Abstract

Purpose of review

The purpose of this review is to describe the epidemiology of cancers that occur at an elevated rate among people with HIV infection in the current treatment era, including discussion of the etiology of these cancers, as well as changes in cancer incidence and burden over time.

Recent findings

Rates of Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and cervical cancer have declined sharply in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era, but remain elevated 800-fold, 10-fold and 4-fold, respectively, compared to the general population. Most studies have reported significant increases in liver cancer rates and decreases in lung cancer over time. While some studies have reported significant increases in anal cancer rates and declines in Hodgkin lymphoma rates, others have shown stable incidence. Declining mortality among HIV-infected individuals has resulted in the growth and aging of the HIV-infected population, causing an increase in the number of non-AIDS-defining cancers diagnosed each year in HIV-infected people.

Summary

The epidemiology of cancer among HIV-infected people has evolved since the beginning of the HIV epidemic with particularly marked changes since the introduction of modern treatment. Public health interventions aimed at prevention and early detection of cancer among HIV-infected people are needed.

Keywords: HIV, cancer, epidemiology, rates, immunosuppression, aging

Introduction

Cancer has been a major feature of the HIV epidemic from the beginning, when cases of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) were among the first reported manifestations of what later came to be known as AIDS [1-3]. Moreover, despite marked improvements in HIV treatment and outcomes, cancer continues to comprise a sizeable part of the disease burden and mortality attributable to HIV infection [4-7]. Research on the epidemiology of cancer among HIV-infected people provides important information to help public health professionals, clinicians, and patients optimize overall health outcomes in the HIV population. This research is also informative with respect to the etiologic contribution of immunosuppression, viral infections, and inflammation to the development of malignancies.

The present review describes some major features of the epidemiology of cancer among HIV-infected people. As we discuss below, there have been some notable changes over the 35-year course of the HIV epidemic. We focus on the most common cancers that are elevated in incidence among HIV-infected people, characterize recent trends, and highlight the patterns for developed countries, because most data on HIV and cancer have been collected from large cohort and registry-based studies in the United States, Europe, and Australia. Nonetheless, much of what has been learned regarding HIV and cancer in developed countries can be applied to developing countries, and we also briefly discuss the epidemiology of HIV and cancer in Africa, where the majority of HIV-infected people live.

AIDS-Defining Cancers

HIV-infected individuals have a substantially elevated risk of developing KS, certain high-grade NHLs, and cervical cancer [8, 9], all of which are considered AIDS-defining cancers, i.e., they mark the onset of clinically relevant immunosuppression. In the US during 1991-1995 (before the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART] in 1996), HIV-infected people had risks that were 2800-fold elevated for KS, 10-fold elevated for NHL, and 3-fold elevated for cervical cancer compared with the general population [8]. Due to the extraordinary elevation in KS risk, the majority of KS cases in the US during the pre-HAART era were among HIV-infected people [10]. NHL is a heterogeneous entity, and risk among HIV-infected people is most strongly elevated for the three AIDS-defining subtypes, namely, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and central nervous system lymphoma [11].

The three AIDS-defining cancers are all caused by viruses: KS-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) for KS, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) for most cases of the lymphomas closely linked to HIV, and human papillomavirus (HPV) for cervical cancer. One contribution to the high risk among HIV-infected people is the high prevalence of viral coinfection with KSHV (which is transmitted sexually, especially among men who have sex with men [MSM]) and HPV (which is transmitted sexually among both men and women). For KS and NHL, the high risk is also strongly related to advancing immunosuppression, as manifested by declines in circulating CD4 cell counts [12]. The elevated risk of cervical cancer in HIV-infected women is partly due to increased sexual acquisition of HPV and incomplete use of preventive screening. Nonetheless, HIV-infected women are less likely to clear cervical HPV than HIV-uninfected women, and some data support that risk of cervical cancer increases with declining CD4 count [12, 13]. Thus, epidemiologic evidence points to an etiologic model whereby the AIDS-defining cancers arise through loss of immunologic control of oncogenic viral infections.

