Abstract

S values for 11 major target organs for I-131 in the thyroid were compared for three classes of adult computational human phantoms: stylized, voxel and hybrid phantoms. In addition, we compared Specific Absorbed Fractions (SAFs) with the thyroid as a source region over a broader photon energy range than the x- and gamma-rays of I-131. S and SAF values were calculated for the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) reference voxel phantoms and the University of Florida (UF) hybrid phantoms by using Monte Carlo transport method, while the S and SAF values for the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) stylized phantoms were obtained from earlier publications. Phantoms in our calculations were for adults of both genders. The 11 target organs and tissues that were selected for the comparison of S values are: brain, breast, stomach wall, small intestine wall, colon wall, heart wall, pancreas, salivary glands, thyroid, lungs, and active marrow for I-131 and thyroid as a source region. The comparisons showed, in general, an underestimation of S values reported for the stylized phantoms compared to the values based on the ICRP voxel and UF hybrid phantoms and a relatively good agreement between the S values obtained for the ICRP and UF phantoms. Substantial differences were observed for some organs between the 3 types of phantoms. For example, the small intestine wall of ICRP male phantom and heart wall of ICRP female phantom showed up to 8-fold and 4-fold greater S values, respectively, compared to the reported values for the ORNL phantoms. UF male and female phantoms also showed significant differences compared to the ORNL phantom, 4.0-fold greater for small intestine wall and 3.3-fold greater for heart wall. In our method, we directly calculated the S values without using the SAFs as commonly done. Hence, we sought to confirm the differences observed in our S values by comparing SAFs among the phantoms with the thyroid as a source region for selected target organs - small intestine wall, lungs, pancreas and breast as well as illustrate differences in energy deposition across the energy range (12 photon energies from 0.01 to 4 MeV). Differences were found in SAFs between phantoms in a similar manner to the differences observed in S values but with larger differences at lower photon energies. To investigate the differences observed in S and SAF values, the chord length distributions (CLDs) were computed for the selected source-target pairs and compared across the phantoms. As demonstrated by the CLDs, we found that the differences between phantoms in those factors used in internal dosimetry were governed to a significant degree by inter-organ distances which are a function of organ shape as well as organ location.

Keywords: I-131, S value, Monte Carlo radiation transport, computational human phantoms

1. INTRODUCTION

It is not possible to directly measure the absorbed dose to the organs of the human body from nuclear medicine procedures. Hence, the formalism of the Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) committee of the Society of Nuclear Medicine (SNM) has been long adopted as the accepted calculation method to estimate radiation doses to organs from radionuclides distributed in the body (Loevinger et al., 1991). The absorbed doses to a target organ are derived by summing, over all source regions (rS), the products of the time-integrated activity in each source region, which might be obtained by solving biokinetic models or quantitative imaging via planar imaging, SPECT, and PET, with the corresponding S value (also called S factor), which is the mean absorbed dose to the target organ (rT) per unit of nuclear transition of the relevant radionuclide in the source region considered (Bolch et al., 2009). The S values which are derived from other quantities, i.e., absorbed fraction (AF) or specific absorbed fraction (SAF), primarily rely on Monte Carlo radiation transport calculations using computational models of the human anatomy (referred to as phantoms).

A comprehensive set of AFs (Snyder et al., 1978) and S values for 100 radionuclides were published by Snyder et al. (1975) at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) based on a reference adult hermaphrodite computational phantom. In addition, a series of pediatric computational phantoms was developed by Cristy and Eckerman at the ORNL and was utilized to extend the dose calculations to include different body sizes to emulate different ages (Cristy and Eckerman, 1987). The internal organ structure and external body contour of those first generation computational phantoms, called stylized (or mathematical) phantoms, are described by three-dimensional surface equations. The stylized phantoms have contributed significantly to radiation dosimetry in nuclear medicine but their relatively simplistic representation of human anatomy also allows for the possibility of dose estimations that are not completely realistic. This is especially a possibility in internal dosimetry calculations where target organ doses are sensitive to inter-organ distances.

To overcome the inherent limitations of the stylized phantoms, a class of computational human phantoms called voxel (or tomographic) phantoms, was developed which describe both the external body contour and internal organ structure through the use of tomographic images as available from magnetic resonance (MR) or computed tomography (CT) (Zaidi and Xu, 2007). The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) published reference adult male and female voxel phantoms (ICRP, 2009) with organ masses matched to reference values (ICRP, 2003). More recently, another class of human phantoms called hybrid or boundary representation (BREP) phantoms was reported by several research groups (Cassola et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2007a; Lee et al., 2010; Segars et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). The hybrid phantoms are described by non-uniform rational B-spline (NURBS) and polygon mesh (PM) surfaces, a more advanced mathematical format which can provide flexibility in modeling the body contour and organ structure. The voxel and hybrid phantoms with more realistic anatomy compared to the stylized phantoms enable researchers to compare the existing internal dosimetry quantities based on the stylized phantoms with the values estimated from the new classes of phantoms (Chao and Xu, 2001, 2004; Lee et al., 2007b; Park et al., 2008; Petoussi-Henss and Zankl, 1998; Shi et al., 2008; Yoriyaz et al., 2000; Zankl et al., 2003). Considerable differences have been reported from some of these comparisons, primarily due to differences in the organ masses and the inter-organ distances. For example, Smith et al (2001) reported SAF (Thymus ← Thyroid) 112.6 and 29.7 times greater for the voxel phantom than for the stylized phantom at 30 keV and 50 keV respectively. Smith et al. also reported estimates of committed equivalent doses to the thymus 31 and 63 times greater for the male voxel phantom compared to the stylized phantom for ingested I-129 and I-125, respectively. Distances between the thyroid and target organs, based on centers of mass, were reported to be smaller in the voxel phantom than for the stylized phantom. Here it should be emphasized that the voxel phantoms reflect the anatomy of the individual whose CT scans were used as the basis for the phantom as well as the positions of the organs in the supine position.

