Abstract

Background

Oxidative stress may contribute to heart failure (HF) progression. Inhibiting xanthine oxidase in hyperuricemic HF patients may improve outcomes.

Methods and Results

We randomized 253 patients with symptomatic HF, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40%, and serum uric acid levels ≥9.5 mg/dL to receive allopurinol (target dose, 600 mg daily) or placebo in a double-blind, multicenter trial. The primary composite endpoint at 24 weeks was based on survival, worsening HF, and patient global assessment. Secondary endpoints included change in quality of life, submaximal exercise capacity, and LVEF. Uric acid levels were significantly reduced with allopurinol compared to placebo (treatment difference, −4.2 [−4.9, −3.5] mg/dL and −3.5 [−4.2, −2.7] mg/dL at 12 and 24 weeks, respectively, both P<0.0001). At 24 weeks, there was no significant difference in clinical status between the allopurinol- and placebo-treated patients (worsened 45% vs. 46%, unchanged 42% vs. 34%, improved 13% vs. 19%, respectively; P=0.68). At 12 and 24 weeks, there was no significant difference in change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire scores or 6-minute walk distances between the 2 groups. At 24 weeks, LVEF did not change in either group or between groups. Rash occurred more frequently with allopurinol (10% vs. 2%, P=0.01), but there was no difference in serious adverse event rates between the groups (20% vs. 15%, P=0.36).

Conclusions

In high-risk HF patients with reduced ejection fraction and elevated uric acid levels, xanthine oxidase inhibition with allopurinol failed to improve clinical status, exercise capacity, quality of life, or LVEF at 24 weeks.

Keywords: heart failure, xanthine oxidase, allopurinol, clinical trial

Despite guideline-recommended therapy for patients with heart failure (HF), morbidity and mortality rates remain unacceptably high.1 Given the public health burden of HF, there is a clear need for improved therapies. A growing body of evidence suggests that increased oxidative stress contributes to ventricular and vascular remodeling and disease progression in HF.2 Xanthine oxidase (XO) is a potential source of oxidative stress, and may be an important target for therapy.3 During purine metabolism, increased XO activity leads to the production of superoxide and uric acid (UA). Significant hyperuricemia is present in about 25% of patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction,4, 5 and is associated with worsening symptoms, exercise intolerance and reduced survival.6–8 Serum UA levels are included in HF risk scores,8, 9 and may help to select high-risk patients for XO inhibition.

Allopurinol is a potent inhibitor of XO that may reverse several pathophysiological processes in HF, including decreased calcium sensitivity, mechanoenergetic uncoupling, increased anaerobic metabolism, and energy depletion.10 Studies in animals and humans with HF have shown that allopurinol can increase myocardial efficiency and reduce oxygen consumption.11, 12 Magnetic resonance spectroscopy has demonstrated that allopurinol increases myocardial high-energy phosphates and adenosine triphosphate flux, thereby improving mechanoenergetic coupling.13 Impaired endothelial function improves in a dose-dependent fashion with chronic XO inhibition in HF,14, 15 and observational studies in HF patients with gout suggest that treatment with allopurinol is associated with improved survival.16–18 Notably, allopurinol use is treated as a marker of improved survival in the Seattle Heart Failure Model.8

Hare et al.19 randomized 405 patients with moderate to severe HF and reduced ejection fraction to 6 months of treatment with oxypurinol (the active metabolite of allopurinol) or placebo. Although oxypurinol had no clinical benefit in the overall study population, a sub-group of patients with hyperuricemia (UA level ≥9.5 mg/dL) responded favorably with improved clinical status and trends towards decreased all-cause and cardiovascular death. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that in patients with symptomatic HF and reduced LVEF, who have elevated serum UA levels, treatment with high-dose allopurinol for 24 weeks would improve a composite clinical outcome of survival, worsening HF and patient global assessment.

Methods

Study oversight

Investigators from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)–sponsored Heart Failure Clinical Research Network conceived, designed, and conducted the Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition for Hyperuricemic Heart Failure Patients (EXACT-HF) trial. The study protocol was approved by an NHLBI-appointed protocol review committee, an independent data and safety monitoring board, and the institutional review board at each participating site. The Duke Clinical Research Institute served as the data-coordinating center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study design

Details of the study design, patient population, endpoints and statistical considerations have been published.20 EXACT-HF was a multi-center, 1:1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 24-week trial of allopurinol in patients with symptomatic HF due to LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF ≤40%) and elevated serum UA levels (≥9.5 mg/dL). Patients were required to have at least 1 additional high-risk marker, including an acute HF event (hospitalization or emergency room visit) within 12 months,21 severe LV dysfunction (LVEF ≤25%), or an elevated natriuretic peptide level (B-type natriuretic peptide [BNP] >250 pg/ml or N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-pro-BNP] >1500 pg/ml).22 Patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <20 ml/min were excluded.

Study drug, randomization and blinding

Active therapy in EXACT-HF consisted of allopurinol (target dose, 600 mg daily), with dose adjustment for renal function (Supplemental Table 1).20, 23 Study drug was given for 24 weeks starting with 300 mg by mouth once daily for 1 week, and if tolerated, increased to 600 mg daily. Patients unable to tolerate 600 mg were maintained on 300 mg. Using an automated system, patients were randomized to treatment using a permuted block randomization scheme stratified by clinical site. Study drug or matching placebo capsules were started within 12 hours of completing the baseline visit. Investigators were requested not to measure serum UA levels during the study.