Non-AIDS-Defining Cancers

HIV-infected people also have an elevated risk for certain of the remaining other (“non-AIDS-defining”) cancers, some of which are also caused by viral infections. Anal cancer is caused by HPV. Risk for this cancer is strongly elevated among HIV-infected people, particularly among MSM, who are likely to acquire anal HPV infection through sexual intercourse. During the pre-HAART era in the US, MSM with AIDS manifested an approximately 90-fold increase compared with men in the general population [14]. Risk is also elevated for Hodgkin lymphoma, especially for cases linked to EBV [8, 9]. Advancing immunosuppression contributes to risk for both anal cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma, although the relationships appear to be more complex than for KS and NHL [15, 16]. Liver cancer is also elevated among HIV-infected individuals [8, 9, 17], in large part related to a high prevalence of coinfection with hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV and HCV), which are transmitted sexually and via blood-borne routes (e.g., injection drug use). Immunosuppression appears to increase risk for HBV-related liver cancer, whereas the importance of immunosuppression in HCV-related cases is less clear [18].

HIV-infected people also have an increased risk of lung cancer. In developed countries during the pre-HAART era, lung cancer risk was 3-5 fold elevated in HIV-infected individuals compared to the general population [8, 9, 19]. This increase partly reflects a very high prevalence of tobacco use [20], and lung cancer cases that do arise are almost entirely among current or former smokers [21]. However, the elevation in lung cancer appears higher than can be explained by smoking alone [19, 21, 22]. Repeated lung infections, chronic pulmonary inflammation, and/or immunosuppression may act synergistically with tobacco to promote the development of lung cancer [12, 23]. In contrast, HIV-infected people do not have an elevated risk for other common malignancies such as colorectal, prostate, and breast cancers [8, 9]. Indeed, for unclear reasons the rates of prostate and breast cancers are significantly reduced among HIV-infected people compared to the general population.

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy

The availability of HAART in developed countries beginning in 1996 has greatly changed the clinical outlook for HIV-infected people and has had a dramatic public health impact [24-26]. Use of HAART allows for prolonged suppression of HIV replication and improved immune status, as manifested in rising CD4 counts. Widespread use of HAART at the population level has also sharply reduced the incidence of AIDS and overall mortality among HIV-infected people [24-26]. Given the strong effects on immune status and longevity, it is therefore not surprising that HAART has had a major effect on the epidemiology of cancer among HIV-infected people.

Trends in Cancer Incidence Rates in the HAART Era

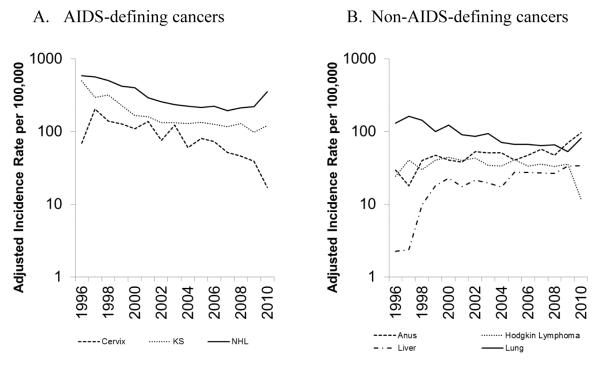

In the early HAART era, rates of KS declined 60-70% and rates of NHL declined 30-50% in HIV-infected people in the US compared to the time period immediately preceding 1996, while rates of cervical cancer remained stable [27, 28]. More recent data from studies of HIV-infected people in the US, Europe and Australia have shown continued declines in incidence rates of KS and NHL, as well as declines in cervical cancer rates [29-32]. In the US, data from the HIV/AIDS Cancer Match (HACM) Study showed average yearly declines in incidence rates of 6% for KS during 2000-2010, 5% for NHL during 2003-2010 and 12% for cervical cancer during 1996-2010 (Figure 1A). In spite of dramatic decreases in rates of AIDS-defining cancers, rates of KS, NHL and cervical cancer remain elevated 800-fold, 10-fold and 4-fold, respectively, compared to the general population [29]. A consortium of North American cohorts estimated that in the HAART era, the probability of developing cancer (i.e., cumulative incidence) by age 65 among HIV-infected people was 4% for both KS and NHL, though the cumulative incidence declined significantly across 1996-2009 [33].

Figure 1. Cancer incidence rates among HIV-infected people in the United States (HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study, 1996-2010).

