Abstract

Evolution of intracranial aneurysms is known to be related to hemodynamic forces such as Wall Shear Stress (WSS) and Maximum Shear Stress (MSS). Estimation of these parameters can be performed using numerical simulations (computational fluid dynamics - CFD) but can also be directly measured with MRI using a time-dependent 3D phase-contrast sequence with encoding of each of the three components of the velocity vectors (7D-MRV). In order to study the accuracy of 7D-MRV in estimating these parameters in–vivo, in comparison with CFD, 7D-MRV and patient-specific CFD modeling was performed for three patients who had intracranial aneurysms. A visual and a quantitative analysis of the flow pattern and the distribution of velocities, MSS, and WSS were performed between the two techniques. Spearman's coefficients of correlation between the two techniques were 0.56 for the velocity field, 0.48 for MSS and 0.59 for WSS. Visual analysis and Bland-Altman plots showed a good agreement for flow pattern and velocities but large discrepancies for MSS and WSS. In conclusion, these results indicate that in-vivo 7D-MRV can be used to measure velocity flow fields and to estimate MSS and WSS but is not currently able to provide accurate quantification of these two last parameters.

Keywords: Phase-contrast MRI, Computational Fluid Dynamics, Intracranial aneurysm, Wall Shear Stress

Introduction

With the development of non-invasive cerebrovascular imaging techniques, the frequency of diagnosis of unruptured cerebral aneurysms has increased (1), with reports that the incidence of those aneurysms in the general population is as high as 4.1% (2). Individuals with intracranial aneurysms are at major risk of rupture, thrombo-emboli, or compression of adjacent tissue, each with the potential for profound morbidity or death. However, most individuals remain asymptomatic: establishing criteria that will predict the likely evolution of aneurysms is therefore of high interest.

While most estimates of aneurysm-related risk are based on well-identified anatomic features such as aneurysm size (3) or other morphological features (location in the posterior circulation, wide neck and presence of daughter sacs (4), or aspect ratio (5)), hemodynamic parameters are also thought to be important determinants of risk. Of all the possible parameters, the velocity field, and descriptors derived from the velocity field, such as the maximum shear stress, and the wall shear stress (the value of shear stress at the lumen boundary), seem to be of particular interest (6,7). Maximum shear stress (MSS), calculated from the velocity gradients, represents the interaction between the different circulating blood layers in the aneurysm lumen and has an important role in platelet activation, and potentially in thrombus formation (8). Wall shear stress (WSS) represents the tangential force produced by blood moving across the endothelial surface. This stress acts on endothelial cell function and gene expression in addition to having an impact on the shape and structure of cells (9). WSS is thought to have an important role in aneurysm initiation (6), growth, and rupture (7,10).

There are no routine imaging methods available for measuring the velocity field in intracranial vessels. Two different approaches can be used, each making use of phase-contrast MRI: either the velocity field is calculated by numerical simulation using a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) code that takes the needed geometric boundary conditions from an in-vivo imaging study (such as MR or CT angiography) and the flow inlet conditions from 2D phase-contrast MRI (11),(12,13); or the velocity field can be directly measured using multi-dimensional phase-contrast MRI. MRI permits the acquisition of a seven dimensional data set consisting of each of the three components of the velocity vector, along each of the three coordinate axes covering the volume of interest, and at each phase of the cardiac cycle (14,15). This direct approach to measuring the velocity field, termed 7D MR velocimetry or 7D-MRV, is appealing as it avoids the complexities of performing a CFD calculation. 7D-MRV has been demonstrated in application to the measurement of velocities in large vessels in-vivo (16,17) and there have been validation studies in flow models of smaller vessels (18-21). There are a number of factors that compromise the accuracy of 7D-MRV. These include limitations in spatial and temporal resolution that result in velocity or partial volume averaging phenomena. Additional factors, such as imperfections in spatial and temporal features of the magnetic field (which can vary with the relative location to the iso-center or with the magnitude of eddy currents) further bring the accuracy of 7D-MRV into question. This is of particular concern when attempting the in-vivo determination of the velocity field and its derived quantities, the shear stresses, in regions of complex flow patterns, such as intracranial aneurysms (19).

The purpose of this study is to investigate the accuracy of 7D-MRV, performed in-vivo in patients with intracranial aneurysms, in the direct measurement of the velocity magnitude, the maximum shear stress, and the wall shear stress distributions in comparison with patient-specific CFD prediction.

