Abstract

Epigenetic reprogramming, characterized by loss of cytosine methylation and histone modifications, occurs during mammalian development in primordial germ cells (PGCs), yet the targets and kinetics of this process are poorly characterized. Here we provide a map of cytosine methylation on a large portion of the genome in developing male and female PGCs isolated from mouse embryos. We show that DNA methylation erasure is global and affects genes of various biological functions. We also reveal complex kinetics of demethylation that are initiated at most genes in early PGC precursors around embryonic day 8.0–9.0. In addition, besides intracisternal A-particles (IAPs), we identify rare LTR-ERV1 retroelements and single-copy sequences that resist global methylation erasure in PGCs as well as in preimplantation embryos. Our data provide important insights into the targets and dynamics of DNA methylation reprogramming in mammalian germ cells.

DNA methylation occurs on cytosines and plays pivotal roles during mammalian development. It is found at promoters of key developmental and germline genes and is necessary for genomic imprinting and X-inactivation, and the absence of DNA methyltransferases leads to early embryonic lethality in mice (Meissner 2010). DNA methylation is extensively reprogrammed on a genome-wide level during preimplantation development as well as in the developing germ cell lineage (Sasaki and Matsui 2008; Feng et al. 2010). Germ cells arise from the pluripotent epiblast and initially form a cluster of around 40 primordial germ cells (PGCs) posterior to the primitive streak in the extra-embryonic mesoderm at embryonic day 7.25 (E7.25). The earliest known marker is Prdm1 (also known as Blimp1), which is expressed specifically in the precursors of PGCs as early as E6.25 (Ohinata et al. 2005). Another marker of the germ cell lineage is the pluripotency factor Dppa3 (also known as Stella), whose expression is restricted to nascent PGCs in E7.5 embryos (Sato et al. 2002). After fate determination, PGCs proliferate and migrate to colonize the genital ridges, where they continue to proliferate until E13.5 and enter meiotic prophase in females and mitotic arrest in males.

During migration, PGCs undergo global epigenetic reprogramming with exchange of histone variants, loss of histone modifications, and erasure of DNA methylation (Hajkova et al. 2008), which is thought to be completed around E13.5 in both male and female embryos. PGCs have been reported to erase DNA methylation imprints (Hajkova et al. 2002; Yamazaki et al. 2005), as well as methylation of repetitive sequences (Lane et al. 2003; Lees-Murdock et al. 2003). Very sparse evidence also indicates that demethylation affects nonimprinted genes such as post-migratory germline genes (Maatouk et al. 2006), which is thought to promote the activation of the germline expression program. Recently, low coverage bisulfite sequencing was used to show that E13.5 PGCs show reduced levels of cytosine methylation in all genome compartments (Popp et al. 2010). Yet it remains to determine precisely what sequences are targets of demethylation in developing PGCs, which requires a profiling of DNA methylation at a single-loci resolution. It is also important to determine if certain sequences resist methylation erasure in PGCs. To date, the only known exceptions are intracisternal A-particles (IAPs), a family of rodent retrotransposons that show partial demethylation in PGCs (Hajkova et al. 2002; Lane et al. 2003; Popp et al. 2010).

The timing and mechanisms of DNA demethylation in PGCs are not fully elucidated (Guibert et al. 2009; Wu and Zhang 2010). Studies on imprinting control regions (ICRs) revealed that most of them undergo a rapid erasure of DNA methylation between E10.5 and E12.5, when PGCs have colonized the genital ridges (Hajkova et al. 2002; Sato et al. 2003; Li et al. 2004). However, immunohistochemistry suggested that PGCs lose DNA methylation when they start migrating from E8.0 onward (Seki et al. 2005), which might indicate that not all genomic sequences follow the same kinetics of demethylation. The observation of rapid demethylation at certain ICRs led to the proposal of the existence of active mechanisms of demethylation (Hajkova et al. 2002). This is supported by recent findings implicating DNA deaminases such as activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AICDA, also known as AID) (Morgan et al. 2004; Popp et al. 2010), as well as the base excision repair pathway (Hajkova et al. 2010). It has also been proposed that the modification of 5-methylcytosine by enzymes of the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family is involved in the reaction of demethylation, although this is apparently not supported by the recent observation that Tet1 knockout mice are fertile and have normal gametogenesis (Dawlaty et al. 2011).

Here, we use methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) to map DNA methylation on a large fraction of the mouse genome, including promoters, in male and female PGCs. We observe that the development of PGCs is accompanied by a global demethylation of all genes, not only those involved in germ cell development. We assess the kinetics of DNA demethylation and identify rare genomic regions that partially resist methylation erasure during PGCs development.

Results

Genome-wide profiles of DNA methylation in E7.5 epiblasts and E13.5 PGCs

To have a comprehensive view of DNA methylation reprogramming in PGCs, we performed MeDIP on genomic DNA from E7.5 epiblasts and PGCs isolated for male and female E13.5 embryos (Fig. 1A). PGCs were isolated by FACS sorting from embryos carrying a Pou5f1(Oct4)-driven GFP (Supplemental Fig. 1A) and showed high purity as measured by phosphatase alkaline staining (Supplemental Fig. 1B,C). Because PGCs arise from the epiblast around E7.5 with similar DNA methylation levels than surrounding cells (Seki et al. 2005), we considered E7.5 epiblast as the start point for methylation reprogramming, whereas E13.5 is considered the endpoint of methylation erasure in PGCs. To minimize the impact of nonspecific binding of antibodies in demethylated genomes, we performed biological replicates of MeDIP with two different 5-methylcytosine antibodies (see Methods). To validate the procedure, we performed qPCR that shows that IAPs are enriched in the MeDIP fraction compared with unmethylated controls in E13.5 PGCs (Supplemental Fig. 2). MeDIP samples were then hybridized to Nimblegen HD2 arrays covering −8 kb to +3 kb from all transcription start sites (TSSs), which represents >10% coverage of the mouse genome.

