Abstract

Although the role of single gene and chromosomal disorders in pediatric illness has been recognized since the 1970s, there are few data describing the impact of these often severe disorders on the health of the adult population. In this study, we present population data describing the impact of single gene and chromosomal disorders on hospital admissions of patients aged 20 years and over in Western Australia between 2000 and 2006. The number, length, and cost of admissions were investigated and compared between disease categories and age groups and to hospital admissions for any reason. In total, 73,211 admissions and 8,032 patients were included in the study. The most costly disorders were cystic kidney disease, α-1 anti-trypsin deficiency, hemochromatosis, von Willebrand disease, and cystic fibrosis. Overall, patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders represented 0.5% of the patient population and were responsible for 1.9% of admissions and 1.5% of hospital costs. These data will enable informed provision of health care services for adults with single gene and chromosomal disorders in Australia.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12687-011-0043-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Single gene disorders, Chromosomal disorders, Adult, Hospital admission, Hospital costs

Introduction

Previous studies investigating the impact of genetic disease on hospital admissions have reported that 5–12% of all admissions in children were due to single gene or chromosomal disorders, and that patients with these conditions had more admissions, longer hospital stays, and increased morbidity and mortality than other patients (Day and Holmes 1973; FitzPatrick et al. 1991; Hall et al. 1978; Kumar et al. 2001; McCandless et al. 2004; Meguid et al. 2003; Scriver et al. 1973; Stanley et al. 2009; Yoon et al. 1997). Given that estimates of the population prevalence of single gene and chromosomal disorders range from 0.4% to 2.0% (Baird et al. 1988; Rimoin and Conner 2002; Trimble and Doughty 1974), it is clear that children with single gene and chromosomal disorders account for a disproportionately large number of hospital admissions.

Intuitively, it might be expected that single gene and chromosomal disorders will account for a smaller proportion of hospitalizations in the adult population, as some affected individuals might not survive childhood, and the prevalence of multifactorial, chronic disease increases in the general population with age. However, few studies have investigated the impact of single gene and chromosomal disease in adults. Day and Holmes (1973) found that 1.5% of adult hospital admissions were for people with a single gene or chromosomal disorder. However, their sample size was small (200 inpatient and 200 outpatient admissions) and represented admissions during 20 days in 1970. Giampietro et al. (2006) investigated acute health events identified in emergency department, urgent care and primary care settings of 527 adult patients with single gene, chromosomal and syndromic conditions in 2003. This study found that 1.2% of the total adult patients in the catchment area had a single gene or chromosomal disorder, and these patients accounted for 1.8% of the total outpatient visits during the study period (Giampietro et al. 2006). Chromosomal disorders (e.g. Down syndrome), hematological conditions, connective tissue disorders, and muscular dystrophies contributed the highest proportions of acute health events.

The current study assessed hospital admissions of adult patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders between 2000 and 2006 using the hospital morbidity population database available in Western Australia (WA). WA is a state of Australia with a population of 2.28 million, accounting for approximately 10% of the national total (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010). In 2008, approximately 74% of the population resided in the metropolitan area, 20% in regional areas, and 6% in remote locations (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2008), and in 2006, more than 95% of Western Australians identified themselves as being of Australian, British, Irish, or European heritage.

WA has a land area of 2.5 million square kilometers and Perth, the capital city, is 3,500 km away from the large population bases of Melbourne and Sydney in eastern Australia. Thus, it is likely that the vast majority of hospital admissions of WA patients occurs in WA hospitals and would be captured by the WA Hospital Morbidity Data System. This database is part of the WA Data Linkage System (Holman et al. 2008) and contains information about all inpatient admissions to public and private hospitals in WA since 1970.

This study focuses on single gene and chromosomal disorders, rather than a broader definition of genetic diseases, which could include multifactorial disorders and those with a known genetic pre-disposition. This is because the distinction between genetic and non-genetic conditions has become increasingly difficult to define, with evidence that even infectious disease has a genetic component (Casanova and Abel 2007; Davila and Hibberd 2009). Single gene and chromosomal disorders are easier to diagnose and define, and the fraction of their hospital needs related specifically to their disorder is likely to be high. We investigated the number and cost of all adult hospital admissions due to single gene and chromosomal disorders, age-related trends in admissions, the specific disorders associated with the highest costs, and the most common procedures associated with these admissions.

Our data represents over 8,000 patients and 73,000 admissions, and to our knowledge, is the largest study investigating the health of adults with single gene and chromosomal disorders published to date. The aim of this study was to increase awareness among patients, families, and clinicians about the health care needs of adults with these disorders and inform planning and provision of health care services.

Methods

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM; ICD-10) (2004) was used to identify 296 diagnosis codes specific to single gene and chromosomal disorders (Online Resource 1). These diagnosis codes refer to groups of disorders and include several thousand different single gene and chromosomal disorders, many of which are rare. Although the ICD-10-AM contains some Australian-specific disease codes and Australian extensions, the majority of ICD-10-AM diagnosis codes used in this study were identical to ICD-10 codes. The exceptions were some of the multi-system syndromes, and in these cases, the ICD-10-AM code was mapped to the code immediately above it in the hierarchy of both classifications. As data in this study were analyzed using higher-level classifications, it can be compared to other studies using both the ICD-10 and ICD-10-AM.

