Abstract

During infection, Renibacterium salmoninarum survives within the pronephric macrophages of salmonid fish. Therefore, to study the initial phases of the interaction we infected macrophages with live bacteria and analysed the responses of host and pathogen. It was found that the expression of msa encoding the p57 antigen of R. salmoninarum, was constitutive, while the expression of hly and rsh, encoding haemolysins, and lysB and grp was reduced after infection. Macrophages showed a rapid inflammatory response in which the expression of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II), inducible cyclo-oxygenase (Cox-2), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) was enhanced, but tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) expression was greatly reduced initially and then increased. After 5 days, except for TNF-α and MHC II, expression returned to levels approaching those of uninfected macrophages. We propose that R. salmoninarum survives initial contact with macrophages by avoiding and/or interfering with TNF-α-dependent killing pathways. The effects of specific R. salmoninarum components were studied in vivo by injecting fish with DNA vaccine constructs expressing msa, hly, rsh, lysB, or grp. We found that msa reduced the expression of IL-1β, Cox-2, and MHC II but stimulated TNF-α while hly, rsh and grp stimulated MHC II but down-regulated TNF-α. Constructs expressing hly or lysB stimulated iNOS expression and additionally, lysB stimulated TNF-α. The results show how p57 suppresses the host immune system and suggest that the immune mechanisms for the containment of R. salmoninarum infections rely on MHC II- and TNF-α-dependent pathways. Moreover, prolonged stimulation of TNF-α may contribute to the chronic inflammatory pathology of bacterial kidney disease.

Introduction

Renibacterium salmoninarum is an obligate pathogen of salmonid fish that causes a chronic infection, bacterial kidney disease (BKD).1 The pathogen is a slowly growing, Gram-positive bacterium that survives within the macrophages of the kidney2 and can be transmitted both vertically inside the ova and horizontally between cohabiting fish.3,4 Antibiotic treatment and vaccination are unable to prevent or cure BKD and immunization may exacerbate the disease.1 Renibacterium salmoninarum is a highly conserved genospecies and most probably evolved in close association with the salmonid host.5 BKD is widespread and is responsible for substantial losses in propagated and wild salmonids.

The chronic course of BKD is reminiscent of mycobacterial infections involving a balance between components of the immune response, which can be tipped in favour of host or pathogen depending on environmental and genetic factors.6 Infections in ovo may involve the transmission of as few as one or two bacterial cells7 and BKD may or may not become active in later life following a prolonged period of incubation and, perhaps, physiological changes induced, for example, by changes in water temperature and quality, nutritional status, or hormone balance, such as occur during smolting and spawning.8,9 Much of the histopathology of BKD represents a granulomatous inflammatory reaction by the host in an attempt to encapsulate the pathogen. Typically, there is extensive tissue damage, a strong cell-mediated response, macrophage proliferation and activation, and probably the deposition of immune complexes in the kidney, spleen and liver, and a type III hypersensitivity response.10 Antibody responses to R. salmoninarum do not provide protection and may promote some aspects of the pathology as well as the intracellular survival of the bacterium.1,11 Phagocytosis of R. salmoninarum induces reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) that inhibit but do not eliminate the pathogen, which subsequently escapes into the cytoplasm.2,12–15 Nevertheless, acute infections can be resolved, possibly as a consequence of a temperature-dependent T-cell response, although carriers, latency and relapse are common.8

How R. salmoninarum modulates the host immune response to its advantage and the factors that contribute to the immunopathology have received little attention. Studies of the interaction between host and pathogen have centred on the major soluble antigen, p57, encoded by the gene msa,16 which is produced and secreted in relatively large quantities by R. salmoninarum in the tissues of infected hosts.17 The p57 protein interferes with the development of normal immune responses and suppresses the production of ROI and antibodies.17,18 Furthermore, vaccination studies have shown that immunizing with p57 may exacerbate the disease.19 Other components that may contribute to pathogenicity include genes encoding a metalloprotease, hly,20 and a haemolysin, rsh,21 that are expressed in cultured cells infected with R. salmoninarum22 and may be recognized by the host immune system during clinical disease.23 It has been reported recently that immunization with the components encoded by hly and rsh reduced mortalities among fish subsequently challenged with R. salmoninarum but the reasons for this are unknown.24

In order to investigate the early phases of the interaction of R. salmoninarum with pronephric macrophages, we studied the kinetics of expression of msa, hly, rsh and other selected R. salmoninarum genes and also host cytokine and cytokine-related genes following infection in vitro. To determine the role of specific R. salmoninarum genes in vivo, we examined the responses of pronephric leucocytes to DNA vaccine constructs separately expressing msa, hly, rsh, and two novel genes, lysB and grp.

Materials and methods

Pronephric macrophages

Macrophages were prepared from the head kidney of healthy 200-g rainbow trout maintained at 16° using the method described by Secombes.25 Briefly, the pronephros was removed, disaggregated and suspended in Leibovitz's L-15 medium (L-15) containing 2% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), 10 U/ml heparin (H), 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (P/S) (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). The cell suspension was layered onto a discontinuous density gradient of 34%/51% Percoll and centrifuged at 500 g for 35 min. The macrophage fraction was harvested, washed and resuspended to a density of 1 × 107 cells/ml in L-15 supplemented with 5% (v/v) FCS + H + P/S. After 24 hr the culture medium was replaced with fresh L-15 + 5% FCS + H, the cells were counted, and their viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion.

Renibacterium salmoninarum culture and DNA extraction Renibacterium salmoninarum 980036-150, isolated from a recent confirmed clinical outbreak of BKD, was cultured for 6 weeks on selective kidney disease medium (SKDM) from freeze-dried stocks and the genomic DNA was extracted from the bacteria as previously described.26

Infection of pronephric macrophages

Broth cultures of R. salmoninarum were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in L-15 + 5% FCS + H to a concentration of 1 × 108 cells/ml. The viability and purity of the cultures was assessed by spread plating onto SKDM and nutrient agar, respectively, and incubation at 15°, 25° and 30°. R. salmoninarum does not grow on nutrient agar nor at temperatures over 22°.1 The infection of macrophages with R. salmoninarum was performed using previously described methods.2 Briefly, bacterial suspensions were added to the macrophage suspensions at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0·7, 5, or 10 and the cultures were gently rotated at 10 r.p.m. for 2 hr at 15°. After incubation, the cells were centrifuged at 100 g for 5 min at 15° and were washed with L-15 + 5% FCS + P/S + gentamicin (50 µg/ml) to remove the supernatant containing extracellular bacteria. This step was repeated three times. Using P/S and gentamicin inhibits the replication of any bacteria that are released from lysed cells during the course of the incubation.2 Following careful resuspension the infected macrophages were divided into aliquots and sampled immediately (2 hr) or incubated at 15° for 1 day or 5 days. Uninfected macrophages were used as a control.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from R. salmoninarum-infected macrophages using the method described by Cook and Lynch.27 To obtain total RNA from trout muscle or pronephros, tissues were homogenized in RNAzol B (Biogenesis, Poole, UK) and extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA derived from these procedures was treated with DNaseI (Amplification Grade; Life Technologies). The purity and quantity of RNA was determined by measuring the optical density at 260/280 nm. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed by using the Superscript II RT-PCR kit (Life Technologies) as described previously.28 Each 50 µl reverse transcription reaction contained 5 µg total RNA and 300 ng random primers. The amount of amplified PCR products was therefore relative to a constant amount of starting RNA. Control reactions, from which either reverse transcriptase or RNA was omitted, were run in parallel.

