Abstract

The success of craniomaxillofacial (CMF) surgery depends not only on the surgical techniques, but also on an accurate surgical plan. The adoption of computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) has created a paradigm shift in surgical planning. However, planning an orthognathic operation using CASS differs fundamentally from planning using traditional methods. With this in mind, the Surgical Planning Laboratory of Houston Methodist Research Institute has developed a CASS protocol designed specifically for orthognathic surgery. The purpose of this article is to present an algorithm using virtual tools for planning a double-jaw orthognathic operation. This paper will serve as an operation manual for surgeons wanting to incorporate CASS into their clinical practice.

Keywords: dentofacial deformity, computer-aided surgical simulation, CASS, double-jaw orthognathic surgery, planning algorithm

Introduction

The success of craniomaxillofacial (CMF) surgery depends not only on surgical techniques, but also on an accurate surgical plan. The adoption of computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) is creating a paradigm shift in surgical planning for patients with CMF deformities. The Surgical Planning Laboratory of Houston Methodist Research Institute has developed a CASS protocol that is specifically designed for orthognathic surgery1. In this protocol, a three-dimensional (3D) composite skull model of a patient is generated to accurately represent the CMF skeleton, the dentition, and the facial soft tissue2–5. In addition, an anatomical reference frame is created for the 3D composite skull model6–8. Virtual osteotomies are then performed and orthognathic surgery is simulated1,3,9–11. Finally, surgical splints and templates are designed in the computer, fabricated by a rapid prototyping machine, and used during surgery to accurately position the bony segments12,13. The protocol has been proven to be more accurate and efficient than the traditional planning methods1,2,8,12,14–17.

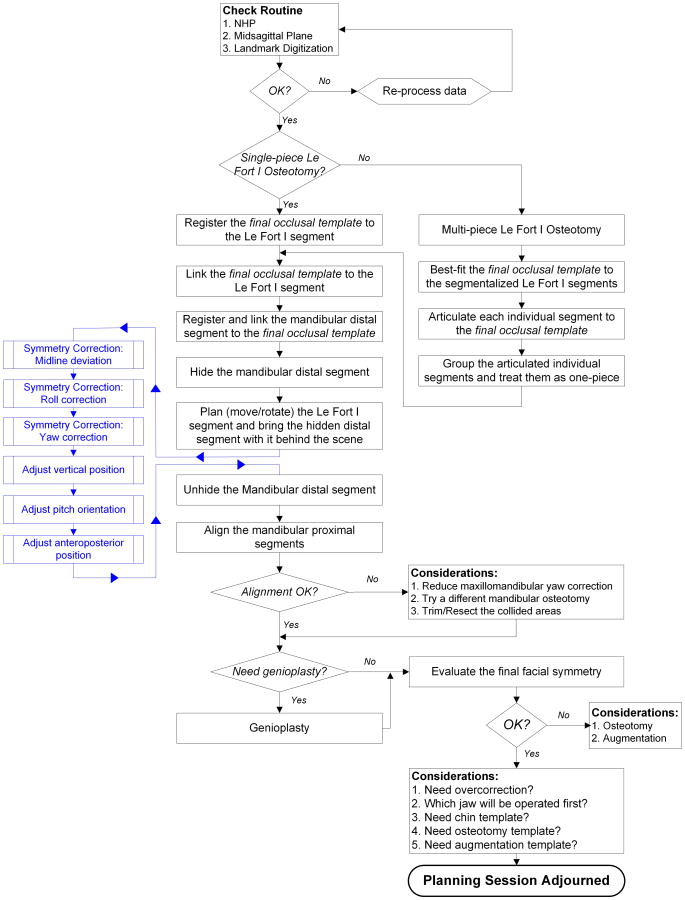

Planning orthognathic surgery using CASS differs fundamentally from planning the same surgery using traditional methods18,19. As a result, we have developed a new planning protocol for CASS. Over the years, this process has been improved to make it more efficient. The purpose of this paper is to present this streamlined CASS protocol (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for planning a double-jaw orthognathic surgery using the CASS protocol.

The CASS protocol

Before employing the CASS protocol, a surgeon must confirm that the patient is ready for surgery, i.e., the desired occlusion is achievable and the patient's growth and medical condition are optimal for the surgery. In order to assess the occlusion, a surgeon hand-articulates progress dental models in class I occlusion, confirming that the patient is ready for surgery. This step is required because a computed tomography (CT) or cone-beam CT (CBCT) scan is needed for CASS, and patients should not be exposed to ionizing radiation if they are not going to have the surgery. For the purpose of this manuscript, the term ‘CT’ is used to refer to both CT and CBCT in the following text, unless specified otherwise.

The CASS protocol presented accomplishes the tasks of modeling, planning, and preparing for plan execution. The task of the modeling is to construct a virtual model of the head (cranium and face). This model has three distinct characteristics: (1) it renders the patient's bones, teeth, and soft tissues with accuracy; (2) its mandible is in centric relation, an important reference position in orthognathic surgery; (3) it has an anatomical reference frame.

