Abstract

Ulcerative inflammation of the cornea occurs in the perilimbal cornea, and is associated with autoimmune collagen vascular and arthritic diseases. Rheumatoid arthritis is the most frequent underlying disease. The tendency for peripheral location is due to the distinct morphologic and immunologic characteristics of the limbal conjunctiva, which provides access for circulating immune complexes to the peripheral cornea via the capillary network. Deposition of immune complexes in the terminal ends of limbal vessels initiates immune-mediated vasculitis, and causes inflammatory cell and protein leakage due to vessel wall damage. Development of peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with systemic disease may represent worsening of a potentially life-threatening disease. Accompanying scleritis, particularly the necrotizing form, is usually observed in severe cases, which may result in corneal perforation and loss of vision. Although first-line treatment with systemic corticosteroids is indicated for acute phases, immunosuppressive and cytotoxic agents are required for treatment of peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with multisystem disorders. Recently, infliximab, a chimeric antibody against proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha, was reported to be effective in cases refractory to conventional immunomodulatory therapy. The potential side effects of these therapies require close follow-up and regular laboratory surveillance.

Keywords: autoimmune disease, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, treatment, tumor necrosis factor-alpha

Introduction

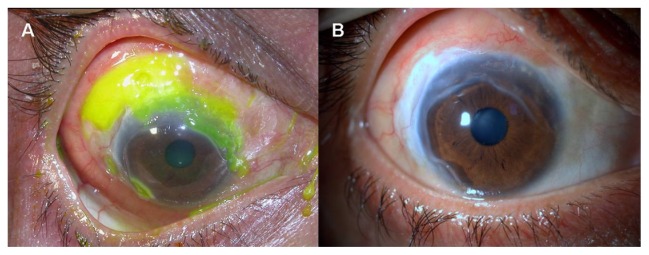

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is a form of unilateral crescent-shaped stromal inflammation, which involves the juxtalimbal cornea and is characterized by sectorial thinning of the affected area. It is always associated with an overlying epithelial defect and progressive loss of the corneal stroma (Figure 1A). PUK is often contiguous with adjacent conjunctival, episcleral, and scleral inflammation. The presence of such adjacent tissue inflammation aggravates the course of PUK and causes potentially serious complications, such as perforation of the cornea.1–3 PUK-associated complications might be prevented with timely diagnosis, detection of the underlying systemic inflammatory disease, and proper treatment.

Figure 1.

(A) Slit lamp photograph of a patient with juvenile RA demonstrates sectorial corneal thinning and overlying epithelial defect, (B) The clinical appearance following corneal transplantation for tectonic purpose.

PUK can be associated with numerous systemic diseases and may precede the systemic disease, but there is a tendency for it to occur following observation of systemic manifestations. Tauber et al4 reported that PUK was the initial manifestation of collagen vascular disease in 50% of cases. Patients with collagen vascular disease-related PUK often require aggressive systemic treatment to curtail the relentless progression of corneal destruction.3,5 This review summarizes the clinical features, pathogenesis, and diseases associated with noninfectious PUK, as well as recently developed treatment options.

Etiologic features

PUK may be associated with various ocular and systemic infectious and noninfectious diseases. In addition to microbial organisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and chlamydia, systemic connective tissue, vasculitic autoimmune diseases, and dermatologic disorders can cause PUK.2,5–7 Marginal keratitis, also referred to as catarrhal infiltrates, and phlyctenular corneal disease are noninfectious inflammatory processes of the peripheral cornea. Although clinically distinct entities, they share a common pathophysiologic mechanism; they develop as a result of hypersensitivity reaction to toxins produced by bacteria usually associated with longstanding staphylococcal blepharoconjunctivitis.3 Phlyctenules are a more severe reaction than catarrhal infiltrates; subepithelial inflammatory nodules that first appear in the limbus usually undergo necrosis, forming an ulcer. Although earlier studies reported that there was a strong association between tuberculosis and PUK, more recent studies indicate that staphylococcal disease is a more common cause.3,6

