Abstract

Complete reference maps or datasets, like the genomic map of an organism, are highly beneficial tools for biological and biomedical research. Attempts to generate such reference datasets for a proteome so far failed to reach complete proteome coverage, with saturation apparent at approximately two thirds of the proteomes tested, even for the most thoroughly characterized proteomes. Here, we used a strategy based on high-throughput peptide synthesis and mass spectrometry to generate a close to complete reference map (97% of the genome-predicted proteins) of the S. cerevisiae proteome. We generated two versions of this mass spectrometric map one supporting discovery- (shotgun) and the other hypothesis-driven (targeted) proteomic measurements. The two versions of the map, therefore, constitute a complete set of proteomic assays to support most studies performed with contemporary proteomic technologies. The reference libraries can be browsed via a web-based repository and associated navigation tools. To demonstrate the utility of the reference libraries we applied them to a protein quantitative trait locus (pQTL) analysis, which requires measurement of the same peptides over a large number of samples with high precision. Protein measurements over a set of 78 S. cerevisiae strains revealed a complex relationship between independent genetic loci, impacting on the levels of related proteins. Our results suggest that selective pressure favors the acquisition of sets of polymorphisms that maintain the stoichiometry of protein complexes and pathways.

Keywords: S. cerevisiae, selected reaction monitoring, SRM, MRM, spectral library, peptide library, mass spectrometric map, protein QTL

Experience from different fields of experimental research suggests that generally accessible, complete, validated reference maps or reference datasets of the components of a system under study can be transforming. Such reference resources generally increase the confidence and transparency of the analysis of subsequently acquired datasets. Examples of “gold standard” reference maps include the complete genomic sequence of an organism[1, 2], libraries of the spectroscopic properties of molecules in analytical chemistry and biochemistry (e.g. http://webbook.nist.gov; http://acdlabs.com), or databases of drug structures (e.g. http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), used in forensic or environmental chemistry. Such reference maps as well as methods to navigate them constitute reliable assays to probe any sample for the presence of the molecules contained in the map. Reference maps therefore facilitate the extraction of a maximal amount of true information from any sample at a minimal error rate. Obviously, reference maps are particularly useful if they are complete, i.e. cover every compound relevant for the mapped space.

In proteomics, the generation of reference maps covering a complete proteome has been challenging and attempted in two ways. The first is based on the use of antibodies to detect target proteins in biological samples using immunoassays [3, 4]. This is exemplified for the human proteome by the Protein Atlas project[5]. For the S. cerevisiae proteome, a variant of this approach involved quantitative Western blotting of a tandem affinity purification-tag engineered into each yeast gene[6] with specific advantages and limitations associated with the tagging step. The second approach to the generation of proteome maps is mass spectrometry (MS)-based shotgun proteomics, where in-depth mapping of a proteome has been attempted via the collection of large numbers of fragment ion spectra from multiple experiments, and their unambiguous assignment to peptide sequences[7-9]. Such reference spectral datasets, acquired on a suitable instrument platform, can be used in discovery driven experiments to analyze subsequently acquired fragment ion spectra via spectral matching[10-13], or in targeted measurements, to specifically monitor optimal peptide and fragment ion signals for any protein of interest by selected reaction monitoring (SRM)[14-16].

At present, neither the antibody, nor the MS-based approach have reached complete proteome coverage. Saturation has been apparent at approximately two thirds of the proteome predicted from the genome of yeast [6, 9, 17] and other microbes or eukaryotic species [18, 19], and much lower coverage has been achieved for other proteomes, including the human proteome[17]. However, complete reference datasets would be essential to support the reliable and reproducible measurement of any protein in a proteome, and their dynamic change as a function of cellular state and across different laboratories.

Generation of a mass spectrometric map for the yeast proteome

We used a strategy based on high throughput peptide synthesis and mass spectrometry to generate a reference set of fragment ion spectra covering essentially the complete S. cerevisiae proteome as predicted by the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) [20]. The reference spectra were generated in both a linear ion trap (LIT)-type mass spectrometer, the instrument mainly used for discovery-based proteomics and in a triple quadrupole (QQQ) instrument, the main instrument used for selected reaction monitoring (SRM)-based targeted proteomic workflows [21]. The respective spectral libraries, along with the corresponding analysis tools for discovery- and hypothesis-driven proteomics, therefore, constitute the first complete set of proteomic assays for any species for the systematic, reliable and reproducible measurement of a proteome.

To generate the reference spectral data sets we first defined the yeast proteome as the ensemble of the 6,607 protein sequences, each one associated with an open reading frame (ORF), in the yeast genome. These included: i) 4,861 “verified” ORFs, encoding proteins with supporting experimental evidence as annotated by SGD; ii) 936 “uncharacterized” ORFs, likely encoding an expressed protein, as suggested by orthologues in other species, but with no direct experimental evidence, and iii) 810 “dubious” ORFs for which neither experimental nor homology-derived evidence suggests that the protein is produced.

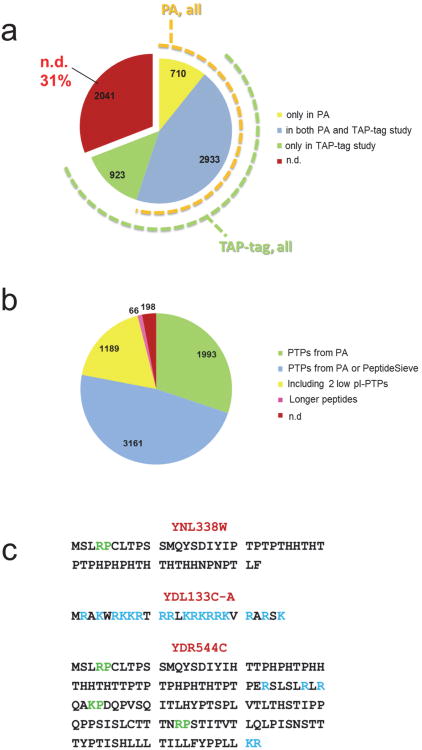

To guide the selection of representative peptides for each protein, we first classified yeast proteins based on their detectability using two large-scale reference datasets: the largest repository of consistently searched proteomic data, PeptideAtlas (PA, 2009 release [22]) including proteomic datasets produced using in-depth fractionation (e.g. see [9]), and the largest dataset of antibody-based protein abundance measurements in yeast (Fig. 1a) [6]. The coverage of yeast ORFs was below two thirds of the ORFeome for each of the two orthogonal datasets, suggesting that the proteome of yeast grown under standard laboratory conditions has been exhaustively mapped out by automated peptide sequencing (58.6% coverage of predicted yeast ORFs) or by antibody-based detection (55.1% coverage of predicted yeast ORFs), whereby the two orthogonal data sets showed a high degree of overlap (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1. Yeast proteome statistics and peptide selection criteria.

(a) Detectability of the yeast proteome by large-scale proteomic and antibody-based approaches, as derived from the PeptideAtlas database and from Ghaemmaghammi et al (5). (b) Selection of PTPs for the yeast proteome. For each protein we selected up to eight most frequently observed PTPs in the PeptideAtlas (PA) that were also conforming to defined length constraints (see Methods). For proteins with zero to five PTPs in PA which had been detected via the antibody-based approach[5] we selected up to five additional PTPs predicted with PeptideSieve[26]. For proteins undetected by both proteomic and antibody-based methods, we predicted five PTPs, forcing the selection of at least two of these to a pI below 4.5, where available. For the remaining unmatched ORFs we relaxed the peptide length constraints (see Methods), and repeated the previous steps. The pie chart represents proteins associated to all S. cerevisiae ORFs. Proteins for which peptides were selected based only on PA evidence, (green), on PA evidence or PeptideSieve prediction (blue); on PeptideSieve prediction, including two peptides with pI<4.5; Proteins for which longer peptides were allowed (pink); proteins not covered by our peptide selection criteria (red). (c) Example of protein sequences that lack suitable proteotypic peptides. Trypsin cleavage sites are indicated in blue; RP/KP bonds, which prevent trypsin cleavage, are in green.