Concomitant medications and gout

To be eligible to participate, patients had to be receiving a stable HF regimen for at least 2 weeks (3 months for beta-blockers) prior to randomization. Intermittent use of supplemental diuretics was permitted. Patients with a history of gout could be enrolled as long as they were not currently being treated with, and unlikely to require, allopurinol during the study. If a patient was started on open-label allopurinol for gout, study drug was permanently discontinued, but visits continued through 24 weeks.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was a composite clinical endpoint (CCE) that classified a subject’s clinical status as improved, worsened, or unchanged at 24 weeks, as previously described.20, 24 This classification follows sequential rules based on: death; hospitalization, emergency room visit or emergent clinic visit for worsening HF; medication change for worsening HF (e.g., addition of a new drug class or an increase in diuretic dose by at least 50% for more than 1 week); and Patient Global Assessment using a 7-point scale25 (Supplemental Table 2). Secondary endpoints at 12 and 24 weeks included changes in quality of life assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)26 and submaximal exercise capacity assessed by 6-minute walk test (6MWT).27 Additional endpoints included echocardiographic measures of LV remodeling including LV volumes, mass and ejection fraction measured in a core laboratory (Mayo Clinic), biomarkers including UA, NT-pro-BNP, cystatin C, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) measured in a core laboratory (University of Vermont), and time to first HF hospitalization (as determined by the investigator) and time to all-cause death or hospitalization. MPO was measured using a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay (Quantikine Human Myeloperoxidase Immunoassay; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), with a detection range of 0.15–10 ng/mL and expected normal serum levels of 21–229 ng/mL. Samples were diluted to achieve values within the standard curve of the assay. Inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation range from 1.5–2.6% and 8.2–10.8%, respectively.

Statistical analysis and power calculation

All analyses were conducted using the intention-to-treat principle and included all randomized patients (Figure 1). Analysis of the primary CCE used the 1 degree-of-freedom Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel row mean score test with modified ridit scores to compare the distributions. Based on prior data,19 we assumed that the placebo arm would have the following approximate response rates for the primary endpoint: 33% improved, 42% unchanged and 25% worsened. We hypothesized that the outcome of the allopurinol arm would be superior, with response rates of approximately 52% improved, 37% unchanged, and 11% worsened. Based on a simulation using 2,000 data sets, we estimated that a sample size of 250 patients would provide 83% power to detect a statistically significant difference using the row mean score statistic with the assumptions above. The 2-sided Type I error rate was set at 0.05. For the primary endpoint, there were no missing data. A pre-specified analysis of the primary CCE stratified by baseline serum creatinine level (≤2 mg/dL vs. >2 to ≤3 mg/dL) was also performed.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram.

Changes from baseline in KCCQ scores, 6MWT distances, echocardiographic measures, and biomarkers between the 2 treatment groups were assessed at 12 and 24 weeks with adjustment for the baseline value using an analysis of covariance approach. Missing values were handled using multiple imputation for all endpoints except echocardiographic measures. For the KCCQ overall summary score (9% missing data at 24 weeks), a total of 100 imputed data sets were used. The imputation model includes covariates for assigned treatment, renal function at baseline, age, gender and non-missing values for each of the KCCQ summary scores across all visits where KCCQ was completed. For the 6MWT (20% missing data at 24 weeks), a similar imputation approach was used and included adjustments for non-missing walk distances at each time period. Cumulative event rates for death and hospitalization were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.28 For binary outcomes, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained from logistic regression models. Hazard ratios (HR), 95% CI, and P-values for the comparison of the 2 treatment groups were determined with the use of the Cox regression model.29 A 2-sided alpha level of 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All data analyses were conducted with SAS software, version 9.2 or higher.

Results

Patients

253 patients were enrolled between May 2010 and June 2013 at 38 sites in the United States and Canada. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the two treatment groups were similar (Table 1). The median (25th, 75th percentile) age of the study population was 63 (53, 72) years and median LVEF was 25% (19, 33). 82% were men and 29% were black. Patients had mild-moderate symptoms of chronic HF (median duration 5.2 [1.9, 10.1] years). Frequent co-morbidities included diabetes mellitus 55%, hypertension 78%, and atrial fibrillation or flutter 49%. Hospitalization for HF in the past year was seen in 57%. Median UA level for the entire cohort was 11.1 (10.1, 12.1) mg/dL, and 23% of patients had a history of gout. Most patients were receiving guideline-recommended pharmacologic and device-based therapies, and were clinically stable (absence of rales 95%, trace or no edema 86%, jugular venous pressure <8 cm 71%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients

| Characteristic | Allopurinol (N=128) | Placebo (N=125) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (Q1-Q3), yr | 63 (54, 74) | 63 (52, 71) |

| Male sex, N (%) | 110 (86) | 98 (78) |

| White race, N (%) | 91 (71) | 78 (62) |

| Duration of heart failure, median (Q1–Q3), yr | 5.1 (2.1, 9.9) | 5.5 (1.9, 10.5) |

