Abstract

Introduction

Previous studies have shown that the arcuate fasciculus has a leftward asymmetry in right-handers that could be correlated with the language lateralisation defined by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nonetheless, information about the asymmetry of the other fibres that constitute the dorsal language pathway is scarce.

Objectives

This study investigated the asymmetry of the white-matter tracts involved in the dorsal language pathway through the diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) technique, in relation to language hemispheric dominance determined by task-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Methods

We selected 11 patients (10 right-handed) who had been studied with task-dependent fMRI for language areas and DTI and who had no language impairment or structural abnormalities that could compromise magnetic resonance tractography of the fibres involved in the dorsal language pathway. Laterality indices (LI) for fMRI and for the volumes of each tract were calculated.

Results

In fMRI, all the right-handers had left hemispheric lateralisation, and the ambidextrous subject presented right hemispheric dominance. The arcuate fasciculus LI was strongly correlated with fMRI LI (r = 0.739, p = 0.009), presenting the same lateralisation of fMRI in seven subjects (including the right hemispheric dominant). It was not asymmetric in three cases and had opposite lateralisation in one case. The other tracts presented predominance for rightward lateralisation, especially superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) II/III (nine subjects), but their LI did not correlate (directly or inversely) with fMRI LI.

Conclusion

The fibres that constitute the dorsal language pathway have an asymmetric distribution in the cerebral hemispheres. Only the asymmetry of the arcuate fasciculus is correlated with fMRI language lateralisation.

Keywords: Arcuate fasciculus, superior longitudinal fasciculus, Geshwind, Wernicke, Broca, laterality index

Introduction

Human language is a very complex function that involves multiple brain cortical areas and white-matter tracts connecting them.1 The areas of major importance have been recognised for many years. Broca is located in the opercular inferior frontal gyrus and is the motor speech centre.2 Wernicke is the sensory centre for language and is located in the posterior regions of the superior and middle temporal gyri.3 Geschwind is located in the inferior parietal lobe (supramarginal and angular gyrus), where the speech ideation processes occur.4 Contrary to what this anatomical description may suggest, these eloquent areas present high interindividual variability.5

The dorsal language pathway is part of the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) and connects these three cortical areas.1 Studies on diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) have successfully demonstrated these tracts: the arcuate fasciculus (AF) or direct segment of AF connects the inferior frontal gyrus and posterior superior and middle temporal gyri; SLF II and III connect the middle and inferior frontal gyri with angular and supramarginal gyri, respectively (also designated as anterior indirect segment of AF); and the temporo-parietal inferior parietal lobe connection of SLF (TP-IPL) connects the supramarginal and angular gyri with posterior temporal regions (also known as posterior indirect segment of AF).6–8

The processes of language tend to be asymmetrically distributed in the cerebral hemispheres,9 generally presenting a leftward dominance that can be reliably documented through blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) task functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).10

Studies using MRI tractography have documented the extension of these asymmetries to the dorsal language pathways that connect the language frontal, temporal and parietal areas. They have also shown that AF has a preferable leftward lateralisation in right-handers11–22 that is directly correlated with left hemispheric lateralisation on fMRI.11–17,22 Subjects with rightward fMRI language hemispheric lateralisation have a more unpredictable AF lateralisation.12,14

The objective of this work was to investigate the asymmetry of the white-matter tracts involved in the dorsal language pathway through the DTI technique in relation to language hemispheric dominance determined by BOLD task-dependent fMRI.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study was conducted retrospectively. Adult patients were selected by searching our institution’s picture archiving and communications system for studies with language task-dependent BOLD fMRI and DTI acquisitions. We excluded patients with language impairment or brain structural abnormalities in the presumed topography of the white-matter tracts of the dorsal language pathway. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the institution.

Imaging acquisitions

MRI data sets were acquired in an Achieva® 1.5 T magnet (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) using eight-channel coil and SENSE® technology. For anatomical reference, we used a 3D-volume fast field echo (FFE) T1-weighted (repetition time [TR]/echo time [TE] 7.3/3.3 ms, acquisition matrix 284 mm ×239 mm, field of view [FOV] 256 mm, 0.46 mm ×0.46 mm × 0.9 mm voxel, flip angle 8°, no inter-slice gap), routinely performed in these studies. The acquisition time was seven minutes.

