Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome resulting from diverse primary and secondary causes, and shared pathways of disease progression, correlating with substantial mortality, morbidity and cost. HF in children is most commonly attributable to coexistent congenital heart disease (CHD), with different risks depending on the specific type of malformation. Current management and therapy for HF in children are extrapolated from treatment approaches in adults. This review discusses the causes, epidemiology and manifestations of HF in children with CHD, and presents the clinical, genetic and molecular characteristics that are similar or distinct from adult HF. The objective of this review is to provide a framework for understanding rapidly increasing genetic and molecular information in the challenging context of detailed phenotyping. We review clinical and translational research studies of HF in CHD including at the genome, transcriptome, and epigenetic levels. Unresolved issues and directions for future study are presented.

Keywords: cardiac failure, ventricular dysfunction, cardiovascular malformation, genetics, pediatrics

Subject Terms: Congenital heart failure, Pediatrics

Overview

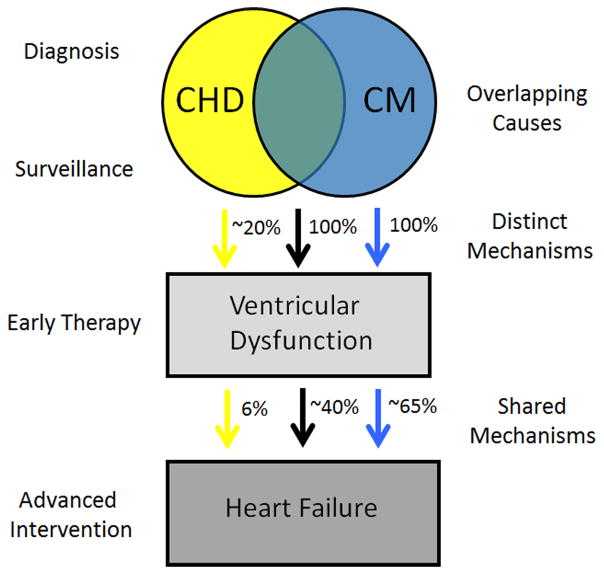

The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation defines pediatric heart failure (HF) as “a clinical and pathophysiologic syndrome that results from ventricular dysfunction, volume, or pressure overload, alone or in combination. In children, it leads to characteristic signs and symptoms, such as poor growth, feeding difficulties, respiratory distress, exercise intolerance, and fatigue, and is associated with circulatory, neurohormonal, and molecular abnormalities.” 1 Congenital heart disease (CHD) is frequently associated with ventricular dysfunction, volume or pressure overload. HF in pediatric patients with CHD has various causes, some of which overlap with the causes of cardiomyopathy, resulting in both distinct and shared mechanisms leading to ventricular dysfunction and the clinical manifestation of HF (Figure 1). In this review, we focus on basic, translational, and clinical research as it applies to HF in pediatric patients with CHD.

Figure 1. Model of the relationship of heart failure to congenital heart disease and cardiomyopathy.

Three phenotypes are shown: CHD (yellow), CM (blue), and CHD with CM (brown). Cardiomyopathy by definition results in ventricular dysfunction in 100% of cases. CHD results in ventricular dysfunction in approximately 20% of cases, while coexisting CHD and CM results in ventricular dysfunction in 100% of cases. HF results in ~65%, 6% and ~40% respectively. Ventricular dysfunction, either systolic or diastolic, precedes HF and therefore offers opportunities for early intervention. Causes of HF may vary despite common clinical features (different colored arrows).

I. Diagnosis and epidemiology

Defining HF in children with CHD presents significant challenges

HF is defined by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology as a “complex clinical syndrome that can result from any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill or eject blood.”2 The criteria for the diagnosis of HF are largely clinical, and several standardized diagnostic classification systems have been proposed.3 Pediatric HF encompasses a broader range of associated findings than adult HF in part because of the variety of ages of presentation. As a clinical entity, HF is further subdivided based on its onset, acuity, and severity. The well-known New York Heart Association Heart Failure Classification does not apply well to children and on a practical level is thought to lack the sensitivity needed to assess and capture the progression of HF severity in children. For this reason, the Ross Heart Failure Classification was developed for the assessment of infants with HF, and a modified Ross Classification was developed to apply to additional age ranges of children.4 The New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index provides a weighted score (Table 1). 5 In pediatric practice, these classification systems are not widely used. As discussed in subsequent sections, this creates specific challenges for research.

Table 1.

Classification Approaches to Heart Failure

| NYHA | Modified Ross | NYU PHFI * |

|---|---|---|

| I asymptomatic | I asymptomatic | 0–7 asymptomatic to minimal signs and symptoms |

| II slight or moderate limitation of physical activity | II mild tachypnea or diaphoresis with feeding in infants; dyspnea on exertion in older children | 8–14 moderate signs and symptoms |

| III marked limitation of physical activity | III marked tachypnea or diaphoresis with feeding in infants; marked dyspnea on exertion; prolonged feeding times with growth failure | 15–21 Advanced signs and symptoms and modest use of medication |

| IV symptoms at rest | IV tachypnea, retractions, grunting or diaphoresis at rest | 22–30 advanced signs and symptoms and liberal use of medicine |

HF severity is determined from signs and symptoms, medical regimen, and ventricular physiology. A total score can range from zero (no heart failure) to 30 (severe heart failure) and is derived by adding 1 or 2 points for each of 13 individual criterion.5

The clinical presentation of CHD is described primarily in physiologic terms, for example outflow tract obstruction (pressure overload) or pulmonary over circulation (volume overload). The treatment of CHD is typically surgical correction (anatomic) and because “HF” lacks specificity in this context, the term ventricular dysfunction is often used. However, ventricular dysfunction may be associated with poor contractility (systolic dysfunction) or poor relaxation (diastolic dysfunction), with or without the clinical presence of HF, thus creating a semantic challenge that spans clinical and research efforts in pediatric cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery. Considerable practice variation across centers significantly confounds this problem. Even large multi-center groups, including the Pediatric Heart Network (PHN), Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry (PCMR), Pediatric Cardiac Genomics Consortium (PCGC) and National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative (NPC-QIC) use different approaches to identify HF and classify severity, creating unintended inconsistencies in the literature, ultimately resulting in studies that are difficult to reconcile. For example, the PHN, the field’s premier multisite network, has used different approaches to classifying cardiac dysfunction or HF in different studies, such as comparing function between groups without distinguishing dysfunction,6 using the Ross criteria,7 or focusing on imaging evidence of dysfunction without commenting on HF.8 While there are valid reasons for these specific differences in study design, the lack of a unified approach to ventricular dysfunction and HF confounds integrated analyses of the collective literature. The small population sizes available for each specific type of CHD further hamper the ability to make generalizable observations. Together, these observations illustrate that primary challenges in the field are overcoming practice variation and standardizing phenotyping. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that it is feasible to work toward a solution using the multiple existing networks and consortia to optimize the utility of data already collected in these large cohorts.

The epidemiology of pediatric HF is poorly understood

Factors that have contributed to difficulties in compiling accurate incidence and prevalence estimates for pediatric HF include the lack of standardized phenotyping for both CHD and HF and the diversity of causes of HF in children with CHD. HF has been a major public health problem for decades. In the United States, more than 550,000 new cases are diagnosed each year and the overall prevalence is greater than 6 million individuals.2 Pediatric HF contributes substantially to the economic impact of this disease as a result of the frequent need for procedure based intervention and the significant morbidity and mortality.9 Children whose hospitalizations are complicated by HF have over a 20-fold increased risk of death.10 It is estimated that 11,000–14,000 children will be hospitalized with HF annually in the United States.10, 11 These numbers include children with cardiomyopathy, with an annual incidence estimated at 1.13 cases per 100,000 children12 and children with CHD, with a traditionally cited incidence of 8 per 1000 live births and a need for cardiac intervention in 3 of every 1000 newborns.13 There have been no comprehensive epidemiologic studies addressing HF in the pediatric population in the United States, but two single site studies in Europe indicate that more than half of the pediatric HF cases were in children with CHD.14, 15 In these studies, there were differences in the rate of HF in their CHD populations, with one study identifying HF in 10.4% of all patients with congenital and acquired heart disease and the other identifying HF in 34%, suggesting differences in study design or HF definitions.14, 15 Within the CHD populations, the rate of HF was 6.2% and 39%, respectively.