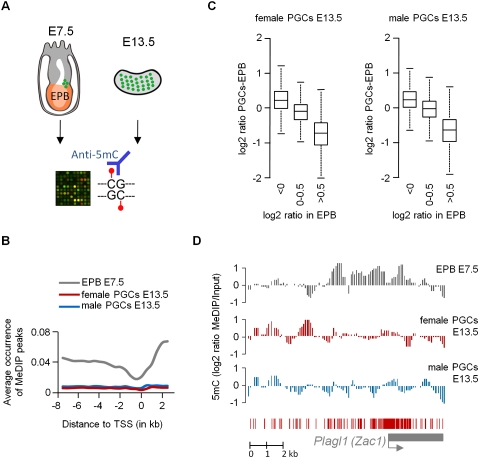

Figure 1.

Global absence of cytosine methylation in E13.5 PGCs. (A) We hybridized MeDIP samples from E7.5 epiblasts (EPB) and PGCs (green dots) from E13.5 gonads on NimbleGen HD2 arrays covering 11 kb of all gene promoters in the mouse genome. (B) The graph shows the fraction of tiles with a methylation peak as a function of the distance to the transcription start site (TSS). This shows that the enrichment of cytosine methylation in intergenic regions and gene bodies, typical of somatic cells, is erased in E13.5 PGCs. (C) Differences in oligo log2 ratios between E7.5 epiblasts and E13.5 PGCs. The boxplot shows that regions enriched in epiblasts largely lose the methylation signal in PGCs. (D) Erasure of methylation imprints in male and female E13.5 PGCs illustrated at the Plagl1 locus. (Graphs) Smoothed MeDIP log2 ratios of individual oligonucleotides. Here and in other figures, the gene is shown below the graphs as a gray box, the TSS is shown as a gray arrow, and red bars represent the position of the CpGs.

In case of a globally demethylated genome, we expect the median-normalized MeDIP log2 ratio to reflect background signal and be randomly distributed around zero. Indeed, we observe that male and female E13.5 PGCs show random MeDIP signals that are independent of the CpG content (Supplemental Fig. 3A). In comparison, E7.5 epiblasts show a strong dependence between log2 ratios and CpG content, with log2 ratios being low for CpG-rich sequences and peaking at sequences with intermediate CpG content (Supplemental Fig. 3A). All chromosomes, including the Y in male PGCs, show a similar distribution of MeDIP signals in E13.5 PGCs (Supplemental Fig. 3B). Accordingly, the typical somatic profile of DNA methylation observed in E7.5 epiblasts, with increased methylation in intergenic regions and gene bodies compared with gene promoters (Lister et al. 2009; Borgel et al. 2010), is erased in male and female E13.5 PGCs (Fig. 1B). We performed validation by COBRA on several regions and confirmed that moderate log2 ratio up to 0.8 in E13.5 PGCs are associated with fully hypomethylated sequences and therefore represent background signal (Supplemental Fig. 4). Therefore, while in somatic cells such as E7.5 epiblasts, a log2 ratio > 0 indicates a partial or full methylation, this cutoff needs to be increased to at least 0.8 in PGCs. The global loss of DNA methylation is also illustrated by the fact that most oligos with high methylation in E7.5 epiblasts lose MeDIP signal in male and female E13.5 PGCs (Fig. 1C). In particular, many ICRs such as Plagl1 (also known as Zac1), Peg3, Peg10, or KvDMR1, which are known targets of DNA demethylation in PGCs, lose MeDIP signals in E13.5 PGCs (Fig. 1D; Supplemental Fig. 5), which further validates our results. Altogether, these results indicate a global loss of cytosine methylation in mouse PGCs, which is consistent with recent bisulfite sequencing data (Popp et al. 2010).

Of note, we compared in detail the DNA methylation profiles in male and female E13.5 PGCs and observed that methylation profiles are very similar in both sexes. We detected only very mild differences in MeDIP profiles that could, so far, not be validated by bisulfite sequencing (data not shown). Therefore our MeDIP profiles did not allow us to identify sex-specific differences in DNA methylation in E13.5 PGCs, and we conclude that methylation reprogramming occurs to a similar extent in the male and female germline.