BOLD fMRI

The acquisition consisted of a T2*-weighted gradient echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence, sensitive to BOLD contrast (TR/TE 3000/50 ms; acquisition matrix 96 mm × 94 mm; FOV 230 mm, slice thickness 4 mm; intersection gap 0.4 mm). Each volume had 30 slices in a total of 120 volumes. The acquisition time was six minutes.

fMRI paradigms

Two different auditory language fMRI paradigms were presented to stimulate language areas: association and fluency. They were block-design paradigms consisting of alternating blocks of six rest and six active conditions, lasting for 30 seconds each. In the association paradigm, patients were told to identify the concept/object referred to in the phrase that they listened to (e.g. ‘cut the meat with…’). In the fluency paradigm, in the active blocks, patients were told to think about words that started with a specific letter or that corresponded to a referred semantic category. In both paradigms, the patients listened to ambient music during the rest blocks.

fMRI data analysis

This was performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping v12 (SPM12; Wellcome Department of Imaging Neurosciense, University College London; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) implemented in Matlab v7.13 (The Mathworks, Sherborn, MA). Imaging data sets were first realigned and motion corrected before being normalised to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template and posteriorly smoothed with a 8 mm × 8 mm × 8 mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian filter. These images underwent first-level analysis where the six rest–active blocks were incorporated in the design matrix and a high-pass filter of 120 s was defined. For each subject and each paradigm, the number of significant activated voxels for t-contrast (p < 0.05, with family-wise error correction) was counted in the regions of interest (ROIs) of each brain hemisphere. These ROIs were defined using the atlas provided by the SPM12 software and incorporated the following gyri: inferior frontal, supramarginal, angular and superior/middle temporal.1,23 The laterality index (LI) was defined using the following formula LI = (L–R)/(L + R), where L and R represented the amount of activated voxels in the selected ROIs for left and right hemispheres, respectively. A LI ≥ +0.1 was considered as left hemispheric lateralisation and a LI ≤ −0.1 was considered as right lateralisation. The LI values between –0.1 and +0.1 were considered as bilateral lateralisation or language co-dominance.24

MRI tractography

DTI acquisition comprised diffusion weighted spin echo EPI (TR/TE 6635.2/86.3 ms; acquisition matrix 112 × 110; FOV 224 mm; slice thickness 2.6 mm without intersection gap). A total of 50 slices were obtained with a b factor of 0 and 1000 s/mm2. Diffusion weighting images were taken with 64 directions. The acquisition time was five minutes and 37 seconds.

For the pre-processing of the diffusion-weighted images, the data sets were corrected for eddy current distortion using the eddy tool in Functional Brain Magnetic Imaging of the Brain Software Library (FSL).25 DTI was calculated in DSI Studio (http://dsi-studio.labsolver.org) software with a generalised deterministic tracking algorithm that uses quantitative anisotropy as the termination index.26 All the generated white-matter tracts terminated at fractional anisotropy (FA) values <0.2 or an angle threshold >50°. Fibre tracking was also done in DSI Studio. First, tractography was performed by one of the investigators and posteriorly reviewed together with the second investigator. Both had experience in DTI and were blinded to clinical and fMRI data. The investigators achieved consensus on every tract. The fibres were reconstructed according to the work of Kamali et al.,7 where a two ROI approach is used to track AF, SLF II/III and SLF TP-IPL. The high-resolution T1 and FA reconstruction on greyscale were used for anatomical correlation. Any aberrant fibres were removed manually. After fibre tracking, each tract was computed separately, and their volume and mean FA were obtained. The DTI LI was calculated for each tract with the following formula: LI = (L tract–R tract)/(L tract + R tract). An LI of ≥ +0.1 was considered as left lateralisation; a LI ≤ –0.1 was considered as right lateralisation. LI values between –0.1 and +0.1 were considered bilateral lateralisation.14,23