CHD is the most common cause of HF in children

HF has numerous etiologies that are a consequence of cardiac and non-cardiac disorders, either congenital or acquired.1 In the pediatric population, rheumatic fever was the most common cause of HF in children in the US in the 1950s and continues to be a common cause of pediatric HF in developing countries (Table 2). Traditionally, HF has been synonymous with cardiomyopathy in the literature of pediatric heart disease, but over time it became clear that cardiomyopathy is but one cause of HF. Although the proportion of CHD patients with HF is lower than the proportion with rhythm disturbances or cardiomyopathy, CHD is a much more common disease and therefore contributes a greater number of cases to the overall HF count. Nearly 60% of HF cases in pediatric patients occurred within the first year of life, but in these studies the overall mortality was lower in the CHD population than in patients with HF from other causes. 14, 15 The fact that the risk of HF varied depending on the underlying cause raises the fundamental question of whether HF is the same disease process across the spectrum of age ranges and precipitating causes. In addition, it suggests that there may be the potential for risk stratification and customization of therapy.

Table 2.

Causes of Heart Failure in Children

| Congenital heart disease | Left to right shunts (e.g. VSD) Conotruncal lesions (e.g. TOF) Single ventricle lesions (e.g. HLHS) Valve disease (e.g. AS) |

| Cardiomyopathy (primary) | HCM DCM RCM ARVC LVNC |

| Arrhythmia | Tachycardias (e.g. supraventricular tachycardia) Bradycardias (e.g. complete AV block) |

| Infection | Myocarditis Acute rheumatic fever HIV |

| Ischemia | Coronary anomaly (e.g. myocardial bridge) Kawasaki disease |

| Toxin | Chemotherapy Maternal drugs during pregnancy |

| Other | Diabetes mellitus Essential Hypertension |

ARVC Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy, AS Aortic Stenosis, AV atrioventricular, DCM Dilated Cardiomyopathy, HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus, HCM Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, HLHS Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome, LVNC Left Ventricular Noncompaction, RCM Restrictive Cardiomyopathy, TOF Tetralogy of Fallot, VSD Ventricular Septal Defect

HF is a common morbidity identified in the adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) population, an age range complicated by additional factors and not covered in many pediatric studies. HF is known to occur in approximately 25% of ACHD patients by the age of 30, and the incidence increases with age.16 Tracking the natural history of specific CHD types or specific genetic causes, and comparing the similarities and differences of HF in children and adults, promises to provide insight into the risk of HF at the time of diagnosis in childhood. Taken together, these data indicate that HF is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in pediatric and ACHD, and HF in this population is heterogeneous with regard to underlying cause and outcome. The issues emerging in the management of the growing ACHD population have been reviewed recently.17–20 Herein, we focus specifically on children with CHD and HF.

II. Overlapping causes

Mutations that cause cardiomyopathy can also cause CHD

Recent data indicate that mutations in sarcomeric genes are associated with CHD in addition to cardiomyopathy.21 Mutations in specific protein domains of the MYH7 gene cause Ebstein anomaly in addition to causing cardiomyopathy.22 Interestingly, in the original description, 6% of a cohort of patients with Ebstein anomaly, a defect of tricuspid valve formation and position, had MYH7 mutations, of whom 75% had left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC). In their families, the familial MYH7 mutation was also identified in individuals with other types of CHD and in individuals with isolated LVNC, but was not found in unaffected family members. These cases illustrate that CHD and cardiomyopathy phenotypes occur with variable expressivity in family members carrying the same disease causing mutation, suggesting that other factors, including genetic modifiers, can influence phenotypic expression. LVNC is known to be associated with specific types of CHD in a subset of cases.23–25 LVNC is characterized by abnormal and excessive ventricular trabeculation and a thin-walled myocardium. While mutations in sarcomeric genes have been associated with the LVNC phenotype, mutations in developmental signaling pathways long known to be associated with CHD such as the Notch pathway and noncanonical Wnt signaling also cause LVNC in animal models and humans.26–28 Given the developmental importance of these signaling pathways for cardiogenesis, future research investigating the shared developmental mechanisms leading to both CHD and cardiomyopathy from disruption in these pathways will likely be informative.

In addition to the MYH7 gene, mutations in other sarcomeric genes can cause both CHD and cardiomyopathy. Mutations in MHY6, encoding α myosin heavy chain, cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), familial atrial septal defect, and sick sinus syndrome.29 Similarly, mutations in ACTC1, encoding α cardiac actin, a component of the thin filament of the sarcomere, can cause cardiomyopathy and/or septal defects.30, 31 Mutations in MYBPC3 and TNNI3 have also been described with both CHD and cardiomyopathy.32 Surprisingly, sarcomeric gene mutation analysis has not been applied to the CHD population in a comprehensive manner to determine whether rare variants or common polymorphisms in these genes might be associated with ventricular function. Whether patients who have CHD with myocardial dysfunction that is out of proportion to their heart defect might have a primary heart muscle disease is unknown. Studies to analyze the natural history of patients with mutations in sarcomeric genes and CHD are necessary in order to assess the penetrance of left ventricular dysfunction or cardiomyopathy in these patients.

Genetic syndromes associated with CHD also cause cardiomyopathy

The development of the heart is under genetic control and CHD is primarily a genetic disease, although teratogens may independently cause malformation and maternal factors may contribute to disease manifestation.33, 34 The genetic causes of CHD include chromosome abnormalities, genomic disorders, single gene causes, and multifactorial causes.34–36 Overall, the likelihood of identifying the genetic cause of CHD is less than for cardiomyopathy (Table 3). In part, this stems from the fact that cardiomyopathy most often illustrates Mendelian inheritance in an autosomal dominant pattern. CHD, in contrast, is most often multifactorial with a complex interplay of multiple genes and environment contributing a susceptibility to the development of a structural defect.34, 35 An exception to this is syndromic CHD, in which the diagnostic rate is higher. Genetic syndromes are often associated with specific classes of cardiovascular malformations, but phenotypic heterogeneity is common. In addition to this variability, these cases illustrate occasional non-penetrance of cardiac defects that is not well understood. Overall, genetic syndromes have been tremendously informative for identifying genes that cause CHD.37–41 The paradigm that understanding the genetic basis of syndromic CHD can identify important genes that cause or modify isolated CHD is conceptually important.

Table 3.

Comparison of Congenital Heart Disease and Cardiomyopathy Genetics in Children

| Congenital Heart Disease | Cardiomyopathy | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Syndromic and nonsyndromic (isolated) forms approximately 30% and 70%, respectively | Syndromic and nonsyndromic forms approximately 30% and 70%, respectively |

| Inheritance pattern | Multifactorial>Mendelian; complex trait most common | Mendelian>Multifactorial; autosomal dominant most common |

| Decreased penetrance | Common | Less common |

| Variable expressivity | Common | Common |

| Diagnosis | CMA, WES/WGS, NGS panels | NGS panels |

| Diagnostic yield | CMA: 3–25% in syndromic; 3–10% in isolated WES/WGS: up to 10% de novo mutation rate NGS panels: unknown |

30–70% depending on type of cardiomyopathy |

| Genes | Encode transcription factors, developmental signaling pathways, chromatin remodeling, structural proteins of the contractile apparatus | Encode structural proteins of the contractile apparatus, ion channels, signaling pathways, metabolic function |

CMA, Chromosome Microarray; NGS, Next Generation Sequencing; WES, Whole Exome Sequencing; WGS, Whole Genome Sequencing

Several genetic conditions with highly penetrant CHD are also associated with HF and/or cardiomyopathy. For example, Noonan syndrome, an autosomal dominant genetic condition characterized by short stature, cardiac defects, and dysmorphic features, is caused by mutations in genes within the RAS/MAPK pathway.42 These patients may show evidence of HCM, CHD (classically pulmonary valve stenosis), or both.43 There is a lifelong risk for development of HCM with Noonan syndrome, necessitating ongoing cardiac surveillance even in affected individuals without CHD. Other RASopathies include Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, Costello syndrome, and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigenes (NSML; formerly LEOPARD) syndrome. NSML is usually caused by mutations in PTPN11, a protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 that regulates the RAS/MAPK cascade. Mutations in PTPN11 are also the most common cause of Noonan syndrome, where they result in constitutive activation of the protein. In contrast, in NSML, mutations in PTPN11 render the protein catalytically impaired. Greater than 80% of patients with NSML have HCM that is caused by hyperactivation of the AKT/mTOR pathway. Using a mouse model of NSML, the ability to prevent HCM was investigated by early treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. Mice treated early did not develop HCM, and those treated at later stages demonstrated reversal of disease.44 Recently, the first trial of a mTOR inhibitor was reported in an infant with NSML and rapidly progressive HCM with a goal of halting progression of hypertrophy and outflow tract obstruction until the time of transplant.45 An understanding of the genetic basis of HF in this case led to trial of a pathway specific inhibitor for treatment.

