Abstract

Resolution in optical nanoscopy depends on the localization uncertainty of single fluorescent labels, the density of labels covering the sample, and the sample’s spatial structure. Currently there is no integral, practical resolution measure that takes all factors into account. Here we introduce such a measure that can be computed directly from the image. We demonstrate its validity and benefits on 2D and 3D localization microscopy images of tubulin and actin filaments. Our approach makes it possible to compare achieved resolutions in images taken with different nanoscopy methods, optimize and rank different emitter localization and labeling strategies, define a stopping criterion for data acquisition, describe image anisotropy and heterogeneity, and, surprisingly, estimate the average number of localizations per emitter. Our findings challenge the current focus on obtaining the best localization precision, but instead show how the best image resolution can be achieved as fast as possible.

The first and foremost law of conventional optical imaging science is that resolution is limited to a value on the order of λ/NA, with λ the wavelength of light and NA the numerical aperture of the imaging lens. Rayleigh and Sparrow captured this law by empirical resolution criteria. These were placed on solid foundations by Abbe and Nyquist, defining resolution as the inverse of the spatial bandwidth of the imaging system. This diffraction limit, however, has been overcome by numerous optical nanoscopy techniques in the last decade, notably STED1, RESOLFT2, the family of localization microscopy techniques such as PALM, STORM, GSDIM, and dSTORM3–6 and statistical methods as BLINK and SOFI7, 8.

These revolutionary developments raise the question: what is resolution in diffraction-unlimited imaging. The resolving power of the instrument is often coupled to the uncertainty of localizing single emitters, that is, point sources. The closely related two-point resolution can be given a precise meaning in the context of localization microscopy9, thus generalizing the Rayleigh criterion of conventional microscopy. These concepts characterize the scale at which an image of a limited number of molecules of interest is resolved when they have all been labeled and successfully imaged. If, however, more or less continuous structures with a very large number of potential labeling sites are imaged, such as actin filaments or organelle membranes, then it is clear that the average density of localized fluorescent labels must also play a role. As early as the first demonstration of localization microscopy for cell imaging3, it was noted that “both parameters - localization precision and the density of rendered molecules - are key to defining performance…”. The effect of labeling density and photoswitching kinetics on resolution has since been investigated experimentally10, 11. Recently an estimation-theoretic resolution concept was presented by Fitzgerald et al.12 that combines both labeling density and localization uncertainty using an a-priori model of the sample.

We conclude from all prior work that neither the average density of localized molecules needed for random Nyquist sampling nor the localization uncertainty alone are suitable measures to assess the resolution. In addition, the resolution depends on a multitude of other factors such as the link between the label and the structure, the underlying spatial structure of the sample itself, and the extensive data processing required to produce a final super-resolution image comprising e.g. single emitter candidate selection and localization algorithms. Only an integral, image-based resolution measure, not depending on any a-priori information, is ultimately suitable to determine what level of detail can be reliably discerned in any given image.

RESULTS

Here, we propose a new image resolution measure, termed Fourier Image REsolution (FIRE), that can be computed directly from experimental data alone. FIRE is centered on the Fourier Ring Correlation (FRC) or equivalently the spectral signal-to-noise-ratio (SSNR), which is in common use in the field of cryo-electron microscopy to assess single particle tomographic reconstructions of macro-molecular complexes13–15. For FIRE we divide the set of single emitter localizations that constitute a super-resolution image into two statistically independent sub-sets, yielding two sub-images f1 (r⃗) and f2 (r⃗), where r⃗ denotes the spatial coordinates. Subsequent statistical correlation of their Fourier transforms f̂1 (q⃗) and f̂2 (q⃗) over the pixels on the perimeter of circles of constant spatial frequency magnitude q = |q⃗| gives the FRC 14:

| (1) |

For low spatial frequencies the FRC curve is close to unity and for high spatial frequencies noise dominates the data and the FRC decays to zero. The image resolution is defined as the inverse of the spatial frequency for which the FRC curve drops below a given threshold. We evaluated different threshold criteria used in the field of electron microscopy13, 16–18 and found that the fixed threshold equal to 1/7 ≈ 0.143 (ref. 18) is most appropriate for localization microscopy images (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Methods, sec. 1). Figure 1a illustrates the FIRE concept and the steps needed to compute it. FIRE describes the length scale below which the image lacks signal content. Details in the image smaller than this value are not resolved. Resolution values as given by FIRE will always be larger than those based on localization uncertainty or labeling density alone (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 1. The FIRE principle and trade-off between localization uncertainty and labeling density.

