Abstract

Aim

To retrospectively compare the initial response, local recurrence, and complication rates of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs microwave ablation (MWA) when combined with neoadjuvant bland transarterial embolization (TAE) or drug eluting microsphere chemoembolization (TACE) for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

A total of 35 subjects with BCLC very early and early stage HCC (range 1.2 – 4.1 cm) underwent TAE (23) or TACE (12) with RFA (15) or MWA (20) from 1/2009–6/2015 as either definitive therapy or a bridge to transplant. TAE and TACE were performed with 40–400 μm particles and 30–100 μm plus either Doxorubicin or Epirubicin eluting microspheres respectively. Initial response and local progression were evaluated using modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST). Complications were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Results

Complete response (CR) rates were 80% (12/15) for RFA + TAE/TACE and 95% (19/20) for MWA + TAE/TACE (p value 0.29). Local recurrence (LR) was 30% (4/12) for RFA + TAE/TACE and 0% (0/19) for MWA + TAE/TACE. Durability of response (DR), defined as local disease control for duration of the study, demonstrated a significant difference in favor of MWA (p value 0.0091). There was no statistical difference in complication rates (3 vs 2).

Conclusions

MWA and RFA when combined with neoadjuvant TAE or TACE have similar safety and efficacy in the treatment of early stage HCC. MWA provided more durable disease control in this study, however, prospective data remains necessary to evaluate superiority of either modality.

Keywords: Ablation Techniques, Carcinoma, Hepatocellular, Embolization, Therapeutic, Radiology, Interventional, Retrospective Studies

Introduction

The incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has risen in the US over the past 2 decades (1). Approximately 80% of patients present with advanced disease or poor liver function and are ineligible for surgical resection or transplantation (2). Many patients with early, non-resectable, disease are candidates for locoregional therapies with curative intent, palliation, or as a bridge to transplantation (3, 4).

Thermal ablative therapies such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA) induce tumor cell death via coagulative necrosis. RFA is universally adopted, well studied, and recommended by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) (4, 5). Disadvantages to RFA include susceptibility to heat sink, charring, limited ablation volume, the need for grounding pads, and some monopolar probe designs (6). Despite having less available data, MWA utilization has been increasing over the past two decades (7). MWA appears to resist heat sink, is unaffected by charring, generates larger ablation zones, shorter ablation times, and does not require grounding pads (6, 8). Recent advancements in microwave probe technology allow for more predictable ablation zones (9), which can be tailored to lesion morphology (10).

Our institution utilizes DEB-TACE or TAE prior to most hepatic thermal ablations for HCC to theoretically augment efficacy by decreasing heat sink, improving lesion visualization, and potentially treat under-staged microsatellite disease within the treated angiosome. In our cohort we included those who were treated with bland or chemoembolization prior to ablation as a definitive therapy or as a bridge to transplantation. We hypothesized that MWA plus TACE/TAE would be at least as effective as RFA plus TACE/TAE in initial response and local recurrence.

Methods

This retrospective review was conducted with IRB approval. One hundred twenty six percutaneous ablation cases were reviewed from January 2009–June 2015. Forty-four of these cases were ablations for HCC. Subjects were included for retrospective review if they met the following criteria: diagnosis of HCC via biopsy (8) or diagnostic appearance on multiphase imaging (27), disease confined to the liver without vascular invasion, and treated with combined therapy defined as thermal ablation after transarterial embolization. Subjects were excluded if lost to follow up prior to initial post procedure imaging or BCLC stage C/D. Cohort selection is detailed in Figure 1. Thirty five subjects (15 RFA and 20 MWA) were included in the final analysis. All subjects were treated with TACE or TAE prior to single session ablation per operator preference. Representative cases are pictured in Figures 2 and 3. Subject demographics, baseline hepatic function, and tumor characteristics of both cohorts are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. ECOG status was 0 for all patients. All subjects were discussed at a multidisciplinary HCC conference and treatment with combination therapy was decided by consensus.

Figure 1.

