Abstract

Background

Flow-diverter devices (FDDs) are new-generation stents placed in the parent artery at the level of the aneurysm neck to disrupt the intra-aneurysmal flow thus favoring intra-aneurysmal thrombosis.

Objective

The objective of this review article is to define the indication and results of the treatment of intracranial aneurysms by FDD, reviewing 18 studies of endovascular treatment by FDDs for a total of 1704 aneurysms in 1483 patients.

Methods

The medical literature on FDDs for intracranial aneurysms was reviewed from 2009 to December 2014. The keywords used were: “intracranial aneurysms,” “brain aneurysms,” “flow diverter,” “pipeline embolization device,” “silk flow diverter,” “surpass flow diverter” and “FRED flow diverter.”

Results

The use of these stents is advisable mainly for unruptured aneurysms, particularly those located at the internal carotid artery or vertebral and basilar arteries, for fusiform and dissecting aneurysms and for saccular aneurysms with large necks and low dome-to-neck ratio. The rate of aneurysm occlusion progressively increases during follow-up (81.5% overall rate in this review). The non-negligible rate of ischemic (mean 4.1%) and hemorrhagic (mean 2.9%) complications, the neurological morbidity (mean 3.5%) and the reported mortality (mean 3.4%) are the main limits of this technique.

Conclusion

Treatment with FDDs is a feasible and effective technique for unruptured aneurysms with complex anatomy (fusiform, dissecting, large neck, bifurcation with side branches) where coiling and clipping are difficult or impossible. Patient selection is very important to avoid complications and reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality. Further studies with longer follow-up are necessary to define the rate of complete occlusion.

Keywords: Intracranial aneurysm, brain aneurysm, flow-diverter devices, pipeline embolization device, Silk embolization device, surpass embolization device, endovascular treatment

Introduction

Flow-diverter devices (FDDs) are new-generation stents placed in the parent artery at the level of the aneurysm neck to disrupt the intra-aneurysmal flow, providing significant rheologic effects with potential changes in transmural pressure gradient. They progressively create intra-aneurysmal thrombosis, offering good support for the development of a neointima.

Although the introduction of this device is relatively recent, experience is rapidly increasing and large studies have been reported. However, choice of the best endovascular procedure and indications for the use of FDDs are still a matter of debate and deserve to be discussed.

Five types of FDDs have been approved for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: the Pipeline Embolization Device (PED) (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA), the Silk (Balt Extrusion, Montmorency, France), the Flow Re-direction Endoluminal Device (FRED) (Microvention, Tustin, CA, USA), the p64 Flow-Modulation Device (Phoenix, AZ, USA) and the Surpass Flow-Diverter (Surpass; Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA) (Figure 1). Almost all studies report experience with PED and Silk;1,2 on the other hand, experience with FRED,3,4 Pipeline Flex5 and p646 is still very limited.

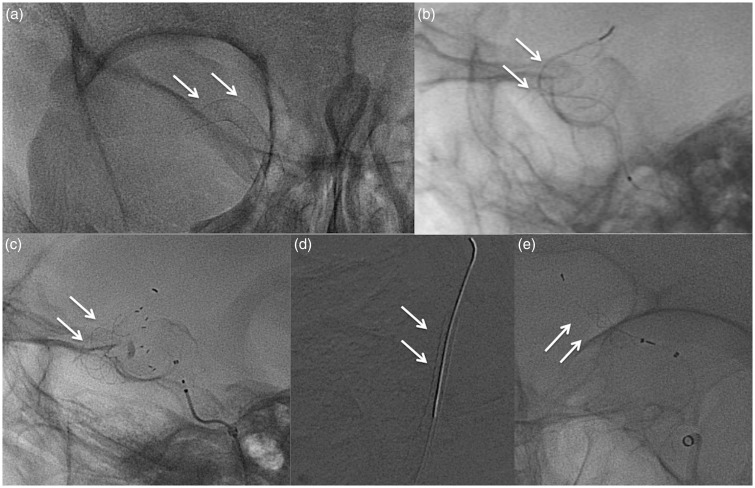

Figure 1.

Flow-diverter devices approved for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Visibility under fluoroscopy: (a) pipeline embolization device (PED); (b) Silk; (c) Flow Re-direction Endoluminal Device (FRED); (d) Surpass; (e) p64.

We have reviewed 18 studies of intracranial aneurysms treated with PED, Silk and Surpass with FDDs.7–24 Our aim is to contribute to the definition of indications and limits of this procedure.

Methods

This study was designed and conducted to define the indication and results of the treatment of intracranial aneurysms by FDD.

Search strategy

The medical literature on FDDs for intracranial aneurysms was reviewed from 2009 to December 2014. The keywords used were: “intracranial aneurysms,” “brain aneurysms,” “flow diverter,” “flow diverting,” “pipeline embolization device,” “silk flow diverter,” “surpass flow diverter” and “FRED flow diverter.”

