Abstract

In the lungs, parasympathetic nerves provide the dominant control of airway smooth muscle with release of acetylcholine onto M3 muscarinic receptors. Treatment of airway disease with anticholinergic drugs that block muscarinic receptors began over 2000 years ago. Pharmacologic data all indicated that antimuscarinic drugs should be highly effective in asthma but clinical results were mixed. Thus, with the discovery of effective β-adrenergic receptor agonists the use of muscarinic antagonists declined. Lack of effectiveness of muscarinic antagonists is due to a variety of factors including unwanted side effects (ranging from dry mouth to coma) and the discovery of additional muscarinic receptor subtypes in the lungs with sometimes competing effects. Perhaps the most important problem is ineffective dosing due to poorly understood differences between routes of administration and no effective way of testing whether antagonists block receptors stimulated physiologically by acetylcholine. Newer muscarinic receptor antagonists are being developed that address the problems of side effects and receptor selectivity that appear to be quite promising in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is part of a themed issue on Respiratory Pharmacology. To view the other articles in this issue visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2011.163.issue-1

Keywords: M2 muscarinic receptors, airway hyperreactivity, ipratropium, tiotropium, aclidinium, glycopyrrolate, CHF 5407

Muscarinic receptors in the lung

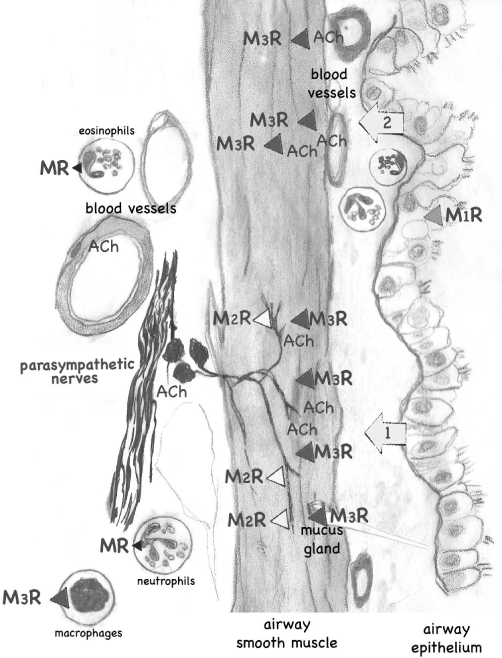

In the lungs, anticholinergic compounds block muscarinic receptors on airway smooth muscle, glands and nerves to prevent muscle contraction, gland secretion and enhance neurotransmitter release. There are five muscarinic receptor subtypes [designated M1 through M5 by the IUPHAR (Caulfield and Birdsall, 1998)] all belonging to the large family of seven transmembrane G-protein coupled receptors. In human lung (and in all animal species tested), acetylcholine induces bronchoconstriction by stimulating M3 (Figure 1) receptors on smooth muscle (Roffel et al., 1990). Although airway smooth muscle contraction is mediated by M3 receptors, the majority of muscarinic receptors on airway smooth muscle are actually M2 (Barnes, 1993). These M2 receptors contribute indirectly to airway smooth muscle contraction by limiting β-adrenoceptor-medicated relaxation through inhibition of adenylate cyclase (Fernandes et al., 1992). Glandular secretion is also mediated predominantly by M3 muscarinic receptors on submucosal cells (Marin et al., 1976; Borson et al., 1980; Phillips et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Muscarinic receptors in lungs. Muscarinic receptors (MR) are present throughout the lungs and control smooth muscle contraction, gland secretion, acetylcholine (ACh) release from parasympathetic nerves and probably also inflammatory cells. Only receptors with dominant physiological effects are shown, thus for example M2 receptors in airway smooth muscle are not included. The major physiological source of ACh is from postganglionic parasympathetic nerves that supply both muscle and glands (1); ACh release is normally limited by M2 receptors on these nerves. However, muscarinic receptors are distributed throughout smooth muscle and can be stimulated by exogenous acetylcholine administered i.v. or by inhalation (2). References are found in the text.

Muscarinic receptors are also present on parasympathetic nerves supplying the lungs (Fryer and Maclagan, 1984). M2 muscarinic receptors on postganglionic parasympathetic nerves (Faulkner et al., 1986; Fryer et al., 1996) limit acetylcholine release, thus providing a physiologically relevant, negative feedback control over acetylcholine release (Fryer and Maclagan, 1984; Baker et al., 1992). Blocking M2 receptors with muscarinic antagonists including atropine and ipratropium or using selective M2 receptor antagonists such as gallamine, significantly potentiates vagally induced bronchoconstriction (Fryer and Maclagan, 1984; 1987; Blaber et al., 1985; Faulkner et al., 1986). Neuronal M2 receptors are vulnerable, and thus their function is significantly decreased after respiratory viral infection, antigen challenge, or exposure to organophosphates or ozone (Empey et al., 1976; Aquilina et al., 1980; Fryer and Jacoby, 1991; Schultheis, 1992; Schultheis et al., 1994; Sorkness et al., 1994). They are also less functional in humans with asthma (Minette et al., 1989). Decreased function of the neuronal M2 receptors is mediated by various mechanisms including blockade by endogenous antagonists and down-regulation of receptor expression. The resulting increase in acetylcholine release is thought to be an important mechanism of airway hyperreactivity.

Clinically, anticholinergic drugs are used as bronchodilators in combination with anti-inflammatory steroids in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Asthma is characterized by variable airflow limitation that is partially reversible spontaneously or with treatment. Underlying this airflow limitation is chronic inflammation that increases airway hyperresponsiveness to various stimuli (EPR-3, 2007). COPD is characterized by chronic airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. Patients with COPD can experience acute worsening in symptoms. These exacerbations are characterized by increased sputum production and shortness of breath (Rabe et al., 2007). COPD and asthma symptoms overlap; however, the most distinguishing difference between conditions is airflow limitation reversibility. This review covers the history of clinically relevant anticholinergic drugs in asthma and COPD.

