Abstract

BACKGROUND

The prognostic significance of having extraskeletal vs. skeletal Ewing sarcoma in the setting of modern chemotherapy protocols is unknown. The purpose of this study was to compare the clinical characteristics, biologic features, and outcomes for patients with extraskeletal and skeletal Ewing sarcoma.

METHODS

Patients had localized Ewing sarcoma (ES) and were treated on two consecutive protocols using 5-drug chemotherapy (INT-0154 and AEWS0031). Patients were analyzed based on having an extraskeletal (n=213) or skeletal (n=826) site of tumor origin. Event-free survival (EFS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, compared using the log-rank test, and modeled using Cox multivariate regression.

RESULTS

Patients with extraskeletal Ewing Sarcoma (EES) were more likely to have axial tumors (72% vs. 55%; P < 0.001), less likely to have tumors > 8 cm (9% vs. 17%; P < 0.01), and less likely to be white (81% vs. 87%; P < 0.001) compared to patients with skeletal ES. There was no difference in key genomic features (type of EWSR1 translocation, TP53 mutation, CDKN2A mutation/loss) between groups. After controlling for age, race, and primary site, EES was associated with superior EFS [hazard ratio = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.50–0.95; P = 0.02]. Among patients with EES, age ≥ 18 years, non-white race, and elevated baseline erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were independently associated with inferior EFS.

CONCLUSION

Clinical characteristics, but not key tumor genomic features, differ between EES and skeletal ES. Extraskeletal origin is a favorable prognostic factor, independent of age, race, and primary site.

Keywords: Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma, soft tissue Ewing sarcoma, extraosseous, prognosis, gene expression, gene profiling

INTRODUCTION

Ewing sarcoma (ES) is the second most common malignant bone tumor of childhood. It most commonly arises from bone but can develop in extraskeletal sites. Based upon data from clinical trials and from large registry data, extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (EES) accounts for approximately 20% to 30% of cases.[1,2] Historically these patients were treated on rhabdomyosarcoma protocols, however it is now recognized that patients with EES benefit from treatment protocols for patients with Ewing sarcoma of the bone.[2–5]

Previous reports have suggested that there may be clinical differences between patients with extraskeletal and skeletal Ewing sarcoma.[1,3,4,6,7] For example, patients with extraskeletal disease have been reported to be older and to have a propensity for axial tumor origin. The prognostic significance of having an EES using contemporary treatment protocols remains unclear, though two more recent reports have suggested superior outcomes for these patients.[1,7] Likewise, it is unknown if the approach to local control of the primary tumor differs based upon tissue of origin. Moreover, potential biologic differences between skeletal and extraskeletal tumors remain largely unexplored.

In order to address these gaps in our knowledge, we used a large cohort of patients treated on two consecutive cooperative group clinical trials to compare the clinical features, approach to local control, and outcomes in patients with extraskeletal versus skeletal localized Ewing sarcoma. Additionally, we explored potential biologic differences between these two groups, providing a comprehensive evaluation of differences in somatic mutations and gene expression.

METHODS

Patients

The cohort included eligible patients treated on all arms of the cooperative group trials INT-0154 and AEWS0031.[2,8] Eligible patients were those with newly diagnosed, localized Ewing sarcoma or primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) of the bone or soft tissue who were diagnosed based on having histological and/or immunohistochemical findings consistent with Ewing sarcoma or PNET. Information regarding translocation status was used as supportive data but was not required for study eligibility. Patients were aged ≤ 30 years for INT-0154 and ≤ 50 years for AEWS0031. Patients with unknown skeletal vs. extraskeletal status were excluded from this analysis. There were no other exclusion criteria. Details of the treatment on these two trials have previously been published, but all patients received alternating cycles of vincristine-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide-etoposide given on an every two- or three-week basis.

Patients in this analysis were treated primarily at Children’s Oncology Group (COG) centers located in the United States and Canada. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained locally by each participating center, with written informed consent obtained for all patients prior to enrollment. This secondary analysis utilized de-identified data and was exempt from separate IRB review.

Primary Predictor Variable

Patients were categorized for analysis as having extraskeletal or skeletal Ewing sarcoma. For both INT-0154 and AEWS0031, any tumor with any degree of bone involvement was considered a primary bone tumor. Initial designation of extraskeletal origin was based upon site report and confirmed by study chair review of baseline imaging reports, when available. For AEWS0031, records of this review were maintained and there were originally 136 patients designated as extraskeletal by the treating facility. Baseline imaging reports were available for the study chair to review in 118 of these 136 patients. For the 18 patients that did not have baseline imaging reports available for review, the original designation of extraskeletal from the treating facility was maintained. Of the 118 patients with available imaging reports, the study chair determined on his review that 17 patients had skeletal tumors, and so these 17 patients were reclassified, resulting in a final cohort of 119 patients with extraskeletal ES from AEWS0031.

