, such patients should not be denied any chance for therapeutic strategy with curative options because of cervical lymph node involvement.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that esophagectomy with 3-field lymph node dissection can be performed with low mortality and acceptable morbidity. The prevalence of involved cervical nodes is high, regardless the histologic type and location of tumor resulting in a change of final staging specifically related to the cervical field in 15% of this series. The low incidence of locoregional lymph node recurrences with or without distant metastasis (15%) and the overall 5-year survival and disease-free survival after R0 resection of more than 41% may indicate a real survival benefit. A 5-year survival of 27.2% in patients with positive cervical nodes in middle third carcinomas indicates that these nodes should be considered as regional (N1) rather than distant metastasis (M1b) in middle third carcinomas. These patients seem to benefit from a 3-field lymphadenectomy. The role of 3-field lymphadenectomy in distal third adenocarcinoma remains investigational requiring validation by other experienced esophageal centers.

Discussions

Dr. Izbicki: I enjoyed the paper very much, and I especially would like to thank Dr. Lerut for the opportunity to give me the paper beforehand for review. I think you and your group are to be congratulated on the excellent results in terms of mortality and morbidity for this formidable operation.

However, there might be some reservations about the data analysis of this study, especially about the interpretation, at least with the aspect to provide some guidance with regard to the extent of lymphadenectomy in patients with esophageal carcinoma. The main message of the paper is twofold. First, 25% of patients with esophageal carcinoma have cervical lymph node metastasis, which are not evident before surgery. Second, patients without cervical lymph node metastasis might benefit from this more aggressive surgery.

There are, however, several points of criticism. First, in my opinion, tumors of the gastroesophageal junction should be excluded of analysis because of the different way of metastatic spread.

Secondly, you raised the point of skip nodal metastasis, and I would be very much interested to know what the frequency of patients with cervical lymph node metastasis was without having mediastinal lymph node metastasis.

The third point is a technical point, namely, the application of sternotomy. In my experience, the removal of lymph nodes from the upper mediastinum without sternotomy is not as complete as with sternotomy; and as I have understood your paper, in some cases sternotomy was performed whereas in others you did not. I would be interested to know how you base your decision to do sternotomy.

The last point is the question of stage migration, and I think that this is the most important point to discuss. The basic message from your paper is that lymph node-positive patients have a 5-year survival of 25%. These figures compare relatively favorably to series of other esophageal centers and institutions that use just the 2-field lymphadenectomy; for example, in our institution, the 5-year survival rate is just over 20% in approximately 240 patients. When you break your figures down in cervical lymph node-negative patients and cervical lymph node-positive patients, then you have a 5-year survival of 36.8% and 13%, respectively. I wonder if you take the collectives of other institutions which reach roughly an overall 5-year survival of 25% with 2-field lymphadenectomy then whether your good results in patients with just mediastinal node involvement is not just a reflection of stage migration and better and refined staging.

Once again, thank you for the opportunity to review this excellent clinical study.

Dr. Lerut: Thank you Dr. Izbicki, for your comments and remarks. About your remark that gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) tumors metastasize in a different way, I am not so sure that they differ indeed. The adenocarcinomas that we see are about equally distributed among the distal third and the GEJ, and this is not always a clearcut zone. We decided to include the GEJ tumors intentionally just to study effectively the pattern of dissemination. So finding 16% unforeseen positive lymph nodes in the neck for GE junction tumors reflects a pattern of lymph node dissemination not only in aboral way but also in the oral direction, similar to distal third adenocarcinomas. Moreover, there are some studies on cytokeratines, and our group just published one such study, which indicates that the behavior of GE junction tumors is indeed closer to the behavior of a true esophageal adenocarcinoma rather than that of a gastric carcinoma. The results from the present study show, however, that at 5 years there is no benefit from a 3-field lymphadenectomy, but at least there is an important message concerning the data of lymph node involvement and their prognostic significance.