If the same patient population is described in two studies, only the larger and more recent one is included. If a single-center study was included in a multicenter study, the single-center study was excluded.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria for the reviewed studies were: a) a series of at least 20 patients; b) reporting on the duration of the follow-up; c) documenting the rate of angiographic aneurysm occlusion; d) documenting the death rate and the neurological complications during the follow-up.

Analyzed data

Epidemiological data included number of patients, gender, age, clinical presentation (unruptured versus ruptured aneurysms).

Aneurysm characteristics were location (anterior circulation versus posterior circulation), morphology (saccular, fusiform, dissecting, blister), size (small or <10 mm, large or 10 to 24 mm and giant or >25 mm), neck width and dome-to-neck ratio.

Treatment characteristics included previous endovascular and/or neurosurgical treatments, type of FDD (PED, Silk, Surpass), number of FDDs used for each patient or aneurysm, and eventual coiling in association to stenting.

Endpoints

Angiographic complete occlusion and timing.

Post-procedural complications, both early and delayed, and both symptomatic and asymptomatic ischemic and hemorrhagic events.

Neurological morbidity and mortality.

Results

Study characteristics

Eighteen studies of cerebral aneurysms treated by FDDs and published between 2009 and 2014 are included in this review7–24 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 18 included studies.

| Study | N° of participating centers and countries | Type | Morbidity | Mortality | N° of patients | N° of aneurysms | Type of FDD |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PED | Silk | Surpass | |||||||

| Lylyk et al. 20097 | Unicenter (Argentina) | Prospective | 0% | 0% | 53 | 63 | 72 | – | – |

| Byrne et al. 20108 | Multicenter (England) | Prospective | 4% | 8% | 70 | 70 | – | 67 | – |

| Lubicz et al. 20109 | Multicenter (Belgium) | Prospective | 15% | 4% | 29 | 34 | – | 36 | – |

| Berge et al. 201210 | Multicenter (France) | Retrospective | 7.8% | 3% | 65 | 77 | – | 73 | – |

| Briganti et al. 201211 | Multicenter (Italy) | Retrospective | 3.7% | 5.9% | 273 | 295 | 182 | 151 | – |

| McAuliffe et al. 201212 | Multicenter (Australia) | Prospective | 0% | 0% | 54 | 57 | 98 | – | – |

| Fischer et al. 201213 | Unicenter (Germany) | Retrospective | 5.6% | 1.1% | 88 | 101 | 235 | – | – |

| Wagner et al. 201214 | Unicenter (Denmark) | Retrospective | 5% | 5% | 22 | 26 | – | 23 | – |

| Maimon et al. 201215 | Unicenter (Israel) | Retrospective | 7.2% | 3.6% | 28 | 32 | – | 31 | – |

| Pistocchi et al. 201216 | Unicenter (France) | Prospective | 3.7% | 0% | 26 | 30 | 9 | 23 | – |

| Tähtinen et al. 201217 | Multicenter (Finland) | Retrospective | 4% | 4% | 24 | 24 | – | 29 | – |

| Saatci et al. 201218 | Unicenter (Turkey) | Retrospective | 1% | 0.5% | 191 | 251 | 324 | - | – |

| Velioglu et al. 201219 | Unicenter (Turkey) | Retrospective | 6.6% | 6.6% | 76 | 87 | – | 91 | – |

| Yu et al. 201220 | Multicenter (China) | Prospective | 3.5% | 3.5% | 143 | 178 | 213 | – | – |

| Colby et al. 201321 | Unicenter (USA) | Retrospective | 3% | 3% | 34 | 41 | 64 | – | – |

| Çinar et al. 201322 | Unicenter (Turkey) | Prospective | 0% | 2.2% | 45 | 55 | 66 | – | – |

| O’Kelly et al. 201323 | Multicenter (Canada) | Retrospective | 4.3% | 6.4% | 97 | 97 | 156 | – | – |

| Wakhloo et al. 201524 | Multicenter (USA/Europe) | Prospective | 4.2% | 2.4% | 165 | 186 | – | – | 165 |

| Total | 1483 | 1704 | 1349 | 524 | 165 | ||||

FDD: flow-diverter device; PED: pipeline embolization device; USA: United States of America.

Seven studies25–31 were excluded because the number of patients was less than 20.

Seven other studies also were excluded because they report a smaller subset of patients included in larger reviews. Finally, six series39–44 have been excluded because only a subset of patients was analyzed (only one localization, only small aneurysms, etc.).

Among the 18 reviewed studies, nine are multicenter and nine are single center; eight are prospective and 10 retrospective. They include 1483 patients with 1704 intracranial aneurysms (Table 1).

Patient population

The 18 studies include 1483 patients (Table 2). The gender and age are specified in 17 studies for a total of 1413 patients. There is a large prevalence of females over males (74.2% versus 25.8%). The mean age is 54.2 years (range 47.9–61 years); a rather homogeneous case distribution between 48 and 59 years is evidenced, with only two studies reporting a mean age >60 years.

Table 2.

