Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) are the largest family of targets for current therapeutics. The classic model of their activation was binary, where agonist binding induced an active conformation and subsequent downstream signaling. Subsequently, the revised concept of biased agonism emerged, where different ligands at the same GPCR selectively activate one downstream pathway versus another. Advances in understanding the mechanism of biased agonism has led to the development of novel ligands, which have the potential for improved therapeutic and safety profiles. In this review, we summarize the theory and most recent breakthroughs in understanding biased signaling, examine recent laboratory investigations concerning biased ligands across different organ systems, and discuss the promising clinical applications of biased agonism.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor, biased agonism, β-arrestin, G protein, allosterism

INTRODUCTION

The G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family is the largest family of receptors and holds significance in both research and clinical practice, as the majority of current therapeutic drugs target GPCRs [1, 2]. Given their importance, this family of receptors has long been studied, and several operational models have been created and revised in order to describe GPCR signaling. In the classic paradigm, a GPCR was believed to function as a binary switch that could be activated by agonist binding or inhibited by antagonist blockade of agonist binding [1, 3]. In the mid-1990s, it became clear that GPCR signaling was more elaborate than a simple binary switch model where different ligands at the same GPCR were shown to selectively activate one downstream pathway versus another [4]. The complexity of GPCR signaling and biased agonism was further uncovered when different receptor conformations, receptor phosphorylation patterns, receptor binding sites, and even receptor independent bias was shown to activate unique downstream responses [4]. Given the tremendous physiologic distribution and great therapeutic importance of this receptor family, this elaborate signaling system has been the focus of tremendous basic research and drug discovery efforts. In this review, we summarize the theory and most recent breakthroughs in understanding biased signaling, examine recent laboratory investigations concerning biased ligands across different organ systems, and discuss the promising clinical applications of biased agonism.

CONCEPT OF FUNCTIONAL SELECTIVITY AND BIASED SIGNALING

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

GPCRs, also known seven-transmembrane receptors (7TMRs), are involved in nearly every mammalian physiologic process. A GPCR system involves a ligand, receptor, and transducer, as discussed below [1]. In response to extracellular ligands, such as hormones, neurotransmitters, and lipids, GPCRs adopt specific “active” conformations that lead to activation of a wide range of intracellular responses. In the classical paradigm, this conformational change promotes the activation of heterotrimeric G proteins, which exchange GDP for GTP to dissociate into Gα and Gβγ dimers and stimulate signaling via accumulation of second messenger molecules or transducers such as cAMP, IP3, DAG [5]. After agonist activation, most GPCRs quickly lose the ability to respond to a hormone, which is referred to as desensitization. Two protein families, the G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) and arrestins, were found to mediate desensitization. The GRK family (GRK 1-7) is a class of seryl-threonyl kinases, which phosphorylate the cytoplasmic tail of agonist-occupied receptors [6–8]. Phosphorylated GPCRs have a high-affinity for arrestins, which exist as four isoforms: two expressed mostly in photoreceptors and so called “visual” arrestins (arrestin-1 and arrestin-4) and two ubiquitous arrestins (β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2). β-Arrestin competes with G proteins for receptor binding sites and therefore leads to receptor desensitization [9–11]. While originally identified for its importance in desensitization, in the past decade many additional roles of β-arrestin have come to light. β-Arrestin serves as an adaptor for receptor endocytosis and serves as a scaffolding protein to recruit and activate cytoplasmic signaling proteins and pathways [12, 13].

Functional Selectivity vs. Biased Signaling

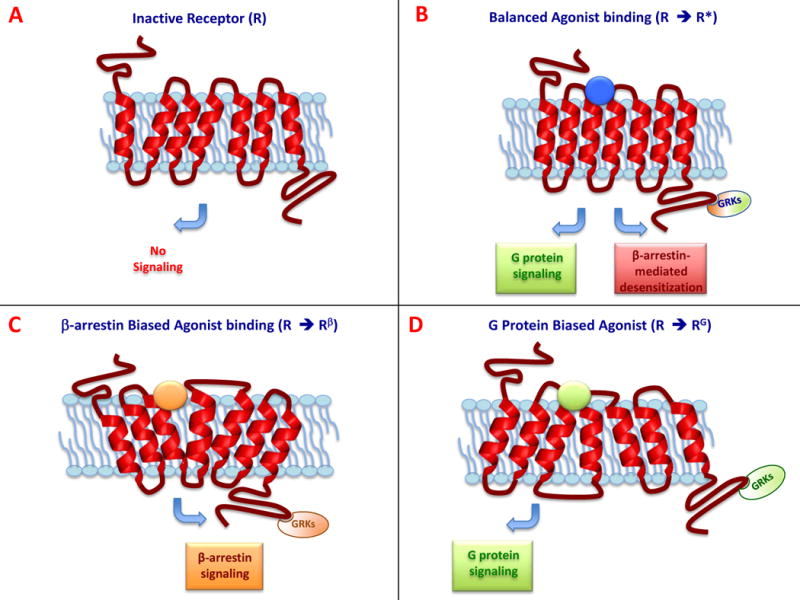

In the classic binary model of GPCR activation, agonist binding activated downstream signaling, and antagonist binding prevented agonist binding, rendering the receptor inactive. However, this simple paradigm proved inadequate, as it was discovered that certain ligands, now referred to as biased ligands, could selectively activate a subset of the receptor’s downstream signaling cascade [14]. Biased ligands are able to stabilize distinct conformations of the GPCR to promote interaction with specific transducers, leading to the selective activation of downstream pathways (Figure 1). In contrast, unbiased or “balanced” ligands activate downstream signaling more globally, without selectivity for specific downstream signaling cascades [14, 15]. This review will mainly focus on β-arrestin bias, where it has been shown that an agonist can induce different transducer-specific efficacies from a single GPCR as a result of unique ligand-receptor-transducer coupling [16].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of GPCR signaling. (A) In the absence of ligand, the receptor is in an inactive conformation (R). (B) In response to a balanced agonist, the activated receptor (R*) couples to, and signals through, both G protein-dependent and the β-arrestin-dependent pathways. (C) A β-arrestin-biased ligand stabilizes a conformational state of the receptor (Rβ) that binds β-arrestin as the transducer leading to selective β-arrestin signaling. (D) A G protein biased ligand stabilizes a different receptor conformation (RG), which binds G-proteins to transduce selective G protein signaling.

