Abstract

Objective

To present preoperative and early postoperative data for 504 patients who underwent duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR) for severe chronic pancreatitis (CP).

Background

The pancreatic head is considered to be the pacemaker of the disease in alcohol-induced CP. Indications for surgery in CP are intractable pain and local complications. DPPHR offers the advantage of treating the complications related to the inflammatory process in the head, relieving the pain syndrome, and preserving the bilioduodenal anatomy, and it may have the potential to change the natural course of chronic pancreatitis.

Methods

Between November 1972 and December 1998, 504 patients with chronic pancreatitis and an inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head were treated surgically after medical pain treatment for a median of 3.6 years. The procedure resulted in a hospital mortality rate of 0.8%. A continuous follow-up investigation lasting up to 26 years was conducted, during which the patients were reevaluated four times (1983, 1987, 1994, 1996). Between November 1982 and October 1996, 388 patients treated surgically were reinvestigated to evaluate the late outcome; the follow-up rate was 94% (25 patients were lost to follow-up). The reinvestigation evaluation included glucose tolerance test, exocrine pancreatic function test, pain status, physical status, professional and social rehabilitation, and quality of life.

Results

After an observation period of up to 14 years, 78.8% of the patients were completely pain-free and 12.5% had (yearly) pain. 91.3% were considered as pain-free; 8.7% had continuing abdominal pain; 12% had abdominal complaints. During the 14 years of follow-up, only 9% were admitted to the hospital for acute episodes of chronic pancreatitis. Endocrine function was improved in 11%; in 21%, diabetes developed de novo. The rate of hospital admission for acute episodes decreased from 69% before surgery to 9% after surgery. In the clinical management period of 9 years (median), the frequency of hospital admission dropped from 5.4 per patient before surgery to 2.7 after surgery. Fourteen years after surgery, 69% of the patients were professionally rehabilitated; in 72%, the quality of life index (Karnofsky criteria) was 90 to 100 and in 18%, it was <80.

Conclusion

In patients with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis in whom an inflammatory mass has developed in the pancreatic head, DPPHR results in a change in the natural course of the disease in terms of pain status, frequency of acute episodes, need for further hospital admission, late death, and quality of life.

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is characterized by the presence of chronic inflammatory lesions, the destruction of exocrine and endocrine parenchyma, and fibrosis. 1 The molecular and pathobiochemical mechanisms resulting in the focal inflammation and fibrosis of the pancreas are largely unknown. A common feature histologically is infiltration by leukocytes, 2 pancreatic main duct and side branch duct alterations, focal necrosis, 3 and extended fibrosis. 4 Leukocytes release cytokines and growth factors (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, TNFα, EGFβ), which are thought to induce the proliferation of mesenchymal cells. 5–7 Overexpression of EGF and TGFα+β and acid and basic FGF is observed. 8–11 Activated cytotoxic cells and their mediators are considered to play a key role in the chronic inflammatory process. 12–14

Upper abdominal pain, the leading clinical symptom, is related to an increase in duct and tissue pressure of the pancreas. 15 Pathomorphologic changes in the sensory nerves, an increase in nerve diameter and perineural infiltration of inflammatory cells, 16 and an increase in the neurotransmitter substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide are considered to be causally related to the pain syndrome in CP. 17,18 A significant correlation was found between nerve growth factor (NGF) mRNA expression and the amount of pancreatic fibrosis, as well as the degree of acinar cell destruction; the TrkA transmembranous thyrosinkinase receptor, binding NGF, and the intensity of pain are correlated. 19 The increased activity of the NGF/TrkA signal cascade suggests a role in the pathway involved in nerve proliferation and the pain syndrome in CP. 19

On long-term follow-up, the natural course of CP reveals persistence of pain in 85% and 55% of the patients 5 to 10 years after diagnosis. 20 The progression of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency, frequently observed in CP, has a limited influence on the pain syndrome. 20 Local complications such as pseudocystic lesion, common bile duct stenosis, inflammatory mass in the head, and compression of the anatomic structures surrounding the pancreatic head are observed frequently. Long-term follow-up reveals that patients with CP have a 5-year survival rate of 67% and a 10-year survival rate of 43%. 21,22 The death rate related to CP was 12% to 20%. 22–24 Epidemiologic studies of patients with CP demonstrated a coincidence with pancreatic cancer in 1.8% to 4% and with extrapancreatic cancers in 3.9% to 13%. 25–28

In Western countries, alcohol is the most frequent etiologic factor. Patients with alcoholic CP frequently have an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas and severe local complications. The subgroup of patients with CP and an inflammatory mass in the head consists predominantly of men younger than 40; they usually have severe abdominal pain that is finally resistant to analgesic treatment, and local complications are frequent. These patients are candidates for surgical treatment. 28

In this article, we present preoperative and early postoperative data for 504 patients who underwent surgery for severe CP. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR) was used because it eradicates the pain syndrome in most patients and eliminates the local complications that contribute to the complications of CP.

PATIENTS

Five hundred four patients (80% men) underwent DPPHR for painful, complicated CP between November 1972 and December 1998. The etiology was alcohol in 81% and undetermined in 19%; in 8% there was an association with biliary stone disease. The presurgical diagnostic workup included endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography (MRCP), contrast-enhanced helical CT scanning, intestinal angiography (until 1988), gastroduodenoscopy, duodenography, and endoscopic ultrasound. An oral glucose tolerance test was obtained in all patients except those with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A pancreolauryl test was conducted in most patients to evaluate the exocrine pancreatic function. 29 The mean age at surgery was 44.4 years, and the median duration of pain was 3.6 years.

Based on clinical symptoms and CT data, celiac truncal and mesenteric artery angiography was carried out in patients with suspected vascular stenosis or occlusion of the portal and splenic vein; in the last 10 years, endoscopic ultrasound replaced angiography.

Preoperative complications and the indications for surgery are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Four hundred sixty patients had abdominal pain, most with local complications. Forty-six percent of the patients with pain had daily pain. Forty-four patients (9%) did not have pain but did have severe local complications (e.g., common bile duct stenosis with cholestasis or jaundice, severe stenosis of the duodenum, and portal vein compression causing signs of portal hypertension and ascites). The results of the oral glucose tolerance test were within a normal range in 246 patients; reduced glucose tolerance was found in 134 patients; 124 patients had insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. In 284 of 329 patients, the exocrine function was reduced based on the pancreolauryl test.