a, All localizations are divided into two halves, the correlation of their Fourier transforms over the perimeter of circles in Fourier space of radius q is calculated, resulting in an FRC curve indicating the decay of the correlation with spatial frequency. The image resolution is the inverse of the spatial frequency for which the FRC curve drops below the threshold 1/7 ≈ 0.143, e.g. a threshold value at q = 0.04 nm−1 is equivalent to 25 nm resolution b, Simulated localization microscopy image of a line pair with mean labeling density in the area occupied by the lines ρ = 2.5 · 103μm−2 and localization uncertainty σ = 7.6 nm (line distance 70 nm, cosine squared cross-section as defined in Supplementary Note 2). c, Theory (lines) and simulation data (circles) of constant FIRE value (20, 40, . . ., 100 nm) for line pairs as in b as a function of localization uncertainty and labeling density in the area occupied by the lines. Regions of localization uncertainty limited resolution (blue) and labeling density limited resolution (yellow) are separated by the red line ρσ2 = e/6π. d, Localization uncertainty versus image resolution for different fixed total measurement times (1, 5, 10, 20 and 30 min.). Camera frame rates were varied to match the on-times of the emitter. The minima of the curves fall on the red line FIRE = 2πσ that separates the yellow region in which not enough emitters have been localized from the blue region in which the emitters have not been localized precisely enough.

Theoretical considerations and simulations

FIRE allows predictions about the impact of different imaging and sample parameters on the achievable resolution based on the expectation value of the FRC curve, which is given by (Supplementary Fig. 3–4, Supplementary Note 1):

| (2) |

where N is the total number of localized emitters, σ is the average localization uncertainty, and ψ̂ (q⃗) denotes the Fourier spectrum of the spatial distribution of the fluorescent emitters. The parameter Q is a measure for spurious correlations due to e.g. repeated photo-activation of the same emitter. Each emitter contributing to the image is localized once for Q = 0 and in general Q/ (1 − exp(−Q)) times on average, provided the emitter activation follows Poisson statistics. Careful analysis of the spatio-temporal correlations in the image and the emitter activation statistics (including effects of photobleaching) can provide a way to estimate Q and correct for its effect on image resolution, as well as to estimate the number of fluorescent labels contributing to the image, as will be discussed below.

Analytical expressions for FIRE can be derived for particular object types often used in resolution definitions, such as line pairs (Supplementary Note 2). FIRE for an image consisting of two parallel lines with a cosine squared cross-section and mean labeling density ρ in the area occupied by the lines is:

| (3) |

where W(x) is the Lambert W-function or Omega-function, which is defined as the inverse of the function x exp(x) 19. Two regimes can be identified in which either labeling density or localization uncertainty has the most impact on improving resolution. The boundary between these two regimes is found by setting the relative gain in resolution due to a change of either quantity equal to each other. This trade-off occurs at R = 2πσ (Supplementary Note 3), which corresponds to:

| (4) |

Figure 1c shows these two regions; ρσ2 < e/6π is labeling density limited, ρσ2 > e/6π is localization uncertainty limited. The exact boundary between the two regimes depends on the underlying object, so the boundary value for the two-line example serves only as a rule-of-thumb (see Supplementary Note 3). For example, for M parallel lines we obtain a value e/3πM. From this it may be inferred that for any intricate but irregular object structure the trade-off occurs for a value smaller than 0.14.

The same trade-off as above may also manifest itself in the optimization of image resolution given a fixed total acquisition time, as shown in Figure 1d. Suppose that the photon count per localization is improved by increasing the on-times of the emitters while keeping the emitters’ brightness and the number of simultaneously active emitters constant, then this also reduces the total number of labels that can be localized in a given acquisition time. Therefore longer single emitter events yield more accurate localizations but at the expense of a lower recorded emitter density 3, 20. Again, the optimum is R = 2πσ, independent of the object (Supplementary Note 3). Tuning the on-times as described here may be done in the design phase of an experiment by the choice of label or buffer composition.