Patient, aneurysm and treatment characteristics (18 studies).

| Patient population (17 studies) | 1413 patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Females | 1048 (74.2%) | |

| Males | 365 (25.8%) | ||

| Age (mean) | 54.2 year | ||

| Clinical presentation (18 studies) | 1483 patients | ||

| Unruptured aneurysms | 1337 (90%) | ||

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 146 (10%) | ||

| Aneurysm characteristics | |||

| Location (18 studies) | 1704 aneurysms | ||

| Anterior circulation | 1492 (87.5%) | ||

| Posterior circulation | 212 (12.5%) | ||

| Morphology (17 studies) | 1407 aneurysms | ||

| Saccular | 1140 (81%) | ||

| Fusiform-dissecting | 249 (17.7%) | ||

| Blister | 18 (1.3%) | ||

| Size (13 studies) | 1019 aneurysms | ||

| Small (<10 mm) | 571 (56%) | ||

| Large (10–24 mm) | 328 (32.2%) | ||

| Giant (>25 mm) | 120 (11.8%) | ||

| Mean diameter (four studies) | Range 10.4–19 mm | ||

| Neck width (15 studies) | 1290 aneurysms | ||

| Absolute values (seven studies; 710 aneurysms) | >4 mm | 586 (82.5%) | |

| <4 mm | 124 (17.5%) | ||

| Mean diameter (eight studies; 560 aneurysms) | 3 to 6 mm | Two studies | |

| >6 mm | Five studies | ||

| Dome-to-neck ratio (nine studies) | 920 aneurysms | ||

| Absolute values (five studies) | <2 | ||

| Mean diameter (four studies) | 0.4–1.6 | ||

| Treatment characteristics | |||

| Previous treatments (14 studies) | 1009 patients | ||

| Yes | 244 (24.2%) (range: 3.4%–47%) | ||

| No | 765 (75.8%) | ||

| Number of FDDs for each aneurysm (17 studies) | 1674 aneurysms | ||

| One | 1223 (73%) | ||

| Two or more | 451 (27%) | ||

| FDD + coiling (16 studies) | 134 aneurysms (7.8%) (range 0–5.9%) |

FDD: flow-diverter devices.

According to the clinical presentation cited in all studies, 90% of the patients had unruptured aneurysms (both incidental or presenting with headache, cranial nerve palsy or symptoms of mass effect), whereas a previous subarachnoid hemorrhage was referred to in 10% of the patients.

Aneurysm characteristics

The aneurysm characteristics of the 18 reviewed series are summarized in Table 2.

Location, cited in all 18 series, was mainly in the anterior circulation (1492 aneurysms or 87.5%) and more rarely in the posterior circulation (212 aneurysms or 12.5%). Among aneurysms of the anterior circulation, the exact site was specified in 14 studies (for a total of 1503 aneurysms); those located at the internal carotid artery (ICA) up to the bifurcation were largely prevalent (1368 aneurysms or 90%) whereas those of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and middle cerebral artery (MCA) were scarcely represented (135 or 10%). Among aneurysms of the posterior circulation, the exact location was specified in 12 series (157 aneurysms); 121 (77%) were located at the vertebral or basilar arteries and 36 (23%) at the posterior cerebral or cerebellar arteries.

Aneurysm morphology was specified in 17 among 18 series (1407 aneurysms). They were mainly saccular (87.5%), more rarely fusiform or dissecting (17.7%), exceptionally blister (1.3%).

The aneurysms were classified according to size in 13 series (1019 aneurysms); 56% were small (<10 mm), 32.2% large (10–25 mm) and 11.8% giant (>25 mm). Four other series provided the mean diameter, ranging from 10.4 mm to 19 mm. Thus, no significant differences of aneurysm size were found with respect to general aneurysm incidence.

Neck width was specified in 15 studies (1290 aneurysms). Seven among them provide absolute values (>4 mm in 586 aneurysms or 82.5% and <4 mm in only 124 or 17.5%); eight other studies provide the mean diameter (>6 mm in five studies and between 3 mm and 6 mm in two).

Dome-to-neck ratio was specified in nine studies (920 aneurysms). Five showed values <1.6 and four between 0.4 and 1.6.

Treatment characteristics

The PED was used alone in eight studies, the Silk in seven, both PED and Silk in two and the Surpass in one. On the whole, the PED was implanted in 1349 patients, the Silk in 524 and the Surpass in 165 (Table 1).

A previous endovascular or surgical treatment that failed to obtain the aneurysm occlusion was referred to in 244 of the 1009 patients (24.2%), 14 studies of which reported this finding.

The number of FDDs for each aneurysm was specified in 17 studies. Most aneurysms (73%) were treated by a single FDD; two or more FDDs were used in 27%.

Additional coiling was also realized during the FDD implantation in 134 procedures (7.8%) among 16 studies, with a variable rate from no case to 59%.

Technical procedural problems

Technical procedural problems included failure to catheterize the parent artery, failure in stent implantation and deployment, imprecise FDD placement resulting in incomplete neck covering, distal and poor opening, guidewire rupture, and dissection of the artery wall. These procedural complications were cited in 17 studies with a mean incidence of 8.3% (range 0–23.1%).

