Abstract

Organ transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with end‐stage organ failure, but chronic immunosuppression is taking its toll in terms of morbidity and poor efficacy in preventing late graft loss. Therefore, a drug‐free state would be desirable where the recipient permanently accepts a donor organ while remaining otherwise fully immunologically competent. Mouse studies unveiled mixed chimerism as an effective approach to induce such donor‐specific tolerance deliberately and laid the foundation for a series of clinical pilot trials. Nevertheless, its widespread clinical implementation is currently prevented by cytotoxic conditioning and limited efficacy. Therefore, the use of mouse studies remains an indispensable tool for the development of novel concepts with potential for translation and for the delineation of underlying tolerance mechanisms. Recent innovations developed in mice include the use of pro‐apoptotic drugs or regulatory T cell (Treg) transfer for promoting bone marrow engraftment in the absence of myelosuppression and new insight gained in the role of innate immunity and the interplay between deletion and regulation in maintaining tolerance in chimeras. Here, we review these and other recent advances in murine studies inducing transplantation tolerance through mixed chimerism and discuss both the advances and roadblocks of this approach.

Keywords: rodent, tolerance/suppression/anergy, transplantation

OTHER ARTICLES PUBLISHED IN THIS REVIEW SERIES

Immune tolerance in transplantation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2017, 189: 133–4.

Transplantation tolerance: the big picture. Where do we stand, where should we go? Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2017, 189: 135–7.

Operational tolerance in kidney transplantation and associated biomarkers. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2017, 189: 138–57.

Immune monitoring as prerequisite for transplantation tolerance trials. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2017, 189: 158–70.

Transplantation tolerance: don't forget about the B cells. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2017, 189: 171–80.

Chimerism‐based tolerance in organ transplantation: preclinical and clinical studies. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2017, 189: 190–6.

Regulatory T cells: tolerance induction in solid organ transplantation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2017, 189: 197–210.

Still in search of the Holy Grail

Transplantation is still the most effective treatment option for patients with end‐stage organ failure 1, but exposes the recipients to a life‐long dependency on immunosuppressive drugs. The necessity of permanent medication puts transplant recipients at risk of a wide range of possible complications 2. Immunosuppression increases the susceptibility to infections and cancers, while under‐immunosuppression may provoke episodes of rejection. In a substantial fraction of transplant recipients late graft loss cannot be prevented by current means, which further increases the demand for donor organs, which are a scarce and limited resource 3. Therefore, transplant immunologists still crave for a state where the recipient immune system accepts donor antigens specifically and permanently while remaining otherwise fully immunologically competent. Numerous strategies have been elaborated in rodent models to achieve this desired state, from which mixed chimerism (i.e. co‐existence of donor and recipient haematopoietic stem cells after a donor haematopoietic stem cell transplantation) emerged as a promising approach 4.

Rodent models have served historically as a useful tool to investigate the basic principles of allorecognition and graft rejection. The availability of defined mouse strains enabled the identification of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and its role for transplant rejection 5. The landmark experiments by Peter Medawar in 1953 finally paved the way for mouse models as the most favourable instrument in search for the ‘Holy Grail’ of tolerance induction. Medawar could show that tolerance towards alloantigens can be induced deliberately by inoculating prenatal mice with a mixture of allogeneic cells 6. Those recipients accepted donor skin for an extended period of time while promptly rejecting skin from third parties. This finding constitutes a milestone in the history of transplantation tolerance, despite being clinically inapplicable. The first step towards practical feasibility came in 1955, when Joan M. Main and Richmond I. Prehn achieved donor‐specific tolerance by transplanting allogeneic bone marrow successfully into lethally irradiated mice 7. Initial euphoria was soon dampened by the finding that, depending on the strain combinations, most of the mice developed lethal graft‐versus‐host disease (GVHD) 8. Removing donor T cells from the bone marrow inoculum could avert GVHD, although at the expense of reduced engraftment rates 9. On the contrary, supplementing the graft with donor T cells promoted bone marrow engraftment by counteracting host immunity 10. Alternatively, high doses of fractionated total lymphoid irradiation were able to induce chimerism without any clinical evidence of GVHD 11, especially when combined with T cell‐depleting agents 12. Nevertheless, several chimeras still succumbed to radiation‐independent toxicities. Full chimeras also featured specific defects in controlling viral infections 13 ascribed to the discrepancy between positive selection of donor T cells by host thymic epithelial cells and antigen presentation by peripheral donor antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) 14. To overcome this obstacle, Ildstad and Sachs inoculated a mixture of T cell‐depleted host and donor bone marrow into lethally irradiated mice. Mixed lymphohaematopoietic chimerism developed in all lineages without signs of GVHD and skin allografts were specifically accepted long‐term 15. This observation established mixed chimerism as potent approach for the induction of transplantation tolerance.