Marfan syndrome (MFS), a connective tissue disorder caused by mutations in an ECM protein encoded by FBN1,46 is another syndrome for which new data implicate a propensity to HF in a subset of affected individuals. Mutations in fibrillin-1 lead to an upregulation of TGFβ signaling in individuals with MFS. The structural network of the microfibril controls the release of signaling molecules important for morphogenesis and tissue homeostasis. Case reports documenting the development of left ventricular dysfunction or DCM in patients with MFS suggest a potential overlap in molecular networks controlling cardiac function. Using a mouse model of MFS, it was determined that DCM in fibrillin-1 deficient mice results from abnormal mechanosignaling by cardiomyocytes.47 Specifically, the mice spontaneously developed increased angiotensin II type I receptor signaling and loss of focal adhesion kinase activity in the absence of aortic or valvular disease. An additional study identified two distinct phenotypes in aged Marfan mice, one of which was LV enlargement associated with elevated ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK phosphorylation and higher BNP expression.48 The variable phenotypic responses noted in this study parallel the small subset of MFS patients who develop DCM. Combined approaches using genomics, mouse models, and patient oriented research will be required to dissect the complex interactions that underlie this phenotypic variability.

III. Surveillance

The development of HF in CHD is dependent on age and lesion type

While genetic causes of CHD or cardiomyopathy can identify children at high risk of developing HF, this occurs in a minority of cases. Clinical factors related to phenotype and presentation remain the most common means for evaluating risk and instituting surveillance for HF. Age is an important factor in assessing clinical features of HF. In the fetus, HF is characterized by decreased fetal movement, pericardial effusion and ascites.49 In the preterm low birth weight newborn, HF is characterized by acidemia, anemia and hypoxemia. In the term newborn, tachypnea, fatigue with feedings, and decreased urine output are common symptoms of HF. Decompensation at this age is often rapid, with the infant moving from asymptomatic to cardiac shock quickly in part due to the decreased cardiac reserve at this age.50, 51 Accordingly, more classic signs of HF, such as edema and pathologic pulses, are less common and often not present. The timing of HF is a clue to the underlying malformation. For example, HF in HLHS develops on day 3–7 of life, while HF in severe coarctation of the aorta tends to develop on days 7–10. Some CHD types do not manifest HF until after the pulmonary vascular resistance decreases, e.g. a large ventricular septal defect (VSD) or an atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), in which case HF develops in 1–3 months. But other lesions, such as an atrial septal defect, do not lead to symptoms until 3–5 years of life, if at all. While some of these observations simply reflect the underlying anatomy and physiology, it is increasingly recognized that additional factors, including both genes and environment, contribute to the timing of the onset of disease.

Lesion type is another factor useful for risk stratification for HF. HF in patients with CHD is typically attributed to concomitant pressure or volume overload. Therefore, infants with specific types of CHD will universally experience HF without surgical correction, e.g. critical aortic stenosis (pressure overload) or Ebstein anomaly with severe tricuspid regurgitation (volume overload). However, genetic factors, as well as various environmental triggers, are implicated in the complex process leading to HF. Accordingly, identifying new-onset ventricular dysfunction is important for emerging early intervention strategies. In general, children beyond the first year of life have better overall health and greater cardiac reserve than adults and can remain in a compensated state for longer periods, but tend to transition rapidly to acute HF. The proportion of cases of specific types of CHD that have ventricular dysfunction or HF at the time of diagnosis varies. For example, pulmonary insufficiency in a patient with repaired TOF may or may not lead to ventricular dysfunction and HF, and the ability to predict these events is limited. The higher the rate of HF at diagnosis, the higher the risk for HF later in life.16 Coordinated lesion-specific approaches to HF may provide enhanced surveillance algorithms.

Standardized and detailed phenotyping is critical

Specific types of CHD universally result in HF that can be addressed by surgical repair. Functional single ventricle (SV) lesions (a variety of malformations grouped for their common physiology whereby one ventricle is under developed and the other ventricle supports both pulmonary and systemic circulations), have the highest incidence of ventricular dysfunction and HF at the time of diagnosis, followed by conotruncal lesions (e.g. tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great arteries), left to right shunts (e.g. VSD, AVSD) and valve disease (e.g. aortic stenosis, pulmonary insufficiency). In some cases, decisions about the timing of surgery are based on balancing the need for the infant to age and grow and the morbidities associated with HF, including poor growth. Post-surgically, identifying patients at risk for persistent ventricular dysfunction or HF is confounded by a number of factors including the heterogeneity within groups of lesions, surgery-specific factors, and differences in medical management. Approaches to improve our ability to identify patients at risk for HF pre- and post-surgically are needed. Analyzing outcomes within subgroups of large multi-center cohorts will elucidate the common clinical characteristics and molecular features of patients whose ventricular dysfunction does not resolve and progresses to HF.

Functional SV defects are complex malformations that contribute disproportionately to the prevalence of HF in part because they may have both pressure and volume overload issues affecting both systemic and pulmonary circulations, and in part because cyanotic lesions are also at risk for subendocardial ischemia. In some SV lesions, such as pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PA/IVS), the left ventricle (LV) is the systemic ventricle while in other lesions, such as HLHS, the right ventricle (RV) is the systemic ventricle. Differences in left and right sided ventricles, as well as ventricular-ventricular interactions, are critical to understand cardiac function and performance. In HLHS, the RV is dilated and hypertrophied and managing three times the normal cardiac output. The morphology of the RV is not built for the demands of systemic circulation. The size of the RV is known to be important in PA/IVS, and the shape has been shown to result in different outcomes in HLHS.8, 52 It is possible that each lesion may be further distinguished by the pattern of specific findings, for example whether the aortic valve is atretic or stenotic in HLHS. Careful phenotyping is important to determine whether specific subphenotypes have unique genetic and molecular causes and characteristics.

Although functional SV defects have high rates of ventricular dysfunction or HF, many lesions are more difficult to gauge. For example, predicting the need for and timing of surgery for valve diseases (stenosis and/or regurgitation) can be challenging. Aortic stenosis may be an emergency in the newborn period but typically is asymptomatic in childhood until progression results in HF. HF is also common, but not universal, in the context of chronic severe pulmonary insufficiency after repair later in life. The manifestation of ventricular dysfunction or HF by lesion is also variable. Left to right shunts include complete AVSDs, which uniformly develop refractory HF within months of birth without surgical correction. In contrast, conotruncal lesions, such as tetralogy of Fallot, may have HF at the time of diagnosis if there is little to no right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, but typically cyanosis dictates the clinical course of these children before repair. Post-surgical scarring or rhythm abnormalities can lead to HF over time. However, in the absence of these injuries, the varying susceptibility of patients to HF, either in the immediate post-surgical period or as long-term sequelae, suggests that additional factors such as genetics may impact the relative risk for HF and ultimately the long term outcome. The ability to predict ventricular dysfunction and/or HF using genetic and molecular information such as predictive biomarkers may inform care and improve outcomes in the future.

Numerous classification schemes for CHD have been developed, the first being Maude Abbott’s atlas.53 Fyler and colleagues subsequently developed a refined system emphasizing anatomy and physiology, and this classification system remains in wide use given its practical application to surgical intervention.54 More recently, the National Birth Defects Program has developed a new scheme that incorporates developmental and etiologic considerations into a system that organizes detailed lesions in groups.55 This type of organization will be necessary to incorporate genetic and molecular information into the phenotype. In addition, the STS has developed a classification system used by their Registry in North America, and the International Nomenclature Committee has recently produced the International Pediatric Cardiac Code for cross-mapping.56 However, none of these systems identifies ventricular dysfunction or HF as an independent phenotype, but emerging evidence showing the genetic basis of these traits suggests it may be prudent to reconsider.