Resolution build-up during data acquisition and effects of data processing

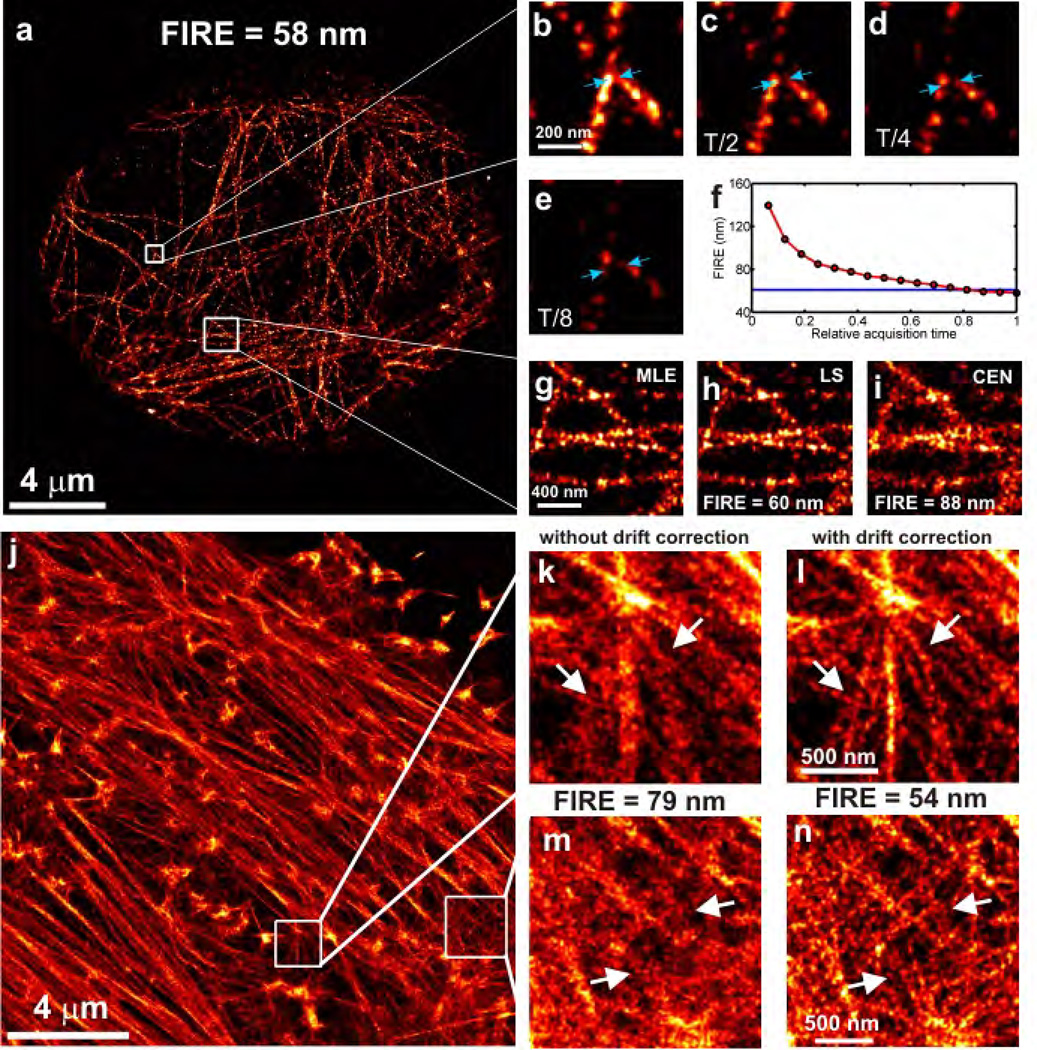

In order to test and evaluate FIRE, we have imaged tubulin networks in fixed HeLa cells labeled with Alexa 647 with localization microscopy (Fig. 2a). The FIRE value improves with acquisition time (Fig. 2b–f), or equivalently with the density of localized labels. The trade-off point between the localization density and localization uncertainty limited regimes lies at R = 2πσ = 61 nm. Therefore the resolution values for Figure 2b–e are labeling density limited and the trade-off point is just crossed at the end of the data acquisition. The combination of current real-time single molecule fitting algorithms21 with continuous monitoring of resolution build-up provides a much needed stopping criterion for localization microscopy data acquisitions. The FIRE concept is also sensitive to differences in localization uncertainty (Fig. 2, g–i). Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE, FIRE = 58±1 nm) is theoretically optimal 22 and slightly better than least squares fitting (LS, FIRE = 60±1 nm) and superior to centroid fitting (CEN, FIRE = 88±2 nm). Since the effect of the parameter Q on the FIRE values for this dataset was found to be negligible, it was not necessary to correct for it.

Figure 2. The effect of density of localizations and data processing on resolution.

a, Localization microscopy image of tubulin labeled with Alexa 647 in a HeLa cell (FIRE = 58±1 nm for the whole image). The image is obtained from 1.4 · 104 frames recorded in 4 min, the localization uncertainty is σ = 9.7 nm after merging nearby localizations in subsequent image frames (Supplementary Methods, sec. 3.3) and the density of localizations is ρ = 6.0 · 102μm−2. b–e, Zoomed insets of two crossing lines constructed from fewer time frames showing poorer resolutions (indicated by the distance between the blue arrows). f, Resolution build-up during the entire data acquisition with FIRE = 2πσ plotted in blue, showing a transition from density limited resolution to precision limited resolution close to the end of the data acquisition. At the end of data acquisition we reach ρσ2 = 0.06 on the order of the rule-of-thumb value 0.14 for the transition point (see Eq.