The WA Hospital Morbidity Data system (Holman et al. 2008) was searched electronically for any individual 20 years of age or older who had at least one of the selected ICD-10-AM codes recorded in the diagnosis fields between 2000 and 2006. The data extracted for each patient were de-identified and included the number of same-day versus overnight admissions; the mean length of stay (LOS) of overnight admissions; the cost of all admissions and the ICD-10-AM procedural codes associated with each admission. Same-day admissions are defined as admissions where a patient is in hospital for less than 1 day (that is, does not stay overnight). Costs in Australian dollars (AUD) were calculated by applying year-specific average cost weights to the Australian Refined Diagnosis-Related Group (AR-DRG) of each admission (Australian Government Department of Health and Aging 2000–2006). Each hospital admission is assigned a diagnosis related group (DRG) and each DRG represents a group of patients with similar clinical characteristics requiring comparable hospital services. Year-specific cost weights were applied to DRGs via the National Hospital Data Collection, which contains hospital costs for a given financial year. Costs were adjusted to a reference year of 2007–2008 using total health price index deflators (Australian Institute of Heatlh and Welfare 2009) and converted to US dollars using the average exchange rate for the 2007–2008 financial year (http://www.oanda.com).

Data were also extracted from the WA Morbidity Data System for all patients 20 years or older in WA who were admitted to hospital between 2000 and 2006. Statistics extracted included the total number of patients, total admissions, mean LOS, and costs, which were calculated as for the cases.

The data were examined both by type of disorder and by age group. One-year data sets were used to investigate admissions by age group to limit each individual to a single category. The one-year datasets were then compared to all admissions in WA in that year. Five-year age groups were used from 20–84 years, with adults over 85 years in a single category. The five-year age groupings are commonly used in health and hospital statistics and allowed comparison of our data to publicly available health data. In most cases, these categories were collapsed down to 20–39, 40–59, 60–79, and 80 plus years, representing young, middle, and older adulthood.

The project received ethics approval from the Department of Health of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (project number 200723) and the University of Western Australia Ethics Committee (reference number RA/4/1/1801).

Results

Between 2000 and 2006, 8,032 patients aged 20 years and over with a single gene or chromosomal disorder were admitted to hospital in WA and accounted for 73,211 admissions. This represented 0.6% of the total number of patients and 1.9% of all admissions in WA during that period. The mean number of admissions per patient was 9.1, and the mean length of stay (LOS) for overnight admissions was 12.6 days (Table 1). Neuromuscular disorders were associated with the longest hospital stays (mean LOS 22.1 days), followed by eye, endocrine, and metabolic disorders. Overall, 73% of genetic admissions were same-day separations, although this proportion decreased to 58% if urinary system disorders were excluded (44% of total admissions were due to disorders of the urinary system, and 93% of these were same-day admissions). The most costly groups of single gene and chromosomal disorders were metabolic, blood, urinary, neuromuscular, and multi-system syndromes, which together accounted for 89% of patients, 94% of admissions, and 91% of costs due to genetic disorders. The total cost associated with hospital admissions of adults with single gene and chromosomal disorders in WA 2000–2006 was 214,219,273 USD, which was 1.5% of total hospital expenditure (13,837,351,138 USD). The mean cost per genetic admission was 2,926 USD (range, 1,101 to 11,977 USD), which rose to 4,346 USD if diseases of the urinary system were excluded.

Table 1.

Number of patients, admissions and LOS of patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders, by type of disease (2000–2006)

| Patients | Admissions | Same-day admissionsa | Overnight admissionsa | Mean admissions per patient | Mean LOS | Total cost USDb | Cost per patientb | Cost per admissionb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease of blood and blood-forming organs | 2,516 | 11,339 | 5,850 (0.52) | 5,489 (0.48) | 4.5 | 8.0 | 50,040,858 | 19,889 | 4,413 |

| Disorders of the immune system | 46 | 471 | 368 (0.78) | 103 (0.22) | 10.2 | 4.3 | 1,230,111 | 26,742 | 2,612 |

| Endocrine disorders | 240 | 1,181 | 608 (0.51) | 573 (0.49) | 4.9 | 12.3 | 5,439,362 | 22,664 | 4,606 |

| Metabolic disorders | 2,276 | 14,992 | 9,446 (0.63) | 5,546 (0.37) | 6.6 | 11.4 | 68,300,642 | 30,009 | 4,556 |

| Neuromuscular disorders | 1,222 | 5,204 | 2,012 (0.39) | 3,192 (0.61) | 4.2 | 22.1 | 31,085,793 | 25,438 | 5,973 |

| Diseases of the eye | 259 | 1,113 | 728 (0.65) | 385 (0.35) | 4.3 | 15.6 | 3,544,616 | 13,686 | 3,185 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 63 | 392 | 233 (0.59) | 159 (0.41) | 6.2 | 4.2 | 1,184,996 | 18,809 | 3,023 |

| Disorders of tooth development | 133 | 271 | 144 (0.53) | 127 (0.47) | 2.0 | 2.3 | 962,826 | 7,239 | 3,553 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 1 | 6 | 1 (0.17) | 5 (0.83) | 6.0 | 6.3 | 71,862 | 71,862 | 11,977 |

| Disease of the urinary system | 465 | 32,036 | 29,951 (0.93) | 2,085 (0.07) | 68.9 | 7.0 | 35,285,352 | 75,882 | 1,101 |

| Diseases of the skeletal system | 137 | 644 | 288 (0.45) | 356 (0.55) | 4.7 | 8.3 | 3,161,989 | 23,080 | 4,910 |

| Diseases of the skin | 21 | 85 | 39 (0.46) | 46 (0.54) | 4.0 | 7.5 | 335,783 | 15,990 | 3,950 |