Atropine and related compounds

Muscarinic receptor blockade is one of the oldest treatments for asthma. Traditional medicine used the naturally occurring anticholinergic alkaloids atropine and scopolamine for centuries. Ancient Egyptians with airway disease reportedly placed a distillate of henbane, Hyoscyamus, on fired bricks and inhaled the smoke (Ebell, 1937; Ellul-Micallef, 1997). In Europe, during the Middle Ages, the source of atropine was the deadly nightshade shrub. This plant was also used as poison, prompting Linnaeus to name it Atropa belladonna after Atropos, the Fate that cuts the thread of life (Goodman et al., 2006). In the 19th century, atropine (Figure 2) was isolated from deadly nightshade, datura and jimsonweed in pure form and used in Western medicine.

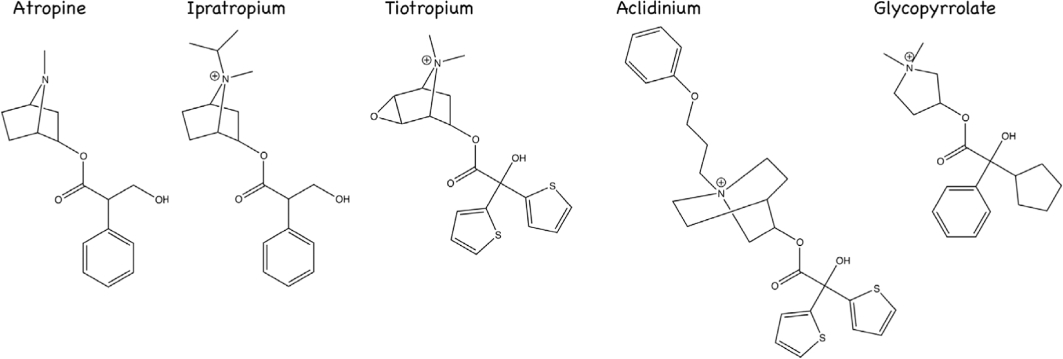

Figure 2.

Anticholinergic drugs in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In both animal and human studies, atropine reverses, in a dose-dependent manner, bronchoconstriction induced by stimulation of parasympathetic nerves or induced by intravenous or inhaled acetylcholine (Cavanaugh and Cooper, 1976; Sheppard et al., 1982; Holtzman et al., 1983), suggesting that anticholinergic drugs would be efficacious in asthma. Here we will discuss why atropine or other anticholinergic medications are not the first line of treatment for airway disease, currently.

The potency of atropine as a bronchodilator depends upon route of administration (Holtzman et al., 1983; Sheppard et al., 1983). It requires more intravenous than inhaled atropine to block bronchoconstriction regardless of whether bronchoconstriction was induced by intravenous acetylcholine or by vagal stimulation (Holtzman et al., 1983). Atropine's potency in asthma is also dependent upon the route of administration. Regardless of whether bronchoconstriction is induced by inhaled methacholine or by vagal reflex (initiated by cold dry air), inhaled atropine is a more effective inhibitor of bronchoconstriction than intravenous atropine (Sheppard et al., 1983). These data might suggest that inhaled atropine would be an ideal bronchodilator. However, and this is an important point of these studies, inhaled atropine is significantly more potent blocking bronchoconstriction induced by inhaled acetylcholine than blocking bronchoconstriction induced by vagal stimulation (Holtzman et al., 1983).

The method used to identify a clinically effective dose of atropine (the dose of any anticholinergic drug that blocks bronchoconstriction induced by inhaled acetylcholine) is significantly less than the dose of atropine required to block the physiological source of acetylcholine, which is the parasympathetic nerves. These experiments in dogs and asthmatic humans demonstrate the dose of inhaled atropine is too low to block vagally released acetylcholine.

The lack of effectiveness of atropine (and other anticholinergic drugs) in asthma has been used to suggest that increased release of acetylcholine from the parasympathetic does not contribute to hyperreactivity in asthma. However, it is much more likely the clinical dose of atropine is too low. Pharmacologically, 0.67 mg·kg−1 (47 mg in a 70 kg adult) of systemic atropine are needed to block 50% of muscarinic receptors in the lungs (Chen et al., 1981). For asystolic arrest the highest clinical dose currently used is 3 mg i.v. per adult (ACC/AHA, 2005). The LD50 for atropine is 453 mg per adult; however, 10–20 mg per adult is incapacitating (Goodman, 2010). Thus, the pharmacologically effective dose range for atropine is very close to the toxic range.

Further complicating the dose of atropine is the presence of multiple muscarinic receptor subtypes, including neuronal M2 receptors on parasympathetic nerves supplying the lungs. Under physiological conditions, these neuronal M2 receptors inhibit acetylcholine release, and limit vagally mediated bronchoconstriction (Fryer and Maclagan, 1984; 1987; Minette and Barnes, 1988). In guinea pigs, atropine blocks neuronal M2 receptors and enhances acetylcholine release at doses that have little inhibitory effect on post junctional M3 receptors (Fryer and Maclagan, 1987). Additionally, in humans, atropine has a complex dose–response curve due to the presence of different muscarinic receptor subtypes (Wellstein and Pitschner, 1988).

Atropine is orally absorbed and undergoes first-order kinetics to eliminate the drug (Hinderling et al., 1985a,b;). Twenty-four hours after administration, one-fourth to one-third of orally administered atropine is present in urine as a pharmacologically active drug (Kalser, 1971). Systemic side effects of atropine include dry mouth and urinary retention. Atropine also crosses the blood-brain barrier and placenta (Mirakhur, 1978; Proakis and Harris, 1978). It is this ability to penetrate the central nervous system that leads to high fever, hallucinations and coma with higher doses. Although the World Health Organization lists atropine as a core, essential medicine, its therapeutic use is limited to treatment of life-threatening arrhythmias and toxic prodromes due to these multiple, severe, side effects (WHO, 2010). These toxicities severely limit the dose of atropine that can be used clinically. For these reasons there was a push to develop an anticholinergic drug that was less well absorbed to limit toxic side effects.