Amplification was performed in a thermal cycler (MWG Biotech Ltd, Milton Keynes, UK) using primers designed as previously described26 (Tables 1 and 2). Reaction mixtures (50 µl) contained 1 U Taq polymerase, reaction buffer containing 1·5 mm MgCl2 (Roche, Lewes, UK), 24 pmol of each primer (Sigma-Genosys, Cambridge, UK), 0·2 mm dNTPs and 1 µl cDNA template. Reactions were overlaid with mineral oil, denatured at 96° for 1 min, and subjected to 30, 34, 35, or 40 cycles as follows: 96° for 30 seconds, 65° for 30 seconds, 72° for 90 seconds and, finally, 72° for 210 seconds. The amplification products were visualized under UV light on 1% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. To ensure that amplification products were within the linear range of the PCR cycle, for each primer a series of amplification cycles were carried out. Cycle times for each gene were selected on the basis of these data (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Primers used to amplify specific Renibacterium salmoninarum genes (35 PCR cycles).

| Primer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Size of PCR product (bp) | Designation | Sequence (5′–3′) |

| msa | 487 | Rs57 + 127 | TCGCAAGGTGAAGGGAATTCTTCC |

| Rs57 − 611 | GGTTTGTCTCCAAAGGAGACTTGC | ||

| hly | 542 | RsMP + 338 | ATCGGCTCAGACTAGCGCCATAAT |

| RsMP − 877 | GCTTCAAGATCGATGACCTTCGAG | ||

| rsh | 572 | RsH + 231 | TCCGGTCATCATGCTTTCTTCGCT |

| RsH − 800 | ATTGCCACCAAGCTGAAGTACCTG | ||

| lysB | 258 | 35K + 193 | ATGTAGCCAAGAATGTGGGCGATG |

| 35K − 448 | AGGCTATCTCCTTCAGCAACAGTC | ||

| grp | 330 | 3C + 1950 | AGTGTTGCGTCGAGCAATCGGCTA |

| 3C − 2277 | AGCATGAAGAACTGCTGCGGGAAG | ||

Table 2. Primers used to amplify rainbow trout cytokine and cytokine-related genes.

| Primer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene (PCR cycles) | Size of PCR product (bp) | Designation | Sequence (5′–3′) |

| GAPDH (30) | 454 | GAP + 328 | TTGAATCCACCGGAGTCTTCCTCA |

| GAP − 779 | TAGTTCCACCACTGATACGTCAGC | ||

| NKEF (30) | 517 | NKEF + 68 | ACGGCCAGTTCAAAGACATCAGCA |

| NKEF − 582 | GAAGTCTTTGCTCTTCTGCACGTC | ||

| IL-1β (34) | 345 | IL1 + 132 | ACACCTCTGAAAGTGCAGCATGGA |

| IL1 − 475 | TGCAGCTCCATAGCCTCATTCATC | ||

| IL-1R (34) | 582 | IL1R + 89 | CTCCGCTACCTATGATAGATGGCT |

| IL1R − 668 | ACTCTAAGCTGACAGGTGTAGAGG | ||

| Cox-1 (30) | 535 | COX1 + 448 | TATCCCTGAGTTCTGGACGAGAGT |

| COX1 − 980 | TAAGAAGCCGGAGGTTCAGTTGAC | ||

| Cox-2 (34) | 599 | COX2 + 188 | TATGAGTGCGACTGCACAAGGACT |

| COX2 − 784 | CAGTTTGCCATCCTTGAACAGCCT | ||

| TNF-α (34) | 602 | TNFA + 43 | CCTGTGTACAACACAACGGTGACA |

| TNFA − 642 | GAACACTGCACCAAGGTAAACTGC | ||

| TGF-β (30) | 484 | TGF + 42 | AGACTCTGAATGAGTGGCTGCAAG |

| TGF − 523 | CTCCAAGACCTGTGGAACACAGCA | ||

| iNOS (40) | 442 | INOS + 221 | TGAAGCACTTGGAGACAGAGTTCC |

| INOS − 660 | CATTACCACAACCAGAAGGCTCTC | ||

| Mx1 (30) | 425 | MX1 + 1684 | GACGAAGACCAACCCTTAACTGAG |

| MX1 − 2106 | AACCCCACTGAAACACACCTGTAG | ||

| Mx2 (34) | 399 | MX2 + 1656 | TCTGTAAGGAGTACTGTCAATGGC |

| MX2 − 2052 | ATCTACCCCAAACCTCAATGCCTA | ||

| Mx3 (30) | 469 | MX3 + 1624 | AGGAAGACGACCGACCCTTACCAA |

| MX3 − 2090 | CTTTCAAGTGATATCCTCTGGGTC | ||

| MHC I (30) | 287 | MHCI + 713 | ATGGTGTTCTGGCAGAAAGACGGA |

| MHCI − 997 | GAGAGCTATCACCCCTCCAATGAT | ||

| MHC II (30) | 408 | MH + 4021 | TCAGATTCAACAGCACTGTGG |

| MH − 577 | CAGGAGATCTTCTCTCCAGACTTG | ||

| CXC-R4 (30) | 434 | CXC + 287 | TCCTATTCGTCCTCACGCTACCTT |

| CXC − 718 | GCTTGGCAATGATGATGCAGTAGC | ||

| CC-R7 (30) | 491 | CCR + 224 | GTATGAACCACCTCTCTACTGGTC |

| CCR − 712 | TTGGTGCGGTTGTTCTGGTTACTC | ||

| TCRβ (30) | 411 | TCRB + 48 | CTCCGCTAAGAAGTGTGAAGACAG |

| TCRB − 456 | CAGGCCATAGAAGGTACTCTTAGC | ||

| CD8α (30) | 290 | CD8 + 327 | AAAGGCTCGAGATAGTGGCGTCTA |

| CD8 − 614 | CGGTTGCAATGGCATACAGTGATG | ||

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NKEF, natural killer cell enhancing factor; IL-1 β interleukin-1 β IL-1R, interleukin-1 receptor type II; Cox-1, cyclo-oxygenase constitutive isoform; Cox-2, cyclo-oxygenase inducible isoform; TNF-α tumour necrosis factor-α TGF-β transforming growth factor-β iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; Mx1, Mx2 and Mx3, interferon-inducible genes of fish and mammals; MHC I, major histocompatibility complex class I; MHC II, major histocompatibility complex class II; CXC-R4, CXC chemokine receptor type 4; CC-R7, CC chemokine receptor type 7; TCR β T-cell receptor βchain; CD8α, α-chain of the T-cell receptor co-receptor molecule.