Materials and Methods

Population

Three patients, referred to here as Patient 1 to 3, were prospectively included in this study (Table 1). All patients were part of an ongoing prospective study involving eleven subjects presenting with an intracranial aneurysm of the basilar trunk (22). IRB approval and informed consent were obtained for each patient.

Table 1.

Patient summary: Maximal diameter and total volume of the aneurysm of the basilar trunk.

| Patient ID | Age | Sex | Max Diameter (mm) | Volume (mm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 68 | Male | 12.0 | 1730 |

| 2 | 44 | Male | 18.2 | 4035 |

| 3 | 59 | Male | 13.9 | 2865 |

MR protocol

MR studies were performed on a 1.5-Tesla scanner (Achieva®, Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH). The patient was positioned in a 6 channel head coil. A three-step imaging protocol was used.

First, contrast-enhanced MR angiography (CE-MRA) was performed using a 3D slab covering the vessels of interest with an injection of 18 ml GdDTPA followed by 15ml of saline all delivered at 2 ml/s. The CE-MRA sequence used elliptic-centric phase reordering, and data were acquired using parallel imaging with an acceleration factor of 2. Imaging parameters included: TR / TE / flip angle=5 ms / 2 ms / 30°. Images were acquired from a 54 mm para-coronal slab, with an FOV of 240 mm and an acquisition matrix of 400×286×45 zero-filled to 512×512×90. The resultant images had a resolution of 0.6×0.6×1.2 mm3 and were interpolated to 0.47×0.47×0.6 mm3. Total acquisition time was of the order of 35 s.

Then, in order to measure the flow rate into the aneurysm, data that is necessary for CFD modeling, through-plane phase-contrast MRV was performed in planes transverse to the vertebral arteries proximal to the lesion. Acquisition parameters were as follows: slice thickness=5 mm, field of view=160 mm, in-plane pixel size=1×1 mm2, velocity-encoding level=50-75 cm/s. Thirty two time points were acquired through the cardiac cycle, providing the time-varying inlet boundary conditions required for the pulsatile flow simulations.

Finally, the 7D-MRV data set was acquired using a 3D slab in the longitudinal plane with the following parameters: number of partitions=8 to 12 (depending on the thickness of the aneurysm), slice thickness=1.2 mm, field of view=240×190 mm, in-plane pixel size=1×1 mm, SENSE factor=1.6, TFE factor=3, TR / TE / flip angle = 8.6 ms / 4.2 ms / 8° and Bandwidth = 190 hz / pixel. Velocities were encoded in the three direction of space with an encoding level adapted to each patient in order to prevent aliasing (80, 100 and 160 cm/s respectively for patients 1 to 3). The temporal duration of each phase was about 66 ms and the number of phases acquired through the cardiac cycle, depending on patient's cardiac frequency, was 11, 12 and 13 respectively for patient 1, 2 and 3. Magnitude and phase-contrast images were reconstructed. The total acquisition time was of the order of 10 minutes.

Model construction, numerical simulations and 7D dataset reconstruction

We have previously reported on the methodology used but summarize it here (23). For each patient, CE-MRA data were transferred to custom-built software to form three-dimensional isosurfaces. The obtained surfaces were then transferred into 3D modeling software, Rapidform (INUS Technology, Seoul, South Korea), where the background noise and smaller vessels were separated from the main vessels of interest and a polygonal surface was formed. Remaining singularities and spikes were then removed, holes in the surface were filled, and Laplacian smoothing, which conserves global volume, was applied to make the surfaces continuous and regular. At this stage, a clean triangular mesh was obtained for each patient (Fig. 1) and used, after manual division of the surface into rectangular patches, as boundaries for the numerical simulation of the flow. The velocity fields and wall shear stresses were computed using a finite-volume CFD solver (Fluent Software, Fluent Inc., Lebanon, NH) (10,12,22). An unstructured mesh was generated on the computational domains with spatial resolution between 0.1×0.1×0.1 mm and 0.3×0.3×0.3 mm. In order to ensure mesh independence of the numerical solution, steady flow simulations for patient 2 were carried out on increasingly refined meshes until the changes of the predicted velocities and WSS became negligible. The same mesh density was used for the remaining models as the aneurysm sizes were of the same order. Second-order schemes were used for numerical discretization in space and time and the iteration steps were repeated until convergence was reached, as indicated by a four-order magnitude reduction of the residuals.

FIG. 1.

Triangular meshes of the surface obtained for each patient's aneurysm. Left: patient 1, Center: patient 2, and Right patient 3.