(4)). g–i, Reconstructions by different localization algorithms showing that MLE (g, FIRE = 58±1 nm) and LS (h, FIRE = 60±1 nm) methods outperform CEN (i, FIRE = 88±2 nm). j, Localization microscopy image of actin cytoskeleton (F-actin) of a fixed HeLa cell labeled with Phalloidin coupled to Alexa 647, after correction for sample drift of ~ 70–100 nm during acquisition. The image is obtained from 5.0 · 104 frames recorded in 8 min, the localization uncertainty (after merging nearby localizations in subsequent image frames) is σ = 8.0 nm and the density of localizations is ρ = 8.2 · 103μm−2 (ρσ2 = 0.52, 2πσ = 50 nm). k–n, Zoomed insets of reconstructions before (k, m) and after (l, n) drift correction show that more detail is visible after drift correction, which is reflected by a better FIRE value for the entire image after drift correction (54±1 nm compared to 79±2 nm before drift correction).

Sample drift is a common annoyance in optical nanoscopy as motion has to be limited to a few nanometers over typical acquisition times of many minutes. Figure 2j shows an image of the actin cytoskeleton of a fixed HeLa cell labeled with Phalloidin coupled to Alexa 647, which was analyzed for drift without the use of fiducial markers23. A drift of ~70–100 nm was found with this procedure and corrected for. Computed FIRE values before drift correction (Fig. 2k, m, FIRE = 79±1 nm) are much worse than after drift correction (Fig.2l, n, FIRE = 54±1 nm), in agreement with the apparent detail in the images (arrows in Fig. 2k–m). For this dataset the effect of the parameter Q was also found to be negligible. More experimental data are provided to show the validity of FIRE (Supplementary Fig. 5–7).