Targeting T cells to induce mixed chimerism

Because irradiation entails severe side effects, strategies were sought to minimize the required dose for bone marrow engraftment. To achieve this goal, it was necessary to control more specifically the mechanisms responsible for allogeneic bone marrow rejection. After T cells were identified as the major contributors of MHC mismatched bone marrow rejection 16, efforts were made to target them with a higher precision. Elimination of host T cells with depleting antibodies allowed reducing the dose of total body irradiation (TBI) to 6 Gy 17. As T cell‐depleting antibodies primarily target peripheral T cells, local irradiation of the thymus was employed to enable a further reduction of the necessary TBI to a non‐myeloablative dose of 3 Gy 18. Increasing the number of bone marrow cells (‘megadose’ bone marrow transplantation) could eliminate the need for TBI, but not the need for thymic irradiation 19, 20. However, profound T cell depletion is also risky, as it renders the recipient vulnerable to severe infections until T cell repopulation is sufficient again after several weeks. This is a matter of concern, as most patients undergoing transplantation are of adult age and therefore exhibit a reduced thymic function leading to prolonged periods of immunoincompetence 21. Consequently, T cell‐specific antibodies were modified to prevent their activation without depleting them. Blocking the co‐receptors CD4 and CD8 was sufficient to induce chimerism and skin graft tolerance over minor antigen barriers, but failed to do so in the setting of MHC disparities 22. The use of co‐receptor blocking antibodies has recently regained importance for the treatment of autoimmune disorders. Inducing mixed chimerism through concomitant blockade of CD3 and CD8 has been used recently to reverse autoimmunity in non‐obese diabetic (NOD) mice 23. However, the emergence of co‐stimulation blockers (targeting the CD28 and CD40 pathways) brought significant progress, as they provided an effective strategy to induce mixed chimerism without the need for T cell depletion in recipients conditioned with 3Gy TBI 24, and even obviated the need for any irradiation when high enough marrow doses were administered 25, 26.

Co‐stimulation blockade and then…?

Co‐stimulation blockade per se is not sufficient to allow engraftment of conventional (i.e. clinically realistic) donor bone marrow doses in the absence of irradiation. As tolerance‐inducing protocols should ideally be non‐cytotoxic for the sake of patient safety, further strategies are needed to control co‐stimulation blockade‐resistant mechanisms of rejection. The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor was effective in allowing a further reduction in the required TBI dose when given together with co‐stimulation blockade 27. Intriguingly, calcineurin inhibitors, in contrast, impaired tolerance induction under these circumstances by blocking peripheral deletion of alloreactive T cells 27. Interrupting inducible T cell co‐stimulator (ICOS) and CD134 (OX40) signalling has also been shown to synergize with CD28 and CD40L blockade in preventing T cell activation and prolonging allograft survival 28, 29. In line with this, engraftment of ICOS–/– bone marrow was significantly higher compared to wild‐type grafts (WT) 30, while the effect of OX40L blockade was only marginal 31, 32. Combining CD40L blockade with the pro‐apoptotic small molecule ABT‐737, a Bcl‐2 inhibitor, induced stable mixed chimerism and long‐term allograft survival without the need for further cytoreductive conditioning. Under these circumstances calcineurin inhibitors were required to prevent the resistance of activated T cells to ABT‐737 by reducing the expression of the anti‐apoptotic factor Bcl‐2A1 33, 34. Several Bcl‐2 family inhibitors, including the ABT‐737 derivative navitoclax, are under clinical development as anti‐cancer drugs and could be valuable components of chimerism‐based tolerance regimens.

Cell therapies coming of age

Cell therapies have come into focus in recent years, as they provide several appealing advantages over small‐molecule or biological pharmaceuticals 35. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) eminently aroused the interest of the whole transplant field due to their critical role in maintaining self‐tolerance. Despite significant progress in this field, there is still an ongoing debate about the preferable origin of the cells (donor versus recipient) and the optimal preparation (isolation, activation, expansion) of the product 36, 37. While it remains unclear whether Treg transfer by itself will be sufficient to induce transplant tolerance, it has emerged as an exceptionally potent strategy to promote bone marrow engraftment. Transfer of polyclonal, in‐vitro‐activated Tregs from the recipient led to engraftment of conventional doses of allogeneic bone marrow without the need for any cytoreductive conditioning when given together with a short course of co‐stimulation blockade [α‐CD40L + cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4‐immunoglobulin (CTLA4‐Ig)] and rapamycin. Durable tolerance towards fully mismatched skin and heart allografts was achieved in more than 90% of the recipients 38, 39. Notably, recipient Tregs were superior to donor or third‐party Tregs in this model 40. An adapted form of this protocol has been translated successfully to non‐human primates 41. Recently, retinoic‐acid induced alloantigen‐specific Tregs from the recipient were reported to induce chimerism and tolerance in a non‐myeloablative bone marrow transplantation (BMT) model using CTLA4‐Ig and rapamycin. Considerable levels of chimerism were achieved which gradually declined over time, and long‐term tolerance was obtained in approximately 35% of the recipients 42.

Regulatory cell therapies are being tested currently in a considerable number of clinical trials, but their application as a clinical routine is still elusive. Therefore, it would be desirable to replace cell therapies by pharmaceutical agents that expand Tregs selectively in vivo or mimic their effector function. Interleukin (IL)‐2 complexes increased Treg numbers efficiently in vivo 43, 44, but were not able to replace Treg therapy in a co‐stimulation blockade‐based BMT model. Rather, IL‐2 complexes enhanced bone marrow rejection by stimulating CD8 and natural killer (NK) cells expressing the low‐affinity IL‐2 receptor 44. In another study, a non‐lytic IL‐2 fusion protein (Fc silenced) promoted allogeneic bone marrow engraftment under CD40L blockade and rapamycin. This effect was even more pronounced when combined with a transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β fusion protein 45. The discrepancy between both administration forms of IL‐2 may be related to the distinct binding behaviour to the IL‐2 receptor as well as to differences in the Fc portion 46, 47. Other pharmaceuticals have been proposed to expand Tregs in vivo in order to ameliorate GVHD 48, 49, but have not been tested so far in the effort to induce mixed chimerism.