S values for I-131 in the thyroid are required for a reassessment of findings from an epidemiologic study conducted at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) that examined the mortality risks in a cohort of 23,000 nuclear medicine patients treated for hyperthyroidism with I-131. The organ dosimetry in the original epidemiologic study (Ron et al., 1998) was performed by using dose coefficients from ICRP Publication 53 (ICRP, 1987) which were based on the stylized phantoms (Eckerman et al., 2006). The importance of the choice of phantom used for an epidemiologic study is underscored, in this case, by the fact that hyperthyroid patients do not have typical biokinetics. For example, among hyperthyroid patients, the uptake of I-131 in the thyroid may range from 30 to 100% (Alexander and Larsen, 2002; Stabin et al., 1991; Zanzonico et al., 2004), considerably higher than the usual 30% for healthy individuals in the U.S. (Brill et al., 2006). The uptake and retention of I-131 into the thyroid and in other regions exposes other organs to radiations emitted from the I-131. The reassessment of the Ron et al. health risk study using more advanced human phantoms was intended to better evaluate the risk of late effects in the organs irradiated during the treatment by using improved dosimetry tools. The purpose of the present work was to determine how different the S values are from recently-reported advanced computational human phantoms compared to those from the stylized phantoms.

This paper presents a comparison of S values for I-131 in the thyroid obtained from the stylized phantoms which were used to derive the dose coefficients in the original Ron et al. (1998) epidemiologic study with values from two recently-published classes of computational human phantoms: voxel and hybrid phantoms. In addition, SAFs are compared over a broader photon energy range than the x- and gamma-rays of I-131. S and SAF values are calculated for the ICRP reference voxel phantoms and the University of Florida (UF) hybrid phantoms by using the Monte Carlo transport method and compared those with the values derived from the ORNL stylized phantoms more than 30 years ago. Phantoms in our calculations were for adults of both genders. In our method, we directly calculate the S values without using the SAFs as commonly done. Hence, we sought to confirm the results observed in our S values by comparing SAFs among the phantoms with the thyroid as a source region for selected target organs as well as illustrate differences in energy deposition across the wider energy range (12 photon energies from 0.01 to 4 MeV). The chord length distributions (CLD) for the selected source region and target organ pairs were computed and compared among those three classes of phantoms to better understand the variation in energy deposition between phantom classes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Computational human phantoms

In this work, S-values and SAFs were calculated in two classes of computational human phantoms: ICRP reference adult voxel phantoms and UF adult hybrid phantoms.

The first class of phantoms examined were the reference adult male and female voxel phantoms, recently released in ICRP Publication 110 (ICRP, 2009). ASCII files provided by the ICRP in their supporting documentation represents two three-dimensional matrices of 7.16 and 14.26 million voxels with voxel resolutions of 36.5 and 15.3 mm3 for adult male and female, respectively. The organ masses and body dimensions of each phantom are reported to match the reference values reported by ICRP Publication 89 (ICRP, 2003). The densities and elemental compositions for organs and tissues provided in the ICRP Publication 110 were used in the Monte Carlo simulations.

Phantoms of the second class that we examined were the adult male and female hybrid phantoms developed collaboratively between the University of Florida (UF) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (Lee et al., 2010). The masses of organs and tissues of the UF hybrid phantoms were also matched to the values in ICRP Publication 89 (ICRP, 2003). The reference elemental compositions for organs and tissues provided by the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU) Report 46 (ICRU, 1992) and ICRP Publication 89 were utilized in the Monte Carlo calculations. The dimensions of a total of 11 different body parts were matched to the reference anthropometric data for the United States (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm): standing height, sitting height, arm length (acromion-radiale, radiale-stylion, and hand), the circumferences of head, neck, waist, and buttock, and biacromial breadth. Finally, the dimensions of the alimentary tracts were matched to the data in ICRP Publication 100 (ICRP, 2006). The UF hybrid phantoms include 44 organs as well as 32 different skeletal sites where cortical and spongiosa structures were separately modeled to facilitate active marrow dose calculation. The original adult male and female hybrid phantoms with NURBS/PM surfaces were converted into voxel format with a resolution of 3 mm3. The resulting male and female phantoms contained 11.7 and 9.5 millions voxels, respectively.

2.2. Estimation of the dosimetric quantities of interest

As described, the absorbed dose to a target organ D(rT)(mGy) is estimated by summing, over all source regions (rS), the products of the time-integrated activity Ã(rS)(Bq·s) in each source region with the corresponding S value, which is the mean absorbed dose to the target organ (rT) per unit of nuclear transition of the relevant radionuclide in the source region considered (Bolch et al., 2009):

| (1) |

The thyroid is the only source region considered in this study since the thyroid uptake of the I-131 from blood is considerably greater than all other organs and especially so in persons with hyperthyroidism. The absorbed dose D(rT)(mGy) is proportional to the S value (mGy/(Bq·s)), S(rT ←rS), which is defined as

| (2) |

where ϕ(rT ←rS,Ei) is the absorbed fraction (AF) at energy Ei, which is defined as the fraction of radiation energy Ei emitted within the source region rS that is absorbed in a target organ rT, Yi is the radiation yield for the ith nuclear transition per nuclear transformation, and M(rT) is the mass of the target organ. The SAFs, Φ(rT ←rS, Ei), are derived from the AFs, ϕ(rT ←rS, Ei). The SAFs and AFs are related as:

| (3) |

As shown in Equation (2), S values are usually derived from the AFs or SAFs. However, in this study, the S values were directly calculated from the Monte Carlo simulations which were carried out separately for photons and electrons. The simulations provided the energy deposition in each target organ rT per emitted particle, noted as Eγ(rT) and Eβ(rT)(MeV/particle) for photons and electrons, respectively. The products of the energy deposition per particle and either the total photon Yγ or electron Yβ yield per decay were computed (eq. 4) and summed to compute the S value (mGy/(Bq·s)):

| (4) |

where 1.602× 10-10 is the number of joules per MeV.