One hundred twenty six percutaneous ablation cases were reviewed. Forty-five of these cases were ablations for HCC. One case was excluded due to palliative abdominal wall HCC metastasis. Of the 9 intrahepatic HCC ablations, 9 were excluded from this cohort due to lack of neoadjuvant embolization (3), insufficient follow up (4), technically unsuccessful procedure (1), and subject request (1).

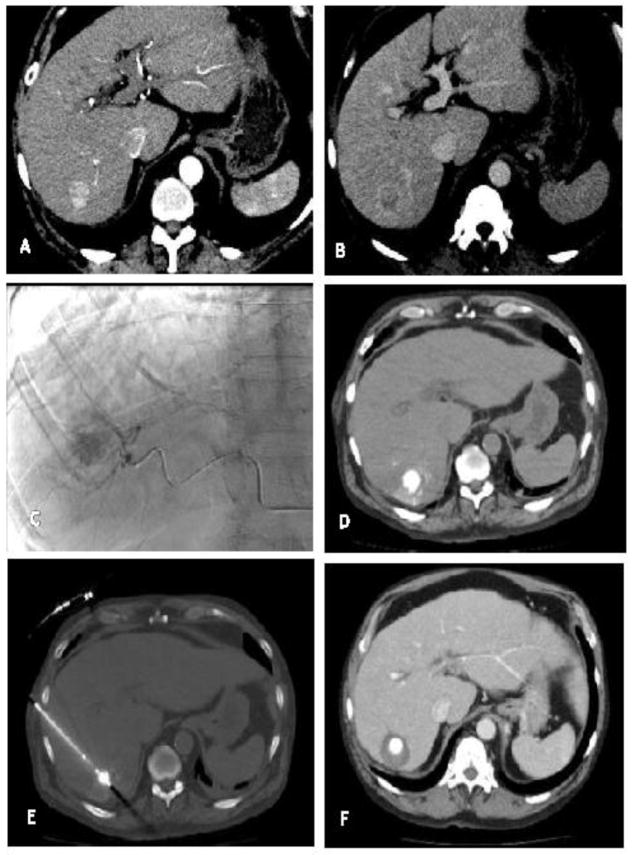

Figure 2.

A) Arterially enhancing hepatic tumor with B) venous washout consistent with HCC C) Conventional transarterial angiography post superselective embolization of a hepatic artery branch feeding the vessel with doxorubicin eluting beads and micellated lipiodol. D) Non-contrast post procedure exam demonstrates deposition of lipiodol within the tumor. E) RFA probe was placed under ultrasound guidance with CT confirmation. F) CT performed approximately 1 month post procedure demonstrates complete response with clear ablation margin.

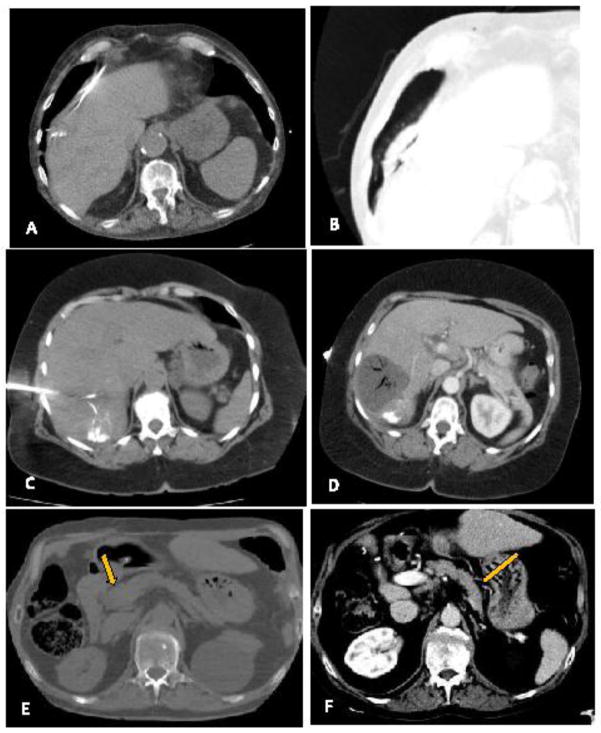

Figure 3.

