Introductory Paragraph

Variola major infection (Smallpox) claimed hundreds of millions lives before it was eradicated by a simple vaccination strategy: epicutaneous application of the related orthopoxvirus Vaccinia virus (VACV) to superficially injured skin (skin scarification, s.s.)1. However, the remarkable success of this strategy was attributed to the immunogenicity of VACV rather than the unique vaccine delivery mode. We now demonstrate that VACV immunization via s.s., but not conventional injection routes, is essential to the generation of superior T cell-mediated immune responses that provide complete protection against subsequent challenges, independent of neutralizing antibodies. Skin-resident effector memory T cells (TEM) provide complete protection against cutaneous challenge, while protection against lethal respiratory challenge requires both respiratory mucosal TEM and central memory T cells (TCM). Vaccination with recombinant VACV (rVACV) expressing a tumor antigen was protective against tumor challenge only if delivered via s.s. route, but not by hypodermic injection. Finally, the clinically safer non-replicative Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) also generated far superior protective immunity when delivered via s.s route compared to intramuscular injection used in MVA clinical trials. Thus, delivering rVACV -based vaccines, including MVA vaccines, through physically disrupted epidermis represents a uniquely powerful strategy with clear-cut advantages over conventional vaccination via hypodermic injection.

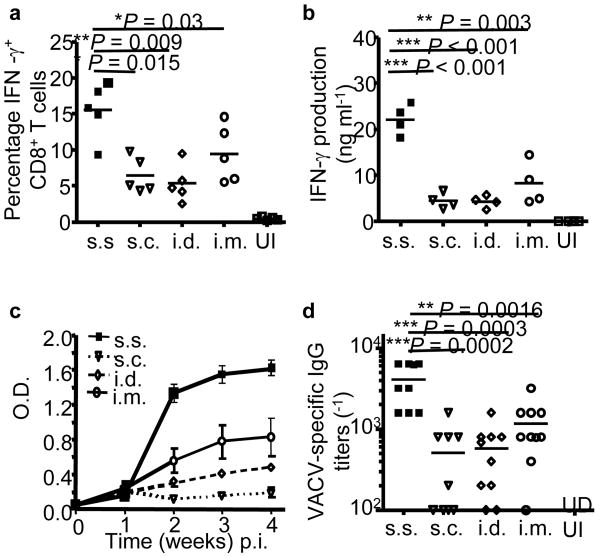

Smallpox was eradicated world-wide by immunization with VACV delivered to skin with a bifurcated needle, a process known as skin scarification (s.s.)1-3. We tested the hypothesis that rVACV immunization via s.s. is critical to the generation of superior protective immune responses. Using an established murine model of VACV s.s.4,5, we immunized C57BL/6 mice with rVACV by either s.s. or hypodermic injection routes. We showed that mice vaccinated by s.s. with rVACV generated more IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1a), a superior recall IFN-γ response (Fig. 1b) and superior humoral responses (Fig. 1c,d). We next immunized mice with rVACV by s.c. injection, with or without simultaneous epidermal disruption with a scarification needle (mock s.s.). Cellular and humoral responses were equivalent in these two groups, and were inferior to the rVACV-s.s. group (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b online). Heat-inactivated (Δ) rVACV delivered via s.s. also failed to induce significant cellular or antibody response (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d online). These data suggest that live VACV infection of disrupted epidermis is critical to superiority of s.s over other vaccination routes. We compared viral mRNA and protein expression following delivery of rVACV via s.s. and s.c routes. Despite equivalent initial viral loads (Supplementary Fig. 2a online), s.s resulted in significantly higher viral gene expression at the inoculation site (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c online). Epidermis and follicular epithelium were infected confluently after s.s., but not s.c. immunization (Supplementary Fig. 2c online), resulting in a higher available antigen dose.

Figure 1. Inoculation with rVACV via barrier-disrupted epidermis generates significantly stronger cellular and humoral responses compared to s.c., i.d. and i.m. injection.

