Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Body composition impacts physical function and mortality. We compared long-term body composition changes after antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation in HIV-infected individuals to that in HIV-uninfected controls.

DESIGN

Prospective observational study

METHODS

We performed dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) approximately 7.5 years after initial DXA in available HIV-infected individuals who received DXAs during the randomized treatment trial AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5202. For controls, we used DXA results from HIV-uninfected participants in the BACH/Bone and WIHS cohorts. Repeated measures analyses compared adjusted body composition changes between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals. Multivariable analyses evaluated factors associated with body composition change in HIV-infected individuals.

RESULTS

We obtained DXA results in 97 HIV-infected and 614 HIV-uninfected participants. Compared to controls, HIV-infected individuals had greater adjusted lean mass and total, trunk, and limb fat gain during the first 96 weeks of ART. Subsequently, HIV-infected individuals lost lean mass compared to controls. Total, trunk and limb fat gains after 96 weeks of ART slowed in HIV-infected individuals but remained greater than in controls. Lower CD4+ T-cell count was associated with lean mass and fat gain during the initial 96 weeks of ART, but subsequently no HIV-related characteristic was associated with body composition change.

CONCLUSIONS

Consistent with a “return to health effect”, HIV-infected individuals, especially those with lower baseline CD4+ T-cell counts, gained more lean mass and fat during the first 96 weeks of ART than HIV-uninfected individuals. Continued fat gain and lean mass loss after 96 weeks may predispose HIV-infected individuals to obesity-related diseases and physical function impairment.

Keywords: Anti-HIV Agents/*administration & dosage/*adverse effects, Body Fat Distribution, HIV-Associated Lipodystrophy Syndrome/*chemically induced, HIV Infections/*drug therapy/virology, Humans, HIV infection

INTRODUCTION

With continued improvements in survival, managing chronic conditions and optimizing overall health is becoming a primary concern in the care of HIV-infected individuals. Changes in body composition such as central fat accumulation and loss of muscle mass may impact physical function and mortality [1, 2]. Frailty has been reported to be approximately 4-fold more common in HIV-infected individuals than in HIV-uninfected controls [3, 4], with associations seen between frailty and both sarcopenia and central obesity [5, 6]

Several studies have evaluated changes in body composition during the first two years after antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation [7–11]. However, there is a paucity of studies reporting longer term body composition changes in ART-treated individuals, and no study to our knowledge has compared longer term body composition changes in HIV-infected individuals initiating ART to changes in HIV-uninfected controls. The aim of this study is to use a well-characterized study population to evaluate longer term (~7.5 years) body composition change after ART initiation as part of a randomized trial and to compare this rate of change to that observed in HIV-uninfected individuals.

METHODS

Participants and Study Procedures

ART-naive, HIV-1 infected individuals enrolled in AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) A5202 were randomized to atazanavir/ritonavir (ATV/r) or efavirenz (EFV) combined with either tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) or abacavir/lamivudine (ABC/3TC) during the years 2005 through 2007 [12]. Those who agreed to participate in the metabolic substudy, ACTG A5224s, had baseline and follow-up whole body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) performed, with the A5224s primary body composition endpoints reported at 96 weeks after ART initiation [9].

For the current study, in 2013–2014, we attempted to contact all participants, regardless of current ART, who were previously enrolled in ACTG A5224s (n=269). Study participants had one follow-up whole body DXA performed. All DXAs were standardized at the participating sites, then read and compared to prior scans centrally (Tufts University, Boston MA). Changes in bone mineral density from this study have been reported elsewhere [13].

We obtained a medical and medication history and administered to participants questionnaires capturing substance use and physical activity [14]. Participants underwent a physical examination, including measurement of height and weight. Each participant provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each site.

HIV-Uninfected Controls

For comparison to HIV-uninfected individuals, we utilized participant-level data from two multi-ethnic longitudinal studies that performed serial whole body DXA in young men and women. The Boston Area Community Health/Bone (BACH/Bone) Survey performed DXA at baseline and 7-year follow-up in 692 HIV-uninfected men [15]. From the metabolic sub-study of the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), we utilized whole body DXA results at baseline and 5-year follow-up in 122 HIV-uninfected women [16]. We excluded data from HIV-uninfected participants in these studies outside the sex-specific age window of the HIV-infected study participants (age range of HIV-infected men and women at initial DXA was 20 to 64 years and 23 to 55 years, respectively) and assumed a linear rate of body composition change among HIV-uninfected individuals.