A general purpose Monte Carlo code, MCNPX version 2.5.0 (Pelowitz, 2005), was employed to calculate S values and SAFs from the ICRP voxel phantoms and UF hybrid phantoms. The four different male and female phantoms were incorporated into MCNPX lattice file. The size of the final ASCII files of ICRP voxel phantoms were much smaller than that of the ASCII files provided in ICRP Publication 110 due to a compression feature (e.g. “0 0 0 0” was compressed into “0 3R”) built in an in-house conversion code. Organ- and tissue-specific density and elemental composition were implemented into the material card of the MCNPX code. The radioactive source was described as a uniform source of radiation within the given source region, the thyroid, by explicitly specifying the location of each voxel included in the thyroid within the phantom matrix. The location data of the source voxels were generated from each phantom by using a code developed in-house.

The energy deposition in the target organs was scored using *F8 tally for both S values and SAFs except the active marrow which required photon fluence using *F4 tally. The mode P E and the Integrated Tiger Series (ITS) algorithm was selected for both S values and SAFs calculations to enable the transport and scoring of photons and electrons. The use of the ITS algorithm did not significantly change the results in our calculations compared to the MCNPX built-in algorithm but reduced the computational time as reported by (Chiavassa, 2005). A total of 107 particles were simulated to give a statistical error of less than 2% for most target organs. The latest I-131 photon spectra published in ICRP Publication 107 (ICRP, 2008) were employed for the estimation of the S values including all × and gamma rays; those with yields > 0.2% are shown in Table 1. The beta and Auger electron spectra were approximated by their mean energy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Energy and yield of the major photon (X and gamma, γ) and electron (mean energies of beta minus, β-) emissions resulting from I-131 decay.

| Type |

Energy (MeV) |

Yield (/(Bq.s)) |

|---|---|---|

| X | 1.66E-05 | 7.63E-01 |

| X | 2.95E-02 | 1.40E-02 |

| X | 2.98E-02 | 2.59E-02 |

| γ | 8.02E-02 | 2.62E-02 |

| γ | 2.84E-01 | 6.14E-02 |

| γ | 3.64E-01 | 8.17E-01 |

| γ | 6.37E-01 | 7.17E-02 |

| γ | 7.23E-01 | 1.77E-02 |

| β- | 6.93E-02 | 2.09E-02 |

| β- | 9.66E-02 | 7.24E-02 |

| β- | 1.92E-01 | 8.95E-01 |

Absorbed doses to active marrow in both the ICRP voxel and UF hybrid phantoms were estimated by using a fluence-to-dose response function (DRF) developed at the University of Florida (Johnson et al., 2011). The DRFs used here are updated versions of functions originally formulated by Cristy and Eckerman (1987). In this instance, the DRFs were pre-calculated for a total of 32 bone sites to convert the photon fluence in a skeletal spongiosa target region to the absorbed dose in an active marrow region. Photon fluence in each bone site was scored for 25 energy bins ranging from 0.01 to 10 MeV within MCNPX and converted into the absorbed doses to active marrow at each bone site through a post-process where DRFs were applied. The DRFs for photons only up to 4 MeV were actually used for this paper. The total absorbed dose to active marrow in the whole body was calculated by weighting the bone site-specific absorbed doses by the active marrow distribution for the reference adult male (Hough et al., 2011).

We calculated S values for a total of 11 target organs considered in the reanalysis of risk to the cohort of hyperthyroidism patients: brain, breast, stomach wall, small intestine wall, colon wall, heart wall, pancreas, salivary glands, thyroid, lungs, and active marrow. The S values from the Monte Carlo calculations using the ICRP voxel and UF hybrid phantoms were compared with the values for adult male and female stylized phantoms1 denoted as “S values for ORNL stylized phantom”. Since we directly calculated the S values without using the SAFs as commonly done, we compared SAFs among the phantoms to confirm our S values as well as to illustrate differences in energy deposition across the energy range (12 photon energies from 0.01 to 4 MeV). The SAFs were computed using the voxel and hybrid phantoms and compared with the values obtained from ORNL/TM Report 8381 (Cristy and Eckerman, 1987). The 15-year-old hermaphrodite stylized phantom is recommended as the surrogate of adult female in the ORNL Report 8381. Therefore, the S values and SAFs from this phantom were used for the comparison with the two female voxel and hybrid phantoms.