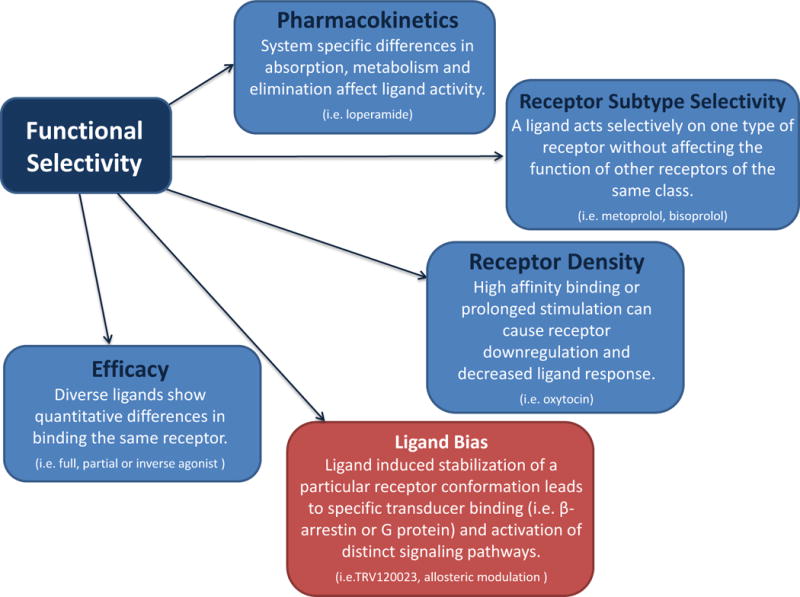

It becomes important at this point to define the terms functional selectivity and biased agonism (Figure 2). Biased agonism, often used interchangeably with functional selectivity, refers to the selective activation of some, but not all, signaling pathways downstream of a receptor [17]. A biased response can occur at the level of the receptor or downstream of the receptor and involve tissue-specific factors, such as pharmacokinetics, molecular targets, binding affinities, efficacy, etc. We refer to true ligand bias as one that is limited to the ligand-receptor-transducer complex and results from the generation of a conformational state of the receptor that is stabilized by a given ligand or condition, which promotes interaction with specific transducers such as G-protein or β-arrestin, to evoke selective cellular signaling responses [17]. Thus, such biased signaling is a function of the conformation a receptor takes when interacting with a specific ligand as opposed to other ligands and will be manifest under different cellular conditions [3, 17].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of allosteric modulation. (A) In response to a balanced agonist bound to the orthosteric site, the activated receptor (R*) couples to and signals through both G protein-dependent and the β-arrestin-dependent pathways. (B) Allosteric binding at a site other than the orthosteric site causes a conformational change of the receptor (R#), which alters receptor function and leads to a specific subset of downstream signaling. (C) Membrane stretch serves as a form of allosteric modulation and is β-arrestin biased (Rβ#), activating β-arrestin–dependent pathways even in absence of the ligand.

Focus on β-arrestin Bias

The first descriptions of biased ligands were in muscarinic receptors, the α2 adrenergic receptor, and the adenylyl cyclase-activating polypeptide receptor [18–21], and a broad range of examples rapidly followed them. Bias mechanisms have been described between two different G proteins [22, 23], between β-arrestin-1 and -2 [24], and also between different states of the same receptor bound to different ligands [25, 26]. However, the most well described examples of biased ligands refer to selective G protein signaling versus β-arrestin-mediated signaling [27]. The angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) has been one of the most studied examples of biased signaling, where extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1 and 2 could be activated in either a G protein -dependent or β-arrestin-2-dependent manner [15]. In particular, it was demonstrated how an angiotensin II analog can activate the MAPK cascade without any effect on phosphatidylinositol turnover [15, 28].

G-protein-independent MAPK activation was described also for the β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR), and in particular, it was demonstrated how ICI118551 and propranolol, two inverse agonists for Gs stimulation, could induce ERK1/2 activation in a β-arrestin-dependent manner [14]. Later, a wide spectrum of βAR antagonists with different efficacy in activation of G protein and β-arrestins was tested. Among these, carvedilol was shown to be a weakly biased agonist for both β1- and β2ARs, as it was able to selectively activate the β-arrestin pathway with no effect on G protein signaling [29, 30]. Since βARs can exert a cardioprotective effect transactivating epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) through β-arrestin [12], the β-blockers carvedilol and alprenolol were shown to induce β-arrestin-dependent EGFR-transactivation as a possible mechanism for the cardioprotective effect of β-arrestin [30]. This is one of several examples demonstrating the potential benefit of developing β-arrestin-biased ligands as novel therapeutic agents.

Receptor Phosphorylation and the “Barcode Hypothesis”

An important concept in biased signaling is that conformational changes of the receptor allow different phosphorylation patterns of the cytoplasmic loops and C-terminal tail. Early evidence for this mechanism was shown in several studies on different GPCRs [31, 32]. In particular, it was demonstrated how β-arrestin displays different responses, depending on which class of GRKs phosphorylates the receptor. For the AT1R, following agonist stimulation or mechanical stretch, GRK-5 and -6 seem to be responsible for β-arrestin-dependent ERK activation [31, 33]. Direct confirmation of the “barcode hypothesis” used mass spectrometry proteomics to show that differences in phosphorylation pattern of the C-terminal tail of βAR determined the signaling activity of the ligand bound receptor [34].

Allosterism

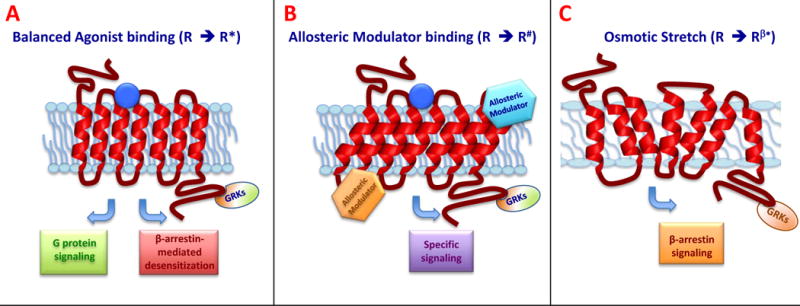

In addition to receptor conformations and phosphorylation profiles, biased signaling may be modulated by the actual site of ligand-receptor binding. Most ligands bind a receptor where its endogenous ligand binds, known as the orthosteric site. However, some ligands bind at a site different from the orthosteric site, called an allosteric site (Figure 3). Allosteric binding causes a conformational change of the receptor, which alters its function. Allosteric ligands can lead to biased agonism in two ways. First, they may act as biased ligands themselves and activate a specific subset of receptor-mediated pathways. Second, when an allosteric and orthosteric ligand are bound at the same time, the allosteric ligand may interact with the orthostatic site ligand and promote a specific subset of downstream signaling activation [35]. Allosteric agonism has been described over forty years ago, [36] and many allosteric modulators have been identified. An increasing number of studies have demonstrated the ability of GPCRs to dimerize or arrange as higher-order oligomers [37, 38], and this affects ligand binding and G protein-coupling [39, 40], may cause cross-activation or inhibition [41, 42], can influence downstream signaling [43], and can affect receptor internalization [44, 45].

Figure 3.

Examples of functional selectivity. GPCR functional selectivity refers to the activation of some, but not all, signaling pathways downstream of a receptor. Functional selectivity is affected by factors such as pharmacokinetics, target selectivity, receptor density, and ligand efficacy and can occur at or downstream of the receptor. True ligand bias is a subtype of functional selectivity and is limited to the ligand-receptor-transducer complex. A ligand or condition stabilizes a unique receptor conformation, which promotes interaction with specific transducers (e.g. G protein or β-arrestin) to evoke selective cellular signaling responses.

In recent years, a growing interest has emerged regarding the role of small molecules acting as allosteric modulators to stabilize specific conformations of G protein-coupled receptors. In particular, a class of single-domain antibodies isolated from the Camelid family, called nanobodies, was found to function as allosteric modulators of the β2AR, stabilizing a specific agonist-activated conformation [46]. Further studies demonstrated that nanobodies transiently expressed intracellularly, or “intrabodies,” could bind the intracellular domain and stabilize specific receptor conformations. Intrabodies show a variety of effects on cAMP accumulation and β-arrestin recruitment and can inhibit β2AR signaling [47]. Intrabodies could represent a novel and interesting tool to understand GPCR biology. Further studies are needed to fully understand the role of allosteric agonism in biased signaling and in new drug discovery.