| One or more heart failure hospitalizations within past year, N (%) | 74 (58) | 70 (56) |

| NYHA functional class, N (%) | ||

| II | 59 (46) | 61 (49) |

| III | 67 (52) | 61 (49) |

| IV | 2 (2) | 3 (2) |

| LV ejection fraction,† % | 25.6 ± 8.6 | 23.4 ± 7.7* |

| History of moderate or severe MR, N (%) | 57 (45) | 58 (46) |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy, N (%) | 71 (55) | 64 (51) |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 73 (57) | 65 (52) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 99 (77) | 99 (79) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter, N (%) | 67 (52) | 57 (46) |

| Gout, N (%) | 26 (20) | 31 (25) |

| Medications, N (%) | ||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 107 (84) | 107 (86) |

| Beta-blocker | 123 (96) | 118 (94) |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 70 (55) | 63 (50) |

| Digoxin | 50 (39) | 58 (46) |

| Hydralazine | 27 (21) | 21 (17) |

| Nitrates | 38 (30) | 41 (33) |

| Amiodarone | 16 (13) | 30 (24)* |

| Furosemide-equivalent dose, median (Q1–Q3), mg/day | 120 (80, 160) | 120 (80, 160) |

| Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, N (%) | 86 (67) | 86 (69) |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy, N (%) | 40 (47) | 34 (40) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 111 ± 17 | 109 ± 15 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 73 ± 12 | 74 ± 13 |

| Weight, lbs | 213 ± 54 | 217 ± 60 |

| Body-mass index, kg/m2 | 32.0 ± 7.8 | 32.6 ± 8.4 |

| Screening laboratories | ||

| Sodium, mEq/L | 138 ± 3 | 138 ± 4 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 36 ± 19 | 35 ± 18 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.56 ± 0.45 | 1.50 ± 0.46 |

| Hematocrit, % | 38.0 ± 4.9 | 39.4 ± 4.6 |

| Core biomarker laboratories, median (Q1–Q3) | ||

| Cystatin C, mg/L | 1.44 (1.11, 1.83) | 1.34 (1.00, 1.73) |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 11.0 (10.2, 12.2) | 11.1 (10.0, 12.1) |

| NT-pro-BNP, pg/mL | 2708 (1116, 4752) | 2283 (1112, 3977) |

| Myeloperoxidase, mg/mL | 32.9 (21.8, 57.9) | 30.0 (22.8, 51.3) |

Plus-minus values are means ± SD.

All P-values are greater than 0.05 for comparisons of baseline characteristics between the groups, with the exceptions of ejection fraction (P=0.030) and amiodarone (P=0.017).

Obtained at or within 4 weeks of screening.

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; LV, left ventricular; MR, mitral regurgitation; NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; Q1, 25th percentile; Q3, 75th percentile.

Study drug administration

All patients, except for 1 in the placebo group, were initiated on study drug (Figure 1), and there were no differences between the 2 treatment groups in median dose achieved (300 [0, 600] mg in both groups) or rate of permanent study drug discontinuation (allopurinol 34%, placebo 28%). For patients with a baseline serum creatinine level ≤2 mg/dL, the maximum target dose of 600 mg was achieved in 85% of the allopurinol group and 83% of the placebo group. For patients with a baseline serum creatinine level >2 to ≤3 mg/dL, the maximum target dose of 300 mg was achieved in 65% and 75%, respectively. For patients who permanently discontinued study drug, the median duration of treatment was 7.2 (2.6, 18.1) weeks. The final dose that patients were taking in the 2 treatment groups, stratified by baseline renal function, is provided in Supplemental Table 3.

Primary endpoint

At 24 weeks, there was no significant difference in the primary CCE between the allopurinol and placebo-treated patients (worsened 45% vs. 46%, unchanged 42% vs. 34%, improved 13% vs. 19%, respectively; P=0.68) (Figure 2A). A pre-specified analysis of the primary CCE stratified by baseline serum creatinine level (≤2 mg/dL [N=217] vs. >2 to ≤3 mg/dL [N=36]) also showed no significant differences between the 2 groups (P=0.73 and P=1.00, respectively). Finally, a “per protocol” analysis that included only patients that were still taking study drug at the end of the study (or at the time of death) showed no difference in the primary CCE between groups (P=0.27).

Figure 2.

Primary composite clinical endpoint (A) and changes in uric acid levels at 12 and 24 weeks (B). P-value in figure 2A is based on the 1 degree-of-freedom Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Statistic using Modified Ridit Scores. P-values in figure 2B are for the comparison of allopurinol week 12 or week 24 change from baseline vs. placebo based on analysis of covariance models using the 100 multiple imputation datasets.

Secondary endpoints

At 12 and 24 weeks, there was no significant difference in changes in KCCQ overall summary score or 6MWT distance between the allopurinol and placebo-treated patients (Table 2, Figure 3). Sensitivity analyses using observed data and worst-rank score analysis did not alter the results. There was little change in these endpoints over the study period: KCCQ median summary score, 60.7 [39.1, 74.5], 63.8 [45.8, 76.6], and 63.3 (44.5, 77.9], and 6MWT median distance, 285 [189, 373], 284 [201, 383], and 308 [226, 373] meters at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks, respectively.