Estimation of the number of localizations per emitter

Multiple localizations per emitter due to e.g. repeated photo-activations leads to spurious correlations between the two image halves resulting in overoptimistic FIRE values. This overestimation is particularly problematic for high numbers of localizations per emitter, low localization uncertainties, and low labeling densities (Supplementary Fig. 8–9). The FRC can be corrected for this effect by estimating the spurious correlation parameter Q in Eq. (2). To that end the numerator of the FRC is divided by the weighted average of the function exp (−4π2σ2q2) over the distribution of localization uncertainties. The spurious correlation parameter Q is proportional to the minimum of that curve, which takes the form of a broad plateau if Q ≫ 1 (Supplementary Methods, sec. 1). In order to test this method we have analyzed a two-color image of tubulin labeled with both Alexa 647 and Alexa 75024. Fig. 3a–d show the resulting localization microscopy image (a, b) and the FRC curves without (c) and with (d) correction. The FIRE-values for Alexa 647 and Alexa 750 without correction (25±1 nm and 34±1 nm, respectively) are much lower than the FIRE-value derived from the cross-channel, i.e. when taking the two color images as data halves for the FRC (118±2 nm). This difference is due to spurious correlation effects arising from multiple localizations per emitter, which affect the one color FRC curves but not the cross-channel curve. The FRC curves are much more similar after correction and therefore also the attendant FIRE values (108±1 nm for Alexa 647, 133±2 nm for Alexa 750, 121±2 nm for the cross-channel). The remaining differences in the calculated resolution value for the two channels reflect the differences in labeling density (density of localizations 3.9·103μm−2 for Alexa 647, 1.2·103μm−2 for Alexa 750) and localization uncertainty (9.2 nm and 12 nm, respectively). The estimated Q-values (Q = 10 for Alexa 647, Q = 18 for Alexa 750) agree qualitatively with the values reported earlier25. The values for the localization uncertainty and for the ratio of the Q-parameters are supported by an analysis of bright isolated clusters of localizations in the image. The values for Q are also consistent with the uncorrected FIRE values. It follows from Eq. (2) that FIRE without spurious correlation correction is equal to in the regime where spurious correlations dominate the FRC curve (Supplementary Note 1). Using this formula and the found values for σ and Q we obtain 31 nm for Alexa 647 and 37 nm for Alexa 750, close to the uncorrected FIRE values of 25 nm and 34 nm respectively.

Figure 3. Spurious correlations from two-color localization microscopy image.

a, b, Overview image of a tubulin network (a) labeled with both Alexa 647 (red) and Alexa 750 (green), and inset (b) showing the quality of registration. c, The uncorrected FRC curves for the red and green channel are significantly higher than the cross-channel curve due to spurious correlations from repeated photo-activations of individual emitters, resulting in overly optimistic FIRE values for the red and green channels (25±1 nm and 34±1 nm, respectively, compared to 118±2 nm for the cross-channel). d, FRC curves corrected for spurious correlations are much closer to each other and give rise to similar FIRE values (108±1 nm for Alexa 647, 133±2 nm for Alexa 750, 121±2 nm for the cross-channel). e–g, Scaled FRC numerator curves showing a plateau for intermediate spatial frequencies, which is used to estimate the correction term and the parameter Q that determines the average number of localizations per binding site (Q = 10 for Alexa 647, Q = 18 for Alexa 750, Q = 0.3 for the cross-channel). For this correction (see Supplementary Methods, sec. 1) we used a mean and width of the distribution of localization uncertainties equal to 9.2 and 2.8 nm for Alexa 647, and 12 and 2.0 nm for Alexa 750.

We checked the datasets of Fig. 2a and Fig. 2j for spurious correlations and found Q = 0.28 and Q = 0.33, respectively, leading to corrected FIRE values equal of 62 ± 2 nm and 66 ± 1 nm respectively. This means, that neglecting to correct for spurious correlations gives rise to an underestimation of the FIRE-value of only several nanometers here. These estimated values for Q are smaller than the values for the dataset of Fig. 3 primarily because Q scales with the time of the data acquisition, which is much smaller here (1.4 · 104 frames in 4 min for Fig. 2a and 5.0 · 104 frames in 8 min. for Fig. 2j compared to 1.4 · 105 frames in 39 min. and 3.0 · 104 frames in 25 min. for Alexa 647 and Alexa 750 in Fig. 3). Other reasons may be found in differences in photobleaching behaviour (subpopulation that bleaches after first activation) and preprocessing for candidate selection of single emitter events (false positives). Finally, the labeling density for Fig. 2j is close to 104μm−2, one to two orders of magnitude more than the other datasets. In the limit of high labeling density the effects of spurious correlations are relatively insignificant compared to the intrinsic image correlations (Supplementary Note 1 and 2). We point out that the correction method appears to be quite sensitive to (the distribution of) the localization uncertainty, and to any residual effects of drift, and must therefore be exercised with care.