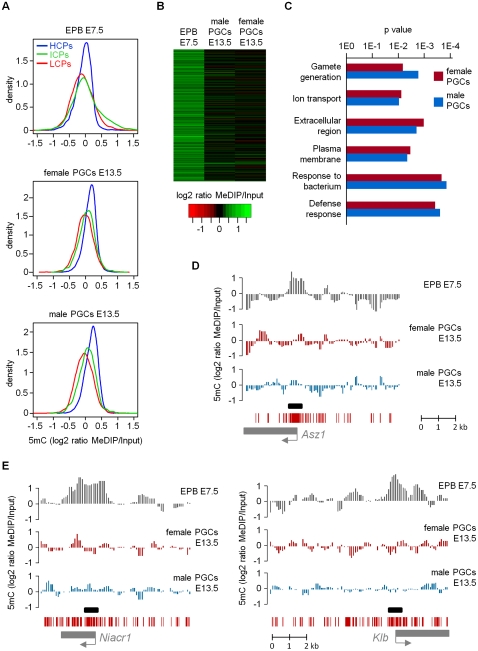

Targets of promoter demethylation in E13.5 PGCs

Next we identified which genes are subjected to promoter demethylation in PGCs. When looking simultaneously at all gene promoters, classified as either low (LCPs), intermediate (ICPs), or high CpG promoters (HCPs), we observe that the small fraction of promoters hypermethylated in E7.5 epiblasts is not detectable in male or female E13.5 PGCs (Fig. 2A). Of the 511 gene promoters that we identified that hypermethylated in E7.5 epiblasts (Supplemental Table 1), which largely overlap with gene promoters methylated in E6.5 epiblasts and total E9.5 embryos (Supplemental Fig. 6A), the vast majority does not maintain DNA methylation in male and female E13.5 PGCs (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. 6B). This indicates that virtually all gene promoters methylated in epiblasts undergo erasure of DNA methylation in developing PGCs. To characterize the function of these demethylated genes, we performed an ontology analysis on the list of genes demethylated in E13.5 PGCs compared with E7.5 epiblasts (Fig. 2C). This reveals that many targets of promoter demethylation in PGCs are germline-specific genes involved in meiosis or generation of gametes. Selected examples include Asz1, Ccin, Dnajb7, Mei1, Dpep3, as well as Dazl and Sycp3, which have been described previously (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. 7A; Maatouk et al. 2006). This supports the hypothesis that promoter demethylation during PGC development might participate in promoting the activation of the germline expression program (Feng et al. 2010). In addition, many other genes that undergo promoter demethylation in PGCs are not expressed in germ cells but are involved in various biological processes in somatic cells (Fig. 2C). In particular, DNA methylation in epiblasts is present at several promoters of genes involved in hematopoietic differentiation and defense response (Cytip, Tlr6, Tlr1, Pou2af1, Wfdc15b) (Borgel et al. 2010), signaling at the membrane (Niacr1, Gpr151, Klb), as well as neuronal functions (Cplx4) or placental development (Rhox cluster) (Oda et al. 2006), and all these undergo demethylation in E13.5 PGCs (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Fig. 7B). We conclude that PGCs undergo global erasure of promoter DNA methylation at all genes, not only at the ones programmed to be expressed in germ cells.

Figure 2.

Erasure of promoter DNA methylation at all genes in E13.5 PGCs. (A) The density plots show the distribution of all gene promoters (classified as HCPs, ICPs, and LCPs) according to their average MeDIP ratios (calculated in regions covering −700 to +200 bp relative to the transcription start site). The small fraction of enriched promoters in E7.5 epiblasts (EPB) is absent in male and female E13.5 PGCs. (B) The heatmap shows that genes with a methylated promoter in E7.5 epiblasts lose the methylation signal in male and female E13.5 PGCs. (C) Ontology terms enriched in genes that lose promoter cytosine methylation in male and female E13.5 PGCs. (D) Demethylation of the promoter of the germline-specific gene Asz1 in E13.5 PGCs. (Graphs) Smoothed MeDIP over input ratios of individual oligonucleotides. (Black box) Position of the PCR fragment used for COBRA and bisulfite sequencing validations. (E) Demethylation of the promoters of somatic genes Niacr1 and Klb in E13.5 PGCs.

Kinetics of promoter demethylation in developing PGCs

The timing of demethylation at single-copy regions in PGCs has so far mostly been addressed on ICRs. These studies revealed a rapid demethylation event around E11.5 (Hajkova et al. 2002; Sato et al. 2003; Li et al. 2004), yet it is unclear if all genomic regions follow the same kinetics. Having identified targets of promoter demethylation, we next determined the timing of demethylation at these genes in PGCs. For this, we isolated PGCs at E9.5, E11.5, and E12.5 by FACS sorting from Oct4-GFP embryos (Supplemental Fig. 1A), which showed good purity as measured by phosphatase alkaline staining on sorted E9.5 PGCs (Supplemental Fig. 1C). First we performed COBRA on 10 gene promoters that include germline genes (Asz1, Dpep3, Csnka2ip) and somatic genes (Tlr6, Tlr1, Pou2af1, Rhox6/9, Niacr1, Klb, Gpr151). While all tested promoters are hypermethylated in E7.5 epiblasts, our results indicate that demethylation in PGCs is already initiated in E9.5 embryos (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. 8A,B). Thereafter, complete erasure of methylation occurs rapidly between E11.5 and E12.5 at most targets (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. 8A,B). To get more insights, we performed bisulfite sequencing on several gene promoters in developing PGCs. For these experiments, we also included PGCs isolated from E8.5 embryos that can be obtained in very small quantities only. All tested promoters show substantial methylation in E8.5 PGCs, indicating that early PGC precursors did acquire promoter DNA methylation similar to epiblast cells (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. 8C). Subsequently, the bisulfite sequencing results confirm that DNA demethylation at all tested genes is initiated in E9.5 PGCs and is then rapidly completed after E11.5 (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. 8C). These kinetics of demethylation initiated in early PGC precursors contrast with the demethylation at ICRs that seems to occur mostly during later stages between E10.5 and E12.5 (Hajkova et al. 2002; Sato et al. 2003; Li et al. 2004), which we could also recapitulate in our samples for the Peg3 and Igf2r imprinted loci (Supplemental Fig. 9). We therefore conclude that imprinted and nonimprinted sequences do not follow the same kinetics of demethylation and that most nonimprinted genes initiate progressive erasure of DNA methylation in early PGC precursors around E8.0–E9.0 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of promoter DNA demethylation in developing PGCs. (A) DNA methylation of several gene promoters was analyzed by COBRA in E7.5 epiblasts (EPB) and PGCs isolated from E9.5 to E13.5 embryos. Methylation in E13.5 whole embryos (WEs) is shown as a control. Here and in other figures, the number of TaqαI sites in the amplified fragment is indicated in parenthesis, and asterisks mark restriction fragments representing end products of the digestion. (B) Bisulfite sequencing results in PGCs isolated from E8.5 to E13.5 embryos. Tested promoter sequences show high levels of cytosine methylation in E8.5 PGCs and progressive demethylation initiated in early PGC precursors. (Squares) CpG dinucleotides, either unmethylated (gray) or methylated (black). (C) Summary of the bisulfite sequencing methylation data from B and Supplemental Figure 8C. (Graph) Average percentage of cytosine methylation within the amplified fragments for every tested promoter.