The flow was assumed to be laminar and Newtonian and arterial walls were assumed rigid. While linearly-elastic models based on healthy arterial wall properties suggest that wall compliance can affect WSS distribution, we consider the rigid wall to be a reasonable assumption for our modeling purposes, since aneurysmal blood vessels lack elastin and therefore have little compliance (24). In addition, cine images show no appreciable motion of the aneurysmal vessel wall over the cardiac cycle. Even if the relatively small distensions seen in healthy vessels were present in these diseased arteries, their effects on the velocity field are much smaller than those that result from vessel geometry.

The patient-specific pulsatile inlet flow conditions were specified using the through-plane phase-contrast MRI measurements. In the vertebro-basilar system, there is an extended length of vertebral artery proximal to the basilar artery (the volume of interest) and uniform velocity profiles were assumed in the proximal vertebral arteries with values set to match the flow values measured in vivo. This is a reasonable assumption given that flow at the origin of vessels is expected to be uniform. It was further assumed that flow exiting from the aneurysm divides to provide equal flow to the right and left hemispheres, which is physiologically reasonable. The pulsatile simulations were performed through three cardiac cycles to eliminate the influence of initial transients and results obtained for the last cycle were used for the comparison with 7D-MRV.

In addition to WSS, the distribution of maximum shear stress was also calculated for each patient from velocity derivatives (23). The value of MSS indicates the maximum possible shear stress level for a given shear stress tensor and is computed as one half of the difference between the maximum and minimum eigenvalues of the shear stress tensor. At the same time, the 7D dataset was reconstructed for each patient using custom-built software based on the VTK package (Kitware Inc., Clifton Park, NY). First, the aneurysm boundary was manually delineated on the magnitude images (8 to 12 slices per patients). Those contours were transferred to the corresponding phase-contrast images. As three directions of the velocity were encoded, each contour was used, for each phase of the cardiac cycle, on three phase-contrast images, one for each velocity encoding direction. A three dimensional matrix was then built with each voxel containing, for each phase of the cardiac cycle, the three components of the measured velocity vector. This matrix was called the 7D matrix as it contained the 3D spatial location of 3 components of the velocity vectors measured across time. 7D matrix spatial resolution was identical to the MRI acquisition resolution, ie 1×1×1.2 mm. The shape extracted from the CE-MRA dataset (and used as an input for CFD simulation) was then registered with the 7D matrix and used as a mask. All voxels of the 7D matrix which were not included in the shape were set to zero. This step is very important as the exact location of the boundaries of the aneurysm lumen (particularly important for wall shear stress calculation) is difficult to precisely define on the magnitude images alone (25). The sharp boundaries that are provided by the high resolution CE-MRA can be used to eliminate voxels that are not part of the flow lumen and that would otherwise contribute to the surrounding noise (Fig. 2). Furthermore, this registration enables a calculation of the transformation matrix that can be used for determining the correspondence in spatial location between each voxel in the 7D matrix and in the dataset of the CFD calculation.

FIG. 2.

7D-MRV dataset cleaning. The 7D-MRV dataset (left) is registered with the mesh built from the CE-MRA images (green transparent surface, center). All the velocity vectors of the 7D-MRV dataset located outside the surface mesh are discarded (right).

The final step of the 7D dataset processing was the calculation of the maximum shear stress and the wall shear stress. For maximum shear, the velocity derivatives were first calculated in each voxel by using the difference in velocity components of the immediate neighboring voxels. Maximum shear stress was then calculated with the same formula as used for CFD. Wall shear stress was estimated as τ = μ(du/dr) where, μ is viscosity (0.035 Pascal.sec for blood), and du/dr is the velocity gradient at the wall (sec-1) (26). With the standard assumption that the velocity at the wall is zero, du/dr can be determined at each location on the surface by considering a point in the lumen along a line normal to the location of interest at a distance (dr) from the surface. The gradient du/dr is then the ratio of the magnitude of the component of the velocity vector component parallel to the surface, to the distance (dr). Determination of the correct distance dr is difficult so we repeated the calculation for a range of different values of dr from 0.1 to 1.0 mm in steps of 0.1 mm and later compared these results to the WSS obtained in numerical simulations. This calculation was implemented as follows: a normal vector was computed for each triangle of the surface of the triangular mesh obtained from CE-MRA. The velocity vector located at a distance dr along the vector normal to the surface triangle was selected. The component of this vector parallel to the plane formed by the surface triangle was then calculated. Wall shear stress was estimated by dividing the norm of this component (du) by the distance from the wall (dr) (27).

