Abstract

The HIV epidemic in higher-income nations is driven by receptive anal intercourse, injection drug use through needle/syringe sharing, and, less efficiently, vaginal intercourse. Alcohol and noninjecting drug use increase sexual HIV vulnerability. Appropriate diagnostic screening has nearly eliminated blood/blood product-related transmissions and, with antiretroviral therapy, has reduced mother-to-child transmission radically. Affected subgroups have changed over time (e.g., increasing numbers of Black and minority ethnic men who have sex with men). Molecular phylogenetic approaches have established historical links between HIV strains from central Africa to those in the United States and thence to Europe. However, Europe did not just receive virus from the United States, as it was also imported from Africa directly. Initial introductions led to epidemics in different risk groups in Western Europe distinguished by viral clades/sequences, and likewise, more recent explosive epidemics linked to injection drug use in Eastern Europe are associated with specific strains. Recent developments in phylodynamic approaches have made it possible to obtain estimates of sequence evolution rates and network parameters for epidemics.

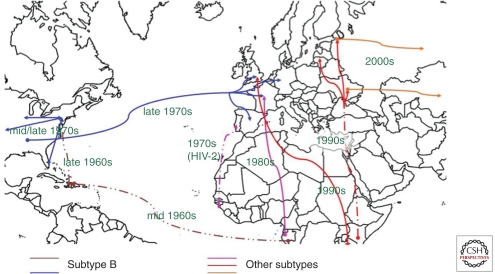

Molecular phylogenetic approaches have traced the evolutionary history of HIV strains, showing that HIV spread from central Africa to the United States and then to Europe, as well as directly from Africa to Europe.

The social and molecular epidemiology of the HIV epidemic in higher-income countries has had characteristics quite distinct from the situation in the most highly affected regions of sub-Saharan Africa (Kilmarx 2009). Since the recognition of AIDS in 1981, high-income nations have had their own characteristic epidemic trends, transmission dynamics, affected subgroups, and recent trends. We focus on the higher-income nations of Western Europe, North America, and many nations of Oceania, including Australia and New Zealand. We acknowledge that one must also consider the proximity of Eastern Europe, Caribbean, and the rest of Oceania, acknowledging that most of them are high- or low- middle-income nations, not high income; neither are they as resource-limited as those reviewed by Williamson and Shao 2011 (Haiti and a few others are exceptions). We seek to summarize a complex matrix of biological phenomena in a complex disease that is steeped in human behavior and stigma, fear, and prejudice (Remien and Mellins 2007; Mahajan et al. 2008).

HIV/AIDS shares transmission characteristics with other sexual and blood-borne agents. Higher sexual mixing rates and lack of condom use are conspicuous risk factors (Vermund et al. 2009). Reuse of syringes and needles, receipt of contaminated blood or blood products, or occupational needle sticks in a health care setting all are associated with HIV infection. Mother-to-child transmission prepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum via breast milk feeding is an additional major transmission route (Fowler et al. 2010). Since the advent of antiretroviral therapy and routine screening of women in pregnancy, the number of infants infected with HIV in high-income nations has plummeted, although cases still occur (Birkhead et al. 2010; Lampe et al. 2010; Whitmore et al. 2010, 2011).

HIV is the most dangerous of the sexual and blood-borne diseases in its epidemic potential and its virulence. Our inability to cure HIV infection adds to the complexity of its chronic management. In addition, HIV seems to be spread more like hepatitis B virus (HBV) than any other infectious agent (sex, blood, or perinatal), although it is not as infectious as HBV (Barth et al. 2010; Dwyre et al. 2011). Classical sexually transmitted diseases (SDIs) are rarely blood-borne, although sexual and perinatal HIV transmission occurs as with HBV, herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2), syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted overwhelmingly through blood-borne routes, with sexual and perinatal cases occurring rarely. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is transmitted most often via breast milk; HTLV-2 transmission has been reported via needle exchange. Although HIV is surely reminiscent of other infectious agents, its unique CD4+ T-lymphocyte tropism helps dictate its exact transmission routes and frequencies (see Shaw and Hunter 2011).

Sadly, the early history of the HIV epidemic is one of missed opportunities, over and over, in country after country. This continues to the present day (Mahy et al. 2009). The failure to see the now-obvious parallels in risk with HBV led to a failure to protect the blood supply in the early 1980s during an intense transmission period, resulting in the preventable infection of thousands of blood recipients, particularly men with hemophilia. The failure to aggressively advocate sexual risk reduction, including delayed coital debut among adolescents, reduced numbers of sexual partners, and use of condoms, led to unknown numbers of same sex and heterosexual HIV transmissions. Even in 2011, members of the U.S. Congress demonize such organizations as Planned Parenthood that advocate pregnancy and HIV/STD prevention, empowering the poor and the young to access their unmet needs for these services. The failure to promptly, consistently, and extensively provide clean needles and syringes for IDUs (and for health care in resource-limited settings) led to an estimated 4394 to 9666 preventable infections in the U.S. alone (33% of the incidence in IDUs) from 1987 to 1995, costing society US$244 to US$538 million (Lurie and Drucker 1997). The U.S. Federal Government did not lift its ban on funding for needle/syringe exchange programs (N/SEP) until 2009, despite overwhelming evidence indicating its effectiveness in preventing HIV transmission. Although beyond the scope of this work, the failure of many high-income nations to liberate public health professionals and community activists to address the problem using evidence-based solutions, rather than using HIV/AIDS as a politicized point of ideological conflict, costs, and continues to cost, lives (Mathers et al. 2010).

Here we present the characteristics of viral evolution as seen in high-income nations, primarily in the northern hemisphere, including issues of viral diversity and transmission. We further present a brief review of major risk exposures for HIV and their importance in the epidemic patterns of higher-income nations.

OVERVIEW OF VIRUS EVOLUTION AND RATES OF CHANGE

The rapidity of HIV evolution is such a prominent feature of the virus that it has attracted extensive attention since the development of thermostable polymerases allowed it to be easily studied (Meyerhans et al. 1989; Balfe et al. 1990; Wolfs et al. 1990). This required a revolution in the thinking of virologists, many of whom had previously been familiar with the evolution of DNA viruses, which diverge slowly and often in parallel with their hosts (Sambrook et al. 1980).3 These differences gradually became apparent more widely, and both the data and methodology developed (Crandall et al. 1999) to reveal the conflicting forces that act on the HIV population to force the highest rates of amino acid substitution known (under selection by drugs, cytotoxic T-lymphocytes [CTLs], or by neutralizing antibody) (Frost et al. 2000, 2005) (see Carrington and Alter 2011; Lackner et al. 2011; Overbaugh and Morris 2011; Swanstrom and Coffin 2011; Walker and McMichael 2011) and yet allow chance effects to play a significant role in viral evolution (Leigh Brown 1997; Leigh Brown and Richman 1997). The impact on HIV evolution of the complexity of the processes and forces involved, and their interactions, have been reviewed effectively elsewhere (Rambaut et al. 2004), so only recent developments will be looked at further here.

Powerful, statistically rigorous techniques for estimation of molecular evolutionary parameters are now available and have been applied to HIV sequences from infected populations to estimate both the rate of evolutionary change and dates of divergence (Drummond and Rambaut 2007). These studies, however, have a long history: Estimates of the rate of synonymous nucleotide substitution made 20 years ago (Balfe et al. 1990; Wolfs et al. 1990) of the order of 5 × 10−3 were not very different from those made recently (2–6 × 10−3) (Korber et al. 2000; Robbins et al. 2003; Lewis et al. 2008). What has changed is that such estimates can now be made on large and complex data sets instead of being restricted to relatively uniform well-defined outbreaks. The first demonstration of the power of the new approaches was the timing of the origin of the pandemic HIV “M” strain to the early 20th century (Korber et al. 2000) (see also Sharp and Hahn 2011). More recently they have allowed estimates to be made of the origins of diverse epidemics in different countries and risk groups (Lemey et al. 2003; Salemi et al. 2008). Finally, in combination with very large data sets, these approaches have allowed a bridge to be made across to infectious disease epidemiology, as under certain assumptions, the viral evolutionary history can be used to estimate critical epidemiological parameters that are not accessible from other routes (Volz et al. 2009).