Space requirement for stem cells

The development of irradiation‐free protocols has raised the question of whether distinct niches need to be emptied actively in the recipient for stem cells contained in conventional doses of donor bone marrow to engraft 50. Several models achieving sustained levels of mixed chimerism without creating ‘space’ for donor bone marrow argue against the requirement for emptying niches 33, 38. These observations do not negate that creating additional space promotes bone marrow engraftment further. Mobilizing recipient bone marrow with a CXCR4 antagonist (AMD3100) enhanced mixed chimerism in a congenic mouse model 52. In the allogeneic setting AMD3100 increased donor chimerism shortly after BMT, but the effect vanished gradually over time without promoting skin graft tolerance 53. Depriving CXCR4 from its ligand CD26 by Diprotin A or sitagliptin did not improve bone marrow engraftment in non‐myeloblative irradiated recipients 54. In contrast, depleting haematopoietic stem cells from their niches by an antibody directed against the stem cell factor c‐Kit was effective in establishing donor bone marrow engraftment in immunodeficient mice. In combination with blockade of CD47, α‐c‐Kit antibodies even extinguished > 99% of host haematopoietic stem cells, thus promoting bone marrow engraftment in immunocompetent mice 55. Accordingly, creating space itself enhances bone marrow engraftment, but needs to be combined with strategies to prevent rejection of allogeneic cells to be most effective.

Innate immunity rises from the shadow

Adaptive immunity has long been regarded as the driving force of organ transplant rejection. Nonetheless, innate immunity emerged as crucial additional contributor to alloresponses, especially in the absence of co‐stimulatory signalling 56, 57. Innate immune cells infiltrate the graft in response to the inflammation elicited by the surgical trauma and ischaemia/reperfusion injury, become activated and augment adaptive immunity through the release of proinflammatory cytokines. However, growing evidence suggests that innate cells themselves also possess the ability to recognize foreign tissues despite the lack of somatically rearranged receptors 58. In contrast to organ transplants, NK cells have long been recognized as major mediators of cell transplant rejection, as they readily kill allogeneic bone marrow through their ability to recognize ‘missing‐self’59. NK cells are resistant to co‐stimulation blockade 60 and their depletion or blockade [through lymphocyte function‐associated antigen 1 (LFA1)], which is necessary for NK–target cell interactions 61), promoted engraftment of conventional numbers of allogeneic bone marrow under co‐stimulation blockade and busulfan 62. Apart from NK cells, monocytes have been reported to augment allograft rejection by non‐self‐recognition which is driven by CD47/signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) interactions 63. CD47 is expressed on a wide range of cells and delivers a ‘don't eat me’ signal to macrophages via ligation of SIRPα. The highly polymorphic binding site of SIRPα presumably explains the ability of monocytes/macrophages to discriminate between self and non‐self 64. With regard to bone marrow transplantation, it is noteworthy that CD47 is also present on haematopoietic stem cells and progenitors. CD47–/– BM cannot engraft in lethally irradiated syngeneic WT mice 65, implying that macrophages engulf stem cells if their SIRPα receptor cannot bind CD47 66, 67. In line with this, the macrophage depleting agent clodronate promoted the induction of haematopoietic chimerism and donor‐specific skin graft tolerance 68.

Mechanisms preserving tolerance

Depending on the specifics of the regimen used to induce mixed chimerism, tolerance is maintained by different mechanisms which can be divided broadly into deletional and regulatory. The specific elimination of alloreactive T cell clones (clonal deletion) can occur either in the thymus (central deletion) or the periphery (peripheral deletion). In chimeras, newly developing T cells directed against alloantigens are deleted specifically in the thymus by donor APCs arising from the BM graft 69, 70. Dendritic cells have long been implicated as the primary source of donor APCs in the thymus, although it is now acknowledged widely that there is an intensive cross‐talk between the thymus and the periphery 71. In particular, activated T cells, Tregs and B cells have been shown to re‐enter the thymus and to participate in negative selection 72, 73, 74. So far, however, the influence of these cell populations for clonal deletion in mixed chimeras remains undefined. Sparing the pre‐existing T cell pool by avoiding T cell depletion through co‐stimulation blockade revealed that alloreactive T cells can also be purged in the periphery. Peripheral deletion is a rapid process that is initiated shortly after BMT 24, 75. Nevertheless, it has been recognized for a long period of time that some grafts were still rejected in mixed chimeras even despite seemingly complete clonal deletion. This phenomenon was more pronounced in the presence of minor antigen disparities, implying a role for indirect alloreactivity 76, 77. So far, the available methodologies have only allowed assessing the deletion of ‘direct’ alloreactive T cells, while the fate of ‘indirect’ alloreactive T cells remains an unresolved issue. Several studies, however, indicated that regulatory mechanisms can control indirect alloreactivity 77. In an irradiation‐free protocol deploying Treg transfer, active regulatory mechanisms preserved tolerance to minor antigen disparities in the absence of complete clonal deletion 39. Endogenous thymus‐derived Tregs were recruited to the graft, where they kept alloreactive T effector cells at bay. Depleting Tregs (α‐CD25) or blocking their effector molecules (α‐PD1, α‐CTLA4) suspended the cover of regulation leading to rapid rejection of the tolerized grafts. The infused Tregs seemed to pass on their suppressive behaviour as they vanished over time 77. This observation was also made in a non‐myeloablative model based on Treg therapy in which the injected cells were required for the induction of tolerance, but not its maintenance 78. The significance for intragraft regulation probably lies in its ability to control alloimunity directed against tissue‐specific donor antigens.