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac v20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to evaluate the correlation between fMRI LI and DTI LI, and a Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the differences between the non-normal distributed variable number of activated voxels between association and fluency paradigms. p-Values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Subjects

We found 24 subjects who had performed language fMRI and DTI acquisitions. Twelve were excluded because they had structural brain abnormalities that did not allow correct DTI tractography of dorsal language pathways in both hemispheres. One subject was excluded because there were no activated voxels in defined ROIs for fMRI. The final number of subjects in the cohort was 11: 10 right-handers and one ambidextrous, eight of whom were female (male:female ratio of 1:2.67) with a mean age of 34.5 ± 11.9 years. Every subject had performed MRI studies in the clinical context of epilepsy. Five patients had a normal structural MRI (three underwent surgery after stereo-electroencephalographic [SEEG] study reporting histologic findings of gliosis in two cases and focal cortical dysplasia type IIa in one), three had MRI findings compatible with focal cortical dysplasia (FCD), one had a cavernous malformation, one had encephalomalacia and one had multifocal anaplastic astrocytoma. The data are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort.

| Patient | Sex | Age (years) | Handedness | MRI | Location | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | m | 40 | Right | FCD | Left middle frontal gyrus | – |

| 2 | f | 36 | Right | Normal | – | – |

| 3 | f | 20 | Right | FCD | Left operculo-insular | – |

| 4 | m | 38 | Right | Cavernous malformation | Left caudate nucleus | – |

| 5 | f | 15 | Right | Normal | Left planum temporale | DCF IIa |

| 6 | f | 46 | Right | Normal | Left frontal | Gliosis |

| 7 | f | 29 | Right | Normal | Right temporal lobe | Gliosis |

| 8 | f | 25 | Right | FCD | Left parietal lobe | – |

| 9 | f | 28 | Right | Normal | – | – |

| 10 | f | 46 | Ambidextrous | Encephalomalacia | Left fronto-insular region | – |

| 11 | m | 57 | Right | Neoplasm | Left: SM gyrus, TP and pulvinar | Anaplastic Astrocytoma |

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; FCD: focal cortical dysplasia.

Functional MRI

The mean number of activated voxels was 1396 ± 1180 on the left hemisphere and 351 ± 366 on the right. The fMRI LI showed a leftward lateralisation in all the right-handed subjects (90.9% of the total number) and a rightward lateralisation in the ambidextrous subject. Only one subject had a LI close to the threshold for lateralisation (LI = +0.12); the other subjects had a LI of ≥0.31 (absolute values). The association paradigm produced more activated voxels than the fluency paradigm (968 ± 885 vs. 429 ± 365 on the left hemisphere, p = 0.178; 244 ± 272 vs. 107 ± 219 on the right hemisphere, p = 0.060). The number of activated voxels for the ROI in each hemisphere and the fMRI LI are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Activated voxels on fMRI and LI. Volumes of white matter tracts of the dorsal language pathways in each subject.

| Patient | fMRI |

AF volumes (mm3) |

SLF II/II (anterior indirect segment) volumes (mm3) |

SLF TP-IPL (post indirect segment) volumes (mm3) |

Total tracts volumes (mm3) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV left | AV right | LI | Left | Right | LI | Left | Right | LI | Left | Right | LI | Left | Right | LI | |

| 1 | 3860 | 502 | +0.77 | 4076.8 | 3047.2 | +0.14 | 1050.4 | 4732.0 | −0.64 | 2360.8 | 1705.6 | +0.16 | 7488.0 | 9484.8 | −0.12 |

| 2 | 473 | 372 | +0.12 | 1227.2 | 2371.2 | −0.32 | 2683.2 | 5657.6 | −0.36 | 748.8 | 967.2 | −0.13 | 4659.2 | 8996.0 | −0.32 |

| 3 | 1940 | 85 | +0.92 | 6312.8 | 1809.6 | +0.55 | 3140.8 | 4960.8 | −0.22 | 4524.0 | 1726.4 | +0.45 | 13,977.6 | 8496.8 | +0.24 |