2.3. Calculation of chord length distributions

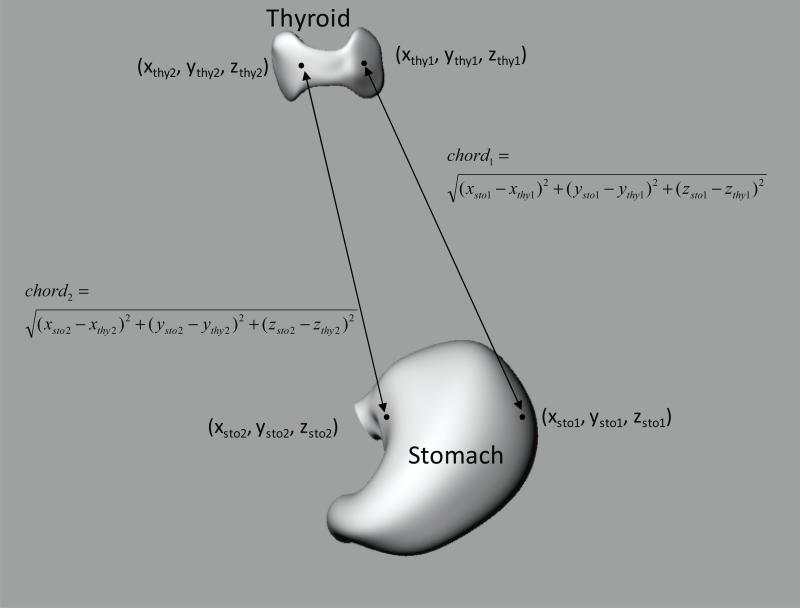

Dose delivered to a target organ from a source region is mainly governed by the activity in the source and the attenuation between the source and target, the latter being a function of the distance between the two organs and the density and elemental composition of intervening tissue. To explain the differences in S and SAF derived from different phantoms, inter-organ distances have usually been expressed using the distance between their center of mass (Smith et al., 2001). However, while distances between the centers of mass provide information on the relative location between the source region and the target, these distances do not fully capture the volume distribution of either one, whereas any point can contribute to a radioactive emission for a source region or to an energy deposition in a target organ. To better represent the relative distributions in the space of the source region and the target organ, we computed chord length distributions, (CLDs). A chord length distribution is a frequency histogram of distances between points in the source and target regions. The CLD is generated by randomly sampling a large number of points in each organ and assessing the distances between pairs where each pair contains a point in the source and in the target region. Figure 1 illustrates two randomly selected points in the thyroid and stomach and the calculation of chord length for each pair.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the calculation of chord lengths between thyroid and stomach.

For the ICRP voxel and the voxelized UF hybrid phantoms, the position of each point in the source region and target organ was derived from a random sampling of the phantom binary data arrays to select the voxel position (one corner of the voxel (i, j, k)) within the source regions and target organs respectively. The voxel positions were then multiplied by the voxel resolution to calculate the distance between the pair of points. This process was repeated 50,000 times to obtain a stable frequency distribution of the chord lengths in histogram format. We also computed CLD for the stylized phantoms generated from a software package, BodyBuilder (White Rock Science, White Rock, NM), (denoted as “ORNL stylized phantoms” hereafter) to compare with those from voxel and hybrid phantoms. In the case of the stylized phantoms, a thousand locations were randomly sampled from the source region and target organs separately by using the MCNPX source sampling function. Then, in the same manner with the voxel phantoms, the generation of chord lengths was repeated 50,000 times in order to obtain a stable frequency distribution.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1. Comparison of S values

The process of S value calculation was validated by comparing the S values calculated from the adult male stylized phantom, generated from BodyBuilder software package, with the values for the original ORNL stylized phantoms.2 The S values calculated in this study were in a good agreement with the values from ORNL, within 7% on average. Some organ values, however, showed larger differences; for example, S values for the small intestine wall were 3.06 × 10-15 (obtained from ORNL) and 3.86 × 10-15 (calculated in this study) mGy/(Bq·s) (26% difference). Possible factors influencing the observed differences in S values include:

Differences in the anatomy of the stylized phantom that we generated from BodyBuilder software compared with the anatomical geometry for the original stylized phantoms

Differences in the precision of the calculations. The Body-Builder results have an uncertainty of less than 3%, while the SAFs from ORNL have coefficients of variation of up to 20% (Cristy and Eckerman, 1987).

The use of different Monte Carlo codes and photon cross sections.

The S values for I-131 in the thyroid computed for the ICRP voxel and hybrid phantoms are compared to the S values for the stylized phantoms in Table 2. As expected, the thyroid gland has the greatest S value from I-131 distributed within itself in all three classes of phantoms. There are no differences in the thyroid S values among the three phantoms as the mass of the gland is the same in all phantoms. Salivary glands had the second greatest S value from I-131 distributed in the thyroid for all the three classes of phantoms. The third greatest S value is found for lungs in the ICRP and UF phantoms and for brain in the ORNL male and female phantoms. Heart walls and active marrow have greater S values than the brain in the ICRP and UF phantoms whereas the brain S value is greater than the S value to the heart wall and active marrow in the ORNL phantoms. The cross-fire energy deposition from the electrons is less than 0.1% of the energy deposition from photons. Hence the contribution of cross-fire electrons can be considered negligible compared to the contribution from cross-fire photons.

Table 2.