Statistical Analyses

We used repeated measures analyses using piecewise slopes to compare the rate of body composition change (i.e., lean mass and total, trunk, and limb fat changes) between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals during the first 96 weeks of study (the “early” period) and from 96 weeks to the end of study follow-up (the “late” period), adjusting for age, sex, race, self-reported physical activity level, and cigarette and alcohol use.

In HIV-infected individuals, we compared the rate of body composition change during the early versus late period. We performed univariate and multivariable analyses to examine associations during the early and late periods between body composition change and age, sex, race/ethnicity, randomized ART regimen, and baseline and time-updated CD4+ T-cell count and HIV-1 RNA level. Factors with a univariate p-value of <0.20 were included into multivariable models, which used backward selection and retained factors with a p-value of <0.05.

All analysis testing was two-sided with a type I error of 5%; thus p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant with no adjustment for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Ninety-seven of the original 269 participants from ACTG A5224s were available for repeat DXA and enrolled in the current study. The baseline characteristics between those ACTG A5224s participants who did and did not enroll in the current study did not differ significantly (data not shown).

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the 97 HIV-infected individuals and 614 HIV-uninfected controls. Compared to HIV-uninfected controls, HIV-infected individuals were younger, were more likely to be white non-Hispanic, had a lower median body mass index (BMI) at both initial and final DXA, and had a higher rate of individuals who never smoked and reported low to moderate alcohol consumption. The median time interval between the initial and final DXA in HIV-infected participants and controls was 7.6 and 6.9 years, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-infected Participants vs. Controls†

| Characteristic | HIV-infected (n=97) | Controls (n=614) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Initial DXA – years | 40 (31, 44) | 46 (38, 54) | <0.001 |

| Time between Initial and Final DXA – years | 7.6 (7.3, 7.8) | 6.9 (6.5, 7.3) | <0.001 |

| Male Sex | 86% | 87% | 0.62 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| White Non-Hispanic | 47% | 35% | |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 34% | 33% | |

| Hispanic (Regardless of Race) | 14% | 31% | |

| Other | 5% | 1% | |

| BMI - kg/m2 | |||

| At Initial DXA | 24 (22, 27) | 28 (25, 32) | <0.001 |

| At Final DXA | 27 (23, 30) | 29 (26, 33) | <0.001 |

| Self-reported Physical Activity Level‡ | 0.07 | ||

| Low | 32% | 25% | |

| Moderate | 25% | 53% | |

| High | 43% | 22% | |

| Smoking‡ | <0.001 | ||

| Current | 33% | 31% | |

| Past | 14% | 33% | |

| Never | 53% | 36% | |

| Alcohol Consumption‡ | 0.03 | ||

| 0 drinks/day | 23% | 49% | |

| <3 drinks/day | 74% | 36% | |

| 3+ drinks/day | 3% | 14% | |

| Hepatitis C antibody positive | 6% | * | - |

| CD4+ T-cell Count – cells/µL | |||

| At Initial DXA | 247 (130, 333) | N.A. | - |

| At Final DXA | 598 (408, 707) | ||

| HIV-1 RNA – log10 copies/mL | |||

| At Initial DXA | 4.6 (4.2, 4.8) | N.A. | - |

| HIV-1 RNA Level <200 copies/mL at Final DXA | 86% | N.A. | - |

| Cumulative PI Exposure – Years | 3.7 (0, 6.9) | N.A. | - |

Medians (interquartile range) presented unless otherwise noted;

BMI=body mass index; DXA=dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; N.A.=not applicable; PI=protease inhibitor;

At final DXA (not available at initial DXA for HIV-infected);

= not captured in controls.

Among HIV-infected participants, the median age at initial DXA was 40 years. Eighty-six percent of participants were male. The median CD4 T-cell count at initial and final DXA was 247 and 598 cells/µL, respectively. The median HIV-1 RNA level at initial DXA was 4.6 log10 copies/mL, and 86% of participants had an HIV RNA level <200 copies/mL at the final DXA. The median exposure to a protease inhibitor (PI) during study follow-up was 3.7 years. Forty-five percent of HIV-infected participants were on a ritonavir-boosted PI at final DXA.

Body Composition Changes in HIV-Infected vs. Controls During the Early Period

Figure 1a displays the unadjusted change in total lean mass in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected individuals. During the first 96 weeks of study follow-up (i.e., “the early period”) after adjustment for age, sex, race, self-reported physical activity level, and cigarette and alcohol use, HIV-infected individuals gained significantly more lean mass than HIV-uninfected individuals (0.53 vs. 0.06 kg/year; 95% CI for difference: 0.12, 0.82 kg/year; p=0.008).