Table 2.

Changes in Quality of Life, Sub-Maximal Exercise Capacity, and Echocardiographic Measures

| Allopurinol (N=128) | Placebo (N=125) | Treatment Differences (95% CI) and P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (overall summary score) | |||

| Baseline | 60.7 (42.3, 74.5) | 59.9 (37.2, 74.0) | |

| Week 12 | 65.9 (48.4, 77.6) | 62.6 (44.2, 73.0) | |

| Week-12 change | 3.1 (−4.7, 15.1) | 1.0 (−8.9, 10.9) | 1.7 (−2.3, 5.7) 0.41 |

| Week 24 | 61.5 (41.2, 76.0) | 65.6 (45.8, 80.5) | |

| Week-24 change | 0.0 (−10.0, 12.5) | 0.8 (−6.2, 14.1) | −3.2 (−7.8, 1.3) 0.16 |

| 6-Minute Walk Test (meters) | |||

| Baseline | 272 (192, 369) | 290 (182, 378) | |

| Week 12 | 278 (195, 384) | 290 (220, 375) | |

| Week-12 change | 6 (−30, 52) | 13 (−18, 58) | −3 (−23, 17) 0.75 |

| Week 24 | 300 (215, 374) | 313 (244, 365) | |

| Week-24 change | 19 (−38, 71) | 24 (−32, 81) | −5 (−26, 16) 0.64 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (ml/m2) | |||

| Baseline | 129.7 (97.4, 145.4) | 122.3 (100.7, 165.1) | |

| Week 24 | 122.1 (101.4, 142.4) | 116.2 (94.7, 169.7) | |

| Week-24 change | −2.0 (−20.2, 13.3) | 1.0 (−18.1, 20.1) | −3.4 (−14.8, 8.0) 0.56 |

| Left ventricular end-systolic volume index (ml/m2) | |||

| Baseline | 98.3 (70.9, 112.1) | 90.7 (70.0, 121.5) | |

| Week 24 | 88.6 (69.7, 108.7) | 82.7 (68.7, 134.7) | |

| Week-24 change | 1.5 (−12.6, 10.5) | −1.9 (−13.3, 13.2) | −0.8 (−10.5, 8.9) 0.87 |

| Left ventricular mass index (gm/m2) | |||

| Baseline | 116.3 (93.2, 144.9) | 119.6 (98.4, 150.8) | |

| Week 24 | 106.8 (88.6, 140.3) | 116.6 (100.4, 149.4) | |

| Week-24 change | −2.7 (−26.2, 16.2) | −1.0 (−17.2, 15.1) | −4.9 (−15.4, 5.7) 0.36 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | |||

| Baseline | 27.0 (20.0, 35.0) | 25.0 (19.0, 33.0) | |

| Week 24 | 28.0 (23.0, 35.0) | 28.0 (20.0, 34.0) | |

| Week-24 change | 0.0 (−5.0, 7.0) | 0.0 (−7.0, 6.0) | 0.4 (−2.0, 2.8) 0.74 |

Data in columns 2 and 3 are presented as median (25th, 75th percentiles). Treatment difference is defined as allopurinol-placebo and was estimated using an analysis of covariance on the 100 multiple imputation datasets. CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Secondary Endpoints: Changes in quality of life using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary score (A) and sub-maximal exercise capacity using the 6-minute walk test (B) at 12 and 24 weeks. P-values are for the comparison of allopurinol week 12 or week 24 change from baseline vs. placebo based on analysis of covariance models using the 100 multiple imputation datasets.

Echocardiographic measures

At 24 weeks, there was no significant difference in changes in LV volumes, mass or ejection fraction between the allopurinol and placebo-treated patients (Table 2). For the entire cohort, there was little change in these measures over the study period (e.g., LVEF median, 26 [20, 33] % and 28 [21, 35] % at baseline and 24 weeks, respectively).

Biomarkers

Serum UA levels decreased significantly with allopurinol compared to placebo (Figure 2B, Table 3). Treatment differences (95% CI) were −4.2 (−4.9, −3.5) mg/dL and −3.5 (−4.2, −2.7) mg/dL at 12 and 24 weeks, respectively (both P<0.0001). At 24 weeks, 48% of the allopurinol-treated patients had serum UA levels <6 mg/dL compared to only 5% in the placebo group. With the exception of cystatin C at 12 weeks, there were no significant treatment differences in other core biomarkers between the 2 groups (Table 3). There was also no difference in change in other markers of renal function (serum creatinine, eGFR) measured in local laboratories between the treatment groups (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 3.