Major Clades

Across the globe, comparisons between viruses isolated in the 1980s from different populations of HIV-infected individuals frequently showed much greater differences than were seen within populations. These became termed “subtypes,” although, as there is no clear serological distinction, the generic term “clade” is more appropriate. National epidemics were initially only associated with one clade, with the exception of Thailand, where two major forms were recognized early on. The distinction between “Thai A” (now called CRF01) and “Thai B” strains (Ou et al. 1993) gave rise to the name of the HIV clade that had spread across the United States and Western Europe in the 1980s: “subtype B.” Likewise, East Africa was another locus where two subtypes became established and cocirculated: the “A” and “D” clades (see Sharp and Hahn 2011; Williamson and Shao 2011). In addition, owing to the recombinogenic nature of HIV replication, recombinants between these clades arise wherever cocirculation occurs, and several have given rise to epidemics themselves; these have become termed circulating recombinant forms, or “CRFs” (Robertson et al. 2000), whose names identify the parent strains. Classification systems are frequently superseded by later knowledge, and this is no exception, as the best known “recombinant,” the Thai “A” strain or CRF01/AE, evidence for whose hypothesized second parent “E” has always been lacking, now appears rather to be a divergent form of subtype A (Anderson et al. 2000). Similarly, it appears that CRF02/AG is a parental, rather than recombinant form (Abecasis et al. 2007). In recent years the genetic complexity of the global epidemic has increased substantially, with more than 40 CRFs now recognized (Kuiken et al. 2010), instead of the original four (Robertson et al. 2000).

Genetic diversity of HIV has always been greatest in west central Africa. Here all major clades (A–K, with the exception of the “B” and missing “E” clades) have been found, and indeed, especially among strains from the 1980s, many intermediate and unclassifiable forms (Kalish et al. 2004), as expected for the region where the pandemic originated (Rambaut et al. 2001; see Sharp and Hahn 2011). The lack of major biological differences among HIV clades has led to the view that their distinctiveness has arisen primarily through the stochastic process of founder events, via the chance appearance of virus from a particular origin in a highly susceptible population (Rambaut et al. 2004). Dating the divergence events using molecular clock–based approaches suggests the divergence of the major clades, which took place here, occurred around the middle of the 20th century (Korber et al. 2000), but seeding of the northern hemisphere has often been from other parts of Africa, and after distinct clades emerged.

Virus Diversity in the Northern Hemisphere

North America

Given what is known of the pathogenesis of HIV disease, the origin of HIV infection in the northern hemisphere had to have predated the original description of AIDS in 1981 by several years. Indeed, serosurveillance studies showed that the prevalence of HIV infection among men who have sex with men (MSM), which was 20%–40% by the early 1980s, was already between 4% and 7% in San Francisco, New York, and Los Angeles in the late 1970s (Coutinho et al. 1989). Nevertheless, analysis of nucleotide sequences from strains isolated in the 1980s (Robbins et al. 2003) confirmed the earlier estimate (Korber et al. 2000), that the common ancestor of the HIV strains found in the United States preceded that period by approximately 10 years. The final piece in this puzzle was found when a number of sequences of HIV from Haitian immigrants to the United States who were HIV-infected in the 1980s were compared to United States sequences (Gilbert et al. 2007). These belonged to the same (B) clade but all branched off earlier. Using similar dating approaches, the origin of the U.S. clade is confirmed at 1969, whereas the common ancestor of the Haitian strains predated this by a few years at 1966 (Gilbert et al. 2007). This is the closest that can currently be reached to the reconstruction of the origin of the northern hemisphere epidemic and the B subtype. The B subtype was not found among early sequences from Africa (it was introduced later to South African MSM); the most closely related sequences from Africa are from the D clade, within which, when early African sequences are included, the B clade nests (Kalish et al. 2004). The date for this B-D divergence is around 1954 (Gilbert et al. 2007), consistent with the placing of a sequence fragment from a sample from Kinshasa in 1957 very near the split, but in the D clade (Korber et al. 2000). It has been speculated that the return in the 1960s of expatriate Haitians from the diaspora of the 1950s to Francophone West Africa was responsible. It is known that AIDS was recognized in Haiti much earlier than anywhere else, outside the three U.S. cities (Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco), and that initially the infection was predominantly in men, only becoming a generalized epidemic over the next decade (Pape and Johnson 1993).

The reconstruction, through molecular phylogenetics, of the connections which linked a then obscure syndrome among a number of homosexual men in U.S. cities to central Africa, where the infection had not at the time been recognized, is the most striking of many examples where sequencing of viral strains has yielded important information for epidemiology. The pattern of introduction in Europe, however, was more complex.

Europe 1980–1990

Identification of AIDS in Europe followed its recognition in the United States. Once recognized, retrospective investigation identified a few cases that could be traced back to the 1970s, but among MSM many of the earliest cases had direct recent links to the United States (Pinching 1984), and all MSM at that time were infected with a virus later characterized as the B clade. These introductions of the virus probably continued: It has been estimated by reconstructing viral lineages among MSM in the United Kingdom that at least six lineages are represented in present day populations, most, but not all, of which had an origin in the early 1980s (Hue et al. 2005). These were already distinct B clade lineages which represented independent introductions into the United Kingdom. Another introduction that appeared to be independent was into the injecting drug user population of northern Europe (Lukashov et al. 1996), among whom the virus was remarkably similar, whether in Amsterdam, Dublin, or Edinburgh, reflecting another founder introduction to a highly susceptible population (Leigh Brown et al. 1997; Op de Coul et al. 2001). The distinctiveness of this strain from that in MSM (Kuiken and Goudsmit 1994; Holmes et al. 1995; Kuiken et al. 1996) contrasted with that of hemophiliacs in Edinburgh, infected from locally prepared factor VIII in the early 1980s, whose virus could be linked directly to that found in Scottish MSM (Brown et al. 1997). Interestingly, the distinction is less apparent in IDUs from southern Europe from this period, whose sequences overlapped more with those from MSM (Lukashov et al. 1996). The epidemics also behaved differently in these two areas, stabilizing in the north while leading to the highest prevalence in Europe in Spain, Italy, and Portugal (Hamers et al. 1997).

Europe did not just receive virus from the United States, however; it was also imported from Africa directly (Fig. 1). Molecular epidemiological evidence suggests strongly that since the 1960s, HIV-1 and HIV-2 have been transported from Africa to North America/Caribbean and Europe, and have been transported, too, between the European and North American continents (Fig. 1). Cases were recognized almost as early among individuals having links to Africa (Alizon et al. 1986), and these led to local epidemics of non-B clades. One hospital in Paris recorded eight clades, including CRF01AE by 1995 (Simon et al. 1996), but although several clades were recorded in the United Kingdom, in relative terms, the prevalence of non-B strains at that time was low (Arnold et al. 1995). Patterns of strain prevalence reflected past colonial links and frequency of contemporary interchange, strikingly so in the case of Portugal, the only country outside West Africa to record a significant epidemic of HIV-2 (De Cock and Brun-Vezinet 1989), reflecting the location of its former colony Guinea-Bissau at the epicenter of the HIV-2 epidemic. The molecular distinctions between European epidemics extended to the HIV-1 clades, however, with clade G, associated with West Africa, being well represented in Portugal but not elsewhere in Western Europe. However, it gave rise to an iatrogenic outbreak in southern Russia in 1988 (in Elista, 300 km south of Volgograd) (Bobkov et al. 1994), and the devastating iatrogenic outbreak in Romanian children (Hersh et al. 1991b) was associated with clade F (Thomson et al. 2002).

Figure 1.

Dates of likely introductions of HIV to various parts of the world since the 1960s.

Europe 1990–2005

Those initial introductions into Western Europe led to epidemics in different risk groups in different regions often distinguished by viral clade, thus in France, transmission among IDUs and MSM remained of the B subtype, whereas heterosexual transmission was more commonly of a variety of non-B subtypes, as was the case in Switzerland (Op de Coul et al. 2001). Non-B subtypes were present but rare in the UK until 1995, after which a substantial increase in immigration from southern Africa, particularly Zimbabwe, led to a dramatic rise in subtypes C and A (Parry et al. 2001). By 2005, the prevalence of non-B clades taken together equaled the B clade, and recently, in both France and the United Kingdom, there has been noticeable, and nonreciprocal, crossover of non-B clades into MSM (de Oliveira et al. 2010; Fox et al. 2010). Similarly, Swiss investigators have confirmed changes in B clade viral transmission over time (Kouyos RD et al. 2010).

