Abstract

Organelles within the endomembrane system are connected via vesicle flux. Along the endocytic pathway, endosomes are among the most versatile organelles. They sort cargo through tubular protrusions for recycling or through intraluminal vesicles for degradation. Sorting involves numerous machineries, which mediate fission of endosomal transport intermediates and fusion with other endosomes or eventually with lysosomes. Here we review the recent advances in our understanding of these processes with a particular focus on the Rab GTPases, tethering factors, and retromer. The cytoskeleton has also been recently recognized as a central player in membrane dynamics of endosomes, and this review covers the regulation of the machineries that govern the formation of branched actin networks through the WASH and Arp2/3 complexes in relation with cargo recycling and endosomal fission.

Endosomal sorting involves numerous machineries (e.g., Rab GTPases, tethering factors, and retromer) that mediate fission of the endosomal membrane and fusion with other endosomes or eventually with lysosomes.

The endomembrane system of eukaryotic cells allows cells to secrete and take up proteins and lipids without perturbing the cytosolic environment or other organelles. This is possible because proteins that have been initially inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum remain within the lumen of organelles of the endomembrane system and are transported between organelles via vesicular carriers. These carriers, usually vesicles, form during a budding process at one organelle and then fuse with their target organelle to deliver their luminal content. This general transport process to deliver cargo applies for both the endocytic pathway and the secretory pathway, which includes the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi as organelles (Bonifacino and Glick 2004).

Endocytosis begins at the plasma membrane, where selected transmembrane proteins such as amino acid transporters or growth factor receptors are sorted into endocytic vesicles. Vesicles are released by scission from the plasma membrane and then fuse with the early endosome. This organelle serves as a sorting platform, where the fate of endocytosed proteins is decided (Huotari and Helenius 2011). They can be either sorted into tubular extensions, which separate from the endosomes and deliver the protein back to the plasma membrane, or are funneled into the endosomal lumen within intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) along the degradation pathway. These sorting processes require fission of the endosomal membrane. During these processes, endosomes change their appearance and converge from a structure with tubular extensions into a round multivesicular endosome with multiple ILVs. Furthermore, endosomes continue to fuse with themselves or with vesicles, which arrive from the Golgi and deliver lysosomal hydrolases. Homotypic fusion is essential to generate sufficient membrane surface for the ILV formation. Furthermore, Maxfield and colleagues suggested early on that endosomal fusion and fission are necessary to sort selected membrane proteins into intraluminal vesicles of late endosomes, while allowing bulk membranes and receptors to be recycled back to the plasma membrane. This process, which was termed “geometric sorting” (Mayor et al. 1993), could explain the existence of recycling endosomes as well as the need of fusion and fission at the level of the early endosome to concentrate cargo proteins for their degradation in the lysosomal lumen (Huotari and Helenius 2011). In the course of the morphological transition of endosomes, which is called endosomal maturation, endosomes also change their membrane surface composition to become competent for fusion with the lysosome. Before fusion between the late endosome and lysosome, cargo-sorting receptors that were initially bound to luminal hydrolases are sorted in tubular structures, which pinch off from the endosome and fuse with the Golgi (Cullen 2008).

Rab GTPases OF THE EARLY AND LATE ENDOSOME

The described sorting, fission, and fusion processes require conserved machinery that is closely linked to Rab GTPases, tethers, and SNAREs. The fusion process includes the transport of vesicles along the cytoskeleton to the target organelle membrane, where Rabs and tethering factors mediate the initial interaction (Bonifacino and Glick 2004; Cullen 2008; Yu and Hughson 2010). This contact allows membrane-embedded SNARE proteins, which are found on both vesicle and target membrane, to form so-called SNARE complexes, which then drive the merging of bilayers and complete luminal mixing (Jahn and Scheller 2006).

Rabs are switch-like proteins with very poor enzymatic activity (Itzen and Goody 2011; Barr 2013). In their GDP form, Rabs interact with the cytosolic chaperone GDI, which also binds to their carboxy-terminal prenyl anchor and thus keeps the Rab soluble in the cytoplasm. On organelle membranes, specific guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), which are possibly assisted by a GDI displacement factor, promote the conversion of the Rab into the active GTP form and the insertion of the prenyl anchor into the membrane. The Rab-GTP can then bind to effectors such as tethering factors (Jahn and Scheller 2006; Barr and Lambright 2010; Lachmann et al. 2011; Barr 2013). Within the endolysosomal system, several Rab GTPases are required (Galvez et al. 2012), and we focus here primarily on Rab5 and Rab7. Rab5, which is found on early endosomes, is activated by the Rabex-5 GEF protein (Vps9 and Muk1 in yeast) (Horiuchi et al. 1997; Hama et al. 1999; Itzen and Goody 2011; Cabrera et al. 2013). Then it interacts with multiple effectors, including the phosphatidylinositol (PI)3-kinase Vps34, the large coiled-coil tethers early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1), rabaptin-5, rabenosyn-5, and subunits of the CORVET/HOPS tethering complex (Christoforidis et al. 1999; Rink et al. 2005; Galvez et al. 2012). By binding to the PI3-kinase Vps34, Rab5 promotes the generation of a PI3 phosphate (PI3P), which is characteristic of early endosomes and serves as a binding partner of multiple endosomal effectors. In fact, Rab5 is most critical for endosomal biogenesis, and loss of Rab5 function results in severe loss of all downstream organelles (Zeigerer et al. 2012). Early endosomes harbor several other additional Rabs including Rab11 and Rab4. These are both involved in recycling events, can form distinct domains on their own, and have their own effectors (Sonnichsen et al. 2000; Fouraux et al. 2004).

Early endosomes change in shape and membrane composition during their biogenesis. This does not only include the formation of ILVs, but also an exchange of the respective Rab GTPase, in that Rab5 is consecutively replaced by Rab7 (Rink et al. 2005; Vonderheit and Helenius 2005; Poteryaev et al. 2010; Zeigerer et al. 2012). This transition requires the Mon1–Ccz1 complex, which was identified as the Rab7-specific GEF (Nordmann et al. 2010; Gerondopoulos et al. 2012). In vivo analyses in Drosophila and human cells confirmed these findings (Kinchen and Ravichandran 2010; Yousefian et al. 2013). In metazoan cells, the Mon1 subunit of the Mon1–Ccz1 complex seems to promote the exchange by displacing the Rab5-activating Rabex-5 protein from endosomes, which is required for endosomal maturation (Poteryaev et al. 2010). Further inactivation of Rab5 is thought to be catalyzed by one of its GAPs, called RabGAP5 (Haas et al. 2005). Another GAP for Rab5, RN-Tre, is thought to also act on Rab5 at the plasma membrane (Lanzetti et al. 2000, 2004), whereas RabGAP5 could be endosome specific. It should be noted, however, that RN-Tre has considerably stronger preference for Rab41 and Rab43, and its depletion clearly affects Shiga toxin uptake (Haas et al. 2005, 2007; Fuchs et al. 2007). In yeast, the likely equivalent is the Msb3 protein, which inactivates the yeast Rab5 protein Vps21 at endosomes (Lachmann et al. 2012; Nickerson et al. 2012). Recent work suggests that the BLOC-1 complex, which is involved in the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles (Di Pietro et al. 2006; Setty et al. 2007), is an adapter of Msb3 and targets the GAP to Vps21 on endosomes (John Peter et al. 2013). In metazoan cells, BLOC-1 functions primarily at lysosome-related organelles even though an effect on Rab5 on early endosomes is also possible. Overall, this observation is in agreement with a model in which endosomal maturation is coordinated with the spatiotemporal control of Rab activity. In this context, it should be noted that Msb3 also acts on the yeast Rab7 Ypt7 and the exocytic Rab Sec4 (Gao et al. 2003; Lachmann et al. 2012; Nickerson et al. 2012). It is possible that GAPs might be modulated in their substrate recognition, depending on the local recruitment and environment.