Vectors and DNA constructs

The expression vector pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) was used in constructing plasmids containing genes msa (pMsa2), hly (pHly1), rsh (pRsh3), lysB (pLysB21), and grp (pGrp22) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids for DNA vaccination were constructed to include the full length of the gene including the ATG start codon and the stop codon inserted downstream of the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. Two additional plasmids expressing lysB (pLysB13) or grp (pGrp11) were constructed to provide a translational fusion of the proteins with His and V5 epitopes encoded by the vector and located at the C terminus. This was necessary to enable the immunological detection of lysB and grp gene products within the tissues of fish that were injected with the plasmids expressing these genes because at the time there was no specific means of detecting the proteins. The nucleotide sequences that were cloned into pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO were generated by PCR, under the conditions outlined above, from the genomic DNA of R. salmoninarum 980036-150. Where possible, a Kozak translation initiation sequence was included to enhance expression as recommended by the manufacturer. The primers that were used for the amplification of the genes were as follows: pMsa2 sense, AGATGGCTTTCGCTGGTGCGCTGT; antisense, TGCCGTCTTACCTGAATCAACACC; pHly1 sense, GGATTATGGAAAAGTACTACGCCG; antisense, GGCGCTTTCTAGCTATCTCAGGTT; pRsh3 sense, CGATGAGGATCGACCATGACATCC; antisense, CTTGGTAATAGCCAGCGATTGCAG; pLysB21 sense, GTTATGGGACTTTTCGATGACATC; antisense, AACCTACGGAAGCGTCAAAACCTG; pGrp22 sense, ACCGTGGCGACGGCTAGTGTTGCG; antisense, CTAACCAACTGAGCATGAAGAACTGCT; pLysB13 sense, GTTATGGGACTTTTCGATGACATC; antisense, AAGCGTCAAAACCTGGCCCGGGAA; pGrp11 sense, ACCGTGGCGACGGCTAGTGTTGCG; antisense, ACCAACTGAGCATGAAGAACTGCT. All plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli TOP 10, and positive colonies were characterized by restriction enzyme analysis. Plasmid DNA was amplified in E. coli TOP 10, purified with the Quantum plasmid purification kit (BioRad, Hemel Hempstead, UK), and stored at −20° until use.

Antibodies and immunohistochemistry

Rat antibodies specific for R. salmoninarum proteins p57, Hly and Rsh have been previously described;20,29,30 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) specific for His (C terminus) and V5 epitopes (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) were used as pure antibodies or as direct conjugates to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 FITC and rabbit anti-rat IgG FITC (Sigma) were used as secondary antibodies where necessary. Muscle tissue was obtained from 115-g rainbow trout that had been injected intramuscularly in the flank between the lateral line and the leading edge of the dorsal fin with 20 µg of a DNA vaccine construct in a 10-μl volume. After 1 week, blocks of muscle were excised from the tissues surrounding the injection site, frozen at −80°, and 10-μm sections were cut on a cryostat, dried overnight at room temperature, fixed for 5 min in paraformaldehyde vapour, and rehydrated and washed three times with PBS. Tissue sections were incubated with primary antibody diluted with PBS (1 : 50, 1 : 100, 1 : 200) for 1 hr at room temperature, washed three times with PBS, and incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody diluted with PBS (1 : 320) for 1 hr at room temperature. Control muscle tissues from unvaccinated fish were treated in the same way. Preparations were viewed using a fluorescence microscope (AHBT Vanox, Olympus) fitted with the appropriate filters for FITC (excitation filter BP490, dichroic mirror DM500, barrier filter O515) and digital images were captured for each of the vaccinated and control tissues.

Injection of rainbow trout with DNA vaccine constructs

Separate groups (n = 12) of 30–40-g rainbow trout maintained at 16° were injected with individual DNA vaccine constructs. The fish received 20 µg of plasmid DNA in a 10-μl volume injected intramuscularly in the flank between the lateral line and the leading edge of the dorsal fin. Previous work has shown that higher levels of expression are obtained when small volumes of DNA are injected.31 Two control groups (n = 12) were either injected with pcDNA3.1/V5-His, which did not contain any of the inserts, or were unvaccinated. Fish were sampled at 1, 3, 5 and 7 weeks after injection and the pronephros was removed for RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis. Some samples were also processed 12 weeks after injection.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis

PCR products from reactions performed with each primer set were sequenced by MWG-Biotech Ltd (Milton Keynes, UK). The correct identity and orientation of the inserts in all plasmids was confirmed by DNA sequencing of both strands (MWG Biotech Ltd). The identities of the sequences were confirmed by pairwise alignments with the target sequences found on the GenBank database using the GeneBee multiple alignment program, which can be found at http://www.genebee.msu.su/services/malign_reduced.html. The nucleotide sequences reported here have been deposited in GenBank (accession nos AF428065–AF428067; AF178994, AF428071, AF428072).

Results

Infection of phagocytes with R. salmoninarum

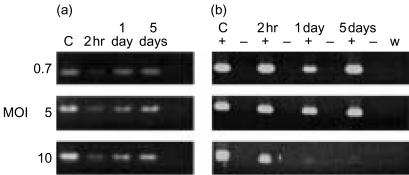

Initial studies were designed to investigate the expression of five R. salmoninarum genes following the infection of macrophages with increasing MOI. The viability and morphology of the macrophages was assessed by microscopy and trypan blue exclusion. Using RT-PCR the pattern of expression of the R. salmoninarum genes was very similar at each MOI of 0·7, 5 and 10 although the strength of the signal was substantially reduced at MOI=0·7 (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, RT-PCR amplification of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) showed that at MOI=10 the viability of infected macrophages was adversely affected after 1 day (Fig. 1b). Therefore, we used an infectious dose of MOI=5 in the subsequent experiments because it resulted in clearly detectable expression of R. salmoninarum genes without inducing cell death to the extent that GAPDH expression by the macrophages was obviously affected.