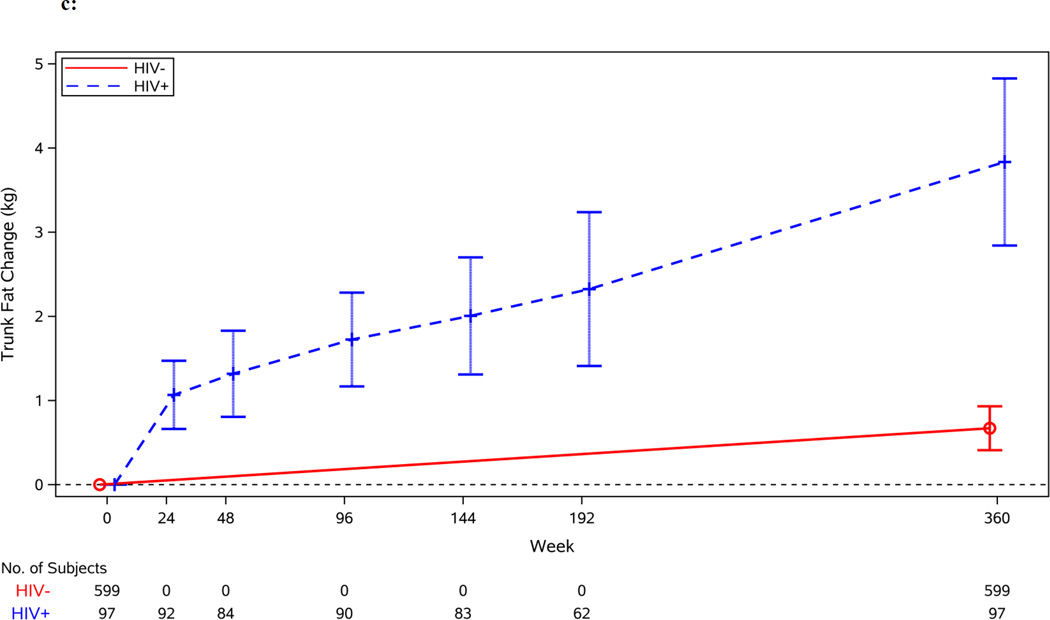

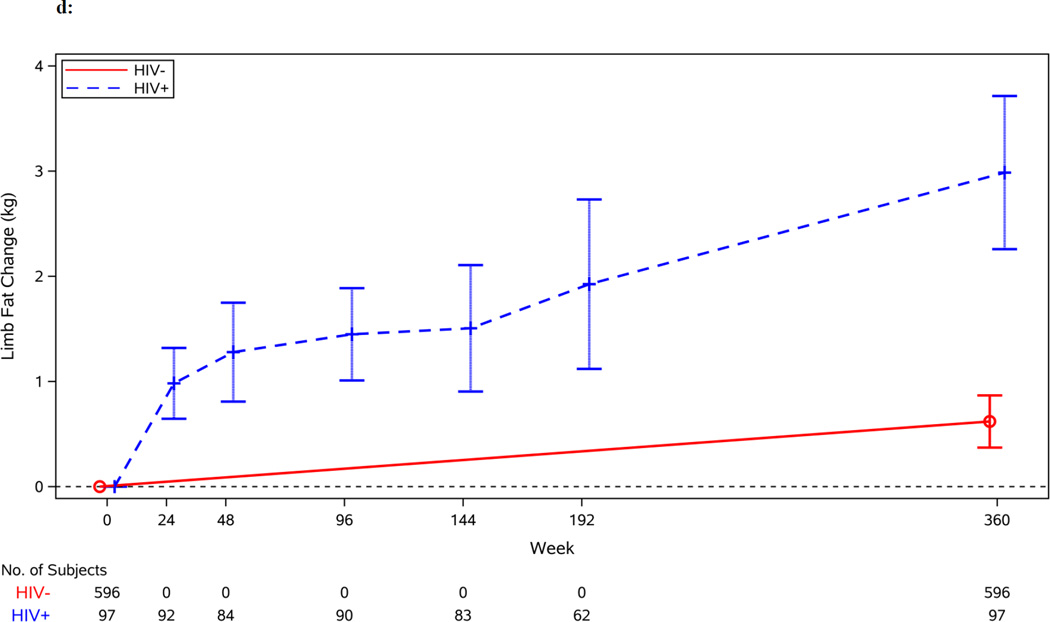

Figure 1.