S values (mGy/(Bq-s)) for I-131 in thyroid obtained from ICRP voxel, UF hybrid, and ORNL stylized male and female phantoms. The ratios of the S values (ICRP to ORNL, UF to ORNL and UFto ICRP) were also tabulated.

| Target organs | I -131 S values with thyroid as a source organ (mGy/(Bq-s)) | Ratio | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICRP voxel phantoms | UF hybrid phantoms | ORNL stylized phantoms | ICRP/ORNL | UF/ORNL | ||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Brain | 1.5E-13 | 2.5E-13 | 2.2E-13 | 3.0E-13 | 4.2E-13 | 4.4E-13 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Breast | 1.4E-13 | 4.2E-13 | 1.3E-13 | 1.3E-13 | 1.0E-13 | 1.4E-13 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Stomach Wall | 1.2E-13 | 8.6E-14 | 6.5E-14 | 8.3E-14 | 2.2E-14 | 3.6E-14 | 5.4 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 2.3 |

| Small Intestine Wall1 | 2.4E-14 | 2.0E-14 | 1.2E-14 | 2.0E-14 | 3. IE-15 | 6.4E-15 | 7.9 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 3.1 |

| Colon Wall | 3.0E-14 | 1.1E-14 | 1.3E-14 | 1.6E-14 | 4.2E-15 | 7.2E-15 | 7.2 | 1.5 | 3.2 | 2.2 |

| Heart wall | 6.4E-13 | 6.7E-13 | 3.8E-13 | 5.4E-13 | 1.3E-13 | 1.6E-13 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| Pancreas | 7.1E-14 | 5.4E-14 | 3.0E-14 | 5.4E-14 | 3.2E-14 | 4. IE-14 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Salivary glands2 | 9.2E-13 | 1.7E-12 | 1.8E-12 | 2.4E-12 | 3.4E-12 | 3.7E-12 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Thyroid | 1.6E-09 | 1.9E-09 | 1.7E-09 | 1.9E-09 | 1.6E-09 | 1.9E-09 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Lungs | 9.1E-13 | 1.0E-12 | 6.2E-13 | 8.7E-13 | 2.5E-13 | 3.2E-13 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Active Marrow | 5.8E-13 | 6.8E-13 | 3.9E-13 | 4.9E-13 | 2.4E-13 | 2.7E-13 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

Small intestine wall and contents are not separated in the ORNL stlylized phantoms.

S values for the salivary gland for ORNL stylized phantoms were calculated from point kernel method with photon build-up factor.

Ratios of male to female S values are plotted for the three classes of phantoms in Figure 2 to evaluate the consistency of the classes of computational phantoms across the genders. Since the female phantoms have a smaller body size than the male, shorter distances between thyroid and target organs are expected if it is assumed that the body height determines the organ placement. This would result in less attenuation and higher photon fluences in the target organs according to the inverse square law, so that target organs in the female phantoms would receive greater energy depositions than those in the male phantoms. S values to organs in female phantoms are overall greater for corresponding organs in the male phantoms as indicated by a ratio less than unity (bold solid line). In the case of the ICRP phantoms, however, some organs such as the stomach wall, small intestine wall, colon wall, and pancreas in the male phantom received greater S values than in the female phantom, an opposite trend compared to female to male differences for the UF and ORNL phantoms. The colon wall of the ICRP male phantom received up to 2.8-fold greater S value than that of ICRP female phantom.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the ratios of the S values from male phantoms to those from female phantoms for ICRP voxel, UF hybrid, and ORNL stylized phantoms.

Ratios of the S values from ICRP and UF phantoms to the values from ORNL phantoms are tabulated by gender in Table 2. The salivary glands in the ICRP and UF phantoms receive smaller S values than in the ORNL phantoms (which was not included in the ORNL phantom but later estimated via a point kernel calculation). The S value of salivary glands in ICRP male phantom is only 30% of the value of the ORNL male phantom. Conversely, the S values for the lungs in the ICRP and UF phantoms are significantly greater than the values in the ORNL phantoms. In the case of the ICRP male phantom, the lungs S value is 3.6-fold greater than the value from the ORNL male phantom. Although the absolute S values are relatively smaller for gastro-intestinal organs than other target organs, the S values for those organs in the ICRP and UF phantoms are significantly greater than the values of the ORNL phantoms. The small intestine wall of the ICRP male phantom has a 7.9-fold greater S value than that of the ORNL male phantom.

The ratios of the S values from UF to ICRP are also reported in Table 2. The S value ratios vary for the male phantoms from 0.4 (colon wall and pancreas) to 2 (salivary glands), and for the female phantoms from 0.3 (breast) to 1.4 (colon wall and salivary glands). Considering that both the UF and ICRP phantoms have organ masses matched to the reference man, the differences in S factors are likely a consequence of differences in organ placement and organ shapes between the subjects used to derive each phantom.

3.2. Comparison of Specific Absorbed Fractions

To confirm the differences observed in S values and describe the differences in energy deposition across a broader energy range than the x- and gamma-rays from I-131, SAFs were calculated for 12 photon energies from 0.01 to 4 MeV and for selected target organs for the ICRP and UF phantoms. The results were compared with the SAFs for ORNL stylized phantoms obtained from ORNL/TM Report 8381 (Cristy and Eckerman, 1987). Small intestine wall of male and lungs of female are an example of organs with significant differences in S values between the ICRP and UF phantoms when compared to the ORNL phantoms (Table 2), while the male pancreas and the female breasts are examples of organs with negligible differences in S values derived using the ICRP and UF phantoms and stylized phantoms. It should be noted that the small intestine wall was not modeled separately from the contents in the ORNL phantom so that the SAF was calculated using the whole organ.

