Abstract

Background

Strategies to reduce the likelihood of axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) include application of Z0011 or use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). Indications for ALND differ by treatment plan and nodal pathologic complete response rates following NAC vary by tumor subtype. ALND rates in patients with cT1-2N0 tumors undergoing upfront surgery were compared to those treated with NAC.

Methods

ALND rates among cT1-2N0 breast cancer patients were compared by tumor subtype among women undergoing upfront surgery to NAC. Multivariable analysis controlling for age, cT stage, lymphovascular invasion, and stratified by subtype was performed.

Results

1944 cancers in 1907 women who underwent SLN biopsy +/− ALND were identified (669 upfront breast-conserving surgery [BCS], 1004 upfront mastectomy, 271 NAC). Compared to the NAC group, ALND rates in the BCS group were lower for ER/PR+ HER2− tumors (15% versus 34%, p<.001). ALND rates in the upfront mastectomy group were higher than the NAC group among HER2+ or TN tumors. On multivariable analysis, receipt of NAC compared to upfront BCS remained significantly associated with higher odds of ALND in the ER/PR+, HER2− subtype (HR 3.35, p<.001), while NAC versus upfront mastectomy remained significantly associated with lower odds of ALND in the HER2+ and TN subtypes (HR HER2+ 0.19, p<.001; HR TN 0.25, p=0.007).

Conclusion

ALND rates differ according to surgery type and tumor subtype secondary to differing ALND indications and nodal response to NAC. These factors can be used to personalize treatment planning in order to minimize ALND risk in early-stage breast cancer patients.

Keywords: breast cancer, ALND, axillary lymph node dissection, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, early-stage breast cancer

INTRODUCTION

The avoidance of surgical morbidity and, in particular, lymphedema, is a major goal when managing early-stage breast cancer patients. Axillary treatment decision making among clinically node-negative (cN0) women has become increasingly complex given the differing indications for axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) for women managed with upfront surgery versus those treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). Currently, options to minimize the likelihood of an ALND among cN0 breast cancer patients include application of American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial criteria1,2 in women undergoing upfront breast-conserving surgery (BCS) or the use of NAC to downstage microscopic axillary disease.3–5 Among patients with a cT1-2N0 breast cancer undergoing upfront BCS and planned whole-breast radiation therapy, ALND is warranted for ≥3 positive sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs), whereas for women undergoing upfront mastectomy, ALND remains the standard of care in the presence of any nodal metastasis.6 Following NAC, ALND is performed for any nodal metastasis, regardless of tumor deposit size.6 While NAC is associated with the potential for axillary nodal downstaging, rates of a nodal pathologic complete response (pCR) differ substantially by tumor subtype7–10 and, therefore, the likelihood of minimizing the extent of axillary surgery differs by tumor biology. Given these options, the optimal treatment plan to avoid ALND in early-stage breast cancer patients remains unclear. Herein we compared rates of ALND among a cohort of patients with cT1-2N0 breast cancer undergoing upfront surgery to those treated with NAC to better elucidate optimal strategies by tumor subtype to avoid axillary surgical morbidity.