The estimation of the average number of localizations per emitter from the spurious correlation parameter Q also enables counting of the actual number of fluorescent labels that contribute to the overall image. Our method does not require a model for the correlations in the spatial distribution of the fluorescent labels, unlike methods based on pair correlation functions that have also been used for this purpose26, 27, and no calibration experiment is needed, as opposed to the cluster kymography analysis28. Deviations from Poisson statistics of the emitter activation due to photobleaching may lead to overestimation and in some cases underestimation (for very small Q) of the number of localizations per emitter (Supplementary Note 1). The same caveat applies to the correlation function based apprach26, 27. Control experiments on sparsely distributed labelled antibodies on a glass surface suggest that photobleaching causes the Q-values for the data in Fig. 3 to overestimate the true number of localizations per emitter with a factor 1.5 for Alexa 647 and 1.7 for Alexa 750, even though the Q-parameter was estimated much more accurately (Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Methods, sec. 3). The measured density of localizations, the estimated Q-parameter, and the photobleaching correction factor then finally lead to an estimated labeling density equal to 5.9·102μm−2 for Alexa 647 and 1.1·102μm−2 for Alexa 750.

FIRE in 3D, anisotropic and heterogeneous image content

The FIRE concept can be generalized and extended in a number of ways. The first way targets image anisotropy, which may arise from e.g. line-like features in the image or from differences between the axial and lateral resolving power of the microscope in 3D-imaging29. Anisotropic image resolution can be described similar to FRC by correlating the two data halves in Fourier space over a line in 2D (Fourier Line Correlation, FLC) or plane in 3D (Fourier Plane Correlation, FPC) perpendicular to spatial frequency vectors q⃗. The set of spatial frequencies for which the FLC/FPC is above the threshold are resolved in the image. Fig. 4 shows the FPC for a 3D image of a tubulin network labeled with Alexa 647, using the bifocal method30. The filaments are mostly in the xy-plane oriented along the x-direction (Fig. 4e). Therefore, the FPC is highest in the y-direction, orthogonal to the filaments, and worst in the z-direction, reflecting that the axial localization precision is inferior to the lateral one. Supplementary Figure 11 shows the FLC of (a part of) the dataset of Fig. 2j. The region of resolved spatial frequencies is anisotropic and highest in the direction orthogonal to the filaments, in agreement with expectations. Another way in which the FIRE concept may be generalized targets local variations in the density of the sample’s spatial structure. The local image resolution can be obtained by the FIRE value of overlapping sub-image patches (Supplementary Methods, sec. 3). Supplementary Figure 12 shows an example of such a resolution map for the dataset of Fig. 2a.

Figure 4. 3D-FIRE.

a, Orthogonal slices of the Fourier Plane Correlation (FPC) of a 3D localization microscopy image of a tubulin network. b–d, Cross-sections of the qxqz-plane, the qyqz-plane, and the qxqy-plane of the Fourier Plane Correlation, with added resolution threshold contours FPC = 1/7 (black lines). e, Representation of the 3D tubulin network, with the axial coordinate in false color. The FPC clearly shows the anisotropy of image content resulting from the line-like structure of the filaments (highest image resolution perpendicular to the filaments), as well as from the anisotropy in localization uncertainty (lowest resolution in the axial direction).