Next, we selected for each protein an optimal set of up to eight peptides which had favorable MS properties and unique occurrence within the compiled protein sequence database (proteotypic peptides, PTPs) [23, 24]). Where available, we selected PTPs from empirical data and we predicted them for proteins for which no such data was available (Fig. 1b). For proteins neither detected by the MS nor the antibody-based methods, we selected at least two peptides with an isoelectric point (pI) below 4.5, where available (Fig. 1b). The choice of acidic peptides maximizes the probability of detecting the corresponding proteins if the peptide samples are first fractionated by off-gel electrophoresis [16, 25, 26]. About 200 proteins remained refractory to these selection criteria. Among these are proteins that generate tryptic peptides that are too long or too short for a MS analysis with standard protocols (see examples in Fig. 1c). The final peptide set, comprising ∼28,000 peptides was synthesized on a small scale, predominantly using the SPOT-synthesis technology[27] to assemble a library of peptides representing 97% of the predicted yeast proteome (Fig. 2).

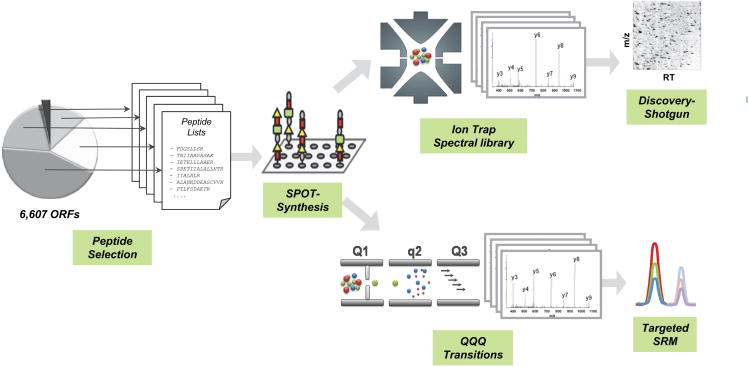

Figure 2. Generation of a reference mass spectrometric map for the yeast proteome.

The schema shows the sequential steps of map generation: peptides were selected based on the known ORFeome and the criteria listed in the text; peptides were synthesized on a small scale using the SPOT-synthesis technology; the peptide library was analyzed on a QQQ MS and an ion trap-type mass spectrometer to generate the corresponding consensus spectral libraries; existing, quality filtered datasets were added to the synthetic spectral libraries; the QQQ library was used to extract the best coordinates for SRM measurements of yeast proteins; the consensus ion trap library can be used for spectral searches of any LC-MS/MS dataset from S. cerevisiae.

We next used these peptides and two types of electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometers to generate two reference spectral libraries, each one supporting a commonly used proteomic method. We used a LIT-type instrument (LIT-Orbitrap hybrid) to generate reference spectra for spectral library searching of fragment ion spectra acquired in discovery mode. We employed a QQQ-type instrument (QTRAP hybrid) to generate fragment ion spectra to extract optimal coordinates for the targeted measurement of specific yeast proteins via SRM (Fig. 2). For data acquisition in the LIT-Orbitrap we pooled 500 crude synthetic peptides and subjected each pool to LC-MS/MS analysis, using inclusion lists to trigger the acquisition of fragment ion spectra of the respective peptides [28, 29]. We aimed at acquiring multiple spectra per peptide for the construction of spectral libraries. Spectra were assigned to peptide sequences by sequence database searching. We combined the output of three different search engines and processed the data with the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline (TPP[30]), (see Methods). The resulting composite list of assignments was filtered to a global false discovery rate at the peptide-spectrum match (PSM) level of 0.022% and at the peptide level of 0.24%, estimated based on decoy counts. To maximize proteome coverage of the spectral library we combined the data obtained from the synthetic peptide set with high-quality fragment ion spectra acquired in LIT instruments from digests of yeast extracts that had been contributed to the Yeast PeptideAtlas[31] (2009 version) and with quality-filtered consensus spectra from the NIST yeast ion-trap spectral library (http://peptide.nist.gov/, build date 2009-10-19). For all assigned peptides, except those from the NIST library, we computed consensus spectra using the tool SpectraST[11], whereby multiple fragment ion spectra matching the same precursor were combined into a high-quality, de-noised consensus spectrum. The final spectral library contained consensus spectra for 100,815 peptides, covering with at least five, four, three, two and one peptide, 78, 84, 90, 95 and 97%, respectively, of the 6,607 sequences in the yeast proteome (Fig. 3a). Therefore, only 3% of the S. cerevisiae ORFeome is not covered by the spectral library, which makes it the most complete proteomic reference map for any species to date.

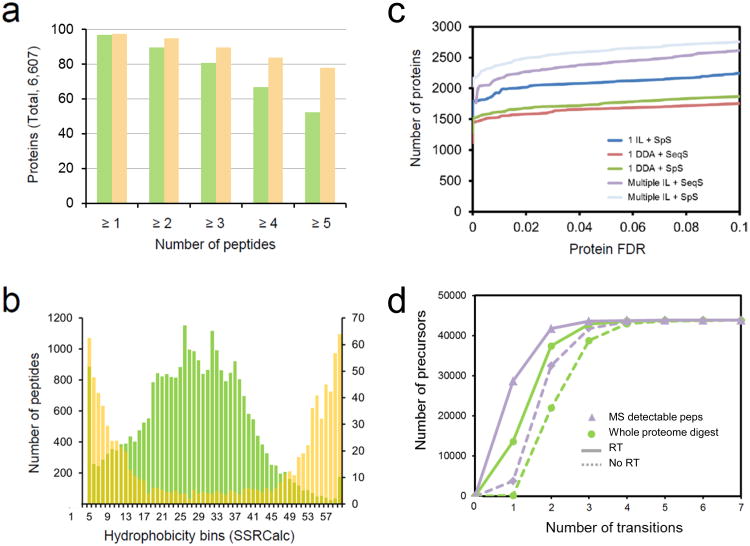

Figure 3. Composition and usage of the spectral libraries.

(a) Number of peptides per protein in the SRM assay (green) or ion trap (yellow) library. The percentage is relative to the total of 6,607 theoretical S. cerevisiae proteins. (b) Hydrophobicity distribution for all selected peptides (green) and for those that could not be detected with our QQQ-workflow (yellow). Hydrophobicity is expressed as SSRCalc[64] score bins. % values are relative to the total number of peptides synthesized in each bin. (c) Number of protein identifications from an unfractionated whole yeast digest by various methods, as a function of decoy-estimated protein false discovery rates. The instrument used was an Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Scientific). DDA, conventional data-dependent acquisition; IL, inclusion list-based acquisition; SeqS, sequence database searching against the yeast theoretical proteome, performed with the engine X!Tandem[36]; SpS, spectral searching against the IT library, with the tool SpectraST[62]. (d) Minimal number of transitions needed to uniquely identify precursor ions in the QQQ library. A cumulative plot of the minimal number of transitions forming a unique ion signature (UIS) is shown for all the precursors in the QQQ SRM library. Transitions were selected with decreasing intensity from the SRMAtlas and uniqueness for a set of transitions was established if no other precursor within a Q1/Q3 window ± 0.7 m/z (and SSRCalc-predicted elution time window, for time-scheduled acquisition) produced transitions that contained all of the query transitions. The analysis is shown for two different backgrounds: all yeast peptides potentially detectable by MS, as derived from the yeast PA (purple) and all theoretical tryptic peptides in the yeast proteome (green). RT/no RT indicate whether time-scheduled SRM acquisition is considered.

Next, we used a QTRAP instrument to generate QQQ full fragment ion spectra from the synthetic peptide set and used these spectra to extract the coordinates required to build MS assays for the detection of yeast proteins by SRM. Samples containing ∼100 crude synthetic peptides were analyzed twice (see Methods) on the instrument operated in SRM-triggered MS/MS mode, using Q2 fragmentation, as previously described[32]. The data were combined[11] with the complementary dataset acquired from extracted yeast proteins contained in the original MRMAtlas[32] to create a homogeneous consensus spectral library from spectra acquired in a QQQ instrument. From this data set 260,077 spectra were assigned to 28,216 peptide sequences by sequence database searching to a PSM FDR of 0.076% and an FDR of 0.35% at the peptide level, estimated based on decoy counts. We then extracted from the resulting library for each peptide the fragment ion masses, their relative signal intensities, the charge state distribution and the chromatographic peptide elution time, which collectively constitute a SRM assay for a peptide. Overall, SRM assays for 28,216 peptides were successfully developed. Assays for minimally five, four, three, two and one PTP(s) per protein were developed, respectively, for 52, 67, 81, 90 and 97% of yeast proteins (Fig. 3a).