Changes in Core Biomarker Laboratories

| Allopurinol (N=128) | Placebo (N=125) | Treatment Differences (95% CI) and P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cystatin C (mg/L) | |||

| Baseline | 1.45 (1.11, 1.83) | 1.34 (1.00, 1.73) | |

| Week 12 | 1.54 (1.12, 2.06) | 1.32 (1.07, 1.72) | |

| Week-12 change | 0.08 (−0.06, 0.27) | −0.01 (−0.14, 0.13) | 0.15 (0.07, 0.24) 0.0004 |

| Week 24 | 1.40 (1.06, 2.05) | 1.34 (1.05, 1.77) | |

| Week-24 change | 0.00 (−0.13, 0.18) | 0.02 (−0.10, 0.18) | 0.03 (−0.05, 0.12) 0.43 |

| NT-pro-BNP (pg/mL) | |||

| Baseline | 2723 (1130, 4772) | 2333 (1112, 3998) | |

| Week 12 | 2571 (932, 5199) | 2023 (943, 4253) | |

| Week-12 change | −184 (−905, 600) | −36 (−799, 1027) | −481 (−1280, 318) 0.24 |

| Week 24 | 2361 (943, 5448) | 2260 (1029, 5028) | |

| Week-24 change | −35 (−788, 866) | −23 (−849, 1536) | −95 (−1428, 1238) 0.89 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 11.0 (10.2, 12.2) | 11.1 (10.0, 12.2) | |

| Week 12 | 6.0 (3.8, 9.5) | 10.5 (9.4, 12.4) | |

| Week-12 change | −5.0 (−7.0, −2.2) | −0.2 (−1.5, 0.8) | −4.2 (−4.9, −3.5) <0.0001 |

| Week 24 | 6.7 (4.1, 9.8) | 10.6 (9.0, 12.0) | |

| Week-24 change | −4.8 (−6.8, −1.8) | −0.5 (−2.1, 0.9) | −3.5 (−4.2, −2.7) <0.0001 |

| Myeloperoxidase (ng/mL) | |||

| Baseline | 33.2 (21.9, 72.2) | 30.7 (22.9, 53.9) | |

| Week 24 | 37.2 (24.3, 101.0) | 36.7 (23.8, 75.4) | |

| Week-24 change | 0.4 (−16.3, 38.7) | 0.9 (−9.8, 22.4) | 11.1 (−22.7, 45.0) 0.52 |

Data in columns 2 and 3 are presented as median (25th and 75th percentiles). Treatment difference is defined as allopurinol-placebo and was estimated using an analysis of covariance on the 100 multiple imputation datasets. CI, confidence interval; NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Clinical outcomes

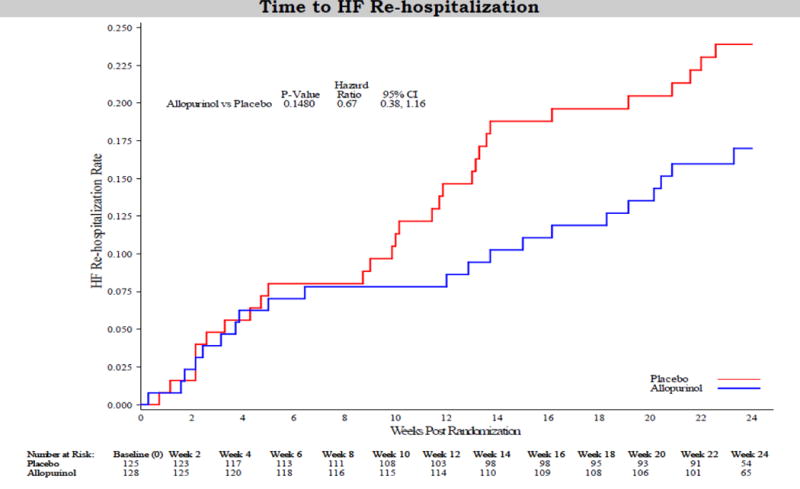

There was no difference between the treatment groups in the proportion of patients who died (6%), were hospitalized for any cause (38%) or had an unscheduled outpatient visit during the study (Table 4). The mean [95% CI] number of hospitalizations (allopurinol 0.57 [0.39, 0.76] vs. placebo 0.64 [0.46, 0.83], P=0.61) and hospital days (allopurinol 4.3 [2.7, 5.9] vs. placebo 6.1 [3.7, 8.6], P=0.22) did not differ significantly between the 2 groups. Medication change for worsening HF occurred in 30% of the allopurinol group and 38% of the placebo group (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.43–1.23, P=0.23). At 24 weeks, 21% of the allopurinol-treated patients and 34% of the placebo group were moderately or markedly better on the Patient Global Assessment tool, but the overall treatment difference was not significant. While there was no difference in the risk of death or hospitalization at 24 weeks between the 2 treatment groups (Figure 4A), HF hospitalization (Figure 4B) tended to be reduced in the allopurinol group (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.38–1.16, P=0.15).

Table 4.

Clinical Events

| Event | Allopurinol (N=128) | Placebo (N=125) |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 8 (6) | 7 (6) |

| Cardiovascular death | 5 (4) | 7 (6) |

| Unscheduled outpatient visit | 39 (30) | 38 (30) |

| All-cause hospitalization | 47 (37) | 48 (38) |

| Cardiovascular hospitalization | 30 (23) | 37 (30) |

| HF hospitalization | 22 (17) | 30 (24) |

Data are presented as N (%). All P-values are greater than 0.05 for comparisons between the groups. HF, heart failure.

Figure 4.

Risk of death or all-cause hospitalization (A) or heart failure hospitalization (B) using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Safety

Overall, study treatment was well tolerated (Table 5). There were fewer reports of gout in the allopurinol group (7% vs. 11% placebo), but this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.23). Rash occurred more frequently in the allopurinol group (10% vs. 2% placebo, P=0.01), while vascular events occurred more frequently in the placebo group (6% vs. 2% allopurinol, P=0.04). There was no difference in the overall rate of adverse events (63% vs. 58%; P=0.51) or serious adverse events (20% vs. 15%; P=0.36) between the allopurinol and placebo groups, respectively.