Table 1. PREOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS (504 PATIENTS)

* 11/1972–4/1982, Dept. of Surgery, FU Berlin; 5/1982–12/1998, Dept of General Surgery, University of Ulm.

Table 2. INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY (504 PATIENTS)

Angio, angiography; AP, alkaline phosphatase; CBD, common bile duct; CT, computed tomography; ECRP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; GD, gastroduodenoscopy; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography; PMD, pancreatic main duct.

On contrast-enhanced helical CT, 376 patients (75%) showed an enlargement of the pancreatic head. Pseudocystic lesions contributed to the enlargement of the pancreatic head in 46 patients. Seven patients had additional pseudocystic cavities in the body and tail of the pancreas.

Follow-Up Investigation

A continuous follow-up investigation lasting up to 26 years (301 months) was conducted to evaluate the early and late outcome of the patients who underwent DPPHR for painful complicated CP. The patients were examined four times, in 1983, 1987, 1994, and 1996. Three of these examinations were carried out as in-hospital investigations (1983, 1987 and 1996). The results of these late follow-up investigations were published in 1985, 30 1989, 3 and 1997. 31 The results of the last follow-up investigation, including patients who underwent surgery between May 1982 and October 1996, are presented in this paper.

Three hundred ten (80%) of the 388 patients were men and 78 (20%) were women. The mean age at surgery was 50.4 years (range, 21 to 82 years). DPPHR was performed in 388 patients with advanced CP. Four patients died in the hospital (hospital mortality rate 1%). The late death rate was 13% (49 patients); reoperation resulting from intractable abdominal pain or an undefined tumor of the duodenum was performed in 7 patients (2%). Twenty-five patients were lost to follow-up (6%). Complete follow-up data of 363 patients are included in the evaluation. The follow-up rate was 94%. The late morbidity rate and quality of life after DPPHR were reevaluated a median of 5.7 years (range, 0 to 14.4 years, total of 174 months) after surgery. Most of the patients were reinvestigated in the hospital, in the outpatient clinic.

For evaluation of the pain pattern, we used a protocol developed by the EORTC for pain in pancreatic cancer follow-up. Four different evaluation protocols were used, assessing the status of pancreatic pain (pain in the upper abdomen and back), the pattern of abdominal complaints from disorders of digestion, social status, and quality of life (Karnofsky index). The family physician was asked to complete the follow-up protocol, including the quality-of-life evaluation, for patients unable to complete the hospital reinvestigation program because of geographic or professional obstacles. To evaluate the degree of the pain syndrome, a visual analogue scale was used. 32

Statistics

To assess the change in the course of CP after DPPHR, a McNemar test was applied, comparing preoperative and late postoperative data in terms of the degree of upper abdominal pain and the frequency of hospital admission for acute episodes of pancreatitis.

RESULTS

Early Postoperative Results

Four of 504 patients died in the hospital—1 after pulmonary embolism, 1 after general sepsis that led to adult respiratory distress syndrome, and 2 after septic shock from local septic processes uncontrolled by reoperation. The postoperative hospital stay was a median of 14.5 days. Twenty-eight patients required a second surgical procedure (Table 3).

Table 3. EARLY POSTOPERATIVE RESULTS (504 PATIENTS)

* 11/1972–4/1982, Dept. of Surgery, FU Berlin; 5/1982–12/1998, Dept of General Sugery, University of Ulm.

The objective of DPPHR is to treat the severe pain syndrome and complications arising from the inflammatory tumor, including the common bile duct, the pancreatic main duct, the peripapillary narrowing of the duodenum, and the compression or occlusion of the intestinal vessels in the retropancreatic space. As shown in Figure 1, decompression of the common bile duct in addition to the standard reconstruction was required in 123 patients (24%); this was done by performing an additional biliary anastomosis with the excluded jejunal loop. Because of multiple stenoses of the pancreatic main duct, a lateral pancreaticojejunostomy after longitudinal opening of the pancreatic main duct in the body and tail was performed in 46 patients (9%) (Fig. 2). In addition to this modification, a cholecystectomy was performed in 141 patients. The subtotal resection of the pancreatic head resulted in decompression of the portal vein in 67 patients. An open recanalization of the closed portal vein main trunk could be achieved in four patients. Additional pseudocyst anastomosis located in the pancreatic body/tail was performed in seven patients. A splenectomy was necessary in three patients and a pancreatic left or tail resection in two patients.

Figure 1. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection combined with an internal biliary anastomosis.

Figure 2. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection combined with a lateral pancreaticojejunostomy as a sequelae of multiple stenoses of the pancreatic main duct in the body and tail of the pancreas.

Macromorphologic alterations in the pancreatic head observed during surgery are listed in Table 4. In 115 patients, small pseudocystic cavities were discovered in the surgical specimen; in 46 patients, large pancreatic head pseudocysts were identified and resected. Areas of focal necrosis from the acute inflammatory process were observed in 45 patients. A prepapillary main duct stenosis was identified in 187 patients, in 46 of them in combination with a chain of leaks of the pancreatic main duct in the body and tail. In 94 patients, the resection of the pancreatic head resulted in decompression of the narrowed common bile duct without the need for a biliary anastomosis.

Table 4. PATHOMORPHOLOGIC CHANGES IN THE PANCREATIC HEAD WITH INFLAMMATORY MASS

* 11/1972–12/1998

Results of Late Postoperative Follow-Up

A median of 5.7 years after DPPHR, 25 patients had further upper abdominal pain, obviously related to CP (Table 5). Twelve percent of the patients had abdominal discomfort. The average pain score of the 25 patients with upper abdominal pain after DPPHR was 4.8 (Fig. 3).

Table 5. CHANGE IN THE NATURAL COURSE OF CP (388 PATIENTS FOLLOW-UP)*

* 5/1982–10/1996, Dept. of General Surgery, University of Ulm.