At least two effectors have been identified for Rab7-GTP. It binds and recruits both the retromer complex (Haas et al. 2005; Rojas et al. 2008; Seaman et al. 2009; Balderhaar et al. 2010; Poteryaev et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2012) and the HOPS tethering complex (Seals et al. 2000; Bröcker et al. 2012). Retromer is a heteropentamer in yeast, which is subdivided into two independent complexes in mammalian cells. The retromer consists of the cargo recognition complex (CRC) with its subunits Vps35, Vps26, and Vps29, and the SNX subcomplex that displays heterodimeric Sorting NeXin (SNX) proteins, Vps5 and Vps17, in yeast (Bonifacino and Hurley 2008; Seaman 2012; John Peter et al. 2013). These SNX proteins have Bin–Amphiphysin–Rvs (BAR) domains that sense or induce curvature of membranes (McMahon and Gallop 2005; Cullen 2008). A major function of retromer is to collect receptors that deliver lysosomal hydrolases to the endosome, for example, mannose-6-phosphate receptor, via the CRC, sort them into tubular structures generated via the SNX proteins, and finally sort them back to the Golgi (Bonifacino and Hurley 2008; Seaman 2012). For this, activated Rab7 is probably the most critical because it becomes available only once endosomes have sufficiently matured. However, the role of the CRC has recently been extended to cargoes recycling to the plasma membrane, such as the β2 adrenergic receptor or the glucose transporter GLUT1 (Temkin et al. 2011; Seaman et al. 2013; Steinberg et al. 2013). Retromer recruitment at the late endosomes involves Rab7, whereas retromer recruitment at the early endosome seems to depend on SNX27, a sorting nexin unrelated to the Vps5 or 17 in yeast (Rojas et al. 2008; Seaman et al. 2009; Temkin et al. 2011; Steinberg et al. 2013). Interestingly, Rab7 also binds the HOPS tethering complex, which is required for late endosome–lysosome fusion, and it remains unclear how Rab7 coordinates retromer and this tethering complex, which are involved in different routes.

TETHERING FACTORS AND ENDOSOMAL FUSION

The understanding of endosomal and lysosomal fusion was guided by two powerful in vitro assays that rely on content mixing of two different populations of endosomes or lysosomes. The endosomal fusion assay was seminal in characterizing many factors involved in early endosomal biogenesis (e.g., Christoforidis et al. 1999). For lysosomal fusion, the yeast vacuole fusion assay of Wickner and colleagues paved the way to understand many factors involved in tethering and SNARE-driven content mixing (Haas et al. 1994; Wickner 2010). Both fusion reactions were eventually reconstituted with purified components (Mima and Wickner 2009; Ohya et al. 2009; Stroupe et al. 2009). Below, we summarize the main findings on endosomal tethering factors and fusion, which have relied in part on these assays.

At least two general classes of tethering factors exist in the endocytic pathway (Fig. 1). The first type of tethering factors is composed of long coiled-coil molecules, which capture vesicles at early endosomes. Among the identified proteins are rabenosyn-5, EEA1, and its yeast equivalent the Vac1 protein, although in vitro tethering activity was only shown for EEA1 (Christoforidis et al. 1999). All seem to form dimers and bind Rab5 (Simonsen et al. 1998; Peterson et al. 1999; Tall et al. 1999; Nielsen et al. 2000). In an impressive effort, early endosomal fusion has been reconstituted in vitro (Ohya et al. 2009). Among the required proteins were Rab5 and the two long coiled-coil tethers EEA1 and rabenosyn-5. Interestingly, only the combination of both tethers led to significant fusion, suggesting that one cannot substitute for the other. These two tethers also coordinate Rab function with SNARE assembly on early endosomes, because rabenosyn-5 binds the Sec1/Munc18-like Vps45 protein (Nielsen et al. 2000; Morrison et al. 2008), and EEA1 binds PI3P and SNAREs (Peterson et al. 1999; Tall et al. 1999), indicating that tethering and fusion machineries are organized into Rab5-dependent proteolipidic domains of early endosomes (Galvez et al. 2012). The second type of tethering factor is composed of multiprotein complexes, which are similarly organized by Rab proteins. These multiprotein complexes are named CORVET (Class C core vacuole/endosome tethering) and HOPS (homotypic fusion and protein sorting). CORVET is an effector of Rab5 and functions on early endosomes, whereas HOPS is a Rab7-binding protein and is found on late endosomes and lysosomes (Figs. 1 and 2).

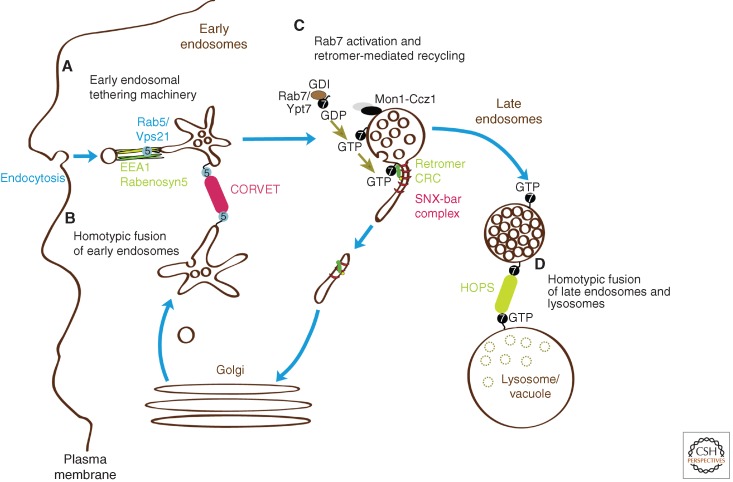

Figure 1.

Roles of tethering factors within the endolysosomal pathway. (A–D) Sequence of events requiring the different tethering factors. Fusion of early endosomes requires Rab5 and different Rab5 effectors for tethering. EEA1 and Rabenosyn5, which are long coiled-coil proteins, are both required for early endosomal fusion, whereas the multiprotein complex CORVET is required for homotypic fusion of endosomes. How these fusion events differ is not yet clear. Rab7 gradually replaces Rab5 along maturation toward late endosomes. Rab7 promotes both recycling through membrane tubule, a process that requires the retromer, and degradation through the fusion with lysosomes. The latter event depends on the HOPS complex to fuse two Rab7-positive membranes.

Figure 2.

Architecture of CORVET and HOPS complexes. CORVET and HOPS complexes share four subunits (depicted in gray). Vps3 and Vps8 connect the CORVET complex to Rab5, whereas Vps39 and Vps41 connect the HOPS complex to Rab7. The EM density of the HOPS complex, shown next to its diagram, displays a large head, which contains Vps41, and a small tail, which contains Vps39 (Bröcker et al. 2012).

CORVET and HOPS have been initially identified in yeast, but seem to be conserved across species (Seals et al. 2000; Wurmser et al. 2000; Kim et al. 2001; Richardson et al. 2004; Nickerson et al. 2009). Both are heterohexamers that share in yeast the four subunits Vps11, Vps16, Vps18, and Vps33 (Fig. 2) (Balderhaar et al. 2013). It is possible that the two A and B isoforms of Vps16 and Vps33 found in metazoan cells mark a further specialization of CORVET and HOPS complexes. In agreement with this proposal, Vps16A is required on late endosomes, whereas Vps16B is critical for phagocytosis and, thus, may exert early endocytic functions (Pulipparacharuvil et al. 2005; Cullinane et al. 2010; Akbar et al. 2011). For the yeast complexes, it was shown that two subunits in each complex determine the Rab specificity. The CORVET subunits Vps3 and Vps8 both interact with yeast Rab5-like Vps21 protein (Peplowska et al. 2007; Markgraf et al. 2009; Ohya et al. 2009; Plemel et al. 2011; Cabrera et al. 2013), as does the purified CORVET (Balderhaar et al. 2013). Vps41 and Vps39 are HOPS-specific subunits, which bind to the yeast Rab7-like protein Ypt7 and thus determine localization of HOPS to late endosomes and vacuoles/lysosomes (Seals et al. 2000; Ostrowicz et al. 2010; Plemel et al. 2011; Bröcker et al. 2012). This localization has now been generalized to mammalian cells (Pols et al. 2012).