In many ways, our ability to standardize detailed and accurate phenotype data has lagged behind our ability to database genomic findings.57 The field of phenomics results from the need to obtain structured, comprehensive phenotype data, termed deep phenotyping, as well as computational phenomic analysis.58–60 These “big data” analysis methods provide major opportunities for progress. As whole exome and whole genome sequencing become more common both in research and clinical care, a wealth of data are accumulating that can be iteratively interrogated. However, to exploit this resource to begin to understand complex clinical phenotypes such as HF in the CHD population, it needs to be properly combined with accurate, standardized phenotyping and longitudinal patient follow up.55, 56, 60, 61

IV. Distinct Mechanisms

The genome and transcriptome in CHD and HF

As the transcription factors, signaling pathways, and structural proteins that are important for cardiogenesis are delineated, an overlapping network with genes required for both cardiac structure and cardiac function is emerging. As discussed above, there are now clear examples of CHD resulting from mutations in genes that cause cardiomyopathy and HF, providing evidence that abnormal expression of a gene responsible for cardiac contractile function can also cause structural heart defects. Likewise, there are examples of genetic defects causing CHD that can also lead to cardiomyopathy or HF in some proportion of patients. These examples imply that the redundant gene networks responsible for cardiac structure and function can lead to divergent phenotypes when abnormal. As reviewed in Fahed et al., there is increasing evidence that at least some cases of LV dysfunction in CHD result from a genetic predisposition and that combinatorial interactions of genes and environment (e.g., hemodynamic stressors) result in HF in this patient population.62 Studying the genetic background in specific CHD types may further develop this idea and help identify at risk individuals.

Overlapping HF molecular pathways in CHD and cardiomyopathy

There are shared genetic causes between CHD and cardiomyopathy that increase the likelihood of HF in the context of CHD. However, given the frequency with which ventricular dysfunction and HF occurs in individuals with CHD, a shared single genetic cause is unlikely to explain most cases. The development of HF in subsets of patients with specific genetic syndromes hints at overlapping gene networks. What about the more common nonsyndromic CHD? Here, the genetic architecture suggests that a majority of cases result from multifactorial causes and behave as a complex trait although Mendelian inheritance does occur, albeit less frequently. Recent studies in multiplex families with isolated CHD have identified mutations in TBX5, GATA4, TFAP2B, ELN, MYH6 and NOTCH1.63–65 Of note, two of these genes, MYH6 and NOTCH1, are known to overlap with cardiomyopathy. Secondly, TBX5 and TFAP2B cause Holt-Oram syndrome and Char syndrome, respectively, two genetic syndromic conditions that can have very subtle extra-cardiac findings, highlighting the importance of careful phenotyping. De novo mutations are another important cause of isolated CHD. Recent studies indicate that up to 10% of nonsyndromic CHD may be explained by this mechanism.66–68 Interestingly, mutations in histone modifying proteins were commonly observed to occur as de novo mutations, suggesting that abnormal heart patterning resulting from epigenetic alterations may be relatively common.

The distinction between monogenic and complex traits can be overly simplistic, as is drawing a distinct boundary between syndromic and nonsyndromic causes given that variants in genes known to cause syndromic forms of CHD are now identified in nonsyndromic cases. In addition, traits that appear to be monogenic can be influenced by variation in multiple modifier genes, as the above example of cardiac dysfunction in MFS illustrates. The reverse is also true: complex traits can be strongly influenced by variation in a single gene. These findings may explain the decreased penetrance and variable expressivity that are so common in CHD.

In an effort to better understand genetic causes of CHD, systems biology approaches have been used to assess functional convergence of causative CHD genes, effectively combining knowledge from genetics and developmental biology. 69, 70 Developmental pathways acting independently or coordinately contribute to heart development.71, 72 These pathways often exhibit extensive cross-talk, suggesting a highly complex milieu in which individual or multiple genetic variants could potentially act to disrupt normal heart morphogenesis. The integration of genetic analysis with developmental biology knowledge provides an ability to begin to unravel the additive effects of multiple susceptibility alleles in combination. Interestingly, these approaches have suggested that different CHD risk factors are more likely to act on distinct components of a common functional network than to directly converge on a single genetic or molecular target.69, 70

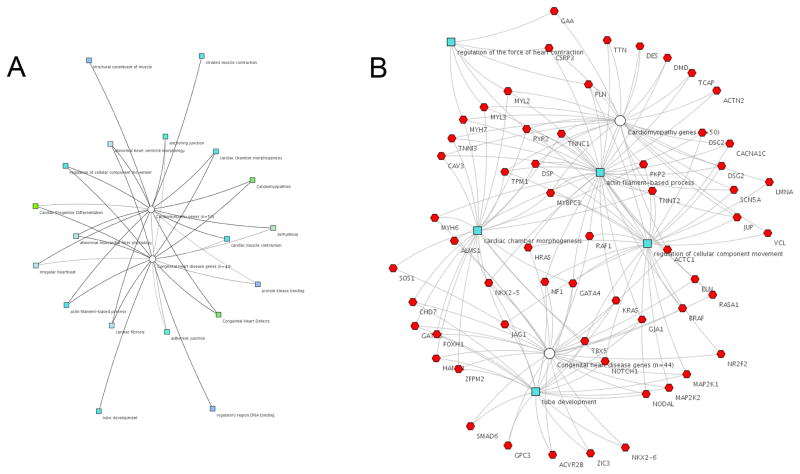

HF is a phenotypic result of multiple heterogeneous etiologies, both environmentally acquired and genetic. Like CHD, systems biology approaches have been applied to HF in an effort to integrate complex interactions.73 However, patients with CHD and HF represent a combination that most studies have not considered. The molecular adapative responses to the mismatch of energetic demands on the heart involve the re-induction of the fetal gene program as well as multiple transcriptional and signaling pathways. Pre-existing genetic abnormalities in these pathways could potentially compromise the adaptive response, thereby leading to HF (Figure 1). To illustrate how pathogenic mutations leading to either cardiomyopathy or CHD might intersect, we performed a basic network analysis using genes available on current clinical genetic testing panels (Figure 2). While there are some categories associated with only CHD or cardiomyopathy, Figure 2A illustrates that a variety of categories are associated with both cardiomyopathy and CHD. For example, the cardiac chamber morphogenesis feature maps to both whereas striated muscle contraction maps only to cardiomyopathy. The line darkness denotes the strength of association, such that arrhythmia is more strongly associated with cardiomyopathy than CHD. Figure 2B shows similar findings at the gene level.

Figure 2. Genes causing congenital heart disease and cardiomyopathy form a complex network.

The network diagrams were generated using ToppCluster (www.toppcluster.cchmc.org) software. Gene lists were derived from clinically available next generation sequencing panels for cardiomyopathy (n=50) and CHD (n=44). A) Abstracted cluster network showing a selected subset of features from the following categories: Gene ontology (GO) GO: molecular function; GO: biological processes; GO: cellular component; human phenotype; mouse phenotype; pathway; disease (cardiomyopathy, CHD). The features are color coded by category and connected to cardiomyopathy (white circle ) and CHD gene nodes. B) Gene level network with nodes (blue) selected from features in GO: biological processes category. The network illustrates that regulation of cellular component of movement, actin filament-based processes, and cardiac chamber morphogenesis are shared in common between cardiomyopathy and CHD genes, whereas regulation of force of heart contraction and tube development are unshared.

