Abstract

Tissue injury initiates an inflammatory response through the actions of immunostimulatory molecules referred to as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). DAMPs encompass a group of heterogenous molecules, including intracellular molecules released during cell necrosis and molecules involved in extracellular matrix remodeling such as hyaluronan, biglycan, and fibronectin. Kidney-specific DAMPs include crystals and uromodulin released by renal tubular damage. DAMPs trigger innate immunity by activating Toll-like receptors, purinergic receptors, or the NLRP3 inflammasome. However, recent evidence revealed that DAMPs also trigger re-epithelialization upon kidney injury and contribute to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and, potentially, to myofibroblast differentiation and proliferation. Thus, these discoveries suggest that DAMPs drive not only immune injury but also kidney regeneration and renal scarring. Here, we review the data from these studies and discuss the increasingly complex connection between DAMPs and kidney diseases.

Keywords: immunology and pathology, ARF, GN

Toxins, ischemia, and trauma trigger inflammation just like pathogens, but why? Inflammation was first defined by rubor, calor, dolor, tumor, and function laesa, which all represent responses of the body to injury.1 The discovery of pathogenic bacteria as a cause of inflammation 150 years ago led to the assumption that pathogens trigger most forms of inflammation. The fields of immunology and microbiology evolved and generated the popular concept that the immune system developed from the everlasting competition between host and pathogens, with inflammation being the battlefield.2 However, this concept did not cover numerous clinical observations, including toxin-, ischemia-, or trauma-related inflammation as well as autoimmune or autoinflammatory disorders.3 Nephrologists should have been at the forefront of this debate because sterile inflammation drives the majority of kidney disorders.4–6 But how do sterile injuries trigger kidney inflammation?

The last decade revealed that injured cells release intracellular molecules that activate innate immunity just like pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).7 Accordingly, such molecules were named damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). PAMPs and DAMPs activate identical pattern recognition receptors including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and inflammasomes, a process that induces kidney inflammation and immunopathology.8–11 This review provides an update on the different modes of DAMP generation and how this contributes to tissue remodeling in kidney disease.

DAMP Generation inside the Kidney

DAMP Release from Dying Cells

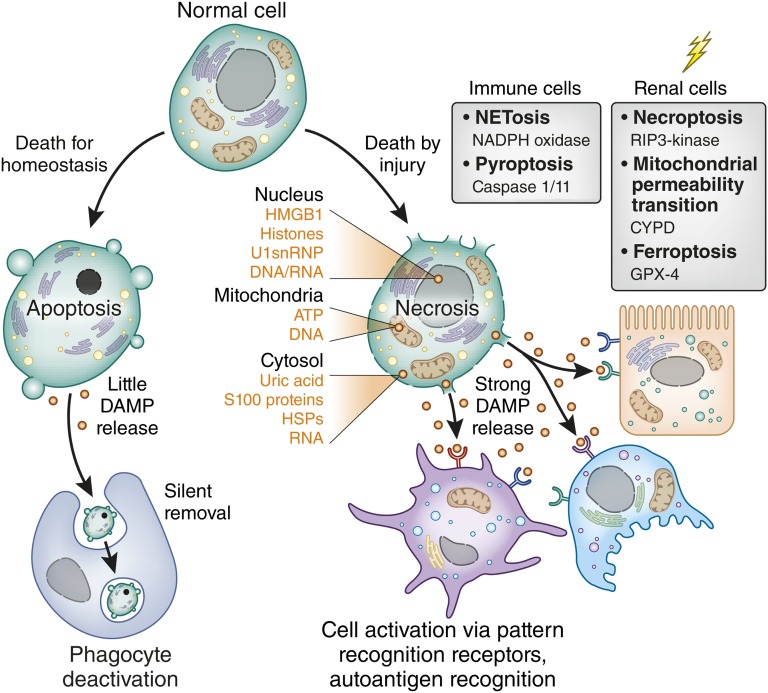

Cell death may or may not activate immunity.12 Apoptosis is a silent cell death because apoptosis maintains membrane integrity and DAMP release (Figure 1). Apoptosis is important for homeostatic cell clearance (e.g., of autoreactive lymphocytes during negative selection in the thymus or of senescent blood cells).12 Apoptosis involves a complex series of signaling events to induce surface expression of find-me and eat-me signals that foster phagocytic clearance.13 Uptake of apoptotic cells settles the phagocyte’s host defense modus and rather induces an anti-inflammatory phenotype, which enforces homeostasis.14,15 It has long been thought that tissue injury also involves apoptotic cell death, often based on terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling positivity, but this also identifies DNA breaks during cell necrosis or DNA repair.16 In fact, it has now become evident that injury-induced cell death mostly involves regulated necrosis (Figure 1).17 For example, necroptosis is a receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase RIP1/RIP3–mediated form of necrosis that is triggered by genotoxic stress as well as by ligands to TLR3/TLR4 and surface receptors of the TNF receptor superfamily.18 Necroptosis was documented to contribute to acute tubular necrosis in several AKI models.19–23 Cyclophilin D–mediated disruption of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential is another form of regulated necrosis involved in postischemic AKI.20 Remarkably, mice lacking both RIP3 and cyclophilin D no longer develop AKI, even upon extended times of renal ischemia.20 Ferroptosis is a glutathione peroxidase 4–mediated form of regulated necrosis specifically triggered by oxidative stress.24 Some types of regulated necrosis seem restricted to immune cells such as NETosis, a controlled explosion of activated neutrophils. NETosis supports bacterial entrapment and killing during host defense.25 NETosis has not yet been demonstrated in infective pyelonephritis but occurs in renal vasculitis with crescentic GN.26 Pyroptosis is a caspase-1– dependent and caspase-11–dependent necrosis of infected macrophages.27,28 Currently, no functional in vivo data document pyroptosis contributing to kidney inflammation.29,30 All of these forms of necrosis have the potential to release DAMPs from different intracellular compartments into the extracellular space (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.

The type of cell death defines DAMP release. Most cells of the body undergo periodic replacement by renewal just like the blood cells. In addition, lymphocyte maturation involves induced cell death to sort out cells with autoreactivity. All such cells undergo apoptosis, a programmed form of cell death that maintains inner and outer membranes to avoid DAMP release. By contrast, cell death induced by injury leads to necrosis. Because of the numerous types of injury (genotoxic stress, toxins, cytokines, oxidative stress), several pathways exist to induce programmed necrosis. Some seem to occur only in specific cell types such as neutrophils (N) or macrophages (MØ). The graph lists essential signaling molecules that trigger this form of cell death. Necrosis implies the disruption of inner and outer membranes, which leads to the release of intracellular DAMPs from various compartments as listed on the right. U1snRNP, U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein; NADPH, NAD phosphate dehydrogenase; CYPD, cyclophilin D, GPX-4, glutathione peroxidase 4; HSP, heat shock protein.

Table 1.

DAMP effects in kidney disease (models) (receptor studies not included)

| DAMP | Kidney Disease | Receptor and Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracellular DAMPs | |||

| Nucleus | |||

| HMGB1 | Sepsis, AKI | TLR2/TLR4-induced inflammation | 142–145 |

| Histones | Sepsis, AKI | TLR2/TLR4-induced inflammation | 89,100 |

| DNA/RNA/U1snRNP | IC-GN, inflammation in HD | TLR3-induced mesangial cell activation TLR3/TLR7/TLR9 DC and B cell activation | 156,157,169,170,172–177 |

| Mitochondrial | |||

| DNA | — | TLR9 | 178 |

| ATP | Fibrosis, hypertension, metabolic syndrome | P2X7-mediated renal inflammation | 95,179–181 |

| Cytosol | |||

| Uric acid | DN | NLRP3 | 82,182 |

| S100A, S100B | DN | RAGE-induced inflammation | 183 |

| Heat shock proteins | — | TLR2/TLR4-induced inflammation | 184 |

| Extracellular DAMPs | |||

| Biglycan | Renal fibrosis, lupus nephritis, DN, GN | NLRP3-, P2 X7-induced inflammation, | 38,42,95,165 |

| DC/macrophage activation via TLR2/TLR4 | 185,186 | ||

| Sepsis | TLR2/TLR4, NLRP3-, P2X7 | 90,185,187 | |

| Decorin | Sepsis | TLR2/TLR4 | 78 |

| Fibrinogen | FSGS, MPGN | Podocyte activation via TLR2/TLR4 | 90,187,188 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | Fibroblast activation via TLR2TLR4 | ||

| Fibronectin | — | TLR4 | 189 |

| Hyaluronan | — | TLR2/TLR4-induced inflammation, not confirmed in mesangial cells | 124,189–191 |

| AKI, lupus nephritis | TLR4/CD44 | 6,163,192 | |

| DN | — | 163 | |

| Heparan sulfate | DN, CKD | TLR4-induced DC maturation | 62, 193,194 |

| Versican | CKD | TLR2 | 195,196 |

| Amyloid-β | — | NLRP3-activation in DCs/macrophages | 197 |

| HDL | CVD in uremia in absence of uremia | Endothelial dysfunction and inflammation via TLR2 | 198–200 |

| Crystals | Oxalate nephropathy | NLRP3-activation in renal DC | 84,97,171 |

| Adenine nephropathy | TLR2/4-NLRP3 activation | ||

| Kidney-specific DAMPs | |||

| Uromodulin | AKI | ?, cytokine+DAMPs clearance from kidney? | 80,81,201 |

| ? | TLR4 and NLRP3-induced inflammation |

IRI, ischemia-reperfusion injury; IC-GN, immune complex GN; HD, hemodialysis; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products; MPGN, membranoproliferative GN; EDA, extra domain A; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