Complications

Parent artery thrombosis and stenosis were reported both in acute (12 studies) and late stages (16 studies) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results and complications (18 studies).

| Technical procedural problems (17 studies) | 8.3% (range 0–23.1%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Parent artery thrombosis or significant (>50%) stenosis | Acute stage (12 studies) | 3.8% (range 0–8.3%) |

| Late (16 studies) | 6.8% (0–18%) | |

| Ischemic complications (18 studies) | 4.1% (range 0–14.2%) | |

| Hemorrhagic complications (18 studies) | 2.9% (range 0–7.5%) | |

| Neurological morbidity (18 studies) | 3.5% (range 0–15%) | |

| Mortality (18 studies) | 3.4% (range 0–8%) | |

| Rate of complete aneurysm occlusion (18 studies) | Overall rate at final follow-up (18 studies) | 81.5% (range 69%–100%) |

| Immediate (six studies) | 10.8% (range 2%–18.2%) | |

| Three months (three studies) | 60% (range 44%–85%) | |

| Six months (nine studies) | 74.5% (range 50%–93%) | |

| 12 months (eight studies) | 89.6% (range 81%–100%) | |

| Only overall data (3–12 months) (five studies) | 77% (range 69%–87%) |

Occlusion or significant stenosis of the parent artery during the FDD implantation procedure was observed with a mean incidence of 3.8% (range 0 to 8.3%). The main causes of intraprocedural thrombosis of the parent artery were technical problems in the stent deployment.

Late occlusion or significant stenosis (>50%) of the parent artery was found during the angiographic follow-up in 6.8% of the patients in 16 studies (range 0–18%). This event is more often incidental and occurs at or after stopping antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel.

Ischemic complications were cited in all 18 studies. The total ischemic stroke rate was 4.1%. Ischemic complication did not occur in four series;7,12,22,23 in the other 14 studies their rate ranges from 1% to 14.2%.

Ischemic complications were due both to parent artery or side branch occlusion and perforator infarction. Their incidence was higher for posterior circulation than for anterior circulation aneurysms (5.6% versus 3.5%) and for large-giant than for small aneurysms (6.2% versus 2.8%).

Hemorrhagic complications were cited in all 18 studies. The total rate was 2.9%. Intraparenchimal or subarachnoid hemorrhage did not occur in six studies;7,12,14,16,17,21 in the others, their rate ranges from 2.2% to 7.5%.

The incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage was higher for large-giant than for small aneurysms (4% versus 1.8%) whereas the aneurysm location was not significant.

Morbidity and mortality

Permanent morbidity related to the procedure was reported in all 18 studies, with a mean rate of 3.5%. No permanent deficits occurred in three studies;7,12,22 in the others the morbidity rate varied from 1% to 15%.

The mortality rate was also reported in all 18 studies, ranging from 0.5 to 8% (mean rate 3.4%). Only three studies7,12,16 did not observe procedure-related mortality.

Aneurysm occlusion

The mean angiographic follow-up was nine months (range 3–30 months).

At the final follow-up of the 18 reviewed studies, the mean rate of complete aneurysm occlusion was 81.5% (range 69%–100%)

Immediate aneurysm occlusion at the angiographic control at the end of the procedure was reported in six studies7,9,10,16,19,23 with a mean rate of 10.8% (range 2%–18.2%).

At the first post-procedural follow-up control (three months), the mean rate of complete aneurysm occlusion significantly increased (60% in three studies), with one series11 reporting high occlusion rate at this stage (85%).

At the following angiographic controls, the mean rate of complete aneurysm occlusion progressively increased: 74.5% at six months in nine studies and 89.6% at 12 months in eight studies.

According to the type of FDD, the mean final occlusion rate was 88.2% in eight PED studies and 83% in seven Silk studies, whereas the occlusion rate of the unique Surpass study24 was significantly lower (75%).

The rate of aneurysm occlusion was not significantly correlated with aneurysm size and morphology.

Discussion

Endovascular occlusion with coils is the more widely used treatment for intracranial aneurysms. However, it carries significant risk of long-term recanalization (0.7% rebleeding rate at one year45). Additionally, aneurysms with wide necks, those with complex anatomy (fusiform and giant) and those of the bifurcation are sometimes untreatable. Therefore, more complex endovascular techniques have been developed, including stent-assisted coiling (SAC)46 and balloon-assisted coiling (BAC).47 Nevertheless, the rates of recanalization reported with these techniques are high (12% for SAC46 and 10% for BAC47), and retreatments may sometimes be necessary. In addition, when it is necessary to perform a second procedure it is mandatory to take into consideration the risks of secondary rupture and the related morbidity and mortality (benefit/risk ratio). Furthermore, in particularly large aneurysms, the large number of coils implanted during the procedure could perpetuate the mass effect initially present and be responsible for neurological complications.

FDDs are rapidly becoming a suitable alternative to traditional endosaccular treatments for uncoilable aneurysms. However, experience with these devices is still recent and the indications and results must be better defined.

We have reviewed the most important studies on the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with FDDs.

The data from this large review may allow us to define several indications and limits of this technique.