Outcome Variables

Primary sites were categorized into groups based on the involved body compartment. To account for the various extraskeletal locations within a given body compartment, all structures including skin, subcutaneous or connective tissue, lymph nodes, muscles, and organs were included in the given specific site designation. The one exception was sites designated as paraspinal that included primary sites involving or adjacent to the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. The sites were classified as follows: head and neck; thorax and abdomen; pelvis; proximal extremity (proximal humerus through elbow, proximal femur through knee); distal extremity (below elbow through wrist and hand, below knee through ankle and foot); paraspinal; and “other”. Primary sites were further categorized for analysis as either axial or non-axial and pelvic or non-pelvic.

In addition to primary site, the following clinical variables were analyzed: age; sex; race; tumor size; baseline lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); baseline erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and type of local control. Age was further categorized as either < 18 or ≥ 18 years of age [9], and tumor size further categorized as ≤ 8 or >8 cm in maximum dimension. Tumor size data were not collected on AEWS0031. For LDH, the institutional upper limit of normal was used to divide patients into those with elevated LDH values and those with normal values. For ESR, the 75th percentile of the entire cohort was used as a cut point to divide patients into those at or above the 75th percentile and those below. Clinical outcomes of interest included death, second malignancy, relapse/progression, and type of first relapse/progression (local failure; distant failure; or combined failure).

Information regarding tumor biology was also obtained where available and included type of EWSR1 translocation as determined in a prior study.[10] Presence or absence of a TP53 mutation or CDKN2A mutation/loss were assessed in a subset of patients included in a retrospective analysis.[11] To investigate differences in gene expression between EES and skeletal ES, we interrogated Affymetrix expression array data from a cohort of 46 patients (GEO: GSE63157).[12]

Statistical Methods

Categorical variables were compared between patients with extraskeletal and skeletal Ewing sarcoma using two-sided Fisher exact or chi-squared tests. Continuous variables were compared between groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Patients who had missing data for a given characteristic were not included in the statistical tests for differences between groups.

The primary outcome of interest was event-free survival (EFS) which was defined as the time elapsed between study entry and either the occurrence of an analytic event or the date of the last patient contact, whichever came first. Disease progression, diagnosis of any second malignant neoplasm, and death were considered analytic events. Patients who had not experienced an event as of their last contact were considered censored. Overall survival was a secondary outcome and was defined as time from study entry to death or last follow-up for surviving patients. Event-free and overall survival distributions were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Confidence intervals were calculated using the complementary log-log distribution of the Kaplan-Meier estimate. Differences in event risk between groups in the univariate setting were evaluated by the log-rank test. Those baseline variables with a statistically significant effect on EFS based on the log-rank test were considered candidate variables for regression models, though variables with extensive missing data, such as tumor size, were removed from potential consideration. Backwards selection was used to generate a Cox regression model with a threshold p-value of 0.05 to be retained in the model. For the regression model containing all patients, the variable defining EES vs. skeletal ES was retained throughout all models.

Differences in pattern of relapse between patients with EES and skeletal ES were examined by way of cumulative incidence analysis. The relapse types of interest were local-only progression, distant-only progression, and local plus distant progression. For each relapse type of interest, the cumulative incidence distributions were estimated by the method of Marubini and Valsecchi.[13] Tests for differences between groups in the incidence of the relapse type of interest were conducted by way of competing risks regression using the method of Fine and Gray.[14]

For gene expression studies, differentially expressed genes were identified as described previously.[12] Briefly, non-annotated transcripts and transcripts with low expression in at least 25% of samples (log2 signal < 2.6) and with low variability across all samples (interquartile range of log2 signals < 0.5) were excluded. A moderated t-test was used to identify differential expression between the remaining 4,615 annotated genes, as described previously. [12] Genes with a fold change of at least 1.5 and a p-value of <0.05 were deemed to be differentially expressed. The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v6.7 was used for the functional enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed.[15]

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Clinical Features Differ Between Extraskeletal and Skeletal Ewing Sarcoma

Of the 1039 localized Ewing sarcoma patients included in our analysis, 213 (20.5%) had EES while 826 (79.5%) had skeletal tumors. A comparison of the clinical features by site is shown in Table I. There was no difference in age at diagnosis between the two groups. Patients with EES were more likely to be non-white compared to patients with skeletal ES (14% vs. 6%; P < 0.001). The distribution of primary sites differed between the two groups. Patients with EES were more likely to have tumors arising in axial locations (72% vs. 55%; P < 0.001), but showed a trend towards having fewer pelvic primary sites (14% vs. 19%; P = 0.07). Patients with EES were more likely to have tumors < 8 cm (21% vs. 16%; P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in baseline LDH and ESR values.

TABLE I.