The majority of the synthesized peptides generated both an SRM assay and an ion trap reference spectrum. Our peptide selection criteria, based on empirical or predicted MS observability resulted in a peptide set that preferentially contained peptides of intermediate hydrophobicity (Fig. 3b). The fraction of synthesized peptides that could not be detected (∼1,630) showed indeed a bias towards extreme calculated[33] hydrophobicity values (Fig. 3b), indicating that very hydrophilic or very hydrophobic peptides are less well suited for chemical synthesis and/or LC-MS analysis than those of moderate hydrophobicity. Spectra acquired from the crude synthetic peptide preparations were indistinguishable from those acquired from the corresponding natural sources (Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Fig. 1 and see also [32]).

The two datasets of LIT and QQQ derived spectral reference libraries were compiled into two builds of a publicly accessible database, PeptideAtlas (www.peptideatlas.org)[17]. The two PeptideAtlas builds, the spectral libraries and the raw MS files can be downloaded in different formats (Supplementary Methods). The data can be browsed interactively via query pages and summary views, as described in detail by Farrah et al.[34]; and finally, the data can be accessed via web services[35] (see Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Figs. 2-6). A summary of and links to all available data products can be found at http://www.srmatlas.org/yeast/.

Performance Features of he Reference Spectral Libraries

We assessed the performance of the LIT spectral library for the analysis of datasets generated by discovery-driven proteomics by analyzing a tryptic digest of a total yeast extract using conventional data-dependent LC-MS/MS (DDA) .By spectral library searching against the LIT library we identified from a single DDA run 1,617 unique proteins at an FDR of 1% (Fig. 3c). Analyzing the same spectra by conventional database searching with the tool X!Tandem[36] against the SGD database identified 1,529 proteins at the same protein FDR. This indicates that spectral library searching of conventionally acquired data performed equivalently or slightly better compared to classical database search methods (Fig. 3c) and that restricting the analysis to our chosen PTPs does not diminish the number of proteins identified. Similar results were obtained on five replicated DDA runs performed on the same sample (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Next, we used the spectral library to assess the possibility of deriving a more effective shotgun data acquisition and analysis strategy compared to the standard approach. We determined how many of the peptides contained in our library could be identified in an unfractionated yeast sample on an instrument typically used for discovery proteomic measurements. We analyzed the yeast proteome extract in 22 MS runs, using 22 distinct inclusion lists, collectively containing all precursor ions corresponding to the best five peptides per protein in the library, based on number of observations in PA or on the PeptideSieve prediction score. Spectral library searching of the thus acquired spectra identified 2,509 unique proteins (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 8) at a protein FDR of 1.2%. We then compiled a new, reduced inclusion list containing the peptide ions identified in the prior step (Supplementary Dataset). Using this reduced inclusion list we could identify in a single MS run of 2 hrs duration of an unfractionated yeast digest, 1,987 uniquely mapped proteins at FDR 1.1% by spectral matching against the spectral library (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Figs 8 and 9). This number of proteins is about 30% higher than that achieved by conventional workflow of DDA followed by sequence database searching. The spectral library search of this single file of about 34,000 MS/MS spectra took 5 minutes on a 1 CPU (about 0.01 second per spectrum). The achieved data analysis speed is therefore higher than the typical data acquisition speed for such an experiment, which implies the feasibility of conducting on-the-fly data analysis with our approach, in discovery-based proteomic experiments. Therefore, the proteomic data acquisition strategy consisting of a single optimized inclusion list and spectral matching generated an unprecedented number of protein identifications per hour of data acquisition time and substantially reduced the computational overhead compared to shotgun sequencing methods.

We next simulated the utility of the SRM assay library to identify the components of the yeast proteome by targeted mass spectrometry. We have previously shown that LC-SRM has the sensitivity and the dynamic range to detect proteins to concentrations below 100 copies per cell in unfractionated digests of the yeast proteome, and proteins with approximately tenfold lower concentration after 1-step fractionation [16]. Here we analyzed the specificity of the SRM transitions extracted from our QQQ spectral library for the analysis of the yeast proteome, using the SRMCollider tool[37]. We computationally determined the uniqueness of our library SRM assays against two backgrounds of different complexity (Fig. 3d), and simulating SRM acquisition with or without time scheduling[38]. The two levels of computed background consisted of: (1) all yeast peptides observed by MS, including modified peptides and unspecific digestion products (lower complexity background) and (2) all theoretical yeast tryptic peptides (higher complexity background). We implemented the unique ion signature (UIS) approach[37, 39], which determines, for a given set of query transitions (the query SRM assay), the number of interfering peptides in the background database, that contain the same transitions as the query assay, within a given m/z tolerance. We thus calculated the minimal number of highest intensity SRM transitions to be measured for each peptide in the SRMAtlas to generate a unique SRM assay for the peptide (Supplementary Discussion). As shown in Fig. 3d, 97.8% and 88.5% of the peptide precursors can be uniquely detected using the three highest transitions in our library, with and without time scheduled acquisition, respectively, even in the high complexity background. These fractions further increase if the less complex background scenario is considered, indicating that our SRM library provides assays for the unambiguous identification of ∼97% of the SGD predicted yeast proteome. A table containing the suggested number of transitions to measure each peptide is available for download at www.srmatlas.org/yeast.

Application of the reference maps to quantitative trait locus analysis

To demonstrate the value of the two libraries in discovery and targeted proteomic experiments, we applied them to a protein-based quantitative trait analysis in S. cerevisiae. Protein quantitative trait locus (pQTL) studies aim at correlating protein abundance with genetic variation and thus critically rely on the capability to precisely measure protein concentrations throughout large numbers of samples. Previous pQTL studies[20, 40] suffered from an irreproducible detection of peptides across samples and a bias for abundant proteins. To overcome these limitations we applied a two-step workflow based on our spectral libraries to a genetically diverse S. cerevisiae population of 78 yeast strains obtained by crossing a wild isolate (RM11-1a, hereafter RM) and a strain isogenic to the standard S288 laboratory strain (BY4716, hereafter BY)[41]. To identify proteins whose cellular concentrations are likely affected by QTLs in the RMxBY cross (see Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Fig. 10a), we performed a discovery proteomic experiment on the two parental yeast strains and 16 segregants selected so as to maximize the genetic diversity between them (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Using the single inclusion list described above and spectral matching against the LIT library we identified ∼2,500 uniquely mapped proteins at 1% FDR and quantified the abundance of the corresponding peptides throughout the different samples using a label-free approach (Supplementary Methods). We did not consider peptides that were polymorphic in the RM background, peptides with incomplete measurements, and proteins for which no high-quality precursor ion features could be detected. We ranked the remaining ∼2,100 proteins based on the variability of their concentrations across the sample strains, while correcting for the number of peptides that were measured per protein (Supplementary Fig. 11a,b). To identify cellular processes and pathways that were particularly affected by genetic variation we analyzed the 150 proteins showing the highest variability for i) a GO-based functional enrichment (Supplementary Table 1), ii) a metabolic pathway enrichment (Supplementary Table 2), and iii) protein complex and module overrepresentation tests using protein-protein binding data (Supplementary Table 3). Proteins involved in NADH oxidation, arginine/ornithine biosynthesis and amino acid metabolism were significantly enriched among the most variable proteins. We selected a set of 48 proteins that are members of the most highly enriched pathways and sub-networks. These proteins covered all levels of cellular abundances (Supplementary Fig. 12) and included a protein from one of the targeted pathways (Arg3p) that was not detected in the discovery phase (Supplementary Table 4). Next, we used SRM assays (Supplementary Dataset) from the full proteome map described above for the targeted quantification of the 48 target proteins throughout the complete collection of segregant and parental strains. The SRM-based quantification resulted in a highly consistent and comprehensive dataset (Figure 4a) and allowed for the precise determination of inter-sample variations of protein abundances (Supplementary Discussion).

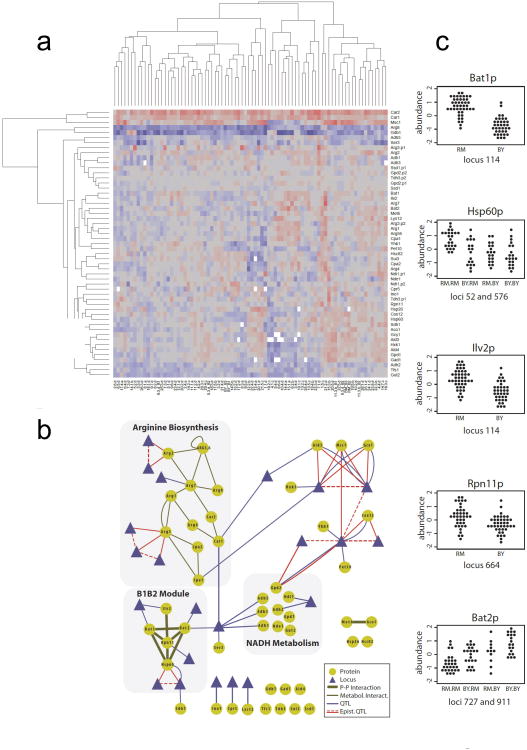

Figure 4. Quantitative trait analysis from the targeted proteomic dataset.

