Abstract

Telomeres are the ends of linear chromosomes. They cannot be fully replicated by standard polymerases and are maintained by the ribonucleoprotein telomerase. Telomeres and telomerase stand at a junction of critical processes underlying chromosome integrity, cancer, and aging and their importance was recognized by the 2009 Nobel Prize to Elizabeth Blackburn, Jack Szostak, and Carol Greider. Where will the field go now? What are the prospects for anti-telomerase agents as drugs? Nearly thirty years after Szostak and Blackburn’s pioneering manuscript on telomere ends, the challenges of discovery remain.

Cells are packed with nucleic acids: chromosomal DNA, mRNA, tRNA, ribosomal RNAs, and the rapidly expanding world of noncoding RNAs. Each nucleic acid has a unique chemical personality and the potential for selective recognition by designed agents to control almost any biological process. The 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine was awarded for the discovery of one of the most elegant nucleic acid systems inside cells – telomeres and telomerase.

The End Replication Problem

The ends of linear chromosomes pose a biological problem. During replication the lagging strand cannot be fully copied by standard polymerases. Olovnikov (Olovnikov, 1971) and Watson (Watson, 1972) first pointed out the implications of this “end replication problem”. Lacking a means to replicate chromosome ends, chromosomes would shorten with each cell doubling, eventually reaching a critical point leading to cell senescence or death.

Hayflick had previously noted that most cultured cells could survive only a limited number of cell divisions and suggested that finite cellular lifespans might explain why physiologic function breaks down as organisms age (Hayflick and Moorhead, 1961). It seemed logical that progressive shortening of chromosome ends might explain the “Hayflick limit”. However, as one question was answered, another one arose: How do organisms survive from one generation to the next? Telomeres are long enough that a given organism might not suffer the catastrophic consequences of chromosome shortening, but eventually the erosion would take its toll and make life impossible for the next generation. Both Olovnikov and Watson pointed out that physiologic systems must exist to maintain telomere length.

Discovery of Telomeres and Telomerase

The experimental answer to the end replication problem began to be revealed when then-postdoctoral fellow Elizabeth Blackburn and Joseph Gall noted that chromosome ends from Tetrahymena thermophila contain the six base sequence TTGGGG repeated 20–70 times (Blackburn and Gall, 1978). Choosing Tetrahymena as a model organism was a key factor in the success of this and subsequent studies because it contains thousands of chromosomes, providing an abundance of telomeric material to analyze.

In 1981 Blackburn, by then an independent investigator, collaborated with Jack Szostak to demonstrate that telomeric function could be transferred from one organism (Tetrahymena) to another (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (Szostak and Blackburn, 1981). This result showed that some feature of the telomeric sequence could preserve function from one organism to the next. Then, in 1985 Blackburn and Carol Greider identified an enzymatic activity capable of extending telomeric sequences (Greider and Blackburn, 1985). Soon thereafter they identified the “terminal transferase” activity as belonging to a ribonucleoprotein with essential RNA and protein components and termed it “telomerase” (Greider and Blackburn, 1987). The RNA component was complementary to the sequence of the telomeric repeat, suggesting that it was acting as a template for repeat addition (Greider and Blackburn, 1989).

Telomerase and Cancer

Soon after these discoveries, telomerase research moved up the evolutionary ladder. Humans also have telomeres and they consist of the repeated sequence TTAGGG (Moyzis et al., 1988). In 1989, Gregg Morin identified telomerase activity in human cells (Morin, 1989). His finding was no small achievement because human cells have far fewer telomeres than Tetrahymena and much lower levels of telomerase. Morin hypothesized that immortal cultured human cell lines would express telomerase, and developed methods for purifying telomerase activity. Like the Tetrahymena enzyme, the human enzyme appeared to be a ribonucleoprotein. In a tantalizing glimpse of the explosion of activity soon to follow, telomerase activity was identified in ovarian tumor cells, but not in isogenic nonmalignant cells, suggesting that telomerase reactivation might be linked to cancer cell proliferation (Counter et al. 1994).