METHODS

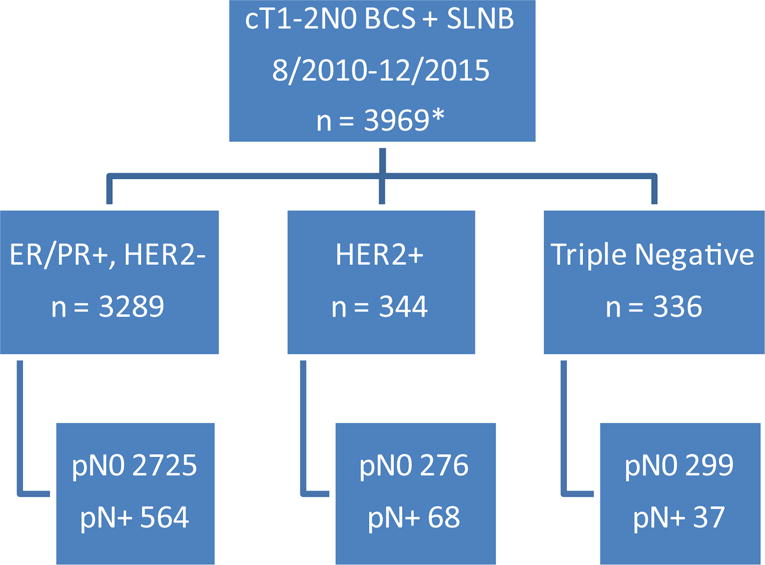

Following Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center institutional review board approval, women with cT1-2N0 breast cancer by physical exam (i.e., no palpable adenopathy) were identified from a prospectively maintained database. Women with a cT1-2N0 tumor meeting ACOSOG Z0011 eligibility criteria undergoing upfront BCS between 8/2010–12/2015 were identified; those found to have a positive SLN comprised the upfront BCS cohort (Fig. 1). Women undergoing upfront mastectomy with a cT1-2N0 tumor from 1/2008–12/2011 comprised the upfront mastectomy group, while women with a cT1-2N0 tumor treated with NAC followed by surgery between 8/2009–5/2016 comprised the NAC group. Patients found to have a positive SLN were chosen for the BCS group to provide a more fair comparison to the NAC group since clinically node-negative, ER positive patients infrequently receive NAC. The cohort inclusion dates differed secondary to changes in clinical practice (application of Z0011) and available clinicopathologic data. Clinical nodal status was defined by physical exam alone; however, some patients underwent axillary imaging with or without a lymph node needle biopsy prior to definitive treatment at the discretion of the treating physician. Patient and tumor characteristics were recorded. ER status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, and HER2 neu status were recorded. For analyses, ER/PR+, HER2+ and ER/PR−, HER2+ groups were combined into one HER2+ cohort secondary to small numbers. Axillary imaging and systemic therapy details were recorded for the NAC cohort. In the upfront BCS cohort, ALND was warranted for ≥3 positive SLNs or gross/clinically suspicious extracapsular extension per surgeon discretion. In the upfront mastectomy cohort, ALND was indicated for any nodal metastasis (micrometastasis or macrometastasis), but not for isolated tumor cells. Following NAC, ALND was indicated for any nodal metastasis, including isolated tumor cells, or failure to identify ≥3 negative SLNs among the cohort of patients with an upfront positive axillary lymph node biopsy. Rates of ALND were compared by subtype among women undergoing upfront BCS or mastectomy to those receiving NAC. Patients with bilateral breast cancer were abstracted as two separate cases.

Fig. 1. Pathologic nodal status by receptor subtype for all cT1-2N0 breast cancer patients undergoing breast-conserving surgery and SLNB from 2010–2015.

*women with unknown receptor status or clinical nodal stage excluded

BCS, breast conserving surgery; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; pN0, pathologically node negative; pN+, pathologically node positive

Continuous variables were summarized using median (min, max) whereas categorical variables were summarized using N (%). Multivariable analysis adjusted for factors determined a priori. In all analyses, we used generalized estimating equations models with exchangeable correlation structure to account for the correlation between multiple observations from a single patient. Likelihood ratio tests were used to test for interactions between treatment received and cancer subtype. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 3.2.5 (R Core Development Team, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

In total 1944 cN0 cancers were identified in 1907 women; 669 in the SLN-positive BCS cohort, 1004 managed with upfront mastectomy, and 271 treated with NAC. 37 women were included with bilateral breast cancer, including 3 patients with 6 tumors who underwent NAC (1 with bilateral ER+, HER2− tumors, 1 with bilateral triple-negative tumors, and 1 patient with differing tumor profiles including 1 triple-negative and 1 ER+, HER2− tumor), while the remainder had upfront surgery (32 women with bilateral mastectomies and 2 women with bilateral BCS). Table 1 compares clinicopathologic features among the 3 treatment groups. Women undergoing NAC were younger, more likely to have cT2 tumors, and more likely to have triple-negative or HER2+ tumors. On final pathology, those who received NAC were less likely to have lymphovascular invasion present and had smaller pathologic tumor size.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinicopathologic features between the upfront surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy cohorts

| Variable | Upfront BCS (n = 669) | NAC (n = 271) | p-value | Upfront mastectomy (n = 1004) | NAC (n = 271) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 58 (30, 92) | 49 (24, 77) | < .001 | 51 (22, 92) | 49 (24, 77) | < .001 |