Finally, in order to obtain a quantitative comparison between CFD and 7D-MRV, 1 mm3 voxels were selected at regular intervals through the aneurysm (for velocities and maximum shear stress comparisons) or over its surface (for wall shear stress comparison). This voxel size corresponds to one voxel in the 7D-MRV dataset. For CFD, where the resolution is higher, the measured values were averaged within the voxel. Two representative cardiac phases were studied for each patient: end-diastole and peak-systole.

Images and statistical analysis

Visual comparison was performed between CFD and 7D-MRV using a velocity vector display for the global velocity field correlation, a cut plane through the dataset for the maximum shear analysis, and surface rendering for wall shear stress analysis.

Bland-Altman plots were constructed to compare CFD and 7D-MRV values of velocity, maximum shear stress, and wall shear stress.

A linear regression was performed between 7D-MRV and CFD for each type of measured value. A term representing the systolic or diastolic phase and its interactions with the measured values was introduced in order to account for the potential effect of the differences between the two cardiac phases on the result of the regression analysis. Spearman coefficients of correlation between the two techniques were also calculated. All statistical analysis was performed using Intercooled Stata 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Flow conditions for all three subjects were fully analyzed with both CFD and 7D-MRV. Visual comparison between the two techniques is provided in Figs. 3-5. Data are displayed at peak systole because it presents a wider range of velocity values, and a more complete illustration of the flow complexity.

FIG. 3.

Representation of velocities for patient 1 to 3 in systolic phase. CFD predictions (left) are compared to 7D-MRV findings (right). Velocity range and global flow pattern is comparable between the two techniques.

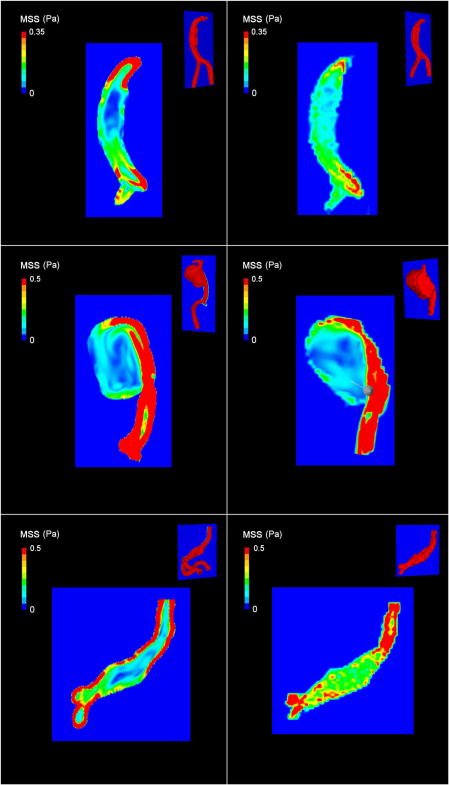

FIG. 5.

Representation of wall shear stress (WSS) for patients 1 to 3 in systolic phase (CFD - left, 7D-MRV - right). Despite the difference in WSS values, there is still a relatively good visual correlation between the two techniques in regard to the location of high and low wall shear stress.

Patient 1 presents with a fusiform linear aneurysm. There is an asymmetric inlet flow with a larger amount of flow entering through the right inlet vessel (vertebral artery) (2.1 ml/s) than through the left (0.7 ml/s). As the vessel widens in the mid-section of the aneurysm, a decrease in flow speed (corresponding to smaller and bluer vectors) is noted. Maximum shear stress values are higher at the proximal and distal segments and are relatively low in the wide mid-section of the aneurysm. Wall shear stress is relatively uniform in the aneurysm, with the highest value at the knee of the right inlet vessel where vessel curvature drives higher velocities to the outside wall.

Patient 2 presents with a larger aneurysm. The velocity vector field study shows, in both 7D-MRV and CFD, rapid flow through the inlet, much of it bypassing the aneurysm to directly flow through the outlet. A small fraction of the inlet flow enters the aneurysm through the distal aspect and forms a large region of recirculating flow that is visible in the aneurysm body. This particular flow pattern results in high values of maximum shear and wall shear stress in the regions of fast passage and very low values in the recirculating zone.

Patient 3 presents with an aneurysm that is similar to that of patient 1 with comparable features in terms of flow field and shear.

