Abstract

We reviewed 192 patients (224 knees) to assess the results of HTO in medial gonarthrosis during the period 1982–2008. Median follow-up was about 15 years for 134 females and 58 males. Among the knees, 118 had an average opening wedge for varus angle of 13° and 106 had closing wedges of 11°. Knee Society scoring before osteotomies was 68/200 for opening wedge and 81/200 for closing wedge. Modified Ahlback classification showed preoperative grades I (n = 44), II (78), III (83) and IV (19). Healing delay was 55 days for closing and 70 for opening osteotomy. Twenty-nine knees were still painful. Twenty-eight patients were revised and 19 others had complications. After opening wedge osteotomy, scoring was 101/200 and valgus angle was 2°. After closing wedge osteotomy, scoring was 94/200 and valgus angle was 4°. Global results were as follows: very good, 12%; good, 30%; fair, 31%; and poor, 27%. HTO decreases stresses on medial compartments and widens joint space. The average of 5° mechanical valgus at the time of osteotomy seems to be quite effective at the follow-up for at least ten years. Our indications are opening wedge for grades 1–3 and wide varus angle, until the age of between 65–70. Closing wedge is indicated for medium varus in younger patients.

Introduction

Medial gonarthrosis is a joint disease that causes knee pain, reduction of activity and progressive alteration of the medial compartment, mainly in elderly and fat people. The current development of knee replacement must not eclipse the improvement gained from the high tibial osteotomy in the treatment of varus knee arthritis, particularly in the early stages and in young patients.

In comparison with arthroplasties, high tibial osteotomy (HTO) is quite an easy procedure. It is also less expensive, and more suitable for some countries for socio-economical reasons. HTO has been performed and published in the literature for about half a century by several surgeons including Jackson in 1958 [15], Wardle in 1962 [27], Gariépy in 1964 [9], Coventry in 1965 [5], etc. This technique is still widely used all over the world to treat varus knee arthritis. It remains a viable option for selected patients. Indeed, the osteotomy has several advantages and issues of concern.

We have reviewed a series of 224 opening and closing HTO in 192 patients operated up on between 1982 and 2008. We tried to find out, after a follow-up of about 15 years, what the results of valgisation were and which indications for osteotomy remain for medial knee arthritis in our selected patients.

Biomechanical justification

The following is from the works of many authors including Coventry et al. [6], Maquet [20] and Blaimont et al. [3].

In the standing position and chiefly during walking, the body weight tends to adduct the femur on the tibia, increasing thus the load on the medial compartment. The lateral muscular forces tend to adjust a dynamic equilibrium in the knees. The lateral force and the body weight result in an overload distribution of about 60% in the medial compartment and 40% in the lateral compartment [10].

In medial gonarthrosis, the resulting lateral force is displaced medially. Limb alignment is altered and more load is then distributed medially with subsequent degenerative lesions. This progressive joint destruction causes knee deformity, which, in a vicious circle, aggravates arthritis in the medial compartment.

Treatment by HTO therefore aims at correcting the excessive load stresses caused by an abnormal tibio-femoral angle. This is done by transferring the excessive load from medial to lateral, with respect to the lateral compartment. In other words, as enunciated by Sherman and Cabanella [25], “The goals of osteotomy are to relieve pain, to redistribute weight bearing forces, to improve function and thereby potentially increase the longevity of the native knee joint”.

Gonarthrosis evaluation

Clinical knee arthritis evaluation

Our evaluation for this series is borrowed from the Knee Society scoring system, which is based on two groups of parameters. The knee itself is scored from 0 to 100 for pain, stability and mobility. The functional abilities are also evaluated from 0 to 100. This clinical scoring includes the type of patient, the knee evaluation and the level of functional use.

The radiographic evaluation of the degenerative disease is based on a two-leg standing view with or without slight flexion, a one-leg standing view (anteroposterior and lateral views), anteroposterior (AP) stress views, tangential patellar view and an orthoradiogram to determine the mechanical axis (hip-knee-ankle).