| cT stage | < .001 | < .001 | ||||

| cT1 | 477 (71.3%) | 28 (10.3%) | 620 (61.8%) | 28 (10.3%) | ||

| cT2 | 192 (28.7%) | 243 (89.7%) | 384 (38.2%) | 243 (89.7%) | ||

| Pathologic tumor size, cm, median (range) | 1.7 (0.1, 5.2) | 0.2 (0, 5.5) | < .001 | 1.6 (0.1, 8.5) | 0.2 (0, 5.5) | < .001 |

| Histology | 0.062 | < .001 | ||||

| Ductal | 605 (90.4%) | 256 (94.5%) | 814 (81.1%) | 256 (94.5%) | ||

| Lobular | 57 (8.5%) | 11 (4.1%) | 171 (17%) | 11 (4.1%) | ||

| Other* | 7 (1%) | 4 (1.5%) | 19 (1.9%) | 4 (1.5%) | ||

| Lymphovascular Invasion present | 392 (58.6%) | 64 (23.6%) | < .001 | 378 (37.6%) | 64 (23.6%) | < .001 |

| ER positive | 614 (91.8%) | 148 (54.6%) | < .001 | 825 (82.2%) | 148 (54.6%) | < .001 |

| PR positive | 556 (83.1%) | 123 (45.4%) | < .001 | 739 (73.6%) | 123 (45.4%) | < .001 |

| HER2+** | 68 (10.2%) | 112 (41.3%) | < .001 | 146 (14.5%) | 112 (41.3%) | < .001 |

| Tumor Subtype* | < .001 | < .001 | ||||

| ER/PR+, HER2− | 564 (84.3%) | 73 (26.9%) | 724 (72.1%) | 73 (26.9%) | ||

| ER−, PR−, HER2+ | 17 (2.5%) | 31 (11.4%) | 44 (4.4%) | 31 (11.4%) | ||

| ER/PR+, HER2+ | 51 (7.6%) | 81 (29.9%) | 102 (10.2%) | 81 (29.9%) | ||

| ER−, PR−, HER2− | 37 (5.5%) | 86 (31.7%) | 126 (12.5%) | 86 (31.7%) |

Other histologies include invasive carcinoma with neuroendocrine features (n=4), metaplastic (n=11), mucinous (n=10), papillary (n=4), and invasive tubular carcinomas (n=1)

HER2 status and overall tumor subtype is missing for 8 (0.8%) women in the mastectomy cohort

BCS, breast-conserving surgery; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; cT1, clinical T1; cT2, clinical T2; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor

Among 271 cN0 women treated with NAC, 114 underwent pre-treatment axillary ultrasound and 229 had an MRI with abnormal nodes identified in 74 and 90, respectively. 71 (26%) NAC patients underwent an axillary lymph node biopsy and 27 (10%) had biopsy-proven nodal metastasis. The majority of women (90%) treated with NAC received an anthracycline and taxane-based regimen, with 10% of women receiving other combination chemotherapy regimens. All women with HER2+ tumors undergoing NAC received anti-HER2 therapy. Eighty-five of 271 women receiving NAC (31%) achieved a pCR in the breast and 45 (17%) had documented treatment effect in the axillary lymph nodes indicating that they had been initially node positive. Overall, 40 (15%) women in the NAC cohort required ALND (35 for a positive SLN and 5 for < 3 SLNs identified), including 13 of the 27 patients with pre-treatment biopsy proven nodal metastases (11 with a positive SLN [3/8 ER−, HER2−; 4/5 ER+, HER2−; 4/14 HER2+ tumors] and 2 for <3 SLNs identified). Among the BCS cohort, all women had a positive SLN and 99 (15%) had indications for a completion ALND (66 for >2 positive SLNs, 33 for extracapsular extension) (p=0.99 compared to NAC group), whereas in the mastectomy group, 354 (35%) women required ALND for a positive SLN (p<.001 compared to NAC group).

