Abstract

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide, is responsible for 35 percent of maternal deaths. Proximately, PPH results from the failure of the placenta to separate from the uterine wall properly, most often because of impairment of uterine muscle contraction. Despite its prevalence and its well-described clinical manifestations, the ultimate causes of PPH are not known and have not been investigated through an evolutionary lens. We argue that vulnerability to PPH stems from the intensely invasive nature of human placentation. The human placenta causes uterine vessels to undergo transformation to provide the developing fetus with a high plane of maternal resources; the degree of this transformation in humans is extensive. We argue that the particularly invasive nature of the human placenta increases the possibility of increased blood loss at parturition. We review evidence suggesting PPH and other placental disorders represent an evolutionarily novel condition in hominins.

Keywords: postpartum hemorrhage, evolutionary medicine, comparative placentation, implantation, trophoblast

THE THREAT OF POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE

Human childbirth is treacherous. In 2008, there were 358,000 maternal deaths, largely in developing countries (United Nations 2010a).1 On a global level, one woman in 74 will die of maternal causes—and in sub-Saharan Africa, this risk can be as high as one in six (Ronsmans and Graham 2006). Maternal mortality rates (MMRs) have very likely been as high or higher for much of human history. Estimates from historical data and religious groups that decline medical treatment suggest that, without any intervention, maternal mortality would be very high, perhaps 1,000–1,500 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (1–1.5 percent; see Van Lerberghe and De Brouwere 2001). Kim Hill and colleagues (2007) estimated approximately one in 55–75 (1.3–1.8 percent) Hiwi women of Venezuela die in childbirth. These rates approximate the current MMR in the sub-Saharan countries with the highest rates of maternal mortality, like Afghanistan, Chad, and Somalia (respectively, 1,400, 1,200, and 1,200 per 100,000 live births; United Nations 2010a).

Reducing the incidence of maternal mortality is a global imperative. For example, President Obama has designated maternal health as one of the funding priorities for US global health aid during his administration (Obama 2009). Obama’s stance on maternal health reinforces the aim of the United Nations Millennium Development Goal #5: to reduce the MMR by 75 percent by 2015, in part by encouraging women to deliver in the presence of skilled attendants (United Nations 2010b). Although the improvement in the global MMR was slow initially—dropping minimally between 1990 and 2005, from 430 to 400 (United Nations 2010b)—the pace of improvement has since accelerated, such that the MMR was only 260 in 2008 (United Nations 2010a). Unfortunately, even at the current pace, the goal of a 75 percent MMR reduction is unlikely to be met by 2015.

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), a catastrophic loss of maternal blood associated with impaired placental separation from the uterine wall, is the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide, accounting for up to 35 percent of maternal deaths, or 125,000 women annually (Khan and El-Refaey 2006). PPH is estimated to affect 10.5 percent of human births worldwide (WHO 2005). As Andre Lalonde and colleagues state, PPH is an “equal-opportunity occurrence” but “not an equal-opportunity killer” (Lalonde et al. 2006:245). Globally, there are huge disparities in PPH-related mortality: PPH accounts for 34 percent of maternal deaths in sub-Saharan Africa and 31 percent in Asia, but only 13 percent of maternal deaths in resource-rich areas (Khan et al. 2006). As PPH “can kill even a healthy woman within two hours, if unattended” (WHO 2005:62), then “it is the poor, malnourished, unhealthy woman delivered away from medical care who will die from it” (Lalonde et al. 2006:245). Because distance to a health center and availability of transport are key determinants of where women deliver (Kruk et al. 2009), women who hemorrhage after a home delivery may be the least able to travel to a health center after birth and thus the most likely to die. Encouragingly, the proportion of women in developing countries who received skilled assistance during delivery rose ten percent between 1990 and 2008, from 53 percent to 63 percent (United Nations 2010b).

Despite its ubiquity, the root causes of PPH remain obscure. In a typical delivery, the placenta begins to separate from the uterine wall even before the delivery of the baby (Khan and El-Refaey 2006). Uterine bleeding at the site of placental separation is normally stopped by “the mechanical constriction of the blood vessels due to the uterine muscle contraction and retraction and by clots sealing off the raw surface in the placental bed” (Choo et al. 1998:179–180). Uterine contractions are promoted by the pituitary hormone oxytocin, the release of which is stimulated during birth by the stretching of the cervix and vaginal canal and during lactation by nipple stimulation (Christensson et al. 1989). Indeed, conservative management of hemorrhage includes encouraging nipple stimulation to trigger uterine contractions and unassisted placental delivery (Mathai et al. 2007; McDonald 2007). Coagulation factors in maternal blood contribute to the formation of clots that also stem the blood flow (Martinelli et al. 2010). When uterine bleeding is not stopped by these mechanisms, the threat of maternal death from catastrophic hemorrhage is very real. Clinically, PPH is usually defined as a loss of approximately 500 cubic centimeters of blood at or around delivery (for vaginal births), but it can also be defined as a life-threatening change in blood pressure or a need for a blood transfusion (Coker and Oliver 2006). Although PPH can occur in the weeks following birth, most PPH—as well as most of the deaths associated with it—occur in the first four hours after delivery.

The two major risk factors for PPH, uterine atony and a prolonged third phase of labor (delivery of the placenta delayed more than 30 minutes after delivery of the neonate), together account for 93 percent of PPH-related deaths (Carroli et al. 2008). Uterine atony, the absence of adequate uterine contractions to sufficiently clamp the uterine vessels and stop bleeding, is the leading risk factor for PPH, accounting for 70 percent of the cases (Khan and El-Refaey 2006). The underlying causes of uterine atony, however, are unclear. Uterine atony is often associated with retained or incomplete placenta delivery, but the directionality of this link is not clear. It is possible that a retained placenta and its vessels may present a physical barrier to uterine muscle contraction. Conversely, uterine atony could hinder placental separation and expulsion. Besides physical and physiological factors that may block the ability of the uterus to contract, risk factors that overstretch the uterus are also associated with atony, including multiple pregnancy, macrosomia (birth weight greater than 4,000 grams, or 8.82 pounds), and polyhydramnios (too much amniotic fluid; Khan and El-Refaey 2006). The ultimate causes of PPH are as yet unknown, but considering the evolutionary primacy of reproduction and pregnancy, the integration of clinical medicine and evolutionary biology is a logical avenue to pursue.

In this article, we explore a novel, evolutionarily driven hypothesis regarding human vulnerability to PPH. We argue that this susceptibility has deep roots in the human pattern of highly invasive placentation. To support this argument, we review some of the key features of invasive human placentation, consider the comparative evidence for placental disorders related to trophoblast invasion, propose that overly aggressive placental invasion may be critical to the etiology of PPH, and evaluate the evidence for a deep human history of PPH.