The balanced interplay of clonal deletion and regulation seems to be the most solid foundation for a durable and stable state of tolerance. Deletional mechanisms are more robust, as they physically eliminate alloreactive T cells which can then no longer be reactivated subsequently during the course of an inflammation. In line with this, viral infection of stable mixed chimeras exhibiting complete clonal deletion neither broke tolerance nor abrogated chimerism 79. Moreover, clonal deletion is necessary to reduce the clone size of MHC‐reactive T cells. Conversely, T cells recognizing antigens expressed on donor bone marrow can undergo clonal deletion while T cells reactive towards tissue‐specific antigens (e.g. skin) possibly escape. This might explain why some protocols induce tolerance to certain tissues (e.g. haematopoietic cells) while others (e.g. skin) are rejected, a phenomenon known as split tolerance 80. Therefore, regulatory mechanisms are critical, as they are capable of tolerizing tissue‐specific antigens expressed by the transplanted organ. Regulatory mechanisms are, however, more susceptible to environmental influences. In this regard, TLR agonists abrogated co‐stimulation blockade‐induced prolongation of skin 81, and tolerance towards heart allografts induced by α‐CD40L and donor‐specific transfusion could be broken easily upon infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Intriguingly, the donor‐specific tolerance re‐emerged after clearance of the pathogen, as shown by the acceptance of a donor‐matched second transplant 82.

It has been described recently that cells of the innate immune system can also exhibit features of adaptive immunity 83, raising the question of whether innate cells can adapt to donor antigens. NK cells readily reject allogeneic bone marrow cells through missing‐self recognition, but are apparently tolerant towards donor and recipient cells in stable mixed chimeras. In non‐myeloablative models, NK cell tolerance could be broken by high amounts of IL‐2 in vitro but not in vivo 84, 85. Restoration of NK cell alloreactivity implies that NK cells adjust their activation threshold towards donor cells rather than being deleted. Studies with MHC class I‐deficient bone marrow have already suggested that NK cells adapt readily to the surrounding supply of MHC molecules 86. Recently, we found that NK cells of mixed chimeras reshape their receptor repertoire in favour of donor MHC to attenuate alloreactivity 87. However, the detailed mechanisms how NK cells are tolerized towards donor antigens in mixed chimeras currently remains incompletely understood (Fig. 1).

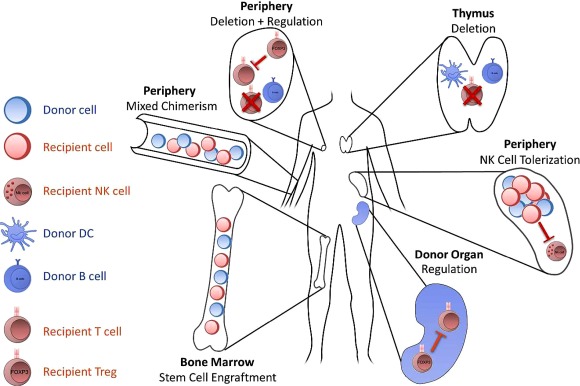

Figure 1.

Mechanisms maintaining tolerance in mixed chimeras: the following mechanisms contribute to tolerance after donor stem cells have engrafted in a recipient's bone marrow niches, leading to hematopoietic mixed chimerism. Donor‐derived antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) (dendritic cells and B cells) invade the thymus to eliminate developing donor‐reactive T cells (central clonal deletion). Pre‐existing alloreactive T cells and those escaping central deletion are either eliminated in the periphery (peripheral clonal deletion) or suppressed by regulatory T cells (Tregs) (peripheral regulation). Peripheral regulation can either occur in secondary lymphoid organs or in the allograft itself (intragraft regulation). Natural killer (NK) cells adapt to donor cells by reshaping their receptor repertoire (NK cell education).

Roadblocks limiting mouse models

Recently, the usability of young and healthy mice to predict reliably the behaviour of the experienced immune system of human patients has been increasingly questioned 88. A major cause for this discrepancy is the high frequency of alloreactive memory T cells found in adult humans in contrast to laboratory mice 89. Memory T cells are less susceptible to regulatory mechanisms of the immune system and are less affected by immunosuppressive drugs than naive T cells 90. Due to the advanced age of most transplant recipients, their immune system is highly experienced and compromises an increased pool of memory T cells, as well as other alterations of their immune system, which may hamper the potential to induce tolerance 91, 92. When a model of mixed chimerism established in young mice was tested in old mice it was found that advanced age by itself does not impair bone marrow engraftment or tolerance induction. The overall frequency of memory T cells increased with age, but without a detectable concomitant increase in alloreactive memory T cells 93. In an alternative approach, BMT recipients enriched with donor‐reactive memory T cells were exploited as a model to identify strategies that overcome the barrier of T cell sensitization without concomitant humoral sensitization. Adjunctive short‐term treatment with rapamycin or α‐LFA‐1 was effective in counteracting donor‐reactive memory T cells in this model, leading to long‐term mixed chimerism and donor‐specific tolerance 94, suggesting that chimerism protocols developed in young laboratory mice can be translated to clinically more relevant settings with moderate adaptations. Another circumstance that aggravates the interpretation of several mouse studies is the use of clinically unrealistic mismatch combinations. Several studies of mixed chimerism deployed strain combinations without minor antigen disparities which, however, exist universally in the human setting, and have been shown recently in murine models to impede long‐lasting chimerism and tolerance 76, 95.

Skin grafts are used commonly to monitor tolerance as they are technically not challenging, considered to be very immunogenic and are easy to monitor 96. However, the mechanisms of skin rejection differ greatly from that of primarily vascularized grafts. Kidney allografts would be most appropriate as they are also used in human tolerance studies, but are accepted spontaneously in several mouse strain combinations 97 and murine kidney transplant models are performed rarely due to technical challenges. Cardiac allografts are currently the most appreciated model of vascularized transplants, but also suffer from some disadvantages. In mice, heart allografts are regarded typically as rejected if no heartbeat is palpable, but substantial immunological damage can occur in the heterotopic, non‐life‐sustaining heart graft long before it stops beating. Therefore, a combination of donor graft types should be evaluated ideally in murine studies.