CT scans can be used to create 3D models of the facial skeleton, teeth, and soft tissues. However, the teeth of these 3D-CT models are not sufficiently accurate for surgical planning. The CASS protocol presented solves this problem by replacing the inaccurate teeth of the CT with accurate digital dental models that are created by scanning stone dental models. A facial model created by aligning and merging digital dental models into a maxillofacial CT is called a ‘composite model’. This aligning and merging process is called ‘registration’. The registration is done by aligning corresponding features (fiducial markers) that are presented in both images. The fiducial markers can be part of the anatomical structures being imaged, or easy to identify parts that are added in, on, or around the objects (or subjects) before the image acquisition.

We have developed and validated a fiducial registration system for making composite models. In addition to allowing for accurate registration, this system also assures the mandible is in centric relation during CT scanning2,15,16. This system uses a two-part device consisting of a bite-jig and a fiducial face-bow (Fig. 2A). The bite-jig serves two purposes: it anchors the fiducial face-bow to the patient, and it keeps the mandible in centric relation during CT acquisition.

Fig. 2.

Creation of the composite model. (A) A face-bow with fiducial markers is attached to the bite-jig. (B) The patient bites on the bite-jig and face-bow during the CT scan. (C) Four separate but correlated computer models are reconstructed: a midface model, a mandibular model, a fiducial marker model, and a soft tissue model (not shown). (D) The bite-jig and face-bow is placed between the upper and lower plaster dental models during the scanning process. (E) Three separate but correlated digital dental models are also reconstructed: a maxillary dental model, a mandibular dental model, and a fiducial marker model. (F) By aligning the fiducial markers, the digital dental models are incorporated into the 3D-CT skull model. The computerized composite skull model is thus created. It simultaneously displays an accurate rendition of both the bony structures and the teeth.

The composite model used for planning must have an accurate anatomical frame of reference. This is a Cartesian frame that includes a midsagittal plane, an axial plane, and a coronal plane. This reference frame is the basis for most diagnostic and treatment decisions. Incorrectly defining the reference frame may cause postoperative deformity. The reference frame for a composite model is usually established using either anatomical landmarks or the neutral head posture (NHP).

Using anatomical landmarks to create a Cartesian frame seems simple. The midsagittal plane can be constructed using any three midline landmarks. The axial plane can be the Frankfort horizontal (FH) and can be constructed using three of four points: right orbitale, left orbitale, right porion, and left porion. The coronal plane can be constructed as the plane that passes through both porions, remaining perpendicular to the other two planes.

However, this method only works when the face is perfectly symmetrical. In facial asymmetry, various combinations of three midline landmarks produce different midsagittal planes. Various combinations of FH points also result in different axial planes. Moreover, FH is usually not perpendicular to the midsagittal plane in facial asymmetry—a fundamental requirement of a Cartesian system. Finally, a coronal plane cannot be constructed if the two other planes (midsagittal and axial) are not perpendicular. Since all faces have some degree of asymmetry, using anatomical landmarks to build a reference frame is complicated.

The principle behind using NHP is that a reference frame for the head can be derived from the patient's head posture. When a patient stands upright looking straight forward, the cardinal directions of the face are orthogonal to gravity. The axial plane is perpendicular to the gravitational pull and the midsagittal and coronal planes are aligned with it. Thus, when the head is in the NHP, it is simple to construct a reference frame for the face. The axial plane is the horizontal plane that passes through both porions. The midsagittal plane is a vertical plane that best divides the face into right and left halves. The coronal plane is the vertical plane that is perpendicular to the other planes and is aligned with the coronal suture.

The remaining tasks of the CASS protocol are surgical planning and preparing for plan execution. Surgical planning uses a visualized treatment objective (VTO) approach, simulating the operation until the desired outcome is attained (visualized). Preparing for plan execution is getting ready for surgery. To complete this task, a surgeon collects clinical measurements and fabricates physical appliances such as occlusal splints, templates, and drill guides. These appliances are designed in the computer and fabricated using a rapid prototyping machine.

The CASS is implemented clinically in four steps: (1) collection of preoperative records, (2) data processing, (3) surgical planning, and (4) preparing for plan execution. The first and the third steps are completed by a surgeon, while the other two can be outsourced, either to an independent service provider or to a planning specialist within one's clinic or institution.

Clinical implementation of the CASS protocol

Collection of preoperative records

In this step, preoperative data are gathered in an hour-long appointment. This appointment is scheduled 2–4 weeks prior to the surgery. The surgeon and an assistant accrue the records. These include dental impressions and their stone models, a bite-jig, clinical measurements, photographs, a NHP recording, a CT scan, and a bite registration of the final occlusion. This appointment has eight steps: (1) taking and pouring dental impressions; (2) fabricating a bite-jig; (3) taking clinical measurements; (4) clinical photographing the patient; (5) recording the patient's NHP; (6) testing the fit of the bite-jig on the stone dental models; (7) acquiring a CT scan; and (8) establishing final occlusion.