I have not the exact figures on the number of skip metastasis, ie, lymph node involvement in the neck without lymph node involvement in the chest. I think there were 5 patients, and what was very surprising was that these were mostly patients with T1 tumors. As to the technical aspects of the sternotomy, this is a short proximal split sternotomy. Initially, this was mainly done because of our concerns not to damage the recurrent nerve, especially on the right side where there is a higher percentage of anatomic variations. Of course, it also can be used to have a better guarantee of complete lymphadenectomy, but I think with the increasing experience one can obtain this without the need for a split sternotomy.

Clearly, stage migration is an issue, but at least it allowed us to come up with a better insight on the true survival of N0 patients, which is 80% in our study and was 88% in the study of Altorki.

Your comments about a 36% 5-year survival in lymph node-positive patients without cervical lymph node involvement are well taken. It is difficult to say in how much this is reflecting the effect of refined staging. But 36% is a very high figure anyway.

Comparing the 25% 5-year survival for all node-positive patients with similar results from other groups after 2-field lymphadenectomy is very difficult. There can be differences in the stages but also in the tumor load. In this series, there was a 5.8 mean of positive lymph nodes, but this can differ from study to study. These are things that are to be taken into consideration. Recently, we published a study on extracapsular lymph node involvement versus intracapsular lymph node involvement, and we found extracapsular lymph node involvement to be an independent prognostic factor as well.

The same goes for the other end of the scale on the effect of micrometastatic involvement as shown by your group. So, comparing data from one study to those from another study remains very difficult. But again, if one can come up with an overall 5-year survival of 25% in a group of patients with positive lymph nodes and a 13% 5-year survival in the subgroup who had positive lymph nodes in the neck and among them 27% 5-year survival for middle third squamous cell carcinoma, then the message is very clear, especially for gastroenterologists and oncologists: these patients should not be denied any treatment aiming at cure.

Dr. Wong: Thank you, Chairman, for instructing me to comment on the spot. Maybe it is my jetlag but the slides went pretty fast and I could not absorb all of them, and I did not have the chance to read the manuscript beforehand. My comment is that when offering a treatment with 75% of the patients not needing it, the case has to be carefully justified. The proposal is not only an operation but may include radiotherapy to the neck as well. I concur with what Dr. Izbicki said, and that is that improved survival has to be pretty definite in order to justify that type of aggressive treatment. You mentioned that most of the patients with positive lymph nodes were “unforeseen” before operation. I presume that meant the lymph nodes were not clinically palpable. So I wondered whether you have investigated these patients with ultrasound, FNA, and other tests. Furthermore, in the years since 1998, you had included PET scans. What are the results of these? Did they differentiate between those who were node positive and negative.

My last comment is what the Chairman said at the start of this session, and that is: would it have been possible, and better, to do a randomized controlled trial on this study? I know that is over a 9-year period and the numbers are not very big, but that would have helped to solve the problem of how many fields of dissection is the appropriate approaches.

Dr. Lerut: Thank you, Dr. Wong. I think you didn't need to read my manuscript and even coming in with the jetlag you are sufficiently familiar with the work my group is doing and in fact your questions are the ones that I could expect and your comments are well taken. I think it is unfair to say that I was presenting data on 75% of patients who don't need surgery at all because in fact, then, it is the same group of 75% who do not need induction therapy or definitive radiochemotherapy because the main problem is that we simply do not know beforehand which patients are going to be in that 75% and which patients will be the lucky group of 25% or as in this series the 42%. This is the problem of the clinical staging; and in that respect, most positive cervical nodes where unforeseen. Indeed, all the patients had an ultrasound of the neck and when possible fine needle aspiration was performed. They all had echo endoscopy and from 1998 on PET scan. We are now finishing a study from 1998 on until now, and I can tell you that PET scan to a certain extent is identifying positive distant lymph nodes, but it is disappointing to see there is still a substantial number of patients who have unforeseen positive lymph nodes also in the neck.