THE IMPORTANCE OF PLACENTAL DEVELOPMENT IN HUMAN VULNERABILITY TO PPH

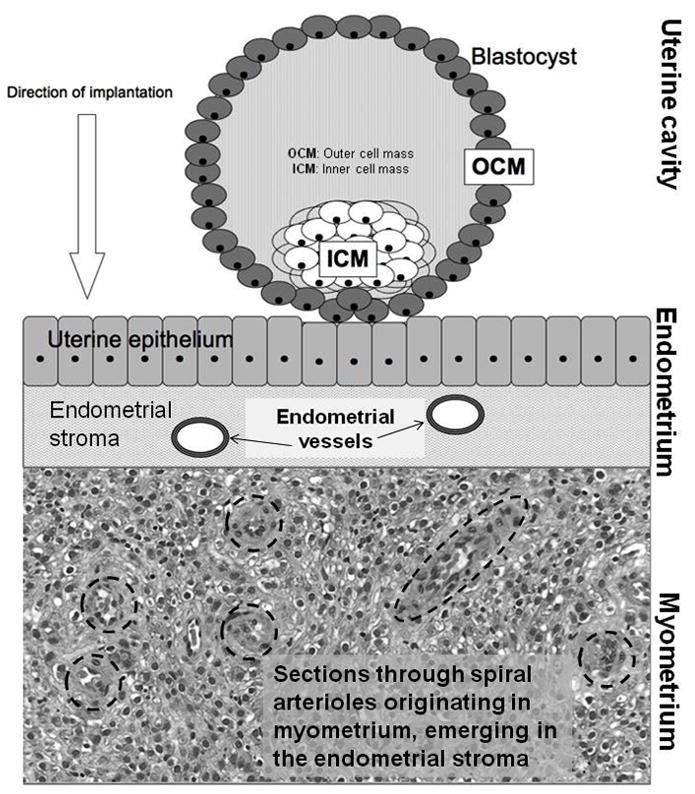

We propose that there may be a critical link between the human pattern of placentation and the high risk of extensive blood loss at delivery. Specifically, we suggest that the intensity and extent of placental invasion into the uterine wall and subsequent transformation of the maternal vasculature, which are adaptations to maximize resource transfer to the developing fetus, play key roles in the etiology of PPH. A brief description of the development of the placenta is thus critical to building this argument (for greater detail, see Benirshcke and Kaufmann 1982; Luckett 1974, 1976; Mossman 1937, 1987; Wislocki 1929). The primate placenta forms within a few days of fertilization from cells of fetal origin, the trophoblasts. The trophoblasts comprise the outer cell mass (OCM) of the early blastocyst, a hollow ball of cells derived from the fertilized egg (Mossman 1937, 1987; see Figure 1), while the inner cell mass of the blastocyst gives rise to the fetus. Because of its shared origin with the fetus, the placenta can be viewed as an extrasomatic fetal organ, which acts as a sensor of nutrient availability in maternal circulation and thus a calibrator of fetal growth (Jansson and Powell 2006).

Figure 1.

The pre–implantation stage of the human embryo. The implanting blastocyst is a hollow ball of cells that contains an internal mass of cells that will give rise to the embryo proper surrounded by an outer shell of cells called trophoblasts. These cells will form part of the placenta. Later migrations of extraembryonic mesoderm from the developing embryo will complete the placental structures. Together, the trophoblast and embryonic mesoderm form the placental villi. (Modified from Rutherford 2009)

Placentas are the most morphologically variable organ among the mammalian taxa (Kaufmann 1983; Mossman 1937). The placenta may manifest as one or two round discs, as in primates and rodents; as a simple band or loop of tissue, as in carnivores; as a network of small discrete round patches scattered throughout the uterus, as in sheep; or it may diffusely cover the entire uterine wall, as in horses, pigs, and cetaceans (Mossman 1937, 1987). Whereas all placentas act as the intrauterine interface between mother and fetus, the degree to which the placenta advances into the uterus and thus the maternal circulation varies markedly. Placentas show striking variation in invasiveness, exhibiting three main phenotypes (as originally described by Grosser 1909). The epitheliochorial placenta is the least invasive form; it adheres to the epithelial lining of the uterine wall without penetrating it, and thus there is no contact with underlying maternal vasculature. Nutrient transport into the fetal circulation is conducted via diffusion through several layers of tissue: the walls of the maternal vessels, the surrounding endometrial stroma, the uterine epithelium, and finally the chorion, which is comprised of trophoblasts from the OCM and fetal mesoderm, a tissue deriving from one of the main three cell layers of the early embryo. In order of invasiveness, the next mode is endotheliochorial, whereby the chorion penetrates the endometrial surface and is in contact with the endothelium of maternal vessels but is not immediately adjacent to maternal blood. The most invasive form is the hemochorial placenta (as seen in rodents and primates), in which the chorion penetrates the endometrial epithelium and the deeper endometrial stroma to arrive in contact with maternal vessels and subsequently even penetrates the vessel walls, so that placental tissue is in direct contact with maternal blood.

There is even further differentiation within hemochorial placentation in terms of depth of implantation. In placentation in the monkeys, there is moderate penetration of the uterine lining by the chorion (Luckett 1976). Trophoblast cells surround maternal vessels within the endometrium and cause them to lose some of their muscularity, which in turns lowers vascular resistance and increases blood flow to the developing embryo (Kaufmann et al. 2003). The monkey placenta forms a trophoblast shell, which is a mostly continuous layer of trophoblast cells within the endometrium that largely limits trophoblast invasion into the myometrium (Blankenship and Enders 2003; Ramsey et al. 1976). In contrast to placentation in monkeys, the hominoid (ape and human, and presumably early hominin) placenta is much more invasive, deeply penetrating the uterine epithelium and migrating through the endometrial stroma beneath into the upper third of the myometrium, the thick muscular wall of the uterus (Enders et al. 1996; Mossman 1987; Pijnenborg et al. 1996). The human trophoblasts extensively invade and remodel the maternal spiral arterioles, the small coiled vessels that originate in the myometrium to populate and nourish the rich endometrium (Robillard 2002; Figures 1 and 2). Less is known about placentation in the other hominoids than in modern humans, but very recent reports suggest that this invasive placentation occurs in the African great apes as well, although the currently available data are drawn from two chimpanzee placentas (Carter and Pijnenborg 2010). There is no data regarding the extent of invasiveness yet available from the orangutan, but deeply invasive placentation (i.e. extensive arteriole remodeling extending into the myometrium) does not appear to occur in the smaller Asian apes (Anthony Carter, conversation with Rutherford, October 20, 2010). It is important to note here that the degree of placental invasiveness—epitheliochorial, endotheliochorial, or hemochorial—should not be viewed as representative of qualitative shifts in placental efficiency in regard to supporting fetal growth. Indeed, the orders producing the largest fetuses relative to adult weight are cetaceans (whales and dolphins), artiodactyls (e.g., hippopotamuses, giraffes), and perissodactyls (e.g., horses, rhinoceroses), which all have the least invasive placentas (Martin 2007), suggesting that physiological and metabolic features of the placenta—such as membrane thickness, nutrient consumption rates, or transporter density per unit area—refine the role of gross morphological traits of the placenta in supporting fetal growth.

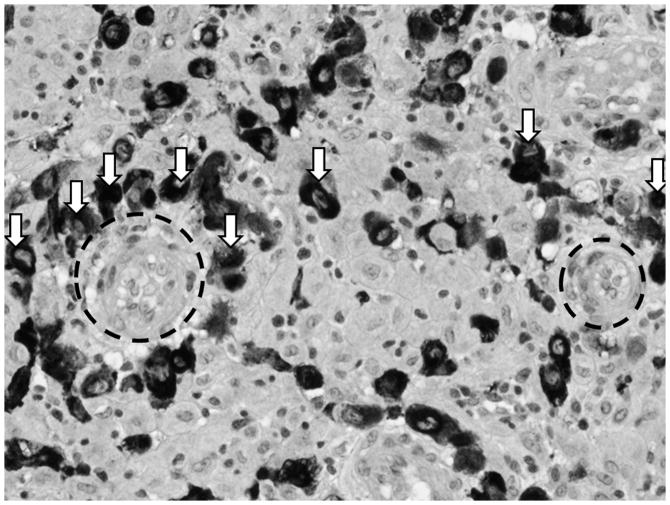

Figure 2.