The most common disorders associated with PUK are systemic collagen vascular diseases, of which rheumatoid arthritis is the most common, accounting for 34% of noninfectious PUK cases. Approximately 50% of all noninfectious PUK cases have an associated collagen vascular disease.4 Other than rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, classic polyarteritis nodosa and its variants, microscopic polyangiitis or Churg–Strauss syndrome can be the cause (Table 1). The corneal signs are similar in all collagen vascular inflammatory diseases. Although PUK may be the presenting sign of these potentially life-threatening systemic diseases, it may develop as a complication of scleritis, especially the necrotizing form,4,8 so precise anamnesis, systemic workup, and tissue biopsy are required for diagnosis (Figure 2). Foster et al reported that the mortality rate in untreated rheumatoid arthritis patients with PUK/necrotizing scleritis is approximately 50% over a 10-year period.9

Table 1.

| Ocular | Causes |

|---|---|

| Bacterial | Staphylococcus, Streptococcus Gonococcus, Moraxella, Hemophilus |

| Viral | Herpes simplex, herpes zoster |

| Amebic | Acanthamoeba |

| Fungal | |

| Traumatic | Chemical, thermal, radiation burn |

| Abnormalities of eyelids or lashes | Entropion, ectropion, cicatricial, exposure, trichiasis, lagophthalmos, incomplete blink |

| Local, autoimmune | Mooren’s ulcer Allograft reaction |

| Neurologic | Neurotrophic keratitis |

| Systemic | |

| Autoimmune vasculitic diseases | Rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa and variants, Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Dermatological disorders | Acne rosacea, cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens–Johnson syndrome |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | |

| Malignancy | |

| Bacterial | Tuberculosis, syphilis, gonorrhea, borreliosis, bacillary dysentery |

| Viral | Varicella zoster, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, hepatitis |

Figure 2.

PUK with adjacent necrotizing scleritis in a patient with Wegener’s granulomatosis, stained with fluorescein.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathophysiologic mechanism of PUK remains unclear, but the same pathogenic mechanism is thought to occur in all forms of PUK. Research suggest that both humoral-mediated and cell-mediated autoimmune processes are involved. Reactions to corneal antigens, circulating immune complex deposition, and hypersensitivity reactions to exogenous antigens are other mechanisms implicated in the pathogenesis of PUK.8,10–12

A hypersensitivity reaction to exogenous antigens induces catarrhal infiltrate, marginal ulcer, and phyctenule development, and has a more favorable prognosis than immune disease-related PUK. The peripheral cornea has distinct morphologic and immunologic characteristics that predispose it to immune inflammation. Unlike the avascular central cornea, the limbus and the peripheral cornea receive a portion of their nutrient supply from the capillary arcades, which extend only approximately 0.5 mm into the clear cornea. The vascular architecture of the limbus is suitable for accumulation of IgM, the first component of complement cascade C1, and other high molecular weight molecules and immune complexes in the limbus and corneal periphery.13–15 Deposition of immune complexes activates the classical pathway of the complement system, which in turn results in chemotaxis of inflammatory cells, in particular, neutrophils and macrophages in the peripheral cornea. These cells can release collagenases and other proteases that destroy the corneal stroma.3,16,17 Additionally, release of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 from the inflammatory cells enables stromal keratocytes to produce matrix metalloproteinase-1 and matrix metalloproteinase-2, which can accelerate the matrix destruction process.10

Subconjunctival lymphatics and limbal capillaries in the peripheral cornea provide access to the afferent arm of the immune system, which facilitates immunologically driven corneal inflammation. Moreover, the limbus and conjunctiva that are adjacent to PUK have been hypothesized to serve as a major reservoir for various effector cells of the immune system and proinflammatory cytokines, thereby playing a critical role in the immunopathogenesis of PUK.8,18–23