A) Arterially enhancing hepatic tumor with B) venous washout consistent with HCC C) Conventional transarterial angiography post superselective embolization of a hepatic artery branch feeding the vessel with bland beads and micellated lipiodol. D) Non-contrast post procedure exam demonstrates deposition of lipiodol within the tumor. E) MWA probe was placed under ultrasound guidance with CT confirmation. F) CT performed approximately 1 month post procedure demonstrates complete response with clear ablation margin.

Table 1.

Hepatic Profile

The variables in both groups are listed. There were no statistical differences between patient populations.

| RFA | MWA | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | |||

| Avg Age | 62 | 66.6 | 0.15 |

| Age range | 52–78 | 54–85 | |

| Male | 11 | 18 | 0.367 |

| Female | 4 | 2 | |

| Etiology of Cirrhosis: | |||

| Hepatitis C | 12 (80%) | 12 (60%) | 0.28 |

| Hepatitis B | 1 (7%) | 1 (5%) | |

| NAFLD | 1 (7%) | 1 (5%) | |

| Cryptogenic | 1 (7%) | 2 (10%) | |

| EtOH | 4 (27%) | 5 (25%) | |

| Other | 1 (7%) | 2 (10%) | |

| MELD | 0.125 | ||

| Avg | 8.7 | 9.3 | |

| Range | 6–16 | 6–15 | |

| Child Pugh Score | 0.16 | ||

| % of A | 12 (80%) | 11 (55%) | |

| % of B | 3 (20%) | 9 (45%) | |

| BCLC Stage | |||

| % very early (0) | 4 (27%) | 1 (5%) | 0.14 |

| % early (A) | 11 (73%) | 19 (95%) | |

| Previous Treatment | 0.73 | ||

| 9 (60%) | 10 (50%) | ||

Table 2.

Lesion Characteristics

Characteristics of each lesion are listed. P values are calculated as differences between both groups.

| RFA | MWA | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size of Lesion | |||

| Median | 2.43 | 2.78 | 0.10 |

| Range | 1.2 – 3.6 | 1.6 – 4.1 | |

| Lesion Location | |||

| Segment 2 | 2/15 | 1/20 | |

| Segment 3 | 0/15 | 2/20 | |

| Segment 4a | 2/15 | 1/20 | |

| Segment 4b | 2/15 | 1/20 | |

| Segment 5 | 2/15 | 1/20 | |

| Segment 6 | 2/15 | 7/20 | |

| Segment 7 | 2/15 | 2/20 | |

| Segment 8 | 3/15 | 5/20 | |

| Contacting a Vessel | |||

| 1/15 (7%) | 8/20 (40%) | 0.048 | |

| Complications | |||

| 3/15 (20%) | 2/20 (10%) | 0.377 | |

| Type of embolization | |||

| TACE | 3/15 (20%) | 9/20 (45%) | 0.50 |

| TAE | 12/15 (80%) | 11/20 (55%) | |

Embolization

Subjects underwent either transarterial embolization with 0.5 cc of micelleized lipiodol and either Embozene® Microspheres 40–400 μm (CeloNova BioSciences San Antonio, TX) or transarterial chemoembolization with Epirubicin or Doxorubicin eluting microspheres 30–100 μm (Quadraspheres Merit Medical, South Jordan UT) the day prior to ablation. The procedures were performed using standard angiographic procedure with super selective segmental embolization to stasis.

Radiofrequency Ablation

All RFAs were performed from January 2009–July 2013 using a StarBurst® Rita Medical Systems device (Mountain View, CA) with either the TALON™ (14) or Xli-enhanced™ (1) probes. A single probe was used to ablate the tumor tissue to a target temperature of 105 degrees F. A single probe was felt to be sufficient in all but two cases. In those instances a second sequential ablation was performed using the same probe.

Microwave Ablation

All MWAs were performed from August 2013–June 2015 using a Certus® 140 2.45GHz Neuwave Microwave Ablation System (Madison, WI) with 1–3 CertusPR 15 probes in all cases. Ablation parameters ranged from 30–65 Watts applied for 5–10 minutes. Multiple probes were used to bracket the lesion if the tumor size exceeded the manufacturer suggested ablative area of a single probe.