Time trends in incidence rates of A) AIDS-defining cancers (Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and cervical cancer); and B) non-AIDS-defining cancers (anal cancer, liver cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma and lung cancer). Rates were estimated with data from the HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study and standardized to the 2002 HIV population by age, sex, HIV risk group, race/ethnicity, and time since HIV/AIDS registration. Figures were generated with data from Robbins et al. [29].

Incidence rates of some non-AIDS-defining cancers have also changed during the HAART era. In the HACM Study, anal cancer rates increased 3% per year during 1996-2010 [29] (Figure 1B), reflecting increasing rates in the general U.S. population [29], while other studies reported no change in incidence rates over time or increases only among women [30, 31, 34, 35]. Most studies reported significant increases in liver cancer rates over time (6% per year in the HACM Study) [10, 29, 34], and significant decreases in lung cancer rates (-6% per year) (Figure 1B) [22, 29, 31, 34], though other studies reported no changes in the rates of these cancers over time [30, 35]. Decreasing rates of Hodgkin lymphoma were reported in some studies (-3% per year in the HACM Study) (Figure 1B) [17, 29], while another study reported a 50% decline in Hodgkin lymphoma rates from 1997-2000 to 2001-2004 followed by a flat trend [32], and others observed no significant change over time [34, 35]. In the US during 2006-2010, HIV-infected people continued to have elevated rates for anal cancer (32-fold elevation compared to the general population), lung cancer (2-fold), liver cancer (3-fold) and Hodgkin lymphoma (10-fold) [29]. In the HAART era, the probability of HIV-infected people in North America developing these cancers by age 65 was 1.3% for anal cancer, 2.2% for lung cancer, 0.8% for liver cancer and 0.9% for Hodgkin lymphoma [33].

Cancer Burden in HIV-Infected People

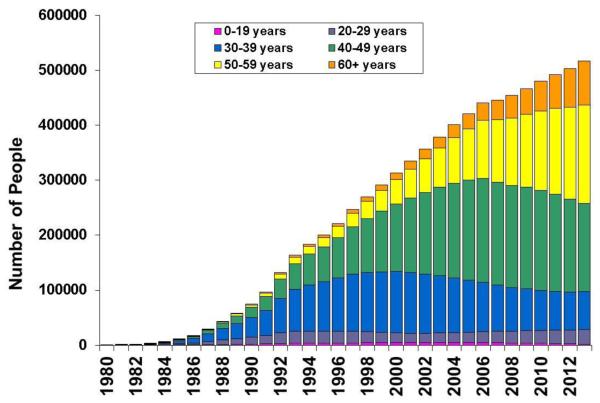

With the longevity afforded by modern treatment, a 20 year-old infected with HIV today now has a projected life expectancy that is similar to that observed in the general population [36]. Declines in mortality among HIV-infected individuals have resulted in the growth and aging of the HIV-infected population, which has implications for current and future cancer risk and the total burden of cases. In the US, the number of people living with AIDS more than doubled from 242,000 in 1996 to 516,401 in 2013 (Figure 2), and the entire HIV-infected population increased from 818,638 in 2008 to 933,941 in 2013 (US nationwide estimates are only available for all HIV-infected people in the most recent years) [37-39]. Further, the age distribution of people living with HIV has shifted to older ages over time. For example, in 1996, 2.5% of people with AIDS in the US were ≥60 years old, compared to 15.4% in 2013 [38].

Figure 2. Number of people living with AIDS in the US, 1980-2013.

People living with AIDS in the United States, 1996-2013. Colored segments of each bar represent the number of people in each age group. Data were provided by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Figure is an updated version of a figure published in Shiels et al. [40].

Because cancer risk increases with age, and the HIV population is growing, the burden of HIV-infected people with cancer has also grown markedly. One prior US study, focused on people with AIDS, estimated changes in the cancer burden over time, and found that while the number of cases of KS and NHL has declined over time (driven by the sharply decreasing incidence rates), the total number of cases for each non-AIDS-defining cancer increased over time, largely driven by the growth and aging of the HIV population, as well as increasing cancer rates for some sites [40]. This pattern was seen for both non-AIDS-defining cancers that are elevated among people with HIV (e.g., anal and lung cancers), as well as cancers that are common in the general population but do not occur more frequently in people with HIV (e.g., breast and prostate cancers). The total number of non-AIDS-defining cancers has exceeded the number of AIDS-defining cancers since 2003 among people with AIDS, highlighting the changing spectrum of cancers diagnosed in this population (Figure 3) [40]. In the US in 2010, the most common cancers diagnosed among HIV-infected were NHL (n=1650; 21% of incident cancer cases) and KS (n=910; 12%), but these were followed closely by lung cancer (n=840; 11%), anal cancer (n=760; 10%), and prostate cancer (n=570; 7%) [5]. As the HIV-infected population continues to grow and age, the burden of cancer (particularly non-AIDS-defining cancers) will continue to rise, as will the need for cancer prevention, early detection and treatment.