| Multi-system syndromes | 653 | 5,477 | 4,138 (0.76) | 1,339 (0.24) | 8.4 | 9.2 | 13,575,082 | 20,789 | 2,479 |

| Total | 8,032 | 73,211 | 53,806 (0.73) | 19,405 (0.27) | – | – | 214,219,273 | – | – |

| Mean | – | – | – | – | 9.1 | 12.6 | – | 26,671 | 2,926 |

LOS length of stay of overnight patients only

aProportion of admissions due to same-day and overnight admission in each disease category is in brackets

bCost in US dollars 2007–2008

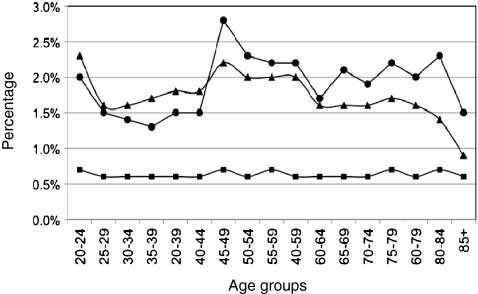

Patients with single gene or chromosomal disorders were also analyzed by age group, and the data compared to all patients admitted to hospital in WA in 2000 and 2006. Similar data were obtained for both years and 2006 was selected as representative. In 2006, patients with genetic diseases accounted for 0.6% of patients, 1.9% of admissions, and 1.7% of total costs (Tables 2 and 3; Online Resources 2, 3, and 4). The proportion of patients classified as having a genetic disorder was stable during adulthood, but the proportion of admissions and costs due to genetic disorders varied (Fig. 1, Online Resource 4). The proportion of admissions due to genetic diseases was relatively high in patients aged 20–24, decreased in adults aged 25–44, and increased again in patients aged approximately 45 years and older. The proportion of costs due to genetic disorders followed a similar trend to admissions but decreased in adults aged 60 years or more.

Table 2.

Number of patients, admissions, LOS, and costs of patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders, by age group in 2006

| Age groups | Patients | Total admissions | Same-day admissionsa | Overnight admissionsa | Mean admissions per patient | Mean LOS | Total costb | Cost per patientb | Cost per admissionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 | 586 | 2,343 | 1,554 (0.66) | 789 (0.34) | 4.0 | 7.7 | 9,536,063 | 16,273 | 4,070 |

| 40–59 | 646 | 4,519 | 3,679 (0.81) | 840 (0.19) | 7.0 | 14.8 | 12,322,904 | 19,076 | 2,727 |

| 60–79 | 550 | 4,217 | 3,306 (0.78) | 911 (0.22) | 7.6 | 13.8 | 12,660,038 | 23,018 | 3,002 |

| 80+ | 187 | 1,390 | 1,000 (0.72) | 390 (0.28) | 7.4 | 21.4 | 4,015,376 | 21,473 | 2,889 |

| Total/mean | 1,969 | 12,469 | 9,539 (0.78) | 2,930 (0.22) | 6.3 | 12.6 | 38,534,381 | 19,571 | 3,090 |

For data regarding all patients, refer to Table 3

LOS length of stay of overnight patients only

aProportion of admissions due to same-day and overnight admission in each age group is shown in brackets

bCost in US dollars 2007–2008

Table 3.

Number of patients, admissions, LOS, and costs of all patients in WA, by age group in 2006

| Age groups | Patients | Total admissions | Same-day admissionsa | Overnight admissionsa | Mean admissions per patient | Mean LOS | Total costb | Cost per patientb | Cost per admissionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 | 95,316 | 152 622 | 71,037 (0.47) | 81,585 (0.53) | 1.6 | 4.5 | 534,426,929 | 5,607 | 3,502 |

| 40–59 | 100,078 | 204,530 | 131,319 (0.64) | 73,211 (0.36) | 2.0 | 5.1 | 621,087,070 | 6,206 | 3,037 |

| 60–79 | 84,621 | 214,729 | 133,861 (0.62) | 80,868 (0.38) | 2.5 | 7.3 | 788,973,872 | 9,324 | 3,674 |

| 80+ | 27,727 | 71,545 | 28,192 (0.39) | 43,353 (0.61) | 2.6 | 10.9 | 351,317,556 | 12,671 | 4,910 |

| Total/mean | 307,742 | 643,426 | 364,409 (0.57) | 279,017 (0.43) | 2.1 | 6.4 | 2,295,802,427 | 7,460 | 3,568 |

LOS length of stay of overnight patients only

aProportion of admissions due to same-day and overnight admission in each age group is shown in brackets

bCost in US dollars 2007–2008

Fig. 1.