Interestingly, in contrast to other genes, the promoter of the PGC marker Dppa3, which is subject to de novo methylation in the whole embryo between E7.5 and E9.5 (Borgel et al. 2010), is maintained in a hypomethylated state at all stages in PGCs (Supplemental Fig. 10). This shows that early PGCs are epigenetically distinct from somatic cells at certain loci and suggests that differential DNA methylation at the Dppa3 locus and possibly other germ cell markers participates in the early specification of PGCs.

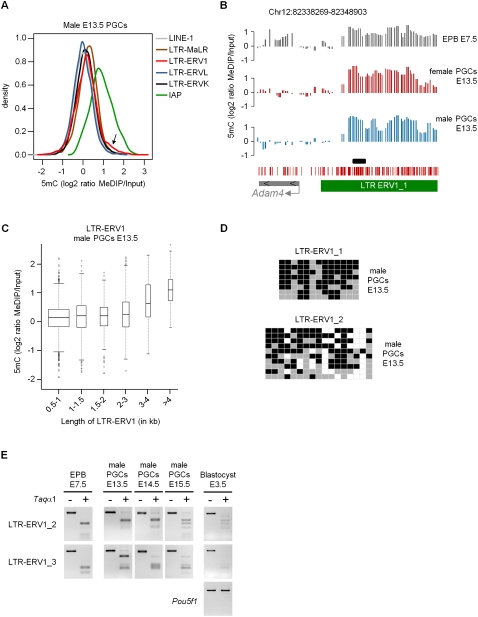

Methylation at LTR-ERV1 retroelements in PGCs

Previous studies have shown that a class of mobile elements, IAPs, partially resists demethylation in PGCs and preimplantation embryos (Hajkova et al. 2002; Lane et al. 2003; Popp et al. 2010). To assess the methylation of repetitive DNA, we averaged MeDIP ratios of oligos in mobile elements (these are unique oligos that could be designed in certain portions of repetitive DNA) and confirmed that IAPs show on average a much higher MeDIP enrichment in E13.5 PGCs than LINE-1 elements and other retroelements of the LTR-MaLR, LTR-ERV1, LTR-ERVL, and LTR-ERVK families (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Fig. 11A). However, although most LTR-ERV1 sequences do not appear methylated in E13.5 PGCs, we did identify a subset of LTR-ERV1 elements tiled on the microarray with high methylation in both male and female E13.5 PGCs (Fig. 4B; Supplemental Fig. 12A). Interestingly, these methylated LTR-ERV1 elements are longer and with a higher CpG richness than the bulk of LTR-ERV1 sequences (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. 11B), which suggests that methylation is preferentially found at LTR-ERV1 elements showing signs of recent insertion. We performed validations by bisulfite sequencing and COBRA that confirm the presence of high levels of cytosine methylation at several of these LTR-ERV1 elements in E13.5 PGCs (Fig. 4D,E). Cytosine methylation is also present in PGCs isolated from E14.5 and E15.5 embryos, which indicates that it is not the result of a delay in methylation erasure (Fig. 4E). Notably, the same LTR-ERV1 sequences are also found methylated in preimplantation blastocysts and therefore possibly are also resistant to post-fertilization methylation erasure (Fig. 4E). We conclude that, in addition to IAPs, a subset of LTR-ERV1 elements resists the successive waves of epigenetic reprogramming and is incompletely demethylated in preimplantation embryos and PGCs.

Figure 4.

Cytosine methylation of repetitive elements in E13.5 PGCs. (A) The density plot represents the distribution of MeDIP log2 ratios of oligonucleotides located in various classes of repetitive elements in E13.5 male PGCs. (Arrow) Small proportion of probes in LTR-ERV1 elements with high MeDIP signals. The distribution is identical in female PGCs (Supplemental Fig. 11A). (B) Example of tiled LTR-ERV1 element on chromosome 12 that retains high levels of cytosine methylation in male and female E13.5 PGCs. The graphs show smoothed MeDIP over input ratios of individual oligonucleotides. (Black box) Position of the PCR fragment used for COBRA and bisulfite sequencing validations. The genomic position is indicated above the graphs. (C) The box plot shows the distribution of MeDIP log2 ratios in LTR-ERV1 elements in E13.5 male PGCs as a function of the size of LTR-ERV1 elements. Here and in subsequent box plots, the width of the box is proportional to the square root of the number of data points. The distribution is identical in female PGCs (Supplemental Fig. 11B). (D) Bisulfite sequencing confirms the presence of cytosine methylation in LTR-ERV1 elements in male E13.5 PGCs. In our conditions, the LTR-ERV1_1 primers amplify one single element, whereas the LTR-ERV1_2 primers amplify several elements with sequence polymorphisms. Squares represent CpG dinucleotides as unmethylated (gray), methylated (black), or absent (white). (E) COBRA shows that LTR-ERV1 elements are also methylated in PGCs isolated from male E14.5 and E15.5 embryos, as well as in preimplantation E3.5 blastocysts. Lack of methylation in the Pou5f1 (Oct4) promoter is used as a control for the purity of blastocysts. Note that the LTR-ERV1_3 primers, like the LTR-ERV1_2 primers, amplify several elements with minor sequence differences.