Among these examinations, the standing and stress views have a major prognostic value. Thus, if there is a good lateral compartment and no medial laxity, this is considered a good indication for high tibial osteotomy.

The radiological classification

We use the Ahlbäck [2] classification for gonarthrosis radiographs modified by Koshino [18]. An anteroposterior radiograph taken in a standing position was used for grading. Grade 1 was bone sclerosis or osteophytes, grade 2 was narrowing of the joint space (≤ 3 mm), grade 3 was obliteration of the joint space, grade 4 was defect of the tibial plateau ≤ 5 mm, and grade 5 was a defect ≥ 5 mm.

A good classification such as this one is very important and useful for appropriate patient selection. It is worth noting the results of Hanssen et al. that “tibio femoral subluxation, excessive bony erosion and diffuse arthritic involvement are associated with poorer outcomes” [11].

Preoperative planning

Adequate planning must be made carefully from the orthoradiogram or on the AP bilateral standing views before any intervention. The anatomical or femoro-tibial angle is that between the axes of the femur and the tibia. It is normally between 3 and 6° valgus. The mechanical axis is the straight line from the femoral head to the centre of the ankle.

Decision making

It is difficult to succeed in all operations, even after a perfect procedure. One must remember some important criteria before osteotomy [16], e.g. varus deformity in the tibia, competent medial ligament with adequate lateral joint space, narrowing of the medial compartment and that the initial mechanical axis should pass through or medial to the medial compartment itself.

Contraindications

Regarding closing wedge high tibial osteotomy, after Marti and Verhagen [21], one should exclude moderate or severe ligamentous instability, severe varus deformity, diminished motion, severe flexion contracture, relative femoro-patellar arthritis and arthrosis in the lateral compartment.

In the contraindications to closing wedge osteotomy we should consider in particular the so-called ‘pagoda deformity’ with lateral ligament laxity and medial intra articular erosion. Otherwise, the osteotomised knee would be exposed to a higher level of instability.

Surgery

Aim and technique selection

The aim of the procedure is to discharge (unload) the stress on the medial compartment without overloading the lateral compartment. One must plan not only to restore the tibio-femoral mechanical axis, up to normal, but also to try to overcorrect by the method of Coventry et al. [6]. An over correction of about 5° of valgus is expected to give the most reliable results. We have chosen to perform surgery following two very well known HTO procedures: opening and closing techniques. Each one has some limitations to be considered before intervention, keeping in mind the several planning and surgical stages to be respected in order to avoid any under or over correction. In fact, it is more difficult to achieve a closing wedge osteotomy exactly as scheduled in the preoperative planning. Thus, an excessive closing angle is permanent. On the contrary, the opening technique is easier to adjust because one can open it more or less before fixing it. Our incisions try to provide large bridges of skin, allowing a para-patellar safe approach in case arthroplasty is needed in the future. After a subcutaneous release as described by Koshino and Tsuchiya [17], the above-tuberosity osteotomy is made. We use a pin and image intensifyer to achieve a good osteotomy wedge as accurately as needed.

Evaluation of the height of the wedge

Calculation of the wedge angle can be made in several ways. Among them, tables as provided by Koshino et al. [18] and Hernigou et al. [12], give precise measurements. Two other methods can give good evaluation of the height of the wedge. These are the weight bearing line method and the trigonometric method. The rule of thumb that the wedge carries about 1 mm for each 1° of angular correction is simple enough to be followed in most cases [11].

The opening wedge osteotomy

After a para-patellar or oblique incision, we begin by section of the crow’s foot tendons and proceed to a subcutaneous release. Then a pin is placed under image intensifyer view to identify the planned above-tuberosity osteotomy line. The lateral cortical apex of the wedge is brittle but not broken as we try not to break the hinge. The opening is made by introduction of a laminar bone spreader, while securing the medial cortex with a bone clamp. Stability of the leg is tested. The open wedge is maintained by tri-cortical iliac bone or synthetic graft [24], putting the knee into 5° of valgus. The fixation is made preferably by the use of a buttress plate. At the beginning of our study, we used staples and a moulded cast.