Figure 3. Cancer burden in the US AIDS population, 1990-2005.

Total number of cancer cases (i.e., cancer burden) among people with AIDS in the United States, 1990-2005. Bars represent the total number of cases occurring in each year, stratified by type of cancer (left axis). Dark gray bars represent AIDS-defining cancers, light gray bars represent non-AIDS-defining cancers and black bars represent poorly specified cancers. Points connected by lines represent overall cancer incidence rates, standardized by age group, race and sex to the 2000 AIDS population in the United States (right axis). The figure was previously published in Shiels et al. [40].

HIV and Cancer in the Developing World

In sub-Saharan Africa, where a large proportion of all HIV-infected people reside, KS and cervical cancer are among the most common cancers [41, 42]. As in developed countries, risk for all three AIDS-defining cancers is elevated among HIV-infected people in Africa [43-45], and the onset of the HIV epidemic led to a dramatic increase in KS incidence [46]. The greatly expanding access to HAART in recent years, made possible through international assistance programs, will hopefully lead to a reduction in the incidence of AIDS-defining cancers over time. Most African countries lack population-based cancer registry data that allow an assessment of cancer burden. Nonetheless, analyses of incidence data from cancer registries in Uganda and Botswana provide evidence for recent declines in KS that are temporally associated with uptake of HAART [47, 48].

Conclusions

The epidemiology of cancer among HIV-infected people has evolved since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, tracking strong patterns in cancer incidence rates and dynamic population demographics preceding and following the introduction of modern HIV treatment. However, much more epidemiologic research is needed. Little is known yet about cancer risks among people living with HIV for decades. Studies must continue to monitor cancer rates over time in the HIV-infected population, and estimates of future rates and burden are needed to identify targets for cancer prevention and early detection, as well as to guide resource allocation. Further, more information is needed on the risk of cancer among HIV-infected people living in the developing world, particularly in Africa, where the HIV epidemic is most concentrated. Large, population-based studies in many of these countries are difficult due to the lack of national and regional registration of HIV and cancer, and resources and expertise in disease surveillance are needed.

Finally, public health interventions aimed at the prevention and early detection of cancer are needed to reduce cancer risk among HIV-infected people. Current guidelines recommend that all HIV-infected people receive treatment with antiretroviral therapy [49]. Increasing the fraction of people in care could further decrease rates of NHL and KS. Additional public health interventions such as smoking cessation programs and treatment of HBV and HCV could also reduce the cancer burden in this population. For most other cancer sites, HIV-infected individuals should follow the same age-based screening guidelines as the general population, though separate guidelines have been issued for Pap testing for the prevention of cervical cancer in HIV-infected women [50], and a clinical trial is currently assessing the utility of Pap testing and treatment of precursor lesions for anal cancer prevention in HIV-infected men and women (NIH clinical trials identification number: NCT02135419).

Key points.

People with HIV have an elevated risk of a number of cancer types, including AIDS-defining cancers (Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, cervical cancer) and selected non-AIDS-defining cancer (e.g., anal cancer, liver cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma and lung cancer).

Rates of AIDS-defining cancers have declined since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996.

Most studies report increases in liver cancer and decreases in lung cancer rates in the HAART era. While some studies have reported increases in anal cancer rates and decreases in Hodgkin lymphoma rates over time, others have reported no change in incidence.

Due to the growth and aging of the HIV-infected population in the US, the number of non-AIDS-defining cancers diagnosed in this population is growing each year.

