Summary

Neural circuits are regulated by activity-dependent feedback systems that tightly control network excitability and which are thought to be crucial for proper brain development. Defects in the ability to establish and maintain network homeostasis may be central to the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders. Here we examine the function of the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)-mTOR signaling pathway, a common target of mutations associated with epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder, in regulating activity-dependent processes in the mouse hippocampus. We find that TSC/mTOR is a central component of a positive feedback loop that promotes network activity by repressing inhibitory synapses onto excitatory neurons. In Tsc1 KO neurons, weakened inhibition caused by deregulated mTOR alters the balance of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission leading to hippocampal hyperexcitability. These findings identify the TSC/mTOR pathway as a novel regulator of neural network activity and have implications for the neurological dysfunction in disorders exhibiting deregulated mTOR signaling.

Introduction

To preserve stability during changing environmental conditions and developmental stages, neural networks have intrinsic regulatory mechanisms that maintain activity levels within a bounded range (Davis, 2006). Individual neurons homeostatically regulate their excitability via finely tuned mechanisms that detect and respond to changes in action potential firing and network activity. These include modulation of excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic strength, alterations in neurotransmitter release probability, and adjustment of intrinsic membrane excitability (Marder and Goaillard, 2006; Turrigiano, 2011). These forms of plasticity are thought to be especially important during early post-natal brain development when circuits adapt to the onset and maturation of sensory input. Notably, several neurodevelopmental disorders become manifest during this period of experience-dependent learning and circuit refinement (Zoghbi, 2003), suggesting that disrupted homeostasis may be a contributing factor (Ramocki and Zoghbi, 2008). In fact, a favored hypothesis for autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) is that they arise from imbalanced synaptic excitation and inhibition in specific neural circuits (Bourgeron, 2009; Rubenstein and Merzenich, 2003).

One such neurodevelopmental disorder, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the mTOR negative regulators TSC1 or TSC2 resulting in a constellation of neurological phenotypes that can include epilepsy, autism, and intellectual disability (Prather and de Vries, 2004). The mTOR kinase complex is the central component of a cell growth pathway that responds to changes in nutrients, energy balance, and extracellular signals to control cellular processes including protein synthesis, energy metabolism, and autophagy (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Loss of function of the TSC1/2 protein complex results in deregulated and constitutively active mTOR complex 1, which promotes cell growth and contributes to tumor formation in dividing cells including the hamartomas that are characteristic of TSC (Kwiatkowski and Manning, 2005). However, the ways in which perturbations of TSC1/2-mTOR signaling alter the function of neurons or neural circuits to give rise to the neurological pathologies associated with TSC are not well understood.

Mouse models of TSC exhibit behavioral changes paralleling human disease phenotypes including seizures, decreased social interaction, altered vocalizations, and deficits in learning and memory (Ehninger et al., 2008; Meikle et al., 2007; Tsai et al., 2012; Young et al., 2010). Like other molecules genetically linked to ASDs (Bourgeron, 2009), the TSC-mTOR pathway regulates synapses such that loss of function mutations in Tsc1 or 2 alter excitatory synapse structure, function, and plasticity (Auerbach et al., 2011; Bateup et al., 2011; Chevere-Torres et al., 2012; Ehninger et al., 2008; Tavazoie et al., 2005). Nevertheless, although perturbations of Tsc1/2 and mTOR clearly alter many aspects of neuronal function, given the many homeostatic feedback pathways that influence neural circuit and brain development, it is unclear which perturbations are directly causal and which are induced secondarily as a consequence of altered brain function.

Here we use in vitro and in vivo approaches to determine the cell autonomous and network phenotypes resulting from genetic deletion of Tsc1 in mouse hippocampal neurons, a brain region important for learning and memory that is involved in the generation of temporal lobe seizures (Meador, 2007). We find that loss of Tsc1 results in hippocampal network hyperexcitability manifested by elevated spontaneous activity in dissociated cultures and increased seizure susceptibility in vivo. Prolonged high levels of network activity chronically engage activity-dependent homeostatic pathways that secondarily alter the biochemical, functional, and transcriptional state of neurons in vitro. Network hyperexcitability cannot be attributed to alterations in homeostatic excitatory synaptic plasticity, intrinsic neuronal excitability, or glutamatergic synaptic drive. Rather, hippocampal hyperexcitability likely results from a primary imbalance in excitation and inhibition due to reduced inhibition onto Tsc1 knockout (KO) pyramidal neurons. The loss of inhibition and upregulation of network activity, as well as many of the pursuant secondary responses in Tsc1 KO neurons, can be reversed by treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. These findings support the hypothesis that disrupted excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance is an initiating factor leading to perturbed circuit function in neurodevelopmental disorders.

Results

Network hyperactivity in Tsc1 KO hippocampal cultures

In order to determine how loss of function of the Tsc1/2 complex alters circuit function, we investigated whether genetic deletion of Tsc1 affected the development of hippocampal network activity and the ability of neurons to respond to changes in activity. We examined this in a culture system in which bi-directional manipulation of activity can be accomplished pharmacologically, and biochemical, gene transcriptional, and synaptic analyses can be performed in parallel (Fig. 1). Dissociated hippocampal cultures were prepared from mice carrying conditional alleles of Tsc1 (Tsc1fl/fl) (Kwiatkowski et al., 2002) and infected at two days in vitro (DIV) with a high titer lentivirus encoding, under control of the neuron-specific synapsin promoter, either GFP (control) or GFP-IRES-Cre to delete Tsc1 from all neurons (Tsc1 KO). To address whether loss of Tsc1 affected neural network activity we monitored the development of spontaneous activity in neurons plated onto multi-electrode arrays. Multi-unit activity in control and Tsc1 KO neural networks was measured simultaneously in dual chamber arrays daily over two weeks in culture (Fig. 1A,B). We found that action potential rates were significantly increased in Tsc1 KO networks by 10 DIV and further increased to more than double control levels by 14 DIV (Fig. 1B,C). Activity in the DIV 14 Tsc1 KO cultures displayed a bursting pattern reminiscent of an epileptic-like state (Fig. 1B). The time point when activity in Tsc1 KO neurons began to diverge from control levels corresponded to the time when there was significant loss of Tsc1 protein, assessed by western blotting, and upregulation of mTOR signaling, determined by phosphorylation of the mTOR pathway target ribosomal protein S6 (Fig. 1D). Therefore, loss of Tsc1 has profound effects on the development of hippocampal networks in vitro resulting in severe hyperactivity.

Figure 1. Tsc1 KO hippocampal cultures exhibit an mTOR-dependent increase in spontaneous network activity.

(A) Image of a MED64 dual probe with 32 electrodes per chamber. The dotted circles indicate the approximate plating area (~19 mm2) over the planar electrode arrays, 150 × 150 μm inter-electrode distance. Figure adapted from www.MED64.com.

(B) Example raster plots of multi-unit activity recorded from Tsc1fl/fl hippocampal neurons plated on a dual chamber probe recorded on days 5 and 14 in vitro (DIV). Each line represents a single spike detected in a given channel during 20 seconds of a recording. Neurons plated on the top array (electrodes #1–32) were treated at 2 DIV with a GFP lentivirus (Control, black). Neurons on the bottom array (electrodes #33–64) were treated with GFP-IRES-Cre lentivirus (Tsc1 KO, red). Bottom, example spiking data from one electrode on days 5 and 14 demonstrating a bursting pattern in Tsc1 KO cultures at DIV 14; scale bar = 5 seconds.