The preoperative record appointment begins by taking and pouring upper and lower dental impressions. A surgeon takes the impressions which are then immediately poured by an assistant. The impressions are taken and poured at the beginning of the appointment to shorten its length. The fitting of the stone dental models on the bite-jig must be confirmed before the patient undergoes a CT scan. However, this check cannot be done until the stone models are set. Since it takes about 45 min for the stone to set, postponing the models will delay the CT. Thus pouring the impressions early allows the models to be ready on time.

The number of impressions needed for planning depends on the type of surgery. Obviously, the surgeon needs to take at least one upper and one lower impression. But, when one is planning to segmentalize a dental arch into two or more pieces, the clinician should take two impressions of the arch needing segmentation.

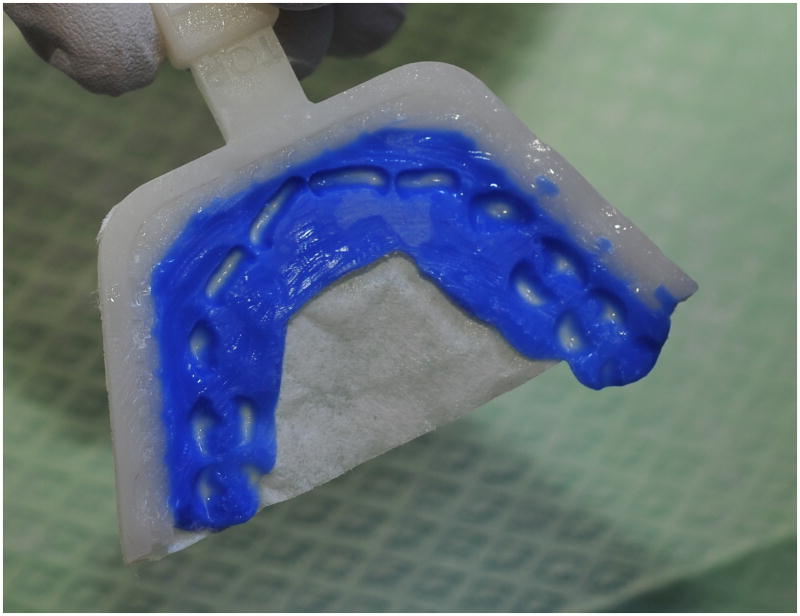

In the second step of the preoperative appointment, a patient-specific bite-jig is constructed by customizing a stock jig frame (Fig. 3). The surgeon customizes the frame by adding a self-curing, dimensional-stable and rigid bite registration material (e.g. LuxaBite; DMG America, Englewood, NJ, USA) to the frame. The jig is then placed between the patient's teeth until the material is cured. This bite registration should be taken in centric relation.

Fig. 3.

Fabrication of the patient-specific bite-jig using a three-layer approach to prevent undercuts on the bite-jig and correctly record centric relation. The first layer of the registration material is only placed on the maxillary side of the bite-jig frame to capture the geometry of the maxillary dental occlusal surfaces (A). Before the material completely sets (e.g., about 2–3 min), the bite-jig should be gently and repeatedly taken off (B) and placed back (C) on the teeth a few times in order to get rid of any possible undercuts. Once the material is completely set (e.g., about 5 min), the first layer should be ground to thin it but remain thick enough to ‘lock’ onto the maxillary occlusal surface (D). The bite-jig is then replaced on the maxillary dental arch. The surgeon should make every attempt to position the patient's mandible to centric relation. While in the centric relation, the second layer is added at the buccal and labial side of the bite-jig (E). Once the material is completely set, a third layer is added to capture the geometry of the mandibular dental occlusal surfaces (F). Guided by the second layer, the mandible should be positioned in centric relation for the third layer impression using the same method as indicated for the first layer.

In the third step of the preoperative appointment, key clinical measurements needed for planning are recorded. These include: (1) rest-incisal-show and smile-dentogingival-show, to determine the vertical position of the maxilla; (2) dental midpoint (midline) deviations, to determine transverse jaw position.

In the fourth step, clinical photographs of the patient are taken. The photographs should image the face and the teeth. The facial photographs should be taken with the patient in the NHP. In addition, a plumb line should be shown on the background, so the correct orientation of the face can be determined later. These photographs will be used to verify that the virtual head model is correctly oriented for planning.

In the fifth step of the preoperative appointment, the NHP is recorded. This measurement is needed to create an anatomical reference frame (midsagittal, axial, and coronal planes) for the virtual facial model. To record the NHP, the authors use an electronic orientation sensor (3DM; MicroStrain Inc., Williston, VA, USA). The sensor is first attached to the previously fabricated bite-jig (Fig. 4A, B)6–8. The jig is then placed between the patient's teeth. The patient is asked to stand upright with their head in NHP. Finally, in this posture, the pitch, roll, and yaw of the sensor are recorded.

Fig. 4.