Women with ER/PR+, HER2− tumors were less likely to require a completion ALND if treated with upfront BCS compared to NAC (15.1% vs 34.2%, p<.001); this difference was not observed in HER2+ or triple-negative patients. Conversely, among women undergoing upfront mastectomy, those with HER2+ (36.3% versus 8%, p<.001) and triple-negative tumors (25.4% vs 7%, p=0.001) were more likely to require ALND compared to those receiving NAC (Table 2). A significant interaction effect was seen between tumor subtype and treatment type for both the BCS versus NAC cohort (p=0.003) and the mastectomy versus NAC cohort (p=0.006) on multivariable analysis with respect to whether ALND was warranted. On multivariable analysis stratified by cancer subtype and comparing upfront BCS to NAC, receipt of NAC was associated with an increase in risk of ALND among ER/PR+, HER2− tumors (odds ratio [OR] 3.35, p<.001) (Table 3). Sample size was not sufficient to examine this effect among the other subtypes.

Table 2.

Rates of axillary lymph node dissection by tumor subtype and treatment cohort

| Subtype | Upfront BCS n (%) | NAC n (%) | p-value | Upfront mastectomy n (%) | NAC n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER/PR+, HER2− | 85/564 (15.1%) | 25/73 (34.2%) | < .001 | 268/724 (37%) | 25/73 (34.2%) | 0.62 |

| HER2+ | 9/68 (13.2%) | 9/112 (8%) | 0.26 | 53/146 (36.3%) | 9/112 (8%) | < .001 |

| ER−, PR−, HER2− | 5/37 (13.5%) | 6/86 (7%) | 0.26 | 32/126 (25.4%) | 6/86 (7%) | 0.001 |

BCS, breast-conserving surgery; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis assessing likelihood of axillary lymph node dissection by tumor subtype and treatment cohort: upfront BCS versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy

| Variable | Upfront BCS vs NAC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER/PR+, HER2− | HER2+* | Triple negative* | ||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| NAC | 3.35 (1.76‒6.39) | < .001 | NA | NA |

| Age | 1 (0.98‒1.02) | 0.93 | NA | NA |

| LVI | 1.82 (1.14‒2.9) | 0.01 | NA | NA |

| cT2 (vs cT1) | 1.11 (0.68‒1.79) | 0.68 | NA | NA |

Insufficient event numbers to perform multivariable analysis for HER2+ and triple-negative tumors

BCS, breast-conserving surgery; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NA, not applicable; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; cT1, clinical T1; cT2, clinical T2

On multivariable analysis stratified by subtype and comparing upfront mastectomy to NAC, receipt of NAC was significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of ALND among patients with HER2+ (OR 0.19, p<.001) and triple-negative tumors (OR 0.25, p=0.007), but this effect was not statistically significant among ER/PR+ tumors (OR 0.62, p=0.096)(Table 4). Regardless of subtype or treatment type, those with lymphovascular invasion were also more likely to require ALND.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis assessing likelihood of axillary lymph node dissection by tumor subtype and treatment cohort: upfront mastectomy versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy

| Variable | Upfront mastectomy vs NAC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER/PR+, HER2− | HER2+ | Triple negative | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| NAC | 0.62 (0.35‒1.09) | 0.10 | 0.19 (0.08‒0.45) | < .001 | 0.25 (0.09‒0.69) | 0.007 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.27 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.23 | 0.98 (0.95‒1.01) | 0.22 |

| LVI | 4.75 (3.44‒6.57) | < .001 | 5.92 (2.94–11.9) | < .001 | 7.69 (3.38‒17.46) | < .001 |

| cT2 (vs cT1) | 2.09 (1.5‒2.91) | < .001 | 1.25 (0.6–2.6) | 0.56 | 0.87 (0.37‒2.03) | 0.75 |

NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; cT1, clinical T1; cT2, clinical T2

DISCUSSION

The surgical morbidity following SLNB alone is substantially less than that seen after an ALND, with significantly lower rates of lymphedema, sensory changes, wound infection, and arm dysfunction.11–13 The optimal treatment approach to minimize risk of ALND is related both to tumor subtype and type of surgery. Here we find that different strategies minimize ALND rates for patients with differing tumor biology. Among a population of women with cN0 “high-risk” early-stage breast cancer, defined as women undergoing BCS with a positive SLN or those recommended to receive NAC, those with ER/PR+, HER2− tumors undergoing BCS had ALND rates less than half of those seen among women treated with NAC (15% versus 34%, respectively). Conversely, when compared to women undergoing upfront mastectomy, those with a triple-negative or HER2+ tumor who received NAC had substantially reduced rates of ALND.