Clinical features

Various ocular manifestations of collagen vascular diseases are present in addition to PUK; keratoconjunctivitis sicca is the most common, and is clinically evident in 15%–25% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.24 The main symptoms for patients are ocular redness, pain, tearing, photophobia, and decreased vision secondary to induced astigmatism or corneal opacity in advanced cases. Biomicroscopic examination shows opacity due to cellular infiltrates within the stroma adjacent to the limbus. Later, crescent-shaped corneal ulcers develop with breakdown of the overlying epithelium. Varying degrees of vascularization and corneal thinning due to tissue loss in the underlying stroma occur as well (Figure 3). The depth of peripheral corneal thinning is variable; in severe cases, tissue loss may progress to perforation, with or without trauma. Adjacent conjunctival, episcleral, and scleral inflammation are also generally apparent. Adjacent scleritis is almost always present in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis.4,16,24

Figure 3.

Crescent-shaped peripheral corneal thinning with superficial vascularization and infiltration, which is specific for PUK.

It was reported in a review of 47 PUK patients that the incidence of nodular or necrotizing scleritis was 64%.4 Sainz de la Maza et al25 reported that 14% of patients with scleritis of all types had PUK versus 41% of patients with necrotizing scleritis. The frequency of PUK was reported to be 7.4% in a recent study that included 500 patients with scleritis and 85 patients with episcleritis. Similar to other studies, it was reported that PUK occurred statistically more frequently in patients with scleritis than in patients with episcleritis and that the presence of necrotizing scleritis increases the probability of PUK.26 Most corneal findings resolve following appropriate treatment and resolution of accompanying scleritis, with resultant scarring and neovascularization. It is thought that surgical trauma triggers immune complex-mediated vasculitis in patients with collagen vascular disease.25

Differential diagnosis

Some clinical entities, such as Mooren’s ulcer and Terrien’s marginal degeneration, share similar clinical features with PUK. All are characterized by varying degrees of progressive peripheral corneal thinning and superficial vascularization. Unlike PUK and Mooren’s ulcer, inflammation and epithelial defects are not hallmarks of Terrien’s marginal degeneration. Demarcation from the central cornea with a gray line is characteristic of Terrien’s marginal degeneration.27,28

Mooren’s ulcer is a form of PUK which is not associated with scleritis. It is idiopathic and occurs at any age, but the vast majority of patients are aged >40 years. Mooren’s ulcer develops in the absence of any systemic disease that can cause PUK. It begins in the peripheral cornea, and spreads circumferentially and centrally. The main difference from PUK is the severity of pain, which is more intolerable in Mooren’s ulcer. It may involve one or both eyes. The central border exhibits an overhanging edge and, unlike in PUK, the sclera is rarely involved.28–30

Although marginal keratitis and phlyctenular ulcers are similar in clinical appearance to PUK, their signs are less severe and self-limited. During the ulcerative stages it may be difficult to differentiate infectious corneal ulcers, herpes simplex virus keratitis, and phlyctenular and catarrhal ulcers from PUK. In contrast with PUK and phlyctenules, catarrhal ulcers leave a clear space between the ulcer and the limbus (Figure 4). Herpetic infections begin with an epithelial defect, followed by an infiltrate, which is the reverse order of that observed in marginal keratitis. Additionally, marginal keratitis responds rapidly to topical treatment, whereas PUK might worsen due to the lack of targeted systemic treatment. Clinicians must be able to differentiate these entities from acute infections and PUK.3,24 All patients who present with peripheral keratitis and ulceration must undergo a detailed personal and family history, with specific attention given to collagen vascular and other autoimmune diseases. Complete ocular and systemic examinations are important for determining the etiology. Inflammatory and noninflammatory conditions or infection should be considered, in addition to postinfectious disorders, abnormalities of the eyelids or lashes, neurologic and dermatologic conditions, and malignancies.10,16,25 Specific systemic findings may lead ophthalmologists to suspect certain types of associated diseases. Laboratory investigations conducted according to the findings include complete and differential blood cell counts, platelet count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, chest X-ray examination, and liver enzymes. Additional testing should be performed based on the results of these tests. Infectious etiologies should be excluded via appropriate cultures, because microbial keratitis can rapidly progress and is usually responsive to antibiotic therapy.1,8,31–33

Figure 4.