Orientation of the composite skull model to the neutral head posture (NHP) using the digital orientation sensor method. (A) A digital orientation sensor is attached to the bite-jig and face-bow. (B) The pitch, roll, and yaw of the sensor are recorded. (C) In the computer, a digital replica (CAD model) of the orientation sensor is registered to the composite skull model via the fiducial markers, and the two objects are attached to each other. (D) The recorded pitch, roll, and yaw are applied to the face-bow frame, reorienting the composite skull model to the NHP. (E) After the composite skull is orientated to the NHP, the CAD model of the orientation sensor is marked hidden.

The NHP can be attained by asking the patient to self-balance into this stance, or by manipulating their heads into this posture. The authors begin with a self-balance position, but feel free to manipulate it, if the patient's posture is incorrect.

In the sixth step, a surgeon or an assistant tests the fit of the stone dental models on the bite-jig. This test is done to confirm that the models and the bite-jig are correct. If the models do not fit the bite registration, one can assume that either the dental models or the bite-jig are distorted. Common reasons for the lack of fit are air bubbles on the occlusal surfaces of the dental impressions and deep indentations in the bite registration. Air bubbles in an impression are filled with stone during pouring, resulting in spherical bumps that arise from the surfaces of teeth. These prevent the model from seating into the bite registration. Fortunately, they are easily spotted and removed with a sharp instrument to improve the fitting. Deep indentations in the bite registration, especially those that extend above the height of the contour of the teeth, also prevent the models from fully seating on the bite registration. This lack of seating occurs because the material used for bite registration is rigid. This problem can be solved by grinding the bite registration to reduce the indentations.

If the dental models and bite-jig still do not fit after the above maneuvers, the bite-jig should be retested on the patient's teeth. If the bite-jig fits the patient well, it must be assumed that the stone models are distorted. The dental impressions should be repeated. If the bite-jig does not fit well, the jig should be relined, and the NHP recording should be repeated, because relining of the bite-jig can affect the alignment of the orientation sensor.

In the seventh step of the preoperative appointment, a CT scan is obtained. Before scanning, the fiducial registration face-bow is attached to the bite-jig and the jig is affixed to the patient (Fig. 2B). The patient is instructed to keep his/her facial soft tissues relaxed during scanning. The scan can be completed using either a spiral multi-slice CT scanner (using the standard scanning algorithm: matrix of 512 × 512 at 0.625–1.25 mm slice thickness, 25 cm or lesser field-of-view, and 0° gantry tilt) or a CBCT scanner (with an isotropic voxel size of 0.4 mm).

In the final eighth step of the preoperative appointment, the surgeon establishes the final occlusion. This is usually done after the patient leaves the clinic. Currently, we establish the final occlusion on stone dental models because there is no reliable method to establish final occlusion in the computer, especially when one of the jaws is segmentalized.

When dental arch segmentation is not required, the maxillary and the mandibular stone dental models are mounted on a Galetti articulator and articulated into final occlusion. Final occlusion is then captured with a bite registration taken with a stable material like silicone or polyvinyl siloxane.

When arch segmentation is required (e.g., a three-piece Le Fort I osteotomy), a surgeon cuts the extra stone dental model into the required number of segments. Then, the surgeon hand-articulates each segment into final occlusion and makes a new plaster base for the segmented model. Finally, the surgeon articulates the upper and lower models into final occlusion (in a Galetti articulator), capturing the occlusion with a bite registration.

Data processing

The second step of CASS is data processing. This takes place after all the preoperative records have been gathered. It can be done by the surgeon, or it can be outsourced to an independent service provider, or to a person familiar with CASS planning within the surgeon's clinic or institution. Data processing entails the creation of a composite head model, the creation of an anatomical reference frame for the head model, the digitization of cephalometric landmarks, the creation of the virtual osteotomies, and the establishment of final occlusion.

The first step in data processing is to create a virtual model that displays an accurate rendition of the skeleton, the soft tissues, and the teeth. Four separate but correlated 3D-CT models are generated: a midface model, a mandibular model, a soft tissue model, and a fiducial marker model (Fig. 2C). This task is completed using specialized planning software. Digital dental models (Fig. 2E) are then generated by scanning the stone dental models with the fiducial registration frame in place (Fig. 2D), either with a high-resolution laser scanner, or with a CBCT scanner (at a high resolution setting of isotropic voxel size 0.125 to 0.2 mm). Next, the digital dental models are incorporated into the 3D-CT models by registering the fiducial markers of the digital dental models to the markers of the 3D-CT (Fig. 2F).

The second step in data processing is to establish an anatomical reference frame for the head model. An accurate anatomical reference frame is critical for planning. The recorded NHP (the pitch, roll, and yaw of the head) is used to orient the computer head model to the NHP. Using the fiducial face-bow as reference, the NHP of the computer model is established by applying the recorded pitch, roll, and yaw to the face-bow frame (Fig. 4C–E)8.

Once the virtual head model is in the NHP, the construction of a reference frame is straightforward. The midsagittal plane is the vertical plane that best divides the head into right and left halves. The axial plane is the horizontal plane that is perpendicular to the midsagittal plane, passing closest to the right and left porion. The coronal plane is the vertical plane that is perpendicular to the other planes, aligned with the coronal suture.