Surveillance

Initial follow up was performed with multiphase CT or MRI post ablation (11). Institutional guidelines dictated that initial follow up imaging be obtained at 1 month post procedure. Time to initial imaging varied between 1–3 months due to patient and outside referring provider factors. Response was evaluated using Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria (mRECIST) (12). Subjects with persistent disease were treated with either repeat ablation or an alternate therapy decided in multidisciplinary conference. Multiphase CT or MRI was obtained every 3 months to evaluate for disease progression in those with an initial complete response. Imaging modality was chosen based on which best visualized the lesion.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous and categorical variables in the RFA and MWA groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test respectively. Tumor initial response and local recurrence were analyzed using the Kaplan Meier method. All study patients were included in the analysis. Subjects were censored if they received subsequent alternate treatments, were transplanted, lost to follow up, or expired due to alternate causes; all available data prior to these events was, however, used to calculate time to local recurrence. A log rank test was used to compare complications rates and pre and post MELD scores. Univariate analysis using qualitative and quantitative Cox proportional hazards models on selected covariates are listed in Table 4. The following covariates were analyzed: Etiology of cirrhosis (Hepatitis C vs. Others), baseline MELD, Child-Pugh, those who had previous treatment in the area of interest, lesion size, type of transarterial therapy (TACE or TAE). A multivariate analysis was unable to be conducted due to small sample size.

Table 4. Univariate Analysis.

Univariate analysis was performed, however none of the calculated P values came to statistical

| HR | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis C | 0.77 | 0.71 |

| Baseline MELD | 1.01 | 0.93 |

| Child Pugh Score | 0.44 | 0.16 |

| Previous Treatment (No) | 3.08 | 0.16 |

| Lesion Size | 0.76 | 0.62 |

| Transarterial Therapy (TACE) | 0.27 | 0.22 |

Results

Demographics & Hepatic Profile

There was no statistical difference in the age, gender, etiology of cirrhosis, MELD, and Child Pugh score between subjects in the RFA and MWA groups (Tables 1 and 2). While the majority of subjects in the RFA group had Child A cirrhosis, almost half the subjects in the MWA had Child B cirrhosis. The average pre-procedure MELD for the RFA group (8.7, range 6–16) and the MWA group (9.3, range 6–15) were similar.

Lesion Characteristics and Procedural Variables

The MWA lesions ranged from 1.2 cm to 2.63 cm (median 2.7 cm) and the RFA lesions ranged from 1.6 cm to 4.1 cm (median 2.5 cm) (Table 2) with a difference of 0.372 cm (CI −0.895 to 0.152; p value 0.16). In the RFA group, lesions were evenly distributed between segments 2–8, whereas the MWA group showed a greater proportion of segment 7 and 8 lesions. Forty percent of the lesions treated with MWA were in direct contact with a blood vessel compared with 7% in the RFA group (p value of 0.048). TACE was utilized in 3/15 and 9/20 cases in the RFA and MWA groups, respectively (p value of 0.50). No statistical difference in outcomes was observed based on embolic agent (p value of 0.344) with a hazard ratio for TACE of 0.27 with p value of 0.22.

Complication, Length of Stay, Post MELD Scores

Complication rates were similar between each group (p value 0.377). There were 3 CTCAE grade 2 complications in Group 1 (figure 4) including a pneumothorax, uncontrolled abdominal pain secondary to hepatic infarction which required prolonged admission, and tumor seeding secondary to intra-procedural gastric perforation. There was a CTCAE grade 1 and grade 3 complication in Group 2 including an asymptomatic hepatic infarction and an arterioportal fistula which required coil embolization (figure 5).

Figure 4.

A) The RFA probe tine is seen puncturing the pleura during placement, B) causing a pneumothorax. C) The RFA ablation caused larger than intended ablation zone causing severe right upper quadrant pain and prolonged stay in the hospital. D) On follow up imaging, a hepatic infarction can be seen as non-enhancing liver. E) During a left hepatic lobe RFA ablation, the RFA tine punctured the gastric mucosa. This was repositioned prior to ablation. F) However, there was seeding of the gastric mucosa seen on follow up imaging.