Darkly staining invasive extravillous cytotrophoblasts (ECT, some indicated by white arrows) surrounding maternal arterioles (outlined in black hashed circles). Arteriole on left is completely surrounded by ECT and further along the conversion process than the arteriole on the right. (Micrograph used with permission from Harvey Kliman, MD, PhD, Yale University)

To accomplish the extraordinary feat of deeply invading the uterus and remodeling its vessels, the trophoblast cells develop an invasive phenotype (Kliman 2000; Figure 3). Some trophoblast cells become the villous cytotrophoblasts that cover mesoderm cores to become the chorionic villi (Figure 3, “VCT”). These villi are in direct contact with maternal blood pulsating throughout the placenta. As gestation progresses, most of the cytotrophoblasts fuse to form a continuous multinucleated layer called the syncytiotrophoblast (Figure 3, “SCT”), across which nutrient, gas, and waste transport takes place. A second type of trophoblast cells mediates the placental adherence to the uterine wall as anchoring columns (Figure 3, “ACT”). The last group of cytotrophoblast cells develops a highly invasive phenotype. These extravillous invasive cytotrophoblasts break free from the other trophoblast cells and migrate deeper into the uterus. They surround the maternal spiral arterioles and initiate a breakdown of their internal muscular layer (the tunica media; see Figure 2). This replaces the muscular and elastic tissue of the arteriole wall with a thick layer of noncontractile fibrinoid material, which in turn reduces vascular resistance. The shape of the vessel is also converted in such a way that the diameter of the vessel increases and the distal portion opens into a funnel-like outlet into the growing placenta (Espinoza et al. 2006; Rockwell et al. 2003). These changes combine to maximize the blood flow to the placenta, increase the hemodynamic efficiency of the organ, and reduce the potential impact of vasoconstrictors (Espinoza et al. 2006). The invasion and subsequent conversion of the deeper vessels of the human uterus takes place early in the second trimester, around 15 weeks (Robillard et al. 2002). In sum, this transformation impairs the ability of maternal vasculature to physically limit blood flow to the placenta, a strategy that channels large quantities of nutrients and oxygen to the large-for-maternal-body-size newborns of hominoids, including humans (Chaline 2003; Dufour and Sauther 2002; Martin 1983, 2003). As we argue in the following sections, this process (and specifically its dysregulation) may play an important and as yet unexamined role in the etiology of PPH in humans.

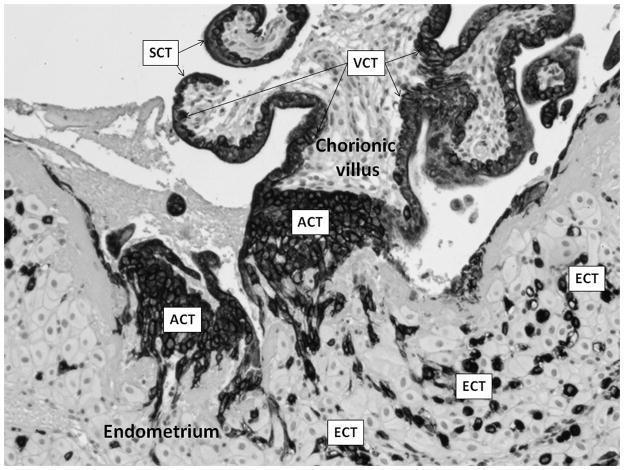

Figure 3.

Localization of differentiated human trophoblast cells. Human placenta, section through chorionic villus (embryonic mesoderm core covered in trophoblast) and underlying endometrium. Dark-staining cells are various trophoblast phenotypes: SCT = syncytiotrophoblast; VCT = villous cytotrophoblast; ACT = anchoring cytotrophoblast; ECT = extravillous invasive cytotrophoblast. (Micrograph used with permission from Harvey Kliman, MD, PhD, Yale University)

HUMAN VULNERABILITY TO POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE IN COMPARATIVE CONTEXT

PPH is rare in domestic animals for which substantial data are available (Noakes et al. 2001). David Noakes and colleagues (2001:319) report that, because many domesticated animals (e.g., swine, horses, cattle) have noninvasive epitheliochorial placentas, bleeding at or around the time of delivery is only likely if excessive force is used to deliver the placenta; in fact, in these animals, “the usual cause of serious hemorrhage is laceration of a uterine blood vessel by a fetal appendage, obstetric instrument, or hand of the obstetrician”—in other words, trauma followed by hemorrhage. For example, James Rooney (1964) reported ten fatal cases of PPH in aging mares, all related to lacerations of arteries. In carnivores like the house cat, moderately invasive endotheliochorial placentas allow for an increased risk of blood loss at delivery, particularly when the placenta is precipitously removed during elective cesarean sections (Noakes et al. 2001). These data, albeit minimal, suggest that blood loss at delivery has a direct connection to the degree of placental invasiveness, such that animals with minimally invasive epitheliochorial placentas are unlikely to bleed at delivery except in the case of induced vascular trauma, while those with moderately invasive endotheliochorial placentas may bleed if the placenta is prematurely separated from the uterine wall.

If the invasiveness of the placental type predicts the probability of blood loss at delivery, then orders with hemochorial placentation, the rodents and the primates, should be expected to lose at least some blood postpartum. Unfortunately, there are very few data available on postpartum bleeding or its risk factors in either rodents or nonhuman primates. We could find no data regarding postpartum hemorrhage in rodents. Anecdotally, some nonhuman primate observers report that a small degree of blood loss is common at delivery (captive chimpanzees: Steven Ross, e-mail with Abrams, August 2, 2010; wild mantled howler monkeys: Paul Garber, conference presentation, October 2009; captive common marmoset monkeys: Rutherford, personal observation, August 2004–July 2006), but we were unable able to find any accounts of excessive blood loss at delivery or maternal mortality linked to PPH in the nonhuman primate literature. In addition, we found only two published reports of retained placenta, a key risk factor for PPH, in nonhuman primates (Bronson et al. 2005; Halbwax et al. 2009). Considering the importance of pregnancy and labor in zoos and captive research and breeding facilities, the lack of an anecdotal literature on PPH in nonhuman primates can be viewed as tentative support for the hypothesis that the elevated incidence of PPH is unique to humans, although more systematic study is clearly required, particularly among the great apes.

RISKY BUSINESS: PLACENTAL INVASION AND VASCULAR REMODELING

The differentiation and subsequent invasion described above are normal components of human pregnancy. However, the process of trophoblast invasion must be finely tuned. As Harvey Kliman observes,

Enacting this scenario takes a very delicate balancing of conflicting biological needs between the mother and fetus. The fetus, on the one hand, requires its invasive trophoblasts to penetrate the mother’s uterus aggressively in search of vessels to modify. The mother, on the other hand, must protect herself from the invasive trophoblasts, lest they completely penetrate her uterus, causing her to hemorrhage and bleed to death. [Kliman 2000:1760]

One manifestation of the disruption of this delicate balance in utero may be preeclampsia (PE). PE is characterized by shallow trophoblast invasion and insufficient remodeling of maternal vessels. Rather than being transformed into the wide, straight funnels that easily conduct maternal blood to the placenta and in turn the fetus, the maternal spiral arterioles remain coiled, their muscular walls intact and operable, thus restricting blood flow to the placenta (Fisher 2004). This starkly limits fetal access to maternal tissues (Chaline 2003; Robillard et al. 2002), suggesting that PE represents a case in which maternal agendas successfully limit investment (Haig 1993).

From a proximate perspective, Kliman and colleagues have recently suggested that placental protein 13 (PP13), a protein that triggers an immune response by maternal tissues, may be employed by the fetal side of the placenta as a decoy to divert the attention of the maternal immune system away from the true front lines of trophoblast invasion, as PP13 is produced not by the invasive extravillous trophoblasts surrounding the maternal arterioles but, rather, by villous syncytiotrophoblast (Kliman et al. n.d.). Supporting this diversion hypothesis, several researchers have shown that low PP13 levels during the first trimester are associated with an increased risk of developing PE (Chafetz et al. 2007; Cowans et al. 2008; Than et al. 2004). In other words, the low levels of PP13 characteristic of PE do not fully misdirect the maternal immune response away from the invasive trophoblasts, allowing an increased level of maternal protection against aggressive vascular remodeling and thus leaving vessels underremodeled. Conversely, if levels of PP13 are excessive, the maternal immune response may be diverted to such an extent that vessels are exceptionally vulnerable to invasion and remodeling, leading to an overperfusion of the placenta and potentially to uncontrolled blood loss during placental separation (i.e., PPH).