Ipratropium

Ipratropium bromide (Figure 2) is a synthetic quaternary ammonium compound with an isopropyl group at the N atom of atropine. This quaternary ammonium functions to limit systemic availability to 6.9% when ipratropium is inhaled and limits availability to 2% when taken orally (Ensing et al., 1989). Ipratropium's poor absorption means that it targets muscarinic receptors in the lung when given by inhalation, without the systemic side effects of atropine (Cugell, 1986; Gross, 1988; Goodman et al., 2006). For example, inhaled ipratropium does not affect resting heart rate. The low oral absorption is also important, as approximately 90% of an aerosolized dose is likely swallowed (Davies, 1975; Cugell, 1986). The half-life of ipratropium is 3.2 to 3.8 h regardless of route of administration (Pakes et al., 1980). Onset of action for a >15% increase in forced expiratory volume in 1 s, a measure of airflow limitation, was <15 min, with a peak onset at 1–2 h and duration of action 5 h (Gunther and Kamburoff, 1974; Tashkin et al., 1986).

Ipratropium came into prominent clinic use for COPD in the early 1980s. Part of this use may be because of the relative ineffectiveness of other bronchodilator therapy in COPD. Specifically, β-agonists become less effective with continued use in COPD (Donohue et al., 2003).

However, ipratropium shares the same problem with atropine regarding dose. The FDA limited doses to 18 µg per puff largely due to concerns about potential anticholinergic side effects. Given that the maximal dilating dose of ipratropium is 500 µg, the current recommended dose of 36 µg is suboptimal in COPD patients (Ward et al., 1981; Gross et al., 1989). Side effects for ipratropium are generally mild with dry mouth and occasional cough most commonly reported. As with β-agonists there is no evidence that regular ipratropium use slows the rate of lung function decline in COPD (Anthonisen et al., 1994).

Ipratropium is less effective in bronchodilation compared to β-agonists (Ruffin et al., 1977). Again, concern for potential side effects limited using a higher dose, thus limiting the bronchodilation. In comparison, acute asthma showed improved outcomes with the addition of ipratropium, to β-agonists, with more rapid and greater improvement in lung function (Rebuck et al., 1987; Stoodley et al., 1999; Rodrigo and Rodrigo, 2000; Rodrigo and Castro-Rodriguez, 2005). However, dosing for acute asthma averaged 504 µg ipratropium per hour and again emphasizes that when ipratropium is used in doses approaching the maximal dilating dose, the bronchodilation is clinically significant (Gross et al., 1989; Rodrigo and Rodrigo, 2000). Current expert opinion now recommends ipratropium for acute severe asthma exacerbations (EPR-3, 2007) at the higher dosing.

However, ipratropium blocks all muscarinic receptor subtypes with equal affinity, including the inhibitory neuronal M2 receptors (Fryer and Maclagan, 1987; Restrepo, 2007). It is via blockade of these neuronal receptors that ipratropium is capable of potentiating vagally induced bronchoconstriction, and this effect is seen at doses that are close to those used clinically (Fryer and Maclagan, 1987). Humans with asthma already have reduced M2 function (Ayala and Ahmed, 1989; Minette et al., 1989), thus to spare additional blockade of neuronal receptors, anticholinergic drugs that are selective for M3 receptors were developed.

Tiotropium

Tiotropium bromide monohydrate is the first anticholinergic drug ever that is effective in treatment of poorly controlled asthma (Peters et al., 2010). This trial showed tiotropium bromide in combination with corticosteroids was more effective than corticosteroids alone and equally effective as corticosteroids in combination with salbutamol, a long-acting beta receptor agonist. Tiotropium is structurally related to ipratropium bromide (Figure 2), but it has a significantly higher affinity for muscarinic receptors (Haddad et al., 1994). Tiotropium has similar affinity for all muscarinic receptor subtypes; however, unlike ipratropium, tiotropium is functionally selective for M3 receptors. This selectivity is provided by the ability of tiotropium to dissociate from M2 receptors 10 times faster than it does from M3 receptors (T1/2 3.6 h for M2 vs. T1/2 34.7 h for M3) (Disse et al., 1993). It has even been suggested that in the lungs, tiotropium is a kinetically irreversible antagonist at M3 muscarinic receptors (Swinney, 2004). This functional muscarinic receptor selectivity is likely related to the two thiophene rings that are a part of tiotropium's structure (Price et al., 2009). Tiotropium has 2–3% bioavailability when taken orally. When inhaled, 80% of tiotropium is swallowed with 19.5% reaching the lung, which is almost entirely bioavailable. Clearance of tiotropium is primarily renal with 14% of an inhaled dose excreted unchanged in the urine with active renal secretion of tiotropium (Price et al., 2009). The advantage of low oral bioavailability and increased renal clearance is fewer systemic side effects.

The prolonged duration of action, higher affinity and functional selectivity of tiotropium for M3 receptors produces greater improvement in airflow limitation when compared to ipratropium (Vincken et al., 2002; Brusasco et al., 2003). Extended half-life of tiotropium allows once daily dosing with subsequent doses progressively increasing efficacy up to 1 week after starting tiotropium (Disse et al., 1993; Haddad et al., 1994; Maesen et al., 1995; Barnes, 2001; Casaburi et al., 2002; Restrepo, 2007). This combination of functional selectivity and extended half-life overcomes many of the drawbacks of ipratropium, including the need for frequent dosing and confounding effects of M2 receptor blockade, and may explain improved outcomes of tiotropium compared with ipratropium in COPD (Casaburi et al., 2002; Vincken et al., 2002; Brusasco et al., 2003).