(a) Quantification of the frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells in spleens on d 7 post immunization (p.i.) by intracellular IFN-γ staining. (b) Quantification of IFN-γ production from memory splenocytes at 5 weeks p.i. by in vitro restimulation assay. (c) Serum VACV-specific IgG determined by ELISA at the indicated time points p.i.. Each data point represents the average OD450nm value ± s.e.m. n = 5 in each group. (d) Serum VACV-specific IgG titer determined 11 weeks p.i.. n = 8–10 in each group. Data are representative results from 2–3 independent experiments. UI: unimmunized control.

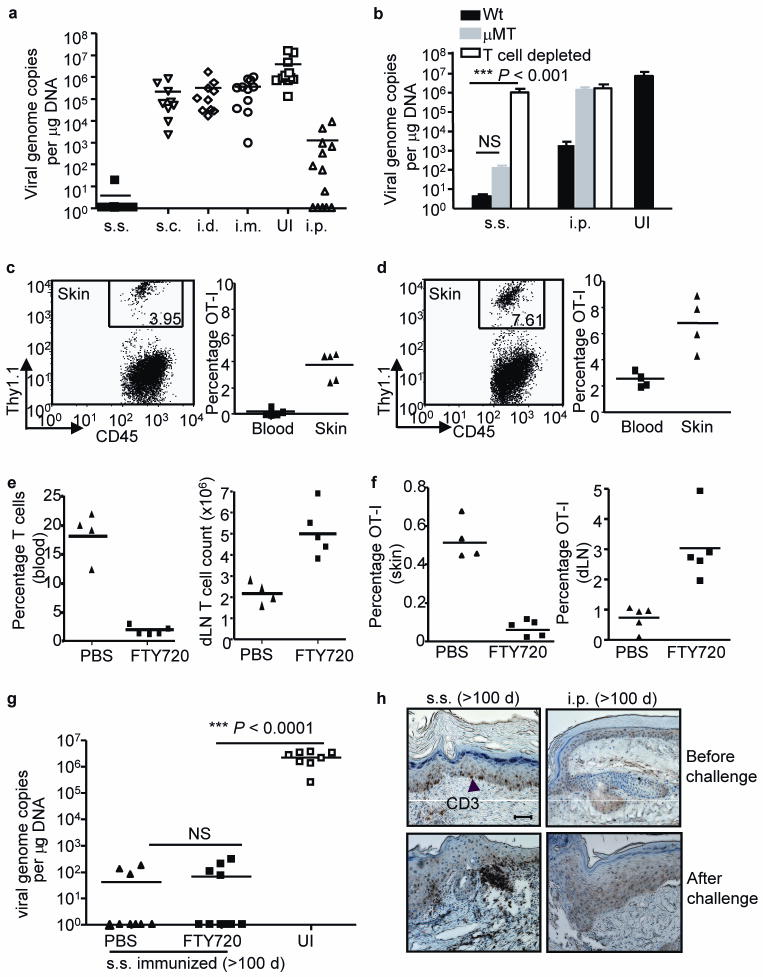

We recently showed that, following rVACV scarification, antigen-specific T cells are imprinted with skin-homing markers in draining lymph nodes (dLN) and rapidly migrate into infected skin4. We predicted that rVACV delivery via s.s. route would be highly protective against cutaneous challenge. Memory mice previously immunized with rVACV via different routes were challenged with a secondary rVACV infection to skin, and viral load at the challenge site was measured 6 d later. Mice immunized via s.s. had completely cleared virus from the infected site (> 6-log viral load reduction), while mice immunized by all other routes showed demonstratable but incomplete viral clearance (Fig. 2a). These data indicate that s.s. rVACV vaccination induces fundamentally superior protective immunity in skin.

Figure 2. rVACV scarification generates superior protective immunity against cutaneous viral challenge that is mediated by skin-targeted TEM.

(a, b) Skin viral load measured by real-time PCR on d 6 after cutaneous challenge of Wt or μMT immune mice (immunized with VACV 6 weeks prior to challenge). In some Wt memory mice, T cells were depleted before and during the challenge (b). Data is pooled results from 3 independent experiments. (c, d) The frequencies of OT-I T cells in CD45+ leukocyte population in skin and blood either before (c) or after (d) challenge. FACS plots were gated on CD45+ leukocyte populations in skin. Numbers on the plots represent the frequencies of OT-I T cells in CD45+ populations. (e) T cell frequency in blood and absolute number in dLN measured immediately before secondary challenge to assess the efficiency of FTY720 blockage of T cell egress from lymphoid tissues. (f) Frequencies of OT-I cells in total viable cell populations in skin tissue and dLN at d 4 after challenge. (g) Cutaneous viral load at d 6 after secondary challenge determined by real-time PCR. Data are pooled results from 2 independent experiments. (h) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining showing the presence of CD3+ T cells in skin tissue of s.s. or i.p. immunized mice before or after secondary cutaneous rVACV challenge. Scale bar represents 5 μm. Photographs shown are the representative of 9 slides from 3 mice per group.