The third data processing step is to digitize all the cephalometric landmarks and to perform a cephalometric analysis. The surgeon may request any cephalometric analysis but should take into consideration that 3D cephalometry is significantly more complex than its two-dimensional (2D) counterpart. Simply adapting 2D cephalometric measurements to 3D space may cause diagnostic errors. This is explained in detail in the companion article on 3D cephalometry. If necessary, landmark digitization can be altered later in the planning phase.

The fourth data processing step is to perform virtual osteotomies, e.g., a Le Fort I osteotomy, mandibular ramus osteotomies, and a genioplasty (Fig. 5A). If necessary, these osteotomies can be revised or redone during the planning phase. At this stage, all the osteotomized segments remain in their original positions. Their movements are completed later in the planning phase.

Fig. 5.

Incorporating the final-occlusal-template and placement of the mandibular distal segment into final occlusion in a single-piece Le Fort I osteotomy. (A) In this example, virtual osteotomies, including a single-piece Le Fort I osteotomy and bilateral sagittal split osteotomy, are completed. Each bony segment is located in its original location. (B) The digital final-occlusal-template is generated by scanning the hand-articulated stone models using a high-resolution scanner. (C) The upper part (maxillary teeth) of the final-occlusal-template is first registered to the maxillary teeth in the composite model. (D) The mandible is set into the final occlusion by registering the distal mandibular teeth to the lower part (mandibular teeth) of the template.

The last step of data processing is to establish virtual final occlusion (Fig. 5). This is done by copying the final occlusion that was established by the surgeon on the stone dental models. First, the upper and lower stone models are articulated into final occlusion using the bite registration provided by the surgeon. Next, the models are scanned together, using a high-resolution optical surface scanner, or a CBCT scanner. Finally, the scan is segmented to create a 3D image of the upper and lower teeth in final occlusion (Fig. 5B). This image, the ‘final-occlusal-template’, is imported into the planning software and is used as a guide to articulate the jaws in final occlusion.

The virtual final occlusion is established in the following manner: First, the upper teeth of the final-occlusal-template are aligned to the upper teeth of the Le Fort I segment (Fig. 5C). Then, the distal mandibular segment is moved until its lower teeth are aligned to the lower teeth of the template (Fig. 5D). Because the upper and lower teeth of the template are in final occlusion, aligning the template to one jaw and then aligning the other jaw to the template, automatically places both jaws into final occlusion.

After the distal mandible is set in final occlusion, it is linked to the Le Fort I segment. As a result, future movements of the Le Fort segment will be automatically transferred to the mandibular segment. This guarantees that the final occlusion is maintained during the planning process. Maintaining the final occlusal relationship during the maxillary movements simplifies mandibular planning,

In a double-jaw surgery with a single-piece Le Fort I osteotomy, it is simple to align the upper teeth of the final-occlusal-template to the upper teeth of the Le Fort I segment, since they are identical (Fig. 5). This is not true in a multi-piece Le Fort I. In this case, the shapes of the upper dental arches of the virtual head model and the final-occlusal-template are different. This is because the template depicts the upper jaw segments in their final alignment, while the virtual head model depicts the upper teeth in their original condition (Fig. 6). In this situation the alignment is completed in two steps.

Fig. 6.

Incorporating the final-occlusal-template in a multiple-piece Le Fort I osteotomy. (A) In this example, a three-piece Le Fort I osteotomy is completed. All bony segments (yellow) are located in their original locations. (B) The upper part (maxillary teeth) of the digital final-occlusal-template. The template is also generated by scanning the hand-articulated stone models, in which the upper stone model is first cut into three pieces, then hand-articulated to the final occlusion without using an articulator. Note that the posterior Le Fort I segments in the composite model are medial. (C) The upper part of the final-occlusal-template is registered to the maxillary teeth at the central dental midline, best fitting the posterior parts of the teeth. (D) All Le Fort I segments are then perfectly registered to the corresponding segment in the final-occlusal-template, resulting in a new intra-arch relationship among the Le Fort I segments.

First, the final-occlusal-template is best fit to the maxillary arch of the composite models, and then each Le Fort I segment is individually moved until their teeth are aligned with the template. This creates a new intra-arch relationship for the Le Fort I segments (Fig. 6D). Afterwards, the individual Le Fort segments are grouped together forming one piece. From then on, the Le Fort I unit is treated as one piece, as in a one-piece Le Fort I osteotomy.

Surgical planning

The third step of the CASS protocol is surgical planning. This is done in the computer using CASS software. The process may be completed by a surgeon working alone, or by a surgeon working together with a planning specialist familiar with the software. In the case where an outside service center is utilized, the planning specialist from the service center communicates with the surgeon and any other parties (e.g., orthodontist) via a Web meeting. In this meeting, all parties view the same images, even if the people involved are located in different countries. Guided by clinical measurements and real-time 3D cephalometric measurements, a surgeon plans orthognathic surgery by simulating surgical procedures and visualizing their outcomes. This VTO process is iterated until the desired results are obtained.