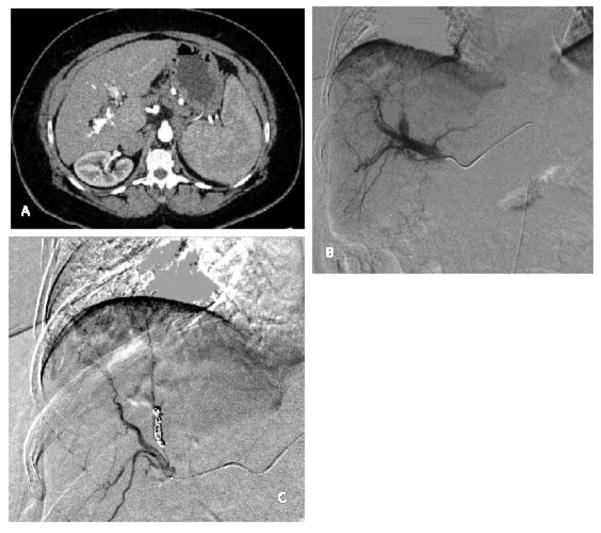

Figure 5.

A) There is a hyperdense arterial phase contrast filling the portal vein and the hepatic arteries consistent an arterioportal fistula secondary to ablation. B) On the subsequent hepatic arteriogram, contrast is seen filling the portal vein. C) Coil embolization of the fistula has been performed. Follow up hepatic arteriogram does not opacity the portal vein.

There was no statistical difference in the hospital length of stay between groups. Post procedure MELD scores were calculated at first follow up and were statistically similar between groups (Table 3). The difference between mean pre and post procedure MELD scores was not statistically significant at 0.094 (p value <0.88).

Table 3.

Outcomes

Outcomes and follow up data is listed with p values calculated as differences between groups.