In vitro and in vivo assays suggest that both complexes might conduct similar functions in tethering membranes. Purified CORVET can drive tethering of yeast Rab5-positive membranes (Balderhaar et al. 2013), whereas HOPS was sufficient to promote clustering of yeast Rab7-decorated liposomes (Hickey and Wickner 2010; Zick and Wickner 2012). Likewise, both complexes can stimulate membrane fusion (Balderhaar et al. 2013), although HOPS is so far the best-characterized and seemingly the most-active complex (Stroupe et al. 2006, 2009; Mima and Wickner 2009; Zick and Wickner 2012; Balderhaar et al. 2013). Recently, the overall structure of the yeast HOPS complex was determined (Fig. 2) (Bröcker et al. 2012). This first structure revealed insights into the likely function of both complexes in tethering. HOPS forms an elongated structure with a large head and a small tail. The two Rab-specific subunits were localized to the opposite ends of the complex. Vps41 is found in the large head and is proximal to one of the SNARE-binding sites provided by the Sec1/Munc18-like Vps33 subunit, whereas Vps39 is localized to the small tail. Because HOPS is able to bind to two Ypt7-GTP molecules via its two subunits Vp41 and Vps39 simultaneously and Ypt7 is required on both membranes for efficient vacuole fusion (Haas et al. 1995), it is likely that the tethering complex bridges Rab7-positive membranes such as late endosomes and lysosomes (Bröcker et al. 2012). The ability of HOPS to bind SNAREs via Vps33 and other subunits (Collins et al. 2005; Kramer and Ungermann 2011; Lobingier and Merz 2012) might facilitate their assembly and subsequent fusion of membranes. It is likely that CORVET conducts a similar function at endosomes because Vps33 also has the ability to interact with the endosomal syntaxin-like Pep12 protein (Subramanian et al. 2004). Moreover, the fusion between clathrin-coated vesicles and early endosomes also requires Rab5 on both membranes (Rubino et al. 2000). Because CORVET has two Rab5-binding sites (Vps3 and Vps8), it may bridge Rab5-positive endosomes and promote fusion as shown for Rab5-positive membranes in yeast (Balderhaar et al. 2013). We have discussed that Rab proteins coordinate different steps of endosomal fusion, such as tethering and lipid mixing upon membrane fusion. In the next section, we see that they also play a role in endosomal fission.

ENDOSOMAL FISSION AND THE CYTOSKELETON

Mechanistic dissection of endosomal fission has lagged behind compared with the fusion machinery. Fission is also more easily monitored in the context of endocytosis, within the plane of the plasma membrane by TIRF microscopy (see Merrifield and Kaksonen 2014), than in the context of an endosome, which moves fast along microtubule tracks in three dimensions (3D). In the few instances in which fission is caught in the act, physical separation of small buds or membrane tubules from the tubulovesicular endosome was observed. Fission generates the autonomous transport intermediates that address specific cargoes to their proper destinations.

The cytoskeleton plays a critical role in endosomal fission. It was shown in a reconstituted system using cytosol that microtubules are required for fission of purified endosomes (Bananis et al. 2003; Murray et al. 2008). Microtubules are also instrumental for endosome movement and shape and for the generation of tubular structures (Soldati and Schliwa 2006). Endosomal tubules that contain cargo are elongated along microtubule tracks using dynein and kinesin molecular motors. This requirement for microtubules is a major difference between endocytic and endosomal fission. In contrast, the actin cytoskeleton is critical for both types of fission.

The Arp2/3 complex that generates branched actin networks is required in both endocytic and endosomal fission, but it is activated by different activators: N-WASP activates the Arp2/3 at the clathrin-coated pit, whereas WASH activates the Arp2/3 at the surface of endosomes (Suetsugu and Gautreau 2012). WASH associates with all organelles of the endosomal/lysosomal system with an enrichment in early and late endosomes (Derivery et al. 2009; Gomez and Billadeau 2009). WASH labels restricted areas of the endosomal membrane, which we refer to as microdomains. These microdomains are associated with polymerized actin. When WASH is inactivated, Arp2/3 and most polymerized actin are lost from the surface of endosomes, indicating that WASH plays a major role in the polymerization of endosomal actin (Derivery et al. 2009). WASH is constantly associated with the endosomal surface, and there is usually one WASH microdomain when the endosome is small and several when they are bigger. When endosomal tubules are present, WASH microdomains usually are associated with these tubules. However, WASH is constantly associated with the endosomal surface whether or not tubules are present.

THE ROLE OF WASH IN ENDOSOMAL FISSION

The evidence that WASH is involved in endosomal fission relies on several observations. First, upon WASH knockdown, endosomes form exaggerated tubules, as if their fission was impaired (Derivery et al. 2009; Gomez and Billadeau 2009). This exaggerated tubulation along microtubules occurs on all WASH-positive organelles, that is, Rab 4, 5, 7, and 11 positive compartments. This phenotype is associated with defects of transport of cargoes from all three major routes: (1) recycling of transferrin receptor (Derivery et al. 2009), β2 adrenergic receptor (Puthenveedu et al. 2010), integrins (Zech et al. 2011; Duleh and Welch 2012), Glut1, and TCR (Piotrowski et al. 2013); (2) retrograde transport of the mannose-6-phosphate receptor (Gomez and Billadeau 2009; Harbour et al. 2010); and (3) along the degradative pathway of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Duleh and Welch 2010) and in the retrieval of v-ATPase from lysosomes in Dictyostelium (Carnell et al. 2011).

Because actin polymerization is critical for endocytic fission and dynamin is the major machinery of scission in mammalian cells, a connection between WASH and dynamin was hypothesized and identified (Derivery et al. 2009). Dynamin recruitment is probably facilitated by numerous additional interactions. For example, the branches that correspond to the Arp2/3 complex in actin networks are recognized by the protein cortactin, which contains an SH3 domain that directly binds to dynamin (McNiven et al. 2000; Cai et al. 2008). WASH depletion is phenocopied by dynamin inhibition. Upon dynamin inhibition, long tubules are extended, and the WASH microdomain is found in most cases associated with the base of tubules, at the expected localization to generate a transport intermediate by fission (Derivery et al. 2009). Altogether these data support the idea that WASH and the resulting branched actin network at the surface of endosomes play a critical role in endosomal fission (Fig. 3), in an analogous manner to the role of N-WASP in fission of clathrin-coated pits.

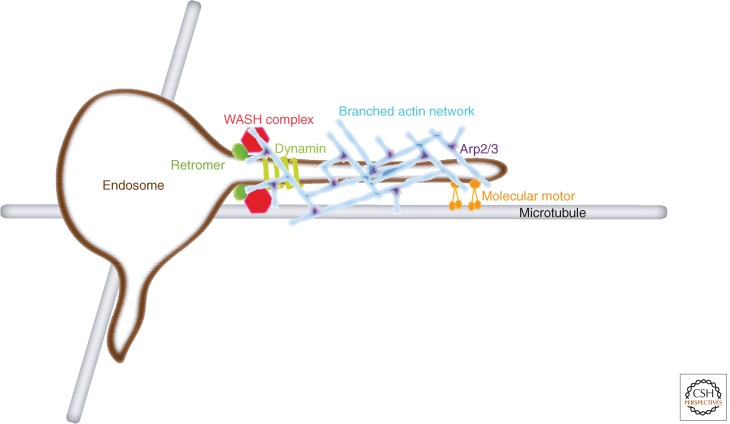

Figure 3.

WASH complex generation of branched actin network at the surface of an endosome. The WASH complex labels a restricted domain of endosome, which corresponds to a location where endosomal tubules are elongated. The WASH complex interacts with the Arp2/3 complex and activates it. The activated Arp2/3 complex nucleates new actin filaments branching off preexisting filaments. The branched actin network has been shown to be instrumental first for the elongation of the endosomal tubule, in tight coordination with microtubule motors, and then to promote endosomal fission. Fission, which occurs at the base of the tubule, requires the activity of the large GTPase dynamin. All these steps are necessary to generate an intermediate of transport-containing sorted cargoes.

EHD molecules form another class of enzymes that oligomerize around lipid tubules in ring-like structures like dynamin (Daumke et al. 2007). Through their fission-promoting activity, they are critical for endosomal recycling (Rapaport et al. 2006; Pant et al. 2009). What is not fully established, however, is whether EHD proteins represent an alternative to dynamin for performing fission or whether they function upstream of dynamin (Jakobsson et al. 2011). Interestingly, the EHD proteins interact with the retromer (Gokool et al. 2007) and with the F-BAR protein PACSIN/Syndapin (Braun et al. 2005). These two interactions connect EHD proteins to the formation of branched actin networks (Suetsugu and Gautreau 2012; Seaman et al. 2013).