DISCUSSION

The FRC concept and FIRE are not only applicable to any form of localization microscopy but can be naturally extended to STED, imaging with an extended diffraction limit such as Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM)31 and to conventional diffraction limited confocal and wide-field imaging. It is not only possible to conceptually extend the FIRE method, but this approach also allows the resolution to be measured directly from the experimental data. This stands in contrast to the recently introduced unified resolution concept of Mukamel et al. 32 which provides a rigorous theoretical framework but does not allow for practical measurement of the resolution. The FIRE number is most easily computed from two images of the same scene that only differ in noise content. For those cases the value depends on the signal-to-noise ratio, the spectral image content, and the (effective) optical transfer function. The width of the effective point spread function replaces the role of the localization uncertainty. In the limit of infinitely high signal-to-noise ratio, the FIRE measure reduces to Abbe’s diffraction limit (for the conventional fluorescence imaging modalities) or to the limit proposed by Hell (for STED33) (Supplementary Note 4). Supplementary Figure 13 shows that the FIRE value matches well with Abbe’s limit in widefield acquisitions of fluorescent beads with a high signal-to-noise ratio. FIRE is also applicable to time lapse recordings in scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in single electron counting mode. Supplementary Figure 14 shows such a resolution build-up over time, as quantified by FIRE. For any extension of the FRC concept and FIRE, care must be taken to prevent dependencies (i.e. spurious correlations) between the images due to e.g. fixed pattern noise or common alignment references. Especially alignment references have been problematic in the past for the application of the FRC concept in the field of single particle electron microscopy34.

In conclusion, we envision that FIRE may be used for characterizing and optimizing fluorescent labeling and data processing strategies in general. Next to the much needed stopping criterion detailed above, FIRE may be used to rate different approaches for enabling faster super-resolution image build-up that deal with high densities of simultaneously active emitters35–37. Access to the number of molecules inside a multi-molecular complex, e.g. the spliceosome or transcription machinery, without making assumptions about their spatial structure adds a new dimension to the application of optical nanoscopy. Most importantly though, a resolution measure as proposed here is indispensable for advancing the blooming field of optical nanoscopy because it provides a quantitative guide for reliable interpretation of data, thus enabling sound biological conclusions.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kees Jalink for encouragement and support, Samantha Schwartz, Fang Huang, Jason Byars and Sheng Liu for assistance with experiments, and Vincent van Ravesteijn and Pieter Kruit for providing SEM data. We further appreciate the thoughtful comments of Ted Young and Lucas van Vliet. R.P.J.N. and D.L.P. are supported by the Dutch Technology Foundation STW, which is part of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), and which is partly funded by the Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation. K.A.L. was supported by National Science Foundation CAREER Award #0954836 and National Institutes of Health grant number P50GM085273.

Footnotes

Author Contributions R.P.J.N., S.S., and B.R. devised the conceptual framework, and derived theoretical results. Simulations were done by R.P.J.N. Experimental datasets were acquired by R.P.J.N. (Fig. 2a–i), D.L.P. (Fig. 2j–n), K.A.L. (Figs. 2 and 4), and M.B. (Fig. 3). Data were analyzed by R.P.J.N.,M.B., S.S. and B.R. D.G. provided research advice. The paper was written by R.P.J.N., D.G., S.S., and B.R.

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests. Software for computing FRC curves and the FIRE number for localization microscopy data is available in the form of an ImageJ plugin and of MATLAB code at www.diplib.org/add-ons and as Supporting Software.