The closing wedge osteotomy

Closing HTO is increasingly less often considered by some authors as the "gold standard technique". In this procedure, with the knee fixed at 90°, we first disarticulate the upper tibio-fibular joint, or we perform a fibula osteotomy in the middle third of its diaphysis. For the tibia itself, we employ about 20° of flexion and generally use the Gariépy method, proximal to the tibial tubercle, which is commonly accepted to be stable and to heal rapidly [21].

Under image intensification, the first guide wire is placed parallel to the tibial articular surface. The second guide wire is based on the planned angle. Thus, a quite horizontal tibia osteotomy is made above the tibial tuberosity. The line of the first osteotomy starts at about 3 cm distal to the joint and ends about 2 cm medially. In young patients, we remove a laterally tibia-based triangle. In older patients, the wedge, totally or partially, can be advantageously morsellised and impacted under the lateral plateau [11].

Following the recommendations of Marti and Verhagen [21], two bone clamps are placed in both ends of the osteotomy in order to secure it and to compress it. Stability of the leg is then tested.

Bearing in mind the possibility of a calculation table as the rule of the thumb, we remove a laterally tibia-based triangle, trying not to cut the hinge, to obtain, generally, a valgus of 5°. Intraoperatively, we try to check and confirm the limb alignment with a metallic rod or a diathermy cable extended from the hip to the ankle. The fixation may be achieved by a buttress plate or by staples and splint. Weight bearing is allowed progressively from three to six weeks and active exercises are practiced.

Materials and methods

We reviewed 192 patients (224 knees) assessing indications in painful medial knee arthritis and results after HTO. The period of follow-up from the time of first intervention in 1982 until the last evaluation in 2008 ranged from five to 27 years (average about 15 years).

In this series, 134 females and 58 males underwent surgery. Their medium age at intervention was 55 years (range 40–72). Among them, 118 cases had opening wedge osteotomies with an average varus angle of 133° and 106 cases had closing wedges with an average varus angle of 11°.

In our clinical evaluation, we used the Knee Society clinical rating system [14] which has pain scoring based on 100 points and function scoring also based on 100 points (total of KS is 200). A protocol of assessment was applied to all the reviewed patients.

The total of the two KS scores out of 200 before intervention was 68 for opening and 81 for closing wedge. The classification showed that the preoperative stages were grade 1 (n = 44), grade 2 (78), grade 3 (83) and grade 4 (19) knees.

Results

Clinical findings

Residual pain at average follow-up was found in 29 patients, including 18 still using canes for walking, nine patello-femoral syndrome, and 12 knees with limited range of motion. The average flexion was 115°. Many authors submit that both techniques of opening and closing wedge osteotomy lead to comparably good comparable clinical results [12, 13].

Nonetheless, in our series, there were five findings to note.

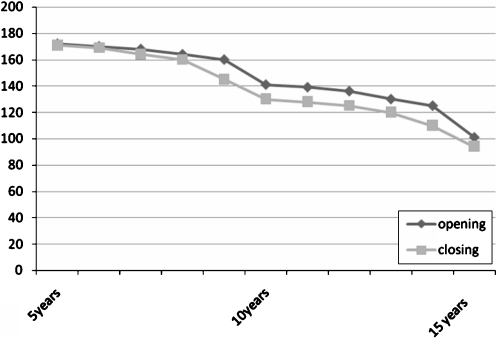

The total of the two KS scorings out of 200 after interventions was 101 for opening and 94 for closing wedge at follow-up (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Knee Society rating of opening and closing high tibial osteotomy (HTO) at 15 years

“The chi-squared test on the previous results derived a p-value which was higher than 0.01 (actual p-value equalled 0.159). One can therefore assume that the interventions using the “opening” technique do not give significantly better clinical results than interventions using the “closing” technique of high tibial osteotomy in medial gonarthrosis. However, given the level of the p-value, the latter gives more suggestive rather than significant better results.”