Comparison of Clinical Features between Patients with Extraskeletal Versus Skeletal Localized Ewing Sarcoma

| Characteristic | Extraskeletal# (n=213) | Skeletal# (n=826) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Median age (range), y | 12 (0 – 30) | 12 (0 – 45) | 0.461 |

|

| |||

| Age | 0.912 | ||

| < 18 years | 187 (88%) | 721 (87%) | |

| ≥ 18 years | 26 (12%) | 105 (13%) | |

|

| |||

| Sex | 1.02 | ||

| Male | 116 (55%) | 449 (54%) | |

| Female | 97 (45%) | 377 (46%) | |

|

| |||

| Race | < 0.0012 | ||

| White | 172 (81%) | 721 (87%) | |

| Non-white | 29 (14%) | 51 (6%) | |

| Unknown | 12 (6%) | 54 (7%) | |

|

| |||

| Primary site | < 0.0013 | ||

| Distal extremity | 22 (10%) | 191 (23%) | |

| Proximal extremity | 34 (16%) | 179 (22%) | |

| Pelvis | 29 (14%) | 160 (19%) | |

| Spinal/Paraspinal | 15 (7%) | 76 (9%) | |

| Thorax/Abdomen | 92 (43%)* | 164 (20%) | |

| Head and Neck | 17 (8%) | 56 (7%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

|

| |||

| Primary site | < 0.0012 | ||

| Axial | 153 (72%) | 456 (55%) | |

| Non-axial | 56 (26%) | 370 (45%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

|

| |||

| Primary site | 0.072 | ||

| Pelvic | 29 (14%) | 160 (19%) | |

| Non-pelvic | 180 (85%) | 666 (81%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (2%) | 0 (0)% | |

|

| |||

| Median tumor size (interquartile range), cm | 6 (4–9) | 9 (6–12) | <0.0011 |

|

| |||

| Tumor size, cm | <0.012 | ||

| ≤ 8 | 44 (21%) | 136 (16%) | |

| > 8 | 18 (9%) | 137 (17%) | |

| Unknown | 151 (71%) | 553 (67%) | |

|

| |||

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) | 0.442 | ||

| Normal | 135 (63%) | 478 (58%) | |

| Elevated | 61(29%) | 249 (30%) | |

| Unknown | 17 (8%) | 99 (12%) | |

|

| |||

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) | 0.512 | ||

| ≤ 46 mm/hr | 106 (50%) | 397 (48%) | |

| > 46 mm/hr | 32 (15%) | 140 (17%) | |

| Unknown | 75 (35%) | 289 (35%) | |

|

| |||

| Local control | < 0.013 | ||

| Surgery | 99 (46%) | 435 (53%) | |

| Radiation | 34 (16%) | 166 (20%) | |

| Surgery + radiation | 63 (30%) | 138 (17%) | |

| Unknown | 17 (8%) | 87 (11%) | |

|

| |||

| Study | 0.702 | ||

| INT-0154 | 94 (44%) | 377 (46%) | |

| AEWS0031 | 119 (56%) | 449 (54%) | |

Two-sided Wilcoxon test;

Two-sided Fisher Exact test;

Likelihood Ratio Chi-Squared test;

Includes 13 cases of primary renal Ewing sarcoma;

Totals do not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Local control strategies differed between groups. Compared to patients with skeletal ES, those with EES were more likely to receive a combined modality approach (surgery plus radiation) for local control (30% vs. 17%; P < 0.01). We evaluated this pattern more closely using data available from AEWS0031. The majority of patients who received a combined modality approach received post-operative radiotherapy, with similar rates between EES and skeletal ES (91% and 83%, respectively). Margin status was available for 65 of the patients from AEWS0031 included in this analysis who received post-operative radiotherapy. Review of these data suggested that a greater proportion of patients with EES treated with post-operative radiotherapy had positive surgical margins compared to skeletal ES (66% vs. 48%).

Clinical Outcomes Differ Between Localized Extraskeletal and Skeletal Ewing Sarcoma

Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) estimates are shown in Figure 1. The 5-year unadjusted EFS for patients with EES was 76% (95% confidence interval (CI): 69–81%) compared to 69% (95% CI: 65–72%) for patients with skeletal ES (P = 0.05; Figure 1A). The 5-year unadjusted OS for patients with EES was 85% (95% CI: 80–90%) compared to 78% (95% CI: 75–81%) for patients with skeletal ES (P = 0.11; Figure 1B). We also performed a sensitivity analysis of EFS focused exclusively on patients treated on AEWS0031 and observed a significantly decreased risk for event for patients with EES compared to skeletal ES [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.52; 95% CI 0.33–0.82; P = 0.005].

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates comparing 5-year A) event-free survival (EFS) and B) overall survival (OS) between patients with extraskeletal vs. skeletal localized Ewing sarcoma.

We constructed a Cox proportional hazards model in the full analytic cohort to assess the prognostic impact of extraskeletal origin while controlling for other known risk factors. After controlling for age, race, and primary site, patients with EES were at reduced risk for an event compared to patients with skeletal tumors (HR = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.50–0.95; P = 0.02).

We next evaluated whether the type of relapse differed between EES and skeletal ES patients. There were no statistically significant differences in the cumulative incidence of local, distant, or combined relapses between the two groups, though there was a trend to suggest higher incidence of isolated distant failure in patients with skeletal ES (data not shown).