| RFA | MWA | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Response | |||

| 12/15 (80%) | 19/20 (95%) | 0.29 | |

| Median Post Op | 7 | 9.25 | 0.25 |

| MELD | |||

| Median Follow up | 18 | 14 | 0.071 |

| Transplanted | 2 | 5 | 0.681 |

Response Rates

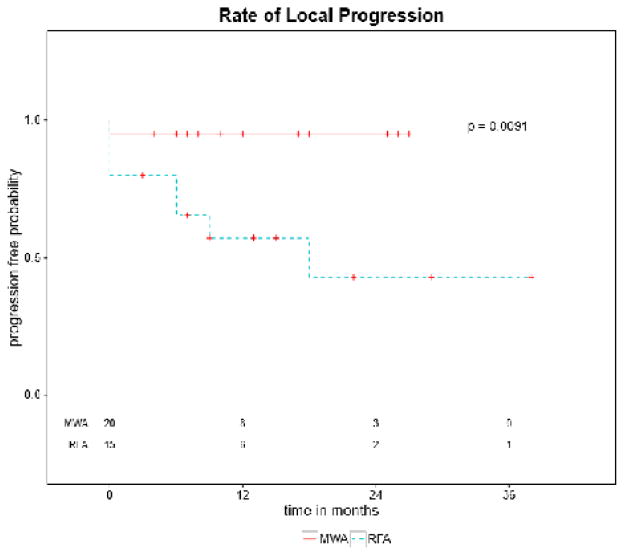

We observed an 80 % complete response rate in the RFA group and a 95% complete response rate in the MWA group (p value <0.29) on the initial post procedure imaging. Due to patient’s accessibility to the tertiary care center and differences in outside ordering provider preferences initial imaging was conducted at 1 month (17), 2 months (9), or 3 months (9). Median time to initial post procedure imaging was 1.8 months. All those in the RFA group where a complete response was not observed had initial imaging at 1 month. The single subject in the MWA group with a partial response was imaged at 3 months post procedure. All four aforementioned events were analyzed as time zero on Kaplan Meier curve and, therefore, difference in follow up imaging did not effect the overall statistical analysis with respect to longitudinal local recurrence. On Kaplan Meier analysis, events were defined as either an incomplete initial response (partial response or stable disease) or local progression on subsequent imaging. Subjects who were lost to follow up after initial imaging, transplanted, or received alternate therapy in the area of interest prior to documented local progression were censored at those time points, with prior data included (Figure 6). Those who were lost to follow up prior to initial imaging were excluded from the study and therefore not included in the analysis. There were 7 total events (3 non-CR and 4 local progressions) in the RFA group and 1 event (1 non-CR) in the MWA group. (p value 0.0091). The remaining 12 subjects with complete response in the RFA group were followed for a median of 18 months. Local progression was observed at 6, 6, 9, and 18 months in four RFA group subjects. Mean time to local progression in the RFA group was 10.5 months. Two subjects received alternate treatment for multifocal disease (29 and 38 months). The remaining 19 subjects in the MWA group with complete response were followed for a median of 14 months in which there were no cases of local progression. Four subjects in the MWA group received alternate treatment for field progression with multifocal disease (5, 10, 10, and 10 months).

Figure 6.

Kaplan Meier curve demonstrates local progression over time in the MWA group and the RFA group. There were three incomplete initial responses within the RFA group and 1 incomplete initial response in the MWA group. These are plotted at time point zero. The curves denote rates of local progression with a statistically significant difference between the MWA group vs the RFA group (p= 0.0091).

Univariate Analysis

None of the covariates demonstrated statistically significant hazard ratios.

Discussion

There are level 1B and level 2 recommendations by both EASL and AASLD respectively for the use of RFA in patients with very early and early stage HCC who are unfit for surgery (4, 5). A recent meta-analysis of over 16,000 patients from 6 different countries demonstrated comparable overall and disease free survival in those treated with RFA compared with hepatic resection (HR) in tumors <2 cm further illustrating its utility as a definitive therapy. Those treated with RFA had lower overall complication rates irrespective of tumor size (13). Despite increasing usage, there are no societal recommendations by the EASL and AASLD for the utilization of microwave due to insufficient evidence (4, 5). Several retrospective studies and meta-analyses show trends which suggest that MWA as a monotherapy may provide benefit over RFA in the treatment of larger tumors (7, 14), but prospective data is unavailable (15).

EASL and the AASLD provide level 1A and level 1 recommendations, respectively, for the use of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) to treat multinodular HCC without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread in patients with BCLC stage B disease (4, 5). Randomized controlled data has suggested reduced toxicity and with DEB-TACE compared with conventional TACE in Child Pugh B patients with advanced or recurrent disease (16). Transarterial bland embolization (TAE) is not currently recommended (5) despite large scale retrospective data that suggests comparable efficacy to TACE (17, 18). Furthermore, a recent single blind randomized controlled trial by Brown et al. further demonstrated equality between TAE and TACE with regard to RECEIST response, adverse events, and overall survival in HCC patients (19). Therefore, differences in selected embolic are more representative of clinical practice likely without significant confounding.

RFA with neoadjuvant TACE is more effective than RFA alone in the treatment of tumors >3 cm (20, 21). Malluccio and Elnekave et al demonstrated no difference in those treated with RFA plus TAE versus HR in HCC lesions < 7 cm (22, 23) with respect to disease free survival, recurrence rates, and overall survival. There are small studies which suggest superiority of MWA + TACE compared with TACE alone (24).

This single-center series showed that microwave ablation was comparable to RFA in initial response and local recurrence in the treatment of early stage HCC. Although the study was not designed to show superiority and admittedly limited by its retrospective nature and heterogeneous population, there was a trend towards greater durability of response in the MWA group defined by those who maintained target lesion CR throughout the study (p 0.0091). Virk et al retrospectively demonstrated similar marginally superior results with respect to initial response and local recurrence in those treated with MWA ablation and neoadjuvant TACE (25). Ginsburg et al showed comparable initial local response and progression free survival in their retrospectively analyzed RFA/TACE and MWA/TACE cohorts (26). Both studies reinforce our central hypothesis that MWA is at least as effective as RFA and should be given credence in the national guidelines. In our cohort a longer durability of response favored MWA group, given the longitudinal difference in outcomes between the studies, the data can be further analyzed in future systematic review as more results emerge.