a: Change in Lean Mass by Serostatus (in kilograms)

b: Change in Total Fat by Serostatus (in kilograms)

c: Change in Trunk Fat by Serostatus (in kilograms)

d: Change in Limb Fat by Serostatus (in kilograms)

Figures 1b–1d display the unadjusted changes in total, trunk and limb fat by HIV serostatus. After adjustment, HIV-infected individuals gained more total fat than HIV-uninfected individuals during the early period (1.43 vs. 0.15 kg/year; 95% CI for difference: 0.68, 1.88 kg/year; p=0.001). Changes in trunk and limb fat mirrored the change in total fat; during the early period after adjustment, HIV-infected individuals, compared to HIV-uninfected individuals, gained more trunk fat and limb fat (0.69 vs. 0.07 kg/year; 95% CI for difference: 0.28, 0.96 kg/year; p<0.001 and 0.70 vs. 0.08 kg/year; 95% CI for difference: 0.34, 0.90 kg/year; p<0.001, respectively).

Body Composition Changes During the Late Period

The rate of change in lean mass in HIV-infected individuals differed between the early and late period. During the late period, HIV-infected individuals on average lost lean mass after having gained lean mass during the first 96 weeks of ART (−0.28 vs. 0.53 kg/year; 95% CI for difference in rates between early and late periods: −1.21, −0.41 kg/year; p<0.001). After adjustment, HIV-infected individuals lost lean mass in comparison to HIV-uninfected controls during the late period (−0.28 vs. 0.06 kg/year; 95% CI for difference: −0.51, −0.18 kg/year p<0.001).

However, HIV-infected individuals continued to gain total fat in the late period, albeit at a slower rate when compared to the gains during the first 96 weeks of ART (0.70 vs. 1.43 kg/year; 95% CI for difference in rates between early and late periods: −1.37, −0.09 kg/year; p=0.03). After adjustment, during the late period HIV-infected individuals continued to gain more total fat than HIV-uninfected individuals (0.70 vs. 0.15 kg/year; 95% CI for difference: 0.31, 0.79 kg/year; p<0.001).

Changes in trunk and limb fat were similar to the changes in total fat in the late period. The gain rate of trunk fat and limb fat slowed in HIV-infected individuals from the early to the late period (0.68 vs. 0.38 kg/year; 95% CI for difference in rates between early and late periods: −0.68, 0.06 kg/year; p=0.095 and 0.70 vs. 0.28 kg/year; 95% CI for difference in rates between early and late periods: −0.72, −0.12; p=0.006, respectively). However, the gain in both trunk and limb fat remained significantly greater than the gain rate seen in HIV-uninfected individuals (0.38 vs. 0.07 kg/year; 95% CI for difference: 0.16, 0.45 kg/year; p<0.001 and 0.28 vs. 0.08 kg/year; 95% CI for difference: 0.09, 0.31 kg/year; p<0.001, respectively).

Factors Associated with Body Composition Change in HIV-Infected Individuals During the Early Period

Table 2a displays the univariate and multivariable analyses of factors associated with change in lean mass. In univariate analyses, both baseline lower CD4+ T-cell count and higher HIV-1 RNA level were associated with a greater increase in lean mass during the first 96 weeks after ART initiation (p<0.001 for both). In multivariable analysis, lower baseline CD4+ T-cell count remained significantly associated with a greater gain in lean body mass (p<0.001).

Table 2.

| a: Univariate and Multivariable Associations with Lean Mass Change (HIV-Infected only) † | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analyses | Multivariable Analysis | ||||

| Time Interval | Covariate | Estimated kg change/year (95% CI) |

p-value | Estimated kg change/year (95% CI) |

p-value |

| Initial to Week 96 | Years from baseline to week 96 | 0.79 (0.51, 1.08) | <0.001 | ||

| Age (per 1 year higher) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) | 0.56 | |||

| Male (vs. Female) | 0.45 (−0.66, 1.56) | 0.43 | |||

| Black non-Hispanic (vs. Not) | 0.21 (−0.59, 1.00) | 0.61 | |||

| Baseline CD4 T-cell count (per 50 cells/µL higher) | −0.25 (−0.38, −0.13) | <0.001 | −0.26 (−0.38, −0.13) | <0.001 | |

| Baseline HIV-1 RNA (per 1 log10 c/mL higher) | 1.02 (0.49, 1.56) | <0.001 | |||