Asthma is associated with decreased neuronal M2 receptor function leading to increased acetylcholine release (Ayala and Ahmed, 1989; Minette et al., 1989). Tiotropium more rapidly dissociates from M2 receptors than from M3 receptors sparing additional inhibition of neuronal M2 receptors. Thus, unlike other cholinergic antagonists (Fryer and Maclagan, 1987), tiotropium, by not exacerbating acetylcholine release from parasympathetic nerves (Takahashi et al., 1994), further improves bronchodilation.

However, as with all muscarinic antagonists dosing of tiotropium may still be inadequate for treatment of stable asthma. As described above for atropine and ipratropium, dose was determined by the ability of tiotropium to inhibit bronchoconstriction induced by inhaled methacholine and bronchoconstriction induced by i.v. acetylcholine but not vagally induced bronchoconstriction (Barnes et al., 1995; O'Connor et al., 1996; Buels et al., 2010). As with other antimuscarinic drugs 18 µg dose was chosen to limit systemic side effects and not to induce maximal bronchodilation, (Littner et al., 2000) and thus there is potential for under dosing of tiotropium.

In humans tiotropium significantly delayed and reduced COPD exacerbations including hospitalizations for exacerbations (Tashkin et al., 2008). Increased mucus production is a hallmark of COPD exacerbations. Stimulation of muscarinic receptors on epithelial cells promotes cell proliferation, cell survival and mucociliary clearance in vitro (Acevedo, 1994; Wessler and Kirkpatrick, 2001; Klein et al., 2009). The role of muscarinic receptors in mucociliary clearance is complex. Mucus glands express M1 and M3 receptors while acetylcholine release from nerves supplying these glands is limited by neuronal M2 receptors. Epithelial cells express M1, M2 and M3 receptors (Acevedo, 1994; Wessler and Kirkpatrick, 2001; Klein et al., 2009). Stimulation of M3 muscarinic receptors increases serous secretions and increases mucociliary beat frequency while M2 receptors inhibit mucociliary beat frequency and decrease particle transport (Klein et al., 2009). The balance of effects of these muscarinic receptors is not fully understood either under physiological or pathological conditions, but does provide opportunity to manipulate secretions with selective muscarinic antagonists. Therefore, as tiotropium has greater affinity for M3 than M1 and M2 receptors this may explain the reduced exacerbations in COPD (Disse et al., 1999; Tashkin et al., 2008).

Tiotropium was also significantly better than ipratropium in reducing COPD exacerbations when combined with corticosteroids (Tashkin et al., 2008). In antigen challenged animals, tiotropium reduces bronchoconstriction independently of the bronchodilator effects (Buels et al., 2010). This increase effect of tiotropium may result from its anti-inflammatory properties. Muscarinic receptors are found on inflammatory cells in lungs including mast cells (M1), macrophages (M3), neutrophils (M4/M5) and eosinophils (M3/M4) (Mak and Barnes, 1989; Reinheimer et al., 1997; Bany et al., 1999; Verbout et al., 2006). Acetylcholine increases chemotactic mediator leukotriene B4 thereby increasing neutrophil migration. Tiotropium blocks neutrophil migration demonstrating a role for acetylcholine and muscarinic receptors in inflammation (Buhling et al., 2007). Tiotropium reduces airway remodelling that results from prolonged inflammation in allergic guinea pigs (Bos et al., 2007). Severe asthmatic patients responded better to tiotropium than to inhaled corticosteroids further suggesting that tiotropium has anti-inflammatory effects in asthma and COPD (Tashkin et al., 2008; Peters et al., 2010).

Aclidinium bromide

Aclidinium bromide (Figure 2) is an anticholinergic drug similar to tiotropium in that it also has two thiophene rings and quaternary ammonium group (Norman, 2006; Prat et al., 2009). Also similar to tiotropium, aclidinium has kinetic selectivity for M3 receptors versus M2 receptors. Although the half-life of aclidinium at muscarinic receptors in guinea pig lung is 29 h, which is shorter than 34 h for tiotropium, the onset of action is significantly faster (Gavalda et al., 2009). Unlike tiotropium however, aclidinium is rapidly metabolized in the plasma resulting in an extremely short half-life in circulation (2.4 min). This rapid metabolism limits systemic, and central nervous system side effects in animal studies (Gavalda et al., 2009). Early clinical trials appear to confirm a lack of systemic effects (Joos et al., 2010; Schelfhout et al., 2010a), which would allow for higher dosing without the concern for toxic effects that limited earlier use of muscarinic receptor antagonists. Phase I studies in normal patients and in COPD patients showed a 23.3% improvement in airflow limitation 2 h post administration of 300 µg, with sustained bronchodilation over lasting 24 h with once daily dosing (Joos et al., 2010; Schelfhout et al., 2010b). A phase III clinical trial for aclidinium is currently ongoing.

Glycopyrrolate

Glycopyrrolate (Figure 2) has been used in surgery to mitigate the side effects, most notably bradycardia and increased saliva production, of paralytic reversal with neostigmine. Glycopyrrolate is slightly selective for M3 muscarinic receptors with affinity at M3 receptors being 3–5 times higher than that at M1 and M2 receptors (Haddad et al., 1999); however, unlike tiotropium and aclidinium, glycopyrrolate does not have kinetic selectivity. Glycopyrrolate is currently undergoing phase III trials in COPD (Norman, 2006). A phase II trial shows that 0.5 mg dose of nebulized glycopyrrolate prevented inhaled methacholine-induced bronchospasm 30 h later (Hansel et al., 2005). However, as discussed above with atropine and tiotropium (Holtzman et al., 1983; Sheppard et al., 1983; O'Connor et al., 1996), blocking bronchoconstriction induced by inhaled muscarinic agonists may result in choosing an antagonist dose that is too small to adequately block vagally induced bronchoconstriction (Sheppard et al., 1982; 1983; Holtzman et al., 1983). Accordingly, although glycopyrrolate blocks methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction there is no improvement in bronchoconstriction during acute asthma exacerbations or COPD exacerbations (Cydulka and Emerman, 1994; 1995; Hansel et al., 2005).