Slit lamp appearance of marginal keratitis with characteristic features (lesion parallel to limbus and seperated from the limbus by clear cornea).

Treatment

Treatment of PUK is based on the severity of findings within the cornea and the extent of extraocular disease. Treatments initiated for systemic autoimmune disease have beneficial effects on ocular manifestations. Regardless of the management of corneal disease, results will be disappointing unless aggressive treatment of the systemic disease is taken into consideration. The current treatment strategy for PUK with underlying systemic disease is systemic corticosteroids plus a cytotoxic agent during the acute phase of the disease. The exact cytotoxic agent may differ according to the underlying systemic disease.5,6,24,27

The goal of medical treatment for ocular disease is to reduce inflammation, promote epithelial healing, and minimize stromal loss. Despite improvements in new immunomodulatory and biologic agents, the outcome of PUK depends primarily on the accompanying disease, and timely diagnosis and treatment. In this respect, in addition to surgery, the local and systemic stepladder approach should be considered.

Local treatment

Local bacterial and viral infections that cause PUK are usually relieved with local targeted treatment. Initially ophthalmologists should be sure to lubricate the ocular surface with preservative-free lubricating agents, because a significant number of patients with PUK also suffer from tear film abnormalities.6 These agents are also helpful for removing or diluting harmful inflammatory proteins and mediators on the ocular surface. In patients with marginal ulcerative keratitis without an accompanying systemic disease, eyelid hygiene and topical corticosteroids can be used and tapered according to the clinical response. A topical antibiotic is recommended before corticosteroid use.3,6,24

Collagenase inhibitors or collagenase synthetase inhibitors, such as topical l% medroxyprogesterone and topical 20% acetylcysteine, may be of limited benefit in reducing additional stromal ulceration. Topical corticosteroids are not appropriate in patients with related systemic disease, because these drugs inhibit new collagen production and thereby increase the risk of perforation.1,4,16,24 Oral tetracycline derivatives may provide additional benefit in preventing further stromal loss by decreasing protease activity.34–36

Systemic immune modulation

Glucocorticoids

Systemic corticosteroids are the traditional first-line therapy for acute phases of PUK, but alone are often unable to inhibit disease progression or overcome the autoimmune disease. The usual starting dose is 1 mg/kg/day (maximum 60 mg/day), followed by a tapering schedule based on clinical response. Pulsed methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 consecutive days, followed by oral therapy, might be initiated in patients with imminent danger of vision loss.1,4,9,24

Immunosuppressive drugs or biologic agents are administered with or without glucocorticoids in cases refractory to glucocorticoids and when glucocorticoid-associated adverse effects become an issue. Common complications of systemic corticosteroids, such as osteoporosis, exacerbation of hypertension and diabetes, electrolyte imbalance, and gastrointestinal bleeding, may be avoided with initiation of immunosuppressive drugs.1,5,8,10,16 Although steroids have a profoundly positive effect on ocular and systemic symptoms, they fail to reduce the high mortality rate in patients with rheumatoid vasculitis, as reported by Foster et al.9 Therefore, the addition of cytotoxic chemotherapy comes up to successfully treat these patients.

Immunosuppressives/immunomodulators

To date, there is no universal agreement about which immunosuppressant or modulator should be used for specific cases. A review by Jabs et al included an extensive overview of the recommended options, doses, and applications for immunosuppressive agents.37 Immunosuppressives available for use in these cases include antimetabolites, alkylating agents, T cell inhibitors, and biologic agents. Methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and leflunomide are suitable antimetabolite agents. Methotrexate and azathioprine are the two most commonly used antimetabolites in cases unresponsive to oral corticosteroids and with recalcitrant rheumatoid PUK. Oral methotrexate in doses ranging from 7.5–25 mg/week and azathioprine 1.0–2.5 mg/kg/day have been reported to be effective.9,33,37,38 Recent studies indicated better inflammatory control and fewer side effects with mycophenolate mofetil (1.0 g twice daily) than with methotrexate or azathioprine.37,39–41 Moreover, clinical reports suggest that leflunomide might be efficacious in the treatment of ocular inflammation.42