Figure 1.

Effect of increasing MOI on the expression of (a) Renibacterium salmoninarum gene hly and (b)GAPDH of trout macrophages. Trout macrophages were infected with R. salmoninarum and incubated for 2 hr, 1 day and 5 days at 15°. Total RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed to cDNA and amplified with specific primers by PCR. Data are representative of one experiment which was repeated three times. C, control samples taken immediately prior to infection of either (a) R. salmoninarum or (b) trout macrophage cDNA; +, reactions containing reverse transcriptase; −, reactions without reverse transcriptase; w, reactions with water substituted for RNA template.

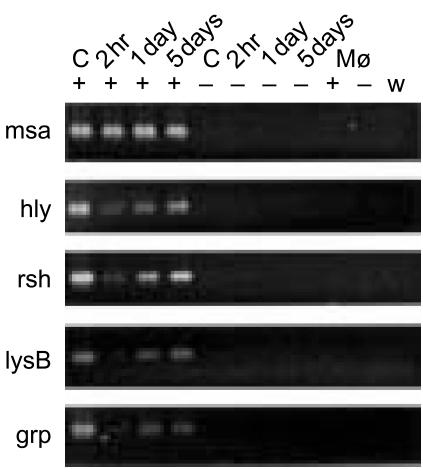

Expression of R. salmoninarum genes during macrophage infection

To analyse whether the expression of R. salmoninarum genes that may have a role in pathogenicity is altered during the early phases of phagocytosis, rainbow trout macrophages were infected with live R. salmoninarum and incubated for 2 hr, 1 day and 5 days. Antibiotics were added to the culture medium in order to inhibit the growth of any bacteria that were released from lysed macrophages.2 A previous comprehensive study showed that under these conditions R. salmoninarum is rapidly phagocytosed by macrophages and escapes from the phagosome into the cytoplasm in 72·5% of infected cells within 6·5 hr of infection.2 Total RNA was extracted from the samples, treated with DNaseI, reverse transcribed to cDNA, and amplified in PCR reactions using primers specific to genes msa, hly, rsh, lysB and grp (Table 1). The patterns of expression were compared with those obtained using control samples including RNA that had been extracted from R. salmoninarum immediately prior to infection and also from uninfected macrophages that were sampled after 2 hr or 5 days.

Broadly, two patterns of R. salmoninarum gene expression were evident. Firstly, the expression of gene msa was constitutive and unaffected over the time–course. In contrast, the expression of genes hly, rsh, lysB and grp was substantially reduced after 2 hr exposure to macrophages and over the course of 5 days the expression of these genes gradually increased but did not return to the levels that were present immediately prior to infection (Fig. 2). The experiment was repeated three times with the same result and DNA sequencing confirmed the identity of the PCR products. These findings are in line with previous reports that the expression of genes msa, hly and rsh was detectable at the protein level inside cultured epithelial cells that were infected with R. salmoninarum.22 Additionally, this work shows that at the transcriptional level the expression of hly and rsh, but not msa, is sensitive to the conditions that are present within macrophages during the early stages of phagocytosis.

Figure 2.

Expression of Renibacterium salmoninarum genes msa, hly, rsh, lysB and grp following infection of trout macrophages with R. salmoninarum using MOI=5. The same result was obtained from three separate experiments. C, control samples of R. salmoninarum cDNA taken immediately prior to infection; Mø, cDNA from uninfected macrophages; +, reactions containing reverse transcriptase; −, reactions without reverse transcriptase; w, reactions with water substituted for RNA template.

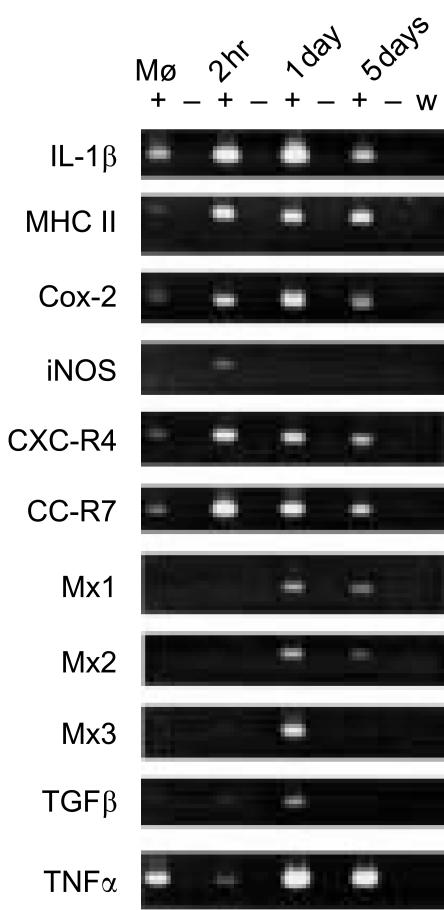

Cytokine and cytokine-related gene expression by R. salmoninarum-infected macrophages

The kinetics and patterns of expression of rainbow trout cytokine and cytokine-related genes by R. salmoninarum-infected macrophages were examined by RT-PCR using 18 sets of primers complementary to as many of the relevant sequences and isoforms as possible that were available on the GenBank database (Table 2). The increased expression of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II, the inducible isoform of cyclo-oxygenase (Cox-2), iNOS and the chemokine receptors CXC-R4 and CC-R7 was apparent 2 hr after infection and this is largely consistent with a rapid inflammatory response (Fig. 3). Mx1, Mx2, Mx3 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) were up-regulated after 1 day, when IL-1β and Cox-2 were most strongly expressed. The Mx genes in fish respond to virus and interferon (IFN)-like factors and have been associated with inflammatory responses.32–34 After 5 days the expression of these genes, with the exception of MHC II that remained at a consistent level, appeared to be reduced in comparison with the peak at 2 hr or 1 day and, in some cases, had returned to a level approaching that in the control macrophages. Interestingly, the expression of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was almost abolished 2 hr after infection but this effect was reversed after 1 day and remained higher at day 5, perhaps in response to the strong inflammatory signals from other components. The expression of MHC I, the constitutive isoform of cyclo-oxygenase (Cox-1), IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) and natural killer cell-enhancing factor (NKEF) remained more or less unchanged throughout the time–course (data not shown). DNA sequencing and sequence analysis of the PCR products confirmed the identity of the amplicons.

Figure 3.