(C) Average spike rate per electrode in hertz from control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) cultures across days in vitro (DIV). Lentivirus was added at 2 DIV (arrow). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control on that day. Inset scatter plot shows the average spike rate per electrode on DIV 14 from pairs of control (X axis) and Tsc1 KO (Y axis) cultures (n=15).

(D) Bar graphs display western blot data from Tsc1 KO neurons harvested on the indicated DIV. Black bars represent Tsc1 protein levels (normalized to β-Actin loading control) and grey bars represent phosphorylated S6 levels (p-S6, Ser240/244, normalized to total S6), expressed as a percentage of control levels harvested on the same day (n=4–8). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control on that day. Dashed line at 100% indicates control levels.

(E) Average spike rate per electrode in hertz from control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) neurons across days in vitro (DIV). At 12 DIV, 50 nM rapamycin was added to both sets of cultures (n=5–7). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control on that day. Inset shows the average spike rate on day 12 and day 19 from untreated cultures (dashed lines) and rapamycin treated cultures (solid lines). In black are data from control cultures, in red are data from Tsc1 KO cultures. There was a significant (p<0.05) reduction of spiking activity from day 12 to 19 in the rapamycin treated cultures of both genotypes, denoted by the asterisks.

We tested whether overactive mTOR signaling was responsible for the deregulated activity in Tsc1 KO neurons by applying the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin beginning at 12 DIV. Network activity decreased gradually in rapamycin such that after four days of treatment, activity levels were statistically indistinguishable between the two genotypes (Fig. 1E). Compared to controls, the rapamycin-dependent drop in activity was greater in Tsc1 KO neurons indicating that a larger proportion of spiking activity was mTOR-dependent in the latter condition (Fig. 1E, inset). The decrease in activity following rapamycin was not likely due to cell death as acute treatment with picrotoxin, a drug which blocks inhibitory receptors and increases network activity, was able to robustly increase spiking activity in cultures of both genotypes (Control, 306.1% ± 58% of baseline, p <0.001; Tsc1 KO, 413.1% ± 101.7% of baseline, p<0.01). This indicates that the networks were still responsive and capable of generating high levels of activity after chronic treatment with rapamycin.

Chronic engagement of activity-regulated transcriptional networks in Tsc1 KO neurons

The hyperactivity of Tsc1 KO cultures suggests a defect in the activity-dependent processes that respond to and set network activity levels. To test if loss of Tsc1 affects the ability of neural networks to activate transcriptional programs in response to changes in activity, we performed unbiased microarray analysis of control and Tsc1 KO neurons in different activity states (Fig. 2, Table S1, and Table S2). Network activity was elevated for 1, 6 or 24 hours by receptor antagonist blocking inhibitory neurotransmission with the glycine and GABAA/Cpicrotoxin. Activity was inhibited for the same time periods by blocking action potential firing with the voltage-gated sodium channel antagonist tetrodotoxin (TTX). Three biologically independent samples per condition were collected and analyzed in two batches (basal + 6 hour time points and basal + 1 and 24 hour time points); therefore the heatmap contains two basal state control and Tsc1 KO conditions (Fig. 2A). As expected, the two sets of basal state samples show similar gene expression patterns within the genotype.

Figure 2. Transcriptional profiles of control and Tsc1 KO neurons in different activity states.

(A) Hierarchical clustering of data from microarray analysis of gene expression in control (C) and Tsc1 KO (KO) hippocampal neurons treated with 1 μM TTX or 50 μM picrotoxin (PTX) for the indicated times in hours. Treatment groups with similar patterns of gene expression cluster together as indicated by the dendrogram at the top of the figure. The left cluster includes control neurons in the basal condition and Tsc1 KO neurons treated for ≥ 6 hours with TTX. The right cluster includes basal state Tsc1 KO neurons and picrotoxin-treated control neurons. The heat-map displays the top 250 differential expression profiles across all treatment groups; red indicates higher expression and blue indicates lower expression relative to the median for all groups. Data were obtained from two separate microarray batches; therefore there are two untreated baseline samples for each genotype indicated by the red and black boxes. The numbers on the right denote clusters of genes displaying similar patterns of regulation determined by cluster analysis.

(B) Average log-fold changes in expression for each gene cluster are shown for low, basal, and high network activity conditions across the x axis for control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) cultures. For each gene, fold changes were calculated relative to the average level across conditions, such that no change from the mean results in log=0 (dashed lines). Clusters 1 and 3 contain genes whose levels are up- or down-regulated, respectively, by activity showing constitutive changes in Tsc1 KO networks that are partially reversed by prolonged activity blockade. Cluster 4 contains immediate early genes that are robustly and transiently increased by activity in both control and Tsc1 KO networks. Cluster 2 contains genes up-regulated by loss of Tsc1 in an activity-independent manner. See also Tables S1 and S2.

Hierarchical clustering of the experimental conditions revealed that basal state Tsc1 KO neurons clustered with picrotoxin treated control neurons, denoted by the right cluster in the dendrogram, indicating basal alterations in many activity-regulated genes due to loss of Tsc1. Conversely, prolonged (≥6 hr) activity blockade in Tsc1 KO neurons reversed many of the transcriptional changes such that TTX-treated KO neurons clustered with control neurons in the basal state, shown by the left cluster in the dendrogram (Table S2). Therefore, the majority of transcriptional changes in Tsc1 KO neurons are a consequence of prolonged elevated network activity and not a direct effect of loss of Tsc1.

Cluster analysis of the genes confirmed the presence of constitutively engaged activity-dependent transcriptional programs in Tsc1 KO neurons (Fig. 2A,B). Sets of genes that were up- (Group 1) or down- (Group 3) regulated by long-term elevations in network activity in control neurons showed tonic changes in Tsc1 KO neurons that could be partially reversed by prolonged activity blockade. Additionally, immediate early genes (Group 4) showed rapid and transient induction following acute up-regulation of activity in both Tsc1 KO and control networks. A sub-set of genes (Group 2) were elevated in Tsc1 KO neurons across all activity conditions and showed little or no modulation by activity in control neurons, indicating that these genes are regulated by Tsc1/2-mTOR independently of activity.

Taken together this transcriptional analysis demonstrates that the increased activity of Tsc1 KO networks drives many constitutive secondary changes in gene expression. However, it also reveals that the core transcriptional responses to alterations in network activity are generally preserved in Tsc1 KO neurons.

Tonic up-regulation of Arc and engagement of homeostatic synaptic plasticity in Tsc1 KO cultures

Gene cluster 4 in the microarray data contains immediate early genes that are rapidly induced by activity, including fos, zif268, Homer1, and Arc. Among these, Arc is known to be a mediator of synaptic plasticity, including a type of homeostatic plasticity described in cultured neurons in which chronic decreases or increases in network activity induce neuron-wide up- or down-regulation, respectively, of synaptic glutamate receptors as a means to normalize excitatory drive (Shepherd et al., 2006; Turrigiano et al., 1998). We and others have reported a deficit in another form of Arc-dependent synaptic plasticity, metabotropic glutamate receptor-induced long-term depression (mGluR-LTD), following loss of function of Tsc1 or 2 (Auerbach et al., 2011; Bateup et al., 2011; Chevere-Torres et al., 2012), which may be due to an inability to activate mTOR-dependent translation of Arc mRNA at stimulated synapses (Waung and Huber, 2009). Therefore, we hypothesized that deregulation of mTOR due to loss of Tsc1 could perturb Arc-mediated homeostatic plasticity of excitatory synapses leading to neuronal hyperactivity. To investigate this possibility we examined whether loss of Tsc1 disrupts the activity-dependent production of Arc protein or the ability to down-regulate synaptic glutamate receptors.