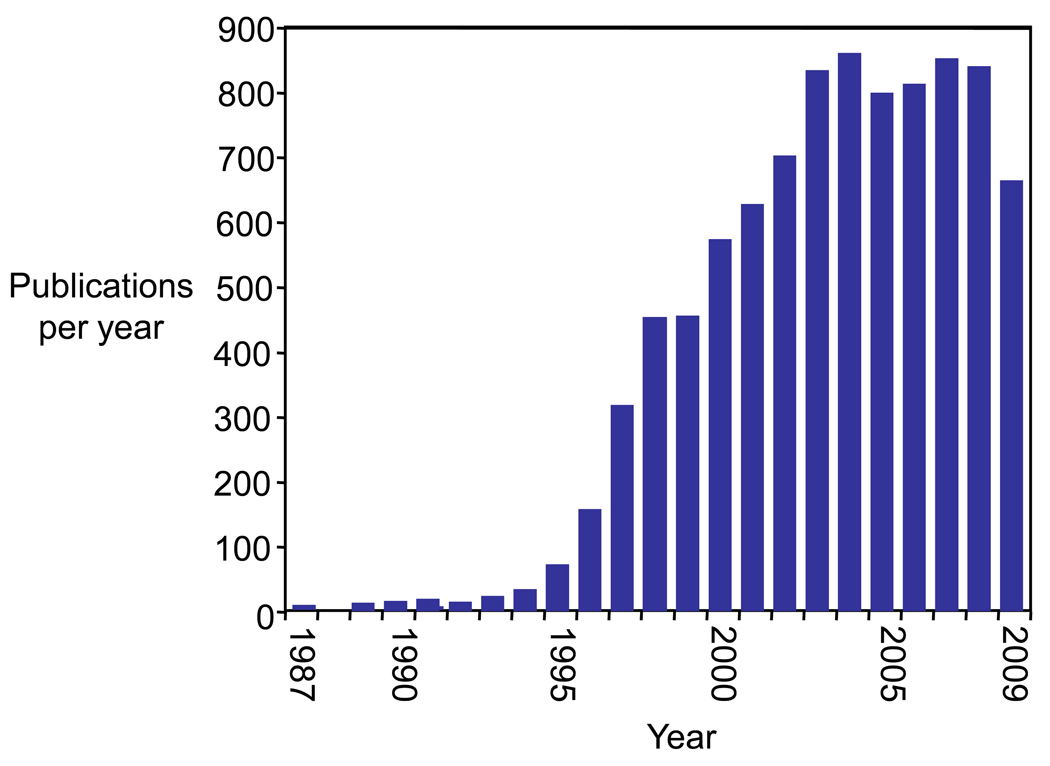

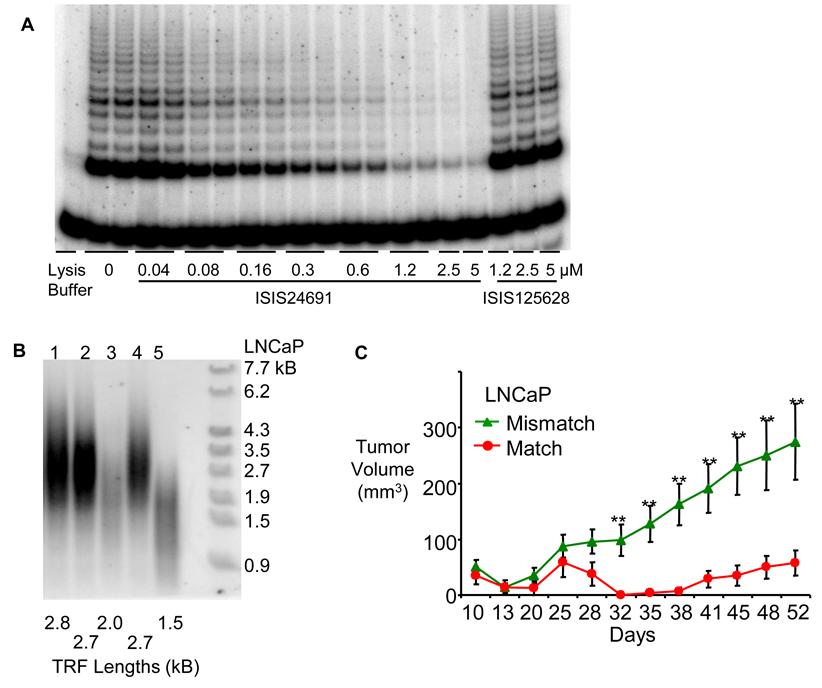

In spite of the obvious importance of telomerase, only a few manuscripts appeared before 1995 (Figure 1). The major reason for this was that levels of human telomerase were so low that much effort was needed to obtain sufficient activity for a handful of assays. Then, in 1994, Shay, Wright and coworkers developed a simple PCR-based assay, the Telomeric Repeat Amplification Protocol (TRAP) that greatly increased the ability to detect telomerase activity (Kim et al., 1994). An example of using TRAP to measure the effectiveness of an inhibitor of telomerase activity is shown in Figure 2a. With TRAP, only a few cells were needed to quantitate activity. It was now possible to ask, on a massive scale, how telomerase activity correlated with the occurrence of human cancer.

Figure 1.

The number of publications in PubMed citing the word “telomerase” and the year in which they were published. Data from 2009 is through October 20, 2009.

Figure 2.

Typical data from assays of telomerase activity demonstrating the effects of inhibiting telomerase. (A) TRAP assay showing inhibition of telomerase activity in C4(2)b cells treated with complementary 2’-methoxyethyl RNA inhibitor ISIS24691 or noncomplementary oligomer ISIS125628 (Canales et al., 2006). Concentration of oligomer is µM and compound was delivered into cells in the absence of transfection reagent. Measurements were in duplicate or quadruplicate. The band at the bottom of the gel is the internal amplification standard used for quantitation. (B) Telomere shortening in LNCaP cells measured by the telomere restriction fragment (TRF) assay. Lane 1; no oligonucleotide added, cells were harvested after three passages. Lane 2; no oligonucleotide added, cells were harvested after 17 passages. Lane 3; match oligonucleotide ISIS 24691 added for 55 days. Lane 4; mismatch oligonucleotide ISIS 125628 added for 55 days. Lane 5; match oligonucleotide ISIS 24691 added for 70 days. Size markers are shown on the right (Chen et