(a) Two-way cluster analysis of summarized protein abundances measured by SRM in 82 samples (78 strains) of the RMxBY cross. Columns are clustered according to the samples, and rows according to the proteomic traits. Abundance levels are color coded in a blue-red gradient, red corresponding to high abundance; white indicates missing data. The completeness of the dataset reaches 99.50% even though the summarization procedure was conservative and generated additional missing values. (b) Network representation of protein abundance QTL for the 48 targeted proteins. Metabolic interactions were manually reconstructed from BioCyc (http://biocyc.org/). Epistatic pQTL (red edges) always connect 2 loci that are in espistasis with respect to a protein abundance trait. (c) Abundances of the proteins of the B1B2 protein module in the parental strains and segregants. For each protein, abundances are shown for groups of strains separated according to their genotype at the respective pQTL. A pair of interacting loci was linked to the variations of Hsp60p. The epistatic interaction is clearly visible when the RM allele is inherited at both loci. In contrast, the effects of the two loci linked to Bat2p are additive. Interestingly, the directionality of regulation is shared by all components of the module but Bat2p (over expression when the RM alleles are inherited). Bat1p and Bat2p are paralogs catalyzing the same metabolic reaction in opposite directions (see Supplementary Discussion).

Epistatic interactions between genes are important factors contributing to the variation of complex traits and they are thought to partly explain ‘missing heritability’ observed in traditional association studies[42, 43]. However, detecting epistasis in QTL studies is notoriously difficult, mostly due to lack of sufficient statistical power. We reasoned that because of the high precision of SRM data and the relatively large number of samples it should be possible to detect epistasis in our data. We therefore extended a machine learning-based QTL mapping method that we previously developed[44, 45] to also report epistatic interactions between pairs of loci affecting a common protein (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). Based on both simulated and real data our QTL mapping method showed superior performance compared to the traditional exhaustive two-locus approach (Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16). Application of this framework to our pQTL data identified 32 pQTLs involving single loci (FDR < 0.15) and 10 pairs of epistatic pQTLs (FDR < 0.2) (Figure 4b). In total, 28 of the 48 proteins were under control of at least one pQTL and 23 distinct genomic regions were involved. Interestingly, pQTLs were detected for Arg3p, the protein that could not be detected in the shotgun proteomics pre-screen – a finding that underlines the value of a comprehensive map for targeted proteomics. These results show that protein concentrations are strongly affected by natural genetic variation, indicating that epistatic interactions between loci affecting protein levels are a common phenomenon. A protein module consisting of Bat1p, Bat2p, Rpn11p, Hsp60p and Ilv2p—which we termed ‘B1B2 module’ —caught our attention, because all of its components were involved in at least one significant pQTL (Figure 4b). The module functionally connects to protein turnover and amino-acid metabolism and is physically connected to mitochondria (Supplementary Discussion). Interestingly, six different genomic regions contained polymorphisms independently affecting the levels of the different proteins in the module. Detailed analysis of the proteomic and genomic data revealed that segregant strains carrying the BY alleles at the respective loci expressed consistently lower levels for all proteins being part of this module, with Bat2p being the only exception (Figure 4c). Importantly, Bat2p favors the reverse metabolic reaction catalyzed by Bat1p (catabolism and anabolism of branched-chain amino acids, respectively, Supplementary Discussion) [46]. Thus, the two parental strains have acquired a set of independent genetic variations consistently affecting protein levels of the B1B2 module, presumably for maintaining a consistent stoichiometry. Our data contained a second example of such coordinated acquisition of independent polymorphisms affecting the regulation of the alcohol dehydrogenases (NADH module, Figure 4b): Adh1p, Adh3p and Adh5p, which are up-regulated in in the RM-background, can catalyze the last reaction of the ethanol production pathway, while Adh2p, which is linked to another locus and down-regulated in the RM background, catalyzes preferentially the reverse reaction (Supplementary Fig. 17)[47-49].

Discussion

In this study we describe the first map of validated reference fragment ion spectra for the near complete proteome of any species. We generated two versions of this map, each covering 97% of the SGD-predicted proteome. The first version supports discovery-driven, shotgun proteomics methods. The second supports targeted proteomics experiments via SRM. The two spectral libraries, therefore, support most proteomic studies performed with contemporary technologies.

The library of LIT consensus fragment ion spectra can be used for spectral matching of S. cerevisiae shotgun data. While the benefits of spectral matching, such as speed, confidence or number of proteins identified, have been recognized for some time, the incomplete proteome coverage of previous libraries has precluded the broad application of the technique. The spectral library described in this study eliminates this limitation. Currently, the library does not include modified peptide sequences, which precludes their identification by spectral matching. However, in principle, the same approach can be applied also to generate spectral libraries for modified peptides. Alternatively, after spectral matching and identification of sample proteins, one may search for post-translational modifications among the spectra remaining unassigned by conventional sequence searching, but considering only the subset of proteins present in the sample.

The library of SRM assays significantly expands the capabilities of SRM-based targeted proteomic experiments. So far, a major bottleneck precluding the widespread application of SRM has been the paucity of available SRM assay coordinates and the effort required to establish them. The comprehensive set of yeast SRM assays presented here overcomes this limitation and supports targeting for detection and quantification of any deliberately chosen yeast protein or protein set, in hypothesis-driven experiments. The example of Arg3p is a perfect case in point. In addition, the availability of QQQ fragment ion (and thus transition) intensities and peptide elution times will be crucial for the automated scoring and statistical evaluation of large-scale SRM datasets with respect to their false discovery rate[50]. A limitation of our SRM assay library is that we do not experimentally determine the sensitivity and specificity of each assay. In our view, these properties cannot be generally defined, as they are strongly sample (e.g. low complexity pull-down vs. whole proteome extract) and platform (e.g. chromatography, resolution, tuning) dependent. We therefore prefer that these two assay features are verified locally, in the context of any particular sample. We do provide, however, an estimated specificity of each SRM assay by simulation, using a worst-case scenario consisting of an unfractionated yeast proteome without any separation in retention time. The simulation is based on certain assumptions (Supplementary Discussion) and it does not necessarily reflect the full complexity of a biological sample. Therefore, the suggested number of transitions to be measured can be regarded as a lower bound. We recommend measuring at least 3-4 transitions per peptide and, importantly we provide the relative transitions intensities, information that significantly increases the specificity of each assay. In addition, since our reference spectra and browsing tools support the selection of multiple intense transitions for each peptide, one or more can be discarded if found to be locally unspecific.

The content of both libraries depends on the quality of the S. cerevisiae genome annotation. If the annotation is revised, the map can easily be amended to include new genes or remove inaccuracies. Further, we envision that the present map, which contains assays for hypothetical ORFs, can be used to conclusively detect putative proteins in any sample of interest and to thus determine whether and under which conditions predicted proteins are expressed. Finally, the libraries presented here will constitute a useful blueprint for studying peptide fragmentation properties in quadrupoles and ion trap mass spectrometers and will support the development of new acquisition methods relying on the knowledge of peptide fragmentation patterns. A first instance of such a method, SWATH-MS[51] has already been described.

We applied the libraries generated here to a pQTL analysis of S. cerevisiae. Previous yeast pQTL studies have used a method that relies on the mathematical alignment of shotgun LC-MS data sets to evaluate protein levels across the RMxBY library[20, 52]. A disadvantage of employing shotgun proteomics is the inconsistent measurement of proteins across samples, which results in a comparably large number of missing data points and thus reduces statistical power. Moreover, the re-analysis of these datasets showed that, in contrast to the approach presented here, the reliability, the completeness of the measurements, and most importantly the pQTL detection were biased towards more abundant proteins (Supplementary Figure 18). Our approach, based on the use of the libraries in a discovery and a targeted step, respectively, enabled the identification and precise targeted quantification of proteins spanning a broad range of abundances throughout a large number of samples, at high precision and comprehensiveness. This analysis resulted in the detection of novel pQTLs, facilitated the discovery of new epistatic interactions, and suggested that selective pressure favors the acquisition of sets of polymorphisms that maintain the stoichiometry of protein complexes and pathways. Thus, the B1B2 module and the alcohol dehydrogenases provide examples for the coordinated adaptation of a pathway through a series of independent mutations (Supplementary Discussion).

