The greatest artist does not have any concept

Which a single piece of marble does not itself contain

Within its excess, though only

A hand that obeys the intellect can discover it.

— Michelangelo Buonarroti, the Sonnets

Introduction

Michelangelo Buonarroti, one of the greatest artists of all time, represented sublime beauty and remains still unmatched even after five centuries. Near the end of his life, he wisely warned that ‘No one has mastery before he is at the end of his art and his life’.1–3 Several organic diseases and various psychological/behavioural disorders have been attributed to Michelangelo.

From the analysis of the literature, it is now clear that Michelangelo was afflicted by an illness involving his joints. This interpretation seems corroborated by the vast correspondence with his nephew, Lionardo di Buonarroto Simoni, which reveals that the artist suffered from ‘gout’, an ill-defined general term of the period, encompassing all arthritic conditions. Michelangelo described the symptoms of his nephrolithiasis, with repeated expulsion of stones, and one dramatic acute obstruction.1

The analysis of his life and his working conditions suggests that ‘gouty nephropathy’ was ‘cured’ after 1549 under the care of the anatomist Matteo Realdo Colombo by a daily intake of mineral water from Viterbo.1,4

The symptoms of ‘tophus arthritis’ were described as a ‘cruel pain’ affecting one foot.1 The portrait of Michelangelo showing a deformed right knee with excrescences (but without clear signs of joint inflammation), seen in Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens, adds support to these suspicions of ‘gout’.5

Lead poisoning has also been suspected in several publications. This could have been caused either by dye and toxic solvents dripping on his face or by his consumption of wine stored in lead containers.6,7 The artist’s transient nistagmus, during his work in the Sistine Chapel, may possibly have resulted from lead poisoning, but more likely it came from prolonged upward gazing in a dim light, responsible also for his reported dizziness and disturbed equilibrium.8 Lead intoxication could also explain the depression evidenced in his letters.1,5,7,9

Psychological disorders have also been put forward and the unlikely diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder or high-functioning autism has been proposed to explain the artist’s work routine, unusual lifestyle, and poor social and communication skills.9

The aim of the present work was to focus mainly on the disease that affected the Master’s hands.

Materials and methods

The analysis of the available portraits of Michelangelo suggests various pathologies. None of these can be confirmed because the authorities of the Church of Santa Croce in Florence, the artist’s burial site, did not permit any pathological investigations. The portraits obtained in the many years of his long life depict the Master’s progressive aging. His hands are represented in some paintings and perhaps also in some sculptures. There are no spectroscopic or X-ray images available, and for this reason, the careful observation of the portraits is the only method available today to interpret hand deformities. Therefore, three portraits constitute the main subject of this review, particularly concentrating on the hands of the Master. Two of these paintings were done in his lifetime, and a copy of one of them was executed many years after his death. The paintings were authenticated by Giorgio Vasari:

Of Michelagnolo (Michelangelo) we have no other portraits but two in painting, one by the hand of Bugiardini and the other by Jacopo del Conte, one in bronze executed in full-relief by Daniello (Daniele) Ricciarelli, and this one by the Chevalier Leone; from which portraits so many copies have been made, that I have seen a good number in many places in Italy and in foreign parts.10

The first index painting is dated 1535 and depicts the artist’s left hand, the Master being aged 60 years, already with a long career of sculpturing behind him. The painter, Jacopino del Conte (1510–1598), a Florentine Mannerist, shows Michelangelo looking older than his age, tired, his hanging left hand apparently with signs of a non-inflammatory articular disease (such as osteoarthritis) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Portrait of Michelangelo Buonarroti (c.1535), by Jacopino del Conte, oil on panel [from the Casa Buonarroti Museum, Florence, Italy; © 2015. Foto Scala, Firenze].

The second painting dated 1544, by Daniele Ricciarelli (better known as da Volterra), is probably a copy of del Conte’s work. Daniele da Volterra was an Italian Mannerist painter and sculptor who came to Rome in 1535, started work in the circle of Michelangelo, became his friend and remained so until 1564.

Much later, namely in 1595, Pompeo Caccini depicted Michelangelo in his studio in front of the original bronze model of David (now lost), painted 36 years after Michelangelo’s death (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Portrait of Michelangelo Buonarroti (c.1595), by Pompeo di Giulio Caccini, oil on wood [from the Casa Buonarroti Museum, Florence, Italy; © 2015. Foto Scala, Firenze].

All three paintings show the left hand of Michelangelo between the ages 60 to 65 years. They were interpreted by contemporary historians as suggesting the artist’s left-handedness. The portraits show Michelangelo’s hand to be affected by degenerative arthritis, in particular at the trapezius/metacarpal joint level, as well as at the metacarpo/phalangeal joint level, the interphalangeal joint of the thumb, the metacarpo/phalangeal joint and the proximal interphalangeal joint of the index finger levels (Figure 3). These are clear non-inflammatory degenerative changes, which were probably accelerated by prolonged hammering and chiseling. The possibility of ganglion swelling at the dorsal side of the trapezius/metacarpal joint or metacarpo/phalangeal joint is less likely, because it would be expected at the flexor tendon side. It remains still unknown if the suspected, but unproven, uric acid metabolic dysfunction may have contributed to these changes that are without evidence of tophi and are clearly not inflammatory. Michelangelo’s difficulties with tasks such as writing may have resulted from stiffness of the thumb and the loss of the ability to abduct, flex and adduct it. The swellings at the base of the thumb and the swellings of the smaller joints of the thumb and index are not gouty in origin; they may be interpreted as osteoarthritic nodules.