Quantification of Arc mRNA levels by RT-PCR confirmed basally high levels in Tsc1 KO neurons and revealed significant bi-directional modulation by activity in a manner similar to control neurons (Fig. 3A). This confirms that the activity-dependent transcriptional pathways that control Arc mRNA production are not perturbed by loss of Tsc1. We next investigated whether signaling through Tsc1/2-mTOR is required for the activity-dependent translation of Arc protein. Consistent with a possible role in this process, the mTOR pathway itself was bi-directionally regulated by activity in control cultures reflected by modulated phosphorylation of S6 following treatment with picrotoxin or TTX (Fig. 3B). In Tsc1 KO cultures, p-S6 was constitutively elevated and no longer responsive to manipulations of network activity (Fig. 3B), indicating that the Tsc1/2 complex is required to relay changes in network activity to targets downstream of mTOR. Nevertheless, the activity-dependent regulation of Arc protein was generally preserved in Tsc1 KO cultures (Fig. 3C). In addition, short-term rapamycin treatment (6 hours) did not affect basal or picrotoxin-induced Arc protein levels in control or Tsc1 KO neurons whereas it reversed activation of the mTOR pathway target S6 (Fig. S1). Thus, in contrast to our hypothesis, the Tsc1/2-mTOR pathway does not directly control the basal or activity-dependent production of Arc.

Figure 3. Activity-dependent homeostatic pathways are tonically engaged in Tsc1 KO cultures.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Arc mRNA levels in control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) hippocampal cultures following treatment with 50 μM picrotoxin or 1 μM TTX for 6 hours (n=2–6).

(B,C) Western blot data of phosphorylated S6 (A) (p-S6 Ser240/244, normalized to total S6) and Arc protein levels (B) (normalized to β-Actin loading control) in control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) cultures following treatment with 50 μM picrotoxin or 1 μM TTX for 6 hours (n=7–20).

(D) Top, representative western blots from a biotin surface-protein labeling experiment. Left lanes are total cell lysates (Input), right lanes are cell surface proteins (Pull-down). C=control, KO=Tsc1 knock-out. Bottom, quantification of surface GluA1 and GluA2 levels from control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) cultures (n=5–7).

(E) Representative traces of miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs) recorded from control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) neurons in culture.

(F,G) Cumulative distributions of mEPSC amplitudes (F) and inter-event intervals (IEI) (G) from control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) neurons in culture (n=9–10).

(H–J) Top, representative western blots of Arc (H), GluA1 (I), and GluA2 (J) protein in control and Tsc1 KO cultures following 7 days of treatment 50 nM with rapamycin. Bottom, bar graphs displaying summary western blot data for Arc (H), GluA1 (I), and GluA2 (J) expressed as a percentage of untreated control (n=9–10). Protein levels were normalized to β-Actin loading control.

Data in bar graphs are represented as mean ± SEM, normalized to the control baseline condition. * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from untreated control; # indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from untreated Tsc1 KO.

See also Figure S1.

Arc mediates homeostatic plasticity by stimulating the removal of glutamate receptors from the synapse; therefore we investigated whether the constitutive upregulation of Arc protein in Tsc1 KO cultures (see Fig. 3C) had an effect on cell surface levels of AMPA-type glutamate receptors. As expected from tonically active Arc-mediated endocytosis, surface levels of the AMPA receptor subunits GluA1 and GluA2 were significantly reduced in Tsc1 KO neurons compared to controls (Fig. 3D). There was also a significant reduction in total levels of GluA1 and GluA2 protein (GluA1: 51.7% ± 3.8% of control, p<0.001; GluA2: 80.6% ± 5.6% of control, p<0.05; n=10–12) indicative of a global down-regulation of glutamate receptors in Tsc1 KO cultures. This was associated with a functional reduction in glutamatergic synaptic strength and number in Tsc1 KO neurons demonstrated by decreased amplitude and number of spontaneous miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs) (Fig. 3E–G). These alterations likely reflected an active homeostatic response to chronically high network activity since both elevated Arc protein levels and the biochemical down-regulation of glutamate receptors could be reversed in Tsc1 KO neurons by restoring activity levels with chronic rapamycin treatment (Fig 3H–J).

These findings indicate that homeostatic mechanisms for regulating excitatory synaptic function are tonically engaged in Tsc1 KO cultures. Therefore a failure to activate these processes cannot account for the network hyperactivity in Tsc1 KO cultures. Taken together with our microarray data, these results also suggest that many alterations observed in Tsc1 KO neurons are actually secondary, compensatory changes resulting from unrestrained activity and not acutely due to elevated mTOR signaling.

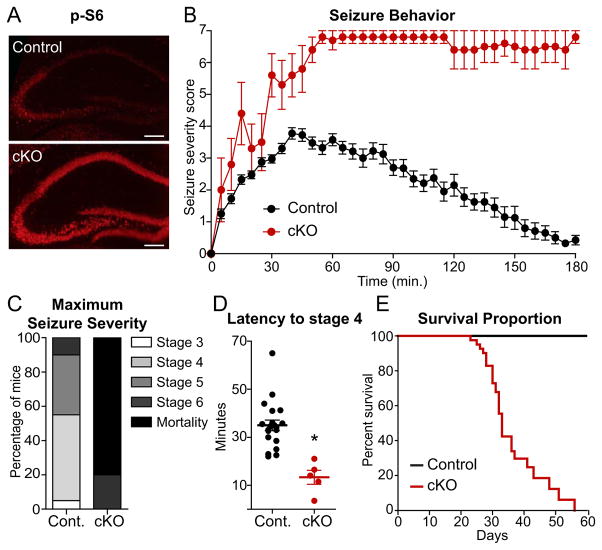

Loss of Tsc1 in forebrain excitatory neurons causes hyperexcitability and seizures

The above results indicate that loss of Tsc1 leads to hyperactivity of hippocampal networks and secondary engagement of homeostatic synaptic plasticity in vitro. However, despite down regulation of synaptic AMPA receptors, network activity remained elevated, suggesting that the primary trigger of hyperexcitability in Tsc1 KO networks cannot be fully compensated by reduced glutamatergic drive. To determine the functional mechanism behind this hyperactivity in a more physiological context, we generated an in vivo model in which Tsc1 was conditionally deleted from excitatory forebrain neurons. To do this, Tsc1fl/fl mice were crossed with mice expressing Cre recombinase from the CamkII α promoter (Tsien et al., 1996). Since Cre expression does not turn on until approximately 21 days of age in these mice, this approach also allows investigation of the effects of perturbed mTOR signaling on network activity in a more mature circuit.

mTOR signaling was elevated in the hippocampus of CamkII α Cre+;Tsc1fl/fl (cKO) mice judged by immunostaining for p-S6 at four weeks of age (Fig. 4A). To determine whether these mice displayed a hyperexcitability phenotype we assessed seizure induction at post-natal day (PND) 29–32 following administration of the convulsant kainic acid. Seizure severity was determined using a previously established rating system (Morrison et al., 1996) with higher values corresponding to more severe seizures and a score of seven indicating death. Over the three hour test period, cKO mice displayed dramatically increased severity of seizures (Fig. 4B) such that 80% of the cKO mice died during the three hour observation period in contrast to zero mortalities among the littermate controls (Fig. 4C). Moreover, Tsc1 cKO mice exhibited significantly decreased latency to reach seizure stage four (forepaw clonus with rearing) (Fig. 4D). The hyperexcitability phenotype in the Tsc1 cKO mice was severe enough that even without experimental manipulation we observed spontaneous seizures in some mice and premature death (Fig. 4E), as reported previously (Ehninger et al., 2008). These findings indicate that selective loss of Tsc1 in excitatory pyramidal neurons causes severe behavioral hyperexcitability, even in the absence of developmental abnormalities.