Membrane Stretch

Membrane stretch caused by mechanical stimuli may be considered to be a form of allosteric modulation, as ligand binding at the orthosteric site is not required. Recently, AT1R activation by mechanical stretch of the receptor has been demonstrated [33, 48–50]. While the endogenous ligand, angiotensin II, and G protein recruitment may not be required, the recruitment of β-arrestin appears to be necessary to activate downstream signaling [33, 49], making mechanical stretch a β-arrestin biased phenomenon for the AT1R. A mutagenesis study suggested that mechanical stretch induces a conformational change of the AT1R [51], while using AT1R-β-arrestin chimeric receptors it was demonstrated that mechanical stretch induces a unique β-arrestin-conformational state of the AT1R that is distinct from either the wild type receptor or the G-protein bound AT1R [49].

BIAS ACROSS SEVERAL SYSTEMS

Cardiovascular System

Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor (AT1R)

One of the most studied GPCRs with respect to biased agonism is the AT1R, which holds great importance as a regulator of blood pressure and cardiac performance [52]. β–Arrestin signaling at the AT1R was clearly demonstrated by Wei et. al. using the angiotensin II analog 1 Sar, 4 Ile, 8 Ile-angiotensin II (SII) [15]. SII was shown to be a β-arrestin-biased ligand, unable to activate Gαq signaling (i.e. did not lead to increased DAG activity or IP3 levels) but could recruit β-arrestin-2 to the receptor, leading to receptor internalization and ERK activation in a G protein-dependent manner [15]. In an ex vivo study with cardiomyocytes, it was shown that both angiotensin II and SII led to positive inotropic effects [53]. Furthermore, these effects were not affected by inhibition of G protein mediated pathways via PKC. However, PKC did lead to a significant decrease in the positive effects caused by angiotensin [53]. This indicates that β-arrestin-biased ligands could play a significant physiological role. SII has also been shown to be involved in salt and water appetite [54], which is a main contributor to the symptoms of congestive heart failure. Unfortunately, SII has low receptor binding affinity [28], making it non-ideal for in vivo studies. This led to the development of the AT1R biased agonist TRV120027 [55]. This novel, biased agonist was shown to function as an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), as it exhibited decreased IP3 accumulation and decreased afterload in rats [55]. Both TRV120027 and TRV120023, another biased AT1R ligand, are able to effectively recruit β-arrestin to the AT1R and interestingly, induce a mild increase in contractility [55, 56]. In clinical practice, ARBs are often used in chronic heart failure due to their ability to reduce blood pressure and prevent adverse cardiac remodeling. However, in an acute heart failure exacerbation, ARBs are often not used, secondary to their hypotensive and reduced cardiac output effects [57].

TRV120027 has been explored in a phase I study in healthy volunteers and a phase IIa study in patients with stable systolic congestive heart failure, which showed it to be a well-tolerated medication with a short half-life. Subjects were noted to have reduced blood pressure as well [58, 59]. A phase IIb, randomized, double blind study called Blast-AHF is currently ongoing comparing the effects of TRV120027 with standard of care and placebo in acute heart failure patients [59].

As previously mentioned, the AT1R also functions as a mechanosensor, and the intracellular signaling of this function does not require AngII. Membrane stretch was shown to function as an allosteric modulator to selectively enhance β-arrestin biased signaling [49], making stretch activation of AT1R yet another important area of investigation for biased agonism at the AT1R receptor [48, 56, 60].

β-1 and -2 Adrenergic Receptors

β-adrenergic receptors (βARs) play a pivotal role in heart failure therapeutics. Agonists of β-adrenergic receptors are used as positive inotropes in the treatment of acute heart failure with depressed ejection function. β-Blockers, which are antagonists of these receptors, are one of the mainstays for the treatment of chronic heart failure, as they mediate cardioprotection [61]. β1AR makes up 70% of all cardiac βAR. As with the AT1R, β-arrestin-mediated signaling at β1AR has been known to lead to receptor desensitization [62]. As discussed previously, phosphorylation of the receptor by GRKs leads to β-arrestin recruitment to the receptor leading to desensitization, internalization, and signaling [63]. However, Noma et. al. were able to show that EGFR transactivation as a result of β1AR stimulation is a β–arrestin mediated signaling pathway in both in vitro and in vivo models in the heart [12]. Furthermore, it was shown that this transactivation of cardiac EGFRs has a cardioprotective role [12]. Therefore, a novel biased ligand that acts as a G protein antagonist but activates this β-arrestin-mediated pathway could potentiate further cardioprotective signals, as compared to traditional β–blockers [12].

Interestingly, GRK-5 and -6 have been shown to play a pivotal role in β1AR EGFR transactivation [12, 30]. When siRNA targeting GRK-5 or -6 was used, EGFR transactivation and downstream ERK signaling were lost in HEK293 cells. This signaling was maintained when siRNA targeted GRK-2 or -3 [12]. This notion led to a barcode hypothesis for biased agonism, which states that different GRKs establish a distinct phosphorylation barcode that recruits β-arrestin and regulates its downstream biased effects. In fact, a barcode has been established for the β2AR utilizing carvedilol as the β-arrestin biased ligand. In accordance with this hypothesis, they showed that carvedilol had a phosphorylation pattern that was distinct from isoproterenol, a balanced agonist [34]. Interestingly, it has been shown that carvedilol upregulates a subset of microRNAs in a β1AR dependent manner in human cells and mouse hearts [64]. Furthermore, while most β2AR agonists are balanced agonists, some do show β-arrestin-mediated signaling. Drake et. al. showed cyclopentylbutanephrine, ethylnorepinephrine, and isoetharine to be β-arrestin biased, and all three contained an ethyl substituent on the catecholamine α-carbon compared to the balanced agonists [65].

Hydroxyl Carboxylic Acid Receptor 2 (HCA2) is a 7TMR that couples through Gαi/Gαo and when stimulated, acts to lower triglycerides and raises high density lipoprotein levels. This receptor was previously referred to as GPR109A; however, it was recently discovered that the endogenous ligand is 3-hydroxybutyrate, which led to the receptor’s renaming [66]. In clinical practice, niacin is a commonly used agonist of this receptor. However, its use is significantly limited due to cutaneous flushing [67], which has recently been attributed to the recruitment of β–arrestin to the receptor and generation of arachidonate, leading to the undesired response of flushing [68]. However, it is the G protein mediated signaling that leads to lowering of serum free fatty acids [68]. There have been several novel partial agonists developed to lower lipids without the undesired cutaneous flushing [69, 70]. It should be noted that these molecules are not biased agonists, and in fact, as further research is conducted, a biased ligand may be superior to a partial agonist.

Urotensin Receptor (UT)

The UT receptor is a GPCR that, through its vasoactive properties and distribution, has been implicated in the control of hypertension, heart failure, and cardiac fibrosis [71]. However, the therapeutic use for agonists of the receptor has been limited due to unexpected physiological effects. For example, the effects of urotensin II vary on the species or tissue being investigated [72] and can either lead to a vasodilatory effect or a cardiostimulant effect [73, 74]. Recently it was shown that these varied cellular responses could be a result of bias towards either the G protein pathways or β-arrestin-mediated signaling in the various tissues [75].

Adenosine A1 Receptor

Another example of allosteric modulation leading to signaling is seen with the A1 receptor [76]. Agonist stimulation at this receptor has been implicated in treatment of several cardiovascular diseases including ischemia reperfusion injury and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia [77]. However, translation of adenosine A1 receptor agonists to clinical medicine has been limited because of the on target adverse effects such as bradycardia and hypotension [78, 79]. Therefore, it is important to better understand and characterize the mode of action of several of these allosteric modulators, and in fact, several groups have been working on better elucidating the activation of selective signaling by these ligands [80–83]. For example, preliminary work with VCP746, a hybrid molecule of adenosine linked to an allosteric modulator, showed that it led to cardioprotection with minimal effects on blood pressure and heart rate [84].