Public health interventions aimed at the prevention and early detection of cancer are needed to reduce the impact of cancer among HIV-infected people.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was funded by the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Kaposi’s sarcoma and Pneumocystis pneumonia among homosexual men- -New York City and California. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30:305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diffuse, undifferentiated non-Hodgkins lymphoma among homosexual males--United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31:277–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziegler JL, Drew WL, Miner RC, Mintz L, Rosenbaum E, Gershow J, et al. Outbreak of Burkitt’s-like lymphoma in homosexual men. Lancet. 1982;2:631–633. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92740-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Gail MH, Hall HI, Li J, Chaturvedi AK, et al. Cancer burden in the HIV-infected population in the United States. J Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011;103:753–762. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins HA, Pfeiffer RM, Shiels MS, Li J, Hall HI, Engels EA. Excess cancers among HIV-infected people in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju503.* This is the only study that quantifies the excess number of cancers occurring among HIV-infected people in the U.S. relative to the general population.

- 6.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Morlat P, Pradier C, Reiss P, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet. 2014;384:241–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60604-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marin B, Thiebaut R, Bucher HC, Rondeau V, Costagliola D, Dorrucci M, et al. Non-AIDS-defining deaths and immunodeficiency in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2009;23:1743–1753. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e9b78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engels EA, Biggar RJ, Hall HI, Cross H, Crutchfield A, Finch JL, et al. Cancer risk in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Int. J Cancer. 2008;123:187–194. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Hall HI, Li J, Goedert JJ, Morton LM, et al. Proportions of Kaposi sarcoma, selected non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and cervical cancer in the United States occurring in persons with AIDS, 1980-2007. JAMA. 2011;305:1450–1459. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson TM, Morton LM, Shiels MS, Clarke CA, Engels EA. Risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes in HIV-infected people during the HAART era: a population-based study. AIDS. 2014;28:2313–2318. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guiguet M, Boue F, Cadranel J, Lang JM, Rosenthal E, Costagliola D. Effect of immunodeficiency, HIV viral load, and antiretroviral therapy on the risk of individual malignancies (FHDH-ANRS CO4): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1152–1159. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strickler HD, Burk RD, Fazzari M, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Massad LS, et al. Natural history and possible reactivation of human papillomavirus in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:577–586. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaturvedi AK, Madeleine MM, Biggar RJ, Engels EA. Risk of human papillomavirus-associated cancers among persons with AIDS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biggar RJ, Jaffe ES, Goedert JJ, Chaturvedi A, Pfeiffer R, Engels EA. Hodgkin lymphoma and immunodeficiency in persons with HIV/AIDS. Blood. 2006;108:3786–3791. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertisch B, Franceschi S, Lise M, Vernazza P, Keiser O, Schoni-Affolter F, et al. Risk factors for anal cancer in persons infected with HIV: a nested case-control study in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:877–884. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahasrabuddhe VV, Shiels MS, McGlynn KA, Engels EA. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in the United States. Cancer. 2012;118:6226–6233. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clifford GM, Rickenbach M, Polesel J, Dal Maso L, Steffen I, Ledergerber B, et al. Influence of HIV-related immunodeficiency on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. AIDS. 2008;22:2135–2141. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831103ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaturvedi AK, Pfeiffer RM, Chang L, Goedert JJ, Biggar RJ, Engels EA. Elevated risk of lung cancer among people with AIDS. AIDS. 2007;21:207–213. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280118fca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park LS, Hernandez-Ramirez RU, Silverberg MJ, Crother K, Dubrow R. Prevalence of non-HIV cancer risk factors in persons living with HIV/AIDS: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2016;30:273–291. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000922.** This is an excellent review and meta-analysis of cancer risk factors among HIV-infected people and the general population.