Figure 4. Loss of Tsc1 in forebrain excitatory neurons increases seizure severity resulting in premature death.

(A) Immunohistochemistry staining for phosphorylated S6 (p-S6, Ser240/244) in hippocampal brain sections from a control (CamkII α Cre+;Tsc1wt/wt) and Tsc1 conditional knock-out mouse (cKO, CamkII αCre+;Tsc1fl/fl) at four weeks of age.

(B) Severity of seizure behavior over time following i.p. injection of 15 mg/kg kainic acid in 4–5 week old Tsc1 cKO (n=5) and littermate control mice (n=20). Higher scores correspond to more severe seizure status; a score of seven indicates mortality. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

(C) Tsc1 cKO mice displayed increased seizure severity demonstrated by a higher percentage of mice with a maximum seizure score of 6 (tonic-clonic seizures) or 7 (mortality) within the 3 hour test period.

(D) Scatterplot summary of the time in minutes to reach seizure stage 4 (forelimb clonus with intermittent rearing) in control and Tsc1 cKO mice. * indicates significant difference (p<0.001) from control.

(E) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for untreated control (CamkIIαCre+;Tsc1wt/wt, n=40) and Tsc1 cKO (CamkIIαCre+;Tsc1fl/fl, n=41) littermate mice.

Loss of Tsc1 does not increase intrinsic excitability or glutamatergic synaptic drive

The network hyperexcitability phenotype we observed both in vitro and in vivo could arise from several possible mechanisms including alterations in intrinsic membrane excitability, synaptically driven excitability, or inhibitory synapse function. Due to the early lethality of the Tsc1 cKO mice and the possible secondary changes in neuronal function due to spontaneous seizures, we investigated these possibilities in acute brain slices from Tsc1fl/fl mice injected with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing a Cre-EGFP fusion protein in the CA1 sub-region of the hippocampus. We diluted the virus to achieve sparse Cre expression and elevation of mTOR signaling in a small number of neurons (Fig. 5A). This allowed examination of cell autonomous perturbations in Tsc1 KO neurons independent of compensatory adaptations from potential network alterations.

Figure 5. Tsc1 KO neurons in acute brain slices show reduced intrinsic excitability but normal synaptically-driven excitability.

(A) Hippocampal section from a Tsc1fl/fl mouse injected with an adeno-associated virus expressing a nuclear targeted Cre-EGFP fusion protein (green, top panel) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, and stained with an antibody against phosphorylated S6 (Ser240/244, red, middle panel). Overlaid image shows elevated phosphorylation of S6 in Cre-expressing neurons. Scale bar = 10 μm.

(B) Example action potential traces from whole cell current clamp recordings of control (Cre-EGFP-, black) and Tsc1 KO (Cre-EGFP+, red) CA1 neurons evoked by one second depolarizing current steps in the presence of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic blockers.

(C,D) Mean ± SEM number of action potentials (C) and latency to first spike (D) in control and Tsc1 KO neurons following injection of depolarizing current steps (n=9–12). * indicates significant difference (p<0.05, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis).

(E) Scatterplot of excitatory post-synaptic potential (EPSP) amplitude in pairs of neighboring control and Tsc1 KO neurons following single stimulation of Schaffer collaterals in the presence of inhibitory synaptic blockers (n=19 pairs). Inset shows overlaid EPSP traces from a pair of neighboring control (black) and Tsc1 KO neurons (red).

(F) Left, example trains of 5 EPSPs evoked by 5 Hz Schaffer collateral stimulation. Right, mean ± SEM EPSP amplitudes for a train of 5 EPSPs showing no differences between control and Tsc1 KO neurons (n=16 pairs).

(G) Left, action potentials evoked by 20 Hz Schaffer collateral stimulation for one second. Right, mean ± SEM number of action potentials evoked by 20 Hz stimulation at 3 different stimulus durations demonstrating no difference between control and Tsc1 KO neurons (n=11 pairs).

It was previously reported that mTOR suppresses dendritic translation of the potassium channel Kv1.1 (Raab-Graham et al., 2006), an effect that could increase burst firing and network synchronization (Cudmore et al., 2010; Metz et al., 2007). To determine whether alterations in intrinsic membrane excitability due to deregulation of ion channels occurred following loss of Tsc1, we performed current clamp recordings in the presence of synaptic blockers and injected depolarizing current to evoke action potentials. Tsc1 KO neurons were less excitable than control neurons demonstrated by reduced action potential firing across the range of current steps (Fig. 5B,C), increased latency to first spike (Fig. 5D), and increased action potential threshold (Control, −47.7 ± 1.6 mV; Tsc1 KO, −41.9 ± 1.9 mV; p<0.05). Action potential height and half-width were not significantly different between the two genotypes (Control half-width, 0.91 ± 0.02 ms, height, 89.5 ± 2.5 mV; Tsc1 KO half-width, 0.95 ± 0.05 ms, height 84.6 ± 2.5 mV). As reported previously (Bateup et al., 2011), membrane resistance and capacitance were decreased and increased, respectively, in Tsc1 KO neurons (Control Rm 167.7 ± 5.5 mΩ, Cm 81.7 ± 2.6 pF; Tsc1 KO Rm 127.0 ± 10.9 mΩ, p<0.01, Cm 115.7 ± 10.2 pF, p<0.01), which was likely responsible for the reduced excitability to current injection. These results are in agreement with recent studies reporting reduced spontaneous activity and intrinsic excitability following loss of Tsc1 in cerebellar and hypothalamic neurons (Tsai et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012).

These findings indicate that a cell autonomous increase in pyramidal cell excitability cannot account for the network hyperactivity phenotype following loss of Tsc1. However, hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells fire sparsely in vivo and are largely driven by synaptic inputs. We previously showed that in the sparse deletion condition, Tsc1 KO neurons have enhanced evoked glutamatergic synaptic currents, possibly resulting from a deficit in mGluR-LTD (Bateup et al., 2011). To determine whether these larger synaptic currents enhance excitatory synaptic potentials or synaptically-driven firing, we performed current clamp recordings of neighboring pairs of control and Tsc1 KO neurons while stimulating Schaffer collateral axons at different frequencies. There was no significant difference in the amplitude of excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) following either a single stimulation or a 5 Hz train (Fig. 5E,F). Furthermore, no differences in firing frequency were observed following 20 Hz stimulation at three different stimulus intensities (Fig. 5G). We did, however, observe a significant decrease in the resting membrane potential of Tsc1 KO neurons compared to controls (Control -66.6 ± 1.0 mV, Tsc1 KO −69.1 ± 1.2 mV, p<0.05). These results demonstrate that the increased glutamatergic synaptic currents we observed previously (Bateup et al., 2011) are largely canceled out by the reduced intrinsic excitability such that there is no net change in glutamatergic synapse-driven excitability in isolated Tsc1 KO neurons. Taken together with the reduction in glutamatergic synapses we observed in the highly active cultures (see Fig. 3), this indicates that an enhancement of excitatory synaptic drive does not account for the network hyperexcitability caused by loss of Tsc1.