Expression of cytokine and cytokine-related genes following infection of trout macrophages with Renibacterium salmoninarum. Mø, cDNA from uninfected trout macrophages. +, reactions containing reverse transcriptase; −, reactions without reverse transcriptase; w, reactions with water substituted for RNA template. The experiments were repeated three times with the same result.

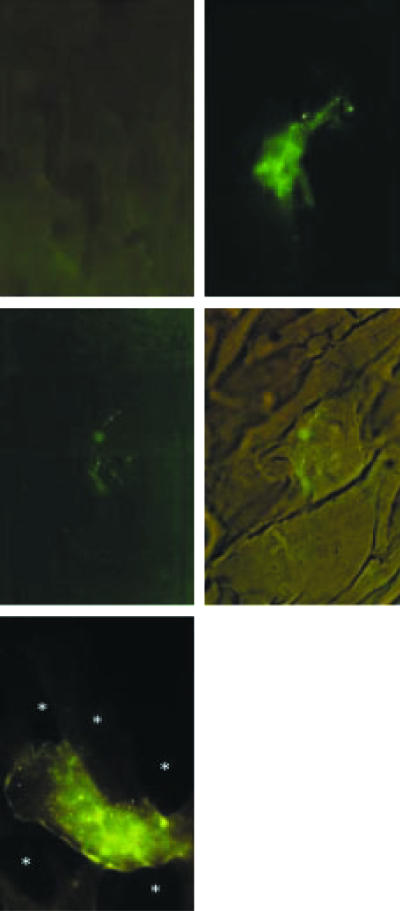

Expression of DNA constructs in fish muscle tissue

To verify the expression of DNA vaccine constructs containing one copy of the full length of msa, hly, rsh, lysB, or grp in fish tissues, we injected rainbow trout intramuscularly with each construct. After 1 week, RNA was extracted and immunohistochemistry was performed using muscle tissue that had been excised from the injection site. The correct sequence and orientation of all of the R. salmoninarum genes encoded by each of the DNA vaccine constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing and each gene was expressed at the RNA level (data not shown). Furthermore, muscle sections that had been incubated with antibodies for the detection of epitopes present on p57, Hly and Rsh or for the detection of His and V5 C-terminal epitope tags attached to LysB and Grp revealed that the RNA was translated as protein (Fig. 4). Control tissues (Fig. 4a) were treated in exactly the same way as tissues from DNA-vaccinated fish and showed no evidence of the punctate staining that was observed in the immunized animals. Most of the cells that were stained were myocytes although the occasional dendritic-like cell was observed (Fig. 4b). The staining was mostly restricted to myofibres contained within discrete blocks of muscle (Fig. 4c, d) although there was also a diffuse appearance and tissue vacuolation in the staining of the myocytes of fish expressing msa and hly that may have arisen as a consequence of the proteolytic activity of these proteins (Fig. 4e). The diffuse staining of p57 and Hly has also been observed in R. salmoninarum-infected Epithelioma papillosum cyprini (EPC) cells cultured in vitro.22

Figure 4.

Expression of DNA vaccine constructs in the tissues of rainbow trout injected with 20 µg plasmid DNA. After 7 days the muscle was fixed and observed using immunofluorescence. (a) Unstained muscle tissue from unimmunized trout; (b) a dendritic-like cell from the muscle of a fish injected with pLysB13; (c) muscle from a fish injected with pGrp11; (d) the same tissue as in (c) but with bright field illumination and fluorescence to show the structure of the muscle tissues and the localization of the staining within an individual myotome; (e) muscle from a fish injected with pHly1 showing the diffuse staining and vacuolation (*) of the surrounding tissue which was similar to the muscle from fish injected with pMsa2. All figures are × 400 by original magnification.

Host cytokine and cytokine-related gene responses to R. salmoninarum proteins expressed in vivo

To investigate the responses of pronephric leucocytes to R. salmoninarum genes that are expressed inside infected macrophages we injected groups of rainbow trout intramuscularly with individual DNA vaccine constructs expressing one copy of the full length of msa, hly, rsh, lysB, or grp. The responses were compared with those of control fish that had been either injected with the plasmid vector without any insert DNA or were unvaccinated. Pronephros was removed at intervals after injection and prepared for RT-PCR. Previous studies of DNA vaccination of rainbow trout have demonstrated that constructs expressing luciferase under the control of the CMV promoter show peak activity at 7 days post-injection, which is progressively reduced to about 10–15% of maximum activity 5–6 weeks post-injection. Therefore, we reasoned that the immediate and direct cytokine and cytokine-related responses would occur within the first 2 months after vaccination. Compared with unvaccinated control fish, the head kidney leucocytes of DNA-vaccinated fish sampled 1 week post-injection showed an increased expression of NKEF, TGF-β, Cox-1, Cox-2, Mx2, T-cell receptor β (TCRβ), MHC II, Mx1 and IL-1β. Because this effect also occurred in fish that had been injected with the plasmid vector alone this probably represented a general non-specific response to the presence of immunostimulatory CpG motifs within the vector.35

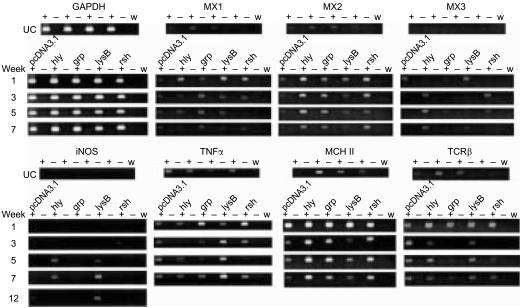

Following the acute reaction that was observed in week 1 and in comparison to control fish, the responses of fish that had been injected with either pHly1, pRsh3, or pGrp22 were remarkably similar and showed increased expression of Mx2 and MHC II at each sampling time (Fig. 5). Furthermore, in these fish the expression of TNF-α was reduced in weeks 3 and 5 before returning to control levels by week 7. Mx3 expression was low, except in fish injected with pHly1 and pRsh3, and iNOS expression was clearly demonstrated, at weeks 5 and 7 in fish that had been injected with either pHly1 or pLysB21, and, in the case of pLysB21, this effect persisted until week 12. The latter also exhibited increased expression of TNF-α. Mx1 was slightly and transiently stimulated by pHly1 and pRsh3, but pGrp22 and pLysB21 stimulated expression throughout weeks 1, 3 and 5. Expression of TCRβ was reduced in fish injected with pGrp22 and pRsh3. Compared with unvaccinated controls, the expression of the other genes that were examined was either mostly unchanged between groups and/or over time, e.g. NKEF, TGF-β, CD8α, Cox-1, Cox-2, MHC I, CXC-R4, and CC-R7, or no clear pattern of response was evident, e.g. IL-1β and IL-1R (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Expression of cytokine and cytokine-related genes in the pronephros of rainbow trout at time-points following the intramuscular injection of DNA vaccine constructs expressing Renibacterium salmoninarum genes hly, grp, lysB, or rsh or with the plasmid vector, pcDNA3.1, alone. Data were gathered from a single experiment and only those genes demonstrating a consistent pattern of variation between constructs and/or over time are shown. The reactions were repeated to confirm reproducibility. GAPDH expression shows the consistency of the RT-PCR for each sampling occasion. UC, samples taken from unimmunized control fish corresponding to weeks 1, 3, 5 and 7 from left to right. +, reactions containing reverse transcriptase; −, reactions without reverse transcriptase; w, reactions with water substituted for RNA template.