† p < 0.0001 (McNemar test)

‡ p < 0.001 (McNemar test)

Figure 3. Pain in chronic pancreatitis after duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR). Of 303 patients, 8.3% had daily, weekly, or monthly pain a median of 5.4 years after DPPHR; 278 were pain-free or suffered rare upper abdominal pain.

Hospital admission for acute episodes of CP dropped from 69% before surgery to 9% late after surgery. Of the 268 patients with acute episodes of pancreatitis, the average number of episodes in the preoperative course was 5.4. Late after surgery, 38 patients had an average of 2.7 acute episodes per patient for which hospital admission was needed. In the late follow-up, pancreatic cancer developed in two patients in the pancreatic head remnant between the intrapancreatic common bile duct and the duodenal wall; four patients had cancer that was not related to the pancreas. The late death rate was 12.6%.

In terms of endocrine function after DPPHR, normal glucose tolerance dropped from 49% before surgery to 39% after surgery. In 21% of the patients, a new diabetes developed during the observation period (Table 6). However, 34 patients (11%) displayed improvement of glucose metabolism, with normal glucose tolerance in comparison to the reduced glucose metabolism that existed before surgery. Of the 303 patients, 208 were professionally rehabilitated; 78 were retired. In terms of quality of life, a Karnofsky Index of 90 to 100 was found in 72% of the patients; in 10%, it was 80 to 90, and in 18%, it was <80. Forty-one percent of the patients still drank.

Table 6. ENDOCRINE FUNCTION AFTER DPPHR

OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; y, median years of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Up to the level of the portal vein, the pancreatic head covers more than one third of the pancreatic tissue. The frequency of the development of an inflammatory mass and the prevalence of pancreatic head enlargement in patients with chronic pancreatitis are not exactly known on the basis of epidemiologic studies. However, clinical observations and the results of immunologic 7,33 and molecular biologic measurements 8–11 underline the hypothesis that the pancreatic head is the pacemaker in CP. 35,36 Further, the head of the pancreas covers two different embryologic parts, creating a double duct system that leads to topical pathomorphologic changes in the pancreatic head resulting from an obstruction of the pancreatic duct in pancreas divisum and pancreaticobiliary maljunction in children and adults. 33 The pathomorphologic changes observed in alcohol-related CP—pseudocystic cavities, small areas of necrosis, prepapillary pancreatic main duct stenosis, stenosis of the intrapancreatic common bile duct, compression of the portal vein, and narrowing of the prepapillary duodenum—are more dominant in the pancreatic head than in the left pancreas as a consequence of the local acute inflammatory processes. The continuous destruction of the pancreatic tissue during the course of CP is characterized by a decrease in pancreatic acinar cells and by a marked increase in extracellular matrix tissue compared with the changes in the body and tail of the pancreas.

In 6% of the patients with CP who had an inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head, a pancreatic cancer developed in the pancreatic head during the medical and surgical treatment periods of a median of 9 years. It has been speculated that the overexpression of growth factors in pancreatic tissue in patients with CP might be related to the process of carcinogenesis in these patients. 10,36

DPPHR results in a subtotal resection of the pancreatic head and the relief of local complications (stenosis of the pancreatic main duct, stenosis of the common bile duct, decompression of the portal and superior mesenteric vein). Its advantage over the Whipple-type resection lies in the preservation of the normal anatomy surrounding the pancreatic head. The standard procedure used to treat pancreatic head complications in CP is the Whipple operation and its major modification, the pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. 38 In three randomized controlled trials, the superiority of the duodenum-preserving technique over the pylorus-preserving resection has been demonstrated in CP. 38–40

Several long-term observations reveal a decrease in pain in the course of CP. Lankisch et al reported that the incidence of relapsing pain attacks decreased during the observation period. 20 Eighty-five percent of the patients still had pain in the follow-up period of up to 5 years; in the observation period of 5 to 10 years, 68% had pain, and even after >10 years 53% of patients still had pain. 21 A similar observation was published by Miyake et al; they found that only 48.2% of patients with CP were pain-free within 5 years. 24 In this series, 91.3% of the patients were pain-free in an observation period of up to 14 years after DPPHR. During the observation period, only 12.5% of the patients had further acute episodes with the need of hospital admission resulting from CP. Acute episodes of CP dropped from 69% before surgery to 9% after surgery. DPPHR eliminates the inflammatory process in the pancreatic head and also relieves local complications. This explains the favorable result of a pain-free status in 89% to 92.8% of patients during the cumulative observation period of 26 years.

In comparison to the Whipple resection and the pylorus-preserving modification, DPPHR offers the major advantage of preserving the extrahepatic biliary tree, the stomach, and the duodenum. Due to the preservation of the duodenum, the endocrine function of the pancreas is preserved early after surgery. 3,30,34 The antiinsulin hormones glucagon and somatostatin 41 are reduced. The improvement of endocrine function in 5.5% to 15% of patients after DPPHR is the result of the reduction of basal glucagon and somatostatin levels. In 21% of the patients there was a new incidence of diabetes mellitus. However, the new incidence of diabetes in 64 patients must be weighed against the improvement of glucose metabolism in 34 patients in the long-term follow-up after DPPHR. After a median follow-up of 9.8 years, Lankisch et al 20 observed a normal endocrine function status in alcoholic CP in only 17% of patients; 81% of the patients had moderate or severe endocrine insufficiency.

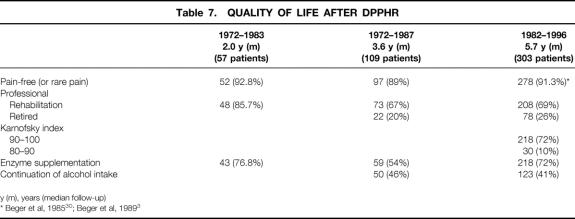

In terms of quality of life after DPPHR, 69% of the patients were professionally rehabilitated and 26% retired; only 5% of the patients were unable to work because of their illness. After DPPHR, only 18% of the patients had a reduced quality of life score; 72% of the patients scored within the normal range on the Karnofsky Index (Table 7).