Loss of Tsc1 reduces inhibitory synaptic transmission

In addition to intrinsic neuronal firing rate and excitatory synaptic drive, neural network activity is dependent upon inhibition, which controls overall activity level, shapes the temporal pattern of activity, and limits bursting (Isaacson and Scanziani, 2011; Kullmann, 2011). To assess the strength and number of inhibitory synapses onto CA1 pyramidal neurons, we recorded spontaneous miniature inhibitory synaptic currents (mIPSCs) following sparse loss of Tsc1. Both mIPSC amplitude and inter-event interval were significantly reduced in Tsc1 KO neurons, which is indicative of reduced ionotropic GABA receptor content per synapse but a greater number of inhibitory synapses (Fig. 6A–C). We determined how these alterations affected evoked inhibition by recording IPSCs in pairs of neighboring control and Tsc1 KO neurons following stimulation of interneurons in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer. Ionotropic glutamate receptors were blocked to allow direct activation of inhibitory interneurons and to evoke monosynaptic IPSCs. We found a significant reduction in the amplitude of evoked inhibitory currents in Tsc1 KO neurons relative to controls (Fig. 6D). Consistent with the decreased mIPSC amplitude, this effect was likely due to a change in post-synaptic function as there were no differences between control and Tsc1 KO neurons in paired pulse ratios, which are a measure of pre-synaptic release probability at inhibitory synapses (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Decreased amplitude of inhibitory synaptic currents in Tsc1 KO neurons.

(A) Example recordings of miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents (mIPSCs) from control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) CA1 neurons from an acute brain slice.

(B,C) Cumulative distributions of mIPSC amplitudes (B) and inter-event intervals (IEI) (C) from control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) neurons (n=11–12). Insets show scatterplot summaries of cell averages; horizontal lines indicate the mean and error bars denote SEM. * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control.

(D) Left, scatterplot of evoked IPSC amplitude in pairs of neighboring control and Tsc1 KO neurons following stimulation of the CA1 pyramidal cell layer with excitatory synaptic transmission blocked (n=16 pairs). Inset shows overlaid IPSC traces from a pair of neighboring control (black) and Tsc1 KO neurons (red). Scale bar = 25 ms ×100 pA. Right, mean ± SEM evoked IPSC amplitude in control and Tsc1 KO neurons. * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control.

(E) Left, representative overlaid traces for sets of two IPSCs evoked by stimuli delivered at different inter-stimulus intervals (ISI). Right, mean ± SEM paired pulse ratios of IPSCs from neighboring control and Tsc1 KO neurons at different ISIs (n=14 pairs) demonstrating no difference between genotypes.

These results indicate that loss of Tsc1 in CA1 pyramidal neurons causes a cell autonomous weakening of inhibitory inputs, which could result in hyperexcitability at the network level. To determine whether reduced inhibition persists when there is more widespread loss of Tsc1, we injected a high concentration of the Cre-EGFP-expressing virus to delete Tsc1 from >90% of CA1 neurons on one side of the brain (Fig. 7A and S2). This resulted in robust activation of mTOR signaling in area CA1 (Fig. S2), but likely due to the unilateral and spatially confined nature of the manipulation, did not induce spontaneous seizures. Comparison of Tsc1 KO neurons from the injected hemisphere to control neurons from the uninjected hemisphere revealed a significant reduction in mIPSC amplitude due to loss of Tsc1 (Fig. 7A,B). Moreover, and in contrast to our findings following sparse loss of Tsc1 (see Fig. 6C), the inter-event interval (IEI) of mIPSCs was significantly increased after widespread deletion of Tsc1 (Fig. 7C), which is indicative of a reduction in inhibitory synapse number. These changes in inhibitory synaptic transmission could be due to alterations in pre-synaptic inhibitory interneurons, post-synaptic pyramidal neurons, or both. We found that the AAV serotype 1 used to deliver Cre either did not infect or did not express in interneurons of the hippocampus (Fig. S3), suggesting that the changes in inhibitory synapse strength and number were likely due to alterations in post-synaptic pyramidal cells. To determine if synapse loss was specific to inhibitory synapses, we measured miniature excitatory synaptic currents following the same widespread loss of Tsc1 in area CA1. We found no significant changes in mEPSC amplitude or IEI between neurons of the two genotypes (Fig. 7D–F). This is in contrast to the down-regulation of mEPSCs we observed in the highly active Tsc1 KO cultures (see Fig. 3). Since our in vivo manipulation only affected post-synaptic CA1 neurons on one side of the brain, it is possible that network activity was not elevated enough to engage homeostatic synaptic scaling under these conditions.

Figure 7. Excitatory-inhibitory synaptic imbalance in Tsc1 KO neurons.

(A) Top, a high titer adeno-associated virus expressing a nuclear localized Cre-EGFP fusion protein was stereotaxically injected unilaterally into the CA1 region to delete Tsc1 from >90% of neurons (“widespread knock-out”). Scale bar = 100 μm. Bottom, example recordings of miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents (mIPSCs) from a control neuron (black) in the uninjected hemisphere and a Tsc1 KO neuron (red) in the injected hemisphere.

(B,C) Cumulative distributions of mIPSC amplitudes (B) and inter-event intervals (IEI) (C) from control neurons in the uninjected hemisphere and Tsc1 KO neurons in the injected hemisphere (n=12). Insets show scatterplot summaries of cell averages; horizontal lines indicate the mean and error bars denote SEM. * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control.

(D) Example recordings of miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs) from a control neuron (black) in the uninjected hemisphere and a Tsc1 KO neuron (red) in the injected hemisphere following widespread injection of Cre.

(E,F) Cumulative distributions of mEPSC amplitudes (E) and inter-event intervals (IEI) (F) from control neurons in the uninjected hemisphere and Tsc1 KO neurons in the injected hemisphere (n=11–14). Insets show scatterplot summaries of cell averages demonstrating no difference between genotypes; horizontal lines indicate the mean and error bars denote SEM.

(G) Scatterplot of excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) ratio in pairs of neighboring control and Tsc1 KO neurons following sparse deletion of Tsc1 (“sparse knock-out”, as in Fig. 5A). Inset shows mean ± SEM E/I ratio in cells of both genotypes (n=13 pairs). * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control.

(H) Sparse knock-out. Left, overlaid traces of compound excitatory (EPSP) and inhibitory (IPSP) post-synaptic potentials evoked by Schaffer collateral stimulation in a neighboring pair of control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) neurons. Dashed line indicates the baseline. Right, mean ± SEM EPSP and IPSP amplitude in control and Tsc1 KO neurons (n=13 pairs). * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control.

(I) Widespread knock-out. Left, example traces of compound post-synaptic potentials evoked by Schaffer collateral stimulation in a control neuron in the uninjected hemisphere (black) and a Tsc1 KO neuron in the injected hemisphere (red) following widespread unilateral injection of Cre. Dashed lines indicate the baseline. Right, mean ± SEM EPSP and IPSP amplitude in control and Tsc1 KO neurons (n=8–9). * indicates significant difference (p<0.05) from control.

(J) Sparse knock-out. Mice were injected daily with 5 mg/kg rapamycin for six days prior to and on the day of electrophysiological analysis. Top, overlaid recordings of compound post-synaptic potentials evoked by Schaffer collateral stimulation in a neighboring pair of control (black) and Tsc1 KO (red) neurons. Dashed line indicates the baseline. Bottom, mean ± SEM of EPSP and IPSP amplitude after seven days of treatment with rapamycin demonstrating no difference between control and Tsc1 KO neurons (n=8 pairs). See also Figures S2–4.