PE is the primary cause of maternal mortality in resource-rich countries (Fisher 2004) and the second leading cause (after PPH) of maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide (Hawfield and Freedman 2009). The incidence of PE and eclampsia—the latter of which is a very severe development of the former that can lead to maternal convulsions, coma, and death—may be as high as 18 percent in some African nations (Maharaj and Moodley 1994). PE is also associated with high fetal and neonatal mortality, even in technologically advanced medical contexts (Lydakis et al. 2001). Even when PE does not directly lead to fetal death, it is frequently associated with a number of poor outcomes, including relative placental overgrowth, reductions in blood flow through the placenta, and intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), a condition marked by small-for-gestational-age neonates. IUGR is a major risk factor for fetal and neonatal mortality (Fang 2005; Garite et al. 2004; Tan and Yeo 2005) and may program the fetus for increased adult susceptibility to diabetes, obesity, and poor cardiovascular health (Barker 1995, 1998; Eriksson et al. 2010; Godfrey and Barker 2001; Kuzawa and Adair 2004).

Besides preeclampsia, there are a number of disorders representing a range of placental invasiveness. On one end of the spectrum is placental abruption, in which the placenta prematurely separates from the uterine wall, suggestive of shallow implantation (Tikkanen 2010). On the other end of the range is the cluster of highly invasive disorders comprising placental accreta, whereby trophoblast invasion is severely dysregulated and the placenta implants far beyond its normal limits (Angstmann et al. 2009). The most invasive of these is placenta percreta, in which the placenta completely penetrates the myometrium, in some cases migrating out onto organs outside the reproductive tract, such as the rectum or kidneys (Moore and Gonzalez 2008). Placenta percreta, which can lead to spontaneous uterine rupture (Esmans et al. 2004), is often localized to areas of uterine scarring, as the nonvascular fibrous scar tissue that replaces the muscle may allow overimplantation (Khan and El-Refaey 2006). The highly invasive nature of human trophoblasts can also give rise to gestational trophoblastic diseases such as choriocarcinoma, a neoplasm that can metastasize to the lungs and cause death years after pregnancy (Shintaku et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2005).

THE LINK BETWEEN PLACENTATION AND POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE

Just as PE is a gestational disorder arising from impaired placentation and resultant underremodeling of the uterine vasculature, we suggest that PPH has its roots in overly aggressive placental invasion and vascular remodeling. Severe blood loss at delivery may be an unfortunate by-product of selection to maximize the transport of maternal resources to the fetus, occurring when trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling are extreme and leading to overremodeled vessels that are too wide, too open, too conductive of maternal blood to the placenta. In support of this hypothesis (and in direct contrast to PE), one of the clinical risk factors for PPH is macrosomia, which is defined as fetal weight over 4,000–4,500 grams (8.82–9.92 pounds) or weight over the 90th percentile for gestational age (Sacks and Chen 2000). Fetal macrosomia is indicative of a high rate of nutrient delivery to the fetus, as would be expected if the vessels supplying the placenta were expanded in size, number, or power.

There are a number of factors that may contribute to this overremodeling. As mentioned above, the PP13 decoy mechanism that lures maternal immune response factors away from the invasive trophoblast cells surrounding the spiral arterioles (Kliman et al. n.d.) may be poorly regulated (e.g., released in an overly diffuse spatial pattern or produced in excessively large quantities). This could lead the maternal immune system to respond inadequately to the activity of invasive trophoblasts on the arterioles, leaving these vessels vulnerable to becoming excessively remodeled and overly conductive of maternal blood to the fetoplacental unit. Alternatively or concomitantly, more arterioles than usual may be remodeled or even recruited to form de novo by the invasive cells. Indeed, invasive trophoblast cells are capable of attracting and increasing neighboring maternal blood flow through the production of factors that promote vessel dilation and discourage clot formation (Athanassiades and Lala 1998; Cross et al. 2002; Hemberger et al. 2003). These invasive cells can also completely displace the maternal cells lining the remodeled vessels, essentially forming new blood vessels of placental origin within the uterus (Hemberger et al. 2003). In addition to the great advantage of directly soliciting and facilitating increased maternal blood flow to the placenta and fetus, these mechanisms, when unchecked, may also have the effect of replacing or handicapping uterine muscle cells, thus diminishing the effective ratio of contractile-to-noncontractile tissue in the myometrium and dampening the ability of the uterus to contract. A high rate of vascular turnover and inflammation could be accompanied by an accumulation of subclinical uterine trauma and scarring that could also hamper contractility, which is the most significant immediate risk factor for hemorrhage.

EVIDENCE FOR EVOLUTIONARY NOVELTY OF PLACENTAL DISORDERS IN HUMANS

We turn again to the preeclampsia literature to serve as a corollary for PPH. Tellingly, PE has frequently been described as a disorder unique to humans because of the role of trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling (Chez 1976; Jauniaux et al. 2006; Pijnenborg et al. 2006; Rosenberg and Trevathan 2007), although this is not universally supported. Anthony Carter and Robert Martin (in press) recently critiqued the conventional wisdom of PE as a uniquely human condition, suggesting that this assumption has not been exposed to extensive inquiry. They cite examples of physiological changes in pregnant primates that may indicate a deeper evolutionary timeline for PE. For example, in a study of five pregnant baboons who underwent uterine artery ligation (a treatment that effectively limits blood flow to the placenta and increases maternal blood pressure), symptoms consistent with PE were observed: namely, changes to the microscopic kidney morphology, proteinuria, and increased blood pressure (Makris et al. 2007). Annemarie Hennessy and colleagues (1997) described similar renal and hypertensive symptoms in a baboon pregnant with twins. Comparable changes to the kidney have been observed in a single chimpanzee (Stout and Lemmon 1969), and symptoms tentatively described as “eclamptic convulsions” have been observed in two matrilineally related gorillas (Thornton and Onwude 1992).

Although this small dataset (n = 9, across three genera) points to the possibility that the hypertensive symptoms of PE may not be limited to humans, none of these studies described any morphological features of the placenta corresponding to the well-described alteration of invasive events that characterizes PE in humans (Fisher 2004). What is consistent in these examples is the induction of a hypertensive environment, either through the mechanical restriction of blood flow to the uterus or through spontaneous multiple pregnancy. Further, as Carter and Martin (in press) also note, the invasive extravillous trophoblasts responsible for the extensive vascular remodeling of the human uterine vasculature appear to be absent in baboons and macaques, the monkey species in which placentation has been most studied. Taken together, the available observations suggest to us that although the hypertensive symptoms of PE may be inducible within the primate order, the underlying placental causation—blocking of the characteristically deep invasion and extensive vascular remodeling—either is unique to hominins or at least has not yet been definitively shown to be a component of the etiology of gestational hypertension in nonhuman primates, even in the two great ape species in which invasive remodeling has been demonstrated (Carter and Pijnenborg 2010; Pijnenborg et al. in press). Thus, we suggest by extension that, although catastrophic blood loss at delivery may occasionally occur in all placental mammals, it is the extreme trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling of the human placenta that underlies the uniquely high incidence and risk of PPH.