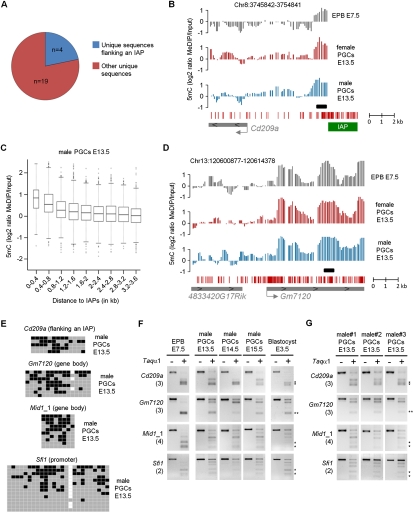

Identification of single-copy sequences with remaining cytosine methylation in PGCs

Next we searched for single-copy regions that retain cytosine methylation in E13.5 PGCs. Because moderate MeDIP enrichments in E13.5 PGCs represent a random background signal, we applied a stringent cut-off to identify sequences with a MeDIP log2 ratio above 0.9, which according to our COBRA validations represents the threshold for detectable levels of cytosine methylation (Supplemental Fig. 4). To minimize false positives, we only considered regions that are highly enriched with both antibodies in male and female E13.5 PGCs, which identified a set of 23 loci. Detailed genomic information for these 23 loci can be found in Supplemental Table 2. According to these criteria, the proportion of single-copy genomic sequences that retain cytosine methylation in E13.5 PGCs is therefore minimal. These sequences can be divided into two groups (Fig. 5A). The first group (four out of 23) corresponds to single-copy sequences directly flanking IAP elements (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. 12B). This shows that residual methylation of IAPs in E13.5 PGCs frequently spreads into neighboring single-copy sequences, which is confirmed by a global analysis showing that oligos close to IAPs show on average increased MeDIP enrichments (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. 11C). This spreading of cytosine methylation into neighboring sequences is a hallmark of IAPs because we identified no cases of cytosine methylation in the vicinity of LTR-ERV1 elements. The second group (19 out of 23) corresponds to single-copy loci that are not in the vicinity of repetitive elements, which are of various sizes and found in intergenic regions, gene bodies, or promoters (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Fig. 13A). We validated that these single-copy regions do not show any sign of repetitiveness by verifying that their DNA sequence and microarray oligos have single BLAT hits in the genome (Supplemental Fig. 13B). We performed validations by bisulfite sequencing in several of these targets and confirmed the presence of remaining cytosine methylation at one sequence flanking an IAP element (Cd209a locus), as well as at the Gm7120, Mid1, Sfi1, and Srrm2 loci (Fig. 5E; Supplemental Fig. 13C). This persistent methylation does not reflect a delay in methylation erasure as cytosine methylation is also detected in PGCs isolated from E14.5 and E15.5 embryos (Fig. 5F). Similar to IAP and LTR-ERV1 elements, these single-copy sequences also maintain high levels of cytosine methylation in blastocysts (Fig. 5F), indicating that they resist both waves of demethylation in PGCs and preimplantation development. Of note, four of these single-copy loci (Cd209a, Gm7120, Mid1, and Sfi1) were also covered in a recent RRBS study and found to be methylated in gametes and blastocysts, as well as 5-dpp (days post-partum) nongrowing oocytes and oocytes lacking DNMT3A or DNMT3L (Supplemental Table 2), which further supports incomplete demethylation during preimplantation development and PGC reprogramming (Smallwood et al. 2011). Finally, we considered the possibility that mosaic patterns of DNA methylation in E13.5 PGCs reflect variable methylation between individuals. To address this, we show that E13.5 PGCs isolated from three individual male embryos show comparable levels of methylation (Fig. 5G), indicating that the maintenance of cytosine methylation is not stochastic between individuals. Altogether this reveals the existence of rare single-copy sequences that resist global methylation reprogramming and consistently maintain high levels of cytosine methylation in preimplantation embryos and PGCs during mouse development.

Figure 5.

Identification of single-copy regions that resist demethylation in PGCs. (A) Proportions of identified single-copy loci that flank repetitive elements (blue) or are not on the vicinity of repetitive elements (red). (B) Example of MeDIP profiles at a single-copy sequence directly flanking an IAP element. The graphs show smoothed MeDIP over input ratios of individual oligonucleotides. The black box marks the position of the PCR fragment used for COBRA and bisulfite sequencing validations. The genomic position is indicated above the graphs. (C) The box plot represents the distribution of log2 ratios in male E13.5 PGCs as a function of the distance to the border of IAPs, which reveals that single-copy regions in the vicinity of IAPs show increased MeDIP signal. The distribution is identical in female PGCs (Supplemental Fig. 11C). (D) Example of MeDIP profiles at a locus not flanked by repetitive elements that retains cytosine methylation in E13.5 PGCs. (E) Bisulfite sequencing validates the presence of cytosine methylation at various single-copy regions in male E13.5 PGCs, one of them flanking an IAP element (Cd209a). Squares represent CpG dinucleotides as unmethylated (gray), methylated (black), or absent (white). The polymorphic CpG residues at the Gm7120 and Sfi1 loci might represent strain differences. (F) COBRA shows that methylation of single-copy loci is also present in PGCs isolated from the E14.5 and E15.5 male embryo, as well as in preimplantation E3.5 blastocysts. (G) COBRA shows that methylation of single-copy loci is found in E13.5 PGCs isolated from three male individuals, indicating that it is not a stochastic event.

Discussion

To summarize, we provide a genome-scale view of DNA methylation in developing mouse PGCs. Our results indicate that PGCs at the E13.5 embryonic stage acquire a unique epigenetic state characterized by absence of cytosine methylation at the majority of the genome, which confirms recent observations by low-coverage bisulfite sequencing (Popp et al. 2010). This epigenetic state could result from an absence of de novo methylation in early PGC precursors or an erasure of cytosine methylation during the development of PGCs. Our results clearly favor the second hypothesis as all tested sequences show high methylation in PGC precursors isolated from E8.5 embryos, which is in agreement with immunofluorescence studies showing similar levels of cytosine methylation in PGC precursors and neighboring somatic cells in E8.0 embryos (Seki et al. 2005). Exceptions are germ cell markers such as Dppa3 that maintain a hypomethylated state throughout PGC development (Supplemental Fig. 10). Interestingly, we have not identified major sex-specific differences in DNA methylation in E13.5 PGCs, which might be explained by the fact that sex determination occurs around E11.5–E12.5, a time where a large part of the demethylation has already been initiated. Our data also show that the methylation erasure in PGCs is more complete than in preimplantation embryos, where a high number of CpG islands, gene promoters, and possibly other sequences resists global demethylation after fertilization, in particular on the maternal genome (Borgel et al. 2010; Smallwood et al. 2011). It therefore appears that PGCs are the main site for DNA methylation reprogramming during the mammalian life cycle.