The SAFs for those four target organs, small intestine and pancreas in male and lungs and breast in female phantoms, are presented in Figure 3. The differences in the S values among the three classes of phantoms shown in Table 2 are also reflected in the comparisons of the SAFs. Figure 3(a) and 3(b) shows the comparison of male SAF (Small Intestine wall ← Thyroid) and female SAF (Lungs ← Thyroid), respectively, among ICRP, UF, and ORNL phantoms. As shown in Figure 3(a), SAFs for small intestine wall in ICRP and UF phantoms are greater than those in ORNL phantoms, which was the same for the S value comparison in Table 2. The ratio of SAFs (Small Intestine wall ← Thyroid) from ICRP and UF male phantoms to the values from the ORNL male phantom is illustrated in Figure 4. As the photon energy decreases, the differences between ICRP and UF phantoms compared to ORNL phantoms increases since photons released from source regions experience greater attenuations compared to higher energy photons. The ratios for the photon energy of 364 keV are 8.6 and 4.3 for ICRP to ORNL and UF to ORNL, respectively. The ratios are comparable with the ratios of S values as shown in Table 2, 7.9 and 4.0 for ICRP to ORNL and UF to ORNL, respectively, at the primary photon energy of I-131 (364 keV gamma ray).

Figure 3.

Comparison of specific absorbed fractions for (a) male small intestine wall, (b) male pancreas, (c) female lungs, and (d) female breasts in ICRP voxel, UF hybrid, and ORNL stylized phantoms.

Figure 4.

Ratios of SAFs (Small Intestine wall ← Thyroid) from ICRP and UF phantoms to those from ORNL phantom.

S values for female lungs in ICRP and UF phantoms are 3.1-fold and 2.7-fold greater than those of ORNL phantom, respectively as shown in Table 2 and Figure 3(b).

Conversely, a good agreement of S values for pancreas between UF and ORNL female phantoms is also reflected in Figure 3(c) where SAF (Pancreas ← Thyroid) is presented. The agreement of S values for breasts between UF and ORNL female phantoms in Table 2 is shown in Figure 3(d) where SAF (Breasts ← Thyroid) are illustrated. Regarding the comparison between the UF and the ICRP phantoms, the SAF (Lungs ← Thyroid) for UF female phantom is comparable to SAF derived from the ICRP female phantom. The S value ratio for lungs between the UF and ICRP female phantom is similar (Table 2). In contrast, the SAFs from UF phantoms are significantly lower for the small intestine, pancreas and breast (Figure 3(a, c, d)), which confirms the S value ratios of UF to ICRP 0.5, 0.4 and 0.3, respectively (Table 2). The trends observed in the S values are also found in the SAF.

3.3. Comparison of the chord length distributions

To better understand the source of differences of S and SAF values among the three classes of phantoms, the CLD was estimated for the phantoms for the thyroid-target organ pairs discussed in the previous section. Figure 5 (a-d) presents comparisons of the CLD between four organ pairs: (a) Small Intestine Wall and Thyroid in male phantoms, (b) Lungs and Thyroid in female phantoms, (c) Pancreas and Thyroid in male phantoms and (d) Breasts and Thyroid in female phantoms. Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) are included in the legend for each CLD histogram.

Figure 5.

Comparison of chord length distributions for (a) male small intestine wall, (b) male pancreas, (c) female lungs, and (d) female breasts in ICRP voxel, UF hybrid, and ORNL stylized phantoms. M and SD in the legend stand for mean and standard deviation, respectively.

As shown in Figure 5(a), the CLD between small intestine wall and thyroid in the ICRP and UF male phantoms are shifted towards smaller values compared to the CLD from the ORNL male phantom, implying that the small intestine and the thyroid are closer together in the CT-based phantoms. The mean chord lengths are 39.7 and 43.7 cm for ICRP and UF phantoms, respectively, whereas the mean chord length for the ORNL male phantom is 51.4 cm. The S values for small intestine wall are 3.06 × 10-15, 1.23 × 10-14 and 2.41 × 10-14 mGy/(Bq·s) for the ORNL, UF and ICRP phantoms, respectively (Table 2). Moreover, the CLD for the ICRP and UF phantoms have a significantly larger standard deviation (7.1 cm and 5.0 cm, respectively) than does the ORNL phantom (3.0 cm). As can be seen in Fig. 5(a), the CLD for the ORNL is a relatively sharp peak while the CLD for the ICRP and UF phantoms are broader with some small undulations. These differences in the spread and shapes of the CLDs generally reflects differences in the organ shapes, particularly between the CT-based phantoms, which presumably represent realistic organ shapes, and the stylized phantom which has a highly simplified organ shape. These differences in shapes of the organs result in differences in the S values.

In Figure 5(b) where the CLDs between lungs and thyroid for female phantoms are illustrated, the CLDs for the CT-based phantoms are shifted to smaller values compared to the CLD of the ORNL adult female phantom. This shift demonstrates the approximately 3-fold greater S values for the CT-based phantoms. The CLD from the ICRP and UF phantoms have similar mean distances (14.5 cm and 15.5 cm respectively) and identical spreads (4.6 cm standard deviation), both indicating very similar inter-organ distances and shapes.

Figure 5(c) shows a good agreement in CLD between pancreas and thyroid between the UF and ORNL male phantoms which correlates with similar S values found in Table 2. However, the CLD for the ICRP phantom is shifted by about 20% (~7 cm ) towards shorter distances compared to the ORNL and UF phantoms, with S value for the ICRP being about 2.2 and 2.5 times higher than the ORNL and UF phantom respectively. Similarly, Figure 5(d) shows good agreement for the CLD between breasts and thyroid for UF female phantom and the ORNL adult female phantom while the CLD for the ICRP female phantom is shifted about 35% (~) 6 cm towards lower values. The S values from ORNL, UF and ICRP female phantoms are 1.37 × 10-13, 1.32 × 10-13 and 4.16 × 10-13 mGy/(Bq·s) respectively.