| 4 | 905 | 72 | +0.85 | 6260.8 | 5917.6 | +0.03 | 3608.8 | 7092.8 | −0.33 | 2256.8 | 3099.2 | −0.16 | 12,126.4 | 16,109.6 | −0.14 |

| 5 | 152 | 0 | +1.00 | 3088.8 | 0.0 | +1.00 | 2277.6 | 4004.0 | −0.27 | 4305.6 | 4877.6 | −0.06 | 9672.0 | 8881.6 | +0.04 |

| 6 | 1107 | 86 | +0.86 | 1404.0 | 811.2 | +0.27 | 1102.4 | 3338.4 | −0.50 | 2267.2 | 2319.2 | −0.01 | 4773.6 | 6468.8 | −0.15 |

| 7 | 1405 | 736 | +0.31 | 3026.4 | 2839.2 | +0.03 | 4482.4 | 2163.2 | +0.35 | 2475.2 | 1279.2 | +0.32 | 9984.0 | 6281.6 | +0.23 |

| 8 | 1084 | 39 | +0.93 | 3296.8 | 2672.8 | +0.10 | 1882.4 | 1768.0 | +0.03 | 3099.2 | 4357.6 | −0.17 | 8278.4 | 8798.4 | −0.03 |

| 9 | 462 | 39 | +0.84 | 4056.0 | 4690.4 | −0.07 | 644.8 | 956.8 | −0.19 | 2215.2 | 2693.6 | −0.10 | 6916.0 | 8340.8 | −0.09 |

| 10 | 477 | 904 | −0.31 | 0.0 | 2901.6 | −1.00 | 0.0 | 5834.4 | −1.00 | 1851.2 | 1092.0 | +0.26 | 1851.2 | 9828.0 | −0.68 |

| 11 | 3495 | 1026 | +0.55 | 8278.4 | 811.2 | +0.82 | 3432.0 | 5605.6 | −0.24 | 1133.6 | 1435.2 | −0.12 | 12,844.0 | 7852.0 | +0.24 |

| Mean | 1396 ± 1180 | 351 ± 366 | 4102.8 ± 2130.0 | 2787.2 ± 1498.5 | 2430.5 ± 1198.0 | 4192.1 ± 1834.0 | 2476.1 ± 1098.7 | 2323.0 ± 1256.8 | 8415.5 ± 3592.3 | 9048.9 ± 2473.5 | |||||

fMRI: functional magnetic resonance imaging; LI: lateralising indices; AF: arcuate fasciculus; SLF: superior longitudinal fasciculus; SLF TP-IPL: temporo-parietal inferior parietal lobe connection of SLF.

Diffusion tractography

AF volumes were asymmetric between the two hemispheres in eight (72.7%) subjects. They had a leftward lateralisation in six (54.5%) subjects and a rightward lateralisation in two (18.2%). The AF could not be traced in one subject on the left side and in another on the right side. The mean volume and FA of the traced AF were 4102.8 ± 2130.0 mm3 and 0.433, respectively, on the left side and 2787.2 ± 1498.5 mm3 and 0.418 in the right.

SLF II/III volumes were asymmetric in 10 (90.9%) subjects. They had a rightward lateralisation in nine (81.8%) subjects and a leftward lateralisation in one (9.1%). The mean volume and FA on the left SLF II/III were 2430.5 ± 1198.0 mm3 and 0.389, respectively, and 4192.1 ± 1834.0 mm3 and 0.395 on the right side. These tracts could be traced in all subjects.

SLF TP-IPL volumes were asymmetric in nine (90.9%) subjects, with a rightward lateralisation in five (45.4%) subjects. The subjects with leftward lateralisation had higher degree of asymmetry, presenting LI equal to or higher than in the subjects with rightward lateralisation. The mean volume and FA on the left SLF TP-IPL were 2476.1 ± 1098.7 mm3 and 0.388, respectively, and 2323.0 ± 1256.8 mm3 and 0.388 on the right side. These tracts could be traced in all subjects.