The above data, based on measurements of spontaneous excitatory and inhibitory transmission in different populations of neurons, suggest an imbalance in excitation and inhibition following loss of Tsc1. To determine whether loss of Tsc1 causes E/I imbalance in individual Tsc1 KO neurons following stimulation of the local circuit, current clamp recordings were used to measure compound synaptic potentials elicited by Schaffer collateral stimulation. This analysis was performed in the absence of synaptic blockers to allow activation of both excitatory and inhibitory synapses. We performed these experiments first in the sparse deletion condition to allow direct comparison of synaptic potentials in neighboring pairs of control and Tsc1 KO neurons evoked by the same stimulus. In support of our hypothesis, loss of Tsc1 resulted in a significant increase in the E/I ratio in Tsc1 KO neurons relative to controls (Fig. 7G) that was primarily due to a decrease in the amplitude of inhibitory hyperpolarizing potentials (Fig. 7H). This imbalance persisted and was exacerbated following widespread loss of Tsc1 in CA1 neurons (Fig. 7I), consistent with our mIPSC findings.

In Tsc1 KO cultures, network hyperactivity could be restored with chronic rapamycin treatment. To test whether mTOR blockade in vivo could reverse the E/I imbalance in Tsc1 KO neurons, we treated mice with rapamycin for seven days prior to electrophysiological analysis. We confirmed that this treatment resulted in reduced mTOR signaling in the hippocampus (Fig. S4). We found that rapamycin was sufficient to normalize E/I ratios (Control, 1.83 ± 0.31; Tsc1 KO, 1.43 ± 0.52; p=0.31) by restoring inhibitory synaptic function in Tsc1 KO neurons (Fig. 7J). Taken together, these data indicate that post-natal loss of function of the Tsc1/2 complex in CA1 pyramidal neurons results in decreased inhibitory synapse function and enhanced E/I ratio; alterations that can be reversed by chronically inhibiting mTOR signaling with rapamycin.

Discussion

A major question concerning neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism is at what level the mutations in the diverse molecules genetically associated with these disorders converge to produce a common set of behavioral abnormalities. Disrupted network homeostasis has been proposed as a pathophysiology contributing to autism spectrum disorders (Ramocki and Zoghbi, 2008). This could be caused by perturbations in synaptic E/I balance, as the protein products of many genes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders regulate aspects of synaptic function (Bourgeron, 2009; Kelleher and Bear, 2008). In this study we addressed this possibility using molecular, biochemical, behavioral, and electrophysiological approaches in in vitro and in vivo mouse models of the epilepsy- and autism-associated disorder TSC. Our goal was to link molecular and biochemical alterations associated with loss of Tsc1 to changes in synaptic and neuronal function to determine how deregulated mTOR signaling affects the ability to maintain balanced hippocampal network activity. Our results demonstrate a primary defect in inhibition onto pyramidal neurons resulting in enhanced E/I ratio and dramatically elevated hippocampal network excitability both in vitro and in vivo. This increased activity caused a number of secondary alterations including tonic activation of homeostatic excitatory synaptic plasticity in cultures, which surprisingly, was unable to normalize network activity. Importantly, the loss of inhibition occurred following cell autonomous deregulation of mTOR signaling and therefore could be an initiating mechanism that drives the network to an unstable state.

The mTOR pathway as a regulator of E/I balance and hippocampal network excitability

We demonstrate that loss of Tsc1 in CA1 pyramidal neurons results in a deficit in inhibitory synaptic function manifested by decreased amplitude of spontaneous miniature inhibitory currents, reduced evoked inhibitory currents, and reduced synaptic inhibitory potentials. Reduced inhibition is due to loss of Tsc1 in the post-synaptic pyramidal neuron as inhibitory interneurons did not express Cre under our conditions, and we did not observe changes in pre-synaptic release probability. Whether the Tsc1/2-mTOR pathway is a regulator of global inhibition by modulating numbers or trafficking of GABA receptors, or whether our findings are specific to sub-classes of inhibitory synapses in the hippocampus are questions for future investigation. Notably, the reduction in inhibition is reversed by blocking mTOR suggesting that amelioration of the signaling perturbation can restore synaptic balance.

Our data indicate that a primary deficit in inhibition onto pyramidal neurons is sufficient to alter E/I balance. However, TSC is caused by germ-line mutations affecting all cells, and therefore it is possible that perturbations in inhibitory neuron function or glia could also contribute to the pathogenesis of seizures in humans with the disease. In line with this, loss of Tsc1/2 in glia has been shown to perturb glutamate transport (Wong et al., 2003), which would further exacerbate hyperexcitability in an unbalanced network.

Our findings in Tsc1 KO hippocampal cultures indicate that mTOR signaling is both upregulated by activity and promotes activity at the network level. Thus, mTOR may act as a positive feedback regulator of network excitability. In support of this, in a rodent model of temporal lobe epilepsy independent of TSC, mTOR signaling was both stimulated by seizure activity and contributed to subsequent epileptogenesis (Zeng et al., 2009). Such a positive feedback pathway might be beneficial during the development of neural circuits. For example, a gradual positive feedback system that allows neurons to incrementally increase their excitability in proportion to their network drive would allow the contribution of an individual neuron to the network to increase as it becomes functionally incorporated. The ability to down-regulate inhibition could also be a way to promote synaptic potentiation and enhance learning and memory, as recently demonstrated for the translational regulatory kinase PKR (Zhu et al., 2011). It is vital that such a mechanism be tightly regulated, as even a small imbalance will have severe consequences for network function. We find that the Tsc1/2 complex is required for the activity-dependent regulation of mTOR signaling. Therefore, it likely provides the brake that normally prevents runaway activation of mTOR.

Primary versus secondary alterations

A complexity in the analysis of mouse models of human neurological disease is the multiple levels at which changes in the activity of individual cells and networks induce secondary, compensatory alterations. For this reason, any primary defect that alters cellular excitability will lead to a myriad of downstream changes and it is often difficult to identify the primary alteration directly caused by the mutation. To attempt to disambiguate these processes, we performed our analyses in low, basal, and high network activity states and compared the changes induced by loss of Tsc1 in a sparse number versus in the majority of hippocampal CA1 neurons.

Our findings in networks of cultured neurons indicate that many biochemical, transcriptional, and functional changes in Tsc1 KO neurons arise secondarily due to increased network activity. For example, chronically high firing rates caused constitutive transcriptional activation of immediate early genes such as Arc, a central mediator of homeostatic excitatory synaptic plasticity (Shepherd et al., 2006). For this reason, hyperexcitable Tsc1 KO networks may appear to have a dysfunctional homeostat; however, we find that the activity-dependent induction of the Arc gene, production of the Arc protein, and down-regulation of surface AMPA receptors occur independently of mTOR and are intact in Tsc1 KO cultures. Instead, these processes appear to be constitutively engaged in vitro because reduced glutamatergic synaptic function is unable to compensate for the primary change in activity.

Using viral delivery of Cre in vivo to delete Tsc1 from the majority of CA1 neurons, we did not observe significant changes in glutamatergic synapse strength or number. This is most likely due to differences in activity levels between the dissociated cultures and the hippocampus in vivo. In the dissociated cultures, all neurons have deletion of Tsc1 and activity is very high, whereas in the viral model, we delete Tsc1 from post-synaptic CA1 neurons on one side of the brain only. Therefore, global hippocampal network activity may not be increased enough to drive homeostatic changes in glutamatergic synapses. Alternatively, homeostatic synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus has largely been studied in vitro and it is possible that this type of global scaling is not as readily expressed at later ages in the hippocampus in vivo. Regardless of the differences between the two systems, in neither case is glutamatergic transmission enhanced, therefore we can conclude that changes in excitatory synaptic strength do not account for hippocampal network hyperexcitability following loss of Tsc1.