Table 7. QUALITY OF LIFE AFTER DPPHR

Three studies with a comparable observation time (6.3 to 9.8 years in median) revealed a death rate of 20.8% to 35% in patients with CP. 20,23,24 After DPPHR, the death rate was 8.9% and 12.6% in two groups with a median observation time of >5 years (Table 8). Half of the patients died after the development of gastrointestinal tract cancer outside of the pancreas. The lower late mortality rate after DPPHR compares favorably with the late mortality rate after the Whipple procedure. 42–44 In the series between 1982 and 1996, in 6.3% of the patients a ductal pancreatic cancer was observed in the pancreatic head after a long period of clinical treatment for CP. This underlines the increased risk of pancreatic head cancer in patients with CP and an inflammatory mass. In comparison to drainage procedures in CP, the subtotal resection of the pancreatic head minimizes the risk of overlooking a malignant lesion developing in the course of CP. 45,46

Table 8. DPPHR IN CP CHANGES THE NATURAL COURSE OF THE DISEASE

* y (m), years (median follow-up)

CONCLUSION

In patients with alcoholic CP in whom an inflammatory mass has developed in the head of the pancreas, DPPHR results in a change of the natural course of the disease with regard to pain status, frequency of acute episodes of CP, need for further hospital admissions, late mortality rate, and quality of life. These data confirm the observation of others of a delay of the progressive loss of pancreatic function after surgical treatment. 47–50 Regarding the significant association between alcoholic CP and pancreatic cancer, DPPHR may have a preventive effect in terms of the development of pancreatic head cancer in patients with an inflammatory mass. Because of the removal of the inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head and the maintenance of the bilioduodenal functions, DPPHR results in low morbidity and mortality rates in the early and late postoperative course (see Table 8). For this reason, it offers the option of treating complications and the pain syndrome without causing additional surgical complications.

Discussion

Dr. Richard A. Prinz (Chicago, Illinois): I congratulate Professor Beger and his colleagues for their ongoing studies of chronic pancreatitis, a disease that can be both challenging and frustrating for surgeons.

The duodenal-preserving resection of the head procedure that they have developed and championed has not been widely adopted in this country, where lateral pancreaticojejunostomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy continue to be the two most common procedures used to treat the intractable pain of chronic pancreatitis. The choice between these two approaches often hinges on whether the pancreatic duct is dilated or not.

This distinction does not seem to be important in your choice of the duodenal-preserving pancreatic head resection. In my understanding, the key factor is whether or not the patient has an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. If so, what operative procedure do you perform for the patient with painful chronic pancreatitis who does not have an inflammatory mass in the head? And can you give us some idea of the frequency of this type of patient in your population?

Your results in terms of pain relief are unparalleled, with 90% of patients being pain free an average follow-up of over 5 years. Can you be more specific and tell us how your patients were reevaluated and how the presence or absence of pain was determined? Was a nonbiased standardized method used? And if so, in how many patients?

Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy removes as much or even more pancreatic parenchyma and decompresses surrounding structures, as does the duodenal-preserving pancreatic head resection. Yet it does not seem to achieve a 90% rate of complete pain relief. How do you explain this difference?

You utilized a number of modifications to the basic Beger procedure such as performing a common bile duct anastomosis and/or a main pancreatic duct anastomosis. Was there any difference in pain relief with these modifications?

Continued alcohol intake has a negative influence on pain relief in most series. Obviously, German beer is very good, so I am sure, as you pointed out, many of your patients continue to drink. Did continued alcohol intake adversely affect outcomes in your patients or not?

Finally, have you studied the patients who continue to have pain or who have had recurrent pancreatitis after your procedure to determine why they differ from the larger group that did benefit from your operation? If so, have you found any anatomic explanation for this difference?

How do you treat those patients who do have continued pain or continued admission for pancreatitis? You report that at least seven of your patients had a reoperation for either pain or tumor. What operation was performed and what was the outcome?

Presenter Dr. Hans G. Beger (Ulm, Germany): About 15% of all patients operated upon for painful chronic pancreatitis were treated by a drainage procedure using the Partington-Rochelle technique. The indication for a drainage procedure was duct dilatation of the pancreatic main duct, mostly in connection with a stenosis in the prepapillary pancreatic main duct located in the pancreatic head.

For evaluation of the pain pattern, we used a protocol which was developed by the EORTC for pain in pancreatic cancer follow-up. Four different evaluation protocols were used, referring to: 1) the status of pancreatic pain (pain in the upper abdomen and back), 2) pattern of abdominal complaints due to disorders of digestion, 3) social status elevation, and 4) quality of life evaluation using the Karnofsky index.

Of the 388 patients, followed in median for 5.7 years with a maximum postoperative follow-up of 14 years, 303 patients are included with a complete follow-up. Ten patients had to be reoperated after duodenal-preserving resection; six of these patients developed stenosis of the common bile duct in the intrapancreatic common bile duct segment. The development of a postoperative common bile duct stenosis was caused by an inflammatory process in the wall of the common bile duct.

Four patients had a Whipple procedure due to a persisting inflammation in the residual pancreatic head, probably due to an incomplete resection of the inflammatory mass during the primary surgical resection of the pancreatic head.

Your fourth question refers to the indication for duodenum-preserving head resection in chronic pancreatitis. On the basis of CT investigations, 75% of the 504 patients had an enlargement of the head with an inflammatory mass in combination with local complications like common bile duct stenosis and abdominal pain. However, 25% did not show—on the basis of CT investigation—an enlargement of the pancreatic head. In this group of patients, the major inflammation—on the basis of macroscopic intraoperative observation and palpation—displayed an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. The patients without an enlargement of the pancreatic head in chronic pancreatitis to whom the duodenum-preserving head resection was applied responded promptly in terms of being postoperatively free of pain.

Comparing duodenum-preserving head resection with pylorus-preserving resection in chronic pancreatitis, in the early ’90s we did a randomized clinical trial including in each group 20 patients with well-established, complicated, and advanced chronic pancreatitis. The data were published in the American Journal of Surgery (1997;169:65). We learned from the results of this prospective clinical trial that duodenum-preserving head resection is superior to pylorus-preserving head resection in chronic pancreatitis; after duodenum-preserving head resection, patients showed better pain reduction, early increase of body weight, almost normal gastric emptying, no episodes of cholangitis, and no significant reduction of the endocrine function in comparison to pylorus-preserving resection.