The resultant questions concern the timing and mechanisms of methylation removal in PGCs. Our data indicate that most genomic loci initiate progressive erasure of methylation in early PGC precursors around E8.0–E9.0, and that complete demethylation then occurs around E11.5. This early onset coincides with a loss of DNA methylation signal observed by immunofluorescence in PGCs around E8.0 (Seki et al. 2005). The full demethylation during later stages around E11.5 coincides with the activation of the base excision repair pathway (Hajkova et al. 2010) and the demethylation of ICRs (Hajkova et al. 2002; Li et al. 2004), although other studies reported that certain ICRs show some signs of demethylation already in PGCs from E10.5 embryos (Lee et al. 2002; Sato et al. 2003; Yamazaki et al. 2003, 2005). It therefore appears that methylation erasure in PGCs occurs in a stepwise manner, with a first wave initiated around E8.0–E9.0 that affects the bulk of the genome and a second wave around E11.5 that also affects ICRs. Although recent work clearly points toward the involvement of active mechanisms of demethylation that occurs independently of DNA replication (Hajkova et al. 2008, 2010), the progressive loss of methylation initiated around E8.0–E9.0 does not formally rule out the contribution of replication-dependent passive demethylation. It can therefore not be excluded that a combination of passive and active mechanisms, occurring maybe at different times, contributes to the erasure of methylation patterns in PGCs. The identification of targets of DNA demethylation in our study will certainly provide valuable information to test models of demethylation.

Besides erasure of methylation imprints, the physiological significance of methylation removal in PGCs remains elusive (Feng et al. 2010). Here we show that demethylation affects a large number of germline genes, indicating that it could serve to promote the activation of the germ cell expression program. Yet this is certainly only part of the answer as we show that demethylation also affects many other genes with somatic functions. One can speculate that this global erasure could serve to restore a methylation ground state compatible with pluripotency or to prevent the accumulation of harmful epialleles. Notable exceptions are IAPs, a recent family of rodent retrotransposons that retains cytosine methylation in PGCs (Hajkova et al. 2002; Lane et al. 2003; Popp et al. 2010). Here we show that other sequences maintain cytosine methylation in PGCs, an observation that is compatible with the presence of DNMT1 throughout most of the PGC migration (Hajkova et al. 2002; Seki et al. 2005; Yabuta et al. 2006). First, we show that certain LTR-ERV1 elements, in particular those showing signs of recent insertion in the genome, are also resistant to demethylation in PGCs. This suggests the existence of a mechanism to maintain cytosine methylation preferentially at young and potentially active mobile elements, which might be necessary to prevent their transient deleterious activation in the germline. We also identify for the first time single-copy sequences that are resistant to demethylation in PGCs. These sequences are very rare in our analysis, although we might have underestimated their number because we used stringent cutoffs. In the future, more sensitive methods such as genome-wide bisulfite sequencing should be used to precisely quantify the proportion of the genome that resists demethylation. Interestingly, we show that many of the same sequences are also resistant to DNA methylation erasure in preimplantation embryos, suggesting that these genomic regions consistently maintain high levels of DNA methylation at any embryonic stage during the mouse life cycle. The mechanisms that allow resistance to global demethylation are unclear, but one possibility is that it involves DNA binding factors that specifically protect some sequences against demethylation, as shown recently with the zinc finger protein ZFP57 that protects ICRs from demethylation in preimplantation embryos (Li et al. 2008; Quenneville et al. 2011). These data therefore reveal that there is a potential, although very limited, for transgenerational inheritance of DNA methylation states over multiple generations in mice (Jirtle and Skinner 2007). Some of these sequences directly flank IAP elements, indicating that persistent methylation in IAPs can spread into neighboring single-copy sequences. This is interesting considering the fact that some of the rare examples of inherited epimutations in mammals involve IAP elements that alter the expression of neighboring genes (Whitelaw and Whitelaw 2008). We also identify a number of methylated sequences that are not in the vicinity of repetitive elements. So far we could not detect common characteristics associated with these regions (in terms of CpG content, size, or gene function), and therefore the function of the persistent cytosine methylation during development remains elusive. We do nonetheless note that certain of these loci with persistent methylation in PGCs and preimplantation blastocysts are located in subtelomeric regions, which could indicate that cytosine methylation is maintained in subtelomeric regions to ensure chromosome stability (Gonzalo et al. 2006).

Methods

Isolation of embryos and PGCs

All embryos were obtained from crosses between (C57BL/6JxCBA/J)F1 females and Oct4-GFP males (Yoshimizu et al. 1999), except when indicated. The morning of vaginal plug detection was designated E0.5. Epiblasts were dissected from E7.5 embryos in M2 medium (Sigma-Aldrich). For PGCs, embryonic parts from the hindgut endoderm (E8.5, E9.5), genital ridges (E11.5), and gonads (E12.5, E13.5, E14.5, E15.5) were dissected in PBS and incubated for 5 min at 37°C in 0.25% trypsin and 1 mM EDTA to obtain a single-cell suspension. Starting from E12.5, the embryos were sexed by the morphological appearance of the gonads. PGCs were then sorted by virtue of the GFP expression by flow cytometry (FACSAria, BD Biosciences). At all embryonic stages, PGCs were pooled from several embryos. At the E13.5 stage, when indicated, we also isolated PGCs from individual males. Somatic controls were performed on DNA from total E13.5 embryos. The purity of PGCs was verified on an aliquot of cells by alkaline phosphatase staining (Alkaline Phosphatase Detection Kit, Millipore). Blastocysts were collected from C57BL/6 mice at E3.5 by flushing the uteri with M2 medium. Genomic DNA was extracted by proteinase K digestion, phenol/chloroform extraction, and precipitation with ethanol.