The proportion of total patients, admissions, and expenditure due to single gene and chromosomal disorders in WA hospitals in 2006. Squares patients, circles admissions, triangles costs

The cost per admission of patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders versus all patients was similar overall, with a mean of 3,090 USD for genetic admissions and 3,568 USD for all admissions in 2006 (Tables 2 and 3, Fig. 2, Online Resources 2 and 3). Same-day admissions accounted for a higher proportion of admissions in patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders compared to all patients. However, the mean length of stay for overnight admissions and the mean number of admissions was higher for patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders compared to all patients, and the cost per genetic patient was at least double that of all patients across all age groups from 20–80 years. The cost per patient with a single gene or chromosomal disorder showed an overall increase with age, with peaks at 50–54 and 75–79 years, while the cost per patient of all patients rose linearly from about 50 years (Fig. 2, Online Resources 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Cost per patient and per admission for patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders versus all patients in WA in 2006. Closed triangles genetic admissions, open triangles all admissions, closed squares genetic patients, open squares all patients

Next, we examined which specific genetic disorders affected the most patients and were the largest contributors to hospital admissions and costs in WA between 2000 and 2006 (Table 4). The most costly genetic disorder in the adult population was cystic kidney disease (CKD) (Q61), which accounted for all hospital admissions due to genetic diseases of the urinary system. CKD accounted for 44% of admissions and 16.5% of the total costs due to genetic disease. The cost per admission of patients with CKD was low compared to other disorders, but the cost per patient was high due the large number of same-day admissions per patient. The overall cost associated with CKD was relatively low in adults aged less than 35 years but increased tenfold to peak in patients aged 50–60 years before declining again (Fig. 3a). When procedural codes for CKD admissions were examined, it was found that 89.5% of admissions were for hemodialysis, and a small number of admissions were associated with renal transplantation, and education and training about home dialysis.

Table 4.

The number of patients, hospital admissions, and costs of the ten most expensive genetic disorders in adult patients in WA, 2000–2006

| Genetic disorder (ICD10-AM code) | Total costa | Number of patients | Number of admissions | Cost per patienta | Cost per admissiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cystic kidney disease, Q61 | 35,285,352 | 465 | 32,036 | 75,882 | 1,101 |

| α-1 anti-trypsin deficiency, E880 | 20,514,501 | 558 | 2,871 | 36,764 | 7,145 |

| Disorders of iron metabolism, E831 | 17,485,002 | 819 | 6,184 | 21,349 | 2,827 |

| Von Willebrands disease, D680 | 13,505,919 | 826 | 2,985 | 16,351 | 4,525 |

| Cystic fibrosis, E84 | 12,119,967 | 98 | 1,357 | 123,673 | 8,931 |

| Deficiency of clotting factors, D682 | 9,011,559 | 477 | 1,926 | 18,892 | 4,679 |

| Thalassemia, D56 | 8,252,294 | 375 | 2,618 | 22,006 | 3,152 |

| Hereditary ataxia, G11 | 5,842,837 | 272 | 985 | 21 481 | 5932 |

| Down syndrome, Q90 | 4,689,666 | 286 | 1,913 | 16,397 | 2,451 |

| Hemolytic anemias, D58 | 4,633,476 | 194 | 954 | 23,884 | 4,857 |

aCost in USD 2007–2008

Fig. 3.

Total costs for specific single gene disorders, by age group, 2000–2006: aclosed squares CKD, closed triangles disorders of iron metabolism, closed circles α-1 anti-trypsin deficiency, open squares CF; bclosed squares vWD, closed triangles deficiency of clotting factors (excluding factors VIII, IX, and XI), open squares thalassemia, closed circles hereditary hemolytic anemias (excluding thalassemia, sickle cell disorders, and hereditary spherocytosis); cclosed squares DS, closed circles hereditary ataxia

Of the ten most expensive disorders, three were endocrine or metabolic disorders and accounted for 9.5%, 8%, and 5.5% of the costs associated with single gene and chromosomal disorders, respectively: α-1 anti-trypsin (AAT) deficiency (E880), disorders of iron metabolism (e.g., hemochromatosis) (E831), and cystic fibrosis (CF) (E84) (Table 4). The cost trends of these three disorders differed significantly. Costs due to α-1 anti-trypsin deficiency were low in adults less than 40 years and increased steadily to peak in adults aged 75–79 years, whereas in CF, adults aged 20–39 years incurred 80% of the costs (Fig. 3a). The costs associated with hemochromatosis showed a similar trend to CKD and peaked in adults in the 50–69-year age group (Fig. 3a). The most common procedural codes associated with admissions due to AAT deficiency were hemodialysis (16% of admissions) and physiotherapy (5%), while 16% of admissions were not associated with a coded procedure. Hospital admissions due to disorders of iron metabolism were associated with procedures such as therapeutic venesection (51% of admissions), hemodialysis (8%), and transfusion of packed cells (11%); while admissions coded as CF involved central vein catheterization (28%), hemodialysis (24%), and physiotherapy (7%).

Diseases of blood and blood-forming organs accounted for four of the ten most costly disorders, with von Willebrand disease (vWD) (D680), hereditary deficiency of other clotting factors (excluding factors VIII, IX, and XI) (D682), thalassemia (D56), and hereditary hemolytic anemias (excluding thalassemia, sickle cell disorders, and hereditary spherocytosis) (D58) accounting for 6.2%, 4.1%, 3.8%, and 2.1% of the total costs of single gene and chromosomal disorders, respectively (Table 4). The costs associated with vWD were relatively constant throughout early and middle adulthood, before declining in adults >55 years of age (Fig. 3b). The costs associated with thalassemia were highest in young adults (< 40 years), while disorders of other clotting factors were relatively consistent throughout adulthood. Hemolytic anemias were associated with relatively low costs overall which increased with increasing age (Fig. 3b). The main procedural codes associated with thalassemia were transfusion of packed cells (42%) and hemodialysis (19%). The transfusion of packed cells was also the most common procedure for admissions coded as hereditary hemolytic anemias (D58) (22% of admissions), whereas the hereditary deficiency of other clotting factors (D682) was associated with hemodialysis in patients over 60 years (28% of total admissions). Procedural codes associated with admissions of patients with vWD did not show any major trends, with 15% not associated with any code, 10% with intravenous administration or injection of an unspecified therapeutic agent, and 5.7% with hemodialysis.