Age, gender, etiology of cirrhosis, MELD, lesion size, treatment history, and embolization selection were similar in both groups. While the CPS was similar in both groups, nearly half of the subjects receiving MWA had Child B status and did not develop worsening liver function after treatment. In addition, a higher number of lesions were in contact with a blood vessel in the MWA group, which did not decrease its success rate (27). Complication rates and adverse events were similar between both groups. The use of neoadjuvant embolization in the form of TAE or TACE was similar in both groups (p 0.50) and was not associated with difference in outcome. These results indicate that although MWA subjects tended to have inferior hepatic function with more challenging anatomic factors, there was no decreased efficacy. Of note, no BCLC stage B subjects were included in the cohort. This is likely due to preference for Yttrium 90 or embolic agent alone upon discussion of these cases in multidisciplinary conference.

This study has several limitations. Our small sample size did not approach the estimated 150 subjects necessary to detect a statistically significant difference in initial response. Also, due to this small sample size only a univariate analysis was able to be conducted. The retrospective design of the study and the use of institutional historic comparisons in the RFA group in the setting of a highly variable subject substrate make comparison of RFA and MWA groups of limited statistical value. Three out of the 4 RFA subjects who demonstrated local progression, progressed within the first year (6 – 9 months). This rate is higher than in some published cohorts treated with RFA and neoadjuvant embolization (21). There was greater longitudinal censorship in the MWA group with comparison to the RFA group owing to 2 unrelated deaths, 1 death due to rapidly progressive cirrhosis, and 5 transplants versus 2 transplants in the RFA group. Surveillance imaging and protocols were recommended but not standardized in this retrospective cohort. Institutional experience may have improved given the temporal distribution of cases which may have accounted for differences in outcomes. The choice of embolic agents, although not statistically different, was admittedly was not a randomized variable. Though these limitations exist, these preliminary results create a basis for prospective studies given the sparsity of this topic in the literature.

Conclusion

Neoadjuvant transarterial bland or drug eluting bead embolization with subsequent microwave or radiofrequency ablation have similar outcomes and safety profiles in the treatment of very early and early HCC. MWA provided more durable disease control in this study, however, prospective data remains necessary to evaluate superiority of either modality.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was partly supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR001427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

All research was approved under the institutional IRB and conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study who were actively being followed. All others did not require consent per IRB requirements.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Beau Toskich became a consultant for Neuwave Medical subsequent to the collection and analysis of this data. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lindsay M. Thornton, PGY-4, Radiology Resident, Department of Radiology, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Rd, G358, Gainesville, Florida 32610, (201) 274-4021.

Roniel Cabrera, Associate Professor of Medicine, Director of Hepatology, Section of Hepatobiliary Diseases, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Road M440 PO Box 100277, Gainesville, FL 32606.

Jehan Shah, PGY-3 Radiology Resident, Department of Radiology, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Rd, G358, Gainesville, Florida 32610.

Melissa Kapp, Nurse Practitioner, Department of Transplant Surgery, University of Florida at Shands, 1600 SW Archer Road, Gainesville, FL 32610.

Michael Lazarowicz, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Road G358, Gainesville, FL 32610.

Jeff Vogel, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Road G358, Gainesville, FL 32610.

Beau Toskich, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Road G358, Gainesville, FL 32606.