The breakup of the Soviet Union and the Eastern European bloc at the end of the 1980s, the subsequent economic decline in some of these countries, and the freeing of travel in the 1990s was a combination that had devastating consequences regarding HIV transmission. A very large population of injection drug users adopting highly unsafe practices (Dehne et al. 1999) was the focus of massive, explosive epidemics (Aceijas et al. 2004). Virus obtained in 1995 from Donetsk in eastern Ukraine and Krasnodar in southern Russia, about 350 km distant, were very similar, with about 2% divergence in the C2-V3 region, and belonged to subtype A but had some unique features (Bobkov et al. 1997) that allowed it to be easily tracked as it spread from Ukraine to St. Petersburg and Estonia in the 1990s and then in the 21st century, on to other parts of Russia, including Moscow and Irkutsk (Siberia) (Bobkov et al. 2001), as well as neighbors, including Kazakhstan (Bobkov et al. 2004) and the Baltic states (Zetterberg et al. 2004). Soon after the original outbreak in Ukraine, there was an explosive outbreak in the Former Soviet Union enclave of Kaliningrad. This was characterized by a quite distinct A/B recombinant (Liitsola et al. 1998), which detailed analysis suggests was derived from subtype B and A variants found among IDUs in Ukraine (Liitsola et al. 2000).

DRUG-RESISTANT HIV AND ITS TRANSMISSION

From very early days of antiretroviral therapy, the transmission of drug-resistant virus was already being recorded. Clear evidence was presented in three different countries that before 1995, mutations at amino acid 215 in reverse transcriptase were present in untreated individuals (Perrin et al. 1994; de Ronde et al. 1996; Quigg et al. 1997). Systematic surveys of the presence of such mutations have followed, initially linked to studies of acute infection (Little et al. 1999, 2002). Later studies extended this to include individuals in chronic infection, which could be studied in larger numbers (Weinstock et al. 2004; Cane et al. 2005; Wensing et al. 2005; Chaix et al. 2009; Vercauteren et al. 2009). The overall picture appears to indicate an increase in transmission of drug resistance in the late 1990s as more individuals went on therapy (Leigh Brown et al. 2003), which was followed by a decrease, as more individuals on therapy became completely suppressed, but the exact timing was difficult to determine from chronic infection studies and may have varied between countries. In addition, there were differences in the classes of drug that were most strongly affected, with nonnucleoside resistance consistently appearing at a higher frequency than nucleoside or protease inhibitor resistance, reflecting differences in transmission fitness of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) resistance-associated mutations (Leigh Brown et al. 2003). Most countries in the developed world have developed systematic surveillance for transmitted resistance to minimize its impact on individualized antiretroviral therapy.

HIV Transmission Networks and Dynamics Revealed by Molecular Epidemiology

Analyses of nucleotide sequence variation have been used for almost 20 years to describe the relationships between viral strains within infected communities (Balfe et al. 1990; Kuiken and Goudsmit 1994; Leigh Brown et al. 1997). Recently a combination of greatly enhanced data sets and improvements in methodology have allowed much more detail to be added to the depictions of the structure of the transmission networks deduced from sequence data. This has shown that some risk groups (e.g., injection drug users) can give rise to tight clusters where many individuals may share very similar sequences (Brenner et al. 2008; Yerly et al. 2009). In addition, for the first time it has become possible to investigate the dynamics of the epidemic based on such data. Although many studies of sexual behavior have shown that individuals can vary greatly in their number of sexual partners over time and this concept has underpinned many epidemiological models of HIV transmission, however, contact tracing has been shown to be poor at recovering the HIV transmission network relative to other infections (Yirrell et al. 1998; Resik et al. 2007). The development of the field of molecular phylodynamics, used first to estimate dates of the origin of the zoonotic transmission of HIV, provided new routes to obtain such parameter estimates, which can be applied to small-scale intensive studies of specific outbreaks, as well as to obtain global estimates relating to long-term spread.

By analyzing the transmission network revealed by partial pol gene sequences obtained during routine clinical care, it was shown that the cluster size distribution of MSM attending a single large clinic in London had a long right tail, implying many individuals were associated with large clusters: In fact, of individuals in clusters >2, 25% were found in clusters ≥10 (Lewis et al. 2008). Within these clusters, 25% of intervals between transmissions, inferred from the dated transmission network, were 6 months or less, implying a significant role for acute infection in driving the epidemic (Cohen et al. 2011).

Extending this work to non-B subtypes, primarily associated with heterosexual infection in the United Kingdom, revealed that although clustering could be detected, it was much less extensive than among MSM, and the mean intertransmission interval was substantially longer. In fact, there were hardly any intervals ≤6 mo, indicating important differences between the epidemics in the two risk groups (Hughes et al. 2009).

Example of Phylodynamic Modeling from the United Kingdom

The phylodynamic approach has been extended to a population survey of viral sequences from the entire U.K. HIV epidemic among MSM (Leigh Brown et al. 2011). Partial pol gene sequences from approximately two-thirds of the MSM under care in the United Kingdom in 2007 have been analyzed. Of those linked to any other, 29% were linked to only 1, 41% linked to 2–10, and 29% linked to ≥10. In striking contrast, a recent update on transmission of non-B subtypes in the United Kingdom has revealed that only one large cluster is attributable to heterosexual transmission, all others being “crossovers” to IDU or MSM (S Hue et al., unpubl.). It has thus been possible to obtain estimates of network parameters for the entire epidemic in the United Kingdom. The scale of sequence data coverage greatly exceeds that generally achievable in epidemiological surveys of sexual contact. This provides an opportunity to make critical inferences on the impact of clustering for the epidemic, and its importance for intervention strategies. It is well understood that under certain conditions there is no “epidemic threshold,” such that a randomly distributed (i.e., untargeted) intervention, will be unable to stop the epidemic (Keeling and Eames 2005). The estimates of epidemiological parameters based on data from routinely performed HIV genotyping tests therefore provide critical information for the successful and efficient implementation of transmission interventions including vaccination (when available), and for both antiretroviral treatment for prevention among infectous seropositives and preexposure prophylaxis among seronegatives (Burns et al. 2010; Kurth et al. 2011).

RISK EXPOSURES: MSM

The AIDS epidemic was recognized first among MSM in Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco. Clinicians were alarmed to see gay men who presented with low CD4+ T-lymphocytes and opportunistic infections like Pneumocystis jirovecii (P. carinii is the form seen in animals, now distinguished from the former human form) or malignancies like Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) (Centers for Disease Control 1981; Gottlieb et al. 1981). P. jirovecii pneumonia was a disease of the profoundly immunosuppressed, as with persons on cancer treatment or with profound malnutrition. KS in high-income countries was previously recognized as a disease of elderly men in the Mediterranean basin that was far more indolent than the form that was later associated with HIV infection (Di Lorenzo 2008). Both were previously unknown in apparently healthy young American men. A rush on the rarely used drug pentamidine for young men without coexisting cancer from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1981 was a sentinel event that alerted public health officials to the new P. jirovecii outbreak (Selik et al. 1984). In quick succession, MSM with the same opportunistic infections (OIs) or malignancies (OMs) were reported from around the world.

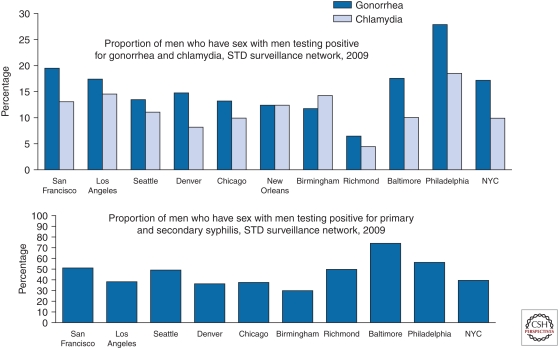

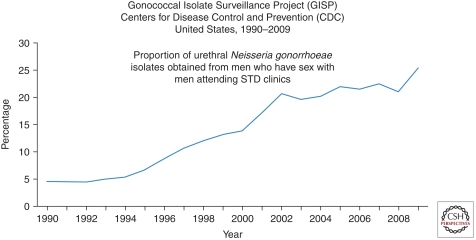

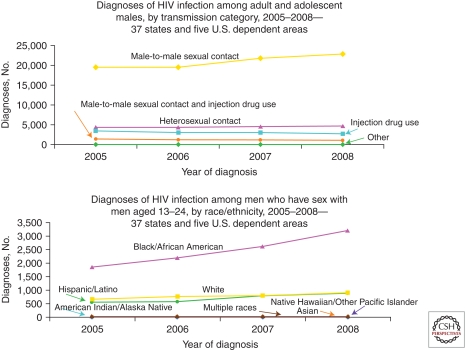

From 1981 through the present (2011), MSM have remained the most afflicted group in high-income nations. For example, about half of all cases in the United States in 2009 are estimated to have occurred in MSM (El-Sadr et al. 2010). STD rates remain high for MSM in major U.S. cities, as documented for gonorrhea and chlamydia by the CDC STD Surveillance Network in 2009 (Fig. 2). Trends have been dramatically upward for gonorrhea in the CDC Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project from 1992 to 2009 (Fig. 3). Despite the worrisome trends among MSM as a whole, the proportion of all reported HIV/AIDS cases that have occurred among White MSM in the United States has dropped markedly from the 80+% range in the early 1980s to 25% in 2010 (Fig. 4). At the same time, the proportion of cases among Black MSM in the United States has risen from just a couple percent in the early 1980s to about 24% in 2010 (El-Sadr et al. 2010). Both the prevalence and incidence rates for HIV/AIDS among Black MSM are now higher (Fig. 4) than any other subgroup of Americans, including IDUs. In Canada, Mexico, Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and higher-income island nations of the Caribbean, MSM continue to be the principal driver of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. This is also true of lower-income nations of Latin America and represents a growing proportion of cases in urban Asia (Baral et al. 2007; van Griensven and de Lind van Wijngaarden 2010).