Other muscarinic receptor antagonists

Additional long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists are being developed. These include OrM3 and CHF 5407. OrM3's affinity for M3 receptors is 120 times greater than its affinity for M2 receptors (Table 1). It was formulated in tablets to allow for oral dosing for those patients who had difficulty using inhaled medications. Unfortunately, it was less effective than ipratropium with increased side effects; most notably dry mouth (Lu et al., 2006). CHF 5407 appears more promising. Early trials show it is as potent and long-acting antagonist of M3 receptors as tiotropium (with 54% still bound to M3 receptors at 32 h) with a significantly shorter half-life at M2 receptors (21 min for CHF 5407 vs. 297 min for tiotropium)(Peretto et al., 2007a,b; Cazzola and Matera, 2008). Studies are currently ongoing to determine the clinical effectiveness of CHF 5407.

Table 1.

Muscarinic receptor (MR) antagonists and properties

| MR affinity at M3 receptor (pKi) | M3 > M2 affinity | Half-life at M3 receptors (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atropine | 9.681 | None1 | 3.57 |

| Ipratropium | 9.581 | None1 | 3.28 |

| Tiotropium | 11.021 | Functional selectivity4 | 34.74 |

| Glycopyrrolate | 10.041 | 3–5× more selective5 | 3.75 |

| Aclidinium | 10.741 | Functional selectivity6 | 296 |

| OrM3 | 9.382 | 120× more selective2 | 14.22 |

| CHF 5407 | 9.233 | Functional selectivity3 | ∼323 |

pKi determined in heterologous competition experiments against [N-Methyl-3H]scopolamine methyl chloride ([3H]NMS).

Formulation of muscarinic receptor antagonists

Inhalation of muscarinic antagonists may not provide optimal delivery of drug to the relevant areas of the lung. Currently anticholinergic drugs are delivered using pressurized metered dose inhaler, dry powder inhalers and a portable nebulizer. These methods result in greater delivery to the lungs versus gastrointestinal tract and different patterns of lung deposition. However, there is no difference in efficacy or side effects of ipratropium or tiotropium with the different inhalers (Vincken et al., 2004; van Noord et al., 2009; Ichinose et al., 2010). Therefore, pharmacology, including receptor selectivity, of muscarinic receptor antagonists is more important than delivery methods to improving clinical efficacy of newer generation muscarinic receptor antagonists.

Conclusion

Rationally, blocking M3 receptors on airway smooth muscle should inhibit bronchoconstriction. However, while anticholinergic drugs are useful in the laboratory setting, their ability to block bronchoconstriction clinically in humans with asthma and COPD has been mired with problems surrounding efficacious dosing, side effects and muscarinic receptor selectivity. Each generation of muscarinic antagonists are less well absorbed, more selective, longer acting and, most recently, more readily metabolized. None however, have yet addressed the issue of adequate dosing, and whether antagonists given at concentrations that will inhibit inhaled acetylcholine or methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction will be sufficient to also inhibit bronchoconstriction induced by acetylcholine released from the vagus nerves; the physiological source of acetylcholine in the lungs. Increased acetylcholine is a mechanism of airway hyperreactivity in asthma (Holtzman et al., 1980; Nadel and Barnes, 1984; Minette and Barnes, 1988; Evans et al., 1997; Costello et al., 1999; Yost et al., 1999). Thus, it remains to be seen whether anticholinergic drugs can reach the relevant M3 receptors in lungs in vivo, and be delivered in pharmacologically effective concentrations, and produce bronchodilation without toxic side effects.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- IUPHAR

International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology

- LD50

lethal dose for 50% of population

- M1–M5

muscarinic receptor subtypes 1–5

Conflicts of interest

Dr Fryer currently has these grants from the National Institutes of Health: RO1 HL55543, RO1 ES014601, RO1 ES017592.

Supporting Information

Teaching Materials; Figs 1–2 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- ACC/AHA. 2005 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2005;112(24) Suppl:IV1–203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo M. Effect of acetyl choline on ion transport in sheep tracheal epithelium. Pflugers Arch. 1994;427:543–546. doi: 10.1007/BF00374272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA. 1994;272:1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilina AT, Hall WJ, Douglas RG, Jr, Utell MJ. Airway reactivity in subjects with viral upper respiratory tract infections: the effects of exercise and cold air. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:3–10. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala LE, Ahmed T. Is there loss of protective muscarinic receptor mechanism in asthma? Chest. 1989;96:1285–1291. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.6.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DG, Don HF, Brown JK. Direct measurement of acetylcholine release in guinea pig trachea. Am J Physiol. 1992;263(1 Pt 1):L142–L147. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.263.1.L142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bany U, Gajewski M, Ksiezopolska-Pietrzak K, Jozwicka M, Klimczak E, Ryzewski J, et al. Expression of mRNA encoding muscarinic receptor subtypes in neutrophils of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;876:301–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Muscarinic receptor subtypes in airways. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:328–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Tiotropium bromide. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:733–740. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ, Belvisi MG, Mak JC, Haddad EB, O'Connor B. Tiotropium bromide (Ba 679 BR), a novel long-acting muscarinic antagonist for the treatment of obstructive airways disease. Life Sci. 1995;56:853–859. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber LC, Fryer AD, Maclagan J. Neuronal muscarinic receptors attenuate vagally-induced contraction of feline bronchial smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1985;86:723–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb08951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson DB, Chin RA, Davis B, Nadel JA. Adrenergic and cholinergic nerves mediate fluid secretion from tracheal glands of ferrets. J Appl Physiol. 1980;49:1027–1031. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.6.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos IS, Gosens R, Zuidhof AB, Schaafsma D, Halayko AJ, Meurs H, et al. Inhibition of allergen-induced airway remodelling by tiotropium and budesonide: a comparison. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:653–661. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00004907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusasco V, Hodder R, Miravitlles M, Korducki L, Towse L, Kesten S. Health outcomes following treatment for six months with once daily tiotropium compared with twice daily salmeterol in patients with COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:399–404. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buels KS, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Selectively blocking M3 muscarinc receptors at the time of antigen challenge prevents airway hyperreactivity 24 h later in guinea pigs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:A3974. 1_MeetingAbstracts. [Google Scholar]