al., 2003). Signal is weaker in the lanes showing telomere shortening because shortened telomeres have less DNA available for probe hybridization. (C) Effect of telomerase inhibition on growth of xenograph tumors in mice (Chen et al., 2003). LNCaP cells that had been treated with match or mismatch oligonucleotide for 21 days prior to implantation. P <0.05 (*) and P <0.001 (**).

Shay and colleagues used TRAP to show that telomerase activity could be detected in almost all immortal cell lines and cancer bioposies, but not in mortal cells or normal tissues (Kim et al., 1994). In one of the first examples of the power of telomerase measurement for clinical investigations, TRAP revealed that neuroblastoma samples lacking telomerase activity were associated with a favorable clinical prognosis (Hiyama et al., 2005), demonstrating the potential for telomerase activity to be used as a clinical marker.

The impact of the combination of basic science and technical breakthroughs is readily apparent, with publications mentioning “telomerase” increasing dramatically during the mid-1990’s (Figure 1). Telomerase activity had been observed in greater than 90 % of patient samples from a wide range of different cancers (Shay et al., 2001). Telomerase activity was also observed in proliferative stem cells and germ cells (Mantell and Greider, 1994; Broccolli et al., 1995), consistent with the requirement that these cells maintain chromosome length over many cell divisions or, in the case of germ cells, from one generation of an organism to the next.

Telomerase: a target for inhibitor development

Unlike normal cells, cancerous cells must divide indefinitely to populate a mass sufficiently large and aggressive to threaten a patient. In the absence of a mechanism for fully replicating telomeres, cancer would be self-limiting or would require development of an alternate mechanism for maintaining the integrity of their chromosomes. The observation of telomerase activity in cancerous tissues provided an explanation for how cancer cells can proliferate indefinitely.