The alkylating agents, cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil, are suggested for use in severe progressive cases and in cases unresponsive to methotrexate or other antimetabolites. In a retrospective case series, Messmer and Foster reported that cytotoxic immunosuppressive agents are highly effective in patients resistant to systemic corticosteroids.43 Cyclophosphamide was reported to be the most effective agent in their series; however, methotrexate was reported to be very effective with less potential toxicity and was suggested as a potential first choice for immunosuppression (Figure 5A and B). Cyclophosphamide may be administered orally at doses of 1–2 m/kg/day or as pulsed intravenous therapy every 3–4 weeks under rheumatologic or internal medicine guidance.24,37,38,43–45

Figure 5.

The slit-lamp appearance of PUK contiguous with scleritis, stained with fluorescein. (A) Pre-treatment with cyclophosphamide, (B) Post-treatment with cyclophosphamide.

Data on the use of cyclosporin A in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and severe inflammatory eye disease suggest that cyclosporin could be the initial immunosuppressant treatment of choice in idiopathic cases or in those not associated with systemic vasculitis, particularly if there are no serious concerns about nephrotoxicity.38,44,45 Cases associated with systemic vasculitis often require use of more potent immunosuppressives, including cytotoxic (eg, cyclophosphamide) or antimetabolite (eg, methotrexate) therapy.38,44,45

Biologic agents

Infliximab (Remicade®; Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc, Horsham, PA) was approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1999. Use of infliximab for ocular inflammation was first reported in 2001 for patients with panuveitis and rheumatoid arthritis-associated scleritis.46,47 It is currently indicated for treatment of connective tissue or vasculitic autoimmune diseases, and accompanying PUK, as well as other ocular inflammatory states, such as necrotizing scleritis and uveitis.2,48–50 It is a specific, chimeric monoclonal antibody against proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which stimulates production of the matrix metalloproteinases responsible for corneal stromal lysis in PUK. It binds both soluble and transmembrane TNF-α by blocking its receptor. Cells expressing transmembrane TNF-α bound to infliximab may also be susceptible to complement-mediated lysis, potentially increasing its anti-inflammatory effect.2,51

Dosing of infliximab varies from 3 mg/kg intravenously for rheumatoid arthritis to 5 mg/kg intravenously for Crohn’s disease, and is administered at weeks 0, 2, and 6, and then every 8 weeks for up to 18 months. Improvement usually occurs 1–2 weeks after the first infusion. Although the optimal frequency and dosing of infliximab for PUK and/or corneal perforation have not yet been established, a dosing regimen similar to that used for rheumatoid arthritis seems reasonable.2,50,52 The maintenance of remission must be weighed against potential adverse events, because the long-term efficacy and safety of biologics for use in ocular inflammation is unknown.

Before administering infliximab, opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis must be ruled out, in addition to absolute contraindications such as congestive heart failure. The reported side effects of long-term use include increased risk of opportunistic infections, anaphylaxis, diarrhea, cardiac failure, and resistance.53 More serious side effects, such as lymphoproliferative disorders, malignancy, hepatotoxicity, and endogenous endophthalmitis, have been reported. Moreover, increased risk of thrombosis was reported, ranging from branch retinal vein occlusion to myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolus;54–56 therefore, special care must be taken when using infliximab and other biologic agents.