- Buhling F, Lieder N, Kuhlmann UC, Waldburg N, Welte T. Tiotropium suppresses acetylcholine-induced release of chemotactic mediators in vitro. Respir Med. 2007;101:2386–2394. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaburi R, Mahler DA, Jones PW, Wanner A, San PG, ZuWallack RL, et al. A long-term evaluation of once-daily inhaled tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:217–224. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00269802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casarosa P, Bouyssou T, Germeyer S, Schnapp A, Gantner F, Pieper M. Preclinical evaluation of long-acting muscarinic antagonists: comparison of tiotropium and investigational drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:660–668. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.152470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield MP, Birdsall NJ. International Union of Pharmacology. XVII. Classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:279–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh MJ, Cooper DM. Inhaled atropine sulfate: dose-response characteristics. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:517–524. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.114.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzola M, Matera MG. Novel long-acting bronchodilators for COPD and asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:291–299. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Brenner AM, Weiser PC, Chai H. Atropine and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Chest. 1981;79:651–656. doi: 10.1378/chest.79.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello RW, Evans CM, Yost BL, Belmonte KE, Gleich GJ, Jacoby DB, et al. Antigen-induced hyperreactivity to histamine: role of the vagus nerves and eosinophils. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5 Pt 1):L709–L714. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.5.L709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cugell DW. Clinical pharmacology and toxicology of ipratropium bromide. Am J Med. 1986;81:18–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cydulka RK, Emerman CL. Effects of combined treatment with glycopyrrolate and albuterol in acute exacerbation of asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:270–274. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cydulka RK, Emerman CL. Effects of combined treatment with glycopyrrolate and albuterol in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:470–473. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DS. Pharmacokinetics of inhaled substances. Postgrad Med J. 1975;51(7) Suppl:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disse B, Reichl R, Speck G, Traunecker W, Ludwig Rominger KL, Hammer R. Ba 679 BR, a novel long-acting anticholinergic bronchodilator. Life Sci. 1993;52:537–544. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90312-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disse B, Speck GA, Rominger KL, Witek TJ, Jr, Hammer R. Tiotropium (Spiriva): mechanistical considerations and clinical profile in obstructive lung disease. Life Sci. 1999;64:457–464. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue JF, Menjoge S, Kesten S. Tolerance to bronchodilating effects of salmeterol in COPD. Respir Med. 2003;97:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebell B. The Papyrus Ebers. Copenhagen: Levin Munksgaard; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Ellul-Micallef R. History of bronchial asthma. In: Barnes PJ, Grunstein MM, Leff AR, editors. Asthma. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Raven; 1997. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Empey DW, Laitinen LA, Jacobs L, Gold WM, Nadel JA. Mechanisms of bronchial hyperreactivity in normal subjects after upper respiratory tract infection. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;113:131–139. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.113.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensing K, de Zeeuw RA, Nossent GD, Koeter GH, Cornelissen PJ. Pharmacokinetics of ipratropium bromide after single dose inhalation and oral and intravenous administration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;36:189–194. doi: 10.1007/BF00609193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPR-3. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5) Suppl:S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CM, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB, Gleich GJ, Costello RW. Pretreatment with antibody to eosinophil major basic protein prevents hyperresponsiveness by protecting neuronal M2 muscarinic receptors in antigen-challenged guinea pigs. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2254–2262. doi: 10.1172/JCI119763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner D, Fryer AD, Maclagan J. Postganglionic muscarinic inhibitory receptors in pulmonary parasympathetic nerves in the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1986;88:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb09485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes LB, Fryer AD, Hirshman CA. M2 muscarinic receptors inhibit isoproterenol-induced relaxation of canine airway smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Parainfluenza virus infection damages inhibitory M2 muscarinic receptors on pulmonary parasympathetic nerves in the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer AD, Maclagan J. Muscarinic inhibitory receptors in pulmonary parasympathetic nerves in the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1984;83:973–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1984.tb16539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer AD, Maclagan J. Pancuronium and gallamine are antagonists for pre- and post-junctional muscarinic receptors in the guinea-pig lung. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1987;335:367–371. doi: 10.1007/BF00165549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer AD, Elbon CL, Kim AL, Xiao HQ, Levey AI, Jacoby DB. Cultures of airway parasympathetic nerves express functional M2 muscarinic receptors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:716–725. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.6.8969265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavalda A, Miralpeix M, Ramos I, Otal R, Carreno C, Vinals M, et al. Characterization of aclidinium bromide, a novel inhaled muscarinic antagonist, with long duration of action and a favorable pharmacological profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:740–751. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.151639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E. Historical Contributions to the Human Toxicology of Atropine : Behavioral Effects of High Doses of Atropine and Military Uses of Atropine to Produce Intoxication. 1st edn. Wentzville, MO: Eximdyne; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LS, Gilman A, Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL. Goodman & Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gross NJ. Ipratropium bromide. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:486–494. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808253190806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross NJ, Petty TL, Friedman M, Skorodin MS, Silvers GW, Donohue JF. Dose-response to ipratropium as a nebulized solution in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A three-center study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:1188–1191. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.5.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther W, Kamburoff PL. The bronchodilator effect of a new anticholinergic drug, Sch 1000. Curr Med Res Opin. 1974;2:281–287. doi: 10.1185/03007997409115235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad EB, Mak JC, Barnes PJ. Characterization of [3H]Ba 679 BR, a slowly dissociating muscarinic antagonist, in human lung: radioligand binding and autoradiographic mapping. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad EB, Patel H, Keeling JE, Yacoub MH, Barnes PJ, Belvisi MG. Pharmacological characterization of the muscarinic receptor antagonist, glycopyrrolate, in human and guinea-pig airways. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:413–420. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel TT, Neighbour H, Erin EM, Tan AJ, Tennant RC, Maus JG, et al. Glycopyrrolate causes prolonged bronchoprotection and bronchodilatation in patients with asthma. Chest. 2005;128:1974–1979. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinderling PH, Gundert-Remy U, Schmidlin O. Integrated pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of atropine in healthy humans. I: pharmacokinetics. J Pharm Sci. 1985a;74:703–710. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600740702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinderling PH, Gundert-Remy U, Schmidlin O, Heinzel G. Integrated pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of atropine in healthy humans. II: pharmacodynamics. J Pharm Sci. 1985b;74:711–717. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600740703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman MJ, Sheller JR, Dimeo M, Nadel JA, Boushey HA. Effect of ganglionic blockade on bronchial reactivity in atopic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:17–25. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman MJ, McNamara MP, Sheppard D, Fabbri LM, Hahn HL, Graf PD, et al. Intravenous versus inhaled atropine for inhibiting bronchoconstrictor responses in dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1983;54:134–139. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose M, Fujimoto T, Fukuchi Y. Tiotropium 5microg via Respimat and 18microg via HandiHaler; efficacy and safety in Japanese COPD patients. Respir Med. 2010;104:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos GF, Schelfhout VJ, Pauwels RA, Kanniess F, Magnussen H, Lamarca R, et al. Bronchodilatory effects of aclidinium bromide, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist, in COPD patients. Respir Med. 2010;104:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalser SC. The fate of atropine in man. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1971;179:667–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1971.tb46943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MK, Haberberger RV, Hartmann P, Faulhammer P, Lips KS, Krain B, et al. Muscarinic receptor subtypes in cilia-driven transport and airway epithelial development. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1113–1121. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00015108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littner MR, Ilowite JS, Tashkin DP, Friedman M, Serby CW, Menjoge SS, et al. Long-acting bronchodilation with once-daily dosing of tiotropium (Spiriva) in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(4 Pt 1):1136–1142. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9903044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Parekh DD, Kuznetsova O, Green SA, Tozzi CA, Reiss TF. An oral selective M3 cholinergic receptor antagonist in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:772–780. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00126005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maesen FP, Smeets JJ, Sledsens TJ, Wald FD, Cornelissen PJ. Tiotropium bromide, a new long-acting antimuscarinic bronchodilator: a pharmacodynamic study in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Dutch Study Group. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1506–1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak JC, Barnes PJ. Muscarinic receptor subtypes in human and guinea pig lung. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;164:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin MG, Davis B, Nadel JA. Effect of acetylcholine on Cl- and Na+ fluxes across dog tracheal epithelium in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1976;231(5 Pt. 1):1546–1549. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.5.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minette PA, Barnes PJ. Prejunctional inhibitory muscarinic receptors on cholinergic nerves in human and guinea pig airways. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:2532–2537. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minette PA, Lammers JW, Dixon CM, McCusker MT, Barnes PJ. A muscarinic agonist inhibits reflex bronchoconstriction in normal but not in asthmatic subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:2461–2465. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.6.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirakhur RK. Comparative study of the effects of oral and i.m. atropine and hyoscine in volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 1978;50:591–598. doi: 10.1093/bja/50.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel JA, Barnes PJ. Autonomic regulation of the airways. Annu Rev Med. 1984;35:451–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.35.020184.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Noord JA, Cornelissen PJ, Aumann JL, Platz J, Mueller A, Fogarty C. The efficacy of tiotropium administered via Respimat Soft Mist Inhaler or HandiHaler in COPD patients. Respir Med. 2009;103:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P. Long-acting muscarinic M3 receptor antagonists. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2006;16:1315–1320. doi: 10.1517/13543776.16.9.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor BJ, Towse LJ, Barnes PJ. Prolonged effect of tiotropium bromide on methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(4 Pt 1):876–880. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakes GE, Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Ipratropium bromide: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in asthma and chronic bronchitis. Drugs. 1980;20:237–266. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198020040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patacchini R, Bergamaschi M, Harrison S, Petrillo P, Gigli PM, Janni A, et al. In vitro pharmacological profile of CHF 5407, a potent, long-acting and selective muscarinic M3 receptor antagonist. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:25s–26s. [Google Scholar]