Telomerase activity is not always required for cellular immortality. A relatively small number of immortal cell lines have been identified that do not express telomerase activity but maintain telomere length by alternative pathways that depended on recombination (Bryan et al., 1995; Cesare et al., 2008). The existence of these cell lines suggests that some cancer cells might not require telomerase activity, but reactivation of telomerase appears to be much more common.

The belief that telomerase activity was critically important for sustained cancer cell proliferation led to the hypothesis that agents that inhibit telomerase activity might cause the telomeres of cancer cells to erode and limit their proliferation. Successful anti-telomerase drugs would act by a mechanism different from all existing drugs, potentially providing a valuable new tool for treating cancer (Shay and Keith, 2008; Harley 2008).

This hypothesis also predicted that anti-telomerase agents would not kill cells immediately. Instead, they would cause steady telomere shortening until a critical point was reached. In contrast to most existing drugs, where effects are noted soon after administration, the antiproliferative effects of anti-telomerase drugs might occur after weeks or months of continuous treatment. The potential for a lag between initiating treatment and observing efficacy is a central consideration for understanding the challenges of telomerase as an anti-cancer target.

The expected lag between initial dosing and decreased cell proliferation leads to the expectation that telomerase inhibitors would not be useful drugs when used to treat primary tumors because the tumor might become dangerously advanced before drug-induced telomere shortening could reduce cancer cell proliferation. Instead, it is more likely that telomerase inhibitors would be used to prevent cancer recurrence or treat secondary cancers that arise after treatment with existing drugs. It is also unlikely that telomerase inhibitors would be used alone. Instead, they will probably be an adjuvant therapy that compounds the effects of antiproliferative agents that act through other mechanisms.

Biological studies provided support for this hypothesis that inhibiting telomerase would have an antiproliferative effect. Expression of a mutated inactive protein component of telomerase was used to reduce telomerase activity in cells (Hahn et al, 1999; Zhang et al. 1999). As predicted, in the absence of telomerase activity, telomeres grew progressively shorter and cell proliferation was decreased. The effects of telomerase activity were also examined in knock out mice lacking telomerase RNA (mTR−/−). Mice have relatively long telomeres and for six generations few phenotypes were observed (Blasco et al., 1997). Eventually, however, more severe phenotypes were observed and succeeding generations became less viable (Lee et al., 1998).

Efforts to develop telomerase inhibitors encountered several obstacles: i) Purified human telomerase was not available in large quantities, making screening for inhibitors more cumbersome; ii) Until relatively recently (Gillis et al., 2008; Sekaran et al. 2009), no high resolution structural information was available, complicating structure-based design strategies; iii) Telomerase is a polymerase, and inhibitors would need to be selective for its inhibition relative to other cellular polymerases; and iv) As mentioned above, telomere shortening was expected to yield delayed antiproliferative effects. Observation of the key end-point, cell death, would be delayed, forcing assays to be carried out over weeks or months. As a consequence, two or three months (or more) might be required to evaluate a compound and decide how to proceed with the next generation of compounds.

Preclinical and Clinical Development of Telomerase Inhibitors

One strategy for blocking telomerase focuses on their substrate: telomeres. Telomeres are G-rich sequences, TTAGGG in mammals. Structural studies have shown that these sequences form four-stranded G-quadruplexes (Henderson et al., 1987; Parkinson et al., 2002). Such quadruplex structures would need to unfold before telomerase could recognize telomere ends, leading to the hypothesis that small molecules promoting the formation of quadruplexes would block binding to telomerase.

Many different quadruplex-stabilizing agents have been identified (Sun et al., 1997) and several have been shown to have antiproliferative effects (Read et al., 2001; Riou, 2003). However, G-rich sequences exist elsewhere in the genome and binding to these sites can cause unexpected effects (Siddiqui-Jain et al., 2002). Another obstacle is the inherent difficulty of designing a planar compound with sufficiently selective intercalation into G-quadruplexes relative to the vast amounts of duplex chromosomal DNA. Advances in the field have slowed over the past five years, indicating that the obstacles confronting the development of potent, highly selective G-quadruplex-interacting agents have yet to be overcome.