The reasons for these findings are two-fold. First, the indications for completion ALND differ between the treatment groups. Among women with cT1-2N0 breast cancer undergoing upfront BCS and radiation therapy, the results of the ACOSOG Z0011 study allow the safe avoidance of ALND among patients with 1–2 positive SLNs.1,2 Long-term results from this randomized controlled trial were reported with 9.25 years of follow-up and confirm no difference in locoregional recurrence among patients treated with either SLNB alone or completion ALND, with 10-year rates of regional recurrence <2% in both arms.14 Dengel reported that 84% of women meeting Z0011 criteria with a positive SLN were spared ALND by applying these criteria in clinical practice.15

In addition to applying the Z0011 results, a second strategy to decrease the need for ALND is the utilization of NAC. Studies examining SLNB following NAC in patients presenting with cN0 disease report similar identification rates and false-negative rates to those seen in the upfront surgery setting, with persistently lower rates of nodal positivity following NAC.5,16–20 The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-18 and NSABP B-27 trials as well as a single-institution report by Hunt and colleagues all reported significantly reduced rates of nodal positivity among women treated with NAC compared to those undergoing upfront surgery.3–5 Subsequently, the SENTInel NeoAdjuvant (SENTINA)21, ACOSOG Z107122, and the Sentinel Node Following NeoAdjuvant Chemotherapy (SN FNAC)23 trials evaluated the identification rate and false-negative rate of SLNB following NAC among clinically node-positive patients and reported acceptable (<10%) false-negative rates with the utilization of dual-tracer technique and removal of ≥3 SLNs. Following these publications, SLNB following NAC is increasingly used to minimize surgical morbidity among pathologically node-negative patients. While all patients included in this study were cN0 by physical exam, it is likely that a subset of patients were selected for NAC secondary to abnormal axillary imaging and/or a positive lymph node biopsy, as approximately one-third of patients in the NAC cohort had abnormal axillary lymph nodes identified on preoperative imaging. Interestingly, the utilization of NAC to maximize the likelihood of sparing an ALND is not a “one size fits all” approach. While rates of ALND have not been shown to differ by tumor subtype among women undergoing upfront BCS and managed according to Z001124, rates of nodal pCR following NAC differ substantially by subtype.

Multiple series have reported similar trends in rates of nodal pCR following NAC, with the lowest rates seen among hormone receptor+, HER2− tumors (0–29%), and the highest rates seen among triple-negative (47%–73%) and HER2+ tumors (49%–82%).8–10,25 Together, these data support the findings of our study. The most prevalent breast cancer subtype (ER/PR+, HER2−) is that least likely to achieve a nodal pCR following NAC and was found to have lower ALND rates following upfront BCS whereas tumor types associated with high nodal pCR rates were more likely to require ALND in the upfront surgery setting.

Although all patients included in this study were cN0 negative by physical examination, all upfront BCS patients were SLN positive, whereas the NAC and upfront mastectomy cohorts included both node-positive and node-negative patients. This comparison was intentional, to allow a more meaningful comparison of a higher-risk cohort of upfront surgery patients to those being selected for NAC, although in doing so, the rates of ALND in the upfront BCS group are higher than what would be found for all cT1-2N0 patients. As shown in Figure 1, if all cN0 ER/PR+, HER2− patients were considered (including the majority with pathologically node-negative disease), the ALND rate following BCS would be lower than the 15% rate reported for the node-positive patients included in this study, highlighting the substantial benefit in avoidance of ALND for upfront BCS in women with this tumor subtype. We have previously reported on a cohort of over 5000 patients with cT1-2N0 breast cancer undergoing SLNB with either BCS or mastectomy and found an overall nodal positivity rate of 25%, with only 6% having ≥3 positive SLNs.26 In the current cohort of nearly 4000 BCS patients over a 5-year time period, the overall rate of nodal positivity is 17%, with ≤3% requiring ALND across all subtypes. This finding is clinically significant because many surgeons advocate for routine axillary imaging to identify non-palpable axillary metastases in order to triage all node-positive patients to NAC. We have previously published on rates of ALND among women with cN0 disease with abnormal axillary imaging when treated according to Z0011 and found that ALND was only required in 30% of those with an abnormal axillary ultrasound.27 This is in contrast to data published by Barrio et al28 who reported on cN0 patients with abnormal axillary imaging who underwent NAC and found that 40% of those with an upfront abnormal axillary ultrasound required ALND post-NAC. In addition, 23% of women who were cN0 without abnormal axillary imaging prior to NAC were pathologically node positive following NAC. These data support our findings: among cN0 patients with hormone receptor positive, HER2 negative disease eligible for BCS, axillary ultrasound and triage to NAC for abnormal-appearing nodes or biopsy-proven nodal metastases would be expected to increase the need for ALND given the low rates of pCR for this tumor subtype.