The comprehensive proteome map generated here, the described publicly accessible tools to navigate it and the new data acquisition and processing strategies that are enabled by such resources expand the capabilities of current proteomics experiments. These concepts and their extensions to other organisms will be catalytic for transitioning proteomics from perpetual proteome re-discovery to a new era of accurate and non-redundant proteome measurement. We expect that a new generation of proteomic technologies will emerge from these maps, that show improved performance, confidence and ease of use and will contribute to the widespread application of proteomics approaches also in non-specialized laboratories.

Supplementary Methods

In silico analysis of the yeast proteome

A list containing protein sequences associated with all S. cerevisiae ORFs was downloaded from the Yeast Genome Database (www.yeastgenome.org). A list of proteins identified in the PA database was downloaded from www.peptideatlas.org (S. cerevisiae build[31], version 2009). Protein identifications in PA based solely on non-unique or nonfully tryptic peptides or peptides identified via enrichment of cysteine-containing peptides (“ICAT” protocol[53]) were not considered. A list of proteins detectable via a tandem-affinity purification (TAP)-tag purification step was obtained from ([6]). Proteins observed in the PA database or via the TAP-tag protocol were matched to the list of all yeast ORFs and the coverage and overlap of the two protein sets calculated.

Peptide selection

The yeast proteome contained all 6,607 protein sequences associated to protein-coding open reading frames (ORFs), as reported by the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD, version July 1, 2009, http://www.yeastgenome.org/). For each protein a set of PTPs was selected based on the following criteria. Only fully tryptic peptides, with no missed cleavages, unique to a particular protein, and with a length between 6 and 18 amino acids, were considered. For proteins previously observed in PA (S. cerevisiae PA build[31]), the up to eight PTPs most frequently observed were selected. Cysteine-containing peptides in PA deriving from ICAT[53] experiments and single-observation peptides were not considered. For proteins observed in PA by less than five PTPs, but observed via the antibody-based approach[6], we selected five peptides, prioritizing those observed in PA and selecting the remaining with PeptideSieve[24]. Only peptides with a PeptideSieve score > 0.3 were considered. For proteins detected neither in PA nor by Ghaemmaghami et al.[6] we selected five peptides based on PeptideSieve of which at least two had a calculated pI< 4.5. Peptide pIs were calculated as in ([54]). For the remaining proteins, which did not contain peptides fulfilling the above criteria, the peptide selection was repeated relaxing the length constraints to 22 and 44 amino acids, for predicted and observed peptides, respectively. A small set of synthetic non-proteotypic peptides, available in the laboratory from previous studies, was added to the peptide synthesis set library. Among the 6,607 ORFs, 70 are exact protein-level duplicates of another ORF from a different chromosomal location (140 ORFs involved in duplication). Since these cannot be differentiated at the protein level, peptides for these proteins are mapped to all instances and not penalized as not being uniquely mapping. Further, these duplicates are counted twice when calculating percent proteome coverage (i.e. the duplicates are retained in the numerator and denominator).

Chemical synthesis and sample preparation of the peptide library

The final set of ∼28,000 selected PTPs was synthesized using the SPOT-synthesis [27], recovered from the solid support and used in an unpurified form. The synthesis products were lyophilized in a 96-well plate format (∼50 nmol of each peptide/well). C-terminal peptides were synthesized using classical bead synthesis. All peptides were synthesized by JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany. Peptides were resuspended in 20% acetonitrile, 1% formic acid, vortexed for 20 minutes and sonicated for 15 minutes in each 96-well plate. Aliquots of the peptides contained in each well were mixed to generate 100- or 500-peptides mixtures, evaporated on a vacuum centrifuge to dryness, resolubilized in 0.1% formic acid and immediately analyzed. A consistent set of nine synthetic peptides (AAVYHHFISDGVR, HIQNIDIQHLAGK, TEVSSNHVLIYLDK, GGQEHFAHLLILR, TEHPFTVEEFVLPK, TTNIQGINLLFSSR, NQGNTWLTAFVLK, LVAYYTLIGASGQR, ITPNLAEFAFSLYR) with elution times spanning the whole solvent gradient was spiked into each mixture to facilitate the correlation of relative retention times between LC-MS/MS runs.

Orbitrap MS analysis of the peptide library

Samples containing 500 peptides each were prepared and analyzed in an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source. Chromatographic separation of peptides was obtained with the same LC setup as above. Five MS/MS spectra were acquired in the linear ion trap per each FT-MS scan, the latter acquired at 30,000 FWHM resolution settings. One microscan was acquired per each MS/MS scan and repeat count was set to 3 to generate multiple MS/MS-scans for each peptide ion. Charge state screening was employed, including all multiple charged ions for triggering MS/MS attempts and excluding all singly charged precursor ions, as well as ions for which no charge state could be determined. Only peptide ions exceeding a threshold of 150 ion counts were allowed to trigger MS/MS-scans, followed by dynamic exclusion for 15 seconds. Inclusion lists containing the precursor ion masses in both the doubly and triply charged state of each peptide in a sample were prepared. The lists containing up to 1,000 precursors per run with a mass range of 250 to 1600 m/z were used to trigger MS/MS attempts.

Compilation of the ion trap spectral library

Raw MS data were converted to mzXML[55] format by the tool ReAdW, available within the TPP[56]. Spectra were assigned to peptide sequences by sequence database searching by three search engines, SEQUEST[57], X!Tandem[36] with the K-score[58], and OMSSA[59]. The sequence database was generated from the known sequences of the synthetic peptides, whereby each “protein” was a concatenation of the batch of 500 synthetic peptides analyzed in the same MS run. An equal-size shuffled decoy database (preserving the locations of tryptic sites) was added. A tolerance of 2.5 Da and 0.5 Da were used for the monoisotopic precursor and fragment ion masses,respectively. Semi-tryptic peptides were allowed. Carbamidomethylation of cysteines (+57.0215 Da) was set as a fixed modification.

The search results were post-processed separately with the Trans Proteomic Pipeline[56] tool PeptideProphet[60] to assign probabilities of being correct to each peptide-spectrum match (PSM), and the results merged with the TPP-tool iProphet[61]. Also, for this dataset, an additional model was added to take advantage of the expectation that all correct peptide identifications in the same run should come from the same “protein” in the specially created sequence database. An iProphet probability cutoff was applied, such that the set of spectrum identifications retained had a decoy-estimated FDR of 0.00022. SpectraST [62] was used to compile these spectra into a spectral library, whereby replicates (spectra from the same peptide ions) were merged to form consensus spectra. All library spectra were then simplified to retain the top 50 peaks only[11]. No other quality filters were employed. To increase the proteome coverage, spectral libraries built from existing non-ICAT ion trap data from PeptideAtlas (Yeast build, 2006) were appended to this library, whereby only peptide ions not already present were added. Lastly, the latest NIST consensus library of yeast (ion trap) (http://www.peptideatlas.org/speclib/) is also appended in a similar manner. Lastly, all peptides were mapped to the SGD database of 6,607 yeast ORFs and unmapped sequences were discarded. The final statistics of the library are as follows: 153,180 spectra (of charge states ranging from +1 to +5) from 100,835 distinct peptide sequences. About one fifth of the spectra are from single observations and therefore not consensus spectra.

QQQ analysis of the peptide library

Peptide samples were analyzed on a hybrid triple quadrupole/ion trap mass spectrometer (4000QTRAP, AB/Sciex, Toronto) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source and coupled to a Tempo nano LC system (Applied Biosystems). Mass spectrometric and chromatographic operating conditions were as previously described[63]. The mass spectrometer was operated in selected reaction monitoring mode, triggering acquisition of a full MS/MS spectrum upon detection of an SRM trace. SRM acquisition was performed using ∼200 transitions per run and a dwell time of 10 ms/transition. For each peptide the first fragment ion of the y-series with m/z greater than [m/z precursor + 20 Th], for the doubly and triply charged peptide precursors, were used as triggering transitions. MS/MS spectra were acquired in enhanced product ion mode, using quadruple (q2) fragmentation, low Q1 resolution, scan speed 4000 amu/s and 2 scans summed. A second analysis was performed focused only on peptides that could not be detected in the first measurement. New mixes containing 50 peptides/run were prepared and the second fragment ion of the y-series with m/z greater than [m/z precursor + 20 Th] was used for the doubly and triply charged precursor as triggering transition.