Another strategy is to use oligonucleotides that are complementary to the RNA component of telomerase (Figure 2). To help elongate telomeres, this RNA component must be accessible to binding by telomere ends. It is logical that it should also be accessible to binding by synthetic oligonucleotides and that such binding should block interactions with telomeres and inhibit telomerase function. Two oligonucleotides are approved drugs and other promising candidates are advancing through clinical trials (Corey, 2007), suggesting that nucleic acids are a feasible option for clinical development of anti-telomerase agents.

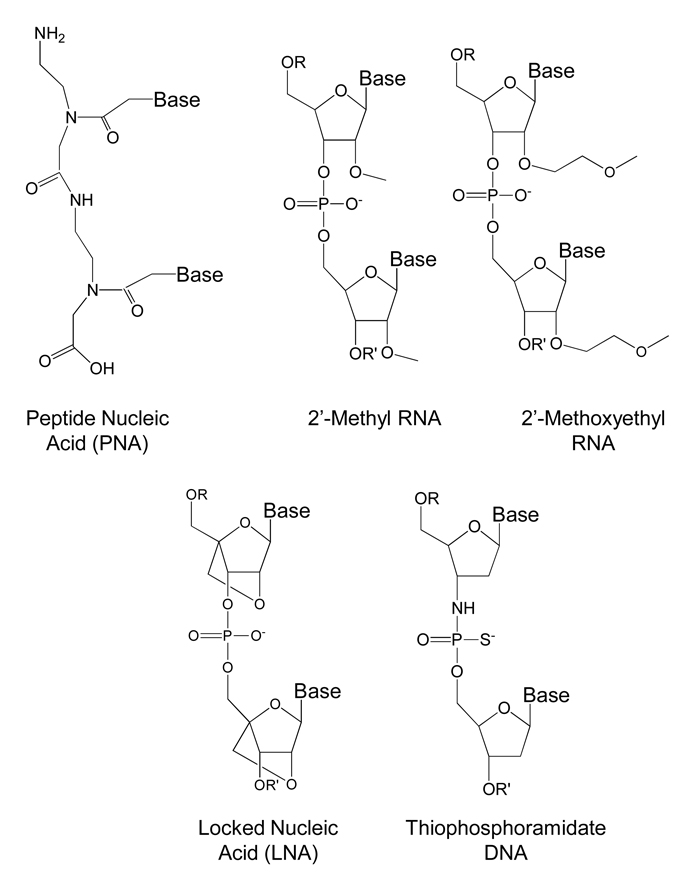

In 1996, my laboratory showed that single-stranded peptide nucleic acid (PNA) oligomers that are complementary to the template regions of the telomerase RNA subunit could inhibit telomerase activity in cancer cell extracts (Norton et al., 1996). Inhibition was both potent and sequence-specific. Rather than function like a standard antisense oligomer to degrade RNA or block translation, the oligomer acts like an enzyme inhibitor to block the telomerase active site. It is likely that their effectiveness is due to their simple and direct mechanism of action

Both PNAs, 2’-O-methyl, 2’-methoxyethyl, and locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligomers could be introduced into cells and inhibit intracellular telomerase (Herbert et al., 1999; Shammas et al., 1999; Chen et al. 2002; Chen et al., 2003, Elayadi, 2002). The oligonucleotides caused telomeres to gradually shorten (Figure 2B). Effects were observed most rapidly in cells with short telomeres and more slowly in cells with longer telomeres. 2’-O-methoxyethyl oligomers slowed tumor growth both in xenograft tumors (Figure 2C) (Chen et al., 2003) and in an orthotopic intraosseous prostate cancer model upon systemic administration (Li et al., 2009).