The mode of protection against cutaneous challenge was distinct for i.p. and s.s. immunization. The moderate protection following i.p vaccination could be abrogated by T cell depletion and was entirely absent in antibody deficient μMT mice (Fig. 2b). However, the s.s– induced protection against skin challenge remained intact in μMT mice, and was significantly compromised only after T cell depletion (Fig. 2b). This is consistent with a significantly stronger recall T cell response following cutaneous challenge in s.s.-immunized mice compared to i.p.- immunized mice, in both normal and μMT mice (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). Therefore, T cell memory generated by rVACV s.s. immunization is both necessary and sufficient for the protection against cutaneous challenge.

We adoptively transferred OT-I transgenic T cells, specific for the Ovalbumin peptide SIINFEKL (Ova257–264), 1 d before immunization with an rVACV that expresses Ova257–264 under an early gene promoter6. OT-I cells were readily found in the skin of s.s. immunized memory mice, both prior to (Fig. 2c) and 4 d after (Fig. 2d) secondary cutaneous challenge, demonstrating efficient generation and recruitment of skin-homing TEM cells by s.s. route. We have reported previously that both VACV-specific TEM and TCM are generated after s.s. with rVACV4. We next asked whether the protective skin immunity in s.s. immunized mice was mediated by TEM already resident to skin before secondary challenge, or by newly activated TCM from LN. T cell egress from lymphoid tissues was blocked by treating mice prior to and during cutaneous challenge with FTY7207,8. FTY720 treatment induced pronounced lymphocytopenia via sequestration of lymphocytes in LN (Fig. 2e)7,8. Moreover, it led to a decrease of OT-I cells in skin and a concurrent accumulation of OT-I cells in dLN in cutaneously challenged mice (Fig. 2f). Despite this, viral clearance from skin was unaffected by FTY720 treatment (Fig. 2g). These results suggest that the skin-resident TEM generated by the original rVACV skin scarification are highly effective in the control of virus upon subsequent cutaneous challenge. Activation of TCM OT-I cells in dLN and their subsequent recruitment to skin after challenge was not required for the complete and rapid elimination of virus by 6 d. The importance of tissue resident TEM is supported by recent studies of HSV infection9,10. The efficient generation of skin-resident TEM population was only achieved by rVACV immunization via s.s. route, as increased numbers of CD3+ T cells in skin tissues of s.s. immunized mice, but not mice in the injection groups, were demonstrated histopathologically both before and after secondary cutaneous challenge (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 4 online). These observations explain the superior protection against cutaneous challenge afforded by rVACV s.s. immunization.