Genetic and ethnographic evidence offer more clues to a deep human history of PPH. Pelle Lindqvist and colleagues (Lindqvist and Dahlback 2008; Lindqvist et al. 1998) argue that polymorphisms that promote coagulation (i.e., thrombophilias, the propensity to form blood clots) have been selected to counterbalance the risk of PPH. Factor V Leiden (FVL), one of the best characterized procoagulatory mutations, causes a resistance to the anticoagulatory activity of Activated Protein C (APC; Spina et al. 2000); this allows individuals with the FVL mutation to clot faster. Approximately five percent of Europeans carry the FVL gene, and frequencies can reach as high as 10 to 15 percent in northern Europe, where the mutation likely arose (Spina et al. 2000) approximately 21,000 years ago (Zivelin et al. 2006). In a retrospective Swedish study, Lindqvist et al. (1998) found that women who were homozygous or heterozygous for the FVL mutation lost significantly less blood at delivery (an average of ~60 ml less blood lost; p = 0.001) and were significantly less likely to hemorrhage than individuals without the mutation (defined in this study as ≥ 600 ml blood loss; 2 percent of those with the mutation vs. 14 percent of those without it; p = 0.01). Even if thrombophilias offer protection against PPH, carriers may incur other potentially significant costs. The most significant of these costs is an increased risk of thromboembolism (a blood clot that breaks free from the vessel in which it forms, thus entering the circulation and blocking another vessel—e.g., in the brain or lung) in pregnancy, which accounts for approximately 15 percent of maternal deaths (Khan et al. 2006). A recent systematic literature review and metanalysis of the risk of thrombosis (a condition characterized by the formation of venous blood clots) in pregnancy for FVL carriers determined that homozygotes have a relative risk as high as 34.4 percent compared to the 8.3 percent risk of heterozygotes, although this does not translate to an exceptionally high absolute risk (3.4 percent in homozygotes and 0.8 percent in heterozygotes), given the rarity of thrombosis in the overall population (1:1000; Robertson et al. 2006). The costs of FVL, which accounts for over 40 percent of all thromboses, are also suggested by its virtual absence among natives of Africa and Asia (Spina et al. 2000), parts of the world where the mortality rate due to PPH is especially high. Lindqvist and colleagues (Lindqvist and Dahlback 2008; Lindqvist et al. 1998) argue that the maintenance of the FVL allele at such a high frequency despite its associated risks is indicative of strong balancing selection for protection against PPH.

Yvonne Lefèber and Henk Voorhoeve (1998) extensively reviewed childbirth customs and discussed a number of interventions by traditional birth attendants (TBAs) that appear to mimic the effects of WHO-recommended biomedical interventions in encouraging placental delivery. Termed active management of the third phase of labor, the WHO recommends facilitating the delivery of the placenta via controlled cord traction, in which an attendant gently but firmly grasps the umbilical cord to help guide the placenta out; uterine massage, which stimulates muscular contraction; and injections of drugs like Pitocin (i.e., synthetic oxytocin), which induce uterine contractions (WHO 2007). First, if the placenta is delayed, TBAs may administer substances or perform actions that will cause the delivering woman to sneeze, gag, or vomit, thus tensing the abdominal muscles and contracting the uterus. For example, TBAs may insert garlic or hair into the woman’s mouth or administer salted water to induce gagging or vomiting (Lefèber and Voorhoeve 1998). In Jamaica, the woman may be encouraged to inhale deeply then exhale forcefully into a bottle, which applies internal pressure to the uterus and can stimulate contractions (Kitzinger 1982). Second, abdominal pressure and uterine massage, pressing, and rubbing are widely reported (Lefèber and Voorhoeve 1998). In West Melanesia, a hot compress made of wood may be applied to the vulva and abdomen to stop the flow of blood (Lefèber and Voorhoeve 1998). And third, Lefèber and Voorhoeve (1998) present examples from India, Malaysia, Ghana, and Indonesia of TBAs pulling on the umbilical cord and manually removing the placenta, which harkens back to the WHO’s example of controlled cord traction. These examples demonstrate that TBAs attend to cues of possible PPH and are able to intervene in manners that replicate the effects of the WHO’s recommended actions. The crosscultural variations in these interventions suggest these traditions have deep roots, and the minimal materials required suggest that these sorts of interventions could have been performed by earlier hominins, who were already likely engaging in obligate midwifery because of the anatomical complications of delivering a large-headed neonate through a relatively restricted birth canal (Trevathan 1987).

If PPH is not a common feature of mammalian or even primate pregnancy, when did the vulnerability to PPH arise in human history? Christie Rockwell and colleagues (2003) suggest that the shift toward bipedal locomotion approximately seven million years ago and its attendant consequences for pelvic anatomy may have spurred changes in patterns of placental invasiveness and vascular remodeling to counteract gravitational effects. They argue that a shift to habitual bipedal posture and locomotion would have put the major abdominal vasculature (e.g., inferior vena cava, abdominal aorta) at risk of compression by the gravid uterus (Abitbol 1993). This in turn would have constrained blood flow and thus oxygen to the uteroplacental unit, with potentially deleterious consequences for a developing fetus, particularly later in gestation when somatic and brain growth are at their peak. By taking advantage of an extant anthropoid mode of invasive placentation, the human placenta could implant even more deeply and actively alter maternal vasculature to improve perfusion of the placenta, and hence the fetus would be protected from the vascular effects of gravity (Rockwell et al. 2003). One possible consequence of these placental adaptations to more global anatomical changes might be an increase in the flow of nutrients to the fetus, and in particular, the fetal brain, which may have contributed to dramatic evolutionary increases in relative brain size. In particular, invasiveness is related to the total amount of surface area at the interface between maternal and fetal circulations, indicating that an increase in invasiveness that was a response to locomotor constraints may have led to a largely expanded transport surface across which nutrients could flow more readily to the developing hominin fetus. These hypotheses suggest that human vulnerability to PPH and other placental disorders related to trophoblast invasiveness arose around the same time as routinely bipedal locomotion and intensified with the trend toward encephalization.

CONCLUSIONS, APPLICATIONS, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

PPH is the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide, exacting huge tolls on economic and human capital, particularly in those regions where women do not have ready access to medical care. Whereas the clinical literature on PPH has focused extensively on treatment modalities and the quantification of risk factors, comparatively little work has been done by the medical community to excavate the foundation of this potentially fatal disorder. We argue here that the high risk of PPH-related mortality in humans is a byproduct of unique placental adaptations toward intense invasiveness and radical remodeling of maternal vasculature. The transformed maternal uterine vessels allow maximum perfusion of the placenta, thus creating a generous conduit of maternal resources to the developing fetus, a developmental and evolutionary boon to hominin fetal somatic and brain growth. However, the transformative activity of the human trophoblast cells carries with it significant risk of gestational complications for both mother and offspring. We use the example of preeclampsia, a serious hypertensive complication of pregnancy caused by inadequate vascular remodeling of the uteroplacental unit, as a corollary for the etiology of PPH we propose here: that is, miss the target for adequate vascular remodeling and risk maternal hypertension and fetal undergrowth; overshoot the target—causing excessive remodeling, hyperperfusion of the placenta, and overnourishment of the fetus—and risk catastrophic maternal bleeding and maternal and fetal death. We suggest that although the human placenta shares deep phylogenetic roots with the primate hemochorial placenta, the highly invasive phenotype of the modern human placenta appears to be distinct from that of other primates, as indicated by available histological and physiological studies of the placenta, comparative data on pregnancy outcomes, and the time depth of PPH suggested by coagulation factor polymorphism distribution and ethnographic consilience in birth practices.

We have drawn from the available nonhuman literature on maternal mortality resulting from bleeding and other placental disorders. Unfortunately, the primate literature is currently inadequate to the task of completely rejecting the null hypothesis that humans do not differ from other primates, especially the African apes. Recent work by Anthony Carter, Robert Pijnenborg, and colleagues (Carter and Pijnenborg 2010; Pijnenborg et al. in press) has demonstrated that both the gorilla and chimpanzee term placenta do reflect an invasive mode of placentation that is similar, “although not necessarily identical,” to the human condition (Carter and Pijnenborg 2010:7). Further, Carter and Pijnenborg were unable to demonstrate highly invasive placentation in the orangutan placenta (Carter and Pijnenborg 2010). More detailed exploration of comparative primate placentation, fetal development, and maternal complications is needed to fully address these issues. However, even if it were to be definitively demonstrated that modern humans and the African apes, but not the orangutans, share an identically invasive placenta, this would offer tremendous insight into to the reproductive biology of the last common ancestor of the African hominoids. Perhaps more intriguing, in light of our hypothesis, would be if similarities in placentation were confirmed but incidence and severity of either PE or PPH were far greater in modern humans. This would indicate that the risk for placenta-related gestational complications is regulated by other critical factors, such as the timing and process of early invasive processes, relative fetal somatic and brain size, ratio of placental to fetal mass, relative maternal blood volume, coagulation factors, and behavioral adaptations.