Compilation of the SRM assay library

Raw MS data were converted to the mzXML[55] format by the tool msconvert, available within the TPP [56]. Spectra were assigned to peptide sequences in the same data analysis workflow as for the Orbitrap data described above. For this dataset, an iProphet probability cutoff was applied, such that the set of spectrum identifications retained had a decoy-estimated FDR of 0.00076. SpectraST[62] was used to compile these spectra into a spectral library, whereby replicates (spectra from the same peptide ions) were merged to form consensus spectra. No other quality filters were employed. Lastly, spectra from the original MRMAtlas[32] were appended to this library, whereby only peptide ions not already present were added. In total, the final library contained 43,728 spectra (84% of which consensus spectra of multiple observations) assigned to 28,216 distinct peptide sequences mapped to SGD proteins.

In selecting appropriate transitions from each library spectrum, fragments due to neutral loss from precursors were excluded. Fragments with m/z values close to the precursor ion m/z (| m/zQ1 - m/zQ3 | ≤ 5 Th) were discarded, as such transitions result in high noise levels. Collision energies associated to each transition were derived from the formulas: CE = 0.044 * m/z + 5.5 and CE = 0.051 * m/z + 0.5 (CE, collision energy, m/z, mass-to-charge ratio of the precursor ion) for doubly and triply charge precursor ions, respectively[15]. Additional features, such as fragment relative intensities and peptide elution times were extracted for each peptide from the corresponding MS/MS data.

Directed MS-sequencing of endogenous yeast peptides

S. cerevisiae cells (strain BY4741) were cultured and harvested at OD 2.0, as shown in ([16]). Proteins were extracted, digested, and the resulting peptide mixtures were desalted as in ([16]). Precursor ions associated to the five best peptides per protein (where available) represented in the ion trap spectral library were selected and distributed over 22 inclusion mass lists, each consisting of around 1,800 precursor masses, with no time scheduling. Three micrograms of total peptide mass was subjected to directed LC-MS analysis using an Easy-nLC/Orbitrap-Velos (both ThermoScientific, Bremen, Germany) LC-MS system. Peptides were separated using a linear gradient from 92% solvent A (98% water, 2% acetonitrile, 0.15% formic acid) and 8% solvent B (98% acetonitrile, 2% water, 0.15% formic acid) to 40% solvent B over 120 minutes. Directed LC-MS measurements of selected peptides were performed according to [29] using the same parameters as described above with the following modifications: the repeat count was set to 1 and each survey scan acquired in the Orbitrap was followed by MS-sequencing in the LIT the 10 most intense ions present in the inclusion mass list. A total of 119,792 PSMs (FDR = 0.1%), 17,135 distinct peptide ions and 2,509 distinct proteins (only unambiguously-mapped, non-decoy proteins counted, FDR = 1.2%) were identified by spectral searching (SpectraST, 3 Th precursor m/z tolerance, all default parameters) against our spectral library and processed by PeptideProphet. The identified peptide ion m/z values were then condensed into a single, time-scheduled inclusion mass list containing the precise elution times of each peptide and analyzed as recently described[29], with disabled mono-isotopic precursor selection. Here, a single directed 2hour LC-MS run produces around 5,500 MS and 34,000 MS/MS spectra. The MS/MS spectra are searched by the sequence search engine X!Tandem (K-score plugin) against the SGD database with the following parameters: 0.1 Da precursor mass tolerance allowing for isotope error, minimum of 1 tryptic termini, maximum of 2 missed trytpic cleavage, variable methionine oxidation and N-terminal acetylation, no refinement; and by the spectral search engine SpectraST against our IT spectral library with all default parameters. The search results are processed by PeptideProphet to generate the comparison plot of Figure 3c.

Prediction of transition specificity

Unique ion signatures were calculated as described in Roest et al. [37] with the following parameters: S. cerevisiae protein sequences were downloaded from ensembl.org, release 57_1j. We then generated theoretical precursor ions using trypsin for proteolysis (no missed cleavages), CAM as the only, and fixed, modification and charge states 2+ and 3+ for parent ions and considered up to 3 heavy isotopes (+0, …, +3 amu). For each of those precursor ions we generated the set of fragment ions (all b and y ions), giving rise to transition pairs. This dataset contained 192,792 peptides which resulted in 1,542,336 precursors and 74,611,328 transitions. We also prepared two reduced datasets that only contained the precursors of peptides that were observed in the yeast PeptideAtlas[31] (58,724 peptide entries from the yeast 2011 build) or the union of the yeast PA peptides and the theoretical tryptic peptides (223,120 peptide entries) which we then used as a background. Since the tryptic digest and the union of it with the PA data was visually very similar, only one of them is displayed in Fig. 3d. For each precursor in the SRMAtlas we then selected the best n ions (as determined experimentally on the QQQ instrument) where n is in the range of 1 to 7. We then selected all transitions of the background that were within a Q1 tolerance of ± 0.35 m/z and a Q3 tolerance of ± 0.35 m/z, as well as within a certain tolerance in retention time (± 5 arbitrary units in the simulation where retention time information was included; this corresponds roughly to ± 2.5 min on a 30 min gradient). To predict retention times, the SSRCalc tool was used[64]. The minimal number of transitions necessary to uniquely identify a precursor species, trprec, min was defined as the minimal n for which no other precursor existed in the background whose challenge ions contained all n query ions. This number was recorded for each precursor.

Yeast strains and media used for QTL analysis

The strain collection derived from a cross between the two parental strains BY4716, an S288C derivative (MATα lys2Δ0), and RM11-1a (MATa, leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 ho∷KAN), as described in [41]. Strains were pre-cultured in standard YPD medium at 30°C for 24 hours and then cells were transferred to complete synthetic medium (CSM), (inoculation OD, 0.05) and cultured at 30C under agitation until OD 0.8 (+/- 0.05). In order to limit the noise due to the culture conditions, all media were prepared in a single batch in large quantity, and all cultures were conducted by the same experimentalist using the same incubator. Cells were harvested and lysed as described in [65].

LC/MS analyses of the yeast strain collection

Protein digestion and sample preparation for MS analysis was as described in [16]. In the discovery experiment, peptides were analyzed on an Orbitrap Velos MS, using the reduced, rolling inclusion mass list and setup described above with a few modifications. Here, the survey MS-scan was acquired at 60,000 FWHM resolution settings followed by MS-sequencing in the LIT of 10 precursors being part of the inclusion mass list and the 10 most abundant precursors within the same cycle (Top20 method). Additionally, the FT master scan preview mode and non-peptide monoisotopic recognition options were enabled. Data were analyzed as above using the combined sequence database and spectral search against the LIT library (protein FDR < 1%). Relative protein quantitation across the sample set was achieved by a label-free quantification approach using the Progenesis LC-MS software (Nonlinear Dynamics Limited, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) as described previously [66].

In the targeted SRM-based analysis of the 48-protein set, 100 μg-aliquots of each protein extract was mixed prior to trypsinization to an equal amount of yeast proteins extracted in the same way from 15N-completely labeled yeast cells, prepared as described in [16]. Protein digestion and sample preparation for MS analysis was as described in [16]. Peptide samples were analyzed on a 5500QTrap MS (ABSciex, Toronto) equipped with a chromatographic and source setup described in [67]. 3 μg of peptides were separated with a linear gradient of acetonitrile/water, containing 0.1% formic acid, from 5 to 35% acetonitrile in 30 minutes, at a flow rate of 350 nl/min. The mass spectrometer was operated in scheduled multiple reaction monitoring mode, with unit resolution for Q1 and Q3 (0.7 m/z half maximum peak width). SRM coordinates for the set of 48 target proteins were extracted from the QQQ library and retention times were realigned to match the chromatographic setup used. For each protein up to three peptides and four transitions, in the heavy and light channels were measured, for a total of 580 transitions. 22 transitions pertaining to a set of calibration peptides for realigning retention times between runs and decoy transitions (12 per MS-run) were added to the scheduled SRM method, consisting of total 614 transitions, measured with a target scan time of 2.5 s, and a retention time window of 4 minutes. Raw data were processed using mQuest and mProphet[50]. In order to recover low intensity protein signals and avoid missing values in the data matrix we processed the data in profiles. A profile is comprised of the peptide expressions measured across all the yeast strains. We determined the highest quality data point in a profile using the mProphet Q-value and determined its corresponding accurate normalized retention time (iRT)[68] using the set of standard peptides for retention time realignment. If a Q-value was above 0.05 we chose the data point with the smallest retention time deviation as relative to the iRT. For 64 peptide measurements the integration boundary was changed using this procedure.