| Randomized to ATV/r (vs. EFV) | 0.50 (−0.17, 1.17) | 0.14 | |||

| Randomized to TDF/FTC (vs. ABC/3TC) | −0.27 (−0.93, 0.40) | 0.43 | |||

| Time-updated CD4 count (per 50 cells/µL higher) | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.09) | 0.23 | |||

| Time-updated HIV-1 RNA <200 c/mL (vs. Not) | −0.10 (−0.64, 0.44) | 0.72 | |||

| Week 96 to Final | Years from baseline to week 96 | −0.29 (−0.44, −0.14) | <0.001 | ||

| Age (per 1 year higher) | −0.02 (−0.03, −0.01) | 0.007 | −0.02 (−0.03, −0.01) | 0.002 | |

| Male (vs. Female) | −0.12 (−0.45, 0.21) | 0.46 | |||

| Black non-Hispanic (vs. Not) | −0.37 (−0.66, −0.07) | 0.017 | −0.44 (−0.73, −0.16) | 0.003 | |

| Baseline CD4 count (per 50 cells/µL higher) | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.02) | 0.26 | |||

| Baseline HIV-1 RNA (per 1 log10 c/mL higher) | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.34) | 0.30 | |||

| Randomized to ATV/r (vs. EFV) | −0.09 (−0.40, 0.22) | 0.56 | |||

| Randomized to TDF/FTC (vs. ABC/3TC) | −0.02 (−0.32, 0.28) | 0.91 | |||

| Time-updated CD4 count (per 50 cells/µL higher) | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.34 | |||

| Time-updated HIV-1 RNA <200 c/mL (vs. Not) | 0.33 (−0.18, 0.83) | 0.20 | |||

| b: Univariate and Multivariable Associations with Total Body Fat Change (HIV-Infected only) † | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analyses | Multivariable Analysis | ||||

| Time Interval | Covariate | Estimated kg change/year (95% CI) |

p-value | Estimated kg change/year (95% CI) |

p-value |

| Initial to Week 96 | Years from baseline to week 96 | 1.65 (1.17, 2.13) | <0.001 | ||

| Age (per 1 year higher) | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.01) | 0.12 | |||

| Male (vs. Female) | 0.15 (−1.77, 2.07) | 0.88 | |||

| Black non-Hispanic (vs. Not) | −0.47 (−1.55, 0.60) | 0.38 | |||

| Baseline CD4 T-cell count (per 50 cells/µL higher) | −0.26 (−0.40, −0.12) | <0.001 | −0.26 (−0.40, −0.12) | 0.001 | |

| Baseline HIV-1 RNA (per 1 log10 c/mL higher) | 1.43 (0.55, 2.31) | 0.002 | |||

| Randomized to ATV/r (vs. EFV) | 0.38 (−0.66, 1.41) | 0.47 | |||

| Randomized to TDF/FTC (vs. ABC/3TC) | −0.38 (−1.43, 0.66) | 0.47 | |||

| Time-updated CD4 count (per 50 cells/µL higher) | −0.01 (−0.07, 0.04) | 0.60 | |||

| Time-updated HIV-1 RNA <200 c/mL (vs. Not) | −0.04 (−0.68, 0.60) | 0.90 | |||

| Week 96 to Final | Years from baseline to week 96 | 0.71 (0.50, 0.92) | <0.001 | ||

| Age (per 1 year higher) | −0.03 (−0.05, −0.01) | 0.010 | −0.03 (−0.05, −0.01) | 0.008 | |

| Male (vs. Female) | 0.70 (−0.10, 1.50) | 0.09 | 0.79 (0.11, 1.47) | 0.023 | |

| Black non-Hispanic (vs. Not) | 0.18 (−0.33, 0.68) | 0.49 | |||

| Baseline CD4 count (per 50 cells/µL higher) | −0.04 (−0.11, 0.03) | 0.29 | |||

| Baseline HIV-1 RNA (per 1 log10 c/mL higher) | 0.21 (−0.36, 0.78) | 0.47 | |||

| Randomized to ATV/r (vs. EFV) | −0.06 (−0.50, 0.38) | 0.79 | |||

| Randomized to TDF/FTC (vs. ABC/3TC) | −0.41 (−0.85, 0.02) | 0.06 | |||

| Time-updated CD4 count (per 50 cells/µL higher) | 0.05 (0.00, 0.09) | 0.053 | |||

| Time-updated HIV-1 RNA <200 c/mL (vs. Not) | 0.28 (−0.41, 0.95) | 0.42 | |||

ABC=abacavir; ATV/r=atazanavir/ritonavir; EFV=efavirenz; FTC=emtricitabine; TDF=tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; 3TC=lamivudine.