Understanding the underlying cause of the increased risk of PPH in humans is a critical step toward discovering new modes of treatment and eventually prevention on a global scale. Whereas the medical community focuses on atony (loss of uterine contractility), the primary proximate risk factor for PPH during labor, our synthesis suggests that a focus on circulating biomarkers of trophoblast invasion during the period of intense invasion and remodeling—the first few weeks of the second trimester—may yield an early predictor of risk. Although the invasive trophoblasts do produce unique endocrine signatures that are assayable from maternal blood or urine, none has yet been investigated as potential markers of PPH risk. Biomarkers of PPH that could be used early in pregnancy would allow women to make informed decisions about their choice of birthing site and medical care based on their risk of PPH. Additionally, our synthesis calls into further question interventions that interfere with the uterus’s ability to contract and expel the placenta because of oxytocin dysregulation (e.g., for epidurals, see Rahm et al. 2002; for delayed initial breastfeeding, see Irons et al. 1994), particularly among women who may be more prone to hemorrhage because of population differences in coagulation factors.

We view an interdisciplinary approach to addressing the ultimate and proximate causes of PPH as an exemplar of applied evolutionary medicine and the emerging field of biomedical anthropology, with applications toward research, diagnosis, and treatment of PPH. Even more critically, women’s lives are at stake: over 100,000 women will die this year because of PPH. Over 50 percent of PPH cases have no identifiable risk factors (Kominiarek 2008), and the best predictor of PPH is previous PPH, which has disturbing implications for women in resource-poor settings. For the 37 percent of women who do not give birth attended by skilled attendants (United Nations 2010b), by the time it becomes evident that the postpartum bleeding is not attenuating, it may be too late to travel to a health center for treatment. Early diagnostics of PPH based on an understanding of evolutionary biology and physiological mechanisms will aid women in making informed choices about place of delivery to staunch the tide of PPH-related maternal deaths.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due Louis Keith and Christopher Jones for first bringing the evolutionary enigma of PPH to our attention. We thank the five anonymous reviewers and the American Anthropologist editorial staff who invested great effort in their critique of our manuscript; their comments led to a much-improved article. We are grateful to Crystal Patil, Alison Doubleday, Harvey Kliman, and Robert Martin for their thoughtful comments on previous drafts of our manuscript. Michelle Kominiarek and Stacie Geller, both of the UIC Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, offered important perspectives on the clinical treatment and global scope of PPH. Discussions with Anthony Carter and Steven Ross provided important information regarding birth outcomes in nonhuman primates. Dr. Melisa Burton provided the Spanish translation of the abstract; we are indebted to Deodatus Amedeus for the Swahili translation. We thank Fiona Lynch for preliminary research on this topic and Victoria deMartelly for her help with bibliographical matters. Final perspectives and errors remain ours alone. Significant financial support was provided by Wenner-Gren (Elizabeth Abrams and Crystal Patil) and by a University of Illinois at Chicago Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) faculty scholarship to Julienne Rutherford from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health (K12HD055892). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Maternal mortality, as defined by the WHO (2005), is mortality that occurs between conception and 42 days postpartum.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Abrams, Email: eabrams@uic.edu, Department of Anthropology, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60612.

Julienne Rutherford, Email: ruther4d@uic.edu, Department of Oral Biology, Comparative Primate Biology Laboratory, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60612.

REFERENCES CITED

- Abitbol M Maurice. Growth of the Fetus in the Abdominal Cavity. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1993;91(3):367–378. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330910309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angstmann Tobias, Gard Gregory, Harrington Tim, Ward Elizabeth, Thomson Amanda, Giles Warwick. Surgical Management of Placenta Accreta: A Cohort Series and Suggested Approach. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;202(1):38e1–38e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanassiades Andrew, Lala Peeyush K. Role of Placenta Growth Factor (PIGF) in Human Extravillous Trophoblast Proliferation, Migration and Invasiveness. Placenta. 1998;19(7):465–473. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(98)91039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker David J. Fetal Origins of Coronary Heart Disease. British Medical Journal. 1995;311(6998):171–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker David J. In Utero Programming of Chronic Disease. Clinical Science. 1998;95(2):115–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benirshcke Kurt, Kaufmann Peter. Anatomical and Functional Differences in the Placenta of Primates. Biology of Reproduction. 1982;26:29–53. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod26.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship Thomas N, Enders Allen C. Modification of Uterine Vasculature during Pregnancy in Macaques. Microscopy Reseach and Technique. 2003;60(4):390–401. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson Ellen, Deem Sharon L, Sanchez Carlos, Murray Suzan. Placental Retention in a Golden Lion Tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia) Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 2005;36(4):716–718. doi: 10.1638/04096.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroli Guillermo, Cuesta Cristina, Abalos Edgardo, Metin Gulmezoglu A. Epidemiology of Postpartum Haemorrhage: A Systematic Review. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;22(6):999–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter Anthony M, Martin Robert D. In press Comparative Anatomy and Placental Evolution. In: Pijnenborg Robert, Brosens Ivo, Romero Roberto., editors. Placental Bed Disorders: Basic Science and Its Translation to Obstetrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; [Google Scholar]