In terms of quantitative analysis, Spearman's rho coefficients of correlation between 7D-MRV and CFD were 0.56 for the velocity field and 0.48 for the maximum shear field. For wall shear stress, the best agreement between the two methods was found when the analysis was performed using 0.3 mm as the distance from the wall. This yielded a Spearman's coefficient of correlation between the two techniques of 0.59 (the lowest Spearman's coefficient was 0.53 for a distance of 1 mm). All wall shear stress values and graphical representations are therefore presented using values obtained by sampling the velocity field at a distance of 0.3 mm from the wall.

Bland Altman plots comparing the two techniques for velocity, maximum shear, and wall shear stress measurements are provided in Fig. 6. Linear regression analyses for the three types of values are provided in Fig. 7. Both systolic and diastolic points are included in this analysis as no significant effect of cardiac phase (systole or diastole) was found with the multiple regression approach. R-squared values were 0.54, 0.40 and 0.33 for the velocity, maximum shear and wall shear stress analyses, respectively. Line equations are provided in the legend of the figures.

FIG. 6.

Bland-Altman plot representation of 7D-MRV and CFD for velocities, maximum shear stress and wall shear stress. Solid lines show the mean; dotted lines the 95% confidence interval.

FIG. 7.

Scatter plot representation and regression line for 7D-MRV and CFD for velocities, maximum shear stress and wall shear stress. Slope, intercept and R-squared values are respectively 0.54, 0.2 and 0.54 for velocities, 0.26, 0.1 and 0.40 for maximum shear stress and 1.70, 3.42 and 0.33 for wall shear stress (p<0.001). All patients' values are plotted together. Triangles represent points from systolic phase, circle points from diastolic phase.

Discussion

This study confirms the feasibility of using 7D-MRV for in-vivo velocity flow field analysis in intra-cranial aneurysms but also underlines some important limitations of 7D-MRV in local velocity magnitude measurement and in shear stress estimation.

Visual comparison of the velocity field measured using 7D-MRV shows good agreement with the results of CFD calculations. MR measurements of maximum shear stress also appear reasonable but with some discrepancies. For example, 7D-MRV provides values of shear stress that are much lower close to the outlet in patient 1, and of much lower resolution, particularly in the mid-section of the aneurysm in patient 3, than was found with CFD. Qualitatively, the maps of WSS provided by the two methods show agreement in regard to the locations where WSS is relatively high, and where it is relatively low. Nevertheless, absolute values of shear stress are very different between the two techniques particularly for WSS which required the use of different color scales on the images in order to adequately display the range of values present. This reflects the fact that CFD is capable of much higher resolution than 7D-MRV.

The good correlation between 7D-MRV and CFD in terms of delineating the structure of the velocity field is in agreement with previous studies that compared 7D-MRV against a reference standard such as CFD or Laser Doppler Velocimetry in realistic ex vivo flow models (19),(28) or that compared in vivo 5D-MRV (equivalent to 7D-MRV but with only one component of velocity encoding) against CFD (22). 7D-MRV provides visualization of regional changes in the flow, such as jets or vortices in regions of recirculation (Fig. 8). However, even if the correlation in terms of velocity magnitude is significant between the two techniques, the dispersion relative to the local errors of measurement with MRV remains important (r-square=0.54).

FIG. 8.

Cut planes in patient 2 showing some details in the velocity field measured with 7D-MRV. Space locations of the planes are represented in the top right corners. A large vortex is visible in the recirculating area.

The CFD calculations assume that the wall boundaries are rigid through the cardiac cycle whereas the in vivo measurements are made with the actual time-varying geometries. However, observation of the magnitude images through the cardiac cycle, and independent cine-mode images, reveal that there is little or no vascular distension in the vessels of interest. This is not surprising for aneurysmal segments as they have lost their elastin and have much reduced compliance. Furthermore, simulations in aneurysmal geometries that include compliance effects of the order of those seen in healthy vessels, show that the effects of geometry far exceed the effects of compliance, and it is therefore reasonable to neglect compliance in this analysis.