For triple-negative tumors, a significant reduction in ALND following NAC compared to upfront mastectomy was seen, with a non-significant numerically lower ALND rate noted following NAC compared to upfront BCS. For a patient with a triple-negative tumor, chemotherapy remains the standard of care for T1b and larger lesions with identical regimens utilized regardless of whether treatment is given in the neoadjuvant or the adjuvant setting.6 Our data showing reduced ALND rates following NAC provide strong impetus for this treatment strategy for cN0 patients to decrease the likelihood of ALND in patients with triple-negative cancers.

Among HER2+ patients, the appropriate treatment path remains complex. Similar to the triple-negative subtype, patients with HER2+ tumors were found to have significantly lower ALND rates following NAC compared to upfront mastectomy, with a non-significant reduction in ALND following NAC compared to upfront BCS. NAC remains an appropriate strategy for women aiming to downsize a primary breast tumor and to minimize ALND risk; however, the caveat for HER2+ patients is that the final pathology and nodal status may impact the choice of optimal chemotherapy regimen, as single-agent chemotherapy with trastuzumab may be utilized for small (T1), node-negative tumors.29,30 For the HER2+ subtype, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to balance the potential for overtreatment from both a surgical and medical perspective when selecting the optimal treatment pathway. Further study is needed to assess the benefit of axillary imaging among women with HER2+ tumors to allow optimal triage to upfront surgery versus NAC.

This study is limited by the retrospective nature and non-randomized comparison of 3 different treatment cohorts with varying tumor features. In addition, the upfront mastectomy ALND rates may represent an overestimate, as newer data indicate that ALND is not necessary for micrometastasis in this setting.31,32 Similarly, for the upfront BCS cohort, ALND was considered warranted for >3 positive SLNs as well as gross/clinically significant extracapsular tumor extension. ACOSOG Z0011 did not define a volume of microscopic extracapsular extension that mandated ALND, and this is often left to surgeon judgment. One study reported that >2mm of extracapsular extension was associated with a heavy nodal disease burden33; however, need for ALND because of extracapsular extension remains an ongoing area of debate. Even with these limitations, we feel that the findings in this study will aid in counseling patients interested in optimizing avoidance of ALND.

Conclusion

Use of NAC is associated with lower ALND rates for cN0 patients with triple-negative and HER2+ subtypes compared to treatment with initial mastectomy, whereas women with ER/PR+, HER2− tumors have lower rates of ALND with upfront BCS compared to NAC. Type of planned breast surgery and subtype can be used to personalize treatment planning in order to minimize ALND risk in early-stage breast cancer patients.

Synopsis.

In this comparison of ALND rates in patients with cT1‒2N0 tumors undergoing upfront surgery to those treated with NAC, we conclude that breast cancer subtype and planned surgery can be used to personalize treatment planning in order to minimize ALND risk in early-stage breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was funded in part by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30 CA008748 to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Disclosures: This study was presented in part in poster format at the 2017 Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Meeting.