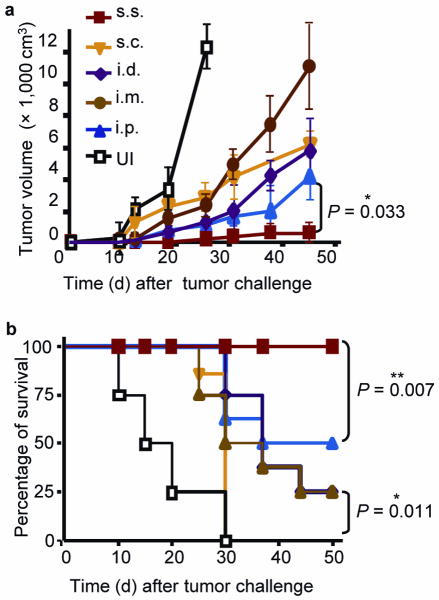

These data prompted us to evaluate the efficacy of rVACV scarification for protection against a tumor challenge in skin. Mice immunized with rVACV expressing OVA257–264 via different routes were inoculated intradermally with the OVA-expressing B16 melanoma cell line MO511. One week after MO5 implantation, tumor growth was evident at the injection site of unimmunized controls (Fig. 3a), all of which experienced rapid tumor growth and became moribund within 1 month (Fig. 3b). By 5 weeks after challenge, s.c.-immunized mice experienced 100% mortality, i.d.- and i.m.-immunized mice showed 75% mortality, and i.p.-immunized mice experienced 50% mortality (Fig. 3b), with all surviving animals harboring large tumors (Fig. 3a). In contrast, s.s.-immunized mice showed 100% survival by the end of the experiment (50 d after challenge) (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that rVACV immunization via s.s. is highly effective in generating skin-targeted memory T cells recognizing antigens on cutaneous tumors.

Figure 3. Immunization with rVACV via s.s. route provided superior protection against cutaneous melanoma challenge.

(a) Tumor volumes measured at the indicated time points after MO5 melanoma challenge of mice immunized with rVACV via various routes. Each data point represents the mean tumor volume of different groups. (b) Survival rate of mice after MO5 implantation. Data is the pooled results of two independent experiments. A total of 8 mice were used for each group in the two experiments.

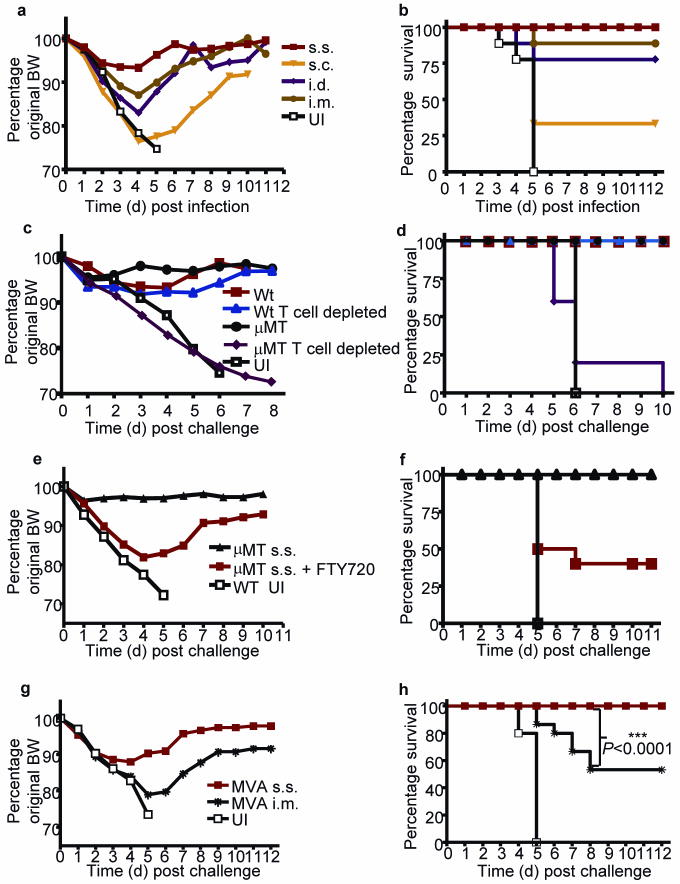

Smallpox, caused by Variola major virus, is transmitted primarily via respiratory droplets. To investigate how rVACV scarification also provides superior protection for respiratory tissues, we intranasally challenged rVACV memory mice, previously immunized by different routes, with lethal doses of pathogenic WR-VACV. Mice immunized via the s.c., i.d., or i.m. injection all showed significant weight loss after challenge, and were only partially protected from lethality (Fig. 4a,b). In contrast, mice immunized by s.s. not only survived, but were completely protected from clinical illness (as judged by absence of weight loss) (Fig. 4a,b). Vaccination via s.s. protected mice against the lethal respiratory challenge even at 3-log lower doses of rVACV vaccine (Supplementary Fig. 5 online).

Figure 4. Immunization with rVACV as well as non-replicative MVA via s.s. route is highly effective to protect mice against lethal respiratory WR-VACV challenge.