Branched actin networks are well established to generate a pushing force against the membrane that displays the Arp2/3 activator. Branched actin networks push against the plasma membrane to create protrusions involved in cell migration. In trafficking, it is still not fully understood how this force contributes to fission. In the case of endocytic fission, branched actin networks make collars at the neck of clathrin-coated pits (Collins et al. 2011). So it is certainly possible that actin polymerization around the endosomal tubule results in neck constriction and favors scission. However, it is also likely that WASH and the generated endosomal branched actin networks possess additional functions, which all contribute to endosomal sorting. The situation is reminiscent of Rab proteins, where key roles at different steps of endosomal transport have been discovered over the last years.

ADDITIONAL ROLES OF WASH IN ENDOSOMAL SORTING

Recently, many observations suggested that WASH might not be only involved in the fission stage, but also before endosomal tubules are elongated. Indeed, downstream from WASH, silencing of the Arp2/3 complex or inhibiting actin polymerization using drugs result in enlarged endosomes with no tubules (Derivery et al. 2012). Silencing of cortactin also leads to a defective accumulation of β2 adrenergic receptor in endosomal tubules (Puthenveedu et al. 2010). These results are at odds with the exaggerated tubulation observed in earlier reports upon WASH knockdown (Derivery et al. 2009; Gomez and Billadeau 2009; Duleh and Welch 2010). Recently, a WASH knockout in mice was generated, and complete depletion of the WASH protein induces enlarged endosomes with no tubules at all (Gomez et al. 2012). Together, these data argue for an additional role of branched actin networks in the elongation of endosomal tubules (Fig. 3). Even if the two phenotypes associated with WASH depletion and defective endosomal actin polymerization appear contradictory—exaggerated tubulation versus no tubule at all—they likely represent defects in two distinct steps of the same pathway of endosomal sorting, as suggested by the enlargement of endosomes, which reflects the accumulation of endosomal material.

Another possible role of endosomal actin is to prevent endosomes from clumping (Drengk et al. 2003). Indeed, in WASH knockout cells, endosomes and lysosomes are aggregated (Gomez et al. 2012). This suggests that endosomal actin structures form a protective shell that surrounds the organelles and prevents their membranes from docking onto each other. Even though it is still unclear what this phenotype reveals, it is probably important that organelles are separated from each other to permit their correct intracellular targeting. Endosomal actin is also required for endosomal maturation (Morel et al. 2009).

Endosomal sorting relies on the generation of specialized membrane microdomains that cluster cargoes, before intermediates of transport can be generated. Branched actin networks are also likely instrumental in the definition of such microdomains. Branched actin networks can promote the formation of distinct lipidic phases on a homogeneous liposome (Liu and Fletcher 2006). When lipid demixing occurs, small microdomains of the same lipid composition coalesce over time to form a single large patch, and constriction occurs at the interface between lipid phases (Baumgart et al. 2003; Bacia et al. 2005). These two effects are due to the so-called line tension that develops at the interface because of the energetic cost of accommodating different lipids of unmatched characteristics, such as different heights of acyl chains. This constriction at the interface favors membrane fission (Jülicher and Lipowsky 1993) and has been proposed to be critical for endocytic fission in yeast (Liu et al. 2006), where dynamin-related proteins appear dispensable, or in toxin-induced clathrin-independent endocytosis in mammalian cells (Römer et al. 2010; Johannes et al. 2014).

Evidence suggests that similar biophysical mechanisms implicating lipids might play a role in endosomal fission, before dynamin comes into play or in addition to dynamin’s role (de Figueiredo et al. 2001; van Dam et al. 2002; Egami and Araki 2008). For example, when the Vps34-related PI3 kinase, producing PI3P at the surface of endosomes, is inactivated, apical endosomes of kidney epithelial cells swell (Carpentier et al. 2013). Upon inhibitor washout, numerous tubules are induced. These tubules recruit dynamin and allow cargo recycling. Several WASH microdomains are observed at the surface of endosomes that are enlarged by the homotypic fusion induced by active Rab5. These microdomains likely possess a lipid composition distinct from the surrounding membrane, because they spontaneously coalesce when actin polymerization is impaired (Derivery et al. 2012). This study suggests that endosomal actin polymerization prevents small microdomains from coalescing as if actin was shielding the interface of proteolipidic domains. Such a role is likely to be important for cargo clustering and tubule fission.

REGULATION OF THE WASH MACHINERY

The WASH protein is regulated within a multiprotein complex. This stable complex contains five core subunits, which are all required for WASH stability in mammalian cells (Fig. 4) (Derivery et al. 2009; Jia et al. 2010). Two large conserved subunits, Strumpellin and SWIP, are mutated in diseases affecting the neurons of patients. The first one is hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), characterized by degeneration of motor neurons. Mutations at several different genetic loci can cause this disease. One locus is the Strumpellin gene; several other HSP loci encode proteins relevant for microtubule physiology, for example, spastin, which cuts microtubules, and KIF5A, which encodes a kinesin motor (Dion et al. 2009). A second genetic disease is nonsyndromic mental retardation, where a point mutation in the gene encoding the SWIP subunit of the WASH complex has been reported (Ropers et al. 2011). This single point mutation in the 1100-amino-acid-long SWIP protein is sufficient to destabilize the entire WASH complex and to induce clumping of endosomes (Fig. 5) (Ropers et al. 2011). Neurons appear particularly sensitive to defective endosomal traffic. This requirement might be due to the critical traffic along the long axons of motor neurons (up to 1 m). Another remarkable subunit is FAM21, which shows a long, unstructured carboxy-terminal arm containing multiple functional binding sites (Fig. 4) (Derivery and Gautreau 2010).

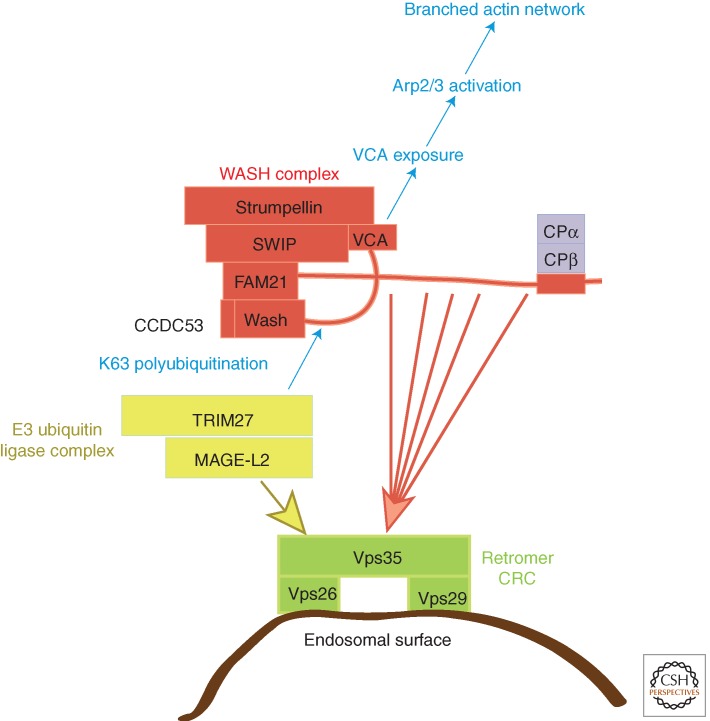

Figure 4.

Regulation of WASH within a stable multiprotein complex and associated activities. The WASH complex is composed of five core subunits and of the peripheral capping protein (CP) heterodimer. The core complex regulates the activity of the VCA output domain harbored by WASH. This ouput region interacts with the Arp2/3 complex, activates it, and thus induces the formation of a new actin filament branching of a preexisting filament. The exposure of the VCA output domain is regulated by WASH polyubiquitination catalyzed by the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM27 bound to its enhancer MAGE-L2. Recruitment of the WASH complex at the surface of endosomes and recruitment of the E3 ubiquitin ligase require the cargo recognition complex of retromer, composed of Vps35, Vps26, and Vps29. There are multiple weak binding sites along the FAM21 tail for Vps35, suggesting that these machineries form a fluid sorting platform with the abilities to elongate tubules and to fission them. In this context, the role of CP, which can block the dynamics of newly created actin filaments, is not yet understood.

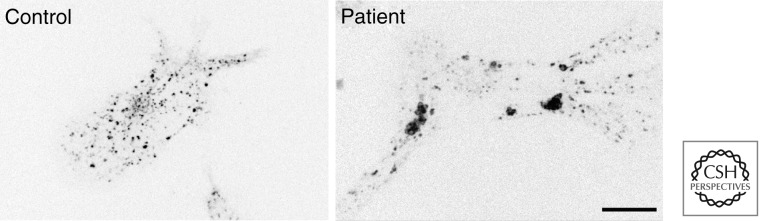

Figure 5.