Table 5.

Selected Adverse Events by Body System

| Adverse Event | Allopurinol (N=128) | Placebo (N=125) |

|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 80 (63) | 73 (58) |

| Any serious adverse event | 25 (20) | 19 (15) |

| Blood and lymphatic | 4 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Cardiac | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Endocrine | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal | 19 (15) | 14 (11) |

| General† | 10 (8) | 4 (3) |

| Infection | 24 (19) | 16 (13) |

| Metabolism and nutrition | 24 (19) | 19 (15) |

| Gout | 9 (7) | 14 (11) |

| Musculoskeletal | 19 (15) | 12 (10) |

| Neoplasm | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Nervous system | 4 (3) | 5 (4) |

| Renal and urinary | 1 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Respiratory | 8 (6) | 8 (6) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | 19 (15) | 7 (6)* |

| Rash | 13 (10) | 3 (2)* |

| Vascular | 2 (2) | 8 (6)* |

Data are presented as N (%).

All P-values are greater than 0.05 for comparisons between the groups, with the exception of skin (P=0.02), rash (P=0.01), and vascular (P=0.04).

Includes fatigue, gait disturbance, malaise, non-cardiac chest pain, and edema.

Discussion

A large body of experimental and clinical data suggests that oxidative stress contributes to ventricular and vascular remodeling and disease progression in HF. Xanthine oxidase is a potent source of oxidative stress, and therefore an obvious target for therapy. Accordingly, we studied a high-risk HF population with reduced EF and elevated serum UA levels. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that XO inhibition with high-dose allopurinol had no detectable benefits on clinical status, exercise capacity, quality of life, or LV structure and function.

Prior clinical studies show acute and chronic benefits of allopurinol in HF,12–15, 30 and epidemiologic data suggests an association between allopurinol use and improved outcomes in HF patients with gout.18 Prior mechanistic studies in HF have shown that allopurinol improved coronary flow reserve, mechanoenergetic coupling,12 myocardial adenosine triphosphate flux,13 and vascular endothelial function.15 We did not assess these physiological endpoints, and they may be poor surrogates for the clinical endpoints that we studied. However, enhanced endothelium-dependent vasodilation might be expected to improve exercise capacity, and direct myocardial and coronary vascular effects should improve LV function, neither of which we observed. The Efficacy and Safety Study of Oxypurinol Added to Standard Therapy in Patients with New York Heart Association Class III–IV Congestive Heart Failure (OPT-CHF) showed no clinical benefit of oxypurinol on an unselected cohort of HF patients with reduced ejection fraction,19 but a post-hoc analysis of hyperuricemic patients suggested a possible benefit with oxypurinol in this group. Post-hoc, sub-group analyses, however, are hypothesis generating, and the results of the current study underscore the importance of prospective, randomized clinical trials to test such hypotheses.

Clinical trials are also inherently dependent on the study population enrolled. We aimed to enroll a group of high-risk patients with stable, chronic HF who were receiving excellent, guideline-recommended therapy.31 Patients had symptoms of HF for an average of 5 years and over half had been hospitalized for HF within the past year. In addition, they had multiple co-morbidities, including diabetes and chronic kidney disease, and other high-risk features. Baseline quality of life scores and sub-maximal exercise capacity demonstrated significant impairment in HF status, similar to or worse than other recent studies.32–34 Not surprisingly, the cumulative event rates in our study were high, with a ~40% rate of death or all-cause hospitalization at 6 months. Importantly, our patients were adherent to study drug and follow-up, and all patients were included in the final analysis.

The target dose of allopurinol chosen in EXACT-HF was more than 6 times the bioequivalent dose of oxypurinol used in the OPT-CHF study,19 with an expected 2-fold or more greater effect on UA lowering.35 Prior data by George et al.15 demonstrated a dose-dependent effect of allopurinol on UA-lowering and endothelium-dependent vasodilation in chronic HF. On average, we observed a 45% reduction in UA levels in the active treatment arm by 12 weeks, and this effect was maintained at 24 weeks. However, we observed no change in myeloperoxidase levels raising the possibility that non-XO pathways of oxidative stress were activated and may have undermined the impact of our trial intervention.3 Alternatively, other mechanisms that contribute to hyperuricemia in HF (e.g., activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines) may have been unaffected by XO inhibition. Nitrates are beneficial in HF and may potentiate the benefit of XO inhibition.36 However, an exploratory analysis showed no difference between the primary and secondary endpoints in patients (N=79) who were taking nitrates at the time of randomization (Supplemental Table 5).

Our study duration may not have been long enough to observe the benefits of XO inhibition. Notably, there was a trend towards reduced HF hospitalizations at 24 weeks, with a separation of the Kaplan-Meier curves beginning at approximately 8 weeks (Figure 4B). We cannot exclude the possibility that a longer study of high-dose allopurinol in a more homogeneous group of high-risk patients would have demonstrated significant reductions in HF morbidity and mortality. Underpowering of the primary composite endpoint is possible given the modest sample size, while the possibility of a type II error cannot be ruled out. Our study groups were well matched at baseline, except for a slightly higher LVEF in the allopurinol group (25.6% vs. 23.4%), which could have biased results in favor of treatment.