Hereditary ataxia (G11) and Down syndrome (Q90) were the 8th and 9th most costly genetic disorders. Costs associated with Down syndrome peaked sharply in patients approximately 40 years of age and declined to virtually nothing in patients aged 65 years and over. The costs of patients with hereditary ataxia increased relatively steadily throughout adulthood until 65 years and then declined (Fig. 3c). Over half of DS admissions involved hemodialysis (54%), with further investigation revealing the vast majority of these admissions were due to one or two patients, while 13% were not associated with a procedure code. The most common procedures associated with hereditary ataxia admissions included physiotherapy (15%) and occupational therapy (7.5%), while 22.5% of admissions were not associated with a code.

A number of other groups of disorders were also associated with significant patient numbers, admissions and costs, although individually, specific disorders within these groups were not in the most expensive diseases described above. These groups of disorders included G71 (primary disorders of muscle, including a range childhood and adult-onset muscular dystrophies, myotonic dystrophy, and mitochondrial myopathies); Q87 (congenital malformations affecting multiple systems, including Marfan's, Goldenhar, Noonan, Prader–Willi and Alport syndromes); Q85 (phakomatoses, including neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis and von Hippel–Lindau syndrome); E74 (disorders of carbohydrate metabolism including glycogen storage diseases); and E75 (disorders of sphingolipid metabolism and other lipid storage disorders including Tay Sachs, Fabry, and Gaucher's disease).

Discussion

Overall, 0.6% of adult patients admitted to hospital in WA for the period 2000–2006 had a single gene or chromosomal disorder, and these patients accounted for 1.9% of admissions and 1.5% of hospital costs. These data are similar to that reported by Day and Holmes (1973) who found that 1.5% of adult admissions were for patients with genetic disease, and Giampietro et al. (2006) who reported that 1.2% of patients had a single gene or chromosomal disorder and accounted for 1.8% of admissions. Thus, the proportion of adult hospital admissions due to single gene and chromosomal disorders appears to be consistent across different populations, over time, and in different clinical settings; as Day and Holmes (1973) reported on inpatient and outpatient data from Massachusetts during 1970, and Giampietro et al. (2006) collected data from acute health care settings in Wisconsin in 2003. In addition, these data are consistent with a population prevalence of single gene and chromosomal disorders of 0.5–1.0%, as has been reported for Caucasian populations (Baird et al. 1988; Carter, 1977; Trimble and Doughty 1974).

Our data and those of Giampietro et al. (2006) also identified a number of the same diseases as being significant contributors to hospital admissions. For example, some of the most common disorders in the Marshfield study were hematological diseases (e.g., von Willebrand disease, Factor V Leiden), which accounted for nearly 22% of patients; chromosomal syndromes (e.g., Down syndrome and sex chromosome abnormalities) (11% of patients); and renal disorders (predominantly CKD) (7% of patients). This is consistent with our data, which identified cystic kidney disease, Down syndrome, and von Willebrand disease as among our most expensive disorders (Table 4). Other disorders identified by both this study and Giampietro et al (2006) as affecting significant numbers of patients included muscular and metabolic disorders (Tables 1 and 5). However, there were also some clear differences, with 12% of patients in the Marshfield population admitted for disorders of the eye, compared to 3% in our population. This can be explained primarily by the exclusion of Duane syndrome from our sample, as other disorders identified by Giampietro et al. (2006) such as macular dystrophy and pigmentary retinopathies were also represented in our data. Connective tissue disorders also accounted for a larger proportion of patients in the Marshfield population (5.7%) than in this study, although Marfan syndrome was relatively common in both populations, accounting for approximately half of the admissions in the ICD-10 code Q87 in our sample (Table 5). In addition, some disorders that were quite common in our study, such as α-1 anti-trypsin deficiency and hereditary ataxia, did not affect many patients in the Marshfield population.

Table 5.

Groups of single gene and chromosomal disorders that involve large numbers of patients, admissions, and high costs in WA, 2000–2006

| Genetic disorder (ICD10-AM code) | Total costa | Number of patients | Number of admissions | Cost per patienta | Cost per admissiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G71 (muscle disorders) | 6,868,699 | 223 | 938 | 30,801 | 7,323 |

| Q87 (multiple system congenital disorders) | 5,165,856 | 148 | 2,612 | 34,904 | 1,978 |

| G60 (hereditary neuropathies) | 3,977,931 | 166 | 938 | 23,963 | 4,241 |

| E74 (disorders of carbohydrate metabolism) | 3,944,993 | 216 | 780 | 18,264 | 5,058 |

| Q85 (phakomatoses) | 3,927,156 | 157 | 616 | 21,001 | 5,353 |

| E80 (disorders of porphyrin and bilirubin metabolism) | 3,350,615 | 172 | 724 | 19,480 | 4,628 |

| E72 (disorders of amino-acid metabolism) | 3,031,085 | 97 | 1,130 | 31,248 | 2,682 |

| E75 (disorders of lipid metabolism) | 2,843,774 | 124 | 765 | 22,934 | 3,717 |

aCost in USD 2007–2008

The differences between our data and those of Giampietro et al. (2006) are probably due to the different nature of the admissions and to differences in coding. The Marshfield study examined only acute health events (3.4% of the total health events in patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders), whereas our data covers all hospital admissions. In addition, Giampietro et al. (2006) used ICD-9 coding as opposed to ICD-10. Although the two ICD coding systems match well for some disorders, for others, the categories are very different. Moreover, we grouped most of our disorders using ICD-10 categories, whereas Giampietro et al. (2006) used slightly different disease-system classifications. For example ICD-10 coding classifies CF as a metabolic disease, whereas Giampietro et al. (2006) classified it as a pulmonary disorder.