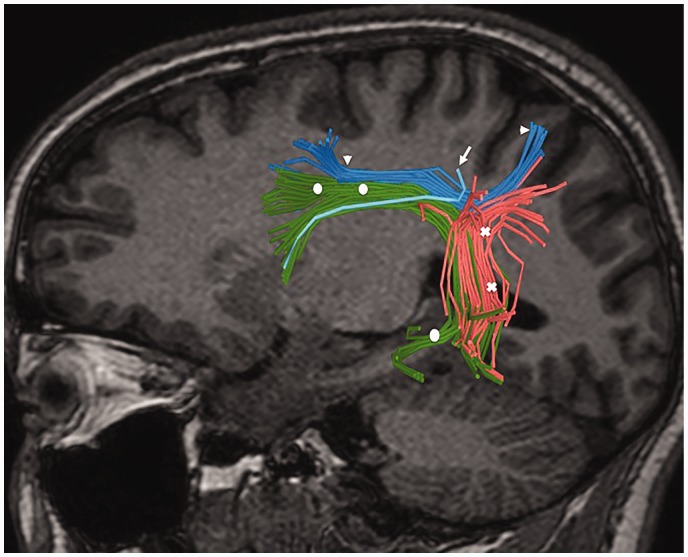

Considering all the dorsal language pathways, the lateralisation dominance was on the left side in two (18.2%) subjects, on the right side in five (45.4%) and bilateral in four (36.4%). The total volume and mean FA of the left side tracts were 8415.5 ± 3592.3 mm3 and 0.409, respectively, and 9048.9 ± 2473.5 mm3 and 0.400 on the right side. The volume and FA values for each subject are shown in Table 2. Figures 1 and 2 represent tridimensional reconstructions of the white-matter tracts after MR tractography.

Figure 1.

Example of tridimensional reconstructions of the dorsal language pathway tracts in the left hemisphere (circles: arcuate fasciculus [AF], arrowheads: superior longitudinal fasciculus [SLF] II; arrow: SLF III; crosses: temporo-parietal inferior parietal lobe connection of SLF [SLF TP-IPL]).

Figure 2.

Example of bilateral AF tridimensional reconstructions in a single subject (L: left; R: right).

Correlation between the fMRI LI and the dorsal language pathway tract volumes LI

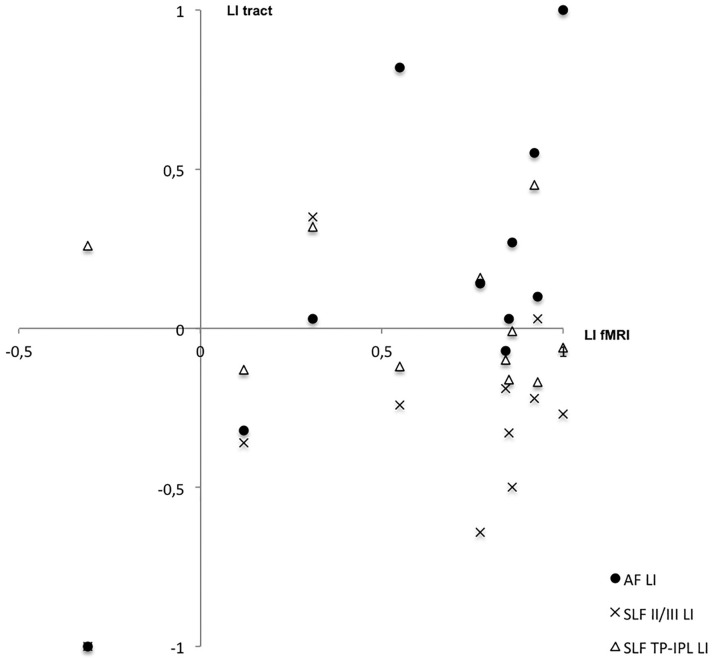

Figure 3 shows the correlation between the LI of the fMRI and dorsal language pathway tracts volumes.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the laterality indices of the functional magnetic resonance imaging and of the AF, SLF II/III and SF TP-IPL.