The planning process begins with a checklist to ensure that the data processing is correct. The checklist includes the following items: (1) Is the anatomical reference frame correctly defined? (2) Are all the cephalometric landmarks correctly digitized? (3) Are all virtual osteotomies correct? (4) Is the final occlusion accurate?

Orthognathic surgery can involve one or both jaws. Planning a single-jaw surgery is simpler than planning a double-jaw operation. In order to best describe how to plan an orthognathic operation using CASS, double-jaw surgery will be used as an example. Once the planning algorithm for a double-jaw surgery is understood, it is easy to adopt it to a single-jaw procedure.

CASS planning for any double-jaw surgery should always begin with the maxilla (Fig. 1), even when mandibular surgery is performed first. The reason for this is that the surgeon is more certain of where the maxilla should go than the mandible. The upper jaw should not be canted (zero roll) and should have zero yaw. The upper dental midline (incisal midpoint) should be on the midsagittal plane. And, vertically, the incisor-show should be normal at rest and smiling.

Correction of maxillary deformities

Planning begins by hiding the mandible and moving the maxilla into the ideal alignment. A series of transformations (translations and rotations) are needed to reach this alignment. Rotational transformations are best done on a single point, following a specific sequence. Empirically, we have determined that the best point at which all transformations should be performed is the incisal midpoint, the point at the intersection of the dental midline and the arc defined by the incisal edges. This point represents the middle of the dental arch. Selecting it avoids iterations. For the same purpose, we have also established the following planning sequence: (1) symmetric alignment, including (a) normalization of transverse position, (b) normalization of roll, (c) normalization of yaw; (2) normalization of vertical position; (3) normalization of pitch; (4) normalization of anteroposterior position.

In the first step, the maxilla is symmetrically aligned to the midsagittal plane. Symmetric alignment involves three transformations: transverse translation, roll rotation, and yaw rotation. Transverse translation places the maxillary incisal midpoint on the midsagittal plane. Roll rotation pivots the maxilla around the incisal midpoint until the right and left teeth are vertically leveled. Finally, yaw rotation pivots the maxilla around the incisal midpoint. This makes sure that the posterior teeth are as equidistant as possible to the midsagittal and coronal planes.

In the second step, the vertical position of the maxilla is normalized. The planner translates the maxilla up or down, placing its incisal midpoint in an ideal position in relation to the upper lip stomion.

In the third step, one normalizes the maxillary pitch. The planner pivots the maxilla around the incisal midpoint until its pitch is optimized. Maxillary pitch rotation affects the inclination of the maxillary central incisors, the inclination of the maxillary occlusal plane, the airway size, the projection of the anterior nasal spine, and chin projection. It is necessary to consider all these items when deciding on the ideal maxillary pitch for a given patient. The first three items relate to function, the last two to esthetics. Frequently, the planner needs to make compromises among the items based on the priorities of an individual case.

The inclinations of the maxillary central incisors and the occlusal plane are important for disocclusion—the separation of upper and lower teeth during eccentric movements of the mandible. The average inclination of the maxillary central incisor to the horizontal plane is 117.0° ± 6.9° for a male and 110.5° ± 9.1° for a female20. The average occlusal plane inclination to the horizontal plane is 9.3° ± 3.8° 21. These values are useful when deciding the maxillary pitch.

With regards to the airway, decreasing maxillary pitch increases mandibular projection. When the mandible moves forward the tongue moves with it, enlarging the retroglossal airway space. The opposite occurs when the maxillary pitch is increased.

In assessing the projection of anterior nasal spine (ANS) and chin, increasing the maxillary pitch (by rotating the maxilla around the incisal midpoint) increases the projection of ANS and decreases the projection of the chin. Increasing the ANS projection rotates the nasal tip upwards, widening the nasolabial angle. Decreasing maxillary pitch has the opposite effect.

The final adjustment aligns the maxilla in an anteroposterior position. This adjustment is performed last because previous transformations can alter one's decision as to how much to advance the maxilla. For example, decreasing the maxillary pitch or changing its yaw can produce a collision between the maxillary tuberosities and the pterygoid plates. These collisions can be avoided easily by advancing the upper jaw.

Correction of mandibular deformities

After the maxilla is set into an ideal alignment, the mandible is rendered. The distal segment of the mandible will automatically be in the final alignment because it had been linked previously to the maxilla in final occlusion. Each of the transformations applied to the maxilla was transferred to the distal mandible.

In the next step, the proximal segments of the mandible are aligned. Each proximal segment is rotated around the center of its condyle until the segment is well aligned with the distal mandible. Ideally, there should be no overlap between the proximal and distal segments, as overlap corresponds to areas of bony collision. When present, segment overlap can be avoided by readjusting the yaw of the maxilla and distal mandible, by planning the resection (ostectomy) of the areas of overlap, or by planning a different ramus osteotomy.

Readjustment of the yaw of the maxilla and distal mandible by one or two degrees can avoid proximal segment collision without altering esthetics. Adjustments larger than two degrees should be avoided as they can produce buccal corridor asymmetry—the right to left difference in the amount of posterior teeth displayed while smiling. In order to prevent displacement of the previous corrections, all yaw readjustment must be made around the upper incisal midpoint. Small areas of bone overlap are amenable to ostectomy. However, large areas of collision that remain after maxillary yaw adjustment can only be avoided by selecting a different operation (e.g., by selecting an inverted L osteotomy over a sagittal split).