Figure 2.

Proportion of men who have sex with men who had gonorrhea and chlamydia (top) and syphilis (bottom) in the STD (sexually transmitted disease) Surveillance Program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States, 2009.

Figure 3.

Proportion of urethral Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates obtained from men who have sex with men attending sexually transmitted disease clinics from the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States, 1990–2009.

Figure 4.

Diagnoses of HIV infection among adolescents and adult males by transmission category (top; all ages) and race/ethnicity (bottom; ages 13–24 years), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 37 states and five dependent areas of the United States, 2005–2008.

The epidemic spread exceedingly among MSM, reaching peaks of greater than 50% prevalence of young MSM in the high-prevalence neighborhoods of three cities where it was first recognized (Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco) by 1984. It is estimated that MSM incidence rates in the United States rose to 15% per annum in the early 1980s in high-prevalence communities. Rates rose among MSM in Western Europe, Australia, Canada, and other higher-income, non-Muslim countries, although not quite as quickly and generally not as high as in the United States. In the mid-1980s, incidence rates declined in the Western world, likely due to both reduced risk behaviors and to a saturation effect of infection in the high-risk pool (i.e., the probability of becoming infected dropped owing to the uninfected persons not sexually mixing with infected, higher-risk persons). Evidence of reduced sexual risk taking by MSM in the late 1980s is found in declines in rectal gonorrhea and syphilis rates among MSM beginning in the mid-1980s. However, rates of STDs have rebounded among MSM, particularly among the young (Fig. 4). In 2009 surveillance, it is likely that such phenomena as “prevention fatigue,” young MSM without a memory of AIDS in the pretreatment era, and minority MSM who are not reached by prevention messages targeting LGBTI communities (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex) are contributing to the worrisome trends in nations as diverse as the United States and China (Wolitski et al. 2001; Rietmeijer et al. 2003; Johnson et al. 2008; Scheer et al. 2008; Xu et al. 2010; Hao et al. 2011).

Both behavior and biology are relevant to the MSM epidemic. Multiple sexual partners, use of recreational drugs and alcohol proximate to sex, and the practice of unprotected anal intercourse all increase HIV risk markedly. Rectal exposure to HIV is more likely to infect than vaginal exposure (Powers et al. 2008; Boily et al. 2009; Baggaley et al. 2010). This is likely owing to the large surface area and thin epithelial layer of the rectum, its capacity for fluid absorption, trauma during anal sex, and the high numbers of immunological target cells in the gastrointestinal tract (Dandekar 2007; Brenchley and Douek 2008). Antiretroviral drugs taken orally by HIV-uninfected MSM as preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) can protect against rectal infection from HIV, but only when these drugs are adhered to and systemic plasma levels are detectable (Grant et al. 2010). This was predicted by nonhuman primate challenge studies (Garcia-Lerma et al. 2008). It is not yet known whether topical PrEP in the form of rectal microbicides will be effective biologically and, if so, whether they will be used enough to make a difference in the epidemic (McGowan 2011). Circumcision is not likely to benefit MSM, as the principal risk derives from receptive anal intercourse (Millett et al. 2008; Vermund and Qian 2008).

RISK EXPOSURES: INJECTION DRUG USE, NEEDLE SHARING, AND USE OF OTHER DRUGS/ALCOHOL

Both illicit and licit drug and alcohol use are associated with HIV risk in several ways (Samet et al. 2007). Opioids like heroin and stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamines may be injected using needles and syringes that have been shared with other drug users. This sharing of injection “works” commonly shares blood from one user to another. This injection route is highly efficient in spreading HIV, as was seen in both North America and Western Europe (Booth et al. 2006, 2008). Needle/syringe exchange programs (N/SEP) are effective at reducing HIV transmission among IDUs, but have been politically charged (Des Jarlais 2000; Downing et al. 2005; Shaw 2006; Tempalski et al. 2007). Some politicians and policymakers have argued that N/SEP should be banned because they will increase IDU use, although there is no evidence of this. Others have argued for the bans because they perceive N/SEP as an inadequate response to a large need of comprehensive drug abuse prevention and treatment programs; support of N/SEP, they have argued, will discourage funding for the more comprehensive response.

Given the policy debates, it is not surprising that some countries were far more aggressive and successful in controlling the epidemic than others (Mathers et al. 2010). Australia is one model of IDU risk reduction efficiency. Making clean needles and syringes available widely, from any pharmacy as well as special services in neighborhoods with high drug use rates, is credited for maintaining IDU HIV prevalence <2% for the past 30 years (Burrows 1998). In addition, the Australians have mainstreamed methadone use into the world of the general practitioner, reducing stigma and increasing access. Similarly, aggressive public health responses in Australia, Canada, and several Western European countries may have blunted the magnitude of HIV in their IDUs using N/SEP, and opioid substitution therapy. Even “medically supervised injecting centres” may have played a role, a topic of current study (Fischer et al. 2002).

Other nations were not as fortunate as Australia in having policies suitable to control the epidemic among IDUs (Lurie and Drucker 1997; Drucker et al. 1998). In the United States, for example, federal funding for N/SEP was banned by Congress until the early Obama administration (Millett et al. 2010), a ban with the active or the tacit approval of Reagan, G.H.W. Bush, Clinton, and G.W. Bush administrations. Funding for opioid substitution therapy did not meet the demand and waiting lists to join such programs were common. Doctors and venues licensed to distribute methadone are highly restricted, in direct contrast to the Australian approach. During that time, IDU incidence was high until community, local, and state initiatives introduced N/SEP programs that proved highly effective in reducing HIV incidence in American IDUs, as had been achieved by such programs earlier in Europe (Kwon et al. 2009; Jones et al. 2010; Palmateer et al. 2010).

Russia has had even worse policies and laws than the United States, banning opioid substitution therapy (both methadone and buprenorphine) altogether (as of 2011). Russia also has very limited N/SEP, and continues to experience some of the highest HIV seroconversion rates in the world among its IDUs (Aceijas et al. 2007; Sarang et al. 2008). The rest of Europe is a patchwork of both progressive and dysfunctional public policies vis-à-vis risk reduction for IDUs, depending in large part on whether the given nation is strongly connected to the European Community or whether they are more influenced by Russia. In summary, countries that have taken a more punitive, less pragmatic public health approach have been beleaguered by ongoing HIV spread among IDUs.

There has been a substantial increase in the 1980s and subsequent decrease of incidence and prevalence among IDUs in most high-income nations. Modeling suggests that the greater the volume of “dead space” in a used syringe, the higher the risk of residual blood infecting another drug user, as derived from ecological data on local IDU prevalence and local syringe usage patterns (Bobashev and Zule 2010). Evidence from the 1990s suggested that use of clean needles and syringes had dropped the likelihood of HIV transmission and acquisition substantially (Heimer 2008). The principal challenge is reaching all those IDUs who need N/SEP, drug treatment, and ancillary services, as well as to stem the tide of new users recruited among the young. Unfortunately, IDU itself seems to be expanding worldwide, partly owing to poor addiction and HIV care for many IDUs already infected (Wolfe et al. 2010).