- Peretto I, Forlani R, Fossati C, Giardina GA, Giardini A, Guala M, et al. Discovery of diaryl imidazolidin-2-one derivatives, a novel class of muscarinic M3 selective antagonists (Part 1) J Med Chem. 2007a;50:1571–1583. doi: 10.1021/jm061159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretto I, Fossati C, Giardina GA, Giardini A, Guala M, La Porta E, et al. Discovery of diaryl imidazolidin-2-one derivatives, a novel class of muscarinic M3 selective antagonists (Part 2) J Med Chem. 2007b;50:1693–1697. doi: 10.1021/jm061160+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SP, Kunselman SJ, Icitovic N, Moore WC, Pascual R, Ameredes BT, et al. Tiotropium Bromide Step-Up Therapy for Adults with Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1715–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JE, Hey JA, Corboz MR. Effects of ion transport inhibitors on MCh-mediated secretion from porcine airway submucosal glands. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:873–881. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00174.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prat M, Fernandez D, Buil MA, Crespo MI, Casals G, Ferrer M, et al. Discovery of novel quaternary ammonium derivatives of (3R)-quinuclidinol esters as potent and long-acting muscarinic antagonists with potential for minimal systemic exposure after inhaled administration: identification of (3R)-3-{[hydroxy(di-2-thienyl)acetyl]oxy}-1-(3-phenoxypropyl)-1-azoniabicy clo[2.2.2]octane bromide (aclidinium bromide) J Med Chem. 2009;52:5076–5092. doi: 10.1021/jm900132z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D, Sharma A, Cerasoli F. Biochemical properties, pharmacokinetics and pharmacological response of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:417–424. doi: 10.1517/17425250902828337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proakis AG, Harris GB. Comparative penetration of glycopyrrolate and atropine across the blood – brain and placental barriers in anesthetized dogs. Anesthesiology. 1978;48:339–344. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebuck AS, Chapman KR, Abboud R, Pare PD, Kreisman H, Wolkove N, et al. Nebulized anticholinergic and sympathomimetic treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive airways disease in the emergency room. Am J Med. 1987;82:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90378-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinheimer T, Baumgartner D, Hohle KD, Racke K, Wessler I. Acetylcholine via muscarinic receptors inhibits histamine release from human isolated bronchi. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(2 Pt 1):389–395. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.96-12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo RD. Use of inhaled anticholinergic agents in obstructive airway disease. Respir Care. 2007;52:833–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo GJ, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Anticholinergics in the treatment of children and adults with acute asthma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Thorax. 2005;60:740–746. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.040444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo GJ, Rodrigo C. First-line therapy for adult patients with acute asthma receiving a multiple-dose protocol of ipratropium bromide plus albuterol in the emergency department. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1862–1868. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9908115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffel AF, Elzinga CR, Zaagsma J. Muscarinic M3 receptors mediate contraction of human central and peripheral airway smooth muscle. Pulm Pharmacol. 1990;3:47–51. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(90)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffin RE, Fitzgerald JD, Rebuck AS. A comparison of the bronchodilator activity of Sch 1000 and salbutamol. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1977;59:136–141. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(77)90215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelfhout VJ, Ferrer P, Jansat JM, Peris F, Gil EG, Pauwels RA, et al. Activity of aclidinium bromide, a new long-acting muscarinic antagonist: a phase I study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010a;69:458–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelfhout VJ, Ferrer P, Jansat JM, Peris F, Gil EG, Pauwels RA, et al. Activity of aclidinium bromide, a new long-acting muscarinic antagonist: a phase I study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010b;69:458–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheis AJH. The effect of ozone on inflammatory cell infiltration and airway hyperresponsiveness in the guinea pig lungThesis (Ph D) 1992. Johns Hopkins University, 1993.