In addition to genetic factors contributing to HF, there is substantial interest in the role of epigenetics in CHD and HF. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are noncoding RNAs that consist of 18 to 22 nucleotides. They have been identified as important regulators of gene expression at the post-transcriptional level and act as important modulators of cardiac hypertrophy, HF, and fibrosis.74 miRNAs show promise as circulating biomarkers and their relative stability in the blood as compared to mRNA enhances their suitability for translation to clinical care. Study of miRNAs in mouse models has shown that overexpression can result in cardiac hypertrophy and HF and that deletion can be protective. Profibrotic miRNAs can be blocked by antagomirs resulting in decreased interstitial fibrosis and improved cardiac function in a mouse model of hypertrophy caused by pressure overload. Upregulation of specific miRNAs can also be seen in patients with HF.75 The development of antagomirs for therapeutic use in HF is reportedly in preclinical development.76 Interestingly, pediatric HF patients appear to have unique miRNA profiles,77 suggesting that further investigation that is specific to the pediatric population is required for the application of antagomir based therapy. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are another group of RNA molecules that play important roles in development and disease. lncRNAs are greater than 200 base pair RNAs that function in the regulation of transcriptional and post-transcriptional events. Although less well studied in HF than miRNAs, lncRNAs are emerging as important in this disease process. For example, the mitochondrial lncRNA LIPCAR identified patients undergoing cardiac remodeling who were independently at risk for future cardiovascular deaths.78 CHAST is another lncRNA that has recently been shown to be deregulated in pressure overload induced cardiac hypertrophy in mouse and significantly upregulated in hypertrophic heart tissue from aortic stenosis patients.79 It will be important to determine the degree to which pediatric miRNA and lncRNA profiles change in a developmental-stage specific manner.

In summary, it seems likely that genetic and epigenetic factors may combinatorially affect the susceptibility to both CHD and HF, and some variants will increase or decrease risk for either CHD or HF or both. Identifying these molecular patterns requires systems biology approaches, bioinformatics expertise, and statistical genetic methods. In addition, improved attention to and methodology for accurate phenotyping is essential. The integration of genetic and epigenetic findings with deep phenotyping will improve our understanding of disease etiology, in part by elaborating distinct and shared genetic factors, and ultimately advance medical care.

V. Shared mechanisms

HF is modified by metabolic, molecular and neurohormonal factors

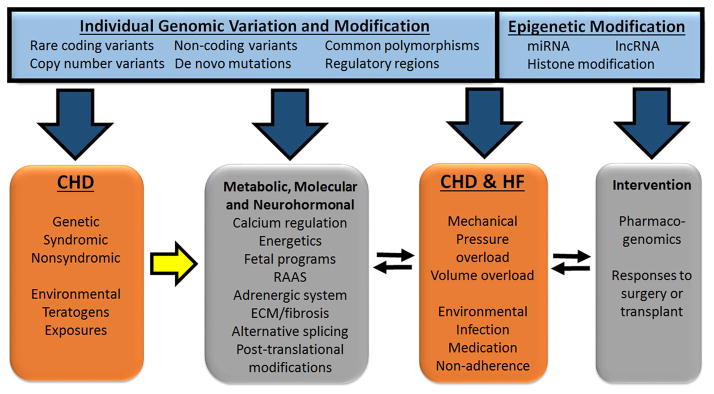

Most of what we know about HF results from studies in adults. These metabolic, molecular, and neurohormonal abnormalities that occur in HF have been the subject of recent reviews, including a previous Compendium issue on HF, and the reader is referred there for in depth information on these complex topics.80 These findings have been applied to the pediatric population. At the molecular level, HF is characterized by transcriptional, translational, and epigenetic alterations that are a consequence of the adaptive and compensatory mechanisms employed by the heart in an attempt to respond to its functional demands (Figure 3). In both adult and pediatric HF, the progressive deterioration of myocardial function leads to an inability of the heart to meet body requirements and is, essentially, a mismatch of supply and demand. Energy starvation is proposed as a unifying mechanism underlying cardiac contractile failure.81, 82 This is frequently the result of a downward spiral of events in which decreases in oxygen and substrate availability trigger adaptive mechanisms including neuroendocrine overdrive, activation of signaling pathways, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, and alterations in mechanical load, among others. While these adaptive mechanisms stabilize contractile function in the short term, over the long term they may result in further compromise due to a vicious cycle characterized in part by an increased mismatch of the supply to demand ratio.83 As metabolic remodeling progresses from adaptation to maladaptation, the failing heart loses the ability to function efficiently.84

Figure 3. Schematic of the interactions between causal, predisposing and contributing factors that result in congenital heart disease and heart failure.

The figure depicts that CHD has a genetic cause and additional genetic components that predispose the heart to maladaptive responses to environmental factors and may, individually or synergistically, lead to a mismatch between cardiac output and demand with subsequent decompensation and ventricular dysfunction (yellow arrow). This in turn triggers epigenetic modifications as well as a number of metabolic, molecular and neurohormonal compensatory responses, which are also under primary genetic regulation and therefore may predispose to disease. The effectiveness of these responses is a critical determinant of the progression to HF. The signs and symptoms of HF are also subject to individual genetic variation; individual genetic and epigenetic variation can provide protective or deleterious effects that influence severity. HF leads to the institution of medical therapies and surgical interventions, including transplantation, which provide an additional layer of individual variation due to differential pharmacogenomics and molecular responses to the stresses of surgery. ECM, extracellular matrix; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

The regulation of cardiac metabolism impacts the course of HF

At the metabolic level, HF represents a state of inefficient energy expenditure. The heart uses fatty acids and glucose as energy sources with the former as the preferred substrate. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key characteristic of HF and is both a cause and a consequence of abnormal energetics.85 A few of the consequences of mitochondrial dysfunction include impaired fatty acid oxidation, increased DNA damage and apoptosis, and alterations in mitochondrial calcium levels. Prenatally, the heart utilizes glucose as its primary energy substrate. Postnatally, there is a transition from a low oxygen intrauterine environment to a high oxygen environment that is accompanied by a switch from anaerobic glycolysis to fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation as a means of ATP production, a metabolically more efficient method of energy generation.86, 87 This transition in substrate utilization is accompanied by mitochondrial proliferation and is a critical transition window. For example, infants with rare inborn errors of metabolism such as fatty acid oxidation disorders or mitochondrial disorders often experience cardiac decompensation during this transition. There are important differences in the expression of nuclear encoded mitochondrial genes during development, suggesting that stage-specific control of mitochondrial biogenesis exists.88 The temporal span over which this occurs in humans has not been well defined. Mouse models have demonstrated that there is a strong activation of mitochondrial biogenesis in the myocardium during the perinatal period. Ablation of transcription factors critical for this metabolic switch, such as TFAM or PGC-1 isoforms, results in upregulation of glycolytic genes and rapidly fatal neonatal heart failure.89, 90 Interestingly, there is now evidence that the transition from a low oxygen to a high oxygen environment after birth leads to mitochondrial damage which results in a block of cell cycle progression and withdrawal from the cell cycle. In contrast, hypoxic cardiomyocytes retain a fetal or neonatal phenotype characterized by smaller size, fewer mitochondria and less evidence of oxidative damage, mononucleation, and, importantly, increased proliferative capacity.91, 92 These studies have implications for approaches to cardiac regeneration and management of energetic demands during HF.

Sarcomeric architecture can revert to fetal state through molecular switching

Sarcomere isoform switching and re-induction of the fetal gene program occurs in HF.93–97 More recent evidence indicates that these switches apply to miRNAs as well.74, 98 The contractile apparatus is responsive to ions, particularly calcium, and the autonomic nervous system. The excitation-contraction coupling that occurs as a result of calcium influx to the myocyte and subsequent calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum is fundamentally abnormal in HF, typically resulting in decreased contractile force as well as delayed or incomplete relaxation. While pediatric HF recapitulates many of these changes, the sarcomere of a fetus and neonate is not identical to that of an adult.99 The sarcomeric proteins myosin, actin, troponin, tropomyosin and titin show isoform switching during development as a result of distinct gene expression or alternative splicing.100 During HF, isoform transitions occur, often with re-induction of the fetal gene program. In addition, calcium transients are different in neonates, with increased utilization of trans-sarcolemmal calcium flux. Taken together with the differences in contractility due to sarcomere isoform differences, the neonatal heart is stiffer, with less contractile reserve than the adult heart.101

The matrix has a structural and functional impact

In addition to the components of the sarcomere, the extracellular matrix (ECM) plays an important structural and signaling role during HF progression. Increasing ECM deposition results in interstitial and perivascular fibrosis. Elevated levels of serum markers of collagen turnover may be useful for risk stratification of those at high risk of death and HF hospitalization in adults.102 In addition, studies on ECM deposition and difference in microfibril content of neonatal cardiomyocytes suggest that the likelihood of fibrosis differs depending on the age of the cardiomyocyte. The ultrastructure of fetal cardiomyoctyes is distinct from adult cardiomyoctyes, containing fewer microfibrils and mitochondria. Furthermore, the numbers of cardiomyocytes differ by age, with cardiomyocyte numbers increasing immediately after birth but subsequently permanently withdraw from the cell cycle leaving the heart with limited regenerative capacity.103, 104 Clearly, an understanding of the developmental differences in cardiomyocyte response to injury has important therapeutic implications, but these studies also show that treatment of infants with HF may require substantially different approaches than adult HF patients. Since the human heart continues to grow in size in a developing organism, it is logical to infer that additional differences and ongoing changes impact HF in older children.