AF LI had the same side lateralisation that fMRI LI in seven (63.4%) subjects, including the only with rightward lateralisation on fMRI. In three (27.3%) subjects, the AF had bilateral lateralisation, and in one (9.1%) subject, the lateralisation of AF was on the opposite side of the fMRI. Statistical analysis revealed a strong correlation between the fMRI and tractography LI (r = 0.739, p = 0.009).

SLF II/III LI had the same side lateralisation that fMRI in two (18.2%) patients. In eight (72.7%) subjects, the lateralisation was on the opposite side, and in one (9.1%), it was bilateral. The indices did not present a significant correlation.

SLF TP-IPL dominance was correlated with fMRI in three (27.3%) subjects. In six (54.5%) subjects, the tract was dominant on the opposite side, and in two (18.2%) subjects, there was no tract asymmetry. The indices did not present a significant correlation.

Discussion

Our work confirms the knowledge that the white-matter tracts of dorsal language are asymmetrically distributed between the two cerebral hemispheres. As described in previous works, the AF demonstrated a leftward asymmetry in most left lateralised language subjects.11–17,22 We also found a rightward lateralisation of AF in the unique subject with right language dominance, a finding that contributed to the strong correlation of the two LIs. The level of concordance between fMRI and AF LIs (seven patients; 63.4%) suggests a weaker correlation than the one that Pearson’s test demonstrated, but it is important to have in mind that Pearson’s test does not take into account the artificially defined threshold for laterality indices (–0.1 and +0.1).

We made a careful selection of the patients analysing structural MRI and FA coloured maps after DTI reconstruction in order to avoid potential bias originated from structural abnormalities that could compromise the quality of the data. In the case that fMRI and AF LI correlated perfectly (+1; +1), the subject had MRI negative epilepsy and underwent SEEG exploration and surgery (FCD type IIa in the left planum temporale). The only case where fMRI and AF had opposite lateralisation was in a patient with negative MRI epilepsy who underwent SEEG (no surgery performed).

The fibres connecting the inferior parietal lobule to the frontal and temporal language areas tended to have rightward lateralisation without any correlation (directly or inversely) with fMRI LI. This rightward lateralisation was more evident in the SLF II/III tracts. These fibres along with inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus are believed to have an essential role in integration of visual and spatial information, a function that is lateralised to the right cerebral hemisphere.18

On MRI tractography, the methods for tracing AF (or AF direct segment) are well described in previous works.7,8 The SLF II and III or anterior indirect segment and the SLF TP-IPL or posterior indirect segment were more challenging to trace because the fibres originating in the inferior parietal lobule, especially in the angular gyrus, have greater anatomical variability.6 Our consensus approach on this matter granted a homogenous methodology for every patient.

We do not believe that phenomena of neuroplasticity in language areas could have compromised the data because every patient had plausible dominance areas according to handedness, and all but one had fMRI LI far from threshold values. In that particular case (LI = +0.12), the MRI was normal.

There are several issues related to the cohort that we would like to address. First, with regard to the relatively heterogeneous nature, all the subjects were studied in the context of epilepsy, but they had different associated aetiologies. In order to minimise potential bias associated with this, we excluded subjects with language impairment and structural abnormalities in the presumable areas involved in language processes. Second, in terms of the size of the cohort, despite being a limited sample, it was able to demonstrate a correlation with statistical impact. The concordance with previous studies also adds confidence to the results obtained. Third, with regard to the lack of rightward language lateralisation subjects, this limitation is common to other works in this field. Larger cohorts are needed to understand if there is any correlation between AF volumes and language hemispheric dominance. Other limitations include that this was a retrospective study and that there were no histological data for any of the cases.