Figure 3.

Magnified hands from Figures 1 and 2 and from the Portrait of Michelangelo Buonarroti (c.1544), by Daniele da Volterra, oil on wood [from the Metropolitan Museum, New York, USA; © 2015. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Firenze].

Discussion

Michelangelo reached his desired mastery by living nearly 89 years, being extremely prolific and spanning into many disciplines.10,11 Few scholars, however, know that this remarkable sculptor and reluctant painter (as he defined himself) suffered a great deal from ‘arthritis’ involving his hands, more so during the last 15 years of his life. In an earlier portrait of Michelangelo, presented as Heraclitus in Raphael’s School of Athens (1509–1510) and one of his own image on the Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508–1512),5 his hands appear with no signs of deformity. The Master stated in his letters that his hand symptoms appeared almost 40 years later. Indeed in 1552, in a letter to his nephew, the Master stated ‘… writing gives me a great discomfort’.1

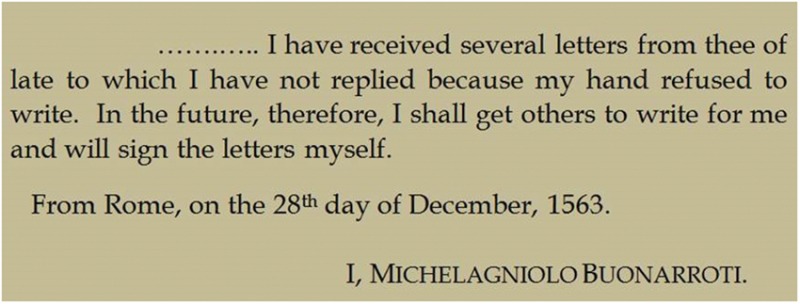

The image of Nicodemus in the marble sculpture of The Deposition (or the Florence Pietà) was carved between 1547 and 1553, when his hand troubles were just starting. Despite the debilitating effects on his health and on his primary working tools (his hands), Michelangelo was able to create one masterpiece after another. Indeed, he was seen ‘hammering’ up to six days before he died (18 February 1564),2,10,11 and his final work, the Rondanini Pietà, remained unfinished. At that stage, Michelangelo was unable to write anymore, he relied on others and only signed his letters.1,2

Conclusions

Reviewing Michelangelo’s portraits, various conclusions could be inferred in relation to his hands. First of all, it is important to recall that the images may support the claim of the Master’s left-handedness. Moreover, the hypothesis of gouty arthritis of the hands as the main cause of the pain in his hand can be dismissed, mainly because no signs of inflammation and no tophi can be seen on his extremities. More likely, his suffering may be due to a degenerative modification of the small joints of his hands which may be interpreted today as osteoarthritis. Obviously, this diagnosis cannot exclude the contribution of a metabolic disease causing nepholithiasis, a foot inflammation, or a deterioration of the small joints in his hands.

The diagnosis of osteoarthritis offers one plausible explanation for Michelangelo’s old age loss of dexterity, emphasising his triumph over infirmity, while persisting in his work until his last days. Indeed, it is interesting to note that functionality is maintained and that the continuous and intense work could have helped the Master to keep the use of his hands as long as possible.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

DL

Contributorship

DL, MFC and GMW have made a substantial contribution to the concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; MMC and DL have made a substantial contribution in the acquisition and interpretation of data; DL, MFC, MMC, DL and GMW drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content; DL, MFC, MMC, DL and GMW approved the version to be published.

Acknowledgements

None

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Michael Baum

References

- 1.Ramsden EH. The Letters of Michelangelo. Vol. 2. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1963, pp. 153–211.

- 2.Fiorio MT. The Pietà Rondanini 2004; Vol. 13, Milan, Italy: Electa, pp. 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilloowala R. Michelangelo: anatomy and its implication in his art. Vesalius 2009; 15: 19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Androutsos G. The beneficial effect of mineral waters of Fiuggi on Pope Bonifacio VIII and Michelangelo: two prominent calculous patients. Prog Urol 2005; 15: 762–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espinel CH. Michelangelo’s gout in a fresco by Raphael. Lancet 1999; 354: 2149–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montes-Santiago J. The lead-poisoned genius: saturnism in famous artists across five centuries. Prog Brain Res 2013; 203: 223–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf PL. The effects of diseases, drugs, and chemicals on the creativity and productivity of famous sculptors, classic painters, classic music composers, and authors. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005; 129: 1457–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallenga PE, Neri G, D'Anastasio R, Pettorrossi VE, Alfieri E, Capasso L. Michelangelo’s eye disease. Med Hypotheses 2012; 78: 757–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arshad M, Fitzgerald M. Did Michelangelo (1475–1564) have high-functioning autism? J Med Biogr 2004; 12: 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasari G. The Lives of the Artists, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Condivi A. The Life of Michelangelo, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976. [Google Scholar]