Dr. Ingemar Ihse (Lund, Sweden): Being a European, I am proud to have been given the opportunity to read and discuss this paper. Dr. Beger has during the years made numerous contributions not only to European surgery but also to world surgery, and what we have heard today is just one of them. Still, it is an impressive series of more than 500 patients operated on and followed up prospectively since 1972. The results presented of the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection in patients with chronic pancreatitis are extraordinary.

In retrospect, one can regret that this huge series was not used for more appropriate and bigger randomized controlled studies than the one you in fact did, comparing the Beger operation with the standard procedure for chronic pancreatitis, which is still the Whipple operation. If so, we would probably have had a better knowledge today of which of the two procedures to recommend. We would furthermore have had a better chance to judge to what extent surgery may interfere with the natural course of chronic pancreatitis.

I have a couple of questions for you, Dr. Beger.

The first one refers, like one of Dr. Prinz’s questions, to the evaluation of pain relief. You have in part already answered this question. Pain and chronic pancreatitis varies markedly over time. During the long follow-up time of maximally 26 years, you seem to have measured pain at four occasions only. The message of this study would certainly have been more convincing if pain had been measured more longitudinally and also if an attempt had been made to estimate the need for painkillers.

Secondly, I am interested to hear your explanation of the cause of the improved glucose tolerance after surgery in 11% of the patients. Is it just a result of better dietary regimens and physical exercise, or do you see other explanations? I ask because we have made similar observations in patients who were resected for pancreatic cancer.

Thirdly, I was concerned about the high number of pancreatic cancers in the series, in fact, 6.3%. Are all of them really cancers arising in chronic pancreatitis? Or can some be primary cancers with a secondary obstructive pancreatitis?

Finally, you say in your manuscript that 59% in fact stopped drinking after the operation. This is too good to be true—at least for a Swede. Please comment or correct my statement.

Dr. Beger: Five hundred and four patients were reevaluated in 1983, 1987, 1994, and 1996 to objectify the postoperative pain pattern. To measure the pain objectively, only in the 1996 follow-up protocol was the application of a visual analogue scale for pain applied. In comparison to the preoperative pain status, only the categories daily severe, weekly, monthly, and yearly pain were used. In the last follow-up check after 5.7 years in median, the patients with pancreatic pain showed a score of 4.8 VAS points.

One advantage of the duodenum-preserving head resection in chronic pancreatitis is the conservation of endocrine function. In a small group of patients we objectified a postoperative improvement of the glucose metabolism. In the early ’80s we were able to objectify the reason for the improvement of endocrine function after duodenum-preserving resection. At 3 to 6 months after duodenum-preserving head resection, patients demonstrated a decrease in the level of unstimulated glucagon and somatostatin toward a normal basal level. The hyperglycemic effect of the increased hormone level is reduced after duodenum-preserving resection. A second reason for the conservation of endocrine function is the preservation of the duodenum. The duodenum regulates, as the major endocrine organ of the intestine, glucose metabolism and insulin secretion.

The Whipple procedure, anticipated by Walter Kausch in 1912, is a surgical technique for oncological diseases in the periampullary region. I do not consider the Whipple procedure a standard surgical procedure in chronic pancreatitis, because it is an overtreatment in terms of treatment of pain and local complications.

The frequency of pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis in this group of patients was surprisingly high. All patients in the last follow-up were preoperatively treated for chronic pancreatitis and pain for in median 3.6 years. The treatment period of in median 3.6 years for chronic pancreatitis excludes patients suffering from primary pancreatic cancer and secondary chronic pancreatitis. In 24 patients, we had to change the surgical technique, either intraoperatively, because of frozen section objectification of a ductal cancer in chronic pancreatitis, or as a second oncological resection days after the first resective procedure because of a histologically proved cancer in chronic pancreatitis. The patients with pancreatic cancer were not included in this evaluation. In two additional patients, we were surprised to realize that they developed a pancreatic head cancer in the late follow-up after duodenum-preserving head resection. To one of these patients, we applied a Whipple procedure because of an increase of CA 19-9 in the peripheral blood. Pathological examination of the operative specimen revealed severe dysplasia but not pancreatic cancer.

Forty-one percent of the patients in the last follow-up continued to drink alcohol. We did not evaluate the degree of alcohol intake. Most of the patients were postoperatively professionally rehabilitated; the disease chronic pancreatitis started when they were aged between 30 and 40; at the time of surgery the mean age was 44. We concluded, in terms of the continuation of alcohol intake, that these patients were not alcoholics but used alcohol as a standard inclusion of a dinner.

Dr. Andrew L. Warshaw (Boston, Massachusetts): This large and remarkable series of resections for pancreatic cancer clearly demonstrates that one can attain excellent symptomatic relief and return to work for patients. I see two principal messages in your work. One is a message to the internists and gastroenterologists who doubt that surgeons can make a difference in the health and quality of life of these patients. And you clearly send the message to them that surgery can. The questions that I would really like to address are for the surgeons among us who say, is this operation really superior to its alternatives?

The first problem I have with trying to decide about this operation is that I am not sure that I understand how to delineate the patient group that you are addressing, those with the inflammatory mass of the pancreatic head. There seems to be a difference either in our patients or in my eyes as to how one defines an inflammatory mass and what the threshold is.

The related question is whether and why your local resection of part of the pancreatic head might be better than pancreaticoduodenectomy—either the Whipple operation or the pylorus-preserving variant of that operation. Both of those operations remove the pancreatic head more completely than the operation you are describing, and also deal with complications compromising the lumen of the bile duct, duodenum, or portal vein. Most series of the Whipple operation nonetheless have not achieved full pain relief in 90% of patients, as you report. Like Dr. Prinz, I am not sure whether this is a difference in observation, evaluation, or actual accomplishment.

Another important point relates to preservation of pancreatic function. The title of your paper implies that you are changing the natural course of the disease, which prominently includes the functional components. However, 86% of your patients were exocrine-insufficient preoperatively, and you provide no evidence of improvement or even stabilization of exocrine function. In our own series of chronic pancreatitis treated with Whipple or pylorus-preserving resection, 70% of our patients need enzyme replacement. Nonetheless, at 6 months after those resectional operations, the mean body mass index was 23, with no difference between the two operations, and many of the patients had gained weight back to higher than their preoperative levels. I do not see an advantage to the duodenum-preserving operation in this regard, in spite of the fact that you have saved the duodenum with its CCK and secretin production.