Table 2b displays the univariate and multivariable analyses of factors associated with change in total body fat in the early period. In univariate analyses, lower baseline CD4+ T-cell count and higher baseline HIV-1 RNA level were associated with greater gains in total body fat (p<0.001 and p=0.002, respectively). As was seen for lean mass, in multivariable analysis, lower baseline CD4+ T-cell count was associated with a greater increase in total body fat (p=0.001).

Covariates associated with changes in trunk and limb fat were identical to the associations with total body fat. In univariate analyses, lower baseline CD4+ T-cell count and higher baseline HIV-1 RNA level were significantly associated with greater increases in trunk fat (p=0.001 and p=0.002, respectively) and limb fat (p=0.001 and p=0.003, respectively). In multivariable analyses, lower baseline CD4+ T-cell count remained associated with greater gains in trunk fat (p=0.001) and limb fat (p=0.002).

Factors Associated with Body Composition Change in HIV-Infected Individuals During the Late Period

As shown in Table 2a, during the late period in univariate analyses, older age and black, non-Hispanic race were associated with loss of lean mass (p=0.007 and p=0.017, respectively). Both these factors remained significantly associated with loss of lean mass in multivariable analysis (p=0.002 and p=0.003, respectively).

As shown in Table 2b, older age was associated with a smaller increase in total fat in univariate analyses (p=0.010) and both older age and female sex were associated with a smaller increase in total fat in multivariable analysis (p=0.008 and p=0.023, respectively). Factors associated with changes in trunk and limb fat during the late period were similar to those associated with changes in total fat (data not shown). In the late period, there was no relationship between any HIV-related factor and change in any component of body composition.

Discussion

We compared changes in body composition over a median of approximately seven-and-a-half years after ART initiation in 97 HIV-infected individuals to changes in HIV-uninfected controls. After adjustment for potential confounders, we found that during the first 96 weeks after ART initiation HIV-infected individuals had significantly greater increases in lean mass and total fat than HIV-uninfected individuals. Consistent with a “return to health effect”, those HIV-infected individuals with a lower baseline CD4+ T-cell count and a higher HIV-1 viral load had greater increases in lean mass and total, trunk and limb fat.

In a novel finding, we found that there was a significant trajectory change in body composition in HIV-infected individuals after 96 weeks of ART. Compared to HIV-uninfected, we found that HIV-infected individuals lost lean body mass and gained fat during the late period, after controlling for potential confounders including differences in self-reported physical activity. The loss of lean mass occurred despite virologic suppression in a substantial majority of our participants. During the late period, there were no significant relationships between HIV disease-related measures such as CD4+ T-cell count and HIV-1 viral load and change in body composition. Additionally, we found no relationship between randomization to a PI in the parent study (ATV/r in A5202) and changes in body composition, in line with a recent report of similar changes in body composition between those randomized to raltegravir vs. darunavir/ritonavir or ATV/r.7 Finally, consistent with what has been reported in the general population and in other studies of HIV-infected individuals [17, 18], older age was associated with loss of lean mass during the late period.

We are not aware of any studies that have evaluated longer term changes in body composition in HIV-infected individuals after ART initiation. The majority of analyses have been limited to 48–96 weeks [7–11]. Additionally, many studies report body composition changes with older antiretroviral agents that have more metabolic side effects and mitochondrial toxicity than the agents used in our study [8, 10, 11]. The findings that HIV-infected persons gain more fat but lose lean mass after the first 96 weeks of ART compared to HIV-uninfected controls has not been reported by others. These changes might be missed in clinical care if only body mass index but not body composition is measured. The Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change in HIV infection (FRAM) Study found that HIV-infected individuals followed for five years had similar changes in muscle mass and total fat as HIV-uninfected controls [18, 19]. There are several differences between the FRAM Study and the current study that may account for the differences in results. The FRAM Study captured individuals at various stages of ART use (i.e., some individuals initiated ART during study follow-up) so some of the gain of lean mass associated with ART initiation may have been counterbalanced by the loss of lean mass that could have occurred later after ART initiation. Additionally, the FRAM Study had a larger percentage of HIV-infected women (33%) than our study (14%). In the FRAM Study, HIV-infected women appeared to have more favorable changes in muscle mass compared to men [18]. Also, 44% of FRAM participants were viremic and, for a substantial portion of study follow-up, some participants were on stavudine, an older antiretroviral drug with well described negative effects on peripheral fat [20]. Both these factors could have affected fat accumulation [21].