The potency and selectivity of oligonucleotides as telomerase inhibitors encouraged their development as drugs. Similar to the development of any oligonucleotide drug, the challenge was to identify an oligonucleotide chemistry with optimal pharmacological properties. Geron Corporation chose to focus on the development of oligomers containing phosphothioamidate backbones and, working with the Shay laboratory, demonstrated potent inhibition of telomerase (Herbert et al., 2002). Administration of anti-telomerase phosphoramidate oligonucleotide in a mouse xenograft model of prostate cancer suppressed tumor growth (Asai et al., 2003).

Most researchers working with therapeutic oligonucleotides had assumed that they could not efficiently enter cultured cells in the absence of transfection reagent. Anti-telomerase phosphoramidate oligomers, however, were potent inhibitors in the absence of transfection reagent (Herbert et al., 2002). This observation suggested that the phosphoramidate chemistry might confer advantages for cell uptake in vivo, a critical consideration for further development. Excellent cell uptake was also shown by anti-telomerase 2’-methoxyethyl oligonucleotides (Chen et al., 2002). Potent activity in the absence of transfection agent by two different oligomer chemistries reemphasizes the fact that telomerase is not a typical cellular RNA target and may have advantages for recognition by oligonucleotides that will facilitate progress in the clinic.

Examination of chemical modifications to improve anti-telomerase thiophosphoramidate oligomers continued, and it was discovered that addition of a lipid group further increased potency inside cells (Herbert et al, 2005). Lipidated oligonucleotides GRN163L was shown to reduce tumor growth in several animal studies (Dikman et al. 2005; Harley et al. 2008). GRN 163L is now being tested in Phase I and Phase I/II clinical trials for chronic lymphoproliferative disease, solid tumor malignancies, non-small cell lung cancer, multiple myeloma, and breast cancer (geron.com). Initial reports suggest that GRN163 is well tolerated by patients (Harley, 2008), although efficacy data has yet to be reported.

Most of these trials examine addition of GRN163L in addition to standard small molecule or antibody chemotherapeutic agents. Because of the potential lag between the onset of treatment and critical telomere shortening, inhibition of telomerase alone may not be sufficient. Combination treatments will also be necessary for most trials because of the necessity of providing the best existing care to patients participating in the trial. Because the mechanisms of action of telomerase inhibitors and standard antiproliferative agents differ it is possible that they might yield synergistic effects (Shay and Keith, 2008).

Three decades of progress

The science of telomerase and telomeres has come a long way since Elizabeth Blackburn first began experiments investigating chromosomal ends. The topic has drawn in researchers from many disciplines, including chemistry, structural biology, cell biology, aging, and cancer biology. This Perspective has focused on the connection between telomerase, cancer, and cancer therapy, but telomerase/telomeres also play a role in cellular aging (Aubert and Lansdorp, 2008) and recent work suggests that telomerase may play roles that go beyond telomere maintenance (Cong and Shay, 2008; Maida et al., 2009). Similarly, the discovery of noncoding transcription at telomeres (Luke and Lingner, 2009; Schoeftner and Blasco, 2009) suggests that they may be even more complex than had been originally imagined. It is likely that the next thirty years will yield a steady stream of new discoveries that profoundly affect our understanding of cells and provide opportunities for developing novel therapeutics.

Figure 3.