In order to allow translation of a protocol from mouse to humans, pharmaceuticals which are currently available, or will be in the foreseeable future, should be used. In most murine protocols a blocking antibody against CD40L is used to induce tolerance. In the human setting α‐CD40L antibodies were withdrawn from the market due to thromboembolic complications 98. Although several encouraging alternatives are currently tested, it is still unclear if and when they will reach clinical maturity 99. Blocking CD40 may not be equivalent to blocking CD40L, as CD40L can also ligate CD11b (Mac‐1) 100. Recently, it was shown that CTLA4‐Ig and rapamycin synergizes in a non‐myleoablative BMT model to replace α‐CD40L 101, at least to some degree, suggesting that CD40L blockade is not indispensable in chimerism‐based tolerance approaches. Similarly, bone marrow doses should be used that are clinically feasible. Typically, 15–20 × 106 unseparated bone marrow cells are used to induce mixed chimerism, although this already constitutes the upper limit of clinical feasibility. Furthermore, in the clinic, mobilized peripheral blood stem cells are often preferred over unfractioned bone marrow 102. Notably, in mice, murine‐mobilized peripheral blood stem cells were less potent than bone marrow to induce mixed chimerism due to a higher amount of T cells 103, highlighting the importance of the donor cell source (Fig. 2).

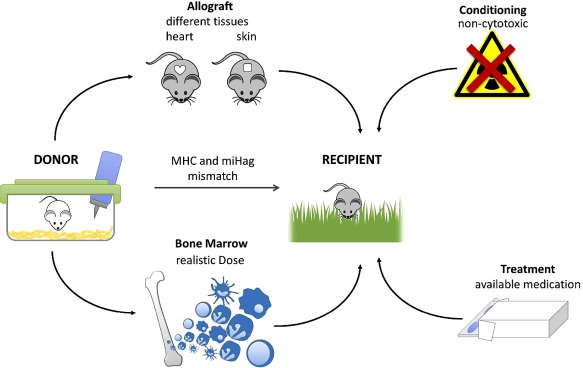

Figure 2.

Factors influencing the translational relevance of mouse studies for chimerism‐based tolerance: Several factors make mouse protocols more relevant for potential clinical translation. With regard to patient safety, conditioning should ideally be non‐cytotoxic and drugs tested should be clinically available or at least under development. The donor and recipient pairs should be mismatched in major (MHC) and minor antigens (miHag), as is typically the case in clinical transplantation. A clinically realistic dose of donor bone marrow should be deployed and recipients of different ages should be tested. Different types of donor grafts (e.g. heart and skin) should be evaluated to test for tolerance in order to allow assessment of acute and chronic immunological damage and to include a range of tissue‐specific antigens. Mice not kept under specific pathogen‐free conditions should be evaluated as recipients, as heterologous immunity constitutes a considerable barrier to tolerance induction.

Summary and outlook

Chimerism‐based tolerance remains an attractive strategy for clinical translation and has recently proved its feasibility in a set of pilot trials. Three centres in the United States have elaborated distinct approaches to induce tolerance in recipients of living donor kidney transplants via donor haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Tolerance was achieved in approximately 50% of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)‐mismatched patients, but safety issues were also noted. These trials are discussed in detail in a separate paper within this review series 104. Despite varying degrees of success, these trials constitute an important step towards clinical translation. Efforts are now being made to improve both efficacy and safety of current conditioning regimens in order to allow broader application. Those trials are based on protocols whose principles have been generated in mouse models, demonstrating the important role of mouse studies as a basis for the development of clinical tolerance strategies. Recent advances have allowed to reduce and to almost eliminate the remaining toxicity of chimerism protocols in mice and might pave the way for a more widespread clinical translation of this approach.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

The research of the authors has been supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, TRP151 and W1212 to T.W.).