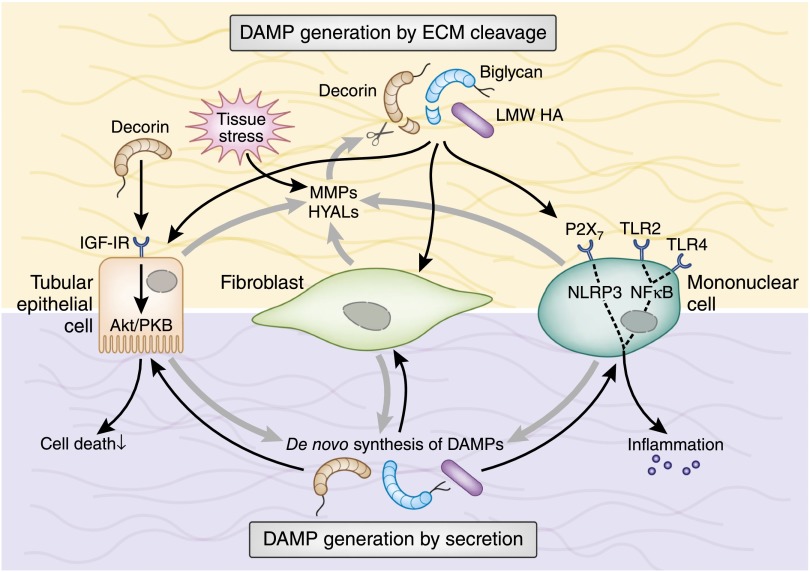

DAMP Generation during Extracellular Matrix Remodeling

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is another source of DAMPs.31 The renal ECM consists of collagens and elastic fibers, proteoglycans, hyaluronan (HA), and assorted glycoproteins, which undergo a constant turnover.31–36 Enzymatic degradation can turn immunologically quiescent ECM components into fragments that ligate TLRs, purinergic receptors, inflammasomes, or integrins of infiltrating and resident renal cells (Table 1).33,37–45 As a second mechanism, macrophages and renal resident cells stimulated by TGF-β46–50 and proinflammatory cytokines42,51 de novo synthesize soluble DAMPs38,42,52 (Figure 2). For example, HA exists under physiologic conditions as a polymer with a high molecular mass of ≥106 Da. HA accumulates in kidneys during AKI,53,54 allograft rejection,54,55 interstitial nephritis,54,56 and lupus nephritis.54,57 During inflammation and fibrosis, HA is depolymerized by hyaluronidases, which generates low molecular weight fragments that interact with TLRs and the NLR family, pyrin domain–containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome (Figure 2, Table 1).33–35 Inflammation also breaks down the glycosaminoglycan heparan sulfate (HS).58 Heparanase-mediated HS degradation is a key process in diabetic nephropathy59–61 and CKD62 (Table 1). However, the majority of extracellular DAMPs63–67 are released by matrix metalloproteinases.40,68–72 Among those, the TGF-β–binding small leucine-rich proteoglycans biglycan and decorin, in their soluble form, can promote sterile as well as pathogen-induced inflammation.33,37,40,73 Numerous inflammatory and fibrotic kidney disorders are associated with decorin and biglycan induction.33,37,38,40,57,74,75. Transient overexpression of soluble biglycan in mice demonstrates that biglycan triggers inflammation in healthy kidneys and potentiates renal inflammation and fibrosis (Table 1).38,74–76 Finally, there is overwhelming evidence for an antifibrotic activity of soluble decorin directly interacting with another crucial members of the TGF-β superfamily, such as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), and inhibiting apoptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) via the IGF type I receptor/Akt-signaling pathway (Figure 2).33,48,49,73,77,78

Figure 2.

ECM-related DAMPs are secreted or originate from ECM cleavage. Under tissue stress or injury, resident cells (e.g., TECs and fibroblasts) release MMPs and HYALs to cleave ECM components. Soluble biglycan and decorin and low molecular weight HA act as extracellular DAMPs by interacting with TLR2/TLR4 on the surface of infiltrating mononuclear and resident renal cells. In mononuclear cells, this leads to the activation of NF-κB and production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that, in turn, recruit additional mononuclear cells to the side of injury. Moreover, soluble biglycan and low molecular weight HA activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Proinflammatory cytokines stimulate mononuclear and renal resident cells to de novo produce DAMPs, thereby creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies the inflammatory response. Besides acting as a DAMP, decorin signals via IGF-IR/Akt in TECs and protects them from apoptosis. LMW, low molecular weight; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; HYAL, hyaluronidase; IGF-IR, IGF type 1 receptor; PKB, protein kinase B.

Kidney-Specific Modes of DAMP Generation

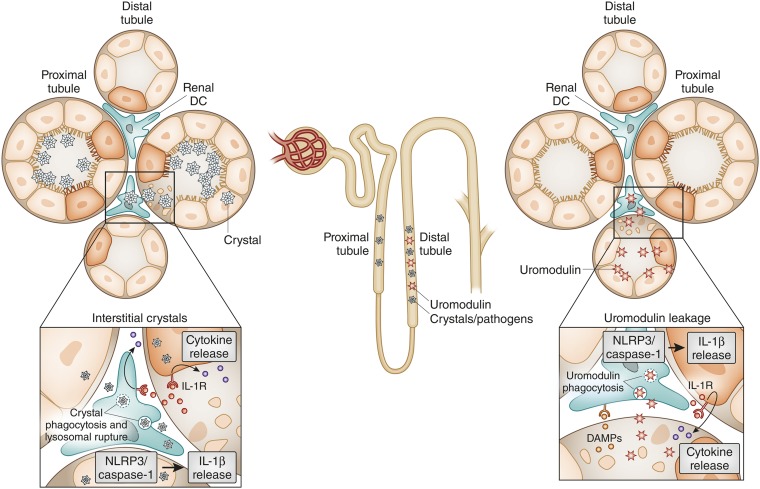

Tamm–Horsfall protein (renamed uromodulin) is an adhesive, particle-forming protein that is exclusively secreted at the thick ascending limb of the distal tubule. Its adhesive nature coats all particles in the distal tubule such as cells (forming cellular casts) and cell debris (granular casts), crystals (supporting crystal aggregation), bacteria (supporting their clearance), and even serves as a sink for inflammatory cytokines, albumin, and so forth.79 Uromodulin is immunologically inert inside the tubular lumen. Tubular injury, however, allows uromodulin leakage into the interstitial compartment where it turns into a DAMP that activates interstitial dendritic cells via TLR4.80 The particle nature of uromodulin fosters phagocytosis and endosomal destabilization in dendritic cells, a process that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome resulting in the release of IL-1β.81 This mechanism is another avenue for activating innate immunity in tubular injury (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Crystals and uromodulin act as DAMPs to induce renal inflammation. Crystals precipitate in the proximal tubule, the distal tubule, and/or in the interstitial compartment of the kidney. Crystals kill TECs. In addition, crystals can be taken up by interstitial dendritic cells via phagocytosis. Lysosomal leakage and potassium efflux (not shown) provide a signal to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, which cleaves caspase-1 and subsequently pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 (not shown). IL-1β ligates the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) on renal parenchymal cells as well as immune cells, which triggers NF-κB–dependent cytokine and chemokine release. In distal tubule injury, uromodulin leakage into the interstitial compartment activates dendritic cells via TLR4 and the NLRP3 inflammasome. As uromodulin also binds to crystals, crystal precipitation in the distal tubule is likely to involve both mechanisms.

The kidney is a preferred site of particle formation (e.g., from anorganic mineral-related crystals or proteins aggregates such as myoglobin and light chains). Crystals or crystalline proteins act as DAMPs by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells and macrophages.82 In the distal tubule, uromodulin coats crystals and can trigger immune activation via the aforementioned mechanism.83 Some disorders, including oxalosis, involve diffuse crystallization in the renal interstitium, in which dendritic cells pick up crystals into lysosomal compartments and again activate the NLRP3 inflammasome (Figure 3).84 The same mechanism is likely to also contribute to renal inflammation and tubular injury in tumor lysis syndrome and other crystalline nephropathies.83

DAMP Effects on Kidney Injury and Repair

DAMPs Activate Systemic Alloimmunity and Autoimmunity

Circulating DAMPs activate pattern recognition receptors on immune cells in the circulation or in lymphoid organs.2,7 By activating these receptors, DAMPs mimic PAMPs and convert tolerogenic immune responses into immunogenic immune responses. In particular, the activation of antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells and B cells enhances antigen presentation, expansion of antigen-specific lymphocyte subsets, and antibody production.2,7 This process plays an important role in kidney diseases involving alloimmunity and autoimmunity such as kidney transplantation, immune complex GN, or ANCA vasculitis.8,85–87