- Carter Anthony M, Pijnenborg Robert. Evolution of Invasive Placentation with Special Reference to Non-Human Primates. Best Practice and Research in Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2010.10.010. Epublication prior to printing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chafetz Ilana, Kuhnreich Ido, Sammar Marei, Tal Yossi, Gibor Yair, Meiri Hamutal, Cuckle Howard, Wolf Myles. First Trimester Placental Protein 13 Screening for Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197(1):35e.1–35.e.7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaline Jean. Increased Cranial Capacity in Hominid Evolution and Preeclampsia. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2003;59(2):137–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(03)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chez Ronald A. Nonhuman Primate Models of Toxemia of Pregnancy. Perspectives in Nephrology and Hypertension. 1976;5:421–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo Wang L, Chua Siew, Chong Yap Seng, Vanaja Kalaichelvan, Oei Pau-Ling, Ho Lisa M, Roy Ashim C, Arulkumaran S. Correlation of Change in Uterine Activity to Blood Loss in the Third Stage of Labour. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 1998;46(3):178–180. doi: 10.1159/000010028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensson Kyllike, Nilsson Bo A, Stock Solveig, Matthiesen Ann Sofie, Uvnäs-Moberg Kerstin. Effect of Nipple Stimulation on Uterine Activity and on Plasma Levels of Oxytocin in Full Term, Healthy, Pregnant Women. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1989;68(3):205–210. doi: 10.3109/00016348909020990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker Ahmet, Oliver Robert. Definitions and Classifications. In: B-Lynch Christopher, Keith Louis G, Lalonde André B, Karoshi Mahantesh., editors. A Textbook of Postpartum Hemorrhage: A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluation, Management and Surgical Intervention. Duncow, UK: Sapiens Publishing; 2006. pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cowans Nicholas J, Spencer Kevin, Meiri Hamutal. First Trimester Maternal Placental Protein 13 Levels in Pregnancies Resulting in Adverse Outcomes. Prenatal Diagnoses. 2008;28(2):121–125. doi: 10.1002/pd.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross James C, Hemberger Myriam, Lu Yong, Nozaki Tadashige, Whiteley Kathie J, Masutani Mitsuko, Lee Adamson S. Trophoblast Functions, Angiogenesis and Remodeling of the Maternal Vasculature in the Placenta. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2002;187(1–2):207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour Darna L, Sauther Michelle L. Comparative and Evolutionary Dimensions of the Energetics of Human Pregnancy and Lactation. American Journal of Human Biology. 2002;14(5):584–602. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders Allen C, Lantz Keith C, Schlafke Sandra. Preference of Invasive Cytotrophoblast for Maternal Vessels in Early Implantation in the Macaque. Acta Anatomica. 1996;155(3):145–162. doi: 10.1159/000147800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson John G, Kajantie Eero, Osmond Clive, Thornburg Kent, Barker David J. Boys Live Dangerously in the Womb. American Journal of Human Biology. 2010;22(3):330–335. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmans A, Gerris Jan, Corthout Erik, Verdonk Petra, Declercq S. Placenta Percreta Causing Rupture of an Unscarred Uterus at the End of the First Trimester of Pregnancy: Case Report. Human Reproduction. 2004;19(10):2401–2403. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza Jimmy, Romero Roberto, Kim Yeon Mee, Kusanovic Juan Pedro, Hassan Sonia, Erez Offer, Gotsch Francesca, Than Nandor Gabor, Papp Zoltan, Kim Chong Jai. Normal and Abnormal Transformation of the Spiral Arteries during Pregnancy. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 2006;34(6):447–458. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2006.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Suping. Management of Preterm Infants with Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Early Human Development. 2005;81(11):889–900. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher Susan J. The Placental Problem: Linking Abnormal Cytotrophoblast Differentiation to the Maternal Symptoms of Pre-Eclampsia. [accessed March 23, 2011.];Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2004 2:53. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-53. http://www.rbej.com/content/2/1/53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Garite Thomas J, Clark Reese, Thorp James A. Intrauterine Growth Restriction Increases Morbidity and Mortality among Premature Neonates. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(2):481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey Keith M, Barker David J. Fetal Programming and Adult Health. Public Health and Nutrition. 2001;4(2B):611–624. doi: 10.1079/phn2001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosser Otto. Vergleichende Anatomie und Entwicklungsgeschichte der Eihäute und der Placenta [Comparative anatomy of the fetal membranes and the placenta] Vienna, Austria: Wilhelm Braumüller; 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Haig David. Genetic Conflicts in Human Pregnancy. Quarterly Review of Biology. 1993;68(4):495–532. doi: 10.1086/418300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbwax Michel, Mahamba Crispin Kamate, Ngalula Anne-Marie, Andre Claudine. Placental Retention in a Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Journal of Medical Primatology. 2009;38(3):171–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2009.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawfield Amret, Freedman Barry I. Pre-Eclampsia: The Pivotal Role of the Placenta in Its Pathophysiology and Markers for Early Detection. Theraputic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease. 2009;3(1):65–73. doi: 10.1177/1753944708097114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemberger Myriam, Nozaki Tadashige, Masutani Mitsuko, Cross James C. Differential Expression of Angiogenic and Vasodilatory Factors by Invasive Trophoblast Giant Cells Depending on Depth of Invasion. Developmental Dynamics. 2003;227(2):185–191. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy Annemarie, Gillin Adrian G, Painter Dorothy M, Kirwan Paul J, Thompson John F, Horvath John S. Evidence for Preeclampsia in a Baboon Pregnancy with Twins. Hypertension in Pregnancy. 1997;16(2):223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Kim, Magdalena Hurtado A, Walker Robert S. High Adult Mortality among Hiwi Hunter-Gatherers: Implications for Human Evolution. Journal of Human Evolution. 2007;52(4):443–454. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irons DW, Sriskandabalan P, Bullough CHW. A Simple Alternative to Parenteral Oxytocics for the Third Stage of Labor. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1994;46(1):15–18. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(94)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson Thomas, Powell Theresa L. Human Placental Transport in Altered Fetal Growth: Does the Placenta Function as a Nutrient Sensor? A Review. Placenta. 2006;27(Supp A):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux Eric, Poston Lucilla, Burton Graham J. Placental-Related Diseases of Pregnancy: Involvement of Oxidative Stress and Implications in Human Evolution. Human Reproduction Update. 2006;12(6):747–755. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann Peter. Vergleichend-Anatomische und Funktionelle Aspekte des Placenta-Baues [Comparative anatomical and functional aspects of placental structure] Funktionelle Biologie and Medizin [Functional Biology and Medicine] 1983;2:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann Peter, Black Simon, Huppertz Berthold. Endovascular Trophoblast Invasion: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Intrauterine Growth Retardation and Preeclampsia. Biology of Reproduction. 2003;69(1):1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Khalid S, Wojdyla Daniel, Say Lale, Gulmezoglu A Metin, Van Look Paul FA. WHO Analysis of Causes of Maternal Death: A Systematic Review. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1066–1074. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Rehan U, El-Refaey Hazem. Pathophysiology of Postpartum Hemorrhage and Third Stage of Labor. In: B-Lynch Christopher, Keith Louis G, Lalonde André B, Karoshi Mahantesh., editors. A Textbook of Postpartum Hemorrhage. Duncow, UK: Sapiens Publishing; 2006. pp. 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger Shelia. The Social Context of Birth: Some Comparisons between Childbirth in Jamaica and Britain. In: MacCormack C, editor. Ethnography of Fertility and Birth. New York: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kliman Harvey J. Uteroplacental Blood Flow. The Story of Decidualization, Menstruation, and Trophoblast Invasion. American Journal of Pathology. 2000;157(6):1759–1768. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64813-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliman Harvey J, Sammar Mari, Grimpel Yael, Lynch Stephanie K, Milano Kristin, Pick Elah, Bejar Jacob, et al. Unpublished MS. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yale School of Medicine; N.d. Placental Protein 13 and Decidual Zones of Necrosis: An Immunologic Diversion That May Be Linked to Preeclampsia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kominiarek Michelle A. Postpartum Hemorrhage. Hospital Physicians Obstetrics and Gynecology Board Review Manual. 2008;11:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk Margaret E, Paczkowski Magdalena, Mbaruku Godfrey, de Pinho Helen, Galea Sandro. Women’s Preferences for Place of Delivery in Rural Tanzania: A Population-Based Discrete Choice Experiment. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(9):1666–1672. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzawa Christopher W, Adair Linda S. A Supply-Demand Model of Fetal Energy Sufficiency Predicts Lipid Profiles in Male but Not Female Filipino Adolescents. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;58(3):438–448. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde Andre B, Daviss Betty-Anne, Acosta Andreina, Herschderfer Kathy. Postpartum Hemorrhage Today: ICM/FIGO Initiative 2004–2006. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2006;94(3):243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefèber Yvonne, Voorhoeve Henk WA. Assen. the Netherlands: Van Gorcum and Company; 1998. Indigenous Customs in Childbirth and Child Care. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist Pelle G, Dahlback Bjorn. Carriership of Factor V Leiden and Evolutionary Selection Advantage. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;15(15):1541–1544. doi: 10.2174/092986708784638852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist Pelle G, Svensson Peter J, Dahlback Bjorn, Marsal Karel. Factor V Q506 Mutation (Activated Protein C Resistance) Associated with Reduced Intrapartum Blood Loss: A Possible Evolutionary Selection Mechanism. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 1998;79(1):69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckett W Patrick. Comparative Development and Evolution of the Placenta in Primates. Contributions to Primatology. 1974;3:142–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckett W Patrick. Cladistic Relationships among Primate Higher Categories: Evidence of the Fetal Membranes and Placenta. Folia Primatologica. 1976;25(4):245–276. doi: 10.1159/000155719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydakis Charalampos, Beevers Michele, Gareth Beevers D, Lip Gregory YH. The Prevalence of Pre-Eclampsia and Obstetric Outcome in Pregnancies of Normotensive and Hypertensive Women Attending a Hospital Specialist Clinic. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2001;55(6):361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj B, Moodley Jack. Management of Hypertension in Pregnancy. Continuing Medical Education. 1994;12:1581–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Makris Antois, Thornton Charlene, Thompson John, Thomson Steven, Martin Robert, Ogle Robert, Waugh Robbie, McKenzie Patrick, Kirwan Patrick, Hennessy Annemarie. Uteroplacental Ischemia Results in Proteinuric Hypertension and Elevated sFLT-1. Kidney International. 2007;71(10):977–984. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Robert D. Human Reproduction: A Comparative Background for Medical Hypotheses. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2003;59(2):111–135. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(03)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Robert D. The Evolution of Human Reproduction: A Primatological Perspective. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2007;134(Supplement 45):59–84. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Robert D. Human Brain Evolution in an Ecological Context. In: Martin Robert D., editor. Fifty-Second James Arthur Lecture on the Evolution of the Human Brain. New York: American Museum of Natural History; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli Ida, Bucciarelli Paolo, Mannucci Pier Mannuccio. Thrombotic Risk Factors: Basic Pathophysiology. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38(Supp 2):3–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c9cbd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathai Matthews, Metin Gülmezoglu A, Hill Suzanne. Saving Women’s Lives: Evidence-Based Recommendations for the Prevention of Postpartum Haemorrhage. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007;85:322–323. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald Susan. Management of the Third Stage of Labor. American Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2007;52(3):254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Lisa E, Gonzalez Ileana. Placenta Percreta with Bladder Invasion Diagnosed with Sonography: Images and Clinical Correlation. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 2008;24:238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Mossman Harland W. Comparative Morphogenesis of the Fetal Membranes and Accessory Uterine Structures. Carnegie Institution Washington Publication 479. Contributions to Embryology. 1937;26(479):129–246. [Google Scholar]