Already highly endemic in Asia where most of the world's poppies are grown, the epidemic has been a principal driver of the epidemic in Iran, Pakistan, eastern India, China, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. In Africa, new reports of IDU in such unexpected venues as South Africa and Tanzania suggest the need for new research and action in that already HIV-beleaguered continent. Eastern Europe has seen some success in risk and incidence reduction, as in Estonia and Ukraine, but Russia continues to see robust HIV incidence among its IDUs owing to its failure to embrace opiate agonist therapy and vigorous N/SEP efforts (Sarang et al. 2007; Bobrova et al. 2008; Elovich and Drucker 2008; Krupitsky et al. 2010). That IDUs often cannot access clean needles and “works” when they need to in many countries of Eastern Europe and even in the United States, HIV continues to spread and cause preventable disease.

Non-IDU drug use and alcohol abuse were recognized early on as cofactors for high-risk sexual activity. “Poppers” are recreational stimulants that are popular among some MSM communities and used directly as a sexual enhancement. Disinhibition and failure to use condoms during sex have been associated particularly with stimulant and alcohol use (Khan et al. 2009; Parry et al. 2009; Hagan et al. 2011; Qian et al. 2011). There is also a body of literature citing the nonspecific immune activation resulting from drug use, from antigenic stimulation from contaminants, and immunosuppressive effects of alcohol use (Barve et al. 2002; Cabral 2006; Hahn and Samet 2010). Such immunostimulation could increase risk of acquisition of HIV by activated immune cells, whereas immunosuppression might further aggravate the CD4+ cell depletions caused by HIV. Prevention efforts to reduce HIV risk among noninjection drug and alcohol users have shown mixed results (Strauss and Rindskopf 2009; Strauss et al. 2009; Crawford and Vlahov 2010).

RISK EXPOSURES: ADMINISTRATION OF BLOOD AND BLOOD PRODUCTS, AND IATROGENIC EXPOSURES

Early in the epidemic, HIV-contaminated blood and blood products were a major contributor to the high incidence of infection in the Western world. The first cases reported in 1982 were men with hemophilia (Centers for Disease Control 1982; Evatt et al. 1985). Many nations began to screen for risk based on personally reported risk characteristics (such as MSM or IDU), but this was an imperfect way to tag the at-risk blood donations. A few countries added a surrogate for HIV risk, such as hepatitis B antigen or antibody, which improved the sensitivity of the screening in the pre-HIV test period before 1985 (Busch et al. 1997; Jackson et al. 2003). As concentrated factor VIII was a notable contributor to risk, heat-treated products were introduced, although for more than a year, the old products were still marketed, despite the known risk. When the first commercially available HIV antibody test was licensed in 1985, blood banking practices changed radically in most high-income nations. Sadly, politics interfered with policy in some settings (e.g., France) or economic consideration delayed screening, such that thousands of persons were still being infected, even in richer nations, where delays in introducing HIV screening resulted in transmissions. Today in 2011, many countries like the United States use both antibody screening and antigen screening using nucleic acid tests. This is to detect those persons who might be in the period between infection and seropositivity. Given the high viral load in these infected pre-seroconverters, risk of transmission is very high. Antibody testing of the blood supply is cost-effective, although antigen testing with PCR of seronegative blood products is not (AuBuchon et al. 1997). The new generation antibody-antigen dual serology tests will surely lead to reconsideration of PCR testing, as more persons infected with HIV in the window period will now be detected with serology.

Sharing needles and/or syringes is an exceedingly efficient way to transmit HIV, and this is not merely a phenomenon of IDU. It is also seen in dysfunctional health care settings such as orphanages in Romania, and hospitals in Libya (Hersh et al. 1991a; Rosenthal 2006). It remains a global disgrace that health care workers still reuse injection equipment in some settings; even national vaccine programs have been implicated when syringes/needles have run short owing to logistical supply chain problems or owing to graft (persons redirected syringes and needles for personal gain, but reusing needles/syringes for vaccine administration). Hence, WHO and other organizations have taken a strong interest in single-use syringes to avoid reuse of needles in the health care setting (Kane et al. 1999; Simonsen et al. 1999; Ekwueme et al. 2002; Sikora et al. 2010).

RISK EXPOSURES: HETEROSEXUAL

Heterosexual HIV spread has been a reality in the HIV epidemic from the very beginning of the recognition of the epidemic in high-income nations, although far less prevalent than in Africa. In the early days of statistics dominated by MSM, and then by IDUs, it was psychologically tempting to think that heterosexuals would be spared, although no other STD or blood-borne pathogen is transmitted only among MSM and not via male-female contact. In fact, the proportion of reported HIV/AIDS cases has risen steadily in high-income countries since the start of the epidemic in the West (Burchell et al. 2008; Kramer et al. 2008; Adimora et al. 2009; Mercer et al. 2009; Toussova et al. 2009). Although expanding more slowly than in Africa or among MSM, the large population at risk results in a substantial proportion of the persons infected with HIV attributable to heterosexual contact, one-fifth to one-third of the epidemic cases in non-IDUs in most high-income countries (Malebranche 2008; Rothenberg 2009; Mah and Halperin 2010).

The magnitude of the heterosexual epidemic in the northern hemisphere and higher-income nations has not reached anywhere near the magnitude seen in southern Africa. There are many possible explanations, all of them speculative and hard to demonstrate definitively. Viral infectiousness may be higher with the C clade of virus prevalence in southern Africa than with the B clade most common in the Americas, Europe, and Australia (Novitsky et al. 2010). A second speculation is that host genetics differ in Africans than in Caucasians such that African host susceptibility is higher (Pereyra et al. 2010). A third idea is that sexual partner mixing rates are higher in Africa where absentee worker husbands and intergenerational sex both drive risky behavior (Konde-Lule et al. 1997; Pickering et al. 1997; Yirrell et al. 1998; Gregson et al. 2002; Ekanem et al. 2005; Latora et al. 2006; Hallett et al. 2007; Helleringer and Kohler 2007; Katz and Low-Beer 2008; Doherty 2011; Fritz et al. 2011; Steffenson et al. 2011). A fourth explanation is that African tribal and ethnic groups that do not ritually circumcise their men are at especially high risk of high HIV transmission. There is little scientific consensus to date as to the relative importance of these and other factors.

Male circumcision is powerfully associated with reduced risk for HIV acquisition in both epidemiologic and experimental studies (Bongaarts et al. 1989; Weiss et al. 2000; Auvert et al. 2005; Bailey et al. 2007; Gray et al. 2007; Sahasrabuddhe and Vermund 2007; Mills et al. 2008; Siegfried et al. 2009; Weiss et al. 2010). Protection was more than 50% in three independent clinical trials from South Africa, Kenya, and Uganda. Although American men are circumcised at high rates, European men are not, such that the dearth of a marked heterosexual epidemic in both North America and Europe suggests, at least, that circumcision status has not been a dominant factor in predicting heterosexual spread in the northern hemisphere.

RISK EXPOSURES: MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION

The steady increase of HIV among women in the West was the consequence of expanded transmission among MSM, some of whom were bisexual, and IDUs who were most often heterosexual and were sometimes women themselves. As the numbers of women with HIV infection rose, so too did the numbers of babies born who were exposed to HIV (Stringer and Vermund 1999). Fully one in four in North America and somewhat fewer (about one in eight) in Europe of exposed infants were infected in utero and intrapartum in the pre-ART era (Stringer and Vermund 1999). Viral load of the mother correlated with transmission risk. Breastfeeding was avoided early on in the epidemic once it was apparent that breast milk of an HIV-infected nursing mother could infect her infant. Once zidovudine (and then nevirapine) was demonstrated to be safe and effective in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT), monotherapy was instituted with tremendous impact, reducing transmission to the infant by half or more (Lindegren et al. 1999; Mofenson and McIntyre 2000; Mofenson 2003).

Without intervention, about 5% of infected mothers will be expected to transmit HIV in utero to the fetus, about 20% will transmit intrapartum, and about 15% will transmit through the breast milk, for an aggregate of 40% risk of infection to the infant (Mofenson and Fowler 1999). Prematurity increases this risk, as does high maternal viral load (VL), low maternal CD4+ cell count, and vaginal (vs. cesarean) delivery (Goldenberg et al. 2002; Fowler et al. 2007). Discovery of a risk factor does not necessarily translate directly into a remediable action. For example, although bacterial vaginosis is a risk factor for preterm birth, and preterm birth is a risk factor for HIV infection from mother to child, use of antibiotics during pregnancy to reduce bacterial vaginosis did not reduce either prematurity or HIV infection in African women in a clinical trial (HPTN 024), beyond nevirapine (NVP) alone (Goldenberg et al. 2006a,b; Taha et al. 2006).