Endosome clumping in patients affected with mental retardation. In a family of patients where the SWIP subunit of the WASH complex harbors a single point mutation, the whole WASH complex is destabilized (Ropers et al. 2011). In lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from these patients, endosomes, labeled here with transferrin, are clumped (E Derivery and A Gautreau, unpubl.), suggesting that actin polymerization prevents unspecific aggregation of organelles. Neurons appear particularly sensitive to defective endosomal sorting associated with impairment of WASH activity. Scale bar, 10 μm.

The WASH complex directly binds to lipids (Derivery et al. 2009), and a binding site for the endosomal phosphoinositides PI3P and PI(3,5)P2 has been identified in the carboxyl terminus of FAM21 (Jia et al. 2010). This direct binding to lipids suggests that the WASH complex might have a direct role in the definition of the proteolipidic domain required for endosomal sorting.

FAM21 also recruits the capping protein (CP). The heterodimer of CP is a complex on its own, which is secondarily recruited by the WASH complex (Derivery et al. 2009). CP is an antagonist of WASH, in the sense that it blocks the elongation of new actin filaments, which WASH and the Arp2/3 complex nucleate. A CP-interacting (CPI) motif has been identified close to the end of the long, unstructured arm of FAM21 (Hernandez-Valladares et al. 2010). The CPI motif is required for the function of the WASH complex, as recently shown in the amoeba Dictyostelium (Park et al. 2013). However, the function of the CPI is still enigmatic. The CPI can uncap actin filaments (Hernandez-Valladares et al. 2010), but CP also stays associated with the WASH complex, where it shows a detectable capping activity (Derivery et al. 2009). CP might hold the key to the different roles of the WASH complex in different stages of endosomal sorting, because these different stages are likely to correspond to different regimes of actin polymerization.

The retromer has recently been shown to be the receptor of the WASH complex at the surface of endosomes (Fig. 4) (Harbour et al. 2010; Jia et al. 2012; Helfer et al. 2013). FAM21 interacts with the CRC through multiple binding sites scattered along its long, unstructured arm (Jia et al. 2012). The WASH complex becomes cytosolic, upon knockdown of the CRC of retromer (Harbour et al. 2010) or upon overexpression of FAM21 fragments containing functional binding sites for this subcomplex (Helfer et al. 2013). The presence of a dozen retromer-binding sites on FAM21 together with the limited affinity of each one of them suggests that cargoes, retromer, and WASH complexes might constitute fluid sorting platforms linked to the actin cytoskeleton.

The ability of WASH to activate the Arp2/3 complex is critically regulated by ubiquitination (Hao et al. 2013). The VCA output domain of WASH that binds and activates the Arp2/3 complex is masked by interactions within the core WASH complex. Polyubiquitination by a K63-linked chain of a flexible region of WASH induces VCA exposure and actin polymerization (Fig. 4). Importantly, the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM27 and its enhancer MAGE-L2 are recruited by the CRC retromer platform close to its substrate WASH, as depicted in Figure 4. Upon depletion of TRIM27 or of MAGE-L2, endosomes were shown to tubulate, an observation that further reinforces the importance of WASH complex activity and of actin polymerization in endosomal scission.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Despite tremendous advances in the understanding of the machineries required for endosomal fusion and fission, we believe several open questions highlight future research directions.

Rab Coordination and Turnover

Studies on Rab5 and Rab7 in metazoan cells suggest that Rabs affect each other in so-called Rab cascades, where active Rab5 promotes the recruitment of Rab7. This appealing model does not yet clarify when such a process is initiated, nor how inactivation of Rab5 is coordinated with Rab7 activation. A simple mathematical model by (del Conte-Zerial et al. (2008) suggests that the density of Rab5 and the activation of Rab7 must increase beyond a threshold level, which then results in repression of Rab5. However, the molecular basis of such a switch, including the expected molecular density of Rab5 and Rab7, is not yet known. The recent identification of yeast BLOC-1 as a Rab5-GAP-recruiting complex suggests that Rab turnover extends beyond the countercontrol of these two Rab GTPases as Rab5 seems to control its own turnover (John Peter et al. 2013).

Endosomal Maturation

Maturing endosomes are challenged with the task to handle material that arrives both from the Golgi and the cell surface and sort ubiquitinated proteins into intraluminal vesicles via the ESCRT machinery. They also need to redirect the receptors that deliver hydrolases to the lysosome from the late endosome back to the Golgi via the retromer complex. Thus, receptors and ubiquitinated cargo are on the same membrane but need to be separated into distinct domains. Moreover, it is expected that the phosphoinositide composition will change while endosomes mature. Loss of any of the involved machineries results in strong endosomal and lysosomal defects, because activated receptors will still signal if they have not been sequestered into the endosomal lumen. Even if molecular machineries have been identified, the coordination between them in space and time and the hierarchy of the processes they perform are not understood.

The Sharing of Subunits between Two Endosomal Tethers

The fact that HOPS and CORVET share four subunits raises several questions. Are these complexes built once for all? Or do these complexes gradually change composition from CORVET to HOPS along endosomal maturation? If this is the case, how is disassembly/reassembly controlled? At least in the absence of the Rabs, CORVET and HOPS are still maintained as hexamers (Epp and Ungermann 2013). This does not exclude that efficient assembly requires the endosomal surface.

Role of Actin in Yeast Endosomal Fission

Recent years have seen a tremendous amount of work highlighting the role of the WASH complex in endosomal fission in mammalian cells and amoebae. However, this machinery is not conserved in yeasts. Is endosomal fission less important in yeast? Does endosomal actin play a similar role? If yes, what is the nature of the actin polymerization machinery?

How Are Branched Actin Networks Organized at the Surface of Endosomes and How Does the Associated Force Generation Contribute to Endosomal Sorting?

The WASH complex combines antagonistic activities, actin nucleation, and capping, in the regulation of actin polymerization at the surface of endosomes. Thus, a major question is to understand how these activities are coordinated at different stages of endosomal sorting: during the generation of a proteolipidic microdomain, tubule elongation, and endosome fission.

The Challenge of In Vitro Reconstitution

Given the technical difficulty associated with direct observation of endosomal fission, in vitro reconstitution seems appropriate to directly observe fission and to cease interpreting endosomal tubulation as defective fission. The reconstitution of endosomal fusion with pure proteins was a tour de force. Reconstitution of endosomal fission is an even bigger challenge ahead of us, because fission requires dynamics of both the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. A stepwise approach using first cell-free extracts to unambiguously the identify machineries involved in the process and then pure components seems an appropriate endeavor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work in the laboratory of A.G. is supported by ANR grants (ANR-11-BSV8-0010-02; ANR-11 BSV2-014-01). Work in the laboratory of C.U. is supported by the SFB 944 (project P11), the DFG grants UN111/5-3 and 7-1, and by the Hans-Mühlenhoff foundation.