Other biologics, including etanercept (Enbrel®; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA/Wyeth, Philadelphia, PA) and rituximab (Rituxan®; Biogen Idec, Cambridge, MA and Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), have been used for the treatment of PUK. Etanercept is a human recombinant dimeric fusion protein that mimics the effects of naturally occurring soluble TNF-α receptors. It has been used for the treatment of refractory uveitis, necrotizing scleritis, and keratitis, but is less efficacious than infliximab for the treatment of ocular inflammation. This may be due to the ability of infliximab to bind to membrane-bound TNF-α, in addition to free-floating cytokines. Recently, rituximab, a chimeric antibody against CD20-α, which depletes B lymphocytes, has been used to treat refractory PUK associated with Wegener granulomatosis, in addition to recalcitrant scleritis and anterior uveitis.2,31,57,58

Surgical management

Tectonic procedures are required to maintain the integrity of the globe (Figure 1B). Options include the use of a tissue adhesive, bandage contact lens, lamellar graft, tectonic corneal grafting, and amniotic membrane transplantation. Use of tissue adhesives is a consideration in patients with impending perforation and perforations <2.0 mm, and is followed by application of a bandage contact lens to prevent discomfort.16 Corneal grafting should be performed following appropriate immunosuppression, but nevertheless the outcome is disappointing. Maneo et al reported that keratoplasty performed for ulcerative keratitis had the highest likelihood of regraft, despite improvements in cytotoxic therapy.59 Resection of the perilimbal conjunctiva associated with PUK removes immune complexes, decreases production of collagenases and proteinases, and consequently promotes resolution of inflammation. This treatment is controversial, because it is thought that PUK may recur once the conjunctiva grows back to the limbus.1,3,4,8,16

In addition to medical treatment, an amniotic membrane could be used as a patch or graft to reduce inflammation and to promote re-epithelization. It is likely that the biologic properties of amniotic membrane downregulate inflammation due to expression of Fas ligand and human leucocyte antigen-G that reduce inflammation and activate suppressor T cell mechanisms.60–63