Structural features of PNA and chemically modified oligonucleotides used to inhibit human telomerase.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS 73042) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (I-1244).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Asai A, Oshima Y, Yamamoto Y, Uochi T, Kusaka H, Akinaga S, Yamashita Y, Pogracz K, Pruzan R, Wnunder E, Piatyszek M, Li S, Chin AC, Harley CB, Gryaznov S. A novel telomerase template antagonist (GRN163) as a potential anticancer agent. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3931–3939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert G, Lansdorp PM. Telomeres and aging. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:557–579. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH, Gall JG. A tandemly repeated sequence at the termini of the extrachromosomal ribosomal RNA genes in Tetrahymena. J. Mol. Biol. 1978;120:33–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco MA, Lee HW, Hande MP, Samper E, Lansdorp PM, DePinho RA, Greider CW. Telomere shortening and tumor formation in mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell. 1997;91:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broccoli D, Young JW, de Lange T. Telomerase activity in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. USA. 1995;92:9082–9086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Englezou A, Gupta J, Bachetti S, Reddel RR. Telomere elongation in immortal human cells without detectable telomerase activity. EMBO J. 1995;14:4240–4248. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales BK, Li Y, Thompson MG, Gleason JM, Chen Z, Malaeb B, Corey DR, Herbert BS, Shay JW, Koeneman KS. Small molecule, oligonucleotide-based telomerase template inhibition in combination with cytolytic therapy in an in vitro androgen-independent prostate cancer model. Urol. Oncol. 2006;24:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare AJ, Reddel RR. Telomere uncapping and alternative lengthening of telomeres. Mech. Aging Dev. 2008;129:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Monia BP, Corey DR. Telomerase Inhibition, Telomere Shortening, and Decreased Cell Proliferation by Cell Permeable 2’-O-Methoxyethyl Oligonucleotides. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:5423–5425. doi: 10.1021/jm025563v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Koeneman K, Corey DR. Effect of Telomerase Inhibition and Combination Treatments on Cancer Cell Proliferation. Cancer Research. 2003;63:5917–5925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Y, Shay JW. Actions of human telomerase beyond telomeres. Cell Res. 2008;18:725–732. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey DR. Chemical Modification: The Key to the Clinical Application of RNA Interference? J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3615–3622. doi: 10.1172/JCI33483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counter CM, Hirte HW, Bachetti S, Harley CB. Telomerase activity in human ovarian carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2900–2904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikmen ZG, Gellert GC, Jackson S, Gryaznov S, Tressler R, Dogan P, Wright WE, Shay JW. In vivo inhibition of lung cancer by GRN153L: A novel human telomerase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7866–7873. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elayadi AN, Braasch DA, Corey DR. Implications of high affinity hybridization by locked nucleic acids for inhibition of human telomerase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9973–9981. doi: 10.1021/bi025907j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis AJ, Schuller AP, Skodalakes E. Structure of the Tribolium Castaneum telomerase catalytic subunit. Nature. 2008;445:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature07283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. The telomere terminal transferase of Tetrahymena is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme with two kinds of primer specificity. Cell. 1987;51:887–898. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature. 1989;337:331–337. doi: 10.1038/337331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn WC, Stewart SA, Brooks MW, York SG, Eaton E, Kurachi A, Beijerbergen RL, Knoll JHM, Meyerson M, Weinberg RA. Inhibition of telomerase limits the growth of human cancer cells. Nat. Med. 1999;10:1164–1170. doi: 10.1038/13495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW. Telomeres shorten during aging of human fibroblasts. Nature. 1990;345:458–460. doi: 10.1038/345458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley CB. Telomerase and cancer therapeutics. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2008;8:167–179. doi: 10.1038/nrc2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial culture of diploid and transformed human fibroblasts. Exp. Cell. Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson E, Hardin CC, Walk SK, Tinoco I, Blackburn EH. Telomeric DNA oligonucleotides form novel intramolecular structures containing guanine-guanine base pairs. Cell. 1987;51:899–908. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert B-S, Pitts AE, Baker SI, Hamilton SE, Wright WE, Shay JW, Corey DR. Inhibition of human telomerase in immortal human cells leads to progressive telomere shortening and cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14276–14281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert B-S, Pongracz K, Shay JW, Gryaznov SM. Oligonucleotide N3’-P5’ phosphoramidates as efficient telomerase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2002;21:638–642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert B-S, Gellert GC, Hochreiter A, Pongracz K, Wright WE, Zielininska D, Chin AC, Harley CB, Shay JW, Gryaznov SM. Lipid modification of GRN163, an N3’-P5’ thio-phosphoramidate oligonucleotide, enhances the potency of telomerase inhibition. Oncogene. 