Footnotes

Editors: Sandra L. Schmid, Alexander Sorkin, and Marino Zerial

Additional Perspectives on Endocytosis available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Akbar MA, Tracy C, Kahr WHA, Kramer H 2011. The full-of-bacteria gene is required for phagosome maturation during immune defense in Drosophila. J Cell Biol 192: 383–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacia K, Schwille P, Kurzchalia T 2005. Sterol structure determines the separation of phases and the curvature of the liquid-ordered phase in model membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 3272–3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderhaar HJK, Arlt H, Ostrowicz CW, Bröcker C, Sündermann F, Brandt R, Babst M, Ungermann C 2010. The Rab GTPase Ypt7 is linked to retromer-mediated receptor recycling and fusion at the yeast late endosome. J Cell Sci 123: 4085–4094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderhaar HJK, Lachmann J, Yavavli E, Bröcker C, Lürick A, Ungermann C 2013. The CORVET complex promotes tethering and fusion of Rab5/Vps21-positive membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 3823–3828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bananis E, Murray JW, Stockert RJ, Satir P, Wolkoff AW 2003. Regulation of early endocytic vesicle motility and fission in a reconstituted system. J Cell Sci 116: 2749–2761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr FA 2013. Rab GTPases and membrane identity: Causal or inconsequential? J Cell Biol 202: 191–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr F, Lambright DG 2010. Rab GEFs and GAPs. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22: 461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgart T, Hess ST, Webb WW 2003. Imaging coexisting fluid domains in biomembrane models coupling curvature and line tension. Nature 425: 821–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Glick BS 2004. The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell 116: 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Hurley JH 2008. Retromer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20: 427–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun A, Pinyol R, Dahlhaus R, Koch D, Fonarev P, Grant BD, Kessels MM, Qualmann B 2005. EHD proteins associate with syndapin I and II and such interactions play a crucial role in endosomal recycling. Mol Biol Cell 16: 3642–3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bröcker C, Kuhlee A, Gatsogiannis C, Kleine Balderhaar HJ, Hönscher C, Engelbrecht-Vandré S, Ungermann C, Raunser S 2012. Molecular architecture of the multisubunit homotypic fusion and vacuole protein sorting (HOPS) tethering complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 1991–1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera M, Arlt H, Epp N, Lachmann J, Griffith J, Perz A, Reggiori F, Ungermann C 2013. Functional separation of endosomal fusion factors and the class C core vacuole/endosome tethering (CORVET) complex in endosome biogenesis. J Biol Chem 288: 5166–5175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Makhov AM, Schafer DA, Bear JE 2008. Coronin 1B antagonizes cortactin and remodels Arp2/3-containing actin branches in lamellipodia. Cell 134: 828–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnell M, Zech T, Calaminus SD, Ura S, Hagedorn M, Johnston SA, May RC, Soldati T, Machesky LM, Insall RH 2011. Actin polymerization driven by WASH causes V-ATPase retrieval and vesicle neutralization before exocytosis. J Cell Biol 193: 831–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier S, N’kuli F, Grieco G, Van Der Smissen P, Janssens V, Emonard H, Bilanges B, Vanhaesebroeck B, Gaide Chevronnay HP, Pierreux CE, et al. 2013. Class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase/VPS34 and dynamin are critical for apical endocytic recycling. Traffic 14: 933–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoforidis S, McBride H, Burgoyne R, Zerial M 1999. The Rab5 effector EEA1 is a core component of endosome docking. Nature 397: 621–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K, Thorngren N, Fratti R, Wickner W 2005. Sec17p and HOPS, in distinct SNARE complexes, mediate SNARE complex disruption or assembly for fusion. EMBO J 24: 1775–1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Warrington A, Taylor KA, Svitkina T 2011. Structural organization of the actin cytoskeleton at sites of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Curr Biol 21: 1167–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen PJ 2008. Endosomal sorting and signalling: An emerging role for sorting nexins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 574–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinane AR, Straatman-Iwanowska A, Zaucker A, Wakabayashi Y, Bruce CK, Luo G, Rahman F, Gürakan F, Utine E, Özkan TB, et al. 2010. Mutations in VIPAR cause an arthrogryposis, renal dysfunction and cholestasis syndrome phenotype with defects in epithelial polarization. Nat Genet 42: 303–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daumke O, Lundmark R, Vallis Y, Martens S, Butler PJG, McMahon HT 2007. Architectural and mechanistic insights into an EHD ATPase involved in membrane remodelling. Nature 449: 923–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Figueiredo P, Doody A, Polizotto RS, Drecktrah D, Wood S, Banta M, Strang MS, Brown WJ 2001. Inhibition of transferrin recycling and endosome tubulation by phospholipase A2 antagonists. J Biol Chem 276: 47361–47370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Conte-Zerial P, Brusch L, Rink JC, Collinet C, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M, Deutsch A 2008. Membrane identity and GTPase cascades regulated by toggle and cut-out switches. Mol Syst Biol 4: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derivery E, Gautreau A 2010. Evolutionary conservation of the WASH complex, an actin polymerization machine involved in endosomal fission. Commun Integr Biol 3: 227–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derivery E, Sousa C, Gautier JJ, Lombard B, Loew D, Gautreau A 2009. The Arp2/3 activator WASH controls the fission of endosomes through a large multiprotein complex. Dev Cell 17: 712–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derivery E, Helfer E, Henriot V, Gautreau A 2012. Actin polymerization controls the organization of WASH domains at the surface of endosomes. PLoS ONE 7: e39774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion PA, Daoud H, Rouleau GA 2009. Genetics of motor neuron disorders: New insights into pathogenic mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet 10: 769–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro SM, Falcón-Pérez JM, Tenza D, Setty SRG, Marks MS, Raposo G, Dell’Angelica EC 2006. BLOC-1 interacts with BLOC-2 and the AP-3 complex to facilitate protein trafficking on endosomes. Mol Biol Cell 17: 4027–4038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drengk A, Fritsch J, Schmauch C, Rühling H, Maniak M 2003. A coat of filamentous actin prevents clustering of late-endosomal vacuoles in vivo. Curr Biol 13: 1814–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duleh SN, Welch MD 2010. WASH and the Arp2/3 complex regulate endosome shape and trafficking. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 67: 193–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duleh SN, Welch MD 2012. Regulation of integrin trafficking, cell adhesion, and cell migration by WASH and the Arp2/3 complex. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 69: 1047–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egami Y, Araki N 2008. Characterization of Rab21-positive tubular endosomes induced by PI3K inhibitors. Exp Cell Res 314: 729–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp N, Ungermann C 2013. The N-terminal domains of Vps3 and Vps8 are critical for localization and function of the CORVET tethering complex on endosomes. PLoS ONE 8: e67307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouraux M, Deneka M, Ivan V, van der Heijden A, Raymackers J, van Suylekom D, van Venrooij W, van der Sluijs P, Pruijn G 2004. rabip4′ is an effector of rab5 and rab4 and regulates transport through early endosomes. Mol Biol Cell 15: 611–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Haas AK, Spooner RA, Yoshimura S-I, Lord JM, Barr FA 2007. Specific Rab GTPase-activating proteins define the Shiga toxin and epidermal growth factor uptake pathways. J Cell Biol 177: 1133–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez T, Gilleron J, Zerial M, O’Sullivan GA 2012. SnapShot: Mammalian Rab proteins in endocytic trafficking. Cell 151: 234–234 e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X-D, Albert S, Tcheperegine SE, Burd CG, Gallwitz D, Bi E 2003. The GAP activity of Msb3p and Msb4p for the Rab GTPase Sec4p is required for efficient exocytosis and actin organization. J Cell Biol 162: 635–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerondopoulos A, Langemeyer L, Liang J-R, Linford A, Barr FA 2012. BLOC-3 mutated in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome is a Rab32/38 guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Curr Biol 1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokool S, Tattersall D, Seaman MNJ 2007. EHD1 interacts with retromer to stabilize SNX1 tubules and facilitate endosome-to-Golgi retrieval. Traffic 8: 1873–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez TS, Billadeau DD 2009. A FAM21-containing WASH complex regulates retromer-dependent sorting. Dev Cell 17: 699–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez TS, Gorman JA, de Narvajas AA-M, Koenig AO, Billadeau DD 2012. Trafficking defects in WASH-knockout fibroblasts originate from collapsed endosomal and lysosomal networks. Mol Biol Cell 23: 3215–3228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A, Conradt B, Wickner W 1994. G-protein ligands inhibit in vitro reactions of vacuole inheritance. J Cell Biol 126: 87–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A, Scheglmann D, Lazar T, Gallwitz D, Wickner W 1995. The GTPase