FDDs have mainly been used for unruptured aneurysms. Although flow reduction in the aneurysm sac is immediate, the delay necessary to obtain complete occlusion in most cases makes its use dangerous for ruptured aneurysms. In addition, the need for antiaggregation therapy and dual antiplatelet therapy carries a high risk of rebleeding after subarachnoid hemorrhage.

ICA aneurysms, mainly supra and paraclinoid, seem to be the best indication, because of the easier access, the large artery caliber and the absence of perforators (Figures 2–4). Aneurysms of the vertebral and basilar arteries are also well treated, although the presence of perforators and branches to the brainstem carries higher risk of ischemic complications. Distal and bifurcation aneurysms of ACA and MCA (Figure 5) are less frequently treated (10% versus 90% of ICA aneurysms in this review), because of the less-easy access due to the more distal location and the presence of bifurcation and side branches, resulting in more late occlusion.43

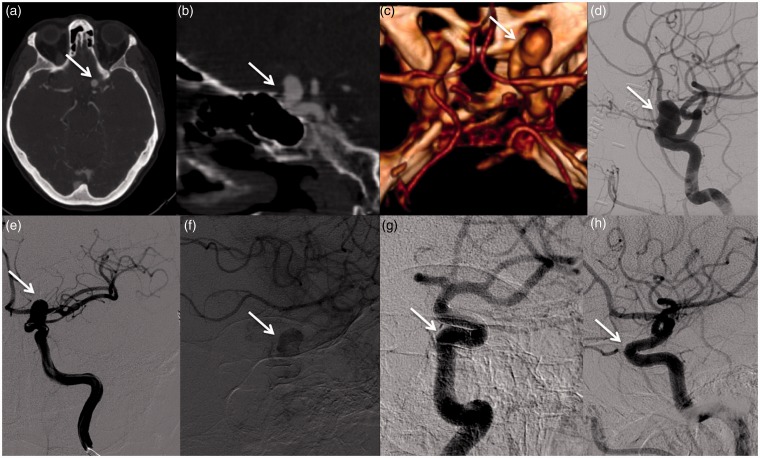

Figure 2.

Images of a 61-year-old woman harboring a wide-neck left small carotid-ophthalmic aneurysm. Computed tomography angiography (CTA): axial native images (a), two-dimensional (2D) sagittal multi-planar reconstructions (MPRs) (b), three-dimensional (3D) volume rendering (VR) reconstruction (c). Preoperative digital subtraction angiogram (DSA) (d); interventional procedure: Pipeline Embolization Device (PED) deployment (e); nonsubtracted images after deployment: immediate contrast stasis in the sac (f); three-month angiogram (g, h): complete occlusion of the aneurysm.

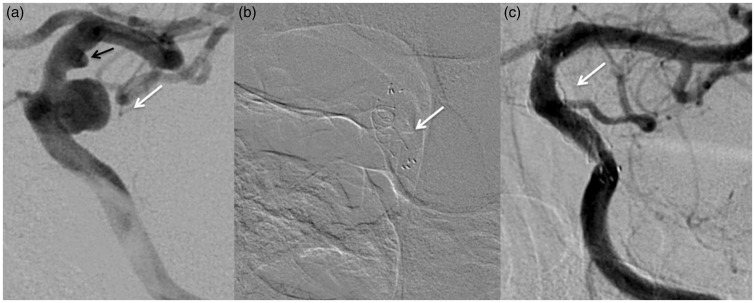

Figure 3.

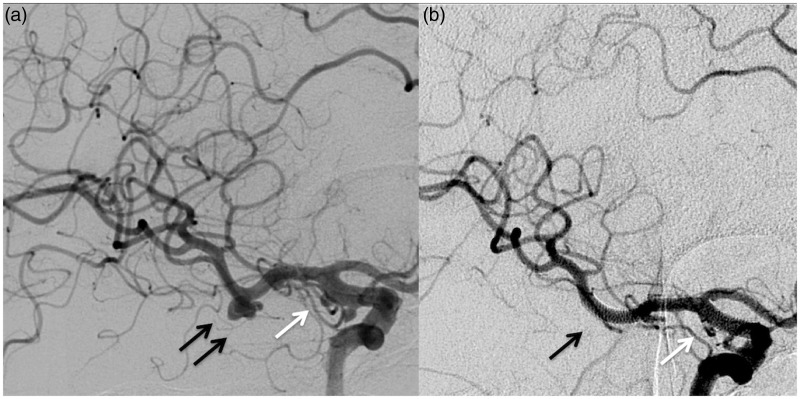

Images of a 52-year-old woman with a left small posterior communicating artery aneurysm (white arrow) and a smaller cranial supraclinoid infundibuloma (black arrow). Before (a) and three months after (b) the endovascular procedure with Flow Re-direction Endoluminal Device (FRED).

Figure 4.

Images of a 57-year-old woman harboring a large left carotid-ophthalmic aneurysm (a); Before (a) and nine months after (b) the endovascular procedure with Pipeline Embolization Device (PED).