New findings in regulation of the adrenergic signaling cascade in infants and children

There is a vast literature describing adrenergic signaling during HF, the deleterious effects of chronic stimulation and increased sympathetic drive, the distinct functions of α1, α2, and β receptors, and the importance of the adrenergic system as a therapeutic target.80, 105 In pediatric patients with HF, therapy is directed at mitigating this increased sympathetic drive, analogous to treatment in the adult population. However, clinical and translational research studies are beginning to identify important differences in the pediatric HF patient. Animal models have previously shown that β-adrenergic receptor-adenylyl cyclase cAMP pathway-mediated contractility responsiveness is less robust in the fetal/newborn heart versus the adult heart. Furthermore, phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibition has less effect on contractility alone, but enhanced contractility when combined with isoproterenol.101 Several recent studies investigate the molecular findings in explanted hearts from children with HF and demonstrate age-related differences similar to those seen in mouse. Pediatric patients with DCMshowed a differential adaptation of the β-adrenergic signaling pathway when compared to adults with DCM or non-failing controls.106 Specifically, down-regulation of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors is identified in children, whereas β2-AR expression is maintained in adults. Differences in the phosphorylation status of phospholamban are also noted in children versus adults.106 Investigation of PDE isoform expression and responsiveness to PDE inhibition also differed in pediatric versus adult samples.107, 108 While the approach to medical therapy is similar, there are a lack of data on the adaptive responses triggered in patients with structurally abnormal hearts as compared to those with primary heart muscle disease. In the investigation of PDE expression, intriguing differences were noted in samples from DCM explants as compared to single right ventricle CHD hearts in the myocardial response to milrinone.108, 109 Additional studies are required to understand the characteristic adaptive programs invoked by ventricular dysfunction of different etiologies. These findings suggest a differential responsiveness to HF medical therapy depending on age, a conclusion that requires more investigation.

VI. Clinical research for pediatric ventricular dysfunction and HF is limited

HF has been extensively studied in adults but has only recently begun to be evaluated in the pediatric population. To assess the current clinical research in this area, we queried the clinical trials website (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and determined that 1.3% of HF studies currently open for enrollment include children with CHD (n = 29). Fundamental questions about whether HF represents the same disease in children remain to be answered, but small numbers and heterogeneity are problematic. Below, we give examples of clinical trials within the SV population, which has been studied rigorously in recent years. One limitation to current studies is the difficulty with comparing results between different trials. For example, the PCGC has not reported the presence of ventricular dysfunction or HF as a distinct or modifying phenotype, and the NPC-QIC has analyzed only cases that are at least moderately abnormal.68, 110 A clear overarching need is to leverage existing cohorts by combining them to facilitate trials where both primary and secondary questions can be answered. Adopting a learning health system, such as the NPC-QIC, may improve the results of trials performed using existing cohorts since this approach has shown significant increases in patient participation, a common limitation in pediatric heart disease trials.111, 112 Clinical trials using learning health systems may improve outcomes through quality improvement efforts and accelerate findings and subsequent dissemination. Partnerships with non-profit organizations facilitate this type of research in part by assuming some of the cost, but more importantly by mobilizing patients and organizing patients’ collective experience to identify and advance clinically relevant patient oriented research questions.113

In patients with CHD, complex defects have a higher rate of associated HF. Functional SV heart defects account for a disproportionate share of the morbidity and mortality in CHD, and mortality in the first year of life ranges from 10–35%.114, 115 In addition, management of these patients is associated with a significant economic burden and high levels of resource requirements. Clinical research, including studies performed by the PHN, has reported detailed clinical outcomes in this population of patients.

The clinical predictors of poor outcome in functional SV defects are based on the type of CHD and complications developed during staged palliative repairs. Although the surgical approach is similar amongst SV lesions, the underlying genetic causes are different, and well-characterized genetic syndromic conditions predict worse outcome. The PHN SV Reconstruction Trial has provided information on outcomes in this patient population.6, 116–123 In the initial comparison of Blalock-Taussig versus right ventricle-pulmonary artery shunt types for SV, transplant free survival at 12 months was 74 and 64% respectively with no significant differences seen at 3 years.6, 119 Mortality with stage I palliation (Norwood) ranges from 7–19% and between stage I and stage II palliation, 4–15%. Interestingly, genetic abnormalities were identified as independent risk factors, suggesting some degree of the variation observed in HF occurrence in severity is attributable to genetic factors.122 SV patients with Fontan circulation, in which the venous return bypasses the SV and is directed to the pulmonary artery, face a number of medical issues including growth problems, hemodynamic compromise including cyanosis, pathway obstructions and valve dysfunction, arrhythmias, or pleural effusions, and ascites.124 Fontan circulation results in progressive multiorgan system dysfunction, and Fontan failure requires cardiac transplantation. Studies to determine survival of different types of SV malformations, such as HLHS versus tricuspid atresia are ongoing. In this complex context, it is difficult to isolate the cause and impact of ventricular dysfunction and HF, but the potential utility of this knowledge is substantial. For example, the ability to stratify patients into high risk or low risk of myocardial dysfunction could lead to more tailored approaches and protocols to monitor patients and medically intervene.

The anatomical and morphological features of the ventricle are also important determinants of outcome. The RV does not adapt well to the demands of the systemic ventricle. Previous work has shown that at least 50% of patients with CHDs where the RV is the systemic ventricle, such as l-TGA (congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries) and HLHS, develop RV dysfunction. In addition, there is a 15% incidence of death or heart transplantation in early adulthood due to myocardial dysfunction.125, 126 Transcriptional profiling has shown that the inability of the RV to respond to chronic pressure overload is correlated with its inability to assume a “LV” expression pattern of genes such as angiotensin, adrenergic receptors, G-proteins, cytoskeletal and contractile components.127–129 Just as variation in sarcomeric genes might explain a proportion of HF, or predisposition to HF in CHD cases, it is possible that genetic variation in these pathways predispose some individuals to myocardial dysfunction when superimposed on the background of CHD (Figure 1). Thus, variation that might be silent in the “normal” population may strongly predispose to (or protect from) poor outcome in the CHD population. This level of genetic variation has not yet been explored. While expression analyses have not been performed in SV patients, it is tempting to speculate that the maladaptive responses that the RV exhibits under pressure overload would be similar under chronic volume overload. Thus, patients with LV SVs traditionally have had better survival than those with RV SVs. Better understanding the developmental and genetic basis of these differences and the progression to HF should not only provide insight into the relative contribution of pressure and volume overload, but also provide new important data for novel therapeutics.

Clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate stem cell therapy as a treatment for SV defects such as HLHS. In 2015, intracoronary injection of umbilical cord blood derived mononuclear cells or intracoronary administration of autologous cardiosphere-derived cells (CDC) were successfully used in HLHS patients. In the case of CDC infusion, right ventricular ejection fraction remained persistently improved during 36-month follow-up.130, 131 Additional clinical trials are in progress using sources of progenitor cell types that have had reliable and safe results in earlier studies, including allogenic mesenchymal stem cells, bone marrow derived cells, c-kit+ cells or umbilical cord cells. 132 While there is optimism that stem cell therapy represents a novel direction that could provide significant gains to management in the pediatric population, there is much still to be learned about the cell-type specific requirements, the timing of administration, the long term impact on cardiac status, and the mechanisms of action.132–135 Induced pluripotent stem cells are another mechanism for studying and modeling patient specific disease processes.

Medical therapy and pharmacogenomics

Medical therapy for HF in patients with CHD is typically extrapolated from adults with ischemic HF. There are limited data to support use in children. For example, a recent trial of valsartan, an angiotensin II receptor blocker, in patients with a systemic RV failed to show any beneficial effect on the primary end point of RV ejection fraction.136 Similarly, a randomized trial of enalapril in infants with SV did not alter HF severity or improve growth or ventricular function.117 Taken together, these observations suggest that pediatric HF may have different causes and/or additional contributing factors, and therefore will require new and different therapies.