Twenty-five percent of your patients were insulin-dependent preoperatively and 44% postoperatively. By comparison in our series of pancreaticoduodenectomies, 15% were insulin-dependent preoperatively and 25% after resection. What is the evidence for improved glucose tolerance after duodenum-preserving head resection? Is it merely a function of lost body mass?

Your outcomes set a standard for everyone else to emulate, Professor Beger, but I am not convinced that they are dependent upon preservation of the duodenum.

Dr. Beger: The definition of an inflammatory mass is based on the preoperative CT investigation, ERCP or MRCP, and the intraoperative observation. Pathomorphological criteria of an inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head in chronic pancreatitis are small tissue necroses, small cystic cavities, pseudocystic lesions, common bile duct stenosis, pancreatic main duct stenosis, and prestenotic dilatations and compression of the retropancreatic vessels (portal vein and superior mesenteric vein).

Your question targets the evaluation of postoperative pain. Pancreatic pain was considered to be present if the patient complained about pain in the upper abdomen or back above the umbilicus. To discriminate pancreatic pain from other occasional painful disorders related to the process of food digestion, e.g., diarrhea, flatulence, the pattern of abdominal complaints in the upper and lower abdomen was specifically evaluated.

In terms of the postoperative functions of the exocrine pancreas using the pancreolauryl test, we have not been able to demonstrate an improvement of the exocrine function in the late follow-up of the patients. The reentrance of the jejunal loop, draining the pancreatic juice of the left pancreas, is above 20 cm below Treitz’s ligament. Duodenum-preserving resection of the pancreatic head in chronic pancreatitis does not result in an improvement of the decreased exocrine pancreatic function; however, one third of the patients in the late follow-up did not use any oral enzyme supplementation.

I consider the preservation and, in a smaller patient population, the improvement of the endocrine function as a major advantage of the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection in comparison to the classical Whipple resection. In the long postoperative follow-up, 11% showed an improvement, 21% a deterioration of the exocrine function. Improvement of the endocrine function was considered objectified if the patient changed from the status of insulin dependence to insulin independence and from latent diabetes to a nearly normal glucose metabolism.

Dr. Charles F. Frey (Sacramento, California): My compliments to the authors of this excellent report, particularly to Professors Beger and Buechler, who have devoted their professional lives to improving our understanding of pancreatic disease.

I would like Professor Beger, if he would, to enumerate which markers of outcome he attributes to the effects of the operation and which might be influenced to an appreciable extent by the patient population he treated in Germany. There are two outcome measures which come to mind in this regard, and that is his late mortality figures and the percentage of his patients who return to work.

When I examined our operative experience in Sacramento, we had a greater number of late deaths, and far fewer of our patients returned to a gainful occupation than in Germany. Yet when your operation and my operation were compared, in a German population in Hamburg by Jacob Izbicki as reported in the December 1998 issue of Annals of Surgery (1998;228:771–9) in a randomized prospective trial, there were no significant differences in the markers of outcome you cited in your report today, including late deaths and return to work status.

I believe we have in the public hospitals in the United States among our patients with chronic pancreatitis a higher rate of narcotic addiction, binge-type drinking, frequent absence of family support, a dearth of social services, and a higher percentage of uninsured patients than in Germany.

Would the authors comment on the incidence of narcotic addiction in their patient population and on what support services are available to patients in Germany with a history of alcoholism and narcotic addiction and what percent of their patients were insured and if they believe these factors may be important in influencing their favorable outcomes regarding late mortality and a high rate of return to work.

Dr. Beger: The markers of outcome we used are the pain status, particularly “free of pain” or “rare (yearly) pain episodes” and “reappearance of pancreatic pain,” the status of employment, professional rehabilitation, and the quality of life. For quality of life evaluation, we used the Karnofsky index. We considered the social situation of a patient as important for the outcome evaluation; most important was the status of professional rehabilitation. In Germany, 100% of the population are health-care–insured and they all have access to the social welfare measures provided by the health care insurances. This might be contribute to the beneficial long-term results in terms of quality of life. A comparison of the results of this prospective follow-up evaluation with the results of a small group of patients with chronic pancreatitis recently published by Izbicki is misleading. Izbicki compared duodenum-preserving with Frey’s coring-out modification of the Partington-Rochelle drainage procedure; however, the follow-up was short, and therefore incomparable to the presented data.

Dr. John Terblanche (Cape Town, South Africa): I too rise to congratulate Dr. Beger on his remarkable results in a very large series. I would point out that the operation you describe is an extensive one. After I listened to Dr. Frey’s presentation to this Association in 1994, the Cape Town group changed to his procedure. I have two questions.

Firstly, those of us in the HPB field need to train our Fellows. Training them to do Dr. Frey’s procedure is easier than training them to do the procedure that you describe and certainly easier than training them to do a Whipple procedure in this setting. We do perform the Whipple procedure when necessary, but prefer the Frey procedure for the majority of patients.

The second question is, it seems to me that the same operation performed in different parts of the world for patients with painful chronic pancreatitis often gives different results. Do you think that is because the patients are different, the pancreatitis is different, or is it perhaps that the surgeons are different?

Dr. Beger: I consider the duodenum-preserving head resection not as a simple surgical procedure. However, over the years, it has become a well-standardized surgical technique. Most important is the rotation of the pancreatic head after transection of the pancreatic neck on the level of the portal vein into the ventral-dorsal position and the subtotal resection of the pancreatic head toward the intrapancreatic common bile duct segment. In comparison to the coring-out technique of Dr. Frey, which is a modification of the Partington-Rochelle drainage procedure, the duodenum-preserving head resection leads to a subtotal resection of the pancreatic head; the wet weight of the operative specimen figures between 25 and 45 g. Dr. Frey published a wet weight of the operative specimen of about 5 g. In comparison to the Whipple procedure, the duodenum-preserving head resection maintains the gastroduodenal passage and the biliary functions.