DNA methylation analysis

MeDIP was performed on 150 ng DNA as described (Borgel et al. 2010) using 1/10 μL anti-5mC antibody for epiblasts and 1/30 μL for PGCs. For epiblasts, we performed one MeDIP with a monoclonal antibody from AbD Serotec (clone 33D3) and one MeDIP with a monoclonal antibody from Abcam (clone 3A3), which showed good reproducibility. For PGCs, we performed two replicates with the AbD Serotec antibody and one replicate with the Abcam antibody. We also performed mock pull-down controls without anti-5mC antibody that did not recover any DNA. Subsequently, 5 ng input DNA and the entire MeDIP product was amplified with the Whole Genome Amplification Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer's instructions. MeDIP samples were hybridized together with input samples to Roche Nimblegen HD2 2.1M Deluxe Promoter arrays covering −8200 bp to +3000 bp from 23,517 potential TSSs. Sample labeling and microarray hybridization were done according to the standard procedure by Roche Nimblegen. Conversion of DNA with sodium bisulfite was performed with the EpiTect kit (Qiagen). Subsequent analysis by COBRA and sequencing was performed as described (Borgel et al. 2010). Bisulfite PCR reactions in early PGC precursors were performed on the equivalent of at least 50 cells. Clone sequences were processed and aligned with the BISMA software (http://biochem.jacobs-university.de/BDPC/BISMA; Rohde et al. 2010). Primer sequences are given in Supplemental Table 3.

Data processing

Microarray data processing and representation were performed with the R software (http://www.r-project.org) as previously described (Borgel et al. 2010). Briefly, we calculated MeDIP/input log2 ratios from raw signal intensities provided by Nimblegen and performed an intra-array loess normalization and an inter-array normalization to have equal normal distributions between arrays using the limma package (Smyth and Speed 2003). We then averaged normalized log2 ratios from biological replicates. For data representation, we smoothed average log2 ratios over 400 bp and created GFF files to be visualized using the SignalMap software (Roche Nimblegen). Promoter CpG classes and validated promoters were determined as previously described (Borgel et al. 2010). To represent methylation along tiled regions (Fig. 1B), we calculated the fraction of tiles with a MeDIP peak (defined as at least six consecutive oligos with a smoothed log2 ratio > 0.6) as a function of the distance to the TSS. Genes with a methylated promoter in E7.5 epiblasts were defined as genes with a hypermethylated region (defined as at least six consecutive oligos with a smoothed log2 ratio > 0.5) overlapping or <300 bp upstream of the TSS. The ontology analysis was performed by comparing all autosomal demethylated genes (defined as methylated gene promoters in E7.5 epiblasts with an average log2 ratio in the MeDIP peak < 0.6 in PGCs) with all validated genes present on the array using the DAVID functional annotation tool (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov; Huang da et al. 2009). To find regions with residual cytosine methylation in E13.5 PGCs, we averaged normalized log2 ratios from all male and female replicates and searched for regions with at least six consecutive oligos with a smoothed log2 ratio > 0.9. These regions were then filtered to have an average log2 ratio > 0.5 with both 5mC antibodies in both male and female data sets. Methylated regions that appeared very close from each other in the same loci were merged into one single methylation peak. Annotations for repetitive elements were based on the UCSC genome annotations (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu), and we only considered repetitive elements with a size >500 bp. All genome annotations refer to the UCSC mm8 genome.

Data access

The raw methylation data sets have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession no. GSE31572.

Acknowledgments

We thank Philippe Arnaud and Robert Feil for providing Oct4-GFP mice, Myriam Boyer-Clavel and the Montpellier RIO Imaging platform for the flow cytometry, Thierry Gostan for help with R programming, and Julie Borgel for discussions and technical assistance. This research was supported by the CEFIC Long Research Initiative (LRI-EMSG49-CNRS-08), the CNRS/INSERM Atip-Avenir program, the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC contract SFI20101201555), and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-07-BLAN-0052-02).

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.130997.111.