We next focused exclusively on patients with EES. We first performed a univariate analysis of EFS and found that age, race, and ESR were significantly associated with risk of an event (Table II). These variables were also significant predictors of OS, though we also observed a trend in which patients with pelvic EES had superior OS (HR=0.18; 95% CI: 0.02–1.29; P=0.09; Table II). We then constructed a Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent prognostic factors for EFS just in the EES group. Age ≥ 18 years (HR 2.87; 95% CI 1.28–6.45; P = 0.01), non-white race (HR 2.86; 95% CI 1.31–6.25; P < 0.01), and elevated baseline ESR (HR 2.68; 95% CI 1.29–5.54; P < 0.01) were each independently associated with inferior outcome. Due to the extensive amount of missing data regarding tumor size in EES patients, we were not able to include this variable in our multivariate model.

TABLE II.

Results of Univariate Analysis of Event-Free And Overall Survival for Patients with Localized Extraskeletal Ewing Sarcoma

| Characteristic | HR for Event (95% CI) | P-value1 | HR for Death (95% CI) | P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||

| < 18 years | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥ 18 years | 2.63 (1.35–5.12) | 3.14 (1.47–6.69) | ||

|

| ||||

| Sex | 0.74 | 0.84 | ||

| Female | Ref | Ref | ||

| Male | 0.91 (0.53–1.56) | 1.07 (0.56–2.04) | ||

|

| ||||

| Race | 0.003 | 0.001 | ||

| White | Ref | Ref | ||

| Non-white | 2.62 (1.39–4.95) | 3.51 (1.71–7.22) | ||

|

| ||||

| Primary Site | 0.53 | 0.17 | ||

| Thorax/Abdomen | Ref | Ref | ||

| Distal extremity | 0.48 (0.14–1.60) | 0.69 (0.20–2.35) | ||

| Proximal extremity | 1.25 (0.61–2.55) | 1.36 (0.60–3.05) | ||

| Pelvis | 0.63 (0.24–1.66) | 0.18 (0.02–1.36) | ||

| Spinal/Paraspinal | 1.31 (0.50–3.44) | 1.44 (0.48–4.28) | ||

| Head and Neck | 0.81 (0.28–2.33) | 0.57 (0.13–2.46) | ||

|

| ||||

| Primary Site | 0.99 | 0.44 | ||

| Non-axial | Ref | Ref | ||

| Axial | 1.01 (0.54–1.86) | 0.76 (0.38–1.52) | ||

|

| ||||

| Primary Site | 0.35 | 0.09 | ||

| Non-pelvic | Ref | Ref | ||

| Pelvic | 0.64 (0.26–1.62) | 0.18 (0.02–1.29) | ||

|

| ||||

| Tumor size, cm | 0.73 | 0.81 | ||

| ≤ 6 | Ref | Ref | ||

| > 6 | 0.85 (0.34–2.12) | 1.14 (0.40–3.25) | ||

|

| ||||

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) | 0.93 | 0.26 | ||

| Normal | Ref | Ref | ||

| Elevated | 1.03 (0.56–1.88) | 1.49 (0.75–2.95) | ||

|

| ||||

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| ≤ 46 mm/hr | Ref | Ref | ||

| > 46 mm/hr | 2.49 (1.25–4.96) | 3.02 (1.33–6.83) | ||

|

| ||||

| Study | 0.06 | 0.14 | ||

| AEWS0031 | Ref | Ref | ||

| INT-0154 | 1.69 (0.97–2.94) | 1.68 (0.85–3.32) | ||

Abbreviations: HR=hazard ratio; Ref=reference group; CI=confidence interval.

P-value, relative hazard and 95% confidence interval calculated using a proportional hazards regression model with the noted characteristic as the only variable in the model.

Biologic Features in Extraskeletal and Skeletal Ewing Sarcoma

Data on EWSR1 translocation status, TP53 mutation, and CDKN2A status were available for 112, 93, and 107 patients, respectively, whose tumors have previously been profiled and results published (Table III).[10,11] There were no differences in the frequency of harboring any EWSR1 translocation (P = 0.84) or, among those with EWSR1/FLI1 translocations, in the subtype of EWSR1/FLI1 translocation (P = 0.33) between EES and skeletal Ewing sarcoma. Likewise, the frequency of TP53 mutation or CDKN2A mutation/loss did not differ between EES and skeletal Ewing sarcoma.

TABLE III.

Comparison of Biologic Features between Patients with Extraskeletal Versus Skeletal Localized Ewing sarcoma

| Characteristic | Extraskeletal | Skeletal | P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Translocation | 0.84 | ||

| EWSR1-FLI1 | 22 (78%) | 67 (81%) | |

| Other | 3 (11%) | 6 (7%) | |

| Negative | 3 (11%) | 10 (12%) | |

|

| |||

| EWSR1-FLI1 Translocation | 0.33 | ||

| Type 1 | 15 (68%) | 44 (66%) | |

| Type 2 | 6 (27%) | 12 (18%) | |

| Other | 1 (5%) | 11 (16%) | |

|

| |||

| TP53 mutation | 0.18 | ||

| Mutation | 3 (17%) | 5 (7%) | |

| Normal | 15 (83%) | 70 (93%) | |

|

| |||

| CDKN2A mutation/loss | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 2 (9%) | 10 (12%) | |