It is unclear mechanistically why individuals in our study would continue to gain fat but lose lean mass after the first 96 weeks of ART compared to HIV-uninfected individuals. Several studies in HIV-infected individuals have shown a relationship between elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-6 and high sensitivity C-reactive protein and fat gain and loss of lean mass [7, 22, 23]. It is possible that the chronic pro-inflammatory state that persists in treated HIV infection could account for the adverse changes in body composition seen during extended follow-up in our study.

There are several limitations of our study that deserve mentioning. Few women were enrolled in our study. The control populations were not specifically recruited for this study, and there could be unmeasured factors that could account for the difference in body composition changes seen between the HIV-infected and the control groups. We did not have data on testosterone levels, and different rates of hypogonadism could account for differences in body composition change between HIV-infected and controls. We analyzed randomization to ATV/r and to TDF/FTC as covariates in our multivariable analyses but many individuals did not remain on their originally randomly assigned study medication throughout study follow-up. The control population had a slight increase in lean mass and total fat during study follow-up. Given the relative young age of the HIV-uninfected population, these changes are similar to what have been reported elsewhere [24]. The differences in body composition change between the HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected populations were relatively modest; however, the adverse trajectory in lean mass and total fat could be compounded in persons with pre-existing wasting or if the loss continues beyond the time period we evaluated. Additionally, this was an HIV-infected study population with relatively high reported levels of physical activity; the changes in body composition may be even less favorable in more sedentary individuals.

Additionally, integrase inhibitors are now commonly used in industrialized countries as the anchor agent, and efavirenz and PIs are being less frequently used. It is unclear whether our results would extend to individuals on integrase inhibitor-containing antiretroviral regimens, although recent data suggest similar changes in body composition changes in participants on integrase inhibitors vs. newer PIs, at least over the first 96 weeks of ART [7]. We did not have data on visceral adiposity. However, studies where individuals are treated with newer antiretroviral therapies suggest that changes in visceral fat are proportional to those seen in the total and trunk fat [7]. Additionally, since we performed multiple comparisons, marginally significant associations should be interpreted cautiously.

In conclusion, we found that compared to HIV-uninfected controls, HIV-infected individuals gained more fat but lost lean mass after the first 2 years of ART. Several studies suggest that HIV-infected individuals have higher rates of frailty when compared to HIV-uninfected individuals [3, 4], and our findings could provide an explanation for these observations if the adverse body composition changes found during the late period continue beyond the time period we evaluated. Furthermore, our data suggest the need for interventions to maintain or increase lean mass and reduce fat accumulation in order to preserve physical functioning in long-term treated HIV-infected individuals.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

The project described was supported by Award Number U01AI068636 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) and also additional NIH grants [K23AI108358, UM1AI069481, UM1AI069494, K23AG050260, K23AI110532, R01AG020727, U01AI042590, K24AI120834] and support from Gilead Sciences and Viiv Healthcare. Additionally, data for the uninfected women in this manuscript were collected by three sites of the Women¹s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS): Bronx WIHS (PI: Kathryn Anastos), U01-AI-035004; Chicago WIHS (PIs: Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), Connie Wofsy Women¹s HIV Study, Northern California (PIs: Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women¹s Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

P.M.G. has received grant support (paid to institution) from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Viiv Healthcare. G.A.M. has been a consultant for Bristol-Myers and Gilead Sciences and received grant support (paid to institution) from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and Viiv Healthcare. A.C.C. is a former member of a DSMB for a study sponsored by Merck & Co., has received grant support (paid to institution) from Merck & Co., and is a past stockholder of Abbott, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer. S.L.K. has received grant support (paid to institution) from Gilead Sciences. K.M.E. has received grant support (paid to her institution) from Gilead Sciences and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. J.E.L. has served as a consultant for Gilead Sciences and GlaxoSmithKline. M.T.Y. has served as a consultant for Gilead Sciences. B.H. is an employee of Viiv Healthcare. K.M. is an employee of Gilead Sciences. T.T.B. has served as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and ViiV Healthcare.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTORS

P.M.G. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in study design, interpretation of the statistical analyses, and editing of the manuscript. D.K. performed the statistical analyses.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