Proteinase-Activated Receptor 1

PAR-1 is activated by thrombin, which is an inflammatory factor that mediates contraction of endothelial cells leading to increased permeability of the vascular endothelium and vascular edema. Activation by thrombin also leads to increased clotting [85]. Several antagonists to PAR-1 and PAR-4 have been developed; however, all of these lead to not only vascular edema inhibition but also an increased risk of bleeding [86, 87]. Therefore, it would be desirable to selectively inhibit PAR signaling in the endothelium without inhibiting the hemostasis effects of thrombin. Barrier permeability is likely Gαi/o mediated, whereas calcium mobilization is Gαq mediated [88]. McLaughlin et al. were able to show functional selectivity of G protein signaling by agonist peptides at PAR-1 in an endothelial cell line, which could be therapeutically used to alter the effects of thrombin on the endothelium vs. increased bleeding [85].

Ghrelin Receptor (GHSR1α)

Obesity is dominant co-morbidity to cardiovascular disease. Ghrelin is known to play a pivotal role in energy homeostasis and reward behavior, and its receptor, GHSR1α, is a recognized target for treating obesity and addiction. GHSR1α is a GPCR whose activation leads to increased appetite through Gq and Gi activation upon stimulation with ghrelin [89, 90]. The signaling cascades downstream of GHSR1 are not well understood, however it is appreciated that GHSR1α does lead to activation of MAPK/ERK and also activates the small GTPase RhoA [91, 92]. Recently, Evron et al. showed that while GHSR1α-mediated ERK signaling is balanced between G protein and β-arrestin signaling, there is a significant role for β-arrestin in RhoA activation [93]. While this mechanism and its effects on appetite and addiction need to be more clearly elucidated, it provides a framework for the development of GHSR1a ligands for the selective activation of GHSR1a [93].

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor (GLP-1R)

The GLP-1R is a focus in new diabetic therapy since the GLP-1 hormone potentiates insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells. It has been shown that GLP-1 stimulates ERK1/2 by two distinct pathways. By using pharmacological inhibitors, β–arrestin siRNA, and pancreatic islet cells from β–arrestin-1 KO mice, it was shown that β–arrestin-dependent pathway produces a late ERK activity, while PKA-dependent pathway produces a rapid and transient ERK activity [94]. Interestingly, it has been shown that β-arrestin-1 mediates the effects of GLP-1 and leads to increased cAMP production and hence insulin secretion from β cells [95]. This again demonstrates the potential for the development of a β-arrestin-biased ligand with enhanced therapeutic efficacy.

As outlined here and summarized in Table 1, there is a wide range of G protein coupled receptors in the cardiovascular system that show biased signaling. This phenomenon offers significant opportunity for drug discovery and improved clinical outcomes in patients.

Table 1.

Examples of G protein-coupled receptors in the cardiovascular system which show G protein or β-arrestin biased signaling.

| Receptor | Biased ligand | β-Arrestin pathway | G protein pathway | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor | SII, TRV120027, TRV120023 | + | − | [15, 55, 56] |

| β Adrenergic Receptors | Carvedilol, cyclopentylbutanephrine, ethylnorepinephrine, isoetharine | + | − | [34, 65] |

| Hydroxyl Carboxylic Acid Receptor | Pyrazole, MK-0354 | − | + | [69, 70] |

| Urotensin Receptor | [Orn8]UII, [Orn5]URP, urantide | + | − | [75] |

| Proteinase Activated Receptor 1 | Synthetic peptides (e.g. TFLLRNKPDK, SFLLRN- CONH2, SLIGKV) |

− | + | [85] |

| GHSR1a Receptor | Unknown | − | − | [93] |

| GLP-1 Receptor | Unknown | − | − | [94–96] |

| Allosteric Modulator | ||||

| Adenosine A1 Receptor | VCP746, 2-amino-3-benzoylthiophene derivatives | − | + | [80–84] |

| Ligand Independent Allosteric Modulator | ||||

| Angiotensin Type 1 Receptor | Membrane stretch | + | − | [49] |

Nervous System

μ Opioid Receptor

Morphine is a commonly used for analgesic, as it acts at the μ opioid receptor, which is a GPCR that is highly expressed both in the central nervous system and in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. While morphine is very effective, its use is often limited by GI side effects including nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Furthermore, use of morphine can lead to respiratory suppression, sedation, tolerance, and addiction [96]. It has been shown that in β-arrestin-2 KO mice, morphine leads to enhanced and prolonged analgesia with reduced desensitization [97]. Furthermore, constipation and respiratory depression were also reduced in these mice as compared to wildtype mice [98]. Therefore, β-arrestin-mediated signaling leads to distinct mechanisms that increase the side effect profile of a balanced agonist at the μ receptor.

Discovery of biased agonism at the μ opioid receptor led to the development of TRV130, an intravenous G protein-biased ligand, which shows potent analgesic effects while causing less GI dysfunction and respiratory suppression compared to morphine in mice [96]. TRV130 has undergone phase 1 [99] and phase 2a/2b studies, which showed a significant reduction in pain intensity after moderate to severe postoperative pain [100].

TRV734 has also been developed as an oral agent that acts similar to TRV130 at the μ opioid receptor. A phase 1 study was completed, which showed good analgesic effects with mild to moderate adverse effects. It was also shown to be generally safe and well-tolerated in a multiple ascending dose study [100].

Delta Opioid Receptor

Delta opioid receptors are targets for treatment of migraine [101], Parkinson’s disease [102], and neuropathic pain [103]. While delta opioid receptor activation does not lead to addiction [104], it does lead to seizures, limiting the use of balanced agonists [105]. However, it has been noted that the lowered seizure threshold is a result of β-arrestin-mediated signaling [106]. TRV250 has been identified as a G protein-biased agonist at the delta receptor, with the goal of exploiting activation at the delta opioid receptor for treatment of migraines without the associated lowered seizure threshold [100].

Kappa Opioid Receptor

The kappa opioid receptor is another GPCR where a balanced agonist leads to analgesia with low abuse potential, but its activation is associated with severe side effects including anhedonia, hallucinations, and dysphoria [107, 108]. This side effect profile is a result of kappa opioid receptor activation inducing p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases through mediation by β-arrestin-2 [109]. White et al. were able to recently utilize a G protein-biased ligand that crosses the blood-brain barrier to further explore this [100]. They showed that this ligand, RB-64 (22-thiocynatasalvinorin) induces analgesia without having an effect on sedation, anhedonia, or motor coordination [100, 110]. This provides yet another example for the therapeutic potential of a biased ligand with excellent efficacy and a safer side effect profile.