The social status of the patient influences the quality of life. But points that contribute to the beneficial outcome of the patients after duodenum-preserving head resection are freedom from pain, ability to resume professional work, and a low level of other abdominal discomforts. These endpoints are rather related to surgical techniques than to surgeons.

Dr. L. William Traverso (Seattle, Washington): Professor Beger, congratulations on a lifetime of work. Over two decades ago, you described this operation, began using it, and followed up with much data for all of us to consider. Yours is a very admirable experience.

I agree that resection of the head is the key in these patients that have the pacemaker of pancreatitis as the main cause of their pain. The indications for head resection we also agree on, that the patient must have disabling pain plus have severe anatomic findings in the head of the pancreas, which indicates that removing it will help.

Now that you have looked back over 26 years of experience, my questions are: Have you noticed a change in your own operative experience for all patients that you operate on for chronic pancreatitis? What percent of your patients do you do this procedure on versus some other procedure like a distal pancreatectomy or a Puestow? How have your operative times changed from the beginning until now? What is your average blood loss and how has that changed?

In my own experience with chronic pancreatitis, I am doing slightly less pancreatic head resections and using more technology to extend the resection into the head using Dr. Frey’s procedure or a Puestow plus electrohydraulic lithotripsy to open up the ductal system and get clear stones all the way into the duodenum. All these things result in a very high pain relief pattern—not quite 91%, however. I do believe that the experience that you have shown in the German population is truly superb.

Dr. Beger: In terms of the etiology of chronic pancreatitis, 81% of the patients suffered from an alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis. We consider alcohol as the etiological factor of chronic pancreatitis to be related with the development of an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. In the referred period, 842 patients with chronic pancreatitis were transmitted for surgical treatment. Of these, 15% had a duct drainage procedure, 12% a left resection, 59% a duodenum-preserving head resection, 6% a pylorus-preserving head resection, and 1% a Kausch-Whipple resection. A few patients underwent the coring-out technique (Frey modification of coring out the ventral part of the pancreatic head). The pylorus-preserving head resection is indicated in patients with chronic pancreatitis and a suspicion of an additional malignant lesion in the pancreatic head.

Dr. John M. Howard (Whitehouse, Ohio): Dr. Beger, may I first pay tribute to the scholarly role, the leadership role, you have played. We appreciate it.

In order to prove that you have changed the course of the disease, it seems to me you have to show that atrophy and disappearance of the acini have ceased and that the scar tissue has not increased. So we would be interested in autopsy data down the line for comparison.

Secondly, as has been pointed out, your incidence of diabetes has increased, not diminished. And resection resects cells which produce the hormones that raise the blood sugar as well as those that lower it. So the increased incidence of diabetes after resection is probably not the result of resection per se. Frankly, I don’t know why we have diabetes in the first place.

Next, do you agree that complete portal vein thrombosis is an absolute or near-absolute contraindication for resection of the head of the pancreas? If you resect it, you may get acute splanchnic mesenteric venous hypertension and serious, even fatal, problems.

Your incidence of cancer: I would like for you to tell us again whether you think that the cancers you found developed in the course of chronic pancreatitis or had been there from the beginning of the patients’ problems.

Finally, how do you handle the pancreatic duct, transected pancreatic duct, on the ampullary side of the transection?

Dr. Beger: In terms of autopsy studies, we have incomplete data. The four patients who died in the hospital after a pulmonary embolism (1 pt.), two patients had a sepsis uncontrolled by repeated surgical drainage procedures, and one patient died following a septic shock syndrome without a septic focus. The late mortality was 13%. The causes of death in these patients were reported as follows: six patients died after development of GI-tract cancer (esophagus, stomach, large-bowel, and lung cancer), five died in the final state of liver cirrhosis, four patients as a consequence of a traffic accident, four patients as a consequence of a severe type of acute pancreatitis attack, three patients after myocardial infarction, and two patients as a consequence of renal insufficiency. Two patients committed suicide. Portal vein occlusion or thrombosis are in my view not a contraindication for surgical resection of the pancreatic head. In four patients we were able to recanalize the occluded portal vein in the group of duodenum-preserving head resection.

Your question about the high incidence of pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis needs to be further evaluated. We were surprised by the incidence of 6.3% of ductal pancreatic cancer development within a period of 26 years in this subgroup of patients with an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. This observation underlines the data of Lowenfels, published 1993 in the New England Journal of Medicine, about the increasing risk of the development of ductal pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Hans G. Beger, MD, University of Ulm, Department of Surgery, D-89070 Ulm, Germany.

Presented at the 119th Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, April 15–17, 1999, Hyatt Regency Hotel, San Diego, California.

Accepted for publication April 1999.

References

- 1.Sarles H, Bernard JP, Johnson C. Pathogenesis and epidemiology of chronic pancreatitis. Ann Rev Med 1989; 40: 453–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiMagno EP, Layer P, Clain JE. Chronic pancreatitis. In: Go VWL, DiMagno EP, Gardner JD, eds. The pancreas. 21st ed. New York: Raven Press; 1993: 655–706.