Correction of chin deformities

In the next step, the planner reexamines the chin. This assessment is necessary because the movement of the mandibular distal segment alters chin position. If the chin is normal, the planner proceeds to the final step. If it is abnormal, the planner should simulate a genioplasty, moving the chin segment until satisfied with the outcome.

Examination of the residual final symmetry

In the last step, the planner assesses final symmetry. When the mandible is abnormal but symmetric, placing the distal mandible in final occlusion maintains symmetry. However, when the patient has intrinsic mandibular asymmetry, placing the distal mandible into final occlusion may not correct the asymmetry. Since mild to moderate degrees of intrinsic asymmetry may be imperceptible to the eye, it is important to complete a final symmetry assessment on all patients.

The final assessment of symmetry is done using a mirror image routine (Fig. 7). In this routine, the composite model is cut in half across the median plane. One side is then copied and reflected (flipped) across the median plane, superimposing it over the contralateral half. The right–left differences are calculated using a Boolean subtraction—a mathematical operation that shows differences between objects. If the symmetry is good, the plan is complete. However, if there is residual asymmetry, the surgeon should consider an osteoplasty, which may entail augmentation of reduction.

Fig. 7.

Mirror image routine. (A) The planned outcome after all bony segments are moved to their desired positions. (B) One side of the face is first copied. (C) The copy is flipped horizontally. (D) The flipped copy is superimposed on the contralateral side; finally, side-to-side differences are calculateed.

Preparing for plan execution

A computerized plan is of no clinical value if it cannot be executed at the time of surgery. The final step of the CASS protocol is to prepare the tools necessary for transferring the computerized surgical plan to the patient at the time of the surgery. This is usually outsourced to an independent service provider.

The tables and images that display the planned movements, including mapped areas of collision, are generated and displayed at surgery in order to guide the operation. Moreover, surgical splints are designed in the computer and fabricated using a rapid prototyping machine1,3,10,12,15. The genioplasty template system that was first developed by our Surgical Planning Laboratory and other bone templates (e.g., graft or ostectomy) and cutting and drilling guides can also be fabricated as needed1,3,10,15. Surgical plates can either be pre-bent on a physical model3,10,22, or custom-fabricated23. If necessary, a roadmap can also be created for the navigational surgery to guide the surgeon performing osteotomies and drilling screw holes3,22,24.

Discussion

Planning an orthognathic surgery using CASS is conceptually different from planning the same operation using traditional planning methods, e.g., stone dental models. In stone dental model surgery, one executes all transformations, including rotations, as linear translations of particular points. A surgeon may correct a maxillary roll malrotation (occlusal canting) by moving the right first molar 2 mm down and the left first molar 4 mm up. This maneuver not only corrects the malrotation but also establishes the final vertical position for these points. In CASS, one has six degrees of freedom, being able to measure inclination (pitch, roll, and yaw) in degrees and position (anteroposterior, vertical, and transverse) in millimeters, independently of each other. This freedom is actually helpful because a deformed maxilla can have a right 5° roll (cant) and a steep pitch (occlusal plane inclination) of 15°, and still be superiorly positioned. In CASS, the surgeon can correct each deformity independently. The planner can adjust the roll by rotating the upper jaw 5° to the left (the pivot being the incisal midpoint). The planner can then adjust the pitch by rotating the upper jaw 7° down (the pivot being the incisal midpoint). Finally, once the roll and the pitch are corrected, the ideal vertical position can be established.

Another difference between the CASS and the traditional planning methods is the sequence of the planning process. In traditional double-jaw stone dental model surgery, the position of the upper jaw is established first and the lower jaw is then placed in the final occlusion for the final alignment. In CASS, the final occlusion is established first and then both jaws are moved together into the final alignment while they are occluded in final occlusion.

Finally, in this CASS protocol, the stone dental models are still needed to establish the final occlusion. An experienced operator can articulate a set of stone dental models to the final occlusion in a matter of seconds. However, the same is not true in the virtual world where the dental arches are represented by two 3D models that lack collision constraints. The computer system does not prevent the two models from moving through each other once the model surfaces make contact. In addition, the operator has no tactile feedback when digitally articulating the models. Because of these difficulties, it may take hours in the computer to achieve a best possible maximal intercuspation. More importantly, it is nearly impossible to be certain whether what is seen in the computer represents the actual best maximal intercuspation.