Change of body weight (BW) (a) and survival rate (b) of rVACV-immune Wt mice following lethal intranasal WR-VACV challenge. Change of BW (c) and survival rate (d) of rVACV s.s. immunized and WR-VACV challenged Wt or μMT mice, with or without T cell depletion at the time of challenge. Change of BW (e) and survival rate (f) of rVACV s.s. immune μMT mice following WR-VACV challenge, with or without FTY720 treatment. Change of BW (g) and survival rate (h) of MVA immune Wt mice following intranasal WR-VACV challenge. Immune mice were challenged with WR-VACV intranasally at 6 weeks (a–d, g,h) or 16 weeks (e,f) after immunization. Unimmunized (UI) controls were included in all the experiments. Data are representative results from 2–3 independent experiments (n = 10 per group).

We used μMT immune mice or Wt immune mice depleted of T cells to explore the mechanism of this protection against lethal intranasal challenge. After rVACV s.s. immunization, both μMT immune mice and T cell-depleted WT immune mice were fully protected from illness and death, indicating that either T cell memory or antibodies were sufficient to provide complete protection against this lethal challenge (Fig. 4c,d). Only T cell depletion in s.s. immunized μMT memory mice abrogated protection (Fig. 4c,d). FTY720-treated s.s. immunized μMT memory mice were partially protected against the lethality of the intranasal challenge (Fig. 4e,f and Supplementary Fig. 6). This suggests that protective TEM lining upper respiratory mucosa are generated by s.s. immunization. The different clinical outcome after intranasal challenge between μMT memory mice with and without FTY720 treatment suggests that activation of TCM in LN draining respiratory mucosa, and the subsequent recruitment of TEM to the respiratory tract, are essential for full protection against respiratory infectious challenge. Collectively, these data indicate that even in the complete absence of an antibody response, VACV-specific TCM and TEM together provide optimal protective immunity against lethal respiratory challenge in s.s. immunized mice.

Nationwide smallpox vaccination with VACV is precluded by an unacceptably high incidence of morbidity after vaccination, particularly in patients with atopic disorders12-18. The non-replicating MVA is an attractive alternative to VACV with an impressive safety profile19-22. MVA vaccines are typically delivered by i.m. injection. Skin scarification was not tested in MVA vaccination studies. We immunized C57BL/6 mice with MVA via s.s. This elicited cellular and humoral immune responses to VACV in a dose-dependent manner, and provided dose-dependent protection against lethal intranasal challenge with WR-VACV (Supplementary Fig. 7 online). Importantly, a single immunization with 2 × 106 plaque forming unit (pfu) MVA via s.s. route, but not i.m. injection, provided complete protection against morbidity and mortality in this model (Fig. 4g,h). This is consistent with the significantly stronger immune responses following MVA s.s. immunization (Supplementary Fig. 8 online).

Taken together, the data presented here establish that immunization with rVACV vaccines, including non-replicative strains, via superficially injured skin (i.e., s.s.), provides robust and anatomically flexible protection associated with a highly effective peripheral TEM and TCM response without requirement for neutralizing antibody. The mechanism by which s.s. is so much more effective than other immunization routes is incompletely understood. VACV infection of epidermal keratinocytes after s.s. may trigger cascade of pro-inflammatory molecule production23-25, as well as provide a higher dose of antigen, both of which may enhance the generation of optimal immunity. We hope that these insights will pave the way for the design of safe affordable and effective VACV-based immunization for infectious diseases and cancer.

Methods

Mice, viruses and infection

Animal work was in compliance with the guidelines set out by the Center for Animal Resources and Comparative Medicine at Harvard Medical School (HMS). C57BL/6 and μMT mice were from Jackson Laboratory. We bred Thy1.1+ OT-I Rag1−/− mice in a HMS animal facility. We expanded and titered rVACV expressing both EGFP and OT-I T cell epitope OVA257–2646, and WR-VACV stocks, by standard procedures26. We immunized mice with 2 × 106 pfu VACV or MVA (ACAM3000MVA) via indicated routes. We performed s.s. as previously described 4. At the indicated time points, we challenged mice either cutaneously with rVACV (2 × 106 pfu), or intranasally with WR-VACV (2 × 106 pfu). Mice that had lost over 25% of original BW were euthanized.