Problems with drug resistance were noted in PMTCT, as with ART therapy in general (Fogel et al. 2011a,b). Happily, most ART was demonstrated to be tolerable and safe in pregnancy (efavirenz is an exception), and combination ART (cART) is now the rule for HIV-infected pregnant women in high-income countries. Pediatric HIV has ceased to be a major public health problem in higher-income countries as routine “opt-out” testing for all pregnant women maximizes case detection, and use of cART reduces transmission to a minimum, with replacement “formula” feeding (Jamieson et al. 2007; Committee on Pediatric AIDS 2008; Gazzard et al. 2008). In Africa, in contrast, much progress is needed, although our tools for program evaluation and breastfeeding management have improved (Stringer et al. 2005, 2008, 2010; Reithinger et al. 2007; Mofenson 2010). The impact of opt-out testing in pregnancy, high coverage with cART, and replacement feeding for infants is encouraging in high-income nations. The peak of 1700 reported cases of pediatric AIDS occurred in 1992; subsequently, cases have decreased to <50 new cases of AIDS annually (a >96% reduction) and <300 annual perinatal HIV transmissions in 2005; despite that, the number of HIV-infected women continues to rise (Fowler et al. 2010; Lansky et al. 2010). Given stability of HIV incidence and the frequency of pregnancy in HIV-infected women, the programs to prevent perinatal transmission must be maintained and access assured (Wade et al. 2004; Volmink et al. 2007; Peters et al. 2008; McDonald et al. 2009; Birkhead et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2010).

PREVENTION OF HIV IN HIGH-INCOME NATIONS

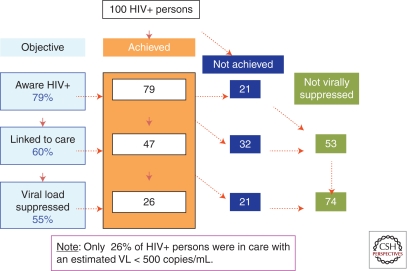

Other works in this collection discuss preexposure prophylaxis and behavioral change, and we discussion prevention only very briefly here. Behavior change remains a backbone of interventions in higher-income nations, although results have been somewhat disappointing as with Project EXPLORE/HIVNET 015 (Chesney et al. 2003; Koblin et al. 2003, 2004; Colfax et al. 2004, 2005; Salomon et al. 2009). Combination interventions are now being explored (Barrow et al. 2008; Corsi and Booth 2008; Buchbinder 2009; Rotheram-Borus et al. 2009; Burns et al. 2010; Cohen et al. 2010; Crawford and Vlahov 2010; DeGruttola et al. 2010; El-Bassel et al. 2010; Read 2010; Reynolds and Quinn 2010), as are behavioral approaches with a better base in evidence (Collins et al. 2006; Harshbarger et al. 2006; Lyles et al. 2006; Wingood and DiClemente 2006; Margaret Dolcini et al. 2010). One strategy has been a conspicuous failure, namely “abstinence only” education, discovered to be associated with higher pregnancy rates than more comprehensive approaches that also highlighted STD prevention with condom use (Ott and Santelli 2007; Kohler et al. 2008; Trenholm et al. 2008). It is thought that the more pragmatic sexual education approaches in Europe and Australia, with structural changes like widespread provision of condom dispensing machines in bathrooms, may explain why the heterosexual epidemic among heterosexuals has been lower than in the United States where comprehensive sex education and condom advertising and distribution have been comparatively curtailed (Dworkin and Ehrhardt 2007). Structural interventions and behavior interventions can support biomedical advances in PrEP (both oral and topical [microbicides]), cART for prevention by reducing viral load among infectious persons (Fig. 5). Multicomponent interventions show promise and must be studied (Vermund et al. 2010; Kurth et al. 2011).

Figure 5.

This is a model of how we estimate that only 26 of each 100 HIV-infected people in the United States are virally suppressed such that they would be expected to have a very slow disease progression and would be minimally infectious to others. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States, 2009 estimates of the proportion of HIV-infected persons in the United States who know their HIV-seropositive status (79%), the proportion of those persons who are linked to HIV care (60%), and the proportion of them who are virally suppressed (55%), this is a cascade model of the overall number of 100 HIV-infected persons who are currently immunologically suppressed (only 26). (From Burns et al. 2010.)

Summarized succinctly by one of the leading figures in the molecular characterization of HIV in the 1980s, Simon Wain-Hobson: “The problem of HIV evolution … is one of population genetics” (in conversation with ALB at the Institut Pasteur, August 1988).