Several factors lead to errors in 7D-MRV velocity measurement. First, spatial averaging resulting from limitations in spatial resolution in MRI are important, particularly in regions where there is a broad distribution of velocities within a single voxel, such as at the edge of vessels. This error cannot be directly estimated with our methodology as we down sampled the data from CFD using an averaging technique in order to match the resolution of the 7D-MRV for comparison sake. Temporal resolution is also an important factor. Indeed, current implementations of 7D-MRV are limited by gradient performance and have relatively low temporal resolution (around 100 ms) compared to CFD. This results in velocity averaging through time, reducing the ability of MRI to estimate transient events. The sensitivity of the MR measurement to low values of velocities is governed by the setting that is chosen for the velocity encoding level, or VENC. It is usual for the VENC to be set sufficiently high to avoid aliasing in those regions with the highest velocity and the velocity to noise ratio is therefore compromised in regions of slow flow, which are generally at the boundary of the lumen. Methods for increasing the velocity to noise ratio, such as using multiple VENCs, or reduced VENCs with phase unwrapping, would be helpful to provide increased sensitivity to low flow conditions. Finally, velocities can be affected by interferences generated for example by uncorrected Maxwell terms, Eddy currents, or small gradient waveform errors. This results in error in velocity measurement varying across the image, generally increasing with the distance to the isocenter of the magnet (29).

The absence of an effect of the cardiac phase on the regression model, and the absence of any particular trend on the Bland-Altman plot is also an important feature. Indeed, it supports the fact that absolute velocity measurement errors remains constant in the range of in vivo intra-aneurismal velocity values, with no particular offset on the Bland-Altman plot, indicating that, despite locals errors in velocities, MRI can still be used for mean velocity calculations and, consequently, for flow calculations (30).

Accuracy of MRI appears to be lower for maximum shear stress evaluation than for velocities. Indeed, in addition to sources of errors in velocity measurement, the relatively low spatial and temporal resolution of MRI (in comparison with CFD) results in an averaging of the measured velocities which strongly impacts the calculated values of the velocity gradients. An example of this phenomenon is presented in Fig. 9, part A, with a substantial smoothing of the shear values particularly when these values are high, i.e., in regions of rapid spatial change in velocity. This effect is responsible for the greater difference between CFD and 7D-MRV at high shear values as seen on the Bland Altman representation. It also results in an overall lower spatial resolution of the shear in MRI than in CFD as seen on Fig. 9, part B and on the maps in Fig. 4. In practice, although MRI can provide an estimation of the relative distribution of the shear stress in the aneurysm (as seen in Fig. 4), errors in gradient calculation can be large and absolute values of shear stress are not reliable.

FIG. 9.

Comparison of maximum shear stress slice profiles between CFD (black) and 7D-MRV (grey) in patient 1 at peak systolic phase at two different anatomic location (A and B). Smoothing of the curve as well as loss in contrast between high shear area (peripheral) and low shear area (middle of the lumen) clearly appear with 7D-MRV in comparison with CFD.

FIG. 4.

Representation of maximum shear stress (MSS) for patient 1 to 3 in systolic phase. Values obtained from CFD (left) and 7D-MRV (right) measures are shown. Cut plane position is displayed for each model in the top right corner. The spatial averaging effect is clearly seen on the 7D images, particularly in the center of the aneurysms in patient 1 and 3 leading to a lower contrast between high and low shear zones. Furthermore, the maximum shear stress values globally appear lower in 7D-MRV than in CFD as red colored areas are smaller.

Wall shear stress calculation is also strongly affected by MRI errors in velocities and by limited spatial and temporal resolution. This mainly results in a global overestimation of the WSS, particularly in regions of high shear as demonstrated by the Bland-Altman plot. MRV provides an average over all velocity vectors within a pixel. At the vessel wall, a single pixel contains components of velocity that are extremely low (those immediately adjacent to the wall), and others that can be relatively high (one pixel from the wall). Averaging over these velocities leads to erroneous results and to poor correlation with CFD.

The calculation of WSS is least accurate when 7D-MRV data is used alone (i.e. without making use of better defined boundary conditions, such as are available from the MRA studies used in our analysis). When used alone, 7D-MRV relies on lumen edge definition on the magnitude image of the phase contrast MRI which is often difficult to delineate (25). This results in errors in wall position, and local surface orientation, degrading the WSS calculation. This is exacerbated when noise is included from surrounding structures which is particularly pronounced if the that structure has little or no magnetization (air or bone for example)(29).

Finally, the WSS calculation requires a selection of velocity vectors close to the wall, and it is important to use a reasonable estimate of that distance as it can affect the results. We found a better correlation with CFD when using a distance equal to one third of the pixel resolution (0.3 mm) rather than a greater distance as proposed by other teams (0.5 mm for Tateshima and al. (31) or 0.7 mm for Ahn and al. (27)). Despite this, estimation of WSS by 7D-MRV in vivo remains imprecise and, although it can give a rough estimation of WSS, absolute values directly determined from MRI are not trustworthy. A combination of CFD and MRI/MRV for boundaries and inlet conditions is preferred.