The proportion of adult patients, admissions, and hospital costs due to single gene and chromosomal disorders reported here and by Day and Holmes (1973) and Giampietro et al. (2006) are lower than those reported for pediatric populations (Day and Holmes 1973; FitzPatrick et al. 1991; Hall et al. 1978; Kumar et al. 2001; McCandless et al. 2004; Meguid et al. 2003; Scriver et al. 1973; Stanley et al. 2009; Yoon et al. 1997; Dye et al. 2010). This difference appears to be due to increasing numbers of “non-genetic” patients rather than decreasing numbers of patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders. For example, we previously reported that in 2006, 133 of a total of 8,646 patients (1.5%) aged 10–14 years were affected by single gene or chromosomal disorders (Dye et al. 2010), compared to 152 of 26,493 patients (0.6%) aged 30–34 years reported in this study (Online Resources 2 and 3). Thus, although the number of patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders admitted to hospital appears to be remain relatively consistent with increasing age, patients with these disorders make up a smaller proportion of the total patient population in adulthood compared to childhood. A likely explanation for this is the age-related increase in the population prevalence of a range of disorders, such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and arthritis for which people in the general population may require hospitalization.

Although patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders accounted for a similar proportion of total adult patients across most age groups (Fig. 1, Online Resource 4), the proportion of total admissions and costs due to these patients varied. Patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders had the greatest impact on costs in the 20–24 and 40–60 years age brackets, while admissions were highest in the 45–60-year-olds. The higher costs in young adults aged 20–24 may be explained by the high costs of CF in this age bracket (Figs. 1 and 3a), while the peak in admissions and costs in middle adulthood appears to reflect the increasing demand placed on hospital services by CKD and to some extent disorders of iron metabolism (Figs. 1 and 3a). In older adults (>70 years) both CKD and α-1 anti-trypsin deficiency appeared to have a significant impact on hospital admissions and costs (Figs. 1 and 3a).

Consistent with the data reported on hospital admissions of children with single gene and chromosomal disorders (Day and Holmes 1973; FitzPatrick et al. 1991; Hall et al. 1978; Kumar et al. 2001; McCandless et al. 2004; Meguid et al. 2003; Scriver et al. 1973; Stanley et al. 2009; Yoon et al. 1997; Dye et al. 2010), adult patients in our study had more admissions and longer hospital stays than all patients. However, despite the greater LOS of overnight genetic admissions, the cost per admission of patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders was less than for all patients (3,090 versus 3,568 USD), which differs from previously reported pediatric data. This can be explained by the high proportion of same-day admissions of genetic patients (73–78%) compared to all patients (57%) (Tables 1, 2, and 3). This is primarily due to the large number of same-day admissions of patients with CKD to undergo hemodialysis. If CKD patients were excluded from the analysis, the proportion of same-day admissions for genetic disorders decreased to 58%, comparable to all patients, and the cost per genetic admission increased by approximately 1,000 USD. The cost per patient with a single gene or chromosomal disorder was two to three times higher than the cost per any patient across all age groups in 2006 (up to 80 years), largely due to the higher number of admissions. Interestingly, the mean cost of adult and pediatric patients was similar (19,571 USD 2007/8 versus 19,287 USD 2006/7) (Dye et al. 2010), indicating the mean cost of treating a patient with a single gene or chromosomal disorder is relatively consistent across a range of ages and despite the changing profiles of disease in different age groups.

In addition to describing the total impact of genetic disease on the Western Australian hospital system, we were also interested in which specific single gene and chromosomal diseases had the largest impact on hospital resources, what kinds of procedures were recorded, and whether the data obtained from the WA Hospital Morbidity Database corresponded to what is known about the natural history and care requirements of these disorders. For most disorders, the data we obtained matched the disease progression and therapeutic options described in the literature. For example, we found that there was a high demand placed on hospital services by CKD (Q61) in middle to late adulthood, consistent with the disease phenotype of polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1), which accounts for approximately 85% of people with CKD (Barua et al. 2009). The median age of onset of end stage renal failure (ESRF) of patients with PKD1 is estimated at 53 years (Barua et al. 2009; Hateboer et al. 1999), and we found that 80% of the admissions and costs due to CKD were in adults >50 years and that 90% of admissions for CKD patients were for hemodialysis. Our data also indicate that 58 renal transplants were performed on CKD patients between 2000 and 2006, which is 13% of the total number (416) performed in WA (McDonald et al. 2007). This is consistent with previously published data which indicated that CKD accounted for 5% of patients newly diagnosed with primary renal disease in WA (McDonald et al. 2007) and Barua et al. (2009), who reported that CKD accounted for 5% of individuals with ESRF in the USA.

The data we obtained for disorders of iron metabolism (e.g., hemochromatosis) (E831) and CF (E84) also matched the known clinical progression of these disorders. The clinical features of hemochromatosis, a relatively common disorder in Caucasians, are due to the storage of excess iron. Left untreated, the clinical manifestations (e.g., lethargy, hyper-pigmentation, liver, cardiac, and pancreatic abnormalities) become apparent in adults in their 40s and 50s, and the current standard of care is therapeutic venesection (Regan 2009). Our data indicate that admissions and costs associated with hemochromatosis were low in patients aged less than 30 and increased relatively rapidly to peak in adults aged 50–60. Moreover, approximately 50% of patient admissions for hemochromatosis involved therapeutic venesection.