References

- Borgel J, Guibert S, Li Y, Chiba H, Schubeler D, Sasaki H, Forne T, Weber M 2010. Targets and dynamics of promoter DNA methylation during early mouse development. Nat Genet 42: 1093–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawlaty MM, Ganz K, Powell BE, Hu YC, Markoulaki S, Cheng AW, Gao Q, Kim J, Choi SW, Page DC, et al. 2011. Tet1 is dispensable for maintaining pluripotency and its loss is compatible with embryonic and postnatal development. Cell Stem Cell 9: 166–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Jacobsen SE, Reik W 2010. Epigenetic reprogramming in plant and animal development. Science 330: 622–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo S, Jaco I, Fraga MF, Chen T, Li E, Esteller M, Blasco MA 2006. DNA methyltransferases control telomere length and telomere recombination in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol 8: 416–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guibert S, Forne T, Weber M 2009. Dynamic regulation of DNA methylation during mammalian development. Epigenomics 1: 81–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajkova P, Erhardt S, Lane N, Haaf T, El-Maarri O, Reik W, Walter J, Surani MA 2002. Epigenetic reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells. Mech Dev 117: 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajkova P, Ancelin K, Waldmann T, Lacoste N, Lange UC, Cesari F, Lee C, Almouzni G, Schneider R, Surani MA 2008. Chromatin dynamics during epigenetic reprogramming in the mouse germ line. Nature 452: 877–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajkova P, Jeffries SJ, Lee C, Miller N, Jackson SP, Surani MA 2010. Genome-wide reprogramming in the mouse germ line entails the base excision repair pathway. Science 329: 78–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4: 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirtle RL, Skinner MK 2007. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet 8: 253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N, Dean W, Erhardt S, Hajkova P, Surani A, Walter J, Reik W 2003. Resistance of IAPs to methylation reprogramming may provide a mechanism for epigenetic inheritance in the mouse. Genesis 35: 88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Inoue K, Ono R, Ogonuki N, Kohda T, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ogura A, Ishino F 2002. Erasing genomic imprinting memory in mouse clone embryos produced from day 11.5 primordial germ cells. Development 129: 1807–1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees-Murdock DJ, De Felici M, Walsh CP 2003. Methylation dynamics of repetitive DNA elements in the mouse germ cell lineage. Genomics 82: 230–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Lees-Murdock DJ, Xu GL, Walsh CP 2004. Timing of establishment of paternal methylation imprints in the mouse. Genomics 84: 952–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ito M, Zhou F, Youngson N, Zuo X, Leder P, Ferguson-Smith AC 2008. A maternal-zygotic effect gene, Zfp57, maintains both maternal and paternal imprints. Dev Cell 15: 547–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, Nery JR, Lee L, Ye Z, Ngo QM, et al. 2009. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature 462: 315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maatouk DM, Kellam LD, Mann MR, Lei H, Li E, Bartolomei MS, Resnick JL 2006. DNA methylation is a primary mechanism for silencing postmigratory primordial germ cell genes in both germ cell and somatic cell lineages. Development 133: 3411–3418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A 2010. Epigenetic modifications in pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nat Biotechnol 28: 1079–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan HD, Dean W, Coker HA, Reik W, Petersen-Mahrt SK 2004. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase deaminates 5-methylcytosine in DNA and is expressed in pluripotent tissues: implications for epigenetic reprogramming. J Biol Chem 279: 52353–52360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda M, Yamagiwa A, Yamamoto S, Nakayama T, Tsumura A, Sasaki H, Nakao K, Li E, Okano M 2006. DNA methylation regulates long-range gene silencing of an X-linked homeobox gene cluster in a lineage-specific manner. Genes Dev 20: 3382–3394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohinata Y, Payer B, O'Carroll D, Ancelin K, Ono Y, Sano M, Barton SC, Obukhanych T, Nussenzweig M, Tarakhovsky A, et al. 2005. Blimp1 is a critical determinant of the germ cell lineage in mice. Nature 436: 207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp C, Dean W, Feng S, Cokus SJ, Andrews S, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE, Reik W 2010. Genome-wide erasure of DNA methylation in mouse primordial germ cells is affected by AID deficiency. Nature 463: 1101–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenneville S, Verde G, Corsinotti A, Kapopoulou A, Jakobsson J, Offner S, Baglivo I, Pedone PV, Grimaldi G, Riccio A, et al. 2011. In embryonic stem cells, ZFP57/KAP1 recognize a methylated hexanucleotide to affect chromatin and DNA methylation of imprinting control regions. Mol Cell 44: 361–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde C, Zhang Y, Reinhardt R, Jeltsch A 2010. BISMA—fast and accurate bisulfite sequencing data analysis of individual clones from unique and repetitive sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 11: 230 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Matsui Y 2008. Epigenetic events in mammalian germ-cell development: reprogramming and beyond. Nat Rev Genet 9: 129–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Kimura T, Kurokawa K, Fujita Y, Abe K, Masuhara M, Yasunaga T, Ryo A, Yamamoto M, Nakano T 2002. Identification of PGC7, a new gene expressed specifically in preimplantation embryos and germ cells. Mech Dev 113: 91–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Yoshimizu T, Sato E, Matsui Y 2003. Erasure of methylation imprinting of Igf2r during mouse primordial germ-cell development. Mol Reprod Dev 65: 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki Y, Hayashi K, Itoh K, Mizugaki M, Saitou M, Matsui Y 2005. Extensive and orderly reprogramming of genome-wide chromatin modifications associated with specification and early development of germ cells in mice. Dev Biol 278: 440–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood SA, Tomizawa SI, Krueger F, Ruf N, Carli N, Segonds-Pichon A, Sato S, Hata K, Andrews SR, Kelsey G 2011. Dynamic CpG island methylation landscape in oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Nat Genet 43: 811–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK, Speed T 2003. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods 31: 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw NC, Whitelaw E 2008. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in health and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev 18: 273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SC, Zhang Y 2010. Active DNA demethylation: many roads lead to Rome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 607–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuta Y, Kurimoto K, Ohinata Y, Seki Y, Saitou M 2006. Gene expression dynamics during germline specification in mice identified by quantitative single-cell gene expression profiling. Biol Reprod 75: 705–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki Y, Mann MR, Lee SS, Marh J, McCarrey JR, Yanagimachi R, Bartolomei MS 2003. Reprogramming of primordial germ cells begins before migration into the genital ridge, making these cells inadequate donors for reproductive cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 12207–12212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki Y, Low EW, Marikawa Y, Iwahashi K, Bartolomei MS, McCarrey JR, Yanagimachi R 2005. Adult mice cloned from migrating primordial germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 11361–11366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimizu T, Sugiyama N, De Felice M, Yeom YI, Ohbo K, Masuko K, Obinata M, Abe K, Scholer HR, Matsui Y 1999. Germline-specific expression of the Oct-4/green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene in mice. Dev Growth Differ 41: 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]