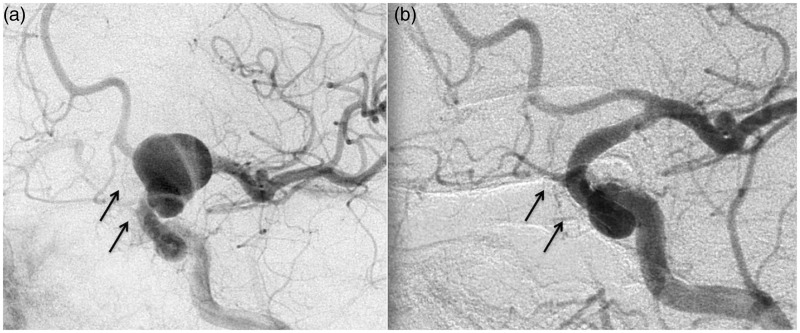

Figure 5.

Images of a 68-year-old woman harboring a right M1–M2 bifurcation middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysm (black arrow) and two small aneurysms of the posterior wall of the supraclinoid internal carotid artery (ICA) (white arrow). Before (a) and six months after (b) the endovascular procedure with two Pipeline Embolization Devices (PEDs).

In our analysis when morbidity and mortality are discussed, an extremely broad range of results has been discovered. For morbidity (1%–15%) the only study with the higher rate is the one by Lubicz et al.;9 however, it is important to emphasize the main limitations of this series, namely the relatively small number of patients enrolled and the initial experience with FDD. For mortality (0.5%–8%), the rate is obviously higher for more complex cases, particularly for large and giant aneurysms and for those located in the posterior circulation. In fact, in large and giant aneurysms, we did experience complications, but their rate is far lower than the natural history and the lack of efficacy of other treatment options.

FDDs may be used to treat aneurysms of all sizes. Fusiform, dissecting and blister represent about 20% of the aneurysms treated in our analysis. FDD seems to be the best option because of the possibility of reconstructing the diseased parent vessel, with no recanalization risk. Morbidity, mortality and occlusion rates are similar to the ones reported for saccular aneurysms; further prospective studies for those particular aneurysms are necessary to define the real potential of this type of treatment.

Among saccular aneurysms, those with large necks and low dome-to-neck ratio should preferably be treated by FDDs because they respond less favorably to other treatments.

However, some limitations of the treatment with FDDs must be considered.

The aneurysm occlusion is usually delayed and occurs within several months; thus, bleeding from the aneurysms, mainly large and giant, may occur soon after the procedure.

Spreading of these innovative devices is hampered by the relatively high cost of the FDD. A recent study has analyzed the costs related to the aneurysm treatment with conventional devices (coils, stents and balloon) and FDD.48 An FDD may be economically feasible in aneurysms >11 mm, aneurysms between 6 mm and 11 mm that require an adjunctive device and aneurysms <6 mm that require a stent.48

The need for a long-term post-procedural dual antiplatelet therapy up to the aneurysm occlusion increases the risk of bleeding from previously ruptured aneurysms and unruptured, still not occluded aneurysms, mainly large and giant. However, early withdrawal of the therapy may result in in-stent and parent artery thrombosis.

Multiple dual antiplatelet regimens are used but there is no consensus about the best medical strategies in neurointerventional procedures.49 The endpoint of the treatment is a sufficient P2Y12 and COX1 thrombocyte receptor inhibition to avoid thrombotic or hemorrhagic events. Clopidogrel combined with aspirin is considered the therapy of choice against platelet aggregation.49 However, not all patients respond to clopidogrel and aspirin; in fact the evidence reveals a complex pharmacokinetic profile, with multiple players involved, including cytochromes, characteristics of the target tissue, and accompanying clinical conditions. Thus, a tailored anti-aggregation treatment based on an ex-vivo platelet function test (PFT) has been suggested.50 Pre-procedure P2Y12 reaction units value (PRU) with the VerifyNow test has shown to predict perioperative thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications.50 Clopidogrel hyporesponders (PRU > 200–240) are switched to prasugrel (10 mg) while for clopidogrel hyper-responders (PRU < 60–80) the dose is adjusted as needed to reach the target PRU range (60–240).50

Testing all patients undergoing FDD treatment is a matter of debate. In fact, a recent meta-analysis has shown no significant association between PFT and symptomatic events.51

Technical procedural problems of treatment with FDDs are not infrequent and may lead to failure of the procedure. Limited experience with these devices and the long learning curve are the main causes of failure.

Finally, the rate of ischemic and hemorrhagic complications and neurological morbidity is not negligible, particularly when a group of patients with smaller unruptured aneurysms is considered.52–55

Conclusion

Treatment with FDDs is a feasible and effective technique for unruptured aneurysms with complex anatomy (fusiform, dissecting, large neck, bifurcation) where coiling and clipping are difficult or impossible.

Data from the reviewed studies confirm that FDDs are mainly used for aneurysms of the anterior circulation, for those of larger arteries (internal carotid artery, vertebral and basilar artery), for both saccular and fusiform-dissecting aneurysms of all sizes, and particularly for aneurysms with large neck width and low dome-to-neck ratio.