References

- 1. Grinyo JM. Why is organ transplantation clinically important? Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013; 3:a014985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brouard S, Budde K. Current status of immunosuppressive minimization and tolerance strategies. Transpl Int 2015; 28:889–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finger EB, Strom TB, Matas AJ. Tolerance – is it worth it? Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2014; 4:a015594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pilat N, Wekerle T. Transplantation tolerance through mixed chimerism. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010; 6:594–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chong AS, Alegre ML, Miller ML, Fairchild RL. Lessons and limits of mouse models. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013; 3:a015495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Billingham RE, Brent L, Medawar PB. Actively acquired tolerance of foreign cells. Nature 1953; 172:603–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Main JM, Prehn RT. Successful skin homografts after the administration of high dosage X‐radiation and homologous bone marrow. J Natl Cancer Inst 1955; 15:1023–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trentin JJ. Tolerance and homologous disease in irradiated mice protected with homologous bone marrow. Ann NY Acad Sci 1958; 73:799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martin PJ, Hansen JA, Torokstorb B et al Graft failure in patients receiving T‐cell‐depleted Hla‐identical allogeneic marrow transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant 1988; 3:445–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palathumpat V, Dejbakhsh‐Jones S, Strober S. The role of purified CD8+ T cells in graft‐versus‐leukemia activity and engraftment after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation 1995; 60:355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Slavin S, Strober S, Fuks Z, Kaplan HS. Induction of specific tissue transplantation tolerance using fractionated total lymphoid irradiation in adult mice: long‐term survival of allogeneic bone marrow and skin grafts. J Exp Med 1977; 146:34–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lan FS, Zeng DF, Higuchi M, Huie P, Higgins JP, Strober S. Predominance of NK1·1(+)TCR alpha beta(+) or DX5(+)TCR alpha beta(+) T cells in mice conditioned with fractionated lymphoid irradiation protects against graft‐versus‐host disease: ‘natural suppressor’ cells. J Immunol 2001; 167:2087–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ildstad ST, Wren SM, Bluestone JA, Barbieri SA, Sachs DH. Characterization of mixed allogeneic chimeras. Immunocompetence, in vitro reactivity, and genetic specificity of tolerance. J Exp Med 1985; 162:231–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zinkernagel RM, Althage A, Callahan G, Welsh RM. On the immunocompetence of H‐2 incompatible irradiation bone‐marrow chimeras. J Immunol 1980; 124:2356–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ildstad ST, Sachs DH. Reconstitution with syngeneic plus allogeneic or xenogeneic bone marrow leads to specific acceptance of allografts or xenografts. Nature 1984; 307:168–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sprent J, Schaefer M, Lo D, Korngold R. Properties of purified T‐cell subsets. 2. In vivo responses to class‐I vs class‐II H‐2 differences. J Exp Med 1986; 163:998–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cobbold SP, Martin G, Qin S, Waldmann H. Monoclonal‐antibodies to promote marrow engraftment and tissue graft tolerance. Nature 1986; 323:164–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sharabi Y, Sachs DH. Mixed chimerism and permanent specific transplantation tolerance induced by a nonlethal preparative regimen. J Exp Med 1989; 169:493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sykes M, Szot GL, Swenson KA, Pearson DA. Induction of high levels of allogeneic hematopoietic reconstitution and donor‐specific tolerance without myelosuppressive conditioning. Nat Med 1997; 3:783–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wekerle T, Nikolic B, Pearson DA, Swenson KG, Sykes M. Minimal conditioning required in a murine model of T cell depletion, thymic irradiation and high‐dose bone marrow transplantation for the induction of mixed chimerism and tolerance. Transpl Int 2002; 15:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haynes BF, Markert ML, Sempowski GD, Patel DD, Hale LP. The role of the thymus in immune reconstitution in aging, bone marrow transplantation, and HIV‐1 infection. Annu Rev Immunol 2000; 18:529–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qin SX, Cobbold S, Benjamin R, Waldmann H. Induction of classical transplantation tolerance in the adult. J Exp Med 1989; 169:779–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang MA, Racine JJ, Song XP et al Mixed chimerism and growth factors augment beta cell regeneration and reverse late‐stage type 1 diabetes. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4:133ra59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wekerle T, Sayegh MH, Hill J et al Extrathymic T cell deletion and allogeneic stem cell engraftment induced with costimulatory blockade is followed by central T cell tolerance. J Exp Med 1998; 187:2037–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wekerle T, Kurtz J, Ito H et al Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation with co‐stimulatory blockade induces macrochimerism and tolerance without cytoreductive host treatment. Nat Med 2000; 6:464–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Durham MM, Bingaman AW, Adams AB et al Cutting edge: administration of anti‐CD40 ligand and donor bone marrow leads to hemopoietic chimerism and donor‐specific tolerance without cytoreductive conditioning. J Immunol 2000; 165:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blaha P, Bigenzahn S, Koporc Z et al The influence of immunosuppressive drugs on tolerance induction through bone marrow transplantation with costimulation blockade. Blood 2003; 101:2886–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schenk AD, Gorbacheva V, Rabant M, Fairchild RL, Valujskikh A. Effector functions of donor‐reactive CD8 memory T cells are dependent on ICOS induced during division in cardiac grafts. Am J Transplant 2009; 9:64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Demirci GI, Amanullah F, Kewalaramani R et al Critical role of OX40 in CD28 and CD154‐independent rejection. J Immunol 2004; 172:1691–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis‐Mortari A, Freeman GJ et al Targeting of inducible costimulator (ICOS) expressed on alloreactive T cells down‐regulates graft‐versus‐host disease (GVHD) and facilitates engraftment of allogeneic bone marrow (BM). Blood 2005; 105:3372–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blazar BR, Sharpe AH, Chen AI et al Ligation of OX40 (CD134) regulates graft‐versus‐host disease (GVHD) and graft rejection in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. Blood 2003; 101:3741–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blaha P, Bigenzahn S, Koporc Z, Sykes M, Muehlbacher F, Wekerle T. Short‐term immunosuppression facilitates induction of mixed chimerism and tolerance after bone marrow transplantation without cytoreductive conditioning. Transplantation 2005; 80:237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cippa PE, Gabriel SS, Chen J et al Targeting apoptosis to induce stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism and long‐term allograft survival without myelosuppressive conditioning in mice. Blood 2013; 122:1669–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gabriel SS, Bon N, Chen J et al Distinctive expression of Bcl‐2 factors in regulatory T cells determines a pharmacological target to induce immunological tolerance. Front Immunol 2016; 7:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scalea JR, Tomita Y, Lindholm CR, Burlingham W. Transplantation tolerance induction: cell therapies and their mechanisms. Front Immunol 2016; 7:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Waldmann H, Hilbrands R, Howie D, Cobbold S. Harnessing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells for transplantation tolerance. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:1439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Romano M, Tung SL, Smyth LA, Lombardi G. Treg therapy in transplantation a general overview. Transpl Int 2016; in press. doi: 10.1111/tri.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pilat N, Baranyi U, Klaus C et al Treg‐therapy allows mixed chimerism and transplantation tolerance without cytoreductive conditioning. Am J Transplant 2010; 10:751–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pilat N, Farkas AM, Mahr B et al T‐regulatory cell treatment prevents chronic rejection of heart allografts in a murine mixed chimerism model. J Heart Lung Transplant 2014; 33:429–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pilat N, Klaus C, Hock K et al Polyclonal recipient nTregs are superior to donor or third‐party Tregs in the induction of transplantation tolerance. J Immunol Res 2015; 2015:562935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Duran‐Struuck R, Sondermeijer HP, Buhler L et al Effect of ex vivo‐expanded recipient regulatory T cells on hematopoietic chimerism and kidney allograft tolerance across MHC barriers in cynomolgus macaques. Transplantation 2017; 101:274–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ruiz P, Maldonado P, Hidalgo Y, Sauma D, Rosemblatt M, Bono MR. Alloreactive regulatory T cells allow the generation of mixed chimerism and transplant tolerance. Front Immunol 2015; 6:596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boyman O, Kovar M, Rubinstein MP, Surh CD, Sprent J. Selective stimulation of T cell subsets with antibody–cytokine immune complexes. Science 2006; 311:1924–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Webster KE, Walters S, Kohler RE et al In vivo expansion of Treg cells with IL‐2‐mAb complexes: induction of resistance to EAE and long‐term acceptance of islet allografts without immunosuppression. J Exp Med 2009; 206:751–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mahr B, Unger L, Hock K et al IL‐2/alpha‐il‐2 complex treatment cannot be substituted for the adoptive transfer of regulatory T cells to promote bone marrow engraftment. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0146245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xu H, Zheng XX, Zhang W, Huang Y, Ildstad ST. A critical role for TGF‐beta/Fc and nonlytic IL‐2/Fc fusion proteins in promoting chimerism and donor‐specific tolerance. Transplantation 2017; 101:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Spangler JB, Tomala J, Luca VC et al Antibodies to interleukin‐2 elicit selective T cell subset potentiation through distinct conformational mechanisms. Immunity 2015; 42:815–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zheng XX, Steele AW, Hancock WW et al IL‐2 receptor‐targeted cytolytic IL‐2/Fc fusion protein treatment blocks diabetogenic autoimmunity in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol 1999; 163:4041–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chopra M, Biehl M, Steinfatt T et al Exogenous TNFR2 activation protects from acute GvHD via host Treg cell expansion. J Exp Med 2016; 213:1881–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim BS, Nishikii H, Baker J et al Treatment with agonistic DR3 antibody results in expansion of donor Tregs and reduced graft‐versus‐host disease. Blood 2015; 126:546–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bhattacharya D, Ehrlich LI, Weissman IL. Space‐time considerations for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur J Immunol 2008; 38:2060–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen J, Larochelle A, Fricker S, Bridger G, Dunbar CE, Abkowitz JL. Mobilization as a preparative regimen for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2006; 107:3764–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li Z, Xu X, Weiss ID, Jacobson O, Murphy PM. Pre‐treatment of allogeneic bone marrow recipients with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 transiently enhances hematopoietic chimerism without promoting donor‐specific skin allograft tolerance. Transpl Immunol 2015; 33:125–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schwaiger E, Klaus C, Matheeussen V et al Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV/CD26) inhibition does not improve engraftment of unfractionated syngeneic or allogeneic bone marrow after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Exp Hematol 2012; 40:97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chhabra A, Ring AM, Weiskopf K et al Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in immunocompetent hosts without radiation or chemotherapy. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8:351ra105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. McNerney ME, Lee KM, Zhou P et al Role of natural killer cell subsets in cardiac allograft rejection. Am J Transplant 2006; 6:505–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Maier S, Tertilt C, Chambron N et al Inhibition of natural killer cells results in acceptance of cardiac allografts in CD28–/– mice. Nat Med 2001; 7:557–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Farrar CA, Kupiec‐Weglinski JW, Sacks SH. The innate immune system and transplantation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013; 3:a015479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Velardi A. Natural killer cell alloreactivity 10 years later. Curr Opin Hematol 2012; 19:421–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Westerhuis G, Maas WGE, Willemze R, Toes REM, Fibbe WE. Long‐term mixed chimerism after immunologic conditioning and MHC‐mismatched stem‐cell transplantation is dependent on NK‐cell tolerance. Blood 2005; 106:2215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barber DF, Faure M, Long EO. LFA‐1 contributes an early signal for NK cell cytotoxicity. J Immunol 2004; 173:3653–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kean LS, Hamby K, Koehn B et al NK cells mediate costimulation blockade‐resistant rejection of allogeneic stem cells during nonmyeloablative transplantation. Am J Transplant 2006; 6:292–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oberbarnscheidt MH, Zeng Q, Li Q et al Non‐self recognition by monocytes initiates allograft rejection. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:3579–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Takenaka K, Prasolava TK, Wang JC et al Polymorphism in Sirpa modulates engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol 2007; 8:1313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Blazar BR, Lindberg FP, Ingulli E et al CD47 (integrin‐associated protein) engagement of dendritic cell and macrophage counterreceptors is required to prevent the clearance of donor lymphohematopoietic cells. J Exp Med 2001; 194:541–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jaiswal S, Jamieson CH, Pang WW et al CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell 2009; 138:271–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kuriyama T, Takenaka K, Kohno K et al Engulfment of hematopoietic stem cells caused by down‐regulation of CD47 is critical in the pathogenesis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 2012; 120:4058–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li Z, Xu X, Feng X, Murphy PM. The macrophage‐depleting agent clodronate promotes durable hematopoietic chimerism and donor‐specific skin allograft tolerance in mice. Sci Rep 2016; 6:22143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Manilay JO, Pearson DA, Sergio JJ, Swenson KG, Sykes M. Intrathymic deletion of alloreactive T cells in mixed bone marrow chimeras prepared with a nonmyeloablative conditioning: regimen. Transplantation 1998; 66:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Khan A, Tomita Y, Sykes M. Thymic dependence of loss of tolerance in mixed allogeneic bone marrow chimeras after depletion of donor antigen – peripheral mechanisms do not contribute to maintenance of tolerance. Transplantation 1996; 62:380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lopes N, Serge A, Ferrier P, Irla M. Thymic crosstalk coordinates medulla organization and T‐Cell tolerance induction. Front Immunol 2015; 6:365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Thiault N, Darrigues J, Adoue V et al Peripheral regulatory T lymphocytes recirculating to the thymus suppress the development of their precursors. Nat Immunol 2015; 16:628–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Agus DB, Surh CD, Sprent J. Reentry of T cells to the adult thymus is restricted to activated T cells. J Exp Med 1991; 173:1039–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yamano T, Nedjic J, Hinterberger M et al Thymic B cells are licensed to present self antigens for central T cell tolerance induction. Immunity 2015; 42:1048–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Fehr T, Takeuchi Y, Kurtz J, Wekerle T, Sykes M. Early regulation of CD8 T cell alloreactivity by CD4(+)CD25(‐) T cells in recipients of anti‐CD154 antibody and allogeneic BMT is followed by rapid peripheral deletion of donor‐reactive CD8(+) T cells, precluding a role for sustained regulation. Eur J Immunol 2005; 35:2679–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bigenzahn S, Pree I, Klaus C et al Minor antigen disparities impede induction of long lasting chimerism and tolerance through bone marrow transplantation with costimulation blockade. J Immunol Res 2016; 2016:8635721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pilat N, Mahr B, Unger L et al Incomplete clonal deletion as prerequisite for tissue‐specific minor antigen tolerization. JCI Insight 2016; 1:e85911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pasquet L, Douet JY, Sparwasser T, Romagnoli P, van Meerwijk JP. Long‐term prevention of chronic allograft rejection by regulatory T‐cell immunotherapy involves host Foxp3‐expressing T cells. Blood 2013; 121:4303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Williams MA, Tan JT, Adams AB et al Characterization of virus‐mediated inhibition of mixed chimerism and allospecific tolerance. J Immunol 2001; 167:4987–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Al‐Adra DP, Anderson CC. Mixed chimerism and split tolerance: mechanisms and clinical correlations. Chimerism 2014; 2:89–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Thornley TB, Brehm MA, Markees TG et al TLR agonists abrogate costimulation blockade‐induced prolongation of skin allografts. J Immunol 2006; 176:1561–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Miller ML, Daniels MD, Wang TM et al Spontaneous restoration of transplantation tolerance after acute rejection. Nat Commun 2015; 6:7566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cell memory in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16:112–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhao Y, Ohdan H, Manilay JO, Sykes M. NK cell tolerance in mixed allogeneic chimeras. J Immunol 2003; 170:5398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Manilay JO, Waneck GL, Sykes M. Altered expression of Ly‐49 receptors on NK cells developing in mixed allogeneic bone marrow chimeras. Int Immunol 1998; 10:1943–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kim S, Poursine‐Laurent J, Truscott SM et al Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature 2005; 436:709–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mahr B, Pilat N, Maschke S et al Regulatory T cells promote natural killer cell education in mixed chimeras. Am J Transplant 2017; doi: 10.1111/ajt.14342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Beura LK, Hamilton SE, Bi K et al Normalizing the environment recapitulates adult human immune traits in laboratory mice. Nature 2016; 532:512–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Krummey SM, Ford ML. Heterogeneity within T cell memory: implications for transplant tolerance. Front Immunol 2012; 3:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Su CA, Fairchild RL. Memory T cells in transplantation. Curr Transplant Rep 2014; 1:137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhai Y, Meng LZ, Gao F, Busuttil RW, Kupiec‐Weglinski JW. Allograft rejection by primed/memory CD8+ T cells is CD154 blockade resistant: therapeutic implications for sensitized transplant recipients. J Immunol 2002; 169:4667–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Adams AB, Williams MA, Jones TR et al Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. J Clin Invest 2003; 111:1887–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hock K, Oberhuber R, Lee Y‐L, Wrba F, Wekerle T, Tullius SG. Immunosenescence does not abrogate engraftment of murine allogeneic bone marrow. Transplantation 2013; 95:1431–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ramsey H, Pilat N, Hock K et al Anti‐LFA‐1 or rapamycin overcome costimulation blockade‐resistant rejection in sensitized bone marrow recipients. Transpl Int 2013; 26:206–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Cao TM, Lo B, Ranheim EA, Grumet FC, Shizuru JA. Variable hematopoietic graft rejection and graft‐versus‐host disease in MHC‐matched strains of mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100:11571–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Benichou G, Yamada Y, Yun SH, Lin C, Fray M, Tocco G. Immune recognition and rejection of allogeneic skin grafts. Immunotherapy 2011; 3:757–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Meng LZ, Wu Z, Wang Y et al Differential impact of CD154 costimulation blockade on alloreactive effector and regulatory T cells in murine renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 2008; 85:1332–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kawai T, Andrews D, Colvin RB, Sachs DH, Cosimi AB. Thromboembolic complications after treatment with monoclonal antibody against CD40 ligand. Nat Med 2000; 6:114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Xie JH, Yamniuk AP, Borowski V et al Engineering of a novel anti‐CD40L domain antibody for treatment of autoimmune diseases. J Immunol 2014; 192:4083–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wolf D, Hohmann JD, Wiedemann A et al Binding of CD40L to Mac‐1's I‐domain involves the EQLKKSKTL motif and mediates leukocyte recruitment and atherosclerosis – but does not affect immunity and thrombosis in mice. Circ Res 2011; 109:1269–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Pilat N, Klaus C, Schwarz C et al Rapamycin and CTLA4Ig synergize to induce stable mixed chimerism without the need for CD40 blockade. Am J Transplant 2015; 15:1568–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ et al Peripheral‐blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1487–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Koporc Z, Pilat N, Nierlich P et al Murine mobilized peripheral blood stem cells have a lower capacity than bone marrow to induce mixed chimerism and tolerance. Am J Transplant 2008; 8:2025–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Oura T, Cosimi AB, Kawai T. Chimerism‐based tolerance in organ transplantation: preclinical and clinical studies. Clin and Exp Immunol 2017; doi: 10.1111/cei.12969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]