| No | 21 (91%) | 74 (88%) | |

Two-sided Fisher Exact test

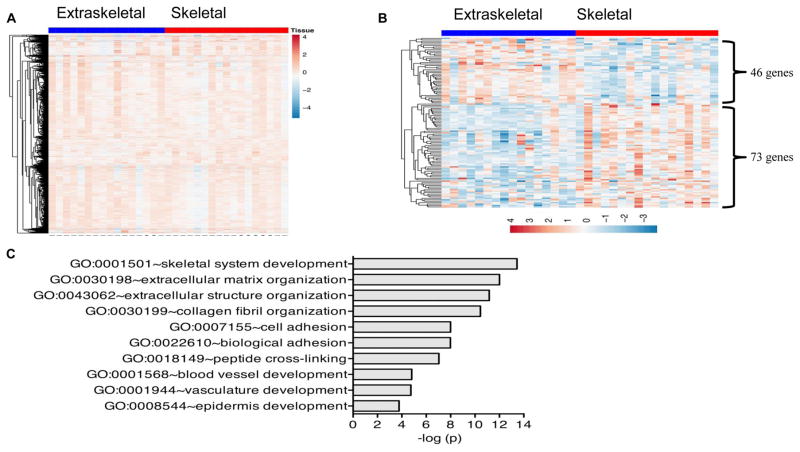

We next compared gene expression profiles between EES and skeletal ES in 46 tumors previously profiled as part of an earlier study.[12] As previously reported, unsupervised hierarchical clustering of these 46 tumors with available data failed to discriminate EES and skeletal ES. Similarly, supervised hierarchical clustering of these tumors did not yield a clear differential pattern of gene expression between these two clinical groups at a whole genome level (Figure 2A). To determine if significant differences in expression exist at the level of individual genes or gene families, we performed transcript-level analyses, as described in the Methods. These analyses identified 119 genes as being differentially expressed between EES and skeletal tumors. Forty-six genes were more highly expressed in EES tumors while 73 were relatively up regulated in bone tumors (Figure 2B). Gene ontology analysis revealed a significant enrichment of skeletal system development and extracellular matrix genes among the 73 bone tumor-associated genes (Figure 2C). No specific biologic processes were enriched among EES tumor-associated genes.

Figure 2.

(A) Supervised hierarchical clustering reveals that genome wide expression profiles of extraskeletal and skeletal Ewing sarcoma tumors are largely equivalent. Clustering performed using 4,615 annotated and expressed genes. (B) Supervised clustering of differentially expressed genes (N=119 genes) between skeletal and extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma tumors (N= 46 tumors). Clustering limited to genes with fold changes of >1.5 and p<0.05. (C) Top 10 most enriched biologic processes among genes that are up regulated in skeletal compared to extraskeletal tumors.

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort of patients with localized Ewing sarcoma treated with modern chemotherapy protocols, we confirmed that there are important clinical differences between EES and skeletal ES patients. We also found that extraskeletal tumor origin is a favorable prognostic factor, independent of age, race, and tumor site. We determined that older age, non-white race, and elevated baseline ESR are independent adverse prognostic factors in patients with EES. We found that the pattern of relapse does not differ between EES and skeletal ES patients. We did not find significant differences in key genomic features between extraskeletal or skeletal tumors, a null finding that nevertheless improves our understanding of potential biological differences between groups. We also highlight differences in gene expression between these two groups.

Consistent with previous reports, we found that EES accounts for 20.5% of cases of Ewing sarcoma.[1] We confirmed the findings of previous studies that showed that compared to patients with skeletal ES, those with EES are more likely to be non-white with a non-pelvic, axial primary site. Data comparing tumor size between EES and skeletal ES are conflicting. Some studies have shown that EES tumors are smaller at diagnosis, while others have shown no difference.[1,3,7,16] We observed that EES patients were more likely to have smaller tumors (< 8 cm) compared to patients with skeletal ES. Interestingly EES patients with a pelvic primary site showed a trend towards improved overall survival, suggesting that this known adverse prognostic factor in skeletal ES may have the opposite effect in EES. Patients with EES in our study were more likely to receive a combined modality approach (surgery plus radiation) for local control. This is potentially due to the higher proportion of axial tumors seen in EES, a site which may be less amenable to complete resection with negative margins. Alternatively, it is possible that these patients were more likely to undergo upfront excisional biopsy without adequate margins, necessitating subsequent radiotherapy. Our results support a higher rate of positive surgical margins in this group of patients.

Prior studies have suggested that the outcomes for EES and skeletal ES are similar when treated with Ewing sarcoma protocols.[3–5,6,17,18] However, two more recently published studies reported improved survival for EES in comparison to skeletal ES.[1,7] Our findings are consistent with these more recent observations and increase the evidence base supporting a more favorable outcome for EES. The etiology for this pattern is not clear. While patients with EES were more likely to receive combined modality local control, previous analyses have not demonstrated improved outcomes with this approach, making this an unlikely explanation for the observed differences.[16,19] Differences in key genomic features in this disease are not a likely explanation as we did not observe such differences in our analysis. However, differential distribution of chemotherapy to bone vs. soft tissue sites and other differences in tumor microenvironment and angiogenesis identified in our gene expression analysis may provide clues for future investigation.