The change we observed that most plausibly accounts for network hyperactivity was a weakening of inhibition. This occurred cell autonomously and was exacerbated following widespread loss of Tsc1 such that half of pyramidal neurons exhibited a near complete loss of functional inhibitory synapses. Therefore, disrupted inhibitory synaptic transmission is likely a primary consequence of altered Tsc1/2-mTOR signaling which cannot be effectively counterbalanced. Because appropriate inhibition is integral to circuit function, this could indeed account for the network hyperexcitability following loss of Tsc1.

Relevance to neurodevelopmental disorders

The increased network activity observed after loss of Tsc1 in mouse hippocampal neurons has clear relevance for the high prevalence of epilepsy observed in TSC patients (Thiele, 2010). Our data from mouse models suggests that an mTOR-dependent loss of inhibition could be a contributing factor. In line with this, recent clinical studies analyzing tissue samples from TSC patients have reported alterations in inhibitory receptors, specifically decreased benzodiazepine binding and reduced expression of the α1 GABAA receptor subunit in the cortex (Mori et al., 2012; Talos et al., 2012). The fact that we were able to reverse both the increased network activity and E/I imbalance with rapamycin after dysfunction had already occurred strongly suggests that mTOR may be a useful therapeutic target even after the onset of seizures. Furthermore, it supports the idea that TSC is an mTOR-overactivation syndrome whereby neuronal and network dysfunction can contribute to disease phenotypes independent of the structural brain abnormalities observed in patients (de Vries, 2010). Lastly, the fact that mTOR regulates inhibition supports the idea that rapamycin may be effective in other forms of epilepsy not associated with mutations in TSC1 or 2 (McDaniel and Wong, 2011; Wong and Crino, 2012).

There is a clear clinical link between ASDs and epilepsy, and reduced GABAergic inhibition may be a common pathophysiological mechanism (Hussman, 2001). One third of ASD patients develop seizures (Gillberg and Billstedt, 2000), and more than 60% of autistic children have epileptiform activity in EEG recordings suggestive of unstable cortical networks (Spence and Schneider, 2009). TSC1 and 2 were recently shown to be susceptibility genes in non-syndromic autism, independent of TSC (Kelleher et al., 2012). Therefore, E/I imbalance resulting from deregulated Tsc1/2-mTOR signaling may contribute to autistic phenotypes as well. Notably, another autism spectrum disorder with a high prevalence of epilepsy, Fragile X Syndrome (FXS), has also been associated with reduced functional inhibition (Paluszkiewicz et al., 2011). This suggests that despite differences in the molecular mechanisms, the pathophysiology of these disorders could converge at the level of altered E/I balance.

Experimental Procedures

Dissociated hippocampal cultures

Primary dissociated hippocampal cultures were prepared from P0–1 Tsc1fl/fl mice (Kwiatkowski et al., 2002) using standard protocols. On DIV 2, lentivirus expressing either GFP or GFP-IRES-Cre from the synapsin promoter was added. For biochemical experiments 1.8–2 × 105 cells were plated onto 24-well plates pre-coated with Poly-D-Lysine (PDL). For multi-electrode array recordings, neurons were plated onto MED64 dual-chamber probes (MED-P5D15A) pre-coated with PDL and laminin at a density of ~4.2×103 cells/mm2.

Multi-electrode Array Recordings

2–5 minute recordings were performed daily with a MED64 Multi-electrode Array System using a Panasonic 64-channel amplifier and Mobius software (AutoMate Scientific). Spikes were detected using Mobius software with the threshold set at +/− 0.009mV (≥ 2 fold the baseline noise).

Microarray preparation and data analysis

Dissociated hippocampal cultures were prepared from Tsc1fl/fl mice and treated at 14 DIV with 50 μM picrotoxin or 1 μM TTX for 0, 1, 6, or 24 hours. RNA was prepared using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and submitted to the Microarray Core at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in biologic triplicate for each condition. Samples were submitted in two separate batches on two dates. The first set contained baseline and 6 hour time points and the second set contained baseline, 1 and 24 hour time points for each genotype. See supplemental information for details of microarray analysis.

Seizure behavior

Male and female littermates were housed on a reverse light-dark cycle and tested for seizure behavior in the dark phase on PND 29–32. Seizures were induced by i.p. administration of 15 mg/kg kainic acid. Seizures were video recorded for three hours and behaviors were scored by two independent observers blinded to genotype on a 0–7 rating scale as previously described (Morrison et al., 1996).

Stereotaxic injections

Unilateral injections into the CA1 region of the hippocampus were made at A/P −3.0 mm, M/L −3.4 mm, and D/V −2.3 mm relative to Bregma with 1 μL of an AAV serotype 1 Cre-EGFP-expressing virus (Lu et al., 2009) (1.2×1013 genome copy/ml) in P14–16 mice. To achieve sparse infection the virus was diluted 10–20 times in 1x PBS. Mice were used for experiments 11–14 days following the virus injection.

Electrophysiology

Recordings from dissociated cultures. Hippocampal neurons from Tsc1fl/fl mice were plated onto PDL-coated glass coverslips and treated at 2 DIV with either GFP or GFP-IRES-Cre lentivirus. To record mEPSCs, coverslips were perfused with ACSF including (in μM) 10 CPP, 1 TTX, and 10 gabazine. For all voltage clamp recordings, ~3 MΩ recording pipettes were filled with cesium-based internal solution and cells were held at −70 mV.

Recordings from acute brain slices. Hippocampal slices from P25–32 virus-injected Tsc1fl/fl mice were cut in ice-cold choline-based external solution and transferred to ACSF. To measure mIPSCs, the external solution contained (in μM) 1 TTX, 10 CPP, and 10 NBQX. For evoked IPSC recordings, paired voltage-clamp recordings were obtained from neighboring CreEGFP-positive and CreEGFP-negative CA1 neurons in external solution containing (in μM) 10 NBQX, 10 CPP, and 500 AIDA. The pyramidal cell body layer was stimulated to evoke IPSCs.

Current clamp recordings were performed at 32°C using potassium-based internal solution. To measure intrinsic excitability, the membrane potential was held at −70mV and depolarizing current steps were given in the presence of (in μM) 10 NBQX, 10 CPP, and 50 picrotoxin to block synaptic transmission. For the synaptic excitability experiments, paired recordings were obtained from neighboring CreEGFP-positive and CreEGFP-negative neurons without adjustment of the membrane potential and inhibition was blocked with 50 μM picrotoxin and 0.4 μM CGP55845. Excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) and action potentials were evoked by Schaffer collateral stimulation at 5, 20, or 50 Hz for one second. To measure E/I ratio, current clamp recordings from paired (sparse knock-out) or single neurons (widespread knock-out) were made in the absence of synaptic blockers. Schaffer collaterals were stimulated to evoke both monosynaptic EPSPs and compound di-synaptic/monosynaptic inhibitory post-synaptic potentials (IPSPs). See supplemental information for detailed methods.