Currently, we are not using computerized dental alignment to treat real patients, because a small deviation in occlusion can cause significant problems. To ensure that final occlusion is correct, we scan the stone dental models while they are physically positioned in this position, creating a final-occlusal-template. This template is then incorporated into the composite skull model to guide the placement of the maxilla and mandible into final occlusion. Our laboratory and several others are trying to automate the establishment of final occlusion25–27. We expect that in the future, the need of the stone dental models will be eliminated and this step will be done within the software.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr Chen was sponsored by the Taiwan Ministry of Education while he was working at the Surgical Planning Laboratory, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, TX, USA. Dr Tang was sponsored by the China Scholarship Council while he was working at the Surgical Planning Laboratory, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, TX, USA. This work was supported in part by NIH/NIDCR research grants 5R42DE016171, 5R01DE022676, and 1R01DE021863.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr James Xia, Dr Jaime Gateno, and Dr John Teichgraeber receive a patent royalty from Medical Modeling Inc. through the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Dr Xia and Dr Gateno receive a second patent royalty from Medical Modeling Inc. through Houston Methodist Hospital.

Ethical approval: No human subjects.

Patient consent: Patient signed consent was obtained.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF. New clinical protocol to evaluate craniomaxillofacial deformity and plan surgical correction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2093–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gateno J, Xia J, Teichgraeber JF, Rosen A. A new technique for the creation of a computerized composite skull model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:222–227. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF. Three-dimensional computer-aided surgical simulation for maxillofacial surgery. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005;13:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swennen GR, Mommaerts MY, Abeloos J, De Clercq C, Lamoral P, Neyt N, Casselman J, Schutyser F. The use of a wax bite wafer and a double computed tomography scan procedure to obtain a three-dimensional augmented virtual skull model. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:533–539. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e31805343df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swennen GR, Mollemans W, Schutyser F. Three-dimensional treatment planning of orthognathic surgery in the era of virtual imaging. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2080–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schatz EC. MS thesis. The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; 2006. A new technique for recording natural head position in three dimensions. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schatz EC, Xia JJ, Gateno J, English JD, Teichgraeber JF, Garrett FA. Development of a technique for recording and transferring natural head position in 3 dimensions. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:1452–1455. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181ebcd0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia JJ, McGrory JK, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF, Dawson BC, Kennedy KA, Lasky RE, English JD, Kau CH, McGrory KR. A new method to orient 3-dimensional computed tomography models to the natural head position: a clinical feasibility study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia J, Ip HH, Samman N, Wang D, Kot CS, Yeung RW, Tideman H. Computer-assisted three-dimensional surgical planning and simulation: 3D virtual osteotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gateno J, Xia JJ, Teichgraeber JF, Christensen AM, Lemoine JJ, Liebschner MA, Gliddon MJ, Briggs ME. Clinical feasibility of computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) in the treatment of complex cranio-maxillofacial deformities. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell RB. Computer planning and intraoperative navigation in orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gateno J, Xia J, Teichgraeber JF, Rosen A, Hultgren B, Vadnais T. The precision of computer-generated surgical splints. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:814–817. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swennen GR, Barth EL, Eulzer C, Schutyser F. The use of a new 3D splint and double CT scan procedure to obtain an accurate anatomic virtual augmented model of the skull. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia JJ, Shevchenko L, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF, Taylor TD, Lasky RE, English JD, Kau CH, McGrory KR. Outcome study of computer-aided surgical simulation in the treatment of patients with craniomaxillofacial deformities. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2014–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu SS, Gateno J, Bell RB, Hirsch DL, Markiewicz MR, Teichgraeber JF, Zhou X, Xia JJ. Accuracy of a computer-aided surgical simulation protocol for orthognathic surgery: a prospective multicenter study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF, Christensen AM, Lasky RE, Lemoine JJ, Liebschner MA. Accuracy of the computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) system in the treatment of patients with complex craniomaxillofacial deformity: a pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCormick SU, Drew SJ. Virtual model surgery for efficient planning and surgical performance. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell WH. Surgical correction of dentofacial deformities. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell WH. Modern practice in orthognathic and reconstructive surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatia SN, Leighton BC. A manual of facial growth—a computer analysis of longitudinal cephalometric growth data. 1st. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Downs WB. The role of cephalometrics in orthodontic case analysis and diagnosis. Am J Orthod. 1952;38:162–182. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia JJ, Gateno J, Teichgraeber JF. A new paradigm for complex midface reconstruction: a reversed approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciocca L, Mazzoni S, Fantini M, Persiani F, Baldissara P, Marchetti C, Scotti R. A CAD/CAM-prototyped anatomical condylar prosthesis connected to a custom-made bone plate to support a fibula free flap. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2012;50:743–749. doi: 10.1007/s11517-012-0898-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malis DD, Xia JJ, Gateno J, Donovan DT, Teichgraeber JF. New protocol for 1-stage treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis using surgical navigation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1843–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang YB, Xia JJ, Gateno J, Xiong Z, Teichgraeber JF, Lasky RE, Zhou X. In vitro evaluation of new approach to digital dental model articulation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:952–962. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang YB, Xia JJ, Gateno J, Xiong Z, Zhou X, Wong ST. An automatic and robust algorithm of reestablishment of digital dental occlusion. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29:1652–1663. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2049526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia JJ, Chang YB, Gateno J, Xiong Z, Zho X. Automated digital dental articulation. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2010;13:278–286. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-15711-0_35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]