With increasing recognition that nitroso-redox imbalance can affect cardiac structure and function, there may still be a role for XO inhibition in other cardiovascular disease states, including ischemic and hypertensive heart disease37 and diabetic cardiomyopathy.38 These studies suggest that reducing XO activity underlies the benefit of allopurinol. However, while decreased markers of oxidative stress have been demonstrated, these changes have not uniformly correlated with structural and functional improvements. More work is needed to understand the complex pathobiology underlying increased XO activity and the modifiable pathways of oxidative stress.39 Our data confirm that allopurinol at doses up to 600 mg daily is safe and well tolerated in patients with HF even with accompanying renal dysfunction. While cystatin C levels were significantly higher in the allopurinol group at 12 weeks, there was no difference at 24 weeks (and other markers of renal function did not differ between the treatment groups). In a single-center study of patients with gout and renal dysfunction, allopurinol use was associated with higher cystatin C levels.40 It is speculated that cystatin C may be a marker of inflammation in addition to renal function, but this requires further study. While rash occurred in 10% of allopurinol-treated patients, there were no reports of the allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal event,41 and no cases of agranulocytosis or irreversible hepatotoxicity.

Conclusions

Despite accumulating evidence of the potential efficacy and safety of XO inhibition in cardiovascular disease states in general and HF in particular, we found no clinical benefit of high-dose allopurinol in patients with HF, reduced ejection fraction and elevated UA levels at 24 weeks. For patients at high risk of HF events, alternative therapies are needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: NHLBI (coordinating center: U10HL084904; regional clinical centers: U01HL084861, U10HL110312, U109HL110337, U01HL084889, U01HL084890, U01HL084891, U10HL110342, U10HL110262, U01HL084931, U10HL110297, U10HL110302, U10 HL110309, U10HL110336, U10HL110338); The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000454, UL1TR000439); and The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (8 U54 MD007588).

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration Information: www.clinicaltrials.gov. Identifier: NCT00987415.