The postoperative classification improved slightly in both series and showed aspects at grade 1 (n = 29), grade 2 (94), grade 3 (79) and grade 4 (22) knees.

The chi-squared test on the previous results derived a p-value which was slightly higher than 0.05 (actual p-value equalled 0.18). One can therefore assume that a surgical intervention after 15 years does not give significantly better clinical results than no intervention. However, given the level of the p-value, the latter gives more suggestive rather than significant better results.

In addition, the initial KS scoring was somewhat lower than that of the closing wedge; while at follow-up, the KS evaluation was slightly higher (101 points for the opening osteotomy and only 94 for the closing wedge).

Therefore, we think that a slight preference for the opening technique should be considered since the opening technique was applied on bigger mechanical axis angulation, e.g. 13° for opening and only 11° for the closing technique.

In the literature, a whole set of statistics shows that the open wedge HTO “seems to be more predictable for correcting varus deformity of the knee” [8].

Radiological findings

The healing delay was 70 days for the opening and 55 days for the closing wedge osteotomy. The mean valgus angle remaining at follow-up of 15 years was 2° after opening and 4° after closing osteotomies (Fig. 2). The position of the patella was studied using the Caton index [4]. The calculations showed 6% patella alta after opening wedge and 7.5% baja were found in the closing series. These fairly high figures support the rigorous operative techniques described [25].

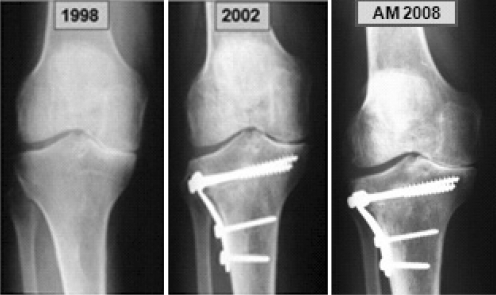

Fig. 2.

A 62-year-old male patient (D.L.) had a medial meniscectomy in the left knee in 1988. Two years later, we proceeded to a high tibial closing osteotomy for osteoarthritic varus. Fixation was done by staples. At that time, one could also note an osteochondritis on the left medial femoral condyle. This intervention allowed him a painless knee and normal activity until 1997 when he benefited from another closing wedge osteotomy on the right knee. For several years after the osteotomies, the patient could walk and run without any pain. At the last follow-up in 2008, he was still satisfied and active, walking without crutches. Meanwhile, his left medial condyle osteochondritis healed even though the arthritic radiological aspect was slightly worsening

Moreover, Aglietti et al. [1] state that it is possible that the opening wedge technique creates less deformity than the closing with tibial metadiaphyseal mismatch that might interfere with a subsequent revision to TKR (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A 63-year-old female patient (H.M.) who benefited from a right knee high tibial opening osteotomy in 1991 allowing the right medial compartment a quite good aspect for many years. In 1998, her left knee also deteriorated, which necessitated a closing procedure. The right medial joint space was looking quite nice in 1999, while a deformity of the closing osteotomy with tibial metadiaphyseal mismatch was visible on the left knee in 2002. At the last follow-up the knees were slight painful and the patient was walking with a cane

Complications

Thirty-seven revisions and other complications occurred including four new osteotomies, 23 arthroplasties, four early implant removals, four superficial infections, and two haematomata.

We also recorded two intra-articular fractures, four ruptures of the opposite cortical hinge, three cases of deep venous thrombosis, three temporary peroneal nerve palsies and one case of reflex dystrophy.

Overall outcome

The global results attest a relatively good initial outcome of HTO on clinical symptoms and radiological appearance. As expected, over time, clinical and radiological results deteriorate and become a concern for many patients beginning at 10–15 years follow-up.

Taking into account the initial clinical and radiological improvement and a progressive deterioration [23], the average long-term follow-up of 15 years however shows results of very good (12%), good (30%), fair (31%), and poor (27%).