Patient selection is very important to avoid complications and reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality.

The results of this treatment in terms of aneurysm occlusion seem to be good. However, experience is still recent and follow-up has been short. Thus, further studies with longer follow-up are necessary to define the rate of complete occlusion.

Conflict of interest

F.B. serves as proctor for COVIDIEN. The other Authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Arrese I, Sarabia R, Pintado R, et al. Flow-diverter devices for intracranial aneurysms: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2013; 73: 193–199. discussion 199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinjikji W, Mohammad HM, Lanzino G, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with flow diverters: A meta-analysis. Stroke 2013; 44: 442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz O, Gist TL, Manjarez G, et al. Treatment of 14 intracranial aneurysms with the FRED system. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: 614–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kocer N, Islak C, Kizilkilic O, et al. Flow Re-direction Endoluminal Device in treatment of cerebral aneurysms: Initial experience with short-term follow-up results. J Neurosurg 2014; 120: 1158–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira VM, Kelly M, Vega P, et al. New Pipeline Flex device: Initial experience and technical nuances. J Neurointerv Surg. Epub ahead of print 3 October 2014. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briganti F, Leone G, Marseglia M, et al. p64 Flow Modulation Device in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: Initial experience and technical aspects. J Neurointerv Surg. Epub ahead of print 20 April 2015. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015–011743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lylyk P, Miranda C, Ceratto R, et al. Curative endovascular reconstruction of cerebral aneurysms with the pipeline embolization device: The Buenos Aires experience. Neurosurgery 2009; 64: 632–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne JV, Beltechi R, Yarnold JA, et al. Early experience in the treatment of intra-cranial aneurysms by endovascular flow diversion: A multicentre prospective study. PloS One 2010; 5: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubicz B, Collignon L, Raphaeli G, et al. Flow-diverter stent for the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms: A prospective study in 29 patients with 34 aneurysms. Stroke 2010; 41: 2247–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berge J, Biondi A, Machi P, et al. Flow-diverter silk stent for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: 1-year follow-up in a multicenter study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1150–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briganti F, Napoli M, Tortora F, et al. Italian multicenter experience with flow-diverter devices for intracranial unruptured aneurysm treatment with periprocedural complications—a retrospective data analysis. Neuroradiology 2012; 54: 1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAuliffe W, Wycoco V, Rice H, et al. Immediate and midterm results following treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms with the pipeline embolization device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer S, Vajda Z, Aguilar Perez M, et al. Pipeline embolization device (PED) for neurovascular reconstruction: Initial experience in the treatment of 101 intracranial aneurysms and dissections. Neuroradiology 2012; 54: 369–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner A, Cortsen M, Hauerberg J, et al. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Reconstruction of the parent artery with flow-diverting (Silk) stent. Neuroradiology 2012; 54: 709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maimon S, Gonen L, Nossek E, et al. Treatment of intra-cranial aneurysms with the SILK flow diverter: 2 years’ experience with 28 patients at a single center. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012; 154: 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pistocchi S, Blanc R, Bartolini B, et al. Flow diverters at and beyond the level of the circle of Willis for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 2012; 43: 1032–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tähtinen OI, Manninen HI, Vanninen RL, et al. The silk flow-diverting stent in the endovascular treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms: Technical aspects and midterm results in 24 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery 2012; 70: 617–623. discussion 623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saatci I, Yavuz K, Ozer C, et al. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms using the Pipeline flow-diverter device: A single-center experience with long-term follow-up results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1436–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velioglu M, Kizilkilic O, Selcuk H, et al. Early and midterm results of complex cerebral aneurysms treated with Silk stent. Neuroradiology 2012; 54: 1355–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu SC, Kwok CK, Cheng PW, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: Mid-term outcome of pipeline embolization devices—a prospective study in 143 patients with 178 aneurysms. Radiology 2012; 265: 893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colby GP, Lin LM, Gomez JF, et al. Immediate procedural outcomes in 35 consecutive pipeline embolization cases: A single-center, single-user experience. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5: 237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Çinar C, Bozkaya H, Oran I. Endovascular treatment of cranial aneurysms with the pipeline flow-diverting stent: Preliminary mid-term results. Diagn Interv Radiol 2013; 19: 154–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Kelly CJ, Spears J, Chow M, et al. Canadian experience with the pipeline embolization devices for repair of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 381–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakhloo AK, Lylyk P, de Vries J, et al. Surpass flow diverter in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: A prospective multicenter study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cirillo L, Dall’Olio M, Princiotta C, et al. The use of flow-diverting stents in the treatment of giant cerebral aneurysms: Preliminary results. Neuroradiol J 2010; 23: 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulcsár Z, Ernemann U, Wetzel SG, et al. High-profile flow diverter (silk) implantation in the basilar artery: Efficacy in the treatment of aneurysms and the role of the perforators. Stroke 2010; 41: 1690–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szikora I, Berentei Z, Kulcsar Z, et al. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms by functional reconstruction of the parent artery: The Budapest experience with the pipeline embolization device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 1139–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan TT, Chan KY, Pang PK, et al. Pipeline embolisation device for wide-necked internal carotid artery aneurysms in a hospital in Hong Kong: Preliminary experience. Hong Kong Med J 2011; 17: 398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deutschmann HA, Wehrschuetz M, Augustin M, et al. Long-term follow-up after treatment of intracranial aneurysms with the Pipeline embolization device: Results from a single center. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 481–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puffer RC, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, et al. Patency of the ophthalmic artery after flow diversion treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2012; 116: 892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siddiqui AH, Kan P, Abla A, et al. Complications after treatment with pipeline embolization for giant distal intracranial aneurysms with or without coil embolization. Neurosurgery 2012; 71: E509–E513. discussion E513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonardi M, Cirillo L, Toni F, et al. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms using flow-diverting silk stents (BALT): A single centre experience. Interv Neuroradiol 2011; 17: 306–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lubicz B, Collignon L, Raphaeli G, et al. Pipeline flow-diverter stent for endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms: Preliminary experience in 20 patients with 27 aneurysms. World Neurosurg 2011; 76: 114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson PK, Lylyk P, Szikora I, et al. The pipeline embolization device for the intracranial treatment of aneurysms trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piano M, Valvassori L, Quilici L, et al. Mid-term and long-term follow-up of cerebral aneurysms treated with flow diverter devices: A single-center experience. J Neurosurg 2012; 118: 408–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz JP, Chow M, O’Kelly C, et al. Delayed ipsilateral parenchymal hemorrhage following flow diversion for the treatment of anterior circulation aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 603–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Vries J, Boogaarts J, Van Norden A, et al. New generation of Flow Diverter (Surpass) for unruptured intracranial aneurysms: A prospective single-center study in 37 patients. Stroke 2013; 44: 1567–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briganti F, Napoli M, Leone G, et al. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms by flow diverter devices: Long-term results from a single center. Eur J Radiol 2014; 83: 1683–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Barros Faria M, Castro RN, Lundquist J, et al. The role of the pipeline embolization device for the treatment of dissecting intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 2192–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips TJ, Wenderoth JD, Phatouros CC, et al. Safety of the pipeline embolization device in treatment of posterior circulation aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puffer RC, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, et al. Patency of the ophthalmic artery after flow diversion treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2012; 116: 892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saleme S, Iosif C, Ponomarjova S, et al. Flow-diverting stents for intracranial bifurcation aneurysm treatment. Neurosurgery 2014; 75: 623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Briganti F, Delehaye L, Leone G, et al. Flow diverter device for the treatment of small middle cerebral artery aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. Epub ahead of print 20 January 2015. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin E, Brouillard AM, Xiang J, et al. Endovascular management of adjacent tandem intracranial aneurysms: Utilization of stent-assisted coiling and flow diversion. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2015; 157: 379–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebledding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet 2005; 366: 809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chalouhi N, Jabbour P, Singhal S, et al. Stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms: Predictors of complications, recanalization, and outcome in 508 cases. Stroke 2013; 44: 1348–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cottier JP, Pasco A, Gallas S, et al. Utility of balloon-assisted Guglielmi detachable coiling in the treatment of 49 cerebral aneurysms: A retrospective, multicenter study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 345–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rai A, Cline B, Tarabishy A, et al. P-002 The financial impact of flow diverters on the endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6(Suppl 1): A21–A22. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faught RW, Satti SR, Hurst RW, et al. Heterogeneous practice patterns regarding antiplatelet medications for neuroendovascular stenting in the USA: A multicenter survey. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: 774–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delgado Almandoz JE, Crandall BM, Scholz JM, et al. Pre-procedure P2Y12 reaction units value predicts perioperative thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications in patients with cerebral aneurysms treated with the Pipeline Embolization Device. J Neurointerv Surg 20135 Suppl 3): iii3–iii10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skukalek SL, Winkler AM, Kang J, et al. Effect of antiplatelet therapy and platelet function testing on hemorrhagic and thrombotic complications in patients with cerebral aneurysms treated with the pipeline embolization device: A review and meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. Epub ahead of print 10 November 2014. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moscato G, Cirillo L, Dall’Olio M, et al. Management of unruptured brain aneurysms: Retrospective analysis of a single centre experience. Neuroradiol J 2013; 26: 315–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kapsas G, Budai C, Toni F, et al. Evaluation of CTA, time-resolved 4D CE-MRA and DSA in the follow-up of an intracranial aneurysm treated with a flow diverter stent: Experience from a single case. Interv Neuroradiol 2015; 21: 69–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caranci F, Tedeschi E, Leone G, et al. Errors in neuroradiology. Radiol Med. Epub ahead of print 17 July 2015. DOI 10.1007/s11547-015-0564-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Budai C, Cirillo L, Patruno F, et al. Flat panel angiography images in the post-operative follow-up of surgically clipped intracranial aneurysms. Neuroradiol J 2014; 27: 203–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]