Conclusion

Our findings are in line with previous works, where the asymmetry of AF is correlated with fMRI language lateralisation. We also confirmed that the fibres connecting frontal and inferior parietal language areas have a tendency for rightward asymmetry.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Dias Costa for his kind revision of the work.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Fujii M, Maesawa S, Ishiai S, et al. Neural basis of language: an overview of an evolving model. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2016; 56: 379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Znamenskiy P, Zador AM. Corticostriatal neurons in auditory cortex drive decisions during auditory discrimination. Nature 2013; 497: 482–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wernicke C. Der aphasische Symptomencomplex: Eine psychologische Studie auf anatomischer Basis, Breslau: Cohn and Weigert, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geschwind N. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. I. Brain 1965; 88: 237–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández G, Specht K, Weis S, et al. Intrasubject reproducability of presurgical language lateralization and mapping using fMRI. Neurol 2003; 60: 969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yagmurlu K, Middlebrooks EH, Tanriover N, et al. Fiber tracts of the dorsal language stream in the human brain. J Neurosurg 2016; 124: 1396–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamali A, Flanders A, Brody J, et al. Tracing superior longitudinal fasciculus connectivity in the human brain using high resolution diffusion tensor tractography. Brain Struct Funct 2014; 219: 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catani M, Jones DK, Ffytche DH. Perisylvian language networks of the human brain. Ann Neurol 2005; 57: 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smits M, Jiskoot LC, Papma JM. White matter tracts of speech and language. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2014; 35: 504–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer PR, Reitsma JB, Houweling BM, et al. Can fMRI safely replace the Wada test for preoperative assessment of language lateralisation? A meta-analysis and systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takaya S, Kuperberg GR, Liu H, et al. Asymmetric projections of the arcuate fasciculus to the temporal cortex underlie lateralized language function in the human brain. Front Neuroanat 2015; 9: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Häberling IS, Badzakova-Trajkov G, Corballis MC. Asymmetries of the arcuate fasciculus in monozygotic twins: genetic and nongenetic influences. PLoS One 2013; 8: e52315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Propper RE, O’Donnell LJ, Whalen S, et al. A combined fMRI and DTI examination of functional language lateralization and arcuate fasciculus structure: effects of degree versus direction of hand preference. Brain Cogn 2010; 73: 85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernooij MW, Smits M, Wielopolski PA, et al. Fiber density asymmetry of the arcuate fasciculus in relation to functional hemispheric language lateralization in both right- and left-handed healthy subjects: a combined fMRI and DTI study. Neuroimage 2007; 35: 1064–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glasser MF, Rilling JK. DTI tractography of the human brain’s language pathways. Cereb Cortex 2008; 18: 2471–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nucifora PGP, Verma R, Melhem ER, et al. Leftward asymmetry in relative fiber density of the arcuate fasciculus. Neuroreport 2005; 16: 791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker GJM, Luzzi S, Alexander DC, et al. Lateralization of ventral and dorsal auditory-language pathways in the human brain. Neuroimage 2005; 24: 656–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiebaut de Schotten M, ffytche DH, Bizzi A, et al. Atlasing location, asymmetry and inter-subject variability of white matter tracts in the human brain with MR diffusion tractography. Neuroimage 2011; 54: 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catani M, Allin MPG, Husain M, et al. Symmetries in human brain language pathways correlate with verbal recall. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104: 17163–17168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández-Miranda JC, Wang Y, Pathak S, et al. Asymmetry, connectivity, and segmentation of the arcuate fascicle in the human brain. Brain Struct Funct 2015; 220: 1665–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger K, Yang S, Reisert M, et al. Tractography of association fibers associated with language processing. Clin Neuroradiol 2015; 25: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell HWR, Parker GJM, Alexander DC, et al. Hemispheric asymmetries in language-related pathways: a combined functional MRI and tractography study. Neuroimage 2006; 32: 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sreedharan RM, Menon AC, James JS, et al. Arcuate fasciculus laterality by diffusion tensor imaging correlates with language laterality by functional MRI in preadolescent children. Neuroradiol 2015; 57: 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szaflarski JP, Holland SK, Schmithorst VJ, et al. fMRI study of language lateralization in children and adults. Hum Brain Mapp 2006; 27: 202–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage 2015; 125: 1063–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh FC, Verstynen TD, Wang Y, et al. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. PLoS One 2013; 8: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]