Discussion

In the literature, the short-term satisfactory results and the long-term outcomes of osteotomy are still debated. Many papers reporting good results are those where surgeons have taken into account risk factors. Among them are age, weight, activity, opposite compartment, laxity, pain, as well as clinical and radiological evaluation.

Thus, Odenbring et al. [22] mentioned that "the ten to 19 years survival rate of properly overcorrected knees after HTO is better than that of many series of knee arthroplasty with the same follow-up".

High tibial osteotomy is, in fact, a simple procedure. It has a biomechanical purpose, and it is able to decrease the stresses on the medial compartment and to widen the joint space for several years. With neither special instruments, nor expensive implants, its cost is acceptable, while knee replacement demands a complete set of expensive instruments and implants.

Internal fixation is achieved by angulated plate or staples to maintain a good angular correction based on the calculated deformity.

The osteotomy enables patients at least to deal better with daily activities. Thus, the clinical results are quite satisfying, especially when the surgery is performed early in younger patients.

As reported by Lindstrand [19], "Even when all factors are dealt with properly and angulation is correct at healing, a few patients fail to obtain adequate pain relief; HTO is therefore not fully predictable."

Radiologically, the realignment with joint space widening was sufficient to delay progression of the arthritis or to manage it. Nonetheless, reasonable improvement and stabilisation with few complication is observed on the evolution of osteoarthritis after nearly ten years. It is worth noting that, even though the radiological degenerative changes may evolve in eventual aggravation, the clinical symptoms generally continue to improve after the intervention (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A 63-year-old man (A.M.) who had a painful arthritic right knee following a malalignment of the tibial diaphysis. After high tibial closing osteotomy and over a period of several years, he could walk and run without pain. The last two years he is a bit less satisfied due to mild pain. However, the patient is satisfied enough to not request an arthroplasty even after recurrence of medial space narrowing at the final follow-up

Therefore, the approximate five degrees of valgus, desired and achieved by the osteotomy, seem to be reasonably effective.

Thus, the osteotomy does not compete with knee replacement. It is rather a complementary technique to it, but with different indications [16].

Indications

Even though HTO has a longer postoperative recovery period with less pain relief after rehabilitation, Its indication is still to be balanced against that of the arthroplasties which might have catastrophic complications when an infection occurs. Many current indications for osteotomy are considered poor in comparison to the results of arthroplasties. Nonetheless, success or satisfactory X-rays at ten years follow-up after osteotomy are linked to careful patient selection with skilful surgical techniques.

We do agree with Marti and Verhagen [21] who state that "The ideal candidate of an osteotomy is a patient who has only unicompartmental osteoathritis with limb malalignement, no flexion contracture, a range motion of the knee of at least 100°, intact ligaments and no severe osseous defects."

Conclusions

High tibial osteotomy remains a useful and efficient procedure. The improvement seen in the post-op scoring encourages us to continue recommending HTO in the most painful early and medium stages.

When it is possible to choose between the two techniques, we would preferably decide as follows.

Opening wedge osteotomy is indicated in early, medium and advanced arthritis, in the older group, up to 70 years, and also if a large correction is needed. This opening technique allows easier placement of an eventual secondary TKA. It also has less neurovascular complication risks.

Closing wedge osteotomy in medium varus angles, in younger patients who generally have good bone stock.

High tibial osteotomy allows reasonably pain free knees, restoring axes and improving motion in most of them. HTO is thus very beneficial in cases of a good patient selection and good operative technique where 5° of valgus has been reached. In most cases, this osteotomy is good enough to avoid or to delay knee arthroplasties or at least diminish their number. Therefore, one can consider HTO as the best choice for the prevention and the treatment of early knee arthritis. The quality of long-term results remains dependent on the precision of correction and on the reduction of the varus [7].