A limitation of our study is related to the spatial and temporal resolution used in the MRI acquisitions. It was not possible to obtain better than 1 mm3 spatial resolution and 100 ms temporal resolution with a scan time of 10 minutes. A longer scan time would permit improving this resolution but it also increases the likelihood of patient motion, which can substantially degrade the measurements, particularly in studies of small vessels. Imaging at higher field strengths, such as 3T, would provide increased SNR which could be used either to reduce imaging time by use of higher acceleration factors, or for improved resolution (32) although errors in velocity measurements that result from scanner imperfections at higher field strengths are not yet well characterized. These studies were performed several minutes after injection of GdDTPA where the signal boost from the contrast agent is largely dissipated. Although not universally approved for use in patients, the use of intravascular contrast agents could potentially provide a substantial increase in SNR allowing reductions in scan time or improvements in image resolution (33). Another limitation is the absence of the evaluation of the inter-patient reproducibility of the 7D-MRV technique. A determination of the statistical significance of this method across multiple subjects will require investigations in a larger number of patients.

Conclusion

The present study reports a comparison of in vivo 7D-MRI measurements of the velocity field in intracranial aneurysms with the results of a CFD model, built from patient-specific anatomic and flow data. MRI allows a good estimation of the flow field pattern inside the aneurysm with velocity values that are acceptable for clinical purposes. Nevertheless, mainly because of spatial and temporal averaging, the measurements of velocity gradients have large errors that lead to misestimation of quantities such as maximal and wall shear stress. Therefore, although 7D-MRI can provide a rough estimate of these parameters, it is not currently capable of providing accurate absolute measurements of WSS.

Acknowledgments

Loic Boussel acknowledges support from the Société Française de Radiologie, 20, Avenue RAPP, 75007 Paris, France.