The authors have no conflict of interest disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuliano AE, McCall L, Beitsch P, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection with or without axillary dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252:426–32. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f08f32. discussion 432-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bear HD, Anderson S, Brown A, et al. The effect on tumor response of adding sequential preoperative docetaxel to preoperative doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide: preliminary results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol B-27. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4165–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher B, Brown A, Mamounas E, et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2483–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt KK, Yi M, Mittendorf EA, et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is accurate and reduces the need for axillary dissection in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:558–66. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b8fd5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2016 Version 2. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines_nojava.asp (Accessed February 28, 2017)

- 7.Zhang GC, Zhang YF, Xu FP, et al. Axillary lymph node status, adjusted for pathologic complete response in breast and axilla after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, predicts differential disease-free survival in breast cancer. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:e180–92. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boughey JC, McCall LM, Ballman KV, et al. Tumor biology correlates with rates of breast-conserving surgery and pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: findings from the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) Prospective Multicenter Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2014;260:608–14. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000924. discussion 614-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JY, Park HS, Kim S, et al. Prognostic Nomogram for Prediction of Axillary Pathologic Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Cytologically Proven Node-Positive Breast Cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1720. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamtani A, Barrio AV, King TA, et al. How Often Does Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Avoid Axillary Dissection in Patients With Histologically Confirmed Nodal Metastases? Results of a Prospective Study (Epub ahead of print) Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5246-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashikaga T, Krag DN, Land SR, et al. Morbidity results from the NSABP B-32 trial comparing sentinel lymph node dissection versus axillary dissection. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:111–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.21535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucci A, McCall LM, Beitsch PD, et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3657–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:599–609. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giuliano AE, Ballman K, McCall L, et al. Locoregional Recurrence After Sentinel Lymph Node Dissection With or Without Axillary Dissection in Patients With Sentinel Lymph Node Metastases: Long-term Follow-up From the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (Alliance) ACOSOG Z0011 Randomized Trial. Ann Surg. 2016;264:413–20. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dengel LT, Van Zee KJ, King TA, et al. Axillary dissection can be avoided in the majority of clinically node-negative patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:22–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xing Y, Foy M, Cox DD, et al. Meta-analysis of sentinel lymph node biopsy after preoperative chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:539–46. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Deurzen CH, Vriens BE, Tjan-Heijnen VC, et al. Accuracy of sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Classe JM, Bordes V, Campion L, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer: results of Ganglion Sentinelle et Chimiotherapie Neoadjuvante, a French prospective multicentric study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:726–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan VK, Goh BK, Fook-Chong S, et al. The feasibility and accuracy of sentinel lymph node biopsy in clinically node-negative patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer–a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:97–103. doi: 10.1002/jso.21911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly AM, Dwamena B, Cronin P, et al. Breast cancer sentinel node identification and classification after neoadjuvant chemotherapy-systematic review and meta analysis. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:551–63. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:609–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1455–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boileau JF, Poirier B, Basik M, et al. Sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer: the SN FNAC study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:258–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mamtani A, Patil S, Van Zee KJ, et al. Age and Receptor Status Do Not Indicate the Need for Axillary Dissection in Patients with Sentinel Lymph Node Metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3481–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diego EJ, McAuliffe PF, Soran A, et al. Axillary Staging After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer: A Pilot Study Combining Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy with Radioactive Seed Localization of Pre-treatment Positive Axillary Lymph Nodes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1549–53. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-5052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCartan D, Stempel M, Eaton A, et al. Impact of Body Mass Index on Clinical Axillary Nodal Assessment in Breast Cancer Patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3324–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5330-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pilewskie M, Jochelson M, Gooch JC, et al. Is Preoperative Axillary Imaging Beneficial in Identifying Clinically Node-Negative Patients Requiring Axillary Lymph Node Dissection? J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrio AV, Mamtani A, Eaton A, et al. Is Routine Axillary Imaging Necessary in Clinically Node-Negative Patients Undergoing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:645–651. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5765-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolaney SM, Barry WT, Dang CT, et al. Adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab for node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:134–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denduluri N, Somerfield MR, Eisen A, et al. Selection of Optimal Adjuvant Chemotherapy Regimens for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) -Negative and Adjuvant Targeted Therapy for HER2-Positive Breast Cancers: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline Adaptation of the Cancer Care Ontario Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2416–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mamtani A, Patil S, Stempel M, et al. Axillary Micrometastases Are Not an Indication for Post-Mastectomy Radiotherapy in Stage 1 and 2 Breast Cancer. Presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium; March 15-18, 2017; Seattle Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gooch J, King TA, Eaton A, et al. The extent of extracapsular extension may influence the need for axillary lymph node dissection in patients with T1-T2 breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2897–903. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3752-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]