Prognostic factors identified specifically in patients with EES were similar to those reported for ES in general.[20–22] Elevated baseline ESR was significantly associated with inferior EFS among EES patients. Elevated ESR has been reported as an adverse prognostic factor in a variety of adult and pediatric cancers, including Ewing sarcoma in some studies.[23–31] We report for the first time the significance of ESR in patients with localized EES. ESR is known to be a marker of systemic inflammation, but the exact explanation for its prognostic implications in cancer remains unclear. There is a growing body of evidence that shows the importance of inflammation in all stages of tumor development, from initiation, to malignant transformation, to local invasion and establishment of metastatic niche.[32–35] Additionally, inflammatory cells have been shown to contribute to angiogenesis, immune suppression, and the establishment of the tumor microenvironment, which has been proven to be indispensable to the malignant conversion of cells and to the survival of the tumor.[32–35] Alternatively, increased ESR could be a marker of greater systemic burden of disease not appreciable on imaging (i.e. micrometastases), though we did not find that baseline LDH was prognostic in EES.

Recent literature has described a rare subset of highly aggressive EWSR1 translocation-negative sarcomas that have distinct genetic signatures and have been referred to as undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas or Ewing-like sarcomas.[36–41] Of the patients with available translocation status available, our study included 13 translocation-negative tumors. While it is possible that our cohort included tumors harboring one of the mutations commonly seen in Ewing-like sarcomas such as CIC-DUX4 or BCOR-CCNB3, the potential impact on our study is minimal given the small proportion of translocation-negative tumors and the fact that these tumors were balanced between groups.

One of the main strengths of our study was our ability to analyze a large cohort of EES patients treated with modern chemotherapy protocols and compare them to skeletal ES patients. Being able to confirm the diagnosis of extraskeletal ES for EES patients by review of the institutional baseline imaging reports increased the reliability of this designation in our study. We provide a description of the biologic features and genetic profiling in the largest cohort of EES patients. However, the conclusions that can be drawn from these comparisons are limited due to the relatively small sample size with available biological parameters. An additional limitation was that we lacked tumor size data on over half of the entire cohort, which limited our ability to control for this well-established prognostic factor in our multivariate models. Since patients with EES tended to have smaller tumors, differences in tumor size could potentially confound our observed relationship between tissue origin and prognosis. It is also possible that specific rare subgroups such as cutaneous ES may behave differently than the entire subgroup of EES.[42] We also acknowledge that the group of patients enrolled to COG studies is enriched for younger patients. This may account for the fact that we did not note a difference in age distribution between EES and skeletal ES, as has been reported by others.[1] In order to evaluate a more homogeneous patient population treated with similar chemotherapy, we focused our analysis on patients with localized disease. The extent to which our findings will generalize to patients with metastatic disease is unknown. We were also unable to confirm extraskeletal origin for all patients, particularly for patients on trial INT-0154. However, a sensitivity analysis focused exclusively on patients from AEWS0031 confirmed that patients with EES have superior EFS compared to patients with skeletal ES. Finally, while all patients received 5-drug therapy typical for this disease in North America, our sample size precluded sub-analyses based upon randomized arm of each of the included trials.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that clinical characteristics, but not key tumor genomic features, differ between EES and skeletal ES patients. We report for the first time differences in gene expression between these two groups. Prognostic factors in EES are similar to those established in patients with skeletal disease and ESR provides additional prognostic information. Additional efforts should be made to obtain specimens for biologic testing and gene profiling so that more robust comparisons of the genomic features analyzed in our study as well as newer mutations such as STAG2 can be made between these two groups of patients. While outcomes are statistically superior for EES, the clinical difference is relatively modest. This finding together with the rarity of Ewing sarcoma supports the current practice of treating these two subgroups with similar approaches.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: Supported by the Nick Currey Fund and NIH/NCI U10 CA98543. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

We acknowledge the assistance of Lei Huang with gene expression profile analyses, as well as Caihong Xia and Yun Gao with statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- ES

Ewing sarcoma

- EFS

Event-free survival

- EES

Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- PNET

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- DAVID

Database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery

- OS

Overall survival

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

Footnotes

Author Justification: All authors included on this manuscript have made significant contributions and warrant inclusion as co-authors. Thomas Cash is the lead author and investigator on this manuscript. Elizabeth McIlvaine and Mark Krailo performed the statistical analysis and both put in significant time to this study. Stephen Lessnick provided content expertise for our biologic and genomic comparisons and interpretation of this data. Elizabeth Lawlor provided our gene expression data and performed some of this analysis. Nadia Laack and Joel Sorger provided expertise in Radiation Oncology and Orthopedic Oncology, respectively, and provided insight into the approach to local control for these patients with extraskeletal tumors; this was critical to designing our analysis and interpreting the results. Neyssa Marina provided clinical expertise which shaped our understanding of our data analysis and interpretation. Holcombe Grier has been a leader in the field of Ewing sarcoma for the past two decades, played a role in the clinical trials included in this study, and helped in the design, interpretation and writing of this study. Linda Granowetter (INT-0154) and Richard Womer (AEWS0031) served as the principal investigators for the clinical trials included in this trial, and as such provided invaluable insight at every step. Steven DuBois served as senior author and oversaw all components of this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest related to this work or its publication. Author S.L.L. has a leadership role and stock/ownership interest in Salarius Pharmaceuticals, however, again, this is not a conflict for this study.