References

- 1.Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, Vincent AJ, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Niessen WJ, Breteler MM, van der Lugt A. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1821–1828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krex D, Schackert HK, Schackert G. Genesis of cerebral aneurysms--an update. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2001;143(5):429–448. doi: 10.1007/s007010170072. discussion 448-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unruptured intracranial aneurysms--risk of rupture and risks of surgical intervention. International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(24):1725–1733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812103392401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J, 3rd, Meissner I, Brown RD, Jr, Piepgras DG, Forbes GS, Thielen K, Nichols D, O'Fallon WM, Peacock J, Jaeger L, Kassell NF, Kongable-Beckman GL, Torner JC. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet. 2003;362(9378):103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nader-Sepahi A, Casimiro M, Sen J, Kitchen ND. Is aspect ratio a reliable predictor of intracranial aneurysm rupture? Neurosurgery. 2004;54(6):1343–1347. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000124482.03676.8b. discussion 1347-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng H, Wang Z, Hoi Y, Gao L, Metaxa E, Swartz DD, Kolega J. Complex hemodynamics at the apex of an arterial bifurcation induces vascular remodeling resembling cerebral aneurysm initiation. Stroke. 2007;38(6):1924–1931. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.481234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shojima M, Oshima M, Takagi K, Torii R, Hayakawa M, Katada K, Morita A, Kirino T. Magnitude and role of wall shear stress on cerebral aneurysm: computational fluid dynamic study of 20 middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Stroke. 2004;35(11):2500–2505. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000144648.89172.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wurzinger LJ, Blasberg P, Schmid-Schonbein H. Towards a concept of thrombosis in accelerated flow: rheology, fluid dynamics, and biochemistry. Biorheology. 1985;22(5):437–450. doi: 10.3233/bir-1985-22507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. Jama. 1999;282(21):2035–2042. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jou LD, Quick CM, Young WL, Lawton MT, Higashida R, Martin A, Saloner D. Computational approach to quantifying hemodynamic forces in giant cerebral aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(9):1804–1810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long Q, Xu XY, Collins MW, Griffith TM, Bourne M. The combination of magnetic resonance angiography and computational fluid dynamics: a critical review. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 1998;26(4):227–274. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v26.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cebral JR, Castro MA, Appanaboyina S, Putman CM, Millan D, Frangi AF. Efficient pipeline for image-based patient-specific analysis of cerebral aneurysm hemodynamics: technique and sensitivity. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24(4):457–467. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2005.844159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinman DA, Milner JS, Norley CJ, Lownie SP, Holdsworth DW. Image-based computational simulation of flow dynamics in a giant intracranial aneurysm. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(4):559–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wigstrom L, Sjoqvist L, Wranne B. Temporally resolved 3D phase-contrast imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(5):800–803. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markl M, Chan FP, Alley MT, Wedding KL, Draney MT, Elkins CJ, Parker DW, Wicker R, Taylor CA, Herfkens RJ, Pelc NJ. Time-resolved three-dimensional phase-contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17(4):499–506. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markl M, Draney MT, Hope MD, Levin JM, Chan FP, Alley MT, Pelc NJ, Herfkens RJ. Time-resolved 3-dimensional velocity mapping in the thoracic aorta: visualization of 3-directional blood flow patterns in healthy volunteers and patients. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28(4):459–468. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hope TA, Markl M, Wigstrom L, Alley MT, Miller DC, Herfkens RJ. Comparison of flow patterns in ascending aortic aneurysms and volunteers using four-dimensional magnetic resonance velocity mapping. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(6):1471–1479. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tateshima S, Grinstead J, Sinha S, Nien YL, Murayama Y, Villablanca JP, Tanishita K, Vinuela F. Intraaneurysmal flow visualization by using phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging: feasibility study based on a geometrically realistic in vitro aneurysm model. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(6):1041–1048. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollnagel DI, Summers PE, Kollias SS, Poulikakos D. Laser Doppler velocimetry (LDV) and 3D phase-contrast magnetic resonance angiography (PC-MRA) velocity measurements: Validation in an anatomically accurate cerebral artery aneurysm model with steady flow. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(6):1493–1505. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papathanasopoulou P, Zhao S, Kohler U, Robertson MB, Long Q, Hoskins P, Xu XY, Marshall I. MRI measurement of time-resolved wall shear stress vectors in a carotid bifurcation model, and comparison with CFD predictions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17(2):153–162. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall I, Zhao S, Papathanasopoulou P, Hoskins P, Xu Y. MRI and CFD studies of pulsatile flow in healthy and stenosed carotid bifurcation models. J Biomech. 2004;37(5):679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boussel L, Wintermark M, Martin A, Dispensa B, Vantijen R, Leach J, Rayz V, Acevedo-Bolton G, Lawton M, Higashida R, Smith WS, Young WL, Saloner D. Monitoring Serial Change in the Lumen and Outer Wall of Vertebrobasilar Aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(2):259–64. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dispensa BP, Saloner DA, Acevedo-Bolton G, Achrol AS, Jou LD, McCulloch CE, Johnston SC, Higashida RT, Dowd CF, Halbach VV, Ko NU, Lawton MT, Martin AJ, Quinnine N, Young WL. Estimation of fusiform intracranial aneurysm growth by serial magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(1):177–183. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphrey JD, Na S. Elastodynamics and arterial wall stress. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30(4):509–523. doi: 10.1114/1.1467676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohler U, Marshall I, Robertson MB, Long Q, Xu XY, Hoskins PR. MRI measurement of wall shear stress vectors in bifurcation models and comparison with CFD predictions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14(5):563–573. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munson BR, Y D, Okiishi TH. Fundamentals of fluid mechanics. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahn S, Shin D, Tateshima S, Tanishita K, Vinuela F, Sinha S. Fluid-induced wall shear stress in anthropomorphic brain aneurysm models: MR phase-contrast study at 3 T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(6):1120–1130. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Botnar R, Rappitsch G, Scheidegger MB, Liepsch D, Perktold K, Boesiger P. Hemodynamics in the carotid artery bifurcation: a comparison between numerical simulations and in vitro MRI measurements. J Biomech. 2000;33(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatehouse PD, Keegan J, Crowe LA, Masood S, Mohiaddin RH, Kreitner KF, Firmin DN. Applications of phase-contrast flow and velocity imaging in cardiovascular MRI. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(10):2172–2184. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2829-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotz J, Meier C, Leppert A, Galanski M. Cardiovascular flow measurement with phase-contrast MR imaging: basic facts and implementation. Radiographics. 2002;22(3):651–671. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma11651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tateshima S, Tanishita K, Omura H, Villablanca JP, Vinuela F. Intraaneurysmal hemodynamics during the growth of an unruptured aneurysm: in vitro study using longitudinal CT angiogram database. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(4):622–627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lotz J, Doker R, Noeske R, Schuttert M, Felix R, Galanski M, Gutberlet M, Meyer GP. In vitro validation of phase-contrast flow measurements at 3 T in comparison to 1.5 T: precision, accuracy, and signal-to-noise ratios. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21(5):604–610. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meaney JF, Goyen M. Recent advances in contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography. Eur Radiol. 2007;17(2):2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]