Disclosures: WHWT receives research support from NIH. GMF receives research support from NIH, Amgen, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics and Otsuka, and consulting fees from Amgen, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, Otsuka, Trevena, Singulex, Medtronic and Celladon. KBM reports advisory committee membership for Novo Nordisk and AstraZeneca, and research support from Juventis Therapuetics, Celladon, Thoratec, Innolign Biomedical, LLC and NIH (HL105993, HL110338, HL113777). MAK receives research support or consultant fees from Merck, Otsuka, Novartis, Amgen, and Johnson & Johnson. AFH receives research support from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, and consulting fees from Amgen and Novartis. The remaining authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for medicare beneficiaries, 1998–2008. JAMA. 2011;306:1669–1678. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2181–2190. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karantalis V, Schulman IH, Hare JM. Nitroso-redox imbalance affects cardiac structure and function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:933–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anker SD, Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, Sharma R, Francis D, Knosalla C, Davos CH, Cicoira M, Shamim W, Kemp M, Segal R, Osterziel KJ, Leyva F, Hetzer R, Ponikowski P, Coats AJ. Uric acid and survival in chronic heart failure: Validation and application in metabolic, functional, and hemodynamic staging. Circulation. 2003;107:1991–1997. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065637.10517.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kittleson MM, St John ME, Bead V, Champion HC, Kasper EK, Russell SD, Wittstein IS, Hare JM. Increased levels of uric acid predict haemodynamic compromise in patients with heart failure independently of b-type natriuretic peptide levels. Heart. 2007;93:365–367. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.090845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogino K, Kato M, Furuse Y, Kinugasa Y, Ishida K, Osaki S, Kinugawa T, Igawa O, Hisatome I, Shigemasa C, Anker SD, Doehner W. Uric acid-lowering treatment with benzbromarone in patients with heart failure: A double-blind placebo-controlled crossover preliminary study. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:73–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.868604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leyva F, Anker S, Swan JW, Godsland IF, Wingrove CS, Chua TP, Stevenson JC, Coats AJ. Serum uric acid as an index of impaired oxidative metabolism in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:858–865. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, Anand I, Maggioni A, Burton P, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Mann DL, Packer M. The seattle heart failure model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ky B, French B, Levy WC, Sweitzer NK, Fang JC, Wu AH, Goldberg LR, Jessup M, Cappola TP. Multiple biomarkers for risk prediction in chronic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:183–190. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.965020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy RM, Dutka TL, Lamb GD. Hydroxyl radical and glutathione interactions alter calcium sensitivity and maximum force of the contractile apparatus in rat skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2008;586:2203–2216. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekelund UE, Harrison RW, Shokek O, Thakkar RN, Tunin RS, Senzaki H, Kass DA, Marban E, Hare JM. Intravenous allopurinol decreases myocardial oxygen consumption and increases mechanical efficiency in dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circ Res. 1999;85:437–445. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cappola TP, Kass DA, Nelson GS, Berger RD, Rosas GO, Kobeissi ZA, Marban E, Hare JM. Allopurinol improves myocardial efficiency in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;104:2407–2411. doi: 10.1161/hc4501.098928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch GA, Bottomley PA, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG. Allopurinol acutely increases adenosine triphospate energy delivery in failing human hearts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:802–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farquharson CA, Butler R, Hill A, Belch JJ, Struthers AD. Allopurinol improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2002;106:221–226. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000022140.61460.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George J, Carr E, Davies J, Belch JJ, Struthers A. High-dose allopurinol improves endothelial function by profoundly reducing vascular oxidative stress and not by lowering uric acid. Circulation. 2006;114:2508–2516. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.651117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thanassoulis G, Brophy JM, Richard H, Pilote L. Gout, allopurinol use, and heart failure outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1358–1364. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malek F, Ostadal P, Parenica J, Jarkovsky J, Vitovec J, Widimsky P, Linhart A, Fedorco M, Coufal Z, Miklik R, Kruger A, Vondrakova D, Spinar J. Uric acid, allopurinol therapy, and mortality in patients with acute heart failure–results of the acute heart failure database registry. J Crit Care. 2012;27:737–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gotsman I, Keren A, Lotan C, Zwas DR. Changes in uric acid levels and allopurinol use in chronic heart failure: Association with improved survival. J Card Fail. 2012;18:694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.06.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hare JM, Mangal B, Brown J, Fisher C, Jr, Freudenberger R, Colucci WS, Mann DL, Liu P, Givertz MM, Schwarz RP. Impact of oxypurinol in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Results of the opt-chf study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2301–2309. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Givertz MM, Mann DL, Lee KL, Ibarra JC, Velazquez EJ, Hernandez AF, Mascette AM, Braunwald E. Xanthine oxidase inhibition for hyperuricemic heart failure patients: Design and rationale of the exact-hf study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:862–868. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Setoguchi S, Stevenson LW, Schneeweiss S. Repeated hospitalizations predict mortality in the community population with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Januzzi JL, Troughton R. Are serial bnp measurements useful in heart failure management? Serial natriuretic peptide measurements are useful in heart failure management. Circulation. 2013;127:500–507. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.120485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Day RO, Graham GG, Hicks M, McLachlan AJ, Stocker SL, Williams KM. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of allopurinol and oxypurinol. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46:623–644. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200746080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Packer M. Proposal for a new clinical end point to evaluate the efficacy of drugs and devices in the treatment of chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2001;7:176–182. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2001.25652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freudenberger RS, Schwarz RP, Jr, Brown J, Moore A, Mann D, Givertz MM, Colucci WS, Hare JM. Rationale, design and organisation of an efficacy and safety study of oxypurinol added to standard therapy in patients with nyha class. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:1509–1516. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.11.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the kansas city cardiomyopathy questionnaire: A new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen AI, Aarsland T, Kristiansen M, Haugland A, Dickstein K. Assessing the effect of exercise training in men with heart failure; comparison of maximal, submaximal and endurance exercise protocols. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:684–692. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. JR Stat Soc [B] 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gavin AD, Struthers AD. Allopurinol reduces b-type natriuretic peptide concentrations and haemoglobin but does not alter exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Heart. 2005;91:749–753. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.040477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 accf/aha guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e319. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, Borer JS, Ford I, Dubost-Brama A, Lerebours G, Tavazzi L. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (shift): A randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2010;376:875–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pina IL, Lin L, Weinfurt KP, Isitt JJ, Whellan DJ, Schulman KA, Flynn KE, Investigators H-A. Hemoglobin, exercise training, and health status in patients with chronic heart failure (from the hf-action randomized controlled trial) Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:971–976. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Filippatos G, Farmakis D, Colet JC, Dickstein K, Luscher TF, Willenheimer R, Parissis J, Gaudesius G, Mori C, von Eisenhart Rothe B, Greenlaw N, Ford I, Ponikowski P, Anker SD. Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose in iron-deficient chronic heart failure patients with and without anaemia: A subanalysis of the fair-hf trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1267–1276. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.George J, Struthers A. The opt-chf (oxypurinol therapy for congestive heart failure) trial: A question of dose. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2405. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dulce RA, Yiginer O, Gonzalez DR, Goss G, Feng N, Zheng M, Hare JM. Hydralazine and organic nitrates restore impaired excitation-contraction coupling by reducing calcium leak associated with nitroso-redox imbalance. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6522–6533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.412130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rekhraj S, Gandy SJ, Szwejkowski BR, Nadir MA, Noman A, Houston JG, Lang CC, George J, Struthers AD. High-dose allopurinol reduces left ventricular mass in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:926–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szwejkowski BR, Gandy SJ, Rekhraj S, Houston JG, Lang CC, Morris AD, George J, Struthers AD. Allopurinol reduces left ventricular mass in patients with type 2 diabetes and left ventricular hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2284–2293. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone PH. Allopurinol a new anti-ischemic role for an old drug. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:829–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choe JY, Park SH, Kim SK. Serum cystatin c is a potential endogenous marker for the estimation of renal function in male gout patients with renal impairment. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:42–48. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee HY, Ariyasinghe JT, Thirumoorthy T. Allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome: A preventable severe cutaneous adverse reaction? Singapore Med J. 2008;49:384–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]