As to your last question on randomized trials, first of all, if you consider 174 patients as a small series, I would argue that this is not true. In fact, this series is the largest series in the Western world, Altorki's series was on 80 patients, and even our Japanese colleagues are no longer able to come up with very large numbers. I think in fact that we never ever will be able to come up with a randomized trial on 3-field lymphadenectomy. Indeed, we do not get these patients referred anymore because once a lymph node is detected, often such patients are classified as being in a palliative stage and treated accordingly. Furthermore, there is an attitude, especially in the United States, where also early T1 tumors are getting now induction therapy. So again, in my mind, it will be extremely difficult, most likely impossible, to set up a randomized trial on this topic. Of course, I do agree with you that this will be the only way to come out of it, but I think it is too late now.

Footnotes

Other members of the Leuven Collaborative Working Group for Esophageal Carcinoma are as follows: E. Van Cutsem (Digestive Oncology); M. Hiele, I. Demedts (Endoscopy); S. Stroobants (Nuclear Medicine); W. De Wever, S. Dymarkowski (Radiology); and K. Haustermans (Radiotherapy).

Reprints: Prof. Dr. T. Lerut, University Hospitals Leuven, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Herestraat 49, 3000 Leuven, Belgium. E-mail: Toni.Lerut@uz.kuleuven.ac.be.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Stirling MC. Transhiatal esophagectomy for benign and malignant disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:265–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akiyama H, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, et al. Radical lymph node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg. 1994;220:364–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isono K, Sato H, Nakayama K. Results of a nationwide study on the three-field lymph node dissection of esophageal cancer. Oncology. 1991;48:411–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altorki N, Kent M, Ferrara C, et al. Three-field lymph node dissection for squamous cell and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Surg. 2002;236:177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerut T, De Leyn P, Coosemans W, et al. Surgical strategies in esophageal carcinoma with emphasis on radical lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;216:583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobin L, Wittekind C. UICC TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, 6th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Non parametric estimation from incomplete observations. JAMA. 1958;53:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishimaki T, Suzuki T, Kanda T, et al. Extended radical esophagectomy for superficially invasive carcinoma of the esophagus. Surgery. 1999;125:142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isono K, Ochiai T, Koide Y. Dis. Indications for extended three-field lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 1994;7:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita H, Kakegawa T, Yamana H, et al. Mortality and morbidity rates, postoperative course, quality of life, and prognosis after extended radical lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer: comparison of three-field lymphadenectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerut T, De Leyn P, Coosemans W, et al. Advanced esophageal carcinoma. World J Surg. 1994;18:279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis H, Heatley G, Krasna M, et al. Esophagogastrectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus and cardia: a comparison of findings and results after standard resection in three consecutive eight-year intervals with improved staging criteria. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:836–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katayama A, Mafune K, Tanaka Y, et al. Autopsy findings in patients after curative esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:866–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Natsugoe S, Mueller J, Stein HJ, et al. Micrometastasis and tumor cell microinvolvement of lymph nodes from esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: frequency, associated tumor characteristics, and impact on prognosis. Cancer. 1981;83:858–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dresner S, Wayman J, Shenfine J, et al. Pattern of recurrence following subtotal oesophagectomy with two field lymphadenectomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:362–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hulscher J, van Sandick J, Tijssen J, et al. The recurrence pattern of esophageal carcinoma after transhiatal resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark G, Peters J, Ireland A, et al. Nodal metastasis and sites of recurrence after en bloc esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato H, Watanabe H, Tachimori Y, et al. Evaluation of neck lymph node dissection for thoracic esophageal carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:931–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishihira T, Hirayama K, Mori S. A prospective randomized trial of extended cervical and superior mediastinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Am J Surg. 1998;175:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishimaki T, Suzuki T, Suzuki S, et al. Outcomes of extended radical esophagectomy for thoracic esophageal cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]