References

- 1.Altekruse SF, Henley SJ, Cucinelli JE, McGlynn KA. Changing hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and liver cancer mortality rates in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(4):542–53. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirk A. Textbook of organ transplantation. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabrera R, Dhanasekaran R, Caridi J, Clark V, Morelli G, Soldevila-Pico C, et al. Impact of transarterial therapy in hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma on long-term outcomes after liver transplantation. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35(4):345–50. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31821631f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruix J, Sherman M Practice Guidelines Committee AeAftSoLD. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1208–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liver EAFTSOT, Cancer EOFRATO. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56(4):908–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singla S, Hochwald SN, Kuvshinoff B. Evolving ablative therapies for hepatic malignancy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:230174. doi: 10.1155/2014/230174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang P, Yu J, Lu MD, Dong BW, Yu XL, Zhou XD, et al. Practice guidelines for ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation for hepatic malignancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(33):5430–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright AS, Sampson LA, Warner TF, Mahvi DM, Lee FT. Radiofrequency versus microwave ablation in a hepatic porcine model. Radiology. 2005;236(1):132–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361031249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He N, Wang W, Ji Z, Li C, Huang B. Microwave ablation: An experimental comparative study on internally cooled antenna versus non-internally cooled antenna in liver models. Acad Radiol. 2010;17(7):894–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poggi G, Tosoratti N, Montagna B, Picchi C. Microwave ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(25):2578–89. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i25.2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boas FE, Do B, Louie JD, Kothary N, Hwang GL, Kuo WT, et al. Optimal imaging surveillance schedules after liver-directed therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(1):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Q, Kobayashi S, Ye X, Meng X. Comparison of hepatic resection and radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of 16,103 patients. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7252. doi: 10.1038/srep07252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Facciorusso A, Di Maso M, Muscatiello N. Microwave ablation versus radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2016;32(3):339–44. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2015.1127434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poulou LS, Botsa E, Thanou I, Ziakas PD, Thanos L. Percutaneous microwave ablation vs radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(8):1054–63. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i8.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lammer J, Malagari K, Vogl T, Pilleul F, Denys A, Watkinson A, et al. Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33(1):41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kluger MD, Halazun KJ, Barroso RT, Fox AN, Olsen SK, Madoff DC, et al. Bland embolization versus chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma before transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(5):536–43. doi: 10.1002/lt.23846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massarweh NN, Davila JA, El-Serag HB, Duan Z, Temple S, May S, et al. Transarterial bland versus chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: rethinking a gold standard. J Surg Res. 2016;200(2):552–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown KT, Do RK, Gonen M, Covey AM, Getrajdman GI, Sofocleous CT, et al. Randomized Trial of Hepatic Artery Embolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Doxorubicin-Eluting Microspheres Compared With Embolization With Microspheres Alone. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(17):2046–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0821. Epub 2016/02/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng ZW, Zhang YJ, Chen MS, Xu L, Liang HH, Lin XJ, et al. Radiofrequency ablation with or without transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(4):426–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.9936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu Z, Wen F, Guo Q, Liang H, Mao X, Sun H. Radiofrequency ablation plus chemoembolization versus radiofrequency ablation alone for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(2):187–94. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835a0a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elnekave E, Erinjeri JP, Brown KT, Thornton RH, Petre EN, Maybody M, et al. Long-term outcomes comparing surgery to embolization-ablation for treatment of solitary HCC<7 cm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(9):2881–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2961-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maluccio M, Covey AM, Gandhi R, Gonen M, Getrajdman GI, Brody LA, et al. Comparison of survival rates after bland arterial embolization and ablation versus surgical resection for treating solitary hepatocellular carcinoma up to 7 cm. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16(7):955–61. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000161377.33557.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu LF, Sun HL, Chen YT, Ni JY, Chen D, Luo JH, et al. Large primary hepatocellular carcinoma: transarterial chemoembolization monotherapy versus combined transarterial chemoembolization-percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(3):456–63. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Virk J, Dayan E, Cohen SL, Kim E, Patel RS, Nowakowski SF, Lookstein RA, Fishman RA. Comparison of microwave vs. radiofrequency ablation of HCC when combined with DEB-TACE: safety and mid-term efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:S33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2013.12.079. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginsburg M, Zivin SP, Wroblewski K, Doshi T, Vasnani RJ, Van Ha TG. Comparison of combination therapies in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: transarterial chemoembolization with radiofrequency ablation versus microwave ablation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(3):330–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brace CL. Microwave ablation technology: what every user should know. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2009;38(2):61–7. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]