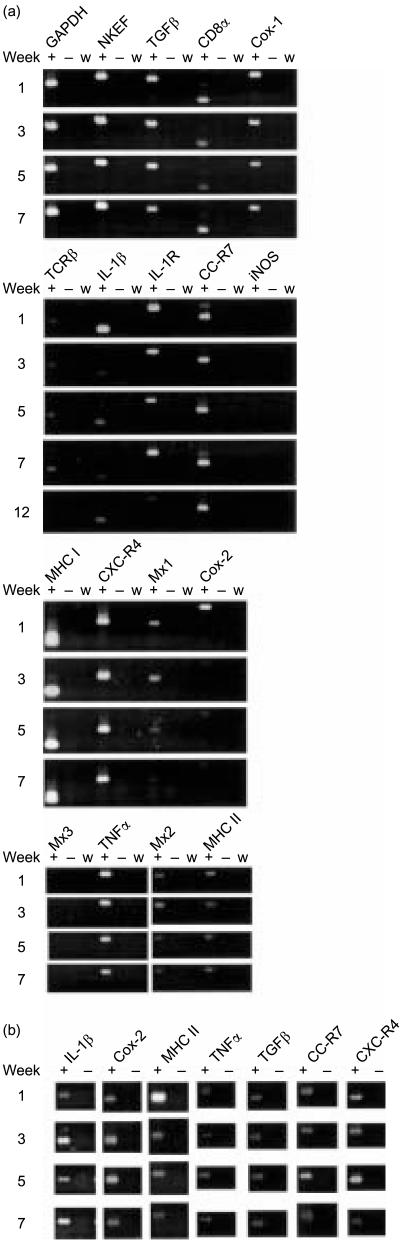

In contrast, the pattern of responses to pMsa2 expressing p57 protein showed, compared with fish injected with pcDNA3.1 alone, that in weeks 3, 5 and 7 post-injection the expression of IL-1β and Cox-2 was almost abolished while that of MHC II was reduced and, in the case of IL-1β, it remained so in fish examined after 12 weeks. Interestingly, pMsa2 is a strong stimulus for TNF-α, TGF-β and the chemokine receptors (Fig. 6). The PCR products from reactions using each set of primers were sequenced and in every case matched the target gene sequences.

Figure 6.

(a) Expression of cytokine and cytokine-related genes in the pronephros of rainbow trout following the intramuscular injection of pMsa2. For comparative purposes the expression of IL-1β, Cox-2, MHC II, TNF-α, TGF-β, CXC-R4 and CC-R7 in fish injected with pcDNA3.1 is presented in (b). +, reactions containing reverse transcriptase; −, reactions without reverse transcriptase; w, reactions with water substituted for RNA template.

This work shows that the immunosuppressive function of p57 acts to reduce the transcription of IL-1β and, probably as a consequence, Cox-2 and MHC II. IL-1β is a pro-inflammatory cytokine and, like Cox-2, is expressed by macrophages in response to inflammatory signals, such as bacterial infection.36,37 Interestingly, the expression of MHC II was increased by pHly1, pRsh3 and pGrp22 but this was not accompanied by the increased expression of IL-1β, Cox-2, TNF-α, or Mx1, which responds to type I IFN stimuli.34

Discussion

This study reveals some of the events that surround the early interaction between R. salmoninarum and host macrophages. In particular, the rapid abrogation of the expression of TNF-α and paradoxical concomitant stimulation of iNOS transcription after 2 hr, when most of the bacteria are contained within the phagocyte vacuole.2 Concurrently, the expression of two haemolysin genes by R. salmoninarum, hly and rsh, is almost abolished while that of msa, which encodes the major soluble antigen p57, is unaffected. This effect on TNF-α was reversed after 1 day, when the expression of other inflammatory indicators was highest, and at a time when R. salmoninarum has been shown to reside within the cytoplasm of host macrophages.2 Renibacterium salmoninarum is known to elicit a respiratory burst during early phagocytosis, and although the enhancement of this activity with TNF-α, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or IFN-γ analogue, and the presence of H2O2 but not has been correlated with growth inhibition, it is nevertheless insufficient to completely eliminate the pathogen.12,13,38 Renibacterium salmoninarum may avoid direct exposure to ROI by escaping from the phagosome2 and perhaps also by utilizing the CR1 receptor for entry.39 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that R. salmoninarum infections induce iNOS transcription in vivo, and in vitro studies suggest that resistance to NO, but not to peroxynitrite, may provide an additional means by which R. salmoninarum survives macrophage killing.14,15

How R. salmoninarum manages to achieve this resistance to macrophage killing mechanisms is unknown but recent studies indicate that it is the sequence of ROI production followed by a prolonged reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI) phase, rather than the predominance of a single antimicrobial mechanism, that is important in the killing of intracellular organisms by macrophages.40,41 The importance of TNF-α to these processes is well known in mammals where TNF-α synergizes with other mediators to up-regulate ROI and RNI.6 Similar functions have also been shown to occur in fish13,42 and the recent cloning of the trout TNF-α gene will greatly facilitate further studies of the potency of this cytokine in controlling R. salmoninarum growth.43 A recent study using TNF-α, iNOS and IFN-γ knockout mice showed that RNI are important for macrophage killing of mycobacteria, and while TNF-α can control mycobacterial growth in the absence of iNOS, the enzymatic function of iNOS rather than its expression requires the presence of TNF-α to kill mycobacteria.44 Clearly, there are two TNF-α-dependent killing pathways that are present, either iNOS-dependent (RNI), or iNOS-independent, most likely ROI, and each has a role to play in the control of intracellular bacteria. Therefore, the reduction of TNF-α expression during the early phases of phagocytosis may, despite the increased expression of iNOS, affect each of these pathways and facilitate the survival of R. salmoninarum. On the other hand, if the higher levels of TNF-α that were evident in macrophages after 1 and 5 days infection persisted, then this cytokine may be implicated in the pathology of BKD and the host-mediated destruction of kidney tissues. In this respect, the induction of TNF-α may exacerbate the immunopathology of tuberculosis6 and may directly support the survival of intracellular pathogens.45 Although in vitro experimentation may not accurately reproduce in vivo conditions, the nature of many chronic infections, such as BKD, renders such studies problematical.