Genotyping of the strain library

The yeast strain library has previously been genotyped at 3,312 markers[41]. However, technical limitations led to more than 4% missing values. We inferred missing genotypes by using the information available for flanking markers and recombination rates. Given a non-genotyped marker we first assessed its flanking markers. When the genotype of the flanking markers were the same and if the recombination rate between those markers was smaller than 0.1, we assumed that no recombination event took place and the same genotype as the flanking one was assigned to the missing value. When the genotype of flanking markers differed, we used the recombination rates to estimate the probability P(gn = gn−1) of the missing genotype to be the same as the one of the leading flanking marker.

Where rn−1→n is the recombination rate between the maker n-1 and n, and rn→n+1 the recombination rate between the maker n and n+1.

The genotype at position n, gn, was then inferred in a conservative manner:

Evaluation of the variability of the protein abundances in the discovery study

Peptide-level raw intensities are available as Supplementary Dataset. We used the sum of all the peptide intensities measured in one sample to scale the measurements. Before summarizing the peptide -level data at the protein level, we filtered out the peptides with sequence variations between the RM and BY strains. Genome sequence information for the RM11-1a strain was downloaded from the Broad Institute Fungal Genome Initiative (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/saccharomyces_cerevisiae.3/Info.html). We searched for homology between the sequences of the quantified peptides and the translations of all the transcripts predicted from the assembly of the RM11-1a genome. The 622 peptides (6.2%) for which we did not find perfect matches, as well as 1,794 peptides (14.9%) for which the measurements were not complete, were eliminated from the subsequent analyses. The average of the normalized peptide intensities was used to estimate the protein expression levels of 2,088 proteins in each strain. The variability of the protein levels across the strains was scored using the median absolute deviation (MAD). We noticed that it was biased against the number of peptides that were measured per protein (Supplementary Fig. 11a). To correct for this bias, the residuals of the linear regression of the log-transformed MAD against the log-transformed peptides counts were used as the variability score (Supplementary Figure 11b). Additionally, proteins measured through less than three peptides were discarded.

Functional enrichments analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using topGO, which takes the topology of the ontology into account[69].

Metabolic pathway enrichment

The curated protein-pathway relationships for 171 metabolic pathways were retrieved from the SGD database (http://www.yeastgenome.org/download-data/curation). We tested for enrichments in pathways among the 150 most variable proteins by comparing the number of variable proteins in each pathway to empirical null distributions obtained by picking randomly (100,000 times) 150 proteins among the 2,088 proteins that were included in the discovery study.

Complex/network modules enrichment

Protein complexes in yeast have previously been identified through an unsupervised integration of several tandem affinity purification datasets[70]. In a first step, only the most confident complexes were taken into account (BT409 dataset). Similarly to the metabolic pathway enrichments, tests were based on 100,000 permutations of the data. In a second step, the enriched protein complexes were extended to also include interacting proteins (protein module). The yeast protein interaction network was retrieved from BioGRID[71]. For each significantly enriched protein complex, the proteins that were interacting with all the proteins of the initial complex were considered as member of the final module.

Selection of proteins targeted for QTL

The proteins were selected for the pQTL study based either on their high abundance variability measured in the preliminary discovery study, or based on biological properties. We performed functional and network enrichment analysis on the 150 proteins showing the highest variability in protein abundance and selected all components of the most significantly enriched categories for the subsequent pQTL study. We therefore included 27 proteins belonging to i) the GO term ‘NADH oxidation’, ii) the metabolic pathway ‘Arginine metabolism’, and iii) a highly connected protein sub-network that we named B1B2 (a protein module involved in branched chain amino-acid metabolism). Note that some proteins belonging to these categories were selected even though their abundance was not particularly variable and in one case (Arg3p) the protein was not even detected in the screening phase. The ability to reliably measure even those proteins with SRM demonstrates the utility of a genome-wide peptide map. Finally, the pathway- and network-based list of target proteins was complemented with the 21 most variable proteins that were not already included based on the previous criteria (Supplementary Table 4).

Normalization and summarization of the SRM pQTL data

The abundance of 48 proteins were evaluated through the measurements of 98 transitions groups (peptides) in 91 samples. Nine samples (corresponding to strains 15.6.c, 7.2.c, 9.2.d, 7.8.d, 14.6.d, 5.3.d_B1, 19.1.c, 7.5.d and RM_B4) were removed from subsequent analysis due to their low quality. Two proteins were measured through three transition groups, 33 proteins through two groups, and 14 through one group. Values of different transition groups for the same protein were summarized after appropriate normalization. However, the transition groups of 4 out of the 35 proteins covered by more than one transition group were uncorrelated. This problem is often observed in proteomic studies and might be due to different post-translational modifications of the peptides. Therefore, we decided not to summarize inconsistent transition groups and instead considered each group as an independent trait for the pQTL mapping. To summarize peptide levels of consistent transition groups into protein abundances, we developed a weighted normalization strategy that takes into account the confidence in the measurements of individual peptides (mProphet score). The normalization and summarization procedures are detailed below and its application to one of the studied proteins is depicted in the Supplementary Fig. 19.

In the case of proteins with only one matching transition group we quantified the respective protein using those peptide-level data if the mProphet score was below 0.05. Otherwise the datapoint was treated as a missing value.

Most proteins (33) had values for at least two peptides (transition groups). In this case we first tested if peptides assigned to the same protein gave consistent results across the measured strains. In order to integrate the peptide-level data, we first centered the signals of each peptide using the median value across all samples. Then we computed the Spearman rank correlation between paired peptides. If the correlation was better than 0.3 peptide data were integrated (see below). Otherwise each peptide was treated as a separate trait for the QTL mapping.

When the peptides were consistent, we computed for each peptide a robust mean ( for the first peptide of the protein p and for the other peptide) by taking only into account the values for which the absolute difference between the two peptides did not exceed the mean plus one standard deviation of all the absolute inter-peptide difference (noted Δmax).

where N is the number of samples and P the number of proteins for which the Spearman correlation between the two peptides is greater than 0.3.

The same idea is applied to compute robust standard deviations:

The robust means and standard deviations are then used to normalize the peptide measurements by centering and scaling them:

For the two proteins for which three transitions groups were measured, we compared median centered peptide abundances. For one protein (Hxk1p), the measurement of one peptide was not comparable to the two others (Spearman's correlation < 0.3). We discarded the transition group from the subsequent analysis and treated the two remaining ones as described above. The transition group values of the other protein (Msc1p) were comparable (average Spearman's correlation 0.85). Data were summarized as described below without further normalization.

The summarization procedure that we have implemented is conservative and takes into account the confidence in the measurements (mProphet score). For each protein p, measured in the sample n, we have i measured peptides (transition groups). The abundance ynp of the protein is estimated by computing the mean of the normalized peptide measurements xnp weighted by the inverse of the mProphet confidence score . Additionally, we considered protein levels as unknown when at the same time i) none of the transition groups had a mProphet score < 10−5 and ii) measurements did not agree; i.e. when the difference between the measurements was larger than two times the median absolute deviation of the measurements.

QTL detection

QTLs were mapped using a Random Forest-based method that we previously developed[44]. Forests of 10,000 decision trees were learned to score the QTLs based on selection frequency. To estimate the significance of the linkages, each protein abundance vector was permuted 25,000 times (by shuffling abundances between strains) and null distributions of the selection frequencies were generated for each trait and each marker. The same permutation scheme has been used for all traits in order to take into account for potential inter-trait correlations that might artificially inflate (or deflate) Random Forest selection frequencies. The permutations were also used to estimate empirical False Discovery Rates (FDR).