References

- 1.Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Vena LM, Baldini A, Mondaini A. A high tibial valgus osteotomy for medial gonarthrosis: a 10- to 21-year study. J Knee Surg. 2003;16:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahlback S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1968;277(Suppl):7–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaimont P, Burnotte J, Baillon J, Duby P. Contribution à l’étude des conditions d’équilibre dans le genou normal et pathologique. Acta Orthop Belg. 1971;37:573–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caton J. Method of measuring the height of the patella. Acta Orthop Belg. 1989;55:385–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coventry M. Osteotomy of the upper portion of the tibia for degenerative arthritis the knee: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1965;47A:984–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coventry MB, Ilstrup DM, Wallrichs SL. Proximal tibial osteotomy: a critical long-term study of eighty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:196–201. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubrana F, Lecerf G. Tibial valgus osteotomy. Rev Chir Orthop Rep Appar Mot. 2008;94S:S2–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.rco.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaasbeek RDA, Nicolaas L, Rijnberg WJ, Loon CJM, Kampen A. Correction accuracy and collateral laxity in open versus closed wedge high tibial osteotomy. A one year randomized controlled study. Int Orthop. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0861-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gariépy R. Genu varum treated by high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Jone Surg Br. 1964;46:783–784. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haddad FS, Bentley G. Total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy: a medium-term review. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(5):597–603. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.6621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanssen AD, Stuart MJ, Scott RD, Scudery GR. Surgical options for the middle aged patient with osteoarthritis of the knee joint. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67(6):504–508. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(00)00206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernigou P, Medevielle D, Debeyre J, Goutallier D. Proximal tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis with varus deformity. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1987;69:332–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernigou P, Ovadia H, Goutallier D. Mathematical modelling of open wedge tibial osteotomy and correction tables. Rev Chir Orthop Rep Appar Mot. 1992;78:258–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the knee society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop. 1989;248:13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson JP. Osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1958;40:826. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.43B4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakob RP. Instabilitätsbedingte Gonarthrose-spezielle Indicationen für Osteotomienbei der Behandlung des instabilen Kniegelenkens. In: Jakob RP, Staubli HU, editors. Kniegelenk und Kreuzbander. New York: Springer Verlag; 1991. pp. 555–578. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koshino T, Tsuchiya K. The effect of high tibial osteotomy on osteoarthritis of the knee. Clinical and histological observation. Int Orthop (SICOT) 1979;3:37–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00266324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koshino T, Yoshida T, Ara Y. Fifteen to twenty-eight years’ follow-up results of high tibial valgus osteotomy for osteoarthritic knee. The Knee. 2004;11:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindstrand A (1999) Surgery of unicompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg 4:105–111

- 20.Maquet PGJ. Biomechanics of the knee: with application to the pathogenesis and the surgical treatment of osteoarthritis. 2. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marti RK, Verhagen RA (2001) Upper tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the knee. In: Surgical techniques in orthop and trauma. Elsevier, Paris, 55-530-A-10

- 22.Odenbring S, Egund N, Hagstedt B, Larsson J, Lindstrand A, Toksvig-Larsen S. Ten years results of tibial osteotomy for medial gonarthrosis. The influence of overcorrection. Archives Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;110:103–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00393883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papachristou G, Plessas S, Sourlas J, Levidiotis C, Chronopoulos E, Papachristou C. Deterioration of long-term results following high tibial osteotomy in patients under 60 years of age. Int Orthop. 2006;30:403–408. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0098-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahmi M, Ouabid A, Bekkali Y, Adnane N, Garch A, Largab A. Le traitement du genu varum par osteotomy de valgisation d’addition interne par cale de ciment. Rev Maroc Chir Orthop Traumato. 2008;37:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman C, Cabanela M. Closing wedge osteotomy of the tibia and the femur in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Int Orthop. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0883-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tigani D, Ferrari D, Trentani P, Barbanti-Brodano G, Trentani F. Patellar height after high tibial osteotomy. Int Orthop. 2001;24:331–334. doi: 10.1007/s002640000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wardle EN. Osteotomy of the tibia and fibula. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1962;101:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]