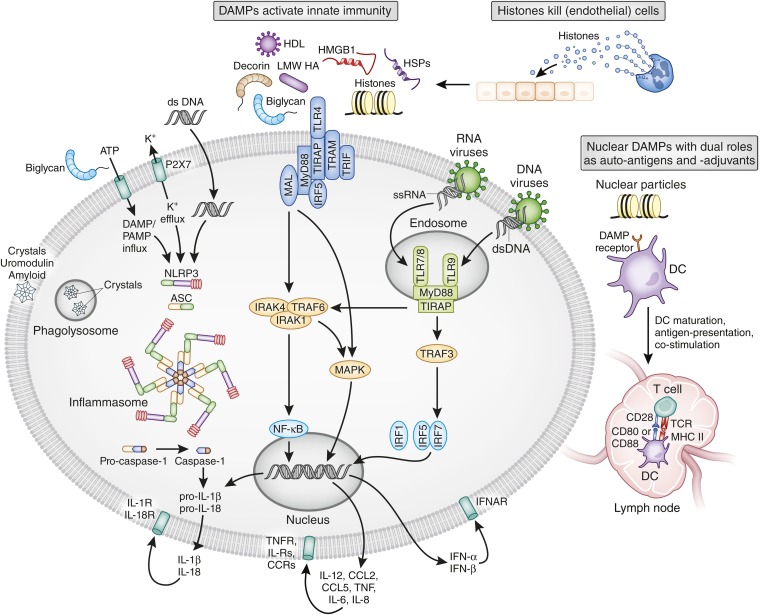

How DAMPs Activate the Kidney’s Innate Immune System

Immunostimulatory “Autoadjuvant” Effects

DAMPs activate TLRs on renal parenchymal cells as well as on resident and infiltrating immune cells (for a review of the involved signaling pathways, see refs.11,88). TLR-mediated cell activation involves the induction of NF-κB–dependent inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in all cells (Figures 4 and 5). Additional cell type–specific effects include the upregulation of adhesion molecules, increased vascular permeability in renal endothelial cells, and filtration barrier dysfunction in podocytes.89–93 Resident and infiltrating mononuclear phagocytes also host the NLRP3 inflammasome that integrates DAMP signals such as ATP, histones, HA, biglycan, crystals, or uromodulin into the activation of caspase-1.81,94–97 Caspase-1 and caspase-11 confer proteolytic cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into the mature cytokines, which are then secreted and trigger local inflammation inside the kidney (reviewed in ref.10).

Figure 4.

DAMP effects in immunopathology. DAMPs activate several classes of pattern recognition receptors, which all induce an immediate activation of innate immunity (i.e., systemic and tissue inflammation). Most DAMPs activate TLR2 and TLR4 at the cell surface. In particular, particles enter the cells via phagocytosis and trigger assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nucleic acid–related DAMPs activate TLR7 and TLR9 in intracellular endosomes. All pattern recognition receptors finally drive the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines that then activate cytokine receptors on the same cell or on other cells. Extracellular histones also directly kill (endothelial) cells. The molecular mechanism of this process is poorly defined but may involve surface charge. Certain nuclear DAMPs also act as autoantigens in systemic lupus and contribute to lupus nephritis. Their adjuvant-like ability to also activate antigen-presenting cells via TLR7 and TLR9 strongly promotes autoimmunization and the expansion of autoreactive lymphocytes. Local release within the kidney also promotes intrarenal autoantigen recognition (e.g., by circulating autoantibodies and subsequent immune complex GN; not shown). LMW, low molecular weight; HSP, heat shock protein; MAL, MyD88 adaptor–like; IRF, IFN regulatory factor; TRAP, TNF receptor–associated protein; TRAF, TNF receptor–associated factor; TRIF, TIR domain–containing adapter inducing IFN-β; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA; dsDNA, double-stranded RNA; DC, dendritic cell;ASC, apoptotic speck protein; IRAK, IL-1 receptor–associated kinase; TIRAP, Toll IL-1 receptor domain–containing adaptor protein; TCR, T-cell receptor; IFNAR, IFN-α receptor; IL-R, IL receptor; CCR, CC-chemokine receptor.

Figure 5.

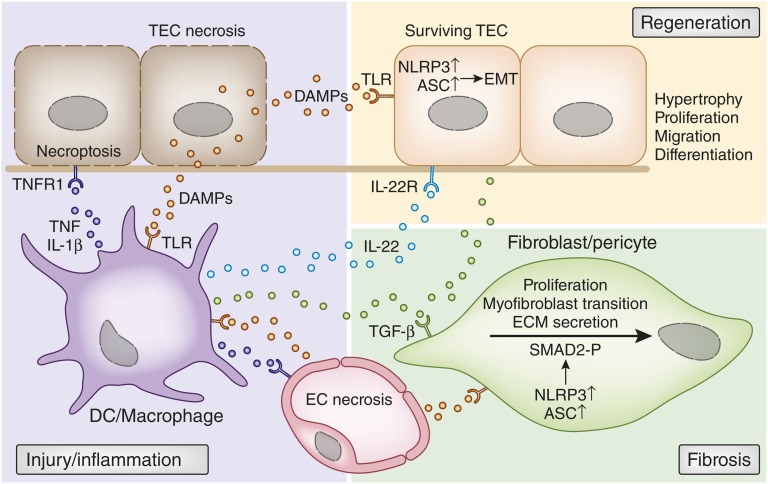

How DAMPs trigger immune injury, regeneration and fibrosis. Early injury-induced necrosis leads to DAMP release by renal endothelial and epithelial cells. These DAMPs activate pattern recognition receptors such as TLRs or inflammasomes in intrarenal mononuclear phagocytes such as dendritic cells (DCs) or macrophages. Upon activation, these cells produce inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that cause further renal cell necrosis, (e.g., by TNF-induced necroptosis). This autoamplification loop of injury and inflammation is further accelerated by chemokine-driven leukocyte influx (not shown). DAMP release by necrotic cells also triggers regenerative mechanisms, directly and indirectly. Certain DAMPs activate TLR2 on renal progenitor cells, which accelerates tubular repair. In addition, TLR4 activation of renal dendritic cells triggers IL-22 release, which specifically activates the IL-22 receptor on TECs and accelerates tubular re-epithelialization. DAMPs also trigger fibrosis by activating pericytes, fibroblasts, and mesangial cells (latter not shown). TLR activation induces NLRP3 and ASC expression, which are needed for SMAD2 phosphorylation as a critical step in TGF-β receptor signaling. This was DAMPs drive the transition into myofibroblasts, proliferation, and ECM secretion. The same process also triggers TGF-β receptor–dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition of renal epithelial cells. ASC, apoptotic speck protein; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; EC, endothelial cell.

DAMPs with Direct Killing Effects

Histones release not only activates TLR2, TLR4, and the NLRP23 inflammasome (Figure 4),89,94,98,99 but extracellular histones also elicit direct toxic effects on vascular endothelial cells.89,100 For example, histone injection into the renal artery results in widespread renal necrosis, which is only partially prevented in TLR2/TLR4-deficient mice.89 Whether histone-induced cell death is a passive or regulated form of necrosis (or both) is unknown to date.

DAMPs as Autoantigens

Some DAMPs are important autoantigens that drive intrarenal autoimmune disease. For example, when nucleosomes and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) are released from glomerular cells, they can promote glomerular binding of lupus autoantibodies that trigger lupus nephritis (Figure 4).89,101–103 Neutrophils undergoing NETosis can also be an important source of the DAMPs in lupus.104,105 In lupus, secondary necrosis of apoptotic cells exposes hypomethylated dsDNA or U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein to TLR7 and TLR9 in dendritic cells and B cells, which drives RNA and DNA autoantibody production, systemic inflammation, and lupus nephritis.

How DAMP Signaling Drives Kidney Regeneration

Recent data now suggest that DAMPs can accelerate tubule regeneration upon injury either in a direct or indirect manner.106 Renal progenitor cells are scattered along the thick limbs of the proximal and distal tubule segments of the human kidney.106–112 These cells have a higher stress resistance as terminally differentiated TECs and preferentially survive tubule injury.107 TLR2-agonistic DAMPs enhance the clonal expansion and differentiation of these progenitor cells within the tubule, which accelerates tubule regeneration (Figure 5).113,114 As a second mechanism of DAMP-driven kidney regeneration, TLR4-agonistic DAMPs activate interstitial dendritic cells and macrophages to release IL-22.115 IL-22, in turn, activates the IL-22 receptor, which is exclusively expressed on TECs (Figure 5). IL-22 receptor signaling accelerates tubule re-epithelialization from surviving TECs in the recovery phase of AKI.115 Whereas TLR4 blockade in the injury phase abrogates AKI by preventing immunopathology, TLR4 blockade in the regeneration phase delays tubule recovery.115 This dual role of TLR4 agonistic DAMPs in AKI illustrates that DAMPs confer not only immune injury but also wound healing as part of danger control.116 Thus, DAMPs that ligate TLR2 or TLR4 drive kidney regeneration.