- 21.Engels EA, Brock MV, Chen J, Hooker CM, Gillison M, Moore RD. Elevated incidence of lung cancer among HIV-infected individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1383–1388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiels MS, Cole SR, Mehta SH, Kirk GD. Lung cancer incidence and mortality among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:510–515. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f53783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engels EA. Inflammation in the development of lung cancer: epidemiological evidence. Expert. Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:605–615. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Detels R, Munoz A, McFarlane G, Kingsley LA, Margolick JB, Giorgi J, et al. Effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy on time to AIDS and death in men with known HIV infection duration. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study Investigators. Jama. 1998;280:1497–1503. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.17.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole SR, Hernan MA, Robins JM, Anastos K, Chmiel J, Detels R, et al. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on time to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or death using marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:687–694. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel P, Hanson DL, Sullivan PS, Novak RM, Moorman AC, Tong TC, et al. Incidence of Types of Cancer among HIV-Infected Persons Compared with the General Population in the United States, 1992-2003. Ann.Intern.Med. 2008;148:728–736. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engels EA, Biggar RJ, Hall HI, Cross H, Crutchfield A, Finch JL, et al. Cancer risk in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. International Journal of Cancer. 2008;123:187–194. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robbins HA, Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Engels EA. Epidemiologic contributions to recent cancer trends among HIV-infected people in the United States. AIDS. 2014;28:881–890. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel P, Armon C, Chmiel JS, Brooks JT, Buchacz K, Wood K, et al. Factors associated with cancer incidence and with all-cause mortality after cancer diagnosis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons during the combination antiretroviral therapy era. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1:1–12. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park LS, Tate JP, Sigel K, Rimland D, Crothers K, Gibert C, et al. Time trends in cancer incidence in persons living with HIV/AIDS in the antiretroviral therapy era: 1997-2012. AIDS. 2016;30:1795–1806. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hleyhel M, Belot A, Bouvier AM, Tattevin P, Pacanowski J, Genet P, et al. Risk of AIDS-defining cancers among HIV-1-infected patients in France between 1992 and 2009: results from the FHDH-ANRS CO4 cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1638–1647. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Achenbach CJ, Jing Y, Althoff KN, D’Souza G, et al. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer Among Persons With HIV in North America: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:507–518. doi: 10.7326/M14-2768.** This study uniquely estimates the cumulative incidence of cancer among HIV-infected people using data from a consortium of HIV cohorts in North America.

- 34.Hleyhel M, Hleyhel M, Bouvier AM, Belot A, Tattevin P, Pacanowski J, et al. Risk of non-AIDS-defining cancers among HIV-1-infected individuals in France between 1997 and 2009: results from a French cohort. AIDS. 2014;28:2109–2118. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Worm SW, Bower M, Reiss P, Bonnet F, Law M, Fatkenheuer G, et al. Non-AIDS defining cancers in the D:A:D Study--time trends and predictors of survival: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:471. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, Modur SP, Althoff KN, Buchacz K, et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 1997;9(No. 2):30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed June 30, 2016];HIV Surveillance Report. 2014 26 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/. Published November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed June 30, 2016];HIV Surveillance Report. 2011 23 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/. Published February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Gail MH, Hall HI, Li J, Chaturvedi AK, et al. Cancer burden in the HIV-infected population in the United States. J.Natl.Cancer Inst. 2011;103:753–762. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, Hamavid H, Moradi-Lakeh M, MacIntyre MF, et al. The Global Burden of Cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:505–527. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Jemal A. Cancer in Africa 2012. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:953–966. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sitas F, Pacella-Norman R, Carrara H, Patel M, Ruff P, Sur R, et al. The spectrum of HIV-1 related cancers in South Africa. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:489–492. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001101)88:3<489::aid-ijc25>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mbulaiteye SM, Katabira ET, Wabinga H, Parkin DM, Virgo P, Ochai R, et al. Spectrum of cancers among HIV-infected persons in Africa: The Uganda AIDS-Cancer Registry Match Study. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;118:985–990. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanon A, Jaquet A, Ekouevi DK, Akakpo J, Adoubi I, Diomande I, et al. The spectrum of cancers in West Africa: associations with human immunodeficiency virus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wabinga HR, Parkin DM, Wabwire-Mangen F, Nambooze S. Trends in cancer incidence in Kyadondo County, Uganda, 1960-1997. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1585–1592. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mutyaba I, Phipps W, Krantz EM, Goldman JD, Nambooze S, Orem J, et al. A Population-Level Evaluation of the Effect of Antiretroviral Therapy on Cancer Incidence in Kyadondo County, Uganda, 1999-2008. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:481–486. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dryden-Peterson S, Medhin H, Kebabonye-Pusoentsi M, Seage GR, 3rd, Suneja G, Kayembe MK, et al. Cancer Incidence following Expansion of HIV Treatment in Botswana. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135602.* Data on HIV and cancer in Africa are sparse. This study provides a unique examination of cancer incidence in Botswana.

- 49.Department of Health and Human Services . Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adulst and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunisitc infections in HIV-infected adulst and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Published 2016.