Random Forest split asymmetry epistasis detection method

Epistatic interactions between markers were extracted from the structure of a regression trees in Random Forest (RF)[72] by looking for a phenomenon that we call split asymmetry (Supplementary Fig. 13 and 14). Consider a sequence of two decision splits in a tree, involving two variables, first XA and then XB. This sequence may occur anywhere in the tree – near the root, leaves or somewhere in the middle – and its location may vary from tree to tree. After splitting on XB, there will be some difference in means between the values on its left and right daughter nodes. We can view this difference between means as a slope. If the mean of the right daughter is greater than that of the left daughter, the slope is positive, and in the opposite case the slope is negative. If there is no dependency between XA and XB when considering the response values, we would expect that the slope after splitting on XB would be the same regardless of whether XB splits on data in the left or right daughter node of the XA split. On the other hand, if there is a dependency between XA and XB, we expect that the decision at XA will influence the outcome of the split at XBl thus resulting in different slopes for XBl (split on left daughter of XA) vs. XBr (split on right daughter of XA). Given this context, we say that a split is asymmetric in a sequence of variables with dependencies, and a split is symmetric in a sequence of variables with no dependencies.

All such slopes involving all two-variable decision sequences encountered in the forest are summed according to their “sidedness”, leading to two square matrices: Ml for the sequence corresponding to XA → XBl, the “left” matrix, and Mr for the sequence corresponding to XA → XBr, the “right” matrix (Supplementary Fig 14). In both matrices, the row indicates the first variable in the decision sequence, and the column indicates the second variable in the sequence.

In case of extreme dependencies, XBr (for example) might be used frequently, yet XBl might never be suitable as a splitting variable, and therefore might not occur at all in the forest (leading to an entry of 0 in Ml). It should also be noted that the individual slopes will be influenced by the stochastic characteristics of RF – in particular by the bootstrap sample of data used to fit the tree in question. However, the aggregated slope for a variable pair will be more robust. In any case, the magnitude of the absolute difference of the aggregated slopes (a matrix D) is an indicator of the strength of the dependency between the involved splitting variables. Note that while |M| traditionally denotes the determinant of M when M is a matrix, for convenience we use it here to mean the matrix resulting from taking the absolute values of the entries in M.

We introduce a few modifications to D to further refine the score it represents. First, we subtract as a penalty the mean absolute slope, here the matrix S:

We additionally constrain negative values to be zero, so that only pairs whose difference in slope exceeds the average magnitude are considered.

Finally, we take the minimum of the corresponding values D″ij and D″ji, since purely interacting variables (i.e. without an additive effect), will be “order-agnostic”, meaning that the sequences XA → X2 and XB → X1 should both be asymmetric; we take the minimum of the two scenarios to be conservative. In practice, this has reduced the number of false positives encountered. This final epistasis score is stored in a (symmetric) matrix E:

The evaluation of the performance of the method is described in the Supplementary Discussion.

Radom Forests were grown using 500,000 trees. This large forest size ensures high reproducibility of the interaction scores (Supplementary Fig. 18a-d). Null distributions of the epistasis scores were obtained by permuting each trait 150 times. The same permutation scheme was used for all the traits in order to take potential inter-trait correlations into account. We noticed that the null distributions were trait- and marker pair- dependent. To remove these biases, gene specific null distributions as well as the real epistasis score grouped by traits were normalized by subtracting the median of the distribution. These trait-wise normalized scores were then subjected to a marker-pair-wise normalization following the same procedure. The normalized null distributions were then pooled and used to compute the P-values and false discovery rates of the epistatic pQTL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in part by ETH Zurich, the Swiss National Science Foundation (3100A0-107679), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract No. N01-HV-28179, the National Science Foundation MRI (grant 0923536), the Luxembourg Centre for Systems Biomedicine and the University of Luxembourg, and by SystemsX.ch the Swiss initiative for systems biology. P.P. is supported by a ‘Foerderungsprofessur’ grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant PP00P3_133670), by an EU Seventh Framework Program Reintegration grant (FP7-PEOPLE-2010-RG-277147) and by a Promedica Stiftung (grant 2-70669-11), H. L. is supported by the University Grant Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government, China (grant no. HKUST DAG08/09.EG02). A.B. is supported by the Klaus Tschira Foundation and by a EU FP7 HEALTH grant (HEALTH-F4-2008-223539). R.A. is supported by the European Research Council (grant #ERC-2008-AdG 233226) and by SystemsX.ch, the Swiss Initiative for Systems Biology.

References

- 1.Fleischmann RD, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269(5223):496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venter JC, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291(5507):1304–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlen M, Graslund S, Sundstrom M. A pilot project to generate affinity reagents to human proteins. Nat Methods. 2008;5(10):854–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1008-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taussig MJ, et al. ProteomeBinders: planning a European resource of affinity reagents for analysis of the human proteome. Nat Methods. 2007;4(1):13–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0107-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berglund L, et al. A genecentric Human Protein Atlas for expression profiles based on antibodies. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7(10):2019–27. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R800013-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425(6959):737–41. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature. 2003;422(6928):198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsch EW, Lam H, Aebersold R. PeptideAtlas: a resource for target selection for emerging targeted proteomics workflows. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(5):429–34. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Godoy LM, et al. Comprehensive mass-spectrometry-based proteome quantification of haploid versus diploid yeast. Nature. 2008;455(7217):1251–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam H, Aebersold R. Spectral library searching for peptide identification via tandem MS. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;604:95–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-444-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam H, et al. Building consensus spectral libraries for peptide identification in proteomics. Nat Methods. 2008;5(10):873–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frewen BE, et al. Analysis of peptide MS/MS spectra from large-scale proteomics experiments using spectrum libraries. Anal Chem. 2006;78(16):5678–84. doi: 10.1021/ac060279n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig R, et al. Using annotated peptide mass spectrum libraries for protein identification. J Proteome Res. 2006;5(8):1843–9. doi: 10.1021/pr0602085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson L, Hunter CL. Quantitative mass spectrometric multiple reaction monitoring assays for major plasma proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(4):573–88. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500331-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lange V, et al. Selected reaction monitoring for quantitative proteomics: a tutorial. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:222. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Picotti P, et al. Full dynamic range proteome analysis of S. cerevisiae by targeted proteomics. Cell. 2009;138(4):795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deutsch EW. The PeptideAtlas Project. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;604:285–96. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-444-9_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange V, et al. Targeted quantitative analysis of Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors by multiple reaction monitoring. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7(8):1489–500. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800032-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahrens CH, et al. Generating and navigating proteome maps using mass spectrometry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(11):789–801. doi: 10.1038/nrm2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foss EJ, et al. Genetic basis of proteome variation in yeast. Nat Genet. 2007;39(11):1369–75. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domon B, Aebersold R. Options and considerations when selecting a quantitative proteomics strategy. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):710–21. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desiere F, et al. The PeptideAtlas project. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D655–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuster B, et al. Scoring proteomes with proteotypic peptide probes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(7):577–83. doi: 10.1038/nrm1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallick P, et al. Computational prediction of proteotypic peptides for quantitative proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(1):125–31. doi: 10.1038/nbt1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horth P, et al. Efficient fractionation and improved protein identification by peptide OFFGEL electrophoresis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(10):1968–74. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600037-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heller M, et al. Two-stage Off-Gel isoelectric focusing: protein followed by peptide fractionation and application to proteome analysis of human plasma. Electrophoresis. 2005;26(6):1174–88. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank R. The SPOT-synthesis technique. Synthetic peptide arrays on membrane supports--principles and applications. J Immunol Methods. 2002;267(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Picotti P, Aebersold R, Domon B. The implications of proteolytic background for shotgun proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(9):1589–98. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700029-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt A, et al. An integrated, directed mass spectrometric approach for in-depth characterization of complex peptide mixtures. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7(11):2138–50. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700498-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller A, Shteynberg D. Software Pipeline and Data Analysis for MS/MS Proteomics: The Trans-Proteomic Pipeline. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;694:169–89. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-977-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King NL, et al. Analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteome with PeptideAtlas. Genome Biol. 2006;7(11):R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-11-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picotti P, et al. A database of mass spectrometric assays for the yeast proteome. Nat Methods. 2008;5(11):913–4. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1108-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krokhin OV. Sequence-specific retention calculator. Algorithm for peptide retention prediction in ion-pair RP-HPLC: application to 300- and 100-A pore size C18 sorbents. Anal Chem. 2006;78(22):7785–95. doi: 10.1021/ac060777w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrah T, Deutsch EW, Aebersold R. Using the Human Plasma PeptideAtlas for studying human plasma proteins. Meth Molec Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-068-3_23. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Killcoyne S, et al. Interfaces to PeptideAtlas: a case study of standard data access systems. submitted to BMC Bioinformatics. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbr067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craig R, Beavis RC. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1466–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]