References

- 1.Hell SW, Wichmann J. Breaking the diffraction limit resolution by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion microscopy. Opt. Lett. 1994;19:780–783. doi: 10.1364/ol.19.000780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmann M, Eggeling C, Jakobs S, Hell SW. Breaking the diffraction barrier in fluorescence microscopy at low light intensities by using reversibly photoswitchable proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:17565–17569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506010102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betzig E, et al. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science. 2006;313:1643–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1127344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rust MJ, Bates M, Zhuang X. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) Nat. Meth. 2006;3:793–795. doi: 10.1038/nmeth929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fölling J, et al. Fluorescence nanoscopy by ground-state depletion and single-molecule return. Nat. Meth. 2008;5:943–945. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heilemann M, et al. Subdiffraction-resolution fluorescence imaging with conventional fluorescent probes. Ange. Chemie. 2008;47:6172–6176. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lidke KA, Rieger B, Jovin TM, Heintzmann R. Superresolution by localization of quantum dots using blinking statistics. Opt. Express. 2005;13:7052–7062. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.007052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dertinger T, Colyer R, Iyer G, Weiss S, Enderlein J. Fast, background-free, 3D super-resolution optical fluctuation imaging (SOFI) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:22287–22292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907866106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ram S, Ward ES, Ober RJ. Beyond Rayleighs criterion: A resolution measure with application to single-molecule microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:4457–4462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508047103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van de Linde S, Wolter S, Heilemann M, Sauer M. The effect of photoswitching kinetics and labeling densities on super-resolution fluorescence imaging. J. Biotech. 2010;149:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordes T, et al. Resolving single-molecule assembled patterns with superresolution blink-microscopy. Nano Lett. 2010;10:645–651. doi: 10.1021/nl903730r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzgerald JE, Lu J, Schnitzer MJ. Estimation theoretic measure of resolution for stochastic localization microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:048102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.048102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxton WO, Baumeister W. The correlation averaging of a regularly arranged bacterial cell envelope protein. J. Micros. 1982;127:127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1982.tb00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Heel M. Similarity measures between images. Ultramicros. 1987;21:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unser M, Trus BL, Steven AC. A new resolution criterion based on spectral signal-to-noise ratio. Ultramicros. 1987;23:39–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(87)90225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckmann R, et al. Alignment of conduits for the nascent polypeptide chain in the ribosome-sec61 complex. Science. 1997;278:213–2126. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Böttcher B, Wynne SA, Crowther RA. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 1997;386:88–91. doi: 10.1038/386088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenthal PB, Henderson R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Bio. 2003;333:721–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barry DA, et al. Analytical approximations for real values of the Lambert W-function. Math. Comput. Simul. 2000;53:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Small AR. Theoretical limits on errors and acquisition rates in localizing switchable fluorophores. Biophys. J. 2009;92:L16–L18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolter S, et al. rapidSTORM: accurate, fast open-source software for localization microscopy. Nat. Meth. 2012;9:1040–1041. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith CS, Joseph N, Rieger B, Lidke KA. Fast, single-molecule localization that achieves theoretically minimum uncertainty. Nat. Meth. 2010;7:373–375. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mlodzianoski MJ, et al. Sample drift correction in 3d fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy. Opt. Express. 2011;19:15009–15019. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.015009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bates M, Dempsey GT, Chen KH, Zhuang X. Multicolor super-resolution fluorescence imaging via multi-parameter fluorophore detection. ChemPhysChem. 2012;13:99–107. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dempsey GT, Vaughan JC, Chen KH, Bates M, Zhuang X. Evaluation of fluorophores for optimal performance in localization-based super-resolution imaging. Nat. Meth. 2011;8:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sengupta P, et al. Probing protein heterogeneity in the plasma membrane using PALM and pair correlation analysis. Nat. Meth. 2011;8:969–975. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veatch S, et al. Correlation functions quantify super-resolution images and estimate apparent clustering due to over-counting. Plos ONE. 2012;7:e31457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annibale P, Vanni S, Scarelli M, Rothlisberger U, Radenovic A. Identification of clustering artifacts in photoactivated localization microscopy. Nat. Meth. 2011;8:527–528. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Middendorff C, Egner A, Geisler C, Hell SW, Schönle A. Isotropic 3D nanoscopy based on single emitter switching. Opt. Express. 2008;16:20774–20788. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.020774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toprak E, et al. Defocused orientation and position imaging (DOPI) of myosin V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:6495–6499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507134103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gustafsson MGL. Surpassing the lateral resolution limit by a factor of two using structured illumination microscopy. J. Micros. 2000;198:82–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2000.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukamel E, Schnitzer M. Unifed resolution bounds for conventional and stochastic localization fluorescence microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:168102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.168102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hell SW. Towards fluorescence nanoscopy. Nat. Biotech. 2003;21:1347–1355. doi: 10.1038/nbt895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheres S, Chen S. Prevention of overfitting in cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Meth. 2012;9:853–854. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang F, Schwartz SL, Byars JM, Lidke KA. Simultaneous multiple-emitter fitting for single molecule super-resolution imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2011;2:1377–1393. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holden SJ, Uphoff S, Kapanidis AN. DAOSTORM: an algorithm for high-density super-resolution microscopy. Nat. Meth. 2011;8:279–280. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0411-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu L, Zhang W, Elnatan D, Huang B. Faster STORM using compressed sensing. Nat. Meth. 2012;9:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.