References

- 1.Applebaum MA, Worch J, Matthay KK, Goldsby R, Neuhaus J, West DC, Dubois SG. Clinical features and outcomes in patients with extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma. Cancer. 2011;117:3027–3032. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granowetter L, Womer R, Devidas M, Krailo M, Wang C, Bernstein M, Marina N, Leavey P, Gebhardt M, Healey J, Shamberger RC, Goorin A, Miser J, Meyer J, Arndt CA, Sailer S, Marcus K, Perlman E, Dickman P, Grier HE. Dose-intensified compared with standard chemotherapy for non-metastatic Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2536–2541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castex MP, Rubie H, Stevens MC, Escribano CC, de Gauzy JS, Gomez-Brouchet A, Rey A, Delattre O, Oberlin O. Extraosseous localized ewing tumors: Improved outcome with anthracyclines--the French society of pediatric oncology and international society of pediatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1176–1182. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raney RB, Asmar L, Newton WA, Jr, Bagwell C, Breneman JC, Crist W, Gehan EA, Webber B, Wharam M, Wiener ES, Anderson JR, Maurer HM. Ewing’s sarcoma of soft tissues in childhood: A report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study, 1972 to 1991. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:574–582. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gururangan S, Marina NM, Luo X, Parham DM, Tzen CY, Greenwald CA, Rao BN, Kun LE, Meyer WH. Treatment of children with peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor or extraosseous Ewing’s tumor with Ewing’s-directed therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;20:55–61. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JA, Kim DH, Lim JS, Koh JS, Kim MS, Kong CB, Song WS, Cho WH, Lee SY, Jeon DG. Soft-tissue Ewing sarcoma in a low-incidence population: Comparison to skeletal Ewing sarcoma for clinical characteristics and treatment outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:1060–1067. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biswas B, Shukla NK, Deo SV, Agarwala S, Sharma DN, Vishnubhatla S, Bakhshi S. Evaluation of outcome and prognostic factors in extraosseous Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1925–1931. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Womer RB, West DC, Krailo MD, Dickman PS, Pawel BR, Grier HE, Marcus K, Sailer S, Healey JH, Dormans JP, Weiss AR. Randomized controlled trial of interval-compressed chemotherapy for the treatment of localized Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4148–4154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karski EE, McIlvaine E, Segal MR, Krailo M, Grier HE, Granowetter L, Womer RB, Meyers PA, Felgenhauer J, Marina N, DuBois SG. Identification of Discrete Prognostic Groups in Ewing Sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:47–53. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Doorninck JA, Ji L, Schaub B, Shimada H, Wing MR, Krailo MD, Lessnick SL, Marina N, Triche TJ, Sposto R, Womer RB, Lawlor ER. Current treatment protocols have eliminated the prognostic advantage of type 1 fusions in Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1989–1994. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerman DM, Monument MJ, McIlvaine E, Liu XQ, Huang D, Monovich L, Beeler N, Gorlick RG, Marina NM, Womer RB, Bridge JA, Krailo MD, Randall RL, Lessnick SL Children’s Oncology Group Ewing Sarcoma Biology Committee. Tumoral TP53 and/or CDKN2A alterations are not reliable prognostic biomarkers in patients with localized Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:759–765. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volchenboum SL, Andrade J, Huang L, Barkauskas DA, Krailo M, Womer RB, Ranft A, Potratz J, Dirksen U, Triche TJ, Lawlor ER. Gene expression profiling of Ewing sarcoma tumours reveals the prognostic importance of tumour–stromal interactions: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Path: Clin Res. 2015;1:83–94. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marubini E, Valsecchi MG. Analysing Survival Data from Clinical Trials and Observational Studies. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orr WS, Denbo JW, Billups CA, Wu J, Navid F, Rao BN, Davidoff AM, Krasin MJ. Analysis of prognostic factors in extraosseous Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: Review of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3816–3822. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Weshi A, Allam A, Ajarim D, Al Dayel F, Pant R, Bazarbashi S, Memon M. Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumours in adults: Analysis of 57 patients from a single institution. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2010;22:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Berg H, Heinen RC, van der Pal HJ, Merks JH. Extra-osseous Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;26:175–185. doi: 10.1080/08880010902855581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DuBois SG, Krailo MD, Gebhardt MC, Donaldson SS, Marcus KJ, Dormans J, Shamberger RC, Sailer S, Nicholas RW, Healey JH, Tarbell NJ, Randall RL, Devidas M, Meyer JS, Granowetter L, Womer RB, Bernstein M, Marina N, Grier HE. Comparative evaluation of local control strategies in localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2015;121:467–475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotterill SJ, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, Jürgens HF, Voûte PA, Gadner H, Craft AW. Prognostic factors in Ewing’s tumor of bone: Analysis of 975 patients from the European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing’s Sarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3108–3114. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bacci G, Ferrari S, Bertoni F, Rimondini S, Longhi A, Bacchini P, Forni C, Manfrini M, Donati D, Picci P. Prognostic factors in nonmetastatic Ewing’s sarcoma of bone treated with adjuvant chemotherapy: Analysis of 359 patients at the Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:4–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, Hoang BH, Ziogas A, Zell JA. Analysis of prognostic factors in Ewing sarcoma using a population-based cancer registry. Cancer. 2010;116:1964–1973. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strojnik T, Smigoc T, Lah TT. Prognostic value of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in the blood of patients with glioma. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sengupta S, Lohse CM, Cheville JC, Leibovich BC, Thompson RH, Webster WS, Frank I, Zincke H, Blute ML, Kwon ED. The preoperative erythrocyte sedimentation rate is an independent prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:304–312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexandrakis MG, Passam FH, Ganotakis ES, Sfiridaki K, Xilouri I, Perisinakis K, Kyriakou DS. The clinical and prognostic significance of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and acute phase protein levels in multiple myeloma. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25:41–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2003.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson JE, Sigurdsson T, Holmberg L, Bergström R. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate as a tumor marker in human prostatic cancer. An analysis of prognostic factors in 300 population-based consecutive cases. Cancer. 1992;7:1556–1563. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920915)70:6<1556::aid-cncr2820700619>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry-Amar M, Friedman S, Hayat M, Somers R, Meerwaldt JH, Carde P, Burgers JM, Thomas J, Monconduit M, Noordijk EM, Bron D, Regnier R, de Pauw BE, Tanguy A, Cosset JM, Dupouy N, Tubiana M. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate predicts early relapse and survival in early-stage Hodgkin disease: The EORTC Lymphoma Cooperative Group. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:361–365. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ilić I, Manojlović S, Cepulić M, Orlić D, Seiwerth S. Osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma in children and adolescents: Retrospective clinicopathological study. Croat Med J. 2004;45:740–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oberlin O, Deley MC, Bui BN, Gentet JC, Philip T, Terrier P, Carrie C, Mechinaud F, Schmitt C, Babin-Boillettot A, Michon J French Society of Paediatric Oncology. Prognostic factors in localized Ewing’s tumours and peripheral neuroectodermal tumours: The third study of the French Society of Paediatric Oncology (EW88 study) Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1646–1654. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aparicio J, Munárriz B, Pastor M, Vera FJ, Castel V, Aparisi F, Montalar J, Badal MD, Gómez-Codina J, Herranz C. Long-term follow-up and prognostic factors in Ewing’s sarcoma: A multivariate analysis of 116 patients from a single institution. Oncology. 1998;55:20–26. doi: 10.1159/000011841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bacci G, Ferrari S, Rosito P, Avella M, Barbieri E, Picci P, Battistini A, Brach del Prever A. Ewing’s sarcoma of the bone. Anatomoclinical study of 424 cases. Minerva Pediatr. 1992;44:345–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu H, Ouyang W, Huang C. Inflammation, a key event in cancer development. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:221–233. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. World Health Organization classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Italiano A, Sung YS, Zhang L, Singer S, Maki RG, Coindre JM, Antonescu CR. High prevalence of CIC fusion with double-homeobox (DUX4) transcription factors in EWSR1-negative undifferentiated small blue round cell sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:207–218. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierron G, Tirode F, Lucchesi C, Reynaud S, Ballet S, Cohen-Gogo S, Perrin V, Coindre JM, Delattre O. A new subtype of bone sarcoma defined by BCOR-CCNB3 gene fusion. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:461–466. doi: 10.1038/ng.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugita S, Arai Y, Tonooka A, Hama N, Totoki Y, Fujii T, Aoyama T, Asanuma H, Tsukahara T, Kaya M, Shibata T, Hasegawa T. A Novel CIC-FOXO4 Gene Fusion in Undifferentiated Small Round Cell Sarcoma: A Genetically Distinct Variant of Ewing-like Sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1571–1576. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonescu C. Round cell sarcomas beyond Ewing: Emerging entities. Histopathology. 2014;64:26–37. doi: 10.1111/his.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Specht K, Sung YS, Zhang L, Richter GH, Fletcher CD, Antonescu CR. Distinct transcriptional signature and immunoprofile of CIC-DUX4 fusion–positive round cell tumors compared to EWSR1-rearranged ewing sarcomas: Further evidence toward distinct pathologic entities. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:622–663. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delaplace M, Lhommet C, de Pinieux G, Vergier B, de Muret A, Machet L. Primary cutaneous Ewing sarcoma: A systematic review focused on treatment and outcome. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:721–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]