Conclusion

PUK includes a group of corneal infectious and inflammatory diseases that usually result in peripheral corneal thinning. Inflammatory causes are usually associated with life-threatening autoimmune collagen vascular diseases, and PUK might be the initial sign of a systemic disease. Limbal and conjunctival vessels are prone to deposition of circulating immune complexes; increased deposition of these complexes increases immunologic activity, which leads to vascular occlusion and subsequent leakage of inflammatory cells, along with collagenases and proteases. Usually scleritis, specifically the necrotizing form, is present in the region adjacent to PUK in patients with underlying systemic autoimmune disease. As such, local infectious diseases, either primary or secondary, must be excluded and extensive examination should not be overlooked for diagnosis of systemic disease. The mainstay of treatment is not only controlling inflammation of the involved ocular tissues, but may also include controlling the underlying systemic vasculitic disease. Initiation of appropriate immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents are life-saving. Recently, biologic agents that serve as TNF-α antagonists by blocking its receptors have become more important in the treatment of cases refractory to conventional immunomodulatory therapy. Because of the potential side effects of these treatments, close follow-up and regular laboratory investigations are essential.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Galor A, Thorne JE. Scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2007;33:835–854. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odorcic S, Keystone EC, Ma JJ. Infliximab for the treatment of refractory progressive sterile peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with late corneal perforation: 3-year follow-up. Cornea. 2009;28:89–92. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318181a84f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartly J, Mondino BJ. Inflammatory diseases of the peripheral cornea. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:463–472. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tauber J, Sainz de la Maza M, Hoang-Xuan T, Foster CS. An analysis of therapeutic decision making regarding immunosuppressive chemotherapy for peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Cornea. 1990;9:66–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladas JG, Mondino BJ. Systemic disorders associated with peripheral corneal ulceration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:468–471. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200012000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung G. Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis and marginal staphylococcal keratitis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, editors. Cornea: Fundamentals, Diagnostic, Management. 3rd ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akpek EK, Thorne JE, Qazi FA, Do DV, Jabs DA. Evaluation of patients with scleritis for systemic disease. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messmer EM, Foster CS. Vasculitic peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;43:379–396. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(98)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster CS, Forstot SL, Wilson LA. Mortality rate in rheumatoid arthritis patients developing necrotizing scleritis or peripheral ulcerative keratitis: Effects of systemic immune suppression. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1253–1263. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dana MR, Qian Y, Hamrah P. Twenty-five year panorama of corneal immunology. Cornea. 2000;19:625–643. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow YC, Foster CS. Mooren’s ulcer. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1996;36:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199603610-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown SI. What is Mooren’s ulcer? Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1978;98:390–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allansmith MR, McClellan B. Immunoglobulins in the human cornea. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90882-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mondino BJ, Brady KJ. Distribution of hemolytic complement activity in normal human donor cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:1430–1443. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930020304022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogan MJ, Alvarado JA. The limbus. In: Hogan MJ, editor. Histology of the Human Eye: An Atlas and Textbook. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory JK, Foster CS. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis in the collagen vascular diseases. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1996;36:21–30. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199603610-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiuey Y, Foster CS. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis and collagen vascular disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1998;38:21–32. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199803810-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottsch JD, Liu SH, Stark WJ. Mooren’s ulcer and evidence of stromal graft rejection after penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:412–417. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondino BJ. Experimental aspects and models of peripheral corneal disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1986;26:5–14. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198602640-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown SI, Mondino BJ, Rabin BS. Autoimmune phenomenon in Mooren’s ulcer. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;82:835–840. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kafkala C, Choi J, Zafirakis P, et al. Mooren ulcer: an immunopathologic study. Cornea. 2006;25:667–673. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000214216.75496.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster CS, Kenyon KR, Greiner J. The immunopathology of Mooren’s ulcer. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88:149–159. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottsch JD, Liu SH, Minkovitz JB, Goodman DF, Srinivasan M, Stark WJ. Autoimmunity to a cornea associated stromal antigen in patients with Mooren’s ulcer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1541–1547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virasch VV, Brasington RD, Lubniewski AJ. Corneal disease in rheumatoid arthritis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, editors. Cornea: Fundamentals, Diagnostic, Management. 3rd ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sainz de la Maza M, Jabbur NS, Foster CS. Severity of scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:389–396. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sainz de la Maza M, Molina N, Gonzales LA, Doctor PP, Tauber J, Foster CS. Clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keenan DJ, Mandel MR, Margolis TP. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with vasculitis manifesting asymetrically as Fuchs superficial marginal keratitis and Terrien’s marginal dejeneration. Cornea. 2011;30:825–827. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182000c94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin P, Brown SI. Inflammatory Terrien’s marginal corneal disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90768-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srinivasan M, Zegans ME, Zelefsky JR, et al. Clinical characteristics of Mooren’s ulcer in South India. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:570–575. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.105452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg P, Sangwan VS. Mooren’s ulcer. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, editors. Cornea: Fundamentals, Diagnostic, Management. 