Ypt7p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required on both partner vacuoles for the homotypic fusion step of vacuole inheritance. EMBO J 14: 5258–5270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AK, Fuchs E, Kopajtich R, Barr FA 2005. A GTPase-activating protein controls Rab5 function in endocytic trafficking. Nat Cell Biol 7: 887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AK, Yoshimura S-I, Stephens DJ, Preisinger C, Fuchs E, Barr FA 2007. Analysis of GTPase-activating proteins: Rab1 and Rab43 are key Rabs required to maintain a functional Golgi complex in human cells. J Cell Sci 120: 2997–3010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama H, Tall G, Horazdovsky B 1999. Vps9p is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor involved in vesicle-mediated vacuolar protein transport. J Biol Chem 274: 15284–15291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y-H, Doyle JM, Ramanathan S, Gomez TS, Jia D, Xu M, Chen ZJ, Billadeau DD, Rosen MK, Potts PR 2013. Regulation of WASH-dependent actin polymerization and protein trafficking by ubiquitination. Cell 152: 1051–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour ME, Breusegem SYA, Antrobus R, Freeman C, Reid E, Seaman MNJ 2010. The cargo-selective retromer complex is a recruiting hub for protein complexes that regulate endosomal tubule dynamics. J Cell Sci 123: 3703–3717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfer E, Harbour ME, Henriot V, Lakisic G, Sousa-Blin C, Volceanov L, Seaman MNJ, Gautreau A 2013. Endosomal recruitment of the WASH complex: Active sequences and mutations impairing interaction with the retromer. Biol Cell 105: 191–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Valladares M, Kim T, Kannan B, Tung A, Aguda AH, Larsson M, Cooper JA, Robinson RC 2010. Structural characterization of a capping protein interaction motif defines a family of actin filament regulators. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 497–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey CM, Wickner W 2010. HOPS initiates vacuole docking by tethering membranes before trans-SNARE complex assembly. Mol Biol Cell 21: 2297–2305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi H, Lippe R, McBride H, Rubino M, Woodman P, Stenmark H, Rybin V, Wilm M, Ashman K, Mann M, et al. 1997. A novel Rab5 GDP/GTP exchange factor complexed to Rabaptin-5 links nucleotide exchange to effector recruitment and function. Cell 90: 1149–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huotari J, Helenius A 2011. Endosome maturation. EMBO J 30: 3481–3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzen A, Goody RS 2011. GTPases involved in vesicular trafficking: Structures and mechanisms. Semin Cell Dev Biol 22: 48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R, Scheller R 2006. SNAREs—Engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson J, Ackermann F, Andersson F, Larhammar D, Löw P, Brodin L 2011. Regulation of synaptic vesicle budding and dynamin function by an EHD ATPase. J Neurosci 31: 13972–13980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Gomez TS, Metlagel Z, Umetani J, Otwinowski Z, Rosen MK, Billadeau DD 2010. WASH and WAVE actin regulators of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) family are controlled by analogous structurally related complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 10442–10447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Gomez TS, Billadeau DD, Rosen MK 2012. Multiple repeat elements within the FAM21 tail link the WASH actin regulatory complex to the retromer. Mol Biol Cell 23: 2352–2361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Johannes L, Wunder C, Bassereau P 2014. Bending “on the rocks”—A cocktail of biophysical modules to build endocytic pathways. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6: a016741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John Peter AT, Lachmann J, Rana M, Bunge M, Cabrera M, Ungermann C 2013. The BLOC-1 complex promotes endosomal maturation by recruiting the Rab5 GTPase-activating protein Msb3. J Cell Biol 201: 97–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jülicher F, Lipowsky R 1993. Domain-induced budding of vesicles. Phys Rev Lett 70: 2964–2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Kramer H, Yamamoto A, Kominami E, Kohsaka S, Akazawa C 2001. Molecular characterization of mammalian homologues of class C Vps proteins that interact with syntaxin-7. J Biol Chem 276: 29393–29402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinchen JM, Ravichandran KS 2010. Identification of two evolutionarily conserved genes regulating processing of engulfed apoptotic cells. Nature 464: 778–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer L, Ungermann C 2011. HOPS drives vacuole fusion by binding the vacuolar SNARE complex and the Vam7 PX domain via two distinct sites. Mol Biol Cell 22: 2601–2611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann J, Ungermann C, Engelbrecht-Vandré S 2011. Rab GTPases and tethering in the yeast endocytic pathway. Small GTPases 2: 182–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann J, Barr FA, Ungermann C 2012. The Msb3/Gyp3 GAP controls the activity of the Rab GTPases Vps21 and Ypt7 at endosomes and vacuoles. Mol Biol Cell 23: 2516–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzetti L, Rybin V, Malabarba MG, Christoforidis S, Scita G, Zerial M, Di Fiore PP 2000. The Eps8 protein coordinates EGF receptor signalling through Rac and trafficking through Rab5. Nature 408: 374–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzetti L, Palamidessi A, Areces L, Scita G, Di Fiore PP 2004. Rab5 is a signalling GTPase involved in actin remodelling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature 429: 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AP, Fletcher DA 2006. Actin polymerization serves as a membrane domain switch in model lipid bilayers. Biophys J 91: 4064–4070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Kaksonen M, Drubin DG, Oster G 2006. Endocytic vesicle scission by lipid phase boundary forces. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 10277–10282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T-T, Gomez TS, Sackey BK, Billadeau DD, Burd CG 2012. Rab GTPase regulation of retromer-mediated cargo export during endosome maturation. Mol Biol Cell 23: 2505–2515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobingier BT, Merz AJ 2012. Sec1/Munc18 protein Vps33 binds to SNARE domains and the quaternary SNARE complex. Mol Biol Cell 23: 4611–4622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markgraf DF, Ahnert F, Arlt H, Mari M, Peplowska K, Epp N, Griffith J, Reggiori F, Ungermann C 2009. The CORVET subunit Vps8 cooperates with the Rab5 homolog Vps21 to induce clustering of late endosomal compartments. Mol Biol Cell 20: 5276–5289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor S, Presley JF, Maxfield FR 1993. Sorting of membrane components from endosomes and subsequent recycling to the cell surface occurs by a bulk flow process. J Cell Biol 121: 1257–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon HT, Gallop JL 2005. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature 438: 590–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNiven MA, Kim L, Krueger EW, Orth JD, Cao H, Wong TW 2000. Regulated interactions between dynamin and the actin-binding protein cortactin modulate cell shape. J Cell Biol 151: 187–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Merrifield CJ, Kaksonen M 2014. Endocytic accessory factors and regulation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a016733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima J, Wickner W 2009. Phosphoinositides and SNARE chaperones synergistically assemble and remodel SNARE complexes for membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 16191–16196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel E, Parton RG, Gruenberg J 2009. Annexin A2-dependent polymerization of actin mediates endosome biogenesis. Dev Cell 16: 445–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison HA, Dionne H, Rusten TE, Brech A, Fisher WW, Pfeiffer BD, Celniker SE, Stenmark H, Bilder D 2008. Regulation of early endosomal entry by the Drosophila tumor suppressors Rabenosyn and Vps45. Mol Biol Cell 19: 4167–4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JW, Sarkar S, Wolkoff AW 2008. Single vesicle analysis of endocytic fission on microtubules in vitro. Traffic 9: 833–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson DP, Brett CL, Merz AJ 2009. Vps-C complexes: Gatekeepers of endolysosomal traffic. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21: 543–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson DP, Russell MRG, Lo S-Y, Chapin HC, Milnes JM, Merz AJ 2012. Termination of isoform-selective Vps21/Rab5 signaling at endolysosomal organelles by Msb3/Gyp3. Traffic 13: 1411–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen E, Christoforidis S, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Miaczynska M, Dewitte F, Wilm M, Hoflack B, Zerial M 2000. Rabenosyn-5, a novel Rab5 effector, is complexed with hVPS45 and recruited to endosomes through a FYVE finger domain. J Cell Biol 151: 601–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann M, Cabrera M, Perz A, Bröcker C, Ostrowicz CW, Engelbrecht-Vandré S, Ungermann C 2010. The Mon1–Ccz1 complex is the GEF of the late endosomal Rab7 homolog Ypt7. Curr Biol 20: 1654–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohya T, Miaczynska M, Coskun Ü, Lommer B, Runge A, Drechsel D, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M 2009. Reconstitution of Rab- and SNARE-dependent membrane fusion by synthetic endosomes. Nature 459: 1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowicz CW, Bröcker C, Ahnert F, Nordmann M, Lachmann J, Peplowska K, Perz A, Auffarth K, Engelbrecht-Vandré S, Ungermann C 2010. Defined subunit arrangement and rab interactions are required for functionality of the HOPS tethering complex. Traffic 11: 1334–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant S, Sharma M, Patel K, Caplan S, Carr CM, Grant BD 2009. AMPH-1/Amphiphysin/Bin1 functions with RME-1/Ehd1 in endocytic recycling. Nat Cell Biol 11: 1399–1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park L, Thomason PA, Zech T, King JS, Veltman DM, Carnell M, Ura S, Machesky LM, Insall RH 2013. Cyclical action of the WASH complex: FAM21 and capping protein drive WASH recycling, not initial recruitment. Dev Cell 24: 169–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplowska K, Markgraf DF, Ostrowicz CW, Bange G, Ungermann C 2007. The CORVET tethering complex interacts with the yeast Rab5 homolog Vps21 and is involved in endo-lysosomal biogenesis. Dev Cell 12: 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson MR, Burd CG, Emr SD 1999. Vac1p coordinates Rab and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in Vps45p-dependent vesicle docking/fusion at the endosome. Curr Biol 9: 159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski JT, Gomez TS, Schoon RA, Mangalam AK, Billadeau DD 2013. WASH knockout T cells demonstrate defective receptor trafficking, proliferation, and effector function. Mol Cell Biol 33: 958–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plemel RL, Lobingier BT, Brett CL, Angers CG, Nickerson DP, Paulsel A, Sprague D, Merz AJ 2011. Subunit organization and Rab interactions of Vps-C protein complexes that control endolysosomal membrane traffic. Mol Biol Cell 22: 1353–1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pols MS, ten Brink C, Gosavi P, Oorschot V, Klumperman J 2012. The HOPS proteins hVps41 and hVps39 are required for homotypic and heterotypic late endosome fusion. Traffic 14: 219–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteryaev D, Datta S, Ackema K, Zerial M, Spang A 2010. Identification of the switch in early-to-late endosome transition. Cell 141: 497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulipparacharuvil S, Akbar MA, Ray S, Sevrioukov EA, Haberman AS, Rohrer J, Krämer H 2005. Drosophila Vps16A is required for trafficking to lysosomes and biogenesis of pigment granules. J Cell Sci 118: 3663–3673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthenveedu MA, Lauffer B, Temkin P, Vistein R, Carlton P, Thorn K, Taunton J, Weiner OD, Parton RG, von Zastrow M 2010. Sequence-dependent sorting of recycling proteins by actin-stabilized endosomal microdomains. Cell 143: 761–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport D, Auerbach W, Naslavsky N, Pasmanik-Chor M, Galperin E, Fein A, Caplan S, Joyner AL, Horowitz M 2006. Recycling to the plasma membrane is delayed in EHD1 knockout mice. Traffic 7: 52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson S, Winistorfer S, Poupon V, Luzio J, Piper R 2004. Mammalian late vacuole protein sorting orthologues participate in early endosomal fusion and interact with the cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell 15: 1197–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink J, Ghigo E, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M 2005. Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell 122: 735–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas R, van Vlijmen T, Mardones GA, Prabhu Y, Rojas AL, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Raposo G, van der Sluijs P, Bonifacino JS 2008. Regulation of retromer recruitment to endosomes by sequential action of Rab5 and Rab7. J Cell Biol 183: 513–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römer W, Pontani L-L, Sorre B, Rentero C, Berland L, Chambon V, Lamaze C, Bassereau P, Sykes C, Gaus K, et al. 2010. Actin dynamics drive membrane reorganization and scission in clathrin-independent endocytosis. Cell 140: 540–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropers F, Derivery E, Hu H, Garshasbi M, Karbasiyan M, Herold M, Nürnberg G, Ullmann R, Gautreau A, Sperling K, et al. 2011. Identification of a novel candidate gene for non-syndromic autosomal recessive intellectual disability: The WASH complex member SWIP. Hum Mol Genet 20: 2585–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino M, Miaczynska M, Lippe R, Zerial M 2000. Selective membrane recruitment of EEA1 suggests a role in directional transport of clathrin-coated vesicles to early endosomes. J Biol Chem 275: 3745–3748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals D, Eitzen G, Margolis N, Wickner W, Price A 2000. A Ypt/Rab effector complex containing the Sec1 homolog Vps33p is required for homotypic vacuole fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97: 9402–9407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MNJ 2012. The retromer complex—Endosomal protein recycling and beyond. J Cell Sci 125: 4693–4703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MNJ, Harbour ME, Tattersall D, Read E, Bright N 2009. Membrane recruitment of the cargo-selective retromer subcomplex is catalysed by the small GTPase Rab7 and inhibited by the Rab-GAP TBC1D5. J Cell Sci 122: 2371–2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman MNJ, Gautreau A, Billadeau DD 2013. Retromer-mediated endosomal protein sorting: All WASHed up! Trends Cell Biol 23: 522–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setty SRG, Tenza D, Truschel ST, Chou E, Sviderskaya EV, Theos AC, Lamoreux ML, Di Pietro SM, Starcevic M, Bennett DC, et al. 2007. BLOC-1 is required for cargo-specific sorting from vacuolar early endosomes toward lysosome-related organelles. Mol Biol Cell 18: 768–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen A, Lippe R, Christoforidis S, Gaullier J, Brech A, Callaghan J, Toh B, Murphy C, Zerial M, Stenmark H 1998. EEA1 links PI(3)K function to Rab5 regulation of endosome fusion [see comments]. Nature 394: 494–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati T, Schliwa M 2006. Powering membrane traffic in endocytosis and recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 897–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen B, de Renzis S, Nielsen E, Rietdorf J, Zerial M 2000. Distinct membrane domains on endosomes in the recycling pathway visualized by multicolor imaging of Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11. J Cell Biol 149: 901–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg F, Gallon M, Winfield M, Thomas E, Bell AJ, Heesom KJ, Tavaré JM, Cullen PJ 2013. A global analysis of SNX27–retromer assembly and cargo specificity reveals a function in glucose and metal ion transport. Nat Cell Biol 15: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroupe C, Collins K, Fratti R, Wickner W 2006. Purification of active HOPS complex reveals its affinities for phosphoinositides and the SNARE Vam7p. EMBO J 25: 1579–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroupe C, Hickey CM, Mima J, Burfeind AS, Wickner W 2009. Minimal membrane docking requirements revealed by reconstitution of Rab GTPase-dependent membrane fusion from purified components. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 17626–17633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Woolford CA, Jones EW 2004. The Sec1/Munc18 protein, Vps33p, functions at the endosome and the vacuole of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 15: 2593–2605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetsugu S, Gautreau A 2012. Synergistic BAR–NPF interactions in actin-driven membrane remodeling. Trends Cell Biol 22: 141–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tall G, Hama H, DeWald D, Horazdovsky B 1999. The phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate binding protein Vac1p interacts with a Rab GTPase and a Sec1p homologue to facilitate vesicle-mediated vacuolar protein sorting. Mol Biol Cell 10: 1873–1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin P, Lauffer B, Jäger S, Cimermancic P, Krogan NJ, Zastrow von M 2011. SNX27 mediates retromer tubule entry and endosome-to-plasma membrane trafficking of signalling receptors. Nat Cell Biol 13: 715–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam EM, Broeke Ten T, Jansen K, Spijkers P, Stoorvogel W 2002. Endocytosed transferrin receptors recycle via distinct dynamin and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 277: 48876–48883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonderheit A, Helenius A 2005. Rab7 associates with early endosomes to mediate sorting and transport of Semliki forest virus to late endosomes. PLoS Biol 3: e233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner W 2010. Membrane fusion: Five lipids, four SNAREs, three chaperones, two nucleotides, and a Rab, all dancing in a ring on yeast vacuoles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26: 115–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurmser AE, Sato TK, Emr SD 2000. New component of the vacuolar class C-Vps complex couples nucleotide exchange on the Ypt7 GTPase to SNARE-dependent docking and fusion. J Cell Biol 151: 551–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefian J, Troost T, Grawe F, Sasamura T, Fortini M, Klein T 2013. Dmon1 controls recruitment of Rab7 to maturing endosomes in Drosophila. J Cell Sci 126: 1583–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu I-M, Hughson FM 2010. Tethering factors as organizers of intracellular vesicular traffic. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26: 137–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zech T, Calaminus SDJ, Caswell P, Spence HJ, Carnell M, Insall RH, Norman J, Machesky LM 2011. The Arp2/3 activator WASH regulates α5β1-integrin-mediated invasive migration. J Cell Sci 124: 3753–3759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigerer A, Gilleron J, Bogorad RL, Marsico G, Nonaka H, Seifert S, Epstein-Barash H, Kuchimanchi S, Peng CG, Ruda VM, et al. 2012. Rab5 is necessary for the biogenesis of the endolysosomal system in vivo. Nature 485: 465–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zick M, Wickner W 2012. Phosphorylation of the effector complex HOPS by the vacuolar kinase Yck3p confers Rab nucleotide specificity for vacuole docking and fusion. Mol Biol Cell 23: 3429–3437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]