Statistical Analysis

For comparisons between two groups, unpaired or paired two-tailed student’s t-tests were used. If the variance between groups was significantly different, a Welch’s correction was used. For comparisons between multiple groups, a one- or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis was used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Sabatini lab for helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NINDS grant NS052707 to B.L.S. and a Nancy Lurie Marks Postdoctoral Fellowship to H.S.B.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Auerbach BD, Osterweil EK, Bear MF. Mutations causing syndromic autism define an axis of synaptic pathophysiology. Nature. 2011;480:63–68. doi: 10.1038/nature10658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateup HS, Takasaki KT, Saulnier JL, Denefrio CL, Sabatini BL. Loss of Tsc1 in vivo impairs hippocampal mGluR-LTD and increases excitatory synaptic function. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8862–8869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1617-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeron T. A synaptic trek to autism. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevere-Torres I, Kaphzan H, Bhattacharya A, Kang A, Maki JM, Gambello MJ, Arbiser JL, Santini E, Klann E. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression is impaired due to elevated ERK signaling in the DeltaRG mouse model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudmore RH, Fronzaroli-Molinieres L, Giraud P, Debanne D. Spike-time precision and network synchrony are controlled by the homeostatic regulation of the D-type potassium current. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12885–12895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0740-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW. Homeostatic control of neural activity: from phenomenology to molecular design. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:307–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries PJ. Targeted treatments for cognitive and neurodevelopmental disorders in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehninger D, Han S, Shilyansky C, Zhou Y, Li W, Kwiatkowski DJ, Ramesh V, Silva AJ. Reversal of learning deficits in a Tsc2+/− mouse model of tuberous sclerosis. Nat Med. 2008;14:843–848. doi: 10.1038/nm1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C, Billstedt E. Autism and Asperger syndrome: coexistence with other clinical disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:321–330. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102005321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussman JP. Suppressed GABAergic inhibition as a common factor in suspected etiologies of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:247–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1010715619091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011;72:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ, 3rd, Bear MF. The autistic neuron: troubled translation? Cell. 2008;135:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ, 3rd, Geigenmuller U, Hovhannisyan H, Trautman E, Pinard R, Rathmell B, Carpenter R, Margulies D. High–throughput sequencing of mGluR signaling pathway genes reveals enrichment of rare variants in autism. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM. Interneuron networks in the hippocampus. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Manning BD. Tuberous sclerosis: a GAP at the crossroads of multiple signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(Spec No 2):R251–258. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Zhang H, Bandura JL, Heiberger KM, Glogauer M, el-Hashemite N, Onda H. A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex-dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up-regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:525–534. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Shi Y, Jackson AC, Bjorgan K, During MJ, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Nicoll RA. Subunit composition of synaptic AMPA receptors revealed by a single-cell genetic approach. Neuron. 2009;62:254–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Goaillard JM. Variability, compensation and homeostasis in neuron and network function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:563–574. doi: 10.1038/nrn1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SS, Wong M. Therapeutic role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition in preventing epileptogenesis. Neurosci Lett. 2011;497:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador KJ. The basic science of memory as it applies to epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 9):23–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle L, Talos DM, Onda H, Pollizzi K, Rotenberg A, Sahin M, Jensen FE, Kwiatkowski DJ. A mouse model of tuberous sclerosis: neuronal loss of Tsc1 causes dysplastic and ectopic neurons, reduced myelination, seizure activity, and limited survival. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5546–5558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5540-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz AE, Spruston N, Martina M. Dendritic D-type potassium currents inhibit the spike afterdepolarization in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2007;581:175–187. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Mori T, Toda Y, Fujii E, Miyazaki M, Harada M, Kagami S. Decreased benzodiazepine receptor and increased GABA level in cortical tubers in tuberous sclerosis complex. Brain Dev. 2012;34:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison RS, Wenzel HJ, Kinoshita Y, Robbins CA, Donehower LA, Schwartzkroin PA. Loss of the p53 tumor suppressor gene protects neurons from kainate-induced cell death. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1337–1345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01337.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluszkiewicz SM, Martin BS, Huntsman MM. Fragile X syndrome: the GABAergic system and circuit dysfunction. Dev Neurosci. 2011;33:349–364. doi: 10.1159/000329420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather P, de Vries PJ. Behavioral and cognitive aspects of tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:666–674. doi: 10.1177/08830738040190090601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab-Graham KF, Haddick PC, Jan YN, Jan LY. Activity- and mTOR-dependent suppression of Kv1.1 channel mRNA translation in dendrites. Science. 2006;314:144–148. doi: 10.1126/science.1131693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramocki MB, Zoghbi HY. Failure of neuronal homeostasis results in common neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Nature. 2008;455:912–918. doi: 10.1038/nature07457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JL, Merzenich MM. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:255–267. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JD, Rumbaugh G, Wu J, Chowdhury S, Plath N, Kuhl D, Huganir RL, Worley PF. Arc/Arg3.1 mediates homeostatic synaptic scaling of AMPA receptors. Neuron. 2006;52:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SJ, Schneider MT. The role of epilepsy and epileptiform EEGs in autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:599–606. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000352115.41382.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talos DM, Sun H, Kosaras B, Joseph A, Folkerth RD, Poduri A, Madsen JR, Black PM, Jensen FE. Altered inhibition in tuberous sclerosis and type IIb cortical dysplasia. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:539–551. doi: 10.1002/ana.22696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie SF, Alvarez VA, Ridenour DA, Kwiatkowski DJ, Sabatini BL. Regulation of neuronal morphology and function by the tumor suppressors Tsc1 and Tsc2. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1727–1734. doi: 10.1038/nn1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele EA. Managing and understanding epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsia. 2010;51(Suppl 1):90–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai PT, Hull C, Chu Y, Greene-Colozzi E, Sadowski AR, Leech JM, Steinberg J, Crawley JN, Regehr WG, Sahin M. Autistic-like behaviour and cerebellar dysfunction in Purkinje cell Tsc1 mutant mice. Nature. 2012;488:647–651. doi: 10.1038/nature11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. Too many cooks? Intrinsic and synaptic homeostatic mechanisms in cortical circuit refinement. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:89–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature. 1998;391:892–896. doi: 10.1038/36103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waung MW, Huber KM. Protein translation in synaptic plasticity: mGluR-LTD, Fragile X. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Crino PB. mTOR and Epileptogenesis in Developmental Brain Malformations. In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV, editors. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies. Bethesda (MD): 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Ess KC, Uhlmann EJ, Jansen LA, Li W, Crino PB, Mennerick S, Yamada KA, Gutmann DH. Impaired glial glutamate transport in a mouse tuberous sclerosis epilepsy model. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:251–256. doi: 10.1002/ana.10648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SB, Tien AC, Boddupalli G, Xu AW, Jan YN, Jan LY. Rapamycin ameliorates age-dependent obesity associated with increased mTOR signaling in hypothalamic POMC neurons. Neuron. 2012;75:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DM, Schenk AK, Yang SB, Jan YN, Jan LY. Altered ultrasonic vocalizations in a tuberous sclerosis mouse model of autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11074–11079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005620107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng LH, Rensing NR, Wong M. The mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway mediates epileptogenesis in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6964–6972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0066-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu PJ, Huang W, Kalikulov D, Yoo JW, Placzek AN, Stoica L, Zhou H, Bell JC, Friedlander MJ, Krnjevic K, et al. Suppression of PKR promotes network excitability and enhanced cognition by interferon-gamma-mediated disinhibition. Cell. 2011;147:1384–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi HY. Postnatal neurodevelopmental disorders: meeting at the synapse? Science. 2003;302:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1089071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.