- Mossman Harland W. Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Noakes David E, Arthur Geoffrey H, Parkinson Timothy J, England Gary CW. Arthur’s Veterinary Reproduction and Obstetrics. 8. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Obama Barack. Statement by the President on Global Health Initiative. The White House, Office of the Press Secretary; 2009. May 5, [accessed December 2, 2010.]. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/statement-president-global-health-initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg Robert, D’Hooghe T, Vercruysse Lisbeth, Bambra Clare. Evaluation of Trophoblast Invasion in Placental Bed Biopsies of the Baboon, with Immunohistochemical Localisation of Cytokeratin, Fibronectin, and Laminin. Journal of Medical Primatology. 1996;25(4):272–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg Robert, Vercruysse Lisbeth, Carter Anthony. Placenta. Deep Trophoblast Invasion and Spiral Artery Remodelling in the Placental Bed of the Chimpanzee. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg Robert, Vercruysse Lisbeth, Hanssens Myriam. The Uterine Spiral Arteries in Human Pregnancy: Facts and Controversies. Placenta. 2006;27(9):939–958. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahm Vivi-Anne, Hallgren Anita, Högberg Hans, Hurtig Ingalill, Odlind Viveca. Plasma Oxytocin Levels in Women during Labor with or without Epidural Analgesia: A Prospective Study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2002;81(11):1033–1039. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.811107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey Elizabeth M, Houston Marshall L, Harris John W. Interactions of the Trophoblast and Maternal Tissues in Three Closely Related Primate Species. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1976;124(6):647–652. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson Lucy, Wu Olivia, Langhorne Peter, Twaddle Shona, Clark Peter, Lowe Gordon D, Walker Isobel D, et al. Thrombophilia in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. British Journal of Haematology. 2006;132(2):171–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robillard Pierre-Yves, Dekker Gustaaf A, Hulsey Thomas C. Evolutionary Adaptations to Pre-Eclampsia/Eclampsia in Humans: Low Fecundability Rate, Loss of Oestrus, Prohibitions of Incest and Systematic Polyandry. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2002;47(2):104–111. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2002.1o043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell L Christie, Vargas Enrique, Moore Lorna G. Human Physiological Adaptation to Pregnancy: Inter- and Intraspecific Perspectives. American Journal of Human Biology. 2003;15(3):330–341. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronsmans Carine, Graham Wendy J. Maternal Mortality: Who, When, Where, and Why. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney James R. Internal Hemorrhage Related to Gestation in The Mare. The Cornell Veterinarian. 1964;54:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg Karen, Trevathan Wenda. An Anthropological Perspective on the Evolutionary Context of Preeclampsia in Humans. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2007;76(1–2):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford Julienne N. Fetal Signaling through Placental Structure and Endocrine Function: Illustrations and Implications from a Nonhuman Primate Model. American Journal of Human Biology. 2009;21(6):745–753. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks David A, Chen Wansu. Estimating Fetal Weight in the Management of Macrosomia. Obstetrical and Gynecological Surgery. 2000;55(4):229–239. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200004000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintaku Masayuki, Hwang Moon Hee, Amitani Ryoichi. Primary Choriocarcinoma of the Lung Manifesting as Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 2006;130(4):540–543. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-540-PCOTLM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Harriet O, Kohorn Ernest I, Cole Laurence A. Choriocarcinoma and Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2005;32(4):661–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina Vincenzo, Aleandri Vincenzo, Morini Francesco. The Impact of the Factor V Leiden Mutation on Pregnancy. Human Reproduction Update. 2000;6(3):301–306. doi: 10.1093/humupd/6.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout Charlotte, Lemmon William Burton. Glomerular Capillary Endothelial Swelling in a Pregnant Chimpanzee. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1969;105(2):212–215. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(69)90060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Tony Y, Yeo George S. Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;17(2):135–142. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000162181.61102.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Than Nandor G, Pick Elah, Bellyei Szabolcs, Szigeti Andras, Burger Ora, Berente Zoltan, Janaky Tamas, et al. Functional Analyses of Placental Protein 13/Galectin-13. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2004;271(6):1065–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Jim G, Onwude Joseph. Convulsions in Pregnancy in Related Gorillas. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;167(1):240–241. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen Minna. Etiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Prediction of Placental Abruption. Acta Obstetrica and Gynecologia Scandinavia. 2010;89(6):732–740. doi: 10.3109/00016341003686081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevathan Wenda. Human Birth: An Evolutionary Perspective. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2008. United Nations; 2010a. [accessed March 18]. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241500265_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goal Statistical Annex. United Nations; 2010b. [accessed December 3.]. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/mdg/Resources/Static/Data/2010%20Stat%20Annex.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lerberghe Wim, De Brouwere Vincent. Of Blind Alleys and Things That Have Worked: History’s Lessons on Reducing Maternal Mortality. Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy. 2001;17:7–34. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization) Beyond the Numbers: Reviewing Maternal Deaths and Complications to Make Pregnancy Safer. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [accessed April 13, 2011]. http://www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/documents/9241591838/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization) The World Health Report: 2005: Make Every Mother and Child Count. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [accessed April 13, 2011]. http://www.who.int/whr/2005/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization) WHO Recommendations for the Prevention of Postpartum Haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [accessed April 13, 2011]. http://www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/documents/who_mps_0706/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Wislocki George B. On the Placentation of Primates, with a Consideration of the Phylogeny of the Placenta. Carnegie Institute Contributions to Embryology. 1929;20:51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zivelin Ariella, Mor-Cohen Ronit, Kovalsky Victoria, Kornbrot Nurit, Conard Jacqueline, Peyvandi Flora, Kyrle Paul A, et al. Prothrombin 20210G>A Is an Ancestral Prothrombotic Mutation That Occurred in Whites Approximately 24,000 Years Ago. Blood. 2006;107(12):4666–4668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FOR FURTHER READING

(These selections were made by the American Anthropologist editorial interns as examples of research related in some way to this article. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the author.)

- Fleuriet K Jill. La Tecnología y Las Monjitas: Constellations of Authoritative Knowledge at a Religious Birthing Center in South Texas. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2009;23(3):212–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2009.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettler Lee T. Direct Male Care and Hominin Evolution: Why Male–Child Interaction Is More Than a Nice Social Idea. American Anthropologist. 2010;112(1):7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen Edward H, Clark Barrett H. Perinatal Sadness among Shuar Women: Support for an Evolutionary Theory of Psychic Pain. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2007;21(1):22–40. doi: 10.1525/maq.2007.21.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald Margaret. Gender Expectations: Natural Bodies and Natural Births in the New Midwifery in Canada. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2006;20(2):235–256. doi: 10.1525/maq.2006.20.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland Claire L. The Vanishing Mother: Cesarean Section and “Evidence-Based Obstetrics”. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2007;21(2):218–233. doi: 10.1525/maq.2007.21.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]