How DAMP Signaling Affects Kidney Fibrosis/Sclerosis

Renal fibrosis is considered an aberrant form of injury- or stress-induced wound healing accompanied by excessive ECM deposition.31,117,118 Leukocytes secrete growth factors and matrix metalloproteinases that activate mesangial cells and interstitial fibroblasts to secrete ECM components.117,119 In addition, ECM-related DAMPs link renal inflammation and fibrogenesis by ligating TLRs, integrins, purinergic receptors, and inflammasomes, a process that also leads to the release of fibrogenic cytokines118 and chemoattractants63,120 (Figure 4). It is of particular interest that although intracellular and extracellular DAMPs are structurally unrelated, they often signal via TLR2/TLR4 as shared receptors (Table 1), thereby resulting in different downstream events depending on the initial trigger.37 Histones use TLR2/TLR4 to activate MyD88, NF-κB, and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and induction of IL-6 and TNF-α.89 Low molecular weight HA acts via TLR2/MyD88/IL receptor–associated kinase/protein kinase C-ζ or TLR4/MyD88 to trigger the production of chemokine ligands CCL3, CCL4, CXCL1, CCL5, and CCL2, as well as IL-12, IL-8, and TNF-α,121–123 although this could not be confirmed in mesangial cells.124 HS signals through the TLR4/MyD88 pathway and promotes dendritic cell maturation and production of proinflammatory IL-6 and IL-12.125 HS also induces the release of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in macrophages.126 Biglycan and decorin, endogenous ligands of TLR2/TLR4, activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, and NF-κB pathways, leading to the secretion of TNF-α, pro-IL-1β, and a series of chemoattractants for neutrophils, macrophages, and T/B lymphocytes in either a MyD88- or TIR domain–containing adapter inducing IFN-β–dependent manner.38,40,42,74,75,78 Importantly, both small leucine-rich proteoglycans are orchestrating signaling pathways of diverse receptors probably in a hierarchical manner to sequentially induce signaling pathways.37,39,43 For example, biglycan clusters TLR2/TLR4 with the purinergic P2X7 and P2X4 receptors, which activates NLRP395 (Figure 4, Table 1). The NLRP3 inflammasome triggers secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, which are involved in renal fibrogenesis.127–130 NLRP3 activation in TECs also drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition during progressive renal fibrosis,131 which is associated with progressive renal fibrosis. For example, Nlrp3−/− mice display reduced tubular injury and interstitial fibrosis upon unilateral ureteral ligation compared with wild-type animals.131 Another study found an effect on early renal vascular permeability, rather than fibrosis, in this model.132 A role for NLRP3 in fibrosis may not necessarily involve only canonical (caspase/IL-1β/IL-18–dependent) inflammasome activation,98,133 because NLRP3 has additional (noncanonical) roles in SMAD2/SMAD3 phosphorylation of the TGF-β1 receptor signaling pathway.134 Whether this mechanism also operates within fibroblasts (as proposed in Figure 5) remains speculative at this point.

However, DAMP signaling in fibrosis is not only restricted to inflammatory pathways. ECM-related DAMPs also modulate crosslinking of matrix components and cytokine signaling in fibrogenesis. For example, the HS-proteoglycan, syndecan interacts via its HS chains with transglutaminase type 2, an enzyme that promotes ECM crosslinking in fibrosis.135 Consistently, the lack of syndecan protects from renal fibrosis.135 In addition, fibronectin can induce fibroblast differentiation via interaction with α4β7 integrin.136 As another avenue of DAMPs regulating fibrogenesis, decorin sequesters TGF-β in the ECM137 or compete with TGF-β for receptor binding.138 Decorin also inhibits CTGF signaling in fibroblasts.77 In addition, decorin downregulates microRNA miR-21,78 which promotes interstitial fibrosis.139 Together, DAMPs also directly modulate ECM crosslinking and renal fibrogenesis (e.g., by modulating TGF-β and CTGF signaling).

DAMPs in Distinct Kidney Disorders

There is currently mostly experimental evidence for a role of DAMPs in kidney disease, as listed in detail in Table 1. Data obtained from mice deficient for DAMP receptors provide only indirect evidence on the role of DAMPs; hence, we do not further discuss this here because numerous reviews on this topic exist.8,10,140,141

AKI

Tubular Necrosis

Among kidney disorders, AKI is most frequently associated with cell necrosis, which implies DAMP release in acute tubular necrosis. For example, septic, ischemic, or toxic forms of tubular necrosis involve the release of histones and high-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1), which drive the associated sterile inflammatory and immunopathology that determines organ failure.89,100,142–146 In addition, lethality in sepsis relates to the release of HMGB1, histones, decorin, or biglycan.42,78,100,144 This process seems to preferentially involve DAMP-mediated endothelial dysfunction via TLR2/TLR4, which increases vascular permeability, shock, and hypoperfusion.89,100,147 HMGB1 also can facilitate ischemic preconditioning, which implies that HMGB1 exposure protects from subsequent postischemic AKI.148 This TLR2-mediated process involves the upregulation of Siglec as one of many counterregulatory mediators that limit DAMP-related immunity just like endotoxin tolerance.149 In addition, NLRP3-deficient mice were protected from postischemic AKI.150,151 However, apoptotic speck protein or caspase-1 deficiency as well as IL-1/IL-18 blockade were not protective, largely excluding an inflammasome-related role of NLRP3 in postischemic AKI and arguing for yet unknown noncanonical effects.152

GN

Necrotizing GN is another form of AKI that involves DAMP release from renal cells.153 Data on necrotizing GN are currently limited to models induced in TLR2/TLR4-deficient mice or to serum and tissue expression levels of HMGB1 that correlate with disease activity.154,155 However, histones are released from netting neutrophils in necrotizing GN,26 and contribute to glomerular necrosis in crescentic GN in a TLR2/TLR4-dependent manner (S. Kumar, unpublished data). Nuclear DAMPs also contribute to lupus nephritis by activating TLR7 and TLR9 outside and inside the kidney,86,156–158 as well as by activating dendritic cells and B cells, which enhances local as well as systemic autoimmunity.159

CKD

Diabetic Nephropathy

Inflammatory responses mediated by activation of TLR2, TLR4, and NLRP3 inflammasome play key roles in the progression of diabetic nephropathy (DN).160,161 Under diabetic conditions, NLRP3 is activated by intracellular reactive oxygen species or extracellular ATP.160,162 Furthermore, hyperglycemia evokes the expression of the ATP receptor P2X4 in renal TECs of patients with type 2 DN, and this correlates with IL-1 cytokine release.160 The production of another proinflammatory molecule (i.e., HA) is also induced by hyperglycemia through a protein kinase C/TGF-β pathway.163 Besides HA, several DAMPs, including the glucose-inducible HMGB1,164 biglycan, and decorin, are overexpressed in diabetic kidneys and may trigger inflammation by activating TLR2/TLR4 receptors and NLRP3 inflammasomes.47,51,165

Increased renal biglycan levels correlate with enhanced infiltration of macrophages and renal LDL accumulation, and appear to promote kidney injury. By contrast, because of its antiapoptotic effects on TECs and ability to neutralize TGF-β1 and CTGF, decorin is nephroprotective in DN.51 Whereas HA accumulation is considered as a marker of renal damage during DN and is potentially involved in the development of interstitial fibrosis,163 high molecular weight-HA reduces diabetes-induced renal injury.32,34,166 Thus, decorin and low molecular weight versus high molecular weight HA, orchestrating signaling of various receptors, appear to act in diabetic kidneys in a scenario more complex than canonical DAMPs.

Lupus Nephritis

Lupus nephritis involves immune activation by nuclear DAMPs that share autoantigen and autoadjuvant qualities.159 Ribonucleoproteins activate TLR7 and hypomethylated dsDNA activates TLR9 (Table 1), which enhances autoantigen presentation and the expansion of autoreactive lymphocytes.86 In addition, these TLR7- and TLR9-specific DAMPs trigger plasmacytoid dendritic cells to release IFN-α, which initiates antiviral gene transcription accounting for many of the unspecific (viral infection-like) symptoms of lupus167 and IFN-related glomerular pathology.168 Furthermore, TLR7- and TLR9-specific DAMPs activate intrarenal macrophages and dendritic cells toward an M1 phenotype, a process that accelerates immunopathology in lupus nephritis.156,169,170 In addition, DAMP ligands of TLR2/TLR4 accelerate renal damage in lupus nephritis.38 Biglycan also aggravates lupus nephritis.38 Transient overexpression of soluble biglycan induces CCL2, CCL3, and CCL5 and aggravates murine lupus nephritis, whereas its deficiency suppresses disease activity and renal damage.38

Crystalline Nephropathies

Crystal formation within the kidney creates a DAMP that has the potential to activate renal inflammation and immunopathology via the NLRP3 inflammasome (e.g., in renal dendritic cells).82,83 For this to occur, crystals need to reach the interstitial compartment, which happens during diffuse crystallization or upon tubular injury from inside the tubular lumen. NLRP3 activation results in IL-1β and IL-18 secretion, which initiates downstream inflammatory effects by activating their respective IL receptors.84 This was consistently demonstrated in animal models of acute and chronic oxalate nephropathy as well as adenine overload-induced CKD (Table 1).84,97,171

Summary

Tissue injury emits DAMPs as danger signals to activate danger control (e.g., inflammation for host defense). DAMPs can either be intracellular molecules that signal cell necrosis (HMGB1, histones, ATP), matrix constituents that signal extensive matrix remodeling (decorin, HA, HS, biglycan), or luminal factors that signal barrier destruction (uromodulin). DAMPs activate TLRs, purinergic receptors, and inflammasomes in parenchymal cells and leukocytes. DAMP-induced inflammation initiates an autoamplification loop by triggering regulated forms of necrotic cell death, which aggravates immunopathology and further DAMP release. Hence, blocking DAMP signaling in the early injury phase of acute disorders limits immunopathology. However, DAMPs have additional effects. Certain nuclear DAMPs (RNA/DNA) combine autoadjuvant and autoantigen qualities and thereby promote systemic lupus and lupus nephritis. TLR2-agonistic DAMPs activate renal progenitor cells to regenerate epithelial defects in injured tubules. TLR4-agonistic DAMPs induce renal dendritic cells to release IL-22, which also accelerates tubule re-epithelialization in AKI. Finally, DAMPs also promote renal fibrosis by inducing NLRP3, which also promotes TGF-β receptor signaling. It is likely that more exciting discoveries are to be made in this area.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