2005;24:5262–5268. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama E, Hiyama K, Yokoyama T, Matsuura Y, Piatyszek MA, Shay JW. Nature Medicine. 1995;1:249–255. doi: 10.1038/nm0395-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PO, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Blasco MA, Gottlieb GJ, Horner JW, Greider CW, dePinho RA. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 1998;392:569–574. doi: 10.1038/33345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Maleab BS, Li Z, Thompson MG, Chen Z, Corey DR, Hsieh JT, Shay JW, Koeneman KS. Telomerase inhibition and cytolytic therapy in management of androgen independent osseuos metastatic prostate cancer. The Prostate. 2009 doi: 10.1002/pros.21096. in Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke B, Lingner J. TERRA: telomeric repeat-containing RNA. EMBO J. 2009;28:2503–2520. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maida Y, Yasukawa M, Furuuchi M, Lassmann T, Possemato R, Okamoto N, Kasim V, Hayashizaki Y, Hahn WC, Masutomi K. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase formed by TERT and the RMRP RNA. Nature. 2009;461:230–235. doi: 10.1038/nature08283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantell LL, Greider CW. Telomerase activity in germ line and embryonic cells of Xenopus. EMBO J. 1994;13:3211–3217. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin GB. The human telomere terminal transferase enzyme is a ribonucleoprotein that synthesizes TTAGGG repeats. Cell. 1989;59:521–529. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyzis RK, Buckingham JM, Cram LS, Dani M, Deaven LL, Jones MD, Meyne J, Ratliff RL, Wu J-R. A highly conserved repetitive DNA sequence, (TTAGGG)n, present at the telomeres of human chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:6622–6626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton JC, Piatyszek MA, Wright WE, Shay JW, Corey DR. Inhibition of human telomerase activity by peptide nucleic acids. Nature Biotech. 1996;14:615–620. doi: 10.1038/nbt0596-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olovnikov AM. A theory of marginotomy: The incomplete copying of template margin in enzymatic synthesis of polynucleotides and biological significance of the phenomenon. J. Theor. Biol. 1971;41:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(73)90198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson GN, Lee MPH, Neidle S. Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature. 2002;417:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read M, Harrison RJ, Romagnoli B, Tanious FA, Gowan SH, Reszka AP, Wilson WD, Kelland LR, Neidle S. Structure-based design of selective and potent G quadruplex-mediated telomerase inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:4844–4849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081560598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou JF, Guitat L, Mailliet P, Laoui A, Renou E, Petitegenet O, Megnin-Chanet F, Helene C, Mergny JL. Cell senescence and telomere shortening induced by a new series of specific G-quadruplex DNA ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:2672–2677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052698099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeftner S, Blasco MA. A ‘higher order’ of telomere regulation: telomere heterochromatin and telomeric RNAs. EMBO J. 2009;28:2323–2336. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran VG, Soares J, Jarstfer MB. Structures of telomerase catalytic subunits provide functional insights. Biochim. Biphys. Acta online. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shammas MA, Simmons CG, Corey DR, Reis RJS. Telomerase inhibition by peptide nucleic acids reverses ‘immortality’ of transformed cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:6191–6200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW, Zou Y, Hiyama E, Wright WE. Telomerase and Cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:677–685. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW, Keith WM. Targeting telomerase for cancer therapeutics. British J. Cancer. 2008;98:677–683. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui-Jain A, Grand CL, Bearss, and Hurley LH. Direct evidence for a G-quadruplex in a promoter region and its targeting with a small molecule to repress c-MYC transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11593–11598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182256799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Thompson B, Salazar M, Cathers B, Kerwin SM, Trent JO, Jenkins T, Neidle S, Hurley LH. Inhibition of human telomerase by a G-quadruplex interactive compound. J. Med. Chem. 1997;8:1063–1064. doi: 10.1021/jm970199z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak JW, Blackburn EH. Cloning yeast telomeres on linear plasmid vectors. Cell. 1982;29:245–255. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Origin of concatemeric T7 DNA. Nat. N. Biol. 1972;239:197–201. doi: 10.1038/newbio239197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Mar V, Zhou W, Harrington L, Robinson MO. Telomere shortening and apoptosis in telomerase inhibited human tumor cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2388–2399. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]