D.K and B.B. have no relevant disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Erlandson KM, Li X, Abraham AG, Margolick JB, Lake JE, Palella FJ, Jr, et al. Long-term impact of HIV wasting on physical function. AIDS. 2016;30:445–454. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherzer R, Heymsfield SB, Lee D, Powderly WG, Tien PC, Bacchetti P, et al. Decreased limb muscle and increased central adiposity are associated with 5-year all-cause mortality in HIV infection. AIDS. 2011;25:1405–1414. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834884e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kooij KW, Wit FW, Schouten J, van der Valk M, Godfried MH, Stolte IG, et al. HIV infection is independently associated with frailty in middle-aged HIV type 1-infected individuals compared with similar but uninfected controls. AIDS. 2016;30:241–250. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, Phair JP, Jamieson BD, Holloway M, et al. HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1279–1286. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.11.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, MaWhinney S, Kohrt WM, Campbell TB. Functional impairment is associated with low bone and muscle mass among persons aging with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:209–215. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318289bb7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah K, Hilton TN, Myers L, Pinto JF, Luque AE, Hall WJ. A new frailty syndrome: central obesity and frailty in older adults with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:545–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McComsey GA, Moser C, Currier J, Ribaudo HJ, Paczuski P, Dubé MP, et al. Body Composition Changes after Initiation of Raltegravir or protease inhibitors: ACTG A5260s. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Jan 20;:pii. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw017. ciw017. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haubrich RH, Riddler SA, DiRienzo AG, Komarow L, Powderly WG, Klingman K, et al. Metabolic outcomes in a randomized trial of nucleoside, nonnucleoside and protease inhibitor-sparing regimens for initial HIV treatment. AIDS. 2009;23:1109–1118. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McComsey GA, Kitch D, Sax PE, Tebas P, Tierney C, Jahed NC, et al. Peripheral and central fat changes in subjects randomized to abacavir-lamivudine or tenofovir-emtricitabine with atazanavir-ritonavir or efavirenz: ACTG Study A5224s. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:185–196. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez E, Mocroft A, García-Viejo MA, Pérez-Cuevas JB, Blanco JL, Mallolas J, et al. Risk of lipodystrophy in HIV-1-infected patients treated with protease inhibitors: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2001;357:592–598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynes J, Trinh R, Pulido F, Soto-Malave R, Gathe J, Qaqish R, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir combined with raltegravir or tenofovir/emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive subjects. 96-week results of the PROGRESS study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:256–265. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sax PE, Tierney C, Collier AC, Daar ES, Mollan K, Budhathoki C, et al. Abacavir/lamivudine versus tenofovir DF/emtricitabine as part of combination regimens for initial treatment of HIV: final results. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1191–1201. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant PM, Kitch D, McComsey GA, Collier AC, Koletar SL, Erlandson KM, et al. Long-term Bone Mineral Density Changes in Antiretroviral-Treated HIV-Infected Individuals. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:607–611. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Araujo AB, Yang M, Suarez EA, Dagincourt N, Abraham JR, Chiu G, et al. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic differences in bone loss among men. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:2552–2560. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A, Tian F, Yin MT, Keller MJ, Cohen M, Tien PC. Association of regional body composition with bone mineral density in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women: women's interagency HIV study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:469–476. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826cba6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Balluz LS, Giles WH. Estimates of body composition with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1457–1465. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yarasheski KE, Scherzer R, Kotler DP, Dobs AS, Tien PC, Lewis CE, et al. Age-related skeletal muscle decline is similar in HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:332–340. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grunfeld C, Saag M, Cofrancesco J, Jr, Lewis CE, Kronmal R, Heymsfield S, et al. Regional adipose tissue measured by MRI over 5 years in HIV-infected and control participants indicates persistence of HIV-associated lipoatrophy. AIDS. 2010;24:1717–1726. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ac7a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallant JE, Staszewski S, Pozniak AL, DeJesus E, Suleiman JM, Miller MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir DF vs stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naive patients: a 3-year randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:191–201. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tien PC, Schneider MF, Cole SR, Justman JE, French AL, Young M, et al. Relation of stavudine discontinuation to anthropometric changes among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:43–48. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248353.56125.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.PrayGod G, Blevins M, Woodd S, Rehman AM, Jeremiah K, Friis H, et al. A longitudinal study of systemic inflammation and recovery of lean body mass among malnourished HIV-infected adults starting antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania and Zambia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Jan 20; doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reingold J, Wanke C, Kotler D, Lewis C, Tracy R, Heymsfield S, et al. Association of HIV infection and HIV/HCV coinfection with C-reactive protein levels: the fat redistribution and metabolic change in HIV infection (FRAM) study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48:142–148. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181685727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson AS, Janssen I, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. Longitudinal changes in body composition associated with healthy ageing: men, aged 20–96 years. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:1085–1091. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]