Intracellular cytokine staining

To prepare target cells, we infected naïve C57BL/6 splenocytes with rVACV at multiplicity of infection of 5 for 8 h followed by 3 washes. We incubated splenocytes from immunized and control animals with target cells (1:1 ratio) in 96-well plate for 6 h in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Pharmingen), and subsequently performed surface and intracellular staining with Cytoperm/Cytofix kit (BD Pharmingen) according to manufacturer's protocol. We used antibodies to mouse CD16/32 (2.4G2), CD3e- FITC (145-2C11), CD8α-PerCP (53-6.7), IFN-γ-PE (XMG1.2) and IFN-γ-isotype control. We analyzed samples on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Data analysis was performed using Flowjo software (Tree Star).

In vitro restimulation assay

We cultured target cells (prepared as described above) with splenocytes or ILN cells from immune or control mice (1:1 ratio) in 96-well plate for 48 h. We measured IFN-γ concentration in the supernatant by ELISA using monoclonal antibody pairs to IFN-γ (BD Pharmingen), according to manufacturer's instruction.

ELISA for serum Vaccinia- specific antibody

We coated ELISA plates with rVACV-infected Hela cell lysate at 4 °C overnight, blocked the plates with PBS containing 10% FCS and 0.1% Tween-20 for 2 h, then added serum sample dilutions and incubated the plates at 4 °C for 1 h. Antibody was detected with horseradish peroxidase- conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotech) and TMB substrate reagent (BD Pharmingen). We determined A450 with a Vmax Spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices), and calculated end-point titers as the highest dilution with an absorbance value > 0.10 after subtraction of background wells assayed without antigen.

Determination of cutaneous viral load

We determined skin viral load by real-time PCR, as previously described 4.

In vivo depletion of T cells

We injected mice i.p. with antibody to mouse CD8 (clone 2.43, 0.5 mg) and mouse CD4 (clone GK1.5, 0.5 mg) on d -2, 0, 4 and 8 with respect to secondary challenge. This regimen depleted >99% of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (data not shown).

Adoptive transfer and detection of OT-I cells in skin

2 × 105 OT-I cells from Thy1.1+ OT-I Rag1−/− mice were intravenously injected into Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 mice 1 d before rVACV s.s. on ear skin (2 × 106 pfu). We challenged mice with 2 × 106 pfu rVACV on ear 6 weeks p.i., and harvested ears and blood samples either before challenge or 4 d after challenge. We separated ears into dorsal and ventral halves, and incubated them in HBSS containing 1 mg ml-1 collagenase A and 40 ug ml-1 DNase I (Roche Diagnostics) at 37°C for 2 h. We then added HBSS containing 2 mM EDTA and 5% FCS to stop the digestion. After filtering cell suspension through 70-micron cell strainers and red cell removal, we stained cells with CD45.2-PE (104) and Thy1.1-PerCP (OX-7) (BD Pharmingen) for flow cytometry analysis.

FTY720 treatment

16 weeks after rVACV s.s. immunization, we i.p. injected memory mice daily with 1mg kg-FTY720 (2-amino-2-(2[4-octylphenyl]ethyl)-1,3-propanediol hydrochloride, provided by V. Brinkmann at Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland), or PBS (mock control). After 1–2 doses, the mice were challenged cutaneously or intranasally.

IHC staining for T cells in skin

We challenged Wt mice immunized with rVACV via s.s. or i.p. route on tail skin at 15 weeks after immunization. Challenged skin tissues were harvested either 1 d before or 4 d after challenge. Sectioning and IHC staining of skin samples for CD3+ T cell detection was performed as previously described4. We obtained images with a Nikon E600 microscope and a Nikon EDX-35 digital camera.

Tumor challenge

6 weeks following rVACV immunization, we intradermally challenged memory and control naïve mice with 3 × 105 MO5 cells, an ovalbumin gene-transfected B16 melanoma cell line 11. We measured the longest diameter (L) and the perpendicular diameter (W) of the local tumor at the indicated time points. Tumor volume = 4πW2L/3.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical comparisons with two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test, Mann-Whitney test (for viral load data), and Log rank test (for survival curves) using Prism software. We used area under curve to compare weight loss between groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Moss (US National Institute of Health (NIH)) for provision of rVACV expressing EGFP and OT-I T cell epitope OVA257–264, as well as WR-VACV, K. Rock (University of Massachusetts Medical School) for provision of MO5 cell line, M. Seaman (Beth Israel hospital) for provision of MVA stocks. We also thank R. C. Fuhlbrigge for administrative support, E. Reinherz for his critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH / US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grants R01 AI042124 and R37 AI025082 to T.S.K., and NIH grant U19AI57330 subcontracted to T.S.K.; a Dermatology Foundation Research Career Development Award to L. L., a Career Development Award and a New Opportunities Grant to L. L. from NIAID / New England Regional Center of Excellence / Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Disease (AI057159).