Pharmacogenomics is defined as the association between genetic factors and drug response. Inter-individual variation in drug response can lead to therapeutic failure (e.g., ultrarapid metabolizers) as well as adverse drug responses (poor metabolizers). While numerous pharmacogenomic clinical trials have occurred in the adult HF population, very few studies have been performed in the CHD population.137 Specific challenges to the study of pharmacogenomics in the CHD population include variability in underlying etiology (genetic variability), heterogeneity in the types of CHDs and their treatment (phenotypic variability), small sample sizes, frequent dosing changes with age and changes in drug responsiveness with age. Furthermore, there is significant variability in the treatment and management of these patients at different centers, leading to challenges for multisite studies.

To date, the only study to address HF or ventricular remodeling in CHD was performed by Mital et al., with a combinatorial approach to investigate the impact of five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes within the renin-angiontensin-aldosterone (RAAS) pathways as part of the PHN SV Reconstruction Trial. The results demonstrated an association with RAAS genotype and failure of reverse remodeling after surgery.7 The limitations of this important study were that it consisted of a relatively small population and was biased toward patients surviving past stage I palliation. In 2014, the same RAAS SNP was shown to be independently associated with increased tachyarrhythmia after CHD surgery (Odds ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.1–2.3, P=.02)).138 Thus there is preliminary evidence for the potential utility of pharmacogenetics in the CHD population, but larger studies with increased numbers are required. Ultimately, individual risk stratification and personalized care are dependent on our ability to 1) define primary causes of CHD; 2) identify secondary genetic factors that lead to susceptibility to or protection from myocardial dysfunction in the context of CHD and environmental/mechanical stressors; and 3) select appropriate medical therapy based on predicted pharmacogenomic response. It is the combinatorial interaction of these primary, secondary, and tertiary genetic influences which ultimately determines the clinical phenotype and outcome in a multifactorial fashion.

Summary

Pediatric HF is a clinical entity that results from an inability of the heart to meet working demands. Although sharing many metabolic and molecular features with adults with HF, as shown in Figure 3, children have underlying causes, presentations and disease courses that may differ from adults. Thus, a fundamental question is whether HF in the pediatric population is the same disease process as it is in adults. What is the evidence for standard HF therapy in pediatric CHD patients? Do standard HF prognostic tools work in these patients? How do differences in the myocardium in infancy and early childhood affect management and therapeutics? Additional research is needed to organize existing data and leverage established cohorts to answer these questions. For example, analyzing outcomes within subgroups of large cohorts with CHD is necessary to understand the common clinical characteristics and molecular features of patients whose ventricular dysfunction does not resolve or progresses to HF. There is preliminary evidence that the myocardium has distinct molecular properties based on age and location (RV versus LV). Furthermore, responsiveness of the myocardium to medication varies based on age. Additional investigation of these differences is necessary in order to risk stratify and customize therapy. Stem cell therapy holds great promise as a novel approach to HF in CHD, but basic, translational, and clinical research are necessary to understand how to apply it. Future research investigating the shared developmental mechanisms leading to both CHD and cardiomyopathy will likely be informative for understanding genetic and epigenetic pathways that increase susceptibility to HF.

Numerous research approaches have been used to investigate HF (Table 4) and the research community is well positioned to leverage these resources. Basic research in HF is substantial, and although not a focus of this review, there is a clear need for additional animal models of HF in CHD. Genetic and genomic approaches are progressing rapidly, but we need standardized biorepositories that combine harmonized data collection to realize improved treatment strategies. Secondary studies from large multi-center trials are needed to further characterize disease in those cohorts. Increasing the emphasis on integration of the different components of HF may accelerate the identification of new therapeutic windows (Figure 3). Ultimately, multifaceted and combined research approaches will advance medical care by allowing risk stratification by age, lesion, and/or underlying etiology and will lead to improved protocols for medical intervention and therapy.

Table 4.

Research approaches to investigate CHD and HF

| Approach | Benefits/Questions answered | Limitations | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic | In vivo | Modeling anatomy and physiology; functional testing; genetic manipulation (some model organisms) | Cost and time; may not predict human biology | Large animal – surgical models and bioprosthetics139 Small animal – mouse models of disease44 |

| In vitro | Faster and less expensive functional testing than in vivo; | Non-physiologic; no 3D heart structure | Cell signaling47, expression studies, siRNA, tissue engineering | |

| Translational | Genetic/genomic | Disease causation; individual variation | Costly; sample size requirements | GWAS, CMA, WES,66 WGS, Pharmacogenomics |

| Epigenetic | Gene regulation; disease specific alterations | Heterogeneous cell types; throughput and efficiency | miRNA140, 141, lncRNA79, piRNA, chromatin remodeling | |

| “omics” | Large datasets; Comprehensive; hypothesis generating |

Large datasets; descriptive |

Transcriptome (microarray, RNAseq), regulome (ChIPseq), microbiome/metabolome, proteome72, 142 | |

| Companion diagnostics | Personalized medicine; risk stratification | Association and validation difficult | WES/Biomarker pairs143 | |

| Stem cell | Personalized/patient specific | Labor intensive; reprogramming artifacts | iPS cell, cardiac progenitor cell 134,144 mesenchymal derived | |

| Systems biology | Unbiased comprehensive analyses | Dependent on accurate annotation and curation in databases | Bioinformatics70 | |

| Clinical | Epidemiology/population health | Disease incidence and determinants; evidence based practice and analysis; | Not mechanistic; may not determine causality | Registry61, 145 |

| Clinical trial | Direct comparisons in patients | Costly; multiple regulatory layers; study size requirements difficult in pediatrics | Drug trial,117, 136, 146 surgical outcome122 |

ChIPseq chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing, CMA chromosome microarray analysis, GWAS genome wide association study, iPS cell induced pluripotent stem cell, lncRNA long non-coding RNA, miRNA microRNA, piRNA Piwi-interacting RNA, RNASeq RNA sequencing, siRNA small interfering RNA, WES whole exome sequencing, WGS whole genome sequencing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

This work is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award, the March of Dimes, and the Indiana University Health—Indiana University School of Medicine Strategic Research Initiative and Physician Scientist Initiative (SMW).