To further investigate the relationship between S value and CLD, the small intestine in the stylized male phantom was modified so that the width and shape of its CLD (Small Intestine Wall, Thyroid) was closely matched to that of the ICRP male phantom (Figure 6). The modification of the original ORNL small intestine model was made in three steps. First, the shape was simplified by using a full orthogonal parallelepiped of the same volume and center of mass as the ICRP phantom. Second, it was shifted 12 cm closer to the thyroid and made 16 cm thicker in the vertical direction. Finally, the lateral and anterior-posterior lengths were made 8 cm and 3 cm shorter, respectively, so that the organ volume was kept constant. The two CLDs for the original and modified small intestines are illustrated in Fig. 6 with dotted and dashed lines, respectively, and compared with that of the ICRP male phantom (solid line). The S value calculated from the original small intestine of the ORNL phantom, 3.86 × 10-15 mGy/(Bq·s), as mentioned in Section 3.1 was increased to 3.68 × 10-14 mGy/(Bq·s) for the modified small intestine which is much closer to 2.41 × 10-14 mGy/(Bq·s) of ICRP male phantom in Table 2. This exercise demonstrates that similar CLDs produce similar S values.

Figure 6.

Comparison of chord length distributions for small intestine and thyroid among original and modified ORNL stylized phantoms and ICRP adult male phantom. M and SD in the legend stand for mean and standard deviation, respectively.

It should be emphasized that in addition to inter-organ distance, the density and elemental composition of the material(s) traversed by photons transported from source to target organs should also be taken into account to better understand the causes of the S value differences. Although the same organ has similar density in the three classes of phantoms, the arrangement of the organs positioned between the source region and target organs (i.e. position and shape of lungs when considering S values of small intestine from thyroid source) can be different and contribute to differences of the S values. Additional computations where density and elemental composition between organs is incorporated will help better explain the differences in internal dosimetry quantities across different computational human phantoms.

3.4. Implications for the epidemiologic studies

The computations of S values for I-131 in the thyroid were undertaken in the framework of a reevaluation of the results of an epidemiologic study on the health risks resulting from the administration of I-131 for the treatment of hyperthyroidism (Ron et al., 1998). Use of a biokinetic model for hyperthyroid patients developed to replace the biokinetic model used in ICRP Publication 53 (ICRP, 1987) coupled with our S values derived from the CT-based phantoms, suggests that dose estimates for some organs could be substantially different. In particular, the use of the internal dosimetry factors presented here will result in greater doses for the breasts, the heart wall, the lungs and the active marrow, compared to the stylized phantom used in ICRP 53 while the organ doses will be smaller for the urinary bladder and the salivary glands.

4. Conclusions

S values for I-131 distributed in the thyroid gland were compared among three classes of computational human models: stylized, voxel and hybrid phantoms. The comparisons showed, on average, greater S values (up to 7.9-fold for small intestine wall of ICRP male phantom) for the ICRP voxel and the UF hybrid phantoms compared to the values from the ORNL stylized phantoms. The comparison of SAFs among the three phantom sets showed similar differences as in the S values and provided additional understanding of the differences in energy deposition in the targets across a broader energy range than I-131 photon spectrum. To better understand the differences in S values and SAFs between phantoms, CLDs were generated and compared among the phantoms. Our analysis showed the differences in those dosimetric factors were strongly correlated with inter-organ distances and organ shapes as demonstrated by differences in mean, standard deviation and shape of the CLDs. CLDs between target organ and source region provide more information than just the distance between their center of mass as reported in Smith et al (2001) because the shapes of the organs are reflected in the width of the CLD. Since the ICRP and UF phantoms are considered to more realistically model the human anatomy than the earlier stylized phantoms, the tendency of underestimation of S values in the stylized phantoms appears to result from less realistic locations of the organs with respect to one another as well as less realism in their shape. Unexpectedly, we observed differences in S values between the ICRP voxel and UF hybrid phantoms that were both designed to match the ICRP reference anatomy data. While differences in dosimetric factors between different classes of phantoms may not be important for determining compliance with radiation protection standards based on effective dose, the differences can be vitally important in epidemiologic applications where realistic organ doses are needed (Simon et al., 2006).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their appreciation for valuable comments from Dr. Wesley Bolch at the University of Florida and their appreciation for technical assistance from Mr. Brian Moroz at the Radiation Epidemiology Branch at National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Personal communication (KF Eckerman 2009)

Personal communication (Eckerman 2009)

REFERENCES

- Alexander EK, Larsen PR. High dose 131I therapy for the treatment of hyperthyroidism caused by Graves’ disease. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2002;87:1073. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolch WE, Eckerman KF, Sgouros G, Thomas SR. MIRD Pamphlet No. 21: A Generalized Schema for Radiopharmaceutical Dosimetry--Standardization of Nomenclature. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:477. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill A, Stabin M, Bouville A, Ron E. Normal organ radiation dosimetry and associated uncertainties in nuclear medicine, with emphasis on iodine-131. Radiation Research. 2006;166:128–40. doi: 10.1667/RR3558.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassola V, Lima V, Kramer R, Khoury H. FASH and MASH: female and male adult human phantoms based on polygon mesh surfaces: I. Development of the anatomy. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:133. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/1/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao TC, Xu XG. Specific absorbed fractions from the image-based VIP-Man body model and EGS4-VLSI Monte Carlo code: internal electron emitters. Phys Med Biol. 2001;46:901–27. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/4/301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao TC, Xu XG. S-values calculated from a tomographic head/brain model for brain imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:4971–84. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/21/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiavassa S. Developpement d`un outil dosimetrique personnalise pour la radioprotection en contamination interne et la radiotherapie vectorisee en medecine nucleaire. Universite Paul Sabatier; Toulouse, France: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cristy M, Eckerman KF. Specific absorbed fractions of energy at various ages from internal photon sources. Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Oak Ridge, TN: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Eckerman K, Leggett R, Cristy M, Nelson C, Ryman J, Sjoreen A, Ward R. DCAL: User's Guide to the DCAL System. ORNL/TM-2001/190. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. ANNEXE. 2006.