References

- 1.Stewart AJ, Devlin PM. The history of the smallpox vaccine. J Infect. 2006;52:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammarlund E, et al. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nat Med. 2003;9:1131–1137. doi: 10.1038/nm917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demkowicz WE, Jr, Littaua RA, Wang J, Ennis FA. Human cytotoxic T-cell memory: long-lived responses to vaccinia virus. J Virol. 1996;70:2627–2631. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2627-2631.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L, Fuhlbrigge RC, Karibian K, Tian T, Kupper TS. Dynamic programming of CD8+ T cell trafficking after live viral immunization. Immunity. 2006;25:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian T, et al. Overexpression of IL-1alpha in skin differentially modulates the immune response to scarification with vaccinia virus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:70–78. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norbury CC, Malide D, Gibbs JS, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Visualizing priming of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by infected dendritic cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:265–271. doi: 10.1038/ni762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matloubian M, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinschewer DD, et al. FTY720 immunosuppression impairs effector T cell peripheral homing without affecting induction, expansion, and memory. J Immunol. 2000;164:5761–5770. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gebhardt T, et al. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:524–530. doi: 10.1038/ni.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodland DL, Kohlmeier JE. Migration, maintenance and recall of memory T cells in peripheral tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:153–161. doi: 10.1038/nri2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falo LD, Jr, Kovacsovics-Bankowski M, Thompson K, Rock KL. Targeting antigen into the phagocytic pathway in vivo induces protective tumour immunity. Nat Med. 1995;1:649–653. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neff JM, Lane JM. Vaccinia necrosum following smallpox vaccination for chronic herpetic ulcers. JAMA. 1970;213:123–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neff JM, et al. Complications of smallpox vaccination. I. National survey in the United States, 1963. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:125–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196701192760301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neff JM, et al. Complications of smallpox vaccination United States 1963. II. Results obtained by four statewide surveys. Pediatrics. 1967;39:916–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bray M. Pathogenesis and potential antiviral therapy of complications of smallpox vaccination. Antiviral Res. 2003;58:101–114. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bray M, Wright ME. Progressive vaccinia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:766–774. doi: 10.1086/374244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vora S, et al. Severe eczema vaccinatum in a household contact of a smallpox vaccinee. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1555–1561. doi: 10.1086/587668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell MD, et al. Cytokine milieu of atopic dermatitis skin subverts the innate immune response to vaccinia virus. Immunity. 2006;24:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy JS, Greenberg RN. IMVAMUNE: modified vaccinia Ankara strain as an attenuated smallpox vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:13–24. doi: 10.1586/14760584.8.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drexler I, Staib C, Sutter G. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara as antigen delivery system: how can we best use its potential? Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2004;15:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parrino J, et al. Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) against Dryvax challenge in vaccinia-naive and vaccinia-immune individuals. Vaccine. 2007;25:1513–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.10.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phelps AL, Gates AJ, Hillier M, Eastaugh L, Ulaeto DO. Comparative efficacy of modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) as a potential replacement smallpox vaccine. Vaccine. 2007;25:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. Immune surveillance in the skin: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:211–222. doi: 10.1038/nri1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kupper TS, Groves RW. The interleukin-1 axis and cutaneous inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:62S–66S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12316087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Partidos CD, Muller S. Decision-making at the surface of the intact or barrier disrupted skin: potential applications for vaccination or therapy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1418–1424. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4529-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Earl PL, Cooper N, Wyatt LS, Moss B, Carroll MW. Preparation of Cell Cultures and Vaccinia Virus Stocks. In: Ausubel FM, et al., editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 1998. pp. 16.16.14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.