3rd ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarabishy AB, Schulte M, Papaliodis GN, Hoffman GS. Wegener’s granulomatosis: clinical manifestations, differential diagnosis, and management of ocular and systemic disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:430–444. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soukiasian SH, Foster CS, Niles JL, Raizman MB. Diagnostic value of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in scleritis associated with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)32027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS, Jabbur NS, Baltatzis S. Ocular characteristics and disease associations in scleritis-associated peripheral keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:15–19. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perry HD, Golub LM. Systemic tetracyclines in the treatment of non-infected corneal ulcers: a case report and proposed new mechanism of action. Ann Ophthalmol. 1985;17:742–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golub LM, Ramamurthy NS, McNamara TF, Greenwald RA, Rifkin BR. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown: new therapeutic implications for an old family of drugs. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2:297–321. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020030201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ralph RA. Tetracyclines and the treatment of corneal stromal ulceration: a review. Cornea. 2000;19:274–277. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200005000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS, et al. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:492–513. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Squirrel DM, Winfield J, Amos RS. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis ‘corneal melt’ and rheumatoid arthritis: a case series. Rheumatology. 1999;38:1245–1248. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.12.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galor A, Jabs DA, Leder HA, et al. Comparison of antimetabolite drugs as corticosteroid-sparing therapy for noninfectious ocular inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1826–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorne JE, Jabs DA, Qazi FA, Nguyen QD, Kempen JH, Dunn JP. Mycophenolate mofetil therapy for inflammatory eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobrin L, Christen W, Foster CS. Mycophenolate mofetil after methotrexate failure or intolerance in the treatment of scleritis and uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1416–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson SM, Lang LS. Leflunomide: inhibition of S-antigen induced autoimmune uveitis in Lewis rats. Agents Actions. 1994;42:167–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01983486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Messmer E, Foster S. Destructive corneal and scleral disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis: medical and surgical management. Cornea. 1995;14:408–417. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199507000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCarthy JM, Dubord PJ, Chalmers A, Kassen BO, Rangno KK. Cyclosporin A for the treatment of necrotising scleritis and corneal melting in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1358–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diaz-Valle D, Benitez del Castillo JM, Sayagues O, Sayagués O, Bañares A, García-Sánchez J. Immunological and clinical evaluation of postsurgical necrotising sclerocorneal ulceration. Cornea. 1998;17:371–375. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sfikakis PP, Theodossiadis PG, Katsiari CG, Kaklamanis P, Markomichelakis NN. Effect of infliximab on sight-threatening panuveitis in Behcet’s disease. Lancet. 2001;358:295–296. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith JR, Levinson RD, Holland GN, et al. Differential efficacy of tumor necrosis factor inhibition in the management of inflammatory eye disease and associated rheumatic disease. Arthritis Care Res. 2001;45:252–257. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)45:3<252::AID-ART257>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oh YJ, Kim MK, Wee WR. Infliximab for progressive peripheral ulcerative keratitis in a patient with juvenile rheumatoid arthiritis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55:70–71. doi: 10.1007/s10384-010-0889-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pham M, Chow CC, Badawi D, Tu EY. Use of infliximab in the treatment of peripheral ulcerative keratitis in Crohn’s disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas J, Pflugfelder S. Therapy of progressive rheumatoid arthritis-associated corneal ulceration with infliximab. Cornea. 2005;24:742–744. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000154391.28254.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tugal-Tutkun I, Ayranci O, Kasapcopur O, Kir N. Retrospective analysis of children with uveitis treated with infliximab. J AAPOS. 2008;12:611–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy CC, Ayliffe WH, Booth A, Makanjuola D, Andrews PA, Jayne D. Tumor necrosis factor a blockade with infliximab for refractory uveitis and scleritis. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:352–356. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goff BL, Vabres B, Cochereau I, et al. Eye loss by exogenous endophthalmitis following anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: a report of 4 cases. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2202–2203. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies. Systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295:2275–2285. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.19.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung ES, Packer M, Lo KH, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure. Results of the anti-TNF therapy against congestive heart failure (ATTACH) trial. Circulation. 2003;107:3133–3140. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000077913.60364.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puli SR, Benage DD. Retinal vein thrombosis after infliximab (Remicade) treatment for Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:939–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Theodossiadis PG, Markomichelakis NN, Sfikakis PP. Tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Preliminary evidence for an emerging approach in the treatment of ocular inflammation. Retina. 2007;27:399–413. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3180318fbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hernandez-Illas M, Tozman E, Fulcher S, et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor Fc fusion protein (Etanercept): experience as a therapy for sight-threatening scleritis and sterile corneal ulceration. Eye Contact Lens. 2004;30:2–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ICL.0000092064.05514.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maneo A, Naor J, Lee HM, Hunter WS, Rootman DS. Three decades of corneal transplantation: indications and patient characteristics. Cornea. 2000;19:7–11. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shimmura S, Shimazaki J, Ohashi Y, Tsubota K. Antiinflammatory effects of amniotic membrane transplantation in ocular surface disorders. Cornea. 2001;20:408–413. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200105000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Houlihan JM, Biro PA, Harper HM. The human anion is a site of MHC class Ib expression: evidence for the expression of HLA-E and HLA-G. J Immunol. 1995;154:5665– 5674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Griffith TS, Brunner T, Fletcher SM, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege. Science. 1995;270:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McGhee NJ, Patel F, Patel DV. Mooren’s ulcer and amniotic membrane transplant: a simple surgical solution? Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2011;39:383–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]