- Hough M, Johnson P, Rajon D, Jokisch D, Lee C, Bolch W. An image-based skeletal dosimetry model for the ICRP reference adult male—internal electron sources. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:2309. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/8/001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICRP . ICRP Publication. Vol. 53. International Commission on Radiological Protection; Elmsford, NY: 1987. Radiation Dose to Patients from Radiopharmaceuticals. [Google Scholar]

- ICRP . ICRP publication. Vol. 89. International Commission on Radiological Protection; Oxford: 2003. Basic anatomical and physiological data for use in radiological protection : reference values. p. xi.p. 265. [Google Scholar]

- ICRP Human alimentary tract model for radiological protection. ICRP Publication 100. A report of The International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ann ICRP. 2006;36:25–327. iii. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICRP Nuclear Decay Data for Dosimetric Calculations. ICRP Publication 107. Annales of the ICRP. 2008;38 doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICRP . Adult Reference Computational Phantoms. Pergamon Press: International Commission on Radiological Protection; Oxford: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ICRU . ICRU Report. Vol. 46. International Commission on Radiation Unit and Measurement; Bethesda, MD: 1992. Photon, Electron, Proton and Neutron Interaction Data for Body Tissues. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PB, Bahadori AA, Eckerman KF, Lee C, Bolch WE. Response functions for computing absorbed dose to skeletal tissues from photon irradiation—an update. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:2347. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/8/002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Lee C, Lodwick D, Bolch WE. Development of hybrid computational phantoms of newborn male and female for dosimetry calculation. Phys Med Biol. 2007a;52:3309–33. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/12/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Lodwick D, Hurtado J, Pafundi D, Williams JL, Bolch WE. The UF family of reference hybrid phantoms for computational radiation dosimetry. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:339–63. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/2/002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Park S, Lee JK. Specific absorbed fraction for Korean adult voxel phantom from internal photon source. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2007b;123:360–8. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncl167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loevinger R, Budinger TF, Thomas F, Watson EE. MIRD Primer for Absorbed Dose Calculations revised edition. Society of Nuclear Medicine; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Lee JK, Lee C. Dosimetry calculations for internal electron sources using a Korean reference adult stylised phantom. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2008;130:186–205. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncm487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelowitz DB. MCNPX user's manual Version 2.5.0. Los Alamos National Laboratory; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petoussi-Henss N, Zankl M. Voxel anthropomorphic models as a tool for internal dosimetry. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1998;79:415–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ron E, Doody MM, Becker DV, Brill AB, Curtis RE, Goldman MB, Harris BSH, Hoffman DA, McConahey WM, Maxon HR, Preston-Martin S, Warshauer ME, Wong FL, Boice JD, Group ftCTTF-uS Cancer Mortality Following Treatment for Adult Hyperthyroidism. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:347–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segars WP, Tsui BM, Da Silvia AJ, Shao L. PET-CT image fusion using the new 4D NURBS-based Cardiac-Torso (NCAT) phantom. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:13P–P. [Google Scholar]

- Shi CY, Xu XG, Stabin MG. SAF values for internal photon emitters calculated for the RPI-P pregnant-female models using Monte Carlo methods. Med Phys. 2008;35:3215–24. doi: 10.1118/1.2936414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SL, Bouville A, Kleinerman R, Ron E. Dosimetry for epidemiological studies: learning from the past, looking to the future. Radiat Res. 2006;166:313–8. doi: 10.1667/RR3536.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Phipps AW, Petoussi-Henss N, Zankl M. Impact on internal doses of photon SAFs derived with the GSF adult male voxel phantom. Health Phys. 2001;80:477–85. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder WS, Fisher HL, Ford MR, Warner GG. MIRD Pamphlet No 5, Revised: Estimates of Absorbed Fractions for Monoenergetic Photon Sources Uniformly Distributed in Various Organs of a Heterogeneous Phantom. Society of Nuclear Medicine; New York: 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabin M, Watson E, Marcus C, Salk R. Radiation dosimetry for the adult female and fetus from iodine-131 administration in hyperthyroidism. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XG, Taranenko V, Zhang J, Shi C. A boundary-representation method for designing whole-body radiation dosimetry models: pregnant females at the ends of three gestational periods - RPI-P3, -P6 and -P9. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:7023–44. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/23/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoriyaz H, dos Santos A, Stabin MG, Cabezas R. Absorbed fractions in a voxel-based phantom calculated with the MCNP-4B code. Med Phys. 2000;27:1555–62. doi: 10.1118/1.599021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi H, Xu XG. Computational anthropomorphic models of the human anatomy: The path to realistic Monte Carlo modeling in radiological sciences. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2007;9:471–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankl M, Petoussi-Henss N, Fill U, Regulla D. The application of voxel phantoms to the internal dosimetry of radionuclides. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2003;105:539–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanzonico PB, Becker DV, Hurley JR. Enhancement of radioiodine treatment of small-pool hyperthyroidism with antithyroid drugs: kinetics and dosimetry. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:2102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Na Y, Caracappa P, Xu X. RPI-AM and RPI-AF, a pair of mesh-based, size-adjustable adult male and female computational phantoms using ICRP-89 parameters and their calculations for organ doses from monoenergetic photon beams. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:5885. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/19/015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]