H.J.A. and L.S. are supported by the German Research Foundation (AN372/9-2 and 14-1 to H.J.A.; and Sonderforschungsbereich (SFB) 815, project A5, SFB 1039, project B2, Excellence Cluster Cardio-Pulmonary System and Landes-Offensive zur Entwicklung Wissenschaftlich-ökonomischer Exzellenz program Ub-Net to L.S.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Wallach D, Kang TB, Kovalenko A: Concepts of tissue injury and cell death in inflammation: A historical perspective. Nat Rev Immunol 14: 51–59, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medzhitov R: Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454: 428–435, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matzinger P: Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol 12: 991–1045, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurts C, Panzer U, Anders HJ, Rees AJ: The immune system and kidney disease: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 738–753, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leemans JC, Stokman G, Claessen N, Rouschop KM, Teske GJ, Kirschning CJ, Akira S, van der Poll T, Weening JJ, Florquin S: Renal-associated TLR2 mediates ischemia/reperfusion injury in the kidney. J Clin Invest 115: 2894–2903, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu H, Chen G, Wyburn KR, Yin J, Bertolino P, Eris JM, Alexander SI, Sharland AF, Chadban SJ: TLR4 activation mediates kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 117: 2847–2859, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rock KL, Latz E, Ontiveros F, Kono H: The sterile inflammatory response. Annu Rev Immunol 28: 321–342, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anders HJ: Toll-like receptors and danger signaling in kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1270–1274, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anders HJ, Banas B, Schlöndorff D: Signaling danger: Toll-like receptors and their potential roles in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 854–867, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anders HJ, Muruve DA: The inflammasomes in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1007–1018, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosin DL, Okusa MD: Dangers within: DAMP responses to damage and cell death in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 416–425, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotchkiss RS, Strasser A, McDunn JE, Swanson PE: Cell death. N Engl J Med 361: 1570–1583, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravichandran KS: Beginnings of a good apoptotic meal: The find-me and eat-me signaling pathways. Immunity 35: 445–455, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM: Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest 101: 890–898, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freire-de-Lima CG, Nascimento DO, Soares MB, Bozza PT, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, de Mello FG, DosReis GA, Lopes MF: Uptake of apoptotic cells drives the growth of a pathogenic trypanosome in macrophages. Nature 403: 199–203, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grasl-Kraupp B, Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Koudelka H, Bukowska K, Bursch W, Schulte-Hermann R: In situ detection of fragmented DNA (TUNEL assay) fails to discriminate among apoptosis, necrosis, and autolytic cell death: A cautionary note. Hepatology 21: 1465–1468, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P: Regulated necrosis: The expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 135–147, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linkermann A, Green D: Mechanisms of disease: Necroptosis. N Engl J Med 370: 455–465, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau A, Wang S, Jiang J, Haig A, Pavlosky A, Linkermann A, Zhang ZX, Jevnikar AM: RIPK3-mediated necroptosis promotes donor kidney inflammatory injury and reduces allograft survival. Am J Transplant 13: 2805–2818, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linkermann A, Bräsen JH, Darding M, Jin MK, Sanz AB, Heller JO, De Zen F, Weinlich R, Ortiz A, Walczak H, Weinberg JM, Green DR, Kunzendorf U, Krautwald S: Two independent pathways of regulated necrosis mediate ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 12024–12029, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linkermann A, Bräsen JH, Himmerkus N, Liu S, Huber TB, Kunzendorf U, Krautwald S: Rip1 (receptor-interacting protein kinase 1) mediates necroptosis and contributes to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int 81: 751–761, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linkermann A, Heller JO, Prókai A, Weinberg JM, De Zen F, Himmerkus N, Szabó AJ, Bräsen JH, Kunzendorf U, Krautwald S: The RIP1-kinase inhibitor necrostatin-1 prevents osmotic nephrosis and contrast-induced AKI in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1545–1557, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tristão VR, Gonçalves PF, Dalboni MA, Batista MC, Durão MS, Jr, Monte JC: Nec-1 protects against nonapoptotic cell death in cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Ren Fail 34: 373–377, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison B, 3rd, Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149: 1060–1072, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A: Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303: 1532–1535, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessenbrock K, Krumbholz M, Schönermarck U, Back W, Gross WL, Werb Z, Gröne HJ, Brinkmann V, Jenne DE: Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med 15: 623–625, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Case CL, Kohler LJ, Lima JB, Strowig T, de Zoete MR, Flavell RA, Zamboni DS, Roy CR: Caspase-11 stimulates rapid flagellin-independent pyroptosis in response to Legionella pneumophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 1851–1856, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fink SL, Cookson BT: Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell Microbiol 8: 1812–1825, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krautwald S, Linkermann A: The fire within: Pyroptosis in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F168–F169, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang JR, Yao FH, Zhang JG, Ji ZY, Li KL, Zhan J, Tong YN, Lin LR, He YN: Ischemia-reperfusion induces renal tubule pyroptosis via the CHOP-caspase-11 pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F75–F84, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wight TN, Potter-Perigo S: The extracellular matrix: An active or passive player in fibrosis? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301: G950–G955, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Mascarenhas MM, Garg HG, Quinn DA, Homer RJ, Goldstein DR, Bucala R, Lee PJ, Medzhitov R, Noble PW: Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med 11: 1173–1179, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW: Hyaluronan in tissue injury and repair. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23: 435–461, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noble PW: Hyaluronan and its catabolic products in tissue injury and repair. Matrix Biol 21: 25–29, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noble PW, Jiang D: Matrix regulation of lung injury, inflammation, and repair: The role of innate immunity. Proc Am Thorac Soc 3: 401–404, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaefer L: Small leucine-rich proteoglycans in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1200–1207, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frey H, Schroeder N, Manon-Jensen T, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L: Biological interplay between proteoglycans and their innate immune receptors in inflammation. FEBS J 280: 2165–2179, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreth K, Brodbeck R, Babelova A, Gretz N, Spieker T, Zeng-Brouwers J, Pfeilschifter J, Young MF, Schaefer RM, Schaefer L: The proteoglycan biglycan regulates expression of the B cell chemoattractant CXCL13 and aggravates murine lupus nephritis. J Clin Invest 120: 4251–4272, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreth K, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L: Small leucine-rich proteoglycans orchestrate receptor crosstalk during inflammation. Cell Cycle 11: 2084–2091, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nastase MV, Young MF, Schaefer L: Biglycan: A multivalent proteoglycan providing structure and signals. J Histochem Cytochem 60: 963–975, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaefer L: Extracellular matrix molecules: endogenous danger signals as new drug targets in kidney diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol 10: 185–190, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaefer L, Babelova A, Kiss E, Hausser HJ, Baliova M, Krzyzankova M, Marsche G, Young MF, Mihalik D, Götte M, Malle E, Schaefer RM, Gröne HJ: The matrix component biglycan is proinflammatory and signals through Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in macrophages. J Clin Invest 115: 2223–2233, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaefer L, Iozzo RV: Small leucine-rich proteoglycans, at the crossroad of cancer growth and inflammation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 22: 56–57, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaefer L, Schaefer RM: Proteoglycans: From structural compounds to signaling molecules. Cell Tissue Res 339: 237–246, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sorokin L: The impact of the extracellular matrix on inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 10: 712–723, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaefer L, Gröne HJ, Raslik I, Robenek H, Ugorcakova J, Budny S, Schaefer RM, Kresse H: Small proteoglycans of normal adult human kidney: Distinct expression patterns of decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin, and lumican. Kidney Int 58: 1557–1568, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaefer L, Raslik I, Grone HJ, Schonherr E, Macakova K, Ugorcakova J, Budny S, Schaefer RM, Kresse H: Small proteoglycans in human diabetic nephropathy: Discrepancy between glomerular expression and protein accumulation of decorin, biglycan, lumican, and fibromodulin. FASEB J 15: 559–561, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaefer L, Mihalik D, Babelova A, Krzyzankova M, Gröne HJ, Iozzo RV, Young MF, Seidler DG, Lin G, Reinhardt DP, Schaefer RM: Regulation of fibrillin-1 by biglycan and decorin is important for tissue preservation in the kidney during pressure-induced injury. Am J Pathol 165: 383–396, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaefer L, Macakova K, Raslik I, Micegova M, Gröne HJ, Schönherr E, Robenek H, Echtermeyer FG, Grässel S, Bruckner P, Schaefer RM, Iozzo RV, Kresse H: Absence of decorin adversely influences tubulointerstitial fibrosis of the obstructed kidney by enhanced apoptosis and increased inflammatory reaction. Am J Pathol 160: 1181–1191, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaefer L, Tsalastra W, Babelova A, Baliova M, Minnerup J, Sorokin L, Gröne HJ, Reinhardt DP, Pfeilschifter J, Iozzo RV, Schaefer RM: Decorin-mediated regulation of fibrillin-1 in the kidney involves