We used the expression of specific components of R. salmoninarum within the host in order to determine the nature of the immune interaction and their likely contribution to the progression of BKD. The major soluble antigen of R. salmoninarum, p57, is produced in substantial quantities in the tissues of infected fish.17 This feature of chronic infections has been used for the diagnosis of asymptomatic carriers.10 We have shown that the expression of msa in rainbow trout reduces the expression of IL-1β, Cox-2 and MHC II compared with fish injected with plasmid vector DNA even though the expression of other inflammatory indicators, including TNF-α, TGF-β and the chemokine receptors CXC-R4 and CC-R7, was apparently stimulated. Because of this, msa is an unlikely cause of the interference with TNF-α that was observed during the early phases of macrophage infection, even though R. salmoninarum expresses it constitutively during this process. In fact our results suggest that msa may have a role in the chronic stimulation of TNF-α, which could be expected to assist the chronic inflammatory pathology of BKD. Our work explains the molecular basis to previous studies showing that p57 suppresses antibody responses, the macrophage respiratory burst17,18 and renders immunized animals more susceptible to BKD.1 Furthermore, our results show that the effects of p57 occur at a basic level by suppressing IL-1β and may therefore play a pivotal role in the long term suppression of a variety of other immune functions. The long-term suppression of IL-1β could be expected to have a major impact on cytokine and eicosanoid production, phagocyte function, and lymphocyte proliferation and activation including T-cell-dependent antibody production.37,46 The chronic reduction in the expression of MHC II may skew the T-cell responses toward MHC I-dependent pathways and greatly exacerbate the pathology of BKD through the preferential induction of cytolytic T-cell responses.47

In contrast to the suppressive nature of msa we have shown that constructs expressing the haemolysins hly and rsh, and a putative growth regulatory protein, grp, are capable of inducing MHC II expression. Furthermore, hly and lysB, a putative holin, strongly induce iNOS expression in the pronephros of rainbow trout. Because lysB, but not hly, rsh, or grp, was shown to increase the expression of TNF-α, the pathways for the induction of this effect may differ. Both grp and rsh decreased the expression of TCRβ and also failed to induce detectable iNOS. Therefore, lysB induces iNOS and TNF-α expression without stimulating MHC II, Mx2, or Mx3, while hly uses a TNF-α-independent mechanism involving MHC II and also Mx2 and Mx3. A recent series of studies of the immunization of rainbow trout and Atlantic salmon against BKD reported up to 60% reduction in mortality using the metalloprotease encoded by hly, 14–22% reduction in mortality using the haemolysin protein encoded by rsh, and increased mortality among fish immunized with p57.24 We suggest that the effective induction of MHC II and iNOS may have a role in this outcome. The two proteins, Hly and Rsh, elicit a weak antibody response in immunized rainbow trout24 and it is possible to speculate that T helper type 1 CD4+ T-cell-like responses may be involved in resistance to BKD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Hocking and Angela Watson for their technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the European Union EU-FAIR programme, no. CT98-4003.