Sphingosine 1 Phosphate Type 1 Receptor (S1P1)

The sphingosine 1-phosphate type 1 (S1P1) receptor is involved in the regulation of lymphocyte trafficking, vascular permeability, and angiogenesis upon activation by sphingosine 1 phosphate (S1P) [111]. FTY720 is an immune modulator that acts at the S1P1 receptor and is currently undergoing phase III clinical trials for multiple sclerosis and allograft rejection [112–114]. FTY720 is known to act as an agonist of S1P1 receptor leading to similar effects as S1P, including receptor internalization into the endosomal pathway [115, 116]. However, whereas stimulation by S1P leads to receptor recycling to the plasma membrane, stimulation with FTY720 actually promotes to a unique ubiquitination profile that leads to rapid degradation of S1P1 receptor. Interestingly, siRNA for β-arrestin-1 and -2 in HEK 293 cells prevented FTY720 induced degradation, suggesting that β-arrestin-dependent receptor internalization is required for S1P1 receptor degradation upon stimulation with FTY720, and it is this β-arrestin-biased pathway that may be responsible for the therapeutic profile of FTY720 as an anti-angiogenic and immunosuppressant [117].

Endocrine System

Parathyroid Hormone Receptor (PTH1R)

Parathyroid hormone is a peptide hormone that acts at the PTH1R to mediate calcium and phosphate homeostasis. The synthetic fragment of human PTH, PTH (1-34), acts similarly to full length PTH and is used clinically to treat osteoporosis. As a balanced agonist, PTH (1-34) leads to Gαs and Gαq activation at the PTH1R [118]. This results in increased osteoblasts and new bone deposition. However, activation by PTH (1-34) also leads to increased activity of osteoclasts and bone resorption. The fact that the anabolic and catabolic effects of PTH (1-34) are linked, limits its therapeutic effectiveness [118–120]. Gesty-Palmer et al. investigated the use of PTH-βarr, a β-arrestin-biased agonist, which activates β-arrestin but not G protein signaling. PTH-βarr led to anabolic bone formation but not bone resorption in mice and is another example of the potential for β-arrestin biased ligands to enhance therapeutic specificity [121].

Oxytocin Receptor

Prolonged oxytocin exposure leads to desensitization at the oxytocin receptor, which may lead to dysfunctional labor, uterine atony, and postpartum hemorrhage [122, 123]. This desensitization at the oxytocin receptor was shown to be a result of β-arrestin-1 and -2 activation in mice, since β-arrestin-1 and -2 KO mice have greater uterine contractions in response to oxytocin stimulation [124]. Therefore, the development of a biased agonist that preferentially activates G-protein signaling at the oxytocin receptor and not β-arrestin could lead to further therapeutic options for dysfunctional labor and uterine atony [124].

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

As the largest family of receptors involved in nearly every physiologic process, GPCRs continue to be the focus of extensive basic and clinical research. These efforts have expanded initial signaling theories into more elaborate and complex models. Most notably, the discovery of β-arrestin biased agonism has significantly enhanced our understanding of the complexity of GPCR signaling. Already, the ability to target a subset of a receptor’s signaling response has led to therapeutically important drugs and clinical trials. In this review, we discussed several promising investigational drugs that have translated basic science work into clinical developments including TRV120027 in the treatment of heart failure and the use of TRV734, TRV130, and TRV250 for better treatment of pain with fewer side effects. β-arrestin-biased agonism is also promising in developing therapeutics with less on-target signaling. While biased agonism has been demonstrated in a multitude of different GPCRs important in various physiologic processes, the development of pharmaceutical applications for many is yet to be determined.

Selective GPCR signaling itself has proven to be multidimensional, as different mechanisms of bias related to ligand-receptor interactions, receptor conformations, receptor phosphorylation patterns, allosteric binding sites, and even receptor independent bias through membrane stretch have been demonstrated. As more of these pathways are discovered, it will become even more pertinent to identify universal nomenclature to better understand and categorize these findings. It is almost certain that additional mechanisms of functional selectivity and β-arrestin bias will emerge, providing further tools in developing specifically targeted medications with improved side effect and safety profiles.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Robert Lefkowitz, Dean Staus, Laura Wingler, and Sudarshan Rajagopal for their insightful comments and thoughtful discussion.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health grants HL56687 and HL75443 to HAR; National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant HD000850-30 to RDT.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