the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and mammalian target of rapamycin. Am J Pathol 170: 301–315, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merline R, Lazaroski S, Babelova A, Tsalastra-Greul W, Pfeilschifter J, Schluter KD, Gunther A, Iozzo RV, Schaefer RM, Schaefer L: Decorin deficiency in diabetic mice: Aggravation of nephropathy due to overexpression of profibrotic factors, enhanced apoptosis and mononuclear cell infiltration. J Physiol Pharmacol 60[Suppl 4]: 5–13, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merline R, Schaefer RM, Schaefer L: The matricellular functions of small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs). J Cell Commun Signal 3: 323–335, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnsson C, Tufveson G, Wahlberg J, Hällgren R: Experimentally-induced warm renal ischemia induces cortical accumulation of hyaluronan in the kidney. Kidney Int 50: 1224–1229, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wüthrich RP: The proinflammatory role of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions in renal injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 2554–2556, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wells A, Larsson E, Hanás E, Laurent T, Hällgren R, Tufveson G: Increased hyaluronan in acutely rejecting human kidney grafts. Transplantation 55: 1346–1349, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sibalic V, Fan X, Loffing J, Wüthrich RP: Upregulated renal tubular CD44, hyaluronan, and osteopontin in kdkd mice with interstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 1344–1353, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feusi E, Sun L, Sibalic A, Beck-Schimmer B, Oertli B, Wüthrich RP: Enhanced hyaluronan synthesis in the MRL-Fas(lpr) kidney: Role of cytokines. Nephron 83: 66–73, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meirovitz A, Goldberg R, Binder A, Rubinstein AM, Hermano E, Elkin M: Heparanase in inflammation and inflammation-associated cancer. FEBS J 280: 2307–2319, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vlodavsky I, Iozzo RV, Sanderson RD: Heparanase: Multiple functions in inflammation, diabetes and atherosclerosis. Matrix Biol 32: 220–222, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldberg R, Meirovitz A, Hirshoren N, Bulvik R, Binder A, Rubinstein AM, Elkin M: Versatile role of heparanase in inflammation. Matrix Biol 32: 234–240, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parish CR, Freeman C, Ziolkowski AF, He YQ, Sutcliffe EL, Zafar A, Rao S, Simeonovic CJ: Unexpected new roles for heparanase in type 1 diabetes and immune gene regulation. Matrix Biol 32: 228–233, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shafat I, Agbaria A, Boaz M, Schwartz D, Baruch R, Nakash R, Ilan N, Vlodavsky I, Weinstein T: Elevated urine heparanase levels are associated with proteinuria and decreased renal allograft function. PLoS ONE 7: e44076, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eddy AA: Molecular basis of renal fibrosis. Pediatr Nephrol 15: 290–301, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Monaco S, Sparano V, Gioia M, Sbardella D, Di Pierro D, Marini S, Coletta M: Enzymatic processing of collagen IV by MMP-2 (gelatinase A) affects neutrophil migration and it is modulated by extracatalytic domains. Protein Sci 15: 2805–2815, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riggins KS, Mernaugh G, Su Y, Quaranta V, Koshikawa N, Seiki M, Pozzi A, Zent R: MT1-MMP-mediated basement membrane remodeling modulates renal development. Exp Cell Res 316: 2993–3005, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boor P, Ostendorf T, Floege J: Renal fibrosis: Novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Nephrol 6: 643–656, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nony PA, Schnellmann RG: Interactions between collagen IV and collagen-binding integrins in renal cell repair after sublethal injury. Mol Pharmacol 60: 1226–1234, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scott IC, Imamura Y, Pappano WN, Troedel JM, Recklies AD, Roughley PJ, Greenspan DS: Bone morphogenetic protein-1 processes probiglycan. J Biol Chem 275: 30504–30511, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Calabrese GC, Gazzaniga S, Oberkersch R, Wainstok R: Decorin and biglycan expression: Its relation with endothelial heterogeneity. Histol Histopathol 26: 481–490, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boivin WA, Shackleford M, Vanden Hoek A, Zhao H, Hackett TL, Knight DA, Granville DJ: Granzyme B cleaves decorin, biglycan and soluble betaglycan, releasing active transforming growth factor-β1. PLoS ONE 7: e33163, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Monfort J, Tardif G, Reboul P, Mineau F, Roughley P, Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J: Degradation of small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycans by matrix metalloprotease-13: identification of a new biglycan cleavage site. Arthritis Res Ther 8: R26, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Genovese F, Barascuk N, Larsen L, Larsen MR, Nawrocki A, Li Y, Zheng Q, Wang J, Veidal SS, Leeming DJ, Karsdal MA: Biglycan fragmentation in pathologies associated with extracellular matrix remodeling by matrix metalloproteinases. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 6: 9, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nastase MV, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L: Key roles for the small leucine-rich proteoglycans in renal and pulmonary pathophysiology [published online ahead of print February 5, 2014]. Biochim Biophys Acta 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moreth K, Frey H, Hubo M, Zeng-Brouwers J, Nastase MV, Hsieh LT, Haceni R, Pfeilschifter J, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L: Biglycan-triggered TLR-2- and TLR-4-signaling exacerbates the pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury [published online ahead of print January 28, 2014]. Matrix Biol 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zeng-Brouwers J, Beckmann J, Nastase MV, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L: De novo expression of circulating biglycan evokes an innate inflammatory tissue response via MyD88/TRIF pathways [published online ahead of print December 18, 2013]. Matrix Biol 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jyo Y, Sasaki T, Nomura S, Tamai H, Kawai S, Osawa G, Nakao N, Kusakabe M: Expression of tenascin in mesangial injury in experimental glomerulonephritis. Exp Nephrol 5: 423–428, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vial C, Gutiérrez J, Santander C, Cabrera D, Brandan E: Decorin interacts with connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)/CCN2 by LRR12 inhibiting its biological activity. J Biol Chem 286: 24242–24252, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Merline R, Moreth K, Beckmann J, Nastase MV, Zeng-Brouwers J, Tralhão JG, Lemarchand P, Pfeilschifter J, Schaefer RM, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L: Signaling by the matrix proteoglycan decorin controls inflammation and cancer through PDCD4 and MicroRNA-21. Sci Signal 4: ra75, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.El-Achkar TM, Wu XR: Uromodulin in kidney injury: An instigator, bystander, or protector? Am J Kidney Dis 59: 452–461, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Säemann MD, Weichhart T, Zeyda M, Staffler G, Schunn M, Stuhlmeier KM, Sobanov Y, Stulnig TM, Akira S, von Gabain A, von Ahsen U, Hörl WH, Zlabinger GJ: Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein links innate immune cell activation with adaptive immunity via a Toll-like receptor-4-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest 115: 468–475, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Darisipudi MN, Thomasova D, Mulay SR, Brech D, Noessner E, Liapis H, Anders HJ: Uromodulin triggers IL-1β-dependent innate immunity via the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1783–1789, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J: Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440: 237–241, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mulay SR, Evan A, Anders HJ: Molecular mechanisms of crystal-related kidney inflammation and injury. Implications for cholesterol embolism, crystalline nephropathies and kidney stone disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 507–514, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mulay SR, Kulkarni OP, Rupanagudi KV, Migliorini A, Darisipudi MN, Vilaysane A, Muruve D, Shi Y, Munro F, Liapis H, Anders HJ: Calcium oxalate crystals induce renal inflammation by NLRP3-mediated IL-1β secretion. J Clin Invest 123: 236–246, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leventhal JS, Schröppel B: Toll-like receptors in transplantation: Sensing and reacting to injury. Kidney Int 81: 826–832, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marshak-Rothstein A, Rifkin IR: Immunologically active autoantigens: The role of toll-like receptors in the development of chronic inflammatory disease. Annu Rev Immunol 25: 419–441, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Allam R, Anders HJ: The role of innate immunity in autoimmune tissue injury. Curr Opin Rheumatol 20: 538–544, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Anders HJ, Schlöndorff D: Toll-like receptors: Emerging concepts in kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16: 177–183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Allam R, Scherbaum CR, Darisipudi MN, Mulay SR, Hägele H, Lichtnekert J, Hagemann JH, Rupanagudi KV, Ryu M, Schwarzenberger C, Hohenstein B, Hugo C, Uhl B, Reichel CA, Krombach F, Monestier M, Liapis H, Moreth K, Schaefer L, Anders HJ: Histones from dying renal cells aggravate kidney injury via TLR2 and TLR4. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1375–1388, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Banas MC, Banas B, Hudkins KL, Wietecha TA, Iyoda M, Bock E, Hauser P, Pippin JW, Shankland SJ, Smith KD, Stoelcker B, Liu G, Gröne HJ, Krämer BK, Alpers CE: TLR4 links podocytes with the innate immune system to mediate glomerular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 704–713, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gurkan S, Cabinian A, Lopez V, Bhaumik M, Chang JM, Rabson AB, Mundel P: Inhibition of type I interferon signalling prevents TLR ligand-mediated proteinuria. J Pathol 231: 248–256, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Khandoga AG, Khandoga A, Anders HJ, Krombach F: Postischemic vascular permeability requires both TLR-2 and TLR-4, but only TLR-2 mediates the transendothelial migration of leukocytes. Shock 31: 592–598, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pawar RD, Castrezana-Lopez L, Allam R, Kulkarni OP, Segerer S, Radomska E, Meyer TN, Schwesinger CM, Akis N, Gröne HJ, Anders HJ: Bacterial lipopeptide triggers massive albuminuria in murine lupus nephritis by activating Toll-like receptor 2 at the glomerular filtration barrier. Immunology 128[Suppl]: e206–e221, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Allam R, Darisipudi MN, Tschopp J, Anders HJ: Histones trigger sterile inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur J Immunol 43: 3336–3342, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Babelova A, Moreth K, Tsalastra-Greul W, Zeng-Brouwers J, Eickelberg O, Young MF, Bruckner P, Pfeilschifter J, Schaefer RM, Gröne HJ, Schaefer L: Biglycan, a danger signal that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via toll-like and P2X receptors. J Biol Chem 284: 24035–24048, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schroder K, Tschopp J: The inflammasomes. Cell 140: 821–832, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Knauf F, Asplin JR, Granja I, Schmidt IM, Moeckel GW, David RJ, Flavell RA, Aronson PS: NALP3-mediated inflammation is a principal cause of progressive renal failure in oxalate nephropathy. Kidney Int 84: 895–901, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lorenz G, Darisipudi MN, Anders HJ: Canonical and non-canonical effects of the NLRP3 inflammasome in kidney inflammation and fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 41–48, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xu J, Zhang X, Monestier M, Esmon NL, Esmon CT: Extracellular histones are mediators of death through TLR2 and TLR4 in mouse fatal liver injury. J Immunol 187: 2626–2631, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, Monestier M, Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, Taylor FB, Esmon NL, Lupu F, Esmon CT: Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med 15: 1318–1321, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fenton KA, Tømmerås B, Marion TN, Rekvig OP: Pure anti-dsDNA mAbs need chromatin structures to promote glomerular mesangial deposits in BALB/c mice. Autoimmunity 43: 179–188, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mjelle JE, Rekvig OP, Van Der Vlag J, Fenton KA: Nephritogenic antibodies bind in glomeruli through interaction with exposed chromatin fragments and not with renal cross-reactive antigens. Autoimmunity 44: 373–383, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mortensen ES, Rekvig OP: Nephritogenic potential of anti-DNA antibodies against necrotic nucleosomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 696–704, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bosch X: Systemic lupus erythematosus and the neutrophil. N Engl J Med 365: 758–760, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hakkim A, Fürnrohr BG, Amann K, Laube B, Abed UA, Brinkmann V, Herrmann M, Voll RE, Zychlinsky A: Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 9813–9818, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Romagnani P, Anders HJ: What can tubular progenitor cultures teach us about kidney regeneration? Kidney Int 83: 351–353, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Angelotti ML, Ronconi E, Ballerini L, Peired A, Mazzinghi B, Sagrinati C, Parente E, Gacci M, Carini M, Rotondi M, Fogo AB, Lazzeri E, Lasagni L, Romagnani P: Characterization of renal progenitors committed toward tubular lineage and their regenerative potential in renal tubular injury. Stem Cells 30: 1714–1725, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gupta S, Verfaillie C, Chmielewski D, Kren S, Eidman K, Connaire J, Heremans Y, Lund T, Blackstad M, Jiang Y, Luttun A, Rosenberg ME: Isolation and characterization of kidney-derived stem cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3028–3040, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kitamura S, Yamasaki Y, Kinomura M, Sugaya T, Sugiyama H, Maeshima Y, Makino H: Establishment and characterization of renal progenitor like cells from S3 segment of nephron in rat adult kidney. FASEB J 19: 1789–1797, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Langworthy M, Zhou B, de Caestecker M, Moeckel G, Baldwin HS: NFATc1 identifies a population of proximal tubule cell progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 311–321, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lindgren D, Boström AK, Nilsson K, Hansson J, Sjölund J, Möller C, Jirström K, Nilsson E, Landberg G, Axelson H, Johansson ME: Isolation and characterization of progenitor-like cells from human renal proximal tubules. Am J Pathol 178: 828–837, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Maeshima A, Yamashita S, Nojima Y: Identification of renal progenitor-like tubular cells that participate in the regeneration processes of the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 3138–3146, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sallustio F, Costantino V, Cox SN, Loverre A, Divella C, Rizzi M, Schena FP: Human renal stem/progenitor cells repair tubular epithelial cell injury through TLR2-driven inhibin-A and microvesicle-shuttled decorin. Kidney Int 83: 392–403, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sallustio F, De Benedictis L, Castellano G, Zaza G, Loverre A, Costantino V, Grandaliano G, Schena FP: TLR2 plays a role in the activation of human resident renal stem/progenitor cells. FASEB J 24: 514–525, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kulkarni OP, Hartter I, Mulay SR, Hagemann J, Darisipudi MN, Kumar VR S, Romoli S, Thomasova D, Ryu M, Kobold S, Anders HJ: Toll-like receptor 4-induced IL-22 accelerates kidney regeneration [published online ahead of print January 23, 2014]. J Am Soc Nephrol 10.1681/ASN.2013050528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Anders HJ: Four danger response programs determine glomerular and tubulointerstitial kidney pathology: Clotting, inflammation, epithelial and mesenchymal healing. Organogenesis 8: 29–40, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu Y: Cellular and molecular mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 7: 684–696, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee SB, Kalluri R: Mechanistic connection between inflammation and fibrosis. Kidney Int Suppl 119: S22–S26, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Liu Y: Renal fibrosis: New insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int 69: 213–217, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chung AC, Lan HY: Chemokines in renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 802–809, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.McKee CM, Penno MB, Cowman M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Bao C, Noble PW: Hyaluronan (HA) fragments induce chemokine gene expression in alveolar macrophages. The role of HA size and CD44. J Clin Invest 98: 2403–2413, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hodge-Dufour J, Noble PW, Horton MR, Bao C, Wysoka M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Trinchieri G, Puré E: Induction of IL-12 and chemokines by hyaluronan requires adhesion-dependent priming of resident but not elicited macrophages. J Immunol 159: 2492–2500, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Black KE, Collins SL, Hagan RS, Hamblin MJ, Chan-Li Y, Hallowell RW, Powell JD, Horton MR: Hyaluronan fragments induce IFNβ via a novel TLR4-TRIF-TBK1-IRF3-dependent pathway. J Inflamm (Lond) 10: 23, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ebid R, Lichtnekert J, Anders HJ: Hyaluronan is not a ligand but a regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling in mesangial cells. Role of extracellular matrix in innate immunity [published online ahead of print January 21, 2014]. ISRN Nephrol 10.1155/2014/714081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Brennan TV, Lin L, Huang X, Cardona DM, Li Z, Dredge K, Chao NJ, Yang Y: Heparan sulfate, an endogenous TLR4 agonist, promotes acute GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 120: 2899–2908, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wrenshall LE, Stevens RB, Cerra FB, Platt JL: Modulation of macrophage and B cell function by glycosaminoglycans. J Leukoc Biol 66: 391–400, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bani-Hani AH, Leslie JA, Asanuma H, Dinarello CA, Campbell MT, Meldrum DR, Zhang H, Hile K, Meldrum KK: IL-18 neutralization ameliorates obstruction-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and renal fibrosis. Kidney Int 76: 500–511, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jones LK, O’Sullivan KM, Semple T, Kuligowski MP, Fukami K, Ma FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR: IL-1RI deficiency ameliorates early experimental renal interstitial fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3024–3032, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vesey DA, Cheung C, Cuttle L, Endre Z, Gobe G, Johnson DW: Interleukin-1beta stimulates human renal fibroblast proliferation and matrix protein production by means of a transforming growth factor-beta-dependent mechanism. J Lab Clin Med 140: 342–350, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Vesey DA, Cheung CW, Cuttle L, Endre ZA, Gobé G, Johnson DW: Interleukin-1beta induces human proximal tubule cell injury, alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and fibronectin production. Kidney Int 62: 31–40, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vilaysane A, Chun J, Seamone ME, Wang W, Chin R, Hirota S, Li Y, Clark SA, Tschopp J, Trpkov K, Hemmelgarn BR, Beck PL, Muruve DA: The NLRP3 inflammasome promotes renal inflammation and contributes to CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1732–1744, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pulskens WP, Butter LM, Teske GJ, Claessen N, Dessing MC, Flavell RA, Sutterwala FS, Florquin S, Leemans JC: Nlrp3 prevents early renal interstitial edema and vascular permeability in unilateral ureteral obstruction. PLoS ONE 9: e85775, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Anders HJ, Lech M: NOD-like and Toll-like receptors or inflammasomes contribute to kidney disease in a canonical and a non-canonical manner. Kidney Int 84: 225–228, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wang W, Wang X, Chun J, Vilaysane A, Clark S, French G, Bracey NA, Trpkov K, Bonni S, Duff HJ, Beck PL, Muruve DA: Inflammasome-independent NLRP3 augments TGF-β signaling in kidney epithelium. J Immunol 190: 1239–1249, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Scarpellini A, Huang L, Burhan I, Schroeder N, Funck M, Johnson TS, Verderio EA: Syndecan-4 knockout leads to reduced extracellular transglutaminase-2 and protects against tubulointerstitial fibrosis [published online ahead of print December 19, 2013]. J Am Soc Nephrol 10.1681/ASN.2013050563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.To WS, Midwood KS: Plasma and cellular fibronectin: Distinct and independent functions during tissue repair. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 4: 21, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yamaguchi Y, Mann DM, Ruoslahti E: Negative regulation of transforming growth factor-beta by the proteoglycan decorin. Nature 346: 281–284, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Droguett R, Cabello-Verrugio C, Riquelme C, Brandan E: Extracellular proteoglycans modify TGF-beta bio-availability attenuating its signaling during skeletal muscle differentiation. Matrix Biol 25: 332–341, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Glowacki F, Savary G, Gnemmi V, Buob D, Van der Hauwaert C, Lo-Guidice JM, Bouyé S, Hazzan M, Pottier N, Perrais M, Aubert S, Cauffiez C: Increased circulating miR-21 levels are associated with kidney fibrosis. PLoS ONE 8: e58014, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Eleftheriadis T, Pissas G, Liakopoulos V, Stefanidis I, Lawson BR: Toll-like receptors and their role in renal pathologies. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 11: 464–477, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Leemans JC, et al. : Toll-like receptors, NOD-like receptors and the inflammasome in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol in minor revision, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Leelahavanichkul A, Huang Y, Hu X, Zhou H, Tsuji T, Chen R, Kopp JB, Schnermann J, Yuen PS, Star RA: Chronic kidney disease worsens sepsis and sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by releasing High Mobility Group Box Protein-1. Kidney Int 80: 1198–1211, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Rabadi MM, Ghaly T, Goligorksy MS, Ratliff BB: HMGB1 in renal ischemic injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F873–F885, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ: HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 285: 248–251, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wu H, Ma J, Wang P, Corpuz TM, Panchapakesan U, Wyburn KR, Chadban SJ: HMGB1 contributes to kidney ischemia reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1878–1890, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Arumugam TV, Okun E, Tang SC, Thundyil J, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM: Toll-like receptors in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shock 32: 4–16, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Treutiger CJ, Mullins GE, Johansson AS, Rouhiainen A, Rauvala HM, Erlandsson-Harris H, Andersson U, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Andersson J, Palmblad JE: High mobility group 1 B-box mediates activation of human endothelium. J Intern Med 254: 375–385, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wu H, Steenstra R, de Boer EC, Zhao CY, Ma J, van der Stelt JM, Chadban SJ: Preconditioning with recombinant high-mobility group box 1 protein protects the kidney against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Kidney Int 85: 824–832, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Günthner R, Kumar VR, Lorenz G, Anders HJ, Lech M: Pattern-recognition receptor signaling regulator mRNA expression in humans and mice, and in transient inflammation or progressive fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 14: 18124–18147, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Iyer SS, Pulskens WP, Sadler JJ, Butter LM, Teske GJ, Ulland TK, Eisenbarth SC, Florquin S, Flavell RA, Leemans JC, Sutterwala FS: Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 20388–20393, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Shigeoka AA, Holscher TD, King AJ, Hall FW, Kiosses WB, Tobias PS, Mackman N, McKay DB: TLR2 is constitutively expressed within the kidney and participates in ischemic renal injury through both MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol 178: 6252–6258, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Shigeoka AA, Mueller JL, Kambo A, Mathison JC, King AJ, Hall WF, Correia JS, Ulevitch RJ, Hoffman HM, McKay DB: An inflammasome-independent role for epithelial-expressed Nlrp3 in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Immunol 185: 6277–6285, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Lichtnekert J, Vielhauer V, Zecher D, Kulkarni OP, Clauss S, Segerer S, Hornung V, Mayadas TN, Beutler B, Akira S, Anders HJ: Trif is not required for immune complex glomerulonephritis: Dying cells activate mesangial cells via Tlr2/Myd88 rather than Tlr3/Trif. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F867–F874, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Zickert A, Palmblad K, Sundelin B, Chavan S, Tracey KJ, Bruchfeld A, Gunnarsson I: Renal expression and serum levels of high mobility group box 1 protein in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res Ther 14: R36, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Bruchfeld A, Wendt M, Bratt J, Qureshi AR, Chavan S, Tracey KJ, Palmblad K, Gunnarsson I: High-mobility group box-1 protein (HMGB1) is increased in antineutrophilic cytoplasmatic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis with renal manifestations. Mol Med 17: 29–35, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Patole PS, Zecher D, Pawar RD, Gröne HJ, Schlöndorff D, Anders HJ: G-rich DNA suppresses systemic lupus. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3273–3280, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Pawar RD, Ramanjaneyulu A, Kulkarni OP, Lech M, Segerer S, Anders HJ: Inhibition of Toll-like receptor-7 (TLR-7) or TLR-7 plus TLR-9 attenuates glomerulonephritis and lung injury in experimental lupus. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1721–1731, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Christensen SR, Shupe J, Nickerson K, Kashgarian M, Flavell RA, Shlomchik MJ: Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity 25: 417–428, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Lech M, Anders HJ: The pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1357–1366, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Chen K, Zhang J, Zhang W, Zhang J, Yang J, Li K, He Y: ATP-P2X4 signaling mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation: A novel pathway of diabetic nephropathy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 932–943, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Lin M, Yiu WH, Li RX, Wu HJ, Wong DW, Chan LY, Leung JC, Lai KN, Tang SC: The TLR4 antagonist CRX-526 protects against advanced diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 83: 887–900, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J: Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol 11: 136–140, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Stridh S, Palm F, Hansell P: Renal interstitial hyaluronan: Functional aspects during normal and pathological conditions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R1235–R1249, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Mudaliar H, Pollock C, Komala MG, Chadban S, Wu H, Panchapakesan U: The role of Toll-like receptor proteins (TLR) 2 and 4 in mediating inflammation in proximal tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F143–F154, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Thompson J, Wilson P, Brandewie K, Taneja D, Schaefer L, Mitchell B, Tannock LR: Renal accumulation of biglycan and lipid retention accelerates diabetic nephropathy. Am J Pathol 179: 1179–1187, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Campo GM, Avenoso A, Micali A, Nastasi G, Squadrito F, Altavilla D, Bitto A, Polito F, Rinaldi MG, Calatroni A, D’Ascola A, Campo S: High-molecular weight hyaluronan reduced renal PKC activation in genetically diabetic mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802: 1118–1130, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Migliorini A, Anders HJ: A novel pathogenetic concept-antiviral immunity in lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 183–189, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Migliorini A, Angelotti ML, Mulay SR, Kulkarni OO, Demleitner J, Dietrich A, Sagrinati C, Ballerini L, Peired A, Shankland SJ, Liapis H, Romagnani P, Anders HJ: The antiviral cytokines IFN-α and IFN-β modulate parietal epithelial cells and promote podocyte loss: Implications for IFN toxicity, viral glomerulonephritis, and glomerular regeneration. Am J Pathol 183: 431–440, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Pawar RD, Patole PS, Ellwart A, Lech M, Segerer S, Schlondorff D, Anders HJ: Ligands to nucleic acid-specific toll-like receptors and the onset of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3365–3373, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Pawar RD, Patole PS, Zecher D, Segerer S, Kretzler M, Schlöndorff D, Anders HJ: Toll-like receptor-7 modulates immune complex glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 141–149, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Correa-Costa M, Braga TT, Semedo P, Hayashida CY, Bechara LR, Elias RM, Barreto CR, Silva-Cunha C, Hyane MI, Gonçalves GM, Brum PC, Fujihara C, Zatz R, Pacheco-Silva A, Zamboni DS, Camara NO: Pivotal role of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4, its adaptor molecule MyD88, and inflammasome complex in experimental tubule-interstitial nephritis. PLoS ONE 6: e29004, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Allam R, Lichtnekert J, Moll AG, Taubitz A, Vielhauer V, Anders HJ: Viral RNA and DNA trigger common antiviral responses in mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1986–1996, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Anders HJ, Banas B, Linde Y, Weller L, Cohen CD, Kretzler M, Martin S, Vielhauer V, Schlöndorff D, Gröne HJ: Bacterial CpG-DNA aggravates immune complex glomerulonephritis: Role of TLR9-mediated expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 317–326, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Anders HJ, Vielhauer V, Eis V, Linde Y, Kretzler M, Perez de Lema G, Strutz F, Bauer S, Rutz M, Wagner H, Gröne HJ, Schlöndorff D: Activation of Toll-like receptor-9 induces progression of renal disease in MRL-Fas(lpr) mice. FASEB J 18: 534–536, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Merino A, Nogueras S, García-Maceira T, Rodríguez M, Martin-Malo A, Ramirez R, Carracedo J, Aljama P: Bacterial DNA and endothelial damage in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 3635–3642, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Patole PS, Gröne HJ, Segerer S, Ciubar R, Belemezova E, Henger A, Kretzler M, Schlöndorff D, Anders HJ: Viral double-stranded RNA aggravates lupus nephritis through Toll-like receptor 3 on glomerular mesangial cells and antigen-presenting cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1326–1338, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Patole PS, Pawar RD, Lichtnekert J, Lech M, Kulkarni OP, Ramanjaneyulu A, Segerer S, Anders HJ: Coactivation of Toll-like receptor-3 and -7 in immune complex glomerulonephritis. J Autoimmun 29: 52–59, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ: Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464: 104–107, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Gonçalves RG, Gabrich L, Rosário A, Jr, Takiya CM, Ferreira ML, Chiarini LB, Persechini PM, Coutinho-Silva R, Leite M, Jr: The role of purinergic P2X7 receptors in the inflammation and fibrosis of unilateral ureteral obstruction in mice. Kidney Int 70: 1599–1606, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Ji X, Naito Y, Weng H, Endo K, Ma X, Iwai N: P2X7 deficiency attenuates hypertension and renal injury in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F1207–F1215, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Solini A, Menini S, Rossi C, Ricci C, Santini E, Blasetti Fantauzzi C, Iacobini C, Pugliese G: The purinergic 2X7 receptor participates in renal inflammation and injury induced by high-fat diet: Possible role of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Pathol 231: 342–353, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Wang C, Pan Y, Zhang QY, Wang FM, Kong LD: Quercetin and allopurinol ameliorate kidney injury in STZ-treated rats with regulation of renal NLRP3 inflammasome activation and lipid accumulation. PLoS ONE 7: e38285, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]