Improved therapies for CF, a disorder which used to be fatal in childhood, have resulted in increased life expectancy such that the median survival of affected individuals in developed nations is now more than 30 years (Hodson 2000). In addition, milder forms of CF are now being diagnosed which have a longer life expectancy (Hodson 2000). Our data indicate that 80% of the hospital costs of CF are due to patients aged less than 39 years, and these costs may reflect the care of severely affected individuals who die in their 30s or 40s. However, some CF-related costs occur through to late adulthood and are probably due to more mildly affected individuals. Approximately 28% of CF admissions involved percutaneous central vein catheterization, consistent with the administration of intravenous antibiotics necessary for many CF patients. However, only 7% of admissions were for physiotherapy, whereas it might have been expected that a higher proportion of CF patients admitted to hospital would receive this treatment.

The cost data and procedural codes associated with thalassemia (D56) and other hereditary hemolytic anemias (D58) were also consistent with the clinical features of the disorder, with the most common procedural code associated with both of these disorders being the transfusion of packed cells (42% and 22% of admissions, respectively). Thalassemia was most costly in younger adults, which may be due to individuals with severe disease (e.g., thalassemia major) dying in early adulthood.

For other disorders, although the general cost and admission data reflected the known progression of the disorder, the procedural codes were less informative. For example, AAT deficiency results in lung damage similar to emphysema with symptoms typically presenting in patients in their 30s or 40s and worsening with age (DeMeo et al. 2009), which is consistent with our admission and cost data. Recommended treatment includes bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids, and in some countries (but not Australia), AAT augmentation therapy (DeMeo et al. 2009). However, our procedural data were relatively non-specific, with 16% of admissions not associated with a procedure, 16% with hemodialysis, and 5% with physiotherapy. vWD (D680) and deficiency in other clotting factors (D682) also had relatively non-specific procedural codes, which may reflect that these disorders are generally well-managed and that admissions of these patients are for a wide variety of reasons both related and unrelated to their genetic condition.

Our data are comparable to that reported by Day and Holmes (1973) and Giampietro et al. (2006), the only two published studies to describe genetic disease and adult hospital admissions. This suggests that the ICD-10 diagnosis codes and methods of data extraction we used were appropriate and captured most patients with single gene or chromosomal disorders. Furthermore, age group analysis of the top 10 most costly genetic disorders largely matched the known clinical progression of each disease, providing further support for the validity of our methodology, despite some limitations as discussed below.

The main advantage of using the WA Data Linkage System in this study is that it allowed us to capture all admissions to every hospital in WA over a 7-year period and reflected the entire population over time, rather than just one or two hospitals. In addition, it was less labor-intensive than direct review. However, there are a number of potential limitations in using a population database to perform this kind of study (Dye et al. 2010; Hall 1997; McCandless et al. 2004; Yoon et al. 1997). A population-based approach using ICD coding may underestimate the impact of single gene and chromosomal disorders. For example, McCandless et al (2004) found that using ICD codes to extract data from hospital databases identified only 75% of the genetic disorders identified by direct review, presumably due to insufficient coding. The hospitals surveyed by direct review are also usually large referral centers, and clinicians in these hospitals are more likely to have experience in diagnosing rare single gene and chromosomal disorders than those practicing in smaller settings. As approximately one quarter of the WA population lives in rural or remote areas, this may increase the chance that some adults with single gene or chromosomal disorders were not identified in our study, particularly if they were relatively mildly affected.

In addition, the use of ICD10 codes may be limiting when the same code includes both childhood and adult-onset disorders. For example, the ICD10 code G71.0 includes Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy, as well as adult-onset muscular disorders such as facioscapulohumeral and limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, among others. These disorders have different ages of onset, clinical presentations, and prognosis, yet they cannot be distinguished using data extracted via ICD10 code. Another issue that became apparent during our analysis was that a large number of admissions for one patient in a disease cohort could significantly influence the grouped data. For example, over half of the admissions recorded for DS patients were for hemodialysis. Further investigation revealed that hemodialysis was not in fact common among DS patients and that the vast majority of these admissions were due to two individuals (out of 286). However, the regular admission pattern associated with ESRF is quite unique, and it is likely that the disorder is one of only a few that may distort procedural codes.

Lastly, we are also aware that we have incomplete ascertainment of some procedures relating to specific genetic conditions. For example, although kidney transplants have been performed in WA since the 1980s, the first lung transplant was performed in 2004, and it was 2006 before the first CF patient received a lung transplant in WA. Between 2000 and 2006, 13 patients with CF travelled interstate to receive a lung transplant. Thus, these data are not included in our dataset and lead to an underestimate of the number of admissions and costs associated with CF.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provides a comprehensive analysis of the impact of adult patients with single gene or chromosomal disorders on hospital services in Western Australia. Consistent with previous reports, these patients represented 0.5% of the patient population and accounted for 1.9% of admissions and 1.7% of hospital costs. Patients with single gene and chromosomal disorders were responsible for a higher proportion of total admissions and costs in adults aged 20–25 and 40–60 years than in other age groups. The most prevalent genetic disorder was CKD, which accounted for 44% of admissions and 16.5% of the total hospital costs associated with genetic diseases. Other disorders with a significant impact on hospital services included AAT deficiency, hemochromatosis, vWD, and CF. These data will be used to inform policy development and health service planning for adults with genetic disorders and will also be useful in guiding professional development programs for primary care providers regarding adult genetic conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 99 kb)