Dr. Rockman is a scientific cofounder for Trevena Inc, a company that is developing G protein–coupled receptor–targeted drugs. The other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.Lefkowitz RJ. Historical review: a brief history and personal retrospective of seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:413–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gudermann T, Nurnberg B, Schultz G. Receptors and G proteins as primary components of transmembrane signal transduction. Part 1. G-protein-coupled receptors: structure and function. J Mol Med (Berl) 1995;73:51–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00270578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Violin JD, Crombie AL, Soergel DG, Lark MW. Biased ligands at G-protein-coupled receptors: promise and progress. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wisler JW, Xiao K, Thomsen AR, Lefkowitz RJ. Recent developments in biased agonism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;27:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neves SR, Ram PT, Iyengar R. G protein pathways. Science. 2002;296:1636–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1071550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitcher JA, Freedman NJ, Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:653–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Transduction of receptor signals by beta-arrestins. Science. 2005;308:512–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1109237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drake MT, Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Trafficking of G protein-coupled receptors. Circ Res. 2006;99:570–82. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000242563.47507.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins during receptor desensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:9–18. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore CA, Milano SK, Benovic JL. Regulation of receptor trafficking by GRKs and arrestins. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:451–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptor signaling through beta-arrestin. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:cm10. doi: 10.1126/stke.2005/308/cm10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noma T, Lemaire A, Naga Prasad SV, Barki-Harrington L, Tilley DG, Chen J, Le Corvoisier P, Violin JD, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ, Rockman HA. Beta-arrestin-mediated beta1-adrenergic receptor transactivation of the EGFR confers cardioprotection. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2445–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI31901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shenoy SK, Drake MT, Nelson CD, Houtz DA, Xiao K, Madabushi S, Reiter E, Premont RT, Lichtarge O, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1261–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azzi M, Charest PG, Angers S, Rousseau G, Kohout T, Bouvier M, Pineyro G. Beta-arrestin-mediated activation of MAPK by inverse agonists reveals distinct active conformations for G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11406–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936664100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei H, Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Karnik SS, Hunyady L, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Independent beta-arrestin 2 and G protein-mediated pathways for angiotensin II activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10782–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strachan RT, Sun JP, Rominger DH, Violin JD, Ahn S, Rojas Bie Thomsen A, Zhu X, Kleist A, Costa T, Lefkowitz RJ. Divergent transducer-specific molecular efficacies generate biased agonism at a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14211–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.548131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onaran HO, Rajagopal S, Costa T. What is biased efficacy? Defining the relationship between intrinsic efficacy and free energy coupling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:639–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eason MG, Jacinto MT, Liggett SB. Contribution of ligand structure to activation of alpha 2-adrenergic receptor subtype coupling to Gs. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:696–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spengler D, Waeber C, Pantaloni C, Holsboer F, Bockaert J, Seeburg PH, Journot L. Differential signal transduction by five splice variants of the PACAP receptor. Nature. 1993;365:170–5. doi: 10.1038/365170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher A, Heldman E, Gurwitz D, Haring R, Barak D, Meshulam H, Marciano D, Brandeis R, Pittel Z, Segal M, et al. Selective signaling via unique M1 muscarinic agonists. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;695:300–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurwitz D, Haring R, Heldman E, Fraser CM, Manor D, Fisher A. Discrete activation of transduction pathways associated with acetylcholine m1 receptor by several muscarinic ligands. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;267:21–31. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gesty-Palmer D, Chen M, Reiter E, Ahn S, Nelson CD, Wang S, Eckhardt AE, Cowan CL, Spurney RF, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Distinct beta-arrestin- and G protein-dependent pathways for parathyroid hormone receptor-stimulated ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10856–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maillet EL, Pellegrini N, Valant C, Bucher B, Hibert M, Bourguignon JJ, Galzi JL. A novel, conformation-specific allosteric inhibitor of the tachykinin NK2 receptor (NK2R) with functionally selective properties. FASEB J. 2007;21:2124–34. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7683com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann C, Ziegler N, Reiner S, Krasel C, Lohse MJ. Agonist-selective, receptor-specific interaction of human P2Y receptors with beta-arrestin-1 and -2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30933–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801472200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohout TA, Nicholas SL, Perry SJ, Reinhart G, Junger S, Struthers RS. Differential desensitization, receptor phosphorylation, beta-arrestin recruitment, and ERK1/2 activation by the two endogenous ligands for the CC chemokine receptor 7. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23214–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402125200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zidar DA, Violin JD, Whalen EJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Selective engagement of G protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) encodes distinct functions of biased ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9649–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajagopal S, Ahn S, Rominger DH, Gowen-MacDonald W, Lam CM, Dewire SM, Violin JD, Lefkowitz RJ. Quantifying ligand bias at seven-transmembrane receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:367–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.072801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holloway AC, Qian H, Pipolo L, Ziogas J, Miura S, Karnik S, Southwell BR, Lew MJ, Thomas WG. Side-chain substitutions within angiotensin II reveal different requirements for signaling, internalization, and phosphorylation of type 1A angiotensin receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:768–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wisler JW, DeWire SM, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Drake MT, Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. A unique mechanism of beta-blocker action: carvedilol stimulates beta-arrestin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16657–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707936104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim IM, Tilley DG, Chen J, Salazar NC, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Rockman HA. Beta-blockers alprenolol and carvedilol stimulate beta-arrestin-mediated EGFR transactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14555–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804745105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J, Ahn S, Ren XR, Whalen EJ, Reiter E, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ. Functional antagonism of different G protein-coupled receptor kinases for beta-arrestin-mediated angiotensin II receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1442–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409532102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butcher AJ, Prihandoko R, Kong KC, McWilliams P, Edwards JM, Bottrill A, Mistry S, Tobin AB. Differential G-protein-coupled receptor phosphorylation provides evidence for a signaling bar code. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11506–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.154526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakesh K, Yoo B, Kim IM, Salazar N, Kim KS, Rockman HA. Beta-Arrestin-biased agonism of the angiotensin receptor induced by mechanical stress. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra46. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nobles KN, Xiao K, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lam CM, Rajagopal S, Strachan RT, Huang TY, Bressler EA, Hara MR, Shenoy SK, Gygi SP, Lefkowitz RJ. Distinct phosphorylation sites on the beta2-adrenergic receptor establish a barcode that encodes differential functions of beta-arrestin. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khajehali E, Malone DT, Glass M, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Leach K. Biased agonism and biased allosteric modulation at the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1124/mol.115.099192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. On the Nature of Allosteric Transitions: A plausible model. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milligan G. G protein-coupled receptor dimerization: function and ligand pharmacology. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1–7. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.000497.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palczewski K. Oligomeric forms of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Asmar L, Springael JY, Ballet S, Andrieu EU, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Evidence for negative binding cooperativity within CCR5-CCR2b heterodimers. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:460–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baneres JL, Parello J. Structure-based analysis of GPCR function: evidence for a novel pentameric assembly between the dimeric leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and the G-protein. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:815–29. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carrillo JJ, Pediani J, Milligan G. Dimers of class A G protein-coupled receptors function via agonist-mediated trans-activation of associated G proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42578–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barki-Harrington L, Luttrell LM, Rockman HA. Dual inhibition of beta-adrenergic and angiotensin II receptors by a single antagonist: a functional role for receptor-receptor interaction in vivo. Circulation. 2003;108:1611–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000092166.30360.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rocheville M, Lange DC, Kumar U, Patel SC, Patel RC, Patel YC. Receptors for dopamine and somatostatin: formation of hetero-oligomers with enhanced functional activity. Science. 2000;288:154–7. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavoie C, Mercier JF, Salahpour A, Umapathy D, Breit A, Villeneuve LR, Zhu WZ, Xiao RP, Lakatta EG, Bouvier M, Hebert TE. Beta 1/beta 2-adrenergic receptor heterodimerization regulates beta 2-adrenergic receptor internalization and ERK signaling efficacy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35402–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ellis J, Pediani JD, Canals M, Milasta S, Milligan G. Orexin-1 receptor-cannabinoid CB1 receptor heterodimerization results in both ligand-dependent and -independent coordinated alterations of receptor localization and function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38812–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Fung JJ, Pardon E, Casarosa P, Chae PS, Devree BT, Rosenbaum DM, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Schnapp A, Konetzki I, Sunahara RK, Gellman SH, Pautsch A, Steyaert J, Weis WI, Kobilka BK. Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the beta(2) adrenoceptor. Nature. 2011;469:175–80. doi: 10.1038/nature09648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staus DP, Wingler LM, Strachan RT, Rasmussen SG, Pardon E, Ahn S, Steyaert J, Kobilka BK, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of beta2-adrenergic receptor function by conformationally selective single-domain intrabodies. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;85:472–81. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.089516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schleifenbaum J, Kassmann M, Szijarto IA, Hercule HC, Tano JY, Weinert S, Heidenreich M, Pathan AR, Anistan YM, Alenina N, Rusch NJ, Bader M, Jentsch TJ, Gollasch M. Stretch-activation of angiotensin II type 1a receptors contributes to the myogenic response of mouse mesenteric and renal arteries. Circ Res. 2014;115:263–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.302882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang W, Strachan RT, Lefkowitz RJ, Rockman HA. Allosteric modulation of beta-arrestin-biased angiotensin II type 1 receptor signaling by membrane stretch. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:28271–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.585067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zou Y, Akazawa H, Qin Y, Sano M, Takano H, Minamino T, Makita N, Iwanaga K, Zhu W, Kudoh S, Toko H, Tamura K, Kihara M, Nagai T, Fukamizu A, Umemura S, Iiri T, Fujita T, Komuro I. Mechanical stress activates angiotensin II type 1 receptor without the involvement of angiotensin II. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:499–506. doi: 10.1038/ncb1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yasuda N, Miura S, Akazawa H, Tanaka T, Qin Y, Kiya Y, Imaizumi S, Fujino M, Ito K, Zou Y, Fukuhara S, Kunimoto S, Fukuzaki K, Sato T, Ge J, Mochizuki N, Nakaya H, Saku K, Komuro I. Conformational switch of angiotensin II type 1 receptor underlying mechanical stress-induced activation. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:179–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Higuchi S, Ohtsu H, Suzuki H, Shirai H, Frank GD, Eguchi S. Angiotensin II signal transduction through the AT1 receptor: novel insights into mechanisms and pathophysiology. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:417–28. doi: 10.1042/CS20060342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Stiber JA, Rosenberg PB, Premont RT, Coffman TM, Rockman HA, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin2-mediated inotropic effects of the angiotensin II type 1A receptor in isolated cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16284–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607583103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Daniels D, Yee DK, Faulconbridge LF, Fluharty SJ. Divergent behavioral roles of angiotensin receptor intracellular signaling cascades. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5552–60. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Violin JD, DeWire SM, Yamashita D, Rominger DH, Nguyen L, Schiller K, Whalen EJ, Gowen M, Lark MW. Selectively engaging beta-arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:572–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim KS, Abraham D, Williams B, Violin JD, Mao L, Rockman HA. beta-Arrestin-biased AT1R stimulation promotes cell survival during acute cardiac injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H1001–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00475.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Violin JD, Soergel DG, Boerrigter G, Burnett JC, Jr, Lark MW. GPCR biased ligands as novel heart failure therapeutics. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2013;23:242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soergel DG, Subach RA, Cowan CL, Violin JD, Lark MW. First clinical experience with TRV027: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53:892–9. doi: 10.1002/jcph.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Felker GM, Butler J, Collins SP, Cotter G, Davison BA, Ezekowitz JA, Filippatos G, Levy PD, Metra M, Ponikowski P, Soergel DG, Teerlink JR, Violin JD, Voors AA, Pang PS. Heart failure therapeutics on the basis of a biased ligand of the angiotensin-2 type 1 receptor. Rationale and design of the BLAST-AHF study (Biased Ligand of the Angiotensin Receptor Study in Acute Heart Failure) JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barauna VG, Magalhaes FC, Campos LC, Reis RI, Kunapuli SP, Costa-Neto CM, Miyakawa AA, Krieger JE. Shear stress-induced Ang II AT1 receptor activation: G-protein dependent and independent mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434:647–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajagopal S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ. Teaching old receptors new tricks: biasing seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:373–86. doi: 10.1038/nrd3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ, Rockman HA. Functional consequences of altering myocardial adrenergic receptor signaling. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:237–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptors. III. New roles for receptor kinases and beta-arrestins in receptor signaling and desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18677–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim IM, Wang Y, Park KM, Tang Y, Teoh JP, Vinson J, Traynham CJ, Pironti G, Mao L, Su H, Johnson JA, Koch WJ, Rockman HA. Beta-arrestin1-biased beta1-adrenergic receptor signaling regulates microRNA processing. Circ Res. 2014;114:833–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drake MT, Violin JD, Whalen EJ, Wisler JW, Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. beta-arrestin-biased agonism at the beta2-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5669–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708118200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rahman M, Muhammad S, Khan MA, Chen H, Ridder DA, Muller-Fielitz H, Pokorna B, Vollbrandt T, Stolting I, Nadrowitz R, Okun JG, Offermanns S, Schwaninger M. The beta-hydroxybutyrate receptor HCA2 activates a neuroprotective subset of macrophages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3944. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bodor ET, Offermanns S. Nicotinic acid: an old drug with a promising future. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S68–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walters RW, Shukla AK, Kovacs JJ, Violin JD, DeWire SM, Lam CM, Chen JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Whalen EJ, Lefkowitz RJ. beta-Arrestin1 mediates nicotinic acid-induced flushing, but not its antilipolytic effect, in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1312–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI36806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Z, Blad CC, van der Sluis RJ, de Vries H, Van Berkel TJ, Ijzerman AP, Hoekstra M. Effects of pyrazole partial agonists on HCA(2) -mediated flushing and VLDL-triglyceride levels in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:818–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Semple G, Skinner PJ, Gharbaoui T, Shin YJ, Jung JK, Cherrier MC, Webb PJ, Tamura SY, Boatman PD, Sage CR, Schrader TO, Chen R, Colletti SL, Tata JR, Waters MG, Cheng K, Taggart AK, Cai TQ, Carballo-Jane E, Behan DP, Connolly DT, Richman JG. 3-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-1,4,5,6-tetrahydro-cyclopentapyrazole (MK-0354): a partial agonist of the nicotinic acid receptor, G-protein coupled receptor 109a, with antilipolytic but no vasodilatory activity in mice. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5101–8. doi: 10.1021/jm800258p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ong KL, Lam KS, Cheung BM. Urotensin II: its function in health and its role in disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:65–75. doi: 10.1007/s10557-005-6899-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Douglas SA. Human urotensin-II as a novel cardiovascular target: ‘heart’ of the matter or simply a fishy ‘tail’? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Katano Y, Ishihata A, Aita T, Ogaki T, Horie T. Vasodilator effect of urotensin II, one of the most potent vasoconstricting factors, on rat coronary arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;402:R5–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MacLean MR, Alexander D, Stirrat A, Gallagher M, Douglas SA, Ohlstein EH, Morecroft I, Polland K. Contractile responses to human urotensin-II in rat and human pulmonary arteries: effect of endothelial factors and chronic hypoxia in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:201–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brule C, Perzo N, Joubert JE, Sainsily X, Leduc R, Castel H, Prezeau L. Biased signaling regulates the pleiotropic effects of the urotensin II receptor to modulate its cellular behaviors. FASEB J. 2014;28:5148–62. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-249771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bruns RF, Fergus JH. Allosteric enhancement of adenosine A1 receptor binding and function by 2-amino-3-benzoylthiophenes. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;38:939–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Valant C, Aurelio L, Urmaliya VB, White P, Scammells PJ, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Delineating the mode of action of adenosine A1 receptor allosteric modulators. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:444–55. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.064568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Donato M, Gelpi RJ. Adenosine and cardioprotection during reperfusion--an overview. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;251:153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang Z, Cerniway RJ, Byford AM, Berr SS, French BA, Matherne GP. Cardiac overexpression of A1-adenosine receptor protects intact mice against myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H949–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00741.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aurelio L, Christopoulos A, Flynn BL, Scammells PJ, Sexton PM, Valant C. The synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-amino-4,5,6,7,8,9-hexahydrocycloocta[b]thiophenes as allosteric modulators of the A1 adenosine receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:3704–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aurelio L, Valant C, Figler H, Flynn BL, Linden J, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Scammells PJ. 3- and 6-Substituted 2-amino-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[2,3-c]pyridines as A1 adenosine receptor allosteric modulators and antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:7353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aurelio L, Valant C, Flynn BL, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Scammells PJ. Allosteric modulators of the adenosine A1 receptor: synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of 4-substituted 2-amino-3-benzoylthiophenes. J Med Chem. 2009;52:4543–7. doi: 10.1021/jm9002582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Valant C, Aurelio L, Devine SM, Ashton TD, White JM, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Scammells PJ. Synthesis and characterization of novel 2-amino-3-benzoylthiophene derivatives as biased allosteric agonists and modulators of the adenosine A(1) receptor. J Med Chem. 2012;55:2367–75. doi: 10.1021/jm201600e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Valant C, May LT, Aurelio L, Chuo CH, White PJ, Baltos JA, Sexton PM, Scammells PJ, Christopoulos A. Separation of on-target efficacy from adverse effects through rational design of a bitopic adenosine receptor agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:4614–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320962111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McLaughlin JN, Shen L, Holinstat M, Brooks JD, Dibenedetto E, Hamm HE. Functional selectivity of G protein signaling by agonist peptides and thrombin for the protease-activated receptor-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25048–59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Andrade-Gordon P, Derian CK, Maryanoff BE, Zhang HC, Addo MF, Cheung W, Damiano BP, D’Andrea MR, Darrow AL, de Garavilla L, Eckardt AJ, Giardino EC, Haertlein BJ, McComsey DF. Administration of a potent antagonist of protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) attenuates vascular restenosis following balloon angioplasty in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hollenberg MD, Saifeddine M. Proteinase-activated receptor 4 (PAR4): activation and inhibition of rat platelet aggregation by PAR4-derived peptides. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;79:439–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coughlin SR. Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature. 2000;407:258–64. doi: 10.1038/35025229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Holst B, Holliday ND, Bach A, Elling CE, Cox HM, Schwartz TW. Common structural basis for constitutive activity of the ghrelin receptor family. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53806–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mokrosinski J, Frimurer TM, Sivertsen B, Schwartz TW, Holst B. Modulation of constitutive activity and signaling bias of the ghrelin receptor by conformational constraint in the second extracellular loop. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33488–502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.383240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Camina JP. Cell biology of the ghrelin receptor. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:65–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sivertsen B, Lang M, Frimurer TM, Holliday ND, Bach A, Els S, Engelstoft MS, Petersen PS, Madsen AN, Schwartz TW, Beck-Sickinger AG, Holst B. Unique interaction pattern for a functionally biased ghrelin receptor agonist. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:20845–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.173237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Evron T, Peterson SM, Urs NM, Bai Y, Rochelle LK, Caron MG, Barak LS. G Protein and beta-arrestin signaling bias at the ghrelin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:33442–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.581397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Quoyer J, Longuet C, Broca C, Linck N, Costes S, Varin E, Bockaert J, Bertrand G, Dalle S. GLP-1 mediates antiapoptotic effect by phosphorylating Bad through a beta-arrestin 1-mediated ERK1/2 activation in pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1989–2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sonoda N, Imamura T, Yoshizaki T, Babendure JL, Lu JC, Olefsky JM. Beta-Arrestin-1 mediates glucagon-like peptide-1 signaling to insulin secretion in cultured pancreatic beta cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6614–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710402105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.DeWire SM, Yamashita DS, Rominger DH, Liu G, Cowan CL, Graczyk TM, Chen XT, Pitis PM, Gotchev D, Yuan C, Koblish M, Lark MW, Violin JD. A G protein-biased ligand at the mu-opioid receptor is potently analgesic with reduced gastrointestinal and respiratory dysfunction compared with morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:708–17. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Lin FT, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Mu-opioid receptor desensitization by beta-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature. 2000;408:720–3. doi: 10.1038/35047086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Raehal KM, Walker JK, Bohn LM. Morphine side effects in beta-arrestin 2 knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1195–201. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Soergel DG, Subach RA, Burnham N, Lark MW, James IE, Sadler BM, Skobieranda F, Violin JD, Webster LR. Biased agonism of the mu-opioid receptor by TRV130 increases analgesia and reduces on-target adverse effects versus morphine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy volunteers. Pain. 2014;155:1829–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.White KL, Robinson JE, Zhu H, DiBerto JF, Polepally PR, Zjawiony JK, Nichols DE, Malanga CJ, Roth BL. The G protein-biased kappa-opioid receptor agonist RB-64 is analgesic with a unique spectrum of activities in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;352:98–109. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.216820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pradhan AA, Smith ML, Zyuzin J, Charles A. delta-Opioid receptor agonists inhibit migraine-related hyperalgesia, aversive state and cortical spreading depression in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:2375–84. doi: 10.1111/bph.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mabrouk OS, Volta M, Marti M, Morari M. Stimulation of delta opioid receptors located in substantia nigra reticulata but not globus pallidus or striatum restores motor activity in 6-hydroxydopamine lesioned rats: new insights into the role of delta receptors in parkinsonism. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1647–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Nozaki C, Nadal X, Hever XC, Weibel R, Matifas A, Reiss D, Filliol D, Nassar MA, Wood JN, Maldonado R, Kieffer BL. Genetic ablation of delta opioid receptors in nociceptive sensory neurons increases chronic pain and abolishes opioid analgesia. Pain. 2011;152:1238–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hudzik TJ, Pietras MR, Caccese R, Bui KH, Yocca F, Paronis CA, Swedberg MD. Effects of the delta opioid agonist AZD2327 upon operant behaviors and assessment of its potential for abuse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;124:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Broom DC, Nitsche JF, Pintar JE, Rice KC, Woods JH, Traynor JR. Comparison of receptor mechanisms and efficacy requirements for delta-agonist-induced convulsive activity and antinociception in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:723–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pradhan AA, Befort K, Nozaki C, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL. The delta opioid receptor: an evolving target for the treatment of brain disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:581–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pfeiffer A, Brantl V, Herz A, Emrich HM. Psychotomimesis mediated by kappa opiate receptors. Science. 1986;233:774–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3016896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tejeda HA, Counotte DS, Oh E, Ramamoorthy S, Schultz-Kuszak KN, Backman CM, Chefer V, O’Donnell P, Shippenberg TS. Prefrontal cortical kappa-opioid receptor modulation of local neurotransmission and conditioned place aversion. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1770–9. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bruchas MR, Chavkin C. Kinase cascades and ligand-directed signaling at the kappa opioid receptor. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210:137–47. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1806-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yan F, Bikbulatov RV, Mocanu V, Dicheva N, Parker CE, Wetsel WC, Mosier PD, Westkaemper RB, Allen JA, Zjawiony JK, Roth BL. Structure-based design, synthesis, and biochemical and pharmacological characterization of novel salvinorin A analogues as active state probes of the kappa-opioid receptor. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6898–908. doi: 10.1021/bi900605n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chalfant CE, Spiegel S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and ceramide 1-phosphate: expanding roles in cell signaling. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4605–12. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kappos L, Antel J, Comi G, Montalban X, O’Connor P, Polman CH, Haas T, Korn AA, Karlsson G, Radue EW, Group FDS. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1124–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Quackenbush E, Xie J, Milligan J, Thornton R, Shei GJ, Card D, Keohane C, Rosenbach M, Hale J, Lynch CL, Rupprecht K, Parsons W, Rosen H. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296:346–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhou PJ, Wang H, Shi GH, Wang XH, Shen ZJ, Xu D. Immunomodulatory drug FTY720 induces regulatory CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157:40–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Graler MH, Goetzl EJ. The immunosuppressant FTY720 down-regulates sphingosine 1-phosphate G-protein-coupled receptors. FASEB J. 2004;18:551–3. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0910fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liu CH, Thangada S, Lee MJ, Van Brocklyn JR, Spiegel S, Hla T. Ligand-induced trafficking of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor EDG-1. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1179–90. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Oo ML, Thangada S, Wu MT, Liu CH, Macdonald TL, Lynch KR, Lin CY, Hla T. Immunosuppressive and anti-angiogenic sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 agonists induce ubiquitinylation and proteasomal degradation of the receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9082–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hock JM, Gera I. Effects of continuous and intermittent administration and inhibition of resorption on the anabolic response of bone to parathyroid hormone. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:65–72. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dobnig H, Turner RT. Evidence that intermittent treatment with parathyroid hormone increases bone formation in adult rats by activation of bone lining cells. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3632–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Qin L, Raggatt LJ, Partridge NC. Parathyroid hormone: a double-edged sword for bone metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gesty-Palmer D, Flannery P, Yuan L, Corsino L, Spurney R, Lefkowitz RJ, Luttrell LM. A beta-arrestin-biased agonist of the parathyroid hormone receptor (PTH1R) promotes bone formation independent of G protein activation. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:1ra1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kjaergaard H, Olsen J, Ottesen B, Dykes AK. Incidence and outcomes of dystocia in the active phase of labor in term nulliparous women with spontaneous labor onset. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:402–7. doi: 10.1080/00016340902811001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rouse DJ, Leindecker S, Landon M, Bloom SL, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Spong CY, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, O’Sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Langer O. National Institute of Child H, Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units N. The MFMU Cesarean Registry: uterine atony after primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1056–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Grotegut CA, Feng L, Mao L, Heine RP, Murtha AP, Rockman HA. beta-Arrestin mediates oxytocin receptor signaling, which regulates uterine contractility and cellular migration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E468–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00390.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]