Abbreviations

- ACHD

adult congenital heart disease

- AVSD

atrioventricular septal defect

- CDC

cardiosphere-derived cells

- CHD

congenital heart disease

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- HCM

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- HF

heart failure

- HLHS

hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- LV

left ventricle

- LVNC

left ventricular noncompaction

- MFS

Marfan syndrome

- NSML

Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigenes

- PA/IVS

pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- RV

right ventricle

- SV

single ventricle

- VSD

ventricular septal defect

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Kirk R, Dipchand AI, Rosenthal DN, Addonizio L, Burch M, Chrisant M, Dubin A, Everitt M, Gajarski R, Mertens L, Miyamoto S, Morales D, Pahl E, Shaddy R, Towbin J, Weintraub R. The international society for heart and lung transplantation guidelines for the management of pediatric heart failure: Executive summary [corrected] J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:888–909. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW American College of Cardiology F, American Heart A. 2009 focused update incorporated into the acc/aha 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults a report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines developed in collaboration with the international society for heart and lung transplantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53:e1–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res. 2013;113:646–659. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross RD, Daniels SR, Schwartz DC, Hannon DW, Shukla R, Kaplan S. Plasma norepinephrine levels in infants and children with congestive heart failure. The American journal of cardiology. 1987;59:911–914. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)91118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connolly D, Rutkowski M, Auslender M, Artman M. The new york university pediatric heart failure index: A new method of quantifying chronic heart failure severity in children. J Pediatr. 2001;138:644–648. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.114020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohye RG, Sleeper LA, Mahony L, Newburger JW, Pearson GD, Lu M, Goldberg CS, Tabbutt S, Frommelt PC, Ghanayem NS, Laussen PC, Rhodes JF, Lewis AB, Mital S, Ravishankar C, Williams IA, Dunbar-Masterson C, Atz AM, Colan S, Minich LL, Pizarro C, Kanter KR, Jaggers J, Jacobs JP, Krawczeski CD, Pike N, McCrindle BW, Virzi L, Gaynor JW Pediatric Heart Network I. Comparison of shunt types in the norwood procedure for single-ventricle lesions. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1980–1992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mital S, Chung WK, Colan SD, Sleeper LA, Manlhiot C, Arrington CB, Cnota JF, Graham EM, Mitchell ME, Goldmuntz E, Li JS, Levine JC, Lee TM, Margossian R, Hsu DT Pediatric Heart Network I. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone genotype influences ventricular remodeling in infants with single ventricle. Circulation. 2011;123:2353–2362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.004341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giglia TM, Jenkins KJ, Matitiau A, Mandell VS, Sanders SP, Mayer JE, Jr, Lock JE. Influence of right heart size on outcome in pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum. Circulation. 1993;88:2248–2256. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster G, Zhang J, Rosenthal D. Comparison of the epidemiology and co-morbidities of heart failure in the pediatric and adult populations: A retrospective, cross-sectional study. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2006;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossano JW, Shaddy RE. Heart failure in children: Etiology and treatment. J Pediatr. 2014;165:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossano JW, Kim JJ, Decker JA, Price JF, Zafar F, Graves DE, Morales DL, Heinle JS, Bozkurt B, Towbin JA, Denfield SW, Dreyer WJ, Jefferies JL. Prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of heart failure-related hospitalizations in children in the united states: A population-based study. Journal of cardiac failure. 2012;18:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipshultz SE, Sleeper LA, Towbin JA, Lowe AM, Orav EJ, Cox GF, Lurie PR, McCoy KL, McDonald MA, Messere JE, Colan SD. The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the united states. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:1647–1655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39:1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massin MM, Astadicko I, Dessy H. Epidemiology of heart failure in a tertiary pediatric center. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:388–391. doi: 10.1002/clc.20262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sommers C, Nagel BH, Neudorf U, Schmaltz AA. congestive heart failure in childhood. An epidemiologic study. Herz. 2005;30:652–662. doi: 10.1007/s00059-005-2596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norozi K, Wessel A, Alpers V, Arnhold JO, Geyer S, Zoege M, Buchhorn R. Incidence and risk distribution of heart failure in adolescents and adults with congenital heart disease after cardiac surgery. The American journal of cardiology. 2006;97:1238–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurvitz M, Burns KM, Brindis R, Broberg CS, Daniels CJ, Fuller SM, Honein MA, Khairy P, Kuehl KS, Landzberg MJ, Mahle WT, Mann DL, Marelli A, Newburger JW, Pearson GD, Starling RC, Tringali GR, Valente AM, Wu JC, Califf RM. Emerging research directions in adult congenital heart disease: A report from an nhlbi/acha working group. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;67:1956–1964. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lui GK, Fernandes S, McElhinney DB. Management of cardiovascular risk factors in adults with congenital heart disease. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3:e001076. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parrott A, Ware SM. The role of the geneticist and genetic counselor in an achd clinic. Progress in pediatric cardiology. 2012;34:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webb G, Mulder BJ, Aboulhosn J, Daniels CJ, Elizari MA, Hong G, Horlick E, Landzberg MJ, Marelli AJ, O’Donnell CP, Oechslin EN, Pearson DD, Pieper EP, Saxena A, Schwerzmann M, Stout KK, Warnes CA, Khairy P. The care of adults with congenital heart disease across the globe: Current assessment and future perspective: A position statement from the international society for adult congenital heart disease (isachd) International journal of cardiology. 2015;195:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wessels MW, Willems PJ. Mutations in sarcomeric protein genes not only lead to cardiomyopathy but also to congenital cardiovascular malformations. Clinical genetics. 2008;74:16–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postma AV, van Engelen K, van de Meerakker J, Rahman T, Probst S, Baars MJ, Bauer U, Pickardt T, Sperling SR, Berger F, Moorman AF, Mulder BJ, Thierfelder L, Keavney B, Goodship J, Klaassen S. Mutations in the sarcomere gene myh7 in ebstein anomaly. Circulation. Cardiovascular genetics. 2011;4:43–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.957985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbustini E, Favalli V, Narula N, Serio A, Grasso M. Left ventricular noncompaction: A distinct genetic cardiomyopathy? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;68:949–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorca R, Martin M, Reguero JJ, Diaz-Molina B, Moris C, Lambert JL, Astudillo A. Left ventricle non-compaction: The still misdiagnosed cardiomyopathy. International journal of cardiology. 2016;223:420–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stahli BE, Gebhard C, Biaggi P, Klaassen S, Valsangiacomo Buechel E, Attenhofer Jost CH, Jenni R, Tanner FC, Greutmann M. Left ventricular non-compaction: Prevalence in congenital heart disease. International journal of cardiology. 2013;167:2477–2481. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.05.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luxan G, Casanova JC, Martinez-Poveda B, Prados B, D’Amato G, MacGrogan D, Gonzalez-Rajal A, Dobarro D, Torroja C, Martinez F, Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Fernandez-Friera L, Sabater-Molina M, Kong YY, Pizarro G, Ibanez B, Medrano C, Garcia-Pavia P, Gimeno JR, Monserrat L, Jimenez-Borreguero LJ, de la Pompa JL. Mutations in the notch pathway regulator mib1 cause left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Nature medicine. 2013;19:193–201. doi: 10.1038/nm.3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Chen H, Qu X, Chang CP, Shou W. Molecular mechanism of ventricular trabeculation/compaction and the pathogenesis of the left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy (lvnc) American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2013;163C:144–156. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Zhang W, Sun X, Yoshimoto M, Chen Z, Zhu W, Liu J, Shen Y, Yong W, Li D, Zhang J, Lin Y, Li B, VanDusen NJ, Snider P, Schwartz RJ, Conway SJ, Field LJ, Yoder MC, Firulli AB, Carlesso N, Towbin JA, Shou W. Fkbp1a controls ventricular myocardium trabeculation and compaction by regulating endocardial notch1 activity. Development. 2013;140:1946–1957. doi: 10.1242/dev.089920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ching YH, Ghosh TK, Cross SJ, Packham EA, Honeyman L, Loughna S, Robinson TE, Dearlove AM, Ribas G, Bonser AJ, Thomas NR, Scotter AJ, Caves LS, Tyrrell GP, Newbury-Ecob RA, Munnich A, Bonnet D, Brook JD. Mutation in myosin heavy chain 6 causes atrial septal defect. Nature genetics. 2005;37:423–428. doi: 10.1038/ng1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsson H, Eason J, Bookwalter CS, Klar J, Gustavsson P, Sunnegardh J, Enell H, Jonzon A, Vikkula M, Gutierrez I, Granados-Riveron J, Pope M, Bu’Lock F, Cox J, Robinson TE, Song F, Brook DJ, Marston S, Trybus KM, Dahl N. Alpha-cardiac actin mutations produce atrial septal defects. Human molecular genetics. 2008;17:256–265. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monserrat L, Hermida-Prieto M, Fernandez X, Rodriguez I, Dumont C, Cazon L, Cuesta MG, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Peteiro J, Alvarez N, Penas-Lado M, Castro-Beiras A. Mutation in the alpha-cardiac actin gene associated with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular non-compaction, and septal defects. European heart journal. 2007;28:1953–1961. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preuss C, Andelfinger G. Genetics of heart failure in congenital heart disease. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2013;29:803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azhar M, Ware SM. Genetic and developmental basis of cardiovascular malformations. Clinics in perinatology. 2016;43:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalani SR, Belmont JW. Genetic basis of congenital cardiovascular malformations. European journal of medical genetics. 2014;57:402–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowan JR, Ware SM. Genetics and genetic testing in congenital heart disease. Clinics in perinatology. 2015;42:373–393. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lander J, Ware SM. Copy number variation in congenital heart defects. Current Genetic Medicine Reports. 2014;2:168–178. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vissers LE, van Ravenswaaij CM, Admiraal R, Hurst JA, de Vries BB, Janssen IM, van der Vliet WA, Huys EH, de Jong PJ, Hamel BC, Schoenmakers EF, Brunner HG, Veltman JA, van Kessel AG. Mutations in a new member of the chromodomain gene family cause charge syndrome. Nature genetics. 2004;36:955–957. doi: 10.1038/ng1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]