(DOC 322 kb)

(DOC 348 kb)

(DOC 142 kb)

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2008) Population by age and sex, regions of Australia, 2008. Available at http://wwwabsgovau/ausstats/

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2010) Australian demographic statistics, March 2010. Available at http://wwwabsgovau/ausstats/abs@nsf/mf/31010/

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aging (2000–2006) National hospital cost data collection: WA cost weights. Available at http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-casemix-data-collections-about_NHCDC

- Australian Institute of Heatlh and Welfare (2009) Health expenditure Australia 2007–2008. Health and Welfare Expenditure Series No. 37. Available at http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10954

- Baird PA, Anderson TW, Newcombe HB, Lowry RB. Genetic disorders in children and young adults: a population study. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;42(5):677–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua M, Cil O, Paterson AD, Wang K, He N, Dicks E, Parfrey P, Pei Y. Family history of renal disease severity predicts the mutated gene in ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(8):1833–1838. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009020162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova JL, Abel L. Human genetics of infectious diseases: a unified theory. EMBO J. 2007;26(4):915–922. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila S, Hibberd ML. Genome-wide association studies are coming for human infectious diseases. Genome Med. 2009;1(2):19. doi: 10.1186/gm19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day N, Holmes LB. The incidence of genetic disease in a University hospital population. Am J Hum Genet. 1973;25(3):237–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMeo DL, Campbell EJ, Brantly ML, Barker AF, Eden E, McElvaney NG, Rennard SI, Stocks JM, Stoller JK, Strange C, Turino G, Sandhaus RA, Silverman EK. Heritability of lung function in severe alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Hum Hered. 2009;67(1):38–45. doi: 10.1159/000164397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye DE, Brameld KJ, Maxwell S, Goldblatt J, Bower C, Leonard H, Bourke J, Glasson EJ, O'Leary P (2010) The impact of single gene and chromosomal disorders on hospital admissions of children and adolescents: a population based study. Public Health Genomics (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- FitzPatrick DR, Skeoch CH, Tolmie JL. Genetic aspects of admissions to a paediatric intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66(5):639–641. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giampietro PF, Greenlee RT, McPherson E, Benetti LL, Berg RL, Wagner SF. Acute health events in adult patients with genetic disorders: the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area. Genet Med. 2006;8(8):474–490. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000232479.90268.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JG. The impact of birth defects and genetic diseases. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(11):1082–1083. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170480012002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JG, Powers EK, McLlvaine RT, Ean VH. The frequency and financial burden of genetic disease in a paediatric hospital. Am J Med Genet. 1978;1(4):417–436. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320010405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hateboer N, Dijk MA, Bogdanova N, Coto E, Saggar-Malik AK, San Millan JL, Torra R, Breuning M, Ravine D. Comparison of phenotypes of polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. European PKD1-PKD2 Study Group. Lancet. 1999;353(9147):103–107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodson ME. Treatment of cystic fibrosis in the adult. Respiration. 2000;67(6):595–607. doi: 10.1159/000056287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman CD, Bass AJ, Rosman DL, Smith MB, Semmens JB, Glasson EJ, Brook EL, Trutwein B, Rouse IL, Watson CR, Klerk NH, Stanley FJ. A decade of data linkage in Western Australia: strategic design, applications and benefits of the WA data linkage system. Aust Health Rev. 2008;32(4):766–777. doi: 10.1071/AH080766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Radhakrishnan J, Chowdhary MA, Giampietro PF. Prevalence and patterns of presentation of genetic disorders in a paediatric emergency department. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(8):777–783. doi: 10.4065/76.8.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCandless SE, Brunger JW, Cassidy SB. The burden of genetic disease on inpatient care in a children's hospital. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(1):121–127. doi: 10.1086/381053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald S, Chang S, Excell LANZDATA, Report R. Appendix 1 Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. South Australia: Adelaide; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meguid NA, El Bayoumi SM, Hamdi NF, Amen WM, Sayed M, Mahmoud A. Prevalence of genetic disorders in paediatric emergency department Al Galaa teaching hospital. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences. 2003;6(23):1961–1965. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2003.1961.1965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regan EN. Hemochromatosis: pumping too much iron. Nurse Pract. 2009;34(6):25–29. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000352285.81981.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimoin DL, Conner MJ. Nature and frequency of genetic disease. In: Rimoin DL, Conner JM, Pyeritz RE, Korf BR, editors. Emery and Rimoin's principles and practice of medical genetics vol 1. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. pp. 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Scriver CR, Neal JL, Saginur R, Clow A. The frequency of genetic disease and congenital malformation among patients in a paediatric hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 1973;108(9):1111–1115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley C, Bankier A, Rose C, Robinson K, Halliday J. The genetic basis for admissions to a paediatric hospital. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2009;12(2):233. [Google Scholar]

- Trimble BK, Doughty JH. The amount of hereditary disease in human populations. Ann Hum Genet. 1974;38(2):199–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1974.tb01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon PW, Olney RS, Khoury MJ, Sappenfield WM, Chavez GF, Taylor D. Contribution of birth defects and genetic diseases to paediatric hospitalizations. A population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(11):1096–1103. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170480026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 99 kb)

(DOC 322 kb)

(DOC 348 kb)

(DOC 142 kb)