- Schultheis AH, Bassett DJ, Fryer AD. Ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and loss of neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor function. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1088–1097. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard D, Epstein J, Holtzman MJ, Nadel JA, Boushey HA. Dose-dependent inhibition of cold air-induced bronchoconstriction by atropine. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53:169–174. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard D, Epstein J, Holtzman MJ, Nadel JA, Boushey HA. Effect of route of atropine delivery on bronchospasm from cold air and methacholine. J Appl Physiol. 1983;54:130–133. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkness R, Clough JJ, Castleman WL, Lemanske RF., Jr Virus-induced airway obstruction and parasympathetic hyperresponsiveness in adult rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:28–34. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley RG, Aaron SD, Dales RE. The role of ipratropium bromide in the emergency management of acute asthma exacerbation: a metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:8–18. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinney DC. Biochemical mechanisms of drug action: what does it take for success? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:801–808. doi: 10.1038/nrd1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Belvisi MG, Patel H, Ward JK, Tadjkarimi S, Yacoub MH, et al. Effect of Ba 679 BR, a novel long-acting anticholinergic agent, on cholinergic neurotransmission in guinea pig and human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(6 Pt 1):1640–1645. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.6.7952627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP, Ashutosh K, Bleecker ER, Britt EJ, Cugell DW, Cummiskey JM, et al. Comparison of the anticholinergic bronchodilator ipratropium bromide with metaproterenol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 90-day multi-center study. Am J Med. 1986;81(5) Suppl 1:81–90. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbout NG, Lorton JK, Jacoby DB, Fryer A. A functional role for muscarinic receptors on eosinophils in the airways. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:A587. [Google Scholar]

- Vincken W, van Noord JA, Greefhorst AP, Bantje TA, Kesten S, Korducki L, et al. Improved health outcomes in patients with COPD during 1 yr's treatment with tiotropium. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:209–216. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00238702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincken W, Bantje T, Middle MV, Gerken F, Moonen D. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Ipratropium Bromide plus Fenoterol via Respimat((R)) Soft Misttrade mark Inhaler (SMI) versus a Pressurised Metered-Dose Inhaler in Asthma. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:17–28. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward MJ, Fentem PH, Smith WH, Davies D. Ipratropium bromide in acute asthma. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282:598–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6264.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellstein A, Pitschner HF. Complex dose-response curves of atropine in man explained by different functions of M1- and M2-cholinoceptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1988;338:19–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00168807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessler IK, Kirkpatrick CJ. The Non-neuronal cholinergic system: an emerging drug target in the airways. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2001;14:423–434. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines Vol. 2010. 2010.

- Yost BL, Gleich GJ, Fryer AD. Ozone-induced hyperresponsiveness and blockade of M2 muscarinic receptors by eosinophil major basic protein. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1272–1278. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.4.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.