References

- 1.Evelyn TPT. Bacterial kidney disease-BKD. In: Inglis V, Roberts RJ, Bromage NR, editors. Bacterial Diseases of Fish. Oxford: Blackwell; 1993. pp. 177–95. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutenberger SK, Duimstra JR, Rohovec JS, Fryer JL. Intracellular survival of Renibacterium salmoninarum in trout mononuclear phagocytes. Dis Aquat Org. 1997;28:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evelyn TPT, Prosperi-Porta L, Ketcheson JE. Further evidence for the presence of Renibacterium salmoninarum in salmonid eggs and for the failure of povidone-iodine to reduce the intra-ovum infection in water-hardened eggs. J Fish Dis. 1984;7:173–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balfry SK, Albright LJ, Evelyn TPT. Horizontal transfer of Renibacterium salmoninarum among farmed salmonids via the fecal-oral route. Dis Aquat Org. 1996;25:63–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grayson TH, Atienzar FA, Alexander SM, Cooper LF, Gilpin ML. Molecular diversity of Renibacterium salmoninarum isolates determined by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:435–8. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.435-438.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown LL, Ricks R, Evelyn TPT, Albright LJ. Experimental intra-ovum infection of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) eggs with Renibacterium salmoninarum using a microinjection technique. Dis Aquat Org. 1990;8:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munro ALS, Bruno DW. Vaccination against bacterial kidney disease. In: Ellis AE, editor. Fish Vaccination. London: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 124–35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starliper CE, Teska JD. Relevance of Renibacterium salmoninarum in an asymptomatic carrier population of brook trout, Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchell) J Fish Dis. 1995;18:383–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiens GD, Kaattari SL. Bacterial kidney disease (Renibacterium salmoninarum) In: Woo PTK, Bruno DW, editors. Fish Diseases and Disorders: Viral, Bacterial and Fungal Infections. Vol. 3. New York: CABI Publishing; 1999. pp. 269–301. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandin I, Rivas C, Santos Y, Secombes CJ, Barja JL, Ellis AE. Effect of serum factors on the survival of Renibacterium salmoninarum within rainbow trout macrophages. Dis Aquat Org. 1995;23:221–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardie LJ, Ellis AE, Secombes CJ. In vitro activation of rainbow trout macrophages stimulates inhibition of Renibacterium salmoninarum growth concomitant with augmented generation of respiratory burst products. Dis Aquat Org. 1996;25:175–83. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campos-Pérez JJ, Ellis AE, Secombes CJ. Investigation of factors influencing the ability of Renibacterium salmoninarum to stimulate rainbow trout macrophage respiratory burst activity. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1997;7:555–66. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campos-Pérez JJ, Ward M, Grabowski PS, Ellis AE, Secombes CJ. The gills are an important site of iNOS expression in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss after challenge with the Gram-positive pathogen Renibacterium salmoninarum. Immunology. 2000;99:153–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00914.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campos-Pérez JJ, Ellis AE, Secombes CJ. Toxicity of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite to bacterial pathogens of fish. Dis Aquat Org. 2000;43:109–15. doi: 10.3354/dao043109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Farrell CL, Strom MS. Differential expression of the virulence-associated protein p57 and characterization of its duplicated gene msa in virulent and attenuated strains of Renibacterium salmoninarum. Dis Aquat Org. 2000;38:115–23. doi: 10.3354/dao038115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turaga PSD, Wiens GD, Kaattari SL. Bacterial kidney disease: the potential role of soluble protein antigen (s) J Fish Biol. 1987;31(Suppl. A):191–4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown LL, Iwama GK, Evelyn TPT. The effect of early exposure of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) eggs to the p57 protein of Renibacterium salmoninarum on the development of immunity to the pathogen. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1996;6:149–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piganelli JD, Wiens GD, Zhang JA, Christensen JM, Kaattari SL. Evaluation of a whole cell, p57− vaccine against Renibacterium salmoninarum. Dis Aquat Org. 1999;36:37–44. doi: 10.3354/dao036037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grayson TH, Evenden AJ, Gilpin ML, Martin KL, Munn CB. A gene from Renibacterium salmoninarum encoding a product which shows homology to bacterial zinc-metalloproteases. Microbiology-UK. 1995;141:1331–41. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evenden AJ, Gilpin ML, Munn CB. The cloning and expression of a gene encoding haemolytic activiy from the fish pathogen, Renibacterium salmoninarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:31–4. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90028-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McIntosh D, Flaño E, Grayson TH, Gilpin ML, Austin B, Villena AJ. Production of putative virulence factors by Renibacterium salmoninarum grown in cell culture. Microbiology-UK. 1997;143:3349–56. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-10-3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grayson TH, Gilpin ML, Evenden AJ, Munn CB. Evidence for the immune recognition of two haemolysins of Renibacterium salmoninarum by fish displaying symptoms of bacterial kidney disease (BKD) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2001;11:367–70. doi: 10.1006/fsim.2000.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson KD, Kiernan M, Gilpin ML, Munn CB, Adams A, Richards RH. Link Aquaculture Final Report. Pitlochry, UK: Freshwater Fisheries Laboratory, Faskally; 2001. Development of vaccination methods for the control of bacterial kidney disease in salmonids; pp. 1–20. Project Sal10, CSA 4280/Fc0445. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Secombes CJ. Isolation of salmonid macrophages and analysis of their killing activity. In: Stolen JS, Fletcher TC, Anderson DP, Roberson BS, van Muiswinkel WB, editors. Techniques in Fish Immunology. Vol. 1. Fair Haven: SOS Publications; 1990. pp. 137–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grayson TH, Cooper LF, Atienzar FA, Knowles MR, Gilpin ML. Molecular differentiation of Renibacterium salmoninarum isolates from worldwide locations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:961–8. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.961-968.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook M, Lynch WH. A sensitive nested reverse transcriptase PCR assay to detect viable cells of the fish pathogen Renibacterium salmoninarum in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3042–7. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.7.3042-3047.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grayson TH, Ellis JM, Chen S, Graham RM, Brown RD, Hill CE. Immunohistochemical localisation of α1B-adrenergic receptors in the rat iris. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;293:435–44. doi: 10.1007/s004410051135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grayson TH, Evenden AJ, Gilpin ML, Munn CB. The production of the major soluble antigen of Renibacterium salmoninarum in E. coli K12. Dis Aquat Org. 1995;22:227–31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grayson TH, Evenden AJ, Gilpin ML, Munn CB. Production of a Renibacterium salmoninarum hemolysin fusion protein in E. coli K12. Dis Aquat Org. 1995;22:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heppell J, Lorenzen N, Armstrong NK, Wu T, Lorenzen E, Einer-Jensen K, Schorr J, Davis HL. Development of DNA vaccines for fish: vector design, intramuscular injection and antigen expression using viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus genes as model. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1998;8:271–86. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leong JC, Trobridge GD, Kim CHY, Johnson M, Simon B. Interferon-inducible Mx proteins in fish. Immunol Rev. 1998;166:349–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim CH, Johnson MC, Drennan JD, Simon BE, Thomann E, Leong JC. DNA vaccines encoding viral glycoproteins induce nonspecific immunity and Mx protein synthesis in fish. J Virol. 2000;74:7048–54. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.7048-7054.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collett B, Secombes CJ. The rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Mx1 promoter. Structural and functional characterization. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:1577–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanellos TS, Sylvester ID, Butler VL, Amball AG, Partidos CD, Hamblin AS, Russell PH. Mammalian granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and some CpG motifs have an effect on the immunogenicity of DNA and subunit vaccines in fish. Immunology. 1999;96:507–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00771.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00771.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou J, Neumann NF, Holland JW, Belosevic M, Cunningham C, Secombes CJ, Rowley AF. Fish macrophages express a cyclo-oxygenase-2 homologue after activation. Biochem J. 1999;340:153–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong S, Zou J, Crampe M, Peddie S, Scapigliati G, Bols N, Cunningham C, Secombes CJ. The production and bioactivity of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) recombinant IL-1β. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2001;81:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandin I, Ellis AE, Barja JL, Secombes CJ. Interaction between rainbow trout macrophages and Renibacterium salmoninarum in vitro. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1993;3:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose AS, Levine RP. Complement-mediated opsonisation and phagocytosis of Renibacterium salmoninarum. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1992;2:223–40. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Mastroeni P, Ischiropoulos H, Fang FC. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. I. Effects on microbial killing by activated peritoneal macrophages in vitro. J Exp Med. 2000;192:227–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mastroeni P, Vazquez-Torres A, Fang FC, Xu Y, Khan S, Hormaeche CE, Dougan G. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. II. Effects on microbial proliferation and host survival in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:237–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knight J, Stet RJ, Secombes CJ. Modulation of MHC class II expression in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss macrophages by TNF-α and LPS. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 1998;8:545–3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laing KJ, Wang T, Zou J, et al. Cloning and expression analysis of rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss tumour necrosis factor-α. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:1315–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bekker L-G, Freeman S, Murray PJ, Ryffel B, Kaplan G. TNF-α controls intracellular mycobacterial growth by both inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent and inducible nitric oxide synthase-independent pathways. J Immunol. 2001;166:6728–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engele M, Stößel E, Castiglione K, Schwerdtner N, Wagner M, Bölcskei P, Röllinghoff M, Stenger S. Induction of TNF in human alveolar macrophages as a potential evasion mechanism of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2002;168:1328–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakae S, Asano M, Horai R, Iwakura Y. Interleukin-1β, but not interleukin-1α, is required for T-cell-dependent antibody production. Immunology. 2001;104:402–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dijkstra JM, Fischer U, Sawamoto Y, Ototake M, Nakanishi T. Exogenous antigens and the stimulation of MHC class I restricted cell-mediated cytotoxicity: possible strategies for fish vaccines. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2001;11:437–58. doi: 10.1006/fsim.2001.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]