Editors: Frederic D. Bushman, Gary J. Nabel, and Ronald Swanstrom

Additional Perspectives on HIV available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Abecasis AB, Lemey P, Vidal N, de Oliveira T, Peeters M, Camacho R, Shapiro B, Rambaut A, Vandamme AM 2007. Recombination confounds the early evolutionary history of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: Subtype G is a circulating recombinant form. J Virol 81: 8543–8551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aceijas C, Stimson GV, Hickman M, Rhodes T 2004. Global overview of injecting drug use and HIV infection among injecting drug users. AIDS 18: 2295–2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aceijas C, Hickman M, Donoghoe MC, Burrows D, Stuikyte R 2007. Access and coverage of needle and syringe programmes (NSP) in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Addiction 102: 1244–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Floris-Moore MA 2009. Ending the epidemic of heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans. Am J Prev Med 37: 468–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizon M, Wain-Hobson S, Montagnier L, Sonigo P 1986. Genetic variability of the AIDS virus: Nucleotide sequence analysis of two isolates from African patients. Cell 46: 63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JP, Rodrigo AG, Learn GH, Madan A, Delahunty C, Coon M, Girard M, Osmanov S, Hood L, Mullins JI 2000. Testing the hypothesis of a recombinant origin of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype E. J Virol 74: 10752–10765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold C, Barlow KL, Parry JV, Clewley JP 1995. At least five HIV-1 sequence subtypes (A, B, C, D, A/E) occur in England. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 11: 427–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AuBuchon JP, Birkmeyer JD, Busch MP 1997. Cost-effectiveness of expanded human immunodeficiency virus-testing protocols for donated blood. Transfusion 37: 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A 2005. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 trial. PLoS Med 2: e298 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC 2010. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: Systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. Int J Epidemiol 39: 1048–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, Williams CF, Campbell RT, Ndinya-Achola JO 2007. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 369: 643–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balfe P, Simmonds P, Ludlam CA, Bishop JO, Brown AJ 1990. Concurrent evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients infected from the same source: Rate of sequence change and low frequency of inactivating mutations. J Virol 64: 6221–6233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, Beyrer C 2007. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: A systematic review. PLoS Med 4: e339 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow RY, Berkel C, Brooks LC, Groseclose SL, Johnson DB, Valentine JA 2008. Traditional sexually transmitted disease prevention and control strategies: Tailoring for African American communities. Sex Transm Dis 35: S30–S39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RE, Huijgen Q, Taljaard J, Hoepelman AI 2010. Hepatitis B/C and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: An association between highly prevalent infectious diseases. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 14: e1024–e1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barve SS, Kelkar SV, Gobejishvilli L, Joshi-Barve S, McClain CJ 2002. Mechanisms of alcohol-mediated CD4+ T lymphocyte death: Relevance to HIV and HCV pathogenesis. Front Biosci 7: d1689–d1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkhead GS, Pulver WP, Warren BL, Hackel S, Rodriguez D, Smith L 2010. Acquiring human immunodeficiency virus during pregnancy and mother-to-child transmission in New York: 2002–2006. Obstet Gynecol 115: 1247–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobashev GV, Zule WA Modeling the effect of high dead-space syringes on the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic among injecting drug users. 2010. Addiction 105: 1439–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobkov A, Cheingsong-Popov R, Garaev M, Rzhaninova A, Kaleebu P, Beddows S, Bachmann MH, Mullins JI, Louwagie J, Janssens W, et al. 1994. Identification of an env G subtype and heterogeneity of HIV-1 strains in the Russian Federation and Belarus. AIDS 8: 1649–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobkov A, Cheingsong-Popov R, Selimova L, Ladnaya N, Kazennova E, Kravchenko A, Fedotov E, Saukhat S, Zverev S, Pokrovsky V, et al. 1997. An HIV type 1 epidemic among injecting drug users in the former Soviet Union caused by a homogeneous subtype A strain. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 13: 1195–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobkov A, Kazennova E, Khanina T, Bobkova M, Selimova L, Kravchenko A, Pokrovsky V, Weber J 2001. An HIV type 1 subtype A strain of low genetic diversity continues to spread among injecting drug users in Russia: Study of the new local outbreaks in Moscow and Irkutsk. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 17: 257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobkov AF, Kazennova EV, Sukhanova AL, Bobkova MR, Pokrovsky VV, Zeman VV, Kovtunenko NG, Erasilova IB 2004. An HIV type 1 subtype A outbreak among injecting drug users in Kazakhstan. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 20: 1134–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrova N, Rughnikov U, Neifeld E, Rhodes T, Alcorn R, Kirichenko S, Power R 2008. Challenges in providing drug user treatment services in Russia: Providers' views. Subst Use Misuse 43: 1770–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boily MC, Baggaley RF, Wang L, Masse B, White RG, Hayes RJ, Alary M 2009. Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis 9: 118–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J, Reining P, Way P, Conant F 1989. The relationship between male circumcision and HIV infection in African populations. AIDS 3: 373–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Kwiatkowski CF, Brewster JT, Sinitsyna L, Dvoryak S 2006. Predictors of HIV sero-status among drug injectors at three Ukraine sites. AIDS 20: 2217–2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Lehman WE, Kwiatkowski CF, Brewster JT, Sinitsyna L, Dvoryak S 2008. Stimulant injectors in Ukraine: The next wave of the epidemic? AIDS Behav 12: 652–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenchley JM, Douek DC 2008. HIV infection and the gastrointestinal immune system. Mucosal Immunol 1: 23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner BG, Roger M, Moisi DD, Oliveira M, Hardy I, Turgel R, Charest H, Routy JP, Wainberg MA 2008. Transmission networks of drug resistance acquired in primary/early stage HIV infection. AIDS 22: 2509–2515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder S 2009. The epidemiology of new HIV infections and interventions to limit HIV transmission. Top HIV Med 17: 37–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchell AN, Calzavara LM, Orekhovsky V, Ladnaya NN 2008. Characterization of an emerging heterosexual HIV epidemic in Russia. Sex Transm Dis 35: 807–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DN, Dieffenbach CW, Vermund SH 2010. Rethinking prevention of HIV type 1 infection. Clin Infect Dis 51: 725–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows D 1998. Injecting equipment provision in Australia: The state of play. Subst Use Misuse 33: 1113–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch MP, Dodd RY, Lackritz EM, AuBuchon JP, Birkmeyer JD, Petersen LR 1997. Value and cost-effectiveness of screening blood donors for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen as a way of detecting window-phase human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections. The HIV Blood Donor Study Group. Transfusion 37: 1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral GA 2006. Drugs of abuse, immune modulation, and AIDS. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 1: 280–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane P, Chrystie I, Dunn D, Evans B, Geretti AM, Green H, Phillips A, Pillay D, Porter K, Pozniak A, et al. 2005. Time trends in primary resistance to HIV drugs in the United Kingdom: Multicentre observational study. BMJ 331: 1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Carrington M, Alter G 2011. Innate immune control of HIV disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a007070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control 1981. Kaposi's sarcoma and Pneumocystis pneumonia among homosexual men—New York City and California. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 30: 305–308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control 1982. Update on acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 31: 507–508, 513–504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaix ML, Descamps D, Wirden M, Bocket L, Delaugerre C, Tamalet C, Schneider V, Izopet J, Masquelier B, Rouzioux C, et al. 2009. Stable frequency of HIV-1 transmitted drug resistance in patients at the time of primary infection over 1996–2006 in France. AIDS 23: 717–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Koblin BA, Barresi PJ, Husnik MJ, Celum CL, Colfax G, Mayer K, McKirnan D, Judson FN, Huang Y, et al. 2003. An individually tailored intervention for HIV prevention: Baseline data from the EXPLORE Study. Am J Public Health 93: 933–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Gay CL, Busch MP, Hecht FM 2010. The detection of acute HIV infection. J Infect Dis 202 Suppl 2: S270–S277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Haynes BF, McMichael AJ, Shaw GM 2011. Medical Progress: Acute HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 364: 1943–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Celum C, Chesney M, Huang Y, Mayer K, et al. 2004. Substance use and sexual risk: A participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol 159: 1002–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Coates TJ, Husnik MJ, Huang Y, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Chesney M, Vittinghoff E 2005. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of San Francisco men who have sex with men. J Urban Health 82: 62–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C, Harshbarger C, Sawyer R, Hamdallah M 2006. The diffusion of effective behavioral interventions project: Development, implementation, and lessons learned. AIDS Educ Prev 18: 5–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Pediatric AIDS 2008. HIV testing and prophylaxis to prevent mother-to-child transmission in the United States. Pediatrics 122: 1127–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi KF, Booth RE 2008. HIV sex risk behaviors among heterosexual methamphetamine users: Literature review from 2000 to present. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 1: 292–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho RA, van Griensven GJ, Moss A 1989. Effects of preventive efforts among homosexual men. AIDS 3 Suppl 1: S53–S56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall KA, Vasco DA, Posada D, Imamichi H 1999. Advances in understanding the evolution of HIV. AIDS 13 Suppl A: S39–S47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford ND, Vlahov D 2010. Progress in HIV reduction and prevention among injection and noninjection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 55 Suppl 2: S84–S87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandekar S 2007. Pathogenesis of HIV in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 4: 10–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cock KM, Brun-Vezinet F 1989. Epidemiology of HIV-2 infection. AIDS 3 Suppl 1: S89–S95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGruttola V, Smith DM, Little SJ, Miller V 2010. Developing and evaluating comprehensive HIV infection control strategies: Issues and challenges. Clin Infect Dis 50 Suppl 3: S102–S107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehne KL, Khodakevich L, Hamers FF, Schwartlander B 1999. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in eastern Europe: Recent patterns and trends and their implications for policy-making. AIDS 13: 741–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC 2000. Research, politics, and needle exchange. Am J Public Health 90: 1392–1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira T, Pillay D, Gifford RJ 2010. The HIV-1 subtype C epidemic in South America is linked to the United Kingdom. PLoS One 5: e9311 10.1371/journal.pone.0009311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ronde A, Schuurman R, Goudsmit J, van den Hoek A, Boucher C 1996. First case of new infection with zidovudine-resistant HIV-1 among prospectively studied intravenous drug users and homosexual men in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. AIDS 10: 231–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo G 2008. Update on classic Kaposi sarcoma therapy: New look at an old disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 68: 242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty IA 2011. Sexual networks and sexually transmitted infections: Innovations and findings. Curr Opin Infect Dis 24: 70–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing M, Riess TH, Vernon K, Mulia N, Hollinquest M, McKnight C, Jarlais DC, Edlin BR 2005. What's community got to do with it? Implementation models of syringe exchange programs. AIDS Educ Prev 17: 68–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker E, Lurie P, Wodak A, Alcabes P 1998. Measuring harm reduction: The effects of needle and syringe exchange programs and methadone maintenance on the ecology of HIV. AIDS 12 Suppl A: S217–S230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Rambaut A 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol 7: 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA 2007. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: Critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Am J Public Health 97: 13–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyre DM, Fernando LP, Holland PV 2011. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV transfusion-transmitted infections in the 21st century. Vox Sang 100: 92–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekanem EE, Afolabi BM, Nuga AO, Adebajo SB 2005. Sexual behaviour, HIV-related knowledge and condom use by intra-city commercial bus drivers and motor park attendants in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 9: 78–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwueme DU, Weniger BG, Chen RT 2002. Model-based estimates of risks of disease transmission and economic costs of seven injection devices in sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ 80: 859–870 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, Hunt T, Remien RH 2010. Couple-based HIV prevention in the United States: Advantages, gaps, and future directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 55 Suppl 2: S98–S101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elovich R, Drucker E 2008. On drug treatment and social control: Russian narcology's great leap backwards. Harm Reduct J 5: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr WM, Mayer KH, Hodder SL 2010. AIDS in America—Forgotten but not gone. N Engl J Med 362: 967–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evatt BL, Gomperts ED, McDougal JS, Ramsey RB 1985. Coincidental appearance of LAV/HTLV-III antibodies in hemophiliacs and the onset of the AIDS epidemic. N Engl J Med 312: 483–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Rehm J, Kirst M, Casas M, Hall W, Krausz M, Metrebian N, Reggers J, Uchtenhagen A, van den Brink W, et al. 2002. Heroin-assisted treatment as a response to the public health problem of opiate dependence. Eur J Public Health 12: 228–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel J, Hoover DR, Sun J, Mofenson LM, Fowler MG, Taylor AW, Kumwenda N, Taha TE, Eshleman SH 2011a. Analysis of nevirapine resistance in HIV-infected infants who received extended nevirapine or nevirapine/zidovudine prophylaxis. AIDS 25: 911–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel J, Li Q, Taha TE, Hoover DR, Kumwenda NI, Mofenson LM, Kumwenda JJ, Fowler MG, Thigpen MC, Eshleman SH 2011b. Initiation of antiretroviral treatment in women after delivery can induce multiclass drug resistance in breastfeeding HIV-infected infants. Clin Infect Dis 52: 1069–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler MG, Lampe MA, Jamieson DJ, Kourtis AP, Rogers MF 2007. Reducing the risk of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus transmission: Past successes, current progress and challenges, and future directions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197: S3–S9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler MG, Gable AR, Lampe MA, Etima M, Owor M 2010. Perinatal HIV and its prevention: Progress toward an HIV-free generation. Clin Perinatol 37: 699–719, vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Castro H, Kaye S, McClure M, Weber JN, Fidler S 2010. Epidemiology of non-B clade forms of HIV-1 in men who have sex with men in the UK. AIDS 24: 2397–2401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz K, McFarland W, Wyrod R, Chasakara C, Makumbe K, Chirowodza A, Mashoko C, Kellogg T, Woelk G 2011. Evaluation of a peer network-based sexual risk reduction intervention for men in beer halls in Zimbabwe: Results from a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 10.1007/s10461-011-9922-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SD, Nijhuis M, Schuurman R, Boucher CA, Brown AJ 2000. Evolution of lamivudine resistance in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals: The relative roles of drift and selection. J Virol 74: 6262–6268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SD, Wrin T, Smith DM, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Liu Y, Paxinos E, Chappey C, Galovich J, Beauchaine J, Petropoulos CJ, et al. 2005. Neutralizing antibody responses drive the evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope during recent HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 18514–18519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lerma JG, Otten RA, Qari SH, Jackson E, Cong ME, Masciotra S, Luo W, Kim C, Adams DR, Monsour M, et al. 2008. Prevention of rectal SHIV transmission in macaques by daily or intermittent prophylaxis with emtricitabine and tenofovir. PLoS Med 5: e28 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzard B, Clumeck N, d'Arminio Monforte A, Lundgren JD 2008. Indicator disease-guided testing for HIV—The next step for Europe? HIV Med 9 Suppl 2: 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MT, Rambaut A, Wlasiuk G, Spira TJ, Pitchenik AE, Worobey M 2007. The emergence of HIV/AIDS in the Americas and beyond. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 18566–18570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Stringer JS, Sinkala M, Vermund SH 2002. Perinatal HIV transmission: Developing country considerations. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 12: 149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Mudenda V, Read JS, Brown ER, Sinkala M, Kamiza S, Martinson F, Kaaya E, Hoffman I, Fawzi W, et al. 2006a. HPTN 024 study: Histologic chorioamnionitis, antibiotics and adverse infant outcomes in a predominantly HIV-1-infected African population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 195: 1065–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Mwatha A, Read JS, Adeniyi-Jones S, Sinkala M, Msmanga G, Martinson F, Hoffman I, Fawzi W, Valentine M, et al. 2006b. The HPTN 024 Study: The efficacy of antibiotics to prevent chorioamnionitis and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194: 650–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb MS, Schroff R, Schanker HM, Weisman JD, Fan PT, Wolf RA, Saxon A 1981. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and mucosal candidiasis in previously healthy homosexual men: Evidence of a new acquired cellular immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med 305: 1425–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, Goicochea P, Casapia M, Guanira-Carranza JV, Ramirez-Cardich ME, et al. 2010. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 363: 2587–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, Kiwanuka N, Moulton LH, Chaudhary MA, Chen MZ, et al. 2007. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: A randomised trial. Lancet 369: 657–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, Mason PR, Zhuwau T, Carael M, Chandiwana SK, Anderson RM 2002. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet 359: 1896–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan H, Perlman DC, Des Jarlais DC 2011. Sexual risk and HIV infection among drug users in New York City: A pilot study. Subst Use Misuse 46: 201–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Samet JH 2010. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: Weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 7: 226–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett TB, Gregson S, Lewis JJ, Lopman BA, Garnett GP 2007. Behaviour change in generalised HIV epidemics: impact of reducing cross-generational sex and delaying age at sexual debut. Sex Transm Infect 83 Suppl 1: i50–i54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers FF, Batter V, Downs AM, Alix J, Cazein F, Brunet JB 1997. The HIV epidemic associated with injecting drug use in Europe: Geographic and time trends. AIDS 11: 1365–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao C, Yan H, Yang H, Huan X, Guan W, Xu X, Zhang M, Tang W, Wang N, Gu J, et al. 2011. The incidence of syphilis, HIV and HCV and associated factors in a cohort of men who have sex with men in Nanjing, China. Sex Transm Infect 87: 199–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harshbarger C, Simmons G, Coelho H, Sloop K, Collins C 2006. An empirical assessment of implementation, adaptation, and tailoring: The evaluation of CDC's National Diffusion of VOICES/VOCES. AIDS Educ Prev 18: 184–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer R 2008. Community coverage and HIV prevention: Assessing metrics for estimating HIV incidence through syringe exchange. Int J Drug Policy 19 Suppl 1: S65–S73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleringer S, Kohler HP 2007. Sexual network structure and the spread of HIV in Africa: Evidence from Likoma Island, Malawi. AIDS 21: 2323–2332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh BS, Popovici F, Apetrei RC, Zolotusca L, Beldescu N, Calomfirescu A, Jezek Z, Oxtoby MJ, Gromyko A, Heymann DL 1991a. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Romania. Lancet 338: 645–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh BS, Popovici F, Zolotusca L, Beldescu N, Oxtoby MJ, Gayle HD 1991b. The epidemiology of HIV and AIDS in Romania. AIDS 5 Suppl 2: S87–S92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EC, Zhang LQ, Robertson P, Cleland A, Harvey E, Simmonds P, Leigh Brown AJ 1995. The molecular epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Edinburgh. J Infect Dis 171: 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hue S, Pillay D, Clewley JP, Pybus OG 2005. Genetic analysis reveals the complex structure of HIV-1 transmission within defined risk groups. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 4425–4429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GJ, Fearnhill E, Dunn D, Lycett SJ, Rambaut A, Leigh Brown AJ 2009. Molecular phylodynamics of the heterosexual HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000590 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson BR, Busch MP, Stramer SL, AuBuchon JP 2003. The cost-effectiveness of NAT for HIV, HCV, and HBV in whole-blood donations. Transfusion 43: 721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson DJ, Clark J, Kourtis AP, Taylor AW, Lampe MA, Fowler MG, Mofenson LM 2007. Recommendations for human immunodeficiency virus screening, prophylaxis, and treatment for pregnant women in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197: S26–S32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CV, Mimiaga MJ, Bradford J 2008. Health care issues among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) populations in the United States: Introduction. J Homosex 54: 213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JH, Handcock MS 2003. An assessment of preferential attachment as a mechanism for human sexual network formation. Proc Biol Sci 270: 1123–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Pickering L, Sumnall H, McVeigh J, Bellis MA 2010. Optimal provision of needle and syringe programmes for injecting drug users: A systematic review. Int J Drug Policy 21: 335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalish ML, Robbins KE, Pieniazek D, Schaefer A, Nzilambi N, Quinn TC, St Louis ME, Youngpairoj AS, Phillips J, Jaffe HW, et al. 2004. Recombinant viruses and early global HIV-1 epidemic. Emerg Infect Dis 10: 1227–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane A, Lloyd J, Zaffran M, Simonsen L, Kane M 1999. Transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency viruses through unsafe injections in the developing world: Model-based regional estimates. Bull World Health Organ 77: 801–807 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz I, Low-Beer D 2008. Why has HIV stabilized in South Africa, yet not declined further? Age and sexual behavior patterns among youth. Sex Transm Dis 35: 837–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling MJ, Eames KT 2005. Networks and epidemic models. J R Soc Interface 2: 295–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MR, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Mateu-Gelabert P, Krauss B, Aral SO, Friedman SR 2009. Social and behavioral correlates of sexually transmitted infection- and HIV-discordant sexual partnerships in Bushwick, Brooklyn, New York. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 51: 470–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]