- 3.Beger HG, Büchler M, Bittner R, et al. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in severe chronic pancreatitis. Early and late results. Ann Surg 1989; 209: 273–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elsässer HP, Adler G, Kern HF. Time course and cellular source of pancreatic regeneration following acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 1986; 5: 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Laethem JL, Devière J. Pancreatitis and cytokines. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 1996; 59: 186–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marquart F, Gillery XP, Kalis B, Borel JP. Cytokines and fibrosis. Eur J Dermatol 1994; 4: 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahl SM, McCartney-Francis N, Mergenhagen SE. Inflammatory and immunoregulatory roles of TGFβ. Immunol Today 1989; 10: 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friess H, Yamanaka Y, Büchler M, et al. Cripto, a member of the epidermal growth factor family, is overexpressed in human pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Int J Cancer 1994; 56: 668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friess H, Yamanaka Y, Büchler M, et al. Increased expression of acidic and basic fibroblast growth factors in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Pathol 1994; 14: 117–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korc M, Friess H, Yamanaka Y, et al. Chronic pancreatitis is associated with increased concentrations of epidermal growth factor receptor, transforming growth factor, and phospholipase C. Gut 1994; 35: 1468–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friess H, Yamanaka Y, Büchler M, et al. A subgroup of patients with chronic pancreatitis overexpress the c-erb B-2 protooncogene. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gress TM, Menke A, Bachem M, et al. Role of extracellular matrix in pancreatic diseases. Digestion 1998; 59: 625–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gress M, Müller-Pillasch F, Elsässer HP, et al. Enhancement of transforming growth factor 1 expression in the rat pancreas during regeneration from caerulein-induced pancreatitis. Eur J Clin Invest 1994; 24: 679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunger R, Müller C, Z’graggen K, et al. Cytotoxic cells are activated in cellular infiltrates of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1656–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: Treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1998; 115:763–764. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Bockman DE, Büchler MW, Malfertheiner P, Beger HG. Analysis of nerves in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1988; 94: 1459–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Büchler MW, Weihe E, Friess H, et al. Changes in peptidergic innervation in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 1992; 7: 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiSebastiano P, Fink T, Weihe E, et al. Immune cell infiltration and growth-associated protein. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1648–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friess H, Zhu Z, Martignoni ME, et al. Nerve growth factor (NGF) regulates nerve growth and pain in chronic pancreatitis. Langenbeck’s Arch Chir I, Forumband 1999, 745–750.

- 20.Lankisch PG, Löhr-Happe A, Otto J, Creutzfeldt W. Natural course in chronic pancreatitis. Pain, exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency and prognosis of the disease. Digestion 1993; 54: 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lankisch PG. Natural course of chronic pancreatitis. In: Izbicki JR, Binmoeller KF, Soehendra N, eds. Chronic pancreatitis. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co; 1997: 1–14.

- 22.Thorsgaard Pedersen N, Andersen BN, Pedersen G, Worning H. Chronic pancreatitis in Copenhagen: : a retrospective study of 64 consecutive patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 1982; 17: 925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammann RW, Akovbiantz A, Largiadèr F, Schueler G. Course and outcome of chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal study of a mixed medical-surgical series of 245 patients. Gastroenterology 1984; 86: 820–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyake H, Harada H, Kunichika K, Ochi K, Kimura I. Clinical course and prognosis of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 1987; 2: 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 1433–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. Prognosis of chronic pancreatitis:: an international multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89: 1467–1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlosser W, Schoenberg MH, Poch B, et al. Die duodenumerhaltende Pankreaskopfresektion bei chronischer Pankreatitis mit entzündlichem Pankreaskopftumor. Z Gastroenterol 1996; 34: 735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beger HG, Büchler M. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis with inflammatory mass in the head. World J Surg 1990; 14: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malfertheiner P, Büchler M, Müller A, et al. Fluorescein dilaurate serum test:: a rapid tubeless pancreatic function test. Pancreas 1987; 2: 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beger HG, Krautzberger W, Bittner R, et al. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. Surgery 1985; 97: 467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Büchler MW, Firess H, Bittner R, et al. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection: : long-term results. J Gastrointest Surg 1997; 1: 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lankisch PG, Andren-Sandberg A. Standards for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and for the evaluation of treatment. Int J Pancreatol 1993; 14: 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widmaier U, Schmidt A, Schlosser W, Beger HG. Die duodenumerhaltende Pankreaskopfresektion in der Therapie des Pancreas divisum. Chirurg 1997; 68: 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beger HG, Witte C, Krautzberger W, Bittner R. Erfahrung mit einer das Duodenum erhaltenden Pankreaskopfresektion bei chronischer Pankreatitis. Chirurg 1980; 51: 303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beger HG, Krautzberger W, Gögler H. Résection de la tête du pancréas (pancréatectomie céphalique) avec conservation du duodénum dans les pancréatites chroniques, les tumeurs de la tête du pancréas et la compression du canal choledoque. Chirurgie 1981; 107: 597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sirivatanauksorn V, Sirivatanauksorn Y, Lemoine NR. Molecular pattern of ductal pancreatic cancer. Langenbeck Arch Surg 1998; 383: 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.AGA Technical Review. Treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1998; 115: 765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Büchler MW, Friess H, Müller MM, Beger HG. Randomized trial of duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection versus pylorus-preserving Whipple in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg 1995; 169: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klempa I, Spatny M, Menzel J, et al. Pancreatic function and quality of life after resection of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis. A prospective, randomized comparative study after duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas versus Whipple’s operation. Chirurg 1995; 66: 350–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyakawa S, Hayakawa M, Horiguchi A et al. Estimation of fat absorption with the 13C-trioctanoin breath test after pancreatoduodenectomy or pancreatic head resection. World J Surg 1996; 20: 1024–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bittner R, Butters M, Büchler M, et al. Glucose homeostasis and endocrine pancreatic function in patients with chronic pancreatitis before and after surgical therapy. Pancreas 1994; 9: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howard JM. Surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis. In: Howard JM, Jordan GL Jr, Reber HA, eds. Surgical disease of the pancreas. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1987: 496–521.

- 43.Christiansen J, Olsen JH, Worning H. The pancreatic function following subtotal pancreatectomy for cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol 1971; 6(Suppl): 189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lankisch PG, Fuchs K, Peiper HF et al. Pancreatic function after drainage or resection for chronic pancreatitis. In: Mitchell CJ, Kallcher L, eds. Pancreatic disease in clinical practice. London: Pitman Publishing; 1981: 362–369.

- 45.Warren KW. Surgical management of chronic relapsing pancreatitis. Am J Surg 1969; 117: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warshaw AL, Popp JW Jr, Schapiro RH. Long-term patency, pancreatic function, and pain relief after lateral pancreaticojejunostomy for chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1980; 79: 289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frey CF, Amikura K. Local resection of the head of the pancreas combined with longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy in the management of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 492–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frey CF, Smith GJ. Description and rationale of a new operation for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 1987; 2: 701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nealon WH, Thompson JC. Progressive loss of pancreatic function in chronic pancreatitis is delayed by main pancreatic duct decompression: : a longitudinal prospective analysis of the modified Puestow procedure. Ann Surg 1993; 217: 458–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia-Pugés AM, Navarro S, Ros E, et al. Reversibility of exocrine pancreatic failure in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1986; 91: 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]